- 1School of Business, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 2School of Economics, Management and Law, University of South China, Hengyang, China

Increasing evidences suggest that employees exhibit positive attitudinal and behavioral responses when they attribute their company’s demonstrations of corporate social responsibility as substantive. However, there has been insufficient investigation into the underlying psychological processes through which substantive corporate social responsibility attributions are associated with work engagement. Based on the model of psychological conditions for engagement, we proposed that attributions of substantive CSR are positively related to work engagement via work meaningfulness, psychological safety, and organization-based self-esteem. We collected two-wave time-lagged questionnaire data from 503 fulltime employees in mainland China. Hierarchical regression was conducted to test hypothesized model using SPSS Process macro. Results indicated that substantive corporate social responsibility attributions positively predicted work engagement; work meaningfulness, psychological safety and organization-based self-esteem parallel mediated this relationship. The findings contribute to the literature of well-being related outcomes of corporate social responsibility attributions and help a thorough understanding of antecedents of work engagement. It expands our knowledge of the new mechanisms in the relationship between corporate social responsibility attributions and work engagement. Our findings also could shed lights on the management for employees’ work engagement.

1 Introduction

The rapid economic growth is accompanied with energy consumption and environmental problems (Ren et al., 2022c; Ren et al., 2022d). Increasing environmental problems such as global warming, ozone layer destruction, and depletion, as well as acid rain pose huge challenges to the international community and even humanity (Wang et al., 2022a; Wang et al., 2022b). Meanwhile, poverty is also a social problem that has received wide attention (Dong et al., 2021). More and more corporate stakeholders expect that companies should show corporate social responsibility (CSR) which contributes to society and the environment while achieving profitability (Farooq et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2022b). As key stakeholders, employees have the potential to support, participate in, or even lead CSR initiatives (Farooq et al., 2017).

It has been found that employees’ perception of CSR can lead employees’ positive outcomes, such as organizational commitment (Edwards and Kudret, 2017), organizational identification (Farooq et al., 2017), task performance (Edwards and Kudret, 2017), and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB, Rupp et al., 2013; Farooq et al., 2017; He et al., 2019). However, Manika et al. (2015) and Newman et al. (2015) found no correlation between CSR perception and OCB. It is possible that employees care more about the motivations behind enterprises’ CSR initiatives than the initiatives themselves (Vlachos et al., 2017). Presumably, employees will exhibit more positive attitudinal and behavioral responses if they attribute the CSR practices to motivations that are substantive (efforts to be genuine and other-serving) rather than symbolic (efforts to comply with regulations or greenwash the company’s reputation) (Donia et al., 2017; Donia et al., 2019). Prior studies explored the boundary condition played by CSR attributions in the relationship between CSR perception and employee attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (De Roeck and Delobbe, 2012; Gatignon-Turnau and Mignonac, 2015; Lee and Seo, 2017). However, as a subjective reasoning and judgment about the motives behind the enterprise’s social responsibility practices, CSR attributions have a potential to impact employees directly (Donia et al., 2017). A limited number of studies have shown a facilitative effect of employees’ attributions of substantive CSR on organizational pride (Donia et al., 2019), job satisfaction (Vlachos et al., 2013), and affective commitment (Raub, 2017), but largely ignoring its positive impact on employees’ health and well-being (Gond et al., 2017).

Indeed, being a typical and critical form of work-related well-being, work engagement refers to a positive, fulfilling, affective-motivational state (Bakker et al., 2008; Bakker, 2009). Engaged employees are more likely to be psychologically and physically healthy, they have a higher level of energy to fulfill family roles (Eldor, 2016; Knight et al., 2017). Moreover, a meta-analytic review indicated that work engagement was positively associated with task performance (Christian et al., 2011), which can provide enterprises with a competitive advantage (Eldor, 2016). The unique value of work engagement both for employees, enterprises, and families, emphasizes the importance to identify the driving factors of work engagement. Prior studies found that task characteristics (e.g., task significance, Goštautaitė and Bučiūnienė, 2015); leadership (e.g., charismatic leadership, Babcock-Roberson and Strickland, 2010), and dispositional characteristics (e.g., conscientiousness, Furnham et al., 2002) were positively related to work engagement. Scholars called for further investigation of its facilitative factors in addition to these above factors (Christian et al., 2011).

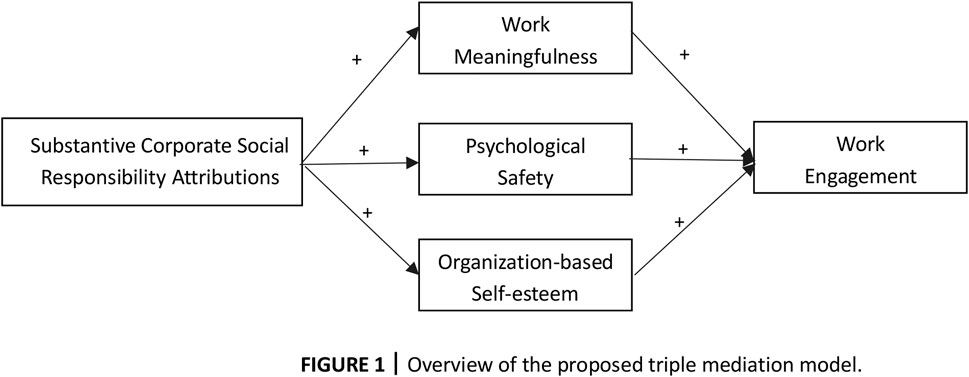

Accordingly, this study fills in these research gaps by empirically investigating whether substantive CSR attributions promote work engagement. We believe that substantive CSR attributions can satisfy employees’ various needs (Rupp et al., 2006), which encourages employees to reciprocate with greater engagement. Moreover, it should be noted that the formation of work engagement is a complex psychological process. Kahn (1990) proposed psychological conditions for engagement model (Kahn’s model) and indicated that employees could only fully experience work engagement when three psychological conditions were simultaneously presented namely psychological meaning, psychological safety, and psychological resource availability. Kahn’s model helps connect a broader work environment and work engagement (Fletcher et al., 2018). According to Kahn’s (1990) model, this study aims to further explore the parallel mediating effect played by work meaningfulness, psychological safety, and organization-based self-esteem (OBSE) in the relationship between substantive CSR attributions and work engagement. In line with previous research, work meaningfulness (Roberts and David, 2017; Lin et al., 2020) and psychological safety (Roberts and David, 2017; Lin et al., 2020) correspond to two of the three conditions for engagement in Kahn’s (1990) model. Meanwhile, our study proposes that the third antecedent of engagement, psychological resource availability, can be represented by organization-based self-esteem. Furthermore, prior studies demonstrated that employee perceptions of CSR practices as substantive (i.e., genuine and other-serving) were positively associated with increased work meaningfulness (Donia et al., 2019) and psychological safety (Ahmad et al., 2019). In addition, working for a socially responsible enterprise can raise employees’ OBSE (Hur et al., 2022). Therefore, according to Kahn’s (1990) model, we believe that employees’ substantive CSR attributions will give rise to the three psychological antecedents of engagement.

Taken together, this study proposes and tests a triple-mediation model in which attributions of substantive CSR are positively related to work engagement through the three parallel mediators of work meaningfulness, psychological safety and OBSE. This research is important for several reasons. First, by establishing a positive link between substantive CSR attributions and work engagement, this study contributes to the literature on attributions of substantive CSR in relation to employees’ well-being and health, specifically their engagement in work. Meanwhile, it also echoes the call to further investigate the driving factors of work engagement and helps a thorough understanding of antecedents of work engagement. Second, this study introduces Kahn’s (1990) model of conceptually relevant mediators of this association. It could advance our knowledge of the potential mechanisms by which substantive CSR attributions enhance work engagement. Lastly, the present study contributes to enriching our theoretical understanding of the facilitator of psychological conditions for engagement, as well as expanding the application scope of this theoretical model. Our findings also could shed lights on the management for employees’ work engagement.

