- 1Architectural Design, Modeling, and Fabrication Lab, Department of Architecture, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

- 2Department of Art Studies, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

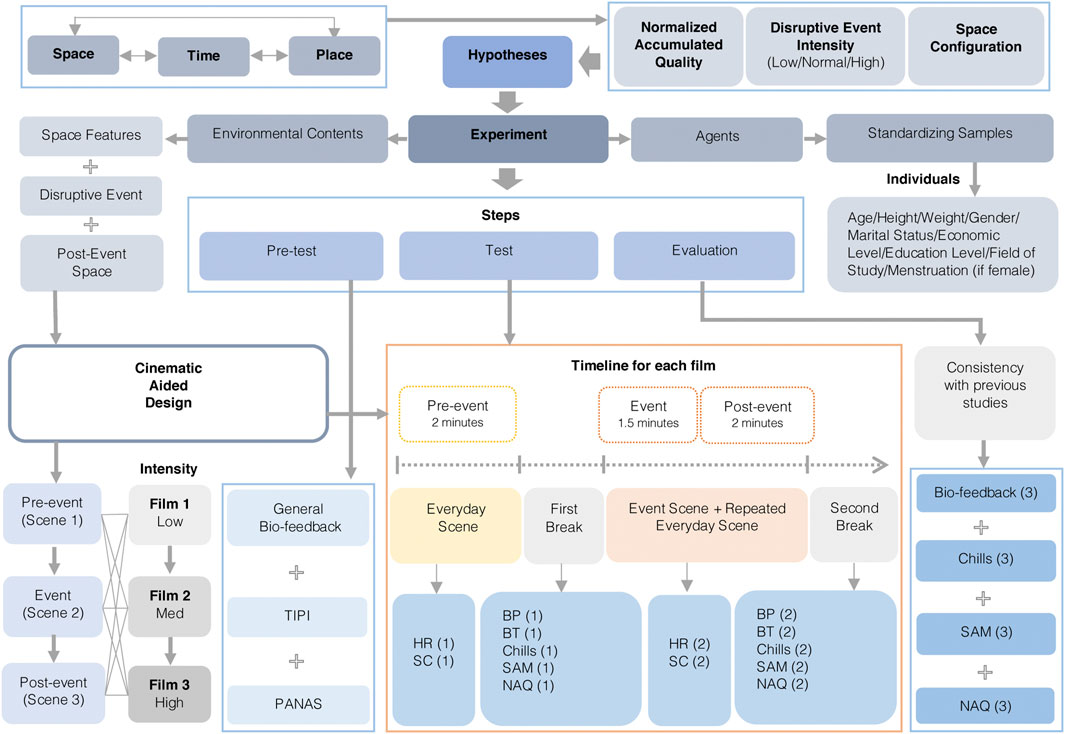

Objectives: Converging architecture with cinema and cognition has proved to be a practical approach to scrutinizing architectural elements’ significant contribution to engineering science. In this research, a behavioral analysis has been conducted to examine if disruptive events in cinematic spaces can lead to an insightful perception of architectural qualities and enhanced interplay with the observed spaces to highlight mental health and improved cognitive tasks in sustainable design characteristics.

Methods: The experiment was conducted in participants (N = 90) while watching three films with different stimuli to facilitate multivariate analyses. The HR, BP, SCL, and BT were measured while screening films to subjects. Psychological assessments of PANAS, TIPI, Chills, Pleasure, Arousal, Dominance, and NAQ were gathered to conduct correlation and regression analyses between variables. An independent space syntax analysis of film plans was also performed to compare film spaces’ properties.

Results: Analyses show that physiological responses of HR, BP, SCL, and BT showed a meaningful relationship with the event intensity. Psychological assessments of Chills, SAM, and NAQ also depicted a meaningful relationship with the degree of stimuli during the movie screenings. Regression analyses illustrated that the age factor had a significant relationship with Arousal (p-value = 0.04), Chills (p-value = 0.03), and Dominance (p-value = 0.00). The TIPI factor showed a meaningful relationship with Chills (p-value = 0.03) and Dominance (p-value = 0.00). PANAS PA factor’s relationship was significant on Chills (p-value = 0.00), Arousal (p-value = 0.04), and Dominance (p-value = 0.03), and the PANAS NA factor showed a meaningful relationship with Chills (p-value = 0.00) and Dominance (p-value = 0.05). The correlations in Chills–Arousal (p-value = 0.01), PANAS NA–TIPI (p-value = 0.01), NAQ–Pleasure (p-value = 0.05), and Arousal–Dominance (p-value = 0.00) were significant. Space syntax analyses also showed that film 3 had a mixed plan structure than the other two films. Factors such as area compactness, connectivity, visual entropy, controllability, and mean depth were influential in distinguishing film spaces.

Conclusion: It has been concluded that the space with intensive disruption of architectural elements successfully indicated improved cognitive perception of spatial qualities, enhanced interaction, and signified sustainable design criteria. Evoking events disrupted the banalization of cinematic spaces, illustrating that the designed model can indicate a more homogenous evaluation of a sustainable environment.

1 Introduction

Architecture has been studied in multiple discussions to integrate with the cinematic art form in design (Vidler 1992). A cinematic context can be a proper solution to analyze the human interaction in space and time that reveals physical habits (Upton 2002), especially because moving images work directly with emotional-affective traits (Pallasmaa 2007b; Pallasmaa 2007a). The emotional-affective assessments in a cinematic context can be surveyed through the disruption of the monotonous rhythm of everyday life followed by the occurrence of evoking “events.” This helps to reach a holistic perception of architectural qualities and transform the ignorance of space banality that affects spatial perception (Penz 2017). Recalling these events, interpretations, and evaluation procedures determines self-cognitive activity (Jokić-Begić 2008). Hence, focusing on the multi-dimensional field of environmental design and space cognition can enhance people’s quality of life and fulfill the long-term sustainable design in everyday life. In sustainable development, the socially perceived surrounding world is a crucial discussion to address mental health in human-environment cognition and behavior, leading to improving human cognition and social communication with space confrontations.

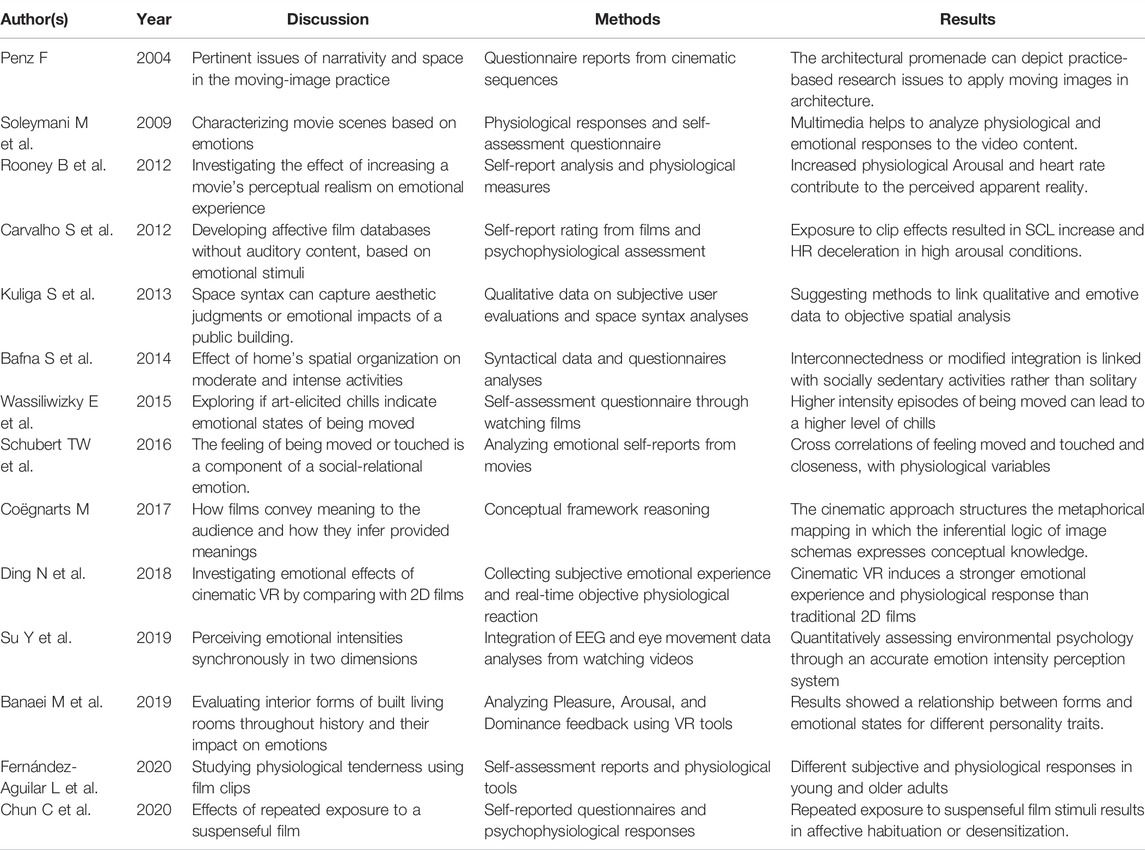

Multiple researchers examined the impact of film spaces on cognitive behavior and emotional responses (Table 1). Still, no significant research has integrated holistic qualitative psychological data with quantitative biofeedback, space syntax analyses, and architectural quality assessments to conclude if spatial stimuli in films can enhance spatial cognition to fulfill sustainable design criteria. While human beings are constantly experiencing different moments at different times in their lives (Sakhaei 2020), perceiving the physical and natural world is crucial for environmental communication (Akerlof et al., 2022). Within this communication, architectural characteristics of built environments can positively or negatively affect mental health (Love et al., 2010; Dzhambov et al., 2018; Andargie and Azar 2019; Hoisington et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021), a crucial factor to reach a sustainable design thinking. In this research, a conceptual framework is designed from architectural space characteristics, cognitive emotions, and film theories to indicate behavioral responses to stimuli in home places that have been strongly affiliated with cognition in previous discussions (Freud 1966; Nin and Stuhlmann 1966; Bachelard 1969; Colman and Colman 1971; Cooper 1974; Chandler 1991). Also, an integrated method is conducted to elicit emotion from film screenings to capture physiological responses, space configurations, and quality measurements to analyze expressive space qualities toward sustainable criteria.

1.1 Cognitive Emotions and Environmental Events

The human mindset is actively developed to create models for perception, information processing, recalling, and interpreting input data (Reinecke et al., 1996). Environmental stimuli also have influenced perception through the brain’s data processing which involves noticing, interpretation, memory, and evaluation (Musa and Lépine 2000). People’s root beliefs first influence these cognitive processes about themselves, the world, and the future (Guidano and Liotti 1983; Ingram 1984; Segal 1988; Hammen and Goodman-Brown 1990).

Emotions from stimulus confrontations are specific neuropsychological phenomena formed by natural selection that organize and create physiological, cognitive, and functional patterns (Plutchik 1980; Izard 2013). They can be measured in three different mental and physiological reactions (Wundt 1922; Lang 1969), later developed as Pleasure, Arousal, and Dominance (Mehrabian 1996). Pleasure indicates a willingness to a stimulus, while sadness shows a tendency to retreat and escape. Arousal shows the level of strength in the behavioral choice related to the intensity of that stimulus (Bradley and Lang 1994). Dominance measures environmental limitations in the case of expressing actions and behaviors (Bakker et al., 2014). Any degree of low Pleasure brings about disharmony and inconsistency in the environment (Bakker et al., 2014).

Conversely, extreme Pleasure also leads to the same result because people become dull and bored following a lack of challenge (Soesman 2005). The same procedure applies to the arousal level where individuals tend to feel sleepy from low Arousal and extremely disturbed from a high stimulus intensity (Kandel et al., 2000), especially because a low degree of order simulates a chaotic situation, while too much order represents hardness (Schneider 1987). A low degree of diversity causes slowness and depression, whereas a higher level would bring excessive stimulation. As explained, the normalized middle region of the evaluation of mental and emotional states can be interpreted as routine everyday life, constant ordinariness, or banality. If people move away from the banal area, they witness events and stimuli, and therefore, their level of satisfaction and feeling affected by environmental characteristics changes proportionally (Bakker et al., 2014). Consequently, positive emotions will notice pleasant aspects, whereas those with negative emotional traits remember unpleasant dimensions (Rusting 1998).

1.2 Cinematic Space Cognition and Emotion

While films promote spatial understanding by observing the practice of space (Penz 2017), their extracted data can analyze architecture creatively (Neumann 1999). People who watch these scenes can be termed as architects who focus on building details to feed their visual memory (Bala 2014). Evoking attention by showing films activates the motor system and embodiment as the emotional–motivational state is linked with cognitive processes in human–environment interactions from a sensory-cognitive structure (Izard 2013). Hence, the activation of the motor system leads to imagination and perception (Prinz 2005). In addition, environmental feelings that activate sensory cues are closely related to embodied processes (Coëgnarts 2017). The mind creates a mental path to perceive the space, and by exploration, similar to genuine experience, it forms a mental organization and processes the discovery like film sequences (Ghahramani et al., 2015). As a result, the comparison between the film space and physical environments can signify space qualities to the design process to boost the experience in designing a more interactive and sustainable place.

