- 1Department of Environmental Science, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana

- 2Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing, Health Sciences Addition, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

- 3Biological, Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences, School of Public Health University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana

- 4Council for Scientific and Industrial Research-Water Research Institute, Accra, Ghana

- 5Department of Geography, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

The relationships between environmental exposure and health outcomes are complex, multidirectional, and dynamic. Therefore, it is required to have an understanding of these linkages for effective health risk communication. Artisanal gold mining is widespread globally, in spite of its associated health hazards, with an estimated 30 million people engaged in it. In this study, the relationships between artisanal gold miners knowledge of environmental and health effects of mercury (Hg) and compositional, contextual and occupational factors were assessed using generalized linear models (GLM) (negative log-log regression). A cross-sectional survey in three urban gold mining hubs in Ghana (Prestea, Tarkwa and Damang), was carried out among 588 (482 male and 106 female) artisanal gold miners. The results showed that 89% of artisanal gold miners had very low to low levels of knowledge whereas 11% had moderate to very high levels of knowledge of deleterious health effects of Hg. Also, individuals who perceived their health-related working conditions to be excellent had very low to low levels of knowledge of environmental and health effects of Hg. Interestingly, artisanal gold miners who were still working were less likely to know the environmental and health effects of Hg compared with their counterparts who were currently unemployed. Similarly, artisanal gold miners who had attained either primary or secondary education were less likely to know the environmental and health effects of Hg compared with their counterparts who had no formal education. This finding, although counterintuitive, can be understood within the context that artisanal gold miners in Ghana without formal education tend to have considerably higher number of years of practical experience compared with their counterparts with formal education. Based on odds ratios (OR), female artisanal gold miners were 68% less likely to know the environmental and health effects of Hg compared with their male counterparts (OR = 0.32, p < 0.05). Artisanal gold miners who had previously encountered occupational health problems were significantly far more likely to know the environmental and health effects of Hg compared with their counterparts without any previous occupational health problems (OR = 4.86, p < 0.0001). Although artisanal gold miners who are 25–34 years old were more likely to know than their counterparts who are 18–24 years old, there were no differences in knowledge between those who are 35 years or older and their counterparts who are 18–24 years old. These results emphasize the complex relationships between compositional, contextual and occupational factors on the one hand, and artisanal gold miners' knowledge of environmental and health effects of Hg, on the other hand. Some policy implications of the findings suggest that a more systematic approach to the development and evaluation of interventions to phase out Hg use in artisanal gold mining is desirable, with clearer recognition of the interrelationships between compositional factors of artisanal gold miners and their persistent reliance on Hg in the gold extraction process.

Introduction

Millions of people in developing countries are involved with artisanal gold mining, accounting for approximately 20–30% of the world supply at 500–800 tons/year (Telmer and Veiga, 2009; Spiegel and Veiga, 2010). Artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASM) is a poverty-driven activity that provides an important source of livelihood for many rural communities (Hilson, 2013; Hilson et al., 2014; Armah et al., 2016). It is therefore unsurprising that this phenomenon is thriving in sub-Saharan Africa (Hilson, 2013) where poverty is rife. The economic impacts of gold mining operations are inextricably linked to its social and environmental impacts. Many social problems are direct consequences of poverty, and if gold mining helps a community become prosperous, it may also help it tackle social ills such as malnutrition, illiteracy, and poor health. On the other hand, mining activities may cause pollution in rivers and damage fish stocks, for instance, or by appropriating grazing land and forestry resources resulting in further economic hardship. This, in turn, may exacerbate existing socio-environmental and health problems or create new ones. For instance, as the price of gold has been increasing, the number of artisanal gold miners has risen to between 10 and 15 million people worldwide, producing from 500 to 800 tons of gold and emitting as much as 800–1000 tons of mercury (Hg) annually (Veiga and Baker, 2004; Swenson et al., 2011).

The World Health (World Health Organization (WHO), 2003) places the limit of public exposure at 1000 ng/m3 (annual average) and the recommended health-based exposure limit for metallic Hg is 20,000 ng/m3 (this value is an average exposure over a normal 8 h day and 40 h work week, the limit would be lower for workers who observe longer hours). A plethora of health effects of mercury exposure to humans are well-documented in the literature. At present, these are understood to be neurological, renal, cardiovascular and immunological impacts. Chronic exposure to mercury can cause damage to the brain, spinal cord, kidneys, and liver (Bose-O'Reilly et al., 2010a; Cordy et al., 2011). Mercury is a potent neurotoxin, and airborne emissions pose significant health and environmental concerns (Obiri et al., 2010). Studies show that exposure to mercury during pregnancy can lead to neurodevelopmental problems in unborn babies and young children (Bernhoft, 2011). Mercury exposure or poisoning can harm the major organs such the brain, heart, kidneys and lungs and young children may develop impairment of peripheral vision, and disturbance in sensations including the ability to feel, see, move and taste, and can cause numbness. Long-term exposure can lead to progressively worse symptoms and ultimately personality changes, stupor, and in extreme cases, coma, or death (Bernhoft, 2011). Recent findings have described adverse cardiovascular and immune system effects at very low levels (Karagas et al., 2012). Nevertheless, the health of artisanal miners is obviously at risk, and residents in nearby communities can also suffer symptoms of chronic mercurialism when vapor and mercury laden dust enter and deposit in their homes (Swain et al., 2007; Schwarzenbach et al., 2010). Mercury in any form is poisonous, and the severity of mercury's toxic effects depends on the form and concentration of mercury and the route of exposure. Exposure to elemental mercury can result in effects on the nervous system, including tremor, memory loss and headaches (Bernhoft, 2011; Armah et al., 2012). Other symptoms include bronchitis, fatigue, weight loss, gastro-intestinal problems, thyroid enlargement, gingivitis, excitability, unstable pulse, and toxicity to the kidneys (Bernhoft, 2011; Houston, 2011).

Artisanal gold mining using mercury nearly disappeared in the mid-twentieth century, displaced by more efficient large-scale mining operations that use cyanide. However, the rise in gold prices, coupled with political and socio-economic instability in some areas in the 1970s, made gold mining appealing again to poor operators who could not afford more modern technology (Wilson et al., 2015). This past decade's boom in gold prices piqued the interest of both artisanal and industrial mining operations. However, the slump in prices over the past year has caused some mining companies to scale back their ambitions, while the more nimble artisanal miners, with their lower overhead and ease of evading environmental and labor laws, continue to thrive (Armah et al., 2013b; Sieber and Brain, 2014). Notwithstanding the well documented adverse health effects of mercury, artisanal gold mining, as an occupation, continues to rely, almost exclusively, on the use of mercury in gold extraction despite safer alternative technologies and the elimination of mercury use by large-scale mining operations. In fact, artisanal gold mining is the largest single source of atmospheric mercury, accounting for 37 percent of annual emissions. It is argued that the use of mercury in artisanal gold mining is persistent because miners often are not aware of the risks involved in using mercury, and/or they may not have a choice in the matter (Telmer and Stapper, 2012). Artisanal miners will continue to use mercury so far as they perceive that the benefits of this technique outweigh the costs. In order to shift attitudes and raise awareness of the dangers and risks associated with mercury use, miners must be made aware of the potential health consequences from mercury and introduced to new techniques that minimize the amount of mercury used or replace mercury amalgamation with safer alternatives (Eisler, 2003; Sieber and Brain, 2014; Veiga et al., 2014). Yet, studies on how population composition and contextual factors influence the knowledge of artisanal miners on health effects associated with mercury exposure are rather limited. This is a fundamental motivation for this study. Even those artisanal miners who are aware often cannot afford or lack access to safer alternatives. According to Sieber and Brain (2014), mercury remains relatively cheap and readily available. No special equipment is needed for its use in amalgamation, so it is easy for miners to move from one location to another and seek out richer deposits or evade arrest for this illegal activity (Armah et al., 2013a).

Using Ghana as a case study, this study assessed the knowledge of artisanal mine workers on the health effects associated with mercury exposure. Ghana was chosen for three fundamental reasons. First, Ghana is the second largest African gold producer and the ninth largest globally. Artisanal miners contribute significant to this production (Wilson et al., 2015). Ghana accounts for over 3% of world gold production. This is noteworthy given that no single country produces more than about 14% of the world's gold, which shows that gold mining is a truly global industry. Gold overtook cocoa as Ghana's principal export in 1991 and the IMF estimates that by 2014, gold mining will contribute around $3.8bn to Ghana's balance of payments. In 2010, tax collected from the mining sector by the Ghanaian Revenue Authority totaled $170 million, 24% of all company tax collected (Oxford Business Group, 2013). Second, the number of artisanal gold miners in Ghana, particularly the Chinese, has increased dramatically since the mid-1990s in defiance of government regulatory mechanisms (Armah et al., 2013b). The total number of artisanal gold miners is estimated at 180,000–200,000 (see Buxton, 2013). Third, a substantial body of literature has been devoted to artisanal gold mining in Ghana (see Armah et al., 2010; Armah and Gyeabour, 2013; Hilson, 2013; Hilson et al., 2014; Macdonald et al., 2014; Calys-Tagoe et al., 2015). Yet, there is currently too little quantitative information on the relationship between artisanal goldminers evaluation of mercury-induced health effects and compositional attributes (biosocial and sociocultural) and contextual factors. In response to this knowledge gap, two research questions were formulated to guide the study. First, how do population composition and contextual factors influence artisanal gold miners knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure? How is the relationship between artisanal miners' knowledge of health effects and these factors modified when environmental, health, safety, and economic conditions within the occupational setting are taken into account?

