- 1Department of Nursing, Hawassa College of Health Sciences, Hawassa, Ethiopia

- 2Department of Nursing, School of Health Sciences, Goba Referral Hospital, Madda Walabu University, Bale Goba, Ethiopia

- 3Department of Nursing, Wachemo University, Hossana, Ethiopia

- 4Department of Public Health, Hawassa College of Health Sciences, Hawassa, Ethiopia

Background: Workplace violence among nurses has increased dramatically in the last decade. Still, mitigation techniques have not been well explored; many studies used a quantitative research approach, and there is a knowledge gap on the current status of workplace violence. The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of workplace violence and associated factors among nurses working at university teaching hospitals in the South Region of Ethiopia.

Methods: An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted using a mixed approach. A random sample of 400 nurses was interviewed for the quantitative analysis, and nine key informants were interviewed for the qualitative analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. A logistic regression model was used to analyze the data. An adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval and a corresponding p-value < 0.05 was used to determine the association between variables. The qualitative data were transcribed and translated, then themes were created, followed by thematic analysis using Open Code version 4.02.

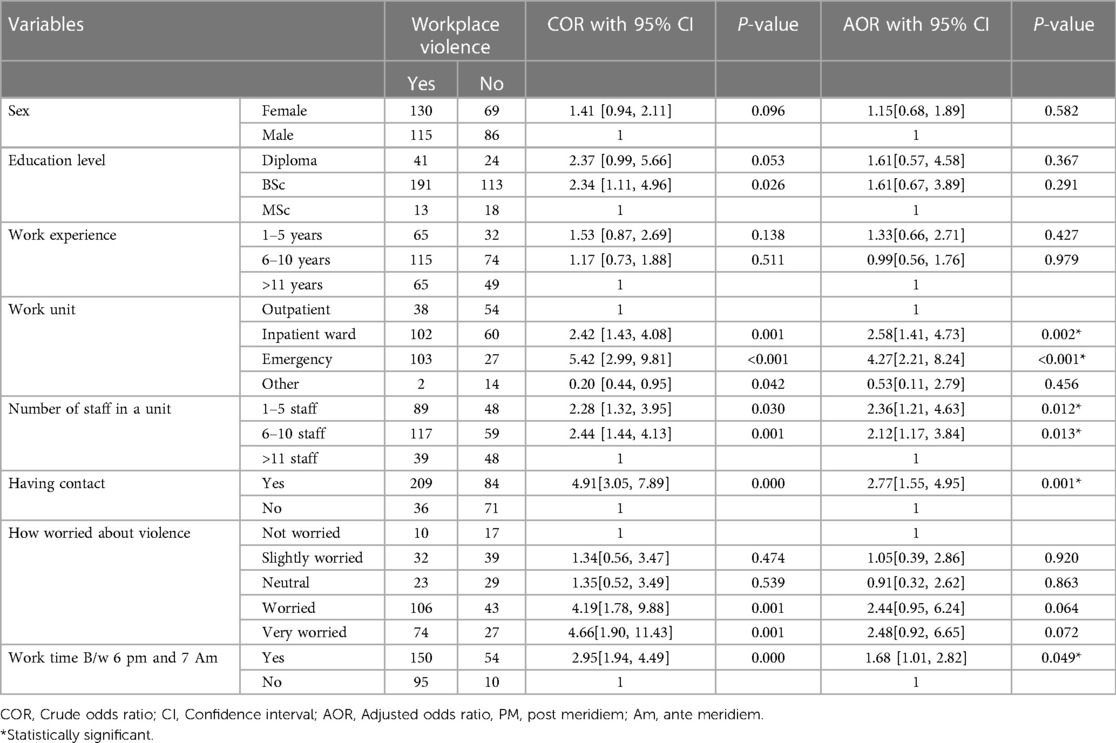

Results: The prevalence of workplace violence was 61.3% within the last 12 months. Nurses working in emergency departments [AOR = 4.27, 95% CI: 2.21, 8.24], nurses working in inpatient departments [AOR = 2.58, 95% CI: 1.40, 4.72], the number of nurses in the same working unit from one to five [AOR = 2.36, 95% CI: 1.21, 4.63], and six to ten staff nurses [AOR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.17, 3.85], nurses routinely making direct physical contact [AOR = 2.77, 95% CI: 1.55, 4.95], and nurses' work time between 6 pm and 7 am [AOR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.00, 2.82] were factors significantly associated with workplace violence.

Conclusion: In this study, the prevalence of workplace violence against nurses was high. We identified factors significantly associated with workplace violence among nurses. Interventions should focus on early risk identification, the management of violent incidents, and the establishment of violence protection strategies that consider contextual factors to reduce workplace violence.

