- Office of Community Development, State of Louisiana, New Orleans, LA, United States

Globally, rapid and slow-onset socio-environmental coastal disasters are prompting people to consider migrating inland. Climate change is exacerbating these disasters and the multi-faceted causal contributing factors, including land loss, livelihood shifts, and disintegration of social networks. Familiar with ongoing disruptive displacements, coastal Louisiana residents are now increasingly compelled to consider permanent relocation as a form of climate adaptation. This paper elicits and analyzes coastal Louisiana residents’ perceptions of socio-environmental changes as they pertain to relocation as adaptation and the precariousness of place, both biophysically and culturally. It investigates how these external mechanisms affect relocation decisions, and empirically expand on how these decision-making processes are affecting residents internally as well. Research methods include semi-structured interviews with coastal Louisiana residents, participant observation, and document analysis. The paper integrates literature on environmental migration, including climate-driven; regional studies on Louisiana, and disasters, with empirical, interview-based research. It is guided by theoretical insights from the construct “solastalgia,” the feeling of distress associated with environmental change close to one’s home. The findings suggest that residents’ migration decisions are always context-dependent and location-specific, contributing to a broader understanding of coastal residents’ experiences of staying or going.

Introduction

This research centers on understanding the links between migration possibilities and the influence and experience of four interrelated factors: social networks (i.e., faith-based networks, civic organizations, family, cultural and heritage identities, etc.), the multi-layers of disasters (specifically hurricanes and the oil spill disaster in 2010), and place, including sense of and attachment to it. Climate change is threaded throughout and shapes all factors. Research is based upon qualitative data collection with coastal Louisiana residents who are engaging in decisions of both formal and informal relocations.

Climate change related risks and hazards, feelings of loss, and socioeconomic status arose as dominant underlying drivers within the larger themes. Residents frequently cited these factors as components of their decision-making processes. Placing residents’ considerations of migration within a broader socio-political, cultural, and economic context facilitates a more nuanced understanding of why many coastal Louisianans are considering relocating.

The decision to migrate away from a place one has a long-standing connection to is inevitably complex and emotional. It can challenge both individual and collective identities (Mendoza and Morén-Alegret, 2013) and ultimately involves a (re)negotiation of oneself and others (Boccagni and Baldassar, 2015). There is a deeply rooted sense of and attachment to place and to one another in southeast Louisiana. Yet, both are under threat, as the land disappears and communities disperse inland. As such, when the livability of a beloved place is compromised, it is often accompanied by feelings of sorrow and loss (Cunsolo and Ellis, 2018) that are not easily quantifiable.

Community migration operates through both formal and informal processes. Informal migration is a process whereby residents move individually to safer, often inland, locations as a result of multiple shocks and stressors. Such informal migrations, which may occur over several generations, often result in a gradual loss of community and sense of place. Formal migration, as discussed in this research, is a more coordinated process involving state and local policymakers who are working with a community to voluntarily relocate. Solastalgia, as a conceptual tool, permits a richer understanding of the losses Louisianans are feeling and how that subsequently affects migratory decision-making.

As an example of a formal process of a community relocation, a majority of residents of Isle de Jean Charles (or “the Island”) in Louisiana are preparing to resettle together to an inland site better shielded from the impacts of climate change. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) National Disaster Resilience Competition (NDRC) grant is funding the effort. Isle de Jean Charles is home to mostly American Indians who reside in a rapidly changing environment wherein a cascade of emotive and physical losses are occurring. Yet residents’ connection to the Island remains. These deep cultural and historical bonds prompted the State of Louisiana’s Office of Community Development, as the administrator of the grant, to work with Island residents to configure a way for them to keep their land and homes after relocation in order to maintain a relationship to their ancestral homeland. For many current and former residents, even those who were displaced from the Island as small children, there is a deep and emotional attachment to the land that continues today. As this sacred place further erodes and people move away, Islanders are experiencing grief and mourning (Yawn, 2020).

Following the introduction, the theoretical background section reflects the scholarly works that ground the key migratory decision-making factors emerging from the data, including the concept of solastalgia. Following this, the methods section describes a qualitative approach used to broadly gather and then distill resident perspectives on possibilities of migration in three southeastern Louisiana parishes: this paper’s empirical contribution. The combined results and discussion section situates residents’ experiences in their social, political, and economic contexts, highlighting the blending of the many multi-scalar influences in migratory decision-making processes. It provides an articulation of criteria as cited by interviewees grappling with the emotional ramifications and underlying meanings of these decisions in a dynamic and shifting place. The resettlement of Isle de Jean Charles completes that section. Concluding, the remainder of the article highlights the key findings and empirical contributions, the broader implications of these findings and their transferability.

Theoretical Background

Migration and environmental change are a “research frontier,” widening the understanding of migratory patterns in scale and complexities (Adger et al., 2015, p. 2). Despite robust discussion and theorizing in the arena of environmental migration (Castles et al., 2014) there remains a lack of empirical accounts of the role of environmental change (and other prevailing drivers) in migration (Kelman et al., 2017), and until recently, little attention paid to sense of and attachment to place (Dandy et al., 2019). Accordingly, this article focuses on empirical accounts of often emotion-laden regional migration decisions. It offers opportunities for a more wide-ranging depiction of migration dynamics that go beyond census data or population numbers (Dalbom et al., 2014; Hauer et al., 2019). Highlighting the sentiments and perspectives of those affected by ongoing degenerating environmental conditions is vital for understanding migratory processes and can only be found in talking to the residents themselves (Kelman et al., 2017). They are also often overlooked in migration studies (Barrios, 2014; Boccagni and Baldassar, 2015).

The decision-making surrounding migration is occurring in places where multiple influences and socio-environmental networks intersect; where people derive, construct, and re-construct their identities, all while establishing and maintaining both human and non-human relations in a complex landscape (Hedberg and do Carmo, 2012; Pellow, 2016). These interrelationships between place and migration are complex and stand to benefit from deeper investigations (Hess et al., 2008; Hugo, 2008). How people come to interpret climate change risks from their specific cultures and places remains inadequately researched (Tschakert, et al., 2017).

Place is a structure that subsumes both human experiences and the material world in which those experiences happen (Casey, 1997). It is one of numerous dimensions of risk correlated to hazardous environmental exposures, including climate change, which has uneven spatial distribution among places (Dolan and Walker, 2006; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change (IPCC), 2014) and race and class lines (Marino, 2018). Relatedly, sense of place is a multidimensional concept that embodies emotions, beliefs and behavioral actions specific to particular geographic settings (Tuan, 1974). These interconnections of often-everyday experiences vary in forms of expression, emotion and strength and can be so influential as to be an integral building block in the construction of individuals’ identities (Massey, 1991; Mendoza and Moren-Alegret, 2013). Place attachment is the meaning conferred on the felt connection with place. Various authors (Burley, 2010; Jenkins, 2016) have identified the distinctive attachment to place for Louisiana residents. Some residents have such a strong sense of place that migrating embodies a forfeiture of their way of life, not simply a place to live (Jenkins, 2016).

Social networks are a component of understanding the emotional ties to place and influences the decision to migrate (Bronen and Chapin, 2013). Whether relocation is forced or voluntary, multiple disciplines show that it creates substantial stress for those involved, disrupting or impeding social networks (O’Sullivan and Handal, 1988; Riad and Norris, 1996; Castles, 2003; Dun, 2011). The stress can be related to shifting identities, including individual, as well as landscape and population alterations (Oliver-Smith, 1991; McHugh, 2000; Williams, 2006; Klinenberg, 2016).

Migration outcomes may benefit an individual or household, but can have adverse effects on the adaptive capacity of the community where they once lived. There is limited systematic research on multi-scalar impacts of adaptive migration on both those who migrate and those who do not (Schade et al., 2016). Barrios (2014) and Browne (2015) emphasize the crucial presence of social relations among spatially close friends and family during relocation and resettlements. When hardships such as deteriorating environmental conditions or a large storm place an undue burden on residents, many people report turning to their social networks for assistance (Adger et al., 2015; Aldrich 2012; Bodin and Crona, 2009; Folke, et al., 2005; Tompkins and Adger, 2004). This is a common response in coastal Louisiana communities (Colten et al., 2012; Colten et al., 2015).

