- 1Shandong Technology and Business University, Yantai, China

- 2Faculty of Business and Management Sciences, The Superior University, Karachi, Pakistan

- 3School of Public Administration, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China

- 4Department of Business Administration, Sukkur IBA University, Sukkur, Pakistan

The deterioration of environmental quality has attracted the attention of the Chinese government and the public. The Chinese government has delegated part of the power of environmental regulation to local governments. To fulfill the KPI, local governments tend to loosen environmental regulations to attract more settlement of enterprises, thus leading to an increasingly fierce local environmental regulation competition. The improvement of people’s living standards makes it possible for the public to participate in environmental regulation. This article seeks to carry out the empirical study to interpret the relationship between local environmental regulation competition, public participation, and enterprise location selection through a random effects (RE) spatial Durbin model with 29 provincial panel data in China from 2004 to 2017. The results show that the provincial spatial spillover effect of enterprise location selection is significant. More intensified local environmental regulation competition can attract more investment but may harm sustainable economic development. Active public participation can effectively avoid the excessive investment caused by local environmental regulation competition and sustain economic development. Therefore, we should establish and improve the local environmental prevention and regulation system and establish an information disclosure mechanism to ensure public participation. The local government’s environmental regulation and public participation mechanism should be effectively coordinated.

1 Introduction

China’s economy has achieved rapid development in the past 40 years; however, the ecological environment is destroyed rapidly (Hao et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021; Irfan and Ahmad 2022). The deterioration of environmental quality has attracted the attention of the Chinese government and the public (Jinru et al., 2021; Abbasi et al., 2022; Fang et al., 2022). The government plays an irreplaceable leading role in environmental regulation (Duan et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020,2021). To reverse the trend of environmental deterioration, the Chinese government has also delegated environmental regulations to the provincial government (Wang et al., 2019; Rauf et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2022). The central government first determines the total emissions of pollutants and then decomposes them in each province (Qiu et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022). The provincial government has the goal and power to implement environmental regulations. This system promotes the principal–agent relationship between China’s central and local governments, whereas the central government cares more about sustainable economic development, but local governments pay more attention to immediate performance. To fulfill the KPI, local governments tend to loosen environmental regulations to attract more enterprises, thus leading to an increasingly fierce local environmental regulation competition (Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, the intensity of environmental regulation varies significantly in different provinces (Wu et al., 2020).

Enterprise behavior can be decoded in various aspects among which location selection (enterprise location selection) is regarded as one of the most essential reflection, while the decision of location selection is based on the lowest cost principle (Ahmad et al., 2021). Location selection is an important part of enterprise decision-making. The purpose of ideal location selection is to minimize the cost of production (Alfred, 2009). When local governments raise environmental regulation standards, it may lead the outflow of existing enterprises or hinder the inflow of foreign enterprises. However, the location choice of polluting enterprises largely depends on whether the growth of technological innovation income exceeds the cost of environmental regulation (Chandio et al., 2021; Irfan and Ahmad 2021; Tanveer et al., 2021). How does local environmental regulation affect the location choice of enterprises? Does the spatial heterogeneity in environmental regulation affect manufacturers’ choice of location? Will manufacturers’ location choices have different sensitivity to variation in local environmental stringency? (Wang et al., 2015). Hence, there exists controversial theoretical views about determinants of location selection and thus, it is quite interesting to examine the impact of environmental regulation on enterprise location choice especially in the case of China.

The essential influencing factors of environmental regulation are environmental regulation competition and public participation. Environmental regulation competition refers to the environmental deregulation of local governments to develop the local economy by attracting investment (Hauptmeier et al., 2012). Public participation is the abbreviation of public participation in environmental regulation, which refers to the spontaneous supervision and maintenance of the local environment by social groups based on government environmental regulation. They influence the location choice of enterprises through different paths. There are two controversial views in theory: Porter effect (PE) and pollution haven hypothesis (PHH). The Porter effect (PE) agrees that appropriate environmental regulation can stimulate enterprise innovation as well as reduce enterprise compliance costs and thus attract enterprise’s investment. Some scholars believe that stricter environmental regulations can guide enterprises to innovate independently and improve their competitiveness as well as offset the cost of environmental regulations to some extent (Lv et al., 2020). The pollution haven hypothesis (PHH) considers that environmental regulation increases the production cost of enterprises, thus crowding out the investment of enterprises (Dechezlepretre and Sato, 2017). The environmental regulation intensity varies in regions resulting from the fierce competition, which is extensively studied in the literature. It is generally believed that ‘pollution heaven’ (PH) is a result of an intensified local environmental regulation competition; according to it, enterprises make investment decisions. Commonly, enterprises are located in a region with loosened environmental regulations (Porter and Linde, 1995; Liu et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018). The main reason is that environmental regulations lead to an increase in the production costs (Li et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2020), which reduces the competitiveness of enterprises (Hu et al., 2020).

The impact of environmental regulation competition on the location choice of enterprises is also controversial in the empirical aspect. The disputes mainly focus on the following aspects. First, the measurements of environmental regulation competition are controversial due to its complexities and multidimensional characteristics (Kheder and Zugravu, 2012; Antonietti et al., 2017). As different environmental regulations typically involve various pollutants and even the same regulation has different pollution standards across different regions, measuring environmental regulations in any meaningful way is a difficult task (Ben Kheder and Zugravu, 2012). A lot of studies, such as the work of Antonietti et al. (2017), Wu et al. (2017), Zhou et al. (2017), and Dou and Han, (2019), measured environmental regulation competition through a single proxy variable, which led to the risk of measurement error bias (Ben Kheder and Zugravu, 2012; Wang et al., 2019). Nevertheless, there are studies that gauge environmental regulations quite broadly, such as the range of development dimensions, which is clearly beyond the basic meaning of environmental regulation (Wang et al., 2019). Second, disputes on the measurement of enterprise location choice. There are a lot of existing studies, such as the work of List et al. (2003), Mulatu et al. (2010), Mulatu and Wossink (2014), Cai et al. (2016), Chen and Xu (2017), Sarkodie and Strezov (2019), and Wu et al. (2020), which analyzed the effects of variation in environmental regulations on enterprise location selection by using aggregate data on economic activities such as net investment, share of gross output, employment growth, or several new firms (Wang et al., 2019), with the exception of few notable studies (see, for instance, Levinson and Taylor, 2008; Kheder and Zugravu, 2012; Wu et al., 2016). Third, disputes over sample selection differences. Sample differences lead to controversial conclusions, such as developed or developing samples, pollution-intensive enterprises or not, and spatial heterogeneity differences of pollutants (Zhao, 2014). The data analyses of non-state-owned enterprises in Eastern China, the United States, Canada, Mexico, and Turkey are consistent with PHH (Akbostanci et al., 2007; Quiroga et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2018) and believe that loose environmental regulations do reduce environmental costs burn by enterprises while are rejected in studies of BRICS and MINT countries (Zhou et al., 2017). Fourth, endogenous disputes. Endogeneity leads to the controversy of empirical results including bidirectional causality (Shi and Xu, 2018) and omitted variables. For instance, a certain case study of the United States rejects PHH (Levinson and Pace, 2008), which might be due to the difference of statistical and research methods (Smarzynska and Wei, 2001; Jeppesen et al., 2010) or the omission of variables such as public participation (Xiao, 2008; Zhao, 2014), transportation convenience, labor availability, and cost (Holl and Mariotti, 2018; Castellani and Lavorati, 2019; Li et al., 2019).