In an architectural space, experiences are gradually revealed in time as the mind constantly predicts what will happen in that specific place (Roudavski and Penz 2003) which requires movement. Bergson (1911) separated cinematic movement into real and false; the latter explains the illusion of movement in space made by a sequence of images stored in memory. He believes that movement does not induce a holistic perception of time but instead offers multiple fragments of a period interpreted as spatialized time. Comparably, Deleuze (2020) argues that the result of a pure visual moving image is a unique projection of time images. In the movement image, time is measured by the physical movement, which is construed as haptic, meaning tactile and physical. On the other hand, the moving image is related to seeing in the time image, interpreted as optical (Cairns 2016). Both Bergson and Deleuze confirm that the process of cognitive interference with moving images bonds space and time in an illusional or false movement that relies on both optical and haptic engagement.

1.3 Everyday Life Versus Disruptive Event in Film Spaces

Observing the practice of film spaces divided into everyday ordinary and event-based scenes creates a cyclic rhythm together, which Lefebvre interprets as rhythm analysis. He articulates that the everyday space is different from the geometric space. It contains four dimensions: accomplished, foreseen, uncertain, and unforeseeable, representing past, present, short-term future, and long-term future, respectively (Lefebvre 2013). Incorporating everyday space and dramatic events collectively enhances the expressive narrative space to reach a unique form of interaction with moving images (Nitsche et al., 2002). Films offer an exceptional experience in heterotopic spaces to help the observer distinguish them from quotidian ones (Penz 2017). Likewise, the architectonics of elements will directly affect emotional experiences and personality traits that play a vital role in assessing space and related emotional indicators (Gifford 2007). In addition, elements’ type, angle, scale, and location influence emotional behavior and visual properties (Kent et al., 2021). Beyond their geometrical properties, factors such as color, light, and material of the interior space will have the same impact on viewers (Banaei et al., 2020), leading to an accurate design approach for a sustainable space. To activate memory and emotions in this experiment, choosing home spaces to induce a sense of a place that feels private, protected, and is a psycho-social space (Bala 2019) would be practical to measure psychophysiological assessments.

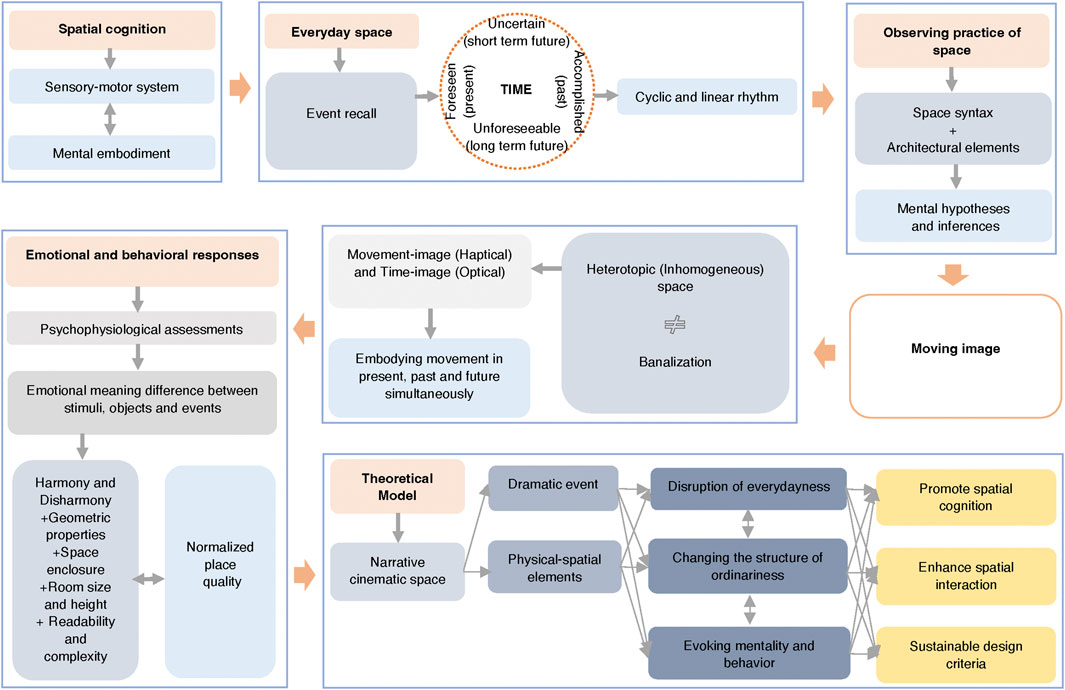

Based on the literature review and conceptual framework, three main hypotheses are expressed to be measured: 1) Implementing dramatic events in a narrative cinematic space-time, which leads to the disruption of everydayness, can enhance spatial cognition. 2) A dramatic event is the most critical factor in changing the structure of everyday life and thus promoting space interactions. 3) Developing a model based on physical-spatial elements affecting the change of mentality and behavior under personality traits, experiences, and mental and historical backgrounds leads to the criteria to design an optimal and sustainable environment (Figure 1).

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Population and Sampling Method

Ninety participants with Iranian ethnicity (45 male, mean age 26, SD 2.69, and range 20–30 years old) were selected for this experiment and reported as students or employed. As socio-cultural aspects of human personality, such as past spatial experience, affect assessments (Khaleghimoghaddam and Bala 2018), the age range of 20–30 was chosen to control the experiment. While the user’s sensitivity is highly reliant on the environmental exposure impact (Dijkstra et al., 2008), we tried to achieve more homogeneous behavioral and physical characteristics than adolescents or elderly demographics whose potential differences in past experiences could have affected the responses. While we preferred gender equality to control psychophysiological responses, we also ensured that none of the participants had watched the films before to bring a novel and fresh experience of observation. Each participant was informed about the entire psychophysiological measurements during pre-test preparation. They were pre-evaluated as being healthy with no mental or physical trouble while reporting they had a night of sufficient sleep and a proper meal before the test day. They were also asked to avoid smoking, drinking alcohol, and consuming caffeine-containing food or beverage at least 4 h before the experiment. Additionally, they were asked if they were under any medication. The experiment protocol was validated by the department of physiology at Tarbiat Modares University and performed under the ethical standards as proposed in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

2.2 Editing the Cinematic Experiment

We selected three films in the cinematic test model by examining several criteria. The first crucial criterion was the films’ space narration ability, meaning that the screened space and architectural details should solely impress the audience and gather their attention without using a screenplay or scenario. The second factor addressed a disruptive and evoking event in each film space. By eliminating the role of the script in each clip, architectural qualities could potentially affect the audience’s perception of the space by avoiding the implementation of stories and dialogues. To facilitate these two criteria, we tried to choose specific scenes wherein the camera angle has a continuous movement as a one-point perspective in the edited clips. Specifically, the formal film analysis system (Bordwell et al., 1993) was studied to choose standard scenes for this specific experiment. The camera height and angle were selected from eye-level view perspective scenes and point-of-view shots that seemed like the participants were exploring the space themselves. A disruptive event in the middle of the everyday depicted spaces helped to choose films with different intensities of space deconstruction by placing each film from less disruptive to more disruptive, respectively. The element of ‘stimulus’ in the middle of two everyday space scenes increased from the first film to the third one to bring an ascending impact on the emotional feelings of the participants.

Thus, three films with an approximate duration of 5 min each were selected as the test model. The first and last 2 min of each film narrate the familiar home atmosphere, while the middle 1:30 min depict the beginning of the evoking events of that space. As mentioned previously, the house space was chosen to represent the most lived, private, and connected place to the human mind. Participants first watched the beginning scene to immerse themselves in the narrative space and architectonics. Then, the middle of the film is dedicated to the event screening wherein some of the same elements and details from the ordinary scene were destroyed. In the third or final part of each film, participants were confronted with the same everyday scene from the first 2 min to assess their cognitive perception and emotions while remembering the event that had evoked their emotional perception. Participants’ perceptions and feelings were assessed by filling out two psychological questionnaires before the start of the screening of the films as a baseline pre-test assessment and another three questionnaires during the screening of the films.

2.2.1 Films’ Plot Summaries

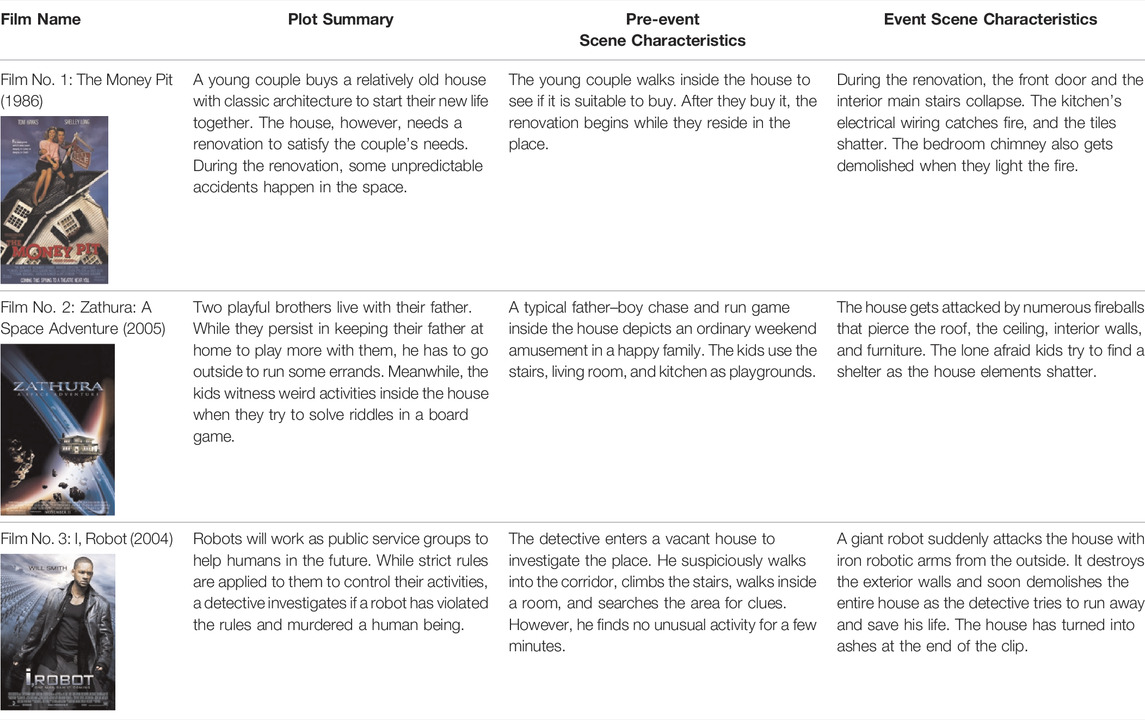

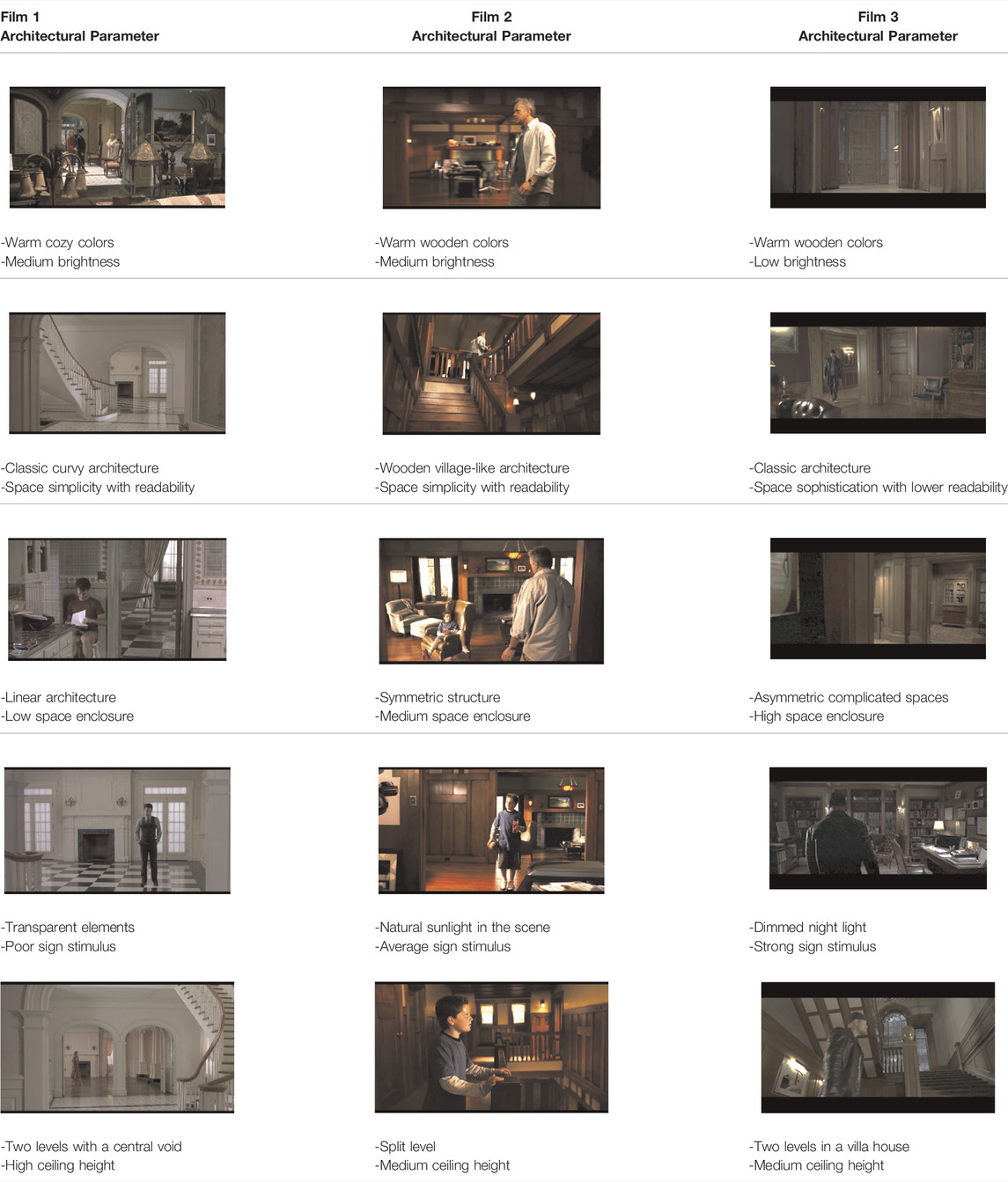

The three films’ plot summaries and related events are depicted in Table 2. Accordingly, the films’ architectural parameters are illustrated in Table 3.

