- 1Hubei University, Wuhan, China

- 2Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Wuhan, China

- 3West Yunnan University of Applied Sciences, Dali, China

This paper evaluates the real effects of the environmental policy at the firm level. Using the promulgation of the “Green Credit Guidelines" and national poverty alleviation strategy as a quasi-natural experiment, we find that:1) the Guidelines significantly inhibit the scale and maturity of debt financing for polluting companies; 2) the participation of enterprises in poverty alleviation efforts can effectively offset the restraining influence of the Guidelines. Our results are robust for parallel trend assumption and propensity score matching estimation. Further, we find that state-owned enterprises have decreased more significantly. These results indicate that the national poverty alleviation strategy could play a role in debt financing for polluting companies. Thus providing timely implications for regulators concerned with environmental protection.

1 Introduction

Since the reform and opening up, China’s economic development has made remarkable achievements, but the original economic development model has also produced serious environmental pollution, which is not sustainable. These influences not only restrict the development of China’s economy, but also seriously damage the health of Chinese residents. On 24 February 2012, the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) issued the Green Credit Guidelines1, requiring Chinese financial institutions to support the development of green and low-carbon economy, improve the level of green credit financial services, and strengthen the ability to support green credit debt.

Since its introduction, the green credit policy has achieved good results, restraining the bank credit of high energy consumption and high pollution industries2, optimizing the industrial structure, and effectively preventing financial risks. But with the proposed political task of targeted poverty alleviation, are enterprises involved in poverty alleviation exempted? At present, there is little literature on this aspect.

On the one hand, working to alleviate poverty has long been a high priority for the Chinese government and an important part of its vision for a well-functioning society. Targeted poverty reduction is a Chinese political term, first proposed by General Secretary Xi Jinping in 2013, that refers to a new form of corporate social responsibility. Corporations send signals to the market by disclosing relevant social responsibility information such as targeted poverty alleviation efforts, which can not only reduce the degree of information asymmetry and highlight their positive financial status and development prospects, but also establish a responsible corporate image and enhance their social reputation. Participating in such efforts gains the attention of both the market and potential investors, and thus can make a positive impact on improving the financing environment of enterprises.

On the other hand, enterprises the participating to alleviate poverty reduce the cash flow of enterprises to a certain extent. When enterprises need cash, they need to raise more funds by issuing stocks or bonds, thus deepening the financing constraints of enterprises. Does enterprise participating in poverty alleviation alleviate or strengthen financing constraints?

Our results suggest three main findings. First, the Guidelines significantly inhibit the scale and maturity of debt financing for polluting companies. The scale of corporate financing loans decreased by 2.6–3%, and the scale of long-term loans decreased by about 4.8%. Second, Corporate participation in poverty alleviation can offset the inhibitory effect of the Green Credit Guidelines. Enterprises that do not participate in poverty alleviation have their financing scale decreased by about 3% due to the “Green Credit Guidelines” policy. Third, we find that state-owned enterprises have decreased more significantly in Corporate participation in poverty alleviation can offset the inhibitory effect of the Green Credit Guidelines. Enterprises that do not participate in poverty alleviation have their financing scale decreased by about 3% due to the “Green Credit Guidelines” policy. These results indicate that the national poverty alleviation strategy could play a role in debt financing for polluting companies.

This paper contributes to the literature on participation in poverty alleviation work in China. Our analysis is one of the few to explore the micro-mechanisms by which participation in poverty alleviation affects the actual economic activities of businesses. It provides a new perspective for research into the factors that affect the financing of Chinese enterprises.

Second, we contribute to the literature on the determinants of corporate financing. A better understanding of how environmental policy determines corporate financing is particularly important given the significant role environmental issues play in China and worldwide. We show that environmental policy significantly affects corporate financing.

In addition, this paper provides timely inspiration for policy-makers concerned about the impact of environmental policies on corporate behavior and calls for enterprises to actively participate in poverty alleviation work.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the institutional background, section 3 explains the data and variables, and section 4 analyzes the empirical results. Sections 5 offers further analyses, section 6 presents the test results for robustness and section 7 concludes.

2 Institutional background and research hypothesis

2.1 The impact of green credit policies on corporate financing

The China Banking Regulatory Commission issued the Green Credit Guidelines in 2012 for a variety of reasons: to implement the combination of regulatory and industrial policies of the “12th Five-Year Plan”, to promote the development of green credit business within banking financial institutions, to adjust credit structures, to prevent environmental pollution risks caused by enterprises, and to avert potential social risks. According to these guidelines, financial institutions should promote green credit through three means. First, they should support a green and low-carbon circular economy and strictly control the scale of loans to “two high and one overcapacity” industries.3 Second, they should optimize credit structures by restricting overall loans to prevent lending capital to companies that are not good environmental stewards. Third, they should improve the image of the finance industry by adjusting loan policies to encourage environmental responsibility (Fang and Li, 2019).

Developed countries in the West have taken the lead in applying green credit policies to the process of economic development. The evaluation criteria for credit review included whether the company pollutes and harms the environment (Pérez-Orive, 2016; Ye and Fang, 2021). Wu et al. (2017) point out that in green credit the quality of environmental information disclosure by firms has become the deciding factor for financial institutions. At the same time, more relaxed and convenient credit policies are given to environmentally-friendly enterprises so as to limit the development of businesses that pollute and realize the purpose of policies guiding the allocation of credit toward enterprises that are committed to preserving the environment (Xia and Liming, 2019).

Developing green credit policies is an innovative financial method that combines credit policies with environmental protection objectives (Labatt, 2002) that not only help Chinese banks and other financial institutions optimize social resources but also encourage companies to disclose their environmental responsibilities. The policy can assist companies in obtaining greater credit support through reducing environmentally damaging behavior. In China, the impact has been such that commercial banks and other financial institutions provide more loans for environmentally-friendly or energy-saving firms (Aizawa and Yang, 2010; Zhang et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2017). Therefore, the green credit policy has made important contributions to the “greening” of the Chinese economy and society. By the end of 2020, the green credit balance of 21 major Chinese banks had exceeded 11 trillion yuan, with the loan balance and growth scale of green transportation, renewable energy, energy conservation and environmental protection projects leading the way.

Green credit has spurred considerable academic interest and study. Some research has looked at issues with the development and implementation of such policies. In the early stages of the green credit revolution in China, commercial banks often had difficulty assessing risks when implementing green credit policies because finance workers lacked professional knowledge of what the policies were or how they worked (Ye, 2008; Zhang et al., 2011). Many green credit policies were not implemented efficiently. For example, to circumvent the constraints and restrictions of the green credit policy, some polluting companies turned to private lending and other methods of fund raising, running counter to the desired result.

With the gradual spread of green credit policies in developed countries, researchers made comparisons across international boundaries, summarizing the experiences of a range of countries (Jiang and Xu, 2016; Zhou et al., 2017). They highlight that, while following guidance set by other countries may be a rational way to implement China’s green credit policies, the government must first establish sound regulatory mechanisms to optimize the industrial economic structures. On this note, Yu and Wang (2021) talk of how China’s strengthening environmental regulations is way for the governments to optimize its industrial economic structures as the economy moves from one of rapid growth into the stage of high-quality development.

In a different stream of researchers, other scholars have tended toward investigating the effects and outcomes of green credit initiatives as opposed to the early stages of development and implementation. For example, Cai (2013) used data from listed companies in polluting industries, such as papermaking, mining and electricity, to test the effectiveness of green credit policies. They find that such policies help banks to assess credit targets, thereby supporting the notion that green credit policies can promote the development of a green Chinese economy (Hee and Lyon, 2011). Su and Lian (2018) took the implementation of the 2012 Green Credit Guidelines as an exogenous event, constructed a quasi-natural experiment, and used the DID method to examine the actual changes in the investment and financing behavior of polluting companies before and after the implementation of the policy. The research conclusions show that after implementing the guidelines, impetus to invest in large heavy-polluting SOEs was significantly reduced, and the financing costs for those companies had significantly increased. All the above findings indicate that green credit significantly inhibits investment into polluting companies.