Empirical studies conclude that public participation has a significant impact on the location choice of enterprises (Kostka and Mol, 2013; Zheng et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2016). Public participation is even indirectly involved in enterprise decision-making, but its influential power cannot be overlooked (Su et al., 2018). Current studies on environmental regulations and public participation are concluded into three aspects. First, there are disputes on the effectiveness of public participation. According to supporters, enterprises volunteer to reduce pollution in an affluent region with higher income and education levels (Gamper, 2006), where the government often organizes environmental public hearings and forces the polluting enterprises to relocate. The opponents agree that public participation plays a certain role (Xiao, 2019), but the effectiveness is limited (Xu, 2014; Zhang and Guo, 2015) due to its weak financial and legal restrictions (Carreira et al., 2016; Porter, 2017). Wu et al. (2016) believed that public participation with significant concerns in physical health and quality of life exerts a limited impact on environmental regulations. Second, the influencing factors of public participation are well researched. The popularity of the internet helps to restrict government behavior, improve government’s response to public needs, and enhance the public’s awareness of environmental protection (Zhang et al., 2022). The openness of government affairs is necessary. It promotes the openness and transparency of government regulation and public accountability (Pérez-Morote et al., 2020) and encourages the public to participate in and supervise environmental regulation. Third, the classification of public participation is well researched. Xiao (2008) classified public participation into three types: citizen-dominated participation (or civil litigation), media-dominated participation, and NGO-dominated participation. Xue and Dong (2010) divided it into ex ante participation (for instance, public participation in environmental impact assessment) and ex post participation (for example, public tip-offs). Fourth, the interaction between environmental regulation competition and public participation and its impact on the location choice of enterprises is well researched. Public participation or attention can alleviate the intensity of environmental regulation between different regions by affecting the government’s environmental regulation behavior, including attracting the government’s attention to environmental problems, increasing the government’s investment in environmental management, and improving government supervision (Long et al., 2022). The Chinese government should establish an environmental regulation system of “government-led, public, and enterprise collaborative participation” (Tian et al., 2016). The research in this study is based on the understanding that the government and the public jointly constitute China’s environmental regulation cooperation model (Chen and Xu, 2017). Last, the impact of public participation on the location choice of enterprises is different in different regions. The public in developed regions of China has a strong awareness of environmental protection, easier to be united to clamp down on enterprises to comply with regional environmental regulations or even force polluting enterprises to relocate.

To sum up, this study improves the existing research. First, there are significant disputes about index measurement and sample selection, which is supplemented in this study. As a large economy and a developing country in the world, China is very representative. This study selects Chinese samples to supplement and demonstrate this topic. This study selects several indicators to supplement and demonstrate environmental regulation competition, public participation, and enterprise location selection. This study also makes an empirical test combined with enterprise heterogeneity. Second, there is less existing research on the interaction between environmental regulation competition and public participation. This study complements the interaction between the two and further demonstrates the mechanism of the two on the location choice of enterprises. Third, the existing research is less focused on the research of the spatial spillover effect. There are 34 provinces and autonomous regions in China, and there are significant spatial spillovers between different provinces. This study introduces a spatial econometric model to demonstrate this combined with China’s special samples.

This study comprises five sections. Our first section consists of introduction and literature review. The second section is based on theory analysis and research hypothesis. In the third section, empirical model and data sources are presented. The fourth section shows the findings of the regression and robust test results. The study ends with conclusions and prospects.

2 Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

To improve the investment environment and attract foreign investment, local governments tend to loosen environmental policies much more than potential competitors to gain competitive advantages among regions (Deng and Xu, 2013; Deng and Sang, 2015; Wang, 2015). As a result, a “pollution heaven” is formed at the expense of the environment with the pursuit of political promotion and economic development (Ayadi et al., 2019). However, environmental regulations in developing countries generally suffer supervision and implementation inefficiency, which leads to insufficient environmental regulations (Blondiau and Rousseau, 2010; Han, 2014). Public participation is regarded as the environmental ethics; therefore, it becomes an important supplement to the legal system (Liu et al., 2019). The discussion of the relation between them is categorized into two aspects: well-recognized superimposing relation and crowding out relation. Regional environmental laws and regulations are formed with the participation of the public and the government. China manages them in accordance with formal environmental laws and regulations. Public participation is regarded as a moral supplement to the legal system. Therefore, the superposition relationship between them can be proved (Zheng et al., 2018). However, excessive government regulation has a strong crowding out effect on public participation. Governmental regulations and public participation are relatively independent. When public participation is involved in an environmental issue, it may no longer be a major concern for local governments, indicating the crowding out relationship between them (Wang, 2016; Xiao, 2019). In China, eastern coastal regions are more economically developed where residents concern more on the environment with stronger legal awareness of environmental protection, therefore participating more voluntarily in environmental supervision. As a result, environmental disparities are formed among the regions. The level of local public participation is an important factor that enterprises should consider when making location selections (Xiao, 2008).

2.1 Environmental Regulation Competition and Enterprise Location Selection

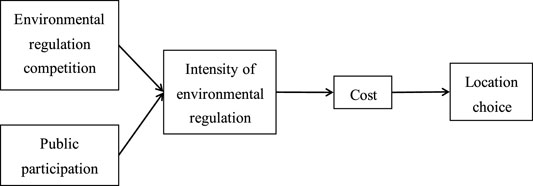

Environmental regulation competition and public participation affect the production cost of enterprises through the intensity of regional environmental regulation and then affect the enterprise location choice. The transmission path is shown in Figure 1. Local officials may only focus on economic growth during their term of office and tend to unilaterally pursue short-term economic development while ignoring environmental pollution (Zhou et al., 2017). Local governments have incentives to lower local environmental regulations, attract pollution-intensive enterprises with short investment cycles and resource dependence, and adopt extensive economic growth at the cost of environmental damage. There is even a vicious cycle in which local governments compete to lower the level of environmental regulations to attract pollution-intensive enterprises (Wang et al., 2019). Based on the aforementioned analysis, hypothesis 1 is proposed.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): the more intense the environmental regulation competition is, the lower the local environmental regulation intensity will be and more enterprises will be attracted to locate.

2.2 Public Participation and Enterprise Location Selection

According to the public goods supply theory, when residents’ marginal willingness to pay for environmental public goods is equal to the marginal cost of environmental public goods supply, residents are willing to sacrifice private consumption to increase the supply of environmental public goods (Fung, 2006). Theoretically, there is the possibility of private provision of environmental public goods. At the same time, the more active the public is in participating in environmental regulation, the higher the cost will be (Sun et al., 2016). Practice shows that residents in developed areas are more sensitive to environmental quality and willing to pay higher costs for environmental regulation. Therefore, there are differences in the degree of public participation in environmental regulation in different regions. The higher the degree of public participation, the higher the level of environmental regulation, and enterprises tend to avoid such areas in location choice. Therefore, hypothesis 2 is proposed.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): the lower the level of public participation is, the lower the environmental costs will be, and more enterprises will be attracted to locate.

2.3 Interaction Between Environmental Regulation Competition and Public Participation

The process of enterprise location selection involves three market players: local government, public, and an enterprise. The local government maps out environmental regulations based on pollution discharge fees. The fiercer the competition of environmental regulation, the lower the environmental regulation intensity will be. Local residents as public participation complement governmental environmental regulation’s insufficiency (Fung, 2006). The efforts to shape environmental regulations from local residents depend on the environmental governance level. More specifically, a well-functional environmental regulation system founded by governments reduces the participation from local residents, that is, the participation to optimize environmental regulations is costly in terms of time and money. As long as the government supply is sufficient, the private supply from the public is ignored (Thomas, 2013). Only when the governance is insufficient, the private sector, namely, the residents would contribute (Drazkiewicz et al., 2015). Finally, the enterprise selects its location and optimal output according to the levels of local environmental regulation competition and public participation (Wang, 2015).

Hypothesis 3 (H3): there is an interaction between environmental regulation competition and public participation.

