- 1School of Entrepreneurship, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China

- 2School of Management, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China

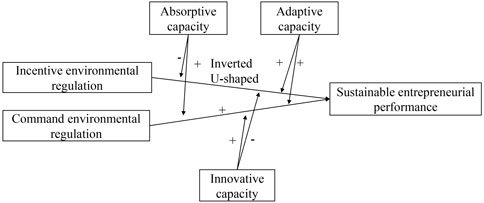

Environmental regulations play important roles in enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurship, and their relationships are affected by enterprises’ dynamic capabilities. This paper analyzed the panel data of China’s new energy industry from 2011 to 2021, aiming to explore the impact of environmental regulations on sustainable entrepreneurship and the mechanism of dynamic capacities between them. The results include: There is an inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulation and enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurial performances, and there is a positive relationship between command environmental regulations and enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurial performances; Both absorptive capacity and innovative capability of dynamic capacities negatively moderate the inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances, and negatively moderate the positive relationship between command environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances. The results highlight the importance of dynamic capabilities for new energy enterprises, and provide a certain enlightening effect on the formulation of environmental regulation policies, as well as the application of enterprises’ dynamic capabilities.

1 Introduction

In the process of global economic development, the problems of environmental pollution and energy depletion have become increasingly prominent. The extensive use of green renewable energy, the development of new energy industries, and the adherence to sustainable development have become the common cognition of the international community. York and Venkataraman (2010) believe that entrepreneurship is the key to promoting sustainable development. The unsustainability of business has a negative impact on human social welfare and the Earth’s ecological environment, and entrepreneurial activities of enterprises should show a higher pursuit of sustainability in products and services. Sustainable entrepreneurship is an entrepreneurial activity that pursues opportunities, protects ecology and communities in the process of realizing the benefits of products and services and focuses on the triple bottom line of economy, ecology and society (Shepherd and Patzelt, 2011). From experiences of developed countries, sustainable entrepreneurship is an important means to improve environment and solve poverty problems, which coincides with the needs of China’s high-quality development. As the largest energy consumer, China is facing huge pressure on carbon dioxide emissions, and improving the sustainable entrepreneurial performances of the new energy industry will be of great significance to China’s energy development, environmental improvement and social problem solving.

Scholars have done a wealth of research on how to promote the development of new energy enterprises. For example, Yin and Zhao (2023) conducted a study on the current situation and problems of the development of the new energy industry in rural China. Yu and Yin (2023) explored the entanglement mechanism between new energy enterprises and rural collectives. Scholars also argued that the triple bottom line theory was used to explain sustainable entrepreneurship, and that economic, ecological and social should be the goals that sustainable entrepreneurs actively focus on (Shahid et al., 2023). But these are not enough to explain sustainable entrepreneurial activities and development of new energy industry in China’s transition economy. On the one hand, China’s economic structural transformation has brought more uncertainty to entrepreneurship, and on the other hand, China’s economic development under the conditions of opening up has intensified overseas competition for entrepreneurship, which will increase the economic pressure on entrepreneurial enterprises. Li et al. (2023) showed that Chinese new energy enterprises were facing financing constraints. Yu et al. (2022) found that Chinese new energy enterprises were technology-intensive, and large R&D investment crowded out the cost of start-up, so it is necessary to consider cost-effectiveness. The challenges faced by new energy enterprises such as technology gaps, energy security, and economic affordability make it more difficult for them to actively transform their entrepreneurial goals from economic growth to the pursuit of economic, ecological and social values. Their sustainable entrepreneurial activities need institutional constraints or support, which can be manifested in the use of environmental regulatory policies to solve problems such as the abuse of natural resources and the evasion of social responsibilities.

The impact of environmental regulations on entrepreneurial performances is widely recognized in academia. Some scholars believed that environmental regulations leaded to an increase in the energy and environmental costs of enterprises, which inhibited the investment in enterprises themselves to a certain extent, and leaded to a reduction in production scale and adversely affect entrepreneurial performances (Du et al., 2022). Other scholars argued that environmental regulations increased investment in renewable energy in China, enhanced corporate environmental initiative, and stimulated green technology innovation, thereby increasing the sustainability of entrepreneurial value chains (Meng et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2019). However, existing studies often ignore the impact of environmental regulations on non-economic performances and the role of enterprises’ own capabilities. Sustainable entrepreneurial performances involve economic performance, as well as non-economic performance such as environmental performance and social performance, and the specific role of environmental regulations needs to be further explored. According to the resource-based view, an enterprise’s abilities to create value can only be enhanced when its capabilities are aligned with environmental conditions (Benedettini et al., 2017). If enterprises lack the dynamic abilities to adapt to changes in the institutional environment, it is difficult to adopt adaptive behaviors, respond to environmental regulatory policies and affect the corresponding behaviors of sustainable entrepreneurship (Chen et al., 2023).

Although existing research shows that dynamic capabilities can affect firms by innovating business models and reconstructing value chains (Tavassoli and Bengtsson, 2018), they are mainly aimed at general entrepreneurial behaviors that aim for commercialization and high financial returns. The sustainable entrepreneurial activities of new energy enterprises have value needs that exceed the market, and traditional dynamic capability theories may not be able to address these issues. Although some scholars have developed a green dynamic capability framework for enterprises, reflecting the mechanisms and challenges faced by green enterprises (Hallerstrand et al., 2023), it also fails to explain how enterprises can use dynamic capabilities to respond to environmental regulations in order to increase sustainable entrepreneurial performances. In addition, dynamic capacities can be divided into multiple dimensions of absorptive capacity, adaptive ability and innovative ability (Wang and Ahmed, 2007), and the differential impact of different dimensions on sustainable entrepreneurship should be distinguished.

The research of this paper attempts to answer the following questions: Firstly, what are the impacts of incentive and command environmental regulations on enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurial performances? Secondly, what are the influencing mechanisms between the different dimensions of dynamic capacities between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances? Responding to these questions, we explored the effects of environmental regulations on sustainable entrepreneurial performances of Chinese new energy enterprises, as well as the moderating effect of three dimensions of dynamic capabilities including absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity and innovative capability from the perspective of triple bottom line and dynamic capacity theories. We used the entropy method to calculate the comprehensive index of sustainable entrepreneurial performances from three aspects: economy, ecology and society, and conducted regression analysis on the panel data of Chinese new energy enterprises from 2011 to 2021 to draw conclusions. The results make it possible to identify the mechanisms of environmental regulations on sustainable entrepreneurship from a dynamic capability perspective. At the same time, we incorporated dynamic capabilities as a contextual factor to expand the research perspective of sustainable entrepreneurship, and to provide theoretical support for enterprises to pursue the balance among economy, ecology and society.

2 Theoretical background and hypotheses development

2.1 Environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances

Environmental regulations can be divided into incentive environmental regulation and command environmental regulation (Fan and Sun, 2020). Incentive environmental regulation is often more flexible, as it makes use of market signals to drive enterprises to take the initiative to protect the environment by economic means such as pollutant discharge fee and environmental taxes (Zhang et al., 2022). On one hand, according to Porter Hypothesis (Porter and Linde, 1995), the increase of the entrepreneurship costs due to appropriately incentive environmental regulation can be offset by more innovation activities and productivity they promote. Therefore, enterprises can gain greater competitiveness and improve their economic efficiency, and then have capabilities to develop ecological and social value, which most possibly carry out the sustainable entrepreneurship (Dun-you, 2021). On the other hand, incentive environmental regulation promotes enterprises to take ecological initiatives and get greater economic and social success (Zhu et al., 2019), i.e., enterprises conduct their entrepreneurial activities in a manner of social responsibility for the benefits of all their stakeholders. However, some scholars questioned the Porter Hypothesis that the negative impact of environmental regulations on enterprises cannot be ignored. They held the view that the economic pressure from incentive environmental regulation would impose higher costs and lower benefits (Martínez-Zarzoso et al., 2019). In particular, new energy enterprises face the problem of technology gap and economic dilemma. When the intensity of environmental regulations exceeds a certain level, high environmental investment costs will crowd out enterprises’ profitable investment, resulting in a decrease in green R&D (Albrizio et al., 2017). And even worse, enterprises may behave badly, such as evading taxes (Li et al., 2018) and assuming less social responsibility in order to transfer the business risks associated with high costs. In general, high costs from incentive environmental regulation may also reduce the outcomes of sustainable entrepreneurship in all aspects, and there may be a non-linear relationship between it and the sustainable entrepreneurial performances of enterprises.

