94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Chem., 07 April 2021

Sec. Catalytic Remediation

Volume 2 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvc.2021.653402

This article is part of the Research TopicCatalytic Elimination of Atmospheric Pollution via Novel CatalystsView all 5 articles

Vacuum-drying and freeze-drying were adopted to improve the catalytic activity of Ce0.5Pr0.5O2 for soot combustion. The specific surface area and pore volume of the as-prepared Ce0.5Pr0.5O2 were greatly increased compared to the counterpart using the common drying method. Furthermore, the redox performance and the oxidation ability for soot were enhanced, as demonstrated by H2-TPR and soot-TPR. Thus, lower combustion temperatures and higher intrinsic activity were obtained. This work demonstrated that simply changing the drying process of precipitates can be served as a paradigm to improve the structure and catalytic performance.

Soot particulates emitted from diesel engines have caused seriously deleterious effects on human health and environment (Wei et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2014; Fino et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2019; Tsai et al., 2020). The catalytic combustion technique combined with diesel particulate filters (DPFs) (Kumar et al., 2012; Feng et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2019; Fang et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020) has been considered as one of the most efficient ways to eliminate soot, of which the key point is to explore a highly active catalyst.

CeO2 has been extensively used as an excellent catalyst for soot combustion due to its remarkable oxygen storage capacity (OSC) and redox property (Piumetti et al., 2015). Doping with metal ions can further improve its catalytic performance (Liu et al., 2008; Fu et al., 2010; Muroyama et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2020). In particular, doping of rare earth elements can induce distortion of the CeO2 lattice, leading to the formation of more oxygen vacancies, thereby improving the oxygen storage/release property and redox capability (Aneggi et al., 2012). Bueno-López et al. (Bueno-Lopez et al., 2005) reported that doping of La3+ increases surface area and redox properties of CeO2, and thus enhances its catalytic soot combustion activity. Hernández-Giménez et al. (Hernández-Giménez et al., 2013) found that by doping of Nd, the soot combustion activity of Ce-Zr mixed oxide can be improved. Impressively, Pr-doped CeO2 was shown to be more active than other Ce-based oxides (Krishna et al., 2007; Bueno-López, 2014; Guillén-Hurtado et al., 2015). Therein, Ce0.5Pr0.5O2 with the highest surface area and smallest particle size is even better than a reference Pt-based commercial catalyst (Guillén-Hurtado et al., 2015). The enhancement of Pr and La doping for soot combustion was attributed to the increased lattice oxygen activity (Harada et al., 2014).

So far, coprecipitation (Katta et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2012; Venkataswamy et al., 2014; Muroyama et al., 2015; Devaiah et al., 2016), hydrothermal (Nakagawa et al., 2015; Piumetti et al., 2015), sol–gel (Oliveira et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2015; Alcalde-Santiago et al., 2019), microemulsion (Fan et al., 2017), and solid-phase grinding have been used to prepare CeO2-based oxides. However, the drying methods are scarcely discussed. Generally, improving the drying process can decrease the agglomeration of catalyst particles and have a positive impact on catalytic activity (Fan et al., 2014). In this work, vacuum-drying and direct freeze-drying were adopted to coprecipitated Ce0.5Pr0.5O2 and compared with the common drying method. XRD, BET, H2-TPR, and soot-TPR were used to characterize the physiochemical properties of the as-prepared catalysts so that the effects of drying treatment on the catalytic soot combustion performance can be deduced.

1.2593 g of Ce(NO3)3⋅6H2O and 1.2593 g of Pr(NO3)3⋅6H2O were dissolved in 10 ml deionized water at room temperature. NH3⋅H2O was added dropwise under vigorous stirring until the pH reached ∼9. Then, the precipitates were kept at room temperature for 24 h, followed by filtration and washing with deionized water until a pH of 7 was attained. After that, the precipitates were dried at 100°C for 12 h and finally calcined at 500°C for 2 h in the muffle furnace with the heating rate of 1°C/min. The sample obtained is denoted as CPO.