3 Data Sources and Statistical Description

The theoretical framework is constructed to investigate the effect of local environmental regulation competition and public participation on enterprise location selection. With different development levels of eastern and western regions in China, enterprises select their locations regarding to local socio-economic indicators and geographical advantages. Thus, the spatial factor should be involved in the theoretical framework. The spatial error model (SEM), spatial lag model (SLM), and spatial Durbin model (SDM) are adopted in the research.

The data are collected from the Chinese Environment Yearbook; China Environment Statistical Yearbook; China Labor Statistical Yearbook; China Statistical Yearbook; Sample Survey of Urban Households; and Survey of Income, Expenditure and Living Conditions of Integrated Urban and Rural Households by the National Bureau of Statistics from 2004–2017. Tibet and Hainan provinces are not included in the research because of missing data. All data are deflated according to corresponding indexes by using the year 2004 as the base year (including GDP deflator, producer price index, fixed investment price index, and consumer price index). Also, some missing data are estimated by using the average over the past 3 years.

3.1 Explained Variable INVE

The local governments attract enterprise investment (mainly fixed assets investment) by loosening environmental regulations to promote economic development. Thus, fixed assets investment can be used to measure enterprise location selection. Considering the heterogeneity of enterprises, investment in China mainly includes state-owned investment; foreign investment; Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan investment; and private investment. The data of the first three come from China Fixed Assets Statistical Yearbook. However, private investment lacks effective data, calculated by subtracting state-owned investment; foreign investment; Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan investment from fixed assets investment. Because of the statistical measurement changes and errors around 2011, private investment is negative in some year and regarded as zero in our empirical analysis. Therefore, the explained variables in our study include total investment (

3.2 Explaining Variable ER

It is difficult to directly measure the level of local environmental regulation competition. Nevertheless, it is inversely proportional to environmental regulation intensity, that is, the higher the level of competition among regions, the lower the level of environmental regulation intensity. Hence, environmental regulation intensity indicators can be used to reflect the level of local environmental regulation competition. Referring to the calculation method of Xiao (2008) and Zhang et al. (2010), the measurement of environmental regulation intensity can be captured from three indicators in the perspective of production cost: pollution prevention and control investment (PCI), average pollution discharge fees (APC), and total environmental regulation costs faced by enterprises (ERC). The PCI is selected based on the principle of “polluter pays”. It is the percentage of industrial pollution prevention and control investment in total local fixed assets investment, which reflects fixed assets investment provided by the government for local environmental pollution remediation. APC is obtained from dividing pollution discharge fees by the number of large-scale local industrial enterprises. All data is collected from the Chinese Environmental Yearbook and China Environmental Statistics Yearbook, and it is deflated to the price index. ERC comprehensively measures total environmental regulation costs per 10,000 RMB of industrial-added value. It is the sum of pollution discharges, industrial pollution prevention, and control investment divided by local industrial-added value.

3.3 Explaining Variable PUB

Since the main force of public participation is well-educated young generations, the study refers to the measurement adopted by Pargal and Wheeler (1996) and Yuan and Xie (2014). Per capita urban disposable income (DPI), proportion of residents with a college education or above (CEA), and urban population density (UPD) are leveraged in the research. Generally, people with higher income prefer better living quality and environment (Pargal and Wheeler, 1996; Antweiler et al., 2001) and vice versa. The income of residents is a key indicator of public participation. The data are obtained from the survey of income, expenditure, and living conditions of integrated urban and rural households by the National Bureau of Statistics. The urban consumer price index is used for deflation. Residents with higher levels of educational backgrounds have more vital environmental awareness and higher public participation willingness. The proportion of residents with college education or above in the total population of the country are selected from the national sample population sampling survey data. The missing data in 2010 is estimated by the average between 2009 and 2011. The more the population density, the more residents are influenced by environmental pollution and consequently, the higher the level of public participation would be. The number of the urban resident population per unit area is taken into consideration at the end of the year. The missing data of the urban areas are approximated with data of the year before and after. The missing data of urban population in 2004 is estimated by the average growth rate over the last 3 years.

3.4 Control Variable Z

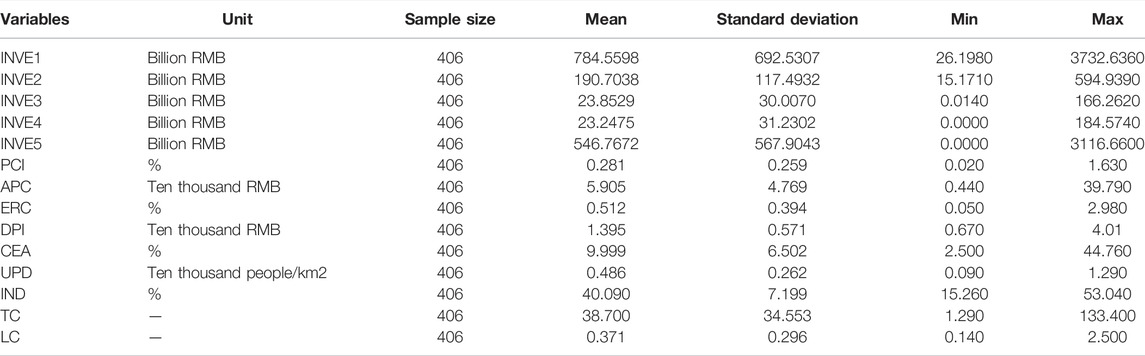

The factors affecting enterprise location selection also include the level of local economic development (IND), transportation convenience (TC), and labor cost (LC). The level of local economic development affects enterprises’ long-term development and products’ potential demand. It is usually measured by the level of industrialization and equals the proportion of industrial-added value in GDP. Transportation convenience (TC) affects enterprises’ transportation costs, which are divided into the total mileage of railway, highway, and waterway by the total area. Labor cost (LC) is an important part of the production cost and represented by the proportion of total wages of urban employees and industrial-added value. The data of total wages of urban employees in 2004 and 2005 were missing in several provinces, which are obtained by using average growth rate in recent 3 years. Descriptive statistics of variables are shown in Table 1.

3.5 Spatial Weight Matrix

The spatial weight matrix is exogenous whose setup is the key to the spatial econometric analysis (Sun and Li, 2008). There are three kinds of spatial competition for enterprise location selection: nationwide competition, inner-regional competition, and interregional economic competition (Zhao, 2014). Correspondingly, the spatial weight matrix should also be selected between the adjacency matrix, geospatial matrix, and economic spatial matrix (Xiao, 2019). To enhance the robustness, all three spatial weight matrices are selected for analysis in our study. The adjacency matrix is set as

3.6 Spatial Correlation Test

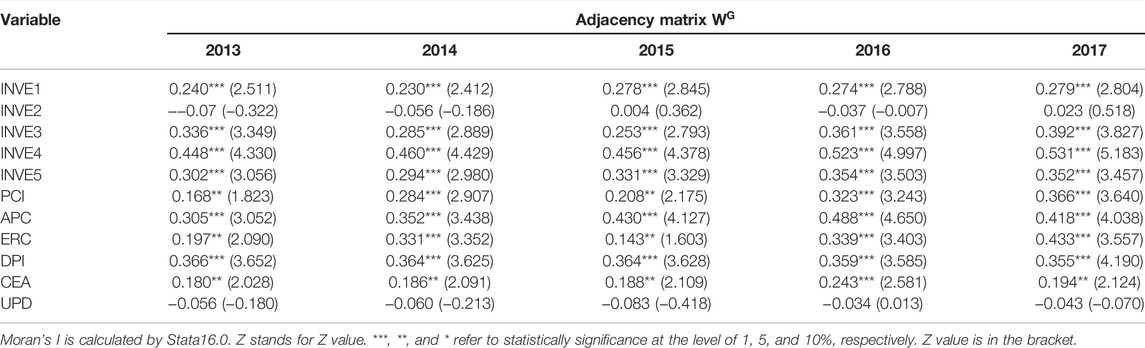

The spatial effect of enterprise location selection is mainly reflected in spatial correlation and spatial heterogeneity, which can be measured by the global Moran’s I. To reduce the data fluctuation and remove the dimensional influence, the test and regression data in our study are treated with a logarithm. We take the adjacency matrix as an example to calculate the global Moran’s I from 2014 to 2017, and the estimated results are shown in Table 2.