2 Theoretical background and hypotheses development

2.1 The psychological conditions for engagement model

The primary tenet of Kahn’s (1990) model of psychological conditions for personal engagement at work posits that the degree to which employees engage in their work depends on three psychological conditions. The first is psychological meaningfulness, which represents employees’ belief that they receive sufficient returns on the time, energy, and efforts that they invest into their work. The second is psychological safety, which refers to employees’ perception that it is safe to fully express themselves at work. The third is psychological resource availability, which can be viewed as employees’ sense of possessing sufficient personal resources to fully invest themselves in work. Kahn (1990) further posits that there is a psychological contract between each employee and his or her work role, and the three psychological conditions reflect the logic of that contract. Employees will invest themselves into their work roles when they believe that this contract will bring desired benefits (meaningfulness) and a guarantee of protection (safety); investment also relies on the employee having the resources to fulfill this contract (Kahn, 1990).

Kahn’s (1990) model provides an integrated theoretical framework to understand the psychological mechanisms of how substantive CSR attributions are translated to work engagement. Specific to this study, we propose that work meaningfulness represents the degree of meaning stemming from employees’ work (Kahn, 1990), which could correspond to psychological meaningfulness (Roberts and David, 2017; Lin et al., 2020). Meanwhile, psychological safety refers to employees’ belief that the presentation of genuine self at work will not negatively impact on his or her status or career (Kahn, 1990), we believe that it is consistent with psychological safety (Roberts and David, 2017; Lin et al., 2020). Moreover, we propose that psychological resource availability could be represented by organization-based self-esteem (OBSE). Resources could be defined as anything that individuals perceive as being helpful to achieving their goals, psychological resources are tools that help efficiently deal with job tasks (Halbesleben and Wheeler 2008). Self-esteem is such a typical psychological resource, because self-esteem facilitates individuals to optimize the use of contextual resources, individuals with high self-esteem tend to start a challenging task and are more inclined to actively look for help to finish their task (Hardré, 2003; ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012). Rooted on self-esteem, organization-based self-esteem (OBSE) represents employees’ belief that they are important, capable, and competent individuals in their organization (Pierce and Gardner, 2004), which could be viewed as a crucial personal resource.

In addition, according to Kahn (1990), substantive CSR attributions may shape three psychological conditions, which in turn promote work engagement. These three psychological conditions are outcomes of the interaction between employees and working contexts (Kahn 1990). We rely on these three psychological conditions to develop our hypotheses. First, we will adopt the psychological meaningfulness condition to develop the hypothesis about the mediating effect of work meaningfulness. When employees attribute enterprise’s CSR actions as substantive, they could integrate the enterprise’s ethical policies and actions into their working experiences, and experience that they contribute to a greater purpose (Hulin, 2014). Therefore, they could bring their selves to work for a sense of meaningfulness (i.e., desired benefits). Second, we will employ the psychological safety condition to explain the mediating effect of psychological safety. By creating a safe and supportive working environment (Rupp and Mallory, 2015), substantive CSR attributions could allow employees to feel that they have a safe space (i.e., guarantee of protection) to present their true selves. Third, we will explain the mediating effect of OBSE with the psychological resources availability condition. Working for an enterprise that engaged in substantive CSR activities contributes to improved OBSE, which provides sufficient personal resources for employees to present their self in work.

2.2 Substantive CSR attributions and work engagement

Work engagement represents “a positive work-related state of fulfillment of mind” (Schaufeli et al., 2006, p. 702). We assert that work engagement may be a useful way for employees to reciprocate company’s substantive CSR practices. Based on the multiple need model of organizational justice, working for a company with sincere and altruistic CSR practices could satisfy employees’ instrumental, relational, and moral needs (Rupp et al., 2006). Meanwhile, according to self-determination theory, Camilleri (2021) proposed that “laudable CSR” practices might satisfy employees’ needs of relatedness, competence, and autonomy. Owing to satisfaction of various needs, employees will pay back the costs of the organizations’ substantive CSR investments through increased engagement with their work.

Hypothesis 1:. Substantive CSR attributions are positively related to work engagement.

2.3 The mediating effect of work meaningfulness

This study believes that work meaningfulness might mediate the promoting effect of substantive CSR attributions on work engagement. Work meaningfulness refers to employees’ opinions and beliefs about the importance and value stemming from their work (Rosso et al., 2010).

According to engagement theory, individuals experience meaning at work when an enterprise’s ethical policies and actions are integrated into employees’ working experience, thereby allowing them to express their concerns for the well-being of society (Rupp and Mallory, 2015). CSR may be an important source of the sense of work meaning (Bauman and Skitka, 2012). Everyone possesses an innate desire for contributing to a greater purpose (Hulin, 2014). Working for companies that practice substantive CSR, employees may perceive that they are also contributing to the greater good of society by being a positive influence on others (Lips-Wiersma and Morris, 2009), hence increasing the meaningfulness they gain from work. It has been argued that employees can derive energy, psychological resilience, sense of meaning, enthusiasm, and inspiration from their company’s substantive CSR initiatives (Rich et al., 2010). Therefore, they are more likely to experience work meaningfulness when they attribute CSR initiatives to substantive motivations.

In line with Kahn’s (1990) model, the meaning of work is a reward for work, the more meaningful the work is the more employees might believe that they will derive benefits from investing their whole selves into their work (Kahn, 1990; Lin et al., 2020). Meanwhile, work meaningfulness is also a critical aspect of intrinsic motivation of work (Bailey et al., 2019), work meaningfulness fosters employees’ dedication to work and enthusiasm about work (Aryee et al., 2012). By contrast, when employees feel their job is not meaningful, they might conclude that investing their personal selves in the job will not be reciprocated by the organization (Kahn, 1990; Lin et al., 2020). Consequently, they are less likely to be engaged with their work. Supporting this, prior studies have found that work meaningfulness positively predicted work engagement (Lips-Wiersma and Morris, 2009; Bauman and Skitka, 2012).

Taken together, we argue that work meaningfulness mediates the positive effect of substantive CSR attributions on work engagement. In line with Kahn’s (1990) model, work elements such as CSR are associated with meaningfulness. Substantive CSR attributions could make employees feel that they are valued and important to society. It will lead to an increased sense of meaningfulness, which in turn encourages employees to engage more in their work. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2–1:. Substantive CSR attributions are positively related to work meaningfulness.

Hypothesis 2–2:. Substantive CSR attributions are positively related to work engagement through increased work meaningfulness.

2.4 The mediating effect of psychological safety

We next argue that psychological safety also mediates the positive influence of substantive CSR attributions on work engagement. Psychological safety refers to employees’ belief that the presentations of genuine self at work will not negatively impact on his or her status or career (Kahn, 1990).

It has been argued that enterprises’ internal or external practices help shape employees’ perception of work safety (Camilleri, 2021). Specific to this study, we assume that enterprises’ substantive CSR practices contribute to creating a predictable, consistent, and unambiguous work context, which helps foster psychological safety. CSR attributions provide important information for employees to evaluate the character or nature of their organization (Donia et al., 2019), as well as the work environment. When employees attribute CSR activities as substantive and worthwhile motivations, they could believe that their organizations will continue to invest in those CSR programs in the future. Stable and sustained CSR practices allow employees to more accurately predict their organizations’ behavior, and further increase their certainty about the nature of their own relationship with their organizations (Rupp, 2011). In addition, when employees perceive that organizations treat external stakeholders in a fair, moral, and sincere manner, they believe that as internal stakeholders, they will also receive the same treatment and respect (Kim et al., 2021). Prior research suggested that CSR practices that were viewed as genuine and other serving were positively related to psychological safety (Ahmad et al., 2019). In summary, substantive CSR attributions lead employees to view their work environment as predictable, consistent, and clear. In this context, they may feel reassured that displaying their true selves at work will not bring any negative consequences (May et al., 2004). Collectively, substantive CSR attributions are positively related to psychological safety.