Introduction

Workplace violence (WPV) is defined as incidents where staff is abused, threatened, or assaulted in circumstances related to their work, including commuting to and from work, involving an explicit or implicit threat to their health, safety, or well-being (1). According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, workplace injuries are classified as Type I: the perpetrator is acting criminally and has no ties to the company or its workers, Type II: When a customer, client, or patient receives care or services, they get violent. Type III: employee-to-employee violence, and Type IV: personal relationship violence (2). Workplace violence against nurses has increased dramatically in the last decade. According to some research, there has been a 110 percent increase in the rate of violent injuries against health care employees in the last decade in the United States of America (USA) from 2005 to 2014 (3).

Workplace violence toward health service professionals is recognized as a global public health issue (4). Violence against nurses is a major challenge for healthcare administrators. So workplace violence is considered an endemic problem in the health care system (5), and nurses are at a higher risk of abuse compared to other healthcare providers (3). Nearly 1/4th of the world`s workplace violence occurs in that sector (6). Workplace violence in the health sector found that nurses were three times more likely than other occupational groups to experience workplace violence (7).

Violence against nurses at the workplace is increasing at an alarming rate in both developed and developing countries, affecting the quality of their work (3). Nurses frequently experience violence, which causes feelings of job insecurity and physical and psychological injury (8). Also, workplace violence decreases interest in the job, causes burnout, turnover, and feelings of inadequate support, reduces the organization's power, and ultimately reduces the performance and reputation of the organization (8). Many studies were done using a quantitative approach, which provided less detail on perception, motivation, and belief among nurses. To the knowledge of the investigators, much is not known about the prevalence and factors associated with workplace violence among nurses. The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and associated factors of workplace violence among nurses working at university teaching hospitals in the South Region of Ethiopia, using a mixed approach.

Materials and methods

Study setting and period

The study was conducted at the university teaching hospitals found in SNNPR, South Ethiopia. SNNPR is the third-largest administrative region in the country and the most diverse region in terms of language, culture, and ethnic background. Administratively, the region is divided into 15 zones and 7 special districts. According to the 2021 Regional Health Bureau Report, there is one specialized hospital, four university teaching hospitals, nine general hospitals, 59 primary hospitals, 594 health centers, and 3,422 health posts found in the region. Wolkite, Wachemo, and Wolaita Sodo University Teaching Hospitals were included in the study. According to the human resource management report, there were 950 nurses in total (156 at Wolkite University Teaching Hospital, 342 at Wachemo University Teaching Hospital, and 452 at Wolaita Sodo University Teaching Hospital). The study was conducted to assess workplace violence among nurses within the past 12 months, from April 6 to May 6, 2022.

Study design

Institution-based cross-sectional study that includes both quantitative and qualitative methods was conducted.

Study population and sample size

Nurses working at the teaching hospitals in the South Region of Ethiopia were included in the study. Academic staff nurses were not included in the study. The sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula, considering the 43.1% prevalence of WPV in public health facilities in Gamo Gofa, Ethiopia (9). Assuming the margin of error is 0.05, and the confidence level of 0.05 at a 95% confidence interval (9). It was calculated as n = (Z1-α/2)2 p (1-p)/d2 = (1.96)2*0.431*0.569/0.05)2 = 377. The calculated sample size was 377. Adding the 10% non-response rate, a total of 415 randomly selected nurses were included in the study by proportional allocation. For the qualitative part, nine purposefully selected staff nurses, unit leader nurses, and matrons of the University Teaching Hospitals, SNNPR, South Ethiopia, were involved in the study.

Main study outcome variable

The main outcome variable in this study was workplace violence among nurses within the last 12 months, which included abuse, threat, or assault related to their work, including commuting to and from work, involving an explicit or implicit threat to their health, safety, or well-being. The outcome variable was obtained using the question, “In the last 12 months, have you been attacked in your workplace?” It was explained as a categorical variable with two possible values: the presence (“yes”) or absence (“no”) of workplace violence.

Data collection tools and procedure

The questionnaire adapted from “WPV in the Healthcare Sector” developed by the “Joint Programme on WPV in the Health Sector by ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI” and an instrument developed by the American Emergency Nurses Association were used in this study (7). The questionnaire was prepared first in English, translated into Amharic, and then back to English to maintain its consistency. A pretest was done on five percent of the total sample size at Hawassa University Teaching Hospital to evaluate the validity of the instruments. The data were collected on socio-demographic and workplace characteristics, physical violence, verbal abuse, and sexual harassment by nurses in their workplaces. Two BSc. nurses were used as data collection facilitators, with one supervisor per hospital. Both the facilitators and supervisors were given a one-day training to explain the aim and content of the instrument and ensure the quality of the data. The collected data were checked for completeness and consistency on the spot during the data collection period.