Theoretical Context

The existing evidence concerning the relationship between knowledge of health effects of mercury intoxication and compositional, contextual, and occupational factors is relatively limited, as the research has mainly focused broadly on the links between water and Hg-related environmental pollution, or biota, with a fewer number of studies focusing on alternative technologies and on mercury pollution in particular (see Jønsson et al., 2013). The evidence available, covering a number of sub-Saharan African countries, generally shows significant associations between artisanal gold mining and pollution of environmental media and biota (see Nweke and Sanders, 2009; Shandro et al., 2009; Bose-O'Reilly et al., 2010b; Spiegel and Veiga, 2010). However, only few studies have investigated the independent effects of compositional, contextual, and occupational factors on knowledge of artisanal goldminers regarding mercury use, and these studies have reported mixed results (see Charles et al., 2013).

In the international policy discourse on sustainable production of gold, education is acknowledged to be a powerful tool in changing unsustainable patterns of production (e.g., the use of mercury in gold extraction). Yet, it is known that the relationship between knowledge and action is not linear and that knowledge does not always translate into action (knowledge-action gap). In the artisanal gold mining sector, Buxton (2013) has underscored this gap and the need to bridge it in order to offer sustainable livelihoods for poor and small-scale gold producers in developing countries. People who take risks are not necessarily less knowledgeable than those who do not take risks as, typically, those who know more tend to judge the risk to be smaller (Johnson, 1993). Perceived risk and knowledge are correlated although the strength of the association is quite modest in size, suggesting that the variance in the perception of risk cannot be explained by variation in knowledge.

Health risk assessments in occupational settings often give little consideration to the differences in how individuals assess exposure, probability, consequence, and overall risk. Research related to occupational health and safety generally focuses on the management of worker safety with limited concern for the subjective interpretation of safety risks and effects. Furthermore, little is known about how compositional contextual and occupational settings jointly influence knowledge of Hg-related health risks. The identification of levels of risk is predicated on both objective and subjective evaluation of probability and consequence. Therefore, it is expected that even among artisanal gold miners there will be heterogeneities in perceptions especially with regard to the probability and consequence of events. Individual perception of risk is not entirely reliant on the physical environment. Slovic (2000) notes that people imagine risk as a result of what they believe to be the likely outcome, the chance of the outcome actually occurring and how concerned they are if it does happen. In this context, several covariates underpin how artisanal gold miners view the work environment, the tasks to be done as well as the health risks associated with those tasks. According to Spurgeon et al. (1996), intrinsic attributes, such as experience, memory, and stress, along with extrinsic attributes, such as exposure and sensory information, and the work environment, combine to influence their perception and the decisions they make. The foregoing underscores the fact that health risk perception is socially constructed. The constructivist notion of risk perception suggests that risks are not entirely determined by prevailing environmental reality. They are expressed at both individual and societal levels in multifaceted settings (Kasperson and Kasperson, 1996; Jasanoff, 1999), not necessarily including science (Davis, 2005). Sjoberg has also demonstrated that covariates including the gravity of consequences and the perceivers (e.g., artisanal gold miners) stake in the risk were likewise vital determinants of the ensuing scope of demand for mitigation of a particular risk (see Sjoberg, 1999). Therefore, assessing the complex social, psychological, political, economic, and cultural factors influencing public perception of risk is critical for managing health risk effectively. Beyond this, it has been demonstrated that public acceptance of risk is predicated on perceived economic benefits associated with the activity (Slovic et al., 2005). Issues emanating from the dichotomy of socio-economic benefits and environmental risks are particularly serious in rural communities, which have isolated and highly limited economic development pathways. It is in this context that this paper must be understood.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted as part of the natural resource and environmental governance (NREG) initiative in Ghana from January to September 2011. Mining in Ghana has been characterized by divergent interests, cultures and institutions, lack of clarity over legal compensation and the distribution of benefits, conflict and a lack of trust between communities, industry and Government, as well as tensions between local communities and migrants (Armah et al., 2014). Moreover, large-scale mining operations often cause involuntary resettlement, resulting in loss of land, livelihoods and resources for local communities. Another area of concern has been the environmental damage resulting from mining activities, especially unregulated artisanal gold mining. Conscious of these challenges, the government of Ghana and its development partners identified establishment of a modern policy and regulatory framework, the improvement of mining sector revenue collection, management, and transparency and the tackling of social issues in mining communities as critical areas for reform under NREG.

Study Area

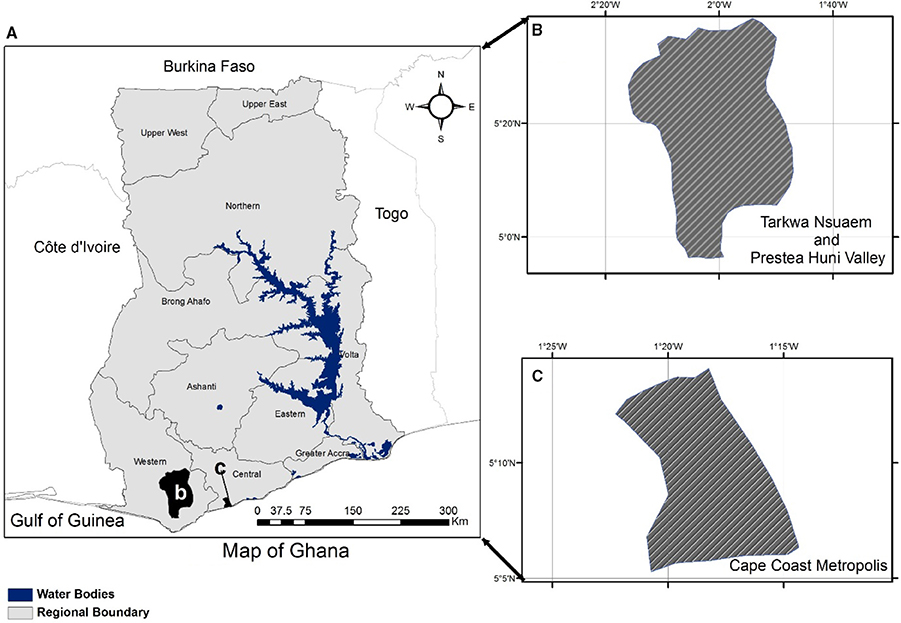

The study was undertaken in the Tarkwa Nsuaem and Prestea Huni Valley Districts in the Southwestern part of Ghana as shown in Figure 1. In this area, artisanal goldmining is extensive and three of the largest surface mine concessions in Ghana that is Bogoso–Prestea, Tarkwa, and Damang are sited here (Armah et al., 2016). According to Kuma and Younger (2004), the study location forms part of an important gold belt of Ghana, which originates from Konongo to the northeast through Tarkwa to Axim in the southwest. It is therefore unsurprising that mining is the main industrial activity in the area. Inhabitants of Tarkwa and its environs have a long history of alluvial mining, locally referred to as galamsey. A snapshot of the geological setting and mineralization suggests the Tarkwa ore bodies are part of the Tarkwaian System, which forms a significant portion of the stratigraphy of the Ashanti Belt in southwest Ghana (Leube et al., 1990; Milési et al., 1991; Dzigbodi-Adjimah, 1993). It has also been suggested that the north-easterly segment is broadly a synclinal structure constituted by Lower Proterozoic sediments and volcanics beneath which lies the metavolcanics and metasediments of the Birimian System (Leube et al., 1990; Milési et al., 1991; Dzigbodi-Adjimah, 1993). Zones of intense shearing are defining characteristics of the junction of the Birimian and Tarkwaian systems and embodies a number of significant shear-hosted gold deposits. It is argued that the Tarkwaian system overlies the Birimian in an uncomfortable manner and is characterized by lower intensity metamorphism and the predominance of coarse-grained, immature sedimentary units (Leube et al., 1990; Milési et al., 1991; Dzigbodi-Adjimah, 1993). The geology of the area makes it highly attractive for mining and several concessions have been granted to both large-scale and small-scale mining companies.

Figure 1. Map of the Tarkwa Nsuaem and Prestea Huni Valley Districts in Southwestern Ghana (source Armah et al., 2012).

Gold surface mining concessions are frequently granted for areas dominated by settlements and farmland, resulting in substantial conflicts between mining companies and local communities. Perhaps, the area has one of highest per capita of artisanal gold miners in Ghana and thus offers unique opportunities to better understand gold mining effects on local livelihoods and human health.

Two climatic regions characterize the Tarkwa Nsuaem and Prestea Huni Valley Districts. In this context, Dickson and Benneh (2004) suggest that the southern portion of the study area falls in the south western equatorial climatic region and the northern part has a wet semi-equatorial climate. The rainfall pattern generally follows the northward advance and the southward retreat of the inter-tropical convergence zone that separates dry air from the Sahara and moisture-monsoon air from the Atlantic Ocean (Dickson and Benneh, 2004). The area experiences two distinct rainy periods (double rainfall maxima). The first and larger peak occurs in June, whilst the second and smaller peak occurs in October. The mean annual precipitation is more than 1750 mm with approximately 54% of rainfall in the region occurring between March and July. The area is very humid and warm with temperatures between 26 and 30°C (Dickson and Benneh, 2004).

