95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 07 March 2022

Sec. Soil Processes

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.834371

Draining peatlands for forestry in the northern hemisphere turns their soils from carbon sinks to substantial sources of greenhouse gases (GHGs). To reverse this trend, rewetting has been proposed as a climate change mitigation strategy. We performed a literature review to assess the empirical evidence supporting the hypothesis that rewetting drained forested peatlands can turn them back into carbon sinks. We also used causal loop diagrams (CLDs) to synthesize the current knowledge of how water table management affects GHG emissions in organic soils. We found an increasing number of studies from the last decade comparing GHG emissions from rewetted, previously forested peatlands, with forested or pristine peatlands. However, comparative field studies usually report relatively short time series following rewetting experiments (e.g., 3 years of measurements and around 10 years after rewetting). Empirical evidence shows that rewetting leads to lower GHG emissions from soils. However, reports of carbon sinks in rewetted systems are scarce in the reviewed literature. Moreover, CH4 emissions in rewetted peatlands are commonly reported to be higher than in pristine peatlands. Long-term water table changes associated with rewetting lead to a cascade of effects in different processes regulating GHG emissions. The water table level affects litterfall quantity and quality by altering the plant community; it also affects organic matter breakdown rates, carbon and nitrogen mineralization pathways and rates, as well as gas transport mechanisms. Finally, we conceptualized three phases of restoration following the rewetting of previously drained and forested peatlands, we described the time dependent responses of soil, vegetation and GHG emissions to rewetting, concluding that while short-term gains in the GHG balance can be minimal, the long-term potential of restoring drained peatlands through rewetting remains promising.

Organic soils, such as peatlands, cover 3% of the terrestrial land area, but store 30% of the total soil carbon (FAO, 2020). Northern peatlands cover 3.7 million km2, including 1.7 million km2 in permafrost, and store around 530 PgC, making them an important component in the global carbon cycle (Tanneberger et al., 2017; Hugelius et al., 2020).

Peatlands are characterized by organic matter accumulation when water saturation leads to anoxic conditions in the soil (Bragazza et al., 2009; Leifeld et al., 2019; Conchedda and Tubiello, 2020). However, these ecosystems have been systematically drained for agriculture, forestry and peat extraction for fuel (Laine et al., 2009; Montanarella et al., 2006). To date, 30% of the peatlands located in Nordic and Baltic countries have been drained and are being used for commercial forestry (Laine et al., 2009). Draining organic soils creates aerobic conditions that promote the decomposition of soil organic matter, leading to CO2 (Kasimir et al., 2018) and, in nutrient rich sites, N2O emissions (Klemedtsson et al., 2005).

Forestry, commonly perceived as climate friendly thanks to its carbon storage potential, can become an important source of greenhouse gases (GHGs) when associated with peatland drainage (Arnold et al., 2005). The positive climate effect of lower CH4 emissions and higher CO2 uptake, due to better conditions for forest production (Korkiakoski et al., 2019) can be offset by CO2 and N2O emissions from the drained soil (Ojanen et al., 2010; Lohila et al., 2011; Kasimir et al., 2018).

Increasing water table through ditch blocking to restore anoxic conditions has been proposed as an alternative to reduce GHG emissions from forested and drained peatlands (Martens et al., 2021). Rewetting drained peatlands could have positive effects in countries with extensive areas in drained forested peatlands, such as United Kingdom, Ireland, Estonia, Sweden, Norway and Finland (Kløve et al., 2017; Tanneberger et al., 2017). However, the effect of rewetting on GHG emissions depends on the restoration of peat forming plant and microbial communities and stabilization of hydrological conditions, which might require several years. Moreover, the net effect of rewetting drained and forested peatlands on global warming is still a matter of debate (Tanneberger et al., 2017; Ojanen and Minkkinen, 2020).

Measuring GHG fluxes in the field is technically and logistically difficult, which limits the collection of empirical evidence (Jauhiainen et al., 2019). Additionally, GHG fluxes are highly dynamic due to several interacting controlling factors such as soil temperature, soil moisture, nutrient availability, soil physical properties, plant community, microbial community, soil organic matter quality, among others (Bragazza et al., 2009; Jauhiainen et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2021). Moreover, the definition of the system boundary determines which fluxes are considered, thereby affecting the estimated net GHG balance (Chapin et al., 2006).

These difficulties hinder our understanding of how peatland management can help climate change mitigation and motivate this contribution. In this paper, we aim to answer the following questions:

1. Is there empirical evidence that rewetting decreases net GHG emissions of drained and forested peatlands?

2. What processes control the response of GHG fluxes to rewetting on drained and forested peatlands?

3. Based on empirical evidence and process understanding, what is the expected effect of rewetting forested peatlands on GHG fluxes over time?

We focused on GHG fluxes from forested and drained peatlands and wet peatlands. For wet peatlands we focused on rewetted previously drained and forested peatlands as well as pristine peatlands. We defined GHG fluxes as the vertical transport of N2O, CH4 and CO2 between the atmosphere and the soil-vegetation continuum during a specific time interval in a specific area characterized by forested and drained or wet peat soils. We considered GHG fluxes from ditches and CO2 fluxes from all the vegetation as part of the system GHG fluxes. Deviations of measured GHG fluxes from this definition are indicated.

To address the first question, we performed a systematic literature search focusing on GHG fluxes from rewetted peatlands that were previously drained and forested. The literature search was performed on Web of Science in October 2021, using the following string: (“organic soil*” OR “peatland*” OR “histosol*”) AND (“forest*” OR “forestry” OR “forested” OR “afforested” OR “deciduous” OR “coniferous”) AND (“drained” OR “drainage”) AND (“restored” OR “restoration” OR “rewetting” OR “rewetted”) AND (“greenhouse gases” OR “GHG” OR “fluxes” OR “emissions” OR “uptake” OR “removals” OR “soil emission*” OR “CO2” OR “carbon dioxide” OR “CH4” OR “methane” OR ″N2O″ OR “nitrous oxide”). In addition, we considered relevant articles cited in those found from the systematic search.

The search returned 121 papers, of these we retained 18 articles based on the following criteria:

• Organic soils reported had more than 12% of organic content and more than 10 cm of peat.

• Drained peatlands under study were forested.

• Rewetted peatlands under study were previously drained and forested.

• Pristine peatlands under study were not managed ecosystems and had vegetation typical of water saturated peatlands.

• Soil GHG fluxes were compared between rewetted and pristine or drained peatlands

• Peatlands under study were located in boreal or temperate climate zones.

• GHG values were obtained through field measurements or meta-analysis of relevant literature (model results are excluded).

We reported statistically significant differences in GHG fluxes for studies empirically comparing the systems of interest (drained forested, pristine, and rewetted previously drained and forested). Emissions factors derived from meta-analysis in review papers are also reported.

