- 1State Key Laboratory of Freshwater Ecology and Biotechnology, Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan, China

- 2College of Advanced Agricultural Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

- 3State Environmental Protection Key Laboratory of Environmental Risk Assessment and Control on Chemical Process, School of Resource and Environmental Engineering, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China

- 4Department of Chemistry, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

- 5Institute of Pesticide and Environmental Toxicology, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

- 6Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Beijing, China

Decabromodiphenyl ethane (DBDPE), a novel brominated flame retardant, may co-exist with other pollutants including nanoparticles (NPs) in aquatic environment. Due to structural similarity with decabromodiphenyl ether, DBDPE has been reported to exhibit thyroid disrupting effects and neurotoxicity. This study further evaluated the behavior of DBDPE in aqueous environments along with the bioavailability and toxicity of DBDPE in aquatic organisms in the presence of TiO2 nanoparticles (n-TiO2). When co-existing in an aqueous environment, DBDPE was adsorbed by n-TiO2, potentially facilitating the sedimentation of DBDPE from the aqueous phase. Co-exposure to DBDPE and n-TiO2 significantly increased the uptake of DBDPE by zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos and altered the composition of metabolites in zebrafish larvae compared to zebrafish exposed to DBDPE alone. The DBDPE-induced increases in heart rate, tail bending frequency, average speed under dark/light stimulation, and thyroid hormone levels in zebrafish embryos/larvae were further enhanced in the presence of n-TiO2. Overall, the results demonstrate that n-TiO2 affected the behavior of DBDPE in the aqueous phase and increased the bioavailability and biotoxicity of DBDPE in zebrafish embryos/larvae. These results could be helpful for understanding the environmental behavior and toxicity of DBDPE.

1 Introduction

As an alternative to decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209), decabromodiphenyl ethane (DBDPE) has been extensively used in consumer products such as plastics, foams, textiles, furniture, and electronic devices (Covaci et al., 2011; Shi Z. et al., 2018). DBDPE has become one of the most commonly used brominated flame retardants worldwide (Rauert et al., 2018; Xiong et al., 2019). Consequently, DBDPE has been detected in various biological and abiotic media such as air, indoor dust, surface water, sediment, wildlife, and even human beings (Chen et al., 2019; Wemken et al., 2019; Harrad et al., 2020; Zuiderveen et al., 2020). Previous studies have detected DBDPE at concentrations of up to 107 ng/L in surface water of the Xiaoqing River Basin (Zhen et al., 2018) and even 990 ng/L in Sewage from Sewage Outlet in Dongjiang River (Zeng et al., 2011) and 1700 ± 744 ng/g lipid weight in crucian carp (Carassius auratus) from an e-waste recycling site in South China (Tao et al., 2019). Moreover, environmental monitoring in the Bohai Sea revealed that the ratio of DBDPE to BDE-209 exceeded two in the aqueous phase and four in air (Liu et al., 2020). Notably, DBDPE may have higher bioavailability in some organisms and persist longer in the environment compared to BDE-209 (Wu et al., 2020a; Liu et al., 2020). Therefore, it is important to evaluate the potential ecological and health risks of DBDPE based on an in-depth understanding of its environmental behavior, bioavailability, and biotoxicity.

DBDPE was initially considered as an environmentally friendly alternative to BDE-209 with low acute toxicity in chicken embryos at a dose of 0.1 μM (Egloff et al., 2011) and no marked acute toxicity to fish, algae, or Daphnia magna at concentrations up to 110 mg/L (Hardy et al., 2012). However, recent studies have suggested that DBDPE leads to thyroid endocrine disruption and developmental neurotoxicity due to structural similarity between BDE-209 and thyroid hormones (Sun et al., 2018; Wang X. et al., 2019; Wang Y. et al., 2019). For example, waterborne exposure to DBDPE at concentrations of 0, 2.91, 9.71, 29.14, 97.12 and 291.36 μg/L significantly increased the whole-body contents of triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) in zebrafish larvae (Wang X. et al., 2019). In addition, the short-term exposure to sediment containing DBDPE caused low-level developmental neurotoxicity in zebrafish larvae (Jin et al., 2018). Understanding the toxicity of DBDPE is complicated by the fact that organic pollutants do not exist alone in the environment. Thus, the potential risk of these chemicals may be underestimated or overestimated by using toxicological data based only on single exposure.

Nanoparticles (NPs), with large surface areas, have received close attention because they can adsorb organic pollutants and change their behavior in the environment and toxicity in organisms (Liu et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). As a common engineered nanomaterial, nano-TiO2 (n-TiO2) has been widely applied in various domains and been detected in the environment worldwide (Kaegi et al., 2017; Pradas del Real et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2020). Concentrations of n-TiO2 up to 43 μg/L have been reported in wastewater treatment plant effluent (Shi et al., 2016). The estimated concentrations of n-TiO2 reached 103 μg/L in the coastal waters of the San Francisco Bay (Garner et al., 2017) and even exceeded 900 μg/L in surface water near popular beaches in France (Labille et al., 2020). Furthermore, recent studies have reported that the concentration of Ti-NPs ranged from 0.09 to 10.2 μg/L in water samples (Wu et al., 2020b) and DBDPE ranged from 3.1 to 64.8 ng/g lipid weight in fishes (Zheng et al., 2018) in Taihu Lake, China. These studies suggested that DBDPE may co-exist with n-TiO2 in the aquatic environment. In a previous study, when BDE-209 was mixed with a n-TiO2 suspension, the measured concentration was decreased 35% after 24 h, indicating that n-TiO2 adsorbed BDE-209 to form settleable mixture thus changed its original existence in water (Wang et al., 2014). Furthermore, the presence of n-TiO2 enhanced the accumulation of BDE-209, leading to thyroid endocrine disruption and developmental neurotoxicity in zebrafish larvae (Wang et al., 2014). Since DBDPE has very similar chemical structure and physicochemical properties with BDE-209, we suppose that DBDPE may exhibit similar changes in environmental behavior and toxicity when co-existing with n-TiO2.

Above all, the main objectives of this study were to determine whether n-TiO2 1) affects the existence of waterborne DBDPE; 2) affects the uptake and metabolism of DBDPE in zebrafish larvae; and 3) affects the potential toxicity of DBDPE in zebrafish larvae. The results could be helpful for understanding the environmental behavior and biotoxicity of both pollutants.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals

DBDPE (CAS No. 84852-53-9, purity >96%) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The DBDPE standard used in chemical analysis was purchased from AccuStandard, Inc. (New Haven, CT). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), which was used to make the stock solutions of DBDPE (0.1% v/v), was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Methanesulfonate (MS-222) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), while n-TiO2 (CAS: 13,463-67-7; purity >99.9%) was purchased from Wan Jing New Material Company (Hangzhou, China). According to the manufacturer, the n-TiO2 had a diameter of 7.04 nm. All other chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and trace metal analysis grade for TiO2 analysis.

2.2 Analysis of n-TiO2 and DBDPE in Aqueous Solution

The preparation and characterization of the n-TiO2 were performed according to previously described methods (Wang et al., 2014). A series of aqueous solutions containing n-TiO2 (100 μg/L) and different concentrations of DBDPE (0, 1, 10, or 100 μg/L) were prepared in ultrapure water. The average diameters and zeta potentials were analyzed using dynamic light scattering (DLS) with a Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, United Kingdom). The chosen concentration of n-TiO2 (100 μg/L) is environmentally relevant and has been shown to enhance the bioavailability and toxicity of BDE-209 (Wang et al., 2014). The concentrations of DBDPE were chosen according to previous reports of thyroid hormone disruption and developmental toxicity upon single exposure; the lowest studied concentration of DBDPE can be considered to be environmentally relevant (Wang X. et al., 2019).

According to the obtained results, 10 μg/L was chosen to study the dynamics of DBDPE in the presence of n-TiO2. Samples (12 ml) of each DBDPE/n-TiO2 solution (n = 3 replicates) were collected at 0, 4, 8, 12, 20, and 24 h after mixing the DBDPE and n-TiO2 solutions. After centrifugation for 10 min at 12,000 × g, the supernatants were collected for determination of DBDPE by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) in electron-capture negative ionization mode (Agilent 7,890A-5975C; Agilent Technologies, DE, United States). The detailed protocols for sample collection, pretreatment, and chemical analysis are shown in the supplementary material (Supplementary Text S1).

