- 1College of Education, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

- 2School of Marxism, NingboTech University, Ningbo, China

- 3Zhejiang Gongshang University Hangzhou College of Commerce, Hangzhou, China

- 4School of International Studies, NingboTech University, Ningbo, China

Young people, including college students, are the main body for the main force of public welfare entrepreneurship and the effective force of future social entrepreneurs. How can college students, who are often self-made and lack entrepreneurial experience, social capital, and resources, grow up to be “moral leaders” of social entrepreneurship organizations? And what role does social entrepreneurship education play? Previous studies have not provided corresponding theoretical explanations to address these questions. This study uses as examples two public welfare organizations and their founders; namely, YinChao Pension Service Center in Yinzhou District, Ningbo City, and Ant Public Welfare Service Center in Yuyao City. The exploratory comparative research method of two cases is used, and the perspective is constructed based on personal significance. Through the open decoding analysis, this study refines the key elements of the individual growth of public entrepreneurs as “moral leaders,” including four stages: concept construction, moral conflict, relationship construction, and rule construction, as well as personal meaning construction strategy and public entrepreneurship education strategy. The research results not only explain how individuals grow up to be “moral leaders” in public welfare organizations through self-meaning construction in the context of public welfare entrepreneurship and the construction process from individual to organization morality systems but also provide a theoretical framework for cultivating successful public welfare entrepreneurs and a theoretical reference for the sustainable development of public welfare entrepreneurs and public welfare entrepreneurship education in colleges and universities.

Research background

In recent years, social entrepreneurship education, which emphasizes the solution of social problems by commercial means by insisting on the double bottom line of social and commercial values, has attracted increasing attention due to its unique educational function. Public entrepreneurship education aims to improve people’s moral character, enhance innovation ability, and achieve all-around development. Its social, commercial, and practical characteristics are naturally integrated into the educational function of colleges and universities. Social entrepreneurship education also has unique advantages for “developing entrepreneurial skills, consolidating survival value, enriching social capital, enhancing development value, promoting moral consciousness, and digging meaning value” (Yang, 2017).

Young people, mainly college students, are the main force of social entrepreneurship. With the increasing popularity of public entrepreneurship education in colleges and universities, many outstanding public entrepreneurs have emerged. They take responsibility for solving social problems and often start from scratch to perform public entrepreneurship projects and establish public organizations. With their enthusiasm and charisma, they attract many followers and become “leaders” of social entrepreneurship organizations with both business savvy and a strong sense of social responsibility. Due to their non-profit status, public welfare organizations lack natural “interest” bonding within the organization, and the cohesion between the members of the organization depends more on common values and moral standards. However, the founder of an organization often plays the role of “moral leader,” and plays a vital role in the key operational links of the start-up of a social organization, such as identifying social problems, attracting organization members, reaching key consensus, establishing a formal organization, integrating social resources, solving social problems, and promoting the development of the organization. Practical observations also show that the core role of “moral leaders” is indispensable for successful public interest organizations. The long-term practice and related research in the field of organization management have shown that in the initial stage of an organization, the leadership of the founder is the key factor for the organization’s success or failure. Especially for public welfare organizations, due to their non-profit status, there is a lack of natural “interest” bonding within the organization; thus, the cohesion between members depends more on common values and moral standards. The founder of such organizations often plays the role of “moral leader,” and is vital in the key operational links of the start-up of a social organization, such as identifying social problems, attracting organization members, reaching key consensus, establishing a formal organization, integrating social resources, solving social problems, and promoting the development of the organization. Practical observations also show that the core role of “moral leaders” is indispensable for successful public interest organizations.

However, the role of “moral leader” is not endowed by God, nor is it born from thin air. There remains a lack of understanding and in-depth theoretical research on the process of producing and being recognized. Existing studies on “moral leaders” are mostly limited to behavioral studies at the micro level, such as the moral intuition of individuals in organizations (Haidt, 2012; Weaver et al., 2014) and the behavioral qualities of “moral leaders” (Hoch et al., 2018; Lemoine et al., 2019) and conscientiousness (Maak and Pless, 2006). Emerging literature has addressed “values work,” involving research on the breaking, creation, and maintenance of values at the organizational level (Kraatz et al., 2010; Gehman et al., 2013; Vaccaro and Palazzo, 2015); however, but research from the organizational interaction perspective is lacking regarding how to connect the micro and macro levels and how “moral leaders” have a broader impact. Moreover, previous research has not considered start-up public welfare organizations, especially college students who lack entrepreneurial experience, social capital, and entrepreneurial resources. There remains no clear theoretical explanation for how they generate moral consciousness and moral courage, express their moral stand, and link their followers and their moral beliefs in an organization or field to become “moral leaders” with charisma and a cohesive entrepreneurial team.

Therefore, this study takes the private non-enterprise units YinChao Pension Service Center in Yinzhou District, Ningbo City, Ant Public Welfare Service Center in Yuyao City and their principals as the case study objects, and uses the exploratory comparative case study method to explore the following problems:

1) From the perspective of individual development, how does the “moral leadership” of start-up public welfare organizations arise? How does an individual raise personal moral principles to organizational morality and become the “moral leader” of the organization? What are the stages of this process? What are the key elements? What are the strategic behaviors in each stage of the above process? What is the relationship between them and the construction of their personal meaning?

2) From the perspective of public entrepreneurship education, what role does this education play in the above stages? What role should educators play? How to better play the educational function of public entrepreneurship? What factors in the university will affect the moral development of students? How do the university culture and environment relate students to ethical outcomes?

This study aims to: identify the development stages of moral leaders by case analysis based on the Meaning Making theory and identify key factors influencing the moral development of college students receiving education on social entrepreneurship.

Literature review

Public entrepreneurship and “moral leaders"

Social entrepreneurship is usually motivated by a social mission. Individuals or organizations adopt business strategies in the social non-profit field, aiming at efficiency, innovation, and social value to build a sustainable and competitive organizational entity (Hu, 2006). This process has been described both as a combination of social mission, innovation, and business (Dees et al., 2001) and a response to a social need requiring an out-of-the-box solution (Martin and Osberg, 2007). Similar to business entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship progresses from team establishment, organization and communication, system establishment, and normal operation from the transition stage to the transformation and stable stages (Dees et al., 2001). Most definitions focus on four major factors: the characteristics of the social entrepreneurs themselves, their operative domain, the processes or resources used, and the mission of the social entrepreneur (Dacin et al., 2011).

Compared to other entrepreneurs, social entrepreneurs prefer the sense of social achievement brought by being innovators, emphasize self-realization, and have personal feelings of non-material pursuit and altruism (Xue and Zhang, 2016). Altruism is the most important and core motivation of social entrepreneurs (Zahxa and Gedajlovie, 2009), which can be expressed from three dimensions of public service, fairness and justice, and dedication, while self-interested motivation can be explained by the two dimensions of achievement orientation and control orientation (Zeng, 2014). Recently, Wettermark and Berglund (2022) also considered what relationships are possible between social entrepreneurs and those whom they strive to assist, their “beneficiaries,” and how dimensions of mutuality—integral to the idea of SE—may be expressed in interactions between entrepreneurs and beneficiaries.

Compassion and prosocial factors are also the core factors that distinguish social entrepreneurs from business entrepreneurs. Compassion can complement traditional self-orientation by encouraging increased integrative thinking, more pro-social forms of weighing costs and benefits, and a commitment to alleviate the suffering of others, ultimately resulting in self-orientation through social entrepreneurship (Miller et al., 2012). SE intentions are based on two complementary mechanisms: self-efficacy (an agentic mechanism), and social worth (a communal mechanism) (Bacqa and Altb, 2018).

Researchers have applied identity theory to explain social entrepreneurship (Stryker and Burke, 2000). By adopting an identity-based lens, entrepreneurs have been recast not simply as individuals who create a venture but also as individuals who fervently pursue entrepreneurial activities that provide significant self-meaning (Murnieks and Mosakowski, 2007). This identity perspective helps to explain the diverse motivations driving entrepreneurs, including their distinct decision-making and strategic actions. When salient or central, identity can predict an entrepreneur’s behaviors (Fauchart and Gruber, 2011: 945).

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy affects socially motivated entrepreneurial activities (Austin et al., 2006; Zahra et al., 2009). Such self-motivation is relevant in social entrepreneurship because entrepreneurs need persistent motivations to overcome the conflict between social goals and entrepreneurship’s economic functions (Harding, 2004). Thus, entrepreneurial self-efficacy can explain entrepreneurs’ sources of motivation to enact their intentions even though circumstances may not fit the enactment (Newman et al., 2018; Hsu et al., 2019).

In addition, studies on public entrepreneurs have researched how compassion promotes collective ability (Kanov et al., 2004); how people promote others’ interests by bearing material costs (Rabin, 2002; Camerer and Fehr, 2006); emotional factors in decision making (Cardon et al., 2009) considering that entrepreneur self-efficacy may be influenced by other people (Licht, 2010); the relationship between empathy, moral identity, and the altruistic tendency of college students (Wu et al., 2020); etc. The motivation factors of potential social entrepreneurs may include social organization experience, empathy, moral responsibility, self-efficacy, perceived social support, pride, mutual benefit, homesickness, etc. (Katre and Salipante, 2012; Hockerts, 2017).

In the process of social entrepreneurship, the philosophical bases of social entrepreneurs and “moral leaders” are consistent. From the perspective of oriental management philosophy, social entrepreneurs demonstrate “doing good” and “doing everything smoothly” (Xu and Shi, 2012), among which, “doing good” is the expression of “benevolence,” while “doing everything smoothly” is the expression of “ability.” In the Book of Rites, “people who get on well with both superiors and subordinates are benevolent.” The Confucian “benevolent person” has good moral character, just as social entrepreneurs must “get on well with both superiors and subordinates,” cherish the heart of heaven and Earth, and have the quality of benevolence. A “benevolent person” has no desire to compete for fame and profit. Social entrepreneurship must seize the opportunity, integrate resources, persuade the community, and even carry out institutional entrepreneurship, which incorporates the concept that “everything goes smoothly” (Dacin et al., 2011; Kent and Dacin, 2013).

Based on the classical and practical theory of wisdom, a moral person is one who develops certain virtues based on intellect, reasoning, knowledge, and positive emotions (such as love, care, and compassion). The integration of rationality and emotion plays a crucial role in promoting moral behavior and the willingness to act wisely, as well as realizing the highest interests not only for the self but also for the community (Zhu et al., 2016). Mencius also said that morality is developed from people’s hearts or emotional fields, in which compassion is the most important factor. He emphasized the practice of justice and the establishment of moral norms by externalizing moral values and virtues (for example, performing moral acts), thus integrating the seemingly competing inner and rational logic. Mencius also emphasized the importance of cultivating external morality and moral behavior to internalize moral emotion through constant self-reflection.

