94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Archaeol., 20 December 2024

Sec. Archaeological Isotope Analysis

Volume 3 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fearc.2024.1461150

Roshan Paladugu1*

Roshan Paladugu1* Alessandra Celant2

Alessandra Celant2 Gopesh Jha3

Gopesh Jha3 Federico Di Rita2

Federico Di Rita2 Elisa de Sousa4

Elisa de Sousa4 Ana Margarida Arruda4

Ana Margarida Arruda4 Anne-France Maurer5

Anne-France Maurer5 Donatella Magri2

Donatella Magri2 Cristina Barrocas Dias5,6

Cristina Barrocas Dias5,6Castro Marim is an Iron Age site from the Algarve region, Portugal. The earliest evidence of settlement, from the Late Bronze Age, dates to the 9th century BCE, with the Phoenician-Punic period dating from the 7th to the 3rd century BCE. This study focuses on the stable isotope analysis of plant and collagen of faunal remains to reconstruct cultivation and husbandry practices. Barley was the most abundantly cultivated cereal crop. The stable isotope results of barley indicate that the primary source of water was natural precipitation and the soil nitrogen was enriched through manuring. Δ13C and δ15N isotope values of stone pine support the previously suggested human management hypothesis. The differences from stable isotope data of domesticated fauna indicate a diverse management strategy for different species based on their economic importance to capitalize from the animal by-products such as wool and dairy products.

The southern Portuguese coast experienced extensive colonization by the Phoenicians, a culturally homogeneous group of politically independent city-states from the Near East, during the 9th century BCE. Their settlements, originating from the Levant (modern-day Lebanon), were part of a broader westward expansion driven by the need for metalliferous resources (Aubet, 1987, 2001; Markoe, 2005; Arruda, 2009; Dietler, 2009; Gomes and Arruda, 2018; Eshel et al., 2019; Quinn, 2019). Phoenicians, through the establishment of agreements and negotiations with the native communities, mined the Iberian Pyrite belt for silver, tin, lead, and copper in the early 8th century BCE (Renzi et al., 2012; Eshel et al., 2019; Wood et al., 2019). The intense and prolonged settlements along the Southern Portuguese coast cannot simply be explained by the quest for mineral sources, primarily because a considerable part of them are situated in locations with neither metallogenic minerals nor pre-existing indigenous settlements. Other factors influencing settlement density include agricultural resources (Wagner and Alvar, 1989, 2003), exploitation of marine resources, such as salt (Manfredi, 1992) and Tyrrhenian Purple (Uriel, 2000), timber (Treumann, 1998, 2009), and labor force (Arrastio, 1999, 2000). Agriculture appears to have played a crucial role in sustaining Phoenician communities along the southern Portuguese coast, particularly in ensuring stable food supplies to support both the population and industrial activities due to the region's natural fertility and rich mineral veins (Neville, 1998; Arruda, 2003, 2009; Roller, 2014). The Phoenician traders had to ensure stable sources of food for the population in addition to their industrial activities. While the Phoenician metal exploitation perspective has been studied, the agricultural aspects have comparatively received little attention so far.

This study seeks to illuminate the farming strategies and animal husbandry practices during the Phoenician-Punic period in Portugal, focusing specifically on Castro Marim. By integrating traditional zooarchaeological and archaeobotanical analyses with advanced botanical studies, stable isotope analysis, and Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS), we aim to deepen our understanding of the agricultural systems that supported Phoenician settlements. Previous studies of Phoenician agriculture have largely centered on zooarchaeological and archaeobotanical approaches, offering valuable insights into the introduction of new plant species, arboreal exploitation, meat consumption, hunting patterns, animal preferences, and the use of secondary animal products. While these traditional methods provide essential context, modern molecular techniques are now crucial for refining these findings and broadening our analytical scope, allowing for a more detailed picture of Phoenician agricultural practices.

The primary objectives of this study are to identify both cultivated and wild plant species and reconstruct ancient crop management strategies through stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis, shedding light on irrigation practices and manuring regimes; and to investigate animal husbandry practices using ZooMS and stable isotope analysis of faunal bone collagen, focusing on carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur isotopes. The sulfur isotopes are a preliminary tool to trace the local vs. non-local origins of the livestock, as Phoenician trade networks likely involved the transport of animals across the Mediterranean. To achieve these goals, macro-botanical analysis of charred plant remains was conducted to identify species used by the Phoenicians, and stable isotope analysis helped reconstruct agricultural techniques such as watering and fertilization. ZooMS, crucial for differentiating between morphologically similar species like sheep and goats, revealed distinct animal management strategies. By analyzing the δ13C and δ15N values of wild and domestic fauna, we established ecological baselines and uncovered evidence of foddering and herding practices. Additionally, sulfur isotope (δ34S) values provided insights into the mobility of livestock, distinguishing between local and non-local origins. This integrated approach improves the resolution of pre-existing research and tries to develop a comprehensive understanding of how Phoenician farming and husbandry practices.

Skeletal elements of goats and sheep are a common occurrence in archaeological contexts. A significant issue plaguing comparative husbandry studies between sheep and goats is the overlap of skeletal elements (Boessneck et al., 1964; Schramm, 1967; Payne, 1969). Zooarchaeology by mass spectrometry applies peptide mass fingerprinting to identify archaeological remains (Buckley et al., 2009). The main protein used for this is collagen, which is the most abundant protein in bone. Due to sequence differences in collagen of sheep and goat, ZooMS is able to differentiate between these two species, which is often not possible using standard morphological analysis (Buckley et al., 2010).

Stable isotope (δ13C, and δ15N) analyses of faunal bone collagen are valuable means of reconstructing foddering practices and other animal husbandry aspects (Price et al., 2017). The variation in δ13C of terrestrial organisms is determined by the primary producers' photosynthetic pathway, distinguished as C3, C4, and CAM plants (DeNiro and Epstein, 1978; Farquhar et al., 1989; Tieszen, 1991; Kohn, 2010). Plant species are overwhelmingly C3 in nature, including most cultivated plants such as barley, wheat, oats, and other wild edible plants (Fernández-Crespo et al., 2019). C4 plants consist primarily of tropical grasses, millets, sugarcane, corn, and sorghum. C4 plants thrive in warm and high-temperature environments and thus are restricted to coastal zones in regions with temperate climates (Leegood, 2013; Price et al., 2017). For this reason, they are common in Amaranthaceae, Cyperaceae, Portulacaceae, Poaceae, and other families typical of Mediterranean environments (Pyankov et al., 2010). The analysis of faunal bones can help in determining whether these animals ate C3 or C4 plants, as there is an enrichment in δ13C between diet and consumers [5‰ for herbivores and 0‰−2‰ between trophic levels (Bocherens and Drucker, 2003)]. δ13C measurements are also helpful in differentiating between terrestrial C3 and aquatic food sources (Kellner and Schoeninger, 2007; Froehle et al., 2010).

δ15N values indicate the trophic position (herbivore, omnivore, and carnivore) of consumers in a food chain (Schoeninger, 1985; Hedges and Reynard, 2007; Price et al., 2017), with an enrichment between diet and consumer of around 3‰−5‰ (Schoeninger, 1985; Hedges and Reynard, 2007). δ15N values can also be used to distinguish between terrestrial and marine diets (Deniro and Epstein, 1981; Webb et al., 2017), and the consumption of manured, and unmanured crops (Deniro and Epstein, 1981; Bogaard et al., 2013; Fraser et al., 2013; Fernández-Crespo et al., 2019). δ34S of bone collagen from terrestrial species is often measured along with δ13C and δ15N to identify consumption of marine foods (Nehlich et al., 2010).

The global mean δ34S value of terrestrial sources is assumed to be 0‰ (Nehlich, 2015). Inorganic sulfur enters the food web through plants from the weathered bedrock (in a complete terrestrial setting), precipitation (sea spray), and microbial activity due to flooding events (Nitsch et al., 2019). As the inorganic sulfur passes through the food web in the form of proteins, only a negligible fractionation occurs between diet and consumer (Hobson, 1999; Nehlich, 2015). Thus, the δ34S ratio of collagen closely reflects that of the native water source, bedrock, and soluble sulfur-bearing minerals.

There are two significant inputs that humans can manipulate to cultivate plants: water and nitrogen input, which can be investigated using stable isotopes. Variation in δ13C values of plants is primarily due to water availability as any dry spells affect the movement of carbon dioxide through the stomata (Ferrio et al., 2005, 2007; Fiorentino et al., 2015). The water status of crops can be artificially controlled by irrigation regimes, reflected in δ13C values (Ferrio et al., 2005; Wallace et al., 2013). δ13C values measured in archaeological plants must be converted to carbon discrimination values to be compared with those of the modern crops grown under controlled watering regimes (Farquhar et al., 1989; Coplen, 2011; Wallace et al., 2013):

Another major factor, which affects the δ13C measurements of plants, is the canopy effect, where forested areas are more depleted in the heavier 13C isotope compared to open areas (Bonafini et al., 2013). Thus, the δ13C measurements of plants are the result of multiple factors and should be interpreted with caution. One of the most ancient practices to increase soil fertility is the application of animal manure which significantly enriches the nitrogen content compared to endogenous soil (Bogaard et al., 2013). Usually, the plants treated with manure exhibit higher δ15N values (as much as 10‰) when compared to unfertilized plants (Bogaard et al., 2007; Fraser et al., 2011). The δ13C and δ15N values themselves do not reveal the agricultural practices but reveal patterns when interpreted within a specific archaeological and ecological context.

Most knowledge about Phoenician and Punic agriculture comes from the famous treaty by Mago, of which only a few fragments have survived and subsequently translated (Martin, 1971). Other accounts are by authors from the Greek and Roman domains, usually written centuries after the pinnacle of the Phoenician-Punic horizon. The current understanding has been mainly developed due to systematic excavations of different Phoenician–Punic settlements in Iberia and subsequent zooarchaeological and archaeobotanical studies on the recovered faunal and plant remains (Wagner and Alvar, 1989; Aubet, 2001; Wagner and Alvar, 2003). The Southwest Iberian region has been praised by Strabo (3, 2, 8) for possessing the rare combination of abundant mineral deposits and natural fertility (Roller, 2014). From the 9th century BCE, the Phoenician presence is noted in the Iberian Peninsula along the Mediterranean and Atlantic coastal zones. This strategic location gave them reasonable access to the sailing routes and provided them with a plethora of cultivable land (Aubet, 2001). Colonies in Iberia were located in a landscape similar to the Levant with proximity to the coast and marked with steep mountain ranges and riverine valleys. Being located in a river valley gave the colonizers the ease of adapting existing practices from the Mediterranean in the Iberian hinterland. This included modifying and adapting the landscape to suit their agricultural needs, comprising farming and animal husbandry (Gómez Bellard, 2019).

