- 1Carbon Neutrality Research Group, University of Southampton Malaysia, Iskandar Puteri, Malaysia

- 2Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

Omnidirectionality and simple design make VAWTs more attractive compared to HAWTs in highly turbulent and harsh operational environments including low wind speed conditions where this technology shines more. However, the performance of VAWTs is lacking compared to HAWTs due to low turbine efficiency at downstream caused by large wake vortices generated by advancing blades in the upstream position. Introducing variable design methods on VAWT provides better adaptability to the various oncoming wind conditions. This paper presents state-of-the-art variable methods for performance enhancement of VAWTs to provide better direction for the wind industry. The variable VAWT design can increase the lift and torque, especially at the downstream regions by managing the blade-to-wake interaction and blade angle of attack (AoA) well, hence contributing to the performance enhancement of VAWTs. In addition, the self-starting capabilities have also been found to improve by employing variable methods with a better angle of attack on the turbine blades. Nevertheless, the complexity of varying mechanisms and structural rigidity are the main challenges in adopting this idea. Yet, it possesses great potential to develop higher-efficiency VAWT systems that can operate in a wide range of wind speeds.

1 Introduction

Vertical axis wind turbines (VAWTs) have gained renewed attention due to global efforts to reduce fossil fuel consumption and combat climate change. Wind turbines are broadly categorized into two types based on their rotational axis: horizontal-axis wind turbines (HAWTs) and vertical axis wind turbines (VAWTs) (Li et al., 2015; Rezaeiha et al., 2018a; Sagharichi et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2019; Hand et al., 2021; McKenna et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2022). The HAWTs dominate the market (Manwell, 2009; Li et al., 2015; Santamaría et al., 2022) due to their higher efficiency compared to VAWTs (Hand et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021). The performance limitations of VAWTs arise from turbulent flow characteristics resulting from blade rotation (Zhu et al., 2022), including issues like tip vortices and dynamic stall (Rezaeiha et al., 2018a). Despite these challenges, VAWTs possess several advantages:

(1) Omni-directional capabilities (Li et al., 2015; Rezaeiha et al., 2018a; Liu et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2022).

(2) Low wind speed capabilities.

(3) Lower manufacturing costs (Zhu et al., 2018a; Zhao et al., 2022).

(4) Lower maintenance as yaw is absent in VAWTs (Li et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2018a; Zhao et al., 2022).

(5) Closer to energy storage centres, which helps reduce transmission losses (Li et al., 2015).

(6) Lower noise emission (Li et al., 2015; Rezaeiha et al., 2018a; Liu et al., 2019; Battisti, 2021; Zhao et al., 2022).

(7) Requires small operational area (Li et al., 2015; Rezaeiha et al., 2018a; Zhao et al., 2022).

These advantages make VAWTs a viable option, particularly in confined and turbulent spaces such as urban environments (Hand et al., 2021) and areas with significant wake-to-wake turbine interactions (Whittlesey et al., 2010; Kinzel et al., 2012). The simplistic design of VAWT offers better adaptability to changing wind conditions, providing increased reliability (Belabes and Paraschivoiu, 2021; Hand et al., 2021). They are considered less intrusive in urban environments compared to HAWTs, contributing to their growing popularity (Hand et al., 2021). Recent research efforts, such as studies (Islam et al., 2008a; Bianchini et al., 2015; Rezaeiha et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2019; Su et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021; Zhang and Qu, 2021; Azadani and Saleh, 2022), indicate a renewed focus on optimizing the aerodynamic efficiency of VAWTs for improved power harnessing, despite being overshadowed by HAWTs in the past decade.

VAWTs can be classified into two main types: lift-based turbines, such as Darrieus VAWTs, and drag-based turbines, including Savonius rotors, cup-type turbines, and crossflow turbines. Darrieus VAWTs feature aerofoil blades suspended at a distance from the shaft, generating lift through the interaction between the incoming wind and the aerofoils. Whereas the Savonius turbines, with concave vanes resembling the letter “S,” rely on drag forces to rotate and are often chosen for low-wind applications due to their self-starting capabilities (Manwell, 2009; Mathew and Philip, 2012; Bouzaher and Guerira, 2022; Zhao et al., 2022).

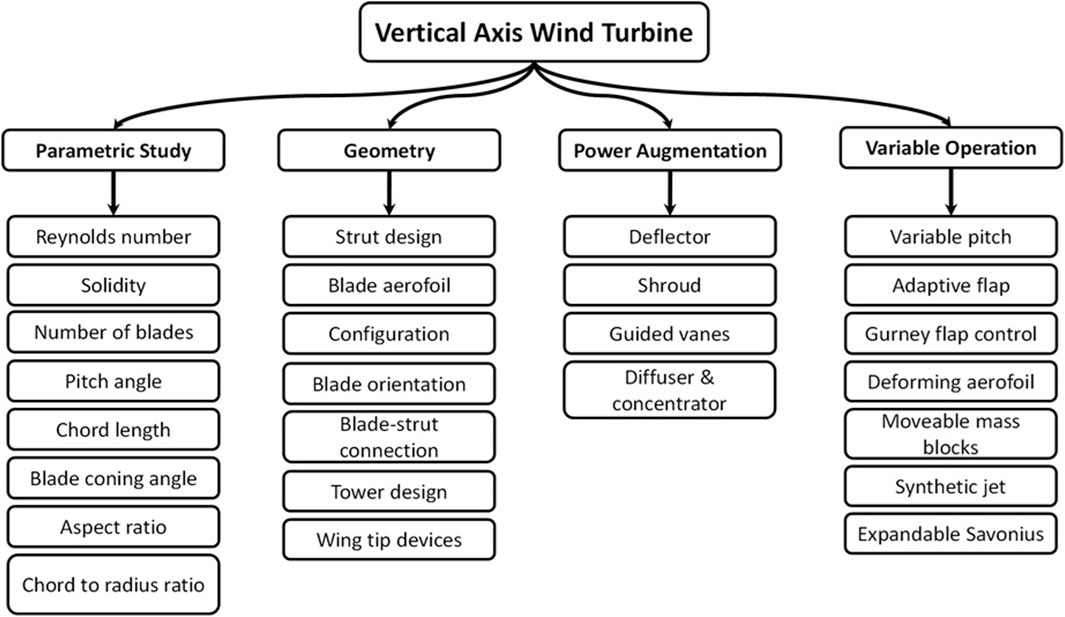

As shown in Figure 1, improvements in VAWT power output can be achieved through aerodynamic enhancements. Parametric and geometric studies, such as adjusting pitch angle (Fiedler and Tullis, 2009; Chen and Kuo, 2012; Guo et al., 2019), blade profile (Chen and Kuo, 2012; Danao et al., 2012; Roh and Kang, 2013; Mitchell et al., 2021; Ung et al., 2022; Abdalkarem et al., 2023), chord-to-radius ratio (Strickland et al., 1979; Rainbird et al., 2015; Bianchini et al., 2016), number of blades (Li et al., 2015; Qa et al., 2016; Rezaeiha et al., 2018b; Sarath Kumar et al., 2020), and rotor height (Brusca et al., 2014), contribute to optimizing turbine performance. Additionally, power augmentation methods involve incorporating additional components like deflectors, shrouds, guide vanes, diffusers, and concentrators to accelerate the incoming wind and enhance power generation (Wong et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2018a; Wong et al., 2018b; Wang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022).

The next approach involves varying design parameters based on the oncoming wind speed. Variable design in VAWTs refers to a method where a parameter or geometry of the turbine changes during operation to enhance performance. This adaptive approach allows the turbine to adjust its parameters for optimal efficiency, expanding the range of freestream velocities it can capture. Various variable design features have been implemented in VAWTs, including variable pitch (Kirke and Lazauskas, 2011; Sheng et al., 2013; Elkhoury et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Rezaeiha et al., 2017; Manfrida and Talluri, 2020; Aboelezz et al., 2022), variable gurney flaps at the trailing edge (Hao et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2022a), active flow control at the airfoil’s leading edge (Rezaeiha et al., 2019; Sun and Huang, 2021; Liu et al., 2022b), and variable oscillating flap blades (Xiao et al., 2013). These variable features can be categorized into passive and active controls (Li et al., 2015; Santamaría et al., 2022), where passive flow control involves mechanisms that vary parameters without a motor or actuator, while active control employs additional input power, such as a motor (Burton et al., 2001). The implementation of variable features in VAWTs has demonstrated an increase in the measured output coefficient of power (

Review works have been done for VAWT parametric (Islam et al., 2008a; El-Samanoudy et al., 2010; Aslam Bhutta et al., 2012; Hand et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2022) and power augmentation study (Ouro et al., 2018; Bianchini et al., 2019; Bontempo et al., 2021; Villeneuve et al., 2021). However, there is a notable absence of review work specifically addressing the variable design of VAWTs. A variable operation involves chosen parameters or shapes constantly adapting to the oncoming wind while completing a single rotation. Therefore, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive review and evaluation of various variable designs for VAWTs from an aerodynamic perspective. To commence, Section 2 outlines the fundamental principles and governing equations of a VAWT. In Section 3, a detailed analysis of different variable systems employed in VAWTs is presented, highlighting their advantages, disadvantages, and other relevant findings. Section 4 discusses the future outlook of variable designs for VAWTs, and the paper concludes with Section 5.

2 Principles of VAWT

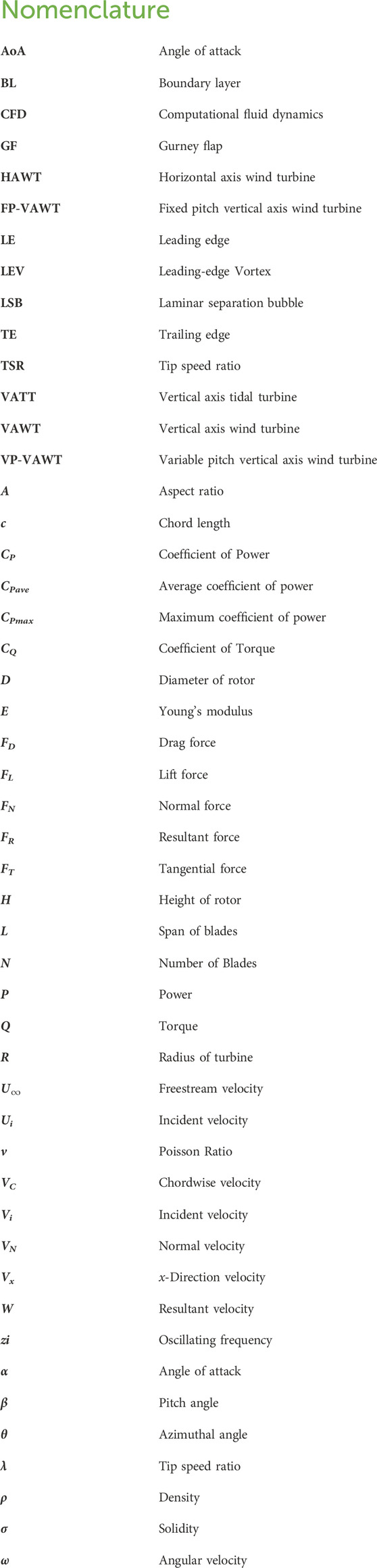

The governing principles for all lift-type VAWTs are consistent (Zhao et al., 2022). The upstream region consists of Quadrants 1 and 2, while the downstream region is referred to as quadrants 3 and 4 (Figure 2). Figure 2A illustrates a simple two-bladed H-Darrieus VAWT, and the forces form the basis of VAWT mechanics. As VAWTs are dependent on the freestream velocity (

Figure 2. Principles of VAWT (A) Free-body diagram of a 2-bladed H-Darrieus turbine. (B) Aerodynamics of a single aerofoil.

As illustrated in Figure 2,

Tip speed ratio (TSR,

Angle of attack,

To measure the performance of any VAWT, the coefficient of moment (CQ) and power (CP) can be calculated and used as parameters to assess efficiency. Eq. 8 describes the moment coefficient where

Similarly, power coefficient is represented in Eq. 9.

Solidity, σ, is define through Eq. 11, where N is the number of blades, c represents the blade chord length, and D is the turbine rotor diameter (Manwell, 2009; Carrigan et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015; Hassan et al., 2016; Sagharichi et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2022). This equation characterizes how tightly dense the rotors are when interacting with the oncoming wind (Rezaeiha et al., 2018b; Zhao et al., 2022). In cases where the turbine has high solidity, less freestream wind can pass through the rotor, making the turbine more solid, and vice versa.

Solidity plays a crucial role in VAWT performance, influencing wake-to-wake interaction, self-starting capability, and optimal operational TSR (Sagharichi et al., 2018). In contrast, low-solidity turbines are preferable in high-wind conditions for increased CP.