2.3 Data Collection of Biofeedback and Psychological Measurements

Data collection during the experiment was accomplished using multiple questionnaires and tools that indicate physiological changes in the human body while watching movies between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. in the same room and condition with 25°C temperature. Five standard questionnaires were provided in paper and pencil format for psychological and emotional analyses: TIPI (Gosling et al., 2003) to assess personality traits that reflect internal characteristics of the participants, PANAS (Watson et al., 1988) to measure the two dimensions of human mood, namely, negative emotion and positive emotion, Chills (Silvia and Nusbaum 2011) to examine how often people experience aesthetic chills and related states while engaging with films, SAM (Mehrabian and Russell 1974; Bradley and Lang 1994) to assess Pleasure, Arousal, and Dominance as three independent emotional characteristics to describe individuals’ feelings, and NAQ (Zawidzki 2016) which is based on geometrical characteristics of an architectural space plan to reach the human subjective evaluation while the assessment is mainly related to the spatial perception of a space rather than its aesthetic properties. Before the film screening, the TIPI and PANAS questionnaires assessed general personality traits and emotional conditions in a resting situation. As participants spent a few minutes in the test-taking environment to ensure they had a relative sense of relaxation, we asked them to pay attention to architectural details and properties since they had been informed that the entire experiment relates to the spatial assessment. After completing TIPI and PANAS questionnaires, participants sat in front of a 15-inch laptop with a loudspeaker to watch the clips. Right after the ordinary everyday scene screening and before beginning the disruptive event scene, the film screening was paused. Then, participants were asked to complete the Chills, SAM, and NAQ questionnaires for the first scene. Upon completing the first three questionnaires, the evoking disruptive event scene alongside the everyday scene (the exact scene which was screened at the beginning of the test) was shown without a pause between them. This time, participants were again asked to fill out the Chills, SAM, and NAQ tests for the second time based on observed events. Thus, the evoking effects that events in the middle of the two identical everyday scenes provoked would affect how people respond to the repeated questionnaires. As a result, data were gathered in two different phases: pre-event and post-event, with two thoroughly similar scenes but the latter one affected by an emotional and cognitive stimulus. This procedure was performed in other films as the participants were divided into three thirty-person groups for each clip. We performed linear regression analyses to capture the effects of general personality traits and positive or negative affect scales on Chills, SAM, and NAQ. We also conducted a Pearson’s correlation coefficient test to evaluate the association between variables. p-values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

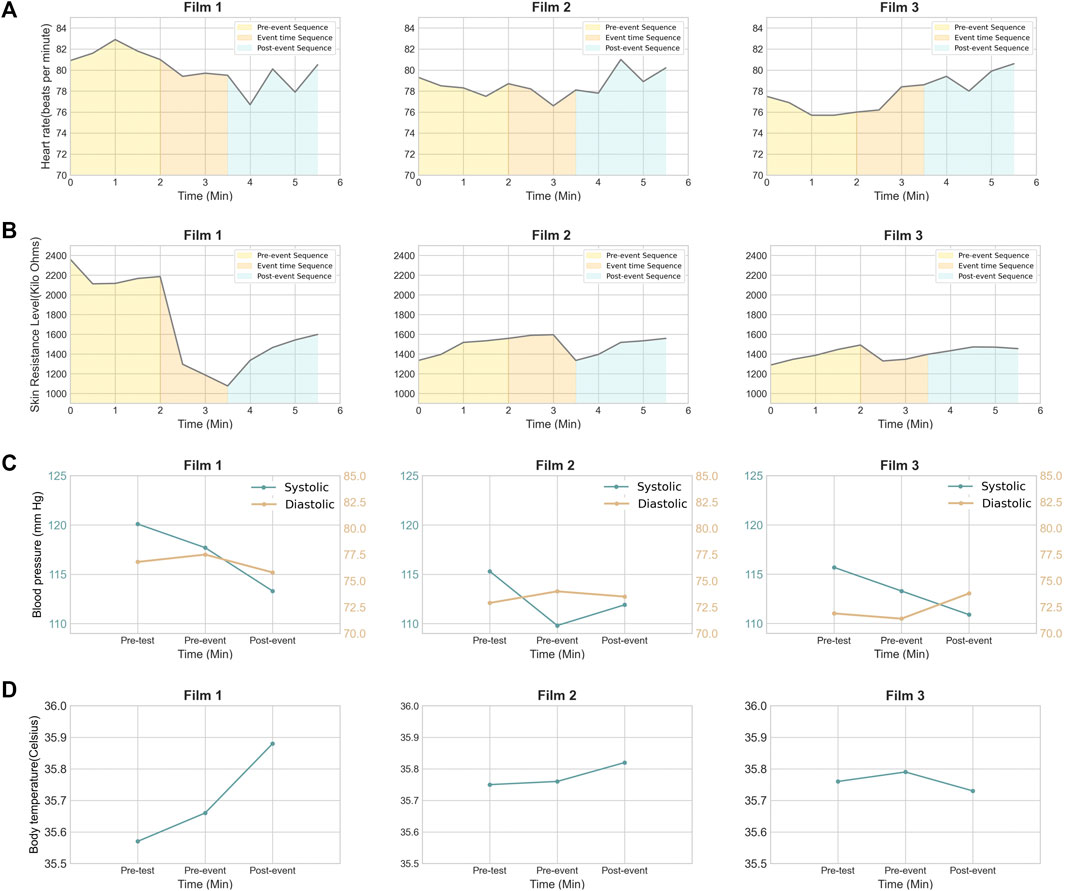

In this test, the four indicators of the HR (bpm), SRL (kilo-ohm), SBP and DBP (mmHg), and internal BT (Celsius) were measured during the film screening. The Apple Watch Series 2 was attached to the left wrist for real-time heartbeat recordings during the screening. The Sanwa PC5000A digital multimeter was conducted to measure sweating on the palm surface of the hand related to SRL, which has an inverse ratio with SCL. Because the palm holds nervous sweat glands, two Skintact F-55 chest leads were attached next to each other to the palm surface with the digital multimeter’s electrodes attached to the chest leads. Watching evoking scenes leads to a resistance change between two electrodes because of sweating caused by nervous system activities. The SRL measurement procedure was the same as HR data collection. To measure BP, the Beurer BM 60 Blood Pressure Monitor was used to measure the SBP and DBP three times for each movie: before each movie screening in resting mode, right after the screening of the everyday scene, and the last time right after the end of each film. The BT-A11CN digital thermometer was conducted three times for each movie with the same procedure as recording BP. Hence, four physiological responses were analyzed by examining the average statistical data for all participants in each period recorded before and after the events and evaluated from the report timeline. The effect of time in habituation or desensitization feelings was also analyzed because of physiological changes throughout the scenes and the considerable duration of time to screen three films (Figure 2).

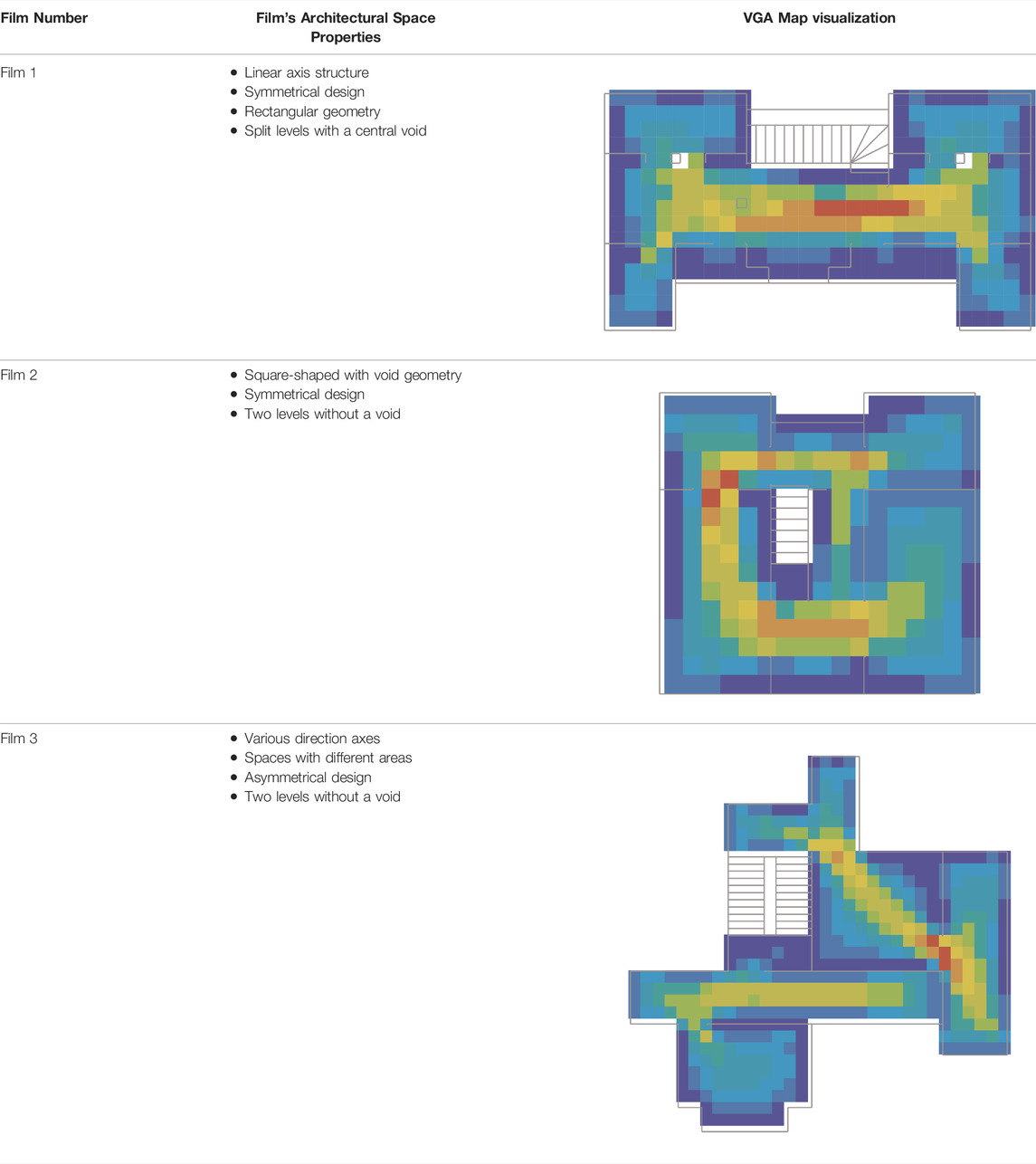

2.4 Analyzing the Structure of the Cinematic Space

The space syntax was used to derive architectural characteristics of film spaces from quantitative space analysis. Turner et al. (2001) introduced visibility graph analysis to examine positions in an environment by computing the intervisibility of positions distributed across the entire space (Franz and Wiener 2005). The UCL Depthmap’s VGA generated a grid map from each of the three film plans to perform the VGA analysis.