Data Collection

The data were obtained with the help of structured questionnaire. To assess the feasibility of the questionnaire, it was tested among 15 volunteers with a similar socioeconomic background as the study participants. The study was undertaken between January and August 2011. The ethical approval was obtained from the Ghana Health Service ethical review board. Before conducting the survey, we informed and discussed with the participants the nature of the research. Participation of respondents was voluntary. The pilot group was first asked to complete the questionnaire, to explain some of the questions to the investigators and to comment on comprehensibility; this led to minor modifications of the questionnaire to improve understanding. Based on the objectives of the study, the questionnaire was structured into four sections: socio-demographic, knowledge of health effects of mercury intoxication, and occupation-related quality measures. The demographic aspects include responses on the number of people engaged in the mining and ancillary activities, types of human habitats and proximity to the pitting sites, sex, age, marital status, ethnic origin, education, religion, income, and work shifts. This section also includes an assessment of social behavior of the artisanal gold mining community. The section on knowledge of health effects entails detailed description of the overall processes of gold production; focusing on the use of mercury in gold amalgamation, amount of mercury used and activities linked to artisanal gold production (mercury selling, gold trading, catering for miners, etc.). Occupation-related quality measures include artisanal miners' self-ratings on environmental, safety, health and economic conditions within the employment setting.

Artisanal gold miners who were 18 years or older at the time of survey and had continuously lived in the mining community for at least 1 year were eligible for recruitment and inclusion in the study. Potential participants were excluded if they have been absent from work in the past 1 year (to reduce recall bias), had been engaged in artisanal gold mining for less than 1 month or had shifted permanently from artisanal gold mining to another occupation (e.g., petty trading, large scale mining, etc.). Sampling for the study was systematic: all individuals meeting the inclusion criteria were approached. A general introduction to the study was given each morning by the researcher team. On meeting the research team and after screening for eligibility, individuals were taken through the study information sheet and informed consent process. Written consent was given for participation. A total of 603 participants were recruited however, 15 individuals (9 males and 6 females) declined participation. Reasons for non-participation included time constraints due to work schedule and domestic activities, personal disinterest and apathy due to unmet expectations of previous researchers. In the context of unmet expectations, it is pertinent to note that two issues came to the fore during the recruitment of participants. According to the artisanal gold miners who declined to participate in the study, some researchers promised that their research findings will inform government on the need for their inclusion in the formal economy. Several years thereafter, this has not happened. In fact, they contend that their plight has rather worsened warranting their decision to not participate in ongoing and future studies. Also, some of them indicated that, in the past, after they had granted interviews to researchers, government and security officials often invaded their mining sites the following week. The propinquity of the two events motivates them to think that it cannot be coincidental. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as non-participation, a sample size of 588 consisting of 482 males and 106 females was obtained. Participants were resident in Prestea, Asamankakraba, Kamporasi, Tarkwa, Akoon, Abontoako, New Atoano, Kofi Gyan, Cyanide, Brahabobom, Teberebie, and Low Cost. Others were resident in Huni Valley, Nsuta, Tamso, Simpa, Dompim, Nzemaline, Wassa Nkran, Efuanta, Damang, Dumasi, Dwabeng, Bogoso, and Bankyim.

In addition to the responses elicited via survey questionnaire, the quality of the ambient air where artisanal goldminers operate was assessed. One important air quality indicator namely suspended particulate matter (SPM), which is a complex, multi-phase system of all airborne solid and low vapor pressure liquid particles having aerodynamic particle sizes from below 0.01–100 μm and larger was measured. This air quality indicator comprises both total suspended particulates (TSP) and PM10 and was monitored using an Environmental Particulates Air Monitor (Model: EPAM-5000).

Measures

Dependent Variable

A Likert scale was developed for questionnaire responses on mercury-related health effects based on the literature (see World Health Organization (WHO), 2007; Steckling et al., 2011; Tomicic et al., 2011). The researchers ensured that acquiescence and habituation response bias (see Holbrook, 2008) were minimized. This was accomplished by allowing for question randomization; interspersing matrix questions with other types of questions and scales, and phrasing some questions in a manner that made respondents switch their thinking. Regarding the latter, we asked a series of positive questions in the survey questionnaire, and then threw in a couple of questions worded differently so as not to allow habituation or acquiescence.

Artisanal gold miners were asked to select whether they strongly disagree, agree, were undecided, agree or strongly agree with a series of questions on the health effects of mercury such as neurotoxicity, mental retardation, seizures, vision and hearing loss, delayed development, language disorders, memory loss frequent headaches, sleep disorder, unusual tiredness, trembling, and vision disorder, and kidney dysfunction or kidney damage. Based on the responses, some of the items were reverse coded to ensure that higher values correspond to accurate knowledge of health effects. The outcomes variable was derived from the scores on all the items on health effects of mercury. Scores that were greater than 3 on each item were considered as accurate knowledge of health effects of mercury.

Independent Variables

The inclusion of key independent variables in the model was based on theoretical relevance, practical significance and potential confounding. Variables that have frequently been shown to systematically vary with public knowledge were included. These include compositional attributes (including age, sex, and marital status, level of education, income, employment status, years of experience and ethnicity) and contextual factors such as number of years of residence in the community. We anticipate that educated individuals will be more likely to be knowledgeable about health effects of the work environment. Socio-culturally, educated individuals are also less subservient to norms and practices that adversely affect their occupation choices and health outcomes. Also, the general presumption in the literature is that the location of artisanal mine site distinguishes clearly between poor and good sanitation, housing structure and availability of disaster relief and health resources. In Ghana, not only are rural populations disadvantaged socio-economically, they are also historically underserved in health infrastructure and emergency relief personnel. Beyond these factors, the nature occupational setting including the environmental, safety, economic and health conditions also play a role in the health outcomes of artisanal gold miners. For this reason, these set of factors were also included as predictors in the analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests (see Lopes, 2011) were used to determine whether the random sampling data were normally distributed. In instances where this assumption of normality was violated, non-parametric statistics was used. The relationship between artisanal goldminer's knowledge of health effects of mercury intoxication on the one hand, and compositional, contextual and work-related quality indicators was assessed using a generalized linear model (GLM). The work-related quality indicators included health, safety, environment, and economic working conditions, and the frequency and duration of occupational health problems.

The GLM simplifies linear regression by allowing the model to be related to the response variable via a link function and by allowing the magnitude of the variance of each measurement to be a function of its predicted value (Aitkin et al., 2005). Under the assumption of binary response (i.e., had accurate knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure or not), there are several potential GLM alternatives: the logit model, probit model, negative log-log and complementary log-log models depending on the link function of the GLM (Aitkin et al., 2005; Fahrmeir and Tutz, 2013). Both logit and probit link functions have the same property, which is link [π(x)] = log[−log(1 − π(x))]. In this equation, the notation π is the probability that an observation is in a specified category of the binary outcome variable (i.e., had accurate knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure or not), generally called the “success probability.” In this equation, the response curve for π(x) has a symmetric appearance about the point π(x) = 0.5 and so π(x) has the same rate for approaching 0 as well as for approaching 1 (Fahrmeir and Tutz, 2001; Aitkin et al., 2005). Such a curve reflects a situation in which 50% of participants have accurate knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure. In this study, however, only 8% of respondents had accurate knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure indicating asymmetry in the distribution of the responses. For this reason, a negative log-log link function is rather appropriate for modeling the outcome variable (Fahrmeir and Tutz, 2001; Aitkin et al., 2005).

The objective of the study and theoretical relevance informed the sequence of entry of the variables into the statistical models. For analytical purposes, the odd ratios (OR) were estimated in the nested/incremental models, which were built starting from individual level characteristics through to occupational settings (i.e., compositional, contextual, and occupational factors). OR = 1 implies that higher values of the predictor does not affect the odds of having accurate knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure; OR > 1 implies that higher values of the predictor is associated with higher odds of accurate knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure, and OR < 1 implies that higher values of the predictor is associated with lower odds of accurate knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure. The GLMs are built under the assumption of independence of subjects, but the cross-sectional survey has a hierarchical structure with respondents nested within survey clusters, which could potentially bias the standard errors. STATA 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), which has the capacity to rectify this issue, is operationalized by introducing a “cluster” variable, the identification numbers of respondents at the cluster level, in the regression models. The standard errors (SE) are subsequently adjusted thereby ensuring statistically robust parameter estimates. Analyses were preceded by diagnostic tests to establish whether variables met the assumptions of the regression model. Univariate analysis of the categorical predictors was operationalized via Pearson's chi-square statistics. For continuous variables, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was computed. Zero-order associations between the dependent variable and the determinants were examined in the bivariate analysis. For the null hypothesis, an alpha value of 0.05 was considered as the threshold of statistical significance for both bivariate and multivariate relationships.

Results

In most of the locations where artisanal goldminers operate, the levels of PM10 were higher than both the Ghana Environmental Protection Agency standard of 70 μgm−3 and the WHO guideline value of 50 μgm−3. In about 4 out of 10 sampling locations TSP exceeded 200 μgm−3. In this context, artisanal goldmining locations in Prestea, Teberebie, Damang, Dumasi, and Tarkwa were non-compliant. Overall, the foregoing results suggest that the ambient air in some of the study sites was polluted in terms of PM10 and TSP.