The results show significant positive spatial correlation between enterprise location selection and local environmental regulation competition and public participation, which in general verifies the necessity and feasibility of choosing a spatial measurement model for research.

4 Modeling and Testing

4.1 Benchmark Model Setting

Since both SEM and SLM are special forms of SDM, we choose SDM first (Wang, 2019), and LM-error and LM-lag are used to test whether it should be degraded to SEM or SLM. Referring to SDM proposed by Le and Pace (2009), we established a benchmark model as follows:

where

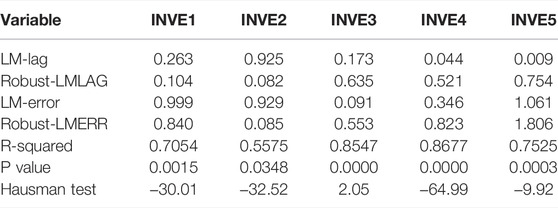

4.2 Model Selection

On the basis of OLS, the LM test is carried out to check the significance of LM-error and LM-lag. Then, fixed and random effects analyses are carried out by using the Housman test. The results are shown in Table 3. The results show that both LM-error and LM-lag tests reject the hypothesis, that is, the spatial model should not degenerate into SEM or SLM, so SDM should be selected. The results of the Housman test cannot reject the hypothesis, and SDM with random effects should be selected.

4.3 Model Expansion

In order to avoid the endogeneity and missing variables, we adopt the actual data of one period lag (

Considering the interaction between local environmental regulation competition and public participation, we introduce an interaction term to measure it. In the interaction item, ERC is selected to represent local environmental regulation competition, and DPI is selected to represent public participation. Formula 10 becomes

4.4 Empirical Results and Robustness Testing

Under the three spatial weight matrices, we adopt the maximum likelihood method and use random effects SDM to test the data of INVE1, INVE2, INVE3, INVE4, and INVE5.

