- 1Department of Applied Ecology, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, Russia

- 2School of Environment and Sustainability, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

- 3Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute, Saint-Petersburg, Russia

- 4School of Public Policy and Management, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China

- 5Cryosphere Research Station on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, State Key Laboratory of Cryospheric Science, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou, China

- 6College of Resources and Environment, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

With a unique multi-sphere environmental system, the Tibetan Plateau (TP) plays an essential role in the ecological sheltering function for China and other parts of Asia. However, black carbon, persistent organic pollutants, and heavy metals (HMs) have been increased dramatically since the 1950s, reflecting rising emissions in Asia. In this context, the sources and distribution of HMs were summarized in the environment media of the TP. The results showed that 1) HMs in the TP may be generated from geogenic/pedogenic associations (Cu, Cr, Ni, As, and Co) and anthropogenic activities of local or long-distance atmospheric transmission (Cd, Pb, Zn, and Hg). 2) The atmospheric transport emission sources of HMs are mainly from the surrounding heavily-polluted regions by the Indian and East Asian monsoons and the southern branch of westerly winds. 3) Soil, water, snow, glacier, sediment, and vegetation act as vital sinks of atmospheric deposits of HMs; 4) Significant bioaccumulation of arsenic (As), lead (Pb), and methylmercury (MeHg) have been found in terrestrial and aquatic biota chains in the TP; 5) The enhancement of anthropogenic activities, climate change, glacial retreat and permafrost degradation had potential impacts on the behaviors and fates of HMs in the TP. Therefore, the ecological risk of HMs is of particular concern, and feasible and effective environmental safety strategies are required to reduce the adverse effects of inorganic pollutants in the TP. Our review will provide a reference for researchers to further study regional HMs pollution around the TP.

1 Introduction

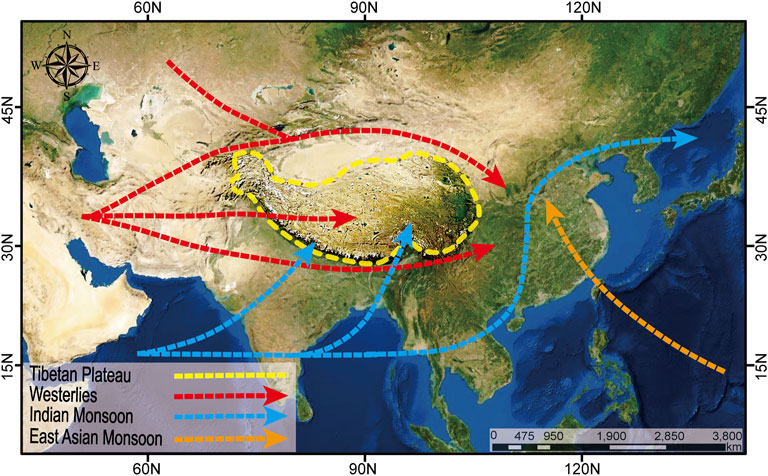

The Tibetan Plateau (TP) is commonly known as the “Third Pole,” the “World Roof,” and the “Asia Water Tower” (Yao et al., 2012; Kang et al., 2019a; Chen et al., 2020). The whole plateau region has few industrial activities, and residents mainly live on grazing sheep and yaks, so the TP is considered one of the most remote and primitive places in the world (Sheng et al., 2012; Kang et al., 2016a; Kang et al., 2016b). However, many studies had shown that the rapid industrializations of South Asia, Southeastern Asia, and East Asia had released heavy metals (HMs) into the atmosphere of the TP in the past few decades (Cong et al., 2007, 2010a, 2014; Kang et al., 2016a; Zhang et al., 2016a). The Himalayas are the highest mountains in the world, which may serve as a natural wall to atmospheric contamination in the southern border area of the TP. However, the high valleys of the Himalayas could act as a channel to transport atmospheric pollutants to the TP (Bonasoni et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2016). Additionally, the contaminants are transported by the Indian and East Asian monsoons in summer and westerlies in winter, affecting remote plateau areas (Yang R. et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2021).

HMs are used to define metals and metalloids associated with potential toxicity and possible pollution (Duffus, 2002; Hodson, 2004). The HMs may release into different environmental media by various ways (Dhaliwal et al., 2020). In addition, HMs are significant anthropogenic contaminants that can be transported for long distances (Ji et al., 2020). Numerous studies have shown that HMs seriously pollute the local environment and transport pollutants to polar and high-altitude regions far away from cities through long-distance transportation (Tripathee et al., 2014; Dong et al., 2015; Jiao et al., 2021). At present, HMs have been found in the Antarctic and Arctic (Planchon et al., 2002; McConnell and Edwards, 2008; Hong et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2013; Abakumov et al., 2017; Casey et al., 2017; Ji et al., 2019; Ji et al., 2021; Alekseev and Abakumov, 2020; Alekseev and Abakumov, 2021). Large HMs have been transported to the Arctic and Antarctic through long-distance atmospheric circulation and deposition (Wilkie and La Farge, 2011).

Similar to the polar regions, the environmental pollution in the TP has been aroused great concern (Qiu, 2014; Wang et al., 2016, Wang X. et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2019a). HMs have been detected in the air, soil, water, snow, and biota (Wu et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020a; Li et al., 2020b; Li M. et al., 2020). Moreover, with climate change, the contaminants released from the degradation of the cryosphere (glaciers, permafrost, ice, and snow) are essential sources of HMs around the TP, which will greatly increase the pollutant accumulation and may have a significant impact on the TP environment.

However, previous studies about HMs in the TP are various and scattered, making it difficult to get a comprehensive understanding of the HMs in the TP. Thus, it is of great significance to study the sources and distribution of HMs around the TP, as well as the regional amplification of HMs and their potential impact in the future. In view of this matter, the objectives of this review are to: 1) summarize current studies concerning the pollution status of HMs in the TP, 2) assess the concentrations, sources, and spatial distribution of HMs in the environmental media of the TP, 3) discuss the effect anthropogenic activities and climate change on the fate of HMs in the TP, and 4) identify research gaps and propose future study needs. This review will be of benefit to quantitatively evaluate the environmental quality of the TP and provide a reference for investigating environmental pollution of the Third Pole.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Review Strategy

We systematically utilized the electronic databases. For instance, Web of Science, Science Direct, Google Scholar, using the following search terms: Tibetan Plateau & heavy metals & pollution. Moreover, search terms, such as Tibet, Himalayas, the third pole, contamination, pollutants, metals, trace metals, trace elements, risk elements, irons, lead, mercury, were applied to find more publications. Scientific journals, official reports, conference proceedings, and news reports were searched in Chinese and English on the Internet. The abovementioned publications included sources, distribution of HMs in various environmental media, the impact of climate change and anthropogenic activities on HMs in the TP according to 140 articles.

2.2 Data Analysis

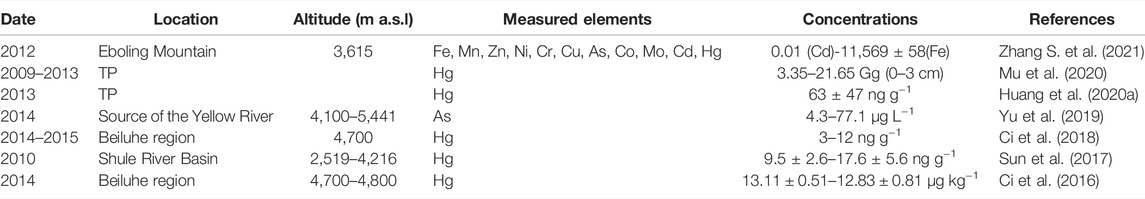

Principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis were carried out to reveal sources of HMs. All collected data sets passed KMO and Barrett test (KMO: 0.819, Barrett significance: 0.000). The factors were rotated by the maximum variance method, indicating no correlation between the extracted dimensions. The cluster analysis was carried out according to the square Euclidean distance using the intergroup connection method.

3 Results

3.1 Sources of Heavy Metals

PCA and cluster analysis were carried out to indicate similarities and familiar sources among HMs. Due to the lack of data for Hg in soil and Co in air, statistics only for Cu, Cr, Ni, As, Cd, Pb, and Zn were carried in various environmental media (air, soil, water, precipitation, ice, sediment, biota) (Figure 1). The loading plot of PCA for sources of HMs was divided into two components. The PCA1 was characterized by Cu, Cr, Ni, and As association, which contributed to the total dispersion (61.90%). Cd, Pb, and Zn association were typical for PCA2, which describes 17.6%. In addition, the cluster analysis was consistent with PCA, implying that Cu, Cr, Ni, and As may be generated from similar sources, and Cd, Pb, and Zn were enriched by another category. The specific possible sources will be further analyzed in the distribution of each environmental media.

FIGURE 1. Principal component analysis (A) and cluster analysis (B) for sources of HMs. Loadings larger than 0.50 are displayed in the principal component analysis.

3.2 Heavy Metals in Air

3.2.1 Outdoor Air

The gaseous contaminants around the TP are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Previous researchers studied HMs in atmospheric aerosols, total suspended particulate (TSP), PM10 and PM2.5. Zhang et al. (2012) assessed the chemical composition of aerosols in the southeastern TP and pointed out that As with a higher enrichment factor may be generated from geogenic/pedogenic associations, and Pb, Cu, and Zn were mainly derived from traffic-related emissions. Huang et al. (2016) collected 80 daily samples of TSP in Lhasa city of Tibet, and the particulate-bound Hg average concentration in the atmosphere was 224 pg m−3, which was far higher than in the Waliguan Mountain (19.4 ± 18.1 pg m−3) and Gongga Mountain (30.7 ± 32.1 pg m−3) (Fu et al., 2008; 2011), indicating that Hg had been accumulated in the atmospheric environment of Lhasa city. The results of PCA of HMs in PM10 showed that dust, traffic emissions and waste incineration were the main sources of HMs in Lhasa city (Cong et al., 2011). Yang et al. (2009) noted that the concentrations of HMs in PM10 and PM2.5 were lower in summer and autumn, which is because HMs were transported to the TP by long-distance atmospheric aerosols caused by sandstorms in Central Asia and contaminants in South Asia during the pre-monsoon (high HMs concentrations in spring) and monsoon seasons (low HMs concentrations in summer) (Cong et al., 2010b; Kang et al., 2016a).

3.2.2 Indoor Air

In the TP, residents burned yak dung, which had a significant impact on the atmosphere, especially in tents (Chen et al., 2015). Li et al. (2012) compared the concentrations of HMs inside and outside tents and revealed the indoor air of the tent was seriously polluted caused by the burning yak dung in residential areas near Nam Co. At the same time, the enrichment factors of the most hazardous elements in indoor and outdoor air were similar, indicating the pollutants released from local tents might affect the outdoor air quality. Kang et al. (2009) reported the indoor air quality of nomadic tents in Nam Co, and pointed out that the average concentrations per day in TSP of Cd (3.16 ng m−3), As (35.00 ng m−3), and Pb (81.39 ng m−3) increased during cooking or heating, which was much higher than MAC from the indoor air quality guidelines (WHO, 2000), indicating that burning yak dung in tents has an impact on the health of Tibetan herdsmen.

