- 1Pertanian dan Kehutanan, Universitas Iqra Buru, Namlea, Indonesia

- 2Pertanian, Universitas Islam Indragiri, Sumatra, Indonesia

- 3Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, Universitas Sriwijaya, Palembang, Indonesia

- 4Pertanian, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Palembang, Indonesia

- 5STIKes Maluku Husada, Palembang, Indonesia

Introduction

In the social sciences, social structure is a patterned social order in a society that emerges from and determines individual actions (Coleman, 2004). Society is seen as a social system, namely a pattern of social interaction consisting of an ordered and institutionalized social component. The characteristics of a social system, namely the social structure that includes the status and roles in social units, give rise to values and norms that will regulate the interaction between these social statuses and roles (Coleman, 1966). Therefore, social structures are structures and patterns that have internalized and become part of people’s lives. To observe the nature of the social structure, it is necessary to observe the community’s daily activities, except for the social structure of rural communities. The social structure in rural areas is related to patterns of social relations, interactions that are intensely intertwined, and create interdependence that takes place continuously, which will then form an organized pattern and the functions and roles that exist in the rural social structure.

Regarding the land conversion action, the social structure of the Ngringo community, which is increasingly open and dynamic, it is possible to open access to the land-use change action. For Durkheim (Coleman, 1986), social structure is as objective as nature itself. According to him, the nature of the structure is given to citizens from the moment they are born, just as nature has given to natural phenomena, whether living or not. We don’t choose to believe in something we now believe or choose the action we take now. We learn to think or do all of these things. The existing cultural rules determine our ideas and behaviour through socialization. In another case with Durkheim, Max Weber (Frank, 1990) sees social structure as the basis of the economy, status and power. So that society can rank high in one or two of the class level dimensions while being in a low position in other dimensions.

The occurrence of land conversion actions in Ngringo Village due to spatial relations and orbital causes an increase in the number of public settlements, commercial and industrial development, and economic facilities. This situation causes land prices to increase and encourages landowners to sell land to developers.

The Social Structure of the Ngringo Society

The social structure of the Ngringo village community is closer to that stated by Weber (Coleman, 1993), that currently the social structure that is formed is like ownership of economic resources, status and power but has not yet reached the level of capitalist society as previously stated. The social structure is intended to open or facilitate the accessibility of landowners to transfer land functions with rational actions to obtain additional value.

The process of changing the function of agricultural land that occurs in Ngringo village can be seen as a resource use in the context of individuals depending on other individuals because resources will maximize utilization. Because individuals cannot produce goods as resources, individuals must interact with others or work together to produce products. The Ngringo village community with ownership of geographic potential and land resources directs the community to interact with each other to produce an economic value that is beneficial to them individually.

Actions taken by the Ngringo village community are individual actions to process their resources to fulfil their daily needs. The selection of resources can only be achieved through interaction with others through groups or organizations. The decision to maintain and sell the land they own is the result of interactions built up in the community or group, conceptualized in the theory of rational choice to generate resources in their group. Mancur Olson (Deji, 2020), in his thesis entitled The Logic of Collective Action, focuses on seeing the rationality basis of individual participation in collective activities. Individuals who are rational and self-interested will not act to achieve common or group interests. Olson explained that individual involvement in collective activities is driven by self-interest. These personal interests can be channelled through group interests. This approach seeks to explain, in a decision making must see the most significant potential benefits at the individual level. Olson further explained that understanding why individuals are involved in a collective activity must be seen through the concept of costs and benefits. Neil Smelser (Durkheim, 2016) also proposed the theory of added value, arguing that there are six determinants of collective behaviour; each stage is influenced by the previous stage and then affects the next stage.

Conversion of agricultural land will have far-reaching impacts. From the economic aspect, it will reduce food security for agricultural production. The farming community will lose their jobs so that purchasing power decreases because farmers may not necessarily get new, better jobs.