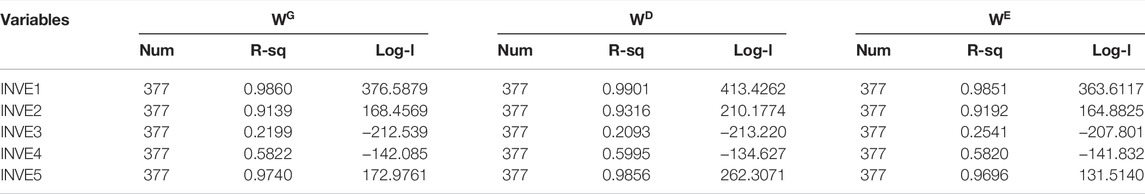

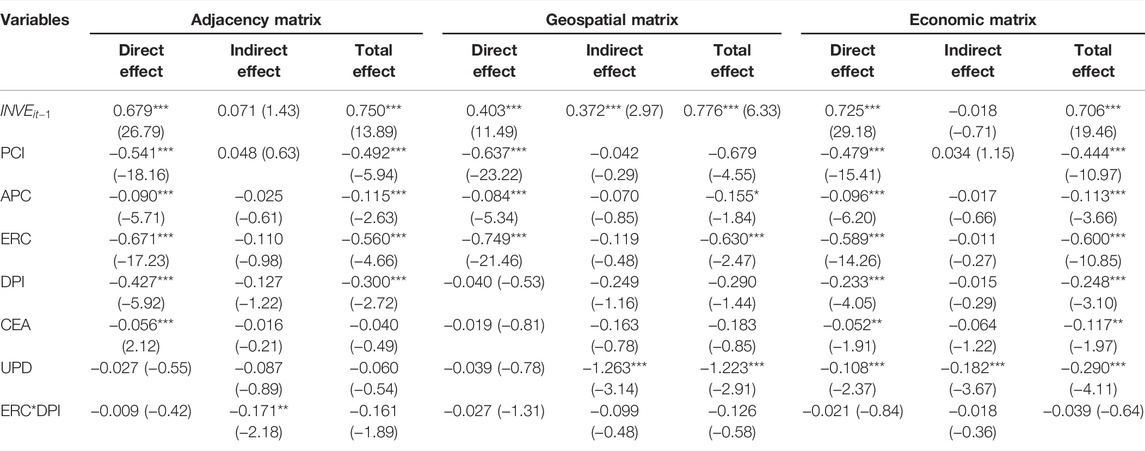

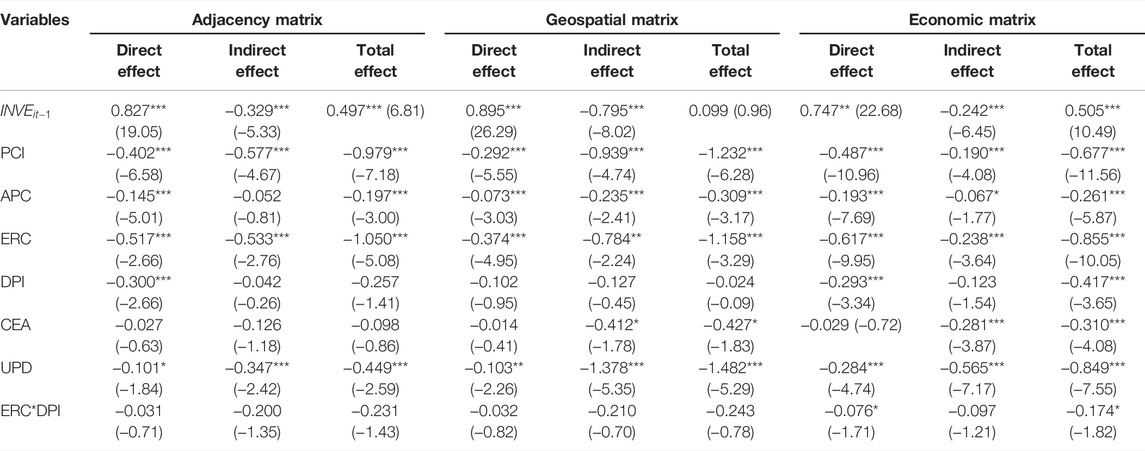

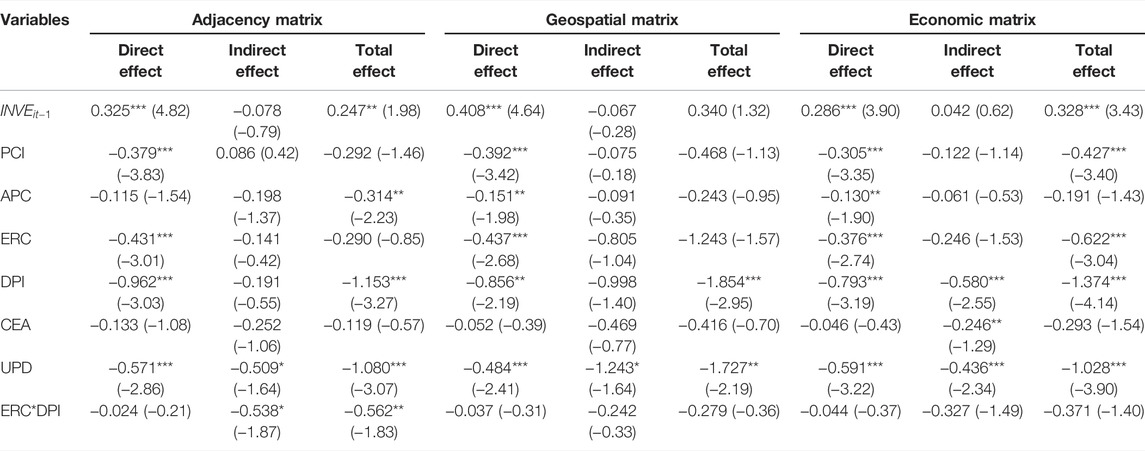

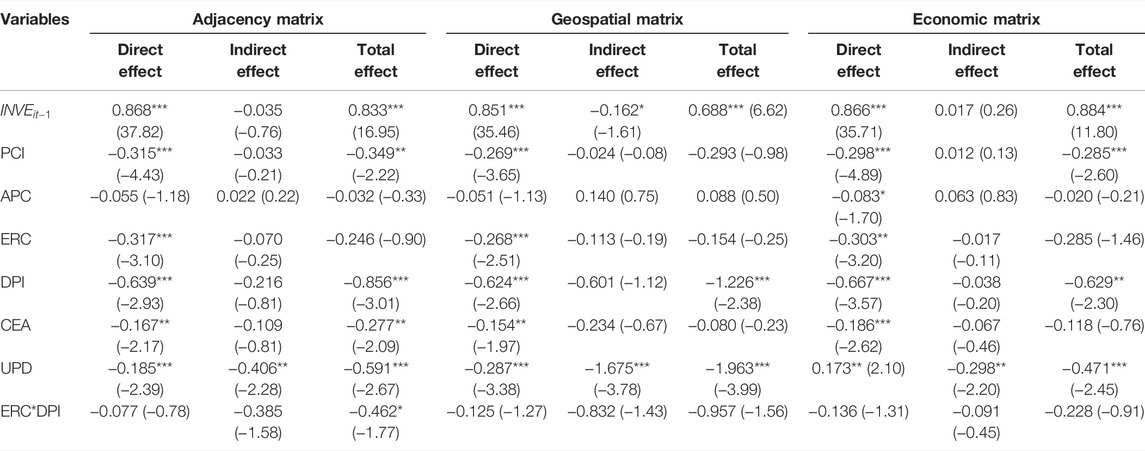

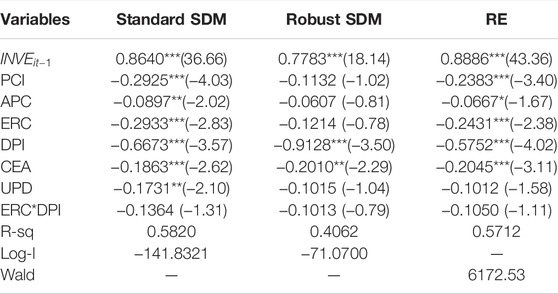

Table 4 lists statistics of the random effects SDM under the three spatial matrices. Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, and Table 9 display the result estimations. According to R-sq., the fitting effect of the economic matrix is the best. Thus, the economic matrix is taken as an example to analyze the regression results of INVE1, INVE2, INVE3, INVE4, and INVE5.

The total effects of PCI, DPI, and ERC (local environmental regulation competition) are significantly negative at 5 and 1% levels of significance. The more intensified the local environmental regulation competition, the lower the environmental regulation intensity and the more the investment is, which is in line with H1. The direct and indirect effects of PCI, APC, and ERC are significantly negative. A more intensified local environmental regulation competition attracts local investment and increases investment in economically related provinces. The coefficients of direct, indirect, and total effects of PCI are greater than that of APC, indicating that PCI has a greater impact on enterprise location selection than APC.

The total effects of DPI, CEA, and UPD (representing public participation) are significantly negative. The higher the level of public participation, the less investment will be, verifying H2. The direct and indirect effects of DPI, CEA, and UPD are all negative. A higher level of public participation not only restrains local investment but also reduces investment in economically related provinces. In terms of the coefficients of the total effect, UPD ranks first, followed by DPI and CEA, respectively. In terms of the coefficients of direct effect, DPI is the highest, followed by UPD and CEA, respectively. In terms of the coefficients of indirect effect, UPD is the highest, followed by CEA and DPI, respectively.

The total effect of ERC*DPI is negative, which indicates that the interaction term has a negative impact on enterprise location selection, which verifies H3. Both the direct and indirect effects are negative. The interaction term not only restrains local investment but also reduces investment in economically related provinces. The coefficient of direct effect is higher than that of indirect effect, which means the interaction term restrains local investment more. The absolute value difference between the direct and indirect effects of the five types of enterprises is very small, which also verifies the strong spatial spillover effect of enterprises under the background of economic integration.

Enterprise heterogeneity does not lead to significant differences in the results of random effects nor does it affect the significance. According to the decomposition of random effects, the top three factors affecting state-owned investment are total environmental regulation costs, urban population density, and pollution control and prevention cost. The top three impact factors on foreign investment are urban population density, urban disposable income, and total environmental regulation cost; the top three impact factors on private investment are urban disposable income, urban population density, and pollution prevention and control investment; the top three factors on Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan investment are total environmental regulation cost, pollution control, and prevention cost and the proportion of residents with college education or above.

4.5 Robustness Tests

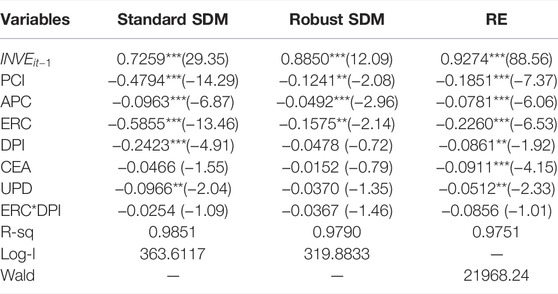

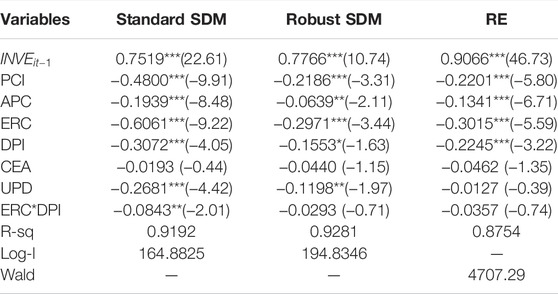

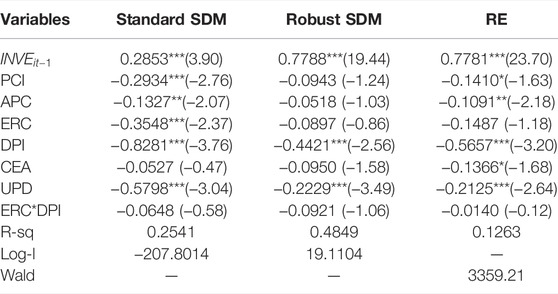

4.5.1 Eliminating Other Interference Items

Our research covers the extensive time-series data from 2004 to 2017 annually. Thus, changing national and provincial policies inevitably affects our regression results. Therefore, the impact of other interference items needs to be controlled. The interference can be effectively eliminated by shortening the data collection period. ‘The Cleaner Production Promotion Law of the People’s Republic of China was amended and implemented in 2012. It is a relatively authoritative legal document in the field of environmental regulation, which may cause a great disturbance to the research results before and after its implementation. The data from 2004 to 2012 are selected for the robustness test as displayed in Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13, and Table 14, respectively. The results show that there are no significant changes in the direction and significance of the coefficients, which are consistent with the benchmark regression results. It provides robustness checks to our regression results.

4.5.2 Robustness Test for a Panel Data Model

To avoid the estimation error caused by the wrong model selection, we use a random effects (RE) panel data model for the robustness test. The results are reported in Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13, and Table 14, respectively.