2.3 Zebrafish Maintenance and Exposure

Adult wild-type zebrafish (Danio rerio; AB strain) were maintained at 28 ± 0.5°C (14 h light: 10 h dark), and the embryos were reared and collected as previously described (Wang X. et al., 2019). In general, 300 normally developed embryos (2 h post fertilization, hpf) were selected and distributed in a glass beaker containing 100 ml of DBDPE solution (0, 1, 10, or 100 μg/L) alone or in combination with n-TiO2 (100 μg/L) until 144 hpf and each treatment included three replicates. Each day, the dead embryos/larvae and 80% exposure solutions was renewed. The same volume of exposure solution was replenished to each beaker. The live embryos/larvae and 20% exposure solutions were kept in the beaker to reduce disruption. All studies were conducted according to the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals of the National Institute for Food and Drug Control of China, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

2.4 Analysis of n-TiO2, DBDPE, and DBDPE Metabolites in Zebrafish Larvae

The contents of n-TiO2, DBDPE, and possible DBDPE metabolites were determined in zebrafish larvae at 144 hpf. For the analyses of DBDPE and its metabolites, 100 larvae from each replicate (n = 3 replicates) were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C before analysis. The samples were pretreated and analyzed by GC–MS (Agilent 7,890A-5975C) with electron-capture negative ionization. The quantitation of DBDPE and identification of its possible metabolites were conducted in selective ion monitoring mode (m/z = 79 and 81) as previously described (Wang X. et al., 2019). The recovery of spiked DBDPE was 81 ± 16%. To quantify n-TiO2, according to (Wang et al., 2014), 100 zebrafish larvae for each treatment (n = 3 replicates) were collected, and then added concentrated nitric acid. After digestion for a night, n-TiO2 were converted into Ti4+ via a double decomposition reaction. The Ti4+ concentrations in the supernatants were quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography in combination with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (NexION300X, PekinElmer, Santa Clara, CA). The Ti concentrations were quantified by a Ti standard curve and then converted to TiO2 concentrations via molecular weight conversion. The recovery for the n-TiO2 quantification technique ranged from 94 to 107%. Detailed protocols for sample collection, pretreatment, and chemical analysis are found in the supplementary material (Supplementary Texts S1, S2).

2.5 Evaluation of DBDPE-Induced Thyroid Disruption and Neurotoxicity in Zebrafish Larvae in the Presence of n-TiO2

2.5.1 Behavioral Assays

We assessed three kinds of behaviors of zebrafish embryos/larvae, including embryonic spontaneous tail bending, free-swimming movement and locomotion behavior in response to dark-to-light transitions as previous described (Chen et al., 2017).

At 24 hpf, eight embryos were randomly selected from each replicate beaker and transferred to a 24-well plate (eight embryos per well). The 24-well plate was placed under a dissection microscope, and videotaped 1 min by a CCD camera after 5 min acclimation. The times of spontaneous tail bending were counted for each embryo, and there were 24 embryos for each group (eight embryos per replicate × three replicates).

At 144 hpf, we randomly selected 24 zebrafish larvae from each exposure group (eight larvae per replicate × three replicates) and transferred to a 24-well plate (one larvae per well) for the other two motor behaviors test. After 5 min acclimation, 10 min visible light of free-swimming movement and subsequently 20 min dark-to-light transitions (5 min dark-5 min light-5 min dark-5 min light) of locomotion behavior were monitored by using a Zebralab Video-Track system (View Point Life Sciences, Inc., Montreal, Canada).

2.5.2 Neurotransmitter Measurements

At 144 hpf, 50 zebrafish larvae were collected from each treatment (n = 3 replicates) to determine the contents of neurotransmitters as previously described (Gonzalez et al., 2011; Shi Q. et al., 2018). The neurotransmitter contents were quantified using a high-performance liquid chromatography system (ACQUITY UPLC H-class-Xevo TQ MS, Waters, Ireland). Detailed protocols of sample pretreatment are shown in the supplementary material (Supplementary Text S3).

2.5.3 Measurement of Thyroid Hormones (TH) Contents

At 144 hpf, 200 zebrafish larvae were collected from each treatment (n = 3 replicates) to determine the whole-body TH contents as previously described (Yu et al., 2011). The total T4 (tT4) and T3 (tT3) contents were measured using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test kits (Wuhan EIAab Science Co. Ltd., Wuhan, China). The detection limits, intra-assay variation, inter-assay variation, and mean recoveries of tT4 were 1.2 ng/ml, 4.3, 7.5, and 74.46 ± 2.54%, respectively, while those of tT3 were 0.1 ng/ml, 4.5, 7.2, and 61.20 ± 0.82%, respectively. The detailed sample pretreatment process can be found in the supplementary material (Supplementary Text S4).

2.5.4 Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

At 144 hpf, 30 zebrafish larvae were collected from each treatment (n = 3 replicates) to extract total RNA according to the protocol of (Yu et al., 2010). qRT-PCR was carried out using SYBR® Real-time PCR Master Mix-Plus kits (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) and an ABI 7300 system (Applied Biosystems, CA, United States). The gene primer sequences were obtained from the literatures or identified using the online program Primer 3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/; see Supplementary Table S1) and ribosomal protein L8 (rpl8) was used as a reference gene to calculate the relative gene transcriptional levels based on the 2−ΔΔCt method. The detailed protocols for qRT-PCR are provided in the supplementary material (Supplementary Text S5).

2.5.5 Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

Protein extraction and western blot analysis were performed by following the previous method (Shi Q. et al., 2018). At 144 hpf, 100 zebrafish larvae were collected from each treatment (n = 3 replicates) to extract total protein with a commercial kit (KeyGen Biotech, Nanjing, China) and the protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford method. The expressions of proteins [synapsin IIa (SYN2a) and α1-TUBULIN] were quantified by densitometry with the results normalized to the expression of GADPH. The rabbit SYN2a antibody (Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany) and rabbit α1-tubulin antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) have been previously confirmed reactive and suitable for zebrafish studies (Shi Q. et al., 2018). The relative optical density of the band was measured with the ImageJ software. The detailed procedure can be found in the supplementary material (Supplementary Text S6).

2.6 Molecular Docking

The crystal structures of two target proteins, human corticotropin releasing factor receptor type 1 (CRFR1; PDB code, 3EHS) and human thyroid hormone receptor beta (TRβ; PDB code, 1N46) were obtained from the RCSB protein databank (http://www.pdb.org). The molecular docking of DBDPE and the target proteins was performed using Discovery Studio 2016 with the Dock Ligands (CDOCKER) protocol. Detailed information is provided in the supplementary material (Supplementary Text S7).

2.7 Statistical Analysis

Data normality was analyzed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, while data homogeneity was evaluated by Levene’s test. All data are expressed as mean ± standard error (SEM), and each treatment included three replicates. The differences between the control group and each exposure group were evaluated by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test using SPSS software (v22, IBM Corp, NY, United States). The differences between single-exposure and co-exposure groups were evaluated by Student’s t-test. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Size of n-TiO2 and Adsorption of DBDPE in Aqueous Solution

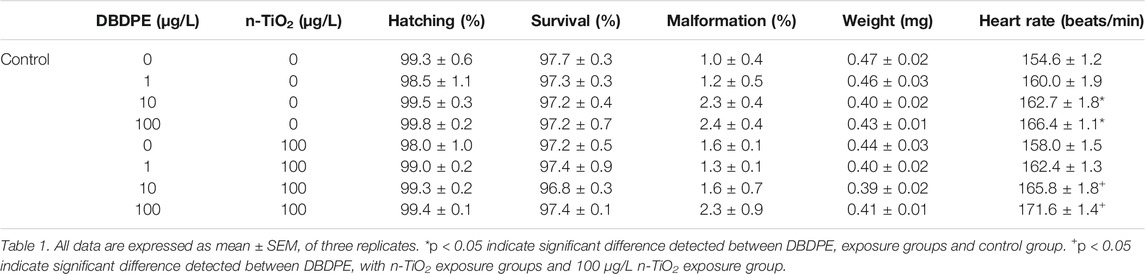

Based on DLS analysis, most n-TiO2 particles had sizes in the following ranges: 60–120 nm, 120–250 nm, 150–300 nm, and 200–360 nm. When n-TiO2 co-existed with DBDPE at concentrations of 0, 1, 10, and 100 μg/L, the largest n-TiO2 sizes were approximately 200, 300, 360 and 400 nm, respectively (Figures 1A–D). The zeta potentials of the aqueous solutions of n-TiO2 (100 μg/L) in combination with 0, 1, 10, and 100 μg/L DBDPE were −11.45 ± 1.15, −11.43 ± 1.49, −12.83 ± 1.20, and −23.44 ± 1.85 mV, respectively (Figure 1E). The measured concentration of DBDPE in the supernatant of the solution containing 10 μg/L DBDPE +100 μg/L n-TiO2 decreased in a time-dependent manner over 24 h (***p < 0.001; Figure 1F).

FIGURE 1. Number-based size distribution of nanoparticles in aqueous solutions of 100 μg/L n-TiO2 with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μg/L DBDPE (A–D). Zeta potentials of solutions of 100 μg/L n-TiO2 containing different concentrations (0, 1, 10, and 100 μg/L) of DBDPE (E). Aqueous-phase DBDPE content vs. time in solutions of 10 μg/L DBDPE with and without 100 μg/L n-TiO2 over 24 h (F). ***p < 0.001 indicates a significant difference between the co-exposure group and the corresponding DBDPE single-exposure group without n-TiO2.