Based on the above method, the drying process was improved. For vacuum-drying, the precipitate was immersed in 250 ml of ethanol for 24 h under static conditions for the sake of substituting water with ethanol. Subsequently, the precipitate was filtered to remove alcohol and then dried at 80°C for 12 h in a vacuum oven. Finally, the sample was calcined at 500°C for 2 h in the muffle furnace with a heating rate of 1°C/min. The sample obtained is denoted as CPO-E. For freeze-drying, the precipitate was placed in a freeze dryer and dried for 24 h. Finally, the sample was calcined at 500°C for 2 h in the muffle furnace with a heating rate of 1°C/min. The sample obtained is denoted as CPO-F.

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns were measured on a D8FOCUS powder X-ray diffraction instrument (Bruker AXS, Germany) using 40 kV as tube voltage and 40 mA as tube current.

Surface area and pore size distribution were determined by N2 adsorption/desorption at 77 K using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method with a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 instrument after out-gassing for 5 h at 300°C prior to analysis.

Temperature-programmed reduction with H2 (H2-TPR) experiments were performed in a quartz reactor with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) to monitor H2 consumption. A 50 mg sample was pretreated in situ for 30 min at 200°C in a flow of O2 (30 ml/min) and cooled to room temperature in the presence of O2. After purging in N2, TPR was conducted at 10°C/min up to 900°C in a 30 ml/min flow of 5 vol.% H2 in N2. To quantify the total amount of H2 consumption, CuO was used as a calibration reference.

Soot temperature–programmedreduction (soot-TPR) experiments were performed in a quartz reactor consistent with the activity test dosage. 50 mg sample of the soot–catalyst mixture and 100 mg of quartz sand were pretreated in a flow of He (100 ml/min) at 200°C for 30 min to remove adsorbed species. After cooling to room temperature, the temperature was also programmed in a He atmosphere under the condition of a heating rate of 5°C/min, reaching 850°C. CO2 during the reaction was detected by mass spectrometry (MS, OminiStar 200, Balzers).

Temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO) reactions were conducted in a fixed bed micro-reactor. Printex-U from Degussa is used as the model soot. Two conditions (tight and loose contact) were employed in this study, in which 45 mg of catalyst and 5 mg of soot were used. In tight contact conditions, soot was mixed with the catalyst in an agate mortar for 30 min to obtain a homogeneous mixture. In loose contact conditions, the catalyst–soot mixture was added into a small flask and shaken for 24 h. 50 mg sample of the soot–catalyst mixture was pretreated in a flow of He (100 ml/min) at 200°C for 30 min to remove adsorbed species. After cooling to room temperature, a gas flow with 5 vol.% O2 in He was introduced, and then TPO was started at a heating rate of 5°C/min until reaching 750°C. The effluent gases were monitored online using a gas chromatograph (GC, SP-6890, Shandong Lunan Ruihong Chemical Instrument Corporation, China) fitted with a methanator. The activity for soot combustion was evaluated by Tm, the temperature corresponding to the maximum soot combustion rate. The selectivity to CO2 (SCO2) is defined as the percentage CO2 in the outlet concentration divided by the sum of the CO2 and CO outlet concentrations.

The intrinsic activity, turnover frequency (TOF), is measured by an isothermal anaerobic titration with soot as a probe molecule, as suggested by us previously (Zhang et al., 2010). A 50 mg mixture of catalyst and soot (9:1) below 300 mesh was diluted with 100 mg silica (below 300 mesh). After pretreatment in a flow of He (100 ml/min) at 120 °C for 20 min, a gas flow with 5 vol.% O2 in He (200 ml/min) was introduced. The isothermal reaction rates were detected at 280°C when the soot conversion is stable and low but sufficient for analysis purposes. When comparable soot conversions were reached for all the samples, O2 was replaced with He. The transient decay in concentrations from the steady state was monitored using a gas chromatograph. The number of active redox sites available to soot under these reaction conditions can be quantified by integrating the diminishing rate of CO2 formation over time.

XRD patterns show that all the as-prepared samples are indexed to the structure of fluorite CeO2 (JCPDS 43–1002), and no other peaks were found (Figure 1), implying the formation of CePr solid solution due to the similar ionic radius of Ce4+ (0.97 Å) with Pr4+ (0.96 Å). This confirms that changing drying methods does not change the phase structure of the CePr composite oxides. Additionally, it is noted that the intensity of the diffraction peaks of CPO-E and CPO-F is lower than those of CPO, suggesting the lower crystallinity or more defects/vacancies for CPO-E and CPO-F, which would benefit the redox property and catalytic activity (Martínez-Munuera et al., 2019).