Kahn’s (1990) model proposes that psychological safety could increase work engagement. Specifically, when employees experience psychological safety, they are more willing to invest themselves in work without fearing negative consequences (May et al., 2004). High psychological safety motivates employees to internalize their work roles into self-concepts, and to express their self-concepts through work (Brown and Leigh, 1996). As consequence, they will actively invest their efforts and energies in work (Amabile, 1983). In contrast, employees with low psychological safety will be less likely to invest themselves in work, because they might worry about the potential social risks resulting from unfiltered self-expression (Kahn, 1990; May et al., 2004). They may even exhibit withdrawal and self-defense behaviors, which could be viewed as a manifestation of low engagement (Kahn, 1990; Lin et al., 2020). Furthermore, a meta-analysis revealed a significant positive association between psychological safety and work engagement (Frazier et al., 2017). Accordingly, it is reasonable to expect that psychological safety is positively associated with work engagement.

We argue that attributions of substantive CSR are positively related to psychological safety, which in turn promotes work engagement. Based on Kahn’s (1990) model, a safe, predictable, and consistent social environment facilitates engagement by fostering a sense of psychological safety. In line with this model, substantive CSR attributions help employees believe that their work environment is safe, predictable, and consistent, which makes them feel that they are safe to engage their whole selves in work. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3–1:. Substantive CSR attributions are positively related to psychological safety.

Hypothesis 3–2:. Substantive CSR attributions are positively related to work engagement through increased psychological safety.

2.5 The mediating effect of organization-based self-esteem

We propose that attributions of substantive CSR could foster employees’ OBSE. Employees’ moral experiences in work context play an important role in the creation of self-esteem (Collier and Esteban, 2007). Companies may shape a responsible and caring corporate image by practicing CSR in a genuine manner for the well-being of society (Yan et al., 2021). Employees will incorporate this positive corporate reputation into their self-concept, thus maintaining and enhancing positive views about themselves (Paruzel et al., 2020). By comparing the organization to which they belong with other organizations, employees will experience a sense of pride and value as a member of moral organization, which helps to enhanced OBSE (Lin et al., 2012). Moreover, substantive CSR attributions could shape a relationship based on trust between employees and enterprises, employees would perceive being trusted and valued by their enterprises (De los Salmones et al., 2005), which is also beneficial to shape OBSE. Although there was no direct evidence for the positive relationship between substantive CSR attributions and OBSE, prior studies found that CSR was positively related to team self-esteem (Lin et al., 2012) or collective self-esteem (Gao et al., 2018).

According to Kahn’s (1990) model, being a form of personal resources, OBSE contributes to an employee’s positive experience at work, especially work engagement (Pierce et al., 1989; Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). From the resource perspective, employees with high self-esteem will be more confident that they have sufficient psychological resources to invest themselves in their work (Kahn, 1990; May et al., 2004). A high level of mental resources can be seen as individuals’ positive evaluation of their own ability to complete their work (Gao et al., 2018). Employees with high OBSE are more likely to possess feelings of self-efficacy, competence, and confidence that they can complete all of their work tasks successfully (Pierce et al., 1989). As a subjective evaluation of one’s competence, OBSE provides psychological resources for employees to be more engaged with their work (Gao et al., 2018). In contrast, employees with low OBSE may perceive that they do not have sufficient psychological resources to satisfy their work demands and obligations, leading to work withdrawal behavior (Kahn, 1990; May et al., 2004). Employees’ perception that they do not have sufficient psychological resources to do their job could lead to decreased engagement. Prior research found a positive association between collective self-esteem and work engagement (Gao et al., 2018), providing indirect support for our argument that OBSE could positively predict work engagement.

In summary, we assert that OBSE mediates the positive impact of substantive CSR attributions on work engagement. OBSE is a core resource that represents a response to the interaction between person and environment and plays an important role in influencing one’s attitude and behavior in the workplace (Hobfoll and Freedy, 1993; Wang et al., 2020). According to Kahn’s (1990) model, attributions of substantive CSR communicate to the employee that they are important, valuable, and competent members of organizations, which in turn enhances their OBSE. Subsequently, increased OBSE provides sufficient psychological resources for employees to invest themselves in work. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 4–1:. Substantive CSR attributions are positively related to organization-based self-esteem.

Hypothesis 4–2:. Substantive CSR attributions are positively related to work engagement through increased organization-based self-esteem.Taken together, the proposed theoretical model was shown in Figure 1.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Participants and procedure

To minimize common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003), data were collected at two time points, 2 months apart, with different questionnaires at each point. Moreover, our questionnaires used different anchor point number and response format which also could restrict CMV by lessening anchoring effects. Additionally, the use of reverse-coded items in questionnaires could diminish response pattern biases, which is a useful tool to constrain CMV.

Participants were full-time employees from central and southern mainland China. They worked in various industries, including finance, manufacturing, mining and smelting, pharmaceuticals, real estate and logistics. With the permission of top management, the employees who volunteered completed the anonymous questionnaires as a group in a conference room at work. Coordinators in each company assigned a unique ID number to each participant to match the questionnaires before the first distribution of questionnaires. Once a participant was finished, they gave the completed questionnaires directly to the researchers. Participants received monetary compensation of about 10 Chinese yuan at each time point.

At the first time point, 936 employees were invited to report their demographic information, their rating of substantive CSR attributions, work meaningfulness, psychological safety, and OBSE. We received 705 valid responses (a valid response rate of 75.32%). Two months later, we distributed questionnaires concerning work engagement to employees who provided valid responses in the first survey. 503 employees returned valid questionnaires resulting in a valid response rate of 71.35%. Among the final sample consisting of 503 participants, 41.90% were female, 58.10% were male; 62.90% held a bachelor’s degree or above; and 93.60% were at or below the junior management level. The average age of participants was 35.137 years (SD = 8.180).