Agricultural techniques from the East, such as irrigation, were probably used to improve upon the native practices, at least in some areas. The iron production technology gave more robust implements such as plowshare, to the farmers. Better yielding cultivars (e.g., grapes and olives) and new species of animals (e.g., horse, donkey, and chicken) were introduced (Van Leeuwaarden and Janssen, 1985; Queiroz et al., 2006; Davis, 2007). Following the “6th century crisis,” in the period referred to as the Punic period, an economic change brought a drastic transformation in space use concerning both settlement and domain. In the latter phase of the Iron Age, in addition to the cultivation of cash crops and wine, local usable arboreal products such as timber and fruits were identified and exploited to boost exports (Neville, 1998; Gómez Bellard, 2019). The exploitation of arboreal products and perennial crops meant the existence of both short-term and long-term agricultural investments. Such diverse investments with different harvest times must have led to the development of a complex agricultural economy.

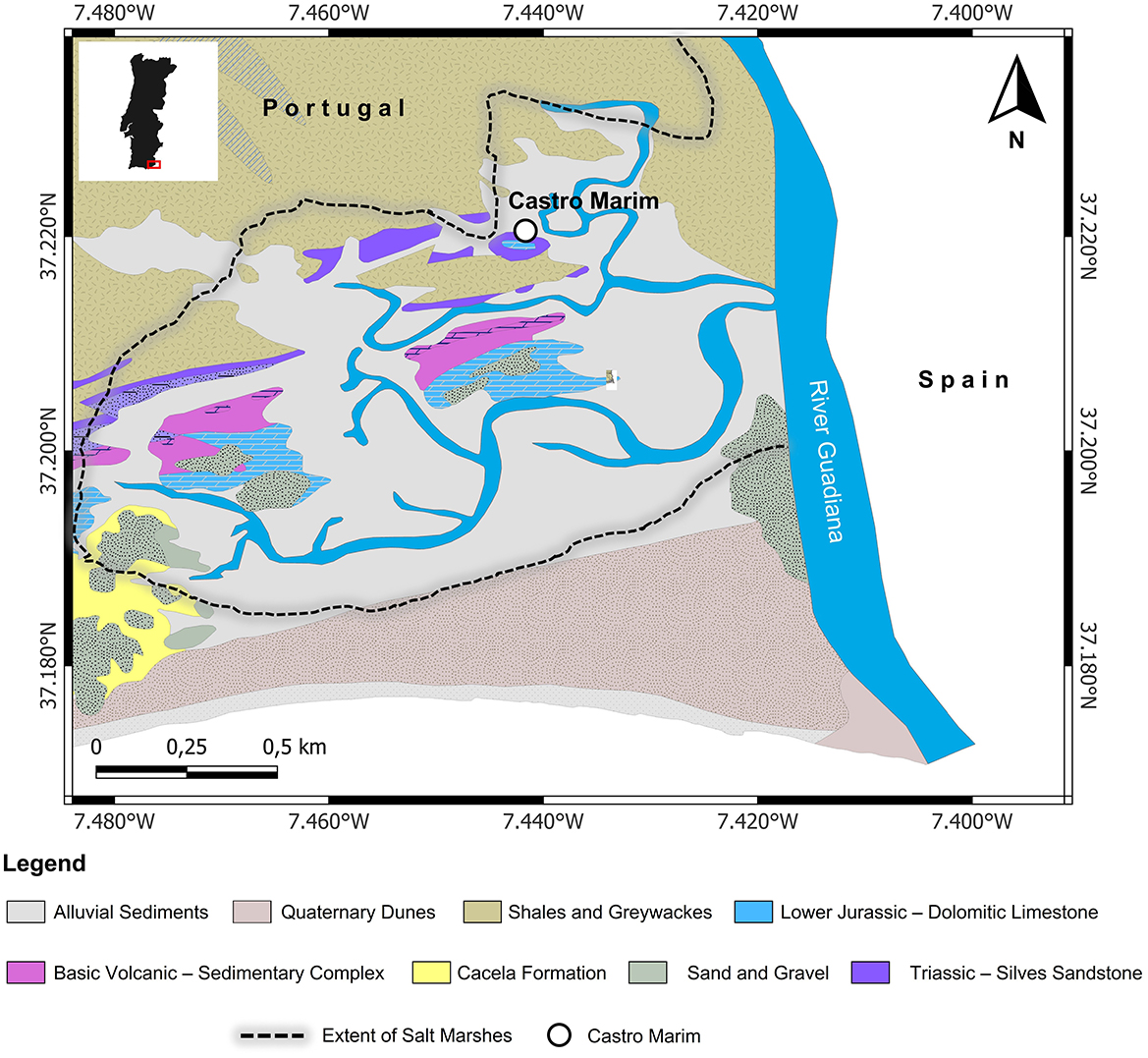

Castro Marim is located on the Guadiana estuary (Figure 1) as a portal to the metallogenic mineral-rich Baixo-Alentejo region as well as to the fertile cultivable lands in the interior regions. The Iron Age settlement was located on an elevation with adequate natural defensive elements and overlooked vast swatches of land, which allowed domination of estuarine traffic and agricultural activities in its domain of influence. These conditions allowed trade and cultural networks between the indigenous communities and the Mediterranean communities to flourish. The earliest Iron Age occupation of the site is characterized by East-West orthogonal settlement architecture dating from the first half of 7th century BCE, in the Orientalizing period (Arruda, 1996; Arruda et al., 2013). This earliest Iron Age occupation corresponds to Castro Marim's phase II (1st half of the 7th century BCE), III (2nd half of the 7th century BCE), and IV (6th century BCE). Phoenician imports and other evidence for human presence declined from the second half of the 6th century BCE till the first half of the 5th century BCE (Arruda, 1996). Significant changes in material culture and restructuring of the settlement architecture with a Northeast-Southwest orientation are observed from the second half of the 5th century BCE (Arruda et al., 2006, 2013; Arruda and de Freitas, 2008). The earlier period's departure was marked by imports from Greek products—specifically ceramics such as kilikes, skyphoi, and kantharoi (Arruda, 1997; Arruda et al., 2020). This resurgence put Castro Marim back in the main commercial circuits along the Iberian Peninsula's Atlantic coast till the 3rd century BCE (Arruda, 2000; Arruda et al., 2006, 2013; de Sousa, 2019). The Phoenician-Punic period is represented by archaeological phases III, IV, and V.

Figure 1. Geological map of the region around Castro Marim on the banks of Guadiana River, Algarve Region of Portugal in EPSG 4,326 projection (source: Directorate General of Mines and Geological Services - Carta de Geológica de Portugal).

Castro Marim's location in a littoral zone made it possible to adopt a wide range of agricultural strategies and husbandry practices. The presence of cereals (Hordeum and Triticum), grapes (Vitis vinifera), pulses (Vicia and Cicer), and other cultivated species (Olea and Coriandrum), as well as the exploitation of wild woody plants (Pinus and Arbutus etc.) have been elucidated from the archaeological record (Queiroz et al., 2006). Animals recovered from the excavation (native to Portugal) include cattle (Bos taurus), goat (Capra hircus), sheep (Ovis aries), pig (Sus scrofa/domesticus), red deer (Cervus elaphus), and rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) (Davis, 2007). The arrival of chicken (Gallus domesticus) has been documented, being introduced at least in the second half of 5th century BCE (Davis, 2007).

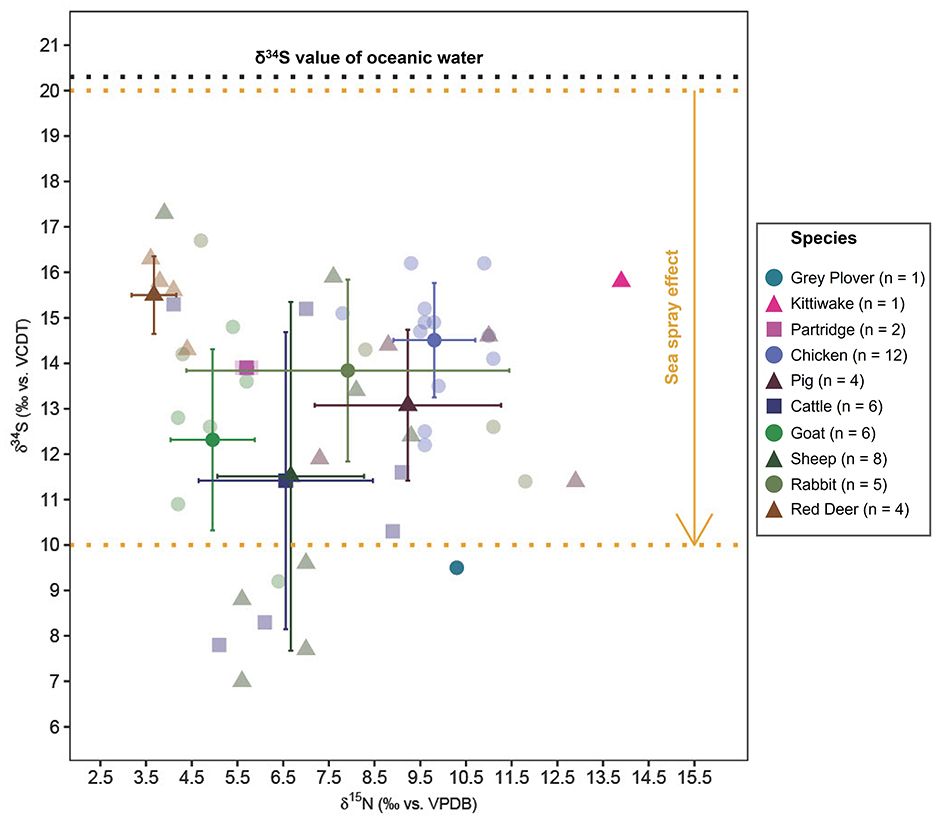

The geology of Algarve region is constituted of the distinct Paleozoic southern Portuguese zone, and the Mesozoic and Cenozoic Algarve basin. Castro Marim is located on the edge of the Paleozoic zone bordering the Quaternary dunes toward the coast (Figure 1). The area surrounding Castro Marim is a mosaic of the geological evolution involving marine transgressions, seismic and volcanic activities, and erosion (Fletcher, 2005). The Paleozoic zone which is part of the Hesperic Massif which is primarily made up of carboniferous turbites. The narrow upper Triassic and lower Jurassic outcrops parallel to the Paleozoic zone, known as “Grés de Silves” consist of a series of conglomerates, sandstones, and clay stones. The Quaternary dunes consist of black clays which go back to 8,000 years and the salt marsh developed during the last 5,000 years (Fletcher, 2005; Moura et al., 2017). According to the author's knowledge, there have been no published studies on sulfur isotopes of the geological formations around Castro Marim. Since Castro Marim is located at a distance < 30 kilometers from the coastline, it is affected by the sea-spray effect. Oceanic sulfate salts in the form of aerosols get deposited in coastal regions. These aerosols have been reported to have δ34S isotope values around +20.3‰ which is very distinctive from terrestrial sulfate salts (McArdle et al., 1998; Norman et al., 2006). It is reported that the oceanic sulfate salts can increase the δ34S isotope values of terrestrial soils closest to the coast values up to +18‰ with a gradual decrease up to +10‰ (Wakshal and Nielsen, 1982; Mizota and Sasaki, 1996; Nehlich, 2015). For distances over 30 kilometers from the coast, no higher δ34S isotope values were observed (Coulson et al., 2005). This range of δ34S isotope values can be utilized to determine if an animal is of coastal/non-coastal origin. As Castro Marim is located near the coast, we can extend the interpretation of coastal as local to a certain extent cautiously.