Univariate and Bivariate Analyses

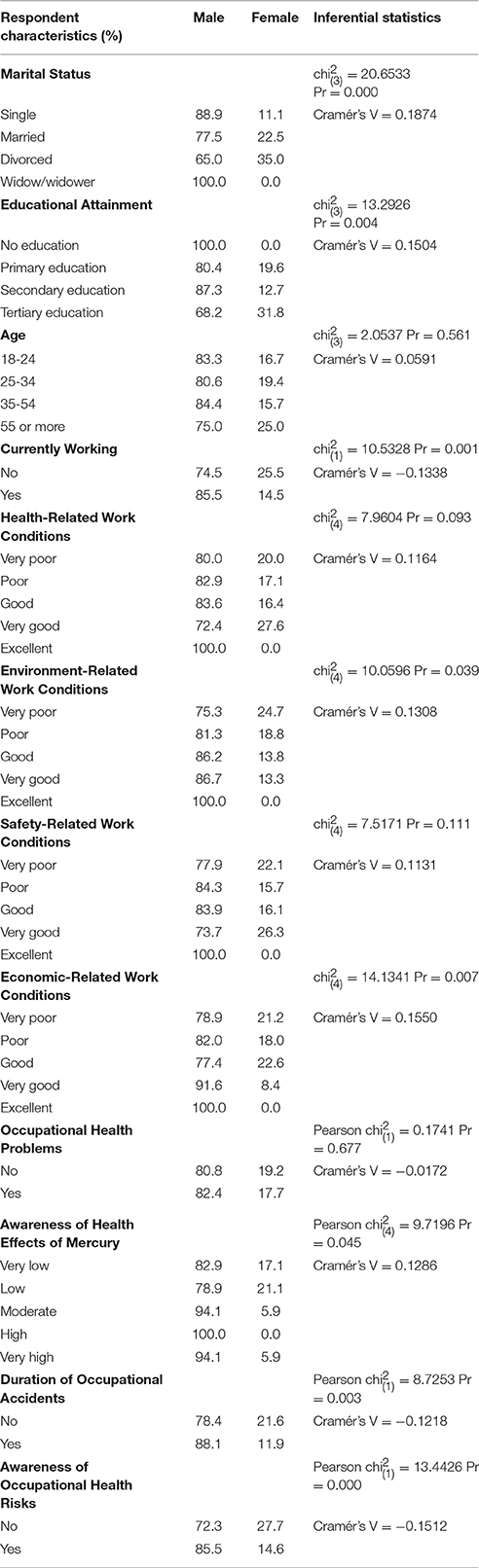

Respondent characteristics are shown in Table 1. Age of participants ranges between 18 and 62 years (mean = 25.54, SD = 4.38). Number of years of engagement in artisanal goldmining ranges between 1 and 44 years (mean = 6.51, SD = 6.87). Duration of residence in the community ranges between 1 and 60 years (mean = 26.19, SD = 13.87). There was a significant effect of years of experience on artisanal gold miners' knowledge of health effects of mercury intoxication [ANOVA, F(2.84) = 345.67, P < 0.0001]. Also, there were significant effects of residence time [ANOVA, F(4.56) = 137.30, P < 0.0001] and age of participant [ANOVA, F(50.40) = 6139.35, P < 0.0001]. Furthermore, there was interaction between years of experience and age of artisanal gold miners [ANOVA, F(5.02) = 493.36, P < 0.0001].

There were statistically significant differences in artisanal gold miners' knowledge of health effects of Hg by gender (χ2 = 9.72, df = 4; p < 0.045), age (χ2 = 33.40, df = 12; p < 0.001), educational attainment (χ2 = 120.82, df = 12; p < 0.0001), and employment status (χ2 = 17.49, df = 4; p < 0.002). This implies rejection of the null hypothesis of independence of these variables. It also suggests that the results for the sample would also be true for the larger population of artisanal miners from which they are drawn.

Based on chi-square statistics, and in terms of proportions, there were differences in awareness of health effects of mercury exposure by education, current employment status, environment-related working conditions and economic-related working conditions between male and female artisanal gold miners. However, there were no differences in age categories, health-related working conditions and safety-related working conditions between males and females (Table 1).

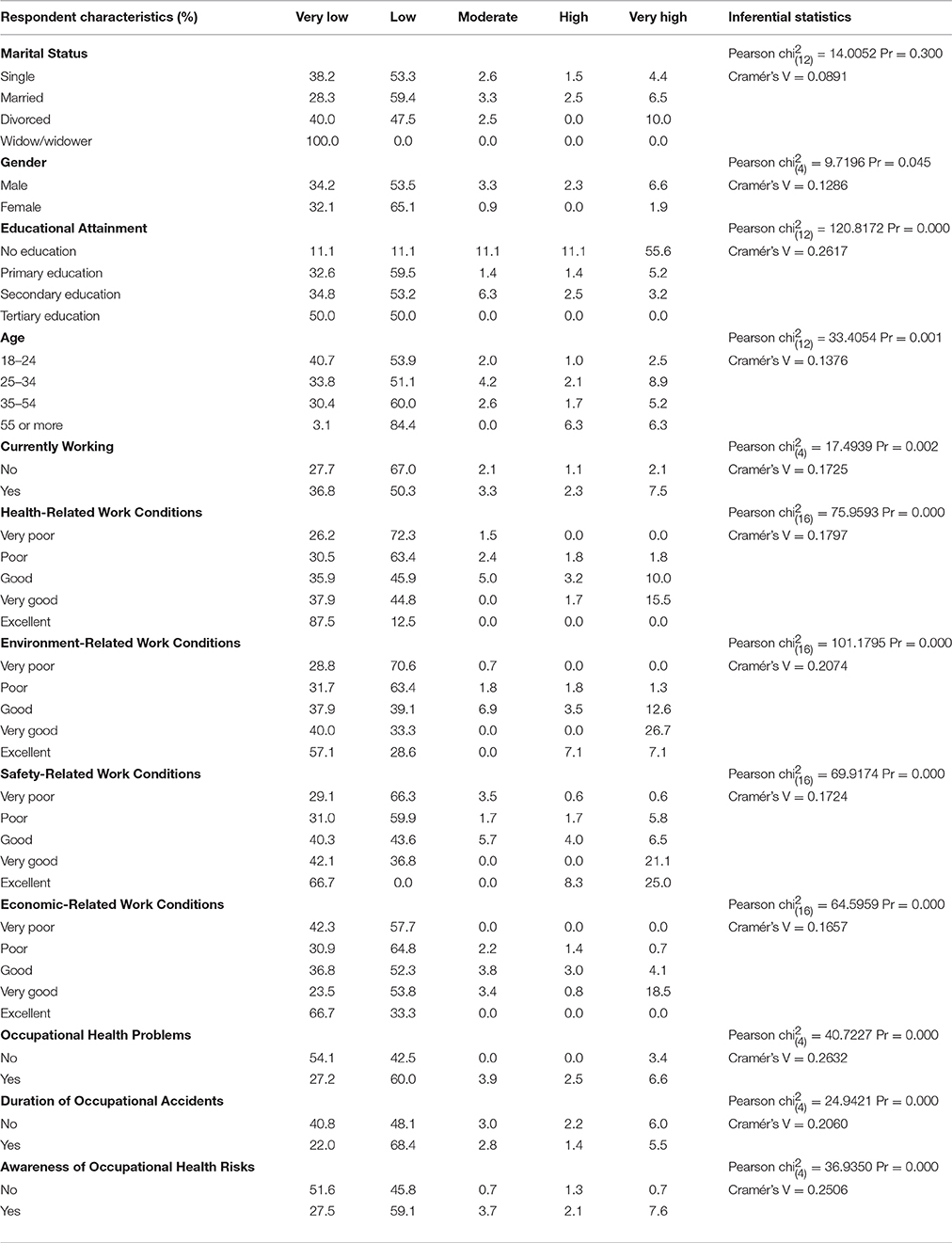

Knowledge of health effects of mercury intoxication are shown in Table 2. Overall, there are significant differences in the knowledge of artisanal gold miners by gender, educational attainment, age groups and awareness of occupational health risks. Similarly, differences in knowledge exist based on employment status and working conditions at the various mine sites. However, there are no differences in knowledge by marital status. Interestingly, about 50% of artisanal gold miners without formal education had very high levels of knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure. This appears counterintuitive until it is juxtaposed with number of years of experience on the job. This sub-group of artisanal gold miners happen to be the most experienced because they abandoned school for artisanal mining much earlier in the life course. Surprisingly, none of the artisanal miners who had attained tertiary education had high or very high levels of knowledge of mercury-related health effects (Table 2). Further analysis was carried out to pinpoint disproportionalities in sample distribution in relation to the level of knowledge of health effects of mercury intoxication. About 88% of male miners and 97% of female miners had low levels of knowledge of mercury-related health effects. All artisanal goldminers who had attained tertiary education had low levels of knowledge compared with 92% and 88% of goldminers with primary and secondary education, respectively. At least 8 out of 10 artisanal miners in each age category had low level of knowledge of mercury-related health effects.