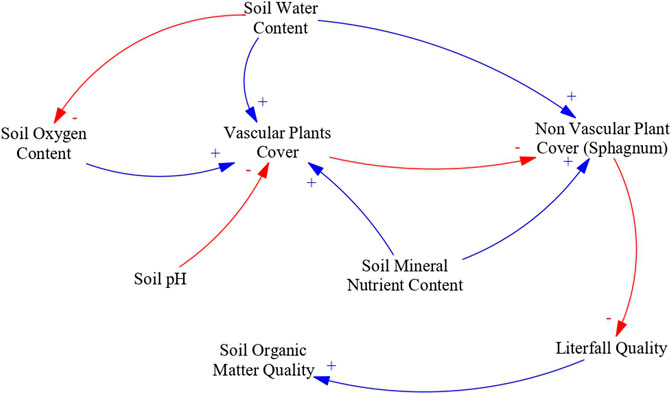

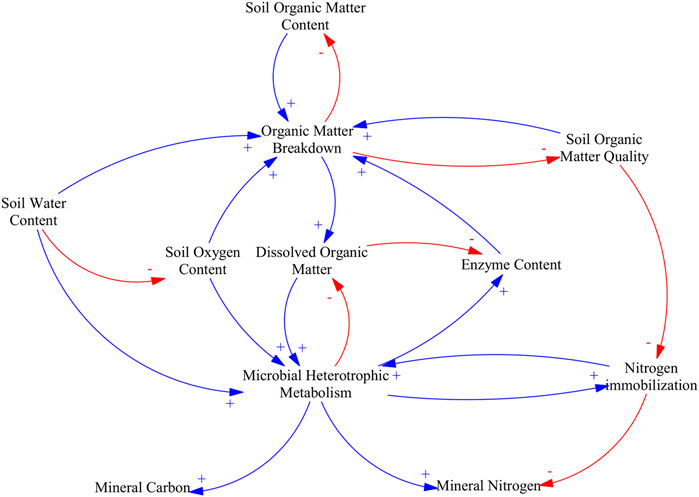

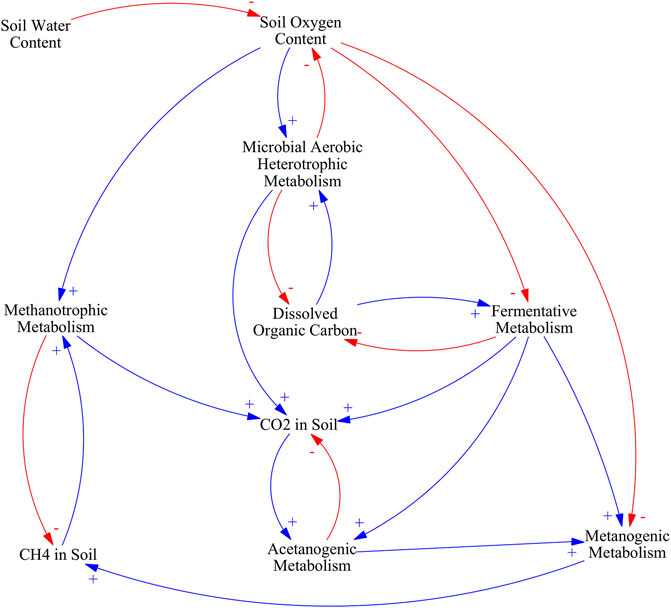

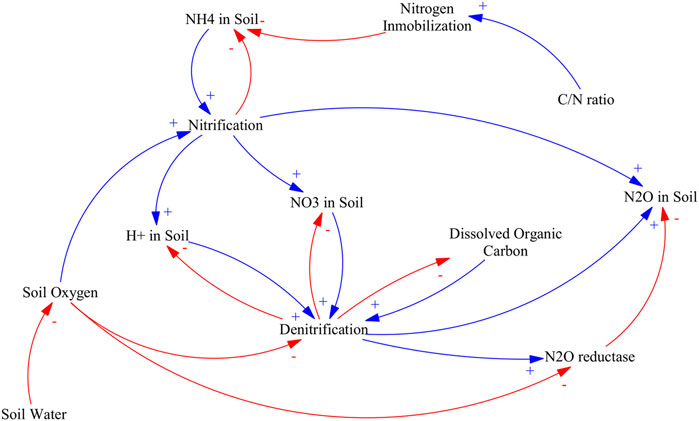

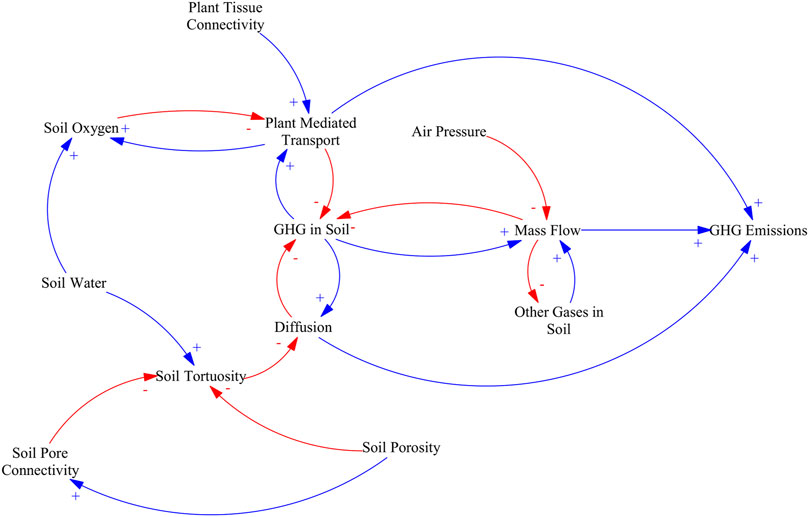

The second question was addressed by a non-systematic literature review. Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) were constructed to describe how controlling factors identified affect GHG dynamics in peatlands. A CLD presents the causal relations between the state variables in a system, and how changes in the driving factors propagate throughout the system (Anderson and Johnson, 1997). In the CLD, an arrow with a plus sign indicates a change in the variable affected that is in the same direction of the change in the driving variable, and an arrow with a minus sign indicates a change in variable affected that is in the opposite direction of the change in the driving variable (Wallman et al., 2006). By following these arrows through the system, reinforcing and balancing feedbacks can be revealed (Wallman et al., 2006). CLD’s are useful to differentiate direct and indirect causalities and explore complex systems such as peatlands.

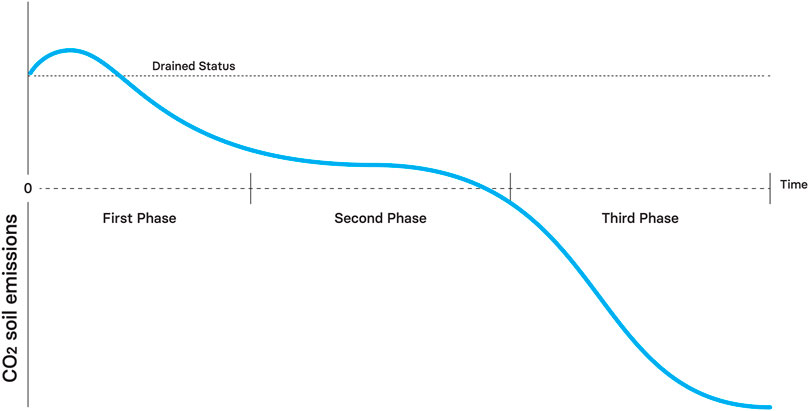

For the third question, we hypothesized time dependent effects of rewetting on GHG fluxes by dividing the restoration process in three phases. We used empirical data collected for the first question, process understanding derived from the second question, and relevant scientific literature to characterize the three restoration phases.

We identified 18 studies comparing empirical GHG emissions data from rewetted peatlands that were previously drained and forested with still forested and drained peatlands or pristine peatlands. The studies were published mostly after 2012. Of these, 12 studies performed GHG measurements using different variations of the chamber method (Komulainen et al., 1998, 1999; Juottonen et al., 2012; Bohdálková et al., 2013; Urbanová et al., 2013; Koskinen et al., 2016; Hambley et al., 2019; Laine et al., 2019; Purre et al., 2019; Creevy et al., 2020; Jurasinski et al., 2020; Minkkinen et al., 2020), three studies reported eddy covariance measurements (Petrone et al., 2001; Hambley et al., 2019; Purre et al., 2019), one study estimated emissions with chemical tracers and soil and water samples (Tauchnitz et al., 2015) and four studies conducted a meta-analysis of relevant empirical data (Wilson et al., 2016; Evans et al., 2017; Juutinen et al., 2020; Tiemeyer et al., 2020).

Only two of the field based studies reported data from a site before and after restoration (Komulainen et al., 1998, 1999). Instead, most field studies used space for time substitutions by contrasting drained, rewetted and pristine sites at the same time. Yet, reported observations remain short term, with usually less than 3 years of reported data and an average time of restoration before the first measurement of 10 years.

While the reviewed studies remain few, they show that rewetting of drained forested peatlands can reduce soil GHG emissions, and in certain cases even revert them to net carbon sinks. Below we summarize the reviewed findings according to the following categories:

1. GHG emissions comparison between drained and rewetted systems by GHG type

2. GHG emissions comparison between rewetted and pristine systems by GHG type

3. Net GHG emissions of drained, rewetted and pristine ecosystems.

Rewetted peatlands often exhibited lower heterotrophic or ecosystem respiration compared to drained ones due to higher water table and lower soil oxygen (Komulainen et al., 1999; Laine et al., 2019). However some studies found no significant differences in ecosystem respiration after rewetting (Jurasinski et al., 2020; Komulainen et al., 1999). In Jurasinski et al. (2020) both wet and dry systems were alder forest and the rewetted treatment had significantly higher nutrient content than the drained system. In Komulainen et al. (1999) there were water table and vegetation composition differences between the plots measured within the rewetted treatment. When interpreting these results, it should be kept in mind that definitions of respiration differ; e.g., ecosystem respiration in Komulainen et al. (1999) and Laine et al. (2019) did not account for aboveground tree respiration. However, comparisons across treatments should still hold because the same measurement approach is used in any given study.

Methane emissions were consistently higher in rewetted treatments compared to drained treatments, due to restored anoxic conditions in the soil caused by increased water table (Urbanová et al., 2013; Koskinen et al., 2016; Laine et al., 2019; Jurasinski et al., 2020). CH4 emissions from the ditches were not included in the comparative studies. However, Koskinen et al. (2016) and Urbanová et al. (2013) included measurements from soil near the ditches.

Nitrous oxide emissions were lower in rewetted treatments compared to drained treatments across studies (Tauchnitz et al., 2015; Laine et al., 2019; Minkkinen et al., 2020), highlighting the relevance of soil oxygen availability in N2O emissions. However, the difference was not significant in the nutrient poor sites reported in Minkkinen et al. (2020) due to already low emissions measured in drained nutrient poor sites.

Field based comparative studies show that rewetting previously forested and drained peatlands increases CH4 emissions and decreases N2O emissions in nutrient rich systems. Rewetting can potentially decrease CO2 emissions by decreasing ecosystem respiration from drained and forested peatlands but few comparative field-based studies have been published.

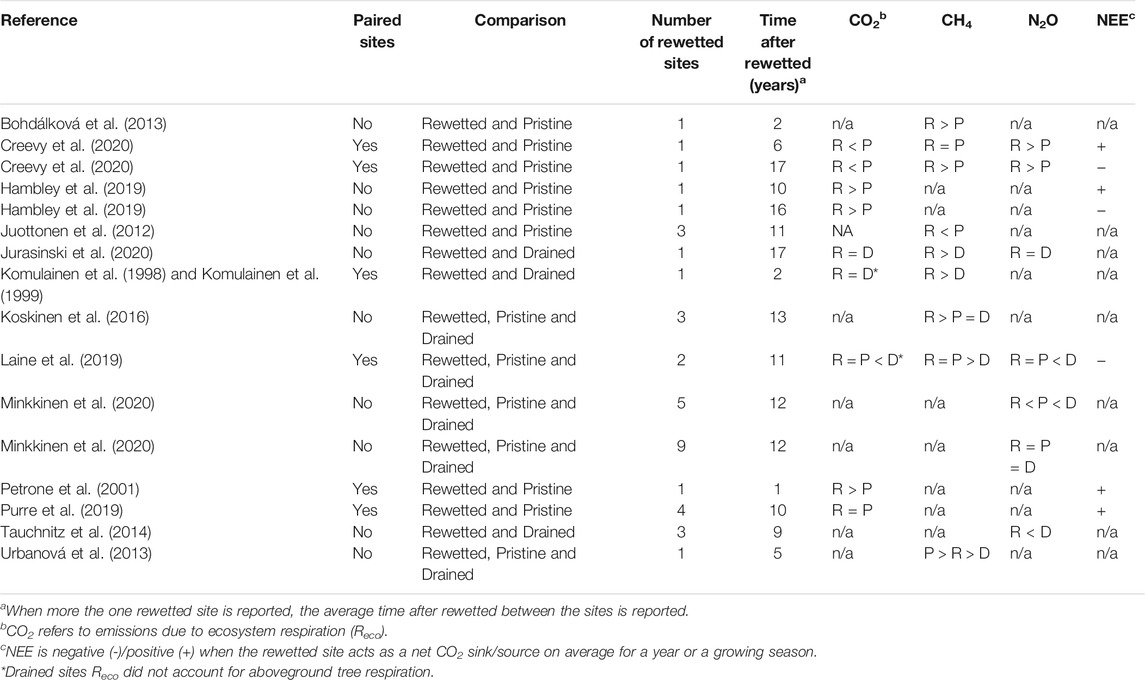

The difference in CO2 emissions between rewetted and pristine conditions is inconsistent (Table 1). Compared to pristine conditions, rewetting could result in lower CO2 emissions from ecosystem respiration (Creevy et al., 2020), higher emissions (Petrone et al., 2001; Hambley et al., 2019), or no difference (Purre et al., 2019). Both Hambley et al. (2019) and Purre et al. (2019) reported higher net ecosystem exchange and lower gross primary productivity in rewetted treatments. In contrast, Laine et al. (2019) and Creevy et al. (2020) found no significant differences. The oldest rewetted treatment in Creevy et al. (2020) had a lower net ecosystem exchange than the pristine counterpart, likely due to the higher water table in the rewetted system and sparse vegetation in the pristine system.

TABLE 1. Trends on GHG fluxes from field-based studies comparing rewetted peatlands with drained and pristine peatlands. D means drained, R means rewetted, and P means pristine. Higher (>) means significantly higher, lower (<) means significantly lower and equal (=) means no significant differences. Contrasting results between rewetted sites within studies are reported.