2.5 Data Normalization and Fuzzy Scaling

The two-valued account of scientific truth does not correspond to scientific facts, especially because science in all dimensions, including ambiguous, indefinite, graded, and multi-valued attributes, has a fuzzy truth (Ragin 2009; Arabacioglu 2010). Fuzzy logic depends on reasoning with fuzzy sets (Kosko and Toms 1994; Yeganeh and Kamalizadeh 2018) and represents the type and amount of membership. It extends the two-value space of zero and one to the three-value space of zero, one, and a half. Consequently, the types and amounts of membership can be defined as fuzzy membership. In the fuzzy logic, everything is relatively graded (Casco 2013; Yeganeh 2020), and the truth is between zero and one. Ragin determines the fuzzy degrees of the concepts based on different values. Fuzzy degrees represent verbal labels of 0.01–0.047 for Mostly in, 0.047–0.119 for Degree of membership is more in than out, 0.119–0.378 for Cross-over point, 0.378–0.5 for Degree of membership is more out than in, 0.5–0.622 for Mostly out, 0.622–0.881 for Mostly in, and 0.881–0.99 for Degree of membership is more in than out. The membership function of classical and fuzzy sets is expressed as the following formula:

The fuzzy set A with a membership function

3 Results

As illustrated in the method section, we performed a linear regression analysis between variables. To normalize each dataset in analyses, we have scaled every variable on a fuzzy scale to be adjusted and comparable in zero and one intervals.

3.1 Physiological Responses

3.1.1 Heart Rate

With the highly intense disruptive event, a significant change and effect on the HR and a noticeable increase were witnessed (Figure 3A), supporting previous studies (Ekman et al., 1983; Sinha 1996; Prkachin et al., 1999; Kreibig et al., 2007; Ding et al., 2018; Fernández-Aguilar et al., 2020) and reflecting a potential for emotional valence (Greenwald et al., 1989; Lang et al., 1993; Gruber et al., 2015). On the contrary, when the intensity was low, the HR had almost a descending trend, demonstrating that the increase or decrease in the HR in the post-event was directly related to the intensity level. In other words, participants’ susceptibility to perceive the post-event observed space was significantly high, meaning that the disruptive event remarkably evoked cognitive activity and emotional Arousal, as discussed previously (Lang et al., 1995; Bolls et al., 2001; Bradley et al., 2001; Ravaja 2004). Still, with a deceleration in the HR reported in similar studies (Bradley 2009; Carvalho et al., 2011, 2012; Deng et al., 2017; Kimura et al., 2019), HR reports need more specific interpretations. During the pre-event, participants did critically involve in space narratives as no significant HR changes were observed, meaning that the films’ stimulus contents had a prominent role in spatial perception (Deng et al., 2017).

FIGURE 3. Physiological reports for (A) Heart rate, (B) Skin resistance level, (C) Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and (D) Body temperature from pre-test to pre-event, event-time, and post-event scenes in the three films. Python graphs.

3.1.2 Blood Pressure

In film 1, SBP and DBP (Figure 3C) correlated with a declining steep slope trend, consistent with a previous study (Mrug et al., 2015). In film 2, SBP increased with a moderate slope, and conversely, the DBP decreased with a slow gradient. In film 3, SBP decreased with a steep slope while DBP with an average slope showed an increasing trend. It can be said that DBP was directly related to the event intensity. In other words, DBP increased significantly with increasing deconstruction severity. However, no significant effect was reported for SBP, consistent with previous reports (Mrug et al., 2015).

3.1.3 Skin Resistance Level

There was a significant relationship between the event intensity and SRL; as the intensity increased, the SRL changed slightly and vice versa (Figure 3B). Changes in trends during films’ screening also showed a significant correlation with changes in the SRL. In film 1, at the beginning of the event in a short period, SRL decreased and gradually began a gentle ascending trend. Then, with a gradual increase in event intensity, the SRL witnessed a descending trend, as reported previously (Kunzmann and Grühn, 2005; Carvalho et al., 2011, 2012; Kimura et al., 2019; Fernández-Aguilar et al., 2020; Zickfeld et al., 2020). The SRL trend supports previous discussions that more sweating on the palm surface can indicate more arousal (Cuthbert et al., 2000; Soleymani et al., 2009; Korpal and Jankowiak 2018). The post-event SRL in film 1 showed a different trend with a steep ascending slope. The diagrams in films 2 and 3, where the intensity was higher, illustrated an almost identical trend to film 1’s chart in both pre-event and post-event.

3.1.4 Body Temperature

The graphs show that BT increased in all three films in the intervals between pre-test and pre-event (Figure 3D). The stimuli effects on fluctuations in BT provided a different pattern (Šolcová and Lačev 2017), in which a more intensive event caused a drastic decrease in BT, as reported in similar studies (Ekman et al., 1983; Sinha 1996; Kistler et al., 1998; Prkachin et al., 1999; Kreibig et al., 2007; Yoshihara et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2018). Also, the moderate event raised BT relatively, whereas the low-intensity event increased BT sharply. However, other studies reported a converse and debatable increase in similar experiments on skin temperature (Zickfeld et al., 2020).

3.2 Stimulus-Affected Self-Assessments

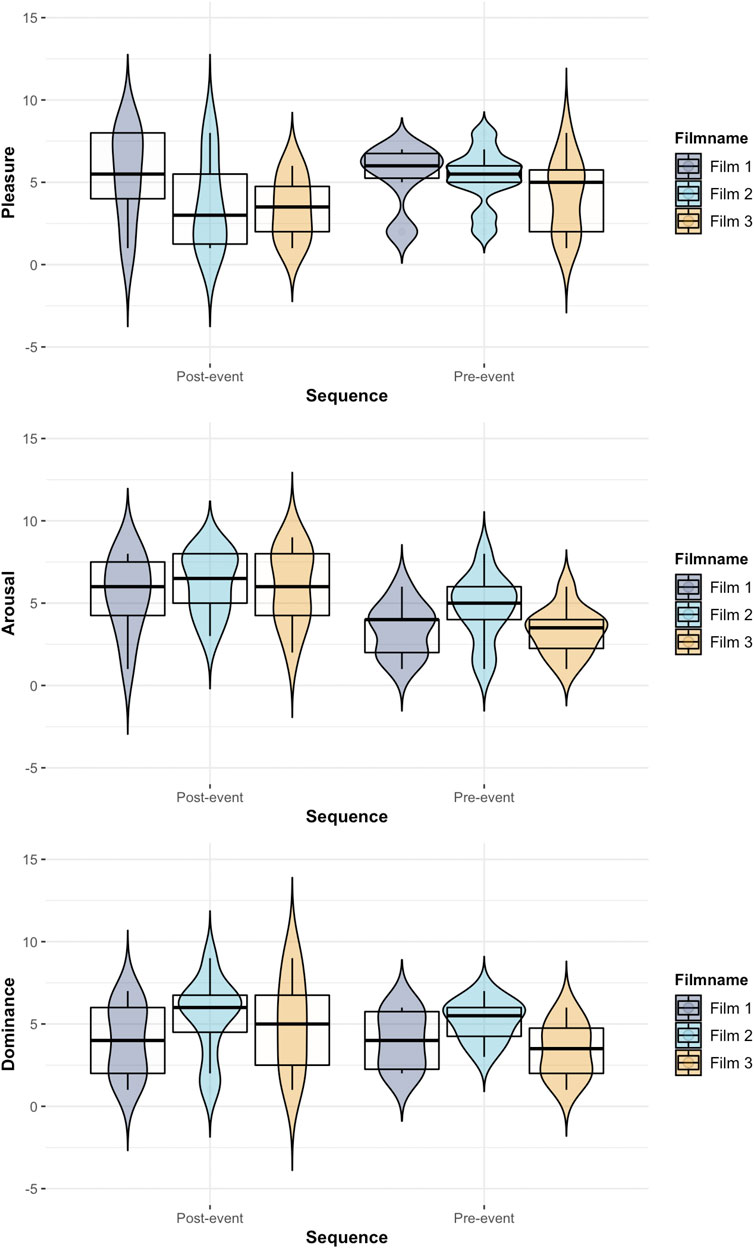

3.2.1 Pleasure, Arousal, and Dominance

Before the event, participants’ feelings about Pleasure were almost the same for films 1 and 2, and responses overlapped with each other following similar reports. In contrast, in film 3, Pleasure responses were distributed in a more extensive range (Figure 4). After the event, a significant difference in all three films reported for Pleasure, in which the average Pleasure for film 1 in the post-event was almost equal to the pre-event. However, there were broad changes in feelings per participant, showing that the distribution of data in the plot was less homogeneous. In film 2, the average Pleasure was significantly reduced alongside uniformity in data distribution. In film 3, despite the decrease in the average of Pleasure, participants’ opinions about space became closer, revealing that the disruptive event in space notably decreased Pleasure, which was reported previously in a similar discussion (Soleymani et al., 2009).

FIGURE 4. Psychological responses for Pleasure, Arousal, and Dominance responses for the three films between pre-event and post-event conditions. R ggplot2 graphs.

Changes in Arousal and Dominance patterns before and after the event illustrated a direct relationship with the event intensity. The higher the intensity, the greater was the amplitude of Arousal and Dominance oscillations (Figure 4). Arousal was directly related to the event intensity due to the increase in the post-event under all three films’ events, showing consistency with previous discussions (Schupp et al., 2004; Kimura et al., 2019). Dominance showed an ascending trend with increasing event intensity, as previously reported (Carvalho et al., 2012; Deng et al., 2017), with a moderate slope. Still, Dominance requires specific evaluation to see if participants rated the stimulus itself or the subjective feeling it elicited (Bradley and Lang 1994). In addition, the pre-event Arousal had an ascending trend from films 1 to 3, respectively, while film 2 produced higher Arousal and Dominance than the other two films.

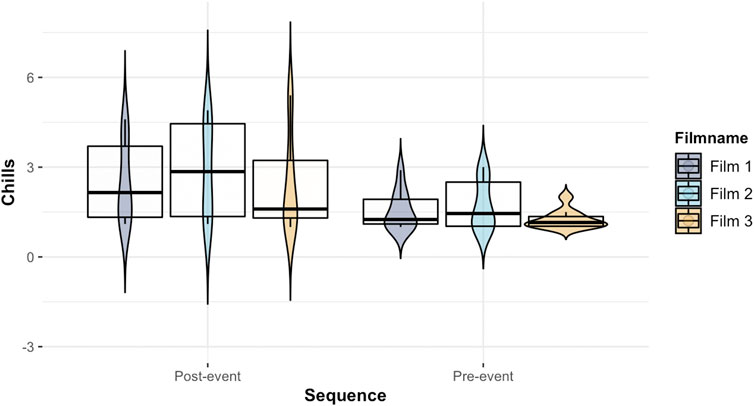

3.2.2 Chills

Chills were among the variables most affected by the event (Figure 5). The Chills rate was almost the same during the pre-event for the three films. Although the distribution of plot data for film 3 had been more scattered and film 1 had relatively robust data, film 2 showed a more extensive data distribution. In the post-event, Chills showed a significant increase while the data distribution was out of uniformity and placed in much larger intervals. Thus, Chills validated a substantial relationship with the event intensity, as reported previously (Schubert et al., 2018; Bannister 2019). With an increase in space deconstruction, Chills increased noticeably as well.

FIGURE 5. Psychological responses for Chill's reactions for the three films between pre-event and post-event conditions. R ggplot2 graphs.

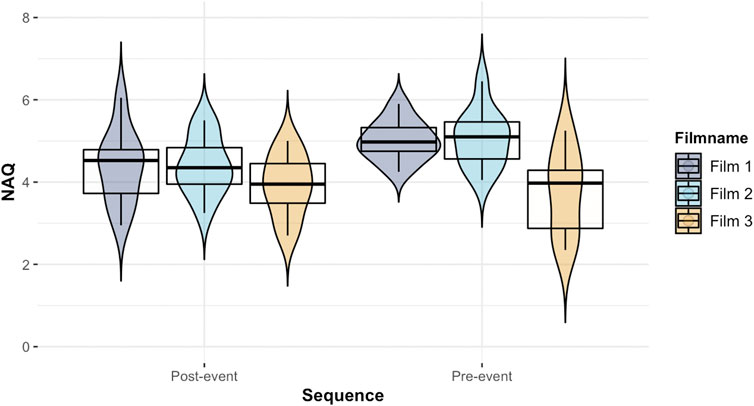

3.2.3 Normalized Accumulated Quality

The NAQ factor for the pre-event in three films indicated that the first and second films’ architectural spaces had a higher normalized quality than film 3 (Figure 6). Also, the audience’s assessment of the place quality was close to each other, and the overlap of responses was high compared to film 3. After the event, the audience’s assessment had undergone significant changes so that the spaces of films 1 and 2 were perceived with the lower quality than the pre-event. In contrast, the film 3 diagram showed almost the same pre-event average quality as the post-event space, with the audience’s views getting closer. Conclusively, the disruptive event reduced the place perception quality and brought participants’ views closer. Apart from lowering the perceived quality, the less intensive event caused a more semantic difference. Hence, the space deconstruction stimulus played a decisive role in reducing the semantic differentiation of the perceived place and the overlap of spatial quality assessments.

FIGURE 6. Psychological responses for NAQ responses for the three films between pre-event and post-event conditions. R ggplot2 graphs.