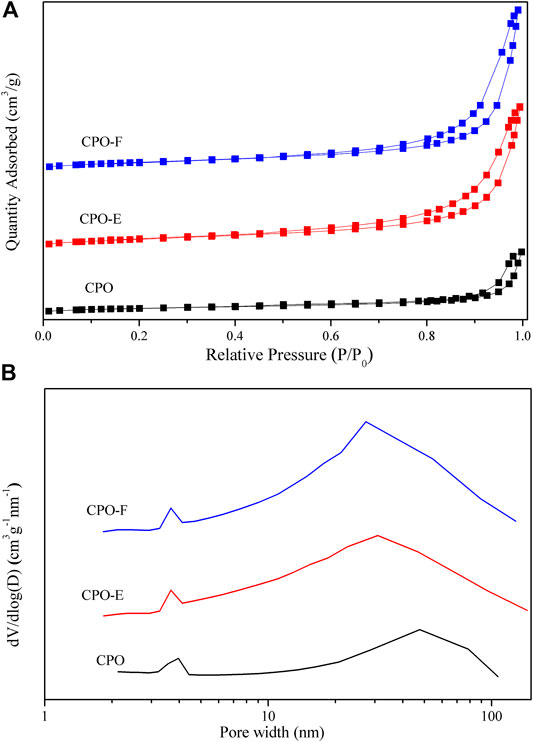

Figure 2 shows N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms and pore distribution curves. The type II isotherms with a type H3 hysteresis loop in the relative pressure (P/P0) range of ∼0.4–1.0 are observed (Figure 2A), indicating aggregates of plate-like particles with slit-shaped pores (Aneggi et al., 2012; Fan et al., 2014). Furthermore, both mesopores and macropores are detected (Figure 2B). However, the pore size distribution with a shift to lower values was observed for CPO-E and CPO-F compared with CPO, while the BET surface areas of CPO-E and CPO-F are nearly double that of CPO, and pore volumes more than triple (Table 1), confirming the looser texture and abundant pores for the former two samples derived from the vacuum- and freeze-drying processes. This is possibly due to the loosely aggregated morphology under vacuum/freeze-drying process resulting in the elimination of surface tension effects.

FIGURE 2. N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms (A) and pore distribution curves (B) for CPO, CPO-E, and CPO-F.

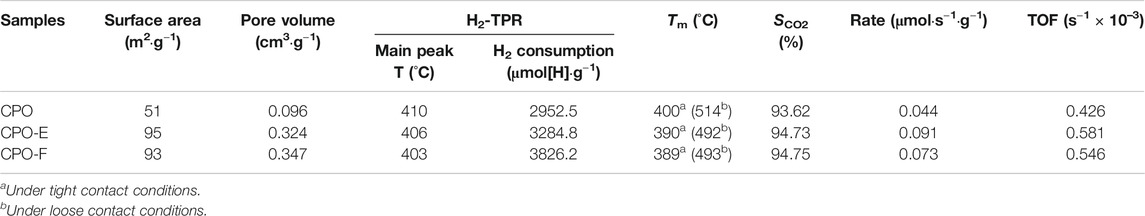

TABLE 1. Texture properties, hydrogen consumption, and catalytic soot oxidation activity of samples.

The redox properties of the catalysts were investigated by H2-TPR. As shown in Figure 3, two H2 consumption peaks, a prominent one with a should and a small one above 500°C, were observed, which can be attributed to the reduction of surface and subsurface Ce4+ and Pr4+ reduction (Krishna et al., 2007; Guillén-Hurtado et al., 2015). Importantly, the first peak appears earlier for CPO-E and CPO-F than for CPO, indicating the higher reducibility of CePr oxide solid solutions using vacuum/freeze-drying methods. Furthermore, the H2 amounts consumed for CPO-E and CPO-F were much higher than those consumed for CPO (Table 1), suggesting that not only the reactivity of active oxygen but also the amount involved are improved.