Such is the case, for example, of migration from the small Island nation Tuvalu. Keeping social groups together demonstrates this is a significant motivation for residents who must contend with dramatic declines in living conditions due to sea level rise and other small and large-scale disasters (Shen and Gemenne, 2011). A similar concern emerges for Native Alaskans in rural communities who are attempting to relocate themselves due to erosion of the land surrounding their village (Marino, 2012), as well as for the residents of Isle de Jean Charles, who will largely relocate together, maintaining their spatially close social relations to one another.

Research underscores that decisions of migration are influenced by environmental factors, but ultimately shaped by a complexity of often-simultaneous forces, including social, political-economic and cultural processes (Black et al., 2011; Oliver-Smith, 2012). This paper pays particular attention to the socio-environmental factors specific to the Louisiana coast influencing residents’ migration decisions in the geographically bounded places they currently reside in or may in the future. The majority of residents interviewed expressed their desire to remain in situ (Simms, 2017).

Increasingly, calls to examine migrations within a broader, more holistic context, particularly when it comes to an inclusion of political and socio-economic processes, are imperative (Mendoza and Morén-Alegret, 2013; Barrios, 2014; Greiner and Sadapolrak, 2016). Understanding that social inequalities are present as both preconditions and outcomes of migration prompts significant questions about the effects and processes of migration. Research that incorporates these understandings can inform the prevention of longstanding inequalities from simply being repackaged and re-emerging in a different form (Schade et al., 2016).

The emotional dimension of the connection between socio-environmental degradation and migration possibilities experienced by residents may be explained by the place-based concept “solastalgia” (Albrecht, 2005). Defined as the distress experienced when one’s sense of place is under assault due to degrading environmental conditions of a home region, this concept is applied throughout this research. Etymologically, the word refers to pain surfacing due to a reduced ability to draw ‘solace’ from one’s surroundings (Albrecht et al., 2007). Solastalgia is often signified by a struggle to find solace in a place where one once found comfort; it is a feeling of homesickness when still at “home.” These feelings are often connected to a sense of powerlessness and an inability to influence the social and biophysical transformations causing the distress. Amidst coastal Louisiana’s acute and slow-onset disasters, the subsequent widespread economic, cultural, political, and social multi-scalar effects, many residents are feeling emotions that can be considered symptomatic of solastalgia, while also contemplating relocating themselves and their families.

As described in a study conducted with residents living in an area recently experiencing a destructive forest fire, researchers explore the psychological connection between the landscape and human health. They found that the losses caused by the fire instigated feelings of grief, violating the endemic sense of place for those living in the area. For example, over 71% of residents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, ‘‘I feel like I have been grieving for the loss of the forest affected by the Wallow Fire” (Eisenman et al., 2015). Wildfires, hurricanes and technological disasters such as the 2010 oil spill explosion, dramatically change landscapes. Solastalgia is an effective framing mechanism that can illuminate the feelings arising from the loss of familiarity in places where people once sought comfort and connection.

Solastalgia is grounded in the sense of place and place attachment constructs, permitting an exploration into deeply interconnected, dynamic, and nested social-ecological systems. This concept assists in reflecting on and analyzing how residents’ identities are interwoven with place and serves as a vital category of analysis in understanding how this affects migration possibilities.

Methods

This article combines four sets of formal, in-depth interviews with 110 Louisiana residents in three counties (“parishes” in Louisiana) conducted between 2012 and 2016. Interviewees told their own histories and experiences in response to open-ended interview questions broadly focused on the social effects of land loss and coastal hazards. Data collection instruments included semi-structured interviews, focus groups, participant and non-participant observation, fieldnotes, thematic coding and content analysis. Combining analysis of primary and secondary sources provided broad-based insight into the implications and further effects of migration possibilities for coastal Louisiana residents.

In-person interviews, rather than alternate qualitative methods, i.e. census surveys or questionnaires, were selected to accommodate a broader and more nuanced array of experiences and views (Dunn, 2005), including facial expressions, body language and emphasis of certain words. The interview as a key qualitative method assists and deepens the understandings of the ways people relate to place, social networks, and identities (DeLyser and Sui, 2013). They facilitate refining the pieces that make up a process, i.e., a decision to leave one’s home. Residents responded to interview questions largely in story form. Storytelling is a personal experience narrative (Denzin and Lincoln, 1994), and should be seen and interpreted as interactive text (Miles and Crush, 1993).

In analyzing the data, the process was inductive, drawing upon concepts underscored by the interviewees and examined from a “bottom up” approach. The qualitative analytical techniques of thematic coding and content analysis were merged. Thematic coding included compiling the interviews and identifying emerging themes and concepts. Following this, content analysis was employed to code specific themes, phrases, interpretations, ideas and perspectives (Suchan and Brewer, 2000).

The first interview set, conducted between February 2012–June 2013, Terrebonne Parish residents were asked to respond to questions about their observations of socio-environmental change, specifically land loss, in their parish. The interviews centered on the Terrebonne Parish marsh and land restoration plans as laid out in Louisiana’s Comprehensive Master Plan for a Sustainable Coast [Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana (CPRA), 2012)] and how interviewees anticipated the plans would affect them and their families. In the second set of interviews (October 2013–February 2015), residents were asked questions about resilient and ongoing social practices (Colten et al., 2012) taken up by mobile and immobile residents. The interviews explored the role of social networks in the anticipation, preparation, reduction of vulnerability and/or recovery from disturbances, such as hurricanes and the 2010 oil spill disaster (Colten et al., 2015). In the third set, interviewees who had direct experience with the 2010 oil spill disaster were sought out to elicit responses to “changing social effects,” i.e., community livelihoods, health and environmental changes. The final interview set sought information about specifics related to migration. Both residents and those with professional/public roles connected to relocation/resettlement efforts were interviewed. Residents were asked about their social networks as related to the socio-environmental changes in their surrounding communities. Both groups were asked their thoughts or ideas regarding local migrations, and the factors they see as anchors to remaining in situ or conversely, factors acting as “tipping points” to force migration.

These four broad categories provided a loose framework of questions and allowed interviewees to provide the content. The sets of interviews centered on varied, although interrelated themes. The shared themes threading through each of these sets of interviews are a sense of and attachment to place; family, friends and social institutions; identities rooted in the socio-environmental practices of residents in and around their homes; and intertwinings with the possibilities and practices of migration. Combining these interviews assists in telling a broader story of what factors affect migratory decisions and how these decision-making processes are affecting residents.

Interviewees

A nonprobability sampling technique commonly referred to as “snowball sampling,” was employed for contacting and interviewing residents. The majority of interviewees lived in Terrebonne Parish (63%), while others lived in Lafourche Parish (24%), or were current or former St. Bernard Parish residents (14%). (Table 1). Interviews were conducted with individuals exemplifying the principal ethnic groups, sexes, and various income categories. Most of the interviews were conducted in either the residents’ offices or homes. All interviews were recorded. The majority of interviewees had lived most or all of their lives in their respective parishes, experiencing hurricanes, land loss, and/or the 2010 oil spill disaster. In most cases, the research participants had experience with all three. Interviewees held a variety of occupations and identities including state and federal government officials, industry employees, health workers, academics, community-based organization leaders, activists, journalists, bankers, oyster, alligator and wetland plant farmers, crabbers, fishers, small and large business owners, oil workers and others. Occasionally an interviewee held more than one of these roles. Biophysical and socio-cultural changes are rapid and ongoing in these communities and migration is something that a number of residents interviewed think about and discuss regularly.