Command environmental regulation adopts mandatory laws to require enterprises to comply, and penalties are imposed on non-compliant enterprises (Fan and Sun, 2020; Jiang et al., 2021). If an enterprise’s pollution discharge fails to meet the relevant standards, the relevant authorities will require it to rectify or even stop its existing projects, and this will result in great losses for enterprises (Wang et al., 2019). In order to protect their profitability, enterprises strive to minimize the cost of environmental protection through technical innovation, which is beneficial to enhance economic performance (Dun-you, 2021; Wang and Yu, 2023). Meanwhile, institutional pressures like command environmental regulation will impel enterprises to disclose environmental information, form independent environmental awareness and behave with social responsibility (Wang et al., 2021). Therefore, even when the intensity of command environmental regulation is high, the high-tech innovation caused by it guarantees the economic profits of enterprise entrepreneurship. At the same time, new energy enterprises have good ecological performances, and their sustainability awareness formed under the pressure of mandatory and normative environmental regulations will further promote their sustainable entrepreneurial behaviors and produce sustainable entrepreneurial performances. Based on the above analyses, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 1a. (H1a): There is an inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances of enterprises.

Hypothesis 1b. (H1b): There is a positive relationship between command environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances of enterprises.

2.2 Moderating effect of dynamic capabilities

Dynamic capabilities are an enterprise’s capabilities to continuously integrate and allocate resources, and upgrade or rebuild core competitiveness in response to changes in external environment in the process of sustainable entrepreneurship (Teece et al., 1997). To better explore the moderating effect of dynamic capabilities on the relationship between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurship, based on the study of scholars Wang and Ahmed (2007), we divided dynamic capabilities into absorptive capability, adaptive capability, and innovative capability for research separately.

2.2.1 Moderating effect of absorptive capability

Absorptive capacity is an enterprise’s capability to recognize knowledge in external environment and transform it for absorption and application in entrepreneurial activities (Jansen et al., 2005). When incentive environmental regulation is at a low level, the incentive effect is limited. Enterprises may be more inclined to take advantage of absorptive capacity for commercialization purposes, i.e., to achieve economic growth of enterprises (Patel, 2019), thus neglecting the environmental and social initiatives. However, as the intensity of external incentive environmental regulation gradually increases or when command environmental regulation is implemented, regardless of upgrading their own pro-environmental and pro-social consciousness or avoiding penalties, the response of enterprises to environmental regulations will increase, and this will impel green R&D of them. The role of absorptive capacity is reflected in two aspects. On one hand, absorptive capacity stimulates enterprises to seek new knowledge and skills related to eco-innovation activities, and effectively explore channels and mechanisms of external opportunities (Delmas et al., 2011). Therefore, they can respond more flexibly to changes in environmental conditions, upgrade business processes in a form that competitors cannot imitate, and increase their sustainable competitive advantages (Pacheco et al., 2018). On the other hand, absorptive capacity helps enterprises to achieve sustainable entrepreneurial goals by equipping them with the capabilities to adopt green workplaces, green production technologies, and generating optimal marketing strategies for entrepreneurial activities (Meirun et al., 2020). When an enterprise has a strong absorptive capacity, its sustainability is more easily promoted by environmental regulations (García-Morales et al., 2020; Kor and Mesko, 2013). Therefore, it is argued that absorptive capacity weakly contributes to the sustainable entrepreneurial performances of enterprises when the intensity of incentive environmental regulation is low, while its negative impact is weakened when the intensity of incentive environmental regulation is high or when command environmental regulation is imposed. Based on the above analyses, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 2a. (H2a): Absorptive capacity has a negative moderating effect on the inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances, and weakens its inverted U-shaped relationship.

Hypothesis 2b. (H2b): Absorptive capacity has a positive moderating effect on the positive relationship between command environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances.

2.2.2 Moderating effect of adaptive capacity

Both incentive environmental regulation and command environmental regulation require enterprises to respond to environmental protection, which will accelerate the technical innovation, but consume their initial costs. Adaptive capacity is an enterprise’s ability to coordinate, integrate, and reorganize its own resources to adapt to the changes in external environment (Wang and Ahmed, 2007), and it works in two ways. The first is “dynamic fit”, i.e., adaptive capacity helps enterprises to continuously adapt to environmental changes over time (Kaltenbrunner and Reichel, 2018). When both incentive environmental regulation and command environmental regulation motivate enterprises to develop environmental and social initiatives, those with stronger adaptive capacity pay more attention to the changes in external environment and emerging technologies. Such enterprises adapt faster and better to external policies, quickly adjust their resource allocation to maximize green innovation and spontaneously assume the social responsibility, which helps improve production efficiency and product quality. The second is “multi-perspective fit”, i.e., adaptive capability makes enterprises’ behaviors in multiple aspects fit with external changes (Kaltenbrunner and Reichel, 2018). Behaviors arising from the adaptive capacity contribute to other enterprises’ competitive advantages, such as a good social image (Teece, 2007; Camisón, 2010). They also enhance enterprises’ accuracy in understanding entrepreneurial market trends, national supporting policies, and consumer demand, so enterprises can reduce the trial-and-error costs, and reshape core competitiveness (Sun et al., 2023). But when the intensity of incentive environmental regulation is too high, enterprises will actively give away some green investments due to the high cost of environmental protection measures. In this case, adaptive capability drives enterprises to adjust their strategies more quickly, favoring entrepreneurial activities that create economic values rather than sustainable values. Therefore, we argued that the roles of both incentive environmental regulation and command environmental regulation in sustainable entrepreneurship can be enhanced by the enterprises’ adaptive capacity. Based on the above analysis, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 3a. (H3a): Adaptive capacity has a positive moderating effect on the inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances, and strengthens its inverted U-shaped relationship.

Hypothesis 3b. (H3b): Adaptive capacity has a positive moderating effect on the positive relationship between command environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances.

2.2.3 Moderating effect of innovative capability

Innovative capability is the capability of enterprises to redevelop or redesign products and services to achieve value creation based on existing or newly acquired knowledge, resources, and skills (Wang and Ahmed, 2007). Green innovation is an important measure for enterprises to address environmental regulations and achieve sustainable entrepreneurial goals, but it is featured in a long time for economic benefit, needs heavy resource investment, and has a high risk. The mechanism by which incentive environmental regulation works on enterprises primarily lies in the market pressure. Enterprises with stronger innovative capacity invest more in R&D activities, resulting in more pollution discharges and higher energy demands from their economic growth (Li and Li, 2023). When enterprises are not subject to mandatory regulations or the market pressure is relatively small, it is difficult for enterprises to balance the economic values and the non-economic values due to enterprises’ profit-seeking nature. In other words, it may not necessary for enterprises to invest innovative capability in green innovation to create more environmental and social value, thus we inferred the innovative capability may weaken the accelerating effects of the incentive environmental regulation on the sustainable entrepreneurship. However, in the long run, innovative capability accelerates the transition process from new technologies to new industries, which inevitably promotes the sustainability of enterprises (Fellnhofer, 2017). As the intensity of incentive environmental regulation increases or when local command environmental regulation is adopted, the market and governmental pressures imposed on enterprise will increase, making it difficult to ignore the environmental impacts. Innovative capability is conducive to green innovation of enterprises, creating significant economic benefits with positive external spillover effects, implementing green development and reducing the economic pressure from environmental regulation. Meanwhile, innovative behaviors are effective to solve social problems (Xu et al., 2020), they can reduce the part of enterprises’ social responsibility evasion caused by business risks. Based on the above analyses, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 4a. (H4a): Innovative capability has a negative moderating effect on the inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances, weakening its inverted U-shaped relationship

Hypothesis 4b. (H4b): Innovative capability has a positive moderating effect on the positive relationship between command environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances.

The research model and hypotheses of this paper are shown in Figure 1.

3 Methodology

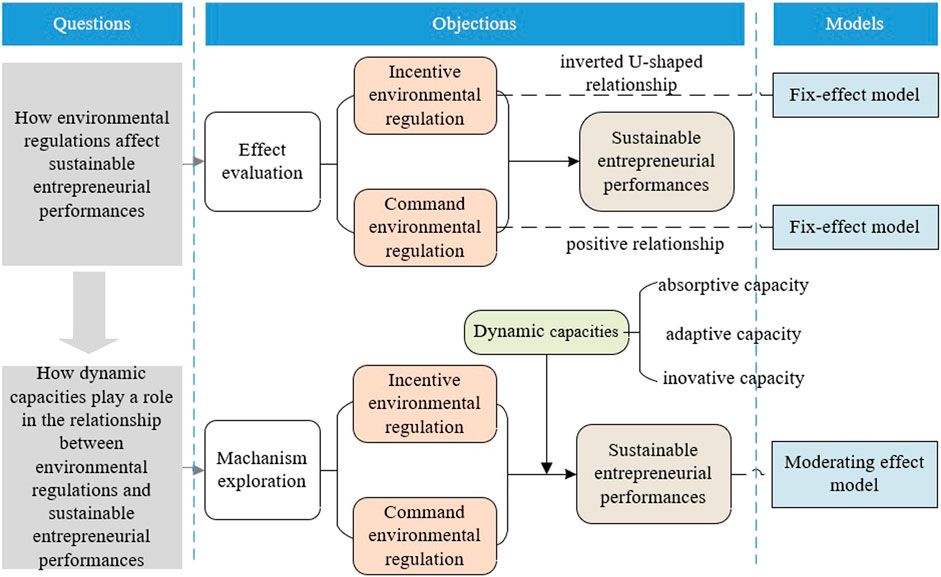

Panel data can provide lower collinearity, more freedom and higher estimation efficiency for research, and panel data analysis method is widely used in researches of external policies on entrepreneurial performances of enterprises (Singh and Delios, 2017). In general, there are three types of models for panel data analysis: pooled model, fixed-effect model, and random-effect model. In order to better select the research model, the F-test was first performed, and the test results (p = 0.000) strongly rejected the null hypothesis, so the fixed-effect model was considered better than the pooled model. Subsequently, the Hausman test was performed, and the test result was Prob > chi2 = 0.031 (<0.05), so the fixed-effect model was considered superior to the random-effect model, and it was selected as the final research model.