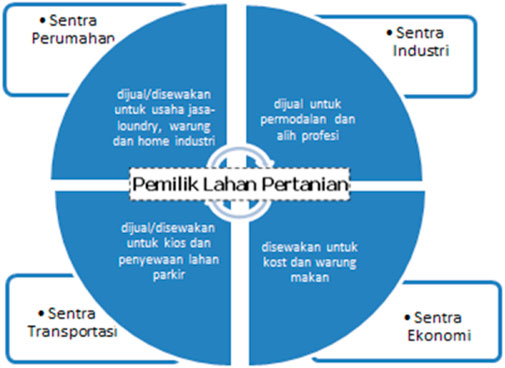

Matrix of Land Use by Ngringo Community

The benefits of agricultural land can be divided into 2 categories as shown in Figure 1: first, use values or use-values, which can also be referred to as personal use-values. These benefits are generated from exploitation activities, or farming activities carried out on agricultural land resources. Second, non-use values can also be referred to as intrinsic values or innate benefits. Included in this category are various benefits created by themselves even though they are not the goal of exploitation activities carried out by landowners. One example is the maintenance of biological diversity or certain species, which are not known for their benefits but may be very useful to meet human needs in the future.

Furthermore, the developer of the transmission theory (contagion) (Li et al., 2019) seeks to explain the network as a channel for transmitting attitudes and behaviours. The communication network in transmission theory provides contact. This communication network serves as a mechanism that exposes people, groups, and organizations to others’ information, messages, attitudes, and behaviour. But on the other hand, Coleman (Lowith, 2002) tries to explain a macro phenomenon that is mainly done by people and is an act that violates the rules and its erratic movement, and causes a change from a rational actor to a functioning system called “wild and collective behaviour. turmoil is a simple transfer of control over an actor’s actions to another actor carried out unilaterally, not as part of an exchange” (Midgley and Olson, 1969).

The explanation above indicates a correlation with Coleman’s delivery of the conversion of agricultural land in the village of Ngringo. Based on field findings, the conversion is carried out based on a different motivation or motive to meet the needs of the landowner so that justification for selling land becomes a habit and is even protected by norms as previously explained. The limited land area in the village will cause the mobility of residents to lead out of the village. This makes the village land area experience dynamics in its development, especially the dynamics in land use. Land use dynamics in the village area are due to the need for land for settlements and facilities and infrastructure to support economic activity (Opp, 2013). This condition is by Olsen (Putra and Pradoto, 2016) referred to as a collective activity that offers incentives in the form of rewards or benefits obtained by individuals who are involved in collective activities. The pattern of labour use and the structure of household income in rural areas are generally still closely related to agricultural land. They are strongly influenced by the condition of the agricultural land and what happened to the Ngringo village community, where the decrease in agricultural land there is relatively correlated with labour availability. In rural areas, the non-agricultural sector is growing, and agriculture is increasingly becoming land-saving and intensive.

Discussion

In the development process of the conversion of agricultural land, the Ngringo village community is faced with a structure where the family becomes a structure that can control every action of its members in the use of their private land. As with the distribution of inheritance in the form of land originating from parents, it is not regulated in village community institutions or culture to close opportunities for land sales. Several previous studies hoped that there was a role from the village or cultural institutions in the form of norms to overcome the conversion of agricultural land functions (Serpa and Ferreira, 2019). Still, in contrast to James Coleman, norms as a superstructure of the family were initiated and maintained by some people who saw the benefits resulting from the experience of norms and disadvantages. Comes from a violation of that norm (Smelser, 2013). The conditions in Ngringo village do not make norms as control over behaviour for collective interests but the role of social institutions such as the family which becomes the control over individual behaviour regarding the use of their land so that the family becomes an instrument to act according to their interests to realize the interests of the collectivity.

In the Ngringo community, land problems usually revolve around: First tenure and land ownership. Second, the ongoing process of conversion of agricultural land to non-agricultural functions by the village community. Third, there is a tendency to use open lands, which should function as interaction spaces or balancing other ecological functions of the land. Thus, initially a direct production factor, the land function has now turned into a strategic commodity material. Weber concurred with Marx on the economic basis for social class (Susilawati, 2019). Marx saw economics as the basis of a social structure, and the position of a person in this structure was determined primarily by whether he had the means of production or not. If this is extended, the possession of objects or assets becomes the primary basis for stratification.