3 Variable design

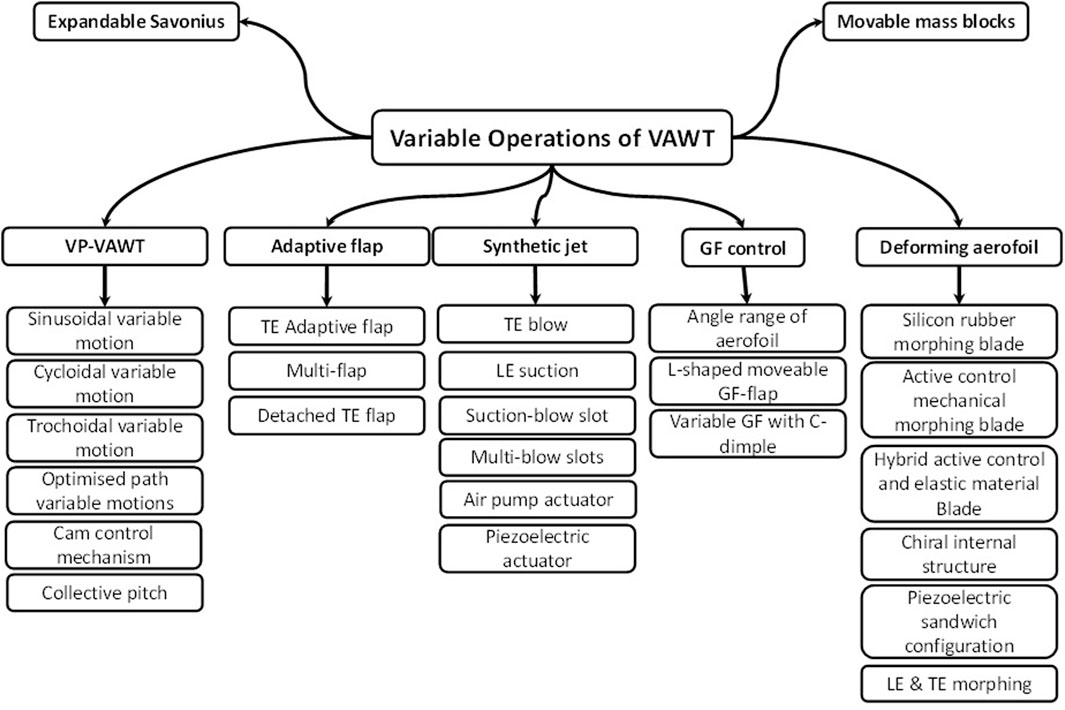

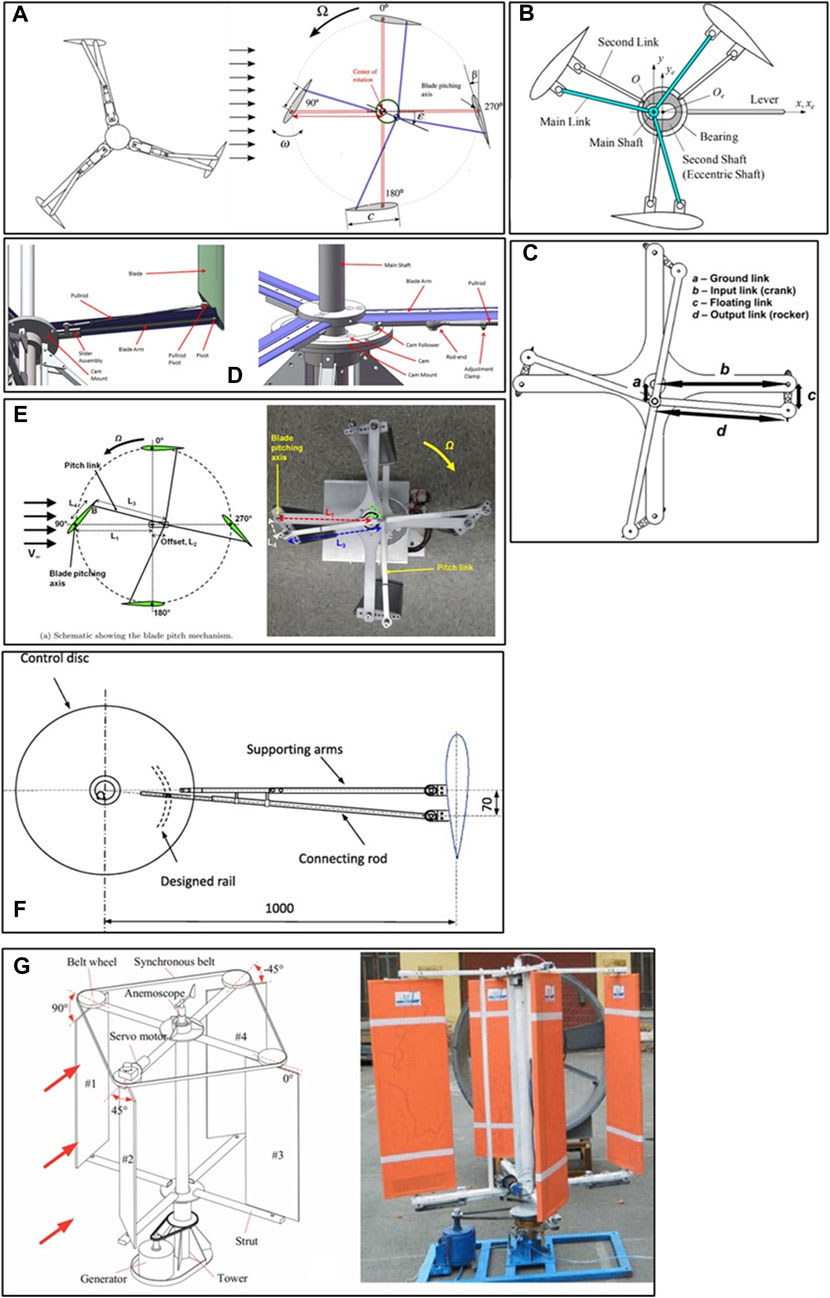

This section comprehensively reviews variable designs for VAWT applications, encompassing H-Darrieus and Savonius turbines. Each subchapter provides a detailed review, including variable control mechanisms. Figure 3 illustrates the anatomy of variable designs in VAWTs.

3.1 Variable pitch (VP)

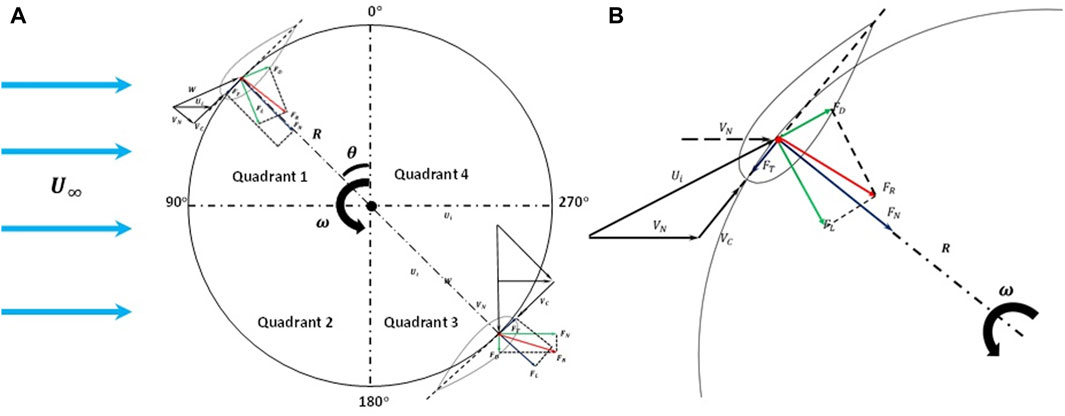

Studies on fixed-pitch vertical axis wind turbines (FP-VAWTs) have indicated an increase in power yield (Bianchini et al., 2015; Rezaeiha et al., 2017). Rezaeiha et al. (Rezaeiha et al., 2017), investigated a NACA 0018 3-bladed H-turbine and observed a 6% increase in CP and up to 2% increase in CQ with a pitch angle (β) of −2°. Zhang et al. (Zhang L. et al., 2021) reported a 2.88% increase in power compared to a turbine with

variable pitch (VP) motions consist of sinusoidal (Figure 4A) and cycloidal (Figure 4B) methods (Zhao et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2022). In the sinusoidal VP method, the blades’ pitch angle varies in the shape of a sinusoidal function across azimuthal angles (Pawsey, 2002; Paraschivoiu et al., 2009). This motion help keep the blades below stall conditions at critical azimuthal regions, particularly towards the downwind direction. Although this variation improves lift forces by maintaining local angle of attack (AoA) below stall angles, the sudden change in pitch angle has the potential to induce mechanical fatigue loading, reducing the operational life of the turbine (Zhao et al., 2018). Despite these potential disadvantages, research on VP-VAWT has demonstrated significant improvements, with a 30% increase in power generation compare to an FP-VAWT (Paraschivoiu et al., 2009). Esfahani et al. (2015) also show increase propulsion force using an elliptical motion trajectory base on a sinusoidal motion on a single aerofoil.

Figure 4. Variable pitch systems: (A) Sinusoidal, (B) Cycloidal variable motion (Zhao et al., 2018), (C) newly proposed variable pitch motion (Zhao et al., 2018) and (D) the comparison of CP between the variable Trochoidal motion turbine to fixed pitch. (Zouzou et al., 2019).

The cycloidal method depicted in Figure 4B was based on the Voith-Schneider system (Camporeale and Magi, 2000), commonly applied in hydro-turbines or vertical axis tidal turbines (VATT). Performance studies for cycloidal actuation have shown a higher power yield than a fixed turbine. Hwang et al. (2009) reported a 25% increase in turbine performance with an active control cycloidal design. However, the sinusoidal motion generally yields higher performance than the cycloidal motion. Zhao et al., 2018 proposed a new variable pitch method that allowed the turbine to remain at maximum power output for an extended duration, this resulted an 18.9% increase in power at a TSR of 4.5. This method outperformed an FP-VAWT, with a 50% surged in CP (Figure 4C). A similar approach by Manfrida and Talluri (Manfrida and Talluri, 2020) introduced a dynamic pitching law, did not yield significant improvement compared to the sinusoidal VP motion.

Innovative control methods, such as the variable pitch trochoidal motion proposed by (Xu et al., 2019a; Zouzou et al., 2019), aimed to enhance variable pitch designs. The trochoidal motion positions the blades at 0° pitch angles at 90° and 270° azimuthal positions, lead to significant improvements in CP. Experimental results indicated an operational range for this turbine at lower TSRs between 0.4 and 0.7, similar to the operating range of a Savonius turbine in low wind conditions (Figure 4D). Despite a 30% reduction in CP, attributed to mechanical inefficiencies during experiments, the VP H-VAWT in this study outperformed the Savonius turbine in low wind conditions. Elkhoury et al. (2015) also reported mechanical losses contributing to lower power generation at higher TSRs.

Eq. 12 proposed by Xu et al. (2019b) led to a 78.6% increase in maximum power compared to a fixed-pitch turbine. In wind tunnel tests, the optimised control outperformed the sinusoidal variable pitch method by 45.5% in CPmax during the wind tunnel test. This equation, linked pitch angle to azimuthal blade angle, allows researchers to determine the optimal blade pitch at various azimuthal positions.

Where

Several researchers (Paraschivoiu et al., 2009; Sheng et al., 2013; Jakubowski et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2018; Manfrida and Talluri, 2020; Zhang L. et al., 2021; Guevara et al., 2021) have propose various mathematical approaches to optimize pitch angles. Numerical tools such as artificial neural networks (ANN) (Abdalrahman et al., 2017) and genetic algorithm (GA) (Li et al., 2018; De Tavernier et al., 2019) are used for optimising variable pitch settings. However, these approaches are only simulated results, and experimental validation is yet to be conducted (Li et al., 2018). Furthermore, the wind energy industry has not yet standardize to a singular equation that relates blade pitch angle, AoA, and azimuthal angle.

The benefits of VP control include delaying dynamic stall development by enlarging the leading-edge vortex (LEV) with optimal AoA, resulting in increased lift. This approach mitigates vortex shedding, reducing blade wake-to-wake interactions and drag forces (Zouzou et al., 2019; Rainone et al., 2023). Variable pitch designs also exhibit better self-starting capabilities (Erickson et al., 2012; Elkhoury et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Sagharichi et al., 2016; Sagharichi et al., 2018; Sagharichi et al., 2019; Guevara et al., 2021), widening the operational range of the turbine (Erickson et al., 2012). Additionally, VP control proves useful for preventing damage from operation beyond the recommended wind working range through aerodynamic braking (Paraschivoiu et al., 2009; Kirke and Lazauskas, 2011; Lazauskas and Kirke, 2012; Jain and Abhishek, 2016; Sagharichi et al., 2016). However, the developmental cost may outweigh the advantages (Paraschivoiu et al., 2009). Simulation studies indicate that VP-Vertical Axis Wind Turbines (VAWTs) may lose omnidirectional abilities, especially when the wind comes from the advancing side. The addition of a yawing mechanism may suggests its limitation (Jain and Abhishek, 2016). Performance declines noticeably if the wind comes from the advancing side, and a yawing mechanism was suggested to be added. Despite promising performance yields, mechanical control systems remain a significant challenge for market readiness. Recommendations to install sensors on each blade to enhance turbine efficiency (Staelens et al., 2003).

Figure 5 illustrates various control mechanisms for variable pitch, employing rotational disks or cams mounted on the shaft to guide linkage bars. The design by (Kiwata et al., 2010) using a 4-bar linkage shows insignificant improvement in self-starting capabilities for the FP-VAWT but achieve higher rotational velocity. Figure 5G depicts a collective pitch control system with a rubber belt linking the blades, controlled by a servo motor. Experimental data evidence a 20%–30% lower output than simulation results, attributes to mechanical and aerodynamic losses such as friction and vortex shedding (Zhang et al., 2015). Long-term fatigue stresses from abrupt dynamic loading during pitch changes could be a potential issue over time (Zhao et al., 2018). Both active and passive control methods contribute to the total weight of the turbine, and an increase in moving parts introduces points of failure and friction. Findings to skin friction to be influential in limiting the turbine’s predicted performance (Xu et al., 2019b).

Figure 5. Design of variable pitch control mechanisms by (A) Sagharichi, et al. (Sagharichi et al., 2018) (B) Kiwata et al. (Kiwata et al., 2010) (C) Jain and Abhishek (Jain and Abhishek, 2016) (D) Benedict, et al. (Benedict et al., 2013) (E) Erickson, et all (Erickson et al., 2012). (F) Xu, et al. (Xu et al., 2019a; Xu et al., 2019b). (G) Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2015).