There are two research questions in this paper: how incentive environmental regulation and command environmental regulation affect sustainable entrepreneurial performances of enterprises? And how dynamic capacities play a role in the relationship between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances of enterprises? Focusing on the first research question, we constructed a two-way fixed-effect model to evaluate the actual effect of environmental regulations. And in order to solve the second research question, the moderating effect models of dynamic abilities were further constructed. Figure 2 shows the methodological flow chart of this study.

3.1 Main effect models

To test the impact of environmental regulations on sustainable entrepreneurial performances, we constructed two main effect models with incentive environmental regulation (Ier) and command environmental regulation (Cer) as the explaining variables, respectively. In Model (1),

3.2 Moderating effect models

To test the moderating effect of dynamic capabilities in the relationship between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances, we constructed six moderating effect models based on the above main effects models. To test the moderating effects of three dimensions of dynamic capabilities on the inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances, Model (3), (5) and (7) are constructed, in which

4 Data and variables

4.1 Variables

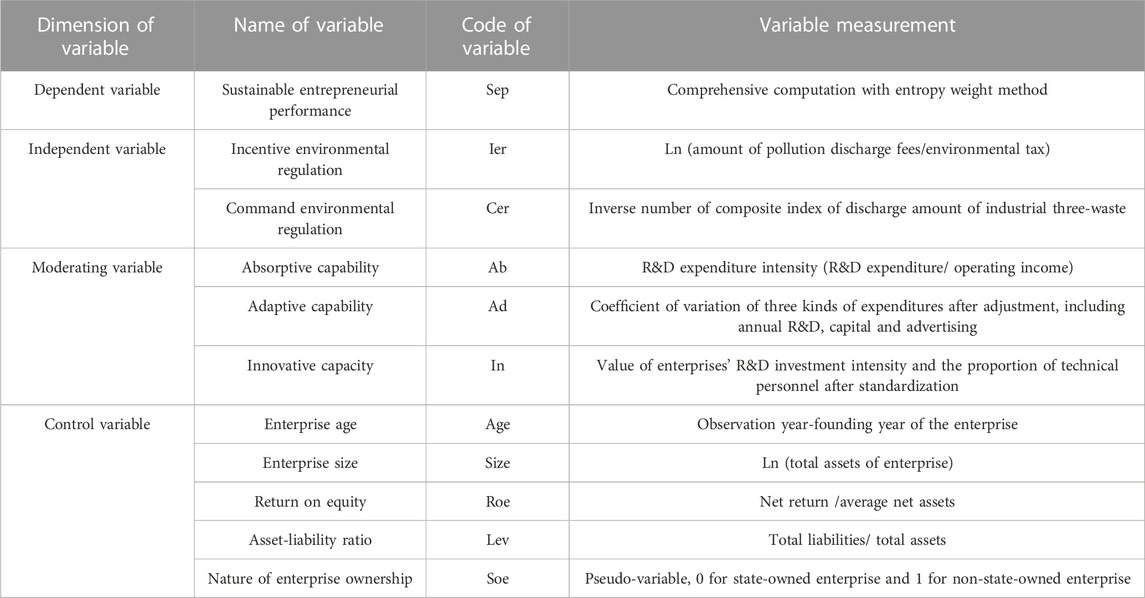

4.1.1 Dependent variable

According to the research of Gu and Wang (2022), enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurial performances consist of three aspects: economic value, ecological value, and social value. Among them, economic value is a measure of the economic effects achieved by enterprises after taking the entrepreneurial behaviors, which is usually the profit income during the entrepreneurial period. The gross operating margin is used to reflect the amount of profit contained in each yuan of operating income of an enterprise, which is the basis of net profit. And we adopted the gross operating margin representing enterprises’ profits, as the substitution measurement of economic value (Liu, 2016; Ding and Xie, 2021). Ecological value is the benefit created by enterprises’ entrepreneurship to the external ecology, which is usually realized in the process of green innovation. The higher the number of patents, the higher the degree of green technology research and development of enterprises, which can lead to a lower level of environmental pollution and a higher contribution to green technology in the process of entrepreneurship. And we used the number of green patents providing environmental benefits as a measurement index of enterprises’ ecological value (Gast et al., 2017; Yin et al., 2022). Social value refers to the social responsibility undertaken by enterprises, which is mainly the value created for the stakeholders. It is measured by social responsibility score in Hexun’s CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) report (Chen et al., 2020), which systematically evaluates the commitment of corporate social responsibility and effectively reflects the social value of enterprises. Finally, the entropy weight method was used to calculate to obtain the composite indexes of sustainable entrepreneurial performances.

4.1.2 Independent variables

In this paper, environmental regulations are divided into incentive environmental regulation (Ier) and command environmental regulation (Cer). Incentive environmental regulation does not adopt mandatory means, the role of it is often realized through economic means, such as the levying the pollution discharge fees. We drew on the study of Ren et al. (2018) to measure incentive environmental regulation by the amount of pollution discharge fees (changed to environmental tax in 2018) levied in the province where the enterprise is located and makes a logarithmic computation. Command environmental regulation imposes mandatory regulation on corporate pollution discharge through the development of relevant regulations or industry standards. If enterprises’ polluting emissions exceed government regulations, they will be punished. The pollution discharge of the “three wastes” (wastewater, sulfur dioxide, and fume) of enterprises can reflect the intensity of such environmental regulations. Therefore, we adopt the entropy weight method to measure the “three-waste” in a comprehensive manner (Ren et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2020). The smaller the composite index, the higher the intensity of command environmental regulation. In order to facilitate the direct observation of the data, we took the inverse number for processing, and the larger the composite index after processing, the higher the intensity of command environmental regulation.

4.1.3 Moderating variables

Dynamic capabilities are the core abilities of enterprises to quickly identify changes in the external environment in a short period of time, flexibly use resources, learn and develop technologies to solve problems (Zhang et al., 2023). They are divided into absorptive capacity (Ab), adaptive capacity (Ad) and innovative capability (In), and these three dimensions are measured as follows with reference to the studies of Yang et al. (2020). Absorptive capacity reflects the ability of enterprises to understand, utilize and transform external knowledge, and is measured by the intensity of R&D expenditures widely used by scholars. Adaptive capacity is to respond flexibly to changes in the external environment. The coefficient of variation of three main expenditures for annual R&D, capital, and advertising is adopted to measure. The larger the coefficient of variation, the weaker the adaptive capacity. To facilitate direct observation of the data, the coefficient of variation adopts the negative number, and the adjusted coefficient of variation is used to measure the enterprises’ adaptive capacity, i.e., the larger the coefficient of variation, the stronger the adaptive capacity. The innovative capability mostly refers to the technically innovative capability, and we measured it from two aspects including the enterprises’ R&D investment intensity and the proportion of technical personnel, and adopted their standardized values to comprehensively measure enterprises’ innovative capability.

4.1.4 Control variables

Enterprise age (Age), enterprise size (Size), return on equity (Roe), asset-liability ratio (Lev), and nature of enterprise ownership (Soe) were selected as the control variables. The enterprise age and size reflect the enterprise’s entrepreneurial foundation, and the enterprise that have been established for a long time and are larger in size have more entrepreneurial resources and start-up capital and are more likely to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship. Return on equity and asset-liability ratio reflect the enterprise’s operating conditions and affects its entrepreneurial orientation. State-owned and non-state-owned enterprises have different risk-taking capacity, which affects the willingness of enterprises to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship. The description of all variables is shown in Table 1.

4.2 Sample and procedure

The research samples of this paper are Chinese new energy enterprises. According to the research of Zhou et al. (2015), the enterprises whose main business and main products are related to solar energy, wind energy, biomass energy, new energy products manufacturing and new energy vehicles are defined as new energy enterprises. And we treated the samples as follows: 1) excluding the sample enterprises with serious deficiencies in indicator data; 2) excluding the sample enterprises with ST* and ST in the enterprise code, in abnormal financial or other abnormal conditions.