The 19th National Congress proposed that green development is the logical outcome of sustainable development, and green finance offers an important avenue in China’s pursuit of building an ecological civilization. So how does green credit, as the main financing channel for green corporate projects, affect the growth of the green economy? Xie and Liu (2019) used a directional distance function and panel data for 30 provinces in China from 2006 to 2017 to calculate the green economic growth index of each region. The research results show that green credit policies significantly promote Chinese economic growth and that increasing the degree of marketization and fiscal decentralization would be conducive to promoting further green economic growth. Li et al. (2021) conducted an empirical analysis on the impact of green finance on the industrial structure based on the urban panel data from 2010 to 2019 using the grey correlation analysis method, and concluded that the development of green finance can optimize the industrial structure. Ouyang (2021) measured the development of green finance at the provincial level and calculated the green economic growth index. The research results show that the green credit policy has a significant role in promoting the growth of the green economy, and the improvement of the degree of marketization and fiscal decentralization is conducive to promoting the growth of the green economy. In addition, Zhang and Ge (2021) used the double difference method to explore the role of green finance policy on internal resource allocation and optimization of enterprises in heavily polluting industries, using the green credit guidelines issued in 2012 as an exogenous shock. Research shows that green financial policies can significantly improve the efficiency of resource allocation within heavily polluting industries and promote green economic development.

Most of the mentioned studies focus on the macro- and meso-levels of the environmental effects of green credit policies. However, the specific implementation targets of macro policies are micro-level concerns, which are under-explored in the literature. Hence, with this research, we have studied the impact of green credit policies on enterprises at the micro-level, and especially how the scale of corporate debt financing and credit terms affects the policy outcomes.

According to the “Green Credit Guidelines” policy, banking financial institutions will promote green credit from three aspects: First, to increase support for a green, low-carbon and circular economy, and to control the issuance of credit to outdated production capacity. Second, to pay attention to preventing environmental and social risks. Third, banks focus on own environment and social performance. It can be seen from this that the Green Credit Guidelines aim to limit the scale and duration of loans to polluting and backward productivity companies. At the same time, the policy intends to increase support for a green low-carbon circular economy by redistributing credit resources while strictly controlling the “two highs and one overcapacity”4 credit supply.

Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses

H1. The Green Credit Guidelines have significantly inhibited the debt financing for polluting enterprises.

2.2 The impact of enterprise participation in poverty alleviation

As an emerging market economy, the government maintains tight monopolistic controls over market resources, which means companies cannot fully rely on the market to acquire all the resources they may need to operate. In other words, enterprises heavily depend on the government for resources, such as finance credit resources. Social exchange theory holds that human behavior is governed by exchange activities that bring rewards.

Policy resources can take many forms, from fiscal and tax subsidies to exemptions, from rights issues by government departments to enter high-barrier regulated industries to better financing and credit environments. Under the leadership of the government, companies participating in targeted poverty alleviation not only help the government fulfill their social goals but also establish a connection between the company and the government. This leads many companies to use the relationships they hold with government to improve their business development environment and reduce the barriers they face to growth.

In reality, however, information asymmetry means stakeholders may only be able distinguish between different enterprises through the signals associated with various social behaviors. Some studies have discussed the positive impact of environmental information disclosure on firm credit financing (Li et al., 2019). Participating in poverty alleviation initiatives sends a different signal about what aspects of corporate social responsibility are important to a firm. Therefore, its influence on financing constraints may also be difference, as discussed next.

First, one of the prerequisites for a company to engage in alleviating poverty is that it is meeting its own daily operating needs and ensuring sufficient cash flow while disclosing information about the firm’s sound financial status to the outside world. Beyond the hypocrisy of a poor, badly run company attempting to help others alleviate these same problems, sound fiscal management and transparent reporting allows external actors to assess the enterprise’s operations and develop a more accurate understanding of its workings. Investors’ trust on capital funding increases, therefore, relieving financing constraints.

Second, in the context of the Chinese national economy, the government and SOEs occupy a dominant position. Enterprises exchange resources with the government by fulfilling their social responsibilities and gain financial support in return (Wang et al., 2020). The 2016 “Ten thousand enterprises help ten thousand villages” policy document5 states that relevant departments should proactively provide services, information, financing and other support to enterprises participating in poverty alleviation. Companies can also issue special corporate bonds for poverty alleviation through the exchange bond market (referred to as “poverty alleviation bonds”). These measures have given poverty-alleviating enterprises certain unique financing options, which means enterprises can get funding support from banks and the government for their poverty alleviation efforts while simultaneously addressing any financing constraints they might be experiencing.

Third, as an informal system, Confucian culture has subtly played a guiding role in Chinese thought and behavior, and exerted an important influence on all aspects of Chinese society, economy and politics (Fu and Tsui, 2003; Zhang, 2013). In terms of its specific impact on enterprises, Confucian culture helps to restrain the encroachment of small and medium shareholders’ interests, reduce company agency costs, and improve agency efficiency and corporate performance (Du, 2015; Gu, 2015).

From a subjective point of view, Confucian culture enhances the altruistic motivation of enterprises to fulfill their social responsibilities. Entrepreneurs with social preferences are more concerned about the public’s evaluation of their individuals, so the enterprises they operate are often more inclined to actively undertake social responsibilities (Li & Song, 2015). Confucian culture helps to improve the altruistic preference of entrepreneurs, thereby enhancing the intrinsic motivation of enterprises to fulfill their social responsibilities.

From an objective point of view, Confucian culture exerts public opinion pressure on enterprises to fulfill their social responsibilities. Traditional culture will form a strong external public opinion pressure on enterprises (Bi et al., 2015). With the development of the times, the Chinese public’s awareness of social responsibility has been continuously enhanced, and the calls for enterprises to fulfill their social responsibility are getting louder and louder.

Thousands of years of Confucian culture in China have had a profound impact on corporate social responsibility. Social responsibility theory believes that the purpose of enterprise operation is not limited to the pursuit of profit. While taking responsibility for shareholders and employees, it is also responsible for consumers, communities and the environment. That is to say, it emphasizes attention to human values and contributes to the environment and society. Enterprises that actively participate in poverty alleviation are more likely to establish a good reputation and reputation, and gain the recognition and support of the public. Therefore, creditors will recognize companies participating in poverty alleviation projects and are more willing to lend to these companies.

From the basis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2. The participation of enterprises in poverty alleviation efforts can effectively offset the restraining influence of the “Green Credit Guidelines and Policies” on polluting enterprise financing constraints.

3 Data

3.1 Data and sample selection

To investigate the effect of the Green Credit Guidelines on corporate financing and the impact of corporate poverty alleviation behavior on their financing, we constructed a sample based on Chinese companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2009 to 2019. The period begins in 2009 to allow 3 years prior to 2012 for the DID estimation (the first year the Green Credit Guidelines were implemented). The targeted poverty alleviation and financial data of enterprises was taken from the CSMAR database. The values is set to 0 if the companies have not participated in or disclosed poverty alleviation. The industries classified as polluting were taken from the standard list in the Green Credit Guidelines.