Most studies reported higher CH4 emissions in rewetted treatments compared to pristine conditions (Bohdálková et al., 2013; Koskinen et al., 2016; Creevy et al., 2020). This can be explained by time after restoration, differences in plant communities (Creevy et al., 2020) and higher water table in the rewetted sites reported in some studies (Koskinen et al., 2016). In contrast, Juottonen et al. (2012) and Urbanová et al. (2013) found lower CH4 emissions in rewetted treatments due to poor establishment of both microbial and plant communities. Laine et al. (2019) found similar levels of CH4 emission between rewetted and pristine. CH4 emissions in rewetted sites seems to depend on restoration of ecological communities typical of pristine peatlands.

Direct comparisons of N2O emissions from rewetted and pristine sites were only reported in two studies. Often, there were no significant differences in N2O emissions between rewetted and pristine sites (Laine et al., 2019; Minkkinen et al., 2020). However, some rewetted nutrient rich sites had lower N2O emissions than their pristine counterparts (Minkkinen et al., 2020).

Field-based comparisons between pristine peatlands and rewetted previously forested and drained peatlands show similar negligible N2O emissions. However, CO2 and CH4 emissions of rewetted sites can be higher, lower or the same as in pristine sites. Moreover, most rewetted sites were net sources of CO2 (Petrone et al., 2001; Hambley et al., 2019; Purre et al., 2019; Creevy et al., 2020). Net CO2 sinks in rewetted peatlands were scarcely reported. Two sites rewetted for at least 15 years were net CO2 sinks, highlighting the necessity to restore peatland plant communities for long-term carbon storage (Hambley et al., 2019; Creevy et al., 2020). Laine et al. (2019) also reported a net sink in rewetted treatments, but CO2 uptake was probably overestimated, because measurements were conducted in light saturated conditions.

Overall the number of comparative field-based studies on the subject remains limited, providing limited data suitable for performing quantitative meta-analysis. The results of the comparative studies are presented in Table 1.

Here we focus on one field study and four reviews discussing the overall impact of rewetting by estimating all major GHGs.

Through a direct field based comparison, Laine et al. (2019) calculated net GHG emissions from drained, pristine and rewetted peatlands for six sites during 2 years. The restored and pristine sites had on average lower net GHG emissions than the drained sites and during a wet year had negative net GHG emissions. The study did not account for aboveground tree respiration but considered total soil respiration.

The reviews generated emission factors (EFs) based on the IPCC guidelines and therefore did not account for vegetation related CO2 fluxes (Evans et al., 2017; Juutinen et al., 2020; Tiemeyer et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2016). Consequently, CO2 emissions represent the carbon balance between litter inputs and heterotrophic respiration. The reported EFs (Table 2) did not include dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and particulate organic carbon (POC) exports, even though these fluxes can be significant from a full carbon balance perspective and had been accounted in some studies (Wilson et al., 2016; Evans et al., 2017).

TABLE 2. Greenhouse gas emissions presented in t CO2-eq ha−1 yr−1 for drained and rewetted peatlands. CH4 and N2O are converted to CO2-eq by their global warming potentials (GWP’s) on a 100 years scale including carbon feedbacks according to Myhre et al. (2013).

Net GHG emissions were higher at drained sites than in rewetted soils except for temperate nutrient rich soils in Wilson et al. (2016). Boreal organic soils had lower net GHG emissions than temperate ones at any nutrient level, whereas nutrient rich organic soils had higher emissions than nutrient poor soils in both climate zones.

Wilson et al. (2016) concluded that rewetting reduces net total soil GHG emissions of drained forested peatlands by 74, 27 and 74% in boreal nutrient rich, boreal nutrient poor and temperate nutrient poor systems respectively. Tiemeyer et al. (2020) estimated 72% reduction in net emissions from drained and forested peatlands in Germany when rewetted. Juutinen et al. (2020) developed reference emission levels for different types of boreal forested and drained soils, and for rewetted soils and concluded that rewetting reduces drained peatlands net GHG emissions only under some conditions. In contrast, Evans et al. (2017) established that converting forested drained organic soils into fens or bogs through rewetting can reduce net GHG emissions by 53 and 102%, respectively. The reviews estimated mostly net positive GHG emissions from rewetting drained and forested peatlands, contrary to observations of net carbon sinks in non-managed and waterlogged peatlands. Estimations were highly variable both for forested and rewetted system, which might be explained by both lack of empirical data and high dependence on local conditions. Furthermore, these reviews did not include time after restoration, therefore they give limited insight into the time dependent effects of rewetting.

In general, comparative studies did not always consider the same GHG fluxes. Studies accounted differently for tree related carbon fluxes. Some studies incorporated carbon exports (e.g., POC and DOC) within the GHG balance (Wilson et al., 2016; Evans et al., 2017) while others did not. Moreover, the implications of ditches on site emissions were often not accounted within the system balance. Differences in system boundaries limited the comparisons across studies and across systems. Furthermore, most studies compared GHG fluxes between systems through Global Warming Potential (GWP), which might overestimate initial climate benefits of rewetting due to the short term but strong warming effects of atmospheric CH4 (Ojanen and Minkkinen, 2020).

Combining existing empirical evidence, we conclude that rewetting generally reduces soil GHG emissions compared to drained conditions. Nevertheless, net emissions often remain positive for several years. Restoring GHG emissions to levels typical of pristine conditions can take more than 10 years. However, the lack of long-term rewetting experiments with consistent measurement leaves a gap in the observation of the effects of ecosystem functions that may require longer to recover after rewetting and may dominate the long-term regulation of GHG fluxes in rewetted sites such as vegetation succession and changes in soil properties (Creevy et al., 2020).

Several biological processes are affected by draining and rewetting, and therefore affect GHG production and consumption in peatlands.

Draining organic soils makes oxygen available in the soil. Changes in oxygen content generate a cascade of direct and indirect effects in processes producing and consuming GHGs. Furthermore, changes in water regimes affect gas transport by changing diffusion rates in soil and vegetation.

Under conditions of high nutrient and water availability, oxygen promotes both organic matter inputs to the soil and mineralization rates. Under constant anoxic conditions, low biomass productivity—and thus low carbon input to soil—is compensated by even lower mineralization rates leading to peat accumulation. Organic matter is primarily protected electrochemically due to low redox potential and chemically due to the low nutrient content and high chemical recalcitrance of peatland vegetation.

Soil oxygen directly enhances GHG production by acting as electron acceptor in metabolic reactions that produce CO2 and N2O (i.e., heterotrophic microbial respiration and nitrification). Indirectly, soil oxygen increases other substrates required by heterotrophic microbial respiration and nitrification by directly enhancing organic matter breakdown leading to higher dissolved organic matter content and NH4+ content. Furthermore, soil oxygen indirectly increases heterotrophic respiration by promoting vascular plant communities that increase litterfall rates and quality, which in turn provide high quality substrates for soil microbes. By enhancing dissolved organic matter content and nitrification, soil oxygen has also an indirect positive effect on denitrification, causing N2O production. Soil oxygen availability is associated with water unsaturated conditions, which—by increasing diffusion rates—promote CO2 emissions and incomplete reduction of NO3− leading to N2O volatilization.

The effect of rewetting on these processes are described in more detail in the following section, and their relations are illustrated by a set of causal loop diagrams.

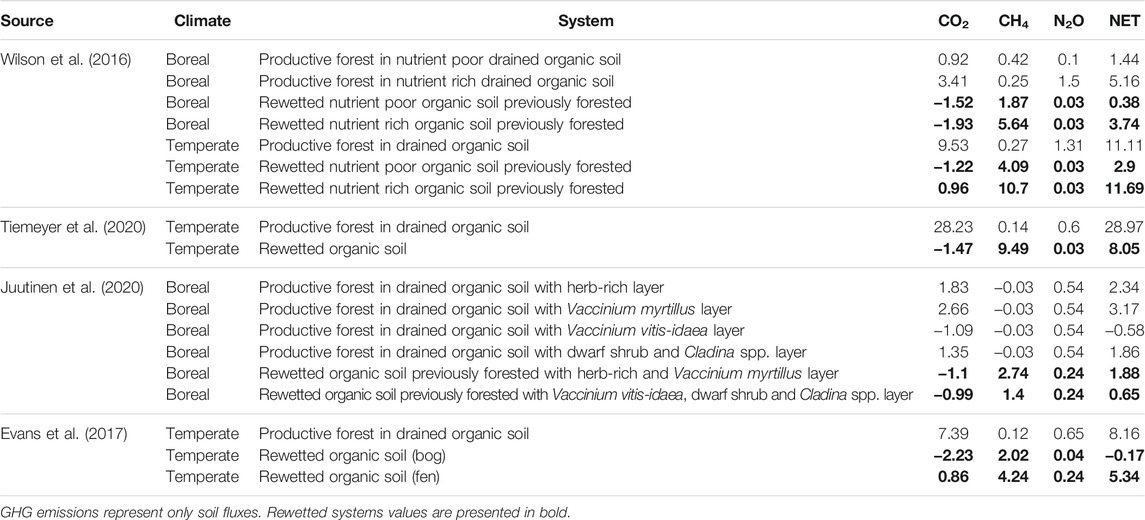

Soil water content is the main control of soil oxygen content by limiting gas exchanges as pores become saturated (Skopp et al., 1990; Sierra et al., 2015, 2017). In drained organic soils, rewetting through ditch blocking decreases lateral outflow, increasing soil water content, raising the water table, and ultimately decreasing soil oxygen content (Silins and Rothwell, 1999; Lohila et al., 2011).

Lowering soil oxygen content indirectly decreases CO2 uptake by limiting plant productivity compared to drained peatlands (Kozlowski, 1986; Gyimah et al., 2020). Water saturation limits root respiration and thus root activity affecting plant growth (Ben-Noah and Friedman, 2018; Bhanja and Wang, 2021) and restricting most species associated with productive forestry (Arnold et al., 2005). Diminished plant growth decreases litterfall (Neumann et al., 2018; Giweta, 2020), which represents the main carbon and nitrogen input to the soil (Janssens et al., 2010; Lohila et al., 2011; Soylu et al., 2014; Bhanja and Wang, 2021).

However, decreasing lateral outflow in drained peatlands can ultimately decrease leaching, which can limit losses of mineral nutrients and dissolved organic carbon that could otherwise be stabilized into soil organic matter (Haapalehto et al., 2014; Nieminen et al., 2018).

Rewetting previously forested drained peatlands decreases ecosystem productivity and carbon inputs to the soil. The main causal pathways and mechanistic understanding relating soil water content to CO2 uptake by vegetation and litter production are illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Causal loop diagram of the main effects of water table management on plant biomass and litterfall. An arrow with a plus sign (blue) indicates a change in the variable affected that is in the same direction as the change in the driving variable, an arrow with a minus sign (red) indicates a change in variable affected that is in the opposite direction as the change in the driving variable.