Although there are some changes in the magnitude and significance of some coefficients, the direction of impact remains constant. So it ensures the consistency of research results even measured with varied methods, namely, the robustness of the research.

5 Conclusion

Based on the panel data of 29 provinces in China from 2004 to 2017 annually, the study leverage SDM to carry out the empirical analysis on the relationship between local environmental regulation competition, public participation, and enterprise location selection. The results show that, first, the spatial spillover effect of environmental regulation competition and public participation on enterprise location choice is significant. It means that environmental regulation and public participation in one region have a significant impact on the location choice of enterprises in other regions. When local governments make environmental regulation policies, they should pay attention to the spatial spillover effect. Second, environmental regulation competition has a negative impact on the location choice of enterprises. It indicates that the more intense the competition is, the lower the intensity of local environmental regulation will be, and more enterprises will be attracted to locate. However, although environmental regulation competition can bring more investment, it is not conducive to the sustainable development of economy. Among the indicators of environmental regulation competition, the coefficient of the investment in pollution prevention and control is the largest and has the greatest impact on the location choice of enterprises. Third, the total effect of public participation on enterprise location choice is significantly negative, which means that the higher the level of public participation is, the less enterprise investment will be. Active public participation can effectively avoid the excessive investment caused by local environmental regulation competition and sustain economic development. Among the indicators of public participation, urban population density and urban disposable income index have a greater impact on enterprise location selection. Fourth, the regression results of the heterogeneity of enterprises are significant. The results show that pollution control investment and urban population density greatly affect state-owned investment. Foreign investment is more susceptible to the level of public participation that pays attention to urban population density and urban disposable income; private investment emphasizes urban disposable income and urban population density. The investment from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan attaches more importance to pollution control investment and education level.

Economic sustainability can be achieved through shifting the mechanism of environmental regulation from pollution emission control system to a precautionary system. Therefore, this study proposes the following policy recommendations. First of all, a functional pollutant discharge system should be built upon enterprises, to reinforce the regulation implementation and prevent environmental deterioration. Second, pollution control investment should be enhanced to strengthen the environmental prevention capacity, therefore building a sound socio-ecological environment for the settlement of low-pollution enterprises. Finally, a special fund should be set up to encourage local enterprises to transfer into the environmental-friendly economy, preventing pollution radically.

Beyond them, it is necessary to improve the environmental information disclosure mechanism by establishing diversified communication platforms in order to enroll more participators. With the rapid development of multimedia, it is more convenient for the public to get involved in the events and raise common awareness. Meanwhile, multimedia acts as a double sword, the informal report in which might mislead the public as well arouse the wave of protest. Even so, it is believed that the environmental information disclosure mechanism should be improved, and unobstructed communication channels should be established to the informative to the public. Further, local governments should improve the feedback mechanism for public participation, and promotes the coordination between local governments’ environmental regulations and public participation. Local environmental regulation competition and public participation have mutual influence and complement each other. The time-feedback of public participation can facilitate local governments to dynamically adjust the environmental regulation intensity, standard investment from different types and achieve economic sustainable development.

This study is subject to some limitations, which is also the research direction in the future. First, we do not use enterprise data. In the next step, we will investigate the willingness of enterprises and test it with enterprise data. Second, the study of interaction effect between environmental regulation competition and public participation is not deep enough. We will discuss the interaction with more detailed variables. Third, the impact of environmental regulation on enterprise location selection maybe distinguished between short term and long term, which can be studied further.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

XM: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, and writing—original draft. ZQ: data curation and visualization. WA: visualization and editing. MKA writing and review. ZH: writing and review. AA: review and editing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbasi, K. R., Shahbaz, M., Zhang, J., Irfan, M., and Alvarado, R. (2022). Analyze the Environmental Sustainability Factors of China: The Role of Fossil Fuel Energy and Renewable Energy. Renew. Energy 187, 390–402. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.01.066

Ahmad, B., Da, L., Asif, M. H., Irfan, M., Ali, S., and Akbar, M. I. U. D. (2021). Understanding the Antecedents and Consequences of Service-Sales Ambidexterity: a Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) Framework. Sustainability 13 (17), 9675. doi:10.3390/su13179675

Akbostanci, E., Tunç, G. I., and Türüt-Asik, S. (2007). Pollution Haven Hypothesis and the Role of Dirty Industries in Turkey's Exports. Envir. Dev. Econ. 12, 297–322. doi:10.1017/S1355770X06003512

Antonietti, R., De Marchi, V., and Di Maria, E. (2017). Governing Offshoring in a Stringent Environmental Policy Setting: Evidence from Italian Manufacturing Firms. J. Clean. Prod. 155, 103–113. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.11.106

Antweiler, W., Copeland, B. R., and Taylor, M. S. (2001). Is Free Trade Good for the Environment? Am. Econ. Rev. 91, 877–908. doi:10.1257/aer.91.4.877

Ayadi, F. S., Mlanga, S., Ikpor, M. I., and Nnachi, R. A. (2019). Empirical Test of Pollution Haven Hypothesis in Nigeria Using Autoregressive Distributed Lag (Ardl) Model. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 10 (3), 48–58. doi:10.2478/mjss-2019-0041

Blondiau, T., and Rousseau, S. (2010). The Impact of the Judicial Objective Function on the Enforcement of Environmental Standards. J. Regul. Econ. 37, 196–214. doi:10.1007/s11149-009-9113-4

Carreira, V., Machado, J. R., and Vasconcelos, L. (2016). Legal Citizen Knowledge and Public Participation on Environmental and Spatial Planning Policies: a Case Study in Portugal. Int. J. Humanit Soc. Sci. Res. 2, 28–33.

Castellani, D., and Lavoratori, K. (2019). “Location of R&D Abroad-An Analysis on Global Cities,” in Relocation of Economic Activity. Editors P. Capik, and M. Dej (Springer, Cham), 145–162. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92282-9_9

Chandio, A. A., Jiang, Y., Akram, W., Adeel, S., Irfan, M., and Jan, I. (2021). Addressing the Effect of Climate Change in the Framework of Financial and Technological Development on Cereal Production in Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 288, 125637. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125637

Chen, J., and Xu, Y. (2017). Why Do Authoritarian Regimes Allow Citizens to Voice Opinions Publicly? J. Polit. 79, 792–803. doi:10.2139/ssrn.231805110.1086/690303

Dechezleprêtre, A., and Sato, M. (2017). The Impacts of Environmental Regulations on Competitiveness. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 11 (2), 183–206. doi:10.1093/reep/rex013

Deng, H., and Sang, B. (2015). Fiscal Decentralization, Environmental Regulation and FDI Competition Among Local Governments. J Shanghai Univ. Finance Econ 17, 79–88. doi:10.16538/j.cnki.jsufe.2015.03.004

Deng, Y., and Xu, H. (2013). Foreign Direct Investment, Local Government Competition and Environmental Pollution: Empirical Analysis on Fiscal Decentralization. China Popul Res Environ 23, 155–163. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-2104.2013.07.024

Dou, J., and Han, X. (2019). How Does the Industry Mobility Affect Pollution Industry Transfer in China: Empirical Test on Pollution Haven Hypothesis and Porter Hypothesis. J. Clean. Prod. 217, 105–115. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.147

Drazkiewicz, A., Challies, E., and Newig, J. (2015). Public Participation and Local Environmental Planning: Testing Factors Influencing Decision Quality and Implementation in Four Case Studies from Germany. Land Use Policy 46, 211–222. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.02.010

Duan, X., Dai, S., Yang, R., Duan, Z., and Tang, Y. (2020). Environmental Collaborative Governance Degree of Government, Corporation, and Public. Sustainability 12 (3), 1138. doi:10.3390/su12031138

Fang, Z., Razzaq, A., Mohsin, M., and Irfan, M. (2022). Spatial Spillovers and Threshold Effects of Internet Development and Entrepreneurship on Green Innovation Efficiency in China. Technol. Soc. 68, 101844. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101844

Fung, A. (2006). Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance. Public Adm. Rev. 66, 66–75. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00667.x

Gamper-Rabindran, S. (2006). Did the EPA's Voluntary Industrial Toxics Program Reduce Emissions? A GIS Analysis of Distributional Impacts and By-Media Analysis of Substitution. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 52, 391–410. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2005.12.001

Han, C. (2014). Institutional Influence, Regulatory Competition and China's Enlightenment-Analysis on the Causes of Regulation Failure. Econ. Perspect. 4, 66–76.