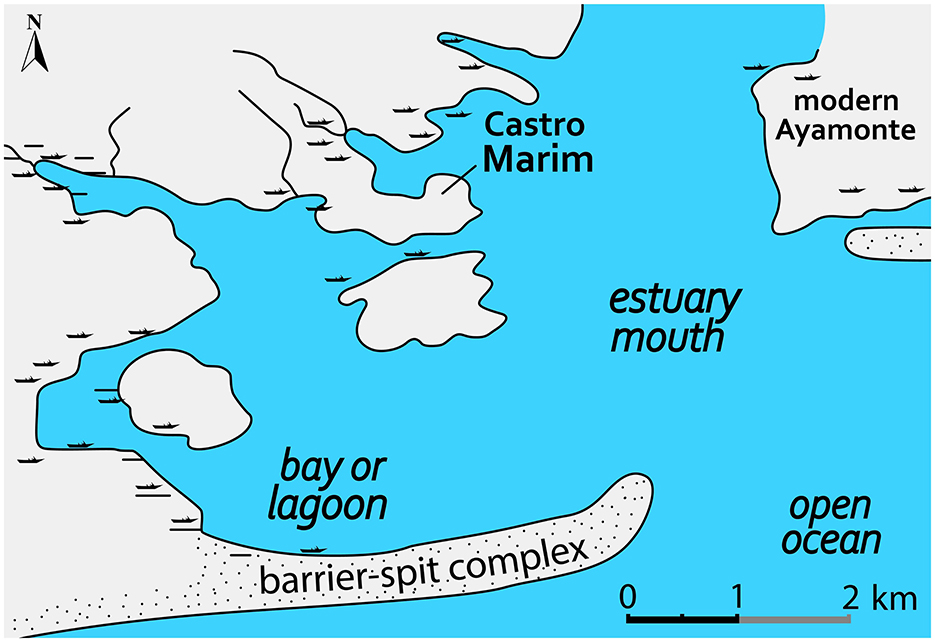

Landscape surrounding during the Iron Age was quite different from what it is in modern times. Paleogeographic reconstruction based on geophysical and lithological data of the Guadiana estuary indicates muddy-bottom shallow estuarine setting at the mouth of the river during the Phoenician period, with the Iron Age settlement situated on a ridge projecting northward (Figure 2) with a Pleistocene/mid-Holocene bedrock platform (Wachsmann et al., 2009). After the arrival of Phoenicians (874 BCE), there was a decline in pinewood, Quercus forest, and sclerophyllous thickets with an increase in scrub vegetation consisting of fire-adapted Cistaceae and Ericaceae (Fletcher et al., 2007). This is due to prevailing warm and dry climatic conditions corresponding to a more arid regime across southern Iberia (Jalut et al., 2000; Magny et al., 2002).

Figure 2. Reconstruction of the Guadiana estuary during the Phoenician period based on geophysical and lithological data (adapted from Wachsmann et al., 2009).

The original archaeobotanical assessment was carried out by Queiroz et al. (2006). The assessment reported charcoal, fruits, and seeds recovered from all the archaeological phases of the site. As the current study focuses on the period between 7th-5th century BCE, the findings from the relevant stratigraphic units from phases III-V are summarized below. The sediments from phase III did not yield any macro-botanical remains. In phase IV, pine cones (Pinus pinea) accounted for 44.34% of the 41 individual seeds and fruits recovered. Barley accounted for 31.7%, Vicia faba, present in Portugal since prehistoric times for 17%, and finally acorns Quercus sp. for 5%. Cereals make up 95.3% of the total recovered carpological remains (n = 3,109) in phase V. The bulk of cereals is barley (Hordeum vulgare) with a tiny fraction of wheat (Triticum durum/aestivum). Of the remaining 3.7%, broad beans (Vicia faba) were the bulk of the pulses while the chickpeas (Cicer arietinum), introduced from Asia, were considered a luxury food in the Roman period were sparsely present (0.6%). The presence of grape (Vitis vinifera) pips and charred wood is typical, starting from the Phoenician period in Portugal. The presence of grape pips in Iron Age Castro Marim indicates exploitation of wild vines or cultivated non-local vines by the local population. The most exciting carpological remains are of coriander (Coriandrum sativum), which is not native to Portugal and was supposed to be introduced during medieval times, making this the earliest coriander occurrence in Portugal. Charred pine, oak, ash, and poplar wood were recovered abundantly. The exploitation of wild woody plants for timber and fruits marks the Phoenician colonization of the Iberian Peninsula. Due to unforeseen circumstances, these identified remains could not be accessed for isotope analyses. Previously unprocessed sediments were studied again to gain plant remains.

Based on normalized counts of skeletal remains (NISP) from phases III-V, ovicaprids (sheep and goats) make up 23.3% of the Castro Marim assemblage, followed by cattle at 6.7% and pigs at 6.1%, dominating the mammalian taxa (Davis, 2007). Both sheep and goats were equally represented with negligible fluctuations throughout the Iron Age at Castro Marim. In wild species, red deer made up 2.7% of the identified bones and while the rabbits accounted for 3.4%. Both species (red deer and rabbits) are present consistently in all the phases of the settlement. It is worth mentioning here that no morphometric distinction could be made between wild and domesticated pigs. There is a spike in the presence of bird remains in the later phases of the Iron Age (Phase IV-V), primarily due to the introduction of domesticated chicken. The presence of partridge (Alectoris rufa), a common wild species of Iberia, is also noted. Unlike the chicken, partridge has never been domesticated. Ovicaprids and cattle were kept well into maturity indicating that they were prized more for their secondary purposes than their meat. Sheep and goats were kept for their milk and wool, usually slaughtered after they reached at least 2 years of age. Cattle were valued for their power to plow in the fields as well as to pull heavy loads. Also, they too, were a source of milk. Pigs, on the other hand, were slaughtered as juveniles as they were primarily reared for meat. Most of the red deer found were adults, suggesting a hunting preference of that period as a vital subsidiary source of meat. Chicken seems to be slaughtered at a young age, indicating their domesticated status, while partridges were slaughtered at an adult age, suggesting they were wild.

Two hundred grams of sediment from each stratigraphic layer of phases III and IV along with the layers corresponding to the 5th century BCE from phase V of the excavation site was weighed and handpicked for plant macro remains (seeds/fruits and charcoal). The recovered remains were examined under a stereomicroscope and taxonomically identified (Table 1).

Nine charred plant macroremains (Table 2) of Hordeum vulgare subsp. vulgare, Hordeum vulgare subsp. nudum, and Pinus pinea each. Three grains of each barley cultivar and 3 shell fragments of pine shells were crushed in to a homogeneous powder to make a representative sample with sufficient mass for measuring stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes. Fifty faunal bone samples (Table 3) from conclusively adult individuals have been selected for this study. The sampled faunal bones represent the Phoenician-Punic period of the settlement (phases III, IV, and V), whereas the charred plant macro-remains are only from phase V due to the absence of plant remains from the older phases.

In carbonized plant macro-remains, barley caryopses samples consist of at least 10 whole grains, and pine samples consist of shell fragments. Morphologically intact samples were chosen after examination under a stereomicroscope (7–45x magnification) and removing any visibly adhering foreign contaminant. An acid-base-acid (ABA) treatment was applied as a pre-treatment (Bogaard et al., 2013; Fraser et al., 2013). First, the samples were treated with 10 mL of 0.5 M HCl at 70°C for 60 min (or until effervescing stops) and then rinsed with ultrapure water until a neutral pH was achieved. Ten mL of 0.1 NaOH solution was added to the samples at 70°C for 60 min and then rinsed with ultrapure water to achieve a neutral pH. Finally, the samples were treated with 0.5 M HCl at 70°C for 30–60 min, followed by three rinses with ultrapure water and subsequent freeze-drying.

500–700 mg of bone was cut using a DREMEL® rotary drill with a diamond disc and cleaned of dirt, discoloration, and other foreign content with a dental burr. Compact bone was sampled over spongy bone. The modified Longin (1971) method was used to extract collagen from faunal bones pieces previously analyzed with FTIR by demineralization (Richards and Hedges, 1999). Approximately 600 mg of bone sample was demineralized using 0.5 M HCl at 4°C for a fortnight with daily vortex and an acid change after 7 days. Repeated rinses with ultrapure water to reach neutral pH were performed, and the demineralized bones were subjected to an overnight treatment in 0.125 M NaOH at room temperature to remove fulvic and humic acid contamination. The samples were then rinsed repeatedly with ultrapure water to achieve neutrality and gelatinized in 0.01 M HCl at 70°C for 48 h. The impurities were separated by filtering the collagen-containing liquid fraction using Ezee–Filter™ filters (Elkay® Laboratory Products). The solubilized collagen was frozen and subsequently lyophilized for 48 h.

A small subsample of the extracted collagen was placed into a microfuge tube and 100 μL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (AmBic) was added to the samples. The samples were digested overnight using 1 μL of 0.5 μg/μL porcine trypsin (Promega®, UK) at 37°C and the digestion was stopped by the addition of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at a concentration of 0.5–1% of the total solution. The samples were desalted using C18 zip-tips (van Doorn et al., 2011) and eluted using 100 μL of 50% acetonitrile (ACN)/0.1% TFA (v/v). The zip-tipped samples were spotted in triplicate onto a MTP384 Bruker ground steel MALDI target plate; 1 μL of sample was pipetted onto each sample spot and then mixed with 1 μL of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix solution [1% in 50% acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (v/v/v)].

The samples were analyzed on a Bruker® Ultraflex III™ MALDI-ToF mass spectrometer. The resulting MS spectra were analyzed using mMass (Strohalm et al., 2010) an Open Source mass spectrometry interpretation tool. The three spectra for each sample were averaged and the averaged spectrum was cropped between 800 and 3,000 m/z and peak picking was carried out using a signal to noise ratio of 6. The resulting spectra were compared to a publicly available ZooMS database.

An amount of 0.5–0.7 mg of freeze-dried collagen powder/barley grain samples were weighed in tin capsules and combusted in an elemental analyzer (EA) with oxygen (Flash 2000 HT™, Thermo Fisher Scientific®, Bremen, Germany) using pure helium as carrier gas. Isotopic ratios were obtained on a Delta V Advantage Continuous Flow™–Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific®, Bremen, Germany). The raw machine output was normalized by a three-point calibration using international standard reference materials (SRM), namely IAEA-CH-6 (sucrose, δ13C = −10.499‰), IAEA-600 (caffeine, δ13C = −27.771‰; δ15N = +1‰), and IAEA-N-2 (Ammonium Sulfate, δ15N = +20.3‰) and in-house standard L-Alanine (δ13C = −18.4‰; δ15N = +0.9‰). The standards were regularly (after 11 analyses) included in the analytical routine to correct for instrumental drifts. The isotope values are expressed in per mil (‰) relative to VPDB (Vienna Pee-Dee Belemnite) for carbon and AIR (Ambient Inhalable Reservoir) for nitrogen. Precision [u(RW)] for δ13C and δ15N was determined to be ±0.116 and ±0.092 respectively in the basis of repeated measurement of calibration standards and check standards. Accuracy [u(bias)] of δ13C is ±0.175 and that of δ15N is ±0.228. The total analytical uncertainty was determined to be ±0.43 for δ13C and ±0.33 for δ15N. In order to correct for charring effect in plant remains, 0.11‰ and 0.31‰ were subtracted from their δ13C and δ15N values, respectively (Nitsch et al., 2015). The fluctuations in δ13C of the atmospheric CO2 throughout the Holocene were considered while interpreting the stable carbon isotope ratios. The δ13C of atmospheric CO2 during the period in the study was approximated using the AIRCO2_LOESS system, and then this value was used to compute the δ13C discrimination of plants independent of the source CO2 (Farquhar et al., 1982; Ferrio et al., 2005).