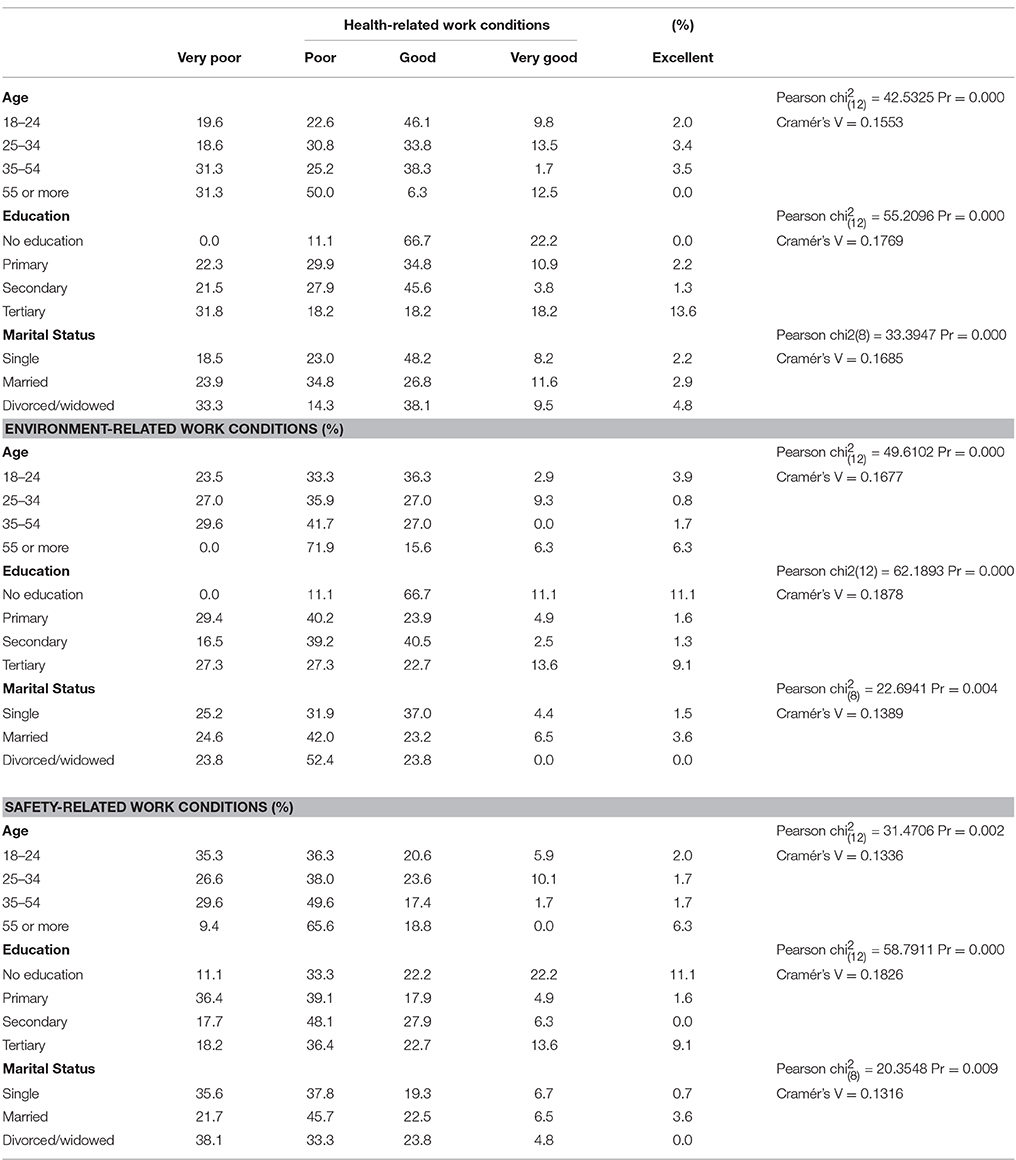

Table 3 indicates the proportions of artisanal gold miners based on their evaluation of a variety of working conditions. Very good and excellent working conditions were reported by only a few artisanal miners across age groups, educational attainment and categories of marital status. At the bivariate level, almost all of the theoretical factors were significant predictors of knowledge of small-scale gold miners on environmental and health effects of mercury. Bivariate results are reported in Table 4. On the whole, the bivariate results indicate that the directions of the parameter estimates were the same as in the multivariate model although the magnitudes, to some extent, varied.

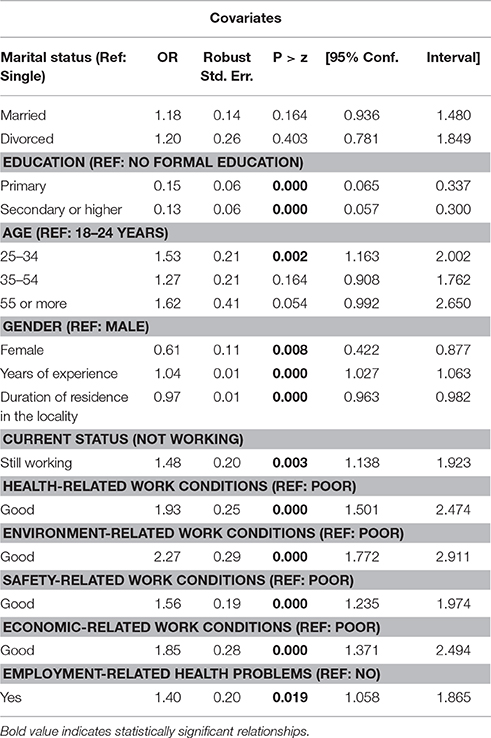

Table 4. Zero-order relationships between artisanal and small-scale gold miners knowledge of health effects of mercury use and theoretically-relevant factors (n = 588).

Marital status had no effect on artisanal and small-scale goldminer's level of knowledge of health effects of mercury. Artisanal goldminers who had attained any level of formal education were less likely to be knowledgeable about the effects of mercury intoxication compared with their uneducated counterparts. Miners in the 25–34 year category were 53% more likely to know the health effects associated with mercury use compared with those who were 18–24 years old. Female artisanal goldminers were 39% less likely to know health effects of mercury compared with their male co-workers. More experienced artisanal miners were 4% more knowledgeable about the effects of mercury intoxication compared with their less experienced colleagues. However, artisanal miners who had lived in the mining community for longer duration were 3% less likely to know the health effects of mercury intoxication compared with those who had lived there for a shorter period of time. Artisanal goldminers who reported good health-related, environment-related, safety-related, and economic-related working conditions were 93, 127, 56, and 85% respectively, more likely to know the health effects associated with mercury use compared with their counterparts who reported poor working conditions.

Multivariate Analyses

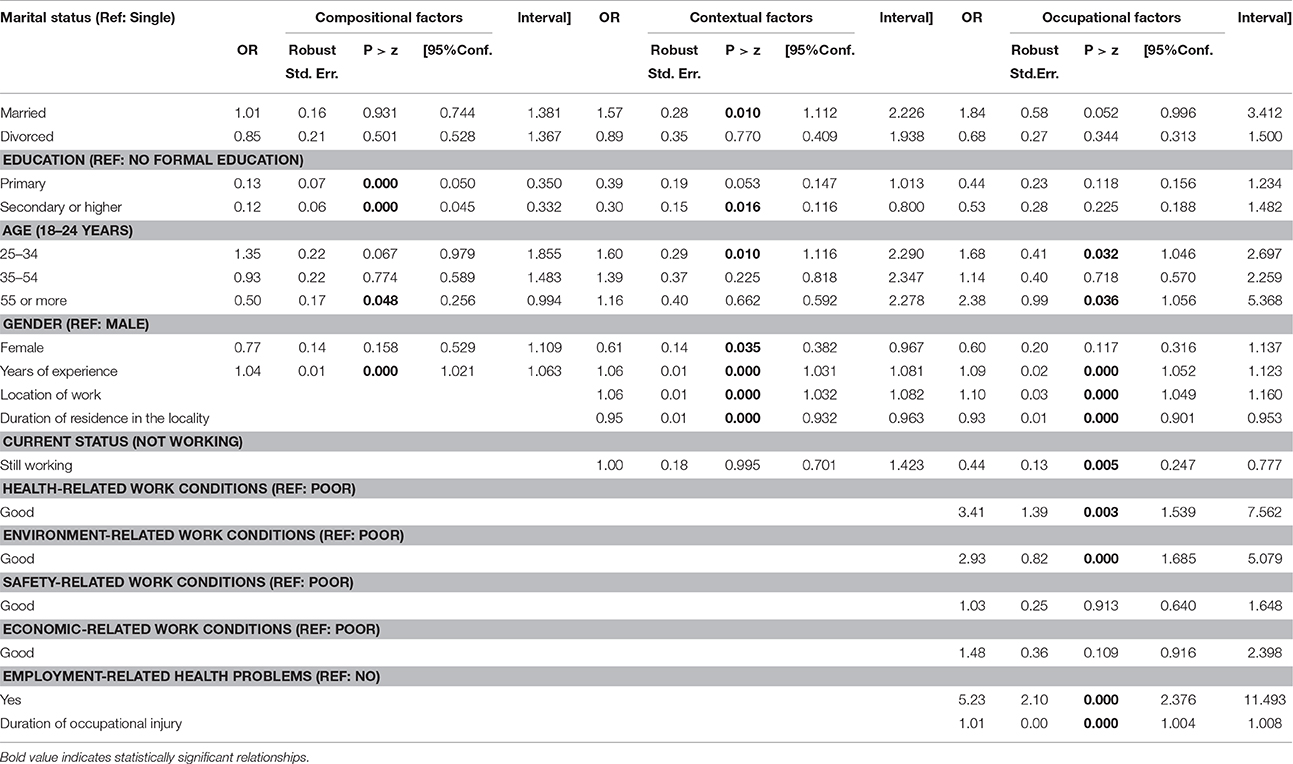

The multivariate relationship between artisanal and small-scale gold miners knowledge of the health effects of mercury and the determinants are presented in Table 5. In the compositional model, there were no relationships between gender and marital status, on the one hand, and artisanal gold miners' knowledge of mercury-induced health effects, on the other hand. Artisanal miners who had primary education were 87% less likely to have accurate knowledge of the health effects of mercury compared with their counterparts without formal education. Similarly, artisanal miners who had attained secondary or higher education had lower odds (OR = 0.12, P < 0.0001, CI: 0.045–0.332) of knowing the effects of mercury intoxication compared with those who had no formal education.