3.2 Measures

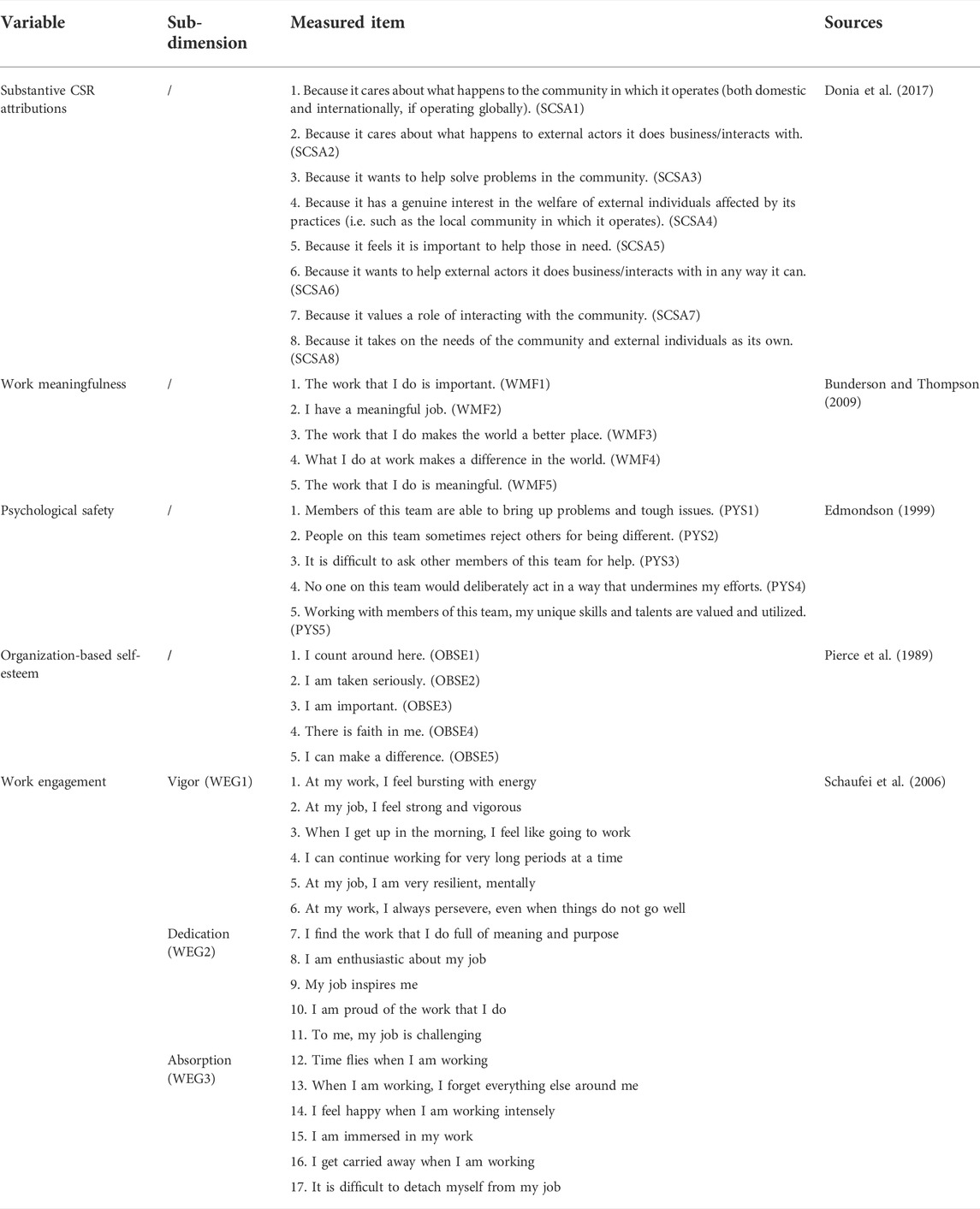

As all focal variables were measured using scales originally developed in English (Detailed information of used scales would be seen in Table 1), we translated the scales into Chinese by following translation/back translation procedures (Brislin, 1986). To be specific, two PHD students in Human Resource Management independently translated and cross-referenced to generate the first draft of scales’ Chinese version. Then, one PH. D student who had studied in United Kingdom was invited to translate them back. The authors and three translators have compared the translated English version with the original version and modified the Chinese version of scales to ensure the conceptual equivalence. Finally, three MBA students revised the Chinese version and generated the final version of questionnaire.

3.2.1 Substantive CSR attributions

In line with Donia et al. (2019), substantive CSR attributions were assessed with the subscale of substantive CSR from Substantive and Symbolic Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR-SS) scale (Donia et al., 2017). This subscale consisted of eight items, and asked employee to indicate the degree to which each of the following statement explains the true motives of their organization to engage in socially responsibility activities, such as environment protection, and participation in local community affairs. This measure used a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s α of this sub-scale was. 0.854.

3.2.2 Work meaningfulness

We used the five-item scale developed by Bunderson and Thompson (2009). This measure used a seven-point Likert scale, which is ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.863.

3.2.3 Psychological safety

The current study assessed psychological safety with Edmondson (1999)’s scale. We selected the five items with the highest factor loadings. This measure used a five-point Likert scale (1 being strongly disagree, and 5 being strongly agree) and Cronbach’s α was 0.773.

3.2.4 Organization-based self-esteem

We employed five items with the highest factor loadings from Pierce et al. (1989)’s scale to measure OBSE. This scale asked respondents to recall the information they received from leader’s behavior or attitude, and then rated how much they agree or disagree with following statements. This measure used a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) and Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.807.

3.2.5 Work engagement

The shortened version of Schaufeli et al.'s (2006) scale includes 17 items to assess three sub-dimensions of work engagement. Participants were asked to indicate how often they feel about their work in certain ways in the past 2 months. If they never had this feeling, marked “0”; if they had this feeling, marked the number (ranging from 1 to 6) that most accurately reflects the frequency. Six items measure the sub-dimension of vigor (α = 0.912). Five items assess the sub-dimension of dedication (α = 0.923). Six items measure the sub-dimension of absorption (α = 0.890). Cronbach’s α in the current study was 0.966. Cronbach’s α for whole scale was 0.966.

3.2.6 Control Variables

Previous studies found that age, gender, position at work, and education level influenced work engagement (Schaufeli et al., 2006; Halbesleben and Wheeler, 2008). Accordingly, we controlled for these variables to alleviate potential confounding effects of demographic variables. Gender was coded as 0 (female), and 1 (male). Age was measured in years. Position was coded as 1 (non-managerial position), 2 (junior management level), or 3 (middle management level). Education level was coded as 1 (high school degree or below), 2 (junior college/associate degree), 3 (bachelor’s degree), or 4 (master’s degree or above).

4 Results

4.1 Validity

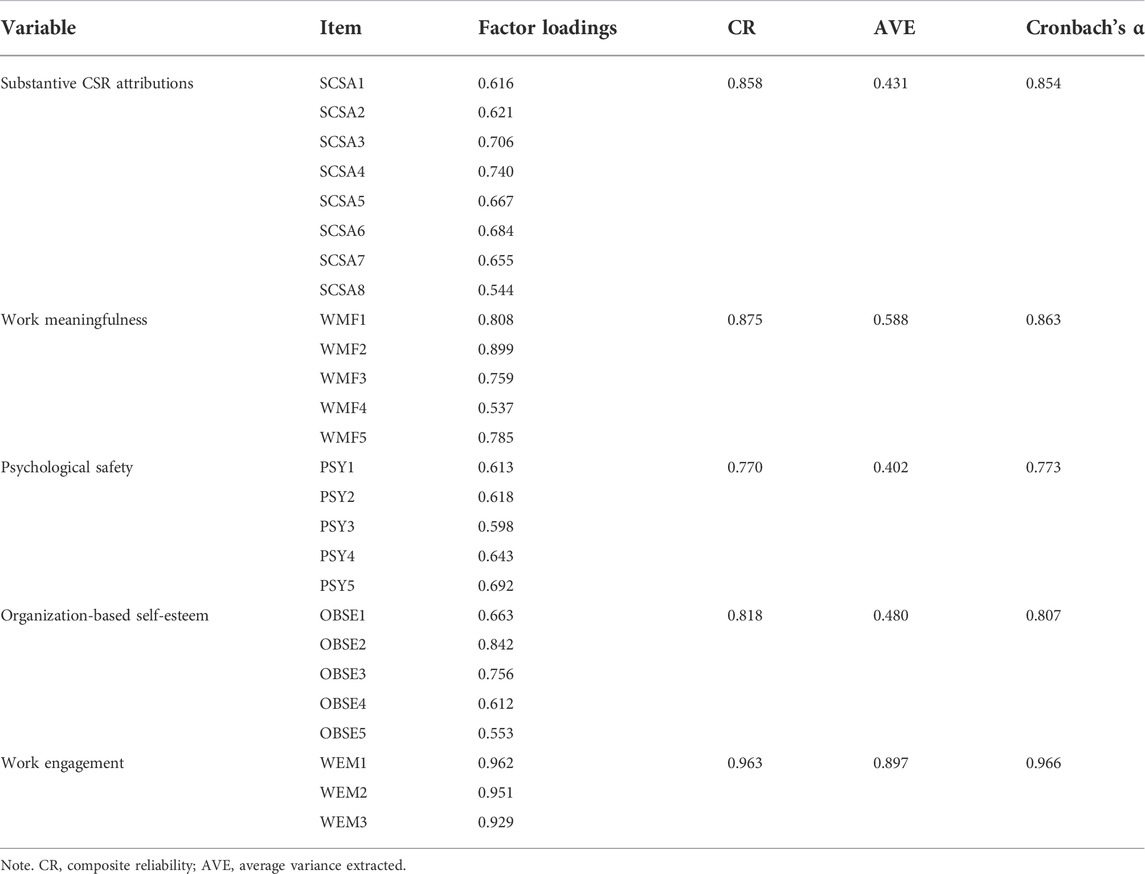

Using AMOS 24.0, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine the appropriateness of our measurement model. Because scales consisting of many items may decrease the ratio of sample size to the number of estimated parameters, and may lead to variables being over-identified (Little et al., 2002), we combined items from each of the subscale of work engagement scale into parcels. Item parceling improves the ratio of participants to parameters modeled (Little et al., 2002). Compared to using individual items, item parceling is thought to be more reliable because it could reveal a larger proportion of true-score variance (Little et al., 2013). The three parcels were made up of the items from the dedication, vigor, and absorption subscales of the work engagement measure. Specifically, we aggregated the items of each subscale by using the mean scores as a single indicator, and then set these indicators to load onto a second order factor representing work engagement.