The green patent data on environmental value of sustainable entrepreneurial performances are sourced from China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) and compiled manually. The CSR scores for social value are sourced from Hexun.com, and the economic value of sustainable entrepreneurial performances and other relevant financial data are sourced from the database of China Stock Market Accounting Research (CSMAR). The data on environmental taxes, effluent fees and “three-waste” discharge for the environmental regulation are sourced from China Statistical Yearbook, China Taxation Yearbook, China Environment Yearbook, China Environmental Statistical Yearbook and China City Statistical Yearbook, and the data on dynamic capacities as moderating variables are sourced from the annual reports of enterprises. Finally, all of the data formed the non-equilibrium panel of enterprises in new energy industry from 2011 to 2021. In order to avoid the influences of the abnormal value on the data, we adopted the winsorize at the level of 1% to process the continuous variable data, and the data were finally used for regression analysis using Stata17.0.

5 Results and analysis

5.1 Data analysis

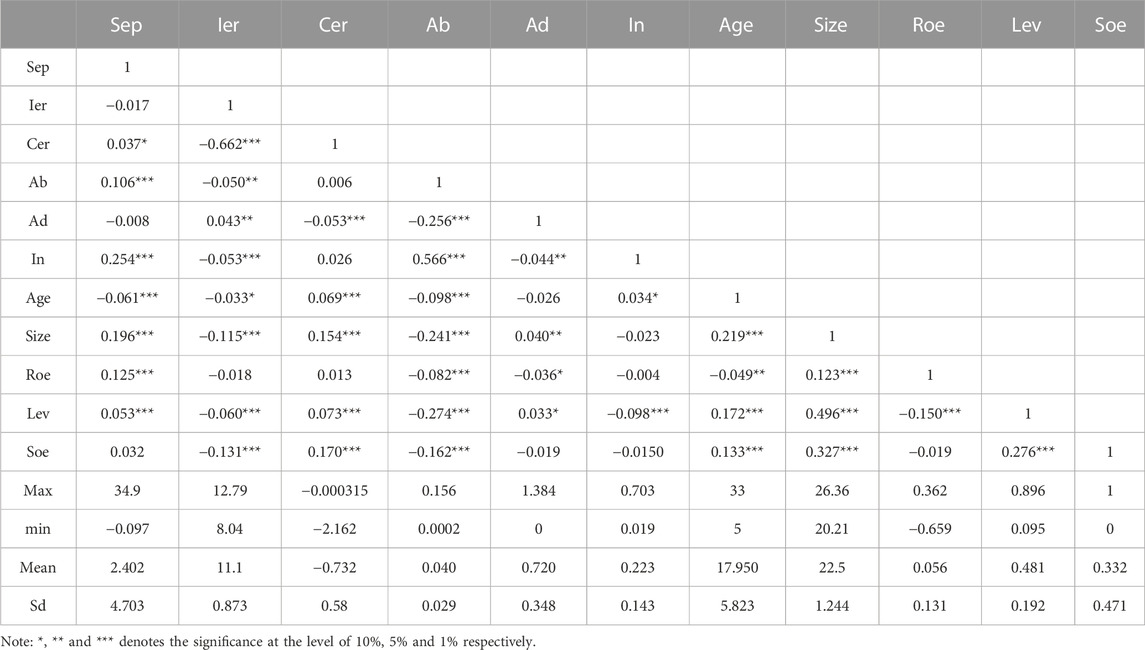

The results of descriptive statistics and person correlation analysis of the main variables are shown in Table 2. From the results, it can be seen that the maximum value of sustainable entrepreneurial performances (Sep) is 34.9 and the minimum value is −0.097 with a variance of 4.703, which indicates that there is a large variation in the level of enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurship. The mean values of incentive environmental regulation (Ier) and command environmental regulation (Cer) are 11.1 and −0.732, respectively, with the variance of 0.873 and 0.58, respectively, indicating that enterprises are affected by environmental regulations and there are differences in the impact degree. From the perspective of dynamic capabilities, the maximum and minimum value of enterprises’ absorptive capacity (Ab), adaptive capacity (Ad) and innovative capability (In) are 0.156 and 0.0002, 1.384 and 0, 0.703 and 0.019, respectively, indicating that some enterprises have relatively poor adaptive capacity, and dynamic capabilities to address environmental changes vary among enterprises, thus the enterprises’ capabilities to achieve sustainable entrepreneurship are also affected. In addition, the variance of enterprise age (Age), enterprise size (Size), return on equity (Roe), asset-liability ratio (Lev) and nature of enterprise ownership (Soe) is 5.823, 1.244, 0.131, 0.192 and 0.471, respectively, indicating that enterprises evolve differently, especially the great differences exist in age and size among the sample enterprises. From the correlation analysis results, it can be known that there is a significance relationship between the sustainable entrepreneurial performances and most of the main variables, where the correlation coefficient between command environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances is 0.037 (p < 0.1), which can tentatively test Hypothesis 1b.

5.2 Hypotheses testing

5.2.1 Environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances

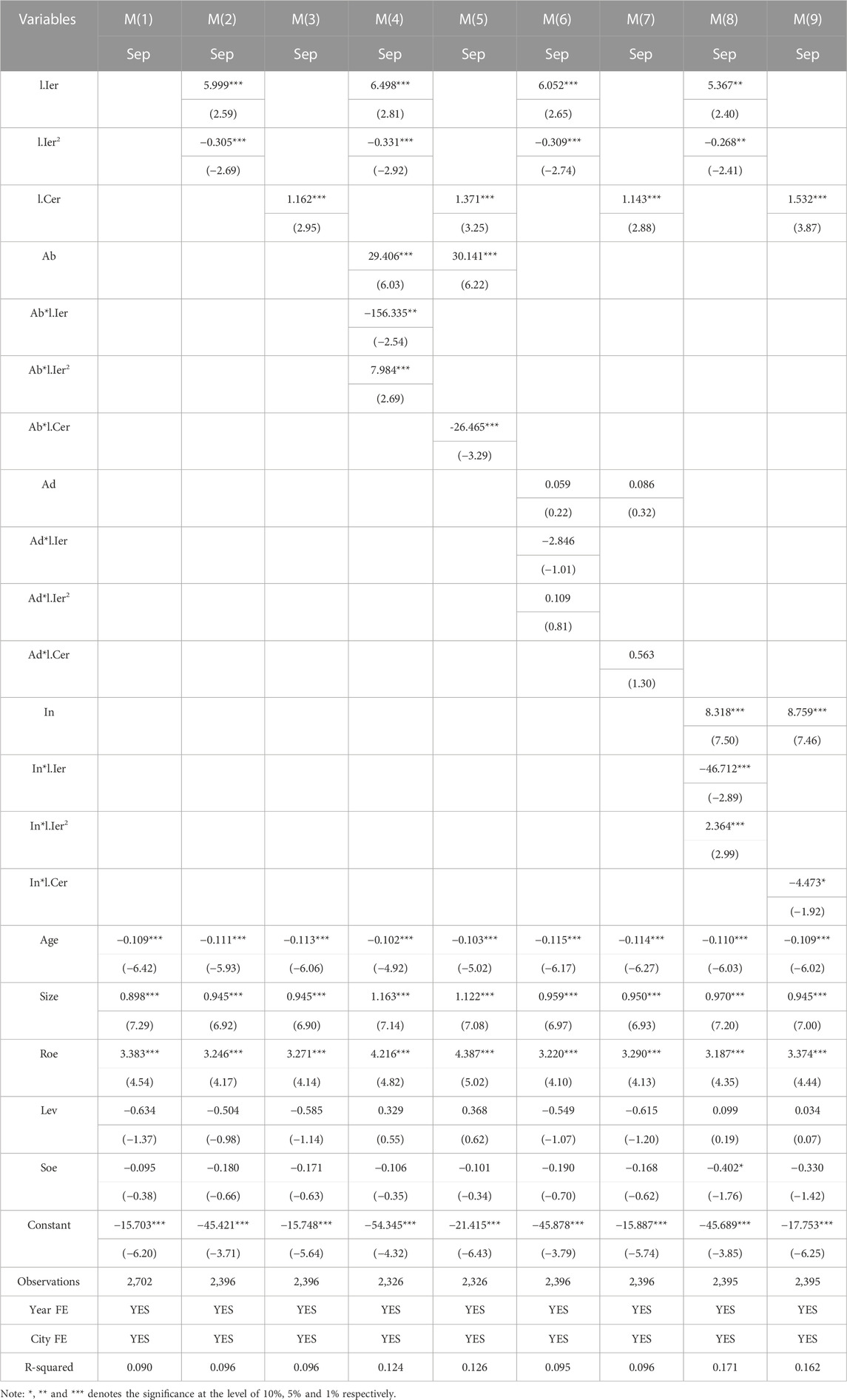

Model (1–3) in Table 3 show the regression analysis results of the main effects of environmental regulations on entreprises’ sustainable entrepreneurial performances, in which Model (1) only includes the regression results of control variables and the dependent variable: sustainable entrepreneurial performances, and R2 of the model is 0.095. Model (2) is the regression test for inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances. The regression results show that the coefficient between the linear term of incentive environmental regulation (Ier) and sustainable entrepreneurial performances is 3.714 (p < 0.1), and the regression coefficient of the quadratic term (Ier2) is −0.189 (p < 0.1). After conducting the u-test, it can be seen that the extreme point exists within the range of the sample data, indicating the inverted U-shaped relationship holds good and Hypothesis 1a is validated. Model (3) shows the regression results of adding the independent variable: the command environmental regulation (Cer) and control variables, and its regression coefficient is significantly positive (β = 1.061, p < 0.05), which verifies the positive effect of command environmental regulation on the enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurial performances, so Hypothesis 1b is validated.