Through the practice of internalizing compassion and externalizing moral behavior, people can integrate the paradoxical values related to heart and reason, which is closely related to the logic of integrating business and public welfare. From this point of view, successful social entrepreneurs are “benevolent and capable people” who can be seen as the aggregation of schools of social innovation and social enterprise (Dees and Anderson, 2003). Groups that participate in social entrepreneurship have the characteristic of moral quality. Thus, the process of becoming a leader of a public service organization is the process of the practice and externalization of moral behavior, the process of individual self-realization, and the core factor for the development of organizations.

Construction of individual meaning and “moral leader"

The Meaning Making theory, proposed by Robert Kegan in 1982, is a process of defining beliefs, understanding, and commitment. Baxter Magolda et al. (2012) believed that meaning making is a process in which individuals understand identity, give meaning to actions, and decide how to get along with people and society. The development of meaning making should go through three stages: following external procedures, wandering at crossroads, and self-leading (Cen, 2014). It is also a question of what we usually call “how I perceive,” “who I am,” and “how I construct relationships with others.” The concept is quoted in the field of pedagogy. Cen (2016) used the theory of meaning making to construct a pyramid model through empirical research to describe the process of college students’ learning and development. “Moral leaders” are described as honest, trustworthy, and fair, who treat followers with respect and care, maintain commitment, give followers input and share in decision-making, and clarify their expectations and responsibilities (Treviño et al., 2003; Brown and Treviño, 2006). Fehr et al. (2015) summarized the role of “moralized” leadership behavior in defining “ethical leadership.” The moralizing view of a leader’s behavior stems from the moral intuitions of the followers. Individuals will have typical evaluation models in social systems, such as moral commonness (fairness and dignity), family or social values, institutional logic, etc. (Boltanski and Thevenot, 2006; Thornton et al., 2012; Abend, 2014). Different researchers have reported consistent findings: social interaction bridges the micro level of moral leadership to the macro level of moral system organization, through interactions and exchanges between leaders and followers on issues (Hallett and Ventresca, 2006). Especially when an organization is facing specific problems and moments, members use the behavioral framework provided by the values, ideologies, and ethics to explain uncertain problems and gradually legitimize them (Boltanski and Thevenot, 2006; Thornton et al., 2012; McPherson and Sauder, 2013). The moral system is also a dynamic process. Leaders and followers seek to expand the moral system and actively reshape, dismantle or expand its boundaries, leading to its evolution (Ashforth et al., 2000; Zietsma and Lawrence, 2010).

The steps of moral leadership are like the process of constructing personal meaning; both begin with moral reconstruction. Through moral consciousness and moral courage behaviors, leaders become the focus and expand the problem of moral reconstruction, establish alliances, gain moral understanding with others, and enlarge the personal framework of leaders and followers into the common foundation of followers in the organization. Finally, a new moral order is established by regularizing the boundary of the moral system. Specifically, we propose that a moral leader is likely to be perceived as representing the core values of the group (that is, they will be perceived as prototypical)—more so than another leader who has other positive attributes. Evidence shows that group members’ evaluations of their groups, and their choice of which groups they want to belong to, are driven primarily by the group’s perceived morality (Leach et al., 2007).

Social entrepreneurship education and “moral leaders"

Estrin et al. (2013) reported that the higher the rate of social entrepreneurship in a country, the greater the spillover effect in improving social capital at the national level. One question is if the talent goal of social entrepreneurship is taken as the educational content, to which social welfare issues are added, will it be beneficial to cultivate the empathy and sympathy of college students to increase their motivation to creatively solve complex social problems and, thus, improve the intention of social entrepreneurship? Dees and Anderson, 2003, a professor at Harvard University, proposed that social entrepreneurship education is a process of “cultivating social entrepreneurs who can identify opportunities, make full use of existing resources and create social value.” Hence, it is an innovative way to cultivate talent with the goal of encouraging comprehensive and free development, arousing self-consciousness, and enhance their ontological significance, which embodies the unity of “survival” and “development” in Education (Yang, 2017).

From ancient times to the present, universities have acted as organizations that educate students to become “holistic.” In “playing a powerful role in the development of citizens who think and act morally” (Pascarella and Terenzini, 2005), the role of moral education in moral decision-making leads to moral efficacy, moral meaning, and moral courage (Pascarella and Terenzini, 2005; May et al., 2014). Education is carried out by setting courses, tutoring students (falls, 1991), directly imparting values (Moosmayer, 2012), and providing moral training for students and teachers (Kelley et al., 2006). Petriglieri and Petriglieri (2010) emphasize that the result of moral development is not purely for college life, but for life ambition, which adopts the epistemological standpoint of constructivism. Students’ moral beliefs are created, changed, and affirmed by their daily experiences. Collective meaning is produced by interactions, which are largely influenced by the language, culture, and environment of the member organizations.

Sum up

Our search revealed a relatively rich body of literature on social entrepreneurship, moral leaders, and meaning construction in public welfare entrepreneurship at home and abroad. Some studies have also researched the uniqueness of public welfare entrepreneurs, such as altruistic motivation, compassion, personal identity, self-efficacy, etc., which show the differences between social entrepreneurs and ordinary entrepreneurs.

However, the previous studies had some limitations: first, these mainly focused on the personal characteristics and entrepreneurial motivation of public entrepreneurs from a micro perspective rather than leader behavior in formulating their business. Second, the interaction mechanism between public welfare entrepreneurs and start-up public welfare organizations is not yet clear. Third, studies are scarce regarding its application in higher education, particularly regarding helping college students to develop themselves as moral leaders.

Research design

Research methods and case selection

Research methods

This study applied theory-driven case analysis to establish a framework based on existing theories and verified and developed the theory through case data. The research on the process of generating a “moral leader” in social entrepreneurship used the theory of personal meaning-making and compared the function and role of social entrepreneurship education. Therefore, we applied a double-case exploratory comparative research method. The main reasons were as follows:

① The theoretical basis of this study was the Sense-Making Theory, which is mature; moreover, research on “moral leaders” is not rare. However, this study is innovative in assessing social value through the behavior of public entrepreneurship. Therefore, the exploration of the growth process of “moral leader” in public entrepreneurship using the Sense-Making Theory is an exploratory study that applies mature theory to a new field.

② Research questions belong to the category of “how,” which are suitable for case studies to refine the theory and law behind the phenomenon and to present the integrity and dynamics of the research process (Yin, 2003). Within-case analysis and cross-case comparison allow an in-depth understanding of the diversity of public interest practices, which can help to confirm and supplement the same practice phenomenon to obtain more accurate and universal research.

③ Regarding the similarities and differences in the role of social entrepreneurship education on different “moral leaders” to realize the construction of personal meaning, the double-case method is used to analyze the similarities and differences between the two cases from self to organizational morality and assesses the impact of social entrepreneurship education on “moral leaders.”

Case selection

This study selected the YinChao Pension Service Center in Yinzhou District, Ningbo City, and the Ant Public Welfare Service Center in Yuyao City and their leaders as the case study objects, according to the model principle and the principle of sampling theory (Eisenhard and Graebner, 2007). The selection criteria were as follows: 1) Principle of sampling theory. The two enterprises are start-up private non-enterprise organizations registered in the Civil Affairs Bureau. The recognition of the person in charge as a “moral leader,” the process of participating in public entrepreneurship, the construction of their personal meaning, and the degree of social entrepreneurship education were used to explore the path of a “moral leader” in social entrepreneurship. 2) Model principle. Self-leading, key events, path choice, organizational interaction behavior, and social entrepreneurship education differed between the two leaders and were used for the comparative analysis of cooperation. 3) Convenience principle. The research team was familiar with the case objects and could observe the process of the case objects’ participation in social entrepreneurship. The public welfare organizations were willing to cooperate with the research to provide detailed data and multiple rounds of interviews; they were also willing to provide enterprise information and opportunities for on-site observation. The organizations also maintained contact and verified data to ensure the implementation of methodological triangulation. The following is a brief introduction to the basic situations of the cases.

Li Hui, a member of the all-China Youth Federation, a national outstanding member of the Communist Youth League, news person of the year of Zhejiang Education, Ningbo good man, and other honorary titles, was selected in the 2019 Forbes China under-30 elite list. In 2015, she set up “YinChao Pension Service Center,” and in 2017, when she was a junior, she registered “Ningbo Yinzhou District YinChao Pension Service Center” in the Yinzhou District Civil Affairs Bureau, which is the first non-governmental pension institution registered by a university student in Zhejiang Province. In the past 5 years, Li Hui led the team to establish 46 community service bases for the elderly and more than 30 colleges for senior citizens. The total service time of the team was >750,000 h. The project was awarded a gold medal in the China Youth Volunteer Service Public Entrepreneurship Competition and a silver medal in the China College Students’ Entrepreneurship Competition.

Xie Jie is a member of Yuyao CPPCC, general manager of Ningbo BoLizi Health Technology Co., Ltd., initiator of Ant Public Welfare, secretary general of the Leshan public welfare foundation, among the “good people in China,” and “good people in Zhejiang,” outstanding individual of Chinese youth volunteers, self-improvement model of Zhejiang Province, top-ten outstanding young people in Ningbo, Ningbo good man, one of “The Most Beautiful Ningbo People,” etc. “Ant Public Welfare” was established in 2015, with the tenet of “small ants, micro public welfare, big energy” and with the main business of helping the poor, assisting students, and providing emergency rescue.

Data collection

Data sources and collection methods

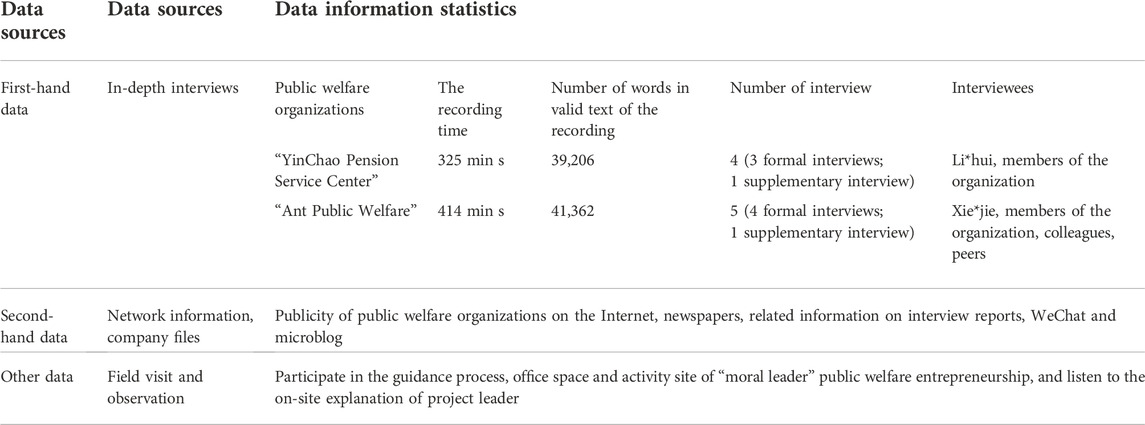

To improve the validity and reliability of the cases, this study mainly included three types of data sources: interview data, network data, and organizational records and field observation (Table 1), forming a “data triangle.” The interview data were mainly focused on the growth process of the founder of the public welfare organization. The interview process used the narrative history for reference to objectively describe the process. The public entrepreneurs’ self-awareness, education experience, key events, etc. were the key interview topics. For the process of public entrepreneurship education, we mainly considered the teachers’ process for cultivating public entrepreneurs, entrepreneurship education curriculum and environment in public schools, etc. The supplementary interviews focused on the partners, team members, and colleagues of “moral leaders” to describe the characteristics of entrepreneurs, the major events of behavior transformation, and the perception of participation in the educational process from a third-party perspective.