Lastly, the samples were screened for exclusion according to several criteria. Special treatment (ST) companies were eliminated. Companies in the finance industry were also excluded because their listing and reporting requirements are significantly different from other companies. Further, the main continuous variables for all remaining companies are winsorized at the 1% level to eliminate the effects of extreme values. The final sample consisted of 14,973 firm-year observations.

3.2 Methodology and variables

Empirical studies on the effects of policies commonly rely on a DID model—hence, our choice to use a DID analysis to explore the effects of the Green Credit Guidelines on corporate financing. The basic regression model was estimated as:

The explained variable L represents the scale and maturity of debt financing. The sum of short-term and long-term loans accounts for the proportion of total liabilities is used as a robustness test and is represented by L1. The ratio of the sum of short-term and long-term loans to the company’s total assets was used as the explanatory variable to measure the scale of corporate debt financing, denoted as L2. In addition, we also used the ratio of the sum of short-term loans to the company’s total liabilities as an explanatory variable to measure the scale of corporate short-term debt financing, denoted as Short1. Likewise, Long1 represents the ratio of the sum of long-term loans to the company’s total liabilities.

The explanatory variable in the model is an interactive item

To ensure that the results were not driven by the heterogeneity of the firm, we added the following control variables to cover firm characteristics, denoted as

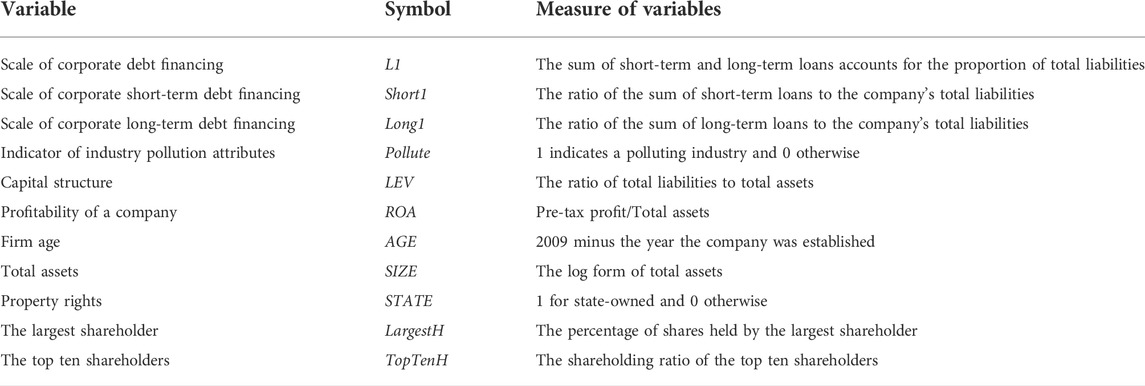

The definitions of related variables are presented in Table 1.

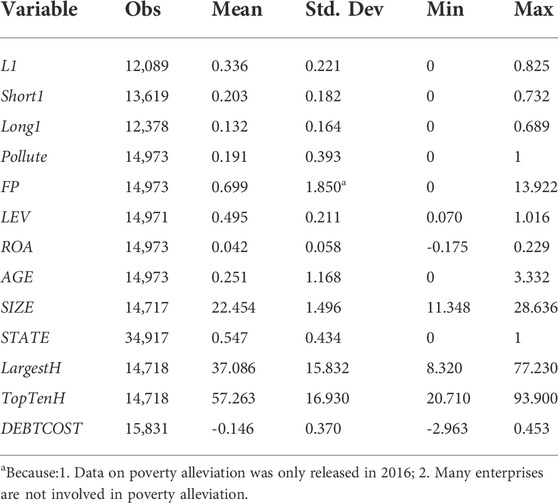

3.3 Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics of the variables are shown in Table 2. As shown, the average value of corporate debt financing (L1) was 0.336 with maximum values of 0.825. This is a clear demonstration of the significant differences in the extent of debt financing for different enterprises, providing motivation for the basis of this study. Further, polluting enterprises accounted for 19.1 percent. The maximum return on total assets (ROA) was 0.229 with a minimum of only -0.175, profitability varies considerably across the sample. Variables such as the asset-liability ratio (LEV) and enterprise size (SIZE) show that the financial position and size of the different enterprises also varies.