To be more realistic, soot was used as a probe agent for TPR reactions (Figure 4). Similar with H2-TPR, two CO2 production peaks are observed. Furthermore, the lower temperature of the first reduction peaks for CPO-E and CPO-F in comparison with CPO confirmed the increase of surface lattice oxygen activity for soot combustion (Machida et al., 2008; Aneggi et al., 2012; Harada et al., 2014). On the other hand, the low-temperature reducibility of catalysts can be evaluated using the initial soot consumption rates. The soot consumption rates of CPO-E and CPO-F are much higher than those of CPO, confirming the stronger ability of active oxygen species in CPO-E and CPO-F for oxidizing soot.

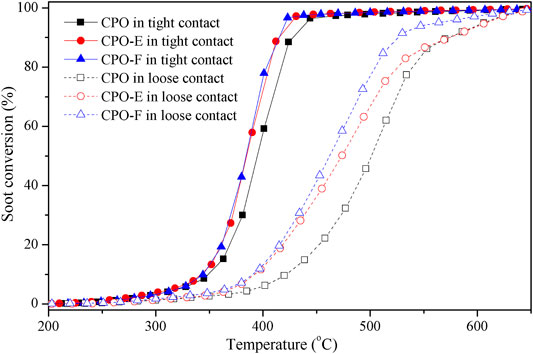

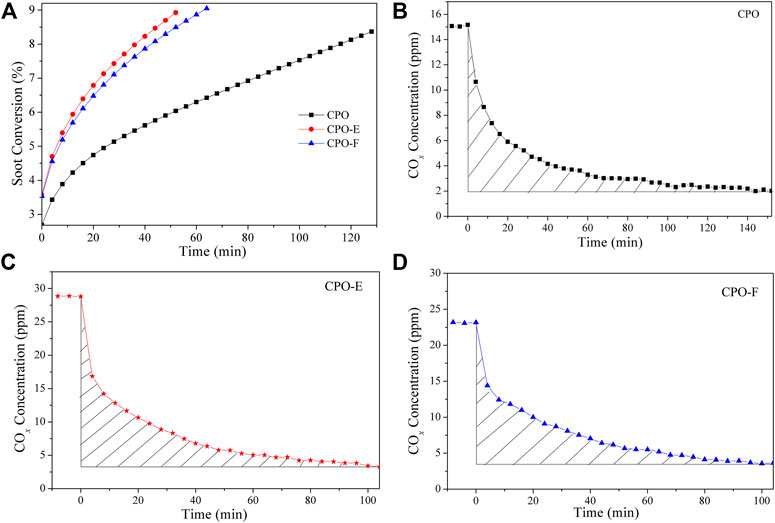

Figure 5 shows soot combustion conversion profiles under tight and loose contact conditions in O2 atmosphere. Both CPO-E and CPO-F show lower Tm and higher SCO2 than CPO in the tight contact conditions. For the sake of disclosing the differentiation in intrinsic activity, isothermal reactions at 280°C and anaerobic titration tests were performed (Li et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2010), from which the reaction rates, the amounts of active oxygen, and the TOF values can be obtained (Figure 6). As listed in Table 1, higher reaction rates and TOF values were achieved on CPO-E and CPO-F, which is consistent with the results of H2-TPR (Figure 3) and soot-TPR (Figure 4). In the loose contact conditions, similar activity results were observed, but all Tm shift to higher temperatures than that in the tight contact conditions (Figure 5). Clearly, the activity improvement after vacuum-drying and freeze-drying is more evident, because the difference of Tm between CPO-E/CPO-F and CPO is 20°C, while under the tight contact conditions, only 10°C was detected (Table 1). This could be attributed to bigger pore volumes and surface areas of CPO-E and CPO-F (Table 1), improving soot dispersion on catalysts and thus the contact efficiency of soot with catalyst under loose contact conditions, as well as facilitating fast oxygen delivery (Martínez-Munuera et al., 2019).

FIGURE 5. Soot conversion under tight and loose contact between catalysts and soot in 5 vol.% O2 in He.

FIGURE 6. Soot consumed as a function of time at 280°C over CPO, CPO-E, and CPO-F (A), COx concentrations as a function of time at 280°C over CPO (B), CPO-E (C), and CPO-F (D) before and after O2 is removed from the reactant feed. The curve slopes between three dot lines in (A) represent reaction rates.