Therefore, the aerosol pollutants of the TP are derived from outside and inside (Chen et al., 2015), which were mainly affected by atmospheric transport. Moreover, the burning of local yak dung, fireworks, garbage incineration, traffic, and religious ceremonies cause the increase of HMs concentrations in the air around the TP.

3.3 Heavy Metals in Soil

3.3.1 Soil

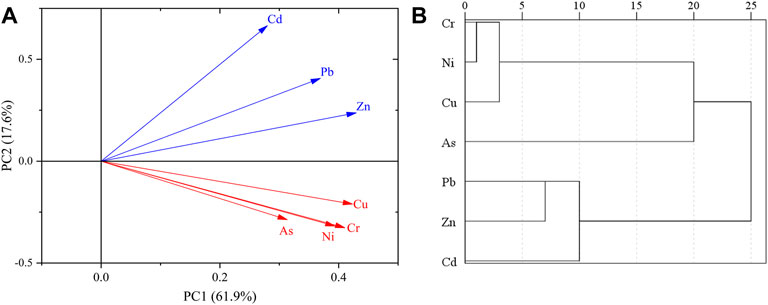

Soil plays a critical role in the environment and serves as a sink of various pollutants. The soil samples in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S2 are polluted with varying degrees in the TP. The concentrations of Ni, Pb, Zn, and Co in the topsoil (0–20 cm) of the TP were slightly higher than the upper continental crust (UCC) (Taylor and Mclennan, 1985), and the background values of As and Cr in Tibetan soil were 13.13 and 2.19 times higher than those in the UCC, respectively (MEPC, 1990). In addition, the concentrations of HMs (Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, Cr, As, Ni, Cd, and Hg) were higher than the background value in the topsoil of Tibet. The concentration of HMs were slightly higher in the northeast, central (Qinghai-Tibet Railway), and southern TP. Besides, the concentrations of HMs in the eastern TP was higher than that of the western TP.

FIGURE 2. HMs concentrations in the topsoil samples (0–20 cm) over the TP (Li et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009; Sheng et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013b; Xie et al., 2014; Zhang H. et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020a; Salim et al., 2020). Notes: The dotted line is HMs background value of soil in Tibet (MEPC, 1990).

Comparing pH, soil types, altitude, and organic carbon, low temperature may also affect the accumulation of HMs in soils. Zhang H. et al. (2015) pointed out the pH of the soil near the Qinghai-Tibet Roadway was higher than 7.52, which reduced the leaching of toxic metals. In addition, Wang et al. (2015) found Cu, Pb, and Zn were concentrated in the alpine frost desert soil, aeolian sandy soil, and peat soil. Bing et al. (2014) and Luo et al. (2015) noted Pb concentrations in different soil horizons was O (Organic surface layer) > A (Surface soil) > C (Substratum). In addition, soil samplings were conducted in 12 plots in the Shule River Basin of northeast TP, and THg concentration showed a downward trend with altitude (Sun et al., 2017). However, the concentrations of HMs at high altitudes showed increasing trends caused by the ubiquity of extremely low temperatures (Salim et al., 2020). Therefore, high altitudes are more prone to high deposition rates of HMs, which seems to be firmly retained in the soil.

In addition, the effect of transportation on HMs in the soil is a research hotspot in the TP (Zhang et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013a; Zhang et al., 2013b; Zhang Y. et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017). The investigation of HMs in the TP was initially based on the analysis of HMs concentration along the Qinghai-Tibet Railway and Roadway. For example, Zn, Cd, and Pb concentrations in the soil at four depths (5, 10, 20, and 30 cm) of the embankment of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway from Delhi to Ulan were more than seven times higher than those in the continental crust (Zhang et al., 2012). The enrichment factor of Cd was higher than that of other elements (Zhang et al., 2012; Zhang Y. et al., 2015). Among them, HMs concentrations in roadside soil and grass increased with the increase of traffic flow (Wang et al., 2013), while the concentration of HMs in roadside soil decreased with the increase of distance from the roadside (Zhang H. et al., 2015). Besides, other factors (including terrain, road surface material, and land cover) had significant effects on HMs concentrations (Wang et al., 2017).

In addition, Wang et al. (2020) surveyed the concentrations of HMs in urban soil of four cities and pointed out that the local urban domestic waste, industry, transportation and other anthropogenic activities contributed 51.83% to the HMs pollution. Besides, the researchers investigated soils in agricultural and pastoral areas, industrial areas, mining areas, salt-lake areas and urban areas in the northeastern TP and found that industrial and mining areas are with the most serious environmental and health risks (Li et al., 2018, 2020a, 2020b; Wu et al., 2018). Therefore, traffic, urban garbage, industry and mining are the anthropogenic sources of local HMs pollution in the soil of the QTP.

3.3.2 Permafrost

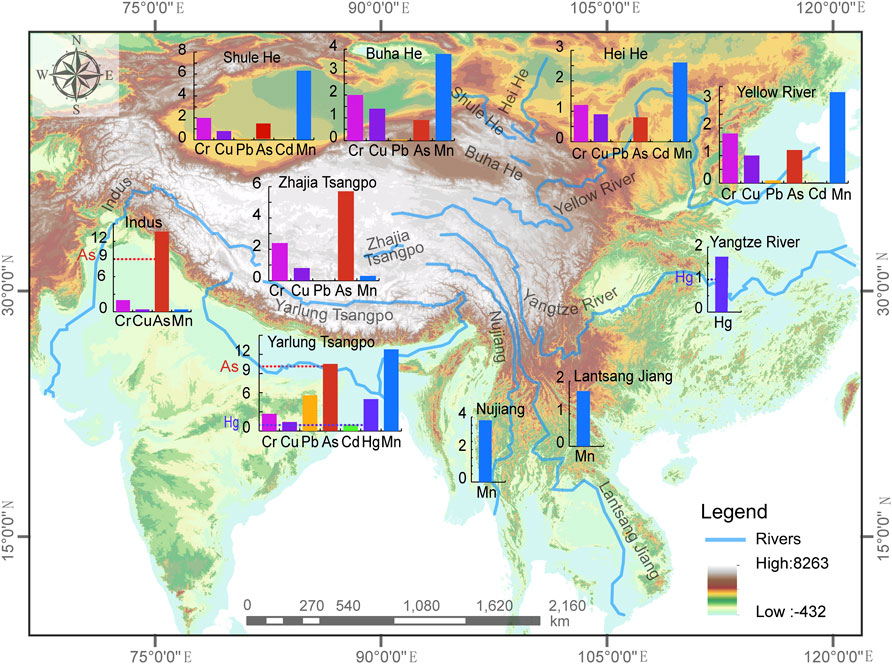

The permafrost range of TP is about 1.06 × 106 km2, which is the largest permafrost region in middle and low latitudes (Jin et al., 2000; Zou et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2020a). The degradation of permafrost (active layer and frozen ground) increases the risk of HMs release (Hg, As, and Cd) to the TP (Yu et al., 2019; Ci et al., 2020; Mu et al., 2020; Zhang S. et al., 2021) (Table 1). For instance, Zhang S. et al. (2021) detected low levels of most HMs except Cd relative to UCC and pointed out that the high concentration of Cd in the Eboling permafrost was caused by anthropogenic activities. Mu et al. (2020) proposed 21.7 Gg of Hg was stored in the permafrost surface layer (0–3 m), indicating that the total Hg mass in the active layer (top 30 cm) of the TP decreased by 17.6%–30.9% on the thermokarst surface.

Thawed Hg was mobile and may be released into the atmosphere as gas or exported to the downstream ecosystems as dissolved liquid in permafrost regions (Ci et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017; Ci et al., 2018; Gu et al., 2020). So, the continuous degradation of permafrost can lead to the migration and release of Hg stored in permafrost regions, which is an essential source of Hg emission in the environment (Ci et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017; Ci et al., 2018; Ci et al., 2020). However, relatively few studies have been conducted on the concentration and mass of HMs in the permafrost, except for Hg. Therefore, further attention should be paid to the mass of various HMs in permafrost, especially the secondary emissions of HMs.

3.4 Heavy Metals in Water

3.4.1 Surface Water

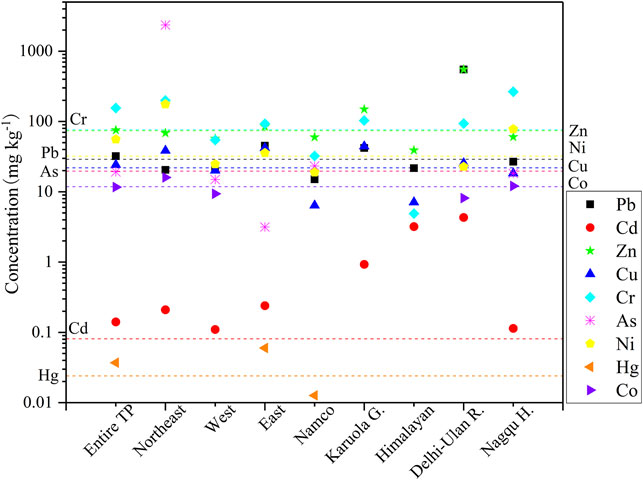

As the Water Tower of Asia, the TP supplies drinking water for about one-sixth of the global population (Immerzeel et al., 2010; Keyimu et al., 2021b). Most of the rivers around the TP were not polluted (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure S1). However, it should be noted that As concentrations in the Indus and the Yarlung Tsangpo rivers were 13.70 and 10.50 μg L−1. Hg were 1.46–4.99 and 1.70 μg L−1 in the Yarlung Tsangpo and Yangtze rivers (Qu et al., 2019), which are higher than the Chinese National Standard for drinking water (MAC of As and Hg are 10 and 1 μg L−1) (MOH and SAC, 2006) and the World Health Organization (MAC of As and Hg are 10 and 6 μg L−1) (WHO, 2011).

FIGURE 3. Spatial distribution of main rivers and HMs concentrations (μg L−1) in the TP (Qu et al., 2019). Notes: The dotted line is the maximum allowable concentration of HMs in the drinking water, element dates are from Chinese national standards for drinking water quality (MOH and SAC, 2006). If HMs concentrations don’t exceed the maximum allowable concentration, no dotted lines are added.

Furthermore, both natural and anthropogenic sources impact the chemical elements in the water ecosystem of the TP. For instance, geological movements, climate change, and land use-coverage change (LUCC) appear to have significant effects on the chemical composition of rivers (Huang et al., 2009); Zhang Y. et al., 2015 collected 43 surface water samples from the Indus River, Ganges Basins, and Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) in 2012, the enrichment factor of As was 30 in the Himalayas, indicating that the river water was seriously affected by anthropogenic activities. Further, Lin et al. (2021) analyzed the chemical composition of water in Lake Bangong Co, and the results of PCA showed that As, Cu, and Cr were mainly from natural resources, while Cd may be caused by anthropogenic activities. Moreover, the dissolved As (Nickson et al., 1998; Zhang J. W et al., 2021) and Hg (Sun et al., 2016) decreased significantly in the downstream of the river due to the adsorption and dilution process of metal elements, indicating that the upstream was affected by anthropogenic activities. Therefore, the surface water of the TP was not polluted except As and Hg.