4 Empirical results and analysis

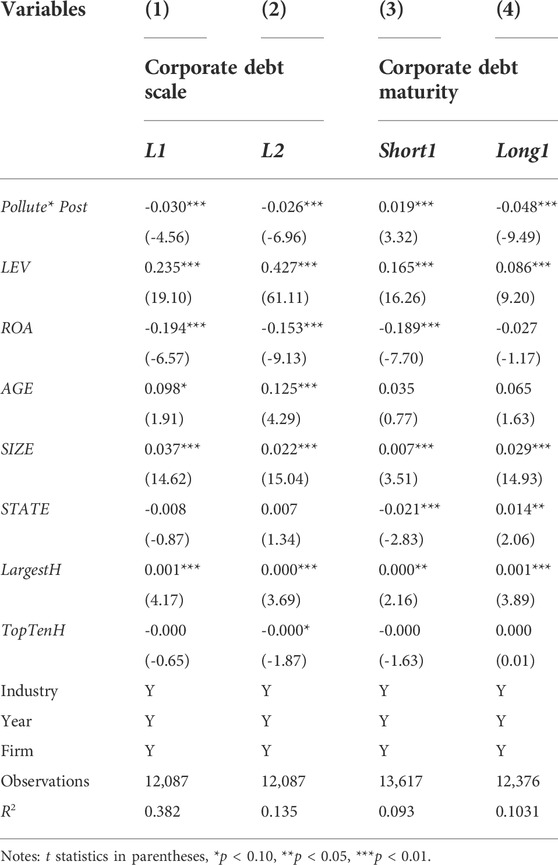

4.1 Empirical analysis of green credit policy on the scale of corporate debt financing

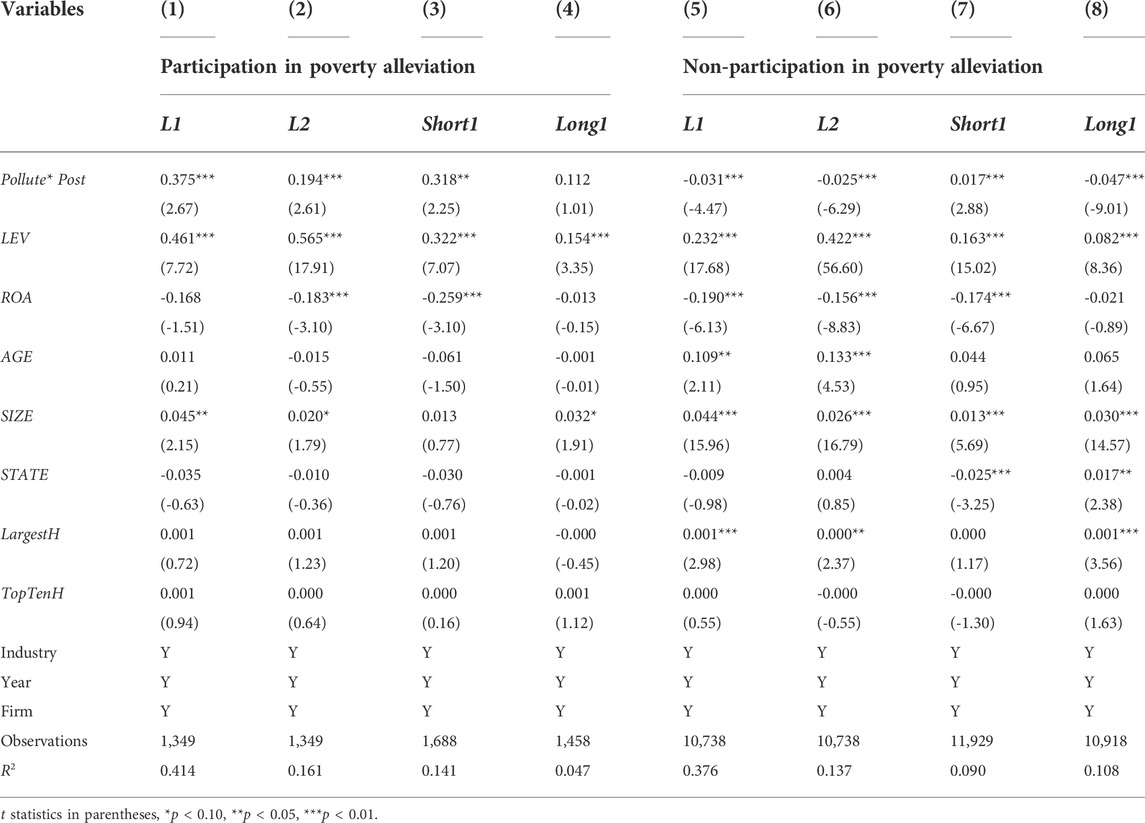

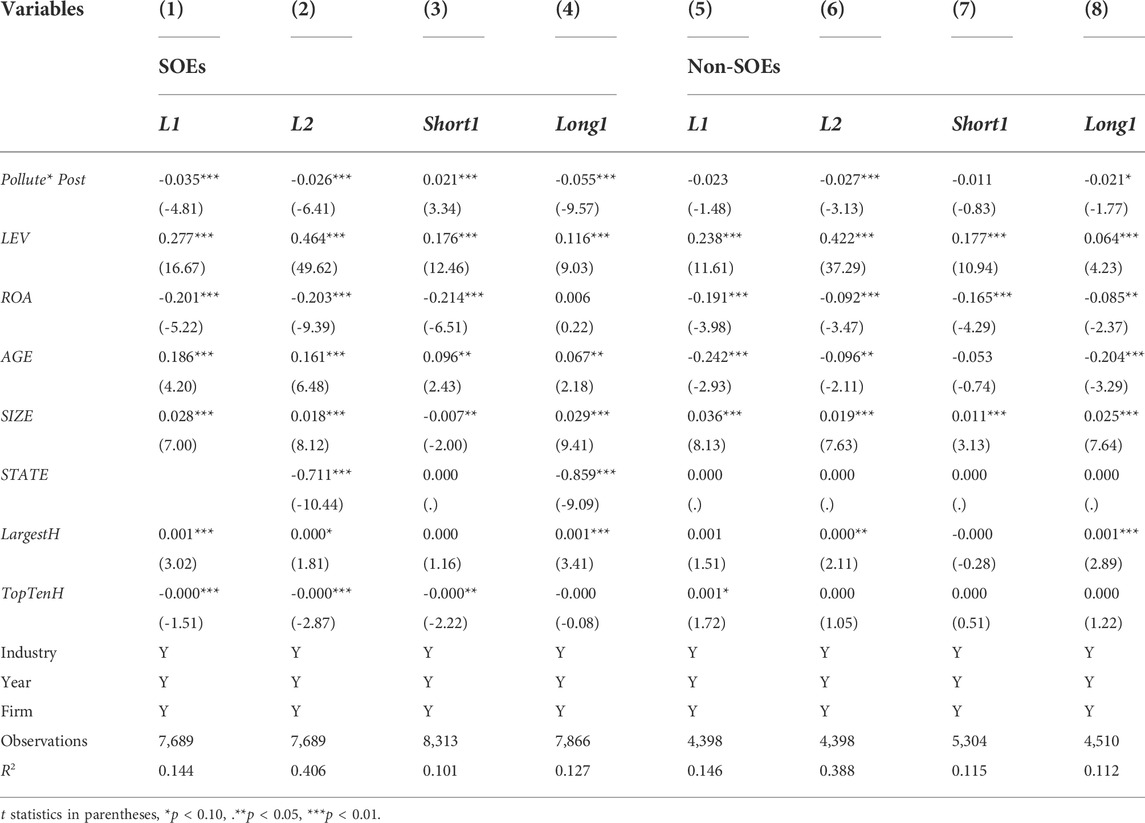

The impact of green credit policies on the scale of corporate financing debt is shown in Table 3. The explained variable L1 represents the debt financing scale of the companies, and L2 is used for robustness test. It can be seen from columns 1 and 2 of Table 3 that, regardless of how the extent of corporate debt was measured, the coefficient of the interaction term Pollute*Post was always negative and significant at the 1% confidence level. This indicates that the effect of the Green Credit Guidelines has indeed achieved the goal of curbing the scale of debt financing of polluting industries. Additionally, the estimated effect of the green credit policy on the extent of debt for the polluting companies was about 3%. This result is consistent with hypothesis H1 and the results of previous studies.

TABLE 3. Empirical results of green credit policy on the scale and maturity of Corporate Debt Financing.

From the perspective of control variables, the coefficients such as enterprise size (SIZE) and return on assets (ROA) are also consistent with the results of previous studies. The return on assets (ROA) of an enterprise is negatively correlated with its debt financing maturity. That is because profitable firms use more internal capital and less external debt.

From the results in columns 3 and 4 of Table 3, we can see the impact of the Green Credit Guidelines on the firms’ short-term and long-term loans. The Pollute*Post coefficient in column 3 is positively siginificant, suggesting that the Green Credit Guidelines restrict long-term loans while focus companies to use short-term loans. It is also a reflection of Green Credit Guideline loan constraint effect. This is very likely because the Guidelines emphasize that financial institutions should limit the environmental and social risks of granting credit to polluting companies by shortening the debt maturity. This result is consistent with hypothesis H1.

With respect to the control variables, the findings are consistent with previous results.