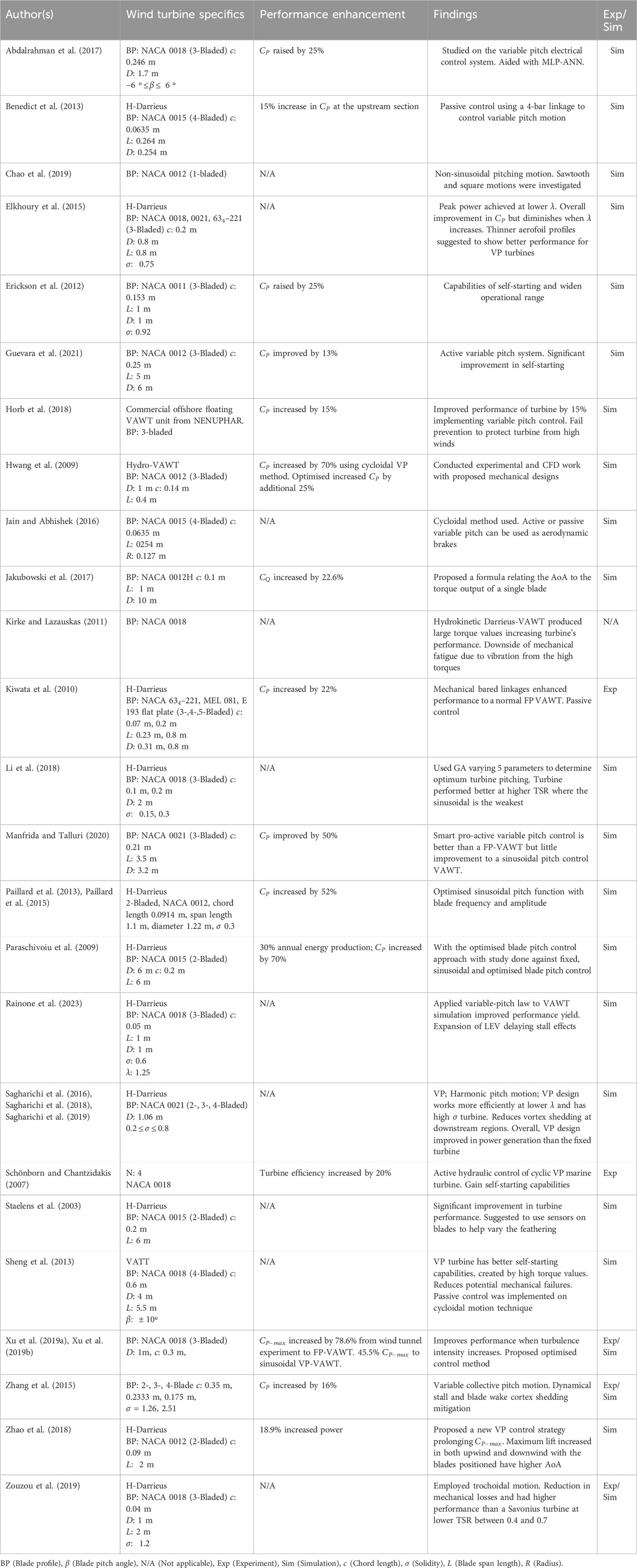

The implementation of VP-VAWT, requires careful consideration of factors such as wind speed, control methods, and mechanisms. For high TSRs, sinusoidal, cycloidal, or collective pitch motions have been applied effectively in high-wind areas. In contrast, the trochoidal system has shown effectiveness at low TSRs (Zouzou et al., 2019). The 4-barred linkage mechanism, illustrated in Figures 5A–G, is a commonly employed method. Less popular approaches, like the collective pitch system shown in Figure 5G, may be less suitable for practical applications. For active control, a servo-controlled system is an option, but it comes with the drawback of consuming power, reducing the net power generated, especially in low-wind conditions. In contrast, a passive mechanical control might be more suitable for low-wind scenarios, as it involves fewer moving parts, leading to reduce maintenance issues. Active control methods are generally better suited for high-wind conditions. While most studies have relied on simulations and control experiments, there is a need for real-world testing to gain a deeper understanding of this system. Testing in open environments with actual wind scenarios could provide valuable insights. Exploring the application of VP motion beyond H-VAWT to wind farming applications is a potential avenue for further development. Establishing a standard equation or control for determining optimal pitch variations could be beneficial for VAWT designers (MacPhee D. and Beyene A., 2016). However, the commercial development of a reliable and affordable variable pitch system remains a challenge due to the complexity of the control mechanism (Zhu, 2007). Table 1 provides a summary of VP-VAWT methods.

3.2 Adaptive flap

Inducing lift on an aerofoil can be achieved by adding flaps, a method commonly used in fixed-wing aircraft. Trailing edge (TE) flaps on the suction side had been experimentally and numerically confirmed to improve lift by 10% on a glider (Meyer et al., 2007), preventing recirculation of flow towards the leading edge and delaying early flow separation (Meyer et al., 2007; Wang and Schlüter, 2012; Bechert et al., 1997; D and Singh, 2016; Schluter, 2010; Kernstine et al., 2008; Bramesfeld and Maughmer, 2002). This section explores the different approaches to implementing variable adaptive flaps for VAWT.

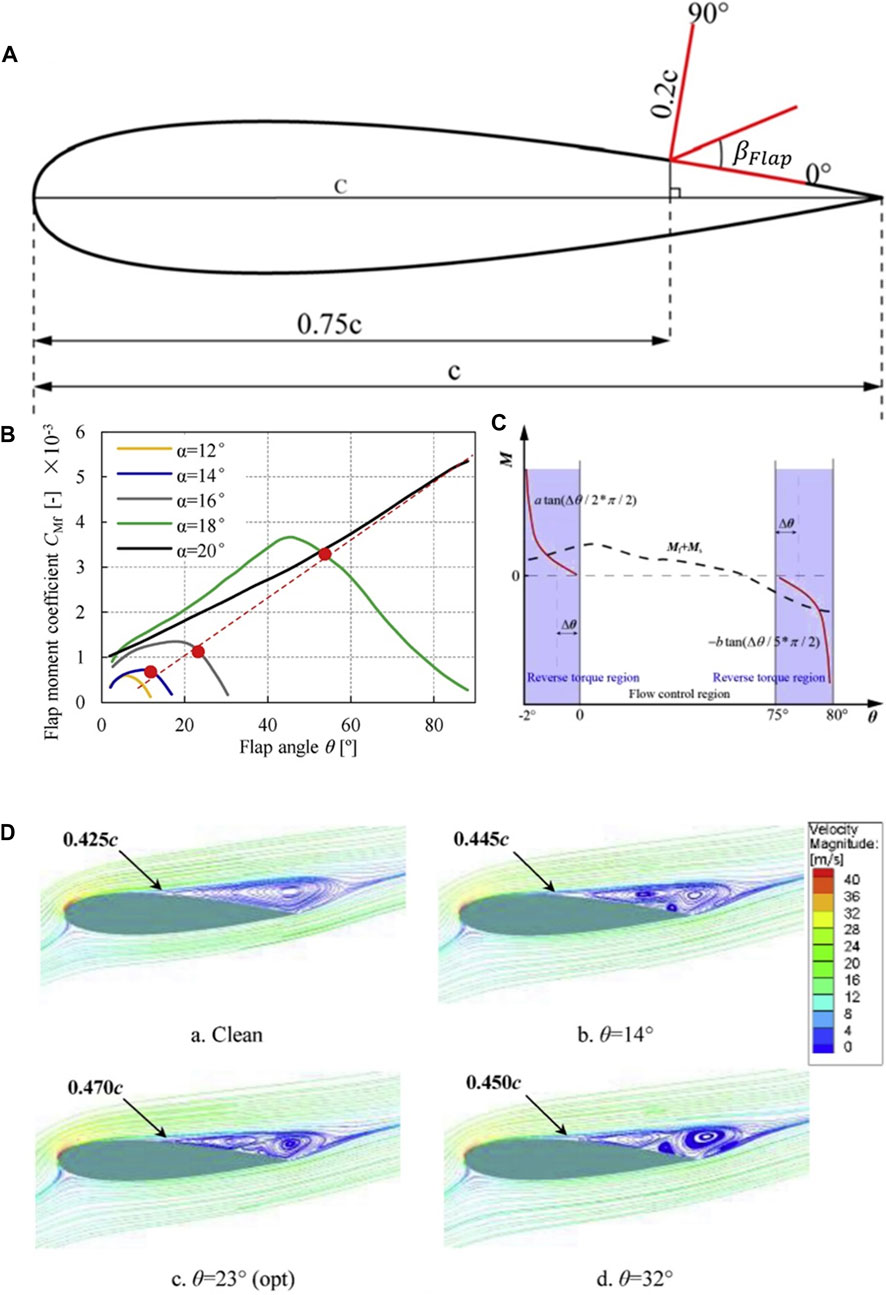

In a numerical parametric study, Liu et al. (2019) utilized a static TE flap positioned on the upper surface of an aerofoil to alleviate flow separation (Figure 6A). At a flap angle of 23°, the flow separation region decreased by 12%, and the separation point was postponed to 0.407c from 0.425c. This resulted in the elimination of recirculation flow at the TE. Free flap pitching showed that moments on the flap initially increased and then decreased with increasing AoA.

Figure 6. Adaptive flap studies on the (A) trailing edge adaptive flap motion (adapted from Liu et al. (2019), (B) variations of flap CM at different flap position angles, (C) flap moment operational control and (D) streamline velocity contour of flap angles of 0

Shown in Figure 6B, Hao et al. (Hao et al., 2019; Hao and Li, 2020) introduced an adaptive flap method with a self-adjustable flap angle based on the blade’s (AoA). In Figure 6B, the moment of the flap increased as flap angle reach its maximum. The blade’s AoA rose to 20°, indicating significant boundary layer separation. Figure 6C illustrates the operational conditions of the adaptive flap method, and Figure 6D shows velocity streamline plots at different flap angles. Optimal flap angles delayed separation and reduced wak e interactions between blades. The spring control system was explored, but potential mechanical failures and long-term fatigue loadings were identified as concerns. Eq. 13 outlines the linear torque control approach, establishing a direct relationship between the coefficient of moment of the flap (

As pressure at the bottom surface of the flap remains constant, pressure on the upper side decreases slowly, preventing flow separation from moving toward the LE. When

Where

In a study investigating flap length, chordwise position, and the number of flaps, Hao et al., 2019 differentiated between medium BL separation (14°≤ AoA ≤16°) and large BL separation (AoA = 20°). For medium BL separation, the flap’s chordwise position was optimal towards the TE. Conversely, at large BL separation, the flap position should be closer towards the leading edge (LE) for effectiveness, resulted in a 41% increase in the CL (Hao et al., 2019). The flap length needed to be carefully selected to prevent flow recirculation spillage, as excessive backflow from the TE to the LE can lead to early flow separation. Additionally, an overly long flap can be considered wasteful in manufacturing and may require more force and power to move.

The double flap configuration significantly outperformed the single flap, showing a 44% and 9.3% improvement at an AoA of 20° and 18° respectively. This configuration addressed issues seen in the single flap setup, reducing the formation of turbulent eddies at high AoAs. An added advantage was the lower noise emission of the adaptive flap system (Liu et al., 2019).

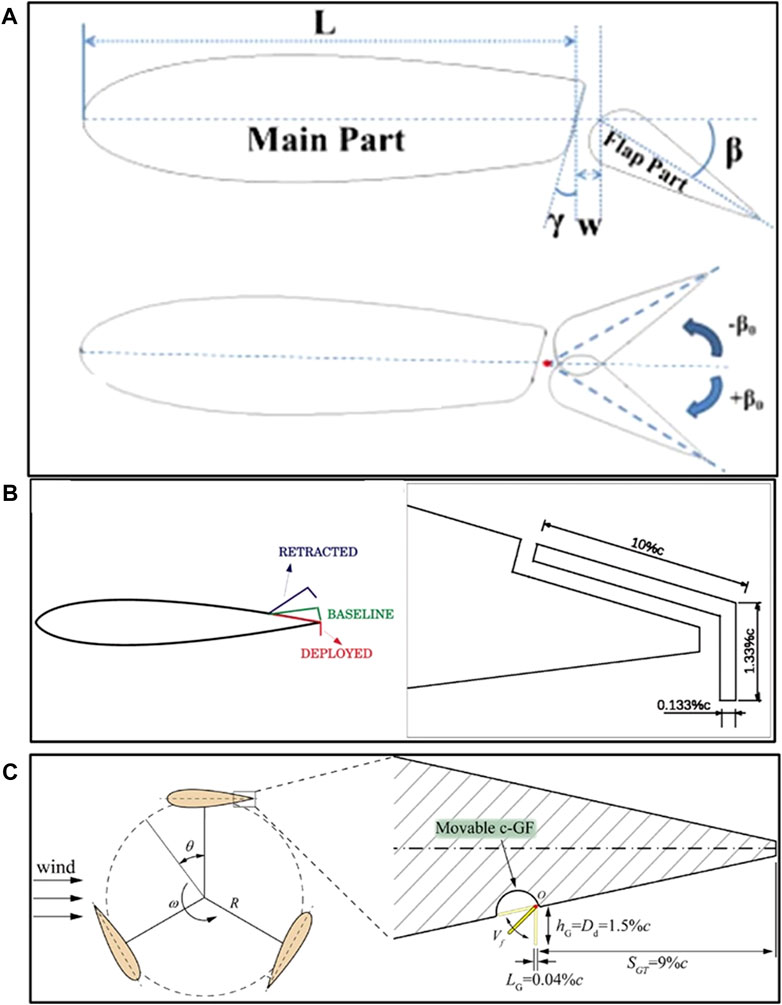

Figure 7A illustrates the second category of adaptive flap where the trailing edge moves independently to the main aerofoil body. This concept is introduced by Xiao et al. (Xiao et al., 2013) in VATT application and holds potential for performance enhancement in hydrofoil turbines (Zhou et al., 2021). Simulation work discovers about 28% improvement in turbine’s performance. In Figure 7A, w represents the slot width and

Figure 7. Other innovative methods of employing an adaptive flap design like (A) oscillating variable flap (Xiao et al., 2013), (B) L-shaped moveable GF-flap (Motta et al., 2016) and (C) movable GF with C-dimple (Liu et al., 2022a).