3.4.2 Groundwater

The TP has active geological activities caused by the interaction of the Eurasian Plate and Indian Ocean plate (Hodges, 2000), which caused high geothermal flows and hydrothermal systems (Guo et al., 2019). Many hot springs on the TP contain high As concentrations, which are harmful to human health (Guo et al., 2019). Furthermore, Zhang J.-W. et al. (2021) observed extremely high concentrations of dissolved As (1,130–9,760 μg L−1) in the hot springs in the upstream of the Yarlung Zangbo River. Therefore, As dissolves into groundwater from rocks and sediments through the coupling of biogeochemical and hydrological processes (Nickson et al., 1998; Fendorf et al., 2010; Wang Y. et al., 2019).

3.5 Heavy Metals in Precipitation

3.5.1 Rain

The accumulation of HMs in alpine and high-altitude regions is related to the precipitation process (Liu et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2012c; Huang et al., 2015). HMs concentration in rainfall around the TP showed that Nancuo Lake and Mount Everest had lower HMs concentrations, and South Asia and urban areas (Lhasa, Kathmandu, and Jomsom) had higher HMs concentration than rural areas (Dhunche) (Supplementary Figure S2) (Cong et al., 2010b; Huang et al., 2013; Tripathee et al., 2014; Tripathee et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2015). Specifically, Cong et al. (2010b) collected 79 precipitation samples at the Nam Co and found the concentrations of Cr, Zn, Co, Ni, Cd, Cu, and Pb in the wetland soil were higher than those of the Tibetan soil, indicating that the Nam Co may be affected by anthropogenic activities. In addition, Cong et al. (2015) analyzed the HMs concentrations of 42 rain samples from Mount Everest (Himalayas), and Cd was the most affected metal by anthropogenic activities. Further, Tripathee et al. (2014), Tripathee et al. (2019), Tripathee et al. (2020) measured the HMs concentrations in Kathmandu and Jomsom of the Nepal Himalayan region and revealed the concentrations of Hg were 0.019 and 0.022 μg L−1 in Kathmandu and Jomsom, which were similar to Lhasa (0.025 μg L−1) (Huang et al., 2013). Moreover, Cong et al. (2015) inferred that the high concentrations of HMs might be the deposition of HMs (aerosols) exposed to the atmosphere for a long time after the precipitation. Therefore, HMs concentrations in rainfall of the TP have apparent seasonal variation, which is high in the pre-monsoon period (spring) and low in the monsoon period (summer), reflecting the outbreak of brown clouds in South Asia and the influence of rainfall removal factors in the rainy season.

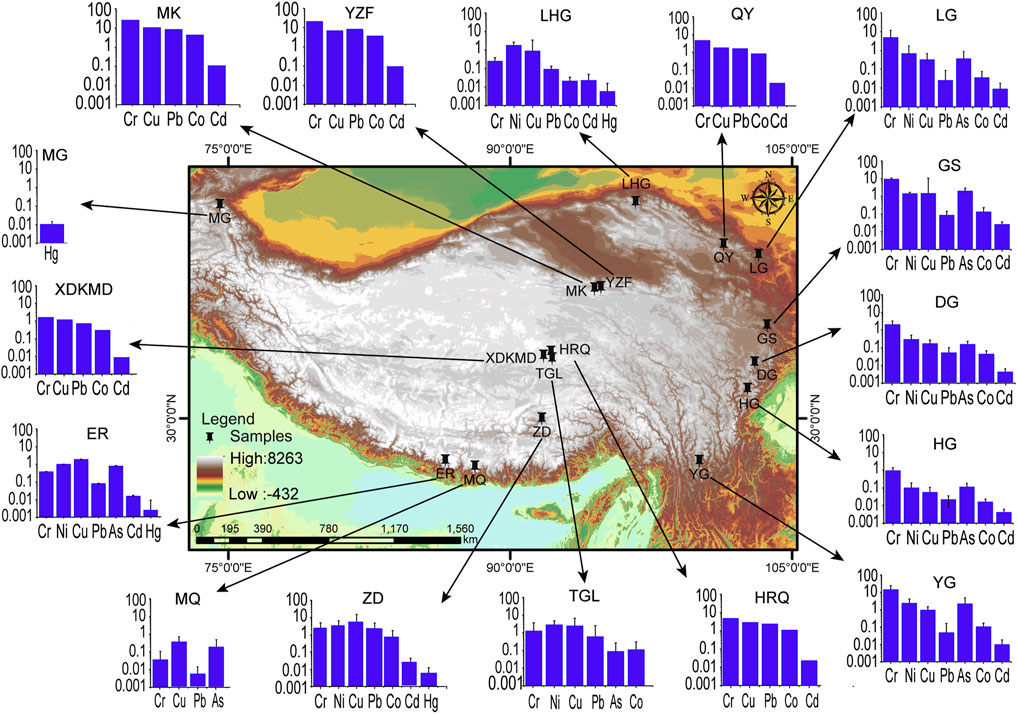

3.5.2 Snow

Snow events remove pollutants from the air to accumulate and agglomerate into the snow (Wang et al., 2016). Numerous studies (Kang et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2012a; Huang et al., 2012b; Huang et al., 2013; Dong et al., 2015; Li Y. et al., 2020; Jiao et al., 2021) analyzed HMs concentrations in glacier snow samples from multiple locations in the TP (Figure 4; Supplementary Figure S3). Glacial snow samples were low concentrations of HMs (Jiao et al., 2021). HMs concentrations ranged from 0.006 μg L−1 (Hg) to 25.680 μg L−1 (Cr) (Figure 6). In addition, concentrations of HMs in snow in the central and southern TP were significantly higher than that in the northern TP, and that in the central TP was higher than that in the eastern TP. Dong et al. (2015) proposed HMs concentrations decreased gradually from the Himalayan region to the Tanggula Basin and Laohugou Basin, indicating that the migration of HMs from South Asia has a significant impact on the central TP. Li et al. (2020) considered dust is the primary source of major HMs in glacial snow. In addition, Jiao et al. (2021) investigated atmospheric deposition and HMs contamination in the glacial snow of the eastern TP and pointed out that two transportation channels of air pollutants: one was from east to west so that HMs concentrations in remote glaciers such as Hailuogou and Dagu far away from the urban areas were much lower, and another was from south to north in the eastern TP. Similarly, the spatial distribution condition of HMs concentrations in the snow was associated with the atmospheric circulation patterns.

FIGURE 4. Spatial distribution of snow samples and HMs concentrations (μg L−1) around the TP (Kang et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2014; Dong et al., 2015; Li Y. et al., 2020; Jiao et al., 2021). Notes: 1) LG, Lenglongling Glacier; DG, Dagu Glacier; HG, Hailuogou Glacier; GS, Gannan Snow; YG, Yulong Snow-mountain Glacier; QY, Qiyi Glacier; MK, Meikuang Glacier; YZF, Yuzhufeng Glacier; HRQ, Hariqin Glacier; XDKMD, Xiaodongkemadi Glacier; LHG, Laohugou Glacier; TGL, Tanggula Glacier; ZD, Zhadang Glacier; ER, East Rongbuk Glacier; MQ, Mt. Qomolangma. 2) Error bars are added if there is a standard deviation, and no error bars are added if there is no standard deviation.

3.6 Heavy Metals in Ice Cores and Sediments

3.6.1 Ice Cores

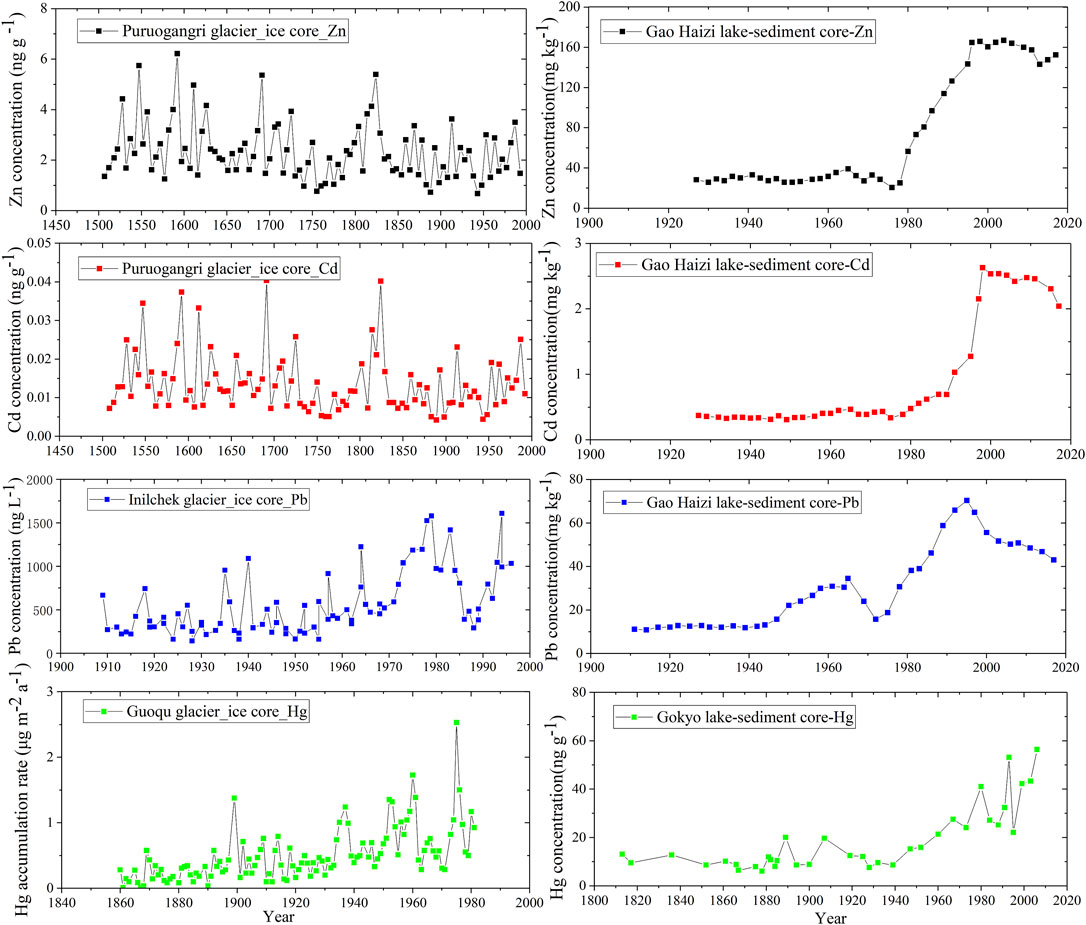

Ice cores drilled from glaciers provided an excellent record of long-term changes in chemical composition, which could be used to estimate the historical accumulation rate of HMs in the TP (Kang et al., 2016b; Kang et al., 2019a; Kang et al., 2019b). Thus, the aforementioned studies reported the historical trends of HMs concentrations in ice cores (Figure 5; Supplementary Table S3). Huo et al. (1999) measured the Pb concentration in the ice core of the Dasuopu Glacier of the TP from 1946 to 1996 and indicated that Pb concentration showed an increasing trend. Hong et al. (2009) collected the upper ice core in the East Rongbuk Glacier of the Qomolangma Mountain, which clearly showed the migration and deposition of As, Sb, Mo, and Sn in the atmosphere prevailing in the high-altitude range of the central Himalayas. Kang et al. (2016b) collected an ice core sample for the sequence of atmospheric Hg deposition in the Himalayas; The deposition rate of Hg was relatively low (1500s∼the early 1800s), increasing during the Industrial Revolution (1860s–1840s), then increasing sharply after the World War II. Therefore, the effects of natural and anthropogenic activities on HMs were found in the ice core of the TP, suggesting that HMs were transmitted to the interior of the TP through the atmosphere.