TABLE 3. Regression analysis results of environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances.

5.2.2 Moderating effects of dynamic capabilities

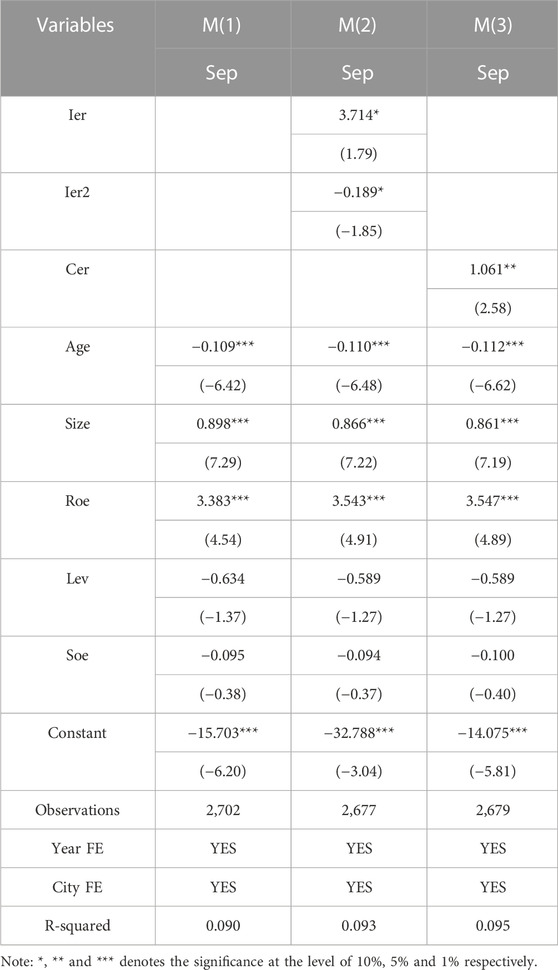

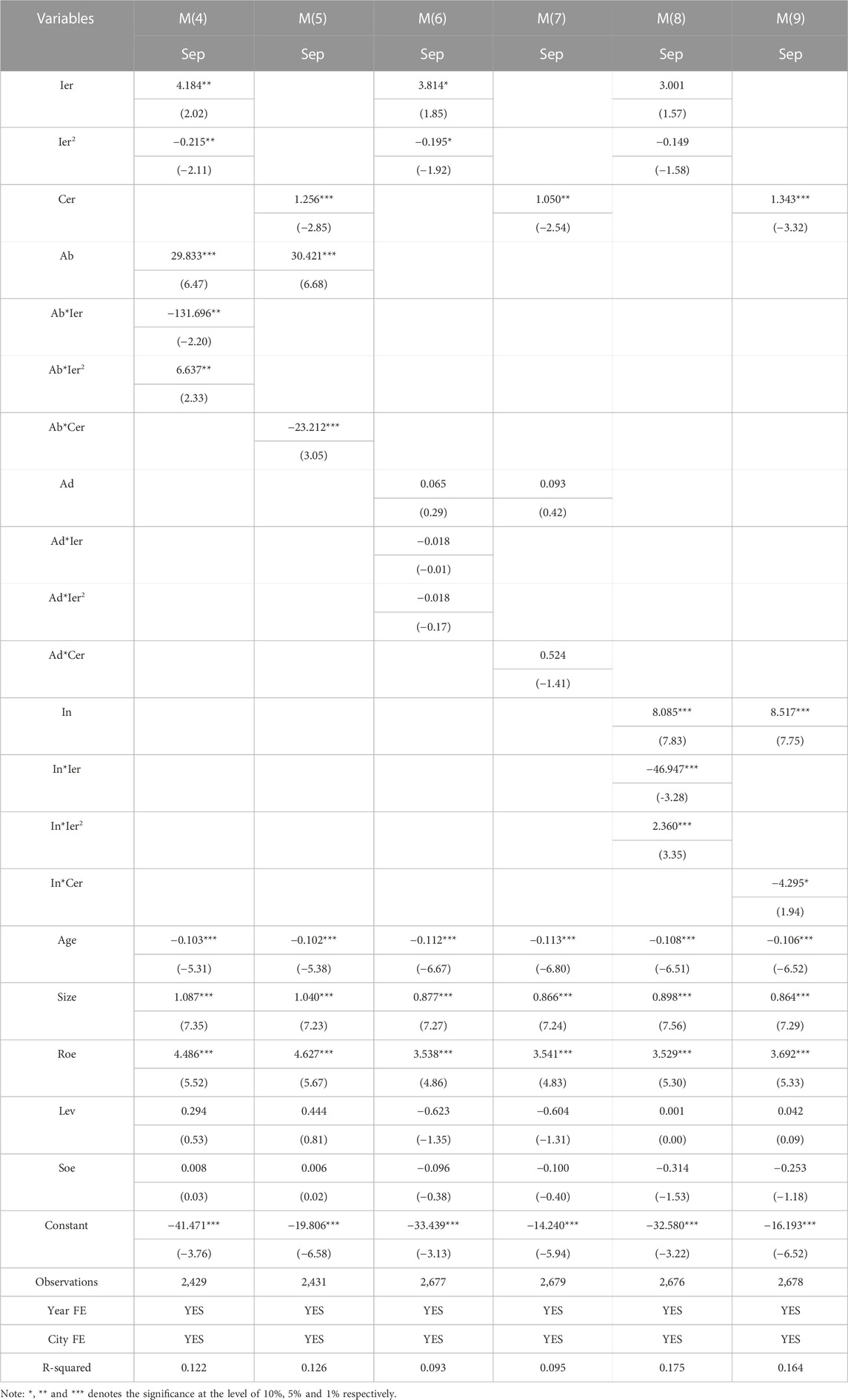

Model (4–8) (9) in Table 4 test the moderating effects of three dimensions of dynamic capabilities: absorptive capacity (Ab), adaptive capacity (Ad) and innovative capacity (In). It can be seen from Model (4), (6) and (8) that the quadratic term efficient of the incentive environmental regulation and the interaction coefficient of absorptive capacity and innovative capacity are significantly positive, 6.637 (p < 0.05) and 2.36 (p < 0.01), respectively, indicating that absorptive capacity and innovative capacity have a negative moderating effect on the inverted U-shaped relationship between market incentive environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performance, i.e., both of them weaken the inverted U-shaped relationship, and Hypothesis 2a and Hypothesis 4a are validated. The interaction coefficient of the quadratic term of incentive environmental regulation and adaptive capacity is −0.018 (p > 0.1), but it is statistically insignificant, indicating that adaptive capacity has no moderating effect on the inverted U-shaped relationship, and Hypothesis 3a is not validated. The results of Model (5) and (9) show that the interaction coefficients of command environmental regulation and absorptive capacity and innovative capacity are significantly negative, −23.212 (p < 0.01) and −4.295 (p < 0.05), respectively, indicating that absorptive capacity and innovative capacity have a negative moderating effect on the positive relationship between the command environmental regulation and enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurial performances, i.e., the stronger the absorptive capacity and the innovative capacity, the weaker the relationship between command environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances. These results are contrary to Hypothesis 2b and Hypothesis 4b. According to Model (7), the interaction coefficient between command environmental regulation and adaptive capacity is positive (β = 0.524, p > 0.1), but it is not statistically significant, indicating that adaptive capacity has no moderating effect on the relationship between command environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances, and Hypothesis 3b is not validated.

TABLE 4. Regression analysis results of the moderating effect of dynamic capacities on the relationship between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances.

5.2.3 Robustness test

The following three approaches are adopted to robustness test. 1) Lag of dependent variables. As a kind of policy, the environmental regulations may have a lag effect on enterprises’ entrepreneurship, so we conducted the regression analysis of independent variables with a one-period lag. Meanwhile, this test can solve part of the endogeneity problems, and the regression results are shown in Table 5. 2) Adding control variables. Since the economic development and the governmental intervention in different provinces where enterprises are located may affect the type and intensity of local environmental regulations, and then affect sustainable entrepreneurial performances, we added provincial-level variables including economic development level (measured by GDP per capita) and the degree of governmental intervention (measured by fiscal expenditure/regional GDP) to re-run the regression. 3) Change the winsorize manner of variables. In this paper, 2% winsorize was applied to all continuous variables. The regression coefficients and significance of the main variables after the above three tests do not meet with significant change from the above mentioned, indicating that the conclusions are robust.