Interview Sites

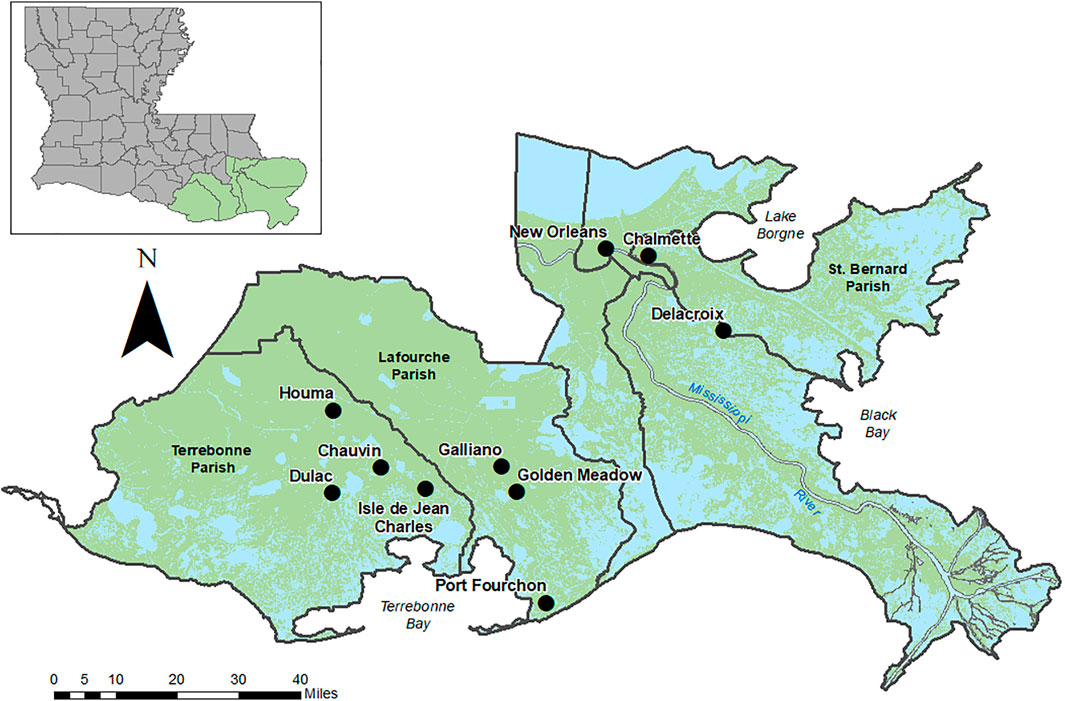

The three Louisiana parishes wherein interviewees reside, Terrebonne, Lafourche and St. Bernard, encompass and are shaped by the Gulf, wetlands, bayous, and rivers, chiefly the Mississippi and its distributaries. (Figure 1). Rivers and their freshwater and sediment are integral to adding and nourishing land and cultural traditions across these parishes. Economies here are linked and dependent on coastal resources, including commercial fishing, shipping, and oil and gas and supporting industries. In Terrebonne, more than 85 percent of the parish is water and wetlands, with freshwater marsh in the northern areas, brackish marshes further south, and saltwater marshes near the coast. Lafourche, to the east, is 28 percent water [Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana (CPRA), 2017], alternatively.

Residents of St. Bernard and Terrebonne parishes could be among the first U.S. regions to see federal financial support removed because of increased federal disaster spending (Flavelle 2016). They are among a small number of parishes/counties with the highest number of per capita households requesting disaster assistance more than once since 1998. Specifically when it comes to repetitive loss claims, Louisiana ranks at the top. With approximately 70–80 percent of coastal homeowners foregoing flood insurance, Terrebonne has 2,000 repetitive loss properties, St. Bernard 1,207 and Lafourche Parish has 489 (among the lowest) [Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana (CPRA), 2017]. Lafourche Parish has not been immune to hurricane damage, flooding, subsidence and coastal land loss, but compared to Terrebonne and St. Bernard parishes, the damages are considerably less.

The geographies of these three parishes play a significant role in past, present and future migration patterns. For example, the extensive hurricane protection system in Lafourche is a principal reason many interviewees claim that neither they nor others in their social networks are planning to move. Many Lafourchians instead link migration changes to the ebbs and flows of the oil industry. The lack of a comprehensive hurricane protection system is a key factor in why Terrebonne Parish interviewees are considering moving or expressed concerns about staying. Many of them impart hope into faster and better-funded construction of the Morganza to the Gulf Structural Protection System. Northeastern St. Bernard Parish, where the majority of parishioners reside, is largely protected by a hurricane and flood protection system. In 2006, a year after Hurricane Katrina, more than 50,000 of the approximately 67,000 residents of St. Bernard Parish were living in different parishes (Louisiana Recovery Authority, 2006). In 2021, it has still not returned to pre-Katrina levels.

Results and Discussion

The Louisiana Coast, A Place of Uncertainty, Stressors, and Beauty: “There’s No Status Quo for Coastal Louisiana—It’s Always Changing”

As coastal residents contend with the deeply pervasive anxieties and uncertainties embedded in the COVID-19 pandemic, historically high unemployment rates, and historically low oil and gas prices, a global recession, and a record-breaking Atlantic hurricane season, conversations of migration are undoubtedly increasing. Will this be the year we will have to leave?, many will ask themselves.

Louisiana ranks third in the United States for percentage of residents surviving below the poverty line (West and Odum, 2016). Confidence in Louisiana’s oil and gas industry as a reliable source of income and employment has declined in recent decades (Austin, 2006), with a general upswing in an inability to maintain natural resource–based livelihoods (Marks, 2012; Horowitz, 2014). In interviews, residents emphasize the necessity of a multitude of livelihood strategies, changing understandings of the landscape, profound feelings of nostalgia, and the negotiations and compromises they are making both with themselves and one another.

In all of this, there lies an overarching theme: uncertainty. Most coastal Louisiana residents are well-acquainted with living in a persistently unpredictable context. Combined with longstanding stressors related to losses of social networks and financial resources, attempts to gain stability in unresolved life circumstances are referred to as “chronic disaster syndrome” (Adams et al., 2009). This in itself is a stressor, with some residents indicating this accumulation can be a “tipping point” in the ultimate decision to relocate.

Whether older and retired, middle aged and working in the oil fields, or younger and unable to finish high school, the research participants, would most often first illuminate the positive aspects of the places they live. They use descriptors such as “magical,” “a playground,” what “makes (my dad) feel alive,” and being “mesmerized by the sheer beauty of the bayous and lakes.” Contemporaneously, they share concerns and fears that “we will all be waterfront property” (resident interview, 20 July 2015). A member of a family owned maritime shipping business, quipped, “the close proximity to the Gulf? It will become a hazard to our livelihoods” (resident interview, July 29, 2015). These contradictory descriptions and peoples’ relations to them capture the intensely strong connection to the region, while also recognizing the inevitable changes embedded in an increasingly uneven landscape of risk. As one Terrebonne Parish resident working at a local community center predicted for her region: “I don’t think that a lot of people in the parish know how they’re going to be affected in the future. And then it will be too late” (resident interview, July 27, 2015). Over the last twenty years, more and more migrations are occurring due to socio-environmental stressors, disasters and climate change.

Every day Louisiana’s Gulf Coast undergoes a physical, social, and cultural reshaping. In tandem, so do the associated meanings and everyday practices residents perform in relation to the places they live. A social worker explains, “the oil spill affected family stressors—financial situations, people fishing or shrimping. It affected everyone and trickled down to the families, grandma and grandpa and mom and dad and the kids. The culture is shifting and changing” (resident interview, July 24, 2015). Places are awash with meaning, and incorporate both existential aspects as well as emotional connections (Mendoza and Morén-Alegret, 2013). They also play a central role in the development of one’s identity and social connections. When processes of change, such as coastal land loss occur in a cherished place, peoples’ identities are affected, too (Burley, 2010).

Alongside shifts in identity, a changing sense of place occurs. A disruption in the links between sense of place and identity can cause negative psychological and health effects (Lewicka, 2013). As residents witness their burial grounds, playgrounds, and homes erode into the Gulf, feelings of solastalgia are triggered, eroding place-based identities (Tschakert et al., 2013). As that connection corrodes, and more becomes uncertain, the pressure to migrate can intensify.

Terms such as climate change, migration, moving, relocation and resettlement can be contentious subjects in these parishes. This opposition is related to the main themes in this article—a robust sense of place and difficulty severing ties with the associated identities to the place and social networks therein. Many residents would speak about others whom they knew to be considering migration rather than themselves; or as one resident, a self-described “lifelong volunteer and community advocate” phrased it, “people won’t say they’re thinking about moving, but you better believe that behind closed doors they’re talking about it” (resident interview, June 6, 2013).