So thus, a very open stratification will open up ample space for the occurrence of value-oriented social action as suggested by Weber (Vandergeest et al., 1988) in the typology of social actions. Besides, a norm related to specific actions will emerge when the socially determined right to control the action is vested not by the perpetrator but by other actors. This is in line with the consensus in the social system, which states that other actors hold to control actions. The norms that have been formed collectively must be adhered to by each individual, although they often conflict with or differ from the actors’ interests. Individuals who always heed established norms will undoubtedly get incentives, while those who violate will get sanctions. Norms are fundamental to all social groups, both mechanical and organic (Durkheim) or traditional or rational (Weber). From a sociological perspective, norms are “rules” that are expected to be followed by society. Generally, these norms are not stated explicitly as in statutory books. Norms are usually passed on through a socialization process about how people should behave naturally.

Coleman recognizes that norms become interrelated, social systems, but he sees such macro problems as outside the scope of his work. On the other hand, he is willing to take up the micro issue of the internalization of norms. He admits that in discussing internalization, he enters a dangerous area for theories based on rational choice. The norms held and governed by the people of Desa Ngringo are seen through rational choice theory as a system, and norms internalize standards of action as the basis for the formation of sanctions, norms of giving. Sanctions himself if they violate Coleman sees this in terms of the idea of one actor or group of actors trying to control another’s agar by demanding internalized norms on him (Wolf and Krause, 2014). Hence, it is in the interest of providing the actors to demand that the norms be internalized and controlled. He felt that it was rational when the effort could be effective with something more manageable.

Coleman sees norms from the point of view of the three critical elements of his theory of purposeful action, micro to macro at the micro-level and macro to micro. Is it a macro-level phenomenon that arises based on the act of norms at the micro-level aims? Once in place, norms, through sanctions or threats of sanctions, influence individual actions. Specific actions can be encouraged, while others are discouraged. Coleman (Young, 2015) argues that norms are initiated and administered by some who see the benefits resulting from observing norms and the harm resulting from violating norms. People who are willing to give up some control over their behaviour but in the process gain some control (through norms) over the behaviour of others. Coleman summarizes his position on norms: The central element of this explanation is to give part of the right to control over one’s actions and to accept part of the right of control over the actions of others, namely the emergence of norms. The result is that the controls held by each separately become broadly distributed across the whole set of actors who exercise that control.

The problem with land-use change in Ngringo village is that norms play a role as the leading supporter of the process. There are indirect sanctions given to those who oppose the wishes of corporate actors, such as for some land that is maintained because the price offered is below the wishes of the owner, the norm will direct the owner as an obstacle in the village development process so as has been stated that the process between actor actions and norms of mutual support in achieving benefits for several parties who change the function of agricultural land in the village of Ngringo.

What Coleman explains will in itself refute the social facts put forward by Durheim, according to Durkheim that social facts transcend the individual and are objective. Because social facts transcend individuals, the authors note that social facts include symptoms such as norms, moral ideals, beliefs, habits, thought patterns, feelings, and general opinions. With a frame of mind like this, Durkheim, in other words, wanted to express that the principle of social order is basically because every person, both cognitively, emotionally, and all their behaviour, is always and basically by social facts19. However, the phenomenon in the village of Ngringo indicates that individuals intentionally initiate these norms to achieve their goals. Understanding an actual norm will determine whether an action is considered right or deemed untrue by a group of people in society. Norms are deliberately created because people or a community will implement and maintain something that is considered valid and beneficial if the norm is obeyed. It will be detrimental if the norm is violated. Norms in society arise when there is a central element in which a person will give up some of his rights to control himself and receive some of the rights to control others. It is the result of the control of control maintained by a society that exercises the control. Because the transfer of control does not occur unilaterally, in this norm, there is a balance. Unlike in Ngringo village, where corporate actors dominate norms, norms are not an instrument of controlling action, but norms have become instruments of cultural pressure; this condition distinguishes the position of norms conveyed by rational choices from the findings in the field. For the author, norms are the most critical access to land conversion in Ngringo village.