3.3 Regression Analyses

3.3.1 Age Factor

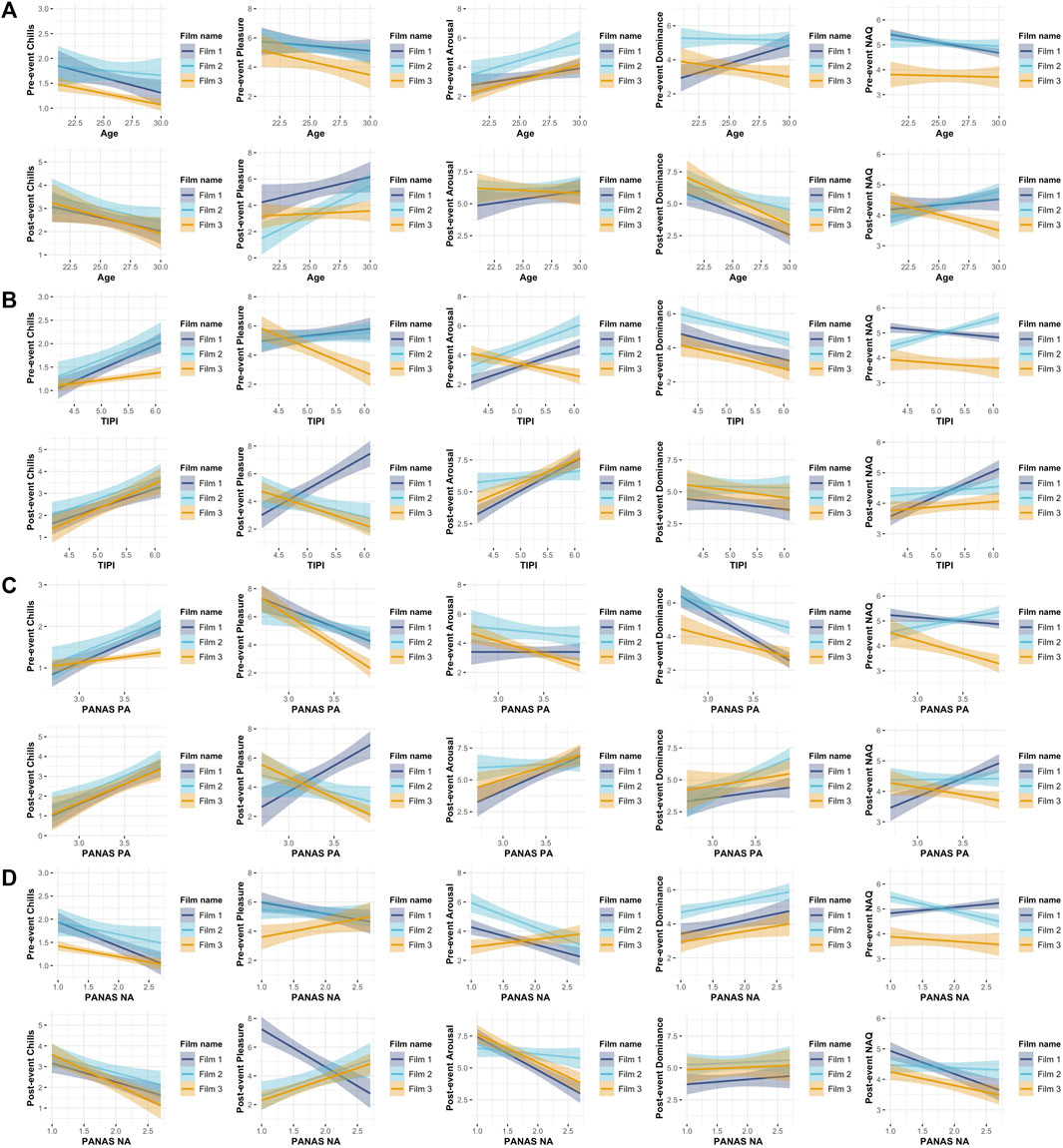

The linear regression graphs showed that age had a significant and positive relationship with Chills, Pleasure, and NAQ. With the increase of age, these parameters decreased linearly (Figure 7A). In contrast, age indicated a positive linear relationship with Arousal (df = 88, f = 8.5, β = 0.3, R2 = 0.09, and PV = 0.04), in which a steep slope increasing of age in all three films followed an increase in Arousal. However, before the event, age did not demonstrate a significant relationship with Dominance (df = 88, f = 0.26, β = 0.05, R2 = 0.03, and PV = 0.61). In the post-event, age showed a significant linear relationship with Chills (df = 88, f = 4.9, β = -0.23, R2 = 0.05, and PV = 0.03) with a descending slope and also a steep slope and negative linear relationship with Dominance (df = 88, f = 12.7, β = -0.36, R2 = 0.13, and PV = 0.00). Thus, with age growth, Chills and Dominance decreased significantly after the event. Age also had a significant positive linear relationship with Arousal with a moderate slope (df = 88, f = 0.26, β = 0.05, R2 = 0.01, and PV = 0.61). In general, it can be argued that the increase of the event intensity brought about a steeper slope in plots.

FIGURE 7. Regression of Chills, Pleasure, Arousal, Dominance, and NAQ with (A) Age, (B) TIPI, (C) PANAS PA, and (D) PANAS NA in both pre-event and post-event conditions for the three films. R ggplot2 graphs.

3.3.2 Ten Item Personality Inventory Factor

Before the event, the TIPI had a significant positive linear relationship with Chills (df = 88, f = 15.08, β = 0.38, R2 = 0.15, and PV = 0.04) and showed consistency with previous research (Panksepp and Bernatzky 2002; Silvia and Nusbaum 2011), as well as a significant linear relationship with Dominance (df = 88, f = 7.6, β = 0.28, R2 = 0.08, and PV = 0.14) and a steep slope (Figure 7B). When the event intensity was low or moderate, TIPI depicted a significant linear positive relationship with Pleasure (df = 88, f = 8.1, β = 0.29, R2 = 0.02, PV = 0.04) and Arousal (df = 88, f = 2.6, β = −0.17, R2 = 0.03, PV = 0.00), but as the intensity increased, this relationship appeared in reverse so that the increase of TIPI led to a steep descending slope with both of these variables. In addition, the type of post-event TIPI relationship with Chills (df = 88, f = 0.41, β = 0.07, R2 = 0.05, and PV = 0.14), Pleasure (df = 88, f = 2.97, β = 0.19, R2 = 0.04, and PV = 0.06), and Dominance (df = 88, f = 23.6, β = 0.46, R2 = 0.21, and PV = 0.00) variables was the same as the pre-event situation. However, Arousal increased with a steep slope than the pre-event with the intensity increase.

3.3.3 Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Positive Affect Factor

Before the event, PANAS PA showed a direct linear and significant relationship with Chills, Arousal, and Dominance (Figure 7C). Chills increased following PANAS PA’s ascending trend, but Arousal, Pleasure, and Dominance depicted a decreasing trend following the event intensity’s significant and direct effect. Apart from this, while PANAS PA had a non-uniform effect on NAQ (df = 88, f = 0.58, β = −0.01, R2 = 0.01, and PV = 0.44), based on the intensity and the quality derived from the cinematic architectural space, the increase of PANAS PA reduced the perceived quality of the space when high space quality was reported with normal intensity. Still, when the quality of the cinematic architectural space was moderate and the event intensity was either very high or very low, the NAQ decreased significantly. The effect of PANAS PA in the post-event on Chills (df = 88, f = 24.35, β = 0.47, R2 = 0.22, and PV = 0.00), Arousal (df = 88, f = 8.9, β = 0.31, R2 = 0.1, PV = 0.04), and Dominance (df = 88, f = 4.9, β = 0.23, R2 = 0.05, PV = 0.03) parameters was similar to the pre-event. The effectiveness of PANAS PA after the event was substantially dependent on the intensity. With moderate intensity, Arousal highly increased, whereas with high intensity, Arousal had a steep decreasing trend. Regarding NAQ, it can be understood that with high and extreme event intensity, PANAS PA greatly diminished NAQ, but with low event intensity, PANAS PA significantly elevated NAQ (df = 88, f = 1.18, β = 0.13, R2 = 0.01, and PV = 0.14).

3.3.4 Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Negative Affect Factor

The effect of PANAS NA in the pre-event on Chills (df = 88, f = 9.47, β = 0.31, R2 = 0.09, and PV = 0.03) was significant and linear with a negative slope and directly related to event intensity, which was reported previously (Hanich et al., 2014). In addition, PANAS NA had a significant positive and linear relationship with Dominance (df = 88, f = 0.36, β = -0.06, R2 = 0.1, and PV = 0.04), and accordingly, with the increase of PANAS NA, Dominance increased in proportion to the intensity as well. Similarly, in the post-event, the effect of PANAS NA on Chills (df = 88, f = 17.8, β = -0.41, R2 = 0.17, and PV = 0.00) and Dominance (df = 88, f = 0.36, β = -0.06, R2 = 0.04, and PV = 0.05) parameters was the same with pre-event situations (Figure 7D).

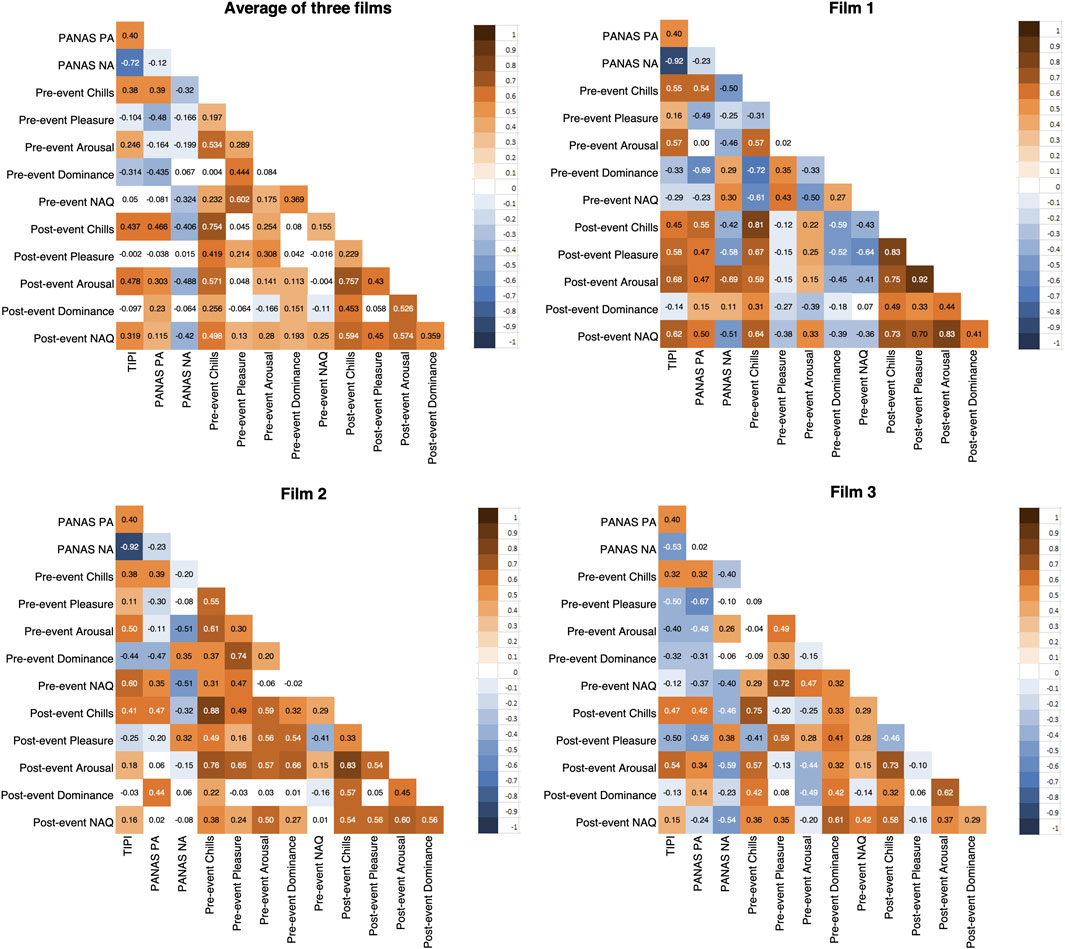

3.4 Correlation Analyses

Examination of correlation diagrams for the three films showed that in general, the highest correlation was related to post-event Chills with post-event Arousal (pc = 0.77 and pv = 0.01) and also pre-event Chills with post-event Chills (pc = 0.76 and pv = 0.02). This correlation shows that feeling chills and goosebumps can be followed by significant arousal when subjects react to a film space stimulus. The highest negative correlation was related to PANAS NA with the TIPI (pc = -0.72, pv = 0.01), illustrating a solid relationship between the negative affect scale with general personality traits. In addition, the correlation between NAQ and Pleasure was positive and significant (pc = 0.28, pv = 0.05), ranging from moderate to high. Before and after the event, the correlation between these two variables was quite substantial and highest in film 1. However, it gradually descended from film 1 to films 2 and 3, illustrating that the correlation decreased with the event intensity. It can be said that participants’ feelings of pleasure from space stimuli show a high relationship with understanding negative space qualities. It should be noted that the degree of correlation between NAQ and Arousal was the same as between NAQ and Pleasure and NAQ and Chills, both in three films’ average and in event intensity. Compared to the NAQ and Dominance correlation, NAQ–Chills and Pleasure–Arousal correlations were quite the opposite. As the intensity increased, the correlation rate increased with the highest rate for film 3. This increase can be another indicator for the role of stimulus-affected space in emotional response to judge the space quality. The correlation between NAQ and TIPI was positive and directional but showed a weak correlation. Still, it showed a significant relationship with the event intensity so that the intensity ascent caused a correlation decrease, and accordingly, TIPI and NAQ showed the highest correlation in film 1. General personality traits may not be accurate indicators of the perceived quality of space in event-based situations.