The collagen samples were combusted with additional V2O5 and an oxygen pulse (IsoPrime™ Mass spectrometer, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH®, Langenselbold, Germany). Calibration of δ34S values was performed using international inorganic standards for stable sulfur isotope analysis: NBS127 (+20.3‰) and IAEA S1 (−0.3‰). B2155 protein (+6.32 ± 0.8‰) was used as an internal quality control standard. Precision [u(RW)] and accuracy [u(bias)] for δ34S are 0.098 and 0.963 respectively. The calculated uncertainty (uc) for δ34S is 0.967. Stable sulfur isotope values are reported in parts per thousand relative to Vienna-Canyon Diablo Troilite (VCDT). The analysis was performed at SIIAF at the University of Lisbon.

The obtained data were subjected to statistical analysis using R programming language (Wickham, 2016; R Core Team, 2020). Initially, means and standard deviations were calculated per species. Z-scores were calculated to detect the presence of outliers. Deviance from normal distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilks test. F-tests were first used to check for significant equal variance, and subsequently, unpaired Student's t-tests were used for two-sample comparison since all the datasets were normally distributed.

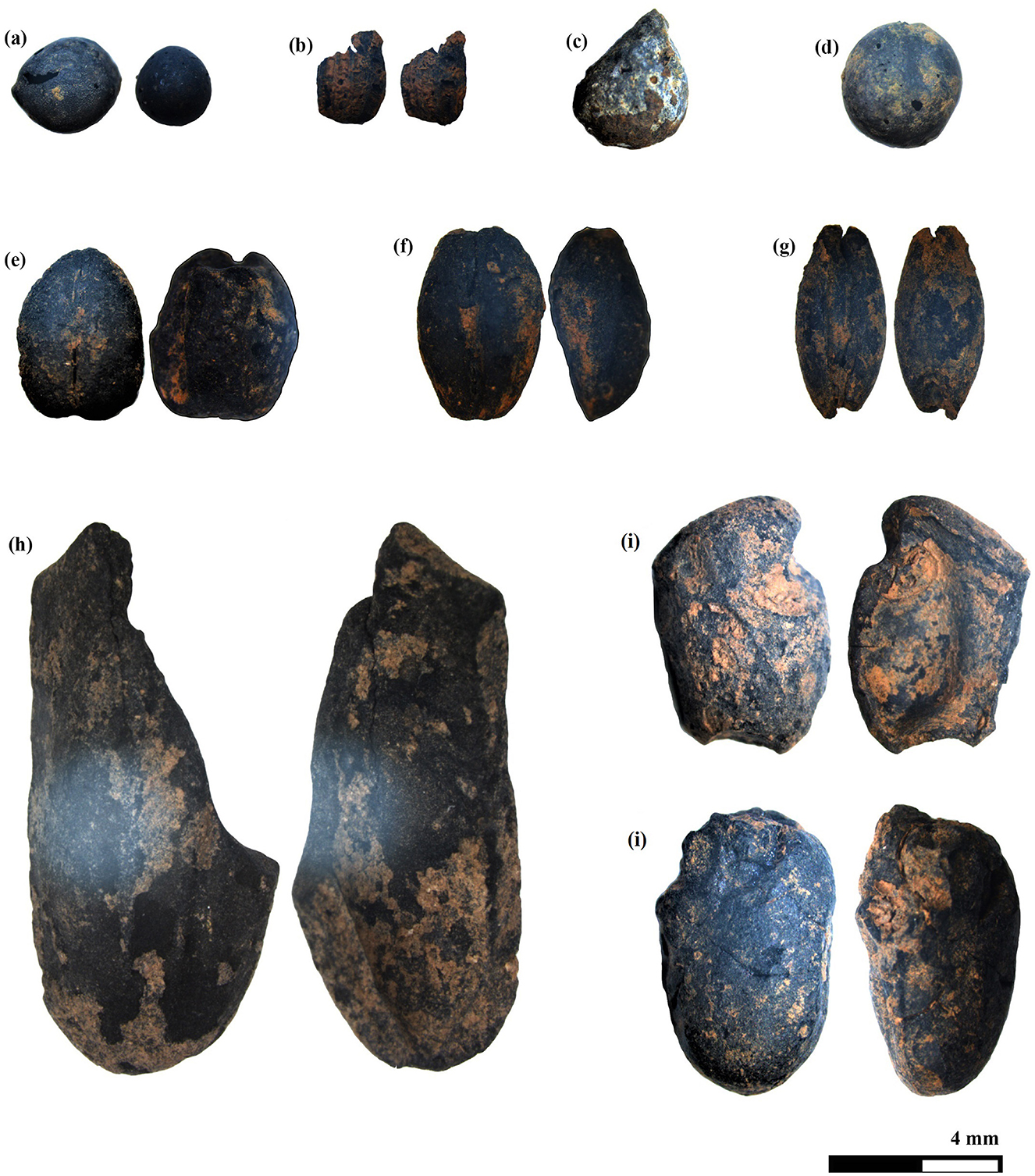

As the excavation was conducted a decade prior to this study, only 200 grams of sediment per stratigraphic unit were available for analysis from the archaeological depot. No botanical remains could be recovered from the soil samples of phases III and IV. The bulk of the recovered remains are from phase V representing the most mature chronological period of the occupation. Barley (Hordeum vulgare) is the dominant taxon in the botanical record (Table 1). Hordeum vulgare var. nudum and Hordeum vulgare subsp. vulgare (Figures 3F, G, respectively) are the two cultivars that constitute the barley fraction with equal abundance. Wheat (Triticum aestivum/durum, Figure 3E) is the second most abundant taxon after barley. Large-scale cereal cultivation has been observed in sites located in river valleys near the South Iberian sea coast, including, Castillo de Doña Blanca in Guadalquivir Valley and El Villar in Guadalhorce Valley (Semmler, 1990, 1992), two sites which are located in similar geographical settings to Castro Marim. Cereal cultivation seems to be a significant activity, implying that cereals were the principal source of carbohydrates for both humans and animals. The greater presence of barley compared to wheat can be a strategy of “minimum returns on investment” against dry climatic conditions exploiting the fact that barley has a higher tolerance to drier conditions than wheat (Riehl, 2009). Two taxa of pulses have been noted, namely, pea (Pisum sativum) and broad bean (Vicia faba) (Figures 3D, I respectively). Pulses serve as a rich source of proteins and act as an alternative to animal-sourced protein for humans. The combined cultivation of pulses with cereals helps to maintain adequate soil nitrogen levels, leading to sustainable and diverse production. The presence of black mustard (Brassica nigra) (Figure 3A) has been recorded. Black mustard is a common species along the rocky Mediterranean coasts and has long found its place as a culinary taste enhancer (Dixon, 2006). Like many members of Brassica, black mustard was also used as a source of oil (Peña-Chocarro et al., 2019). Galeopsis tetrahit (Figure 3C), a commonly found weed in Europe has also been recovered.

Figure 3. Charred plant remains of settlement phase V from Castro Marim; (A) Brassica nigra; (B) Apium cf. graveolens; (C) Galeopsis tetrahit; (D) Pisum sativum; (E) Triticum aestivum/durum; (F) Hordeum vulgare var. nudum; (G) Hordeum vulgare subsp. vulgare; (H) Pinus pinea; and (I) Vicia faba.

A fragment of a charred fruit has been attributed to Apium taxon, suspected to be a seed of celery (Apium graveolens) (Figure 3B). This attribution is done due to the presence of five slender longitudinal ridges on the surface of the fruit (Wilson, 2016). This species is native to the coastal Mediterranean region, considered to be its center of origin. The recorded use of celery as a vegetable in Europe is only from the 1,600s, originating in Italy, and gradually spreading westwards in the subsequent centuries (Tobyn et al., 2011). The consumption of celery as a vegetable started in the Mediterranean region only around the 16th century CE. In the Phoenician–Punic period, it could have been either cultivated or foraged as a medicinal herb rather than a food plant (Sturtevant, 1886). Shells of pine nuts (Figure 3H) belong to the species Pinus pinea, commonly known as Mediterranean stone pine. Pine nut consumption has been documented in Portugal since the Paleolithic period (Gale and Carruthers, 2000). The stone pine nuts are high in protein and fat with low carbohydrates (Haws, 2004). The nuts are a valuable source of nutrition and could have been stored during low cultivated food production periods.

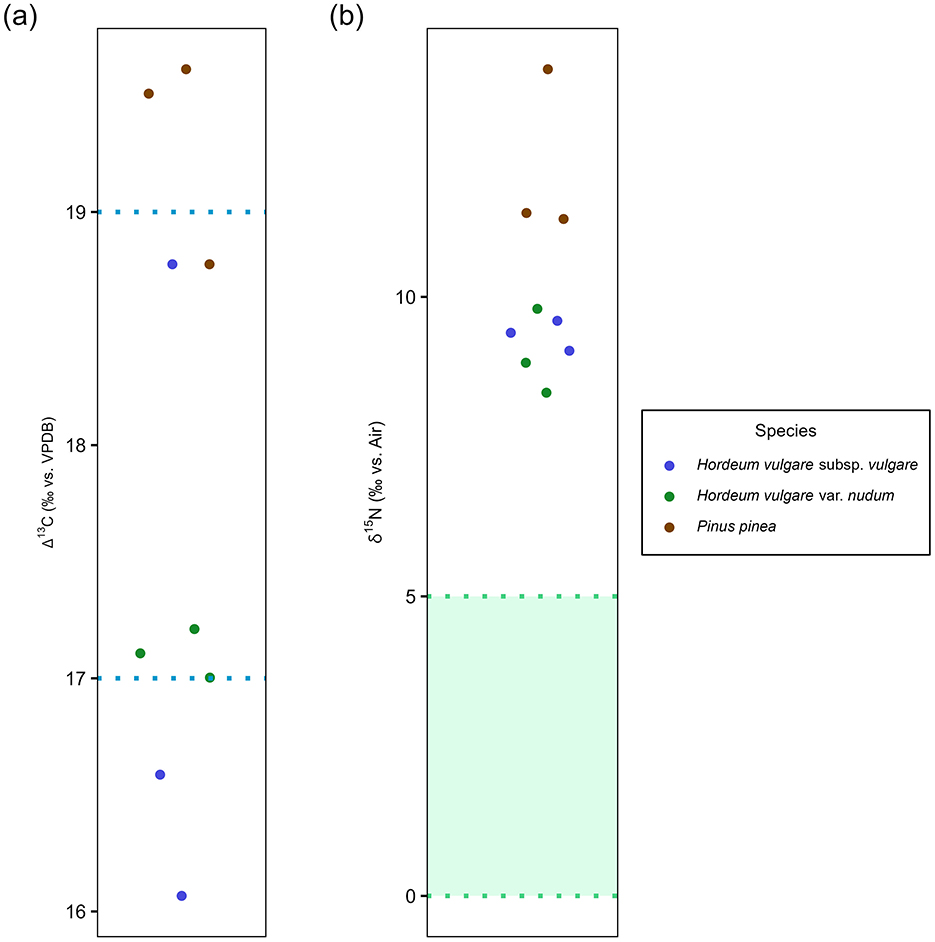

Table 2 shows the results of stable isotope ratios of the two barley cultivars and stone pine and Table 4 shows their mean summary. In the case of barley, the isotope ratios fall within the established predicted ranges obtained from experimentally charred modern cereals (Fraser et al., 2013). Since the isotope ratios of the stone pine are similar to that of barley, they are considered consistent.