Author Contributions

MU: planning and developing methods in studies and research Community Structure and Social Actions in Action of Land Conversion. MA: collecting data and conducting interviews. AL: do the drafting of articles until the submission process. RK: help analyze the findings and help draft articles. BSA: participate in making observations and help analyze the findings. WR: provide input and participate in compiling and improving the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Coleman, J. (2004). A Rational Choice Perspective in Economic Sociology. J. Econ. Sociol. 5, 35–44. doi:10.17323/1726-3247-2004-3-35-44

Coleman, J. S. (1966). Individual Interests and Collective Action. Public Choice 1, 49–62. doi:10.1007/BF01718988

Coleman, J. S. (1986). Social Theory, Social Research, and a Theory of Action. Am. J. Sociol. 91, 1309–1335. doi:10.1086/228423

Coleman, J. S. (1993). The Rational Reconstruction of Society: 1992 Presidential Address. Am. Sociological Rev. 58, 1. doi:10.2307/2096213

Deji, O. F. (2020). Gender Implications of Farmers' Indigenous Climate Change Adaptation Strategies along Agriculture Value Chain in Nigeria. In African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation, 1, 24. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-42091-8_13-1

Durkheim, E. (2016). Social Theory Re-wired. In Social Theory Re-Wired: New Connections to Classical and Contemporary Perspectives: Second Edition. doi:10.4324/9781315775357

Frank, R. H. (1990). The Demand for Effective Norms. J. Econ. Lit. 30 (1), 147–170. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/2727881.

Li, S., Nadolnyak, D., and Hartarska, V. (2019). Agricultural Land Conversion: Impacts of Economic and Natural Risk Factors in a Coastal Area. Land Use Policy 80, 380–390. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.10.016

Lowith, K. (2002). Max Weber and Karl Marx. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203422229

Midgley, L., and Olson, M. (1969). The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. West. Polit. Q. 22, 233. doi:10.2307/446187

Opp, K.-D. (2013). Norms and Rationality. Is Moral Behavior a Form of Rational Action? Theor. Decis 74, 383–409. doi:10.1007/s11238-012-9315-6

Putra, D. R. R., and Pradoto, W. (2016). Pola Dan Faktor Perkembangan Pemanfaatan Lahan Di Kecamatan Mranggen, Kabupaten Demak. Jpk 4, 67–75. doi:10.14710/jpk.4.1.67-75

Serpa, S., and Ferreira, C. M. (2019). The Concept of Bureaucracy by Max Weber. Ijsss 7, 12. doi:10.11114/ijsss.v7i2.3979

Smelser, N. J. (2013). Theory of Collective Behaviour. Theor. Collective Behav, 1–448. doi:10.4324/9781315008264

Susilawati, N. (2019). Sosiologi Pedesaan. Bandung: Penerbit CV Pustaka Setia. doi:10.31227/osf.io/67an9

Vandergeest, P., Buttel, F. H., and Marx, W. (1988). Development Sociology: Beyond the Impasse. United Kingdom: World Development. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(88)90175-1

Wolf, M., and Krause, J. (2014). Why Personality Differences Matter for Social Functioning and Social Structure. Trends Ecol. Evol. 29, 306–308. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2014.03.008

Keywords: land, rural, social structure, process, action

Citation: Umanailo MCB, Apriyanto M, Lionardo A, Kurniawan R, Amanto BS and Rumaolat W (2021) Community Structure and Social Actions in Action of Land Conversion. Front. Environ. Sci. 9:701657. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.701657

Received: 06 May 2021; Accepted: 14 September 2021;

Published: 28 October 2021.

Edited by:

Salvador García-Ayllón Veintimilla, Technical University of Cartagena, SpainReviewed by:

Iwan Rudiarto, Diponegoro University, IndonesiaMyrza Rahmanita, Trisakti School of Tourism, Indonesia

Copyright © 2021 Umanailo, Apriyanto, Lionardo, Kurniawan, Amanto and Rumaolat. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: M. Chairul Basrun Umanailo, Y2hhaXJ1bGJhc3J1bkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

M. Chairul Basrun Umanailo

M. Chairul Basrun Umanailo Mulono Apriyanto

Mulono Apriyanto Andries Lionardo

Andries Lionardo Rudy Kurniawan

Rudy Kurniawan Bambang Sigit Amanto4

Bambang Sigit Amanto4 Wiwi Rumaolat

Wiwi Rumaolat