The network materials mainly included network propaganda, newspapers, and interview reports of the public welfare organizations. Combined with semi-participatory field observations, the research process mainly adopted a semi-structured interview method and used the interview framework to control the interview focus and rhythm. If new problems were identified, a supplementary interview link was added and the proposed additional questions were put forward to the interviewees who had been interviewed or other interviewees to avoid a disconnect in the interview outline due to the structural reality.

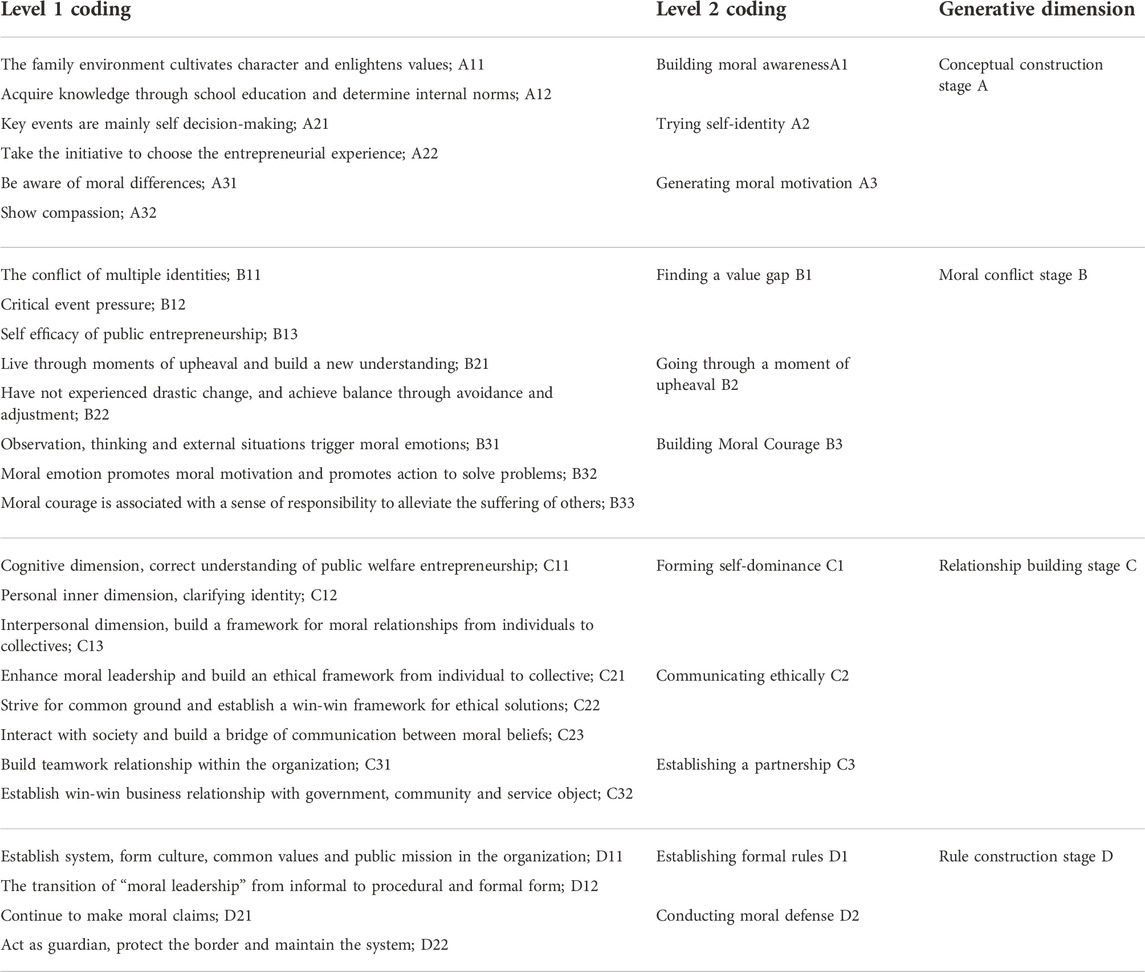

Data coding and data analysis

The text was analyzed according to the Strauss programmed grounded theory, “open coding—spindle coding—selective coding” data processing method (Wang, 2019). First, the materials were coded. In case 1, the recording data from Li * hui, related recording data, and second-hand data were coded as L; in case 2, the recording data of Xie * jie, related recording data, and second-hand data were coded as X. A total of 25 concepts were obtained by open coding (Table 2). Second, spindle coding was applied to refine and integrate the initial concepts, which resulted in 11 categories. Third, selective coding was applied. According to the relationship between different categories, four main categories were obtained, which formed the “storyline” of the grounded theoretical model. In the process of coding, the research team was divided into two groups to code independently back-to-back to ensure the reliability and validity of the results. Inconsistencies between groups were discussed to reach a consensus. During this process, if the information was not sufficient or the theoretical logic was not smooth, WeChat, e-mail, telephone, and other methods were used to quickly complete the supplement to revise and improve the research conclusion.

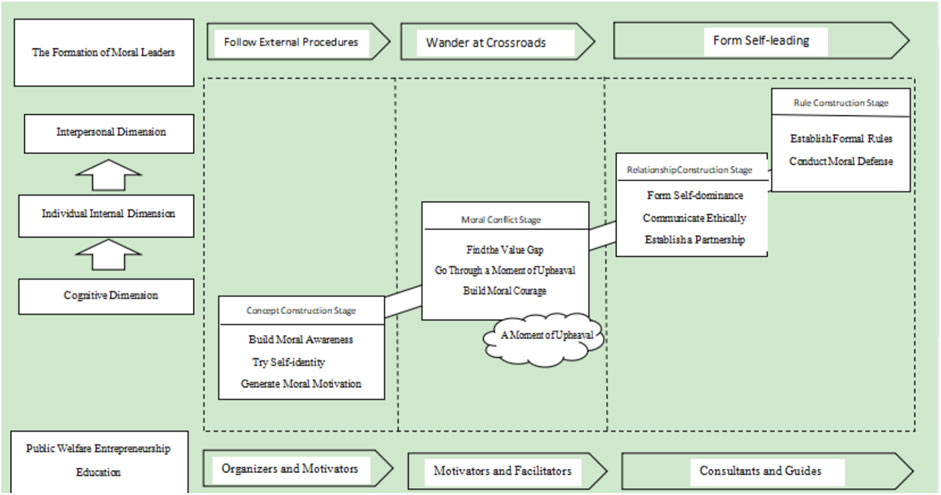

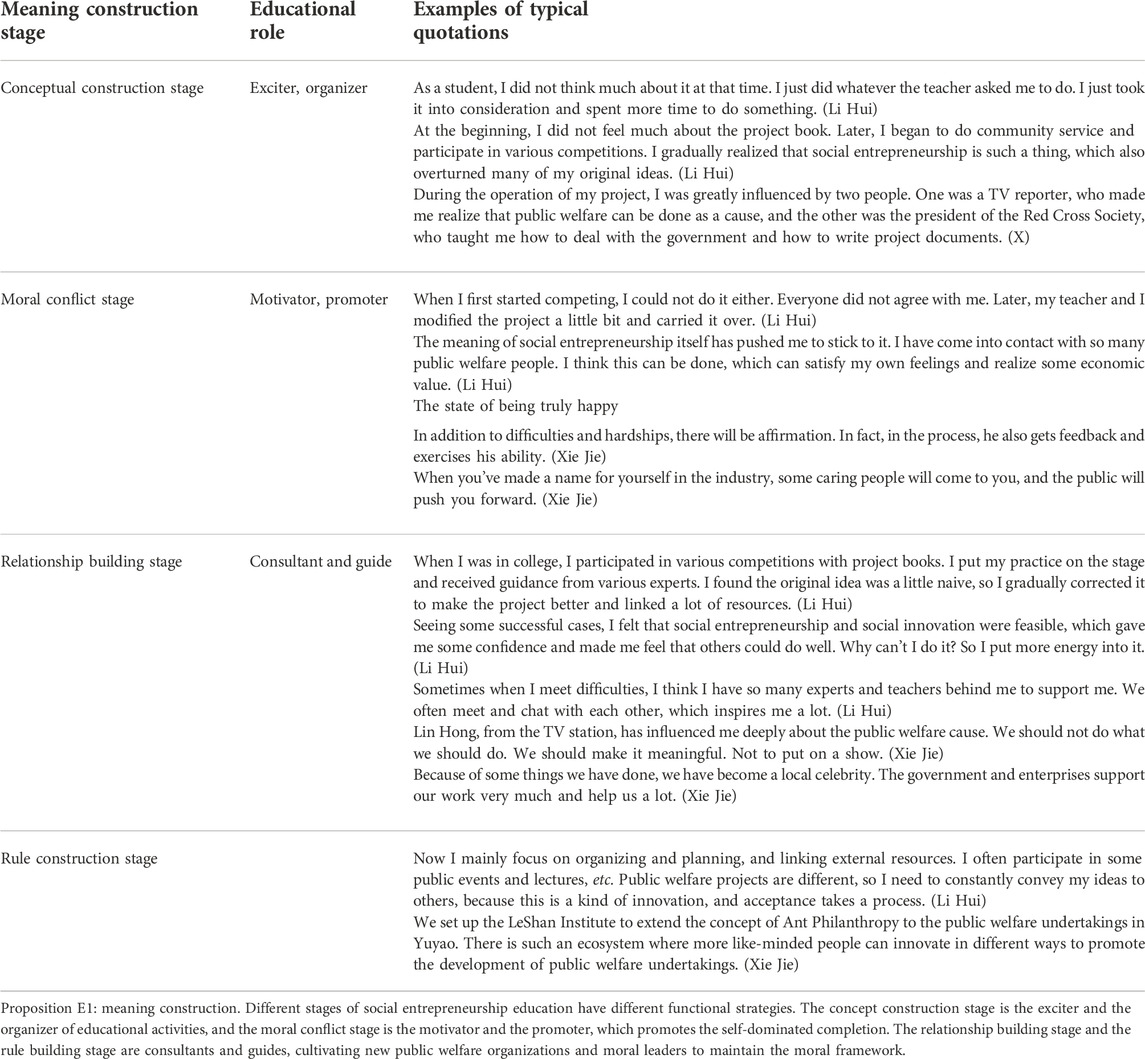

The results of the literature review and coding analysis identified the four stages of progression of the core categories in the emergence of “moral leaders” in public entrepreneurship: concept construction, moral conflict, relationship construction, and rule construction. Moreover, the meaning construction process moves from “following external procedures → wandering at crossroads → self-leading,” during which the key driving factors and public entrepreneurship education strategies promote the common growth of individuals and organizations.