3.2 Effects of n-TiO2 on the Bioavailability and Metabolism of DBDPE in Zebrafish Larvae

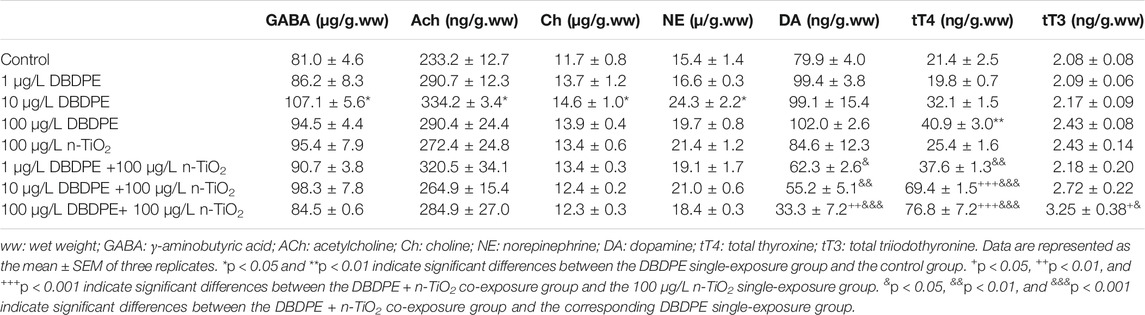

In zebrafish larvae (144 hpf), the concentrations of n-TiO2 were significantly increased when co-exposed to 10 or 100 μg/L DBDPE compared to single n-TiO2 exposure (*p < 0.05; Figure 2A). The accumulation of DBDPE was detected in zebrafish larvae exposed to 10 or 100 μg/L DBDPE with or without n-TiO2, and the DBDPE concentration in the group exposed to 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 was significantly higher than that in the group exposed to only DBDPE at 100 μg/L (&&&p < 0.001; Figure 2B). The concentrations of DBDPE in the other groups were below the limit of detection.

FIGURE 2. Accumulation and metabolism of DBDPE and n-TiO2 in 144-hpf zebrafish larvae following exposure to DBDPE alone or in combination with n-TiO2. dw: dry weight. (A) Contents of n-TiO2. (B) Contents of DBDPE. ((C) and c) Metabolites of DBDPE and the composition of metabolites in 144-hpf zebrafish larvae exposed to 10 μg/L DBDPE. ((D) and d) Metabolites of DBDPE and the composition of metabolites in 144-hpf zebrafish larvae exposed to 10 μg/L DBDPE +100 μg/L n-TiO2. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three replicates (100 larvae per replicate). *p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between a DBDPE single-exposure group and the control group. &&&p < 0.001 indicates a significant difference between a co-exposure group and the corresponding DBDPE single-exposure group without n-TiO2.

The possible metabolites of DBDPE were also analyzed in 144-hpf zebrafish larvae exposed 10 μg/L DBDPE alone or in combination with n-TiO2. In general, 14 peaks were identified as possible metabolites of DBDPE, including nona-BDPE, nona-brominated products, octa-BDPE, hepta-BDPE, and also other-brominated products (Figures 2C,D). The percentages of DBDPE, nona-BDPE, nona-brominated products, octa-BDPE, hepta-BDPE, and other-brominated products were 17, 20, 4, 32, 22, and 5% in the group exposed to 10 μg/L DBDPE, respectively (Figure 2C), and 27, 34, 12, 15, 9, and 3% in the group exposed to 10 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2, respectively (Figure 2D).

3.3 Effects of n-TiO2 on DBDPE-Induced Thyroid Disruption and Neurotoxicity in Zebrafish Larvae

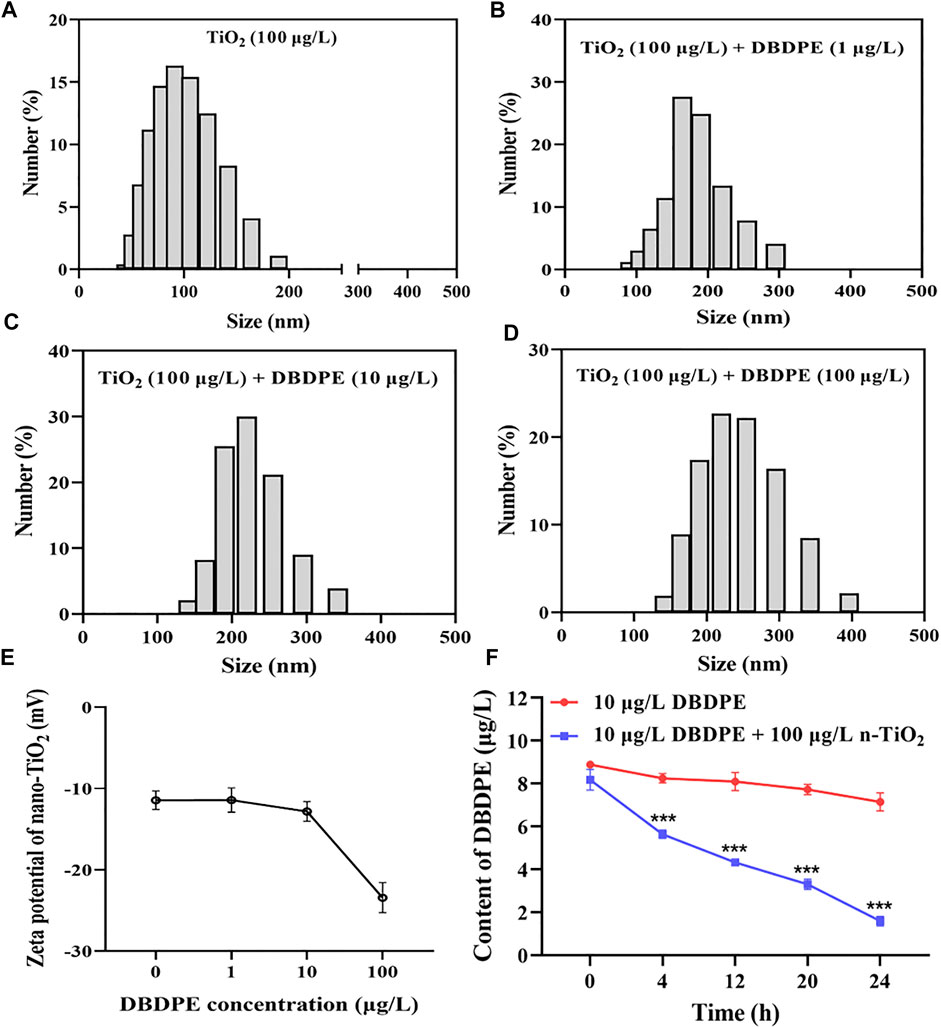

3.3.1 Developmental Toxicity

No significant differences in the hatching rate, survival rate, malformation rate, and body weight of zebrafish larvae were observed among all groups (Table 1). However, the heart rates were significantly increased the group exposed to 10 or 100 μg/L DBDPE compared to the control group (*p < 0.05, Table 1). Moreover, the heart rates were significantly increased in the groups exposed to 10 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 and 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 compared to the group exposed to n-TiO2 alone (+p < 0.05, Table 1).