Collagen yields range between 2.5% to 49.1% (Table 3). Collagen extraction was considered successful for all the bone samples, based on published criteria, with carbon content between 15.3% and 47.0% (Ambrose, 1990), nitrogen content between 5.5% and 17.3% (Ambrose, 1990), C/N values between 3.15 and 3.50 (conservative upper limit with 0.5% tolerance) (Guiry and Szpak, 2021), C/S values between 300 and 900 (Nehlich and Richards, 2009), N/S values between 100 and 300 (Nehlich and Richards, 2009), and collagen yields >1% (van Klinken, 1999). The extracted bone collagen samples exhibit C/N values ranging between 3.1 and 3.5, C/S values between 225.9 and 688.4, and N/S vales between 103.4 and 256.4. Carbon and nitrogen amounts range from 20.3% to 50.0% and 7.3% and 18.1% respectively. All the faunal samples, with the exception of one sample (CMOF673) exhibited collagen quality parameters indicative of good preservation. CMOF673 which is a goat had N/S value of 287.6 which is slightly outside the acceptable range proposed in Nehlich and Richards (2009). However, the stable isotope values of the sample are coherent with the other goats and thus considered for interpretation. The taxonomic identification of sheep and goat samples was successfully performed based on ZooMS. The identified sample entries are in bold format (Table 3).

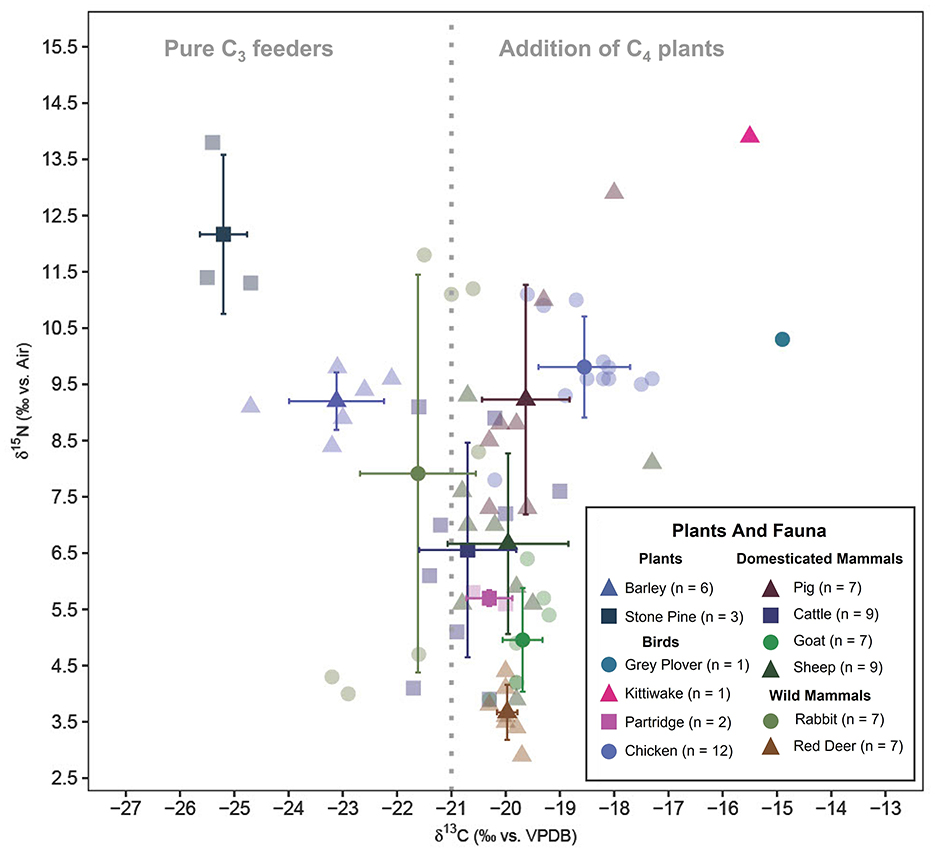

All fifty faunal samples, demonstrate stable isotope values within the range expected for a C3 temperate ecosystem with δ15N and δ34S values of fauna ranging from 2.9‰ to 17.3‰ and 9.5‰ to 15.8‰ respectively. The isotope composition of the fauna is presented in Table 3 and the mean summary data by species in Table 4.

The δ13C means of both barley cultivars show no statistically significant difference (t-statistic: −0.04, degrees of freedom: 4, p-value: 0.97). The Δ13C values (Figure 4A) show barley cultivated in poor to moderate watering conditions, which would indicate that the plants have been dependent on natural precipitation with little or no artificial irrigation in an arid climatic regime (Fletcher et al., 2007; Fernández-Crespo et al., 2019). The authors acknowledge the fact that the “watering bands” construct established by Wallace et al. (2013) has its limitations. However, in this study the Δ13C isotope values of the plant remains are in agreement with the regional climatic regime data of Algarve (Fletcher et al., 2007). This, combined with the lack of any other contemporary ethnobotanical isotope data from the region, justifies the use of watering bands. There is no significant difference in δ15N (t-statistic: 0.77, degrees of freedom: 4, p-value: 0.49) between the two barley cultivars, but Pinus pinea yields higher δ15N values (Table 2). The δ15N mean values of C3 plants near salt marshes are higher when compared to coastal and inland sites (Cloern et al., 2002). The stone pine samples exhibit higher mean values than the barley cultivars despite the possibility that the latter could be subjected to manuring regimes (Figure 4B). Both cultivars of barley yield enriched δ15N values compared to estimated wild herb forage values (green shaded area in Figure 4B). The Δ13C and δ15N values indicate that the barley was very likely cultivated in agricultural fields farther away from the coastline which would explain their poor to moderate watering conditions despite Castro Marim being close to the Guadiana estuary. Because the settlement was located on a narrow strip of land surrounded by water (Figure 2), the lack of space to grow crops could have been the primary reason for growing the barley away from the coast. The higher δ15N values of stone pine when compared to barley does not imply that the former originates from the salt marshes. This is reflected by the elevated Δ13C values of stone pine which are similar to one sample of barley. The elevated Δ13C and δ15N values observed in stone pine are inconsistent with natural coastal conditions, as C3 plants typically exhibit lower Δ13C values under saline stress (Smith and Epstein, 1970), and the absence of coastal salinity rules out salt-induced stress as the cause of increased δ15N values (Heaton, 1987). Instead, anthropogenic activities of irrigation and manuring can explain both elevated Δ13C and δ15N values of the stone pine relative to the two barley cultivars. This interpretation is supported by earlier pollen-based studies which hypothesized proto-silvicultural management of naturally occurring or planted stone pine formations in parts of Portugal including Castro Marim since the Neolithic (Mateus and Queiroz, 1991, 2000; Mateus, 1992; Queiroz, 1999). Further evidence of stone pine's significance is found in the form of limestone pine cone idols from the Chalcolithic dolmen of Casaínhos (Queiroz et al., 2006; Sousa and Gonçalves, 2022). Previously published pollen and current isotopic data point toward deliberate human management of stone pine at Phoenician Castro Marim.

Figure 4. (A) Beeswarm plot showing Δ13C values of barley cultivars where the area between the blue dashed lines represents “moderately-watered” condition with the “well-watered” condition being above the top blue line and “poorly-watered” condition being below the lower blue line, based on the study of modern crops in varying watering conditions (Wallace et al., 2013). Δ13C values of stone pine have been plotted as well for the sake of visualization. (B) Beeswarm plot showing the manuring status of barley cultivars with green shaded region representing 1 SD range of estimated wild herbivore forage value (calculated from subtraction 4‰ from red deer δ15N mean ± 1 SD range).

Red deer when compared to other fauna have similar δ13C isotope values and lower δ15N values. Red deer mainly inhabit forested areas and surrounding open fields with a diet of grass, sedges, fruits, and seeds (Gebert and Verheyden-Tixier, 2001). The δ13C values and δ15N values of red deer indicate foraging on wild vegetation in open fields near the edges of forests of the coast. Red deer also exhibit some of the highest δ34S values which fall well within the expected range for areas affected by sea-spray. The red deer most likely were of local origin hunted as game for their meat. The mean δ13C values of rabbits are significantly lower than those of red deer (t-statistic: −4.01, degrees of freedom: 12, p-value: 0). This can be attributed to the rabbits' foraging ground level flora with high recycling of CO2 and shade from the higher levels of the canopy in contrast with the red deer foraging at taller vegetation. Feeding in forested areas causes the δ13C values to deplete due to the canopy effect (Bonafini et al., 2013). The δ15N values of rabbits are anomalous with a standard deviation spanning almost a trophic level (standard deviation of δ15N: 3.5‰). It can be observed from Figure 5 that the rabbits consist of two distinct groups, one group with higher δ13C and δ15N values compared to the other (Figure 5). The group of rabbits with higher δ15N values correspondingly have lower δ34S values (Figure 6) which confirms salt marsh foraging (Guiry et al., 2021) whereas the other group had more coastal foraging.

Figure 5. Plot showing mean δ13C and δ15N values (mean ± 1 SD range) of faunal bone collagen and botanical remains. The color palette is produced with the Colorgorical web app (Gramazio et al., 2017).

Figure 6. Plot showing mean δ15N and δ34S values (mean ± 1 SD range) of faunal bone collagen. The yellow lines mark the range while the arrow indicates the decreasing trend of δ34S values as one moves inland away from the coast up to 30 km (Wakshal and Nielsen, 1982; Mizota and Sasaki, 1996; Nehlich, 2015).