The correlation between NAQ and PANAS NA was negative but positive with PANAS PA. With PANAS NA increase, the NAQ decreased, and with PANAS PA increase, the NAQ increased. This outcome shows that the normalized space quality is strongly related to the positive or negative affects scale. PANAS PA and PANAS NA showed a constant correlation, while the degree of correlation significantly correlated with the event intensity. The more severe the disruptive event, the closer PANAS PA and PANAS NA got to each other (pc = -0.16, and pv = 0.00), or in other words, the increase in PANAS PA did not have a significant effect on PANAS NA and vice versa. This result can strongly prove that PANAS scales relate to totally different realms in human characteristics. PANAS NA also had a significant negative correlation with TIPI (pc = -0.72 and pv = 0.00). The lower the intensity of the event, the stronger was the negative correlation coefficient between these variables. Also, the intensity reduced the negative correlation coefficient between them.

Conclusively, the event intensity changed the type and degree of correlation between PANAS NA-TIPI and reduced positive and negative correlations. This reduction shows that a severe event may not be a valuable indicator of personality traits and negative affects interrelationships. Chills showed a high positive correlation between the pre-event and post-event (pc = 0.75 and pv = 0.00), indicating the strong relationship between both phases of spaces in films regarding the emotional state of chills and goosebumps. The same type of positive correlation was very low for Pleasure, Arousal, and Dominance. It can be argued for SAM that during the post-event, the correlation in Dominance–Pleasure was very low (pc = 0.16 and pv = 0.03), high in Arousal–Dominance (pc = 0.54 and pv = 0.00), and moderate in Pleasure–Arousal (pc = 0.27 and pv = 0.00), as previously validated in a similar study (Soleymani et al., 2009). This result shows that being dominated by spatial stimuli can be highly related to feeling aroused. Chills demonstrated the highest positive correlation in SAM with Arousal, Dominance, and Pleasure, respectively, both during the pre-event and post-event with a significant rate. This correlation has also been validated previously (Maruskin et al., 2012; Wassiliwizky et al., 2015), showing that emotional goosebumps or chills can highly relate to pleasantness or being aroused or dominated. There was also a positive correlation between SAM in the pre-event but less correlated than the post-event, showing that the event had increased the correlation between SAM factors. Similarly, Chills’ post-event positive correlation with SAM showed a significant ascent (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8. Correlation matrix of psychological responses for the three films in pre-event and post-event conditions. R ggplot2 graphs.

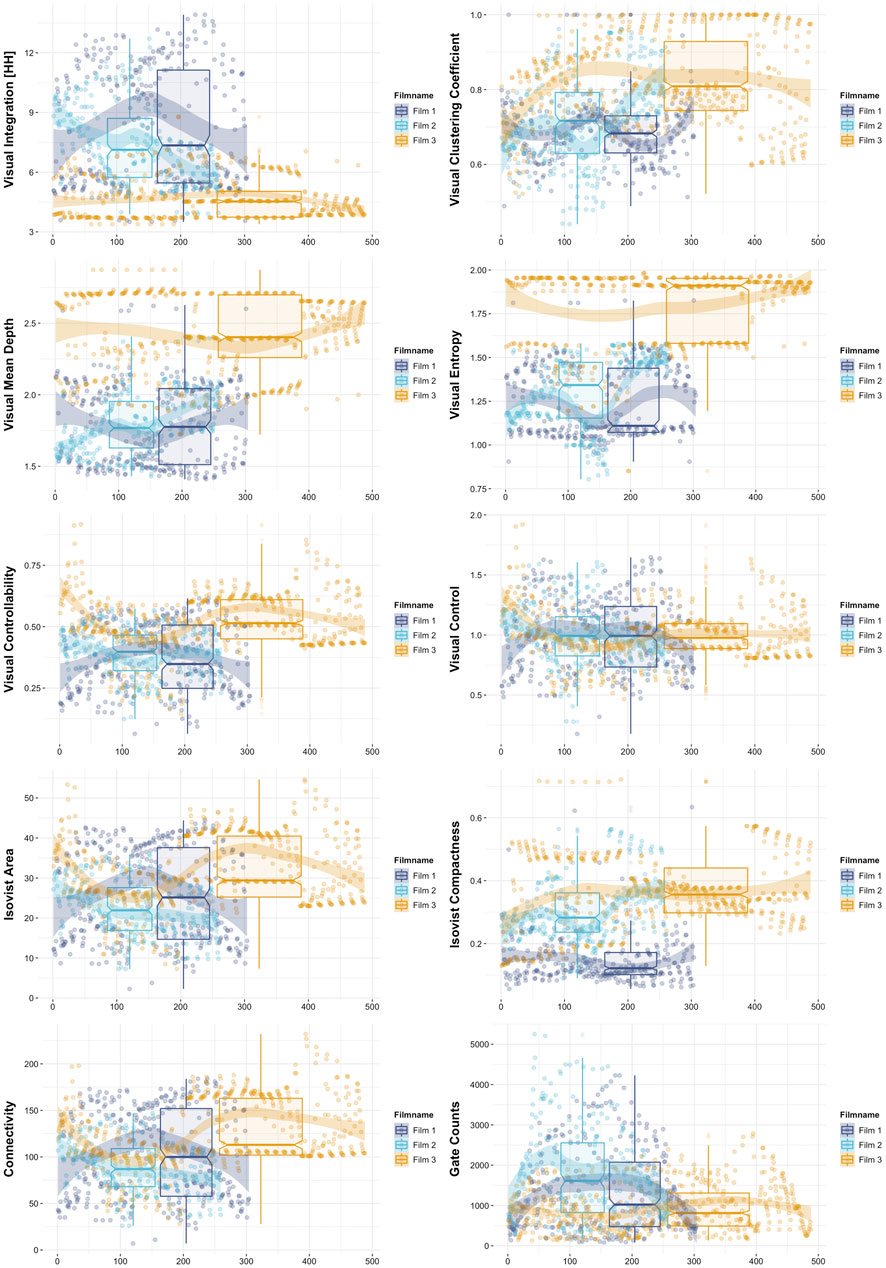

3.5 Space Syntax Analyses

VGA for the cinematic spaces demonstrated that the three films’ layouts differed in the geometric structure (Table 4), as discussed previously (Franz and Wiener 2005). Film 1 was a square-shaped space with a central void representing a centrality. Film 2’s events took place in an axial and linear space. In contrast, the architectural structure of film 3 had a more irregular and complex structure than the other two films, representing a combination of multiple axes and central space. In other words, the spatial characteristic of film 3 was a mixture of the other two films’ geometric structures. Thus, the measurement indicators of films’ architectural syntax differed, and the event’s impact was related to each space (Figure 9).

Regarding the isovist index, film 1’s space, despite the high area index, encompassed low compactness, whereas films 2 and 3 had almost the same area and compactness indicators. In addition, the connectivity index of spaces in film 1 and film 3 was relatively high but moderate in film 2. Still, the connectivity level of different segment points of film 3 spaces had a higher deviation from average points than the other two films. In other words, in film 3, segments’ points showed different connectivity than the other two films. Regarding the gate counts index, despite the differences between films’ spaces, the gates were symmetrical for all different segments of the spaces. In terms of visual indicators, film 3 showed high entropy, controllability, and mean depth, whereas these indicators were lower for film 2 than the other two films. Although film 1 showed similar data to film 3, the indicators’ intensity was notably lower than film 3. Consequently, film 2 had a much lower standard deviation in terms of the distribution of different data from spatial measurement criteria, showing that the segment points were more similar in terms of spatial measurement indicators, and the spaces were more homogeneous. In contrast, film 3 had a much lower homogeneity of points, and film 1 was average between films 2 and 3.

4 Discussion

Converging research findings show that spatial cognition based on mental embodiment proved to be significantly effective in analyzing the ordinariness of lived spaces and the impact of the disruptive event to understand the architectural quality of a place. As studied before (Li et al., 2021), environmental quality is crucial in achieving a sustainable and communicative design, and non-physical factors such as personal attitudes and past events affect this quality (Torresin et al., 2018). To achieve the sustainability goals, we focused on multiple mental and cognitive aspects of space to highlight the vitality of enhanced perception in everyday sustainable design thinking. Accordingly, environmental stimuli validated their influential roles in activating the sign system, which led to consequent event recall based on past experiences, root beliefs, and mentality between different participants, confirming the rhythm analysis theory (Lefebvre 2013). The narrative features of space in the cinematic form reveal significant potential for testing mental hypotheses and inferences. This test, both in movement-image and time-image theoretical frameworks, signifies the importance of remembering past experiences and their impact on assessing present and future in cognitive processes. Strong stimuli can enhance the potential to improve the illusion of motion in space and blend in with actual physical activity as they make a combination of real and false movements. This cinematic experience illustrated its practical aspect of capturing architectural essence in the behavioral analysis frame by frame to highlight each element’s physical and mental effect in understanding the sustainability of everyday life in terms of perception and communication. In this regard, the problematization concept of noticing the spatial impact on the cognitive behavior can be highly debated in sustainable design thinking and environmental research.

Moreover, criteria and components of understanding the quality of banal versus heterotopic spaces that are affected by events turn out to be substantially different. The geometry, structure, and isovist index of spaces analyzed in previous studies (Montello 2007; Osmond 2011; Kuliga et al., 2013; Xiang et al., 2021) were critical on how the event affects and changes attitudes towards spatial perception. The space syntax factors with higher event disruption had a different structure than the other two spaces in film spaces. The space with the non-linear structure and spatial diversity, such as the combination of various areas, different isovist properties, level differences, and visual connectivity, can determine an interactive and mentally engaging environment to generate a socially accepted sustainable design and improved environmental communication.

In addition, activation of the sensory-motor system leads to better imagination and improved perception of space. In an architectural space with more geometric complexity, the tendency to predict the next space and possible events in that space increases due to more engagement with spatial elements. Also, when more intensive events are witnessed, the sensory-motor activity is enhanced to imagine and predict the following scene environment. Hence, the cinematic space with a non-linear, complex, and hybrid geometric structure, within the context of a highly disruptive event, can transform a banal space into an inhomogeneous space and subsequently bring a more accurate perception of the quality of space. When an architectural space combines various axes for enhanced exploration, it holds more interactive spatial elements such as corridors, stairs, transparent materials, and integrated spaces with multiple areas and isovists. This quality can evoke cognitive emotions to eliminate the banality of lived space and validate more sustainable and communicative space criteria.

Conversely, poor environmental qualities decelerate cognitive tasks and debilitate physical and mental abilities. As Bala (2019) previously discussed, perceiving a place in space facilitates physiological needs and aesthetic satisfaction. In this study, notable events in a home environment that signified placeness successfully addressed these two factors by significantly changing bio-feedback responses and the subjective assessment of spatial qualities. According to our test model, the first part of each film clip that shows ordinary house space was regarded as a baseline situation to capture changes in biofeedback and psychological assessment differences with post-event scenes. This procedure was conducted to make sure that the psychophysiological changes of subjects were the outcome of space-related stimuli. During the experiment, the human response to stimuli in space was highly different in physiological, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral aspects, as previously discussed (Plutchik 1980; Izard 2013; Mahdavi 2020). In physiological feedback derived from different events and spatial structures, the HR and BP were most affected. We can also argue that the normalized quality of space changed based on the type of mental schemas, previous experiences, memory, and event recall.

As the subjects witnessed the film clips’ pre-event and post-event sections in a time frame, the effect of time would be essential to discuss. Participants in this study observed three different events in a total of 15 min clips in which each clip could have affected the subjects’ psychophysiological reaction. Previous studies showed that repeated exposure to suspenseful stimuli in films might cause affective habituation or desensitization (Mrug et al., 2015; Chun et al., 2020). However, the biofeedback reports do not show a significant desensitization effect since events’ impacts illustrate a gradual increase in reports from film 1 to film 3, especially in the HR and BP. As we conducted subjective assessments with Chills, SAM, and NAQ tests to support the physiological changes reports, participants’ self-reports validated a substantial impact throughout the film screening. Psychological reports during the time spent from film 1 to film 3 show no desensitization effects to influence the events’ intensity evaluations.