3.3.2 Alterations in Locomotor Behavior

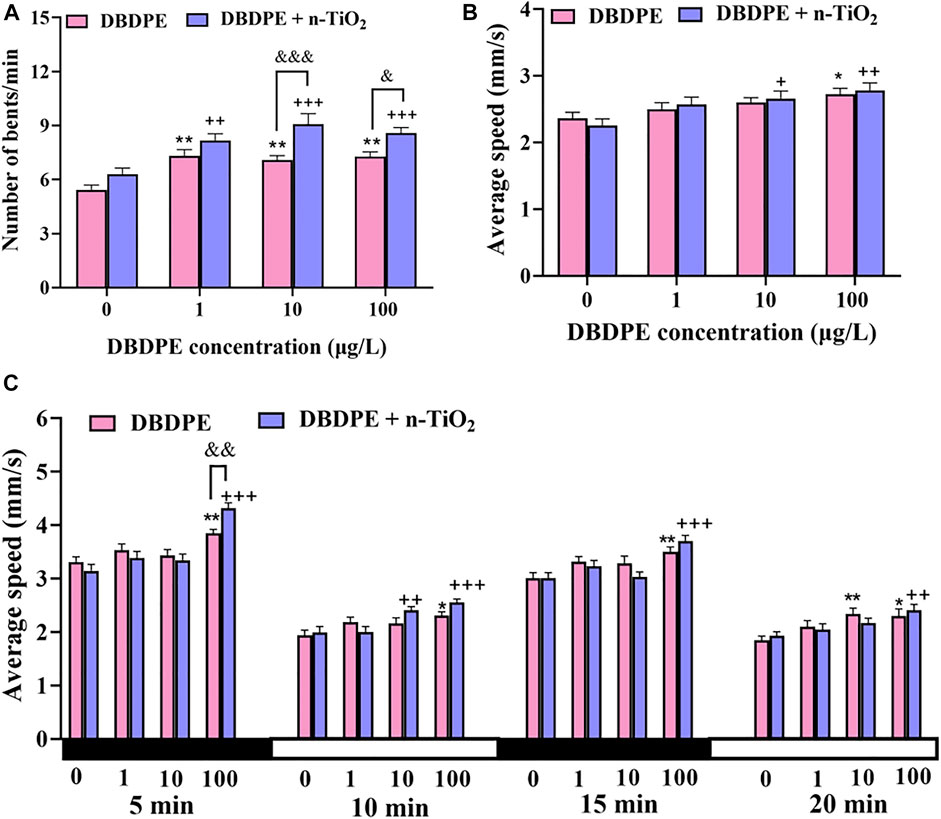

At 24 hpf, the frequencies of side-to-side tail contraction of zebrafish embryos were significantly increased in the groups exposed to DBDPE at 1, 10, and 100 μg/L compared with the control (**p < 0.01, Figure 3A). The presence of n-TiO2 further enhanced these increases, with significant differences observed between the groups treated with 10 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 group and 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 compared to the corresponding single-exposure groups (&p < 0.05, Figure 3A). And significant increases were observed in 10 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 group at 22 hpf and 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 group at 28 hpf compared to the corresponding single-exposure groups (*p < 0.05, Supplementary Figures S1A–D).

FIGURE 3. Behavioral changes in zebrafish embryos/larvae following exposure to DBDPE alone or in combination with n-TiO2. (A) Tail bending frequency of zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf. (B) Average swimming speed under continuous light in zebrafish larvae at 144 hpf. (C) Average swimming speed in zebrafish larvae under dark/light stimulation at 144 hpf. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (24 individuals). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 indicate significant differences between the DBDPE single-exposure group and the control group. +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, and +++p < 0.001 indicate significant differences between the DBDPE/n-TiO2 co-exposure groups and the 100 μg/L n-TiO2 single-exposure group. &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01, and &&&p < 0.001 indicate significant differences between the co-exposure groups and the corresponding DBDPE single-exposure groups without n-TiO2.

The average speeds of zebrafish larvae under continuous light were significantly increased in the group exposed to 100 μg/L DBDPE compared to the control group (*p < 0.05, Figure 3B) and in the groups exposed to 10 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 and 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 compared to the n-TiO2 exposure group (+p < 0.05, Figure 3B). No significant differences in average speed were observed between any of the DBDPE + n-TiO2 co-exposure groups and the corresponding single DBDPE exposure group (Figure 3B).

The average speed of zebrafish larvae at 144 hpf was significantly increased by exposure to 100 μg/L DBDPE, either alone (**p < 0.01 compared with the control group) or in combination with n-TiO2 (+++p < 0.001 compared to the n-TiO2 group; Figure 3C). However, significant differences between the group exposed to 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 and the 100 μg/L DBDPE exposure group were only observed during the first dark cycle (&&p < 0.01, Figure 3C). In addition, compared to the control group, the average speed of zebrafish larvae was significantly increased by exposure to 10 μg/L DBDPE (first light cycle) and 100 μg/L DBDPE (first and second cycles; *p < 0.05; Figure 3C). Compared to the n-TiO2 single-exposure group, significant differences in average larvae speed were also observed upon exposure to 10 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 (second light cycle) and 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 (first and second cycles; ++ p < 0.01; Figure 3C). And locomotor traces of 144-hpf zebrafish larvae under dark/light stimulation were observed in the supplementary material (Supplementary Figure S1E).

3.3.3 Effects on the Contents of Thyroid Hormones and Neurotransmitters

The tT4 levels showed significant increases upon single exposure to DBDPE at 100 μg/L compared with the control group (**p < 0.01, Table 2). The tT4 levels also increased upon n-TiO2/DBDPE co-exposure at DBDPE concentrations of 10 and 100 μg/L compared to the n-TiO2 single-exposure group (+++p < 0.001, Table 2). In all co-exposure groups, the tT4 levels were significantly higher compared to the corresponding single-exposure DBDPE groups (&&p < 0.01, Table 2). The tT3 levels were significantly higher in the 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 co-exposure group compared to the n-TiO2 single-exposure group (+p < 0.05) and compared to the 100 μg/L DBDPE single-exposure group (&p < 0.05, Table 2).

The whole-body contents of neurotransmitters including γ-aminobutyric (GABA), Acetycholine (Ach), choline (Ch), and norepinephrine (NE) in 144-hpf zebrafish larvae were significantly increased in the 10 μg/L DBDPE single-exposure group compared with the control group (*p < 0.05, Table 2). Compared to the n-TiO2 single-exposure group, the dopamine (DA) contents were not significantly different in any of the DBDPE single-exposure groups, whereas they were markedly increased in the 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 co-exposure group (++p < 0.01, Table 2). The DA contents were significantly increased in all DBDPE + n-TiO2 co-exposure groups compared to the corresponding DBDPE single-exposure groups (&p < 0.05, Table 2).