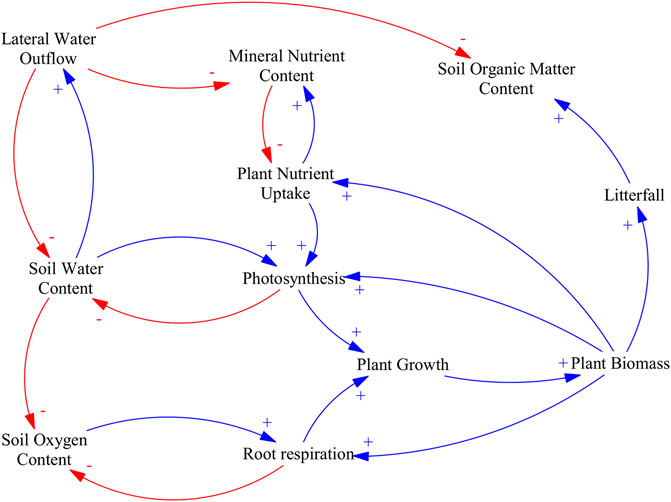

Plant community composition controls litterfall quality. Long-term water saturation caused by rewetting promotes gradual changes in plant communities (Urbanová and Bárta, 2020). Peat soils characterized by high mineral nutrient, medium pH, low soil oxygen content and high soil water content promote plant communities dominated by specialized vascular plants such as wetland sedges (Carex spp.) and some forbs species (Robroek et al., 2015; Laine et al., 2021). In contrast, peat soils characterized by low mineral nutrient content, low pH, low soil oxygen content and high soil water content enhance plant communities dominated by peat mosses (Sphagnum spp.) (Bragazza and Gerdol, 2002; Glina et al., 2019; Bengtsson et al., 2021).

Increased Sphagnum mosses dominance in the plant community decreases overall litterfall quality (Bragazza et al., 2009). Vascular plant litter can be almost three times more labile than Sphagnum litter when measured through decomposition rates, because Sphagnum litter is characterized by low nutrient and high phenolic contents (Bragazza et al., 2009).

In poor and acidic peats, rewetting can promote plant communities characterized by recalcitrant litter. The main causal pathways and mechanistic understanding relating soil oxygen content, pH and nutrient contents to litterfall quality are illustrated in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2. Causal loop diagram of the main effects of water table management in litterfall quality. An arrow with a plus sign (blue) indicates a change in the variable affected that is in the same direction as the change in the driving variable, an arrow with a minus sign (red) indicates a change in variable affected that is in the opposite direction as the change in the driving variable.

Litterfall rate and litter quality control soil organic matter content and quality, by affecting organic matter breakdown and nutrient retention during decomposition (Luo and Zhou, 2006; Horwath, 2015; Normand et al., 2021). Organic matter breakdown transforms particulate organic matter into dissolved organic matter available for microbial consumption (Eijsackers and Zehnder, 1990; Reddy and DeLaune, 2008b; Horwath, 2015). During decomposition, nutrients are immobilized if substrate is nutrient poor, or released if it is nutrient rich in mineral form, resulting in typical trajectories of decreasing substrate C:N:P through time (Manzoni et al., 2010). The breakdown rate is enhanced by temperature, soil water content (below soil field capacity), soil oxygen content (above soil field capacity), and is regulated by chemical composition and enzymatic activities (Luo and Zhou, 2006; Horwath, 2015).

Peatlands are characterized by high soil organic matter content, and frequently by low soil organic matter quality (Heller et al., 2015; Szajdak et al., 2020). Rewetting decreases soil oxygen content which inhibits microbial activity by requiring microbes to use less energetically efficient electron acceptors, thus resulting in low decomposition rates and carbon accumulation (Skopp et al., 1990; Sierra et al., 2015, 2017). Moreover, low soil oxygen decreases oxygenases activity which are enzymes capable of breaking resistant organic compounds. Low oxygen limits substrate for oxygenases mediated reactions and limits microbial metabolisms capable of oxygenases synthesis (Freeman et al., 2001; Reddy and DeLaune, 2008b; Sinsabaugh, 2010; Plante et al., 2015). Furthermore, hydrolase enzymes, which are not limited by oxygen, might be further inhibited by phenolic compounds commonly found in Sphagnum litter (Freeman et al., 2001), thus contributing to soil organic matter accumulation rates in peatland ecosystems, although this remains disputed (Wen et al., 2019; Urbanová and Hajek, 2021). Hydrolases and oxygenases content increases as microbial metabolism increases but decreases with high dissolved organic matter content (Allison and Vitousek, 2005).

Rewetting decreases organic matter breakdown by acting directly on soil oxygen content and indirectly on microbial and enzyme composition and activity. The main causal pathways and mechanistic understanding relating soil water content, soil oxygen content and organic matter breakdown are illustrated in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3. Causal loop diagram of the main effects of water table management in mineralization rates. An arrow with a plus sign (blue) indicates a change in the variable affected that is in the same direction as the change in the driving variable, an arrow with a minus sign (red) indicates a change in variable affected that is in the opposite direction as the change in the driving variable.

Dissolved organic carbon derived from organic matter breakdown is mineralized into CO2 and CH4 by different microbial groups. Simultaneously, CO2 and CH4 can also be consumed (Horwath, 2015; Robertson and Groffman, 2015; Feng et al., 2020). Soil redox potential is primarily regulated by soil water content in peatlands (Lin et al., 2021), and in turn it regulates the dominant metabolic pathway through which carbon is mineralized (Reddy and DeLaune, 2008b).

Low oxygen content associated with water saturation decreases CO2 production by hindering root respiration and heterotrophic aerobic microbes (Horwath, 2015). Microbial heterotrophic aerobic metabolism is controlled by soil oxygen and soluble organic matter availability (Dalal et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2021), which explains reports of low CO2 emissions in water saturated peatlands and high CO2 emissions in drained organic soils (Wilson et al., 2016).

In contrast, water saturation associated with rewetting increases CH4 in soil by removing soil oxygen, which is toxic for most methanogenic microbes (Reddy and DeLaune, 2008b). This explains high sensitivity of CH4 emissions to water table fluctuations reported in both rewetted and pristine peatlands (Koskinen et al., 2016; Ritson et al., 2017).

In saturated peatlands, methanogenesis occurs through different pathways. Aceticlastic and hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis dominate in peatlands (Galand et al., 2005; Bräuer et al., 2020). Aceticlastic methanogenesis uses acetate generated by acetogenic bacteria and vascular plants as substrate and produces CO2 besides CH4 (Ye et al., 2012; Bräuer et al., 2020). Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis uses CO2 and H2 generated from fermentative bacteria as substrate (Reddy and DeLaune, 2008b). Both acetogenic and fermentative bacteria respond positively to decreases in soil oxygen associated with rewetting (Galand et al., 2005; Bräuer et al., 2020). Methanogenic activity is enhanced by organic substrate availability, therefore is highly dependent of plant community through litterfall quantity and quality (Putkinen et al., 2018; Urbanová and Bárta, 2020).

Acetoclastic methanogenesis is thought to account for 2/3 of methane production in peatlands (Bräuer et al., 2020). However, some hydrogenotrophic methanogens respond better to nutrient poor and acidic conditions which explain their importance in bogs (Galand et al., 2005; Bräuer et al., 2020). Furthermore, some hydrogenotrophic methanogens seem to be more tolerant to oxygen giving them an advantage in drained or not fully restored peatlands (Urbanová and Bárta, 2020).

However, CH4 produced in peatlands can be consumed and oxidized into CO2 by autotrophic methanotrophs in the presence of oxygen (Agethen et al., 2018; Grodnitskaya et al., 2018). This process can be important in peat upper layers when unsaturated conditions or high oxygen diffusion through plant roots take place (Agethen et al., 2018).

Despite water saturation and low soil oxygen content conditions, peatland methanogenesis can be inhibited by more efficient non-aerobic heterotrophic microbial metabolism in the presence of other electron acceptors such as SO42− and NO3− (Blodau et al., 2007; Ye et al., 2012; Agethen et al., 2018). Moreover, low pH directly down-regulates the activity of organisms involved in methanogenesis and fermentation (Ye et al., 2012). Oxidized-sulfur containing compounds produced by Sphagnum and low pH associated with bogs partially explain lower methane emissions in bogs compared to fens (AminiTabrizi et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, water table is the main control of carbon mineralization pathways in peatlands. The main causal pathways and mechanistic understanding relating soil water content, soil oxygen, CH4 production and CO2 production are illustrated in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4. Causal loop diagram of the main effects of water table management in carbon mineralization pathways. An arrow with a plus sign (blue) indicates a change in the variable affected that is in the same direction as the change in the driving variable, an arrow with a minus sign (red) indicates a change in variable affected that is in the opposite direction as the change in the driving variable.

N2O is mostly an intermediate product of both nitrification and denitrification. Soluble organic nitrogen derived from organic matter breakdown is mineralized into ammonium (NH4+) by microbes which is in turn transformed into NO3− through nitrification and into N2 through denitrification.

Pathways of N2O production in nitrification are not fully understood, especially for nitrifying archaea (Tzanakakis et al., 2019), however there is evidence that nitrification is an important source of N2O in forested drained peatlands (Liimatainen et al., 2018). Rewetting hinders nitrification by reducing O2 availability which is required by nitrifiers to oxidized NH4+.

Lower soil oxygen caused by rewetting might also decrease NH4+ content through lower organic nitrogen mineralization rates (Khalil et al., 2004; Pauleta et al., 2013). However, lower soil oxygen content can also reduce microbial nitrogen demand by decreasing microbial C-use efficiency, leading to NH4+ mineralization and NH4+ accumulation in soil. Therefore, critical C:N ratios leading to mineral nitrogen immobilization are higher in water saturated environments such as pristine and rewetted peatlands (Reddy and DeLaune, 2008c).

Being mostly an anaerobic process, denitrification increases when soil oxygen content decreases (Seitzinger et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2020). However, denitrification requires soluble organic carbon, protons (H+) and nitrate (NO3−) (Seitzinger et al., 2006; Reddy and DeLaune, 2008c; Wang Cong et al., 2021). Nitrification, which decreases when soil oxygen content is reduced, is the main source of soil nitrate (NO3−) in non-fertilized systems such as most of the afforested and not managed peatlands. However, atmospheric deposition can be an important source of NO3−.