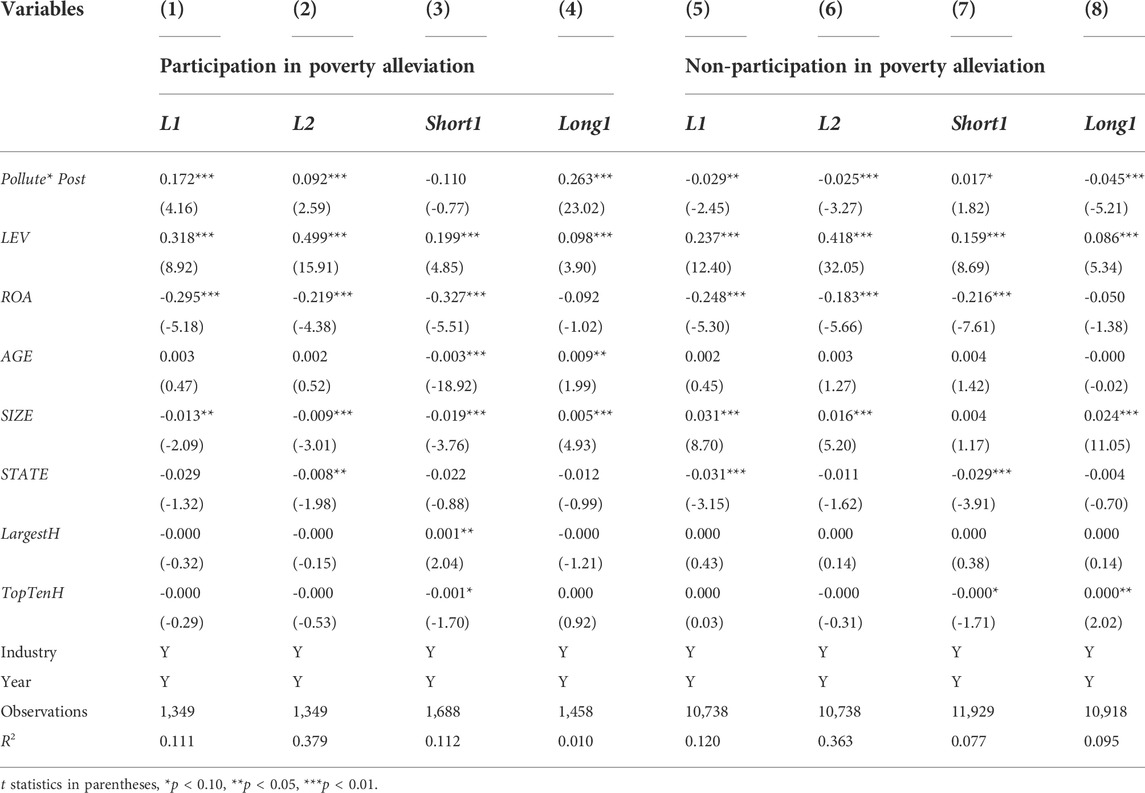

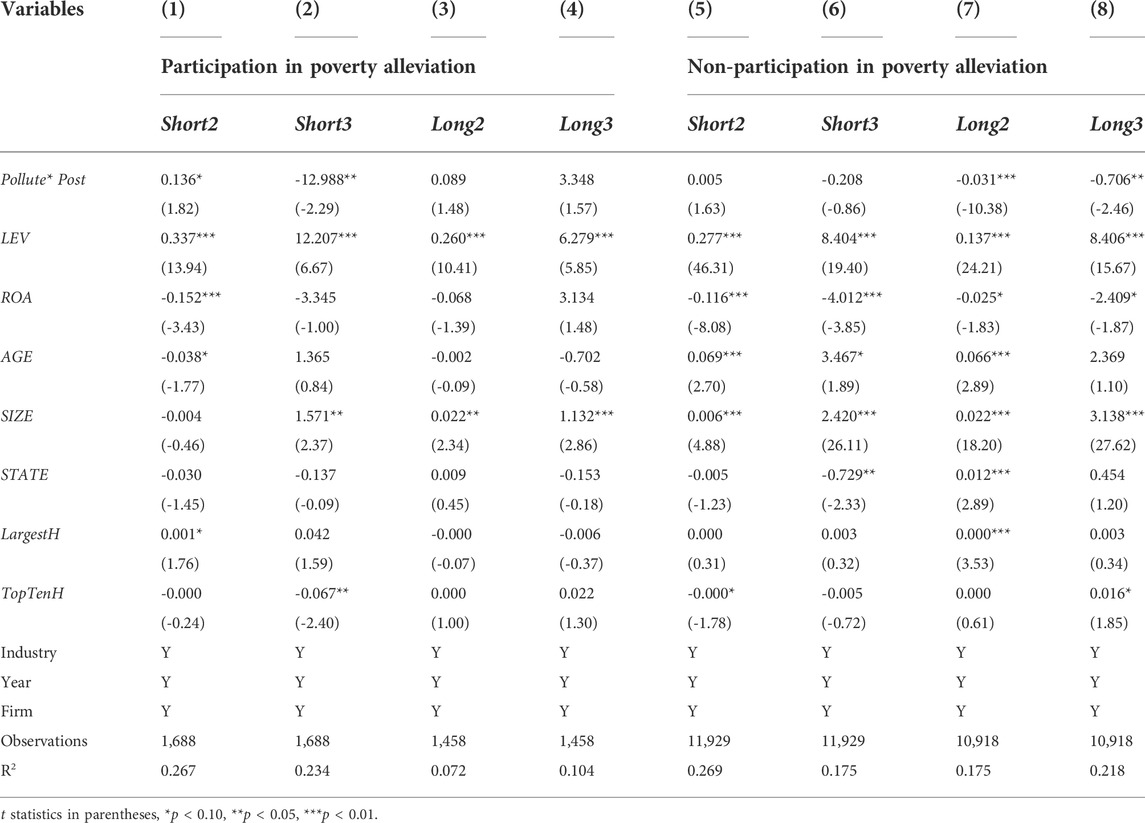

4.2 Empirical analysis of corporate participation in poverty alleviation and corporate debt financing

For this portion of the analysis, we divided the enterprises into two groups: those who had participate in poverty alleviation projects and those who had not. The regression results are shown in Table 4. Column 1 lists the scale of debt held by the participating enterprises. From the Pollute*Post coefficients, we can see that the scale of debt for these companies has increased by about 20–30% (significant at 1%). This shows that corporate participation in poverty alleviation can counteract the path to debt financing, all but exempting the inhibitory effects brought about by the Green Credit Guidelines. In column 5, Pollute*Post is about -3% and significant at 1%. Coupled with a significant downward trend over the period, this result shows that the policies are working: enterprises who do not participate in poverty alleviation are not receiving as much credit.

We further explored whether corporate participation in poverty alleviation affected credit maturity. Columns 3 and 4 show the results for the enterprises involved in poverty alleviation. The Pollute*Post coefficients for both increased, which demonstrates that companies participating enterprises can extend the terms of their debt repayment to relatively long periods. Columns 7 and 8 show the results for the non-participating firms. The Pollute*Post coefficients show that long-term loans decreased by about 4.7% while short-term loans increased. Thus, for those not interested in supporting the government’s agenda, the loan terms have been shortened.

In terms of the control variables, consistent with the previous results, the company’s asset-liability ratio (LEV) is positively correlated with the company’s debt financing maturity and significant at the 1% level. Return on assets (ROA) is negatively correlated to the debt financing period.

Overall, the results show that, against a background of increasingly serious environmental pollution, the state has introduced green credit and the scale and maturity of financing credit for polluting companies has been significantly regulated. However, the participation of enterprises in poverty alleviation efforts can effectively offset the restraining influence of the “Green Credit Guidelines and Policies” on enterprise financing constraints. The above results are confirmed H2.