Concerning qualitative data, the principal investigator and one supervisor conducted the interview, which was guided by an unstructured questionnaire. Each individual contributor was interviewed separately in a private room, at a different time, outside of working hours, for 20–30 min. The interview was tape-recorded, and the principal investigator took notes to capture the conversation points. To ensure the credibility of the qualitative data, we used members' checks by sending the findings back to key informants for confirmation and validation of their opinion and perception, and the consistency of the findings with the raw data was checked.

Data analysis

The data were checked for completeness, coded, and entered into Epi Data version 3.1. Then the data were exported and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 26. Frequency with a percentage was used to report categorical variables, while mean with a standard deviation was used to report continuous variables. Binary logistic regression was conducted to identify candidate variables for the adjusted model, with a p-value of ≤0.25. The variables considered include: sex of respondents, level of education, work experience, work unit, number of staff in the same working unit, routine direct physical contact with the client, worry about violence in the workplace, and work time between 6 p.m. and 7 a.m. The model's fitness was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow fitness of good test, which yielded a non-significant value (p = 0.604), indicating that the data fit reasonably well. The variance inflation factor was used to determine multicollinearity (VIF = 1.02), showing the absence of extreme multicollinearity among explanatory variables. An adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval was used to identify factors significantly associated with the outcome variable.

The qualitative data were transcribed word for word into the local language and then translated into English after the in-depth interview. Then, based on the study's subject topic or key variables, similar replies were aggregated and summarized. By importing the data in plain text into Open Code version 4.02, codes were created, followed by categories and themes. The themes were defined and interpreted, followed by a narration of the pertinent findings. Finally, the qualitative findings were presented in a narrative format.

Results

Quantitative analysis

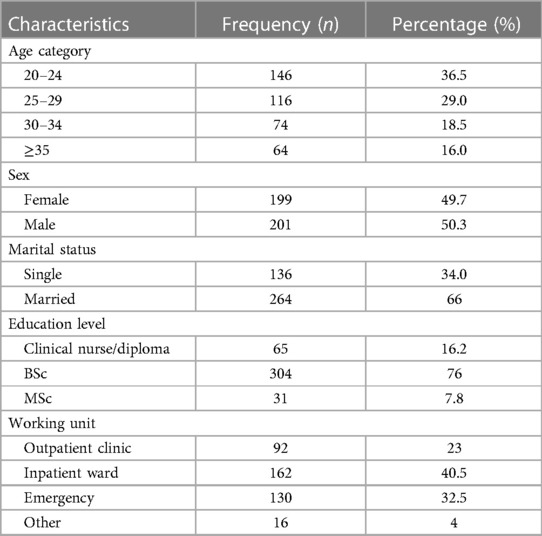

In this study, we included a sample of 415 randomly selected nurses from the hospitals, with a response rate of 96.38%. Nearly half (50.3%) of the participants were male, and 36.5% of them were in the age category of 20–24 years. One-third (66%) of the participants were married. Concerning their academic status, more than three-fourths (76%) of the respondents had bachelor's degrees, and 40.5% of the respondents were working in the inpatient ward at the time of the study (Table 1).

Table 1. The socio-demographic characteristics of nurses who were working at University Teaching Hospitals in the South Region, Ethiopia, 2022, (n = 400).

The magnitude of workplace violence and forms of violence

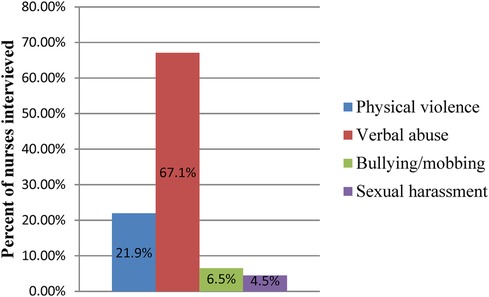

Among the 400 nurses enrolled in this study, 245 (61.3%) had experienced workplace violence during the previous 12 months. The majority of the respondents, 165 (67.07%), reported that they had experienced verbal abuse as a form of workplace violence, while 11 (4.47%) experienced sexual harassment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Magnitude of the different forms of workplace violence among nurses in University Teaching Hospitals in South Nation, Nationalities, and People Region South Ethiopia, April, 2022 (n = 400).