Where

The variable flap configuration with γ = 60°, w = 0.03c, and chordwise position (L) 0.7c demonstrated a 28% increase in maximum power yield, reducing dynamic stall and vortex shedding at the wake by 43%. A parametric study by (Xiao et al., 2013) revealed that the slot angle (γ) significantly influenced flow separation, delaying dynamic stall at high TSR and widening the operational range. Torque performance increased notably between 100° < θ < 240° at γ = 60°, with a fixed flap angle improving torque at 180°. Oscillation amplitude (

The discussed variable flap designs show promise for VAWT applications, but their implementation was relatively new and lacked real-world testing. Recommendations included exploring double-flap configurations with individual control and addressing challenges in control systems and sensor integration. Passive-control designs needed attention to spring stiffness and damping. Designs by (Xiao et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2021) can mitigate flow separation but fell short of typical VAWT performance. Advancements in control systems and physics, building upon Eqs 13–15, were needed for industry application readiness. Long-term benefits were yet to be confirmed.

3.3 Gurney flap control

A gurney flap (GF) is a short flap added at the end of the TE of an aerofoil, to be position on either the pressure side (Giguere et al., 1995; Myose et al., 1996; Li et al., 2002; Lee, 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Motta et al., 2016; Bianchini et al., 2019) or the suction side (Bianchini et al., 2019; Ni et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). There are also configurations with double GFs on both sides (Zhu et al., 2018b; Bianchini et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019). Early studies focus on GFs apply directly to the aerofoil (Giguere et al., 1995; Myose et al., 1996; Li et al., 2002; Lee, 2009; Zhang et al., 2009) with applications in racing vehicles demonstrating performance improvement (Liebeck, 1978). The GF is typically oriented perpendicular to the chordline, although some instances feature angled GFs (Shukla and Kaviti, 2017; Masdari et al., 2020). Liebeck (Liebeck, 1978) conducted the first study on GFs, revealing significant lift improvement with a slight increase in drag when the flap length. Fixed GFs have been applied to VAWTs for performance enhancement (Chen et al., 2020; Masdari et al., 2020; Chakroun and Bangga, 2021; Li et al., 2021; Ni et al., 2021; Syawitri et al., 2022). On the pressure side, GFs slow down flows, increasing pressure and creating a separation eddy before the flap leading edge, leading to higher pressure difference at the TE and increased lift force (Liebeck, 1978; Ismail and Vijayaraghavan, 2015). In some instances, a combination of a variable gurney flap and a TE adaptive flap design was used to enhance the aerodynamic performance of a rotary aircraft and serve as a load control (Figure 7B) (Motta et al., 2016).

Hybrid designs combining GFs and dimples have shown the best performance improvement for VAWTs. Studies preferred NACA 0012 and 0015 profiles, finding that NACA 0018 and 0021 fell short in achieving maximum lift. In a study (Zhu et al., 2019), GF-dimples on the suction side (outboard) of the blade at λ = 3.1 increased maximum

In Figure 7C, a variable c-dimple-GF significantly enhanced power production by up to 37.5% (Liu et al., 2022a). The actuated c-GF demonstrated higher performance and effective flow separation mitigation, particularly at θ = 60° during high TSRs. Early activation of the flap can hinder self-starting capabilities and CP production, though the starting azimuthal angle has minor influence. The trade-off with this variable system was the persistence of vortex shedding like with a fixed GF, as boundary layer separation is delayed. Liu et al. (Liu et al., 2022a), proposed an actuation motor to move the GF, requiring sensors for activation, but the associated costs and weight impact on the total turbine have not been investigated. Comparatively, a fixed GF with a dimple cavity cut-out was simpler and more cost-effective (Zhu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021), and a direct comparison between the two methods was yet to be conducted.

Liu et al. (2022a) proposed implementing a variable gurney flap using a retractable flap with an actuator, similar to those on aircraft wings. The actuator needed to be small enough to fit within the aerofoil, and for low wind speed conditions, a passive control with a contracting spring can be considered. However, the impact on overall power generation and the need for rapid movement in low TSR turbines should be carefully evaluated. It's essential to note that only simulated results had been presented, and further experiments to be recommended to validate these findings.

3.4 Deforming aerofoil

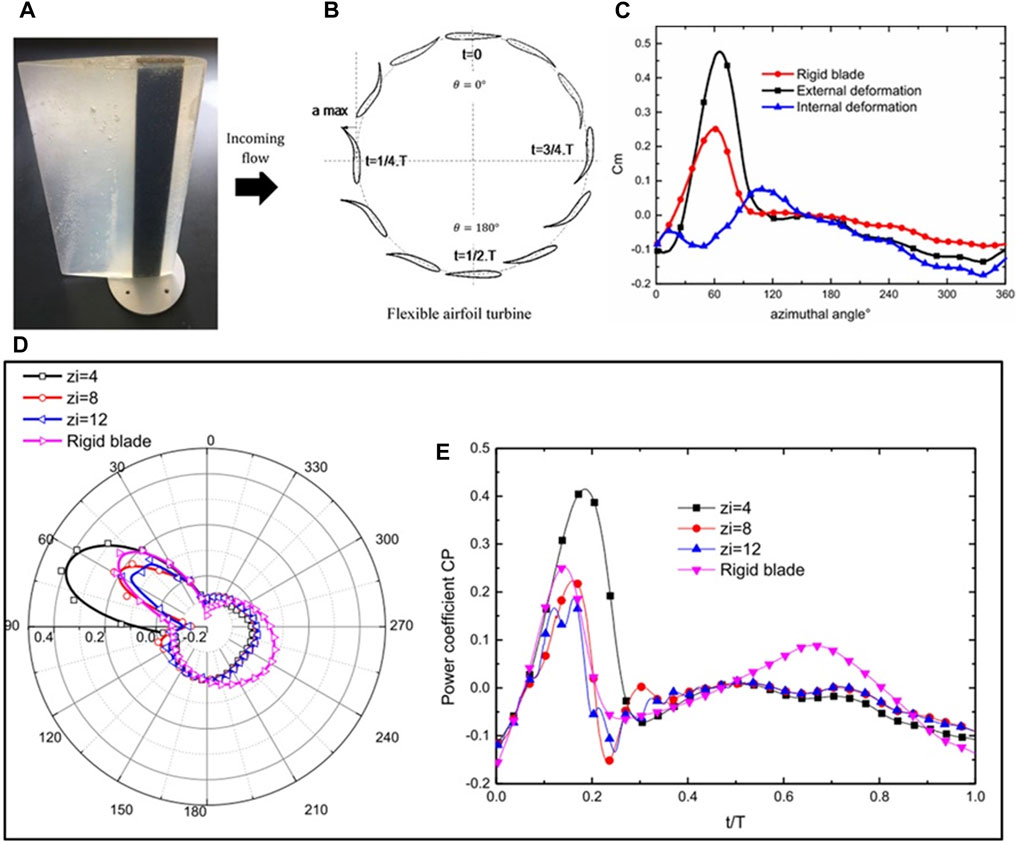

Morphing blades made from flexible materials, such as rubber (Tavallaeinejad et al., 2022), silicon (Lachenal et al., 2013; Pohl and Riemenschneider, 2022), offers a passive alternative to complex variable pitch controls (Zhu, 2007; MacPhee D. and Beyene A., 2016). These blades respond to changing aerodynamic forces by flexing or deforming, improving lift and delaying boundary layer separation (Lachenal et al., 2013; Wolff et al., 2014a). The technology, demonstrated in simplified models and studies on single aerofoils, has shown promising applications in HAWTs (Hoogedoorn et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012; MacPhee and Beyene, 2013; Capuzzi et al., 2014; Mo et al., 2015; Dai et al., 2017; Pavese et al., 2017; MacPhee and Beyene, 2019; Cavens et al., 2020). It can be controlled through active (Daynes and Weaver, 2012a; Daynes and Weaver, 2012b; Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2019; Leonczuk Minetto and Paraschivoiu, 2020; Pohl and Riemenschneider, 2022; Tong et al., 2023) or passive (Castelli et al., 2013; MacPhee and Beyene, 2013; Liu and Xiao, 2015; MacPhee DW. and Beyene A., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; MacPhee and Beyene, 2019; Cavens et al., 2020; Roy et al., 2021) methods by actuators and flexible materials.

A simplified model of a deformable TE using a foil was studied experimentally and numerically, showing enhanced thrust generation (Zhu, 2007). The flat plate formed a curvature, resembling cambering effects. Excessive flexibility negatively impacted turbine performance, but with the right amount of feathering, flow separation was effectively managed (Zhu, 2007; Liu and Xiao, 2015). However, the turbine’s performance was limited due to chaotic flow characteristics downstream caused by flexing and twisting along the blade span (Liu and Xiao, 2015; Bouzaher et al., 2016). At optimal settings, CP increased by 8% (Liu and Xiao, 2015).

Macphee and Beyene (MacPhee D. and Beyene A., 2016; MacPhee DW. and Beyene A., 2016) improved H-Darrieus turbine performance by 10% and reduced blade oscillation loads by 8.3% in a simulated study with a passively morphing VAWT. Notable enhancements occurred at azimuthal positions of 10°, 130°, and 250°, attributed to decreased vortex shedding and dynamic stalling. The morphing design also exhibited self-starting capabilities. The maximum CP increase of 9.6% was achieved with a Young’s Modulus of 0.5 MPa, while raising the modulus led to decreased performance. However, when Young’s Modulus (E) was raised turbine’s performance started decreasing. This aligns with the observation in (Wolff et al., 2014a) suggested that the flexibility of the blade was correlated to the blade’s dimensions as mentioned in (MacPhee DW. and Beyene A., 2016) emphasizing the correlation between blade flexibility and dimensions [146]. The passive pitch control system, governed by Eq. 18, showed the blade pitch angle (

Where,

Figure 8. Describes the experimental results of a single morphing blade for VAWT application using a (A) silicon rubber morphing blade (Roy et al., 2021). (B) Flexible blade motion at different azimuthal angles (Bouzaher et al., 2016). (C) Cambering effects of flexible blade compared to a rigid one (Bouzaher and Hadid, 2017). (D) Coefficient of moment and (E) power plotted against the blade’s azimuthal angle of a cycle (Bouzaher and Hadid, 2017).

Bouzaher et al. (Bouzaher et al., 2016; Bouzaher and Hadid, 2017) investigated the effects of flexions at the LE and TE of an aerofoil for VAWT and VATT applications, employing active control of flexible pitch. The study considered coefficients of moment, power, lift, and drag with varying oscillating frequency (

From the parametric studies (Bouzaher et al., 2016; Bouzaher and Hadid, 2017), proposed an implementation of

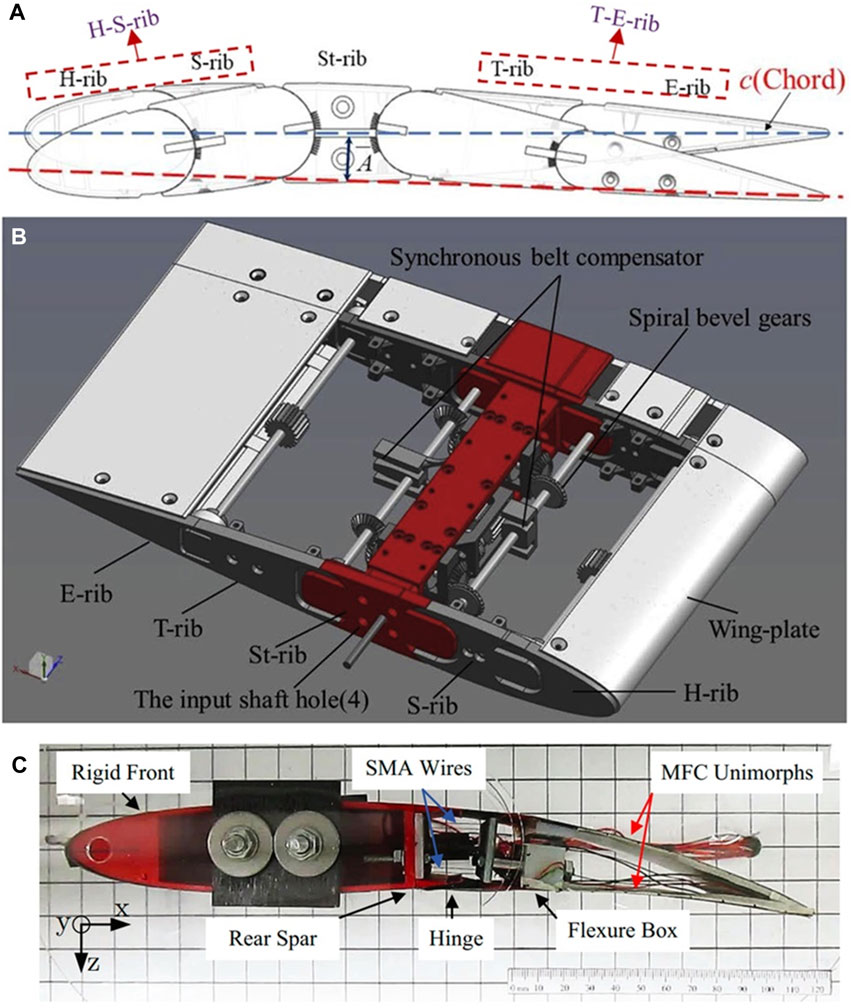

Wang et al. (2019) enhanced blade

Figure 9. Mechanical design of the synergistic smart morphing aerofoil (A) Schematic diagram of blade variation (Wang et al., 2019; Tong and Wang, 2021). (B) mechanism of active control morphing blade (Wang et al., 2019). (C) Mechanism of synergistic smart morphing aerofoil (Pankonien et al., 2014a).