FIGURE 5. Historical trends of HMs concentrations or accumulation rate in ice core and sediment core from different glaciers and lakes (Bing et al., 2016; Grigholm et al., 2016; Kang, et al., 2016b; Beaudon et al., 2017; Huang, et al., 2020b).

3.6.2 Sediments

The previous studies have shown HMs concentrations in sediments of different rivers and lakes in the TP (Supplementary Table S4): HMs concentrations were lower than low effect range (Long et al., 1995; Ramesh et al., 2000; Dalai et al., 2004; Bing et al., 2016). Thus, chemical concentration had no adverse effects on biota. For instance, Ramesh et al. (2000) pointed out that the physical weathering process seemed to be a chief controlling factor for distributing rare earth elements and HMs in the sediments of the Himalayan rivers. Additionally, they found Ni, Cd, Cu, Cr, and As concentrations of the sediments exceed the low effect range, indicating that HMs may pose a potential biological threat. In the sediments of the Yarlung Tsangpo River and the Mekong River Delta, As had high concentrations owing to weathering of the bedrock (Li et al., 2011). In addition, recent work in the Koshi River Basin of the Himalayas showed that Ni, Cu, Cd, and Pb had low pollution, which derived from both natural and anthropogenic sources caused by atmospheric migration and traffic emissions (Li et al., 2020).

In addition, sediments have been studied to explore the historical process and spatial distribution in the TP (Figure 5). Huang et al. (2020b) analyzed Hg concentration of the sediment at Gaoqiao Lake of the Himalayas and found that the increased Hg accumulation was due to the aggravation of cross-border pollution in South Asia (Kang et al., 2016b). Bing et al. (2016) studied the changes of Pb, Cd, and Zn concentrations in sediments from Gao Haizi Lake, an alpine lake in the eastern TP, and indicated that Zn and Cd fluxes were relatively constant until the 1980s, raised sharply from the 1980s to the 1990s and then maintained stable. However, the Pb flux increased significantly in the 1950s and increased sharply in the 1980s, and peaked in the 1990s and then decreased gradually. Huang et al. (2020b) proposed that the downward trend of Pb accumulation in sediments was due to the Pb decrease in gasoline and the decrease of anthropogenic Pb emissions caused by the phasing out of Pb gasoline (Singh and Singh, 2006). Therefore, the various trends of HMs in the sediment cores reflected the different sources, transport pathways, and geochemical circulation of HMs around the TP.

3.7 Heavy Metals in Biota

3.7.1 Terrestrial Biota

More attention to pollutants in organisms has been paid due to biomagnification and bioconcentration (Wu et al., 2016). Thus, several researchers have studied HMs concentrations of the terrestrial biota (Supplementary Table S5). For instance, mosses and lichens have been widely used for biomonitoring of trace metals in the atmosphere (Shao et al., 2016; Fabri et al., 2018). Bing et al. (2014) analyzed the Pb of moss and revealed that its concentration ranged from 20.0 to 62.1 mg kg−1 in the Hailuogou Glacier Foreland, eastern TP, suggesting that the contribution of the anthropogenic Pb to the mosses was 41.6%–65.9%. Shao et al. (2017) collected moss and lichen, and THg concentration was 13.1–273.0 and 20.2–345.9 ng g−1, respectively. Moreover, Shao et al. (2017), Shao et al. (2015) pointed out that the concentration of HMs in mosses increased with the elevation, and the spatial distribution of most HMs decreased from west to east and from south to north in the TP.

In addition, HMs concentrations varied with species and organs of vegetations (Nabulo et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2016b). Jia et al. (2021) measured and analyzed Pb and Cd concentrations in needles and twigs of fir and spruce collected from 26 sites in the eastern TP, indicating concentrations of Pb and Cd in twigs were higher than those in needles. Furthermore, most HMs are still at the root (Eid et al., 2012; Bonanno, 2013), fine roots were able to adsorb Pb in the soil humus horizon (Luo et al., 2015; Jia et al., 2021). In addition, leaves absorbed and accumulated HMs particles directly from the atmosphere (Grigholm et al., 2016). Cd, Mn, Fe, and Zn fell to the surface of leaves and return to the soil through the litter. Sun et al. (2020) measured the gaseous Hg fluxes of alpine meadows in the central TP during the whole vegetation period, suggesting that the alpine steppe hindered the emission of Hg and provided a sink for total gaseous Hg. Therefore, vegetation provides a sink for HMs accumulation.

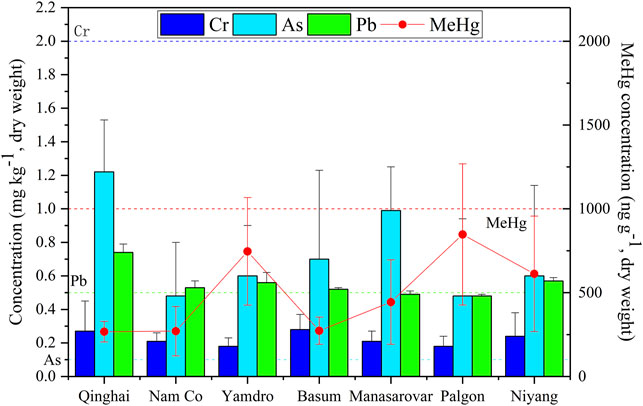

3.7.2 Aquatic Biota

HMs concentrations in fish were still of great significance for understanding its impact on aquatic ecosystems in the TP (Xiong et al., 2020). As, methylmercury (MeHg), and Pb were observed in wild fish in many lakes and rivers of the TP (Figure 6; Supplementary Table S6). As and Pb concentrations of wild fish far exceeded the MAC (0.1 and 0.5 mg kg−1) of Chinese Food Health Standard (MOH and SAC, 2017), and Pb concentrations of all lakes and rivers were similar. Hg is easily converted to MeHg, a neurotoxin that bioaccumulate in humans and wildlife (Gilmour et al., 1992; Sun et al., 2021). The average concentration of MeHg in most Tibetan fish was less than the MAC, but the recent survey of wild fish in Niyang River and Lhasa River found that the dry weights of MeHg concentrations were 276–1,158 ng g−1, 281–1,331 ng g−1, exceeding MAC (Shao et al., 2015). Overall, high MeHg concentration in wild fish might be related to low temperature, poor nutrition in the water environment, and slow growth of fish (Zhang Q. et al., 2014; Shao et al., 2015). Therefore, attention should be paid to the high concentrations of As, MeHg and Pb in wild fish in the TP.

FIGURE 6. Distribution of different lakes and rivers about HMs concentrations of wild fishes in the TP (Yang et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2011; Yang K. et al., 2014; Shao et al., 2015). Notes: The dotted line is the maximum allowable concentration of HMs in the wild fishes, element data are from Chinese food health criterion (MOH and SAC, 2017).

4 Discussion

4.1 Sources of Heavy Metals

The results of PCA and cluster analysis indicated that Cu, Cr, Ni, and As may be generated from similar sources, and Cd, Pb, and Zn are enriched by another category. Sheng et al. (2012) pointed out that weathering products of the basic bedrocks might be the chief origins of most HMs in Tibetan soils. For instance, As-enriched rocks, such as shales, are widely distributed in the QTP (Li et al., 2011). Besides, previous studies pointed out that Tibetan soils developed from ultramafic rocks are usually enriched in Ni, Co, and others (Yin and Harrison, 2003). In addition, researchers revealed transportation (Zhang H et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017), mining and smelting (Bing et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2019) are the primary anthropogenic sources of elevated Cd, Pb, Zn, and Hg in the TP. Meanwhile, previous reports have demonstrated that Hg accumulation in soils is determined by the formation of organic complex and dissolution processes after precipitation (Huang et al., 2012c; Tripathee et al., 2019; Tripathee et al., 2020), so atmospheric transport and deposition may be the sources of Hg deposited in topsoil. Therefore, HMs may be derived from geogenic/pedogenic associations (Cu, Cr, Ni, As, and Co) and anthropogenic emissions (Cd, Pb, Zn, and Hg) of local or long-distance atmospheric transmission.

4.2 Atmospheric Transport of Heavy Metals

Although the Himalayas in the southern TP hinder atmospheric transport, the transport of pollutants cannot be completely blocked (Wang et al., 2016). For instance, mountain peak-valley wind patterns might promote the trans-Himalayan transportation of contamination (Cong et al., 2015; Lüthi et al., 2015). Additionally, the atmospheric circulation pattern is dominated by the Indian summer monsoons from May to September and the westerlies from October to April in the TP (Figure 7). Atmospheric circulation patterns affect remote plateau regions. For instance, Cong et al. (2007) pointed out that South Asia may be the source region of HMs contaminants in TSP of Nam Co. In addition, Zhang N. et al. (2014) evaluated HMs in TSP and PM2.5 samples of Qinghai Lake and proposed that Pb and Zn were affected by the wind migration in eastern China. Therefore, the Indian and East Asian monsoons during the monsoon period and southern branch of westerly winds may have a significant impact on the long-distance cross-border migration of HMs in southwestern China, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.

FIGURE 7. The monsoons of TP (Yang K. et al., 2014).

4.3 Local Anthropogenic Heavy Metals Sources

In recent decades, the social economy of the TP has been accelerated, especially the remarkable growth of the transportation industry. Transportation brings many benefits, but it is one of the most essential sources of HMs around the TP (Zhang Y. et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2019). In addition, biomass combustion (yak dung) is a local source of HMs for the TP. The yak dung combustion releases aerosols rich in HMs into the atmosphere (Chen et al., 2015; Ye et al., 2020). Besides, urban living garbage (Wang et al., 2020) and religious rituals (Duo et al., 2015; Cui et al., 2018) may be the main sources of anthropogenic HMs in the TP. Therefore, anthropogenic activities are one of the criminal sources of HMs around the TP.