Organizational characteristics of the study participants

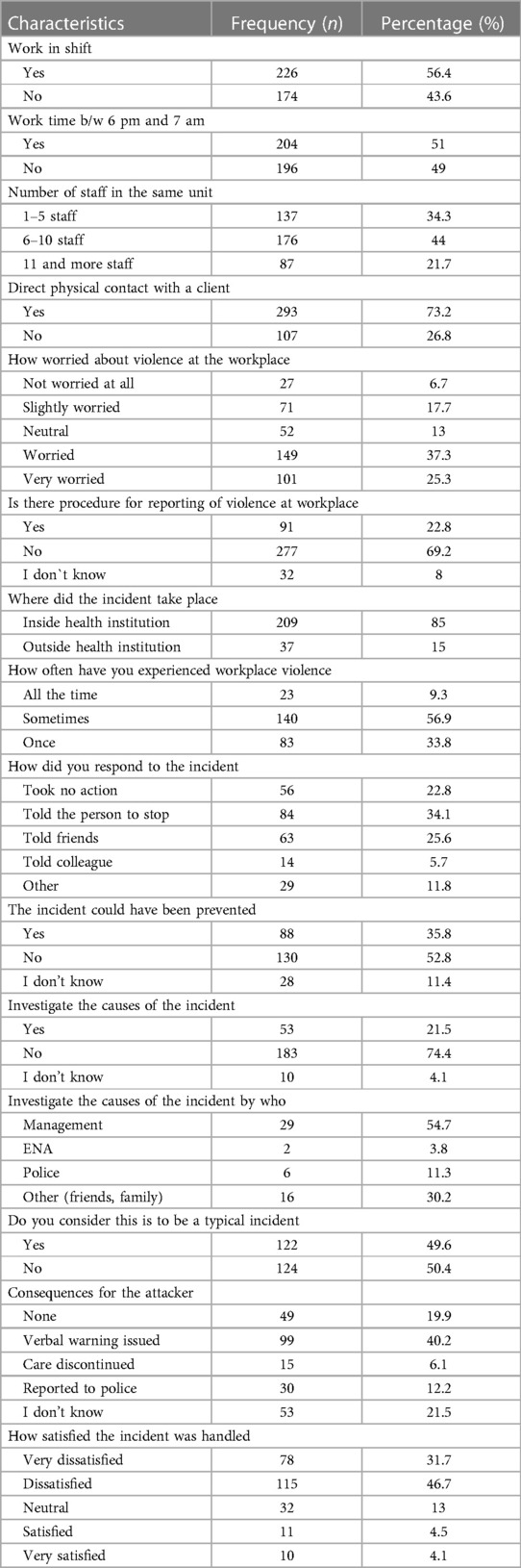

More than half (56.4%) of the nurses were working in shifts. About 51% of the participants` work time was between 6 PM and 7 AM, and 44% of them contained 6–10 nurses in the same working unit. Nearly three-fourths (73.2%) of them had routine direct physical contact with their client. About 37.3% and 25.3% of the participants were worried and very worried about workplace violence, respectively. About 46.7% of the participants were dissatisfied, and 78% of them were very dissatisfied with the way the institutions handled violent incidents (Table 2).

Table 2. Organizational characteristics of nurses who worked at University Teaching Hospitals in South Region, Ethiopia, 2022, (n = 400).

Perpetrator factors

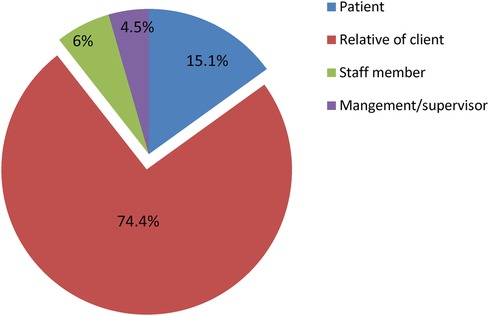

Among the respondents, about 297 (74.4%) of the respondents described perpetrators of workplace violence as mainly patients' relatives, while 18 (4.5%) described them as management or supervisors (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Perpetrators for workplace violence among nurses working in University Teaching Hospitals in South Nation, Nationalities and People Region South Ethiopia, April 2022, (n = 400).

Bivariate and multivariable analysis of factors associated with workplace violence

In the bi-variable logistic regression analysis, the sex of respondents, level of education, work experience, work unit, number of staff in the same working unit, routine direct physical contact with the client, worry about violence in the workplace, and work time between 6 p.m. and 7 a.m. were considered candidate variables for multivariable analysis at a p-value ≤ 0.25. Among the eight variables that were identified in the bi-variable logistic regression analysis, only four variables remained to have a statistically significant association with workplace violence at a 95% CI and a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 in the multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with workplace violence among nurse in University Teaching Hospitals in South Ethiopia, 2022, (n = 400).

Qualitative analysis

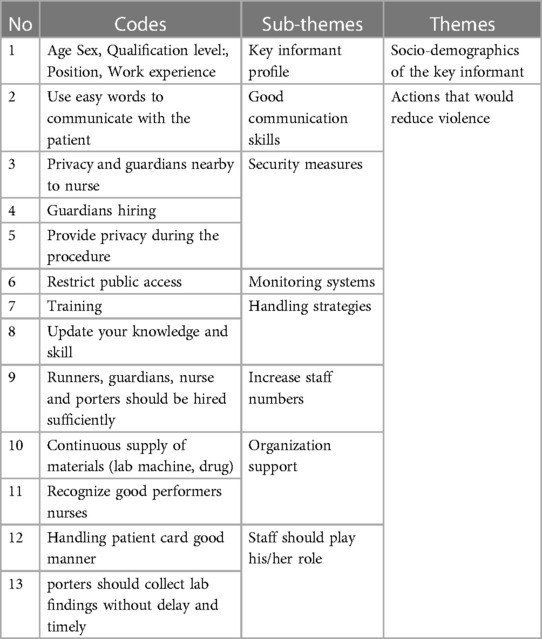

Themes, sub -themes and codes from in-depth interview

After conducting a key informant (KI) interview, the audio recorded data were translated from Amharic to English and transcribed into a text transcript, followed by importing into Open Code version 4.02. Thematic analysis was done using open source code version 4.02. Two themes, eight sub-themes and thirteen codes were created from thematic analysis (Table 4).