Climate Changes on the Coast: “Canary in the Coal Mine for Climate Change”

Coastal Louisiana is experiencing the highest relative sea-level rise (RSR) and subsidence rates in the United States (Marshall, 2013). Sea levels in Grand Isle, LA, are two feet (0.6°m) higher today than in 1950 [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA), 2020], with the entire coast seeing more than an eight-inch (20 cm) difference from 2006 to 2011 [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA), 2012]. An NGO director identifies these escalations as “an inevitable stress for the beginning of hurricane season. There’s a common sense of anxiety that never existed before ten years ago1” (resident interview, August 6, 2015). The distress and losses triggered by socio-environmental changes to the places people love can result in cumulative mental, emotional, and spiritual health impacts (Albrecht, et al., 2007; Askland, et al., 2018). These impacts can not only affect individuals, but can also lead to community distress (McNamara and Westoby, 2011). Residents often expressed their thoughts on the improbable viability and connectivity of their communities, while others hoped that once protection measures such as large-scale levees were put into place, their communities could be sustained, and perhaps grow, especially if oil and gas prices go back up.

Most interviewed residents do not frame migration possibilities in terms of climate-induced changes, yet will cite stronger storms and land loss, both exacerbated by climate change, as reasons to consider it. A handful characterized migration considerations as happening under the web of a “strong climate signal” (Burkett, 2016), including an elderly resident who had lived all his life in lower Terrebonne Parish. He noted: “what’s happening to us in south Louisiana is going to happen to every low-lying coastal community throughout the world if global warming is as significant as everybody says that it is” (resident interview, November 11, 2015). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that as global mean sea levels rise, historically uncommon extreme sea level events i.e., currently hundred-year events, will be annual events worldwide for most low-lying coastal communities by 2050 (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IPCC, 2019). Another resident, a licensed social worker who continues to work in Terrebonne Parish, but moved about ten years ago to upper Lafourche Parish, notes that the effects of climate change are already here. He says, “an increasing concern is climate change. We are having more intense hurricanes when they do come” (resident interview, July 17, 2015). Sans major adaptation efforts, risks related to relative sea level rise (land erosion, salinization and flooding) along all low-lying coasts are expected to significantly increase by the end of the century.

A Tipping Point: “Sitting Ducks”

The magnitude, coupled with the sheer number of disasters to affect southeast Louisiana is profound. Residents’ acknowledgement of a potential tipping point indicates that there is certainty in the uncertainty, or, put another way, it isn't a matter of if, but when relocation will be inevitable for them. The uncertainty itself, however, did not appear to be a tipping point or a key reason to consider migrating. Residents identify myriad other “tipping points” as well as the overall vulnerability of their region. While a number of residents returned to their homes after hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 or Gustav and Ike in 2008, many now describe their current position in their homes as being precarious, or, as one resident, put it, “they’re sitting ducks and they’re gonna flood again” (resident interview, July 7, 2015). The tipping point could be an instance of widespread flooding, an emotional incapability to adapt, a financial inability to repair one’s home (again) following a storm, or being “one storm away.” Or it could be insurance-related, as described by a church volunteer in a focus group in Houma, “insurance is very high, I may have reached the tipping point with insurance. I’m working so hard right now; I’ve just got to survive. We keep our prayers up” (resident interview, November 6, 2015). Despite the significance of relevance to policy development, climate-induced socio-economic tipping points remain under-researched (van Gingkel et al., 2020).

Scaling up from the individual to the parish level and in the context of multi-disasters, one public official in Terrebonne Parish stated, “we are one major event away from being gone. We are dead without half our population to draw in the numbers” (resident interview, June 15, 2015). This comment reflects the fear that many residents expressed in terms of being in a precarious and unstable situation at both the individual and parish level. As a solution, another public official offered, “we need to stay away from disasters and focus on developing what we have. The joker in the deck is if we have another disaster and we haven’t done enough to reinvent what was lost” (resident interview, July 28, 2015). When asked if he thinks that he and his family will continue to live where they do, he sighed, and said, “they (his kids) want to live here, too. I don’t have any intentions of moving, but if it comes to it, I may have to.” For some residents, there is a deep sense of grief and heartache in conceding that a tipping point for migration exists.

Solastalgia acknowledges the tension and often, sadness, inherent in considerations of migration. The interaction between treasured places and what has been lost due to uncontrollable forces was a common interview theme. One resident, a single mother and school administrator, describes what her bayou town once felt like to her: “When I was a kid in Montegut, it was so clean. There were flowers everywhere; it was so beautiful and pristine. The storms are taking that away” (resident interview, October 20, 2015). In describing Montegut the way that she remembers it, this resident is re-creating and imagining spaces and places that have changed, are infused with memories and her sense of self—all drawn in large part from the past. Peoples’ affective relationships to the landscape are dynamic, often emotional, and ties can run deep. They are nested collections of human experience, where people are intimately knowledgeable about the traditions that made it possible for their families to make their lives on the coast.

Social Networks: “I Want to Move Back”

Social networks heavily influence residents’ thought-processes and decision-leanings of whether to remain in place or migrate more than ten miles from their current residence. They also often serve as survival tactics in the face of hardships; generate and build trust; facilitate social mobility; offer business opportunities; and dissuade, or persuade residents to eventually migrate. The connections and disconnections between and among residents and their churches, their grandbabies and employers, their boats and the money gained from catching and selling shrimp, but also feeding one’s family with the day’s catch, are contingent on social networks and shape migrations.

Social ties are robust in these three parishes. In asking an offshore oil employee born and raised in Houma to describe his community, he said, “Houma is a family type community with a strong connection between family and friends. That’s a tight seal connection there, too” (resident interview, July 16, 2015). One possibility for the “tight seal connections” was described by another resident as key to subsistence. When asked why he thinks social networks are so important in coastal Louisiana, he sums it up in one word: “Survival. We have it ingrained in us that we have to depend on each other for survival” (resident interview, August 5, 2014).

Resilience is frequently operationalized through social capital (Mayer, 2019), and as these relationships weaken, residents’ recovery and re-stabilization from disasters also suffer. Disaster scholars have shown the devastating consequences of the dissolution of social networks, which earlier had served to maintain levels of confidence when facing uncertainty (Chamlee-Wright, 2010; Browne, 2015).

The places described by residents often serve as nodes wherein social interaction happens (Castells, 1996). These nodes can operate similarly to magnets, pulling in members of social networks. Indeed, it is the places where people come together and connect that enable place-based social networks to gain strength. Residents consistently identified their social networks, whether places of employment, community-based organizations, or school environments, as determinants of staying or going, such as these two differing statements from a Lafourche librarian, born and raised in the parish, and a Terrebonne public official, respectively: “My family is here, I wouldn’t move” (resident interview, July 13, 2015) and “I have a son here with kids. If he goes to Houston I will go too… I have to be with family, you know” (resident interview, July 10, 2015). Social networks play a role in available services, resources, and support groups used to meet the needs, social and otherwise, of residents. In order to avoid dissolution of these support systems as people choose migration as adaptation, social networks must adapt as well.

Social networks not only are key factors in the decision as to whether or not to migrate, but where and how to migrate due to environmental circumstances. (Brown, 2002; Airriess et al., 2008; Cheng, 2009; Curran and Saguy, 2013; Bankston, 2014). A homemaker in an interview focus group, explained that she continues to live in Chauvin because her family also resides there. But, “once they’re gone,” she said, gesturing to her parents-in-law, “I’m leaving. Going further up” (resident interview, August 5, 2014). This communication lays plain the force of social networks in many of these residents’ lives. Another young resident, attending college in New Orleans, affirmed the power of social networks in his rationalization of why he hopes to return to Terrebonne Parish where he was raised. Explaining, “I want to move back because of my family history. I want to continue working where my grandfather works, my great-grandfather worked and my great-great grandfather worked. It’s very humbling to keep on with traditions and ways of life in that way” (resident interview, November 11, 2015).

This 19 year old resident spoke strongly and proudly of the place and longstanding familial connections where he was raised, citing his grandfather and mother for instilling in him the importance of maintaining these connections. “I am who I am today because of my grandpa. It’s why I take pride in where I’m from and our heritage and have such an interest in what it was like back then” (resident interview, November 11, 2015). The social networks this young resident is referring to are not just ones existing in current time, they are ones where family members have passed away, yet still maintain significance and influence long after their deaths. One resident, an insurance agent living about a stone’s throw from where she was born, clarified, “people want to live where their ancestors were and where their roots are” (resident interview, July 31, 2012). These are networks rooted in the places where these families were born and raised. They are part of the reason residents struggle with the decision to leave and feel a nostalgia for the way things once were, despite a preponderance of other compelling reasons to relocate away from the coast.