Active morphing VAWTs, exemplified in (Bouzaher and Hadid, 2017), achieved a 35% power gain through LEV amplification (Bouzaher et al., 2016; Bouzaher and Hadid, 2017). Application examples of adaptable aerofoil morphing methods can be found in HAWT (Daynes and Weaver, 2012a; Daynes and Weaver, 2012b; Tripp et al., 2018; Cavens et al., 2020; Pohl and Riemenschneider, 2022), aerospace (Bornengo et al., 2005; Fichera et al., 2019) and motorsports (Bornengo et al., 2005). Material properties significantly influenced flapping motion, with the starting positions on the aerofoil having minimal impact (Bouzaher et al., 2016; Bouzaher and Hadid, 2017). Active morphing VAWT designs discussed in (Pankonien et al., 2014a; Wang et al., 2019) may not be suitable for small to medium-sized or low-wind VAWTs, potentially negating morphing aerofoil advantages (Wolff et al., 2014a; Wolff and Seume, 2016). Incorporated morphing systems at specific span sections, seen in (Wang et al., 2012) or adopting configurations suitable for large morphing VAWTs, as suggested by Baghdadi et al., 2020 could offer alternative solutions. Hoke et al., 2015 achieved a 37.3% thrust improvement by combining sinusoidal VP motion with a deforming aerofoil, broke down and delayed LEV formation to enhance suction forces on the blade.

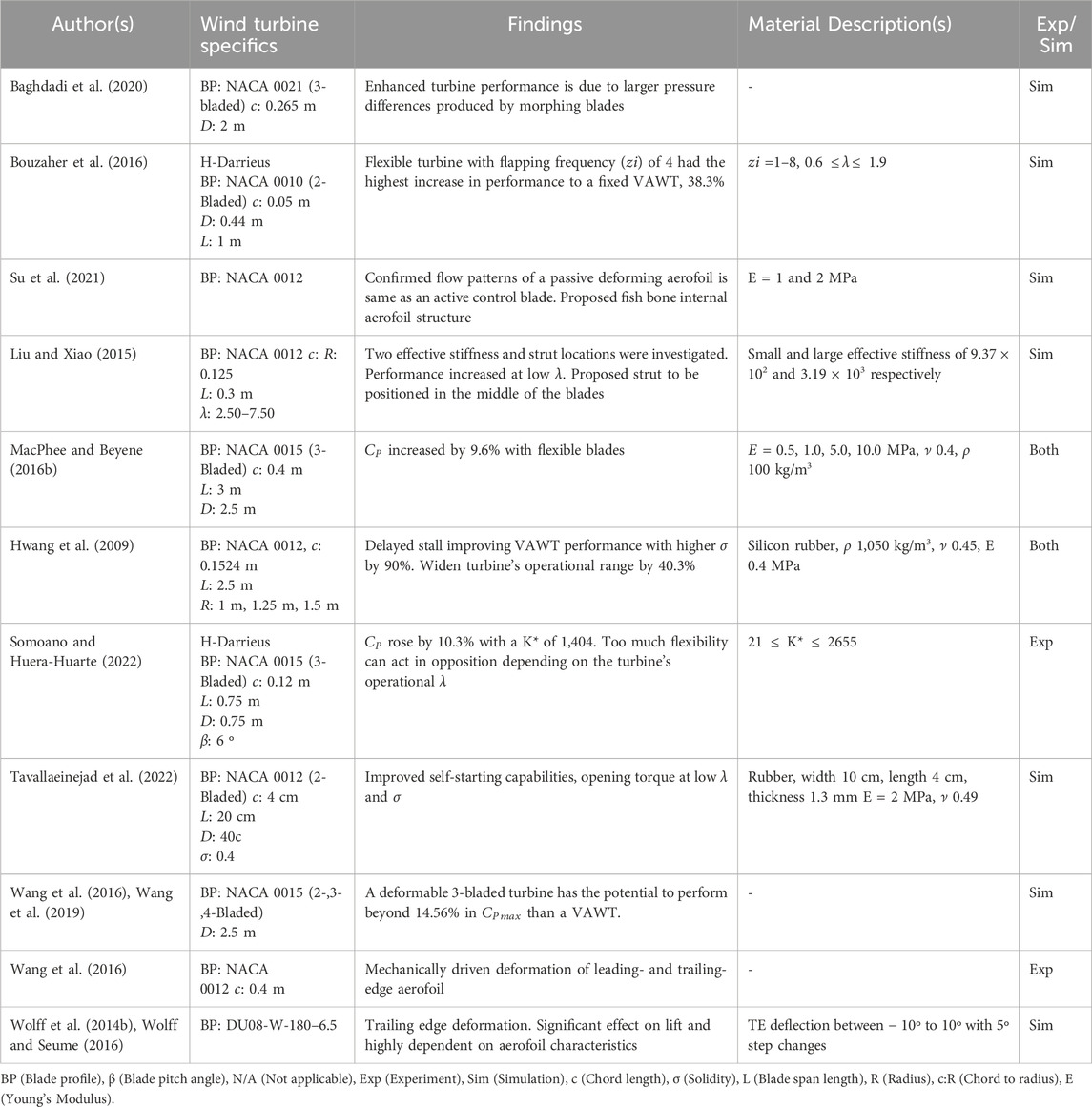

In conclusion, actively morphing aerofoils is more suitable for large VAWTs and HAWTs. Integrated morphing flat plates in VAWT designs also show potential applications (Tian et al., 2014; Tavallaeinejad et al., 2022). However, potential downsides include wear and tear on joints and the complexity of actuation mechanisms. Both actively and passively morphing blades require flexible materials with periodic loading. Joining flexible and solid materials can be complex, requiring special adhesives and potentially impacting VAWT sustainability. The recyclability of flexible materials is crucial for environmental friendliness. Ultraviolet (UV) rays and heat from the sun can reduce the life expectancy of flexible materials by exciting the surface molecules, leading to the breaking of chemical bonds and the deterioration of the material’s properties (Awaja et al., 2011; Nasri et al., 2022). Despite these challenges, there are opportunities for this design to enhance VAWT performance. Exploring the internal structure for passive morphing VAWT and investigating other flow energy harvesters with morphing capabilities are potential avenues for improvement. Table 2 provides a summary of deforming aerofoils.

3.5 Movable mass blocks

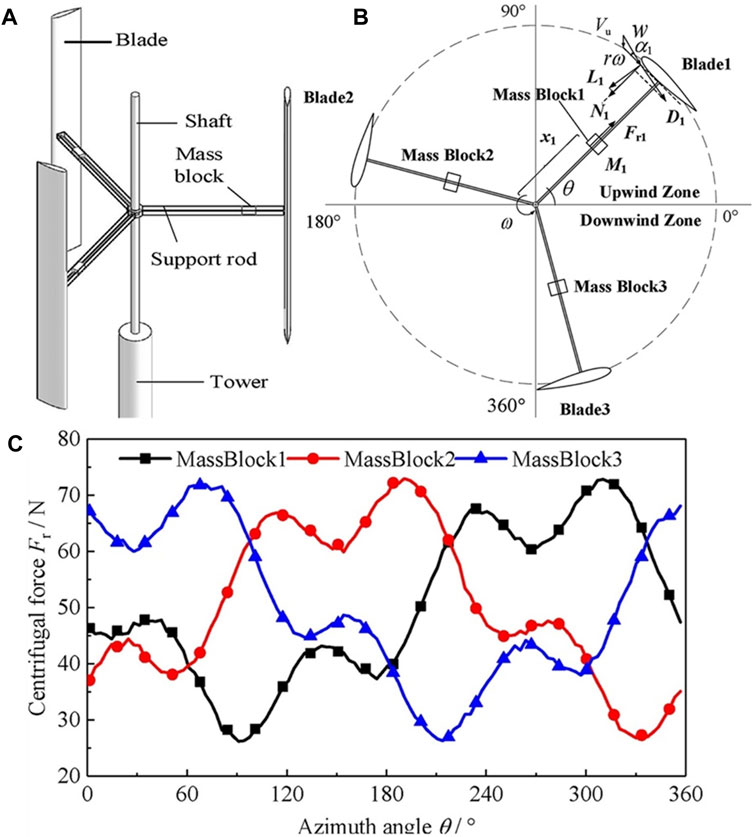

A passively variable movable mass block for VAWT was suggested by Zhang et al. (Zhang LJ. et al., 2021) to reduce shaft radial loadings and enhance the shaft’s lifespan. The design relies on centrifugal forces of mass blocks to counteract radial loads on the rotating shaft, with a mass block placed on each strut. Independent movement of the mass blocks along the arm is facilitated by a support rod (Figure 10A). Eq. 19 allows the prediction of the required mass and traveling displacement of the mass blocks at specific azimuthal angles.

where

Figure 10. Shows the movable mass block (A) design mechanism, (B) kinematic diagram of the movable mass blocks system and (C) centrifugal forces of MassBlocks across different azimuthal angles (Zhang LJ. et al., 2021).

CFD simulations indicated a 52.4% reduction in radial loading, leading to a 51% decrease in total shaft deformation. Increasing mass block weight to 0.075 kg resulted in only 1% shaft damage, with radial loading dropping by 97.1%. The optimal mass for each block was determined to be 0.065 kg (Zhang LJ. et al., 2021).

Since introducing mass blocks, the turbine’s performance remains uncompromised. However, an unforeseen issue arises with the turbine’s self-starting capabilities and start-up wind velocity significantly impacted due to added weight, necessitating a larger moment of inertia for rotation. Consequently, the turbine experiences an extended start-up duration. Zhang et al. (Zhang LJ. et al., 2021) propose a solution by calibrating mass block displacement along the arms base on a displacement increment equation to increase the moment of inertia from 0.018 kgm2 to 0.036 kgm2, this shorten the start-up duration by 40.6%.

While this variable method shows promise in reducing radial loadings and extending the turbine shaft’s lifespan, concerns arise about the durability of the struts. Higher loads may lead to bending over time, particularly affecting the struts along the track where the mass blocks oscillate (Zhang LJ. et al., 2021). Wear and tear on the struts could become a future issue as materials degrade, impacting bending deformation at the arms.

Notably, medium to large-scale H-Darrieus turbines typically have two supporting arms to the blade, unlike the single arm used in this study. Further studies can explore the robustness of the equations. Additionally, the control method for the wind turbine is yet to be explored, and its impacts on the shaft parameters in a final design should be carefully considered.

3.6 Synthetic jet

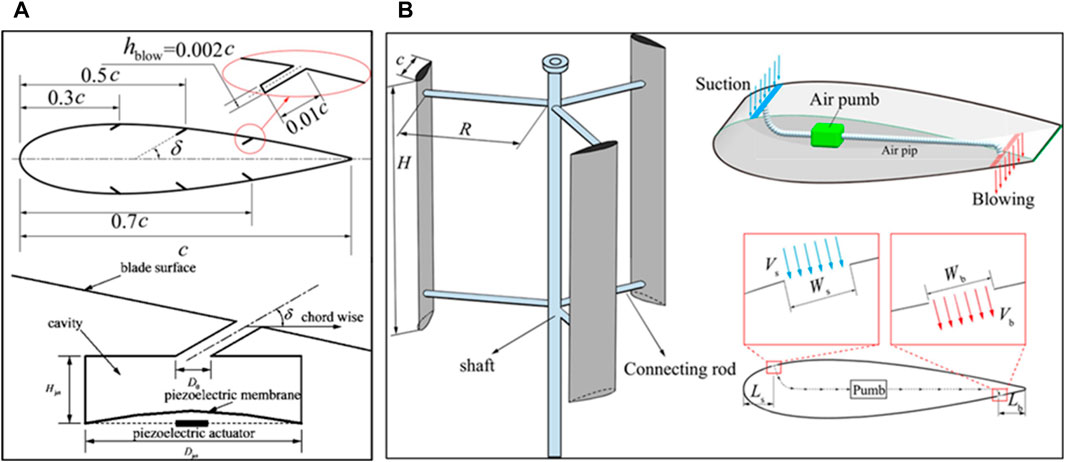

Rezaeiha et al. (Rezaeiha et al., 2019) proposed an active control suction slot to be placed at the LE of the aerofoil in chordwise to enhance aerodynamic performance by delaying the flow separation with smaller laminar separation bubble (LSB). It prevented turbulent flow and boundary layer detachment. An increased in CL and a minimization of the CD were observed on the blade. Thus, delaying dynamic stalls forming at higher AoAs. At 50

Optimal settings increased CP by 247% at a TSR of 2.5 with suction slots at 8.5% of the chord length. TSR, turbulence intensity, and Reynold’s number were influential in governing slot positions. Moving slots further down chordwise to 13.5%, 18.5%, and 28.5% resulted in decreasing power yield by 208%, 119%, and 81%, respectively. Slots moving nearer to the trailing edge (TE) shifted the suction effect away from the leading edge, leading to a greater development of dynamic stall (Rezaeiha et al., 2019).

Sun and Huang (Sun and Huang, 2021) confirmed similar findings and extended their study to multi-suction slots on NACA-021 series aerofoils for an H-Darrieus turbine. Tested different maximum thickness positions relative to a single suction slot and observed that as the maximum thickness of the aerofoil moved towards the TE, the optimum positions for the suction slots also moved down away from the LE. Similar findings in (Yen and Ahmed, 2013), indicating that synthetic jet actuation had little influence on pressure distribution, particularly in the early stages of suction development along the LE when flow separation had not occurred. Using lift and drag ratios as measured outputs (Sun and Huang, 2021), proposed a double suction slot along the chord at positions of 10% and 30% for low TSR turbines and, for high TSR turbines, positions at 30% and 50% of the aerofoil chordwise.

An earlier research report published by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) concluded positively on the addition of a backward-opening slot to blow air from a single static aerofoil, showing improved maximum lift, reduced drag forces, and better control on stall effects (Knight and Bamber, 1929). Liu et al. (2022b) applied similar boundary layer control techniques and introduced a blow-suction synergy (BSS) method to address dynamic stall issues at lower TSRs. The study focused on optimizing the LE suction slots and jet coefficient (Cμ), determining optimal settings through an orthogonal experimental design method (

The BSS also enhanced turbine stability, decreased negative tangential forces and provided smaller vortex shedding with higher wake dissipation at the TE in upstream regions (Figure 11B). The proposed control strategy involved intermittent blowing and suction, with suction at the inner side and blowing at the outer side between 0° and 180° azimuthal angles, and the opposite configuration (suction at the outer side and blowing at the inner side) from 180° to 360° azimuthal range. Although no working models or experiments had been conducted, the suggested includes placing air pumps in the blades with valves at the slots to control fluid flow, emphasizing intermittent control for reduced power consumption (Liu et al., 2022b).