Table 4. Themes, sub -themes codes from thematic analysis of in-depth interview key informants in the University Teaching Hospitals in the South Region, Ethiopia, 2022.

Explored qualitative findings of mitigation approaches to workplace

Runners and guardians should be hired sufficiently in health facilities, nurses' job descriptions should be put clearly and the independents' roles of nurses should be well addressed.

A key informant (KI) said, “Runners and guardians should be hired sufficiently in health facilities. Nurses should not do the runner's work. When nurses are at school, they are well educated, both theoretically and practically. But in the work area, there is no well-identified job description and no established system to diagnose, treat, etc. them. So nurses’ job descriptions should be clearly stated, and the independents roles of nurses should be well addressed (we can clerk, take histories, diagnose, and treat). The ENA should give attention to this issue.” All staff should be punctual; card room workers should keep patient cards in a good manner.

KI said, “Every staff member should work through team spirit. As well, the hierarchy should be kept. Every staff member should know their responsibility and perform it accordingly. All staff should be punctual. They should always be available at their workplace during working and duty hours. Card room workers should keep patient cards in a good manner. Also, it is better if card work is computerized. ENA should be strengthened and organized to minimize such violence.” Admin and runners should welcome customers and raise awareness of their rights and duties to patients and their attendants.

KI said, “Admin and runners should welcome customers and give awareness of their rights and duties to patients and their attendants. Physicians should be available on time. They should not be negligent. Every employee should play his or her role.” Nurses should use words that patients understand easily. KI said, “Nurses and physicians should be punctual. Nurses should use words that patients understand easily and never use jargon words.” The nurse should be sufficiently hired, a lab machine should be available in the facility, and porters should collect lab findings without delay and on time.

KI said, “Human resources should be increased in the card room. And nurses should be hired. A lab machine should be available in the facility to reduce referrals for lab investigations. Also, porters should collect lab findings without delay and timely important measures that would reduce violence.” Nurses should have good knowledge and skill. When perform different procedures, privacy should be kept, and it is better if the guardians are nearby nurses. Nurses should be recognized for their good performance. KI said, “Nurses should have good knowledge and skills that challenge others who undermine them. Those measures might reduce violence. When nurses perform different procedures, privacy should be kept, and it is better if the guardians are nearby nurses. Duty rooms for male and female nurses should be separated. Nurses should be recognized for their good performance.” The guardians (security measures) and restricted public access were important to reduce workplace violence.

KI said, “When nurses perform different procedures, privacy should be kept, and it is better if the guardians are nearby nurses.”

Another KI said, “The health facility's security should be strengthened.”

Discussion

In this study, we determined the prevalence and associated factors of workplace violence among nurses in southern Ethiopia. As a result, we found that the prevalence was high and that there were factors significantly associated with workplace violence against nurses. Working in emergency departments, working in inpatient departments, work shifts, the number of nurses in a working unit, and the presence of regular direct physical contact with clients were identified as risk factors of workplace violence in our study.

In the current study, the majority (61.3%) of the respondents had a history of workplace violence within the past 12 months. Nearly similar findings were reported from the studies conducted in the Amhara region, Ethiopia (58.2%) (10), North east Ethiopia (56%) (9), and Eastern Ethiopia (64%) (11), Tunisia (56.3%) (12), Rwanda (58.5%) (13), Gambia (62.1%) (14), Bangladesh (64.2%) (15), Nepal (64.5%) (16), and Istanbul, Turkey (64.1%) (17). However, it was lower than a certain study finding conducted in the Oromia region, Ethiopia, reported at 82.2% (18), in Egypt (80.4%) (19), elsewhere in Iran (82.6%) (20), and China (79.39%) (21). On the other hand, our finding was higher compared to the research results conducted in Hawassa, Ethiopia (29.9%), Gamo Gofa, Ethiopia (43.1%) (22, 23), northwest Ethiopia (26.7%) (8, 24), and elsewhere in China (34%) (25), respectively. The discrepancies may be due to the differences in sample size, socioeconomic characteristics, study designs, and the duration of the studies.