Even though denitrification increases N2O in soil, many denitrifiers produce the enzyme N2O reductase which further reduces N2O into N2 (Robertson and Groffman, 2015). N2O reductase activity increases when soil oxygen decreases (Baggs, 2011; Wan et al., 2012). High soil copper (Cu) availability and high pH might also promote N2O reductase activity in northern peatlands (Liimatainen et al., 2018). Microbial community composition also explain N2O reductase activity, for example denitrifying fungi are not capable of synthetizing N2O reductase (Baggs, 2011; Wan et al., 2012).

Organic matter nitrogen content has been proposed as the main control for N2O emissions in northern drained peatlands (Klemedtsson et al., 2005). High emissions of N2O in drained peatlands are associated with nitrogen-rich organic matter, with C:N ratios lower than 30 (Klemedtsson et al., 2005; Liimatainen et al., 2018). Drainage and afforestation of peatlands tends to generate relative N enrichment, decreasing C:N ratios through peat degradation and increasing N mineralization (Krüger et al., 2015; Lasota and Błońska, 2021). Moreover, drained peatlands tend to have higher bulk density and lower porosity than pristine peatlands, which can lead to rapid saturation after rain, causing N2O pulses due denitrification associated with temporary anoxic conditions and high NO3− availability (Reay et al., 2004; Cui et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019).

Due to the contrasting effect of soil oxygen content on nitrification and denitrification dependence of nitrification byproducts, N2O production optimum water filled pore space varies between 50 and 90% in boreal peats (Regina et al., 1998). When considering the mean annual water table depth as predictor of N2O production instead of soil saturation, the optimum depth is around −25 cm (Jungkunst et al., 2004). Main causal pathways and mechanistic understanding relating soil water content, soil oxygen and N2O production are illustrated in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5. Causal loop diagram of the main effects of water table management in nitrogen mineralization pathways. An arrow with a plus sign (blue) indicates a change in the variable affected that is in the same direction as the change in the driving variable, an arrow with a minus sign (red) indicates a change in variable affected that is in the opposite direction as the change in the driving variable.

GHG transport can occur via gas transport processes such as diffusion or convection in soils (Blagodatsky and Smith, 2012) or via plant mediated transport in the xylem or aerenchyma, and exchange through the stomata (Bhullar et al., 2013; McNicol et al., 2017). GHG transport is affected directly and indirectly by water content and therefore rewetting (Segers, 1998; Reddy and DeLaune, 2008a) as is illustrated in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6. Causal loop diagram of the main effects of water table management in carbon mineralization pathways. An arrow with a plus sign (blue) indicates a change in the variable affected that is in the same direction as the change in the driving variable, an arrow with a minus sign (red) indicates a change in variable affected that is in the opposite direction as the change in the driving variable.

GHG diffusion is controlled by gaseous concentration gradients; therefore, diffusion rates are enhanced by GHG concentration in soil. Diffusion rates decrease with soil water content and increases with soil porosity and pore connectivity (Blagodatsky and Smith, 2012; Ball, 2013). Peat soils are characterized by high porosity, typically around 80% in the upper 30 cm (Rezanezhad et al., 2016). Rewetting peatlands decreases diffusion rates by increasing soil water content. However, long term drainage decreases total porosity and thus the relative abundance of large pores that promote pore connectivity (Wang Mairoun et al., 2021). Diffusion is likely the main pathway of CO2 and N2O emission to the atmosphere in drained peatlands. High diffusion rates might hinder the complete reduction of N2O during denitrification by releasing N2O before it can be consumed partially explaining high N2O emissions in drained peatlands with high nutrient content.

Mass flow is a convective movement of gases, so it depends of total pressure differences between the soil and the atmosphere (Reddy and DeLaune, 2008a; Ball, 2013; Kreba et al., 2017). Mass flow is enhanced when atmospheric pressure decreases which can be caused by wind movement (Reddy and DeLaune, 2008a). Under waterlogged conditions such as those in rewetted and pristine peatlands, CH4 accumulation in soil can lead to mass flow events in forms of bubbles passing through water commonly referred as ebullition (Blagodatsky and Smith, 2012). Ebullition can account for 50–64% of total CH4 flux in northern peatlands under water saturation (Tokida et al., 2007).

Plant mediated transport is driven by gas partial pressure differences between the plant tissue and the surroundings (Grosse and Frick, 1999). This process is facilitated by plant total porosity which reduces gas transport resistance (Reddy and DeLaune, 2008a). Plant total porosity is a function of several properties such as leaf area and the pore density of specific type tissue (e.g., aerenchyma) and can be limited by temporary reduction of leaf gas exchanges by stomatal closure (Reddy and DeLaune, 2008a). Under water saturated and high nutrient availability conditions, like those found in some rewetted and pristine peatlands, vegetation communities with high plant tissue porosity can dominate, which facilitates plant mediated transport (Bhullar et al., 2013; Valiranta et al., 2017). Plant mediated transport can be an important pathway for methane and nitrous oxide emissions (Greenup et al., 2000; Agethen et al., 2018), but also for soil oxygen replenishment, increasing methane oxidation in the rhizosphere (Agethen et al., 2018). Some studies indicate that methane oxidation might dominate over methane facilitated transport (Bhullar et al., 2013).

Peatland restoration through rewetting seems to require between 15 and 30 years to yield ecosystem functions typical of pristine peatlands. However, both incomplete empirical data and process understanding hinder our knowledge about rewetting effect through time. Rewetting effect is highly dependent on local characteristics and site history (Kreyling et al., 2021). Moreover, peatland restoration is often done by clear cutting and ditch blocking, but it can include active vegetation transfer, mulching and microtopography modifications (Gorham and Rochefort, 2003). Initial hydrological properties, peat degradation, nutrient status and restoration approach are likely to affect the revegetation and hydrological responses to increased water table. This would likely affect restoration trajectory and, subsequently, GHG fluxes over time (Nugent et al., 2019; Purre et al., 2020). Higher nutrient availability associated with fens might lead to a faster and more dynamic response to rewetting. However, simpler hydrology associated with bogs might increase the likelihood of successful restoration. Here we conceptualize the consequences of rewetting on GHG fluxes over time by separating restoration in three phases in relation to peat hydrological and ecological properties.

The first restoration phase is characterized by an increase in water table due to lower tree transpiration and reduced lateral water outflow. Initially, in this phase the water table might be lower than in a pristine state (Menberu et al., 2016), however mean annual water table might recover fast (Haapalehto et al., 2011). Water table variability is likely higher than in the pristine state because lower soil macroporosity and higher bulk density developed after long term drainage have a negative effect on hydraulic conductivity and water storage capacity (Ahmad et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Kreyling et al., 2021). High organic substrate availability is expected due to rewetting associated disturbances, tree residues, turnover of tree roots and its associated microbial biomass and expansion of wetland vascular plants (Rigney et al., 2018; Vestin et al., 2020). High nutrient availability due to low plant nutrient demand is expected which, added to rewetting associated disturbances, might promote high nutrients exports often reported after rewetting (Koskinen et al., 2017; Nieminen et al., 2020). Due to enhanced decomposition, this phase might be characterized by high dissolved organic matter concentrations (Negassa et al., 2021). Vegetation during this phase is patchy (Hedberg et al., 2012) and growth of mosses such as Sphagnum is likely limited by high water table variability (Kim et al., 2021). Proliferation of wetland associated vascular plants is likely due to nutrient availability, however the specific species will likely be influenced by pH (Kozlov et al., 2016).

The second phase of restoration is characterized by high water table due to effective water outflow control by years of ditch blocking. However, pore size distribution and bulk density are not expected to be fully recovered (Kreyling et al., 2021), leading to high water table variability and oxic pulses especially in highly degraded peat (Kim et al., 2021). Water table variability might continue to inhibit Sphagnum proliferation and sustain vascular plants, leading to more labile litterfall compared to pristine conditions (Bragazza et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2021). Oxic periods promote the decomposition of recalcitrant peat, thereby increase nutrient content and labile organic substrate availability (Górecki et al., 2021). Vegetation cover and CO2 uptake capacity is expected to be recovered (Alderson et al., 2019; Lees et al., 2019). However, plant communities might not have the same composition as in a pristine state and are likely influenced by nutrient content and peat degradation at the moment of restoration (Hedberg et al., 2012; Kreyling et al., 2021).

The third phase of restoration is characterized by recovery of the ecological characteristics associated with pristine peatlands and soil physical properties are mostly restored alongside typical water table dynamics. During this phase vegetation cover is fully recovered and plant community is characterized by typical peatlands genera such as Sphagnum, Eriophorum and Carex. Final composition will likely be a function of nutrient content and pH (Laine et al., 2021). There is evidence of effective restoration of ecological properties through rewetting (Menberu et al., 2016; Alderson et al., 2019; Ahmad et al., 2020; Purre et al., 2020), but this process might require up to 30 years and for some systems might not be possible due to changes associated with long term drainage (Holden et al., 2004; Kreyling et al., 2021).

The time that each restoration phase would require is likely sensitive to site specific characteristics and restoration approach. However, recovery is expected to take between 10 and 30 years. The first phase is likely to take between 3 and 5 years, while the second phase might require between 5 and 25 years.

Soil CO2 emissions are expected to be lower than in drained sites during the first restoration phase (Komulainen et al., 1999). However, the system will likely be a net source of CO2 (Petrone et al., 2001; Hambley et al., 2019; Creevy et al., 2020) (Figure 7). High rates of aerobic heterotrophic respiration sustained by organic substrate availability, mineral nutrient availability and oxic conditions in the upper layers of the peat are expected. Moreover, CO2 uptake rate is anticipated to be low due to sparse vegetation.

FIGURE 7. Theoretical effect of rewetting in CO2 soil emissions through time. Negative emissions indicate net carbon uptake.

During the second phase of restoration, soil CO2 emissions are expected to be significantly lower compared with drained status because of increased water table (Wilson et al., 2016; Laine et al., 2019). Due to increased photosynthesis and decreased autotrophic respiration the system will be approaching to carbon neutrality during this phase (Laine et al., 2019; Purre et al., 2020).

The restored peatlands will be a net CO2 sinks during the third phase of restoration due to high anoxic conditions, proper restoration of peat forming vegetation communities and slow decomposition (Hambley et al., 2019; Creevy et al., 2020). Therefore, an overall transition from CO2 source to sink is expected during this phase.

CH4 emissions will increase with time during the first phase due to labile organic substrate availability, mineral nutrient availability, increasing water table and progressive establishment of methanogenic microbes and associated microbial communities (e.g., fermentative bacteria) (Figure 8). CH4 emission will be higher than in a drained state even without a fully recovered water table (Komulainen et al., 1998; Urbanová et al., 2013). Water bodies created by ditch blocking might be important sources of CH4 emissions during this phase.