Table 5. Negative log-log model predicting knowledge of small-scale gold miners on environmental and health effects of mercury (n = 588).

At the multivariate level, age was not a significant predictor of knowledge except for artisanal miners in the 55 years or older age category. This group of artisanal miners were 50% less likely to know the health effects associated with mercury exposure compared with their counterparts who were in the 18–24 years old group. As expected, artisanal gold miners with more experience on job were more likely to be knowledgeable about the health effects of mercury exposure (OR = 1.04, P < 0.0001, CI: 1.021–1.063) compared with their colleagues with relatively fewer years of experience.

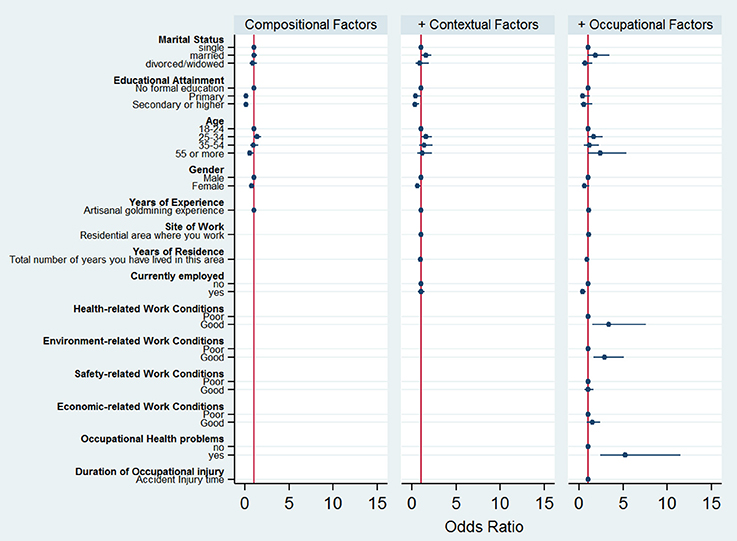

When contextual factors were incorporated in the multivariate model, several interesting relationships emerged (Figure 2). First, it became apparent that contextual factors suppress the relationship between marital status and artisanal gold miners' knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure. Also, the relationship between primary level of educational attainment and artisanal miners' knowledge of mercury-induced health effects disappeared completely indicating that contextual factors fully mediate this relationship. Likewise, the relationship between secondary or higher educational attainment was partially mediated by contextual factors (i.e., the level of statistical significance reduced).

Figure 2. Graphical representation of the multivariate relationships between artisanal gold miners' knowledge of health effects of mercury and theoretically-relevant factors.

Quite unexpectedly, individuals who had resided in the gold mining locality for a relatively longer period of time were 5% less likely to know the health effects of mercury compared with those who had lived in locality for a shorter period of time. Besides, the relationship between the 55 years or more age category and knowledge was completed mediated by contextual factors. Although, in the compositional model, there was no statistically significant relationship between the 25–34 year group and knowledge of mercury-related health effects, in the contextual model, there was suppression (i.e., it became statistically significant). The relationships between knowledge and education, marital status and gender, both in the compositional or contextual model, were not robust and disappeared when occupational factors were considered. Nevertheless, the relationships between artisanal miners' knowledge and years of experience and age were robust and persisted in the final model. Occupational factors also suppressed the relationship between current employment status and artisanal gold miners' knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure (i.e., it became statistically significant in the occupation model although it was not significant in the contextual model). All occupational factors except safety-related and economic-related working conditions were significant predictors of knowledge of artisanal miners on the health effects of mercury intoxication.

Discussion

This paper set out to assess the independent effects of compositional, contextual and occupational factors on artisanal gold miners' knowledge of the health impacts of mercury exposure. Artisanal gold mining in Ghana is not a new phenomenon. It is well known that the history of mining of precious minerals spans over 1000 years (see Hilson, 2002) and has shaped the goldmining and trading tradition anchored within Ghanaian social, cultural, political and economic fabric (Hilson, 2013). However, according to Armah et al. (2011), the regulation of artisanal gold mining is relatively recent and mining is set forth in the Small-Scale Gold Mining Law, 1989 (PNDCL 218). The Precious Minerals Marketing Corporation Law, 1989 (PNDCL 219), set up the Precious Minerals Marketing Corporation (PMMC) to promote the development of small-scale gold mining in Ghana and to purchase the output of such mining, either directly or through licensed buyers. A quarter of a century later, this legislation has failed such that Ghana must now cope with a new wave of miners, more scrupulous, and less inclined to making a living on subsistence mining (Armah et al., 2013b). Lately, residents in mining communities and other parts of Ghana have expressed outrage over the increased presence of Chinese mining companies that are buying up land with little regard for the socioeconomic and environmental and health repercussions on the local communities (Armah et al., 2013b).

Artisanal gold mining has come to stay, with some of the artisanal miners we interviewed, in this study, asserting that artisanal goldmining predates large scale mining. Artisanal gold mining can be a resilient livelihood choice for people who are vulnerable or looking for economic diversity in their livelihoods (see Hilson, 2013). In fact, ASM generates up to five times the income of other poverty-induced activities in agriculture and forestry in rural settings. According to Buxton (2013), ASM employs 10 times more people compared with the large-scale mining sector, and engenders substantial local economic development around ASM sites.

The influence of artisanal miners' socio-economic attributes on their knowledge of health effects of mercury was varied. Education, years of experience and duration of residence in the community were significant predictors of the knowledge of artisanal miners on the health effects associated with mercury intoxication. However, gender and marital status were not statistically significant.

On the whole, experienced artisanal gold miners were more likely to know the health effects of mercury exposure. Except those who were 55 years old or more, age did not influence the knowledge levels of artisanal gold miners on health effects of mercury. Surprisingly, individuals who had lived longer in the gold mining community were rather less likely to report knowledge of the health effects of mercury intoxication. In the literature, it has been suggested that exposure to inorganic mercury can affect the kidneys, causing immune-mediated kidney toxicity (Tchounwou et al., 2003). Effects may also include tremors, loss of co-ordination, slower physical and mental responses, gastric pain, vomiting, bloody diarrhea and gingivitis (Obiri et al., 2010; nur Akyildiz et al., 2012). Symptoms of methylmercury toxicity, also known as Minamata disease, range from tingling of the skin, numbness, lack of muscle coordination, tremor, tunnel vision, loss of hearing, slurred speech, skin rashes, abnormal behavior (such as fits of laughter), intellectual impairment, to cerebral palsy, coma and death, depending on the level of exposure (Grandjean et al., 2010; Karagas et al., 2012). In addition, methylmercury has been classified as a possible human carcinogen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. More recently, additional findings have described adverse cardiovascular and immune system effects at very low exposure levels (see Karagas et al., 2012). According to Bose-O'Reilly et al. (2010a), prenatal exposure to organic mercury, even at levels that seem not to affect the mother, may depress the development of the central nervous system and may cause psychomotor retardation for affected children. Similarly, Hong et al. (2012) suggests that minor delays in the nervous system and general development may occur in infants ingesting methylmercury in breast milk. Children who are exposed may show impaired coordination and growth, lesser intelligence, poor hearing and verbal development, cerebral palsy and behavioral problems.

It is quite interesting that artisanal gold miners who had attained secondary education or higher were significantly less likely to report knowing the health effects of mercury exposure. This result was unexpected given that, in the literature, a higher level of educational attainment is often associated with higher levels of knowledge. In the gold production chain, this highly educated group is less likely to work in the pits compared with those with primary or no education. Also, artisanal gold miners whose highest educational attainment is at the primary level were less likely to know the health outcomes of mercury intoxication compared with their counterparts with no formal education. These results are rather counterintuitive. Ordinarily, it is expected that formal education (schooling) will be positively associated with knowledge.

Artisanal goldminers who had secondary or higher education were less likely to report encountering health problems at work. This finding is consistent with the literature as demonstrated by Lynch (2003), Lleras-Muney (2005) and Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2006). Lynch (2003) argues that a strong positive association occurs between education and health outcomes as evidenced by illness (morbidity), death rates (mortality), health behaviors or health knowledge. According to Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2006), the link between education and health speaks to three conceivable categories of interactions: (a) a causal relationship emanating from increased education to improved health, (b) a reverse causal link, demonstrating that better health leads to greater education; or (c) an absence of a causal relationship between education and health, which seem to be correlated owing to possible unobserved elements affecting both health and education in a unidirectional manner. Palpably, the three mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. For this reason, it is to be expected that some combination of the three is likely to provide the most plausible explanation of the strong correlations regularly established between education and health across countries (Lleras-Muney, 2005). Unobserved heterogeneity that likely contributes to the third well-documented pathway comprise genetic traits, family background and individual differences (Lleras-Muney, 2005).

Occupational factors such as environment-related and health-related working conditions were significant predictors of knowledge of artisanal miners on the health effects of mercury intoxication. Considerably, health is determined by the type of work undertaken, the likelihood of encountering hazards and the physical work environment (Doyle et al., 2005). Beyond these factors, the degree of control an individual has in the working environment coupled with relationships with colleagues and management cumulatively determine health (Pejtersen and Kristensen, 2009; Nieuwenhuijsen et al., 2010). It has been suggested that individuals with higher levels of educational are more likely to work in a safer environment and report an increased likelihood of having satisfying, personally worthwhile jobs (Ross and Wu, 1995; Pejtersen and Kristensen, 2009; Nieuwenhuijsen et al., 2010; Rugulies, 2012).