The majority of nurses were worried about workplace violence and dissatisfied with the way the situation was handled in this study. Similar results were reported from the studies conducted in Ethiopia (22, 26). The possible justification could be due to the shortage of guardians (security measures) and a lack of training on effective workplace violence prevention measures. The major perpetrators of workplace violence were patients' relatives and patients, which was similar to the study reports done in the Oromia region, Ethiopia (27), Gamo Gofa zone, Ethiopia (9), and Saudi University Hospitals (4). This similarity could be because nurses interact with patients and their relatives in high-stress circumstances; nurses also have a closer and longer relationship with patients; poor communication between nurses and clients; understaffing; shortage of drugs and supplies; staying a long hour to get a card and when the card is missed; and a shortage of security. In the Ethiopian healthcare system, appointment cards are very important for service provisions. At the first visit, after registration, clients are given appointment cards, and they are expected to bring the cards every time they come for medical services. If they lose it, they are expected to get new card with additional charges, or the person in charge is expected to search their registry manually since they lost the card number, which takes time. This is the point where conflicts arise between clients and healthcare professionals due to delay or charges to get new appointment card. Card rooms require proper organization, adequate staffing, and sufficient space. Furthermore, all patient information must be recorded in the electronic medical catalog system, avoiding any duplication. The card room, when managed properly, facilitates health service delivery by keeping patient information safe and accessible.

In this study, we found that nurses working in emergency departments had 4 times higher odds of experiencing workplace violence compared to those in outpatient departments. This finding is similar to that of a study conducted in Hawassa, Ethiopia (22), Eastern Ethiopia (11), Northwest Ethiopia (24), Rwanda (13), elsewhere in Iran (28), and in Kathmandu, Nepal (29). The possible reasons for the similarity could be due to the fact that emergency rooms are the more stressful and anxious areas for a client, the attendants, and the nurses, where unexpected events like deaths occurred and there was an absence of security. Furthermore, high patient flow, the seriousness of the patient's condition, a high workload, and longer hours of contact with the patient and their relatives might be possible reasons. This study revealed that the odds of workplace violence were 3 times higher among nurses working in inpatient departments compared to those who work in outpatient departments. This finding is supported by the results of studies conducted in Ethiopia (8, 11, 22, 24, 27) and a study done in Kathmandu, Nepal (29). This could be because of client pathologic conditions and waiting for a long time to get the service, which causes them to become irritated and dissatisfied and results in violence against nurses in the workplace.

In the current study, work shift was statistically significantly associated with work place violence against nurses. The odds of workplace violence were 2 times higher among nurses who work night shifts compared to those who work day shifts. This finding is in line with the results of certain studies conducted in Gondar, Ethiopia (10), elsewhere in Egypt (2), KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa (30), and Macau, China (31). This could be due to the fact that the hospital administration's reduced presence and the shortage of staff during the evening and night shifts, which would require individuals to work alone. Overloaded work creates workplace stress, which would increase conflict with patients and visitors.

This study revealed that work units with 1–5 staff nurses were 2.4 times at higher odds of experiencing workplace violence compared to those with 11 or more. Similarly, those who had 6–10 staff nurses were 2.1 times more likely to experience workplace violence compared to those who had 11 or more. This finding is aligned with the results of a study conducted in Amhara, Ethiopia (32). This might be due to dissatisfaction with client care and treatment due to an overloading patient-to-nurse imbalance. Furthermore, the lower number of nurses resulted in a patient care delay, causing patients to get irritated.

Finally, nurses who had regular direct physical contact with the client had a three-fold higher chance of experiencing workplace violence compared to those who did not have direct physical contact. This finding is supported by the results of studies conducted in Thailand (33), and China (34). This could be because the nurses have frequent direct contact with the client, but nurses have a limited independent role in the university teaching hospital system. When nurses instruct patients to wait for physicians, they may encounter aggressive patients, relatives, and attendants in the service area.

Based on our qualitative findings, by increasing the number of nurses in the working unit, this could reduce the shortening of staff during the evening and night shifts, which would reduce individuals working alone. Overloaded work demands place stress on human resources, which would also decrease conflict with patients and visitors. This might also increase satisfaction with client care and treatment due to the patient-to-nurse balance. When the number of nurses on duty is high during a shift, patient care may be fast, causing patients to feel satisfied. Privacy during the procedure, guardians nearby to nurse, possible justification for the guardians (security measures), and the presence of training on effective workplace violence encourage prevention measures, which would reduce workplace violence. Nurses should use easy words to communicate; porters should collect lab findings without delay and timely; provide training in reducing strategies; and update knowledge and skills for important actions that would reduce violence. Possible justification: this may increase interest in the job and feelings of adequate support, ultimately increasing the quality of nursing care.