Vacuum-drying and freeze-drying were used to improve the activity of Ce0.5Pr0.5O2, a promising soot combustion catalyst. Lower crystallinity, higher surface area, larger pore volume, and stronger redox properties were obtained compared to the counterpart using the common drying method. Therefore, lower soot oxidation temperatures and higher intrinsic activity were achieved. It is a good paradigm for catalysts to enhance catalytic performance simply by changing drying methods during the preparation process.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

QL designed and performed experiments. YS prepared the samples used in this work. XL helped synthesizing catalysts. YL and NZ helped characterizing samples. QL, YX, and ZZ discussed the results. QL and ZZ wrote the manuscript and supervised the project.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 21876061 and 22076062), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2020MB090), and science and technology projects of the University of Jinan (No. XKY1905).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Alcalde-Santiago, V., Bailón-García, E., Davó-Quiñonero, A., Lozano-Castelló, D., and Bueno-López, A. (2019). Three-dimensionally ordered macroporous PrOx: an improved alternative to ceria catalysts for soot combustion. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 248, 567–572. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.10.049

Aneggi, E., De Leitenburg, C., and Trovarelli, A. (2012). On the role of lattice/surface oxygen in ceria-zirconia catalysts for diesel soot combustion. Catal. Today 181, 108–115. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2011.05.034

Bueno-Lopez, A., Krishna, K., Makkee, M., and Moulijn, J.A. (2005). Enhanced soot oxidation by lattice oxygen via La3+-doped CeO2. J. Catal. 230, 237–248. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2004.11.027

Bueno-López, A. (2014). Diesel soot combustion ceria catalysts. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 146, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.02.033

Cheng, Y., Song, W., Liu, J., Zheng, H., Zhao, Z., Xu, C., et al. (2017). Simultaneous NOx and particulate matter removal from diesel exhaust by hierarchical Fe-doped Ce-Zr oxide. ACS Catal. 7, 3883–3892. doi:10.1021/acscatal.6b03387

Cui, B., Zhou, L., Li, K., Liu, Y.-Q., Wang, D., Ye, Y., et al. (2020). Holey Co-Ce oxide nanosheets as a highly efficient catalyst for diesel soot combustion. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 267, 118670. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.118670

Devaiah, D., Thrimurthulu, G., Smirniotis, P. G., and Reddy, B. M. (2016). Nanocrystalline alumina-supported ceria-praseodymia solid solutions: structural characteristics and catalytic CO oxidation. RSC Adv. 6, 44826–44837. doi:10.1039/c6ra06679h

Fan, Y., Wang, Z., Xin, Y., Li, Q., Zhang, Z., and Wang, Y. (2014). Significant improvement of thermal stability for CeZrPrNd oxides simply by supercritical CO2 drying. PLoS One 9, e88236. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088236

Fan, L., Xi, K., Zhou, Y., Zhu, Q., Chen, Y., and Lu, H. (2017). Design structure for CePr mixed oxide catalysts in soot combustion. RSC Adv. 7, 20309–20319. doi:10.1039/c6ra28722k

Fang, F., Zhao, P., Feng, N., Wan, H., and Guan, G. (2020). Surface engineering on porous perovskite-type La0.6Sr0.4CoO3-δ nanotubes for an enhanced performance in diesel soot elimination. J. Hazard. Mater. 399, 123014. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123014

Feng, N., Chen, C., Meng, J., Wu, Y., Liu, G., Wang, L., et al. (2016). Facile synthesis of three-dimensionally ordered macroporous silicon-doped La0.8K0.2CoO3 perovskite catalysts for soot combustion. Catal. Sci. Technol. 6, 7718–7728. doi:10.1039/c6cy00677a

Fino, D., Bensaid, S., Piumetti, M., and Russo, N. (2016). A review on the catalytic combustion of soot in diesel particulate filters for automotive applications: from powder catalysts to structured reactors. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 509, 75–96. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2015.10.016

Fu, M., Yue, X., Ye, D., Ouyang, J., Huang, B., Wu, J., et al. (2010). Soot oxidation via CuO doped CeO2 catalysts prepared using coprecipitation and citrate acid complex-combustion synthesis. Catal. Today 153, 125–132. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2010.03.017

Guillén-Hurtado, N., García-García, A., and Bueno-López, A. (2015). Active oxygen by Ce-Pr mixed oxide nanoparticles outperform diesel soot combustion Pt catalysts. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 174-175, 60–66. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.02.036