Policy Implications

Overall, this study shows a complex relationship between artisanal gold miners' knowledge of the health impacts of mercury exposure and compositional, contextual and occupational factors. For instance, some artisanal goldminers had high level of knowledge of health effects of mercury but did not necessarily translate into cleaner production. This suggests the need to understand the mechanisms that mediate the effects of knowledge on artisanal goldminers' production practices and behaviors in the work environment. Understanding the knowledge, attitudes and practices of artisanal gold miners, and the compositional, contextual and occupational factors that mutually reinforce the health behaviors of these goldminers, is very crucial given that policymakers in Ghana have sought, over the years, to promote the diffusion of environmentally- and health-friendly technologies in the artisanal gold mining sector, albeit with limited success. This understanding is also critical for sustainable management of groundwater and freshwater resources in the country and at the basin level.

The findings of this study bear relevant policy implications for cleaner production of gold by artisanal and small-scale miners in Ghana and other developing countries. Although it is well-documented that one of the keys to accomplishing sustainable development is changing the production patterns that waste resources and emit more pollutants than our ecosystem can contain, research on the role of knowledge in driving human behavior toward cleaner production in the artisanal goldmining sector is rather nascent. The main difficulties encountered in estimating the causal impact of work-related behaviors of artisanal goldminers on their health include measurement problems, sample representativeness and potential endogeneity issues. In most cases, the health risk factors (e.g., age and number of years of experience of miner) are often correlated between them, besides there may be a third set of unobservable factors that influence both knowledge of artisanal goldminers and their health. Lately, some researchers have attempted to surmount these confounding problems using panel data and methodological techniques such as instrumental variables. By and large, multidisciplinary research initiatives hold promise in addressing the challenges associated with understanding the nexus between artisanal goldminer's knowledge and cleaner production of gold.

Conclusion

The relationship between artisanal gold miners' knowledge of the health effects of mercury exposure and composition and contextual factors was assessed. We also evaluated how this relationship is modified when environmental, health, safety and economic conditions within the occupational setting are taken into account. The main objective of this study was to understand the complex relationships among these determinants; and to improve understanding on the most effective interventions and policies for driving human behavior toward cleaner production. Based on Cramér's V statistic, the magnitude of effect size of the determinants of artisanal goldminers knowledge of the health effects of mercury intoxication, in decreasing order, is as follows: occupational health problems > educational attainment > awareness of occupational health risks > environment-related working conditions > duration of occupational accidents > health-related working conditions > current employment status > safety-related working conditions > economic-related working conditions > age > gender. Although some artisanal goldminers were highly aware of the health effects of mercury, this knowledge did not necessarily translate into cleaner production behaviors. Due to different perspectives on why artisanal gold miners still use mercury despite its well-known health risks diverse recommendations have been made. These recommendations suggest that our understanding of the complex relationships between modifiable, social determinants and general health of artisanal gold miners is still evolving. In this context, it is pertinent to emphasize cognitive, emotional and motivational levels when we educate artisanal gold miners of relevant hazards and health risks of mercury in the occupational setting. Imagery concerning desired behavior is important when communicating this information. Broadly, we require the need to highlight the context and the capacity of social, economic, cultural, and physical environments to modify the relationship between individual characteristics of artisanal gold miners and health; recognition of the complexity of these interactions; and a shift of attention from treatment of sick artisanal and small scale gold miners to addressing the factors that can forestall the emergence of health disparities.

Author Contributions

FA and SO were involved in the conception and design of the study. FA was involved in acquisition of data. SB, FA, RQ, IL, and SO were involved in analysis and interpretation of data. SB, FA, RQ, IL, and SO were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. SB, FA, RQ, IL, and SO were involved in final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aitkin, M. A., Francis, B., and Hinde, J. (2005). Statistical Modelling in GLIM 4, Vol. 32. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Armah, F. A., Boamah, S. A., Quansah, R., Obiri, S., and Luginaah, I. (2016). Working conditions of male and female artisanal and small-scale goldminers in Ghana: examining existing disparities. Extractive Industries Soc. 3, 464–474. doi: 10.1016/j.exis.2015.12.010

Armah, F. A., and Gyeabour, E. K. (2013). Health risks to children and adults residing in riverine environments where surficial sediments contain metals generated by active gold mining in Ghana. Toxicol. Res. 29, 69–79. doi: 10.5487/TR.2013.29.1.069

Armah, F. A., Luginaah, I., and Obiri, S. (2012). Assessing environmental exposure and health impacts of gold mining in Ghana. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 94, 786–798. doi: 10.1080/02772248.2012.667205

Armah, F. A., Luginaah, I., and Odoi, J. (2013b). Artisanal small-scale mining and mercury pollution in Ghana: a critical examination of a messy minerals and gold mining policy. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 3, 381–390. doi: 10.1007/s13412-013-0147-7

Armah, F. A., Luginaah, I., Yengoh, G. T., Taabazuing, J., and Yawson, D. O. (2014). Management of natural resources in a conflicting environment in Ghana: unmasking a messy policy problem. J. Environ. Plann. Manage. 57, 1724–1745. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2013.834247

Armah, F. A., Luginaah, I. N., Taabazuing, J., and Odoi, J. O. (2013a). Artisanal gold mining and surface water pollution in Ghana: have the foreign invaders come to stay? Environ. Justice 6, 94–102. doi: 10.1089/env.2013.0006

Armah, F. A., Obiri, S., Yawson, D. O., Afrifa, E. K. A., Yengoh, G. T., Alkan Olsson, J., et al. (2011). Assessment of legal framework for corporate environmental behaviour and perceptions of residents in mining communities in Ghana. J. Environ. Plann. Manage. 54, 193–209. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2010.505818

Armah, F. A., Obiri, S., Yawson, D. O., Onumah, E. E., Yengoh, G. T., Afrifa, E. K., et al. (2010). Anthropogenic sources and environmentally relevant concentrations of heavy metals in surface water of a mining district in Ghana: a multivariate statistical approach. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 45, 1804–1813. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2010.513296

Bernhoft, R. A. (2011). Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. J. Environ. Public Health 2012:460508. doi: 10.1155/2012/460508

Bose-O'Reilly, S., Drasch, G., Beinhoff, C., Tesha, A., Drasch, K., Roider, G., et al. (2010b). Health assessment of artisanal gold miners in Tanzania. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 796–805. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.051

Bose-O'Reilly, S., McCarty, K. M., Steckling, N., and Lettmeier, B. (2010a). Mercury exposure and children's health. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 40, 186–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.07.002

Buxton, A. (2013). “Responding to the challenge of artisanal and small-scale mining,” How Can Knowledge Networks Help. Available online at: xa.yimg.com/kq/groups/21460604/783943597/name/ASM-report-IIED.pdf (Accessed 27th August 2015).

Calys-Tagoe, B. N., Ovadje, L., Clarke, E., Basu, N., and Robins, T. (2015). Injury profiles associated with artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Tarkwa, Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 7922–7937. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120707922

Charles, E., Thomas, D. S., Dewey, D., Davey, M., Ngallaba, S. E., and Konje, E. (2013). A cross-sectional survey on knowledge and perceptions of health risks associated with arsenic and mercury contamination from artisanal gold mining in Tanzania. BMC Public Health 13:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-74

Cordy, P., Veiga, M. M., Salih, I., Al-Saadi, S., Console, S., Garcia, O., et al. (2011). Mercury contamination from artisanal gold mining in Antioquia, Colombia: the world's highest per capita mercury pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 410, 154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.09.006

Cutler, D. M., and Lleras-Muney, A. (2006). Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence (No. w12352). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Davis, J. S. (2005). “Is it really safe? That's what we want to know”: science, stories, and dangerous places. Prof. Geogr. 57, 213–221. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-0124.2005.00473.x

Doyle, C., Kavanagh, P., Metcalfe, O., and Lavin, T. (2005). Health Impacts of Employment: A Review. Ireland: Institute of Public Health in Ireland. Dublin.

Dzigbodi-Adjimah, K. (1993). Geology and geochemical patterns of the Birimian gold deposits, Ghana, West Africa. J. Geochem. Explor. 47, 305–320. doi: 10.1016/0375-6742(93)90073-U

Eisler, R. (2003). Health risks of gold miners: a synoptic review. Environ. Geochem. Health 25, 325–345. doi: 10.1023/A:1024573701073

Fahrmeir, L., and Tutz, G. (2001). Multivariate Statistical Modelling based on Generalised Linear Models, 2nd Edn. Berlin: Springer.

Fahrmeir, L., and Tutz, G. (2013). Multivariate Statistical Modelling Based on Generalized Linear Models. Dordrecht: Springer Science and Business Media.

Grandjean, P., Satoh, H., Murata, K., and Eto, K. (2010). Adverse effects of methylmercury: environmental health research implications. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 1137–1145. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901757

Hilson, G. (2002). The environmental impact of small-scale gold mining in Ghana: identifying problems and solutions. Geogr. J. 168, 57–72. doi: 10.1111/1475-4959.00038

Hilson, G. (2013). Creating” rural informality: the case of artisanal gold mining in sub-Saharan Africa. SAIS Rev. Int. Aff. 33, 51–64. doi: 10.1353/sais.2013.0014

Hilson, G., Hilson, A., and Adu-Darko, E. (2014). Chinese participation in Ghana's informal gold mining economy: drivers, implications and clarifications. J. Rural Stud. 34, 292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.03.001

Holbrook, A. (2008). “Acquiescence response bias,” in Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods, ed Paul J. Lavrakas (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.), 4–5.