As shown in Table 2, the five-factor model fitted the data well (χ2 = 783.911, df = 289, CFI = 0.927, TLI = 0.918, RMSEA = 0.058). This model provided a significantly better fit than all other alternative models. Moreover, we calculated the value of standard factor loadings, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) to further examine convergent validity. The values of factor loadings higher than 0.50, CR greater than 0.60 and AVE exceeding 0.50 could establish convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Results from Table 3 showed that all items’ standard factor loadings were ranging from 0.537 to 0.962, which higher than 0.50; the value of focal variable’s CR were ranging from 0.770 to 0.963, which exceeding 0.60. We found that several construct’s AVE were in the range of 0.402–0.480, which not reaching 0.50. However, it has been suggested that the cutoff point of 0.50 for AVE was too strict, and convergent reliability could be established by CR alone (Malhotra, 2010). Meanwhile, Fornell and Larcker (1981) also posited that when CR value exceeding 0.60, the AVE value of corresponding construct being in the range of 0.40–0.50 was acceptable. Accordingly, the CR value of all focal constructs were greater than 0.700. Taken together, the convergent validity of constructs was acceptable. Furthermore, we found the square roots of the AVE of focal constructs were in the range of 0.634–0.947, which were greater than corresponding inter-construct correlations. Hence, in line with Fornell and Larcker (1981)’s criterion, we believe that the discriminant validity of focal constructs was satisfactory. Moreover, the ratio of HTMT (Heterotrai-monotrait) between focal variables were in the range of 0.369–0.655, which were less than the cutoff 0.85 suggested by Henseler et al. (2015) and providing further support for the establishment of discriminant validity.

4.2 Common method variance

Although we collected different questionnaire data at the two time-points, all variables were assessed by employees’ self-reports. This raised the concern of common method variance (CMV). Accordingly, we conducted an unmeasured latent method construct (ULMC) analysis to detect CMV (as shown in Table 2). The difference in CFI (ΔCFI = 0.039) and NFI (ΔNFI = 0.041) between models with and without an unmeasured latent method factor was less than 0.05. These values were below the criterion that prior research has proposed to represent a substantial difference between models (Bagozzi and Yi, 1990; Gong et al., 2022), indicating that there was no significant difference between the fit indices of two models. Moreover, the method factor accounted for 22.98% of the total variance, which is lower than the 25% threshold value suggested in prior research (Williams et al., 1989). Taken together, these results indicated that CMV may not cause serious bias in our results.

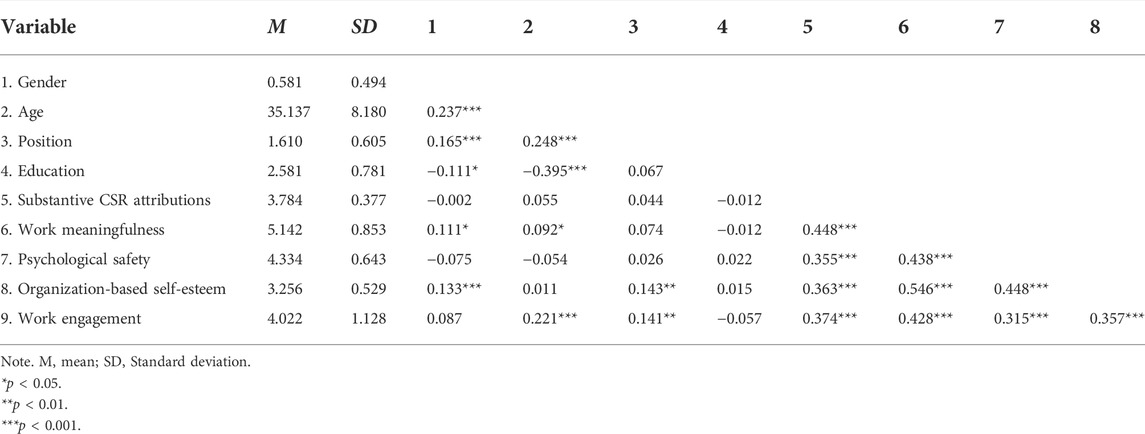

4.3 Descriptive statistics

The means, standard deviations, and correlations of the studied variable are shown in Table 4. The correlation results of our focal variables provided initial supports for our hypotheses. More detailed information could be seen in Table 4.

4.4 Hypotheses testing

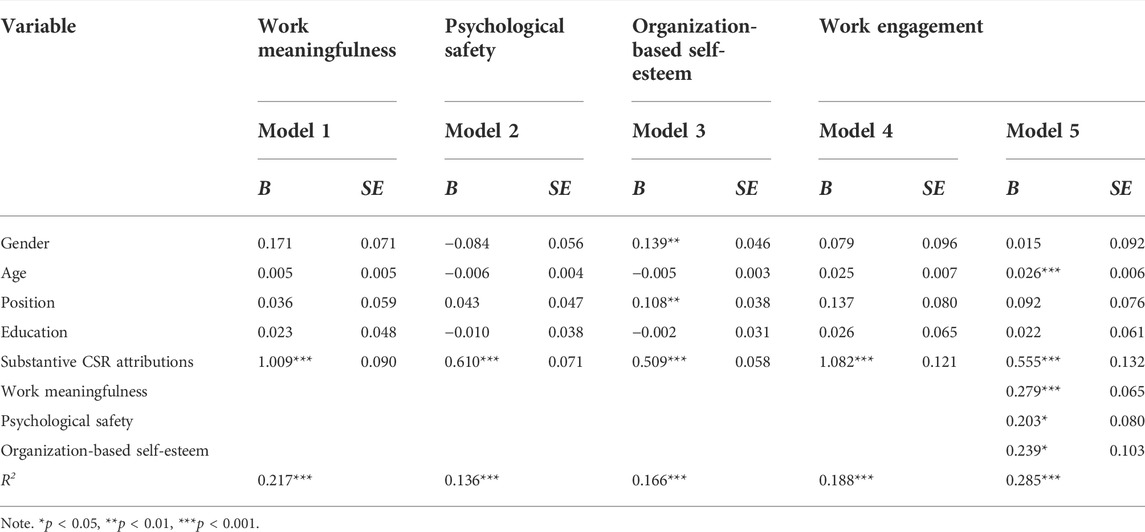

We used SPSS 26.0 to test all hypotheses. Meanwhile, to test our mediation hypotheses, we used bootstrap analysis conducted with the PROCESS macro developed by Hayes (2012) in SPSS 26.0. Hypothesis 1 proposed that substantive CSR attributions positively predicted work engagement. As presented in Table 5, when controlling for gender, age, education and position, substantive CSR attributions positively predicted work engagement (Model 4 in Table 5: B = 1.082, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1.