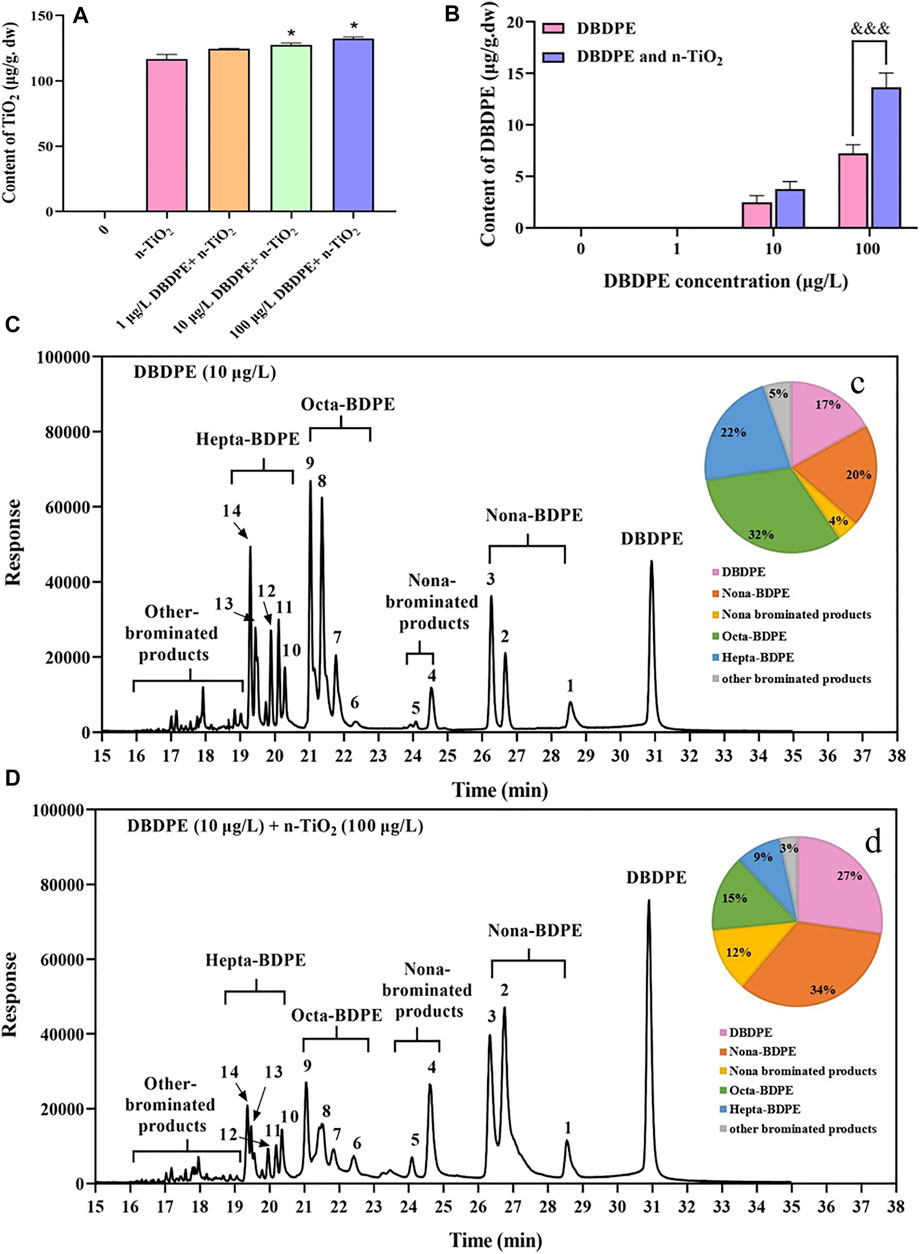

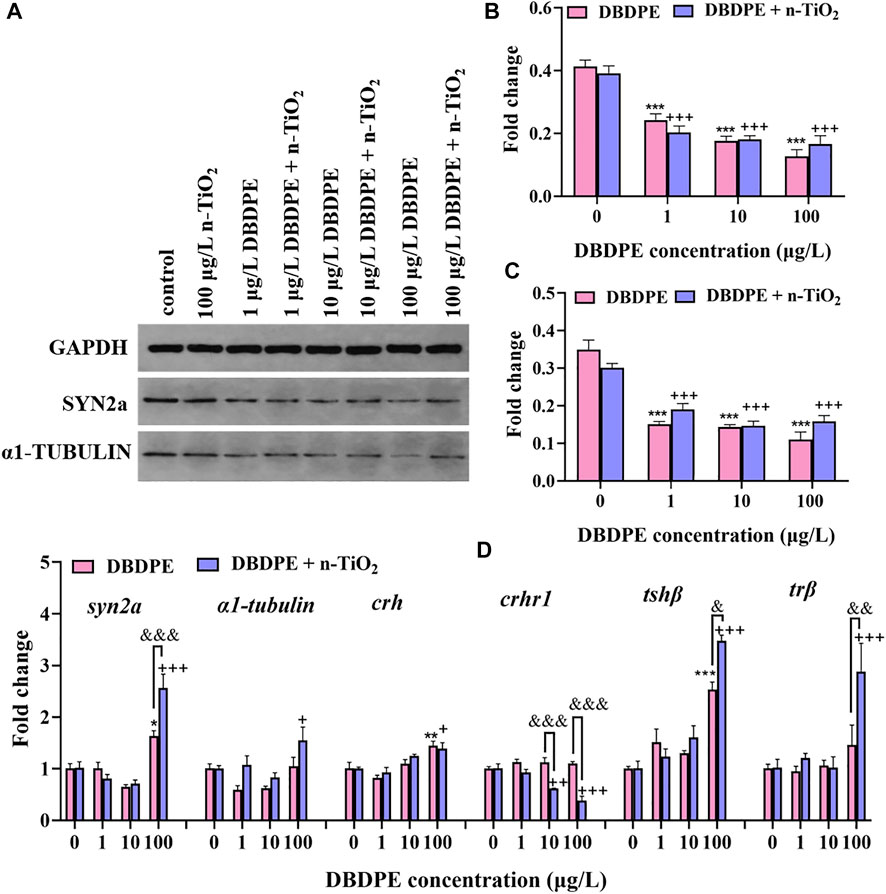

3.3.4 Alterations in Protein Expression and Gene Transcription

At the protein level, the protein expressions of SYN2a and α1-TUBULIN were examined in 144-hpf zebrafish larvae by western blotting (Figure 4A). The SYN2a and α1-TUBULIN expressions were significantly decreased in all groups exposed to DBPDE, either alone or with n-TiO2, compared to the control group (***p < 0.001) and the n-TiO2 single-exposure group (+++p < 0.001, Figures 4B,C). No differences in protein expression were observed between the DBDPE + n-TiO2 co-exposure groups and the corresponding DBDPE single-exposure groups.

FIGURE 4. Alterations in protein expression and gene transcription level. (A) Representative western blot image of GAPDH, SYN2a, and α1-TUBULIN. (B) Relative protein levels of SYN2a. (C) Relative protein levels of α1-tubulin. (D) Relative transcription levels of genes related to neurodevelopment (syn2a and α1-tubulin) and thyroid hormone synthesis and function (crh, crhr1, tshβ, and trβ). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three replicates (30 zebrafish larvae per replicate). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 indicate significant differences between DBDPE single-exposure groups and the control group. +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, and +++p < 0.001 indicate significant differences between DBDPE/n-TiO2 co-exposure groups and the 100 μg/L n-TiO2 single-exposure group. &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01, and &&&p < 0.001 indicate significant differences between the co-exposure groups and the corresponding DBDPE single-exposure groups without n-TiO2.

At the transcriptional level, we examined the relative transcription levels of genes related to central nervous system development and thyroid hormones, including synapsin IIa (syn2a), α1-tubulin, corticotropin releasing hormone (crh), corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1 (crhr1), thyroid stimulating hormone subunit beta (tshβ), and thyroid hormone receptor beta (trβ; Figure 4D). The transcript levels of syn2a, crh, and tshβ were significantly increased upon single exposure to 100 μg/L DBDPE compared to the control group (*p < 0.05, Figure 4D). The transcript levels of syn2a, α1-tubulin, tshβ, and trβ were significantly increased upon co-exposure to 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 compared to the n-TiO2 single-exposure group (+p < 0.05, Figure 4D). Significant differences in the transcription levels of syn2a, tshβ, and trβ were observed between the 100 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2 co-exposure group and the 100 μg/L DBDPE single-exposure group (&p < 0.05, Figure 4D). In contrast, the transcript level of crhr1 was significantly decreased in the groups co-exposed to n-TiO2 and DBDPE at 10 and 100 μg/L compared to the n-TiO2 single-exposure group (++p < 0.01) and the corresponding DBDPE single-exposure groups (&&&p < 0.001, Figure 4D).

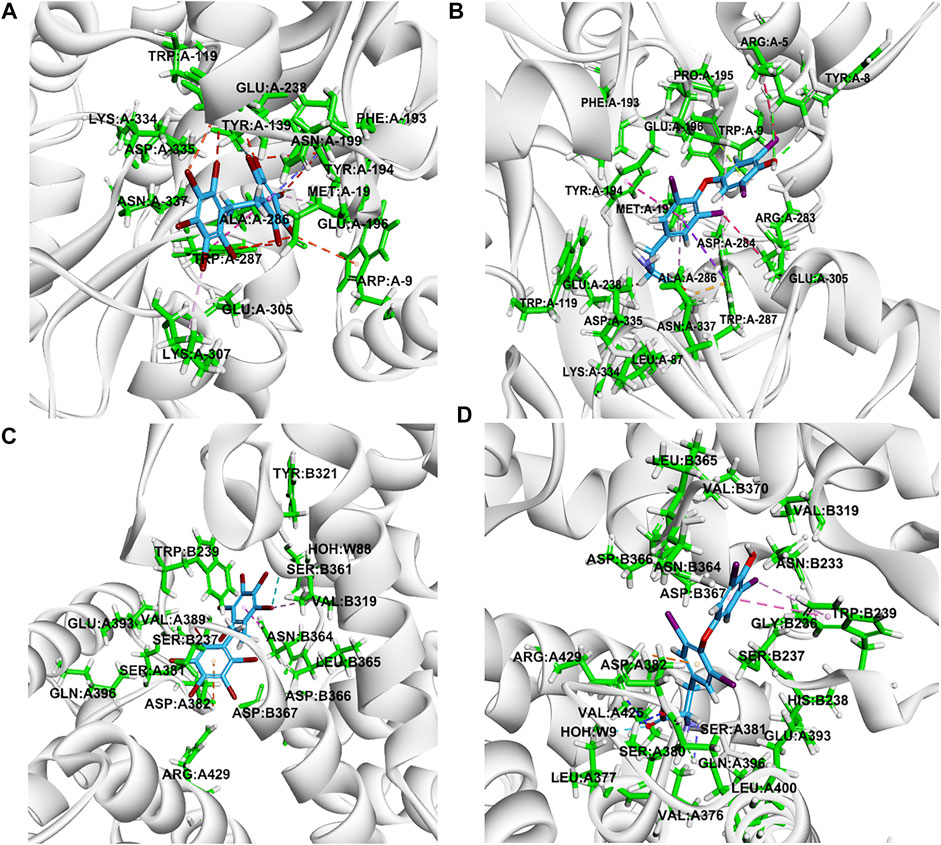

3.3.5 Molecular Docking Results

Molecular docking was performed to study the binding ability of DBDPE and identify possible target genes and proteins. According to the docking results, DBDPE can bind to the cavities of CRHR1 and TRβ, and its mode of interaction is similar to that of T4 (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure S2). But DBDPE failed to dock with thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR), transthyretin (TTR), or deiodinase (DIOs) (data not shown). The binding energies of the most optimal binding conformations were −41.36 kcal/mol for binding between DBDPE and CRHR1 and −48.86 kcal/mol for binding between DBDPE and TRβ (Supplementary Table S2).

FIGURE 5. 3D representations of the interactions of DBDPE with corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1 (CRHR1) (A) and thyroid hormone receptor beta (TRβ) (C). 3D representations of the interactions of T4 with CRHR1 (B) and TRβ (D). The dashed lines represent the interactions between the ligand (DBDPE or T4) and the target proteins.