Limitations of the study

This study is dependent on the nurses’ capability to recall events in the last 12 months before the study, which is subject to recall bias. Because of the sensitive nature of the subjects (sexual harassment in particular), the study results may have suffered from reporting bias, resulting in an underestimation of nurses' exposure to workplace violence. Cultural norms might also cause recall bias since nurses might not disclose violence in order to keep customs that are accepted by the community. Furthermore, we could not establish the cause-and-effect relationship given that it was a cross-sectional study.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the overall prevalence of workplace violence was high in the study area. We have identified factors significantly affecting workplace violence against nurses. Nurses working in emergency departments, nurses working in inpatient departments, the number of nurses in the same working unit (1–5) and (6–10), nurses direct physical contact, and nurses work time between 6 p.m. and 7 a.m. were significantly associated with workplace violence among nurses. Interventions should focus on increasing the number of nurses, establishing private rooms for procedures, providing training on reduction strategies, and updating nurses' knowledge and skills that would help reduce violence.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee of Madda Walabu University, Goba Referral Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

BA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. ZG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. TA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the data collectors and supervisor for their coordinated work during data collection. Our heartfelt gratitude also goes to the study participants for giving valuable information to make our study fruitful.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; BSc, Bachelor of Science; WPV, workplace violence; SNNPR, southern nations, nationalities and peoples region; ILO, International Labor Organization; WHO, World Health Organization; VIF, variance inflation factor; SPSS, statistical software packages for social sciences.

References

1. Oulton JA. The global nursing shortage: an overview of issues and actions. Policy Polit Nurs Prac. (2006) 7(3_suppl):34S–9S. doi: 10.1177/1527154406293968

2. Abbas MA, Fiala LA, Abdel Rahman AG, Fahim AE. Epidemiology of workplace violence against nursing staff in Ismailia Governorate, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. (2024) 85(1–2):29–43.

3. Hassan EE, Amein NM, Ahmed SM. Workplace violence against nurses at Minia District Hospitals. J Health Sci. (2022) 10(1):76–82. doi: 10.17532/jhsci.2020.865

4. Alkorashy HAE, Al Moalad FB. Workplace violence against nursing staff in a Saudi university hospital. Int Nurs Rev. (2022) 63(2):226–32. doi: 10.1111/inr.12242

5. El-Gilany A-H, El-Wehady A, Amr M. Violence against primary health care workers in Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia. J Interpers Violence. (2022) 25(4):716–34. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334395

6. Azodo CC, Ezeja E, Ehikhamenor E. Occupational violence against dental professionals in Southern Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. (2022) 11(3):486–92.

7. ICN I, WHO. Workplace violence in the health sector country case studies research instruments. ILO/ICN/wHO/PSI, (2003) 16:1391–2214.

8. Tiruneh BT, Bifftu BB, Tumebo AA, Kelkay MM, Anlay DZ, Dachew BA. Prevalence of workplace violence in Northwest Ethiopia: a multivariate analysis. BMC Nurs. (2016) 15:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0162-6

9. Weldehawaryat HN, Weldehawariat FG, Negash FG. Prevalence of workplace violence and associated factors against nurses working in public health facilities in Southern Ethiopia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. (2020) 13:1869–77. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S264178

10. Yenealem DG, Yenealem DG, Woldegebriel MK, Olana AT, Mekonnen TH. Violence at work: determinants & prevalence among health care workers, Northwest Ethiopia: an institutional based cross sectional study. Ann Occup Environ Med. (2019) 31(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s40557-019-0288-6

11. Legesse H, Assefa N, Tesfaye D, Birhanu S, Tesi S, Wondimneh F, et al. Workplace violence and its associated factors among nurses working in public hospitals of Eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. (2022) 21(1):300. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-01078-8

12. Kotti N, Dhouib F, Kchaou A, Charfi H, Hammami KJ, Masmoudi ML, et al. Workplace violence experienced by nurses: associated factors and impact on mental health. PAMJ-One Health. (2022) 7(11):2707–800. doi: 10.11604/pamj-oh.2022.7.11.31066

13. Musengamana V, Adejumo O, Banamwana G, Mukagendaneza MJ, Twahirwa TS, Munyaneza E, et al. Workplace violence experience among nurses at a selected university teaching hospital in Rwanda. Pan Afr Med J. (2022) 41(1):64. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2022.41.64.30865

14. Community H. Contribution of socioeconomic factors to the variation in body-mass index in 58 low-income and middle-income countries: an econometric analysis of multilevel data. Lancet Glob Health. (2018) 6:30232–8. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30232-8

15. Latif A, Mallick DR, Akter MK. Workplace violence among nurses at public hospital in Bangladesh).

16. Pandey M, Bhandari TR, Dangal G. Workplace violence and its associated factors among nurses. J Nepal Health Res Counc. (2018) 15(3):235–41. doi: 10.3126/jnhrc.v15i3.18847

17. Gunaydin N, Kutlu Y. Experience of workplace violence among nurses in health-care settings/Saglik kurumlarinda calisan hemsireler arasinda is yeri siddeti deneyimi. J Psychiatr Nurs. (2012) 3(1):1–6. doi: 10.5505/phd.2012.32042

18. Likassa T, Gudissa T, Mariam C. Assessment of factors associated with workplace violence against nurses among referral hospitals of Oromia Regional State. Ethiopia J Health Med Nurs. (2017) 35:22–31.