Goat mean δ13C values are not significantly different from those of sheep (t-statistic: 0.61, degrees of freedom: 14, p-value: 0.55). Though, the δ13C values of sheep and goats are not significantly different, the species have very different foraging preferences (Balasse and Ambrose, 2005). Sheep are predominantly grazers and their dietary composition remains relatively unchanged throughout the year (Dawson and Ellis, 1996; Balasse and Ambrose, 2005). δ13C values of ovicaprids indicate that the vegetation was C3 in its nature. The sheep could have been grazing in open spaces such as agricultural fields or the fodder could be harvested grass or hay. Goats on the other hand have been reported prefer browsing over grazing, usually on the leaves of deep-rooted herbs, bushes, and trees (Papachristou, 1997). The δ13C values of goats from Castro Marim also suggests a scenario of goats foraging in open forests. Sheep exhibit significantly higher δ15N values than goats (t-statistic: 2.5, degrees of freedom: 14, p-value: 0.03). The δ15N values further support a scenario where sheep were foddered on manured vegetation with the assumption of uniform coastal impact on all vegetation (Figure 5). Sheep are superior to goats both in terms of secondary products and ease of management (Rutter, 2002; Davis, 2007). Owing to the more attached economic interests with sheep, it is natural to give food sourced from cultivated crops. This could either be in the form of the sheep grazing in manured agricultural fields or were penned in the settlement space with the fodder sourced from cultivated crops. Goats were most likely raised for meat and given their preference for browsing, were left to forage on wild vegetation. Although, proximity to the salt marsh masks the increase of δ15N (as seen in Figure 4) values caused by manuring in cultivated crops, the statistically significant difference of δ15N between goats and sheep is likely due to the consumption of manured crops. The δ34S values of the ovicaprids fall well within the expected range of herbivores foraging on vegetation affected by sea spray with no statistically significant difference between each other (t-statistic: −0.47, degrees of freedom: 12, p-value: 0.65). As, δ15N and δ34S values have been shown to have negative correlation in salt marsh foraging animals, it is safe to conclude that the elevated δ15N values of the sheep are due to manured vegetation and not saline stress (Guiry et al., 2021). The δ34S values suggest that the ovicaprids are most likely of coastal and local origin. This does not negate the possibility that the individuals could have arrived at Castro Marim from another coastal place which is equally possible due to the sea-faring nature of the Phoenicians. The cattle have no significantly different (t-statistic: −1.57, degrees of freedom: 16, p-value: 0.14) δ13C isotope ratios when compared to sheep. Cattle also seem to have grazed in open areas similar to the sheep. The δ15N isotope ratios of cattle are also significantly not different from sheep (t-statistic: 0.13, degrees of freedom: 16, p-value: 0.9). The δ34S values of cattle are also very similar to that of the sheep (t-statistic: 0.05, degrees of freedom: 12, p-value: 0.96). Most of the cattle bones are from adults, which indicates that they were used as a source of power and only slaughtered for meat toward the end of their lives (Davis, 2007). Since they were used for labor intense tasks, their diet could have a considerable amount of cultivated crop components. All the three isotopic values of sheep and cattle present the image that the two domesticates were treated in a very similar manner and highly valued. Four sheep, two cattle, and one goat (Figure 6) are the only specimens showing δ34S values lower than +10‰, falling outside the range of sea spray effect, which might be indicative of their non-coastal and non-local origin. The slightly less negative δ13C and high δ15N values of pigs reflect an omnivorous diet consisting of agricultural components and human food scraps similar to the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods from Portugal (Waterman et al., 2016; Žalaite et al., 2018). The slightly less negative δ13C values and δ34S of the pigs (Table 4), compared to cattle and sheep are likely due to presence of fish and shellfish (mollusks and crustaceans) in the human food scraps.

The δ13C (t-statistic: 2.8, degrees of freedom: 12, p-value: 0.02) and δ15N values (t-statistic: 6.26, degrees of freedom: 12, p-value: 0.4−6) of chicken and partridge are significantly different, while their δ34S values are not (t-statistic: 0.66, degrees of freedom: 12, p-value: 0.52). Higher δ13C and δ15N values of the chicken can be attributed to its domesticated status, and indicate a diet of human food scraps with probably a marine component. Also, chicken eat insects alongside the human-provided food which can lead to an increase of δ15N values (Żabiński, 1959; Reitsema et al., 2013). Usual partridge diet consists of arthropods, grass seeds, flowers, and weeds while they prefer foraging at the edges of agricultural fields (Green, 1984) which can explain the higher δ15N values in comparison with red deer. All the partridges recovered are adults, whereas the chickens constitute juvenile-adult mix, further indicative that the former were hunted for consumption.

Gray plover has a mean δ13C value of −14.9‰ and a mean δ15N value of 10.3‰. Gray plovers are known to feed on insects (such as Coleoptera), polychaetes, mollusks, and crustaceans from lakes and muddy intertidal zones (Perez-Hurtado et al., 1997). The δ34S value of gray plover is outside the range expected for a full marine diet (Nehlich, 2015). Being long-distance migratory birds, gray plovers cross Western Europe on their way to Western Africa from Siberia and northwestern Russia often stopping near large lakes for nesting and feeding (Snow et al., 1998). The isotope values of gray plover are consistent with a diet including both terrestrial and marine prey. Kittiwake's diet consists of fish, marine invertebrates, and plankton (Bull et al., 2004). Kittiwake has a mean δ13C value of −15.5‰, mean δ15N value of 13.9‰, and a mean δ34S value of 15.8‰, as expected of a species with a complete marine diet.

Overall, the domesticated mammals are not above one trophic level (4‰ δ15N) over the plants (both cultivated barley and stone pine) (Figure 5). Inland Iron Age domesticated mammals have mean δ13C values ranging between 21‰−23‰ (for C3 temperate ecosystem) and δ15N mean values ranging between 3‰−5‰ for herbivores and >6‰ for omnivores (Styring et al., 2017; Fernández-Crespo et al., 2019; Hamilton et al., 2019; Schulting et al., 2019). In comparison, the fauna at Castro Marim have similar δ13C values and slightly higher δ15N mean values. Apart from manuring, another reason for these slightly higher δ15N values could be due to the proximity of the site to the salt marsh. Most of the Castro Marim δ34S isotope values are well within the range of sea spray effect (Figure 6). The large spread of the δ34S values could be due to the foraging spaces being located away from the settlement (< 30 kms) since Iron Age Castro Marim settlement was short of foraging space (Figure 2). The few individuals below the range can be considered as non-local.

It is complicated to reconstruct farming and animal husbandry practices using stable isotope approach in an estuarine setting with coastal, salt marsh, and slightly inland ecosystems due to the existence of multiple isotope baselines.

The Δ13C values of the two barley cultivars indicate a certain level of dependence on natural precipitation with little to no artificial irrigation. Based on the Δ13C values, stone pine seems to have better watering status than the barley cultivars. The manuring of barley was masked by the high nitrogen nutrient soils of the salt marshes. The elevated Δ13C and δ15N values of stone pine relative to those of the barley are likely due to anthropic watering and manuring of the taxon in the Iron Age. The significant difference between the mean δ15N values of sheep and goats can be due to manuring of cultivated crops. In the case of wild fauna, the δ13C and δ34S values of rabbits indicate foraging at ground level in closed settings, while those of red deer indicate grazing in coastal open forests. The δ15N and δ34S values of rabbits indicate two different groups, with one group foraging in salt marshes and the other in a more coastal setting. Ovicaprid δ13C and δ34S values indicate foraging in open pastures in proximity to the estuary. Comparing the δ15N ratios of sheep and goats shows that the former was fed by agricultural produce/by-products, which the latter lacked. The cattle also foraged in open coastal areas and had cultivated components in its diet similar to the sheep. Pigs exhibit δ13C and δ15N values consistent with an omnivorous diet. In the case of the seabirds, both gray plover and kittiwake exhibit δ13C, δ15N, and δ34S values consistent with their diet. Chicken δ13C and δ15N values are reflective of its domesticated status with a mixture of C3 plants, insects, and human food scraps (inclusive of fish, molluscs, and crustaceans). The δ15N values of the fauna are not a trophic level above the presented plant isotope values, which can be because of different isotope baselines or these plants were not a part of the former's diet. The δ34S values of most fauna indicate foraging near an estuary (salt marsh and coastline), indicative of a local origin. Goats, pigs, and chickens have a low range of δ34S values due to penning in specific spaces. The δ34S values of cattle and sheep have a more extensive range of values which could be due to wider foraging range or some individuals being of non-local origin.

This study is the first of its kind on Phoenician-Punic fauna from the Iberian Peninsula and provides a preliminary insight into the cultivation and husbandry practices in Castro Marim during the Iron Age.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. The R code and data used for the study can be accessed in the Supplementary Online Materials at https://osf.io/gntzb/ for reproducibility and transparency.

RP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GJ: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. FD: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ES: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. A-FM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 766311.

The ZooMS analysis was carried out by Samantha Presslee at BioArCh, University of York who gratefully acknowledges the use of the Ultraflex III MALDI-ToF/ToF instrument in the York Center of Excellence in Mass Spectrometry. The center was created thanks to a major capital investment through Science City York, supported by Yorkshire Forward with funds from the Northern Way Initiative, and subsequent support from EPSRC (EP/K039660/1 and EP/M028127/1). The authors would like to thank Rui Parreira and Frederico Tátá Regala for providing access to the samples (Direção Regional de Cultura do Algarve, Faro).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ambrose, S. H. (1990). Preparation and characterization of bone and tooth collagen for isotopic analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 17, 431–451. doi: 10.1016/0305-4403(90)90007-R

Arrastio, F. J. M. (1999). Conflictos y perspectivas en el periodo precolonial tartésico. Gerión. Rev. Histor. Antigua 17:149.

Arrastio, F. J. M. (2000). “Tartessos, estelas, modelos pesimistas,” in Intercambio y comercio preclásico en el Mediterráneo: Actas del I coloquio del CEFYP, Madrid, 9-12 de noviembre, 1998 (Centro de Estudios Fenicios y Púnicos), 153–174.

Arruda, A. M. (1996). “O Castelo de Castro Marim,” in In De Ulisses a Viriato. O primeiro milénio a.C.. (Lisboa: Ministério da Cultura, Instituto Português de Museus, Museu Nacional de Arqueologia), 95–100.

Arruda, A. M. (1997). Os núcleos urbanos litorais da Idade do Ferro no Algarve. Noventa Séculos entre a Serra e o Mar 12, 243–255.

Arruda, A. M. (2000). Los fenicios en Portugal. Fenicios y mundo indígena en el centro y sur de Portugal (siglos VIII-VI aC). Universidad Pompeu Fabra de Barcelona/Carrera Edició, SL.

Arruda, A. M. (2003). “Contributo da colonização fenícia para a domesticação da terra portuguesa,” in Ecohistoria del paisaje agrario-la agricultura fenicio-púnica en el mediterráneo, 205–217.

Arruda, A. M. (2009). Phoenician Colonization on the Atlantic Coast of the Iberian Peninsula. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226148489.003.0004

Arruda, A. M., and de Freitas, V. T. (2008). “O castelo de castro marim durante os séculos VI e V a n e,” in Sidereum Ana I: El río Guadiana en época Post-Orientalizante, 429–446.

Arruda, A. M., Ferreira, D., and Sousa, E. de (2020). A cerâmica grega do Castelo de Castro Marim. UNIARQ. Centro de Arqueologia da Universidade de Lisboa.