Research findings

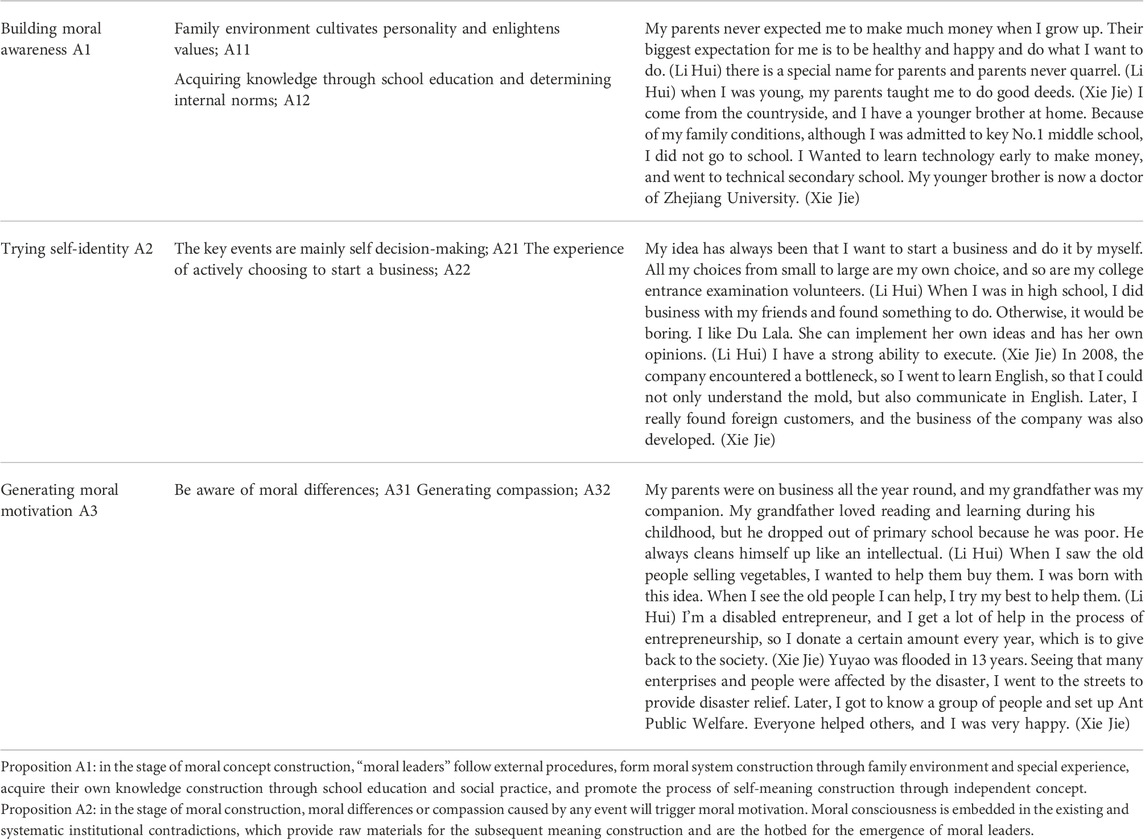

Construction stage of the concept of “moral leader”

In the conception-building stage, social entrepreneurs, from growth to the beginning of their careers, follow external procedures, base their decisions on social conventions, or ignore their own needs to meet perceived expectations (Kegan, 1994) (Table 3). This period is the key stage of establishing moral cognition and receiving education to determine internal norms and self. It is also the stage of the germination of moral consciousness and the generation of moral motivation. The comparative analysis of the case data revealed similarities between cases L and X in the initial concept establishment stage. Traditional Chinese families, harmonious family relationships, and good school education make it easier to cultivate the compassion of “moral leaders” and the moral consciousness of doing good for others.

TABLE 3. Examples of typical statements and related categories in the stage of concept construction.

Trying self-identity. Li Hui’s parents were busy with business and Xie Jie was the eldest son at home; therefore, both had more space for self-exploration while growing up. Since childhood, they had relatively strong subjective consciousnesses, were more active in doing things, and had strong executive abilities. Li Hui has had a business mind since childhood and liked to earn pocket money from her parents. She started doing business on WeChat when she was in high school. After an industrial injury in 2001, Xie Jie started his own business. When he encountered the bottleneck in 2008, he took the initiative to learn English and began to do foreign trade business. Both leaders showed entrepreneurial initiative. They also showed strong self-realization and a positive outlook on life, actively exploring the external world. However, the family environment and life experiences of Li Hui and Xie Jie differed, which influenced the formation of certain values; thus, their moral decisions were closely related to their futures. Li Hui had a good family background and a strong self-concept since childhood. The character “Du Lala” in the novel is independent, as her example and enlightening tutor, and the key events such as entering a higher school and starting a business are mainly self-decision-making. Because her parents were busy with work, she lived in the countryside when she was a child and was cared for by the old people in the village. Therefore, she has an innate sense of kindness toward old people. The experience of living with her grandfather as a child provided the raw materials for her moral motivation. Xie Jie’s family is ordinary, and his younger brother had a heavy financial burden. He gave up the college entrance examinations and went to technical secondary school. At 19 years of age, he became the director of the workshop. However, an accident led to the amputation of his right hand. After that, he started his own business and trained his brother to become a doctor at a famous school (Table 4).

Generating moral motivation. From moral awareness to moral motivation, not all problems are experienced morally (Tenbrunsel and Smith Crowe, 2008; Hannah et al., 2011). Any event with certain moral differences will trigger moral motivation. Moral consciousness is embedded in existing and systematic institutional contradictions, which provide raw materials for the subsequent meaning construction and are the hotbed of moral leaders (Seo and Creed, 2002; Wright et al., 2017).

Li Hui’s grandfather was eager to learn and accompany, so L later founded the YinChao Pension Service Center, hoping to help the elderly to have a richer and more high-quality life. Xie Jie’s original intention in public welfare projects was to give back to society. As a disabled person, he received help from many people around him in the process of entrepreneurship. He also did what he could to give back to society. Especially in Yuyao’s 2013 flood, he participated in the disaster relief team, which prompted him to start building a public welfare relief organization. This opportunity for him to set up a public welfare organization was a crisis event. Therefore, the gene of "Ant Public Welfare” is to give priority to the realization of social value. With the enthusiasm of “doing good,” it builds a rescue platform as a volunteer to serve society.