During the second phase of restoration, CH4 emissions are expected to be higher than in the drained state and even higher than in the pristine state (Vanselow-Algan et al., 2015; Abdalla et al., 2016; Koskinen et al., 2016). High methane emissions are associated with labile litter availability related to vascular plant, mineral availability due to mineralization during oxic pulses and gas transport facilitation by plant communities with porous tissues (Vanselow-Algan et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017; Rigney et al., 2018). However, if plant community recovering is low during this phase, lower CH4 emissions compared to pristine state might occur due to low substrate availability associated with low litter inputs (Putkinen et al., 2018; Urbanová and Bárta, 2020) and reduced proliferation of methanotrophs (Dunfield and Dedysh, 2014; Robroek et al., 2015).

The restored peatlands will be a source of CH4 during the third phase, but emissions levels are expected to correspond to those reported for pristine sites (Laine et al., 2019; Creevy et al., 2020). Overall CH4 emission are thus expected to increase after rewetting, but then decrease as restoration progresses and plant communities recover.

N2O emissions will decrease after rewetting due to lower diffusivity and the negative effect of lower oxygen on nitrification (Tauchnitz et al., 2015) (Figure 9). However, some emissions can be expected (Vestin et al., 2020) due to the positive effect of lower nutrient competition on nitrification and enhanced denitrification due to lower oxygen content.

During the second phase, N2O emissions will be significantly reduced due to lower mineral nutrient availability caused by higher plant nutrient demand compared to the first phase. Some emissions might happen due to oxic pulses caused by water table variability.

In the long-term, the restored peatlands will be a negligible source of N2O due to low oxygen content and low diffusivity associated with restored hydrological properties, comparable to pristine sites (Minkkinen et al., 2020). To summarize, N2O emissions are expected to steadily decrease during the restoration.

Rewetting decreases soil related GHG emissions from drained and forested peatlands. However, considering fluxes from vegetation can alter the overall assessment of the GHG balance. The effect of rewetting on GHG fluxes is highly dependent on several factors such as nutrient status, soil physical properties and vegetation recovery. Water table restoration can turn a formerly drained peatland into a carbon sink, but recovering related ecosystem functions can take decades and has been scarcely reported. Long term monitoring of rewetted systems is thus required to fulfil observation gaps regarding the transient effect of rewetting on GHG fluxes.

Water table management changes soil oxygen content, which in turn directly and indirectly controls several processes that produce, consume, and transport GHG in peatlands. Soil oxygen directly affects plant growth, litterfall quality and quantity through plant community composition, organic matter breakdown rates, carbon mineralization pathways and rates, nitrification, denitrification and soil diffusivity which in turn control GHG fluxes. While these processes are relatively well understood in isolation, the complex relations among them make it difficult to scale up local and short-term GHG measurements to estimate the consequences of interventions at the landscape level and in the long-term.

Organic soil management is fundamental in the context of climate change. Long term integrated monitoring and dynamic modelling are necessary to improve our understanding regarding rewetting effects on GHG fluxes from organic soils and their sensitivity to local conditions and system definition. We hypothesized three different restoration phases for rewetted previously forested peatlands that could provide a framework to compare ongoing and future rewetting experiments based on restoration state rather than time per se, but could also support modelling exercises.

DE and SB designed the study. DE performed the study with constant support from SB and SM. DE wrote the article with constant support from SB and SM.

DE and SB had been supported by the project “A guide on how land-use management can convert high-emitting drained organic soils into areas with negative emissions” financed by FORMAS (project No 2019-01991). SM has been partly supported by the grant “Holistic management practices, modelling and monitoring for European forest soils” (H2020 Grant Agreement No 101000289).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abdalla, M., Hastings, A., Truu, J., Espenberg, M., Mander, Ü., and Smith, P. (2016). Emissions of Methane from Northern Peatlands: A Review of Management Impacts and Implications for Future Management Options. Ecol. Evol. 6 (19), 7080–7102. doi:10.1002/ece3.2469

Agethen, S., Sander, M., Waldemer, C., and Knorr, K.-H. (2018). Plant Rhizosphere Oxidation Reduces Methane Production and Emission in Rewetted Peatlands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 125, 125–135. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.07.006

Ahmad, S., Liu, H., Günther, A., Couwenberg, J., and Lennartz, B. (2020). Long-term Rewetting of Degraded Peatlands Restores Hydrological Buffer Function. Sci. Total Environ. 749, 141571. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141571

Alderson, D. M., Evans, M. G., Shuttleworth, E. L., Pilkington, M., Spencer, T., Walker, J., et al. (2019). Trajectories of Ecosystem Change in Restored Blanket Peatlands. Sci. Total Environ. 665, 785–796. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.095

Allison, S. D., and Vitousek, P. M. (2005). Responses of Extracellular Enzymes to Simple and Complex Nutrient Inputs. Soil Biol. Biochem. 37 (5), 937–944. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.09.014

AminiTabrizi, R., Wilson, R. M., Fudyma, J. D., Hodgkins, S. B., Heyman, H. M., Rich, V. I., et al. (2020). Controls on Soil Organic Matter Degradation and Subsequent Greenhouse Gas Emissions across a Permafrost Thaw Gradient in Northern Sweden. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 381. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.557961

Anderson, V., and Johnson, L. (1997). Systems Thinking Basics: From Concepts to Causal Loops. Pegasus Commun.

Arnold, K. V., Weslien, P., Nilsson, M., Svensson, B. H., and Klemedtsson, L. (2005). Fluxes of CO2, CH4 and N2O from Drained Coniferous Forests on Organic Soils. For. Ecol. Manag. 210 (1), 239–254. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2005.02.031

Baggs, E. M. (2011). Soil Microbial Sources of Nitrous Oxide: Recent Advances in Knowledge, Emerging Challenges and Future Direction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustainability 3 (5), 321–327. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2011.08.011

Ball, B. C. (2013). Soil Structure and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A Synthesis of 20 Years of Experimentation. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 64 (3), 357–373. doi:10.1111/ejss.12013

Ben-Noah, I., and Friedman, S. P. (2018). Review and Evaluation of Root Respiration and of Natural and Agricultural Processes of Soil Aeration. Vadose Zone J. 17 (1), 170119. doi:10.2136/vzj2017.06.0119

Bengtsson, F., Rydin, H., Baltzer, J. L., Bragazza, L., Bu, Z. J., Caporn, S. J. M., et al. (2021). Environmental Drivers of Sphagnum Growth in Peatlands across the Holarctic Region. J. Ecol. 109 (1), 417–431. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.13499

Bhanja, S. N., and Wang, J. (2021). Influence of Environmental Factors on Autotrophic, Soil and Ecosystem Respirations in Canadian Boreal forest. Ecol. Indicators 125, 107517. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107517

Bhullar, G. S., Iravani, M., Edwards, P. J., and Olde Venterink, H. (2013). Methane Transport and Emissions from Soil as Affected by Water Table and Vascular Plants. BMC Ecol. 13, 32. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-13-32

Blagodatsky, S., and Smith, P. (2012). Soil Physics Meets Soil Biology: Towards Better Mechanistic Prediction of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 47, 78–92. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.12.015

Blodau, C., Mayer, B., Peiffer, S., and Moore, T. R. (2007). Support for an Anaerobic Sulfur Cycle in Two Canadian Peatland Soils. J. Geophys. Res. 112 (G2), G02004. doi:10.1029/2006JG000364

Bohdálková, L., Čuřík, J., Aa, K., and Bůzek, F. (2013). Dynamics of Methane Fluxes from Two Peat Bogs in the Ore Mountains, Czech Republic. Plant Soil Environ. 59, 14–21. doi:10.17221/330/2012-PSE

Bragazza, L., Buttler, A., Siegenthaler, A., and Mitchell, E. A. D. (2009). “Plant Litter Decomposition and Nutrient Release in Peatlands,” in Carbon Cycling in Northern Peatlands American Geophysical Union (AGU), 99–110. doi:10.1029/2008GM000815

Bragazza, L., and Gerdol, R. (2002). Are Nutrient Availability and Acidity‐alkalinity Gradients Related in Sphagnum‐dominated Peatlands. J. Vegetation Sci. 13 (4), 473–482. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2002.tb02074.x

Chapin, F. S., Woodwell, G. M., Randerson, J. T., Rastetter, E. B., Lovett, G. M., Baldocchi, D. D., et al. (2006). Reconciling Carbon-Cycle Concepts, Terminology, and Methods. Ecosystems 9 (7), 1041–1050. doi:10.1007/s10021-005-0105-7

Conchedda, G., and Tubiello, F. N. (2020). Drainage of Organic Soils and GHG Emissions: Validation with Country Data. Biosph. – Biogeosciences. doi:10.5194/essd-2020-202

Creevy, A. L., Payne, R. J., Andersen, R., and Rowson, J. G. (2020). Annual Gaseous Carbon Budgets of forest-to-bog Restoration Sites Are Strongly Determined by Vegetation Composition. Sci. Total Environ. 705, 135863. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135863

Cui, Q., Song, C., Wang, X., Shi, F., Wang, L., and Guo, Y. (2016). Rapid N2O Fluxes at High Level of Nitrate Nitrogen Addition during Freeze-Thaw Events in Boreal Peatlands of Northeast China. Atmos. Environ. 135, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.03.053

Dalal, R. C., Allen, D. E., Dalal, R. C., and Allen, D. E. (2008). Greenhouse Gas Fluxes from Natural Ecosystems. Aust. J. Bot. 56 (5), 369–407. doi:10.1071/BT07128

Dunfield, P. F., and Dedysh, S. N. (2014). Methylocella: A Gourmand Among Methanotrophs. Trends Microbiol. 22 (7), 368369. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2014.05.004

Eijsackers, H., and Zehnder, A. J. B. (1990). Litter Decomposition: A Russian Matriochka Doll. Biogeochemistry 11 (3), 153–174. doi:10.1007/BF00004495

Evans, C., Artz, R., Moxley, J., Taylor, E., Archer, N., Burden, A., et al. (2017). Implementation of an Emissions Inventory for UK Peatlands. Bangor: Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, 93.