Harada, K., Oishi, T., Hamamoto, S., and Ishihara, T. (2014). Lattice oxygen activity in Pr- and La-doped CeO2 for low-temperature soot oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 559–568. doi:10.1021/jp410996k

Hernández-Giménez, A. M., Xavier, L. P. d. S., and Bueno-López, A. (2013). Improving ceria-zirconia soot combustion catalysts by neodymium doping. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 462-463, 100–106. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2013.04.035

Jin, B., Zhao, B., Liu, S., Li, Z., Li, K., Ran, R., et al. (2020). SmMn2O5 catalysts modified with silver for soot oxidation: dispersion of silver and distortion of mullite. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 273, 119058. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119058

Katta, L., Sudarsanam, P., Thrimurthulu, G., and Reddy, B. M. (2010). Doped nanosized ceria solid solutions for low temperature soot oxidation: zirconium versus lanthanum promoters. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 101, 101–108. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.09.012

Krishna, K., Bueno-López, A., Makkee, M., and Moulijn, J. A. (2007). Potential rare-earth modified CeO2 catalysts for soot oxidation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 75, 210–220. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.04.009

Kumar, P. A., Tanwar, M. D., Bensaid, S., Russo, N., and Fino, D. (2012). Soot combustion improvement in diesel particulate filters catalyzed with ceria nanofibers. Chem. Eng. J. 207-208, 258–266. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2012.06.096

Li, X., Wei, S., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., Su, Q., et al. (2011). Quantification of the active site density and turnover frequency for soot combustion with O2 on Cr doped CeO2. Catal. Today 175, 112–116. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2011.03.057

Lim, C.-B., Kusaba, H., Einaga, H., and Teraoka, Y. (2011). Catalytic performance of supported precious metal catalysts for the combustion of diesel particulate matter. Catal. Today 175, 106–111. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2011.03.062

Lin, F., Wu, X., Liu, S., Weng, D., and Huang, Y. (2013). Preparation of MnOx-CeO2-Al2O3 mixed oxides for NOx-assisted soot oxidation: activity, structure and thermal stability. Chem. Eng. J. 226, 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2013.04.006

Lin, X., Li, S., He, H., Wu, Z., Wu, J., Chen, L., et al. (2018). Evolution of oxygen vacancies in MnOx-CeO2 mixed oxides for soot oxidation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 223, 91–102. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.06.071

Liu, J., Zhao, Z., Wang, J., Xu, C., Duan, A., Jiang, G., et al. (2008). The highly active catalysts of nanometric CeO2-supported cobalt oxides for soot combustion. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 84, 185–195. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2008.03.017

Machida, M., Murata, Y., Kishikawa, K., Zhang, D., and Ikeue, K. (2008). On the reasons for high activity of CeO2 catalyst for soot oxidation. Chem. Mater. 20, 4489–4494. doi:10.1021/cm800832w

Martínez-Munuera, J. C., Zoccoli, M., Giménez-Mañogil, J., and García-García, A. (2019). Lattice oxygen activity in ceria-praseodymia mixed oxides for soot oxidation in catalysed gasoline particle filters. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 245, 706–720. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.12.076

Muroyama, H., Hano, S., Matsui, T., and Eguchi, K. (2010). Catalytic soot combustion over CeO2-based oxides. Catal. Today 153, 133–135. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2010.02.015

Muroyama, H., Asajima, H., Hano, S., Matsui, T., and Eguchi, K. (2015). Effect of an additive in a CeO2-based oxide on catalytic soot combustion. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 489, 235–240. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2014.10.039

Nakagawa, K., Ohshima, T., Tezuka, Y., Katayama, M., Katoh, M., and Sugiyama, S. (2015). Morphological effects of CeO2 nanostructures for catalytic soot combustion of CuO/CeO2. Catal. Today 246, 67–71. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2014.08.005

Oliveira, C. F., Garcia, F. A. C., Araújo, D. R., Macedo, J. L., Dias, S. C. L., and Dias, J. A. (2012). Effects of preparation and structure of cerium-zirconium mixed oxides on diesel soot catalytic combustion. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 413-414, 292–300. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2011.11.020