19. Yahia Mohammed S, Farouk OM, Samir N, Morsy A. Nurses attitudes and reactions regarding workplace violence in obstetrics and gynecological departments. Egyptian J Health Care. (2022) 13(4):323–36. doi: 10.21608/ejhc.2022.260891

20. Heidari A, Kazemi SB, Kabir MJ, Khatirnamani Z, Zargaran MM, Lotfi M, et al. Exposure to workplace violence and related factors among nurses working in hospitals affiliated with golestan university of medical sciences. Depiction of Health. (2023) 14(2):166–78. doi: 10.34172/doh.2023.13

21. Lei Z, Yan S, Jiang H, Feng J, Han S, Herath C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of workplace violence against emergency department nurses in China. Int J Public Health. (2022) 67:1604912. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1604912

22. Fute M, Mengesha ZB, Wakgari N, Tessema GA. High prevalence of workplace violence among nurses working at public health facilities in southern Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. (2015) 14:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12912-015-0062-1

23. Gebrezgi BH, Badi MB, Cherkose EA, Weldehaweria NB, et al. Factors associated with intimate partner physical violence among women attending antenatal care in Shire endaselassie town, tigray, northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study, 2015. Reprod Health. (2015) 14:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0337-y

24. Yenealem DG, Mengistu AM. Fear of violence and working department influences physical aggression level among nurses in northwest Ethiopia government health facilities. Heliyon (2024) 10:2405–8440. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27536

25. Lu J, Ji H, Wang B, Zhang Y, Chen X, Sun M, et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of workplace violence among nurses working at China).

26. Tiruneh BT, Bifftu BB, Tumebo AA, Kelkay MM, Anlay DZ, Dachew BA. Prevalence of workplace violence in Northwest Ethiopia: a multivariate analysis. BMC Nurs. (2016) 15(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0162-6

27. Jira C. Assessment of the prevalence and predictors of workplace violence against nurses working in referral hospitals of oromia regional state, Ethiopia. JIMS8M: J Indian Manag Strat. (2015) 20(1):61–4. doi: 10.5958/0973-9343.2015.00009.5

28. Honarvar B, Ghazanfari N, Raeisi Shahraki H, Rostami S, Lankarani KB. Violence against nurses: a neglected and healththreatening epidemic in the university affiliated public hospitals in Shiraz, Iran. Int J Occup Environ Med. (2019) 10(3):111. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2019.1556

29. Bhusal A, Adhikari A, Singh Pradhan PM. Workplace violence and its associated factors among health care workers of a tertiary hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. PLoS One. (2013) 18(7):e0288680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0288680

30. Pillay L, Siedine K, Coetzee SK, Scheepers N, Ellis SM. The association of workplace violence with personal and work unit demographics, and its impact on nurse outcomes in the KwaZulu-Natal Province. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. (2023) 18:100571. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2023.100571

31. Cheung T, Lee PH, Yip PS. The association between workplace violence and physicians’ and nurses’ job satisfaction in Macau. PLoS One. (2018) 13(12):e0207577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207577

32. Dagnaw EH, Bayabil AW, Yimer TS, Nigussie TS. Working in labor and delivery unit increases the odds of work place violence in Amhara region referral hospitals: cross-sectional study. PLoS One. (2021) 16(10):e0254962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254962

33. Chaiwuth S, Chanprasit C, Kaewthummanukul T, Chareosanti J, Srisuphan W, Stone TE. Prevalence and risk factors of workplace violence among registered nurses in tertiary hospitals. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res Thail. (2017) 24(4):538–52.

Keywords: nurses, workplace, violence, South Ethiopia, associated factors

Citation: Anose BH, Roba AE, Gemechu ZR, Heliso AZ, Negassa SB and Ashamo TB (2024) Workplace violence and its associated factors among nurses working in university teaching hospitals in Southern Ethiopia: a mixed approach. Front. Environ. Health 3:1385411. doi: 10.3389/fenvh.2024.1385411

Received: 12 February 2024; Accepted: 17 April 2024;

Published: 9 May 2024.

Edited by:

Maria Jose Rosa, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United StatesReviewed by:

Alp Ergör, Dokuz Eylül University, TürkiyePaolo Marco Riela, National Research Council (CNR), Italy

© 2024 Anose, Roba, Gemechu, Heliso, Negassa, and Ashamo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Teshale Belayneh Ashamo dGVzaGFsZWJlQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Bereket Hegeno Anose1

Bereket Hegeno Anose1 Teshale Belayneh Ashamo

Teshale Belayneh Ashamo