6 Discussion

6.1 Main findings

Previous studies have concluded that environmental regulations may promote (Meng et al., 2020), inhibit (Martínez-Zarzoso et al., 2019), or have a nonlinear effect (Tran and Adomako, 2022) on enterprises’ entrepreneurial performances, but the impact of environmental regulations on the non-traditional entrepreneurial behaviors of new energy enterprises, which focus on energy renewable use and sustainable development goals, still needs to be further confirmed. In this paper, we explored the impact of incentive environmental regulation and command environmental regulation on the sustainable entrepreneurial performances of new energy enterprises, and we found that:

There was an inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances of new energy enterprises. This conclusion is in line with the research of scholars such as Tran and Adomako (2022), which confirms the view that only an appropriate level of environmental regulations can have a positive effect. Incentive environmental regulation brings into play by virtue of non-mandatory incentive behaviors or market pressure, and has an incentive effect on the enterprises’ green innovation and profitability. At the same time, it can increase the green awareness of entrepreneurs and stimulate their sense of social responsibility. They will pay more attention to non-economic benefits such as ecological and social benefits while making profits in business activities, thus upgrading the sustainable entrepreneurial performance. In contrast, strong incentive environmental regulation imposes higher requirements on enterprises’ pollution control. Based on the “cost theory”, environmental regulations increase the pollution control costs and have a “crowding-out effect” on the basic entrepreneurial profitability of enterprises, which easily degrade their market competitiveness. Sustainable entrepreneurial performances are upgraded based on the altruistic level of the entrepreneur. However, environmental protection and social governance essentially consume the enterprise costs, while the decrease in enterprise profits and competitiveness will lead to an egotistic mentality of entrepreneurs, that’s to say, they will compensate for the high cost of pollution abatement by other means, which will lead to a decrease in green R&D and social responsibility. The positive effects of excessively incentive environmental regulation are not sufficient to offset the negative effects from the high cost, but rather reduce enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurial performances.

In addition, we also found that command environmental regulation had a positive effect on the sustainable entrepreneurial performances of new energy enterprises. Similar to incentive environmental regulation, command environmental regulation also promotes green innovation in product and technology and enhance enterprises’ social responsibility. Differently, it imposes mandatory penalties on enterprises that do not comply with the corresponding rules. Faced with high pollution abatement cost, enterprises have to make significant technical innovations to reduce pollution costs and business risks, which will increase their investment in R&D. At the same time, according to cognitive theory, the decisions of entrepreneurs are influenced by outside stimulus. Under the pressure of such policies, entrepreneurs are strongly motivated to make a green transition, exhibit better social responsibility performance, and drive the enterprises to implement decision-making behaviors so as to consistently contribute to sustainable entrepreneurial performances.

Watson et al. (2023) argued that the influencing factors of sustainable entrepreneurship existed at both the macro and micro levels, which were affected by macro factors such as environmental regulations and were also related to the firm’s own capabilities. Previous studies discussed the impact mechanism of environmental regulations, but ignored the role of enterprises’ own capabilities, which had limitations. Therefore, we incorporated dynamic capabilities into the research framework to make up for this shortcoming. And we found that:

Firstly, absorptive capacity of dynamic capabilities negatively moderated the inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances, that’s to say, it enabled the inverted U-shaped curve to become gentle and negatively regulates the positive relationship between command environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances. This finding is contrary to the common understanding that absorptive capacity promotes the enterprises’ performances (Pacheco et al., 2018; Patel, 2019). Appropriate incentive environmental regulation and command environmental regulation promote sustainable entrepreneurial performances through innovation incentive effects. However, the strong absorptive capacity leads to a large amount of knowledge search investment of enterprises, which consumes the actual capital of sustainable entrepreneurship of enterprises. Absorptive capacity promotes enterprises’ competitive advantage on the premise that enterprises’ newly acquired knowledge complements their own knowledge stock (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000). But the actual situation is that the absorptive capacity expands the scope of the enterprises’ search for knowledge, but they do not necessarily obtain heterogeneous knowledge, and a stronger ability to discriminate knowledge is required for enterprises. When enterprises are affected by environmental regulations and need to take into account the realization of economic, ecological and social values, it is difficult for enterprises to be competent in their existing absorptive capacity. The use of misinformation will make it difficult for enterprises to effectively carry out technological innovation, thus inhibiting the positive effect of environmental regulations on sustainable entrepreneurship. The continuous increase of the intensity of incentive environmental regulation will bring greater economic pressure to new energy enterprises that already need to invest heavily in R&D, and they need to have a high absorptive capacity if they want to reduce the negative impact on sustainable entrepreneurial performances. The reason is that reducing R&D investment and reducing social responsibility can offset the high cost of environmental regulation, but it will have a negative impact on sustainable entrepreneurship. Absorptive capacity can improve the efficiency of knowledge absorption and transformation of enterprises, and help enterprises to perform well in product development and profitability even with reduced R&D investment, which will resist the “crowding out effect” of environmental regulations on profitable products.

Secondly, innovative capability of dynamic capabilities negatively moderated the inverted U-shaped relationship between incentive environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances even as its inverted U-shaped curve becomes gentle, and negatively moderated the positive relationship between command environmental regulation and sustainable entrepreneurial performances. Scholars generally agree that innovation has a positive impact on enterprises (Anzola-Roman et al., 2018; Xie and Wang, 2021), but Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) indicated that dynamic capabilities rely on rapid creation of new knowledge and iteration to produce unpredictable outcomes with strong adaptability. Our findings are consistent with that of Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), which confirms that the results of dynamic capabilities are not necessarily stable and positive, and the effectiveness of dynamic capabilities varies with the dynamics of the market in which the enterprises operate. Incentive environmental regulation with lower intensity implies that the market does not fully shape a green sustainability trend or have well-developed intellectual property protection measures, and this is not conducive to the entrepreneurial activities and business development of enterprises. With the increase in the intensity of incentive environmental regulation, the market presents a higher demand for green products and green services, which will further stimulate the improvement of the innovation ability of enterprises, improve their core competitiveness, and eliminate some of the negative effects of incentive environmental regulation on sustainable entrepreneurial performances. When enterprises are subject to command environmental regulations, new energy enterprises are more likely to use innovation capabilities to carry out high-investment and high-risk disruptive innovation in order to reduce cleaning costs. Dually affected by environmental regulations and innovation costs, the capital chain of the enterprise is vulnerable and the innovation may end in failure. When enterprises’ strength and resources are heavily dispersed by environmental regulation policies and substantial innovation, it is difficult to achieve their entrepreneurial goals and they are more vulnerable to the market threats. Therefore, innovative capability weakens the contribution of command environmental regulation to sustainable entrepreneurial performances.

And finally, adaptive capacity of dynamic capabilities had no moderating effect between two environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances. This may be due to the following two reasons. Firstly, the positive effect of adaptive capacity, which enables enterprises to adapt to external changes in all aspects and accelerates the enterprises’ technical innovation, may be offset by the negative effects of environmental regulations, such as high governance costs, squeezed green investment, and avoidance of social responsibility, thus there is no significant effect. Secondly, the effectiveness of adaptive capacity is more dependent on the frequently changing market. Although environmental regulations have an effect on enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurial performances, it does not drastically change the industrial structure, and the market continues to follow a predictable course. Therefore, even if the intensity of environmental regulations changes, it may not promote the building of adaptive capacity. And enterprises have developed relatively stable and efficient processes in response to environmental regulations, the effects of the adaptive capability are may not significant. At this time, the enterprises’ mining and utilization of existing implicit knowledge may play a greater role. Compared with adaptive capacity, enterprises shall devote their efforts to the development of other capabilities, and the influencing factors affecting sustainable entrepreneurship can be explored from more perspectives in the future.

6.2 Theoretical implications

This paper further confirms the relationship between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances. Existing studies have shown the role of environmental regulation on sustainable entrepreneurship of enterprises, but the conclusions were not unified. The main reason is that the differential role of different types of environmental regulations is not taken into account. In this paper, we distinguished environmental regulations into incentive environmental regulation and imperative environmental regulation, and calculated sustainable entrepreneurial performances of enterprises from three aspects: economic, ecological and social values, so as to study and prove the relationship between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances. The conclusions confirm the two-sided nature of environmental regulations on the sustainable entrepreneurial performances of enterprises, clarify the internal logic between them, and provide new ideas for the research of sustainable entrepreneurship of enterprises.