Hao, Y., Gai, Z., Yan, G., Wu, H., and Irfan, M. (2021). The Spatial Spillover Effect and Nonlinear Relationship Analysis between Environmental Decentralization, Government Corruption and Air Pollution: Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 763, 144183. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144183

Hauptmeier, S., Mittermaier, F., and Rincke, J. (2012). Fiscal Competition over Taxes and Public Inputs. Regional Sci. Urban Econ. 42, 407–419. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2011.10.007

Holl, A., and Mariotti, I. (2018). The Geography of Logistics Firm Location: the Role of Accessibility. Netw. Spat. Econ. 18, 337–361. doi:10.1007/s11067-017-9347-0

Hu, J., Huang, Q., and Chen, X. (2020). Environmental Regulation, Innovation Quality and Firms' competitivity―Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on China's Carbon Emissions Trading Pilot. Econ. Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 33, 3307–3333. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2020.1771745

Irfan, M., and Ahmad, M. (2022). Modeling Consumers' Information Acquisition and 5G Technology Utilization: Is Personality Relevant? Personality Individ. Differ. 188, 111450. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111450

Irfan, M., and Ahmad, M. (2021). Relating Consumers' Information and Willingness to Buy Electric Vehicles: Does Personality Matter? Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 100, 103049. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2021.103049

Javorcik, B. S., and Wei, S.-J. (2003). Pollution Havens and Foreign Direct Investment: Dirty Secret or Popular Myth? NBER Work. Pap. 3, 1244. doi:10.2202/1538-0645.1244

Jeppesen, T., List, J. A., and Folmer, H. (2002). Environmental Regulations and New Plant Location Decisions: Evidence from a Meta‐Analysis. J. Regional Sci. 42, 19–49. doi:10.1111/1467-9787.00248

Jinru, L., Changbiao, Z., Ahmad, B., Irfan, M., and Nazir, R. (2021). How Do Green Financing and Green Logistics Affect the Circular Economy in the Pandemic Situation: Key Mediating Role of Sustainable Production. Tianjin, China: Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 1–21. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2021.2004437

Kostka, G., and Mol, A. P. J. (2013). Implementation and Participation in China's Local Environmental Politics: Challenges and Innovations. J. Environ. Policy & Plan. 15, 3–16. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2013.763629

Lesage, J., and Pace, R. K. (2009). Introduction to Spatial Econometrics. Florida: CRC Press. doi:10.1111/j.1467-985X.2010.00681_13.x

Levinson, A., and Taylor, M. S. (2008). Unmasking the Pollution Haven Effect. Int. Econ. Rev. 49, 223–254. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2354.2008.00478.x

Li, H., and Li, B. (2019). The Threshold Effect of Environmental Regulation on the Green Transition of the Industrial Economy in China. Econ. Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 32, 3134–3149. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2019.1661001

Li, Y., Hernandez, E., and Gwon, S. (2019). When Do Ethnic Communities Affect Foreign Location Choice? Dual Entry Strategies of Korean Banks in China. Amj 62 (1), 172–195. doi:10.5465/amj.2017.0275

Lin, G., Long, Z., and Wu, M. (2006). A Spatial Investigation of σ-convergence in China. J Quant Tech Econ 23, 14–21. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3894.2006.04.002

Liu, L., Bouman, T., Perlaviciute, G., and Steg, L. (2019). Effects of Trust and Public Participation on Acceptability of Renewable Energy Projects in the Netherlands and China. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 53, 137–144. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.03.006

Liu, Q., Wang, S., Zhang, W., Zhan, D., and Li, J. (2018). Does Foreign Direct Investment Affect Environmental Pollution in China's Cities? A Spatial Econometric Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 613-614, 521–529. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.1110.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.110

Long, F., Liu, J., and Zheng, L. (2022). The Effects of Public Environmental Concern on Urban-Rural Environmental Inequality: Evidence from Chinese Industrial Enterprises. Sustain. Cities Soc. 80, 103787. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2022.103787

Lv, X., Qi, Y., and Dong, W. (2020). Dynamics of Environmental Policy and Firm Innovation: Asymmetric Effects in Canada's Oil and Gas Industries. Sci. Total Environ. 712, 136371. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136371

Pargal, S., and Wheeler, D. (1996). Informal Regulation of Industrial Pollution in Developing Countries: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Political Econ. 104, 1314–1327. doi:10.1086/262061

Pérez-Morote, R., Pontones-Rosa, C., and Núñez-Chicharro, M. (2020). The Effects of E-Government Evaluation, Trust and the Digital Divide in the Levels of E-Government Use in European Countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 154, 119973. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119973

Porter, G. L. (2017). Building a Better Process: Improving Washington State's "Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council" Review Procedures to Better Encourage Public Participation. Wash. J Environ Law Policy 7, 90–114. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wjelp/vol7/iss1/5.

Porter, M. E., and Linde, C. v. d. (1995). Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 9, 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Qiu, W., Bian, Y., Zhang, J., and Irfan, M. (2022). The Role of Environmental Regulation, Industrial Upgrading, and Resource Allocation on Foreign Direct Investment: Evidence from 276 Chinese Cities. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–17. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-18607-2

Quiroga, M., Sterner, T., and Persson, M. (2007). Have Countries with Lax Environmental Regulations a Comparative Advantage in Polluting Industries? Discussion Papers. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24122939_Have_Countries_with_Lax_Environmental_Regulations_a_Comparative_Advantage_in_Polluting_Industries.

Rauf, A., Ozturk, I., Ahmad, F., Shehzad, K., Chandiao, A. A., Irfan, M., Abid, S., and Jinkai, L. (2021). Do Tourism Development, Energy Consumption and Transportation Demolish Sustainable Environments? Evidence from Chinese Provinces. Sustainability 13 (22), 12361. doi:10.3390/su132212361

Shi, R., Irfan, M., Liu, G., Yang, X., and Su, X. (2022). Analysis of the Impact of Livestock Structure on Carbon Emissions of Animal Husbandry: A Sustainable Way to Improving Public Health and Green Environment. Front. Public Health 10, 835210. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.835210

Shi, X., and Xu, Z. (2018). Environmental Regulation and Firm Exports: Evidence from the Eleventh Five-Year Plan in China. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 89, 187–200. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2018.03.003

Shi, X., and Xu, Z. (2018). Environmental Regulation and Firm Exports: Evidence from the Eleventh Five-Year Plan in China. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 89, 187–200. doi:10.1016/j.Jeem.2018.03.003

Shipeng, S., Xin, L., Ansheng, H., and Xiaoxia, S. (2018). Public Participation in Rural Environmental Governance Around the Water Source of Xiqin Water Works in Fujian. J. Resour. Ecol. 9 (1), 66–77. doi:10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2018.01.008

Sun, L., Yung, E. H. K., Chan, E. H. W., and Zhu, D. (2016). Issues of NIMBY Conflict Management from the Perspective of Stakeholders: a Case Study in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 53 (1), 133–141. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.013

Sun, L., Zhu, D., and Chan, E. H. W. (2016). Public Participation Impact on Environment Nimby Conflict and Environmental Conflict Management: Comparative Analysis in Shanghai and Hong Kong. Land Use Policy 58, 208–217. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.07.025