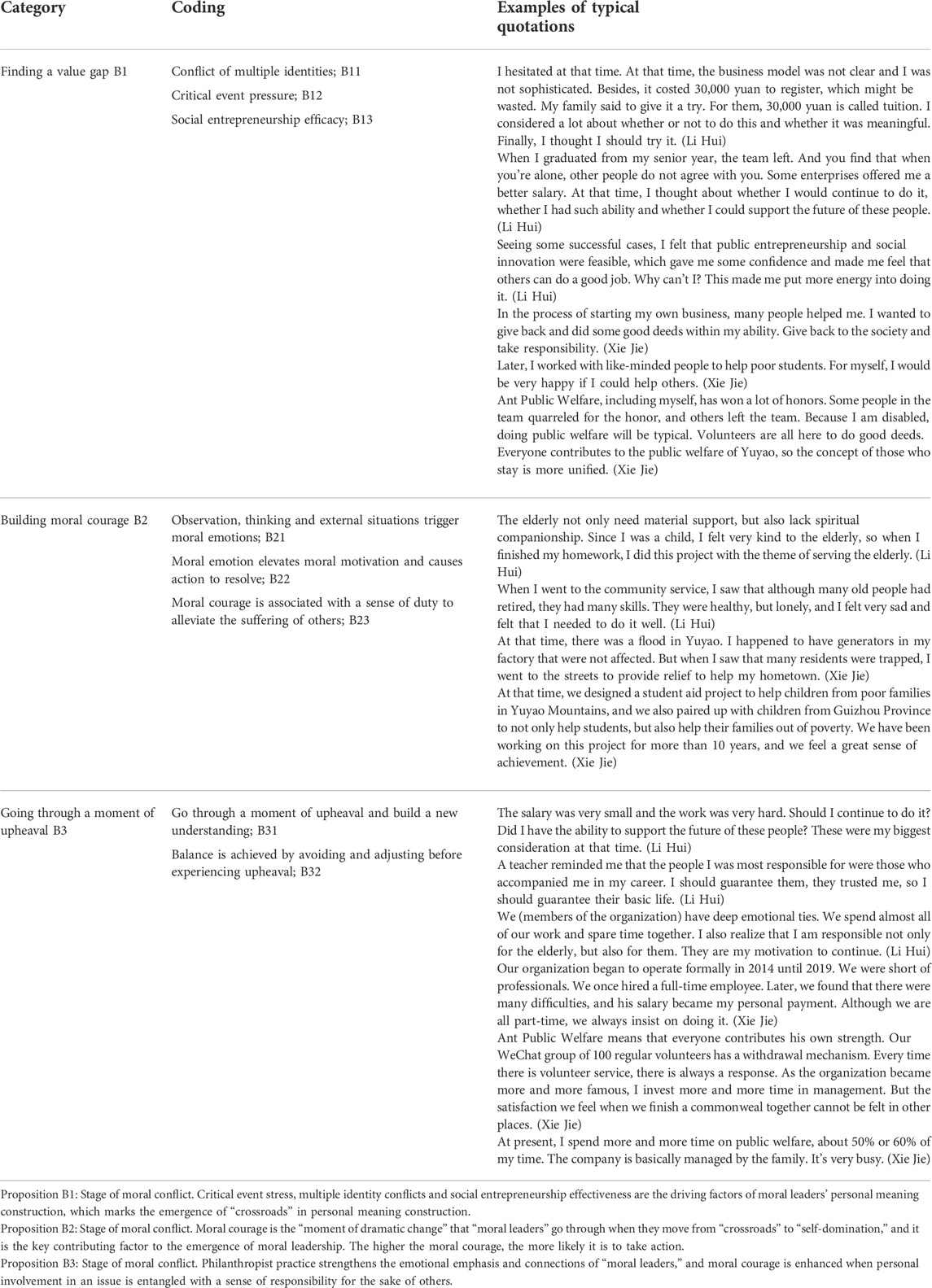

“Crossroads”—stage of moral conflict

When an individual enters the stage of moral conflict, their own purpose and meaning develop and conflict with the external authority, resulting in a tense relationship, between which they need to make a choice (Baxter Magolda, 2001). With the development of the practice of public welfare activities, there are new challenges and dilemmas for “moral leaders,” such as personal career choice (Li Hui), turnover of core team members (Li Hui), project implementation (Li Hui), project sustainability (Xie Jie), new platform (Xie Jie), etc. The emergence of differences or conflicts means the initiation of meaning generation. In the process of facing the key events, “moral leaders” identify the value gap, generate moral emotions, build moral courage, and finally realize relationship construction. “Moral leaders” first face the conflict of multiple identities and develop moral emotions and conflicts in the practice of public welfare. However, they cannot find a balance point in the relationship; therefore, they need to rebuild the relationship or find a new balance. Second, the key event is stress. Emotion can evaluate the stress event (Crystal and George, 2013) and the meaning construction process will be re-expressed to accept this situation in different ways (Folkman and Moskowitz, 2007). Third, “moral leaders” require entrepreneurial efficacy. For example, in 2017, the “YinChao Pension Service Center” faced organization registration, and L needed to determine whether it was worth investing money and time to continue to support the moral choice. In 2018, L was faced with graduation, while members of the organization were faced with breaking up. For L, on the one hand, it is her own conflict—the choice of career direction, support of physical problems, strong opposition and from parents; on the other hand, it is an assessment of the future of the organization—the project itself and the way out for team members.

The examples of Li Hui and Xie Jie show that the motivation to trigger moral consciousness and change the current situation is not only a simple observation but also abstract thinking. The external situation can also trigger strong moral emotions. “Emotion is an individual’s goal, motivation, or concern in response to an important event.” For example, sympathy, guilt, shame, pride, disgust, etc. these emotions, in turn, make individuals redefine as “wrong” moral problems, which must be solved by action. Moral motivation becomes stronger and individuals are motivated to change the current situation and solve their inner discomfort (Meyerson and Scully, 1995; Creed et al., 2010; Gutierrez et al., 2010; Voronov and Yorks, 2015). For example, when Li Hui saw the lonely old life of “Granny Xue,” she wanted to continue her cause for the elderly, establish a public welfare organization concerned about the spiritual life of the elderly, and promote the concept of active pension. When Xie Jie encountered the flood disaster in his hometown, he joined the rescue and later established a public welfare assistance project. Unexpected events stimulated his sense of responsibility to give back to society, and also balanced his internal conflicts.

“Crossroads” refers to the tense relationship between the outside and individuals, who must develop their own beliefs or reconstruct their identities in response (Baxter Magolda, 2001). “Crossroads” is the key period to promote self-leadership during which individuals address the challenges in their growth process and conflict with the construction established in the past. They need to consider multiple perspectives to choose their real inner construction. Under critical pressure events, “moral leaders” begin to seriously consider what kind of people they want to be and what kind of life they want to live. They walk out of the development stage of “following the external program” and enter the “crossroads” to stimulate moral emotions and rebuild self-identity. For example, after Xie Jie was disabled due to work, he gave up the Taiwan-funded enterprises that he originally depended on to survive and took the initiative to start his own business. After receiving help from the outside society, he actively fed back the society. The Yuyao flood in 2013 inspired him to register Ant Public Welfare, while the support of the government and the Bank of Agriculture and Commerce prompted him to join the LeShan Commonwealth College.

Not all people who go through the “crossroads” will achieve self-leading. The “cataclysmic moment” is a critical moment for the emergence of self-leading (Pizzolato, 2003). This kind of experience can promote individuals to seek inner self-definitions to solve the cognition imbalance and establish a new cognition with behavior (Pizzolato, 2005). Self-leading achieves a kind of cognitive balance, which some people achieve by avoiding or compensating (Table 5,6).

TABLE 5. Examples of typical statements and related categories in the stage of relation construction.

The first conflict and contradiction Xie Jie encountered at the “crossroads” was the key event pressure. Multiple identity conflicts and self-efficacy of public entrepreneurship continued to appear in the process of entrepreneurship. For example, Xie Jie had a main business, and public welfare activities required half of his working time. How to balance them? The revenue and expenditure of “Ant Public Welfare” were not stable and it was unable to operate as an enterprise; how, then, to develop it sustainably? A kind of moral motivation urges “moral leaders” to adhere to special action tendencies even in the face of risk, opposition, and fear (Hannah et al., 2011). This is a tendency of action, which means that over time, people may change or may act as an interlude in the process, showing a lack of courage, or they may establish moral triggers in the individual and organizational environments. With increasing participation, moral courage will be entangled with the sense of responsibility to alleviate the suffering of others. Research shows that individuals are more likely to commit to an altruistic initiative. While personal pain may only be tolerated, the pain of others brings feelings of guilt. Individuals may choose to maintain their own moral standards to get rid of the guilt (Cormack, 2002; Bastian et al., 2011; Inbar, et al., 2013). The courage to take responsibility and think for others can enhance a person’s positive self-image (Cormack, 2002; Oliner, 2003). When moral courage, moral motivation, and a sense of responsibility are established, others will follow and improve to a higher level of moral organization operation in an interactive process. The interaction with followers will also strengthen the determination of “moral leaders” to change the existing framework to resonate with followers, challenge the original framework, face risks together, share experiences, strengthen the courage of moral leadership, and avoid disappointing followers. While starting a business, Li Hui has repeatedly stressed that the team’s partners are her driving force, in addition to her responsibility to the elderly and the team as the person in charge (Table 7). After the establishment of the organization, the strength of the organization also bolsters Xie Jie’s moral courage and X also invests more time in public welfare.

TABLE 7. Examples of typical statements regarding the roles of public welfare entrepreneurship education in different stages of meaning construction.

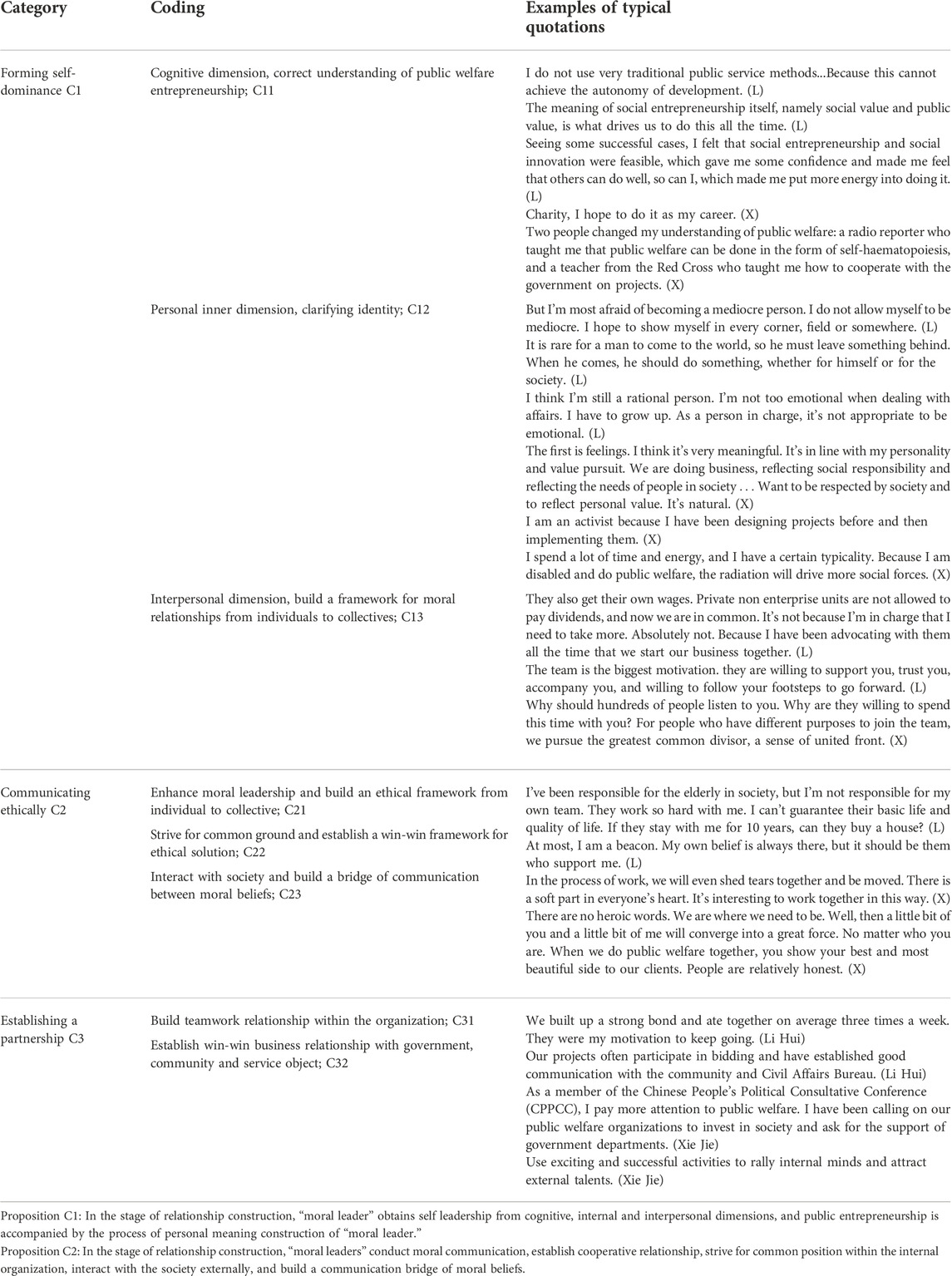

The construction stage of the “moral leader” relationship

“Moral leaders” go through the crossroad and enter the relationship-building stage, in which their experiences and abilities improve and they are self-dominant and critically self-reflective. This is the moral development stage of “moral leaders” and the formation stage of “self-dominant.” Self-leading calls for “moral leaders” to “get rid of external influence, build knowledgeability, build internal identity and effectively participate in social relations” (Baxter Magolda, 1999). Usually, three dimensions; namely, epistemological, individual inner, and interpersonal dimensions, are used to judge the formation of self-dominance, which is the goal of personal meaning construction (Kegan, 1994). The cognitive dimension refers to people’s understanding of the essence of knowledge. The cognitive maturity required for decision-making by integrating different information needs a self-dominated belief system (Baxter Magolda, 2004) Table 8. In the dimension of epistemology, “moral leaders” truly realize the innovation, dual value, and future prospects of public entrepreneurship, and form a self dominated cognitive system. When Li Hui was in university, she learned the theoretical knowledge of public entrepreneurship. Through her participation in competitions and community services, she clarified the understanding of the value of public entrepreneurship and evaluated the feasibility of the cause by linking resources. Xie Jie’s public welfare activities began with volunteer activities. Through contact with social public welfare platforms, governments, and professionals, Xie Jie gradually understood public welfare entrepreneurship.