5 Further analysis

5.1 The analysis of the influence of green credit policy on the financing cost of enterprises

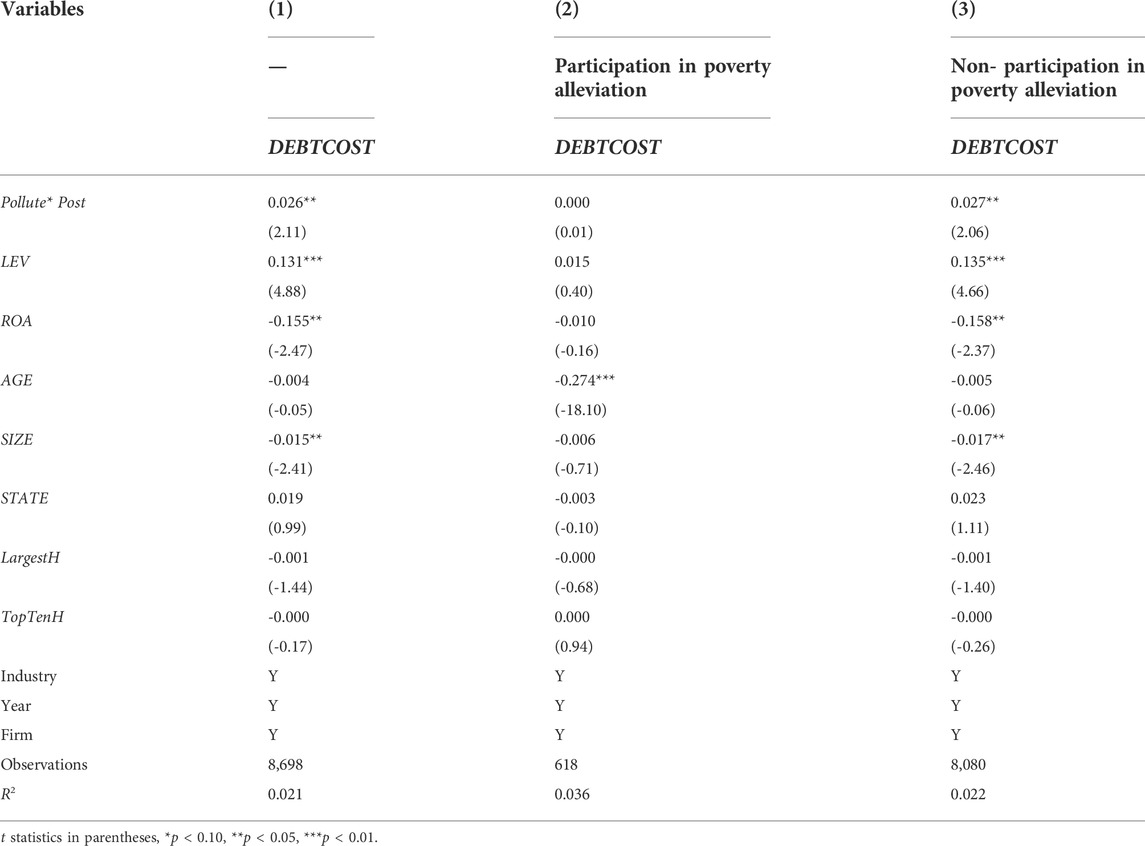

The main purpose of the green credit policy is to restrict financing to enterprises in polluting industries. However, beyond exploring the effectiveness of the green credit policy at achieving its goal, we are also interested in the impact the green credit policy has on the cost of corporate financing. To explore this notion further, we conducted an empirical study following the methods of Zheng and Yan, 2016.

DEBTCOST was defined as Financial expenses/(short-term borrowings + long-term borrowings + long-term borrowings due within 1 year + bonds payable).

To test this premise, we substituted DEBTCOST into the regression model and added control variables for year, industry, and the firms’ fixed effects. As shown in Table 5, the coefficients in the first column are positive and significant at the 5% level. In addition, from the results in columns 2 and 3, it can be seen that the financing cost of enterprises participating in poverty alleviation has not changed significantly. The financing cost of enterprises not participating in poverty alleviation has increased. Because the cost of credit financing is a part of the operating cost of a business. If the cost of financing increases, it will reduce the profit of the company. Therefore, the “Green Credit Guidelines” restrain the scale and duration of financing of enterprises by increasing the financing cost of enterprises.

5.2 The heterogeneity of ownership

The literature suggests that SOEs and enterprises will be protected by any political ties they have (Li et al., 2015). Driven by the Official Promotion Championship (Zhou, 2007), the impact of the quality of local environmental governance on local governments, and even officials, cannot be ignored. SOEs have always assumed important responsibilities in terms of employment resolution, charitable donations, and so on, because, in China, companies with political ties enjoy preferential treatment in the form of tax incentives and government subsidies (Zou, 2018). Therefore, it is interesting to examine the different effects of the Green Credit Guidelines on debt financing for SOEs versus non-SOEs and whether the green credit policy effects change simply because the target curries favor with the regulators.

For this analysis, we therefore considered the effect of each firm’s ownership structure on its debt financing. The results in Columns 1 of Table 6 is -0.035 and significant at 1% while -0.023 but not and significant in Columns 5 of Table 6. It show that the financing scale of state-owned enterprises has decreased more significantly, which may be because most of the enterprises restricted by the green credit guidelines are in the coal and steel industries, and most of these enterprises are state-owned enterprises. Long-term lending has been curbed for both SOEs and non-SOEs. By contrast, Green Credit Guidelines has a higher restriction effect on SOEs bank loans than non-SOEs, but non-SOEs is also affected to a certain extent, indicating that Green Credit Guidelines plays a good role in loan resource allocation.

6 Robustness tests

6.1 Parallel trend assumption

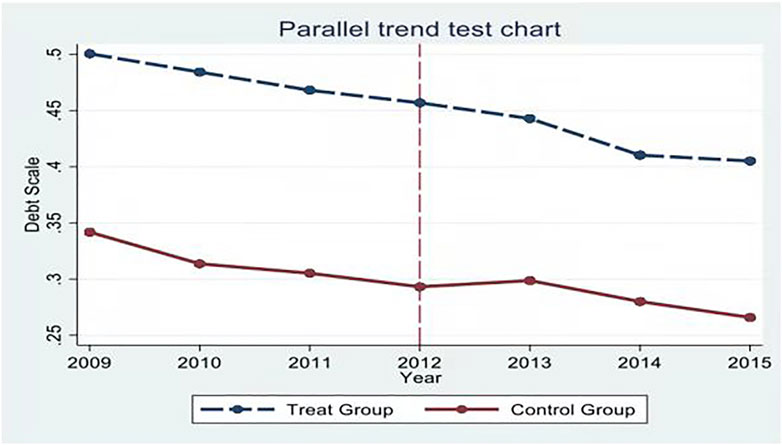

The validity of the DID approach depends on satisfying the key identifying assumption behind this strategy, the parallel trend assumption, which requires a similar trend in corporate debt scale during the pre-shock period for both the treatment and control groups. Therefore, the first robustness test is to examine the parallel trend assumption within our DID test.

Figure 1 provides the parallel trend test chart, which shows that, before the green credit policy was implemented, there was no significant difference between the extent of financing between the treatment and control groups. However, since the green credit policy took effect in 2012, there have been significant differences in the extent of financing for the treatment and control groups. The consistency of this result with the previous analysis validates use the DID model to test the impact of green credit policies on corporate financing.

6.2 Bootstrapping the samples

Bootstrapping is a method, common to computer simulations, that is often used to solve statistical problems with large samples. The method prescribes that the given test be repeated multiple times with a new set of samples selected at random but with an equal probability of each sample in the original data set being selected. In this way, the average value of the statistics of 500 samples can be obtained by repeating the sampling 500 times. The mean calculated by this combination is more stable and more convincing than any result collected by analyzing all samples at once.