FAO (2020). Peatlands Mapping and Monitoring–Recommendations and technical overview. Rome: FAO. doi:10.4060/ca8200en

Feng, H., Guo, J., Han, M., Wang, W., Peng, C., Jin, J., et al. (2020). A Review of the Mechanisms and Controlling Factors of Methane Dynamics in forest Ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 455, 117702. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117702

Freeman, C., Ostle, N., and Kang, H. (2001). An Enzymic ‘latch' on a Global Carbon Store. Nature 409 (6817), 149. doi:10.1038/35051650

Galand, P. E., Fritze, H., Conrad, R., and Yrjälä, K. (2005). Pathways for Methanogenesis and Diversity of Methanogenic Archaea in Three Boreal Peatland Ecosystems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 (4), 2195–2198. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.4.2195-2198.2005

Giweta, M. (2020). Role of Litter Production and its Decomposition, and Factors Affecting the Processes in a Tropical forest Ecosystem: A Review. J Ecology Environ. 44 (1), 11. doi:10.1186/s41610-020-0151-2

Glina, B., Piernik, A., Hulisz, P., Mendyk, Ł., Tomaszewska, K., Podlaska, M., et al. (2019). Water or Soil-What Is the Dominant Driver Controlling the Vegetation Pattern of Degraded Shallow Mountain Peatlands. Land Degrad. Dev. 30 (12), 1437–1448. doi:10.1002/ldr.3329

Górecki, K., Rastogi, A., Stróżecki, M., Gąbka, M., Lamentowicz, M., Łuców, D., et al. (2021). Water Table Depth, Experimental Warming, and Reduced Precipitation Impact on Litter Decomposition in a Temperate Sphagnum-Peatland. Sci. Total Environ. 771, 145452. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145452

Gorham, E., and Rochefort, L. (2003). Peatland Restoration: A Brief Assessment with Special Reference to Sphagnum Bogs. Wetlands Ecol. Manag. 11 (1), 109–119. doi:10.1023/A:1022065723511

Greenup, A. L., Bradford, M. A., McNamara, N. P., Ineson, P., and Lee, J. A. (2000). The Role of Eriophorum Vaginatum in CH₄ Flux from an Ombrotrophic Peatland. Plant and Soil 227 (1/2), 265–272. doi:10.1023/a:1026573727311

Grodnitskaya, I. D., Trusova, M. Y., Syrtsov, S. N., and Koroban, N. V. (2018). Structure of Microbial Communities of Peat Soils in Two Bogs in Siberian Tundra and Forest Zones. Microbiology 87 (1), 89–102. doi:10.1134/S0026261718010083

Grosse, W., and Frick, H.-J. (1999). Gas Transfer in Wetland Plants Controlled by Graham's Law of Diffusion. Hydrobiologia 415 (0), 55–58. doi:10.1023/A:1003885701458

Gyimah, A., Wu, J., Scott, R., and Gong, Y. (2020). Agricultural Drainage Increases the Photosynthetic Capacity of Boreal Peatlands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 300, 106984. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2020.106984

Haapalehto, T., Kotiaho, J. S., Matilainen, R., and Tahvanainen, T. (2014). The Effects of Long-Term Drainage and Subsequent Restoration on Water Table Level and Pore Water Chemistry in Boreal Peatlands. J. Hydrol. 519, 1493–1505. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.09.013

Haapalehto, T. O., Vasander, H., Jauhiainen, S., Tahvanainen, T., and Kotiaho, J. S. (2011). The Effects of Peatland Restoration on Water-Table Depth, Elemental Concentrations, and Vegetation: 10 Years of Changes. Restoration Ecol. 19 (5), 587–598. doi:10.1111/j.1526-100X.2010.00704.x

Hambley, G., Andersen, R., Levy, P., Saunders, M., Cowie, N. R., Teh, Y. A., et al. (2019). Net Ecosystem Exchange from Two Formerly Afforested Peatlands Undergoing Restoration in the Flow Country of Northern Scotland. Mires and Peat 23, 346. doi:10.19189/MaP.2018.DW.346

Hedberg, P., Kotowski, W., Saetre, P., Mälson, K., Rydin, H., and Sundberg, S. (2012). Vegetation Recovery after Multiple-Site Experimental Fen Restorations. Biol. Conservation 147 (1), 60–67. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.01.039

Heller, C., Ellerbrock, R. H., Roßkopf, N., Klingenfuß, C., and Zeitz, J. (2015). Soil Organic Matter Characterization of Temperate Peatland Soil with FTIR-Spectroscopy: Effects of Mire Type and Drainage Intensity. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 66 (5), 847–858. doi:10.1111/ejss.12279

Holden, J., Chapman, P. J., and Labadz, J. C. (2004). Artificial Drainage of Peatlands: Hydrological and Hydrochemical Process and Wetland Restoration. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 28 (1), 95–123. doi:10.1191/0309133304pp403ra

Horwath, W. (2015). “Carbon Cycling,” in Soil Microbiology, Ecology and Biochemistry. Editor E. A. Paul. Fourth Edition (Academic Press), 339–382. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-415955-6.00012-8

Huang, Y., Ciais, P., Luo, Y., Zhu, D., Wang, Y., Qiu, C., et al. (2021). Tradeoff of CO2 and CH4 Emissions from Global Peatlands under Water-Table Drawdown. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11 (7), 618–622. doi:10.1038/s41558-021-01059-w

Hugelius, G., Loisel, J., Chadburn, S., Jackson, R. B., Jones, M., MacDonald, G., et al. (2020). Large Stocks of Peatland Carbon and Nitrogen Are Vulnerable to Permafrost Thaw. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 20438–20446. doi:10.1073/pnas.1916387117

Janssens, I. A., Dieleman, W., Luyssaert, S., Subke, J.-A., Reichstein, M., Ceulemans, R., et al. (2010). Reduction of forest Soil Respiration in Response to Nitrogen Deposition. Nat. Geosci 3 (5), 315–322. doi:10.1038/ngeo844

Jauhiainen, J., Alm, J., Bjarnadottir, B., Callesen, I., Christiansen, J. R., Clarke, N., et al. (2019). Reviews and Syntheses: Greenhouse Gas Exchange Data from Drained Organic forest Soils - a Review of Current Approaches and Recommendations for Future Research. Biogeosciences 16 (23), 4687–4703. doi:10.5194/bg-16-4687-2019

Jungkunst, H. F., Fiedler, S., and Stahr, K. (2004). N2O Emissions of a Mature Norway spruce (Picea Abies) Stand in the Black Forest (Southwest Germany) as Differentiated by the Soil Pattern. J. Geophys. Res. 109 (D7), 344. doi:10.1029/2003JD004344

Juottonen, H., Hynninen, A., Nieminen, M., Tuomivirta, T. T., Tuittila, E.-S., Nousiainen, H., et al. (2012). Methane-Cycling Microbial Communities and Methane Emission in Natural and Restored Peatlands. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 (17), 6386–6389. doi:10.1128/AEM.00261-12

Jurasinski, G., Ahmad, S., Anadon-Rosell, A., Berendt, J., Beyer, F., Bill, R., et al. (2020). From Understanding to Sustainable Use of Peatlands: The WETSCAPES Approach. Soil Syst. 4 (1), 14. doi:10.3390/soilsystems4010014

Juutinen, A., Tolvanen, A., Saarimaa, M., Ojanen, P., Sarkkola, S., Ahtikoski, A., et al. (2020). Cost-effective Land-Use Options of Drained Peatlands- Integrated Biophysical-Economic Modeling Approach. Ecol. Econ. 175, 106704. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106704

Kasimir, A., He, H., Coria, J., and Nordén, A. (2018). Land Use of Drained Peatlands: Greenhouse Gas Fluxes, Plant Production, and Economics. Glob. Change Biol. 24 (8), 3302–3316. doi:10.1111/gcb.13931

Khalil, K., Mary, B., and Renault, P. (2004). Nitrous Oxide Production by Nitrification and Denitrification in Soil Aggregates as Affected by O2 Concentration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 36 (4), 687–699. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.01.004

Kim, J., Rochefort, L., Hogue-Hugron, S., Alqulaiti, Z., Dunn, C., Pouliot, R., et al. (2021). Water Table Fluctuation in Peatlands Facilitates Fungal Proliferation, Impedes Sphagnum Growth and Accelerates Decomposition. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 717. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.579329

Klemedtsson, L., Von Arnold, K., Weslien, P., and Gundersen, P. (2005). Soil CN Ratio as a Scalar Parameter to Predict Nitrous Oxide Emissions. Glob. Change Biol 11 (7), 1142–1147. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.00973.x

Kløve, B., Berglund, K., Berglund, Ö., Weldon, S., and Maljanen, M. (2017). Future Options for Cultivated Nordic Peat Soils: Can Land Management and Rewetting Control Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Environ. Sci. Pol. 69, 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2016.12.017

Komulainen, V.-M., Nykänen, H., Martikainen, P. J., and Laine, J. (1998). Short-term Effect of Restoration on Vegetation Change and Methane Emissions from Peatlands Drained for Forestry in Southern Finland. Can. J. For. Res. 28 (3), 402–411. doi:10.1139/x98-011

Komulainen, V.-M., Tuittila, E.-S., Vasander, H., and Laine, J. (1999). Restoration of Drained Peatlands in Southern Finland: Initial Effects on Vegetation Change and CO2 Balance. J. Appl. Ecol. 36 (5), 634–648. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.1999.00430.x

Korkiakoski, M., Tuovinen, J.-P., Penttilä, T., Sarkkola, S., Ojanen, P., Minkkinen, K., et al. (2019). Greenhouse Gas and Energy Fluxes in a Boreal Peatland forest after clear-cutting. Biogeosciences 16 (19), 3703–3723. doi:10.5194/bg-16-3703-2019

Koskinen, M., Maanavilja, L. M., Nieminen, M., Minkkinen, K., and Tuittila, E.-S. (2016). High Methane Emissions From Restored Norway Spruce Swamps In Southern Finland Over One Growing Season. Mires and Peat 17 (2), 1–13. doi:10.19189/MaP.2015.OMB.202

Koskinen, M., Tahvanainen, T., Sarkkola, S., Menberu, M. W., Laurén, A., Sallantaus, T., et al. (2017). Restoration of Nutrient-Rich Forestry-Drained Peatlands Poses a Risk for High Exports of Dissolved Organic Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus. Sci. Total Environ. 586, 858–869. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.065

Kozlov, S. A., Lundin, L., and Avetov, N. A. (2016). Revegetation Dynamics after 15 Years of Rewetting in Two Extracted Peatlands in Sweden. Mires and Peat 18. doi:10.19189/MaP.2015.OMB.204

Kozlowski, T. T. (1986). Soil Aeration and Growth of forest Trees (Review Article). Scand. J. For. Res. 1 (1–4), 113–123. doi:10.1080/02827588609382405

Kreba, S. A., Wendroth, O., Coyne, M. S., and Walton, R. (2017). Soil Gas Diffusivity, Air‐Filled Porosity, and Pore Continuity: Land Use and Spatial Patterns. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 81 (3), 477–489. doi:10.2136/sssaj2016.10.0344

Kreyling, J., Tanneberger, F., Jansen, F., van der Linden, S., Aggenbach, C., Blüml, V., et al. (2021). Rewetting Does Not Return Drained Fen Peatlands to Their Old Selves. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 5693. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-25619-y

Krüger, J. P., Leifeld, J., Glatzel, S., Szidat, S., and Alewell, C. (2015). Biogeochemical Indicators of Peatland Degradation - a Case Study of a Temperate Bog in Northern Germany. Biogeosciences 12 (10), 2861–2871. doi:10.5194/bg-12-2861-2015

Laine, A. M., Lindholm, T., Nilsson, M., Kutznetsov, O., Jassey, V. E. J., and Tuittila, E. S. (2021). Functional Diversity and Trait Composition of Vascular Plant and Sphagnum moss Communities during Peatland Succession across Land Uplift Regions. J. Ecol. 109 (4), 1774–1789. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.13601

Laine, A. M., Mehtätalo, L., Tolvanen, A., Frolking, S., and Tuittila, E.-S. (2019). Impacts of Drainage, Restoration and Warming on Boreal Wetland Greenhouse Gas Fluxes. Sci. Total Environ. 647, 169–181. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.390

Laine, J., Minkkinen, K., and Trettin, C. (2009). “Direct Human Impacts on the Peatland Carbon Sink,”in. Carbon Cycling in Northern Peatlands. Geophysical Monograph Series. American Geophysical Union. Editors A. J. Baird, L. R. Belyea, X. Comas, A. S. Reeve, L. D. Slater, and D. Lee (Washington D.C.: AGU Geophysical Monograph Series), 184, 71–78.