In addition, this paper further reveals the influence mechanism of dynamic capabilities between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances. In previous researches on environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurship, the important role of enterprises’ own capabilities has been neglected. We incorporated dynamic capabilities into the research framework, discussed dynamic capabilities in different dimensions, and studied the specific mechanism of their role between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurship. We divided dynamic capabilities into absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity and innovative capacity, and explored their moderating role between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurial performances. The conclusions illustrate the differentiation and the specific mechanism of dynamic abilities, and confirm the possible negative effects of dynamic abilities.

6.3 Practical implications

The policy implication of this paper is that the formulation and implementation of environmental regulations by the authorities need to be tailored to local conditions. In terms of the type of environmental regulations, it is inevitable that they exist as external policies to promote enterprises’ sustainable development, but their implementation needs to be adjusted according to market conditions. If the majority of enterprises in the region are already aware of sustainable development, focus on environmental protection and social responsibility in the process of entrepreneurship and development, then incentive environmental regulation can be implemented according to the market situation to further promote sustainable entrepreneurship and local sustainable development. If enterprises and the market in the region have not yet formed a higher level of value pursuit, and most of them are still only pursuing their own profits and imposing serious pollution to the environment and society, the government needs to formulate stricter regulations and systems to punish the enterprises that do not comply with the rules, to force them to pay attention to some non-economic values in the process of operation. Viewed from the intensity of environmental regulations, environmental regulations have a certain regulatory effect on enterprises, but too higher intensity of environmental regulations can also have some negative effects. When the region adopts incentive environmental regulation, a small degree of incentive can play a good role in promoting the enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurship. When the intensity of environmental regulation is too high, it is easy to impose economic pressure on enterprises, and if the government does not provide the counterpart funds for support, it is difficult to implement the long-term mechanism of sustainable development. But if the region implements command environmental regulation, it is necessary to pay close attention to the micro mechanism of environmental regulations on enterprises. Only when it induces the enterprises’ innovative compensation effect, enterprises can realize the technical innovation and change their mode of production, the mechanism can play a long-lasting role.

The management implication of this paper is that for new energy enterprises, the deployment and application of dynamic capabilities need to vary according to policies and resources. From the perspective of entrepreneurial awareness, new energy enterprises pay attention to the regeneration and utilization of energy resources, and have a high sense of sustainable entrepreneurship. From the perspective of entrepreneurial behaviors, the regulatory framework is conducive to promoting industry planning and standardizing corporate behavior, so as to have better performance in sustainable entrepreneurship. And from the perspective of market, the regulatory framework regulates market competition and builds a fair and green entrepreneurial environment, which will support the sustainable entrepreneurial behaviors of new energy enterprises. The conclusions of this paper show that under the constraints of environmental regulations, high-frequency changes of new energy enterprises are not suitable for improving sustainable entrepreneurial performances, and how to use dynamic capabilities to benefit from the external policies is the key to improve their core competitive advantages. For example, the company BYD, as a leading company in China’s new energy vehicle industry, has provided a solution that creates multiple benefits by using its dynamic capabilities in a changing market affected by environmental regulations. In the early days of BYD’s entrepreneurship (1995–2007), China’s environmental supervision intensity was not high, and the market did not form a demand trend for new energy products. At this time, BYD focused on traditional fuel vehicle products. In the middle of BYD’s entrepreneurship (2008–2014), China basically formed a system of environmental protection laws and regulations. BYD closely followed the direction of national policies, used dynamic capabilities to carry out disruptive innovation, and shifted from the field of traditional fuel vehicles to the development of electric technology and hybrid technology. Since 2015, China has revised a series of policies such as the Environmental Protection Law, and environmental regulations have been greatly strengthened. BYD adjusted its corporate strategy, attached importance to the development of new energy vehicles, stopped production of fuel vehicles, and carried out gradual innovation in combination with existing technologies at this stage, ranking first in domestic sales of new energy enterprises for six consecutive years since 2017. It can be seen that enterprises should not change blindly. When enterprises are subjected to external policies that consume more of their own resources, the entrepreneurial activities of enterprises should be more conservative. Enterprises should use dynamic abilities to obtain a small amount of useful external knowledge, combine their existing resource advantages and carry out incremental innovation may be more conducive to the development of enterprises. Sustainable development has become an inevitable trend, and conforming to the development trend of the market will be more conducive to creating competitive advantages. Entrepreneurs should establish an awareness of green development, social responsibility, and long-term development. Even though external policies such as environmental regulations may reduce the profits in a short term, entrepreneurs should still pursue long-term development goals, consider how to use dynamic capabilities to offset the economic pressure from the external policies, and obtain economic benefits in a reasonable and correct way instead of hurting stakeholders’ interests.

7 Conclusion

In conclusion, we selected the panel data of Chinese new energy enterprises from 2011 to 2021 to explore the effects of incentive environmental regulation and command environmental regulation on the enterprises’ sustainable entrepreneurial performances, as well as the moderating effects of three dimensions of dynamic capabilities including absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and innovative capability. The research corrects the inherent logic between environmental regulations and sustainable entrepreneurships to some extent, expands the research field of dynamic capabilities, and provides a certain enlightening effect on the formulation of environmental regulation policies and the application of the enterprise’s dynamic capabilities. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations and put forward possible future research directions. We discussed them from three aspects.

Firstly, we selected the gross operating margin, green patent number and social responsibility score of index enterprises from economic, environmental and social aspects, and then used the entropy weight method to construct a comprehensive index system. However, the output of sustainable entrepreneurship includes more than just those we have selected, with a strong focus on environmental and social issues, as well as the common interests of the members of the corporate ecosystem. In the future, more factors can be incorporated into the construction of sustainable entrepreneurship performance indicators, such as tax contribution and job creation. In addition to the entropy weight method, it can also be evaluated and measured in the form of a construction scale.

Secondly, the research samples of this paper are new energy enterprises in China, and it is necessary to consider whether the characteristics of the enterprises themselves will affect the research results. For example, do state-owned companies and private businesses approach sustainable entrepreneurship in very different ways? Although we added the characteristic variables of enterprises such as the nature of ownership to the control variables, we argued that the heterogeneity of the nature of enterprises could be analyzed and discussed in future researches.

Thirdly, we discussed dynamic capabilities in different dimensions, but in the era of digital economy, digital empowerment has become the key to the core competitiveness of enterprise development. It is interesting to discuss whether digital technologies will affect the building of dynamic capabilities of enterprises, and how digital empowerment will affect sustainable entrepreneurship. Future researches should consider the importance of digital technology, and explore the impact mechanism of digital transformation and digital economy on sustainable entrepreneurship.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HP: Writing–review and editing. YP: Writing–original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This paper is supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (No. 23BGL085): Research on the mechanism and path of high-quality development of international entrepreneurship driven by high-value patents (from September, 2023 to December, 2026).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenrg.2023.1295448/full#supplementary-material

References

Albrizio, S., Kozluk, T., and Zipperer, V. (2017). Environmental policies and productivity growth: evidence across industries and firms. J. Environ. Econ. Manage 81, 209–226. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2016.06.002

Anzola-Roman, P., Bayona-Saez, C., and Garcia-Marco, T. (2018). Organizational innovation, internal R&D and externally sourced innovation practices: effects on technological innovation outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 91, 233–247. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.06.014

Benedettini, O., Swink, M., and Neely, A. (2017). Examining the influence of service additions on manufacturing firms' bankruptcy likelihood. Ind. Mark. Manag. 60, 112–125. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.04.011

Camisón, C. (2010). Effects of coercive regulation versus voluntary and cooperative auto-regulation on environmental adaptation and performance: empirical evidence in Spain. Eur. Manag. J. 28, 346–361. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2010.03.001

Chen, L. T., Wu, X., Zhang, Q., and Wang, S. Y. (2023). The influence of "strategic flexibility-environmental ethics configuration on enterprises’ green innovation path under multiple institutional pressures-based on fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). Manag. Rev. 35, 116–126.

Chen, Y. F., Jin, B. X., and Ren, Y. (2020). Impact mechanism of corporate social responsibility on technological innovation performance: the mediating effect based on social capital. Sci. Res. Manag. 41, 87–98.

Delmas, M., Hoffmann, V. H., and Kuss, M. (2011). Under the tip of the iceberg: absorptive capacity, environmental strategy, and competitive advantage. Bus. Soc. 50, 116–154. doi:10.1177/0007650310394400

Ding, F. F., and Xie, H. X. (2021). Can fiscal subsidies and tax incentives stimulate enterprises' high quality innovation? ——evidence from the growth enterprise market. Theory Pract. Financ. Econ. 42, 74–81.

Du, W., Li, M., and Wang, Z. (2022). The impact of environmental regulation on firms? energy-environment efficiency: concurrent discussion of policy tool heterogeneity. Ecol. Indic. 143, 109327. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109327

Dun-you, S. (2021). Heterogeneous environmental regulation, technological innovation and industrial greening in China. J. Guizhou. Univ. Financ. Econ. 39, 83.