Similarly, in identifying place as a structure that subsumes both human experiences and the material world in which those experiences happen (Casey, 1997), a Terrebonne Parish retired commercial fisherman, describes these similar connections, while also stressing the critical link between food and loved ones in strengthening bonds: “the environment provides the opportunity for a connection to your family and your friends. Because how often do you go fishing or shrimping and then have a meal or crawfish boil? A lot of it is tied to what the opportunities the environment provides to the people” (resident interview, November 11, 2015). Food, particularly local harvests, serves as an avenue through which residents connect, strengthening and building their social connections.

Social networks take into account both human and non-human factors, facilitating the flows of activities and knowledge between places (Hedberg and do Carmo, 2012; Pellow, 2016). Humans and non-humans are each embedded in these networks, determining which resources are desirable and accessible and when (Zoomers and van Westen, 2011), and ultimately concluding if migrations are even a viable option. When asked if he would consider relocating, an elder resident of Isle de Jean Charles explained that his “preference is to stay put, stay home. But, if we can stay together as a tribe to move, I will consider moving to be with them” (resident interview, August 17, 2012).

Social networks are complex and multi-varied. Residents rely on strong, tight-knit social networks and have a fierce attachment to the place they live. They are cognizant of the multiple disasters they have experienced and challenges this has already wrought, including disbanding some of their social support systems.

Multiple Layers of Mental Health: “That was the Biggest Thing—A Lot of Depression, Anxiety and Stress”

Residents contend with multi-layers of disasters, whether slow-onset, such as land loss; acute, as in the destructive aftermath of a hurricane, or in-between, such as the oil spill disaster in 2010. The oil spill disaster in particular engendered intense and cascading social effects and stresses including navigating the claims and litigation processes, unpredictability of seafood stock and market viability, and cleanup. Further exacerbating state and parish budget woes and delaying new industry-related investments, job losses numbering in the thousands soon rippled through the state (Thompson, 2015). At the height of the disaster, when the well was uncapped and about a million gallons a day were spewing into the Gulf, several residents spoke about their fear of permanent displacement. One interviewee, a former nurse and parent of three children, told me “(our child) is asthmatic. We thought that we’d have to move” (resident interview, June 15, 2015). Residents reported that the emissions from on-site burning of surface oil created inhospitable conditions for some locals. A barbershop owner reflected on the cumulative impacts his community had faced, “Sometimes we think we’re leaving. It’s very emotional. And (we feel) anger. Because this is our home!” (Resident interview, June 15, 2015).

A number of interviewees, particularly those involved in mental health services, mentioned the toll repeated disasters and their resultant crises take on residents. As with climate change, multiple disaster exposures are associated with decreased mental health. Both can act as “risk multipliers,” incidentally setting off or exacerbating preexisting health conditions (McMichael, 2017). The culture of risk residents contend with is ingrained into their lives and is bound to generate intense effects in everyday social life (Cope et al., 2013).

When combining vulnerabilities correlated with age, ethnicity, and poverty or low-income status, the multilayers of multi-disasters are even more acute. One resident, who was in current conversations with her partner about whether to move closer to the coast to be nearer to their parents, said, “we’re not doing a good job of facing those challenges (the effects of climate change including stronger storms and sea level rise) in a way that shows that people can continue to live in those communities” (resident interview, July 24, 2016). Much of the coastal population is above the poverty level, but many just barely (Colten, 2017). Thus, they are at greater risk of an increased economically disadvantaged situation if there are disruptions due to intense tropical weather, restoration projects that impact the habitat of the resources they pursue, flooding of their communities, or sustained economic troubles, such as the pandemic. One resident, a former non-profit director, offers some advice: “We need to address those who are so vulnerable in those communities. I think that the safer you make everybody in a community as a whole, hopefully that’s fewer resources on the back-end that you’re going to have to spend to deal with devastating situations” (resident interview, November 11, 2015). Providing opportunities for residents to make decisions of adaptation that are financially and socially supportive will facilitate more secure futures for families on the brink (Cardona et al., 2020).

In 2010, the oil spill disaster quickly revealed how a scenario could embody multiple, interconnected interests and differential power relations. The spill brought to the forefront a long-occurring uneven relationship that for decades placed residents at the mercy of global economic instabilities. Residents spoke of a sense of environmental injustice happening to the surrounding human and non-human ecosystems, contributing to feelings of displacement without leaving home. Combined with place-based limiting factors such as land loss, poverty, climate change, sea-level rise, stronger and more frequent tropical storms, the lack of control over one’s livelihood, home and at times, family, can be debilitating.

Many residents spoke of a sense of helplessness and uncertainty at the time of the oil spill disaster not experienced before. One interviewee, retired, but an active volunteer at his local community center and church, spoke for his fellow Terrebonne Parish neighbors, saying, “it was in the back of everyone’s mind—am I going to be able to live the rest of our (sic) lives here?” (Resident interview, December 3, 2015). Technological disasters, such as the oil spill disaster, generate more uncertainty than other disasters, i.e., hurricanes (Baum et al., 1983). This is attributed to the seeming loss of control contrasted with a lack of control before, during, and after a hurricane (Palinkas, 2012). The unknowns surrounding the oil and dispersants’ short and long-term effects interwoven with the dramatic transformation of a cherished place affected its value as a source of solace.

Louisiana coastal communities face a “triple exposure” when overlaying technological hazards onto climate change and global economic uncertainties (Colten et al., 2015). Residents are largely unable to have a meaningful say about the ongoing transformations of the bayous and marshes occurring in and around their homes. This can lead to a breakdown of relationships between identities and the socio-environmental deterioration in and around their homes.

Climate Justice: “People are Here Who Don’t Have the Resources to Leave”

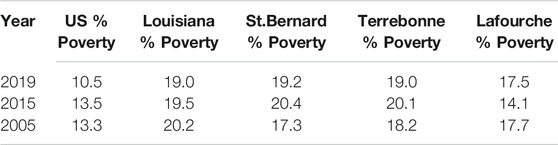

This research explores not only the decisions of those positioned to consider migration, but also those who are rendered immobile through underlying inequalities. Those most socially vulnerable to the challenges of living along Louisiana’s coast, particularly with current predictions of sea-level rise, are disproportionately socially disadvantaged Americans (Martinich et al., 2013). (Table 2). Many of these communities are beset by deep-rooted and longstanding conditions of political disempowerment and economic disenfranchisement, thereby creating loftier obstacles for adapting to socio-environmental changes (Piguet, 2011; Jurjonas and Seekamp, 2019; Siders, 2019), and a more limited range of adaptive options (Jurjonas et al., 2020). A former resident of Terrebonne Parish and current employee of a non-profit coastal advocacy group noted, “I think that some of the people still left (in lower Terrebonne) are the ones that really can’t leave, they don’t have the money, they have a boat in their backyard, those kinds of things” (resident interview July 11, 2014).

It is the impoverished and marginalized communities who have contributed the least to climate change. A recent Oxfam study found that over the last twenty-five years, the richest one percent of the global population contributed double the amount of carbon as the poorest fifty percent did (Berkhout et al., 2021). Yet, it is these populations that are disproportionately finding themselves in harm’s way, both though adverse landscape deterioration or mental health impacts (Hayes et al., 2018). Socioeconomically marginalized and communities of color are at higher risk of solastalgic feelings because the regions in which these populations live are typically more at risk to environmental degradation. Southeastern Louisiana lands, assets, cultures, and resources are severely threatened due to the contributing effects of climate change. The National Climate Assessment (2014) indicates that the Gulf Coast will undergo an increase in extreme and intense tropical cyclones, intensifying the risk of adverse effects from future coastal hazards.

Invariably, as these hazards increase, prompting tens of billions of dollars in damages and corresponding FEMA and insurance claims, these repeated claims will affect the tenuousness of residents’ place along the coast. As one resident of Lafourche said: “the geography of where you live, coupled with poor education is a major factor in terms of environmental justice. And high poverty makes the community vulnerable” (resident interview, February 22, 2012). Indeed, coastal Louisiana is a place in which numerous claims of socio-environmental injustices abound (Lynn et al., 2013; Bullard et al., 2016).