Piumetti, M., Bensaid, S., Russo, N., and Fino, D. (2015). Nanostructured ceria-based catalysts for soot combustion: investigations on the surface sensitivity. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 165, 742–751. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.10.062

Ren, W., Ding, T., Yang, Y., Xing, L., Cheng, Q., Zhao, D., et al. (2019). Identifying oxygen activation/oxidation sites for efficient soot combustion over silver catalysts interacted with nanoflower-like hydrotalcite-derived CoAlO metal oxides. ACS Catal. 9, 8772–8784. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b01897

Tsai, Y.-C., Nhat Huy, N., Lee, J., Lin, Y.-F., and Lin, K.-Y. A. (2020). Catalytic soot oxidation using hierarchical cobalt oxide microspheres with various nanostructures: insights into relationships of morphology, property and reactivity. Chem. Eng. J. 395, 124939. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.124939

Venkataswamy, P., Jampaiah, D., Rao, K. N., and Reddy, B. M. (2014). Nanostructured Ce0.7Mn0.3O2−δand Ce0.7Fe0.3O2−δ solid solutions for diesel soot oxidation. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 488, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2014.09.014

Wang, Y., Wang, J., Chen, H., Yao, M., and Li, Y. (2015). Preparation and NOx -assisted soot oxidation activity of a CuO-CeO2 mixed oxide catalyst. Chem. Eng. Sci. 135, 294–300. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2015.03.024

Wei, Y., Liu, J., Zhao, Z., Chen, Y., Xu, C., Duan, A., et al. (2011). Highly active catalysts of gold nanoparticles supported on three-dimensionally ordered macroporous LaFeO3 for soot oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 2326–2329. doi:10.1002/anie.201006014

Wei, Y., Zhao, Z., Liu, J., Liu, S., Xu, C., Duan, A., et al. (2014). Multifunctional catalysts of three-dimensionally ordered macroporous oxide-supported Au@Pt core-shell nanoparticles with high catalytic activity and stability for soot oxidation. J. Catal. 317, 62–74. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2014.05.014

Yang, Z., Hu, W., Zhang, N., Li, Y., and Liao, Y. (2019). Facile synthesis of ceria-zirconia solid solutions with cubic-tetragonal interfaces and their enhanced catalytic performance in diesel soot oxidation. J. Catal. 377, 98–109. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2019.06.029

Yu, X., Wang, L., Chen, M., Fan, X., Zhao, Z., Cheng, K., et al. (2019). Enhanced activity and sulfur resistance for soot combustion on three-dimensionally ordered macroporous-mesoporous MnxCe1‐xOδ/SiO2 catalysts. Appl. Catal. B. 254, 246–259. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.04.097

Zhang, G., Zhao, Z., Liu, J., Jiang, G., Duan, A., Zheng, J., et al. (2010). Three dimensionally ordered macroporous Ce1‐xZrxO2 solid solutions for diesel soot combustion. Chem. Commun. 46, 457–459. doi:10.1039/b915027g

Zhang, Z., Han, D., Wei, S., and Zhang, Y. (2010). Determination of active site densities and mechanisms for soot combustion with O2 on Fe-doped CeO2 mixed oxides. J. Catal. 276, 16–23. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2010.08.017

Zhao, H., Li, H., Pan, Z., Feng, F., Gu, Y., Du, J., et al. (2020). Design of CeMnCu ternary mixed oxides as soot combustion catalysts based on optimized Ce/Mn and Mn/Cu ratios in binary mixed oxides. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 268, 118422. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118422

Keywords: soot oxidation, Ce0.5Pr0.5O2, vacuum-drying, freeze-drying, intrinsic activity

Citation: Li Q, Su Y, Liu X, Lv Y, Zhang N, Xin Y and Zhang Z (2021) Improved Intrinsic Activity of Ce0.5Pr0.5O2 for Soot Combustion by Vacuum/Freeze-Drying. Front. Environ. Chem. 2:653402. doi: 10.3389/fenvc.2021.653402

Received: 14 January 2021; Accepted: 11 February 2021;

Published: 07 April 2021.

Edited by:

Dengsong Zhang, Shanghai University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Li, Su, Liu, Lv, Zhang, Xin and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qian Li, Y2htX2xpcWlhbkB1am4uZWR1LmNu; Zhaoliang Zhang, Y2htX3poYW5nemxAdWpuLmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.