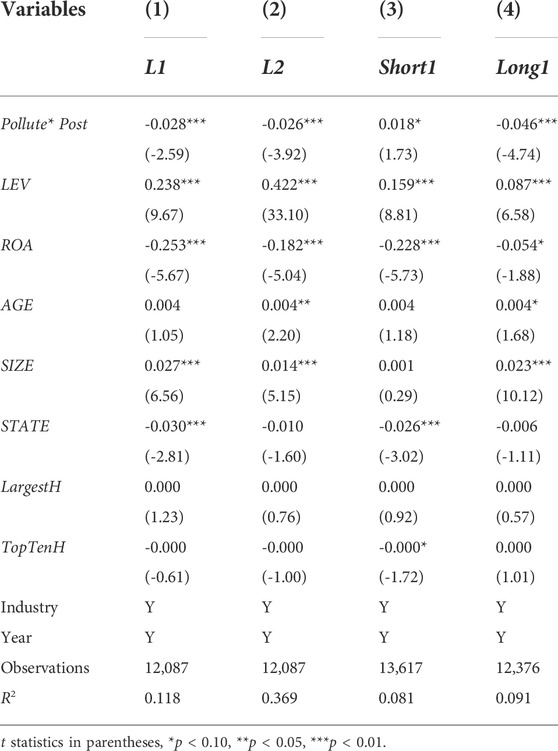

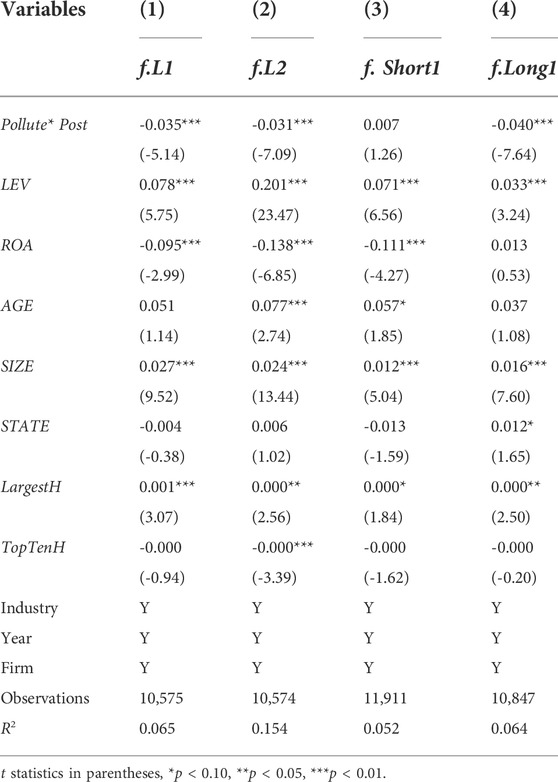

6.2.1 Bootstrap of green credit policy on corporate debt financing

The test results for robustness using the bootstrapping method are shown in Table 7. Regardless of how the independent variable corporate debt financing scale was measured, the coefficients for Pollute* Post in Columns 1 and 2 were always negative and significant. The coefficients in Column 3 indicate that the Guidelines have not had a significant impact on the company’s short-term loans. However, Long1 in Column 4 shows that the green credit policy has significantly reduced the scale of long-term loans. This finding suggests that it is very unlikely that DID estimated results in the main regression are purely driven by chance.

6.2.2 Bootstrap of corporate participation in poverty alleviation on corporate debt financing

To further test robustness, we again divided the sample into participating and non-participating companies. The regression results in Columns 1–2 of Table 8 show that the amount of debt financing have increased but only for companies participating in poverty alleviation projects. Columns 5 and 6 show that, for non-participation firms, the overall amount of debt has dropped by about 2.5–2.9%. These results confirm that the results of the previous empirical analysis.

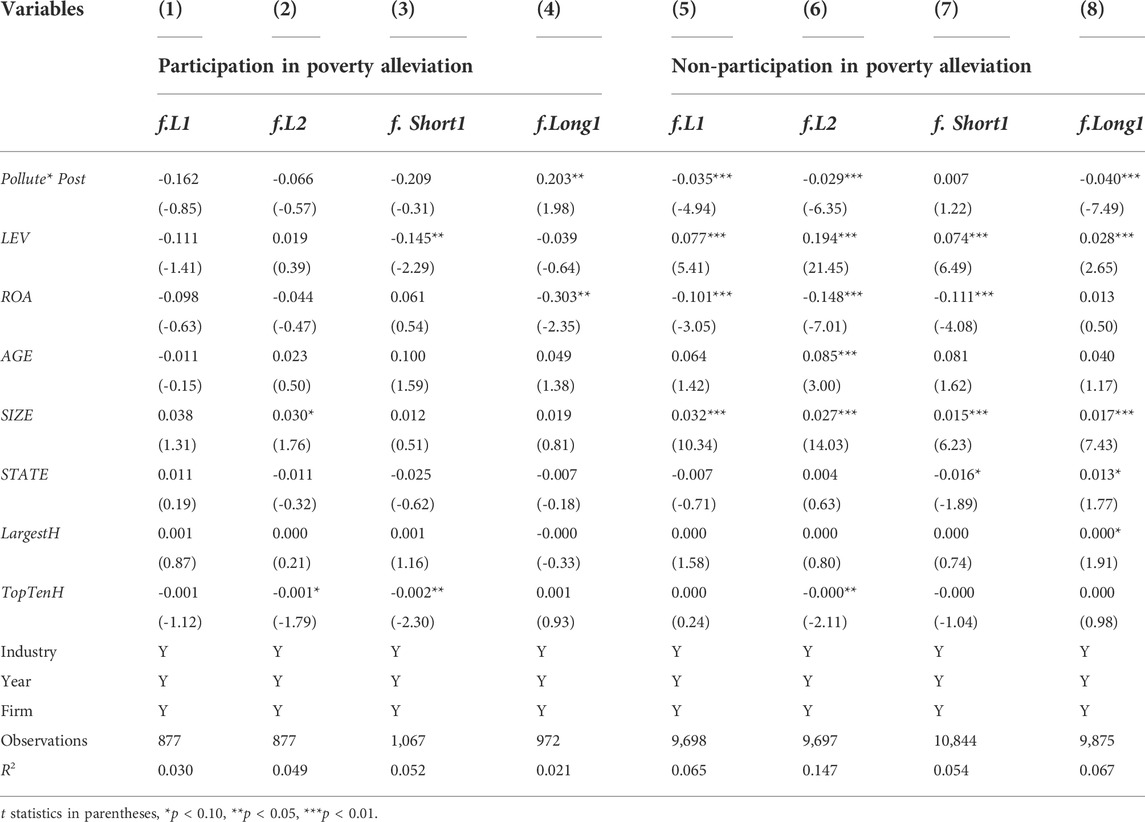

6.3 Replacement metrics

To validate the robustness of the empirical tests, we changed the method of measuring the dependent variable L1 from the ratio of the sum of short-term and long-term loans to the company’s total liabilities to instead of L2, calculated as the sum of short-term and long-term loans accounts for the proportion of total assets. Similarly, we originally calculated Short1 as the ratio of the sum of short-term loans to the company’s total liabilities. This method was replaced with two different formulae: Short2 calculated as the ratio of the sum of short-term loans to the company’s total assets, and Short3 calculated as the log form of the total short-term debt plus 1. Long1 from the ratio of the sum of long-term loans to the company’s total liabilities was replaced with Long2 as the ratio of the sum of long-term loans to the company’s total assets and Long3 as the log form of the total long-term debt plus 1. The regression results with these formulations are shown in Tables 9, 10. All results support the previous findings.

6.4 Robustness test of lag effect

To test for a lag effect, we replaced the dependent variable with the data sampled from the period t+1. All results support the previous findings. The regression results with these formulations are shown in Tables 11, 12. All results support the previous findings.

6.5 A robustness test to exclude the “municipalities effect”

The same policy often produces very different effects in different regions because certain municipalities are directly under the control of the Central Government. Therefore, we ran the tests without these regions and compared the results. The regions excluded were Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai and Chongqing.

Our findings suggest that the results of the main regression are robust.6

7 Conclusion

In this paper, we used the DID method to conduct an empirical analysis of the impact of China’s Green Credit Guidelines on the debt financing of listed companies given corporate participation in poverty alleviation. From the findings we draw the following conclusions.

First, the Green Credit Guidelines significantly inhibit the scale and maturity of debt financing for polluting companies. The policy controls the size and duration of loans to polluting companies by increasing their financing costs. However, it may be that it gives companies some latitude to allocate resources to green innovation or move from a rapid growth mode to an intensive development posture.

Second, the enterprises actively participating in poverty alleviation are tending to circumvent the inhibitory effect of the Green Credit Guidelines on financing credit. The results provide evidence to suggest that these enterprises are using the sanctions in the guidelines to obtain financial support from banks and the government to overcome financing constraints. This insight enriches the research on poverty alleviation in China and provides a new perspective for research into the factors that influence financing for Chinese enterprises.