4.4 Impact of Climate Change on Heavy Metals Emissions

The TP is a vital cryosphere in the middle and low altitude regions (Qiu, 2008; Yao et al., 2012), which has experienced tremendous climate change (Kang et al., 2010; You et al., 2016; Keyimu et al., 2021a). Since 1960, the average temperature has increased by 0.36°C per decade (Wang et al., 2008). In addition, 82% of plateau glaciers have degraded over the past half-century (Qiu, 2008), snow cover has decreased by 5.7%, and 10% of permafrost has degraded from 1997 to 2012 in the TP (Qiu, 2012; Qiu, 2014). Therefore, changes in the cryosphere around the TP affect the geophysical, biological and geochemical interactions of environmental pollutants.

The cryosphere is a temporary repository of pollutants (Kang et al., 2019a). However, with global change, pollutants stored in the cryosphere would be released into the different environmental media (Potapowicz et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020). Zhu et al. (2020) analyzed the historical trend of contaminants in lake sediments of the southern TP and concluded that the rate of contaminants released by glacial meltwater is 40%–61%, corresponding to the warmer climate. In addition, permafrost contains more extensive chemical storage, and its degradation accelerated the emission of HMs (Yu et al., 2019; Ci et al., 2020; Mu et al., 2020; Zhang S. et al., 2021). Therefore, climate change causes the cryosphere to melt, releasing HMs, which may increase the accumulation of pollutants and affect the global environment in the future.

4.5 Limitations and Outlooks

The following limitations are put forward to study HMs around the TP: 1) Similar to the Arctic and Antarctica, the TP is also a core region for studying climate change and pollution. For instance, anthropogenic activities cause long-distance transport of pollutants to sink in glaciers and permafrost range; climate warming may promote the secondary release of pollutants from glaciers and permafrost to the atmosphere, discharge with meltwater, and other processes. 2) In terms of pollution source analysis, many studies are carried out by the occurrence frequency of reverse air mass trajectories. Despite providing a potential source, its identification accuracy needs to be improved, especially in the quantitative assessment of transmission flux. Experiments using multiple means such as particle lidar, satellite remote sensing, and isotope tracer methods are needed to combine ground monitoring data with big data models to quantify sources and characteristics of pollutants in TP. 3) In the lakes and rivers of the TP, wild fish with high concentrations of As, Hg, and Pb were found. However, so far, no data have been reported on HMs in the terrestrial food chain, and the impact of HMs on other organisms and humans is still lacking in the TP. 4) Soil, water, snow, glacier, sediment, and biota are essential sinks of atmospheric HMs. However, the specific relationship between HMs in different environmental media is still unclear.

In the future, the following points should be focused on: 1) It is necessary to study the accumulation, distribution, and transformation of HMs and other pollutants in glacial and permafrost degradation regions around the TP. 2) Using particle lidar, satellite remote sensing, isotope tracing, and other means to conduct experiments, and combining ground monitoring data with big data models to quantify the sources and characteristics of pollutants in the TP. 3) The relationship between bioaccumulation of HMs and human health needs to be further studied in the TP. 4) Conducting a coordinated sampling and measurement of various environmental media samples to quantify the pollution status of the TP comprehensively.

5 Conclusion

The inorganic pollution in different environmental media was summarized around the TP. The results showed that 1) HMs in the TP may be generated from geogenic/pedogenic associations (Cu, Cr, Ni, As, and Co) and anthropogenic activities of local or long-distance atmospheric transmission (Cd, Pb, Zn, and Hg). 2) The atmospheric transport emission sources of HMs are mainly from the surrounding heavily-polluted regions by the Indian and East Asian monsoons during the monsoon period and southern branch of westerly winds. 3) Soil, water, glacier, and vegetation are critical reservoirs of HMs. 4) Significant bioaccumulation of As, Pb, and MeHg has been found in terrestrial and aquatic biota chains. 5) The enhancement of anthropogenic activities, climate change, glacial retreat and permafrost degradation had potential effects on the behaviors, fates, and distribution of HMs around the TP. Therefore, we hope that the ecological risks of the TP should be of increasing concern and systematically studied, calling for effective ecological safety strategies to reduce the adverse effects of environmental pollutants in the TP.

Author Contributions

WW conducted data curation and wrote the original draft; XJ and EA contributed to conceptualization; EA acquired funding; VP and DW assisted with formal analysis; GL helped with software and contributed to visualization; and WW, XJ, EA, VP, GL, and DW reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the China Scholarship Council (201907010003) and Russian Foundation for Basic Research (19-05-50107).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shurong Zhou and Dr. Yao Xiao who provided the opportunity to investigate the Tibetan Plateau.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.874635/full#supplementary-material

References

Abakumov, E., Shamilishviliy, G., and Yurtaev, A. (2017). Soil Polychemical Contamination on Beliy Island as Key Background and Reference Plot for Yamal Region. Polish Polar Res. 38, 313–332. doi:10.1515/popore-2017-0020

Alekseev, I., and Abakumov, E. (2021). Content of Trace Elements in Soils of Eastern Antarctica: Variability Across Landscapes. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 80, 368–388. doi:10.1007/s00244-021-00808-4

Alekseev, I., and Abakumov, E. (2020). The Content and Distribution of Trace Elements and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Soils of Maritime Antarctica. Environ. Monit. Assess. 192. doi:10.1007/s10661-020-08618-2

Beaudon, E., Gabrielli, P., Sierra-Hernández, M. R., Wegner, A., and Thompson, L. G. (2017). Central Tibetan Plateau Atmospheric Trace Metals Contamination: A 500-Year Record from the Puruogangri Ice Core. Sci. Total Environ. 601–602, 1349–1363. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.195

Bing, H., Wu, Y., Zhou, J., Li, R., and Wang, J. (2016). Historical Trends of Anthropogenic Metals in Eastern Tibetan Plateau as Reconstructed from alpine lake Sediments over the Last century. Chemosphere 148, 211–219. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.01.042

Bing, H., Wu, Y., Zhou, J., Ming, L., Sun, S., and Li, X. (2014). Atmospheric Deposition of lead in Remote High Mountain of Eastern Tibetan Plateau, China. Atmos. Environ. 99, 425–435. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.10.014

Bonanno, G. (2013). Comparative Performance of Trace Element Bioaccumulation and Biomonitoring in the Plant Species Typha Domingensis, Phragmites Australis and Arundo donax. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 97, 124–130. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.07.017

Bonasoni, P., Laj, P., Marinoni, A., Sprenger, M., Angelini, F., Arduini, J., et al. (2010). Atmospheric Brown Clouds in the Himalayas: First Two Years of Continuous Observations at the Nepal Climate Observatory-Pyramid (5079 m). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 7515–7531. doi:10.5194/acp-10-7515-2010

Casey, K. A., Kaspari, S. D., Skiles, S. M., Kreutz, K., and Handley, M. J. (2017). The Spectral and Chemical Measurement of Pollutants on Snow Near South Pole, Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 6592–6610. doi:10.1002/2016JD026418

Chen, P., Kang, S., Bai, J., Sillanpää, M., and Li, C. (2015). Yak Dung Combustion Aerosols in the Tibetan Plateau: Chemical Characteristics and Influence on the Local Atmospheric Environment. Atmos. Res. 156, 58–66. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2015.01.001

Chen, P., Zhang, J., Liu, J., Cao, X., Hou, J., Zhu, L., et al. (2020). Climate Change, Vegetation History, and Landscape Responses on the Tibetan Plateau During the Holocene: A Comprehensive Review. Quat. Sci. Rev. 243, 106444. doi:10.1016/J.QUASCIREV.2020.106444

Ci, Z., Peng, F., Xue, X., and Zhang, X. (2016). Air-Surface Exchange of Gaseous Mercury over Permafrost Soil: An Investigation at a High-Altitude (4700 m a.s.l.) and Remote Site in the central Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 16 14741–14754. doi:10.5194/acp-2016-515

Ci, Z., Peng, F., Xue, X., and Zhang, X. (2020). Permafrost Thaw Dominates Mercury Emission in Tibetan Thermokarst Ponds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 5456–5466. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b06712

Ci, Z., Peng, F., Xue, X., and Zhang, X. (2018). Temperature Sensitivity of Gaseous Elemental Mercury in the Active Layer of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Permafrost. Environ. Pollut. 238, 508–515. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.02.085

Cong, Z., Kang, S., Dong, S., Liu, X., and Qin, D. (2010a). Elemental and Individual Particle Analysis of Atmospheric Aerosols from High Himalayas. Environ. Monit. Assess. 160, 323–335. doi:10.1007/s10661-008-0698-3

Cong, Z., Kang, S., Kawamura, K., Liu, B., Wan, X., Wang, Z., et al. (2014). Carbonaceous Aerosols on the South Edge of the Tibetan Plateau: Concentrations, Seasonality and Sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 1573–1584. doi:10.5194/acp-15-1573-2015

Cong, Z., Kang, S., Liu, X., and Wang, G. (2007). Elemental Composition of Aerosol in the Nam Co Region, Tibetan Plateau, during Summer Monsoon Season. Atmos. Environ. 41, 1180–1187. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.09.046

Cong, Z., Kang, S., Luo, C., Li, Q., Huang, J., Gao, S., et al. (2011). Trace Elements and Lead Isotopic Composition of PM10 in Lhasa, Tibet. Atmos. Environ. 45, 6210–6215. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.07.060

Cong, Z., Kang, S., Zhang, Y., Gao, S., Wang, Z., Liu, B., et al. (2015). New Insights Into Trace Element Wet Deposition in the Himalayas: Amounts, Seasonal Patterns, and Implications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 2735–2744. doi:10.1007/s11356-014-3496-1

Cong, Z., Kang, S., Zhang, Y., and Li, X. (2010b). Atmospheric Wet Deposition of Trace Elements to Central Tibetan Plateau. Appl. Geochem. 25, 1415–1421. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2010.06.011

Cui, Y. Y., Liu, S., Bai, Z., Bian, J., Li, D., Fan, K., et al. (2018). Religious Burning as a Potential Major Source of Atmospheric fine Aerosols in Summertime Lhasa on the Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Environ. 181, 186–191. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.03.025

Dalai, T. K., Rengarajan, R., and Patel, P. P. (2004). Sediment Geochemistry of the Yamuna River System in the Himalaya: Implications to Weathering and Transport. Geochem. J. 38, 441–453. doi:10.2343/geochemj.38.441

Dhaliwal, S. S., Singh, J., Taneja, P. K., and Mandal, A. (2020). Remediation Techniques for Removal of Heavy Metals from the Soil Contaminated through Different Sources: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 1319–1333. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-06967-1

Dong, Z., Kang, S., Qin, X., Li, X., Qin, D., and Ren, J. (2015). New Insights into Trace Elements Deposition in the Snow Packs at Remote alpine Glaciers in the Northern Tibetan Plateau, China. Sci. Total Environ. 529, 101–113. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.065

Duffus, J. H. (2002). “Heavy Metals” a Meaningless Term? (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 74, 793–807. doi:10.1351/pac200274050793