Arruda, A. M., Soares, A. M., Freitas, V. T., de Oliveira, C. F., Martins, J. M. M., and Portela, P. J. (2013). A cronologia relativa e absoluta da ocupação sidérica do Castelo de Castro Marim. Saguntum 45, 101–114. doi: 10.7203/SAGVNTVM.45.1978

Arruda, A. M., Viegas, C., Bargão, P., and Pereira, R. (2006). A importação de preparados de peixe em Castro Marim: Da Idade do Ferro à Época Romana. Setúbal Arqueol. 13, 153–176.

Aubet, M. E. (2001). The Phoenicians and the West: Politics, Colonies and Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Balasse, M., and Ambrose, S. H. (2005). Distinguishing sheep and goats using dental morphology and stable carbon isotopes in C4 grassland environments. J. Archaeol. Sci. 32, 691–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2004.11.013

Bocherens, H., and Drucker, D. (2003). Trophic level isotopic enrichment of carbon and nitrogen in bone collagen: Case studies from recent and ancient terrestrial ecosystems. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 13, 46–53. doi: 10.1002/oa.662

Boessneck, J., Müller, H.-H., and Teichert, M. (1964). Osteologische Unterscheidungsmerkmale zwischen Schaf (Ovis aries Linné) und Ziege (Capra hircus Linné). Verlag nicht ermittelbar.

Bogaard, A., Fraser, R., Heaton, T., Wallace, M., Vaiglova, P., Charles, M., et al. (2013). Crop manuring and intensive land management by Europe's first farmers. PNAS 110, 12589–12594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305918110

Bogaard, A., Heaton, T. H. E., Poulton, P., and Merbach, I. (2007). The impact of manuring on nitrogen isotope ratios in cereals: Archaeological implications for reconstruction of diet and crop management practices. J. Archaeol. Sci. 34, 335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2006.04.009

Bonafini, M., Pellegrini, M., Ditchfield, P., and Pollard, A. M. (2013). Investigation of the “canopy effect” in the isotope ecology of temperate woodlands. J. Archaeol. Sci. 40, 3926–3935. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2013.03.028

Buckley, M., Collins, M., Thomas-Oates, J., and Wilson, J. C. (2009). Species identification by analysis of bone collagen using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectr. 23, 3843–3854. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4316

Buckley, M., Whitcher Kansa, S., Howard, S., Campbell, S., Thomas-Oates, J., and Collins, M. (2010). Distinguishing between archaeological sheep and goat bones using a single collagen peptide. J. Archaeol. Sci. 37, 13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2009.08.020

Bull, J., Wanless, S., Elston, D. A., Daunt, F., Lewis, S., Harris, M. P., et al. (2004). Local-scale variability in the diet of Black-legged Kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla. Ardea 92, 43–52.

Cloern, J. E., Canuel, E. A., and Harris, D. (2002). Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope composition of aquatic and terrestrial plants of the San Francisco Bay estuarine system. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47, 713–729. doi: 10.4319/lo.2002.47.3.0713

Coplen, T. B. (2011). Guidelines and recommended terms for expression of stable-isotope-ratio and gas-ratio measurement results. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectr. 25, 2538–2560. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5129

Coulson, J. P., Bottrell, S. H., and Lee, J. A. (2005). Recreating atmospheric sulphur deposition histories from peat stratigraphy: diagenetic conditions required for signal preservation and reconstruction of past sulphur deposition in the Derbyshire Peak District, UK. Chem. Geol. 218, 223–248. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2005.01.003

Davis, S. (2007). The mammals and birds from the Iron Age and Roman periods of Castro Marim, Algarve, Portugal. Trabalhos do CIPA 107:61.

Dawson, T. J., and Ellis, B. A. (1996). Diets of mammalian herbivores in Australian arid, hilly shrublands: seasonal effects on overlap between euros (hill kangaroos), sheep and feral goats, and on dietary niche breadths and electivities. J. Arid Environ. 34, 491–506. doi: 10.1006/jare.1996.0127

de Sousa, E. (2019). The use of “Kouass Ware” during the Republican Period in the Algarve (Portugal). Rei Cretar. Roman. Fautor. Acta 41, 523–528.

DeNiro, M. J., and Epstein, S. (1978). Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 42, 495–506. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(78)90199-0

Deniro, M. J., and Epstein, S. (1981). Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 45, 341–351. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(81)90244-1

Dietler, M. (2009). Colonial Encounters in Iberia and the Western Mediterranean: An Exploratory Framework. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226148489.003.0001

Dixon, G. R. (2006). “Origins and diversity of Brassica and its relatives.” in Vegetable brassicas and related crucifers, ed. G. R. Dixon (Wallingford: CABI), 1–33. doi: 10.1079/9780851993959.0001

Eshel, T., Erel, Y., Yahalom-Mack, N., Tirosh, O., and Gilboa, A. (2019). Lead isotopes in silver reveal earliest Phoenician quest for metals in the west Mediterranean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 116:6007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1817951116

Farquhar, G. D., Ehleringer, J. R., and Hubick, K. T. (1989). Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant. Physiol. Plant. Mol. Biol. 40, 503–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.002443

Farquhar, G. D., O'Leary, M., and Berry, J. (1982). On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Functional Plant Biol. 9:121. doi: 10.1071/PP9820121

Fernández-Crespo, T., Ordoño, J., Bogaard, A., Llanos, A., and Schulting, R. (2019). A snapshot of subsistence in Iron Age Iberia: the case of La Hoya village. J. Archaeol. Sci. 28:102037. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.102037

Ferrio, J., Araus, J. L., Bux,ó, R., Voltas, J., and Bort, J. (2005). Water management practices and climate in ancient agriculture: Inferences from the stable isotope composition of archaeobotanical remains. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 14, 510–517. doi: 10.1007/s00334-005-0062-2

Ferrio, J., Voltas, J., Alonso, N., and Araus, J. L. (2007). Reconstruction of climate and crop conditions in the past based on the carbon isotope signature of archaeobotanical remains. Terrestr. Ecol. 1, 319–332. doi: 10.1016/S1936-7961(07)01020-2

Fiorentino, G., Ferrio, J. P., Bogaard, A., Araus, J. L., and Riehl, S. (2015). Stable isotopes in archaeobotanical research. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 24, 215–227. doi: 10.1007/s00334-014-0492-9

Fletcher, W. J. (2005). Holocene Landscape History of Southern Portugal. Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

Fletcher, W. J., Boski, T., and Moura, D. (2007). Palynological evidence for environmental and climatic change in the lower Guadiana valley, Portugal, during the last 13 000 dates. Holocene 17, 481–494. doi: 10.1177/0959683607077027

Fraser, R., Bogaard, A., Charles, M., Styring, A., Wallace, M., Jones, G., et al. (2013). Assessing natural variation and the effects of charring, burial and pre-treatment on the stable carbon and nitrogen isotope values of archaeobotanical cereals and pulses. J. Archaeol. Sci. 40, 4754–4766. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2013.01.032

Fraser, R. A., Bogaard, A., Heaton, T., Charles, M., Jones, G., Christensen, B. T., et al. (2011). Manuring and stable nitrogen isotope ratios in cereals and pulses: Towards a new archaeobotanical approach to the inference of land use and dietary practices. J. Archaeol. Sci. 38, 2790–2804. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2011.06.024

Froehle, A. W., Kellner, C. M., and Schoeninger, M. J. (2010). FOCUS: effect of diet and protein source on carbon stable isotope ratios in collagen: Follow up to Warinner and Tuross (2009). J. Archaeol. Sci. 37, 2662–2670. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2010.06.003

Gale, R., and Carruthers, W. (2000). “Charcoal and charred seed remains from Middle Palaeolithic levels at Gorham's and Vanguard Caves,” in Neanderthals on the Edge: Papers form a Conference Marking the 150th Anniversary of the Forbes' Quarry Discovery, Gibraltar (Oxford: Oxbow Books), 207–210.

Gebert, C., and Verheyden-Tixier, H. (2001). Variations of diet composition of Red Deer (Cervus elaphus L.) in Europe. Mamm. Rev. 31, 189–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2907.2001.00090.x

Gomes, F. B., and Arruda, A. M. (2018). On the edge of history? The early iron age of southern Portugal, between texts and archaeology. World Archaeol. 50, 764–780. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2019.1604258

Gómez Bellard, C. (2019). “Agriculture,” in The Oxford Handbook of The Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean (Oxford University Press), 732–745. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190499341.013.29

Gramazio, C. C., Laidlaw, D. H., and Schloss, K. B. (2017). Colorgorical: creating discriminable and preferable color palettes for information visualization. IEEE Trans. Visual. Comput. Graphics 23, 521–530. doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2016.2598918

Green, R. E. (1984). The feeding ecology and survival of partridge chicks (alectoris rufa and perdix perdix) on arable farmland in east anglia. J. Appl. Ecol. 21, 817–830. doi: 10.2307/2405049

Guiry, E., Noël, S., and Fowler, J. (2021). Archaeological herbivore δ13C and δ34S provide a marker for saltmarsh use and new insights into the process of 15N-enrichment in coastal plants. J. Archaeol. Sci. 125:105295. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2020.105295

Guiry, E. J., and Szpak, P. (2021). Improved quality control criteria for stable carbon and nitrogen isotope measurements of ancient bone collagen. J. Archaeol. Sci. 132:105416. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2021.105416

Hamilton, W. D., Sayle, K. L., Boyd, M. O. E., Haselgrove, C. C., and Cook, G. T. (2019). “Celtic cowboys” reborn: application of multi-isotopic analysis (δ13C, δ15N, and δ34S) to examine mobility and movement of animals within an Iron Age British society. J. Archaeol. Sci. 101, 189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2018.04.006

Haws, J. (2004). An Iberian perspective on Upper Paleolithic plant consumption. Promontoria 2, 49–106.

Heaton, T. H. E. (1987). The 15N/14N ratios of plants in South Africa and Namibia: relationship to climate and coastal/saline environments. Oecologia 74, 236–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00379365

Hedges, R. E. M., and Reynard, L. M. (2007). Nitrogen isotopes and the trophic level of humans in archaeology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 34, 1240–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2006.10.015

Hobson, K. A. (1999). Tracing origins and migration of wildlife using stable isotopes: a review. Oecologia 120, 314–326. doi: 10.1007/s004420050865

Jalut, G., Amat, A. E., Bonnet, L., Gauquelin, T., and Fontugne, M. (2000). Holocene climatic changes in the Western Mediterranean, from south-east France to south-east Spain. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 160, 255–290. doi: 10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00075-4

Kellner, C. M., and Schoeninger, M. J. (2007). A simple carbon isotope model for reconstructing prehistoric human diet. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 133, 1112–1127. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20618

Kohn, M. J. (2010). Carbon isotope compositions of terrestrial C3 plants as indicators of (paleo)ecology and (paleo)climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 19691–19695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004933107

Leegood, R. C. (2013). “Photosynthesis,” in Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry (Second Edition), eds. W. J. Lennarz and M. D. Lane (Waltham: Academic Press), 492–496. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-378630-2.00049-9

Longin, R. (1971). New method of collagen extraction for radiocarbon dating. Nature 230, 241–242. doi: 10.1038/230241a0

Magny, M., Miramont, C., and Sivan, O. (2002). Assessment of the impact of climate and anthropogenic factors on Holocene Mediterranean vegetation in Europe on the basis of palaeohydrological records. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 186, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/S0031-0182(02)00442-X

Martin, R. (1971). Recherches sur les agronomes latins et leurs conceptions économiques et sociales. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Mateus, J. (1992). Holocene and Present-Day Ecosystems of the Carvalhal Region, Southwest Portugal. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Mateus, J., and Queiroz, P. (1991). “Holocene palaeoecology of the North-littoral of Alentejo,” in Holocene Palaeoecology in Portugal, from the South-West Coast to the Serra da Estrela (Universidade de Lisboa), 80.