Third, many researchers have pointed out that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) with political background enjoy preferential treatment in finance and financial subsidies. The question, then, is whether SOEs are receiving special treatment in the context of the green credit policy. In response to these doubts, we conducted a deeper analysis of the influence of a company’s property rights and confirmed that SOEs are not receiving any particular special treatment. Thus, our overall conclusion is that China’s green credit policy is largely achieving its stated goals.

For environmental protection and high-quality economic development, issues such as building a green financial system need to be solved urgently. We believes that rely on the existing financial information system to build a data sharing platform for relevant functional departments. Use modern means such as big data and blockchain to build a green information dynamic collection mechanism. Encourage enterprises to disclose environmental protection information, incorporate green credit ratings into assessment indicators, and improve enterprises’ environmental awareness.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

WW contributed to the study design, including the conceptualization and methodology, prepared datasets, and promoted project administration. JM contributed to the resources, data analysis, and original draft preparation. SL proposed revisions during the final draft of the paper. LL contributed to the study’s organization, identifified the research methods, and performed the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the fifinal manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1“Green credit policy” and Green credit Guidelines in the text refer to the same policy.

2According to the green credit guidelines, industries with high pollution, high energy consumption and excess capacity will be defined as polluting enterprises. According to China Securities Regulatory Commission 2012 industry classification standard.Industry codes include: C25, C26, C30, C31, C32, C33, C34 and D44.

3The two industries refer to those with high pollution and energy consumption, whereas overcapacity refers to one with excess capacity. These industries mainly include steel, paper, electrolytic aluminum, plate glass, wind power and photovoltaic manufacturing industries (photovoltaic power generation, unlike the manufacturing industry, is not one of the these industries, and in fact is a clean energy industry encouraged by the state).

4The “two highs” refer to the resource-based industries with high pollution and high energy consumption; the overcapacity industries are those with overcapacity.

5“Ten thousand enterprises to help ten thousand villages” is designed to mobilize private enterprises to help poor villages, speed up the process of poverty alleviation, contribute to the development and growth of the non-public sector of the economy, and complete the task of building a prosperous society in all respects.

6Due to space limitations, the regression results were not presented. If necessary, it can be obtained from the author.

References

Aizawa, M., and Yang, C. (2010). Green credit, green stimulus, green revolution? China’s mobilization of banks for environmental cleanup. J. Environ. Dev. 19 (2), 119–144. doi:10.1177/1070496510371192

Bi, Q., Gu, L., and Zhang, J. (2015). Traditional culture, environmental system and corporate environmental information disclosure [J]. Account. Res. 94 (3), 12–19. Beijing.

Cai, Haijing (2013). Chinese green credit policy implementation status and effectiveness test-based on the empirical evidence of papermaking, mining and power industry. J. Finance Econ. (01), 69–75.

Du, X. (2015). Does confucianism reduce minority shareholder Expropriation?Evidence from China[J]. J. Bus. Ethics 132 (4), 661–716. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2325-2

Fang, X., and Li, J. (2019). Do commercial banks incorporate the environmental risk in loan pricing decision? Evidence from the environmental responsibility score. J. J. Finance Econ.

Fu, P. P., and Tsui, A. S. (2003). Utilizing printed media to understand desired leadership attributes in the People's republic of China[J]. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 20 (4), 423–446. doi:10.1023/a:1026373124564

Gu, Z. (2015). Confucian ethics and agency cost in the context of globalization [J]. Manag. World (3), 113–123. doi:10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2015.03.011

Jiang, X., and Xu, H. (2016). Research on green credit operation mechanism of Chinese commercial banks. J. China Popul. Resour. Environ. (S1), 490–492.

Kim, E. H., and Lyon, T. P. (2011). Strategic environmental disclosure: Evidence from the doe’s voluntary greenhouse gas registry. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 61 (3), 311–326. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2010.11.001

Li, L., Quanqi, L., Wang, J., and Hong, X. (2019). Carbon information disclosure, marketization, and cost of equity financing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16 (1), 225–235. doi:10.3390/ijerph16010150

Li, S., and Song, X. (2015). Pro-social preference, legitimacy pressure and social responsibility information disclosure: An empirical study based on Chinese private listed companies [J]. Guangzhou Acad. Res. 160 (8), 84–91.

Li, S., Song, X., and Wu, H. (2015). Political connection, ownership structure, and corporate philanthropy in China: A strategic-political perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 129 (2), 399–411. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2167-y

Ouyang, W. (2021). Finance helps the green development of the "14th Five-Year Plan" [J]. China Finance (08), 9–11.

Pérez-Orive, A. (2016). Credit constraints, firms’ precautionary investment, and the business cycle. J. Monet. Econ. 78, 112–131. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2016.01.006

Sonia, L. (2002). Environmental finance: A guide to environmental risk assessment and financial products. J. Transplant. 66 (8), 405–409.

Su, D., and Lian, L. (2018). Does green credit affect the investment and financing behavior of heavily polluting companies? J. Financial Res. (12), 123–137.

Wang, W., Zhao, C., Jiang, X., Huang, Y., and Li, S. (2020). Corporate environmental responsibility in China: A strategic political perspective. J. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 12, 220–239. doi:10.1108/sampj-12-2019-0448

Wu, H., Liu, Q., and Wu, S. (2017). Corporate environmental disclosure and financing constraints. J. World Econ. 40 (05), 124–147.

Xia, T., and Liming, Yu (2019). Environmental investment, environmental policy and allocative efficiency of green finance. J. J. Tech. Econ. Manag.

Xie, T., and Liu, J. (2019). How does green credit affect China’s green economic growth? J. China Popul. Resour. Environ. (09), 83–90.

Ye, L., and Fang, Y. (2021). Evolutionary game analysis on firms and banks’ behavioral strategies: Impact of environmental governance on interest rate setting. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 86, 106501. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2020.106501

Yu, X., and Wang, P. (2021). Economic effects analysis of environmental regulation policy in the process of industrial structure upgrading: Evidence from Chinese provincial panel data. Sci. Total Environ., 142004. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142004

Zhang, B., Yang, Y., Bi, J., and Yang, Y. (2011). Tracking the implementation of green credit policy in China: Top-down perspective and bottom-up reform. J. Environ. Manage. 92 (4), 1321–1327. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.12.019

Zhang, X., and Ge, J. (2021). Research on the optimization effect of dual resource allocation of green financial policy[J]. Res. Industrial Econ. (06), 15–28.

Zheng, Dengjin, and Yan, Tianyi (2016). Accounting conservatism, audit quality and debt cost. J. Audit Res. (02), 74–81.

Zhou, L (2007). Research on promotion tournament model of local officials in China. J. Econ. Res. (07), 36–50.

Zhou, P., Delmas, M. A., and Kohli, A. (2017). Constructing meaningful environmental indices: A nonparametric frontier approach. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 85 (09), 21–34. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2017.04.003

Keywords: national poverty alleviation strategy, policy regulation exemption, green credit guidelines, corporate finance, scale of corporate debt, maturity of corporate debt

Citation: Wang W, Ma J, Li S and Liu L (2022) National poverty alleviation strategy and policy regulation exemption: A quasi-natural experiment based on the green credit guidelines. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:955787. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.955787

Received: 29 May 2022; Accepted: 04 July 2022;

Published: 08 September 2022.

Edited by:

Shiyang Hu, Chongqing University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yonggen Luo, Guangdong University of Finance and Economics, ChinaLiu Xiangqiang, Southwest University, China

Copyright © 2022 Wang, Ma, Li and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lin Liu, NjUxNDUyNTk1QHFxLmNvbQ==

Wei Wang

Wei Wang Jingjuan Ma2

Jingjuan Ma2 Sihai Li

Sihai Li