Duo, B., Zhang, Y., Kong, L., Fu, H., Hu, Y., Chen, J., et al. (2015). Individual Particle Analysis of Aerosols Collected at Lhasa City in the Tibetan Plateau. J. Environ. Sci. 29, 165–177. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2014.07.032

Eid, E. M., Shaltout, K. H., El-Sheikh, M. A., and Asaeda, T. (2012). Seasonal Courses of Nutrients and Heavy Metals in Water, Sediment and above- and Below-Ground Typha Domingensis Biomass in Lake Burullus (Egypt): Perspectives for Phytoremediation. Flora Morphol. Distribut. Funct. Ecol. Plants 207, 783–794. doi:10.1016/j.flora.2012.09.003

Fabri-Jr, R., Krause, M., Dalfior, B. M., Salles, R. C., de Freitas, A. C., da Silva, H. E., et al. (2018). Trace Elements in Soil, Lichens, and Mosses from Fildes Peninsula, Antarctica: Spatial Distribution and Possible Origins. Environ. Earth Sci. 77. doi:10.1007/s12665-018-7298-5

Fendorf, S., Michael, H. A., and Van Geen, A. (2010). Spatial and Temporal Variations of Groundwater Arsenic in South and Southeast Asia. Science 328, 1123–1127. doi:10.1126/science.1172974

Fu, X., Feng, X., Zhu, W., Zheng, W., Wang, S., and Lu, J. Y. (2008). Total Particulate and Reactive Gaseous Mercury in Ambient Air on the Eastern Slope of the Mt. Gongga Area, China. Appl. Geochem. 23, 408–418. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2007.12.018

Fu, X., Feng, X., and Liang, P. (2011). Temporal Trend and Sources of Speciated Atmospheric Mercury at Waliguan GAW station, Northwestern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 11, 30053–30089. doi:10.5194/acpd-11-30053-2011

Gilmour, C. C., Henry, E. A., and Mitchell, R. (1992). Sulfate Stimulation of Mercury Methylation in Freshwater Sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 26, 2281–2287. doi:10.1021/es00035a029

Grigholm, B., Mayewski, P. A., Aizen, V., Kreutz, K., Wake, C. P., Aizen, E., et al. (2016). Mid-twentieth century Increases in Anthropogenic Pb, Cd and Cu in central Asia Set in Hemispheric Perspective Using Tien Shan Ice Core. Atmos. Environ. 131, 17–28. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.01.030

Gu, J., Pang, Q., Ding, J., Yin, R., Yang, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2020). The Driving Factors of Mercury Storage in the Tibetan Grassland Soils Underlain by Permafrost. Environ. Pollut. 265, 115079. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115079

Guo, J., Kang, S., Huang, J., Zhang, Q., Tripathee, L., and Sillanpää, M. (2015). Seasonal Variations of Trace Elements in Precipitation at the Largest City in Tibet, Lhasa. Atmos. Res. 153, 87–97. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2014.07.030

Guo, Q., Planer-Friedrich, B., Liu, M., Yan, K., and Wu, G. (2019). Magmatic Fluid Input Explaining the Geochemical Anomaly of Very High Arsenic in Some Southern Tibetan Geothermal Waters. Chem. Geol. 513, 32–43. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.03.008

Hodges, K. V. (2000). Tectonics of the Himalaya and Southern Tibet from Two Perspectives. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull., 112. 3242–3350. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(2000)112<324:tothas>2.0.co;2

Hodson, M. E. (2004). Heavy Metals-Geochemical Bogey Men? Environ. Pollut. 129, 341–343. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2003.11.003

Hong, S., Lee, K., Hou, S., Hur, S. D., Ren, J., Burn, L. J., et al. (2009). An 800-year Record of Atmospheric as, Mo, Sn, and Sb in central Asia in High-Altitude Ice Cores from Mt. Qomolangma (Everest), Himalayas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 8060–8065. doi:10.1021/es901685u

Hong, S., Soyol-Erdene, T.-O., Hwang, H. J., Hong, S. B., Hur, S. D., and Motoyama, H. (2012). Evidence of Global-Scale as, Mo, Sb, and Tl Atmospheric Pollution in the Antarctic Snow. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 11550–11557. doi:10.1021/es303086c

Huang, J., Kang, S., Guo, J., Sillanpää, M., Zhang, Q., Qin, X., et al. (2014). Mercury Distribution and Variation on a High-Elevation Mountain Glacier on the Northern Boundary of the Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Environ. 96, 27–36. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.07.023

Huang, J., Kang, S., Guo, J., Zhang, Q., Cong, Z., Sillanpää, M., et al. (2016). Atmospheric Particulate Mercury in Lhasa City, Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Environ. 142, 433–441. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.08.021

Huang, J., Kang, S., Guo, J., Zhang, Q., Xu, J., Jenkins, M. G., et al. (2012a). Seasonal Variations, Speciation and Possible Sources of Mercury in the Snowpack of Zhadang Glacier, Mt. Nyainqêntanglha, Southern Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 429, 223–230. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.04.045

Huang, J., Kang, S., Wang, S., Wang, L., Zhang, Q., Guo, J., et al. (2013). Wet Deposition of Mercury at Lhasa, the Capital City of Tibet. Sci. Total Environ. 447, 123–132. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.01.003

Huang, J., Kang, S., Yin, R., Guo, J., Lepak, R., Mika, S., et al. (2020a). Mercury Isotopes in Frozen Soils Reveal Transboundary Atmospheric Mercury Deposition over the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Pollut. 256, 113432. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113432

Huang, J., Kang, S., Yin, R., Lin, M., Guo, J., Ram, K., et al. (2020b). Decoupling Natural and Anthropogenic Mercury and Lead Transport from South Asia to the Himalayas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 5429–5436. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c00429

Huang, J., Kang, S., Zhang, Q., Guo, J., Sillanpää, M., Wang, Y., et al. (2015). Characterizations of Wet Mercury Deposition on a Remote High-Elevation Site in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Pollut. 206, 518–526. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2015.07.024

Huang, J., Kang, S., Zhang, Q., Jenkins, M. G., Guo, J., Zhang, G., et al. (2012b). Spatial Distribution and Magnification Processes of Mercury in Snow from High-Elevation Glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Environ. 46, 140–146. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.10.008

Huang, J., Kang, S., Zhang, Q., Yan, H., Guo, J., Jenkins, M. G., et al. (2012c). Wet Deposition of Mercury at a Remote Site in the Tibetan Plateau: Concentrations, Speciation, and Fluxes. Atmos. Environ. 62, 540–550. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.09.003

Huang, X., Sillanpää, M., Gjessing, E. T., and Vogt, R. D. (2009). Water Quality in the Tibetan Plateau: Major Ions and Trace Elements in the Headwaters of Four Major Asian Rivers. Sci. Total Environ. 407, 6242–6254. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.09.001

Huo, W., Yao, T., and Li, Y. (1999). Increasing Atmospheric Pollution Revealed by Pb Record of a 7 000-m Ice Core. Chin.Sci.Bull. 44, 1309–1312. doi:10.1007/bf02885851

Immerzeel, W. W., Van Beek, L. P. H., and Bierkens, M. F. P. (2010). Climate Change Will Affect the Asian Water Towers. Science 328, 1382–1385. doi:10.1126/science.1183188

Ji, X., Abakumov, E., Chigray, S., Saparova, S., Polyakov, V., Wang, W., et al. (2021). Response of Carbon and Microbial Properties to Risk Elements Pollution in Arctic Soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 408, 124430. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124430

Ji, X., Abakumov, E., Tomashunas, V., Polyakov, V., and Kouzov, S. (2020). Geochemical Pollution of Trace Metals in Permafrost-Affected Soil in the Russian Arctic Marginal Environment. Environ. Geochem. Health 42, 4407–4429. doi:10.1007/s10653-020-00587-2

Ji, X., Abakumov, E., and Xie, X. (2019). Atmosphere-Ocean Exchange of Heavy Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Russian Arctic Ocean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 13789–13807. doi:10.5194/acp-19-13789-2019

Jia, L., Luo, J., Peng, P., Li, W., Yang, D., Shi, W., et al. (2021). Distribution Trends of Cadmium and lead in Timberline Coniferous Forests in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau. Appl. Sci. 11, 753–810. doi:10.3390/app11020753

Jiao, X., Dong, Z., Kang, S., Li, Y., Jiang, C., and Rostami, M. (2021). New Insights into Heavy Metal Elements Deposition in the Snowpacks of Mountain Glaciers in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 207, 111228. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111228

Jin, H., Li, S., Cheng, G., Shaoling, W., and Li, X. (2000). Permafrost and Climatic Change in China. Glob. Planet. Change 26, 387–404. doi:10.1016/S0921-8181(00)00051-5

Kang, S., Chen, P., Li, C., Liu, B., and Cong, Z. (2016a). Atmospheric Aerosol Elements over the Inland Tibetan Plateau: Concentration, Seasonality, and Transport. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 16, 789–800. doi:10.4209/aaqr.2015.05.0307

Kang, S., Huang, J., Wang, F., Zhang, Q., Zhang, Y., Li, C., et al. (2016b). Atmospheric Mercury Depositional Chronology Reconstructed from Lake Sediments and Ice Core in the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 2859–2869. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b04172

Kang, S., Li, C., Wang, F., Zhang, Q., and Cong, Z. (2009). Total Suspended Particulate Matter and Toxic Elements Indoors during Cooking with Yak Dung. Atmos. Environ. 43, 4243–4246. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.06.015

Kang, S., Xu, Y., You, Q., Flügel, W.-A., Pepin, N., and Yao, T. (2010). Review of Climate and Cryospheric Change in the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 015101. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/5/1/015101

Kang, S., Zhang, Q., Kaspari, S., Qin, D., Cong, Z., Ren, J., et al. (2007). Spatial and Seasonal Variations of Elemental Composition in Mt. Everest (Qomolangma) Snow/firn. Atmos. Environ. 41, 7208–7218. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.05.024

Kang, S., Zhang, Q., Qian, Y., Ji, Z., Li, C., Cong, Z., et al. (2019a). Linking Atmospheric Pollution to Cryospheric Change in the Third Pole Region: Current Progress and Future Prospects. Natl. Sci. Rev. 6, 796–809. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwz031

Keyimu, M., Li, Z., Fu, B., Liu, G., Zeng, F., Chen, W., et al. (2021a). A 406-Year Non-Growing-Season Precipitation Rreconstruction in the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Past 17, 2381–2392. doi:10.5194/CP-17-2381-2021

Keyimu, M., Li, Z., Liu, G., Fu, B., Fan, Z., Wang, X., et al. (2021b). Tree-Ring Based Minimum Temperature Reconstruction on the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Quat. Sci. Rev. 251, 106712. doi:10.1016/J.QUASCIREV.2020.106712

Kang, S., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Q., Wang, X., Dong, Z., Li, C., et al. (2020b). “Chemical Components and Distributions in Glaciers of the Third Pole,” in Water Quality in the Third Pole: The Roles of Climate Change and Human Activities (Elsevier), 71–134. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-816489-1.00003-7