The internal dimension of individuals is the use of cognition to construct beliefs and identities (Abes et al., 2007). Self-dominated people determine lasting values through reflection and build stable identities, which are not affected by external expectations. In the internal dimension of individuals, “moral leaders” clarify identity, the leaders of public welfare organizations, the participants of social problems, and the leaders of innovative problem-solving frameworks. Li Hui has a strong sense of self-leadership. After engaging in public welfare entrepreneurship, her sense of self-efficacy has also enhanced its confidence. Moreover, her entrepreneurial mindset enables her to rationally evaluate the feasibility of public welfare projects. In the practice of public welfare, Xie Jie found a sense of harmony that reflected his own values and used his previous experience in business entrepreneurship to execute projects and lead a team.

The interpersonal dimension is the ability to live in harmony with oneself, others, and other social relationships (Kegan, 1994). Regarding the interpersonal dimension, “moral leaders” promote moral leadership and build the framework of moral relationships from the individual to the collective. “Moral leaders” begin to build teams as social entrepreneurs and accumulate social network connections in the process of building personal meaning. “Moral leaders” adjust their beliefs and other people’s moral concepts according to the substantial moral foundation. Combining the views of different followers, they strive for preliminary common positions and establish a new moral solution as a common definition of “collective moral framework.” Moral leaders must successfully bridge their own moral beliefs with those of others, which depends on their communication and persuasion skills and how they interact with society.

The moral foundation of Ant Public Welfare is that “little ants are the great energy of public welfare.” Everyone contributes a little to become a collective great energy and make a great cause of public welfare. The volunteers who participate in the project have different intentions and purposes, and there will be contradictions and conflicts such as the distribution of personal honor, the embodiment of team value, etc. While Xie Jie constantly emphasizes the concept and value of the team, he also seeks common ground while setting aside differences to maximize support. Common experiences are another way to build links.

We find it difficult to build a strong enough following system with a single and self-frame. They will accommodate part of the framework into their own framework or present a more abstract framework (Gray et al., 2015). This creative fusion and pre-existing meaning become part of the attractive overall framework, creating a win-win situation. The new moral framework is not only worthy of the support of followers but also widely spread by followers. For example, in the initial stage of designing “YinChao caring for the old,” Li Hui proposed to actively provide for the aged, promote the value, and provide an employment platform for the elderly. After integrating the framework including the needs for living, learning, and dignity, such as the transformation of the environment suitable for the elderly and YinChao University for the elderly, Li Hui upgraded the concept of “YinChao caring for the old” to “YinChao future.” Caring for the old is positive; however, our common yearning for the elderly life may attract more social forces and partners to join in old-age care. However, the new framework also has the risk of being considered a compromise. If it is loosely coupled in daily practice, it lacks behavior integrity and moral consistency in people’s eyes, thus challenging the moral authority of leaders and maintaining the moral framework (Ramus et al., 2017). For example, although “Ant Public Welfare” was founded in 2015, its organizational form has been relatively loose. It is mainly based on project operation and volunteer management and has not formed an enterprise-oriented management system and organizational form. Therefore, it still lacks full-time staff and the flow of volunteers is relatively large.

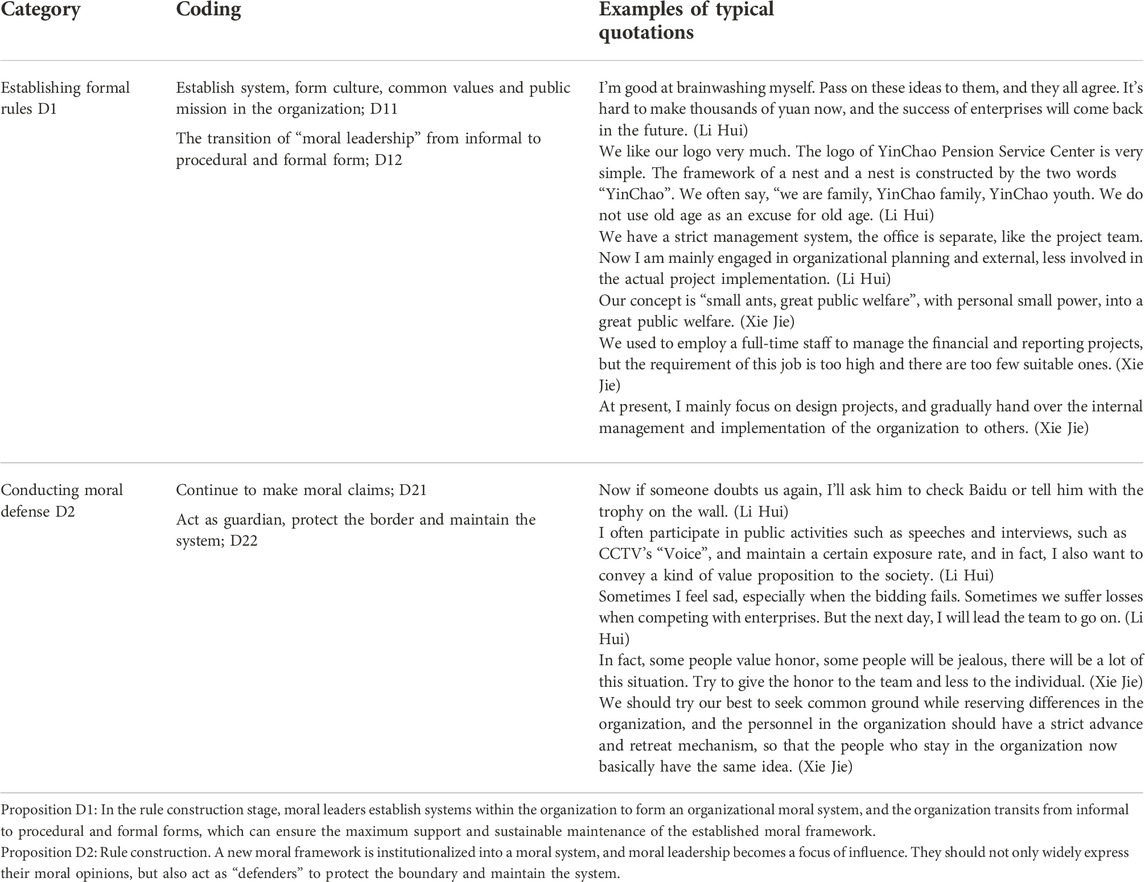

Rule construction stage of “moral leaders”

The solidification stage of the new moral framework of “moral leader” involves reaching an agreed vision, establishing an organizational system, forming an organizational culture, sharing common values and public missions, and providing sustainable development. This stage is the construction of the moral framework of the “moral leader” from the individual to the collective. Emerging moral leaders need to continue to express, embody and symbolize shared values as a new moral framework, actively weaving invisible “moral structures.” Followers can identify, relate, and then form experiences and behaviors in themselves to interact with others.

In addition to building a vision within the organization, establishing an organizational system, forming an organizational culture, and recruiting talents suitable for the characteristics of the organization, Li Hui also extensively participates in various influential public activities, such as CCTV’s “Voice” program, and also participates in the evaluation of the Forbes youth list and lectures and forums within universities and community organizations to establish contacts and resonate through a wider range of social discourse. For example, in terms of organizational vision, Li Hui conveys sustainable and social values and opens a window for elderly life services in an aging society, thus showing huge market potential. It also widely accepts the emerging moral framework for the government and society and is willing to invest resources. In the construction of organizational culture, the YinChao Pension Service Center uses a unified logo and slogan to emphasize its significance. In the construction of Ant Public Welfare, Xie Jie has not yet formed a sustainable enterprise operation; however, the expansion of its moral framework is more reflected in its connection with government, foundation, and other resources. Yuyao Leshan Public Welfare Class is an upgrade on the original public welfare framework, training public welfare talents in the Yuyao area and forming a public welfare ecosystem. It is an extension of his moral framework to gain more followers.

Change leadership also eventually becomes traditional and rationalized, which means that moral leadership also transitions from informal to more procedural and formalized forms (DeRue and Ashford, 2010). Leaders and followers in the organization work together on formalization, rule-making, incentive schemes, etc. (Smith-Crowe et al., 2015). For example, the “YinChao Pension Service Center” specialized the office as an independent department responsible for internal system formulation, personnel assessment, etc. This allowed the organization to reduce unnecessary burdens and focus on self-development and running the business. Without institutionalization or formalization, it is difficult to ensure that members of an organization maintain the same level of moral awareness; thus, they may lose interest or invest less time.

Moral leadership can be defined as a process in which a person becomes a focus of influence. After a new moral framework is established and institutionalized into a moral system, “moral leadership” acts as a guardian, maintaining the boundaries around the moral system (Maak and Pless, 2006). The purpose is to ensure the integrity of its newly established moral framework and the stable moral identity of a group. The framework will still be unstable, requiring moral leadership for intermittent behaviors; otherwise, the moral system may erode due to followers’ selfishness and other manifestations of motivation. When the system is in danger, moral leadership must serve as a beacon of recognition that allows followers to continue to pledge their own shared values and existing moral systems. At the same time, moral leaders must also strike a balance between development and maintaining control. Whether they keep in mind moral values and forget to build relationships, or they are too easily swayed by current developments and not sufficiently rooted in moral beliefs, both can affect the development of moral systems. Moral leaders protect and maintain the newly established moral framework and support others’ voluntary participation in the moral system to develop and articulate their own subjective experiences and actions. Moral systems are not tools for propaganda or persuasion but rather are used by followers as a medium for personal moral development. Thus, a moral leader must act as a manager of the character development process, engaging in a fair exchange of values with others, and sometimes as a “guardian” willing to maintain the boundaries of the moral system after interacting with others. This self-perpetuation is a key feature of the institutionalization of moral systems and has always been rooted in the interactions between leaders and followers.

The function and strategy of public entrepreneurship education

Both cases in this study received social entrepreneurship education. Effective social entrepreneurship education can influence the attitude and behavior of “moral leaders,” toward a strong desire for social entrepreneurship and the ability to act. Combined with the process of constructing personal meaning and from the perspective of cultivating “moral leaders,” we discuss the role of social entrepreneurship education for college students for each stage of the generation of “moral leaders” and what strategies to adopt for further discussion.