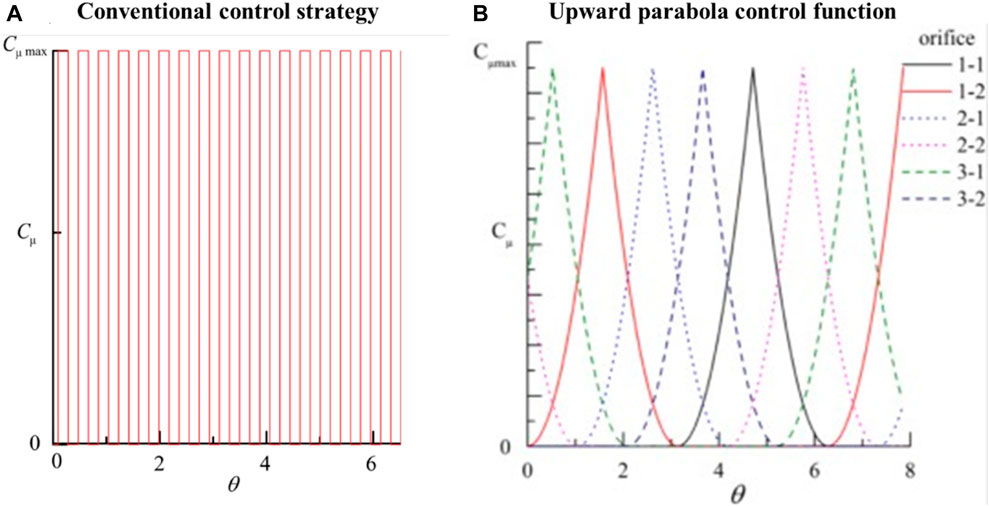

Figure 11. Comparison between (A) conventional to (B) upward parabola control functions (Zhu et al., 2018a).

Zhu et al. (Zhu et al., 2018a), explored suction slot numbers, jet momentum coefficients, and control strategies (Figure 12A). Optimal power yield improvement was found with two suction orifices at the TE. Contrary to the previous studies (Rezaeiha et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2022b). This study demonstrated that double trailing-edge slots, upward-parabola control strategy, and a jet coefficient of 0.035 achieved a 15.2% increase in power coefficient (Figure 11). The relationship between orifice slots and CP was suggested to be inversely proportional. Conventional methods (Figure 11A) faced issues with uneven loading fluctuations, but alternative controls, particularly the upward parabola (Figure 11B), proved efficient with an 80.10% reduction in actuator energy consumption. Synthetic jet flow control delayed flow separation and dynamic stalls, improving pressure distribution, lowering blade-wake interactions, and reducing trailing edge vortices. The paper proposed a piezoelectric synthetic jet actuator (Figure 12B) (Liu et al., 2022b).

Figure 12. Two different types of synthetic jet mechanism. (A) Design parameters of aerofoil for multi-slot study and sketch of synthetic jet actuator (Zhu et al., 2018a). (B) Blow-suction synergy method (BSS) (Liu et al., 2022b).

Concerns also arise about the total weight of the turbine, especially the blades. For instance, in (Liu et al., 2022b), enclosing pumps within the blade could substantially increase the overall blade mass. As discussed earlier in variable methods, mass is critical, impacting self-starting capabilities and reducing initial advantages. Furthermore, more blade energy is necessary for the turbine’s self-starting. The cost implications from design to fabrication of such a turbine must be thoroughly evaluated.

3.7 Variable swept area

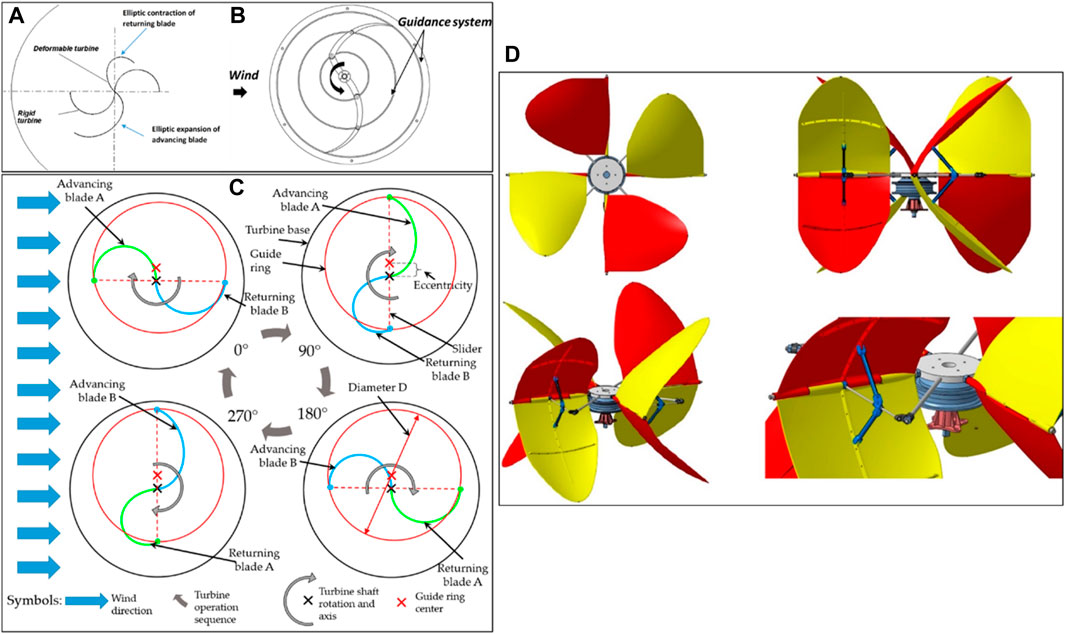

The expandable Savonius, akin to morphing aerofoil VAWTs, uses rotating concave plates to alter its sweep area (Bouzaher, 2022; Bouzaher and Guerira, 2022). In 2D CFD studies by Bouzaher et al. (Bouzaher, 2022; Bouzaher and Guerira, 2022), torque increase by 90.6% at maximum expansion. Figures 13A,B illustrates the design with three segments per concaved blade, connected by hinges, moving elliptically. As the advancing blade expands, the concave curvature increases, accelerating fluid flow and improving self-starting capabilities. With a constant 1 m diameter, improvements range from 6% to 112% across deformation amplitudes (Bouzaher, 2022).

Figure 13. The different variable swept area that are currently being studied on. (A) Elliptical motion (Bouzaher and Guerira, 2022) (B) Mechanical design of expandable Savonius design (Bouzaher and Guerira, 2022). and (C) the principles of a deformable Savonius turbine (Sobczak et al., 2020) and (D) Variable swept area VAWT (Pietrykowski et al., 2023).

Marinić-Kragić et al. (Marinić-Kragić et al., 2019) achieved a 26% improvement (CP = 0.28) with a flexible system at TSR = 0.9. In contrast to prior systems (Bouzaher, 2022; Bouzaher and Guerira, 2022), this study used an elastic material, allowing vanes to deform and create expansion and contraction. Plastic reinforced with glass fibers was employed for flexibility, possessing mechanical properties of E = 30 GPa, ν = 0.28, and ρ = 1,600 kg/m³. Vortex magnitudes remained constant, but CP increased due to a widened pressure difference at θ = 90°, where maximum deformation and power generation occurred. The material’s mechanical properties were the main limiting factor, and a rotational speed modulator was proposed to maintain safe operational conditions beyond the material’s stress capacity.

Another similar concept of deformable variable Savonius investigated by (Sobczak et al., 2020; Marchewka et al., 2021), enhancing turbine power performance by 90% compared to a fixed Savonius (Figure 13C). CFD results indicated maximum deformation between θ of 45° and 180°, with the highest CP recorded at θ = 105° and an eccentricity of 15%. A maximum

For Darrieus VAWT, improvements were observed at low TSR conditions (Fadil et al., 2020; Abdolahifar et al., 2023; Pietrykowski et al., 2023; Abdolahifar et al., 2023) found a drop in performance at low and high TSRs (0.69≤ λ ≤ 1.5) with a V-shaped blade turbine, attributing it to violent non-uniform vortex separation due to the aerofoil shape. Helical and H-VAWTs exhibited 42% and 54.4% higher torque, respectively, than the V-shaped blade with twist. However, Pietrykowski et al. (Pietrykowski et al., 2023) reported improved power generation with a variable swept area design (Figure 13D), showed an optimum CP = 0.08 at low TSR (0.3–0.4). The swept area increased at lower wind speeds (0.785 m2) and decreased at higher speeds (0.285 m2) with θ at 120° and 30°, respectively. Operational TSR ranged from 0.1 to 0.6.

Manufacturing complexities are the main downside. If costs are reasonable and materials durable, there is a potential for commercialisation. Further studies on control can expedite implementations. In comparison, the reviewed expandable Savonius design is currently more suitable for low wind conditions.

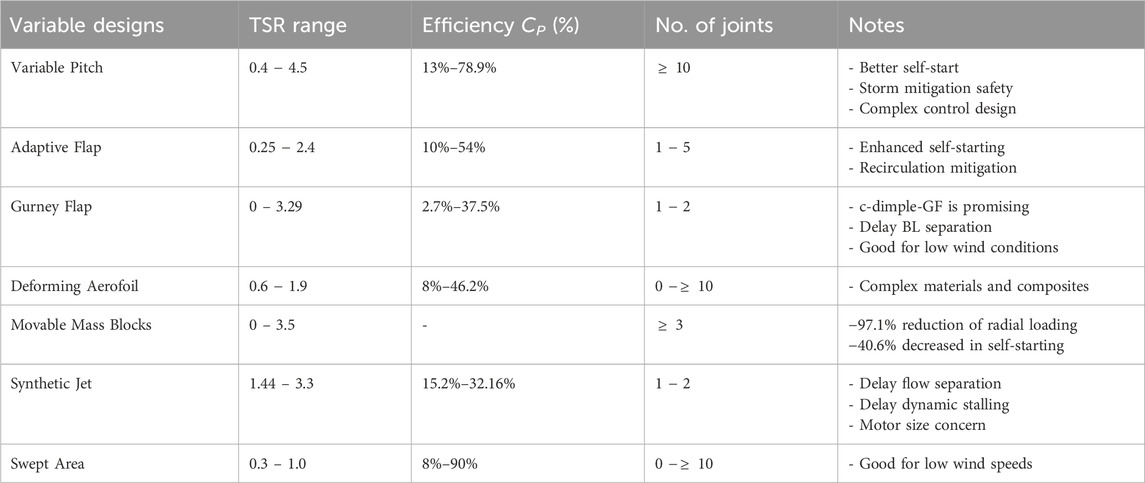

4 Analysis of variable designs

The review summarizes various designs in Table 3, comparing them based on CP increase. The complexity is defined by the number of moving parts provided at the readers’ convenience. However, to gauge the true productivity potential of these variable methods, a cost-benefit analysis will be conducted from production to end-of-life. Realistic manufacturing processes are excluded due to the absence of attainable data on market preferences. Nevertheless, this analysis provides engineers with a sufficient holistic overview and understanding of the developmental stages of these variable designs.

5 Future perspective

The review underscores performance improvements in VAWTs through variable designs, but commercialization awaits additional evidence. Future research directions in variable methods for VAWTs are outlined in the conclusion.

• Numerical studies lack practical implementation details, omitting factors like mechanical losses and real-world challenges. Future research, involving wind tunnel experiments and real-world implementation, is necessary to address the limitations of variable VAWTs comprehensively.

• Variable mechanism complexity will be highly influential for a variable method to realise commercialisation characterising the ease of implementation, manufacturing, maintenance and cost effectiveness. It will be crucial for low wind turbines.

• Deforming aerofoil is a potential viable method as it requires no added mechanical control system for passive control designs. However, material exploration should be conducted to determine the right material strengths and properties to be use for VAWT. UV damage and material recyclability should be included in designing process.

• As for other variable methods too, should investigate alternative materials that can be lighter, higher stress tolerances and sustainable to be replaced.

• VP-VAWTs can be an effective method for turbine storm protection. More studies can be done to investigate the efficiency passive aerodynamic braking with this method. Integration of this variable method can be investigated for large VAWTs.

• Although, variable solidity by (Huang et al., 2023; Tong et al., 2023) found to have good potential due to its simplicity and had proven, but more evidence is required to deeper understand this variable method.

• Combination of variable methods can be investigated. A passively deformable aerofoil coupled with a variable solidity can be seen as a good combination to optimise flow of the turbine whilst extracting the most energy from low to high wind speeds.

• Investigations to merry flow augmentation methods like (Wong et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2018a; Wong et al., 2018b; Wang et al., 2022) with variable designs to enhance power generation especially at low wind speed regions.

• Field testing and validation will give engineers a deeper understanding to the actual performance values when turbines are subjected to varying wind speeds and weather conditions. Many unforeseen weaknesses can be rooted out during this process that may influence final costings and sustainability.

• The use of artificial intelligence can be implemented to shorten the duration of studies in improving and optimising the variable design factors like pitch control (Abdalrahman et al., 2017), design of a Savonius VAWT (Teksin et al., 2022) and pattern trends of blade designs on VAWT (Noman et al., 2022).

6 Conclusion

The increasing demand for VAWTs in the wind energy market suggests significant potential for variable designs to enhance turbine performance and reduce aerodynamic losses by minimising stall effects and size of vortex eddies. The following outlines conclusions drawn from a review of methodologies in prior state-of-the-art studies.

(1) VP-turbines hold strong commercialization potential due to progressing from numerical studies to mechanical designs. It demonstrates self-starting capabilities, significant aerodynamic improvements, and increased power generation. There’s potential for use as a storm protection system, preventing the turbine from operating beyond its capabilities. However, a downside is the potential for drastic and intrusive pitch changes during intervals, which may damage the turbine. Performance improved between 20% and 50%. Active and passive control shown great advantages with minimal differences. As for passive controls, sinusoidal control method had shown to outperform other systems.