Lee, K., Hur, S. D., Hou, S., Hong, S., Qin, X., Ren, J., et al. (2008). Atmospheric Pollution for Trace Elements in the Remote High-Altitude Atmosphere in central Asia as Recorded in Snow from Mt. Qomolangma (Everest) of the Himalayas. Sci. Total Environ. 404, 171–181. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.06.022

Li, C., Kang, S., Chen, P., Zhang, Q., and Fang, G. C. (2012). Characterizations of Particle-Bound Trace Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) within Tibetan Tents of South Tibetan Plateau, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 19, 1620–1628. doi:10.1007/s11356-011-0678-y

Li, C., Kang, S., and Zhang, Q. (2009). Elemental Composition of Tibetan Plateau Top Soils and its Effect on Evaluating Atmospheric Pollution Transport. Environ. Pollut. 157, 2261–2265. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2009.03.035

Li, C., Kang, S., Zhang, Q., Gao, S., and Sharma, C. M. (2011). Heavy Metals in Sediments of the Yarlung Tsangbo and its Connection with the Arsenic Problem in the Ganges-Brahmaputra Basin. Environ. Geochem. Health 33, 23–32. doi:10.1007/s10653-010-9311-0

Li, L., Wu, J., Lu, J., Min, X., Xu, J., and Yang, L. (2018). Distribution, Pollution, Bioaccumulation, and Ecological Risks of Trace Elements in Soils of the Northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 166, 345–353. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.09.110

Li, L., Wu, J., Lu, J., and Xu, J. (2020a). Speciation, Risks and Isotope-Based Source Apportionment of Trace Elements in Soils of the Northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geochem. Explor. Environ. Anal. 20, 315–322. doi:10.1144/geochem2019-042

Li, L., Wu, J., Lu, J., and Xu, J. (2020b). Trace Elements in Gobi Soils of the Northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Chem. Ecol. 36, 967–981. doi:10.1080/02757540.2020.1817403

Li, M., Zhang, Q., Sun, X., Karki, K., Zeng, C., Pandey, A., et al. (2020). Heavy Metals in Surface Sediments in the Trans-himalayan Koshi River Catchment: Distribution, Source Identification and Pollution Assessment. Chemosphere 244, 125410. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125410

Li, Y., Huang, J., Li, Z., and Zheng, K. (2020). Atmospheric Pollution Revealed by Trace Elements in Recent Snow from the central to the Northern Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Pollut. 263, 114459. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114459

Lin, L., Dong, L., Wang, Z., Li, C., Liu, M., Li, Q., et al. (2021). Hydrochemical Composition, Distribution, and Sources of Typical Organic Pollutants and Metals in Lake Bangong Co, Tibet. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 9877–9888. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-11449-w

Liu, H.-w., ShaojuanYu, J.-j. B., Yu, B., Liang, Y., Duo, B., Fu, J.-j., et al. (2019). Mercury Isotopic Compositions of Mosses, Conifer Needles, and Surface Soils: Implications for Mercury Distribution and Sources in Shergyla Mountain, Tibetan Plateau. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 172, 225–231. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.01.082

Liu, Y.-R., He, Z.-Y., Yang, Z.-M., Sun, G.-X., and He, J.-Z. (2016). Variability of Heavy Metal Content in Soils of Typical Tibetan Grasslands. RSC Adv. 6, 105398–105405. doi:10.1039/c6ra23868h

Liu, Y., Hou, S., Hong, S., Hur, S.-D., Lee, K., and Wang, Y. (2011). Atmospheric Pollution Indicated by Trace Elements in Snow from the Northern Slope of Cho Oyu Range, Himalayas. Environ. Earth Sci. 63, 311–320. doi:10.1007/s12665-010-0714-0

Long, E. R., Macdonald, D. D., Smith, S. L., and Calder, F. D. (1995). Incidence of Adverse Biological Effects within Ranges of Chemical Concentrations in marine and Estuarine Sediments. Environ. Manage. 19, 81–97. doi:10.1007/BF02472006

Luo, J., Tang, R., Sun, S., Yang, D., She, J., and Yang, P. (2015). Lead Distribution and Possible Sources along Vertical Zone Spectrum of Typical Ecosystems in the Gongga Mountain, Eastern Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Environ. 115, 132–140. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.05.022

Lüthi, Z. L., Škerlak, B., Kim, S.-W., Lauer, A., Mues, A., Rupakheti, M., et al. (2015). Atmospheric Brown Clouds Reach the Tibetan Plateau by Crossing the Himalayas. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 6007–6021. doi:10.5194/acp-15-6007-2015

McConnell, J. R., and Edwards, R. (2008). Coal Burning Leaves Toxic Heavy Metal Legacy in the Arctic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12140–12144. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803564105

MEPC (1990). Background Values of Soil Elements in China. Minist. Environ. Prot. People’s Republic China. China Environ. Sci. Press, 329–493.

MOH&SAC (2006). Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China & Standardization Administration of People’s Republic China. Available at: http://www.moh.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/cmsresources/zwgkzt/wsbz/new/20070628143525.

MOH&SAC (2017). Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China & Standardization Administration of People’s Republic China. GB 2762-2017 Stand.

Mu, C., Schuster, P. F., Abbott, B. W., Kang, S., Guo, J., Sun, S., et al. (2020). Permafrost Degradation Enhances the Risk of Mercury Release on Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 708, 135127. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135127

Nabulo, G., Oryem-Origa, H., and Diamond, M. (2006). Assessment of Lead, Cadmium, and Zinc Contamination of Roadside Soils, Surface Films, and Vegetables in Kampala City, Uganda. Environ. Res. 101, 42–52. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2005.12.016

Nickson, R., McArthur, J., Burgess, W., Ahmed, K. M., Ravenscroft, P., and Rahmanñ, M. (1998). Arsenic Poisoning of Bangladesh Groundwater. Nature 395, 338. doi:10.1038/26387

Planchon, F. A. M., Boutron, C. F., Barbante, C., Cozzi, G., Gaspari, V., Wolff, E. W., et al. (2002). Changes in Heavy Metals in Antarctic Snow from Coats Land Since the Mid-19th to the Late-20th Century. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 200, 207–222. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00612-X

Potapowicz, J., Szumińska, D., Szopińska, M., and Polkowska, Ż. (2019). The Influence of Global Climate Change on the Environmental Fate of Anthropogenic Pollution Released from the Permafrost. Sci. Total Environ. 651, 1534–1548. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.168

Qu, B., Zhang, Y., Kang, S., and Sillanpää, M. (2019). Water Quality in the Tibetan Plateau: Major Ions and Trace Elements in Rivers of the “Water Tower of Asia”. Sci. Total Environ. 649, 571–581. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.316

Ramesh, R., Ramanathan, A., Ramesh, S., Purvaja, R., and Subramanian, V. (2000). Distribution of Rare Earth Elements and Heavy Metals in the Surficial Sediments of the Himalayan River System. Geochem. J. 34, 295–319. doi:10.2343/geochemj.34.295

Salim, Z., Khan, M. U., and Malik, R. N. (2020). Concentration, Distribution and Association of Heavy Metals in Multi-Matrix Samples of Himalayan Foothill Along Elevation Gradients. Environ. Earth Sci. 79. doi:10.1007/s12665-020-09218-6

Shao, J.-j., Liu, C.-b., Zhang, Q.-h., Fu, J.-j., Yang, R.-q., Shi, J.-b., et al. (2017). Characterization and Speciation of Mercury in Mosses and Lichens from the High-Altitude Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Geochem. Health 39, 475–482. doi:10.1007/s10653-016-9828-y

Shao, J.-j., Shi, J.-b., Duo, B., Liu, C.-b., Gao, Y., Fu, J.-j., et al. (2016). Trace Metal Profiles in Mosses and Lichens from the High-Altitude Tibetan Plateau. RSC Adv. 6, 541–546. doi:10.1039/c5ra21920e

Shao, J., Shi, J., Duo, B., Liu, C., Gao, Y., Fu, J., et al. (2016). Mercury in Alpine Fish from Four Rivers in the Tibetan Plateau. J. Environ. Sci. 39, 22–28. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2015.09.009

Sheng, J., Wang, X., Gong, P., Tian, L., and Yao, T. (2012). Heavy Metals of the Tibetan Top Soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 19, 3362–3370. doi:10.1007/s11356-012-0857-5

Singh, A. K., and Singh, M. (2006). Lead Decline in the Indian Environment Resulting from the Petrol-Lead Phase-Out Programme. Sci. Total Environ. 368, 686–694. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.04.013

Singh, S. M., Sharma, J., Gawas-Sakhalkar, P., Upadhyay, A. K., Naik, S., Pedneker, S. M., et al. (2013). Atmospheric Deposition Studies of Heavy Metals in Arctic by Comparative Analysis of Lichens and Cryoconite. Environ. Monit. Assess. 185, 1367–1376. doi:10.1007/s10661-012-2638-5

Sun, R., Sun, G., Kwon, S. Y., Feng, X., Kang, S., Zhang, Q., et al. (2021). Mercury Biogeochemistry over the Tibetan Plateau: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Tech. 51, 577–602. doi:10.1080/10643389.2020.1733894

Sun, S., Kang, S., Huang, J., Chen, S., Zhang, Q., Guo, J., et al. (2017). Distribution and Variation of Mercury in Frozen Soils of a High-Altitude Permafrost Region on the Northeastern Margin of the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 15078–15088. doi:10.1007/s11356-017-9088-0

Sun, S., Kang, S., Huang, J., Li, C., Guo, J., Zhang, Q., et al. (2016). Distribution and Transportation of Mercury from Glacier to lake in the Qiangyong Glacier Basin, Southern Tibetan Plateau, China. J. Environ. Sci. 44, 213–223. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2015.09.017

Sun, S., Ma, M., He, X., Obrist, D., Zhang, Q., Yin, X., et al. (2020). Vegetation Mediated Mercury Flux and Atmospheric Mercury in the Alpine Permafrost Region of the Central Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 6043–6052. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b06636

Taylor, S. R., and Mclennan, S. M. (1985). The continental Crust: Its Composition and Evolution. Unite states.