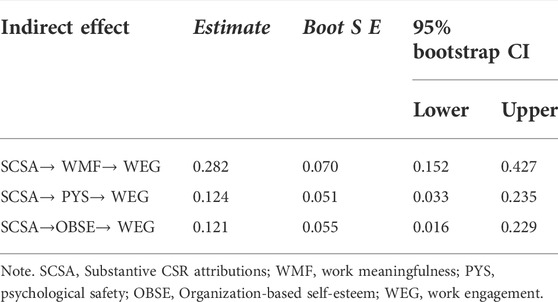

Hypothesis 2 proposed that work meaningfulness mediated the positive effect of substantive CSR attributions on work engagement. Results showed there was a positive relationship between substantive CSR attributions and work meaningfulness (Model 1 in Table 5: B = 1.009, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2–1. Meanwhile, Model 5 showed a positive link between work meaningfulness and work engagement (Model 5 in Table 5: B = 0.279, p < 0.001). Moreover, Hypothesis 2–2 was also supported, because bootstrapping results shown in Table 6 indicated that substantive CSR attributions had a significant positive indirect effect on work engagement via increased work meaningfulness (Table 6: indirect effect = 0.282, Bootstrap SE = 0.070, 95% CI [0.152, 0.427]). Taken together, the results provided full support for Hypothesis about the mediating effect of work meaningfulness in the relationship between substantive CSR attributions and work engagement.

Hypothesis 3 proposed the mediating effect played by psychological safety in the relationship between substantive CSR attributions and work engagement. Hypothesis 3-1 was supported because substantive CSR attributions positively predicted psychological safety (Model 2 in Table 5: B = 0.610, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 3-2 was also supported, psychological safety was positively associated with work engagement (Model 5 in Table 5: B = 0.203, p < 0.05), and the bootstrapping results shown in Table 6 confirmed that substantive CSR attributions had a significant positive indirect influence on engagement through increased psychological safety (indirect effect = 0.124, Bootstrap SE = 0.051, 95% CI [0.033, 0.235]).

Hypothesis 4 was that substantive CSR attributions would be positively associated with work engagement via OBSE. As shown in Table 5, substantive CSR attributions were positively related to OBSE (Model 3 in Table 5: B = 0.509, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 4–1. In addition, OBSE was positively connected with work engagement (Model 5 in Table 5: B = 0.239, p < 0.05), and substantive CSR attributions significantly indirectly promoted work engagement through OBSE (Table 6: indirect effect = 0.121, Bootstrap SE = 0.055, 95% CI [0.016, 0.229]), which supported Hypothesis 4–2. Overall, Hypothesis 4 was fully supported by these results.

5 Discussion

5.1 Theoretical contributions

The theoretical contributions of this study are three-folds. First, the present study reveals that substantive CSR attributions positively predict employees’ work engagement which enriches the research of CSR attributions. Prior studies mainly identified employees’ CSR attributions as a boundary condition of the impact of CSR on employees (De Roeck and Delobbe, 2012; Gatignon-Turnau and Mignonac, 2015; Lee and Seo, 2017), explorating the inducing role of CSR attributions on employees remains insufficiently (Gond et al., 2017). Although some scholars have preliminarily investigated the facilitative effect of substantive CSR attributions on employees’ organizational pride (Donia et al., 2017), affective commitment (Raub, 2017), as well as job satisfaction (Vlachos et al., 2013) which were criterion variables (Chaudhary, 2017), little was known about the relationship between substantive CSR attributions and employee’s health-related constructs. Work engagement is a specific measurement indicator of psychological health (Timms et al., 2015), and also provides enterprises with a unique competitive advantage (Eldor, 2016). Our findings help confirm that CSR attributions are beneficial to create win-win situations for the well-being of employees and enterprises.

Second, based on Kahn’s (1990) model, this study demonstrates the parallel mediating roles of work meaningfulness, psychological safety, and OBSE in the association between substantive CSR attributions and work engagement. Previous studies explored the direct relationship between CSR attributions and work engagement, but few have investigated the psychological mechanisms underlying this relationship (Chaudhary and Akhouri, 2018). Our study shows that the formation of work engagement is a complex psychological process wherein three psychological conditions (i.e., meaning, safety, and availability) collectively determine the extent to which employees are engaged in their work (Kahn, 1990). As a result, our findings help build a more holistic and accurate framework of the psychological mechanisms through which CSR attributions can promote employees’ work engagement.

Third, by introducing Kahn’s (1990) model into CSR attributions research, this study expands our knowledge about the antecedents of work engagement. Prior studies mainly found that job characteristics (e.g., task significance, Goštautaitė and Bučiūnienė, 2015); leadership (e.g., charismatic leadership, Babcock-Roberson and Strickland, 2010), and dispositional characteristics (e.g., conscientiousness, Furnham et al., 2002) were positively related to work engagement. Scholars called for further investigate the other potential promoting factors (Christian et al., 2011). In addition to these studies, this study now evidences that work engagement can be predicted by employees’ perceptions that their company’s CSR initiatives are motivated by genuine, altruistic concerns. Our study also helps expand the potential application of Kahn’s (1990) model.

5.2 Managerial implications

The results have several potential practical implications. First, enterprises may benefit from ensuring that employees are convinced of the genuine and sincere motivations behind the CSR initiatives. Organizations could encourage employees to participate in CSR activities in order to increase their understanding and awareness of why the enterprise engage in these CSR practices. In addition, organizations should provide timely and necessary information about their CSR practices to employees, which can help them to perceive those initiatives as substantive (Donia and Sirsly, 2016).

Second, organizations are encouraged to take measures to promote these three crucial antecedents of engagement. To be specific, the perceived meaningfulness of work can be enhanced through such practices as arranging diverse work, giving employees more authority and discretion, and providing timely performance feedback (De Roeck and Maon, 2018). To foster psychological safety, organizations may benefit from relational job design (Grant, 2007) and the construction of relational high-performance working system (Gittell and Douglass, 2012). Organizations could promote OBSE through high job complexity and autonomy design (Lapointe et al., 2011).

5.3 Limitations and future research directions

The present study also has several limitations. First, the present study employed a two-wave time-lagged design, which has certain advantages in mitigating common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, we cannot identify the causal directions in our proposed theoretical model. Future studies could apply longitudinal or experimental design to validate the causal directions of interest.

Second, we did not examine any boundary conditions on the effect of substantive CSR attributions on work engagement. CSR attributions have been presented not to have the same effect on all employees (Donia and Sirsly, 2016). Employees with higher moral identity were shown in one study to be more sensitive to the moral cues in the workplace and more responsive to moral issues (Aquino and Reed, 2002). In line with this logic, moral identity motivates employees to feel more appreciative of substantive CSR initiatives (Donia and Sirsly, 2016). As such, we suggest that future studies investigate the boundary condition played by moral identity on the relationships explored in this study.

Third, we conducted this study in only one cultural context of high collectivist orientation which differs from the cultural setting with high individualism orientation (Hofstede, 1993). Therefore, multi-cultural investigations are recommended to examine whether the beneficial effect of substantive CSR attributions on work engagement can be generalized to another cultural context. Moreover, our respondents were limited in five industries which might also constrain the generalizability of findings, and we encourage future research to address this concern by expanding the diversity of industry.

6 Conclusion

In recent years, to address environmental and social issues, increasing enterprises have engaged in CSR activities (Dong et al., 2021; Ren et al., 2022a). As internal stakeholders, Employees are more likely to respond positively to substantive CSR practices (Donia et al., 2019). Several studies found that substantive CSR attributions could motivate positive working perception and attitude (Vlachos et al., 2013; Raub, 2017; Donia et al., 2019), however, little was known about the association between substantive CSR attributions and employees’ well-being. Drawing upon Kahn’s model of psychological conditions for engagement at work, the present study demonstrated a potential positive influence of employees’ attributions of substantive CSR on work engagement. In addition, this positive effect was mediated by three parallel mediators, namely work meaningfulness, psychological safety, and OBSE. These findings extend the current knowledge of the effect of employees’ substantive CSR attributions on their well-being and provide an integrative framework for understanding the psychological mechanisms that shape individual positive reactions to CSR practices. The results have significant practical implications for organizations and managers in enhancing employees’ work engagement.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HG and XH contributed to conception and design of the study. AY and XH collected the data. XH performed statistical analysis. HG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AY and XH contributed to manuscript revision and read the submitted version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work is supported by the Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72172160, 71972185), the Project of the Social Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 20YBA255), and the “High-End Think Tank” Project of Central South University (Grant No. 2020ZNZK04).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers, Aaron McCune Stein, and Ying Li for their constructive comments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad, I., Donia, M. B., and Shahzad, K. (2019). Impact of corporate social responsibility attributions on employees’ creative performance: The mediating role of psychological safety. Ethics Behav. 29 (6), 490–509. doi:10.1080/10508422.2018.1501566

Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 45 (2), 357–376. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.357

Aquino, K., and Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83 (6), 1423–1440. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.83.6.1423

Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F. O., Zhou, Q., and Hartnell, C. A. (2012). Transformational leadership, innovative behavior, and task performance: Test of mediation and moderation processes. Hum. Perform. 25 (1), 1–25. doi:10.1080/08959285.2011.631648

Babcock-Roberson, M. E., and Strickland, O. J. (2010). The relationship between charismatic leadership, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Psychol. 144 (3), 313–326. doi:10.1080/00223981003648336

Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y. (1990). Assessing method variance in multitrait-multimethod matrices: The case of self-reported affect and perceptions at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 75 (5), 547–560. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.75.5.547

Bailey, C., Yeoman, R., Madden, A., Thompson, M., and Kerridge, G. (2019). A review of the empirical literature on meaningful work: Progress and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 18 (1), 83–113. doi:10.1177/1534484318804653

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., and Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 22 (3), 187–200. doi:10.1080/02678370802393649

Bakker, A. (2009). “Building engagement in the workplace,” in The peak performing organization. Editors J. Burke, and C. L. Cooper (Oxon, UK: Routledge), 50–72.

Bauman, C. W., and Skitka, L. J. (2012). Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Res. Organ. Behav. 32, 63–86. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2012.11.002

Brislin, R. W. (1986). “The wording and translation of research instruments,” in Cross-cultural research and methology series. Editors W. J. Lonner, and J. W. Berry (New York, NY: Sage Publications), 137–164.

Brown, S. P., and Leigh, T. W. (1996). A new look at psychological climate and its relationship to job involvement, effort, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 81 (4), 358–368. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.358

Bunderson, J. S., and Thompson, J. A. (2009). The call of the wild: Zookeepers, callings, and the double-edged sword of deeply meaningful work. Adm. Sci. Q. 54 (1), 32–57. doi:10.2189/asqu.2009.54.1.32

Camilleri, M. A. (2021). The employees’ state of mind during COVID-19: A self-determination theory perspective. Sustainability 13 (7), 3634. doi:10.3390/su13073634

Chaudhary, R., and Akhouri, A. (2018). Linking corporate social responsibility attributions and creativity: Modeling work engagement as a mediator. J. Clean. Prod. 190, 809–821. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.187

Chaudhary, R. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Can CSR help in redressing the engagement gap? Soc. Responsib. J. 13 (2), 323–338. doi:10.1108/SRJ-07-2016-0115

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., and Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 64 (1), 89–136. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

Collier, J., and Esteban, R. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Bus. Ethics. 16 (1), 19–33. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8608.2006.00466.x

De los Salmones, M. D. M. G., Crespo, A. H., and del Bosque, I. R. (2005). Influence of corporate social responsibility on loyalty and valuation of services. J. Bus. Ethics 61, 369–385. doi:10.1007/s10551-005-5841-2

De Roeck, K., and Delobbe, N. (2012). Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. J. Bus. Ethics 110 (4), 397–412. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1489-x

De Roeck, K., and Maon, F. (2018). Building the theoretical puzzle of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: An integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 149 (3), 609–625. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3081-2

Dong, K., Ren, X., and Zhao, J. (2021). How does low-carbon energy transition alleviate energy poverty in China? A nonparametric panel causality analysis. Energy Econ. 103, 105620. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105620

Donia, M. B., Ronen, S., Tetrault Sirsly, C.-A., and Bonaccio, S. (2019). CSR by any other name? The differential impact of substantive and symbolic CSR attributions on employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 157 (2), 503–523. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3673-5

Donia, M. B., and Sirsly, C.-A. T. (2016). Determinants and consequences of employee attributions of corporate social responsibility as substantive or symbolic. Eur. Manag. J. 34 (3), 232–242. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2016.02.004

Donia, M. B., Tetrault Sirsly, C. A., and Ronen, S. (2017). Employee attributions of corporate social responsibility as substantive or symbolic: Validation of a measure. Appl. Psychol. 66 (1), 103–142. doi:10.1111/apps.12081

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 44 (2), 350–383. doi:10.2307/2666999

Edwards, M. R., and Kudret, S. (2017). Multi-foci CSR perceptions, procedural justice and in-role employee performance: The mediating role of commitment and pride. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 27 (1), 169–188. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12140

Eldor, L. (2016). Work engagement: Toward a general theoretical enriching model. Hum. Resour. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 15 (3), 317–339. doi:10.1177/1534484316655666

Farooq, O., Rupp, D. E., and Farooq, M. (2017). The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manage. J. 60 (3), 954–985. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0849

Fletcher, L., Bailey, C., and Gilman, M. W. (2018). Fluctuating levels of personal role engagement within the working day: A multilevel study. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 28 (1), 128–147. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12168

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104

Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., and Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Pers. Psychol. 70 (1), 113–165. doi:10.1111/peps.12183

Furnham, A., Petrides, K., Jackson, C., and Cotter, T. (2002). Do personality factors predict job satisfaction? Pers. Individ. Dif. 33, 1325–1342. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00016-8

Gao, Y., Zhang, D., and Huo, Y. (2018). Corporate social responsibility and work engagement: Testing a moderated mediation model. J. Bus. Psychol. 33 (5), 661–673. doi:10.1007/s10869-017-9517-6

Gatignon-Turnau, A. L., and Mignonac, K. (2015). Mis)Using employee volunteering for public relations: Implications for corporate volunteers’ organizational commitment. J. Bus. Res. 68 (1), 7–18. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.05.013

Gittell, J. H., and Douglass, A. (2012). Relational bureaucracy: Structuring reciprocal relationships into roles. Acad. Manage. Rev. 37 (4), 709–733. doi:10.5465/amr.2010.0438

Gond, J. P., El Akremi, A., Swaen, V., and Babu, N. (2017). The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 38 (2), 225–246. doi:10.1002/job.2170

Gong, Y., Li, J., Xie, J., Zhang, L., and Lou, Q. (2022). Will “green” parents have “green” children? The relationship between parents’ and early adolescents’ green consumption values. J. Bus. Ethics 179 (2), 369–385. doi:10.1007/s10551-021-04835-y

Goštautaitė, B., and Bučiūnienė, I. (2015). Work engagement during life-span: The role of interaction outside the organization and task significance. J. Vocat. Behav. 89, 109–119. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2015.05.001

Grant, A. M. (2007). Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Acad. Manage. Rev. 32 (2), 393–417. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.24351328

Halbesleben, J. R., and Wheeler, A. R. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work Stress 22 (3), 242–256. doi:10.1080/02678370802383962

Hardré, P. L. (2003). Beyond two decades of motivation: A review of the research and practice in instructional design and human performance technology. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2, 54–81. doi:10.1177/1534484303251661

Hayes, A. F. (2012). Process: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper].

He, J., Zhang, H., and Morrison, A. M. (2019). The impacts of corporate social responsibility on organization citizenship behavior and task performance in hospitality: A sequential mediation model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 31 (6), 2582–2598. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-05-2018-0378

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43 (1), 115–135. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hobfoll, S. E., and Freedy, J. (1993). “Conservation of resources: A general stress theory applied to burnout,” in Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research. Editors W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, and T. Marek (London, UK: Taylor & Francis), 115–129.

Hofstede, G. (1993). Cultural constraints in management theories. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 7 (1), 81–94. doi:10.5465/ame.1993.9409142061

Hulin, C. L. (2014). “Work and being: The meanings of work in contemporary society,” in The nature of work: Advances in psychological theory, methods, and practice. Editors J. K. Ford, J. R. Hollenbeck, and A. M. Ryan (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 9–33.