Lasota, J., and Błońska, E. (2021). C:N:P Stoichiometry as an Indicator of Histosol Drainage in lowland and Mountain forest Ecosystems. For. Ecosyst. 8 (1), 39. doi:10.1186/s40663-021-00319-7

Lee, S.-C., Christen, A., Black, A. T., Johnson, M. S., Jassal, R. S., Ketler, R., et al. (2017). Annual Greenhouse Gas Budget for a Bog Ecosystem Undergoing Restoration by Rewetting. Biogeosciences 14 (11), 2799–2814. doi:10.5194/bg-14-2799-2017

Lees, K. J., Quaife, T., Artz, R. R. E., Khomik, M., Sottocornola, M., Kiely, G., et al. (2019). A Model of Gross Primary Productivity Based on Satellite Data Suggests Formerly Afforested Peatlands Undergoing Restoration Regain Full Photosynthesis Capacity after Five to Ten Years. J. Environ. Manage. 246, 594–604. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.03.040

Leifeld, J., Wüst-Galley, C., and Page, S. (2019). Intact and Managed Peatland Soils as a Source and Sink of GHGs from 1850 to 2100. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9 (12), 945–947. doi:10.1038/s41558-019-0615-5

Liimatainen, M., Voigt, C., Martikainen, P. J., Hytönen, J., Regina, K., Óskarsson, H., et al. (2018). Factors Controlling Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Managed Northern Peat Soils with Low Carbon to Nitrogen Ratio. Soil Biol. Biochem. 122, 186–195. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.04.006

Lin, Y., Campbell, A. N., Bhattacharyya, A., DiDonato, N., Thompson, A. M., Tfaily, M. M., et al. (2021). Differential Effects of Redox Conditions on the Decomposition of Litter and Soil Organic Matter. Biogeochemistry 154 (1), 1–15. doi:10.1007/s10533-021-00790-y

Liu, H., Price, J., Rezanezhad, F., and Lennartz, B. (2020). Centennial‐Scale Shifts in Hydrophysical Properties of Peat Induced by Drainage. Water Resour. Res. 56 (10), e2020WR027538. doi:10.1029/2020WR027538

Liu, H., Zak, D., Rezanezhad, F., and Lennartz, B. (2019). Soil Degradation Determines Release of Nitrous Oxide and Dissolved Organic Carbon from Peatlands. Environ. Res. Lett. 14 (9), 094009. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab3947

Lohila, A., Minkkinen, K., Aurela, M., Tuovinen, J.-P., Penttilä, T., Ojanen, P., et al. (2011). Greenhouse Gas Flux Measurements in a Forestry-Drained Peatland Indicate a Large Carbon Sink. Biogeosciences 8 (11), 3203–3218. doi:10.5194/bg-8-3203-2011

Luo, Y., and Zhou, X. (2006). “Controlling Factors,” in Soil Respiration and the Environment. Editors Y. Luo, and X. Zhou (Academic Press), 79–105. doi:10.1016/B978-012088782-8/50005-X

L. Bräuer, S., Basiliko, N., M. P. Siljanen, H. H., and H. Zinder, S. S. (2020). Methanogenic Archaea in Peatlands. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 367 (20). doi:10.1093/femsle/fnaa172

Manzoni, S., Trofymow, J. A., Jackson, R. B., and Porporato, A. (2010). Stoichiometric Controls on Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Dynamics in Decomposing Litter. Ecol. Monogr. 80 (1), 89–106. doi:10.1890/09-0179.1

Martens, M., Karlsson, N. P. E., Ehde, P. M., Mattsson, M., and Weisner, S. E. B. (2021). The Greenhouse Gas Emission Effects of Rewetting Drained Peatlands and Growing Wetland Plants for Biogas Fuel Production. J. Environ. Manage. 277, 111391. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111391

McNicol, G., Sturtevant, C. S., Knox, S. H., Dronova, I., Baldocchi, D. D., and Silver, W. L. (2017). Effects of Seasonality, Transport Pathway, and Spatial Structure on Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in a Restored Wetland. Glob. Change Biol. 23 (7), 2768–2782. doi:10.1111/gcb.13580

Menberu, M. W., Tahvanainen, T., Marttila, H., Irannezhad, M., Ronkanen, A.-K., Penttinen, J., et al. (2016). Water-table-dependent Hydrological Changes Following Peatland Forestry Drainage and Restoration: Analysis of Restoration success. Water Resour. Res. 52 (5), 3742–3760. doi:10.1002/2015WR018578

Minkkinen, K., Ojanen, P., Koskinen, M., and Penttilä, T. (2020). Nitrous Oxide Emissions of Undrained, Forestry-Drained, and Rewetted Boreal Peatlands. For. Ecol. Manag. 478, 118494. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118494

Montanarella, L., Jones, R. J. A., and Hiederer, R. (2006). The Distribution of Peatland in Europe. Mires and Peat 1 (1), 1–10.

Myhre, G., Shindell, D., Breon, F.-M., Collins, J., and Fuglestvedt, J. (2013). “Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis,” in Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Editors T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J. Doschunget al. (Cambridge University Press), 659–740.

Negassa, W., Eckhardt, K. U., Regier, T., and Leinweber, P. (2021). Dissolved Organic Matter Concentration, Molecular Composition, and Functional Groups in Contrasting Management Practices of Peatlands. J. Environ. Qual. 50 (6), 1364–1380. doi:10.1002/jeq2.20284

Neumann, M., Ukonmaanaho, L., Johnson, J., Benham, S., Vesterdal, L., Novotný, R., et al. (2018). Quantifying Carbon and Nutrient Input from Litterfall in European Forests Using Field Observations and Modeling. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 32 (5), 784–798. doi:10.1029/2017GB005825

Nieminen, M., Piirainen, S., Sikström, U., Löfgren, S., Marttila, H., Sarkkola, S., et al. (2018). Ditch Network Maintenance in Peat-Dominated Boreal Forests: Review and Analysis of Water Quality Management Options. Ambio 47 (5), 535–545. doi:10.1007/s13280-018-1047-6

Nieminen, M., Sarkkola, S., Tolvanen, A., Tervahauta, A., Saarimaa, M., and Sallantaus, T. (2020). Water Quality Management Dilemma: Increased Nutrient, Carbon, and Heavy Metal Exports from Forestry-Drained Peatlands Restored for Use as Wetland Buffer Areas. For. Ecol. Manag. 465, 118089. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118089

Normand, A. E., Turner, B. L., Lamit, L. J., Smith, A. N., Baiser, B., Clark, M. W., et al. (2021). Organic Matter Chemistry Drives Carbon Dioxide Production of Peatlands. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48 (18), e2021GL093392. doi:10.1029/2021GL093392

Nugent, K. A., Strachan, I. B., Roulet, N. T., Strack, M., Frolking, S., and Helbig, M. (2019). Prompt Active Restoration of Peatlands Substantially Reduces Climate Impact. Environ. Res. Lett. 14 (12), 124030. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab56e6

Ojanen, P., Minkkinen, K., Alm, J., and Penttilä, T. (2010). Soil-atmosphere CO2, CH4 and N2O Fluxes in Boreal Forestry-Drained Peatlands. For. Ecol. Manag. 260 (3), 411–421. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.04.036

Ojanen, P., and Minkkinen, K. (2020). Rewetting Offers Rapid Climate Benefits for Tropical and Agricultural Peatlands but Not for Forestry‐Drained Peatlands. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 34 (7), e2019GB006503. doi:10.1029/2019GB006503

Pauleta, S. R., Dell’Acqua, S., and Moura, I. (2013). Nitrous Oxide Reductase. Coord. Chem. Rev. 257 (2), 332–349. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.026

Petrone, R. M., Waddington, J. M., and Price, J. S. (2001). Ecosystem Scale Evapotranspiration and Net CO2 Exchange from a Restored Peatland. Hydrol. Process. 15, 2839–2845. doi:10.1002/hyp.475

Plante, A. F., Stone, M. M., and McGill, W. B. (2015). “The Metabolic Physiology of Soil Microorganisms,” in Soil Microbiology, Ecology and Biochemistry. Editor E. A. Paul. Fourth Edition (Academic Press), 245–272. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-415955-6.00009-8

Purre, A.-H., Penttilä, T., Ojanen, P., Minkkinen, K., Aurela, M., Lohila, A., et al. (2019). Carbon Dioxide Fluxes and Vegetation Structure in Rewetted and Pristine Peatlands in Finland and Estonia. Boreal Env. Res. 24, 243261.

Purre, A. H., Ilomets, M., Truus, L., Pajula, R., and Sepp, K. (2020). The Effect of Different Treatments of moss Layer Transfer Technique on Plant Functional Types' Biomass in Revegetated Milled Peatlands. Restor Ecol. 28 (6), 1584–1595. doi:10.1111/rec.13246

Putkinen, A., Tuittila, E.-S., Siljanen, H. M. P., Bodrossy, L., and Fritze, H. (2018). Recovery of Methane Turnover and the Associated Microbial Communities in Restored Cutover Peatlands Is Strongly Linked with Increasing Sphagnum Abundance. Soil Biol. Biochem. 116, 110–119. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.10.005

Reay, D. S., Smith, K. A., and Edwards, A. C. (2004). Nitrous Oxide in Agricultural Drainage Waters Following Field Fertilisation. Water Air Soil Pollut. Focus 4 (2), 437–451. doi:10.1023/B:WAFO.0000028370.68472.d2