Hong, Y. S., Kim, Y. M., and Lee, K. E. (2012). Methylmercury exposure and health effects. J. Prevent. Med. Public Health 45:353. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.6.353

Houston, M. C. (2011). Role of mercury toxicity in hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. J. Clin. Hypertens. 13, 621–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00489.x

Jasanoff, S. (1999). The songlines of risk. Environ. Values 8, 135–152. doi: 10.3197/096327199129341761

Johnson, B. B. (1993). Advancing understanding of knowledge's role in lay risk perception. Risk 4, 189–212.

Jønsson, J. B., Charles, E., and Kalvig, P. (2013). Toxic mercury versus appropriate technology: artisanal gold miners' retort aversion. Resour. Policy 38, 60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.09.001

Karagas, M. R., Choi, A. L., Oken, E., Horvat, M., Schoeny, R., Kamai, E., et al. (2012). Evidence on the human health effects of low level methylmercury exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 799–806. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104494

Kasperson, R. E., and Kasperson, J. X. (1996). The social amplification and attenuation of risk. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 545, 95–105. doi: 10.1177/0002716296545001010

Kuma, J. S., and Younger, P. L. (2004). Water quality trends in the Tarkwa gold-mining district, Ghana. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 63, 119–132. doi: 10.1007/s10064-004-0227-8

Leube, A., Hirdes, W., Mauer, R., and Kesse, G. O. (1990). The early Proterozoic Birimian Supergroup of Ghana and some aspects of its associated gold mineralization. Precambrian Res. 46, 139–165. doi: 10.1016/0301-9268(90)90070-7

Lleras-Muney, A. (2005). The relationship between education and adult mortality in the United States. Rev. Econ. Stud. 72, 189–221. doi: 10.1111/0034-6527.00329

Lopes, R. H. (2011). “Kolmogorov-smirnov test,” in International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science, ed M. Lovric (Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer), 718–720.

Lynch, S. M. (2003). Cohort and life-course patterns in the relationship between education and health: a hierarchical approach. Demography 40, 309–331. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0016

Macdonald, F. K., Lund, M., Blanchette, M., and McCullough, C. (2014). Regulation of Artisanal Small Scale Gold Mining (ASGM) in Ghana and Indonesia as Currently Implemented Fails to Adequately Protect Aquatic Ecosystems. Available online at: http://www.mwen.info/docs/imwa_2014/IMWA2014_Macdonald_401.pdf

Milési, J. P., Ledru, P., Ankrah, P., Johan, V., Marcoux, E., and Vinchon, C. (1991). The metallogenic relationship between Birimian and Tarkwaian gold deposits in Ghana. Miner. Deposita 26, 228–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00209263

Nieuwenhuijsen, K., Bruinvels, D., and Frings-Dresen, M. (2010). Psychosocial work environment and stress-related disorders, a systematic review. Occup. Med. 60, 277–286. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq081

nur Akyildiz, B., Kondolot, M., Kurtoglu, S., and Konuskan, B. (2012). Case series of mercury toxicity among children in a hot, closed environment. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 28, 254–258. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182494ed0

Nweke, O. C., and Sanders, W. H. III. (2009). Modern environmental health hazards: a public health issue of increasing significance in Africa. Environ. Health Perspect. 117, 863–870. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800126

Obiri, S., Dodoo, D. K., Armah, F. A., Essumang, D. K., and Cobbina, S. J. (2010). Evaluation of lead and mercury neurotoxic health risk by resident children in the Obuasi municipality, Ghana. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 29, 209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2010.01.001

Oxford Business Group (2013). The Report: Ghana 2013. Available online at: http://www.oxfordbusinessgroup.com/ghana-2013-mining (Accessed 10th January 2016)

Pejtersen, J. H., and Kristensen, T. S. (2009). The development of the psychosocial work environment in Denmark from 1997 to 2005. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 35, 284–293. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1334

Ross, C. E., and Wu, C. L. (1995). The links between education and health. Am. Sociol. Rev. 60, 719–745. doi: 10.2307/2096319

Rugulies, R. (2012). Studying the effect of the psychosocial work environment on risk of ill-health: towards a more comprehensive assessment of working conditions. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 38, 187–191. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3296

Schwarzenbach, R. P., Egli, T., Hofstetter, T. B., Von Gunten, U., and Wehrli, B. (2010). Global water pollution and human health. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 35, 109–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-100809-125342

Shandro, J. A., Veiga, M. M., and Chouinard, R. (2009). Reducing mercury pollution from artisanal gold mining in Munhena, Mozambique. J. Clean. Prod. 17, 525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.09.005

Sieber, N. L., and Brain, J. (2014). Health Impact of Artisanal Gold Mining in Latin America: A Mining Boom Brings Risk from Mercury Contamination. Revista: Harvard Review of Latin America. Available online at: http://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/book/health-impact-artisanal-gold-mining-latin-america Accessed (26th August 2015).

Sjoberg, L. (1999). Consequences of perceived risk: demand for mitigation. J. Risk Res. 2, 129–149. doi: 10.1080/136698799376899

Slovic, P., Peters, E., Finucane, M. L., and MacGregor, D. G. (2005). Affect, risk, and decision making. Health Psychol. 24:S35. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S35

Spiegel, S. J., and Veiga, M. M. (2010). International guidelines on mercury management in small-scale gold mining. J. Clean. Prod. 18, 375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.10.020

Spurgeon, A., Gompertz, D., and Harrington, J. M. (1996). Modifiers of non-specific symptoms in occupational and environmental syndromes. Occup. Environ. Med. 53, 361–366. doi: 10.1136/oem.53.6.361

Steckling, N., Boese-O'Reilly, S., Gradel, C., Gutschmidt, K., Shinee, E., Altangerel, E., et al. (2011). Mercury exposure in female artisanal small-scale gold miners (ASGM) in Mongolia: an analysis of human biomonitoring (HBM) data from 2008. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 994–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.11.029

Swain, E. B., Jakus, P. M., Rice, G., Lupi, F., Maxson, P. A., Pacyna, J. M., et al. (2007). Socioeconomic consequences of mercury use and pollution. Ambio 36, 45–61. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[45:SCOMUA]2.0.CO;2

Swenson, J. J., Carter, C. E., Domec, J. C., and Delgado, C. I. (2011). Gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon: global prices, deforestation, and mercury imports. PLoS ONE 6:e18875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018875

Tchounwou, P. B., Ayensu, W. K., Ninashvili, N., and Sutton, D. (2003). Review: environmental exposure to mercury and its toxicopathologic implications for public health. Environ. Toxicol. 18, 149–175. doi: 10.1002/tox.10116

Telmer, K., and Stapper, D. (2012). A Practical Guide: Reducing Mercury Use in Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining. Nairobi; Geneva: United Nations Environment Programme. Available online at: http://goo.gl/8geux (Accessed 26th August 2015).

Telmer, K. H., and Veiga, M. M. (2009). “World emissions of mercury from artisanal and small scale gold mining,” in Mercury Fate and Transport in the Global Atmosphere, eds N. Pirrone and R. Mason (Dordrecht: Springer), 131–172.

Tomicic, C., Vernez, D., Belem, T., and Berode, M. (2011). Human mercury exposure associated with small-scale gold mining in Burkina Faso. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 84, 539–546. doi: 10.1007/s00420-011-0615-x

Veiga, M. M., Angeloci, G., Hitch, M., and Velasquez-Lopez, P. C. (2014). Processing centres in artisanal gold mining. J. Clean. Prod. 64, 535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.08.015

Veiga, M. M., and Baker, R. F. (2004). Protocols for Environmental and Health Assessment of Mercury Released by Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Miners. Vienna: GEF/UNDP/UNIDO. Available online at: http://www.unep.org/hazardoussubstances/Portals/9/Mercury/Documents/ASGM/PROTOCOLS%20FOR%20ENVIRONMENTAL%20ASSESSMENT%20REVISION%2018-FINAL%20BOOK%20sb.pdf

Wilson, M. L., Renne, E., Roncoli, C., Agyei-Baffour, P., and Tenkorang, E. Y. (2015). Integrated assessment of artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Ghana—Part 3: social sciences and economics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 8133–8156. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120708133

World Health Organization (WHO) (2003). Elemental Mercury and Inorganic Mercury Compounds: Human Health Aspects. Available online at: http://www.inchem.org/documents/cicads/cicads/cicad50.htm (Accessed 15th September 2015).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2007). Exposure to Mercury: A Major Public Health Concern. Available online at: http://www.who.int/ipcs/features/mercury.pdf (Accessed 15th February 2015).

Keywords: gold miners, risk, perception, knowledge, health, environment, Ghana

Citation: Armah FA, Boamah SA, Quansah R, Obiri S and Luginaah I (2016) Unsafe Occupational Health Behaviors: Understanding Mercury-Related Environmental Health Risks to Artisanal Gold Miners in Ghana. Front. Environ. Sci. 4:29. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2016.00029

Received: 25 September 2015; Accepted: 29 March 2016;

Published: 25 April 2016.

Edited by:

Ramanathan Alagappan, Jawahralal Nehru University, IndiaReviewed by:

Sutapa Bose, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata, IndiaAlejandra Vanina Volpedo, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Copyright © 2016 Armah, Boamah, Quansah, Obiri and Luginaah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Frederick A. Armah, farmah@ucc.edu.gh

Frederick A. Armah

Frederick A. Armah Sheila A. Boamah2

Sheila A. Boamah2 Reginald Quansah

Reginald Quansah