Hur, W. -M., Rhee, S. Y., Lee, E. J., and Park, H. (2022). Corporate social responsibility perceptions and sustainable safety behaviors among frontline employees: The mediating roles of organization-based self-esteem and work engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 29 (1), 60–70. doi:10.1002/csr.2173

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manage. J. 33 (4), 692–724. doi:10.5465/256287

Kim, B.-J., Kim, M.-J., and Kim, T.-H. (2021). The power of ethical leadership”: The influence of corporate social responsibility on creativity, the mediating function of psychological safety, and the moderating role of ethical leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (6), 2968. doi:10.3390/ijerph18062968

Knight, C., Patterson, M., and Dawson, J. (2017). Building work engagement: A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of work engagement interventions. J. Organ. Behav. 38 (6), 792–812. doi:10.1002/job.2167

Lapointe, É., Vandenberghe, C., and Panaccio, A. (2011). Organizational commitment, organization-based self-esteem, emotional exhaustion and turnover: A conservation of resources perspective. Hum. Relat. 64 (12), 1609–1631. doi:10.1177/0018726711424229

Lee, S. Y., and Seo, Y. W. (2017). Corporate social responsibility motive attribution by service employees in the parcel logistics industry as a moderator between CSR perception and organizational effectiveness. Sustainability 9 (3), 355. doi:10.3390/su9030355

Lin, C. P., Baruch, Y., and Shih, W. C. (2012). Corporate social responsibility and team performance: The mediating role of team efficacy and team self-esteem. J. Bus. Ethics 108 (2), 167–180. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-1068-6

Lin, W., Koopmann, J., and Wang, M. (2020). How does workplace helping behavior step up or slack off? Integrating enrichment-based and depletion-based perspectives. J. Manag. 46 (3), 385–413. doi:10.1177/0149206318795275

Lips-Wiersma, M., and Morris, L. (2009). Discriminating between ‘meaningful work’ and the ‘management of meaning. J. Bus. Ethics 88 (3), 491–511. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0118-9

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., and Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 9 (2), 151–173. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K., and Schoemann, A. M. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychol. Methods 18 (3), 285–300. doi:10.1037/a0033266

Malhotra, N. K. (2010). Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Publishing.

Manika, D., Wells, V. K., Gregory-Smith, D., and Gentry, M. (2015). The impact of individual attitudinal and organisational variables on workplace environmentally friendly behaviours. J. Bus. Ethics 126 (4), 663–684. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1978-6

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., and Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 77 (1), 11–37. doi:10.1348/096317904322915892

Newman, A., Nielsen, I., and Miao, Q. (2015). The impact of employee perceptions of organizational corporate social responsibility practices on job performance and organizational citizenship behavior: Evidence from the Chinese private sector. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 26 (9), 1226–1242. doi:10.1080/09585192.2014.934892

Paruzel, A., Danel, M., and Maier, G. W. (2020). Scrutinizing social identity theory in corporate social responsibility: An experimental investigation. Front. Psychol. 11, 580620. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.580620

Pierce, J. L., Gardner, D. G., Cummings, L. L., and Dunham, R. B. (1989). Organization-based self-esteem: Construct definition, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manage. J. 32 (3), 622–648. doi:10.2307/256437

Pierce, J. L., and Gardner, D. G. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. J. Manag. 30 (5), 591–622. doi:10.1016/j.jm.2003.10.001

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5), 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Raub, S. (2017). When employees walk the company talk: The importance of employee involvement in corporate philanthropy. Hum. Resour. Manage. 56 (5), 837–850. doi:10.1002/hrm.21806

Ren, X., Duan, K., Tao, L., Shi, Y., and Yan, C. (2022a). Carbon prices forecasting in quantiles. Energy Econ. 108, 105862. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105862

Ren, X., Li, Y., Qi, Y., and Duan, K. (2022c). Asymmetric effects of decomposed oil-price shocks on the EU carbon market dynamics. Energy 254, 124172. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.124172

Ren, X., Li, Y., Shahbaz, M., Dong, K., and Lu, Z. (2022b). Climate risk and corporate environmental performance: Empirical evidence from China. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 30, 467–477. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2021.12.023

Ren, X., Tong, Z., Sun, X., and Yan, C. (2022d). Dynamic impacts of energy consumption on economic growth in China: Evidence from a non-parametric panel data model. Energy Econ. 107, 105855. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105855

Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., and Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manage. J. 53 (3), 617–635. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2010.51468988

Roberts, J. A., and David, M. E. (2017). Put down your phone and listen to me: How boss phubbing undermines the psychological conditions necessary for employee engagement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 75, 206–217. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.021

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., and Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 30, 91–127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

Rupp, D. E. (2011). An employee-centered model of organizational justice and social responsibility. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 1 (1), 72–94. doi:10.1177/2041386610376255

Rupp, D. E., Ganapathi, J., Aguilera, R. V., and Williams, C. A. (2006). Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. 27 (4), 537–543. doi:10.1002/job.380

Rupp, D. E., and Mallory, D. B. (2015). Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2 (1), 211–236. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111505

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., and Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Pers. Psychol. 66 (4), 895–933. doi:10.1111/peps.12030

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., and Salanova, M. (2006). A resource perspective on the work-home interface: The work-home resources model. Edu. Psychol. Meas. 66 (4), 701–716. doi:10.1177/0013164405282471

ten Brummelhuis, L. L., and Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. Am. Psychol. 67 (7), 545–556. doi:10.1037/a0027974

Timms, C., Brough, P., O'Driscoll, M., Kalliath, T., Siu, O. L., Sit, C., et al. (2015). Flexible work arrangements, work engagement, turnover intentions and psychological health. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 53 (1), 83–103. doi:10.1111/1744-7941.12030

Vlachos, P. A., Panagopoulos, N. G., Bachrach, D. G., and Morgeson, F. P. (2017). The effects of managerial and employee attributions for corporate social responsibility initiatives. J. Organ. Behav. 38 (7), 1111–1129. doi:10.1002/job.2189

Vlachos, P. A., Panagopoulos, N. G., and Rapp, A. A. (2013). Feeling good by doing good: Employee CSR-induced attributions, job satisfaction, and the role of charismatic leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 118 (3), 577–588. doi:10.1007/S10551-012-1590-1

Wang, X., Guchait, P., and Paşamehmetoğlu, A. (2020). Why should errors be tolerated? Perceived organizational support, organization-based self-esteem and psychological well-being. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. M. 32 (5), 1987–2006. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-10-2019-0869

Wang, X., Li, J., and Ren, X. (2022a). Asymmetric causality of economic policy uncertainty and oil volatility index on time-varying nexus of the clean energy, carbon and green bond. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 83, 102306. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102306

Wang, X., Wang, X., Ren, X., and Wen, F. (2022b). Can digital financial inclusion affect CO2 emissions of China at the prefecture level? Evidence from a spatial econometric approach. Energy Econ. 109, 105966. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105966

Williams, L. J., Cote, J. A., and Buckley, M. R. (1989). Lack of method variance in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: Reality or artifact? J. Appl. Psychol. 74 (3), 462–468. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.74.3.462

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 82 (1), 183–200. doi:10.1348/096317908X285633

Keywords: substantive corporate social responsibility attributions, work engagement, work meaningfulness, psychological safety, organization-based self-esteem

Citation: Guo H, Yan A and He X (2022) How substantive corporate social responsibility attributions promote employee work engagement: A triple mediation model. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1004903. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1004903

Received: 27 July 2022; Accepted: 14 October 2022;

Published: 26 October 2022.

Edited by:

Yukun Shi, University of Glasgow, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Guo, Yan and He. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoxing He, aGV4aWFveGluZ0Bjc3UuZWR1LmNu

Hao Guo

Hao Guo Aimin Yan

Aimin Yan Xiaoxing He1*

Xiaoxing He1*