In the conceptual construction stage, the behavioral strategies of educators are organizers and motivators, helping leaders to create organizations and obtain innovative solutions, providing cases to follow, and committing themselves to innovative solutions to various social problems. In the concept-building stage, Li Hui was exposed to the concept of social entrepreneurship in courses after entering college. She wrote the first project book on social entrepreneurship through course assignments and formed the initial team for the “YinChao Pension Service Center” project. At that time, the goal of social entrepreneurship was not clear. At the very beginning of her participation in social entrepreneurship, she was also passively required to complete her homework. Her moral awareness at a young age provided a fertile ground for her project direction. The social entrepreneurship education curriculum of the school provided a good entrepreneurial knowledge system, which made her design of the initial project double-oriented with commercial and social values, and enabled her to see the long-term development. In the process of knowledge construction, Li Hui also participated in various competitions and projects. “We must practice.” Li Hui’s practice was a crucial step for her to understand public welfare and develop moral awareness. The entrepreneurship competitions provided a platform for her to open her mind and broaden her resources. Thus, the construction of identity was closely related to the belief constructed by knowledge (Abes et al., 2007).

In contrast, Xie Jie was exposed to social entrepreneurship education in the relationship-building stage. Xie Jie first implemented the project with a volunteer team and registered a private non-enterprise organization with the support of the government and foundations. He learned about social entrepreneurship mainly from social resources such as the Red Cross and news media, and then systematically learned more after receiving training in a public welfare talent class. It has been said that practice precedes theory. His organization, which is oriented toward the realization of social values, is having difficulties in hiring full-time staff and advancing as an enterprise.

At the stage of moral conflict at the crossroads, educators become the motivators, facilitators, and external positive forces of “moral leaders” to complete their self-dominance. Students gradually develop an identity. On the one hand, they can learn from typical characters and imitate their identities to become social entrepreneurs with a sense of social responsibility and innovative ability. On the other hand, e can provide students with opportunities to practice social entrepreneurship. When ethical leaders engage in concrete, vivid social entrepreneurship practices, their underlying abilities are demonstrated, and their identity is strengthened. In the early stage of practice, students may be provided service work or simple public welfare projects, while the commercial link is relatively diluted. This is like the model of “service learning,” which can help students understand the content of the course, improve their reflective cognitive ability, and strengthen their moral awareness. In the process of practice, “moral leaders” strengthen their identity, deepen their emotional involvement, invest time and experience, elevate their moral emotions to moral motivation, and further establish a strong will to solve social problems by participating in social entrepreneurship activities.

“Moral leaders” reconstruct social networks and acquire entrepreneurial ability through behavioral investments. With the deepening of practice, “moral leaders” begin to engage in moral input, including behavioral, cognitive, and emotional inputs. For example, Li Hui linked to various platforms and resources such as the government and foundations while participating in a public welfare competition. From the initiator of “Ant Public Welfare” to the secretary general of “Leshan Foundation,” Xie Jie has gradually changed his perception of public welfare during his public welfare practice. The organization and individuals have grown through this relationship reconstruction. “Moral leaders” gain a clearer self-awareness through emotional engagement, take public welfare as a cause, aim to be a public welfare entrepreneur, and experience the emotional changes in the early stages of entrepreneurship. For example, Li Hui gets confidence from the organization and feels frustrated when team members leave. When confronted with conflicting opinions within the organization and criticism of himself, Xie Jie seeks common ground while shelving differences, with negative and positive emotions mixed in the process, while also recognizing the spirit of social entrepreneurship.

The relationship-building and rule-building stages really enter the practice stage of social entrepreneurship, in which educators play roles as consultants and guides rather than authorities (Mezirow, 1997). “Moral leaders” take on the challenge of higher-order thinking in the entrepreneurial process to analyze, integrate, apply, evaluate and innovate, and develop new ideas to solve challenges. The most effective way to progress is to participate in various social entrepreneurship competitions.

Public welfare educators at this stage are like the team mechanism or mentor-led project forms of public interest institutes, which enable the mutual circulation of public interest resources within the platform. Social entrepreneurs and educators are more like collaborators and coaches. The teachers primarily act as mentors and positive role models, while university administrators and staff are seen as helpful supporters who perceive positive moral values and role models. In this stage, educators of these two stages mainly play the role of partners, discussing learning together and helping to link resources.

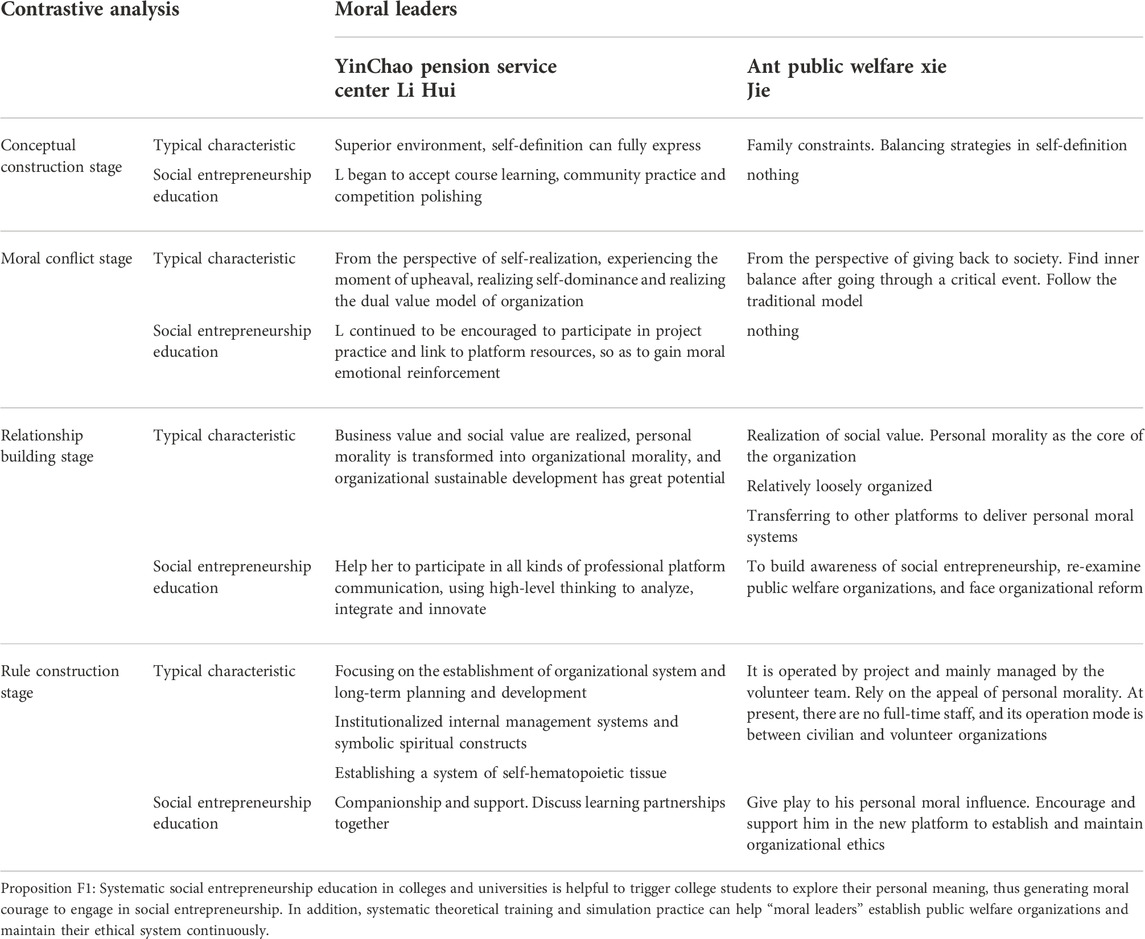

Cross-case comparative analysis of the impact of public entrepreneurship education on “moral leaders"

The case objects in this study were college students who had received higher education. However, due to different growth environments, stages of receiving social entrepreneurship education, and environments for implementing social entrepreneurship, the students differed greatly. Before setting up the organization, Li Hui had received education on systematic theories and practices of social entrepreneurship, including course assignments, community practice, competitions on social entrepreneurship (registration and landing), and expert team guidance. She started social entrepreneurship in her junior year and set the dual goals of realizing business and social values at the very beginning of the organization. Xie Jie participated in volunteer service in the community after practicing business entrepreneurship before establishing an organization. He later received social entrepreneurship education, which was a process of exploring while practicing. His theoretical learning occurred in stages, including voluntary service, government recognition (registration and implementation), LeShan Charity Institute, expert guidance, etc. Therefore, the gene of Ant Public Welfare is a voluntary organization derived from voluntary service and charity activities. The organization was initially set with the priority of social values and had strong government guidance.

Among the four stages of constructing personal meaning, we further compared the impact of social entrepreneurship education on the construction of personal meaning for these “moral leaders.” We found that the two “moral leaders” had the same experiences in establishing moral cognition and trying to define themselves in the concept construction stage. Li Hui grew up in a relatively superior environment and had greater autonomy to realize the path of self-definition. Xie Jie, restricted by his family environment, adopted a balanced strategy at the beginning. However, both had the same moral motivation for feeling empathy in critical situations. Li Hui received entrepreneurship education, as the organizer and excitation in her university stage provided the theory courses. In addition, she performed simulation projects in the community, which provided front-line practice opportunities and basic market data at a low cost. She also participated in public interest competitions, practiced expert projects, and learned about public welfare on a high platform, thus building a sound entrepreneurial knowledge system and social entrepreneurship concept. Although social entrepreneurship is a zero-to-one process, often starting from scratch, the low cost of theoretical and practical input provides a solid foundation for building a start-up organization and a good window for individuals and teams to build connections. In contrast, Xie Jie was driven by a moral motivation to establish a public welfare organization; however, his understanding of the concept of social entrepreneurship was limited. At the beginning of its establishment, the organization was entirely a volunteer activity that mainly relied on the government to support its operating costs. Such organizational genes are greatly uncertain as to whether they can be put into market operation as social entrepreneurship organizations in the future.

At the stage of moral conflict at the crossroads, the two “moral leaders” were conflicted by multiple identities. As a motivator and enabler, social entrepreneurship education serves as a mentor on the path of social entrepreneurs and continues to strengthen the realization of the higher personal meaning of “moral leaders” to promote moments of upheaval. Li Hui came to a crossroads when disbanding her team, experiencing health problems, and the lure of other perks. This phase emphasizes “moral leader” in the practice of the public and should establish and strengthen the sense of moral emotions such as responsibility and self-efficacy. At the same time, they should continue to provide high-quality professional materials in the field of social entrepreneurship and creative solutions to social problems and the link of personal meaning realization, thus eventually forming a firm inner moral system and complete self-guidance. In contrast, Xie Jie established a public welfare organization mainly from the perspective of rewarding society. When public welfare projects conflicted with work and family, Xie Jie mainly adopted the traditional model, which required negotiation with family members and even funding the public welfare projects with his own salary. He was exhausted as he tried to balance his work with public welfare projects. Moreover, the participants of the volunteer projects came from complex sources with different goals and they eventually left the team because of the unfair distribution of personal honors. From the perspective of social entrepreneurship, X has not established an effective organizational ethics system but is seeking balance.