4 Discussion

Novel brominated flame retardants exist widely in the environment alongside many other pollutants, which may alter their environmental behavior, bioavailability, and biotoxicity in organisms (Zheng et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2020b; Ratshiedana et al., 2021). In the present study, we evaluated the effects of n-TiO2 on the properties of DBDPE in aqueous solution, including the accumulation, metabolism, and potential toxicity of DBDPE in zebrafish embryos/larvae. The results indicate altered existence in water phase, altered contents and composition of metabolites in zebrafish larvae, and also altered toxicity of DBDPE in zebrafish larvae in the presence of n-TiO2. At environmental relevant level, short term exposure to DBDPE did not cause obvious toxicity in zebrafish, either alone or in the presence of n-TiO2, suggesting that DBDPE pollution may not pose acute risk to the wild fish species at present. However, the observed changes at higher concentrations indicated potential risks by aggravated pollution, and the behavior, toxicity and risks of DBDPE upon long-term exposure, especially in the presence of nanoparticles still need further evaluation.

4.1 DBDPE Was Adsorbed by n-TiO2 in Aqueous Solution

We first evaluated whether DBDPE could be adsorbed to n-TiO2 by determining the diameters and zeta potentials of 100 μg/L n-TiO2 in aqueous solution. The size distribution of n-TiO2 revealed an increase in nanoparticle size with increasing DBDPE concentration (1, 10, 100 μg/L). Similarly, an increase in n-TiO2 size was observed in the presence of BDE-209, which may be attributed to the coating of the nanoparticles by the organic pollutants (Wang et al., 2018). In addition, the zeta potential of n-TiO2 increased (became more negative) as the concentration of DBDPE increased. This indicates that the surface charge of n-TiO2 shifted toward that of DBDPE, leading to increased colloidal stability in the aqueous solution. According to previous studies, this shift in surface charge indicates the adsorption of DBDPE by n-TiO2, likely through electrostatic forces (Wang et al., 2018). The co-existence of n-TiO2 also led to a time-dependent decrease in the content of DBDPE in the aqueous phase, suggesting sedimentation due to the increased nanoparticle size. Basing on these results, we hypothesized that DBDPE can be adsorbed by n-TiO2 and deposited from the aqueous phase.

4.2 n-TiO2 Affected the Bioaccumulation and Biotransformation of DBDPE in Zebrafish Larvae

Due to their surface properties, nanoparticles can adsorb organic and inorganic pollutants, resulting in changes in pollutant bioavailability (Wang et al., 2014; Josko et al., 2021; Ratshiedana et al., 2021). For example, n-TiO2 enhanced the bioaccumulation of bisphenol A in zebrafish (Fang et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2019), while nano-SiO2 promoted the uptake of tetrabromobisphenol A in zebrafish larvae (Zhu et al., 2021). Accordingly, we studied the accumulation of DBDPE (1, 10, and 100 μg/L) in zebrafish larvae in the presence of n-TiO2 (100 μg/L). The accumulation of DBDPE in zebrafish larvae exposed only to DBDPE increased in a dose-dependent manner, and the co-existence of n-TiO2 enhanced the accumulation of DBDPE. Considering that the uptake of n-TiO2 in zebrafish larvae was also increased by the presence of DBDPE, we hypothesized that the adsorption of DBDPE on n-TiO2 facilitated the uptake of the combined nanoparticles, thereby increasing the bioavailability of both species.

To reveal the effects of n-TiO2 on the biotransformation of DBDPE, we analyzed the metabolites of DBDPE in zebrafish larvae exposed to 10 μg/L DBDPE alone or in combination with n-TiO2. In general, the chromatograms indicated similar metabolites in zebrafish larvae after DBDPE exposure with and without n-TiO2. At least 14 peaks were identified as possible metabolites of DBDPE, including three nona-BDPE, two nona-brominated, four octa-BDPE, and five hepta-BDPE products. Previous studies revealed seven metabolites of DBDPE in rats (Wang et al., 2010) and zebrafish (Wang X. et al., 2019). Jiang et al. (2021) reported three nona-BDPE, four nona-brominated, three octa-BDPE, and four hepta-BDPE products in earthworms, similar to our results. However, the proportions of different metabolite types varied between the group exposed to 10 μg/L DBDPE and the group co-exposed to 10 μg/L DBDPE + n-TiO2, indicating a possibility that the presence of n-TiO2 could affect the metabolism of DBDPE.

4.3 n-TiO2 Enhanced DBDPE-Induced Toxicity in Zebrafish Larvae

We also conducted experiments to determine whether the presence of n-TiO2 can alter DBDEP-induced toxicity using zebrafish embryos/larvae as a model. The basic developmental parameters of zebrafish larvae (hatching rate, malformation rate, survival rate, and body weight) were not significantly changed upon DBDPE exposure, either alone or in combination with n-TiO2. Consistently, no obvious developmental toxicity was observed when zebrafish larvae were exposed to a higher concentration of DBDPE (291.36 μg/L) (Wang X. et al., 2019). These results confirm the low acute toxicity of DBDPE in early-stage zebrafish. Similarly, co-exposure to DBDPE and n-TiO2 did not lead to obvious acute toxicity. However, the heart rates of zebrafish embryos at 48 hpf were significantly increased by DBDPE single exposure at 10 and 100 μg/L compared to the control, and the heart rates were further increased upon co-exposure with n-TiO2. But no significant difference of the heart rates was observed when zebrafish embryos exposed to 1 μg/L DBDPE compared to the control. Jing et al. (2019) reported that oral exposure to 500 mg/kg bw/day DBDPE led to morphological and ultrastructural damage in the hearts of male rats, suggesting that DBDPE may have cardiotoxicity in organisms. Our results indicated that DBDPE did not obviously change the heart rates of zebrafish at environmental relevant concentrations. Exposure to higher concentrations of DBDPE may induce cardiotoxicity, and this could be further enhanced by the presence of n-TiO2.

In the present study, single exposure to DBDPE induced hyperactivity in zebrafish embryos/larvae, as characterized by increased frequency of tail bending at 24 hpf and increased free swimming speed under continuous light and dark/light stimulation at 144 hpf. This may be explained by increases in the contents of neurotransmitters such as GABA, Ach, Ch, and NE at 10 μg/L DBDPE exposure group, which play important roles in behavior (Tufi et al., 2016; Shi Q. et al., 2018; JavadiEsfahani and Kwong, 2019). The presence of n-TiO2 enhanced the increase in tail bending frequencies and average speed during the first dark stimulation cycle and promoted the transcriptional levels of syn2a and α1-tubulin, while it had no effect on their protein levels. In contrast, co-exposure with n-TiO2 diminished the increases in the levels of the abovementioned neurotransmitters and significantly decreased the DA content. These results demonstrate that n-TiO2 can enhance the neurotoxicity of DBDPE and change the zebrafish response to DBDPE in solution.

Previous studies have indicated that the neurotoxicity of brominated flame retardants (BFRs) can be at least partially attributed to their disruption of thyroid hormones due to the structural similarity between BFR and hormone molecules (Kitamura et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2014). DBDPE has been shown to affect thyroid hormones in both fish and rats (Sun et al., 2018; Wang X. et al., 2019; Wang Y. et al., 2019). In the present study, we observed significant increases in the tT4 and increasing trends in the tT3 in zebrafish larvae upon single exposure to 100 μg/L DBDPE. What’s more, a further increase of the tT4 was observed at 1 μg/L DBDPE +100 μg/L n-TiO2 exposure group compared to 1 μg/L DBDPE group. These effects may be attributed to the increased transcription levels of genes involved in TH synthesis, including crh and tshβ (Lee et al., 2016; Walter et al., 2019). The presence of n-TiO2 enhanced the DBDPE-induced increases in tT4 and tT3 along with the transcription levels of tshβ and trβ, whereas it significantly inhibited the transcription of crhr1. Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) and its receptors (CRHR1 and CRHR2) have a wide range of functions related to endocrine regulation and behavioral responses to environmental stressors (Timpl et al., 1998). The blocking of CRHR1 reduces CRH-induced release of neurotransmitters such as epinephrine and dopamine in Sprague–Dawley rats (Jezova et al., 1999). Therefore, the inhibited transcription of crhr1 may be at least partially related to the reduction in the increased neurotransmitter levels caused by the presence of n-TiO2. As indicated by the molecular docking results in the present study, DBDPE can interact with CRHR1 and TRβ, and the interaction strength is higher for DBDPE compared to BDE-209. Our molecular docking results also indicate that DBDPE fails to dock with thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR), transthyretin (TTR), or deiodinase (DIOs) (data not shown). Thus, we hypothesized that CRHR1 and TRβ might be potential targets of DBDPE; the presence of n-TiO2 enhanced the DBDPE-induced promotion of TH synthesis and activated negative feedback by inhibiting the transcription of crhr1.