Feeling Chills and goosebumps illustrated a significant impact on changing the perception of place quality through the disruption of the banalization of the cinematic space. Additionally, participants with the positive affect scale in evaluating architectural space qualities considered positive aspects of spaces more than negative ones. In contrast, those with the reported negative affect scale before the test paid more attention to the negative elements during space observation. Likewise, participants with inclined negative personality traits noticed a lower level of space quality due to more Arousal and Chills and less Pleasure and Dominance. In contrast, subjects who had reported self-positive personality traits noticed more positive spatial attributes. Feeling lower Dominance and Pleasure but higher Arousal in perceiving space overlaps the typical mentality of individuals and collective mental schemas that lead to a transcendent environmental perception. Feeling too much and too low Pleasure causes the perception of space to be of lower quality, but when it creates a sense of moderate Pleasure, it will be an optimal criterion for an improved quality of space.

Regarding the aforementioned evaluations, some studies concluded that self-reports are prone to bias (Schwarz and Strack 1999), especially because they measure the conscious side of the human mind. Other studies discussed that the primary cognitive and emotional processes occur at the unconscious level (Zaltman 2003). We tried to measure both psychological and physiological aspects to validate our findings to weaken the biased consequences. As a result, the overlap and correlation between subjective and participants’ objective assessments validate that they were solely impressed by spatial properties as their physiological changes in the HR and BP had a meaningful relationship with space quality reports. In this study, our primary goal was to investigate the impact of space-related events on variables. The analysis of differences between the pre-event and post-event sufficiently answered our hypotheses. Also, no similar exploratory study (Neter et al., 1996) has been previously conducted to identify any additional significant variables in regression analyses. As we found no confounder to control its effect, we analyzed the unadjusted effect of the pre-event and post-event and the age factor separately. Still, we referred to the video-recorded contents from the participants to report any further observations from apparent psychophysiological changes. We found slight changes in skin tone color, pupils, and in some cases, goosebumps during the event and post-event scenes through the observational examinations. After the post-event scene screening, some participants were overwhelmed by the spatial stimuli and felt emotionally aroused. However, participants appeared to be more relaxed during the pre-event scenes, illustrating an alignment between observational analyses and subjects’ psychophysiological assessments.

In summary, applying multivariate behavioral analyses of subjective and objective evaluations during exposure to different spatial qualities and configurations signifies critically debating results to enlighten architects’ considerations during a sustainable design process. Quantitatively observing cinematic environments can help designers perceive how their upcoming elements of constructed space will interact with occupants. By achieving sustainable communicative space criteria, we can influence the society to live more sustainably when their perceptions and cognitive behaviors are highly regarded during the design process.

5 Conclusion

The analysis of the models in this research showed that creating a common collective mindset can be attributed to a broader context regarding the understanding of space. Placing an event to perform a cognitive task in mind to transform ordinariness into an inhomogeneous space can be an operational concept. Everydayness, ordinary space, and events differentiate perceptions and significant differences in normalized space quality. The intersection of psychophysiological assessments and space configuration features can help designers consider human behavior and subjective evaluation during the sustainable design process to enhance human–environment communication. As discussed in this research, multiple factors such as root beliefs and past experiences, personality traits, emotional feelings of a lived space, and the space structure play a substantial role in the pre-evaluation of the elements of a built environment. Utilizing film space screenings to capture architectural impacts on the cognitive behavior can substantially help sustainable thinking during the design by undertaking spatial interactions and enhanced perception. In a sustainable realm, enhancing cognition in environmental communication can be a problematic design approach when our everyday places such as homes integrated with our body and mind become boring and monotonous.

6 Limitations and Future Research

In future research, more sophisticated techniques such as neuroimaging can be conducted to obtain neurophysiological outputs in different brain parts, such as environment-related stress (Choi et al., 2015) or discomfort (Han and Chun 2021), and compare them with this study’s self-assessment variables. Also, it would be more accurate to examine and compare the elements of space in each scene frame of the studied film separately to analyze the impacts of events intensity more precisely. Accordingly, gaze-related tools such as eye-tracking with emphasis on the eye pupil attention (Choi and Zhu 2015) can offer a suitable potential to examine each architectural element. ANCOVA analyses will give us more comprehensive outcomes from adjusted variables after identifying different effective variables and controlling them in future studies. Focusing solely on the effect of stimuli in a specific group of people may not be generalized to a large population when ignoring cultural differences and preferences (Wang and Cheong 2006; Xu et al., 2008). It would be better to explore a larger statistical population to reach more comprehensive data for personality traits and related affective factors, both within a nation and between different nationalities. This holistic approach helps to receive a notable comparison of characteristics, beliefs, and past experiences between other societies exposed to space stimuli for more comprehensive sustainable design and communication discussions.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Department of Physiology–Tarbiat Modares University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Navid Ziaei Darounkolaei for his sincere contribution to bio-feedback measurements, especially the SRL data collection.

Abbreviations

BF, biofeedback; SBP, systolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BP, blood pressure; SAM, Self-Assessment Manikin; BT, body temperature; NAQ, normalized accumulated quality; PA, positive affects; VGA, visibility graph analysis; NA, negative affects; TIPI, Ten-Item Personality Inventory; SCL, skin conductance level ; SRL, skin resistance level; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule.

References

Akerlof, K. L., Timm, K. M. F., Rowan, K. E., Olds, J. L., and Hathaway, J. (2022). The Growth and Disciplinary Convergence of Environmental Communication: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Field (1970–2019). Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 1. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.814599

Andargie, M. S., and Azar, E. (2019). An Applied Framework to Evaluate the Impact of Indoor Office Environmental Factors on Occupants' comfort and Working Conditions. Sustainable Cities Soc. 46, 101447. doi:10.1016/J.SCS.2019.101447

Arabacioglu, B. C. (2010). Using Fuzzy Inference System for Architectural Space Analysis. Appl. Soft Comput. 10, 926–937. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2009.10.011

Bakker, I., van der Voordt, T., Vink, P., and de Boon, J. (2014). Pleasure, Arousal, Dominance: Mehrabian and Russell Revisited. Curr. Psychol. 33, 405–421. doi:10.1007/s12144-014-9219-4

Bala, A. H. (2019). Architectural Reading of the Film “Terminal” via Non-place”. Online J. Art Des. 7, 53–66.

Banaei, M., Ahmadi, A., Gramann, K., and Hatami, J. (2020). Emotional Evaluation of Architectural interior Forms Based on Personality Differences Using Virtual Reality. Front. Architectural Res. 9, 138–147. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2019.07.005

Bannister, S. (2019). Distinct Varieties of Aesthetic Chills in Response to Multimedia. PloS one 14, e0224974. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224974

Bolls, P. D., Lang, A., and Potter, R. F. (2001). The Effects of Message Valence and Listener Arousal on Attention, Memory, and Facial Muscular Responses to Radio Advertisements. Commun. Res. 28, 627–651. doi:10.1177/009365001028005003

Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Cuthbert, B. N., and Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotion and Motivation I: Defensive and Appetitive Reactions in Picture Processing. Emotion 1, 276–298. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.276

Bradley, M. M., and Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring Emotion: the Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 25, 49–59. doi:10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9

Bradley, M. M. (2009). Natural Selective Attention: Orienting and Emotion. Psychophysiology 46, 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00702.x

Carvalho, S., Leite, J., Galdo-Álvarez, S., and Gonçalves, Ó. F. (2011). Psychophysiological Correlates of Sexually and Non-sexually Motivated Attention to Film Clips in a Workload Task. PLoS One 6, e29530. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029530

Carvalho, S., Leite, J., Galdo-Álvarez, S., and Gonçalves, Ó. F. (2012). The Emotional Movie Database (EMDB): A Self-Report and Psychophysiological Study. Appl. Psychophysiol Biofeedback 37, 279–294. doi:10.1007/s10484-012-9201-6

Casco, B. (2013). in Fuzzy Thinking. Editors A. Ghaffari Fifth Edition (Tehran: Publisher of Khajeh Nasir al-Din Tusi University of Technology).

Chandler, M. R. (1991). Housekeeping and Beloved: When Women Come Home. Dwelling Text: Houses Am. Fiction 1, 291–318.

Choi, J.-H., and Zhu, R. (2015). Investigation of the Potential Use of Human Eye Pupil Sizes to Estimate Visual Sensations in the Workplace Environment. Building Environ. 88, 73–81. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.11.025

Choi, Y., Kim, M., and Chun, C. (2015). Measurement of Occupants' Stress Based on Electroencephalograms (EEG) in Twelve Combined Environments. Building Environ. 88, 65–72. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.10.003

Chun, C., Park, B., and Shi, C. (2020). Re-Living Suspense: Emotional and Cognitive Responses during Repeated Exposure to Suspenseful Film. Front. Psychol. 11, 558234. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.558234

Coëgnarts, M. (2017). Cinema and the Embodied Mind: Metaphor and Simulation in Understanding Meaning in Films. Palgrave Commun. 3, 1–15.

Colman, A., and Colman, L. (1971). Pregnancy: The Psychological Experience. New York: Herder & Herder.

Cuthbert, B. N., Schupp, H. T., Bradley, M. M., Birbaumer, N., and Lang, P. J. (2000). Brain Potentials in Affective Picture Processing: Covariation with Autonomic Arousal and Affective Report. Biol. Psychol. 52, 95–111. doi:10.1016/s0301-0511(99)00044-7

Deng, Y., Yang, M., and Zhou, R. (2017). A New Standardized Emotional Film Database for Asian Culture. Front. Psychol. 8, 1941. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01941

Dijkstra, K., Pieterse, M. E., and Pruyn, A. T. H. (2008). Individual Differences in Reactions towards Color in Simulated Healthcare Environments: The Role of Stimulus Screening Ability. J. Environ. Psychol. 28, 268–277. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.02.007

Ding, N., Zhou, W., and Fung, A. Y. H. (2018). Emotional Effect of Cinematic VR Compared with Traditional 2D Film. Telematics Inform. 35, 1572–1579. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2018.04.003

Dzhambov, A. M., Markevych, I., Hartig, T., Tilov, B., Arabadzhiev, Z., Stoyanov, D., et al. (2018). Multiple Pathways Link Urban green- and Bluespace to Mental Health in Young Adults. Environ. Res. 166, 223–233. doi:10.1016/J.ENVRES.2018.06.004

Ekman, P., Levenson, R. W., and Friesen, W. V. (1983). Autonomic Nervous System Activity Distinguishes Among Emotions. science 221, 1208–1210. doi:10.1126/science.6612338

Fernández-Aguilar, L., Latorre, J. M., Martínez-Rodrigo, A., Moncho-Bogani, J. V., Ros, L., Latorre, P., et al. (2020). Differences between Young and Older Adults in Physiological and Subjective Responses to Emotion Induction Using Films. Scientific Rep. 10, 1–13. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-71430-y

Franz, G., and Wiener, J. M. (2005). “Exploring Isovist-Based Correlates of Spatial Behavior and Experience,” in 5th International Space Syntax Symposium (Delft, Netherlands: Techne Press), 503–517.

Ghahramani, M. B., Piravi Vanak, M., Mazaherian, H., and Sayyad, A. (2015). The Moving Body of the Spectator and Formation of Spatial Sequences in Cinematic Architecture. Honar-ha-ye-ziba: Memary Va. Shahrsazi 19, 27–36. doi:10.22059/jfaup.2015.55693

Goguen, J. A. (1973). LA Zadeh. Fuzzy Sets. Information and Control, Vol. 8 (1965), Pp. 338–353.-LA Zadeh. Similarity Relations and Fuzzy Orderings. Information Sciences, Vol. 3 (1971), Pp. 177–200. The J. Symbolic Logic 38, 656–657. doi:10.2307/2272014

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., and Swann, W. B. (2003). A Very Brief Measure of the Big-Five Personality Domains. J. Res. Personal. 37, 504–528. doi:10.1016/s0092-6566(03)00046-1

Greenwald, M. K., Cook, E. W., and Lang, P. J. (1989). Affective Judgment and Psychophysiological Response: Dimensional Covariation in the Evaluation of Pictorial Stimuli. J. psychophysiology 3 (1), 51–64.

Gruber, J., Mennin, D. S., Fields, A., Purcell, A., and Murray, G. (2015). Heart Rate Variability as a Potential Indicator of Positive Valence System Disturbance: a Proof of Concept Investigation. Int. J. Psychophysiology 98, 240–248. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.08.005

Guidano, V. F., and Liotti, G. (1983). Cognitive Processes and Emotional Disorders: A Structural Approach to Psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Hammen, C., and Goodman-Brown, T. (1990). Self-schemas and Vulnerability to Specific Life Stress in Children at Risk for Depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 14, 215–227. doi:10.1007/bf01176210

Han, J., and Chun, C. (2021). Differences between EEG during thermal Discomfort and thermal Displeasure. Building Environ. 204, 108220. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108220

Hanich, J., Wagner, V., Shah, M., Jacobsen, T., and Menninghaus, W. (2014). Why We like to Watch Sad Films. The Pleasure of Being Moved in Aesthetic Experiences. Psychol. Aesthetics, Creativity, Arts 8, 130–143. doi:10.1037/a0035690

Hee Lin Wang, H. L., and Loong-Fah Cheong, L.-F. (2006). Affective Understanding in Film. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 16, 689–704. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2006.873781

Hoisington, A. J., Stearns-Yoder, K. A., Schuldt, S. J., Beemer, C. J., Maestre, J. P., Kinney, K. A., et al. (2019). Ten Questions Concerning the Built Environment and Mental Health. Building Environ. 155, 58–69. doi:10.1016/J.BUILDENV.2019.03.036

Ingram, R. E. (1984). Toward an Information-Processing Analysis of Depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 8, 443–477. doi:10.1007/bf01173284

Jokić-Begić, N. (2008). Bihevioralno-kognitivne Terapije. Psihoterapija-škole i psihoterapijski pravci u Hrvatskoj danas 1, 63–74.