The structural barriers and complex bureaucracy of applying for and receiving post-disaster assistance from FEMA can hit poorer and more marginalized families the hardest (Browne et al., 2015). These cumbersome processes can create multi-scalar conflicts, including conflicts with oneself. As described by a Catholic priest in Houma, “it was difficult to go back and rely on others and have to just depend on other people when you’re used to being so self-sufficient. You have to humble yourself and reach out to people and this was really hard for people” (resident interview, July 23, 2015). Many other interviewees expressed frustration at maneuvering the formal recovery processes post-storm, and instead rely on the more informal community social support systems.

These circumstances further make the case that migration as adaptation must be more holistically integrated into climate risk adaptation policies and funding (Adger et al., 2018). Furthermore, more research is needed to understand the social and cultural components, including the resilient practices (Colten et al., 2015), intangible, cultural values (Henderson and Seekamp, 2018), and heritage preservation (Browne, et al., 2015) of marginalized residents who are adversely affected by climate change. These assessments must go beyond economic dimensions (e.g., economic assessment, cost-benefit analyses) (Ghahramani et al., 2020).

The “choice” of whether to migrate or stay put is not a decision that everyone is able to make. Lower Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes are in the “V” and “VE” flood zones—the most hazardous flood zones accompanied with the highest flood insurance premiums. Flood insurance, particularly for coastal areas, needs a substantial overhaul (Craig, 2019). Because many residents of these areas are low-income, they cannot afford the insurance premiums, post-disaster loans, or renting somewhere while the old house is fixed. The consequences are disparate impacts on marginalized communities (Jurjonas and Seekamp, 2019). As one resident of Houma, a lifelong public official whose home is in the AE flood zone grumbled, “my insurance has gone from $1,200 a year to $7,000 a year. It’s ridiculous. And there’s a lot of people here who are just going without flood insurance because they can’t afford it” (resident interview, July 17, 2015). In addition, selling a home in a hazardous flood zone that is not raised to an elevation to keep flood insurance rates reasonable can be difficult to impossible. A home cannot be sold or bought with a federally backed loan if the flood insurance will not transfer.

To address some of those disproportionate impacts and plan for intensifying climate change effects, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) awarded the state of Louisiana $92 million in January 2016 in a National Disaster Resilience Competition. The funded projects seek to holistically address community resilience by integrating risk planning with stormwater management, culture, economic development, housing and other key components of accounting for a changing place. There are ten resident-chosen Louisiana’s Strategic Adaptations for Future Environments (LA SAFE) projects which are ongoing and in varying stages of implementation. This grant also funds the Resettlement of Isle de Jean Charles, a low-lying coastal community at the nexus of migration and climate change.

The Resettlement of Isle de Jean Charles: “Not a Simplistic Move”

HUD awarded $48.3 million to the State of Louisiana’s Office of Community Development to plan a scalable and economically viable community resettlement with former and current Isle de Jean Charles residents. Following decades of contending with the effects of land, community and livelihood losses, Island residents will be relocating largely together as a collective group in 2021-2022. For many, they are leaving the only home they have ever known. The Islands’ residents are almost all indigenous and interrelated descendants of tribes seeking refuge from persecution more than a century ago. They have made the Island in Terrebonne Parish their home for multiple generations and embody a strong sense of place and attachment to it. An elder resident recalled that at “at one time, I couldn’t see marshes on the other side because there were so many trees. People would use old time, home remedies.” He pauses. “No more.” (resident interview, August 17, 2012). Islanders could grow a majority of their food and had daily family visits. Imbued throughout their stories are feelings of unease for the future of the Island and distress of losing their home. Cognizance of the impending hazards and current risks presents challenges to emotional and social wellbeing (Fritze et al., 2008) and can cause feelings of displacement and solastalgia despite being in the same place one has lived for decades.

It is critical to recognize that the socially constructed vulnerabilities to frequent flooding and other coastal hazards are linked to colonial histories (Marino, 2012; Whyte, 2013). The processes of social and ecological marginalization play a significant role in the vulnerabilities to these risks for former and current residents (Jessee, 2020). In order to avoid replicating those inequities when it comes to the adverse effects of climate change, residents and the state are working together to facilitate a structured and voluntary retreat (Office of Community Development, State of Louisiana, 2019). The ultimate outcome of this process and the degree to which it is equitable remains to be seen and may take years, even a generation or two, to establish.2.

During the ruthless hurricane season of 2020, nearly all Island residents evacuated seven different times, with Hurricane Zeta bringing 100 MPH winds on October 4 and wreaking havoc on Island homes. In 2019, Hurricane Barry brought eight feet of water onto the Island and Coast Guard helicopters rescued residents and a dog who had not evacuated. Residents on the protected side of the Morganza Hurricane Protection System did not see flooding as high as the Island. As one resident says, “climate change for me is the title for land loss. My landscape has changed and because that landscape has changed, that’s what brought me down to this decision (to relocate)” (informal conversation, May 14, 2020). As Islanders describe how there was once land as far as the eye could see and they were once surrounded by relatives on all sides, feelings of solastalgia are now an integral element of living where they do (Muller, 2020).

One Island resident, weighing the resettlement decision, identifies the complexities inherent in decision-making, explaining “in the process, you know, this is not a simplistic move. This is not just about getting grant money, and then moving. So, in that process right there, I’m going through it, I’m going through a thinking process, too and I’m moving along with it. Now, I’m not so moved by what’s going on around me on the outside; I’m moved by what’s going on with me on the inside” (resident interview, February 27, 2018). Many Island residents are in the process of assessing and re-assessing their decision to move while navigating the inherent cultural, social, environmental, economic, institutional and political complexities. Despite the differing circumstances from other residents on the coast, the process still presents myriad challenges.

As of the time of this writing, the infrastructure of the resettlement site, which residents named “The New Isle,” is under construction. Weather permitting, homes will be completed in 2021-2022. 38 of 42 remaining Island families have chosen to move off the Island — 37 will relocate to The New Isle in the northern part of Terrebonne Parish. One family will relocate apart from the community, but elsewhere outside of the Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA).

By establishing a proactive climate-based relocation framework, the resettlement of Isle de Jean Charles can assist communities facing similar challenges (Davenport and Roberston, 2016). To date, there is not yet a U.S. government agency, official procedure or funding stream dedicated to confronting climate-linked community resettlements in the United States and it is hoped that this resettlement program can reveal the need for building these tools and frameworks (GAO-20–488, 2020).

Conclusion

Putting the voices of residents first, such as in this research, can serve as a conceptual tool for future environmental migration work. Many participants spoke of either themselves or others whose culture and livelihood is contingent on the health and vivacity of the surrounding land and water. Residents spoke of their abilities to adapt when talking about the adversities they encountered, while at the same time questioning how much adaptation their communities can endure before becoming maladaptive. A greater understanding of what people view as effective and feasible adaptation strategies for facing future climate changes can increase policy approaches and resources in the future. Illuminating local perspectives can highlight decisions that occur at the nexus of migration, climate change and solastalgia.

Decisions to migrate or not, if that is a choice, involve foregoing insurance, waiting for levee protection or marsh restoration completion, rebuilding the family home after a storm, and contending with distressing feelings arising from watching familiar places bleed into the unfamiliar and unrecognizable. The conclusions of migration for which residents must eventually arrive, whether to remain or go, are, for many, steeped in solastalgic understandings of their homes. For many there is a sense of hopelessness, a yearning for what once was, particularly for elder residents who expressed that so much of the landscape has changed for them.

The compounding changes taking place around them are affecting the residents themselves, and these are not discretely separate, but, rather, are interconnected processes. Many residents’ experiences of living in a cherished place adversely affected by climate change is a key signifier of solastalgia. This empirically grounded research elucidates some of the ways in which residents evaluate the benefits and hazards of living where they do and how it relates to climate change, migration and their social and emotional wellbeing.

This research examined place-specific and culturally subjective relocation possibilities, yet, the experiential knowledge has the potential to inform policies and practices of climate-driven migratory decision-making on a broader scale. Asking questions of the social relations, the socio-economic conditions, cultural constraints or traditions, and the context in which these occur offers insight into the push and pull many residents feel in their decision-making processes. Many coastal residents are tied to the landscape by feelings of solastalgia and view relocation as the last option. This feeling, intimately tied to sense of place, follows the general trend of wanting to stay where one feels most at home, despite the dramatic socio-environmental changes or being “on the front lines of climate change.” As we develop policies and practices to facilitate and support more formal processes of relocation, policy makers and planners need to account for and work toward a greater understanding of the complexity and salience of solastalgia.