5 Conclusion

In summary, based on the increases in nanoparticle size and zeta potential of n-TiO2 with increasing DBDPE concentration, DBDPE can be adsorbed by n-TiO2, which may lead to its sedimentation from the aqueous phase. Co-exposure with n-TiO2 promoted the uptake of DBDPE and altered the composition of DBDPE metabolites detected in zebrafish larvae, suggesting that the presence of n-TiO2 affected the bioavailability and biotransformation of DBDPE. Consequently, co-exposure with n-TiO2 enhanced DBDPE-induced toxicity, as indicated by further increases in heart rate, spontaneous movement, free swimming speed under dark/light stimulation, and thyroid hormone disruption in zebrafish embryos/larvae compared to single DBDPE exposure. The presence of n-TiO2 also enhanced the DBDPE-induced promotion of TH synthesis, activated the trβ regulated pathways and triggered negative feedback by inhibiting the transcription of crhr1. Overall, our results demonstrate that the environmental behavior, bioavailability, biotransformation, and biotoxicity of DBDPE were affected by the presence of n-TiO2 when exposed to higher concentrations of DBDPE than environmental relevant concentration.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author Contributions

XW: Exposure, Sampling, Methodology, Writing; YS: Sampling, Methodology (chemical analysis); MF: Methodology (chemical analysis); PC: Methodology (dynamic light scattering); QW: Methodology (Molecular docking); JH: Data Analysis, Review; KF: Sampling; WZ: Methodology (chemical analysis); LFZ: Review; LY: Conceptualization, Writing, Review; BZ: Funding acquisition, Review.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 21976207, 22006035), the State Key Laboratory of Freshwater Ecology and Biotechnology (grant number 2019FBZ03), and Beijing municipal youth top-notch talent program (2018000021223ZK34). The funds for open access publication fees was from the library of Environmental Toxicity, Institute of Hydrobiology, CAS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Analysis and Testing Center of Institute of Hydrobiology for assistance in chemical analysis.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.860786/full#supplementary-material

References

Chen, T., Huang, M., Li, J., Li, J., and Shi, Z. (2019). Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers and Novel Brominated Flame Retardants in Human Milk from the General Population in Beijing, China: Occurrence, Temporal Trends, Nursing Infants' Exposure and Risk Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 689, 278–286. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.442

Chen, X., Dong, Q., Chen, Y., Zhang, Z., Huang, C., Zhu, Y., et al. (2017). Effects of Dechlorane Plus Exposure on Axonal Growth, Musculature and Motor Behavior in Embryo-Larval Zebrafish. Environ. Pollut. 224, 7–15. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.03.011

Covaci, A., Harrad, S., Abdallah, M. A.-E., Ali, N., Law, R. J., Herzke, D., et al. (2011). Novel Brominated Flame Retardants: a Review of Their Analysis, Environmental Fate and Behaviour. Environ. Int. 37, 532–556. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2010.11.007

Egloff, C., Crump, D., Chiu, S., Manning, G., McLaren, K. K., Cassone, C. G., et al. (2011). In Vitro and in Ovo Effects of Four Brominated Flame Retardants on Toxicity and Hepatic mRNA Expression in Chicken Embryos. Toxicol. Lett. 207, 25–33. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.08.015

Fang, Q., Shi, Q., Guo, Y., Hua, J., Wang, X., and Zhou, B. (2016). Enhanced Bioconcentration of Bisphenol A in the Presence of Nano-TiO2 Can Lead to Adverse Reproductive Outcomes in Zebrafish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 1005–1013. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b05024

Garner, K. L., Suh, S., and Keller, A. A. (2017). Assessing the Risk of Engineered Nanomaterials in the Environment: Development and Application of the nanoFate Model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 5541–5551. doi:10.1021/acs.est.6b05279

González, R. R., Fernández, R. F., Vidal, J. L. M., Frenich, A. G., and Pérez, M. L. G. (2011). Development and Validation of an Ultra-high Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass-Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) Method for the Simultaneous Determination of Neurotransmitters in Rat Brain Samples. J. Neurosci. Methods 198, 187–194. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.03.023

Guo, Y., Chen, L., Wu, J., Hua, J., Yang, L., Wang, Q., et al. (2019). Parental Co-exposure to Bisphenol A and Nano-TiO2 Causes Thyroid Endocrine Disruption and Developmental Neurotoxicity in Zebrafish Offspring. Sci. Total Environ. 650, 557–565. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.007

Hardy, M. L., Krueger, H. O., Blankinship, A. S., Thomas, S., Kendall, T. Z., and Desjardins, D. (2012). Studies and Evaluation of the Potential Toxicity of Decabromodiphenyl Ethane to Five Aquatic and Sediment Organisms. Ecotoxicology Environ. Saf. 75, 73–79. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.08.005

Harrad, S., Drage, D. S., Sharkey, M., and Berresheim, H. (2020). Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Brominated Flame Retardants in Landfill-Related Air, Soil, and Groundwater from Ireland. Sci. Total Environ. 705, 135834. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135834

JavadiEsfahani, R., and Kwong, R. W. M. (2019). The Sensory-Motor Responses to Environmental Acidosis in Larval Zebrafish: Influences of Neurotransmitter and Water Chemistry. Chemosphere 235, 383–390. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.06.133

Jezova, D., Ochedalski, T., Glickman, M., Kiss, A., and Aguilera, G. (1999). Central Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptors Modulate Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical and Sympathoadrenal Activity during Stress. Neuroscience 94, 797–802. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00333-4

Jiang, L., Ling, S., Fu, M., Peng, C., Zhang, W., Lin, K., et al. (2021). Bioaccumulation, Elimination and Metabolism in Earthworms and Microbial Indices Responses after Exposure to Decabromodiphenyl Ethane in a Soil-Earthworm-Microbe System. Environ. Pollut. 289, 117965. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117965

Jin, M.-q., Zhang, D., Zhang, Y., Zhou, S.-s., Lu, X.-t., and Zhao, H.-t. (2018). Neurological Responses of Embryo-Larval Zebrafish to Short-Term Sediment Exposure to Decabromodiphenylethane. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 19, 400–408. doi:10.1631/jzus.b1800033

Jing, L., Sun, Y., Wang, Y., Liang, B., Chen, T., Zheng, D., et al. (2019). Cardiovascular Toxicity of Decabrominated Diphenyl Ethers (BDE-209) and Decabromodiphenyl Ethane (DBDPE) in Rats. Chemosphere 223, 675–685. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.02.115

Josko, I., Kusiak, M., Oleszczuk, P., Swieca, M., Konczak, M., and Sikora, M. (2021). Transcriptional and Biochemical Response of Barley to Co-exposure of Metal-Based Nanoparticles. Sci. Total. Environ. 782.

Kaegi, R., Englert, A., Gondikas, A., Sinnet, B., von der Kammer, F., and Burkhardt, M. (2017). Release of TiO 2 - (Nano) Particles from Construction and Demolition Landfills. Nanoimpact 8, 73–79. doi:10.1016/j.impact.2017.07.004

Kitamura, S., Shinohara, S., Iwase, E., Sugihara, K., Uramaru, N., Shigematsu, H., et al. (2008). Affinity for Thyroid Hormone and Estrogen Receptors of Hydroxylated Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers. J. Health Sci. 54, 607–614. doi:10.1248/jhs.54.607

Labille, J., Slomberg, D., Catalano, R., Robert, S., Apers-Tremelo, M.-L., Boudenne, J.-L., et al. (2020). Assessing UV Filter Inputs into beach Waters during Recreational Activity: A Field Study of Three French Mediterranean Beaches from Consumer Survey to Water Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 706, 136010. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136010

Lee, D., Ahn, C., Hong, E.-J., An, B.-S., Hyun, S.-H., Choi, K.-C., et al. (2016). 2,4,6-Tribromophenol Interferes with the Thyroid Hormone System by Regulating Thyroid Hormones and the Responsible Genes in Mice. Ijerph 13 (7), 697. doi:10.3390/ijerph13070697

Liu, L., Zhen, X., Wang, X., Li, Y., Sun, X., and Tang, J. (2020). Legacy and Novel Halogenated Flame Retardants in Seawater and Atmosphere of the Bohai Sea: Spatial Trends, Seasonal Variations, and Influencing Factors. Water Res. 184, 116117. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2020.116117

Liu, Y., Nie, Y., Wang, J., Wang, J., Wang, X., Chen, S., et al. (2018). Mechanisms Involved in the Impact of Engineered Nanomaterials on the Joint Toxicity with Environmental Pollutants. Ecotoxicology Environ. Saf. 162, 92–102. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.06.079

Luo, Z., Li, Z., Xie, Z., Sokolova, I. M., Song, L., Peijnenburg, W. J. G. M., et al. (2020). Rethinking Nano-TiO2 Safety: Overview of Toxic Effects in Humans and Aquatic Animals. Small 16, e2002019. doi:10.1002/smll.202002019