(2) Adaptive flaps break down trailing edge vortices, reducing wake disturbances and improving power yield in the downwind section. While common in aviation, this approach is relatively new in VAWT technology. Active control may be more effective for this variable method, with multiple flaps towards the blade’s trailing edge proving more effective than a single flap. Flap angle operational range should be between 20

(3) GF control enhances pressure distribution at the trailing edge by slowing incoming flow velocity, creating separation bubbles that reattach the flow. Additional modifications, such as inward dimples, can be combined with GFs. A small sensor initiates the motor and varies the GF, making a smaller flap a cost-effective method due to the reduced force needed to change the GF’s angle. GF-dimple places at the outboard improved more by 5.8% than inboard dimples. Early initiation of GF-dimples will inhibit self-starting capabilities.

(4) A deformable aerofoil offers promising passive control for small, low wind speed turbines. The use of elastic material reduces moving parts, increasing aerodynamic stall mitigation in investigations. The properties of the elastic material play a crucial role in the turbine’s performance, flexibility, weight, durability, and potential costs. Performance improvement was seen to be ranged between 9.6% and 90% with E = 0.5 MPa and 0.4 MPa. Active control deformation also seen an increase by 35% however, the significance from complexity of mechanism to power the control system and maintenance have not been explored.

(5) Moveable mass blocks, controlled by centrifugal forces, reduce shaft fatigue to only 1% damage, extending the turbine’s operational life, without aerodynamic improvements. The mass of the blocks used were 0.065 g on each of the turbine strut.

(6) The synthetic jet, with suction and blowing slots, prevents flow separation, delays dynamic stall, and enhances turbine performance. LE edge slots positioned around 8.5% of the chord had proven to have positive impact. TE slots had an opposite effect reducing performance up to 208% recorded. Control system development is ongoing.

(7) Expandable Savonius turbines, using elastic materials and segmented vanes for adjustable operation, hold promise for boosting power generation in low wind speed conditions. The working mechanics resemble those of a deformable aerofoil.

Author contributions

K-YL: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–original draft. AC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. J-HN: Supervision, Writing–review and editing. K-HW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia through the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS), grant number FRGS/1/2020/TK0/USMC/02/3.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdalkarem, A. A. M., Abdullah, A. F., Sopian, K., Haw, L. C., Muzammil, W. K., and Wong, K. H. (2023). The effect of trailing-edge wedge-tails on the aerodynamic characteristics of wind turbine airfoil. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1278 (1), 012011. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/1278/1/012011

Abdalrahman, G., Melek, W., and Lien, F.-S. (2017). Pitch angle control for a small-scale Darrieus vertical axis wind turbine with straight blades (H-Type VAWT). Renew. Energy 114, 1353–1362. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2017.07.068

Abdolahifar, A., Azizi, M., and Zanj, A. (2023). Flow structure and performance analysis of Darrieus vertical axis turbines with swept blades: a critical case study on V-shaped blades. Ocean. Eng. 280, 114857. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.114857

Aboelezz, A., Ghali, H., Elbayomi, G., and Madboli, M. (2022). A novel VAWT passive flow control numerical and experimental investigations: guided Vane Airfoil Wind Turbine. Ocean. Eng. 257, 111704. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.111704

Aslam Bhutta, M. M., Hayat, N., Farooq, A. U., Ali, Z., Jamil, S. R., and Hussain, Z. (2012). Vertical axis wind turbine – a review of various configurations and design techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16 (4), 1926–1939. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2011.12.004

Awaja, F., Nguyen, M.-T., Zhang, S., and Arhatari, B. (2011). The investigation of inner structural damage of UV and heat degraded polymer composites using X-ray micro CT. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 42 (4), 408–418. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2010.12.015

Azadani, L. N., and Saleh, M. (2022). Effect of blade aspect ratio on the performance of a pair of vertical axis wind turbines. Ocean. Eng. 265, 112627. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.112627

Baghdadi, M., Elkoush, S., Akle, B., and Elkhoury, M. (2020). Dynamic shape optimization of a vertical axis wind turbine via blade morphing technique. Renew. Energy 154, 239–251. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.03.015

Battisti, L. (2021). Design options to improve the dynamic behavior and the control of small H-Darrieus VAWTs. Appl. Sci. 11 (19), 9222. doi:10.3390/app11199222

Bechert, D., Bruse, M., Hage, W., Meyer, R., Bechert, D., Bruse, M., et al. (1997). “Biological surfaces and their technological application - laboratory and flight experiments on drag reduction and separation control,” in 28th Fluid Dynamics Conference (AIAA).

Belabes, B., and Paraschivoiu, M. (2021). Numerical study of the effect of turbulence intensity on VAWT performance. Energy 233, 121139. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.121139

Benedict, M., Lakshminarayan, V., Pino, J., and Chopra, I. (2013). “Fundamental understanding of the physics of a small-scale vertical Axis wind turbine with dynamic blade pitching: an experimental and computational approach,” in 54th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference (AIAA).

Bianchini, A., Balduzzi, F., Di Rosa, D., and Ferrara, G. (2019). On the use of Gurney Flaps for the aerodynamic performance augmentation of Darrieus wind turbines. Energy Convers. Manag. 184, 402–415. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2019.01.068

Bianchini, A., Balduzzi, F., Ferrara, G., and Ferrari, L. (2016). Virtual incidence effect on rotating airfoils in Darrieus wind turbines. Energy Convers. Manag. 111, 329–338. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2015.12.056

Bianchini, A., Ferrara, G., and Ferrari, L. (2015). Pitch optimization in small-size Darrieus wind turbines. Energy Procedia 81, 122–132. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2015.12.067

Bontempo, R., Carandente, R., and Manna, M. (2021). A design of experiment approach as applied to the analysis of diffuser-augmented wind turbines. Energy Convers. Manag. 235, 113924. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2021.113924

Bornengo, D., Scarpa, F., and Remillat, C. (2005). Evaluation of hexagonal chiral structure for morphing airfoil concept. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 219 (3), 185–192. doi:10.1243/095441005x30216

Bouzaher, M. T. (2022). Effect of flexible blades on the Savonius wind turbine performance. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 44 (2), 60. doi:10.1007/s40430-022-03374-5

Bouzaher, M. T., and Guerira, B. (2022). Computational investigation on the influence of expandable blades on the performance of a Savonius wind turbine. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 144 (6). doi:10.1115/1.4054395

Bouzaher, M. T., and Hadid, M. (2017). Numerical investigation of a vertical Axis tidal turbine with deforming blades. Arabian J. Sci. Eng. 42 (5), 2167–2178. doi:10.1007/s13369-017-2511-5

Bouzaher, M. T., Hadid, M., and Semch-Eddine, D. (2016). Flow control for the vertical axis wind turbine by means of flapping flexible foils. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 39 (2), 457–470. doi:10.1007/s40430-016-0618-3

Bramesfeld, G., and Maughmer, M. D. (2002). Experimental investigation of self-actuating, upper-surface, high-lift-enhancing effectors. J. Aircr. 39 (1), 120–124. doi:10.2514/2.2905

Brusca, S., Lanzafame, R., and Messina, M. (2014). Design of a vertical axis wind turbine: how the aspect ratio affects the turbine’s performance. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 5 (4), 333–340. doi:10.1007/s40095-014-0129-x

Burton, T., Sharpe, D., Jenkins, N., and Bossanyi, E. (2001). Wind energy handbook. John Wiley and Sons.

Camporeale, S. M., and Magi, V. (2000). Streamtube model for analysis of vertical axis variable pitch turbine for marine currents energy conversion. Energy Convers. Manag. 41 (16), 1811–1827. doi:10.1016/s0196-8904(99)00183-1

Capuzzi, M., Pirrera, A., and Weaver, P. M. (2014). A novel adaptive blade concept for large-scale wind turbines. Part I: aeroelastic behaviour. Energy 73, 15–24. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2014.06.044

Carrigan, T. J., Dennis, B. H., Han, Z. X., and Wang, B. P. (2012). Aerodynamic shape optimization of a vertical Axis wind turbine using differential evolution. ISRN Renew. Energy 2012, 1–16. doi:10.5402/2012/528418

Castelli, M. R., Dal Monte, A., Quaresimin, M., and Benini, E. (2013). Numerical evaluation of aerodynamic and inertial contributions to Darrieus wind turbine blade deformation. Renew. Energy 51, 101–112. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2012.07.025

Cavens, W. D. K., Chopra, A., and Arrieta, A. F. (2020). Passive load alleviation on wind turbine blades from aeroelastically driven selectively compliant morphing. Wind Energy 24 (1), 24–38. doi:10.1002/we.2555

Chakroun, Y., and Bangga, G. (2021). Aerodynamic characteristics of airfoil and vertical Axis wind turbine employed with gurney flaps. Sustainability 13 (8), 4284. doi:10.3390/su13084284

Chao, L.-M., Pan, G., Zhang, D., and Yan, G.-X. (2019). Numerical investigations on the force generation and wake structures of a nonsinusoidal pitching foil. J. Fluids Struct. 85, 27–39. doi:10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2018.12.002

Chen, C.-C., and Kuo, C.-H. (2012). Effects of pitch angle and blade camber on flow characteristics and performance of small-size Darrieus VAWT. J. Vis. 16 (1), 65–74. doi:10.1007/s12650-012-0146-x

Chen, L., Xu, J., and Dai, R. (2020). Numerical prediction of switching gurney flap effects on straight bladed VAWT power performance. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 34 (12), 4933–4940. doi:10.1007/s12206-020-2106-z

D, A., and Singh, I. (2016). Self-adaptive flaps on low aspect ratio wings at low Reynolds numbers. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 59, 78–93. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2016.10.006

Dai, J., Hu, W., and Shen, X. (2017). Load and dynamic characteristic analysis of wind turbine flexible blades. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 31 (4), 1569–1580. doi:10.1007/s12206-017-0304-0

Danao, L. A., Qin, N., and Howell, R. (2012). A numerical study of blade thickness and camber effects on vertical axis wind turbines. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 226 (7), 867–881. doi:10.1177/0957650912454403

Daynes, S., and Weaver, P. M. (2012a). A morphing trailing edge device for a wind turbine. J. Intelligent Material Syst. Struct. 23 (6), 691–701. doi:10.1177/1045389x12438622

Daynes, S., and Weaver, P. M. (2012b). Design and testing of a deformable wind turbine blade control surface. Smart Mater. Struct. 21 (10), 105019. doi:10.1088/0964-1726/21/10/105019

De Tavernier, D., Ferreira, C., and Bussel, G. (2019). Airfoil optimisation for vertical-axis wind turbines with variable pitch. Wind Energy 22 (4), 547–562. doi:10.1002/we.2306

Elkhoury, M., Kiwata, T., and Aoun, E. (2015). Experimental and numerical investigation of a three-dimensional vertical axis wind turbine with variable-pitch. J. Wind Eng. Industrial Aerodynamics 139, 111–123. doi:10.1016/j.jweia.2015.01.004

Elsakka, M. M. (2020). The aerodynamics of fixed and variable pitch vertical Axis wind turbines. University of Sheiffield.

El-Samanoudy, M., Ghorab, A. A. E., and Youssef, S. Z. (2010). Effect of some design parameters on the performance of a Giromill vertical axis wind turbine. Ain Shams Eng. J. 1 (1), 85–95. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2010.09.012

Erickson, D., Wallace, J., and Peraire, J. (2012). Performance characterization of cyclic blade pitch variation on a vertical Axis wind turbine. AIAA J. 49, 23. doi:10.2514/6.2011-638

Esfahani, J. A., Barati, E., and Karbasian, H. R. (2015). Fluid structures of flapping airfoil with elliptical motion trajectory. Comput. Fluids 108, 142–155. doi:10.1016/j.compfluid.2014.12.002

Fadil, J., Soedibyo, S., and Ashari, M. (2020). Novel of vertical Axis wind turbine with variable swept area using fuzzy logic controller. Int. J. Intelligent Eng. Syst. 13 (3), 256–267. doi:10.22266/ijies2020.0630.24

Fichera, S., Isnardi, I., and Mottershead, J. E. (2019). High-bandwidth morphing actuator for aeroelastic model control. Aerospace 6 (2), 13. doi:10.3390/aerospace6020013

Fiedler, A. J., and Tullis, S. (2009). Blade offset and pitch effects on a high solidity vertical Axis wind turbine. Wind Eng. 33 (3), 237–246. doi:10.1260/030952409789140955

Giguere, P., Lemay, J., and Dumas, G. (1995). “Gurney flap effects and scaling for low-speed airfoils,” in 13th Applied Aerodynamics Conference (AIAA).

Guevara, P., Rochester, P., and Vijayaraghavan, K. (2021). Optimization of active blade pitching of a vertical axis wind turbine using analytical and CFD based metamodel. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 13 (2). doi:10.1063/5.0026591

Guo, Y., Li, X., Sun, L., Gao, Y., Gao, Z., and Chen, L. (2019). Aerodynamic analysis of a step adjustment method for blade pitch of a VAWT. J. Wind Eng. Industrial Aerodynamics 188, 90–101. doi:10.1016/j.jweia.2019.02.023

Hand, B., Kelly, G., and Cashman, A. (2021). Aerodynamic design and performance parameters of a lift-type vertical axis wind turbine: a comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 139, 110699. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110699

Hao, W., Ding, Q., and Li, C. (2019). Optimal performance of adaptive flap on flow separation control. Comput. Fluids 179, 437–448. doi:10.1016/j.compfluid.2018.11.010

Hao, W., and Li, C. (2020). Performance improvement of adaptive flap on flow separation control and its effect on VAWT. Energy 213, 118809. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.118809

Hao, W., Li, C., Ye, Z., Yang, J., and Ding, Q. (2017). Computational study on wind turbine airfoils based on active control for deformable flaps. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 31 (2), 565–575. doi:10.1007/s12206-017-0109-1

Hassan, S. M. R., Ali, M., and Islam, M. Q. (2016). “The effect of solidity on the performance of H-rotor Darrieus turbine,” in AIP Conference Proceedings (AIP Publishing).