Tripathee, L., Guo, J., Kang, S., Paudyal, R., Huang, J., Sharma, C. M., et al. (2019). Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Total Mercury in Atmospheric Wet Precipitation at Four Sites from the Nepal-Himalayas. Sci. Total Environ. 655, 1207–1217. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.338

Tripathee, L., Guo, J., Kang, S., Paudyal, R., Sharma, C. M., Huang, J., et al. (2020). Measurement of Mercury, Other Trace Elements and Major Ions in Wet Deposition at Jomsom: The Semi-arid Mountain valley of the Central Himalaya. Atmos. Res. 234, 104691. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2019.104691

Tripathee, L., Kang, S., Huang, J., Sharma, C. M., Sillanpää, M., Guo, J., et al. (2014). Concentrations of Trace Elements in Wet Deposition over the central Himalayas, Nepal. Atmos. Environ. 95, 231–238. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.06.043

Wang, B., Bao, Q., Hoskins, B., Wu, G., and Liu, Y. (2008). Tibetan Plateau Warming and Precipitation Changes in East Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, 14702. doi:10.1029/2008GL034330

Wang, G., Yan, X., Zhang, F., Zeng, C., and Gao, D. (2013). Traffic-related Trace Element Accumulation in Roadside Soils and Wild Grasses in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Ijerph 11, 456–472. doi:10.3390/ijerph110100456

Wang, G., Zeng, C., Zhang, F., Zhang, Y., Scott, C. A., and Yan, X. (2017). Traffic-Related Trace Elements in Soils along Six Highway Segments on the Tibetan Plateau: Influence Factors and Spatial Variation. Sci. Total Environ. 581–582, 811–821. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.018

Wang, P., Cao, J., Han, Y., Jin, Z., Wu, F., and Zhang, F. (2015). Elemental Distribution in the Topsoil of the Lake Qinghai Catchment, NE Tibetan Plateau, and the Implications for Weathering in Semi-arid Areas. J. Geochem. Explor. 152, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.gexplo.2014.12.008

Wang, X., Cheng, G., Zhong, X., and Li, M.-H. (2009). Trace Elements in Sub-Alpine forest Soils on the Eastern Edge of the Tibetan Plateau, China. Environ. Geol. 58, 635–643. doi:10.1007/s00254-008-1538-z

Wang, X., Dan, Z., Cui, X., Zhang, R., Zhou, S., Wenga, T., et al. (2020). Contamination, Ecological and Health Risks of Trace Elements in Soil of Landfill and Geothermal Sites in Tibet. Sci. Total Environ. 715, 136639. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136639

Wang, X., Gong, P., Wang, C., Ren, J., and Yao, T. (2016). A Review of Current Knowledge and Future Prospects Regarding Persistent Organic Pollutants Over the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 573, 139–154. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.08.107

Wang, X., Wang, C., Zhu, T., Gong, P., Fu, J., and Cong, Z. (2019). Persistent Organic Pollutants in the Polar Regions and the Tibetan Plateau: A Review of Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Environ. Pollut. 248, 191–208. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.093

Wang, Y., Pi, K., Fendorf, S., Deng, Y., and Xie, X. (2019). Sedimentogenesis and Hydrobiogeochemistry of High Arsenic Late Pleistocene-Holocene Aquifer Systems. Earth-Science Rev. 189, 79–98. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.10.007

WHO (2000). Air Quality Guidelines for Europe, Seconded. World Heal. European series: Organ regional publications, 125–154.

WHO (2011). Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. Available at: http://www.ho.int/water_sanitation_health/dwq/gdwq3rev/en/.

Wilkie, D., and La Farge, C. (2011). Bryophytes as Heavy Metal Biomonitors in the Canadian High Arctic. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 43, 289–300. doi:10.1657/1938-4246-43.2.289

Wu, J., Duan, D., Lu, J., Luo, Y., Wen, X., Guo, X., et al. (2016). Inorganic Pollution Around the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: An Overview of the Current Observations. Sci. Total Environ. 550, 628–636. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.136

Wu, J., Lu, J., Li, L., Min, X., and Luo, Y. (2018). Pollution, Ecological-Health Risks, and Sources of Heavy Metals in Soil of the Northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Chemosphere 201, 234–242. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.02.122

Wu, J., Lu, J., Li, L., Min, X., Zhang, Z., and Luo, Y. (2019). Distribution, Pollution, and Ecological Risks of Rare Earth Elements in Soil of the Northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 25, 1816–1831. doi:10.1080/10807039.2018.1475215

Xie, H., Li, J., Zhang, C., Tian, Z., Liu, X., Tang, C., et al. (2014). Assessment of Heavy Metal Contents in Surface Soil in the Lhasa-Shigatse-Nam Co Area of the Tibetan Plateau, China. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 93, 192–198. doi:10.1007/s00128-014-1288-4

Xiong, X., Zhang, K., Chen, Y., Qu, C., and Wu, C. (2020). Arsenic in Water, Sediment, and Fish of Lakes from the Central Tibetan Plateau. J. Geochem. Explor. 210, 106454. doi:10.1016/j.gexplo.2019.106454

Yang, K., Wu, H., Qin, J., Lin, C., Tang, W., and Chen, Y. (2014). Recent Climate Changes over the Tibetan Plateau and Their Impacts on Energy and Water Cycle: A Review. Glob. Planet. Change 112, 79–91. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2013.12.001

Yang, R., Jing, C., Zhang, Q., Wang, Z., Wang, Y., Li, Y., et al. (2011). Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) and Mercury in Fish from Lakes of the Tibetan Plateau. Chemosphere 83, 862–867. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.02.060

Yang, R., Yao, T., Xu, B., Jiang, G., and Xin, X. (2007). Accumulation Features of Organochlorine Pesticides and Heavy Metals in Fish from High mountain lakes and Lhasa River in the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Int. 33, 151–156. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2006.08.008

Yang, R., Zhang, S., and Wang, Z. (2014). Bioaccumulation and Regional Distribution of Trace Metals in Fish of the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Geochem. Health 36, 183–191. doi:10.1007/s10653-013-9538-7

Yao, T., Thompson, L. G., Mosbrugger, V., Zhang, F., Ma, Y., Luo, T., et al. (2012). Third Pole Environment (TPE). Environ. Dev. 3, 52–64. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2012.04.002

Ye, W., Saikawa, E., Avramov, A., Cho, S.-H., and Chartier, R. (2020). Household Air Pollution and Personal Exposure from Burning Firewood and Yak Dung in Summer in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Pollut. 263, 114531. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114531

Yin, A., and Harrison, T. M. (2003). Geologic Evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan Orogen. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 28, 211–280. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.28.1.211

Yongjie, Y., Yuesi, W., Tianxue, W., Wei, L., Ya'nan, Z., and Liang, L. (2009). Elemental Composition of PM2.5 and PM10 at Mount Gongga in China during 2006. Atmos. Res. 93, 801–810. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2009.03.014

You, Q., Min, J., and Kang, S. (2016). Rapid Warming in the Tibetan Plateau from Observations and CMIP5 Models in Recent Decades. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 2660–2670. doi:10.1002/joc.4520

Yu, C., Sun, Y., Zhong, X., Yu, Z., Li, X., Yi, P., et al. (2019). Arsenic in Permafrost-Affected Rivers and Lakes of Tibetan Plateau, China. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 31, 226–232. doi:10.1080/26395940.2019.1624198

Zhang, H., Fu, X., Lin, C.-J., Shang, L., Zhang, Y., Feng, X., et al. (2016a). Monsoon-Facilitated Characteristics and Transport of Atmospheric Mercury at a High-Altitude Background Site in Southwestern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 13131–13148. doi:10.5194/acp-16-13131-2016

Zhang, H., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Ding, M., and Li, L. (2015). Identification of Traffic-Related Metals and the Effects of Different Environments on Their Enrichment in Roadside Soils along the Qinghai-Tibet Highway. Sci. Total Environ. 521–522, 160–172. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.03.054

Zhang, H., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., and Hu, Z. (2012). The Effects of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway on Heavy Metals Enrichment in Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 439, 240–248. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.09.027

Zhang, H., Yin, R.-s., Feng, X.-b., Sommar, J., Anderson, C. W. N., Sapkota, A., et al. (2013a). Atmospheric Mercury Inputs in Montane Soils Increase with Elevation: Evidence from Mercury Isotope Signatures. Sci. Rep. 3. doi:10.1038/srep03322

Zhang, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., and Ding, M. (2013b). Heavy Metal Enrichment in the Soil Along the Delhi-Ulan Section of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway in China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 185, 5435–5447. doi:10.1007/s10661-012-2957-6

Zhang, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., Ding, M., Jiang, Y., and Xie, Z. (2016b). Traffic-related Metal(loid) Status and Uptake by Dominant Plants Growing Naturally in Roadside Soils in the Tibetan Plateau, China. Sci. Total Environ. 573, 915–923. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.08.128

Zhang, J.-W., Yan, Y.-N., Zhao, Z.-Q., Li, X.-D., Guo, J.-Y., Ding, H., et al. (2021). Spatial and Seasonal Variations of Dissolved Arsenic in the Yarlung Tsangpo River, Southern Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 760, 143416. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143416

Zhang, N., Cao, J., Ho, K., and He, Y. (2012). Chemical Characterization of Aerosol Collected at Mt. Yulong in Wintertime on the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Res. 107, 76–85. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2011.12.012

Zhang, N., Cao, J., Liu, S., Zhao, Z., Xu, H., and Xiao, S. (2014). Chemical Composition and Sources of PM2.5 and TSP Collected at Qinghai Lake During Summertime. Atmos. Res. 138, 213–222. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2013.11.016

Zhang, Q., Pan, K., Kang, S., Zhu, A., and Wang, W.-X. (2014). Mercury in Wild Fish from High-Altitude Aquatic Ecosystems in the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 5220–5228. doi:10.1021/es404275v

Zhang, S., Yang, G., Hou, S., Zhang, T., Li, Z., and Du, W. (2021). Analysis of Heavy Metal-Related Indices in the Eboling Permafrost on the Tibetan Plateau. Catena 196, 104907. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2020.104907

Zhang, Y., Sillanpää, M., Li, C., Guo, J., Qu, B., and Kang, S. (2015). River Water Quality Across the Himalayan Regions: Elemental Concentrations in Headwaters of Yarlung Tsangbo, Indus and Ganges River. Environ. Earth Sci. 73, 4151–4163. doi:10.1007/s12665-014-3702-y

Zhang, Z., Zheng, D., Xue, Z., Wu, H., and Jiang, M. (2019). Identification of Anthropogenic Contributions to Heavy Metals in Wetland Soils of the Karuola Glacier in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 98, 678–685. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.11.052

Zhu, T., Wang, X., Lin, H., Ren, J., Wang, C., and Gong, P. (2020). Accumulation of Pollutants in Proglacial Lake Sediments: Impacts of Glacial Meltwater and Anthropogenic Activities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 7901–7910. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c01849

Keywords: heavy metals, Tibetan plateau, inorganic pollution, cryosphere, climate change

Citation: Wang W, Ji X, Abakumov E, Polyakov V, Li G and Wang D (2022) Assessing Sources and Distribution of Heavy Metals in Environmental Media of the Tibetan Plateau: A Critical Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:874635. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.874635

Received: 12 February 2022; Accepted: 22 March 2022;

Published: 12 April 2022.

Edited by:

Wenxin Zhang, Lund University, SwedenReviewed by:

Maierdang Keyimu, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography (CAS), ChinaXiao-San Luo, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, China

Copyright © 2022 Wang, Ji, Abakumov, Polyakov, Li and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Evgeny Abakumov, ZV9hYmFrdW1vdkBtYWlsLnJ1

Wenjuan Wang

Wenjuan Wang Xiaowen Ji2

Xiaowen Ji2 Evgeny Abakumov

Evgeny Abakumov