Pradas del Real, A. E., Castillo-Michel, H., Kaegi, R., Larue, C., de Nolf, W., Reyes-Herrera, J., et al. (2018). Searching for Relevant Criteria to Distinguish Natural vs. Anthropogenic TiO2 Nanoparticles in Soils. Environ. Sci. Nano 5, 2853–2863. doi:10.1039/c8en00386f

Ratshiedana, R., Kuvarega, A. T., and Mishra, A. K. (2021). Titanium Dioxide and Graphitic Carbon Nitride-Based Nanocomposites and Nanofibres for the Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Water: a Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 10357–10374. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-11987-3

Rauert, C., Schuster, J. K., Eng, A., and Harner, T. (2018). Global Atmospheric Concentrations of Brominated and Chlorinated Flame Retardants and Organophosphate Esters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2777–2789. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b06239

Shi, Q., Wang, M., Shi, F., Yang, L., Guo, Y., Feng, C., et al. (2018a). Developmental Neurotoxicity of Triphenyl Phosphate in Zebrafish Larvae. Aquat. Toxicol. 203, 80–87. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2018.08.001

Shi, X., Li, Z., Chen, W., Qiang, L., Xia, J., Chen, M., et al. (2016). Fate of TiO2 Nanoparticles Entering Sewage Treatment Plants and Bioaccumulation in Fish in the Receiving Streams. Nanoimpact 3-4, 96–103. doi:10.1016/j.impact.2016.09.002

Shi, Z., Zhang, L., Li, J., and Wu, Y. (2018b). Legacy and Emerging Brominated Flame Retardants in China: A Review on Food and Human Milk Contamination, Human Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment. Chemosphere 198, 522–536. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.01.161

Sun, R. B., Shang, S., Zhang, W., Lin, B. C., Wang, Q., Shi, Y., et al. (2018). Endocrine Disruption Activity of 30-day Dietary Exposure to Decabromodiphenyl Ethane in Balb/C Mouse. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 31, 12–22. doi:10.3967/bes2018.002

Tao, L., Zhang, Y., Wu, J.-P., Wu, S.-K., Liu, Y., Zeng, Y.-H., et al. (2019). Biomagnification of PBDEs and Alternative Brominated Flame Retardants in a Predatory Fish: Using Fatty Acid Signature as a Primer. Environ. Int. 127, 226–232. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2019.03.036

Timpl, P., Spanagel, R., Sillaber, I., Kresse, A., Reul, J. M. H. M., Stalla, G. K., et al. (1998). Impaired Stress Response and Reduced Anxiety in Mice Lacking a Functional Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor 1. Nat. Genet. 19, 162–166. doi:10.1038/520

Tufi, S., Leonards, P., Lamoree, M., de Boer, J., Legler, J., and Legradi, J. (2016). Changes in Neurotransmitter Profiles during Early Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Development and after Pesticide Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 3222–3230. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b05665

Walter, K. M., Miller, G. W., Chen, X., Yaghoobi, B., Puschner, B., and Lein, P. J. (2019). Effects of Thyroid Hormone Disruption on the Ontogenetic Expression of Thyroid Hormone Signaling Genes in Developing Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 272, 20–32. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2018.11.007

Wang, F., Wang, J., Dai, J., Hu, G., Wang, J., Luo, X., et al. (2010). Comparative Tissue Distribution, Biotransformation and Associated Biological Effects by Decabromodiphenyl Ethane and Decabrominated Diphenyl Ether in Male Rats after a 90-Day Oral Exposure Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 5655–5660. doi:10.1021/es101158e

Wang, Q., Chen, Q., Zhou, P., Li, W., Wang, J., Huang, C., et al. (2014). Bioconcentration and Metabolism of BDE-209 in the Presence of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles and Impact on the Thyroid Endocrine System and Neuronal Development in Zebrafish Larvae. Nanotoxicology 8 Suppl 1 (S1), 196–207. doi:10.3109/17435390.2013.875232

Wang, X., Adeleye, A. S., Wang, H., Zhang, M., Liu, M., Wang, Y., et al. (2018). Interactions between Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) and TiO2 Nanoparticle in Artificial and Natural Waters. Water Res. 146, 98–108. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2018.09.019

Wang, X., Ling, S., Guan, K., Luo, X., Chen, L., Han, J., et al. (2019a). Bioconcentration, Biotransformation, and Thyroid Endocrine Disruption of Decabromodiphenyl Ethane (Dbdpe), A Novel Brominated Flame Retardant, in Zebrafish Larvae. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 8437–8446. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b02831

Wang, Y., Chen, T., Sun, Y., Zhao, X., Zheng, D., Jing, L., et al. (2019b). A Comparison of the Thyroid Disruption Induced by Decabrominated Diphenyl Ethers (BDE-209) and Decabromodiphenyl Ethane (DBDPE) in Rats. Ecotoxicology Environ. Saf. 174, 224–235. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.02.080

Wemken, N., Drage, D. S., Abdallah, M. A.-E., Harrad, S., and Coggins, M. A. (2019). Concentrations of Brominated Flame Retardants in Indoor Air and Dust from Ireland Reveal Elevated Exposure to Decabromodiphenyl Ethane. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 9826–9836. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b02059

Wu, J.-P., Wu, S.-K., Tao, L., She, Y.-Z., Chen, X.-Y., Feng, W.-L., et al. (2020a). Bioaccumulation Characteristics of PBDEs and Alternative Brominated Flame Retardants in a Wild Frog-Eating Snake. Environ. Pollut. 258, 113661. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113661

Wu, S., Zhang, S., Gong, Y., Shi, L., and Zhou, B. (2020b). Identification and Quantification of Titanium Nanoparticles in Surface Water: A Case Study in Lake Taihu, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 382, 121045. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121045

Xiong, P., Yan, X., Zhu, Q., Qu, G., Shi, J., Liao, C., et al. (2019). A Review of Environmental Occurrence, Fate, and Toxicity of Novel Brominated Flame Retardants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 13551–13569. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b03159

Yu, L., Deng, J., Shi, X., Liu, C., Yu, K., and Zhou, B. (2010). Exposure to DE-71 Alters Thyroid Hormone Levels and Gene Transcription in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid axis of Zebrafish Larvae. Aquat. Toxicol. 97, 226–233. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.10.022

Yu, L., Lam, J. C. W., Guo, Y., Wu, R. S. S., Lam, P. K. S., and Zhou, B. (2011). Parental Transfer of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) and Thyroid Endocrine Disruption in Zebrafish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 10652–10659. doi:10.1021/es2026592

Zeng, Y. H., Luo, X. J., Sun, Y. X., Yu, L. H., Chen, S. J., and Mai, B. X. (2011). Concentration and Emission Fluxes of Halogenated Flame Retardants in Sewage from Sewage Outlet in Dongjiang River. Huan Jing Ke Xue 32, 2891. doi:10.13227/j.hjkx.2011.10.042

Zhen, X., Tang, J., Liu, L., Wang, X., Li, Y., and Xie, Z. (2018). From Headwaters to Estuary: Distribution and Fate of Halogenated Flame Retardants (HFRs) in a River basin Near the Largest HFR Manufacturing Base in China. Sci. Total Environ. 621, 1370–1377. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.091

Zheng, G., Wan, Y., Shi, S., Zhao, H., Gao, S., Zhang, S., et al. (2018). Trophodynamics of Emerging Brominated Flame Retardants in the Aquatic Food Web of Lake Taihu: Relationship with Organism Metabolism across Trophic Levels. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 4632–4640. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b06588

Zhu, B., Han, J., Lei, L., Hua, J., Zuo, Y., and Zhou, B. (2021). Effects of SiO2 Nanoparticles on the Uptake of Tetrabromobisphenol A and its Impact on the Thyroid Endocrine System in Zebrafish Larvae. Ecotoxicology Environ. Saf. 209, 111845. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111845

Keywords: DBDPE, N-TiO2, bioavailability, thyroid disruption, developmental neurotoxicity, zebrafish larvae

Citation: Wang X, Sun Y, Fu M, Chen P, Wang Q, Hua J, Fu K, Zhang W, Zhu L, Yang L and Zhou B (2022) Nano-TiO2 Adsorbed Decabromodiphenyl Ethane and Changed Its Bioavailability, Biotransformation and Biotoxicity in Zebrafish Embryos/Larvae. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:860786. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.860786

Received: 23 January 2022; Accepted: 24 February 2022;

Published: 14 March 2022.

Edited by:

Chenglian Feng, Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences, ChinaReviewed by:

Liwei Sun, Zhejiang University of Technology, ChinaMarkus Hecker, University of Saskatchewan, Canada

Copyright © 2022 Wang, Sun, Fu, Chen, Wang, Hua, Fu, Zhang, Zhu, Yang and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lihua Yang, bGh5YW5nQGloYi5hYy5jbg==

Xiulin Wang

Xiulin Wang Yumiao Sun

Yumiao Sun Mengru Fu3

Mengru Fu3 Lifei Zhu

Lifei Zhu Lihua Yang

Lihua Yang