Data Availability Statement

The data is not publicly available because it contains information that could compromise research participant privacy/consent.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Louisiana State University—Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily reflect the official views of funders or author’s employer.

Funding

This research was funded in part by Award Number U19ES020676 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and by the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology at the University of Arizona under a Bureau of Ocean Energy Management cooperative agreement.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1Ten years ago was 2005, the year Hurricanes Katrina and Rita caused widespread damage across the Gulf Coast.

2For more on the Resettlement of Isle de Jean Charles

References

Adams, V., Van Hattum, T., and English, D. (2009). Chronic Disaster Syndrome: Displacement, Disaster Capitalism, and the Eviction of the Poor from New Orleans. Am. Ethnol. 36 (4), 615–636. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2009.01199.x

Adger, W. N., Arnell, N. W., Black, R., Dercon, S., Geddes, A., and Thomas, D. S. (2015). Focus on Environmental Risks and Migration: Causes and Consequences. Environ. Res. Lett. 10 (6), 060201. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/6/060201

Adger, W. N., de Campos, R. S., Mortreux, C., McLeman, R., and Gemenne, F. (2018). “Mobility, Displacement and Migration, and Their Interactions with Vulnerability and Adaptation to Environmental Risks,” in Routledge Handbook of Environmental Displacement and Migration, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. 29–41. doi:10.4324/9781315638843-3

Airriess, C. A., Li, W., Leong, K. J., Chen, A. C.-C., and Keith, V. M. (2008). Church-based Social Capital, Networks and Geographical Scale: Katrina Evacuation, Relocation, and Recovery in a New Orleans Vietnamese American Community. Geoforum 39 (3), 1333–1346. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.11.003

Albrecht, G. (2005). 'Solastalgia'. A New Concept in Health and Identity. PAN: Philos. Activism Nat. 3, 41–55.

Albrecht, G., Sartore, G. M., Connor, L., Higginbotham, N., Freeman, S., Kelly, B., et al. (2007). Solastalgia: the Distress Caused by Environmental Change. Australas. Psychiatry 15 (Suppl. 1), S95–S98. doi:10.1080/10398560701701288

Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-disaster Recovery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226012896.001.0001

Askland, H. H., and Bunn, M. (2018). Lived Experiences of Environmental Change: Solastalgia, Power and Place. Emot. Space Soc. 27, 16–22. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2018.02.003

Austin, D. E. (2006). Coastal Exploitation, Land Loss, and Hurricanes: a Recipe for Disaster. Am. Anthropologist 108 (4), 671–691. doi:10.1525/aa.2006.108.4.671

Barrios, R. E. (2014). 'Here, I'm Not at Ease': Anthropological Perspectives on Community Resilience. Disasters 38 (2), 329–350. doi:10.1111/disa.12044

Baum, A., Fleming, R., and Singer, J. E. (1983). Coping with Victimization by Technological Disaster. J. Soc. Issues 39 (2), 117–138. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1983.tb00144.x

Berkhout, E., Galasso, N., Lawson, M., Morales, R., Rivero., P. A., Taneja, A., et al. (2021). The Inequality Virus: Bringing Together a World Torn Apart by Coronavirus through a Fair, Just and Sustainable Economy. Oxford, UK: Oxfam International.

Black, R., Kniveton, D., and Schmidt-Verkerk, K. (2011). Migration and Climate Change: Towards an Integrated Assessment of Sensitivity. Environ. Plan. A. 43 (2), 431–450. doi:10.1068/a43154

Boccagni, P., and Baldassar, L. (2015). Emotions on the Move: Mapping the Emergent Field of Emotion and Migration. Emot. Space Soc. 16, 73–80. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2015.06.009

Bodin, Ö., and Crona, B. I. (2009). The Role of Social Networks in Natural Resource Governance: What Relational Patterns Make a Difference? Glob. Environ. Change 19 (3), 366–374. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.05.002

Bronen, R., and Chapin, F. S. (2013). Adaptive Governance and Institutional Strategies for Climate-Induced Community Relocations in Alaska. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110 (23), 9320–9325. doi:10.1073/pnas.1210508110

Brown, D. L. (2002). Migration and Community: Social Networks in a Multilevel World. Rural Sociol. 67 (1), 1–23.

Browne, K. (2015). Standing in the Need: Culture, Comfort, and Coming Home after Katrina. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

Bullard, D. R., Gardezi, D., Chennault, M., and Dankbar, C. (2016). Climate Change and Environmental Justice: A Conversation with Dr. Robert Bullard. J. Crit. Thought Praxis 5 (2), 3. doi:10.31274/jctp-180810-61

Burkett, M. (2016). Justice and Contemporary Climate Relocation: An Addendum to Words of Caution on “Climate Refugees.”. NewSecurityBeat. Retrieved from .https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2016/08/justice-contemporary-climate-relocation-addendum-words-caution-climate-refugees/doi:10.4324/9780203093474.ch40

Burley, D. M. (2010). Losing Ground: Identity and Land Loss in Coastal Louisiana Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Cardona, F. S., Ferreira, J. C., and Lopes, A. M. (2020). Cost and Benefit Analysis of Climate Change Adaptation Strategies in Coastal Areas at Risk. J. Coastal Res. 95 (sp1), 764–768. doi:10.2112/si95-149.1

Castles, S. (2003). Towards a Sociology of Forced Migration and Social Transformation. Sociology 37 (1), 13–34. doi:10.1177/0038038503037001384

Castles, S., de Haas, H., and Miller, M. J. (2014). “The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. Basingstoke, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan Higher Education.

Chamlee-Wright, E. (2010). The Cultural and Political Economy of Recovery: Social Learning in a Post-disaster Environment. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203855928

Cheng, L.-J. (2009). Relationships between Economics, Welfare, Social Network Factors, and Net Migration in the United States. Int. Migration 47 (4), 157–185. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00546.x

Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana (CPRA) (2017). Draft Louisiana’s Comprehensive Master Plan for a Sustainable Coast. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana.

Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana (CPRA) (2012). Louisiana’s Comprehensive Master Plan for a Sustainable Coast. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana.

Colten, C. E. (2017). Environmental Management in Coastal Louisiana: A Historical Review. J. Coastal Res. 33 (3), 699–711. doi:10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-16-00008.1

Colten, C. E., Grismore, A. A., and Simms, J. R. Z. (2015). Oil Spills and Community Resilience: Uneven Impacts and Protection in Historical Perspective. Geographical Rev. 105 (4), 391–407. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2015.12085.x

Colten, C. E., Hay, J., and Giancarlo, A. (2012). Community Resilience and Oil Spills in Coastal Louisiana. Ecol. Soc. 17 (3), 5. doi:10.5751/es-05047-170305

Cope, M. R., Slack, T., Blanchard, T. C., and Lee, M. R. (2013). Does Time Heal All Wounds? Community Attachment, Natural Resource Employment, and Health Impacts in the Wake of the BP Deepwater Horizon Disaster. Soc. Sci. Res. 42 (3), 872–881. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.12.011

Craig, R. K. (2019). Coastal Adaptation, Government-Subsidized Insurance, and Perverse Incentives to Stay. Climatic Change 152, 215–226. doi:10.1007/s10584-018-2203-5

Cunsolo, A., and Ellis, N. R. (2018). Ecological Grief as a Mental Health Response to Climate Change-Related Loss. Nat. Clim Change 8 (4), 275–281. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2

Curran, S. R., and Saguy, A. C. (2013). Migration and Cultural Change: a Role for Gender and Social Networks? J. Int. Women's Stud. 2 (3), 54–77.

Dalbom, C., Hemmerling, S. A., and Lewis, J. A. (2014). Community Resettlement Prospects in Southeast Louisiana: A Multidisciplinary Exploration of Legal, Cultural, and Demographic Aspects of Moving Individuals and Communities. New Orleans, LA: Tulane University.

Dandy, J., Horwitz, P., Campbell, R., Drake, D., and Leviston, Z. (2019). Leaving Home: Place Attachment and Decisions to Move in the Face of Environmental Change. Reg. Environ. Change 19 (2), 615–620. doi:10.1007/s10113-019-01463-1

Davenport, C., and Robertson, C. (2016). Resettling the First American Climate Refugees. New York: New York Times, 3.