In the relationship-building stage, “moral leaders” continuously communicate with themselves, the organization, and the society morally to establish cooperative relationships. Li Hui set the goal of the enterprise operation of the “YinChao Pension Service Center” to establish customer relationships with the government and service objects, constantly output moral beliefs, and innovate project models to allow for a greater development space for the organization. Li Hui has also started to run a public welfare organization independently, using high-level thinking to analyze, integrate, and innovate. At this stage, social entrepreneurship education is just a relationship between cooperation and coaching, a teacher to answer questions and doubts, and a gas station for career promotion. However, for Xie Jie, it was during the relationship-building stage that he really became familiar with social entrepreneurship. Previously, “Ant Public Welfare” was largely dependent on government funding and had good social benefits. It focused on establishing relationships between the government and the media and was managed loosely by volunteers. As a “moral leader,” Xie Jie could not complete the transition from “personal ethics” to “organizational ethics” in “Ant Public Welfare.” It was not until he joined the larger public welfare platform “LeShan Charity Foundation” that he had the platform to continue to give play to his moral beliefs and participate in social public welfare innovation.

In the rule construction stage, “moral leaders” exert moral leadership within the organization; however, the internal construction of public interest organizations may differ. Li Hui continues to dig deep into the operational mechanism of public welfare organizations. The YinChao Pension Service Center focuses on establishing an organizational system and long-term planning and development toward a consistent moral identity, institutionalized internal management system, and symbolic spiritual constructs within the organization. With nearly 20 full-time employees, it has completed the transformation from personal to organizational ethics and has established a self-hematopoietic organizational system. Currently, the educator is a partner and companion, and Li Hui is fully capable of independently carrying out social entrepreneurship. She gradually became an expert in this field, expressing her views on various platforms, and guiding and influencing other people in the same industry. In contrast, Xie Jie’s “Ant Public Welfare” is run as a project, mainly relying on the management of volunteer teams and project design and implementation, while the “moral leader” relies more on the appeal of personal morality. At present, “Ant Public Welfare” has no full-time staff and its operation mode is between non-government and volunteer organizations; thus, its development has encountered serious bottlenecks. Although Xie Jie has become the head of another public welfare organization, Ant Charity faces many difficulties and a bumpy road ahead.

Conclusion

From the theoretical perspective of constructing personal meaning, through field interviews and relevant data collection of the founders and organizations of two public welfare organizations, this studies applied grounded theory to conduct a double-case study to explain the process of the emergence of “moral leaders,” reveal the internal relationship and mechanism between moral leaders and public welfare organizations, and discuss the role and strategy of social entrepreneurship education at various stages.

The results showed that the development of a “moral leader” can be divided into four stages, namely, concept construction, moral conflict, relationship construction, and rule construction. In the first stage, the “moral leader” follows the external program, which is the process of an individual acquiring knowledge, defining self, and generating moral motivation to realize the concept construction as a theorist. Second, when “moral leaders” are at a crossroads, they find the value gap at the individual level, build moral courage, and experience a moment of drastic change. This is also the stage of conflict at the individual level. The final stage involves the construction of self-leadership and rules. Externally consistent modes or forms of self-leading, as well as cooperative relationships, are established in this stage, in addition to conducting moral communication and formalization and institutionalization within the organization. “Moral leaders” as practitioners establish formal rules at the organizational level, carry out moral maintenance, achieve individual leadership of the cognitive, individual internal, and interpersonal dimensions, develop “personal morality” into “organizational morality,” and become “moral leaders” in the organization. This study also discussed the functions and educational strategies of public entrepreneurship education in the context of the four stages of “moral leader” development (concept construction, moral conflict, relationship construction, and rule construction), public entrepreneurship education takes on the roles of motivator, inspiration, consultant, and guide, respectively, to promote awareness of public welfare by the “moral leader” and put it into action. The results of the above analysis informed our development of a “moral leader development model based on personal meaning,” as shown in Figure 1.

Theoretical contribution

Through the systematic analysis of the stages and elements of “moral leader” personal meaning construction, this study focuses on the process of “moral leader” development to reveal the process of “moral leader” personal growth to organizational transition. Specifically, this study 1) explains the driving and strategic factors in the process of constructing the personal meaning of “moral leaders.” In the process of public welfare entrepreneurship, finding the value gap, building moral courage, and experiencing a “cataclysmic moment” coincide with the view of Pizzolato (2005) that self-leadership needs to experience a “cataclysmic moment,” and is also the key stage in the emergence of “moral leaders.” 2) This study explains the process of developing a “moral leader” from personal growth to organizational moral transition and from the three dimensions of self-leading and moral communication, to the establishment of formal rules and moral maintenance, which theoretically extends research on the relationship between “moral leader” from individual to organization. 3) Finally, this study explains the role and function of social entrepreneurship education in the process of constructing the personal meaning of “moral leaders” and elucidates the mechanism by which the education process affects students’ ethical concepts and entrepreneurial ability. Thus, the multi-dimensional identity model provides examples of the construction of personal meaning in “moral leaders”.

Practical contribution

In addition to its theoretical contributions, this study also has significance as a reference for the personal growth of public entrepreneurs, the start-up of public organizations, and the practice of public entrepreneurship education. This article 1) provides a learning path for the self-exploration of personal growth, especially stimulating the self-realization of exploring inner meaning. Social entrepreneurship serves as a path for reference and choice. Thus, social entrepreneurship education, as a learning course to explore such meaning in college, can help individuals establish a good internal “moral system.” 2) This article also addresses how social entrepreneurs can play the role of “moral leaders” in new public welfare organizations, how to develop personal ethics into organizational ethics, and how social entrepreneurs can become the driving force of social practice and innovation to help new public welfare organizations find a foothold in the market and enter sustainable development. 3) Finally, this article provides theoretical basis and method reference for the practice of social entrepreneurship education, proposes the content and method of education from the perspective of constructing personal meaning, and effectively improves the connotation and effects of social entrepreneurship education.

Future research directions

This study can be further explored as follows: 1) Start-up social entrepreneurship projects can continue to be selected as samples to demonstrate the interaction mechanism between “moral leaders” and organizations. 2) A dynamic follow-up study can be performed on the cases to further study the deepening factors of the interaction between “moral leaders” and the organization and the interaction between “moral leaders” and the organization after the social entrepreneurship project enters the development period. 3) Further exploration of the educational strategies, analysis of the factors related to strategies, and exploration of effective paths for the growth of “moral leaders” could also be performed.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SZ and JL wrote the original draft. JL supervised and reviewed the manuscript. HZ and ML collected and analyzed data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend deep gratitude to Jia Li who has offered a lot of help and support in the process of writing this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abend, G. (2014). The moral background: An inquiry into the history of business ethics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Abes, E. S., Jones, S., and McEwen, M. K. (2007). Reconceptualizing the Model of Multiple Dimensions of Identity: The Role of Meaning-Making Capacity in the Construction of Multiple Identities. Journal of College Student 48 1–22.

Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., and Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Acad. Manage. Rev. 25, 472–491. doi:10.5465/amr.2000.3363315

Austin, J., Stevenson, H., and Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepreneursh. Theory Pract. 30, 1–22. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00107.x

Bacqa, S., and Altb, E. (2018). Feeling capable and valued: A prosocial perspective on the link between empathy and social entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 33, 333–350. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.01.004

Bastian, B., Jetten, J., and Fasoli, F. (2011). Cleansing the soul by hurting the flesh: The guilt-reducing effect of pain. Psychol. Sci. 22, 334–335. doi:10.1177/0956797610397058

Baxter Magolda, M. B. (1999). Creating contexts for learning and self-authorship: Constructive developmental pedagogy. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Baxter Magolda, M. B., King, P. M., Taylor, K. B., and Wakefield, K. (2012). Decreasing authority dependence during the first year of college. J. Coll. Student Dev. 53 (3), 418–435. doi:10.1353/csd.2012.0040

Baxter Magolda, M. B. (2001). Making their own way: Narratives for transforming higher education to promote self-development. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Baxter Magolda, M. B. (2004). “Self-authorship as the common goal of 21st century education,” in Learning partnerships: Theory and models of practice to educate for self-authorship (Sterling, VA: Stylus), 1–35.

Boltanski, L., and Thevenot, L. (2006). On justification: Economies of worth. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brown, M. E., and Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 17, 595–616. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

Camerer, C. F., and Fehr, E. (2006). When does “economic man” dominate social behavior? Science 311, 47–52. doi:10.1126/science.1110600

Cardon, M. S., Wincent, J., Singh, J., and Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Acad. Manage. Rev. 34, 511–532. doi:10.5465/amr.2009.40633190

Cen, Y. H. (2016). Pyramid model of college students' growth - local student development theory based on empirical research. J. High. Educ. 10 , 74–80.

Cen, Y. (2014). Student development in undergraduate research programs in China: From the perspective of self-authorship. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 3 (1), 53–73. doi:10.1163/22125868-12340030

M. Cormack (Editor) (2002). Sacrificing the self: Perspectives on martyrdom and religion (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press).

Creed, W. D., DeJordy, R., and Lok, J. (2010). Being the change:Resolving institutional contradiction through identity work. Acad. Manage. J. 53, 1336–1364. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.57318357

Crystal, L. P., and George, L. S. (2013). Assessing meaning and meaning making in the context of stressful life events: Measurement tools and approaches. J. Posit. Psychol. 8 (6), 483–504. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.830762

Dacin, M. T., Dacin, P. A., and Tracey, P. (2011). Social entrepreneurship: A critique and future directions. Organ. Sci. 22 (5), 1203–1213. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0620

Dees, J. G., Emerson, J., and Economy, P. (2001). Enterprising non- profits: A toolkit for social entrepreneurs. Wiley, NY: Enterprising non- profits: A toolkit for social entrepreneurs.

Dees, J. G., and Anderson, B. B. (2003). Sector-Bending: Blurring Lines between Nonprofit and For-Profit. Society. 40, 16–27. doi:10.1007/s12115-003-1014-z

DeRue, D. S., and Ashford, S. J. (2010). Who will lead and who will follow? A social process of leadership identity construction in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 35, 627–647. doi:10.5465/amr.2010.53503267