Hoke, C. M., Young, J., and Lai, J. C. S. (2015). Effects of time-varying camber deformation on flapping foil propulsion and power extraction. J. Fluids Struct. 56, 152–176. doi:10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2015.05.001

Hoogedoorn, E., Jacobs, G. B., and Beyene, A. (2010). Aero-elastic behavior of a flexible blade for wind turbine application: a 2D computational study. Energy 35 (2), 778–785. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2009.08.030

Horb, S., Fuchs, R., Immas, A., Silvert, F., and Deglaire, P. (2018). Variable pitch control for vertical axis wind turbines. Wind Eng. 42 (2), 128–135. doi:10.1177/0309524x18756972

Huang, D., and Wu, G. (2013). Preliminary study on the aerodynamic characteristics of an adaptive reconfigurable airfoil. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 27 (1), 44–48. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2012.06.005

Huang, H., Luo, J., and Li, G. (2023). Study on the optimal design of vertical axis wind turbine with novel variable solidity type for self-starting capability and aerodynamic performance. Energy 271, 127031. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.127031

Hwang, I. S., Lee, Y. H., and Kim, S. J. (2009). Optimization of cycloidal water turbine and the performance improvement by individual blade control. Appl. Energy 86 (9), 1532–1540. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2008.11.009

Islam, M., Fartaj, A., and Carriveau, R. (2008a). Analysis of the design parameters related to a fixed-pitch straight-bladed vertical Axis wind turbine. WIND Eng. 32, 491–507. doi:10.1260/030952408786411903

Islam, M., Ting, D., and Fartaj, A. (2008b). Aerodynamic models for Darrieus-type straight-bladed vertical axis wind turbines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 12 (4), 1087–1109. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2006.10.023

Ismail, M. F., and Vijayaraghavan, K. (2015). The effects of aerofoil profile modification on a vertical axis wind turbine performance. Energy 80, 20–31. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2014.11.034

Jain, P., and Abhishek, A. (2016). Performance prediction and fundamental understanding of small scale vertical axis wind turbine with variable amplitude blade pitching. Renew. Energy 97, 97–113. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2016.05.056

Jakubowski, M., Starosta, R., and Fritzkowski, P. (2017). Kinematics of a vertical axis wind turbine with a variable pitch angle in AIP Conference Proceedings (AIP Publishing).

Kerho, M. (2007). Adaptive airfoil dynamic stall control. J. Aircr. 44 (4), 1350–1360. doi:10.2514/1.27050

Kernstine, K. H., Moore, C. J., Cutler, A., and Mittal, R. (2008). Initial characterization of self-activated movable flaps, pop-up feathers. AIAA J. 46. doi:10.2514/6.2008-369

Kinzel, M., Mulligan, Q., and Dabiri, J. O. (2012). Energy exchange in an array of vertical axis wind turbines. J. Turbul. 13, N38. doi:10.1080/14685248.2012.712698

Kirke, B. K., and Lazauskas, L. (2011). Limitations of fixed pitch Darrieus hydrokinetic turbines and the challenge of variable pitch. Renew. Energy 36 (3), 893–897. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2010.08.027

Kiwata, T., Yamada, T., Kita, T., Takata, S., Komatsu, N., and Kimura, S. (2010). Performance of a vertical Axis wind turbine with variable-pitch straight blades utilizing a linkage mechanism. J. Environ. Eng. 5 (1), 213–225. doi:10.1299/jee.5.213

Knight, M., and Bamber, M. J. (1929). “Wind tunnel tests on airfoil boundary layer control using a backward-opening slot,”. Report No. 385 in Nasional advisory committee for Aeronautics (NACA).

Lachenal, X., Daynes, S., and Weaver, P. M. (2013). Review of morphing concepts and materials for wind turbine blade applications. Wind Energy 16 (2), 283–307. doi:10.1002/we.531

Lazauskas, L., and Kirke, B. K. (2012). Modeling passive variable pitch cross flow hydrokinetic turbines to maximize performance and smooth operation. Renew. Energy 45, 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2012.02.005

Lee, T. (2009). Aerodynamic characteristics of airfoil with perforated gurney-type flaps. J. Aircr. 46 (2), 542–548. doi:10.2514/1.38474

Leonczuk Minetto, R. A., and Paraschivoiu, M. (2020). Simulation based analysis of morphing blades applied to a vertical axis wind turbine. Energy 202, 117705. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.117705

Li, C., Xiao, Y., Xu, Y., Peng, Y., Hu, G., and Zhu, S. (2018). Optimization of blade pitch in H-rotor vertical axis wind turbines through computational fluid dynamics simulations. Appl. Energy 212, 1107–1125. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.12.035

Li, D., Li, C., Zhang, W., and Zhu, H. (2021). Effect of building diffusers on aerodynamic performance for building augmented vertical axis wind turbine. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 13 (2). doi:10.1063/5.0025742

Li, Q., Maeda, T., Kamada, Y., Murata, J., Furukawa, K., and Yamamoto, M. (2015). Effect of number of blades on aerodynamic forces on a straight-bladed Vertical Axis Wind Turbine. Energy 90, 784–795. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2015.07.115

Li, Y., Wang, J., and Zhang, P. (2002). Effects of gurney flaps on a NACA0012 airfoil. Flow, Turbul. Combust. 68, 27–39. doi:10.1023/a:1015679408150

Liebeck, R. H. (1978). Design of subsonic airfoils for high lift. J. Aircr. 15 (9), 547–561. doi:10.2514/3.58406

Liu, Q., Miao, W., Bashir, M., Xu, Z., Yu, N., Luo, S., et al. (2022b). Aerodynamic and aeroacoustic performance assessment of a vertical axis wind turbine by synergistic effect of blowing and suction. Energy Convers. Manag. 271, 116289. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2022.116289

Liu, Q., Miao, W., Li, C., Hao, W., Zhu, H., and Deng, Y. (2019). Effects of trailing-edge movable flap on aerodynamic performance and noise characteristics of VAWT. Energy 189, 116271. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.116271

Liu, Q., Miao, W., Ye, Q., and Li, C. (2022a). Performance assessment of an innovative Gurney flap for straight-bladed vertical axis wind turbine. Renew. Energy 185, 1124–1138. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.12.098

Liu, W., and Xiao, Q. (2015). Investigation on Darrieus type straight blade vertical axis wind turbine with flexible blade. Ocean. Eng. 110, 339–356. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2015.10.027

MacPhee, D., and Beyene, A. (2013). Fluid-structure interaction of a morphing symmetrical wind turbine blade subjected to variable load. Int. J. Energy Res. 37 (1), 69–79. doi:10.1002/er.1925

MacPhee, D., and Beyene, A. (2016a). “The straight bladed morphing vertical axis wind turbine,” in ASME 2016 Power Conference (Charlotte, North Carolina, USA: ASME).

MacPhee, D. W., and Beyene, A. (2016b). Fluid–structure interaction analysis of a morphing vertical axis wind turbine. J. Fluids Struct. 60, 143–159. doi:10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2015.10.010

MacPhee, D. W., and Beyene, A. (2019). Performance analysis of a small wind turbine equipped with flexible blades. Renew. Energy 132, 497–508. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2018.08.014

Manfrida, G., and Talluri, L. (2020). Smart pro-active pitch adjustment for VAWT blades: potential for performance improvement. Renew. Energy 152, 867–875. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.01.021

Manwell, J. F. (2009). Wind energy explained: theory, design and application. 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Manwell JgmaALR, J. F. (2009). Wind energy explained: theory, design and application. Second Edition. John Wiley and Sons.

Marchewka, E., Sobczak, K., Reorowicz, P., Obidowski, D. S., and Jóźwik, K. (2021). Application of overset mesh approach in the investigation of the Savonius wind turbines with rigid and deformable blades. Archives Thermodyn. 42 (4). doi:10.24425/ather.2021.139659

Marinić-Kragić, I., Vučina, D., and Milas, Z. (2019). Concept of flexible vertical axis wind turbine with numerical simulation and shape optimization. Energy 167, 841–852. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2018.11.026

Masdari, M., Mousavi, M., and Tahani, M. (2020). Dynamic stall of an airfoil with different mounting angle of gurney flap. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 92 (7), 1037–1048. doi:10.1108/aeat-03-2019-0042

Mathew, S., and Philip, G. S. (2012). “Wind turbines: evolution, basic principles, and classifications,” in Comprehensive renewable energy (Elsevier), 104–123.

McKenna, R., Pfenninger, S., Heinrichs, H., Schmidt, J., Staffell, I., Bauer, C., et al. (2022). High-resolution large-scale onshore wind energy assessments: a review of potential definitions, methodologies and future research needs. Renew. Energy 182, 659–684. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.10.027

Meyer, R., Hage, W., Bechert, D. W., Schatz, M., Knacke, T., and Thiele, F. (2007). Separation control by self-activated movable flaps. AIAA J. 45 (1), 191–199. doi:10.2514/1.23507

Mitchell, S., Ogbonna, I., and Volkov, K. (2021). Improvement of self-starting capabilities of vertical Axis wind turbines with new design of turbine blades. Sustainability 13 (7), 3854. doi:10.3390/su13073854

Mo, W., Li, D., Wang, X., and Zhong, C. (2015). Aeroelastic coupling analysis of the flexible blade of a wind turbine. Energy 89, 1001–1009. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2015.06.046

Mohamed, M. H. (2012). Performance investigation of H-rotor Darrieus turbine with new airfoil shapes. Energy 47 (1), 522–530. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2012.08.044

Mohammed, A. A., Ouakad, H. M., Sahin, A. Z., and Bahaidarah, H. M. S. (2019). Vertical Axis wind turbine aerodynamics: summary and review of momentum models. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 141 (5). doi:10.1115/1.4042643

Motta, V., Zanotti, A., Gibertini, G., and Quaranta, G. (2016). Numerical assessment of an L-shaped Gurney flap for load control. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 231 (5), 951–975. doi:10.1177/0954410016646512

Myose, R., Heron, I., and Papadakis, M. (1996). “Effect of Gurney flaps on a NACA 0011 airfoil,” in 34th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit (AIAA).

Nasri, K., Toubal, L., Loranger, É., and Koffi, D. (2022). Influence of UV irradiation on mechanical properties and drop-weight impact performance of polypropylene biocomposites reinforced with short flax and pine fibers. Compos. Part C. Open Access 9, 100296. doi:10.1016/j.jcomc.2022.100296

Ni, L., Miao, W., Li, C., and Liu, Q. (2021). Impacts of Gurney flap and solidity on the aerodynamic performance of vertical axis wind turbines in array configurations. Energy 215, 118915. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.118915

Ni, Z., Dhanak, M., and Su, T. (2019). Improved performance of a slotted blade using a novel slot design. J. Wind Eng. Industrial Aerodynamics 189, 34–44. doi:10.1016/j.jweia.2019.03.018

Noman, A. A., Tasneem, Z., Sahed, M. F., Muyeen, S. M., Das, S. K., and Alam, F. (2022). Towards next generation Savonius wind turbine: artificial intelligence in blade design trends and framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 168, 112531. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112531

Obidowski, D., Sobczak, K., Jozwik, K., and Reorowicz, P. (2019). Vertical Axis wind turbine with A variable geometry of blades. European Patent Application.

Ouro, P., Stoesser, T., and Ramírez, L. (2018). Effect of blade cambering on dynamic stall in view of designing vertical Axis turbines. J. Fluids Eng. 140 (6). doi:10.1115/1.4039235

Paillard, B., Astolfi, J. A., and Hauville, F. (2015). URANSE simulation of an active variable-pitch cross-flow Darrieus tidal turbine: sinusoidal pitch function investigation. Int. J. Mar. Energy 11, 9–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijome.2015.03.001

Paillard, B., Hauville, F., and Astolfi, J. A. (2013). Simulating variable pitch crossflow water turbines: a coupled unsteady ONERA-EDLIN model and streamtube model. Renew. Energy 52, 209–217. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2012.10.018

Pankonien, A., Faria, C. T., and Inman, D. (2013). “Synergistic smart morphing aileron,” in 54th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference (AIAA).

Pankonien, A. M., Duraisamy, K., Faria, C. T., and Inman, D. (2014b). “Synergistic smart morphing aileron: aero-structural performance analysis,” in 22nd AIAA/ASME/AHS Adaptive Structures Conference (AIAA).

Pankonien, A. M., Faria, C. T., and Inman, D. J. (2014a). Synergistic smart morphing aileron: experimental quasi-static performance characterization. J. Intelligent Material Syst. Struct. 26 (10), 1179–1190. doi:10.1177/1045389x14538530

Pankonien, A. M., Gamble, L., Faria, C., and Inman, D. J. (2016). “Synergistic smart morphing AIleron: capabilites identification,” in 24th AIAA/AHS Adaptive Structures Conference (AIAA).

Paraschivoiu, I., Trifu, O., and Saeed, F. (2009). H-darrieus wind turbine with blade pitch control. Int. J. Rotating Mach. 2009, 1–7. doi:10.1155/2009/505343

Pavese, C., Tibaldi, C., Zahle, F., and Kim, T. (2017). Aeroelastic multidisciplinary design optimization of a swept wind turbine blade. Wind Energy 20 (12), 1941–1953. doi:10.1002/we.2131

Pawsey, N. C. K. (2002). Development and evaluation of passive variable-pitch vertical axis wind turbines. University of New South Wales.

Peng, H. Y., Liu, H. J., and Yang, J. H. (2021). A review on the wake aerodynamics of H-rotor vertical axis wind turbines. Energy 232, 121003. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.121003

Pietrykowski, K., Kasianantham, N., Ravi, D., Jan Gęca, M., Ramakrishnan, P., and Wendeker, M. (2023). Sustainable energy development technique of vertical axis wind turbine with variable swept area – an experimental investigation. Appl. Energy 329, 120262. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120262

Pohl, M., and Riemenschneider, J. (2022). Design and laboratory tests of flexible trailing edge demonstrators for wind turbine blades. Wind Eng. 47, 283–298. doi:10.1177/0309524x221126743