DeLyser, D., and Sui, D. (2013). Crossing the Qualitative- Quantitative Divide II. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 37 (2), 293–305. doi:10.1177/0309132512444063

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Entering the Field of Qualitative Research. in Handbook of Qualitative Research. Editors N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 1–17.

Dolan, A. H., and Walker, I. J. (2006). Understanding Vulnerability of Coastal Communities to Climate Change Related Risks. J. Coastal Res. 3(39), 1316–1323.

Dun, O. (2011). Migration and Displacement Triggered by Floods in the Mekong Delta. Int. Migration 49 (s1), e200–e223. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00646.x

Dunn, K. (2005). ‘Doing’ Qualitative Research in Human Geography. in Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography. Editor I. Hay (Oxford, UK: Oxford University), 50–82.

Eisenman, D., McCaffrey, S., Donatello, I., and Marshal, G. (2015). An Ecosystems and Vulnerable Populations Perspective on Solastalgia and Psychological Distress after a Wildfire. EcoHealth 12 (4), 602–610. doi:10.1007/s10393-015-1052-1

Flavelle, C. (2016). The Areas America Could Abandon First New York: Bloomberg ViewRetrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2016-11-29/the-areas-america-could-abandon-first.

Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P., and Norberg, J. (2005). Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 30, 441–473. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511

Fritze, J. G., Blashki, G. A., Burke, S., and Wiseman, J. (2008). Hope, Despair and Transformation: Climate Change and the Promotion of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2 (1), 13. doi:10.1186/1752-4458-2-13

GAO-20–488 (2020). Climate Change: A Climate Migration Pilot Program Could Enhance the Nation’s Resilience and Reduce Federal Fiscal Exposure. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Ghahramani, L., McArdle, K., and Fatorić, S. (2020). Minority Community Resilience and Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Case Study of the Gullah Geechee Community. Sustainability 12 (6), 2266. doi:10.3390/su12062266

Greiner, C., and Sakdapolrak, P. (2016). “Migration, Environment and Inequality: Perspectives of a Political Ecology of Translocal Relations,” in Environmental Migration and Social Inequality. Editors J. Schade, R. McLeman, and T. Faist (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 151–163. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25796-9_10

Hauer, M. E., Hardy, R. D., Mishra, D. R., and Pippin, J. S. (2019). No Landward Movement: Examining 80 Years of Population Migration and Shoreline Change in Louisiana. Popul. Environ. 40 (4), 369–387. doi:10.1007/s11111-019-00315-8

Hayes, K., Blashki, G., Wiseman, J., Burke, S., and Reifels, L. (2018). Climate Change and Mental Health: Risks, Impacts and Priority Actions. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 12, 28. doi:10.1186/s13033-018-0210-6

Hedberg, C., and do Carmo, R. M. (2012). “Translocal Ruralism: Mobility and Connectivity in European Rural Spaces,” in Translocal Ruralism. Editors C. Hedberg, and R. Miguel do Carmo (Netherlands: Springer), 1–9. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2315-3_1

Henderson, M., and Seekamp, E. (2018). Battling the Tides of Climate Change: The Power of Intangible Cultural Resource Values to Bind Place Meanings in Vulnerable Historic Districts. Heritage 1 (2), 220–238. doi:10.3390/heritage1020015

Hess, J. J., Malilay, J. N., and Parkinson, A. J. (2008). Climate Change. Am. J. Prev. Med. 35 (5), 468–478. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.024

Horowitz, A. (2014). The BP Oil Spill and the End of Empire, Louisiana. South. Cultures 20 (3), 6–23. doi:10.1353/scu.2014.0026

Hugo, G. (2008). Migration, Development and Environment. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. doi:10.18356/7722fb75-en

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014). Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IPCC (2019). Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/chapter-4-sea-level-rise-and-implications-for-low-lying-Islands-coasts-and-communities/.

Jenkins, P. (2016). A Sense of Place at Risk: Perspectives of Residents of Coastal Louisiana on Nonstructural Risk Reduction Strategies. Oxfam America. Boston, MA: Oxfam.

Jessee, N. (2020). “Community Resettlement in Louisiana: Learning from Histories of Horror and Hope,” in Louisiana's Response To Extreme Weather (Springer, Cham. Journal of Social Issues), 39, 117–138.

Jurjonas, M., and Seekamp, E. (2019). ‘A Commons before the Sea:’ Climate Justice Considerations for Coastal Zone Management. Clim. Dev 27 (5), 629–648. doi:10.1080/17565529.2019.1611533

Jurjonas, M., Seekamp, E., Rivers, L., and Cutts, B. (2020). Uncovering Climate (In)justice with an Adaptive Capacity Assessment: A Multiple Case Study in Rural Coastal North Carolina. Land Use Policy 94, 104547. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104547

Kelman, I., Upadhyay, H., Simonelli, A. C., Arnall, A., Mohan, D., Lingaraj, G. J., et al. (2017). Here and Now: Perceptions of Indian Ocean Islanders on the Climate Change and Migration Nexus. Geografiska Annaler: Ser. B, Hum. Geogr. 99 (3), 284–303. doi:10.1080/04353684.2017.1353888

Klinenberg, E. (2016). Climate Change: Adaptation, Mitigation, and Critical Infrastructures. Public Cult. 28 (279), 187–192. doi:10.1215/08992363-3427415

Lewicka, M. (2013). In Search of Roots: Memory as Enabler of Place Attachment. in Place Attachment: Advances In Theory, Methods and Applications. Editors L. C. Manzo, and P. Devine-Wright (New York: Routledge), 49–60.

Louisiana Recovery Authority (2006). Migration Patterns: Estimates of Parish Level Migrations Due to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Louisiana Health and Population Survey. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals.

Lynn, K., Daigle, J., Hoffman, J., Lake, F., Michelle, N., Ranco, D., et al. (2013). The Impacts of Climate Change on Tribal Traditional Foods. Climatic Change 120 (3), 545–556. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0736-1

Marino, E. (2018). Adaptation Privilege and Voluntary Buyouts: Perspectives on Ethnocentrism in Sea Level Rise Relocation and Retreat Policies in the US. Glob. Environ. Change 49, 10–13. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.01.002

Marino, E. (2012). The Long History of Environmental Migration: Assessing Vulnerability Construction and Obstacles to Successful Relocation in Shishmaref, Alaska. Glob. Environ. Change 22 (2), 374–381. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.09.016

Marks, B. (2012). The Political Economy of Household Commodity Production in the Louisiana Shrimp Fishery. J. Agrarian Change 12 (2-3), 227–251. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2011.00353.x

Marshall, B. (2013). Louisiana Coast Faces Highest Rate of Sea-Level Rise Worldwide. The Lens. Retrieved from https://thelensnola.org/2013/02/21/new-research-louisiana-coast-faces-highest-rate-of-sea-level-rise-on-the-planet/.

Martinich, J., Neumann, J., Ludwig, L., and Jantarasami, L. (2013). Risks of Sea Level Rise to Disadvantaged Communities in the United States. Mitig Adapt Strateg. Glob. Change 18 (2), 169–185. doi:10.1007/s11027-011-9356-0

Massey, D. (1991). The Political Place of Locality Studies. Environ. Plan. A. 23 (2), 267–281. doi:10.1068/a230267

Mayer, B. (2019). A Review of the Literature on Community Resilience and Disaster Recovery. Curr. Envir Health Rpt 6, 167–173. doi:10.1007/s40572-019-00239-3

McHugh, K. E. (2000). Inside, outside, Upside Down, Backward, Forward, Round and Round: A Case for Ethnographic Studies in Migration. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 24 (1), 71–89. doi:10.1191/030913200674985472

McMichael, A. (2017). Climate Change and the Health of Nations: Famines, Fevers, and the Fate of Populations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190262952.001.0001

McNamara, K. E., and Westoby, R. (2011). Solastalgia and the Gendered Nature of Climate Change: An Example from Erub Island, Torres Strait. EcoHealth 8 (2), 233–236. doi:10.1007/s10393-011-0698-6

Mendoza, C., and Morén-Alegret, R. (2013). Exploring Methods and Techniques for the Analysis of Senses of Place and Migration. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 37 (6), 762–785. doi:10.1177/0309132512473867