Kandel, E. R., Schwartz, J. H., Jessell, T. M., Siegelbaum, S., Hudspeth, A. J., and Mack, S. (2000). Principles of Neural Science. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kent, M., Parkinson, T., Kim, J., and Schiavon, S. (2021). A Data-Driven Analysis of Occupant Workspace Dissatisfaction. Building Environ. 205, 108270. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108270

Khaleghimoghaddam, N., and Bala, H. A. (2018). The Impact of Environmental and Archıtectural Design on Users' Affective Experience. YBL J. Built Environ. 6, 5–19. doi:10.2478/jbe-2018-0001

Kimura, K., Haramizu, S., Sanada, K., and Oshida, A. (2019). Emotional State of Being Moved Elicited by Films: A Comparison with Several Positive Emotions. Front. Psychol. 10, 1935. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01935

Kistler, A., Mariauzouls, C., and von Berlepsch, K. (1998). Fingertip Temperature as an Indicator for Sympathetic Responses. Int. J. psychophysiology 29, 35–41. doi:10.1016/s0167-8760(97)00087-1

Korpal, P., and Jankowiak, K. (2018). Physiological and Self-Report Measures in Emotion Studies: Methodological Considerations. Polish Psychol. Bull. 49 (4), 475–481. doi:10.24425/124345

Kosko, B., and Toms, M. (1994). Fuzzy Thinking: The New Science of Fuzzy Logic. Flamingo London: International Journal of General Systems.

Kreibig, S. D., Wilheim, F. H., Gross, J. J., and Roth, W. T. (2007). “The Psychophysiology of Fear and Sadness: Cardiovascular, Electrodermal, and Respiratory Responses during Film Viewing,” in 47th Annual Meeting of the Society-for-Psychophysiological-Research, OXFORD OX4 2DQ, OXON, ENGLAND (Bethesda, MD: BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 9600 GARSINGTON RD). S20–S20.

Kuliga, S., Dalton, R. C., and Hölscher, C. (2013). “Aesthetic and Emotional Appraisal of the Seattle Public Library and its Relation to Spatial Configuration,” in Proceedings of the International Space Syntax Symposium 2013 (Seoul, South Korea: Sejong University), 1–17.

Kunzmann, U., and Grühn, D. (2005). Age Differences in Emotional Reactivity: the Sample Case of Sadness. Psychol. Aging 20, 47–59. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.47

Lang, A., Dhillon, K., and Dong, Q. (1995). The Effects of Emotional Arousal and Valence on Television Viewers' Cognitive Capacity and Memory. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 39, 313–327. doi:10.1080/08838159509364309

Lang, P. J., Greenwald, M. K., Bradley, M. M., and Hamm, A. O. (1993). Looking at Pictures: Affective, Facial, Visceral, and Behavioral Reactions. Psychophysiology 30, 261–273. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1993.tb03352.x

Lang, P. J. (1969). The Mechanics of Desensitization and the Laboratory Study of Human Fear. New York: McGraw-Hill, 160–191. Behavior therapy: Appraisal and status.

Li, Z., Ba, M., and Kang, J. (2021). Physiological Indicators and Subjective Restorativeness with Audio-Visual Interactions in Urban Soundscapes. Sustainable Cities Soc. 75, 103360. doi:10.1016/J.SCS.2021.103360

Love, P. E. D., Edwards, D. J., and Irani, Z. (2010). Work Stress, Support, and Mental Health in Construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 136, 650–658. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000165

Mahdavi, A. (2020). Explanatory Stories of Human Perception and Behavior in Buildings. Building Environ. 168, 106498. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106498

Maruskin, L. A., Thrash, T. M., and Elliot, A. J. (2012). The Chills as a Psychological Construct: Content Universe, Factor Structure, Affective Composition, Elicitors, Trait Antecedents, and Consequences. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 103, 135–157. doi:10.1037/a0028117

Mehrabian, A. (1996). Pleasure-arousal-dominance: A General Framework for Describing and Measuring Individual Differences in Temperament. Curr. Psychol. 14, 261–292. doi:10.1007/bf02686918

Montello, D. R. (2007). “The Contribution of Space Syntax to a Comprehensive Theory of Environmental Psychology,” in Proceedings of the 6th International Space Syntax Symposium. _Istanbul, iv-1–12Retrieved from: http://www.spacesyntaxistanbul.itu.edu.tr/papers/invitedpapers/daniel_montello.pdf(Citeseer.

Mrug, S., Madan, A., Cook, E. W., and Wright, R. A. (2015). Emotional and Physiological Desensitization to Real-Life and Movie Violence. J. Youth Adolescence 44, 1092–1108. doi:10.1007/s10964-014-0202-z

Musa, C. Z., and Lépine, J. P. (2000). Cognitive Aspects of Social Phobia: A Review of Theories and Experimental Research. Eur. Psychiatr. 15, 59–66. doi:10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00210-8

Neter, J., Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., and Wasserman, W. (1996). Applied Linear Regression Models. New York: Irwin. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?id=4CrvAAAAMAAJ.

Neumann, D. (1999). Film Architecture: From Metropolis to Blade Runner-“Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari”. Prestel.

Nin, A., and Stuhlmann, G. (1966). The Diary of Anais Nin: Volume One: 1931-1934. Harvest/Harcourt, Brace & World.

Nitsche, M., Roudavski, S., Penz, F., and Thomas, M. (2002). Narrative Expressive Space. SIGGROUP Bull. 23, 10–13. doi:10.1145/962185.962189

Pallasmaa, J. (2007a). The Architecture of Image: Existential Space in Cinema. Helsinki: Rakennustieto.

Panksepp, J., and Bernatzky, G. (2002). Emotional Sounds and the Brain: the Neuro-Affective Foundations of Musical Appreciation. Behav. Process. 60, 133–155. doi:10.1016/s0376-6357(02)00080-3

Penz, F. (2017). Cinematic Aided Design: An Everyday Life Approach to Architecture. London: Routledge.

Prinz, W. (2005). An Ideomotor Approach to Imitation. Perspect. imitation: Neurosci. Soc. Sci. 1, 141–156.

Prkachin, K. M., Williams-Avery, R. M., Zwaal, C., and Mills, D. E. (1999). Cardiovascular Changes during Induced Emotion. J. psychosomatic Res. 47, 255–267. doi:10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00036-7

Ragin, C. C. (2009). Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and beyond. Social Forces 88, 1936–1938.

Ravaja, N. (2004). Contributions of Psychophysiology to media Research: Review and Recommendations. Media Psychol. 6, 193–235. doi:10.1207/s1532785xmep0602_4

Reinecke, M. A., Dattilio, F. M., and Freeman, A. (1996). Cognitive Therapy with Children and Adolescents. New York: The Guilford.

Roudavski, S., and Penz, F. (2003). Space, agency, Meaning and Drama in Navigable Real-Time Virtual Environments. Utrecht, Netherlands: DIGRA.

Rusting, C. L. (1998). Personality, Mood, and Cognitive Processing of Emotional Information: Three Conceptual Frameworks. Psychol. Bull. 124, 165–196. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.165

Sakhaei, H. (2020). Interactive Kinetic Canopy with Industrial Architecture Legacy Preservation Approach. Jard 4, 1. doi:10.26689/jard.v4i2.1033

Schneider, W. (1987). Sinn und Un-Sinn: Umwelt sinnlich erlebbar gestalten in Architektur und Design. Gütersloh, Germany: Bau-Verlag.

Schubert, T. W., Zickfeld, J. H., Seibt, B., and Fiske, A. P. (2018). Moment-to-moment Changes in Feeling Moved Match Changes in Closeness, Tears, Goosebumps, and Warmth: Time Series Analyses. Cogn. Emot. 32, 174–184. doi:10.1080/02699931.2016.1268998

Schupp, H., Cuthbert, B., Bradley, M., Hillman, C., Hamm, A., and Lang, P. (2004). Brain Processes in Emotional Perception: Motivated Attention. Cogn. Emot. 18, 593–611. doi:10.1080/02699930341000239

Schwarz, N., and Strack, F. (1999). Reports of Subjective Well-Being: Judgmental Processes and Their Methodological Implications. Well-being: foundations hedonic Psychol. 7, 61–84.

Segal, Z. V. (1988). Appraisal of the Self-Schema Construct in Cognitive Models of Depression. Psychol. Bull. 103, 147–162. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.147

Silvia, P. J., and Nusbaum, E. C. (2011). On Personality and Piloerection: Individual Differences in Aesthetic Chills and Other Unusual Aesthetic Experiences. Psychol. Aesthetics, Creativity, Arts 5, 208–214. doi:10.1037/a0021914

Sinha, R. (1996). Multivariate Response Patterning of Fear and Anger. Cogn. Emot. 10, 173–198. doi:10.1080/026999396380321

Šolcová, I. P., and Lačev, A. (2017). Differences in Male and Female Subjective Experience and Physiological Reactions to Emotional Stimuli. Int. J. Psychophysiology 117, 75–82. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2017.04.009

Soleymani, M., Chanel, G., Kierkels, J. J. M., and Pun, T. (2009). Affective Characterization of Movie Scenes Based on Content Analysis and Physiological Changes. Int. J. Semantic Comput. 03, 235–254. doi:10.1142/s1793351x09000744

Torresin, S., Pernigotto, G., Cappelletti, F., and Gasparella, A. (2018). Combined Effects of Environmental Factors on Human Perception and Objective Performance: A Review of Experimental Laboratory Works. Indoor Air 28, 525–538. doi:10.1111/INA.12457

Turner, A., Doxa, M., O'Sullivan, D., and Penn, A. (2001). From Isovists to Visibility Graphs: a Methodology for the Analysis of Architectural Space. Environ. Plann. B Plann. Des. 28, 103–121. doi:10.1068/b2684

Upton, D. (2002). Architecture in Everyday Life. New Literary Hist. 33, 707–723. doi:10.1353/nlh.2002.0046

Wang, L., Zhou, Y., Wang, F., Ding, L., Love, P. E. D., and Li, S. (2021). The Influence of the Built Environment on People's Mental Health: An Empirical Classification of Causal Factors. Sustainable Cities Soc. 74, 103185. doi:10.1016/J.SCS.2021.103185

Wassiliwizky, E., Wagner, V., Jacobsen, T., and Menninghaus, W. (2015). Art-elicited Chills Indicate States of Being Moved. Psychol. Aesthetics, Creativity, Arts 9, 405–416. doi:10.1037/aca0000023

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., and Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: the PANAS Scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 54, 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Xiang, L., Cai, M., Ren, C., and Ng, E. (2021). Modeling Pedestrian Emotion in High-Density Cities Using Visual Exposure and Machine Learning: Tracking Real-Time Physiology and Psychology in Hong Kong. Building Environ. 205, 108273. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108273

Xu, M., Jin, J. S., Luo, S., and Duan, L. (2008). “Hierarchical Movie Affective Content Analysis Based on Arousal and Valence Features,” in Proceedings of the 16th ACM international conference on Multimedia, 677–680. doi:10.1145/1459359.1459457

Yeganeh, M. (2020). Conceptual and Theoretical Model of Integrity between Buildings and City. Sustainable Cities Soc. 59, 102205. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2020.102205

Yeganeh, M., and Kamalizadeh, M. (2018). Territorial Behaviors and Integration between Buildings and City in Urban Public Spaces of Iran׳s Metropolises. Front. Architectural Res. 7, 588–599. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2018.06.004

Yoshihara, K., Tanabe, H. C., Kawamichi, H., Koike, T., Yamazaki, M., Sudo, N., et al. (2016). Neural Correlates of Fear-Induced Sympathetic Response Associated with the Peripheral Temperature Change Rate. NeuroImage 134, 522–531. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.040

Zaltman, G. (2003). How Customers Think: Essential Insights into the Mind of the Market. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Zawidzki, M. (2016). Automated Geometrical Evaluation of a plaza (Town Square). Adv. Eng. Softw. 96, 58–69. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.018

Keywords: cinematic mediation, psychophysiological responses, spatial perception, space configuration, sustainable design criteria

Citation: Sakhaei H, Yeganeh M and Afhami R (2022) Quantifying Stimulus-Affected Cinematic Spaces Using Psychophysiological Assessments to Indicate Enhanced Cognition and Sustainable Design Criteria. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:832537. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.832537

Received: 10 December 2021; Accepted: 09 March 2022;

Published: 26 April 2022.

Edited by:

Denise Voci, University of Klagenfurt, AustriaReviewed by:

Havva Alkan Bala, Çukurova University, TurkeyVincent Omwenga, Strathmore University, Kenya

Elaheh Zareanshahraki, Monash University, Australia