Sun, Y., and Li, Z. (2008). A Nonnested Method for the Choice of Spatial Weights. J Quant Tech Econ 7, 147–159. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3894.2008.07.013

Tang, C., Xue, Y., Wu, H., Irfan, M., and Hao, Y. (2022). How Does Telecommunications Infrastructure Affect Eco-Efficiency? Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment in China. Technol. Soc. 69, 101963. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101963

Tanveer, A., Zeng, S., Irfan, M., and Peng, R. (2021). Do perceived Risk, Perception of Self-Efficacy, and Openness to Technology Matter for Solar PV Adoption? an Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Energies 14 (16), 5008. doi:10.3390/en14165008

Thomas, J. C. (2013). Citizen, Customer, Partner: Rethinking the Place of the Public in Public Management. Public Admin Rev. 73 (6), 786–796. doi:10.1111/puar.12109

Tian, X.-L., Guo, Q.-G., Han, C., and Ahmad, N. (2016). Different Extent of Environmental Information Disclosure across Chinese Cities: Contributing Factors and Correlation with Local Pollution. Glob. Environ. Change 39, 244–257. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.014

Wang, G. (2019). Cross-regional Synergetic Effect of Industrial Structure Change under Environmental Regulation Research Based on Spatial Durbin Model. Res Dev Mark. 35, 889–895. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1005-8141.2019.07.001

Wang, Q., Xie, X., and Wang, M. (2015). Environmental Regulation and Firm Location Choice in China. China Econ. J. 8, 215–234. doi:10.1080/17538963.2015.1102474

Wang, X., Zhang, C., and Zhang, Z. (2019). Pollution Haven or Porter? the Impact of Environmental Regulation on Location Choices of Pollution-Intensive Firms in China. J. Environ. Manag. 248, 109248–248. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.07.019

Wang, Y. (2016). Environmental Pollution and Government Intervention in China. Res Financ Econ Issues 2, 3–11. doi:10.19654/j.cnki.cjwtyj.2016.02.001

Wang, Y. (2015). Research on Environmental Regulation Competition of China Based on Spatial Panel Model. Manag. Rev. 27, 23–32. doi:10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.2015.08.003

Wu, H., Ba, N., Ren, S., Xu, L., Chai, J., Irfan, M., Hao, Y., and Lu, Z.-N. (2021). The Impact of Internet Development on the Health of Chinese Residents: Transmission Mechanisms and Empirical Tests. Socio-Economic Plan. Sci. 81, 101178. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2021.101178

Wu, H., Hao, Y., and Ren, S. (2020). How Do Environmental Regulation and Environmental Decentralization Affect Green Total Factor Energy Efficiency: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 91, 104880. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104880

Wu, J., Xu, M., and Ma, Y. (2016). Environmental Assessment, Public Participation and Governance Effectiveness: Evidence from the Chinese Provinces. Chin. Public Adm. 9, 75–81. doi:10.3782/j.issn.1006-0863.2016.09.14

Xiao, H. (2008). The Cross-Border Relocation of Pollution Intensive Firms under Environmental Regulation and the Governance. Dissertation: Fudan University.

Xiao, H. (2019). The Impact of Different Patterns of Public Participation on Intensity of Environmental Regulation-Aan Analysis Based on Spatial Durbin Model. Coll Essays Finance Econo 1, 100–109. doi:10.13762/j.cnki.cjlc.20181013.009

Xu, Y. (2014). Whether Informal Environmental Regulation from Social Pressure Constraints on China's Industrial Pollution? Finance Trade Res 2, 7–15. doi:10.19337/j.cnki.34-1093/f.2014.02.002

Xue, L., and Dong, X. (2010). Effectiveness Research on Public Participation in Environmental Governance Based on P-S-A Three-Tier Model. China Popu Res Environ 20, 48–54.

Yang, C., Hao, Y., and Irfan, M. (2021). Energy Consumption Structural Adjustment and Carbon Neutrality in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 59, 442–453. doi:10.1016/j.strueco.2021.06.017

Yang, N., Zhang, Z., Xue, B., Ma, J., Chen, X., and Lu, C. (2018). Economic Growth and Pollution Emission in China: Structural Path Analysis. Sustainability 10, 2569. doi:10.3390/su10072569

Yuan, Y., and Xie, R. (2014). Research on the Effect of Environmental Regulation to Industrial Restructuring-Eempirical Test Based on Provincial Panel Data of China. China Ind. Econ. 8, 57–69. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2014.08.005

Zeng, J., Guijarro, M., and Carrilero-Castillo, A. (2020). A Regression Discontinuity Evaluation of the Policy Effects of Environmental Regulations. Econ. Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 33, 2993–3016. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2019.1699437

Zhang, C., and Guo, Y. (2015). China's Fiscal Decentralization, Public Participation and Environmental Regulation: An Empirical Study Based on 30 Provinces from 1997 to 2011 in China, 6. London, United Kindom: J Nanjing Audit University, 13–23.

Zhang, J., Zhang, H., and Gong, X. (2022). Government's Environmental Protection Expenditure in China: The Role of Internet Penetration. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 93, 106706. ISSN 0195-9255. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106706

Zhang, N., Deng, J., Ahmad, F., and Draz, M. U. (2020). Local Government Competition and Regional Green Development in China: the Mediating Role of Environmental Regulation. Ijerph 17, 3485. doi:10.3390/ijerph17103485

Zhang, W., Zhang, L., and Zhang, K. (2010). The Form and Evolution of Provincial Competition of Environmental Regulation Intensity in China--analysis of Durbin Fixed Effect Model Based on Two Zone Space. Manage World 12, 34–44. doi:10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2010.12.005

Zhao, L., and Chen, Y. (2018). Environmental Regulation, Public Participation and Enterprises’ Environmental Behavior-Bbased on Tripartite Evolutionary Game and Empirical Research of Provincial Panel Data. Syst. Eng. 36, 55–65.

Zhao, X. (2014). Inter-local Government Strategies of Environmental Regulation Competition and its Economic Growth Effect. Finance Trade Econ 10, 105–113. doi:10.19795/j.cnki.cn11-1166/f.2014.10.011

Zheng, S., Wan, G., Sun, W., and Luo, D. (2013). Public Demands and Urban Environmental Governance. Manage World 6, 72–84. doi:10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2013.06.006

Zheng, Y., Gao, R., and Li, Y. (2018). The Impact of Informal Environmental Regulation on Inter-regional Transfer Decision of Pollution Enterprises. J. Ind. Tech. Econ. 37, 137–142. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-910X.2018.10.017

Keywords: environmental regulation competition, public participation, enterprise location selection, panel data, COVID-19

Citation: Mu X, Zhan Q, Ameer W, Anser MK, Zeng X and Amin A (2022) Effects of Environmental Regulation Competition and Public Participation on Enterprise Location Selection Under Climate Change in COVID-19 Pandemic Conditions: An Analysis Based on the Chinese Provincial Spatial Panel Model. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:884401. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.884401

Received: 26 February 2022; Accepted: 27 April 2022;

Published: 29 June 2022.

Edited by:

Muhammad Irfan, Beijing Institute of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Luigi Aldieri, University of Salerno, ItalyArifa Tanveer, Beijing University of Technology, China

Copyright © 2022 Mu, Zhan, Ameer, Anser, Zeng and Amin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qilin Zhan, MjAxNjEzNTcxQHNkdGJ1LmVkdS5jbg==; Waqar Ameer, d2FxYXIuYW1lZXJAeWFob28uY29t

Xiuzhen Mu

Xiuzhen Mu Qilin Zhan1*

Qilin Zhan1* Waqar Ameer

Waqar Ameer Azka Amin

Azka Amin