Mateus, J., and Queiroz, P. (2000). “Lakelets, lagoons and peat-mires in the coastal plane South of Lisbon–Palaeoecology of the Northern Littoral of Alentejo,” in Rapid environmental change in the Mediterranean Region - The contribution of the high-resolution lacustrine records from the last 80 millennia, (Sintra: Instituto Portugués de Arqueologia), 33–37.

McArdle, N., Liss, P., and Dennis, P. (1998). An isotopic study of atmospheric sulphur at three sites in Wales and at Mace Head, Eire. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 31079–31094. doi: 10.1029/98JD01664

Mizota, C., and Sasaki, A. (1996). Sulfur isotope composition of soils and fertilizers: differences between Northern and Southern hemispheres. Geoderma 71, 77–93. doi: 10.1016/0016-7061(95)00091-7

Moura, D., Gomes, A., Mendes, I., and Aníbal, J. (2017). Guadiana river estuary. Investigating the past, present and future. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.1/9887

Nehlich, O. (2015). The application of sulphur isotope analyses in archaeological research: a review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 142, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.12.002

Nehlich, O., Borić, D., Stefanović, S., and Richards, M. P. (2010). Sulphur isotope evidence for freshwater fish consumption: a case study from the Danube Gorges, SE Europe. J. Archaeol. Sci. 37, 1131–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2009.12.013

Nehlich, O., and Richards, M. P. (2009). Establishing collagen quality criteria for sulphur isotope analysis of archaeological bone collagen. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 1, 59–75. doi: 10.1007/s12520-009-0003-6

Neville, A. (1998). The Phoenicians in Iberia: Settlements, Cemetries, Trade and Agriculture. Doctoral dissertation, Trinity College Dublin.

Nitsch, E., Charles, M., and Bogaard, A. (2015). Calculating a statistically robust δ13C and δ15N offset for charred cereal and pulse seeds. STAR 1, 1–8. doi: 10.1179/2054892315Y.0000000001

Nitsch, E., Lamb, A., Heaton, T., Vaiglova, P., Fraser, R., Hartman, G., et al. (2019). The preservation and interpretation of δ34S values in charred archaeobotanical remains. Archaeometry 61, 161–178. doi: 10.1111/arcm.12388

Norman, A.-L., Anlauf, K., Hayden, K., Thompson, B., Brook, J. R., Li, S.-M., et al. (2006). Aerosol sulphate and its oxidation on the Pacific NW coast: S and O isotopes in PM2. 5. Atmos. Environ. 40, 2676–2689. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.09.085

Papachristou, T. (1997). Foraging behaviour of goats and sheep on Mediterranean kermes oak shrublands. Small Ruminant Res. 24, 85–93. doi: 10.1016/S0921-4488(96)00942-X

Payne, S. (1969). “A metrical distinction between sheep and goat metacarpals,” in The Domestication and Exploitation of Plants and Animals, 295–305. doi: 10.4324/9781315131825-24

Peña-Chocarro, L., Pérez- Jordà, G., Alonso, N., Antolín, F., Teira-Brión, A., Tereso, J. P., et al. (2019). Roman and medieval crops in the Iberian Peninsula: a first overview of seeds and fruits from archaeological sites. Quarter. Int. 499, 49–66. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2017.09.037

Perez-Hurtado, A., Goss-Custard, J. D., and Garcia, F. (1997). The diet of wintering waders in Cádiz Bay, southwest Spain. Bird Study 44, 45–52. doi: 10.1080/00063659709461037

Price, G. C., Krigbaum, J., and Shelton, K. (2017). Stable isotopes and discriminating tastes: faunal management practices at the Late Bronze Age settlement of Mycenae, Greece. J. Archaeol. Sci. 14, 116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.05.034

Pyankov, V., Ziegler, H., Akhani, H., Deigele, C., and Lüttge, U. (2010). European plants with C4 photosynthesis: geographical and taxonomic distribution and relations to climate parameters. Botanical J. Linnean Soc. 163, 283–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2010.01062.x

Queiroz, P., Mateus, J., Leeuwaarden, W., Pereira, T., and Dise, D. (2006). Castro Marim e o seu território imediato durante a Antiguidade. Paleo-etno-Botânica. Relatório Final.

Queiroz, P. F. (1999). Ecologia histórica da paisagem do Noroeste Alentejano. Lisboa: University of Lisbon.

R Core Team (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Reitsema, L. J., Kozłowski, T., and Makowiecki, D. (2013). Human–environment interactions in medieval Poland: a perspective from the analysis of faunal stable isotope ratios. J. Archaeol. Sci. 40, 3636–3646. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2013.04.015

Renzi, M., Rovira Llorens, S., and Montero Ruiz, I. (2012). Riflessioni sulla metallurgia fenicia dell'argento nella Penisola Iberica. Comune di Bergamo.

Richards, M. P., and Hedges, R. E. M. (1999). Stable isotope evidence for similarities in the types of marine foods used by late mesolithic humans at sites along the Atlantic coast of Europe. J. Archaeol. Sci. 26, 717–722. doi: 10.1006/jasc.1998.0387

Riehl, S. (2009). Archaeobotanical evidence for the interrelationship of agricultural decision-making and climate change in the ancient Near East. Quater. Int. 197, 93–114. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2007.08.005

Roller, D. W. (2014). The Geography of Strabo: An English Translation, with Introduction and Notes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rutter, S. M. (2002). “Behaviour of sheep and goats,” in The ethology of domestic animals: An introductory text, 148–155. doi: 10.1079/9780851996028.0145

Schoeninger, M. J. (1985). Trophic level effects on 15N/14N and 13C/12C ratios in bone collagen and strontium levels in bone mineral. J. Hum. Evol. 14, 515–525. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2484(85)80030-0

Schulting, R. J., le Roux, P., Gan, Y. M., Pouncett, J., Hamilton, J., Snoeck, C., et al. (2019). The ups and downs of Iron Age animal management on the Oxfordshire Ridgeway, south-central England: a multi-isotope approach. J. Archaeol. Sci. 101, 199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2018.09.006

Semmler, M. E. A. (1990). “Cerro del Villar 1987. Informe de la primera campaña de excavaciones en el asentamiento fenicio de la desembocadura del río Guadalhorce (Málaga),” in Anuario arqueológico de Andalucía 1987, 310–316.

Semmler, M. E. A. (1992). “Proyecto Cerro del Villar (Guadalhorce, Málaga): Estudio de materiales 1990,” in Anuario arqueológico de Andalucía 1990, 304–306.

Smith, B. N., and Epstein, S. (1970). Biogeochemistry of the stable isotopes of hydrogen and carbon in salt marsh biota. Plant Physiol. 46, 738–742. doi: 10.1104/pp.46.5.738

Snow, D., Perrins, C. M., and Gillmor, R. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic: Concise Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sousa, A. C., and Gonçalves, V. S. (2022). “Changements et permanences des rites funéraires dans les anciennes sociétés paysannes du centre et du sud du Portugal,” in Sépultures and Rites Funeraires/Sepulture è riti funerari. Actes du colloque organisé par l'Association de Recherches Préhistoriques et Protohistoriques Corses (ARPPC) Calvi - 2019, 149–192. Available at: https://repositorio.ul.pt/handle/10451/53998

Strohalm, M., Kavan, D., Novák, P., Volný, M., and Havlíček, V. (2010). mMass 3: a cross-platform software environment for precise analysis of mass spectrometric data. Anal. Chem. 82, 4648–4651. doi: 10.1021/ac100818g

Styring, A., Rösch, M., Stephan, E., Stika, H.-P., Fischer, E., Sillmann, M., et al. (2017). Centralisation and long-term change in farming regimes: comparing agricultural practices in Neolithic and Iron Age south-west Germany. Proc. Prehist. Soc. 83, 357–381. doi: 10.1017/ppr.2017.3

Tieszen, L. L. (1991). Natural variations in the carbon isotope values of plants: Implications for archaeology, ecology, and paleoecology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 18, 227–248. doi: 10.1016/0305-4403(91)90063-U

Tobyn, G., Denham, A., and Whitelegg, M. (2011). “CHAPTER 9 - Apium graveolens, wild celery,” in Medical Herbs, eds. G. Tobyn, A. Denham, and M. Whitelegg (Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone), 79–89. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-10344-5.00014-8

Treumann, B. (1998). The role of wood in the rise and decline of the Phoenician settlements on the Iberian Peninsula. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Treumann, B. (2009). “Lumbermen and shipwrights: Phoenicians on the Mediterranean coast of southern Spain,” in Colonial Encounters in Ancient Iberia: Phoenician, Greek, and Indigenous Relations, eds. M. Dietler, and C. Lopez-Ruiz (Chicago, IL: Chicago Scholarship). doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226148489.003.0007

Uriel, P. F. (2000). “El comercio de la púrpura,” in Intercambio y comercio preclásico en el Mediterráneo: actas del I coloquio del CEFYP, Madrid, 9-12 de noviembre, 1998 (Centro de Estudios Fenicios y Púnicos), 271–280.

van Doorn, N. L., Hollund, H., and Collins, M. J. (2011). A novel and non-destructive approach for ZooMS analysis: ammonium bicarbonate buffer extraction. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 3, 281–289. doi: 10.1007/s12520-011-0067-y

van Klinken, G. J. (1999). Bone collagen quality indicators for palaeodietary and radiocarbon measurements. J. Archaeol. Sci. 26, 687–695. doi: 10.1006/jasc.1998.0385

Van Leeuwaarden, W., and Janssen, C. R. (1985). “A preliminary palynological study of peat deposits near an oppidum in the Lower Tagus Valley, Portugal,” in Actas 225–236.

Wachsmann, S., Dunn, R. K., Hale, J. R., Hohlfelder, R. L., Conyers, L. B., Ernenwein, E. G., et al. (2009). The palaeo-environmental contexts of three possible phoenician anchorages in Portugal. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 38, 221–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-9270.2009.00224.x

Wagner, C. G., and Alvar, J. (1989). Fenicios en Occidente: La colonización agrícola. Riv. Studi Fenici 17, 61–102.

Wagner, C. G., and Alvar, J. (2003). La colonización agrícola en la Península Ibérica. Estado de la cuestión y nuevas perspectivas. Ecohist. Paisaje Agrar 95, 187–204.

Wakshal, E., and Nielsen, H. (1982). Variations of δ34S(SO4), δ18O(H2O) and Cl/SO4 ratio in rainwater over northern Israel, from the Mediterranean Coast to Jordan Rift Valley and Golan Heights. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 61, 272–282.