Eisenhardt, K. M., and Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 21, 1105–1121. doi:10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::aid-smj133>3.0.co;2-e

Fan, D., and Sun, X. T. (2020). Environmental regulation, green technological innovation and green economic growth. China. Popul. Resour. Environ. 30, 105–115.

Fellnhofer, K. (2017). Drivers of innovation success in sustainable businesses. J. Clean. Prod. 167, 1534–1545. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.197

García-Morales, V. J., Martín-Rojas, R., and Garde-Sánchez, R. (2020). How to encourage social entrepreneurship action? Using Web 2.0 technologies in higher education institutions. J. Bus. Ethics. 161, 329–350. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04216-6

Gast, J., Gundolf, K., and Cesinger, B. (2017). Doing business in a green way: a systematic review of the ecological sustainability entrepreneurship literature and future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 147, 44–56. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.065

Gu, W., and Wang, J. (2022). Research on index construction of sustainable entrepreneurship and its impact on economic growth. J. Bus. Res. 142, 266–276. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.060

Hallerstrand, L., Reim, W., and Malmstrom, M. (2023). Dynamic capabilities in environmental entrepreneurship: a framework for commercializing green innovations. J. Clean. Prod. 402, 136692. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136692

Jansen, J. J., Van Den Bosch, F. A., and Volberda, H. W. (2005). Managing potential and realized absorptive capacity: how do organizational antecedents matter? Acad. Manage J. 48, 999–1015. doi:10.5465/amj.2005.19573106

Jiang, Z., Wang, Z., and Lan, X. (2021). How environmental regulations affect corporate innovation? The coupling mechanism of mandatory rules and voluntary management. Technol. Soc. 65, 101575. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101575

Kaltenbrunner, K., and Reichel, A. (2018). Crisis response via dynamic capabilities: a necessity in NPOs’ capability building: insights from a study in the European refugee aid. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit. Organ. 29, 994–1007. doi:10.1007/s11266-017-9940-3

Kor, Y. Y., and Mesko, A. (2013). Dynamic managerial capabilities: configuration and orchestration of top executives' capabilities and the firm's dominant logic. Strateg. Manag. J. 34, 233–244. doi:10.1002/smj.2000

Li, Q., Pang, L., and Yin, S. (2023). Patent signal and financing constraints: a life cycle perspective and evidence from new energy industry. Front. Energy Res. 11, 1277164. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2023.1277164

Li, W. H., and Li, N. (2023). Green technological innovation, intellectualized transformation and environmental performance of manufacturing enterprises: an empirical study based on threshold effect. Manag. Rev. 1-11.

Li, X. C., Lu, J. K., and Jin, X. R. (2018). Zombie firms and taxation distortion. J. Manag. World. 34, 127–139.

Liu, G. Q. (2016). Analysis of incentive effects of tax preference and financial subsidy policy: an empirical study based on information asymmetry theory. J. Manag. World. 225, 62–71.

Martínez-Zarzoso, I., Bengochea-Morancho, A., and Morales-Lage, R. (2019). Does environmental policy stringency foster innovation and productivity in OECD countries? Energy Policy 134, 110982. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.110982

Meirun, T., Makhloufi, L., and Ghozali Hassan, M. (2020). Environmental outcomes of green entrepreneurship harmonization. Sustainability 12, 10615. doi:10.3390/su122410615

Meng, F., Xu, Y., and Zhao, G. (2020). Environmental regulations, green innovation and intelligent upgrading of manufacturing enterprises: evidence from China. Sci. Rep. 10, 14485. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-71423-x

Pacheco, L. M., Alves, M. F. R., and Liboni, L. B. (2018). Green absorptive capacity: a mediation-moderation model of knowledge for innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 27, 1502–1513. doi:10.1002/bse.2208

Patel, P. C. (2019). Opportunity related absorptive capacity and entrepreneurial alertness. Int. Entrepreneursh. Manag. 15, 63–73. doi:10.1007/s11365-018-0543-2

Porter, M. E., and Linde, C. v.d. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 9, 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Ren, S., Li, X., Yuan, B., Li, D., and Chen, X. (2018). The effects of three types of environmental regulation on eco-efficiency: a cross-region analysis in China. J. Clean. Prod. 173, 245–255. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.08.113

Ren, X. S., Liu, Y. J., and Zhao, G. H. (2020). The Impact and transmission mechanism of economic agglomeration on carbon intensity. China. Popul. Resour. Environ. 30, 95–106.

Shahid, M. S., Hossain, M., Shahid, S., and Anwar, T. (2023). Frugal innovation as a source of sustainable entrepreneurship to tackle social and environmental challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 406, 137050. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137050

Shepherd, D. A., and Patzelt, H. (2011). The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 35, 137–163. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00426.x

Singh, D., and Delios, A. (2017). Corporate governance, board networks and growth in domestic and international markets: evidence from India. J. World Bus. 52, 615–627. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2017.02.002

Sun, J. X., Ma, B. L., and Zhao, L. (2023). Customer environmental pressure, customer participation and green service innovation: the perspective of matching "cognition" and "capability" of enterprises. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. Trans. 2023, 1–27.

Tavassoli, S., and Bengtsson, L. (2018). The role of business model innovation for product innovation performance. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 22, 1850061. doi:10.1142/s1363919618500615

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 28, 1319–1350. doi:10.1002/smj.640

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., and Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 18, 509–533. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::aid-smj882>3.0.co;2-z

Tran, M. D., and Adomako, S. (2022). How environmental reputation and ethical behavior impact the relationship between environmental regulatory enforcement and environmental performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 31, 2489–2499. doi:10.1002/bse.3039

Wang, C. L., and Ahmed, P. K. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: a review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 9, 31–51. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00201.x

Wang, F. m., He, J., and Sun, W. L. (2021). Mandatory environmental regulation, ISO 14001 certification and green innovation: a quasi-natural experiment based on Chinese ambient air quality standards 2012. China. Soft. Sci. Mag. No. 369, 105–118.

Wang, Y., Sun, X., and Guo, X. (2019). Environmental regulation and green productivity growth: empirical evidence on the Porter Hypothesis from OECD industrial sectors. Energy Policy 132, 611–619. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.06.016

Wang, Y., and Yu, L. H. (2023). The influence of environmental regulation instruments on enterprises' preference for green technology innovation. Manag. Rev. 35, 156–170.

Watson, R., Nielsen, K. R., Wilson, H. N., Macdonald, E. K., Mera, C., and Reisch, L. (2023). Policy for sustainable entrepreneurship: a crowdsourced framework. J. Clean. Prod. 383, 135234. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135234

Xie, X., and Wang, H. (2021). How to bridge the gap between innovation niches and exploratory and exploitative innovations in open innovation ecosystems. J. Bus. Res. 124, 299–311. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.058

Xu, H., Zhang, Y., and Zhai, Y. X. (2020). Social entrepreneurial research: a review and prospects. Bus. Manag. J. 42, 193–208.

Yang, L., He, X., and Gu, H. F. (2020). Top management team's experiences, dynamic capabilities and firm's strategy mutution: moderating effect of managerial discretion. J. Manag. World. 36, 168–188+201+252.

Yang, X., He, L., Xia, Y., and Chen, Y. (2019). Effect of government subsidies on renewable energy investments: the threshold effect. Energy Policy 132, 156–166. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.05.039

Yin, C., Salmador, M. P., Li, D., and Lloria, M. B. (2022). Green entrepreneurship and SME performance: the moderating effect of firm age. Int. Entrepreneursh. Manag. 18, 255–275. doi:10.1007/s11365-021-00757-3

Yin, S., and Zhao, Z. (2023). Energy development in rural China toward a clean energy system: utilization status, co-benefit mechanism, and countermeasures. Front. Energy Res. 11, 1283407. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2023.1283407

York, J. G., and Venkataraman, S. (2010). The entrepreneur-environment nexus: uncertainty, innovation, and allocation. J. Bus. Ventur 25, 449–463. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.07.007

Yu, Y., and Yin, S. (2023). Incentive mechanism for the development of rural new energy industry: new energy enterprise–village collective linkages considering the quantum entanglement and benefit relationship. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 1–19. doi:10.1155/2023/1675858

Yu, Y., Yin, S., and Zhang, A. (2022). Clean energy-based rural low carbon transformation considering the supply and demand of new energy under government participation: a three-participators game model. Energy Rep. 8, 12011–12025. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.09.037

Zhang, J., Chen, Y., Li, Q., and Li, Y. (2023). A review of dynamic capabilities evolution-based on organisational routines, entrepreneurship and improvisational capabilities perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 168, 114214. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114214

Zhang, Z. H., Qiu, H., Liu, L., and Lai, J. Y. (2022). Impact of farmers' cooperative directors' green cognition on cooperatives' green entrepreneurial behavior in the situation of environmental regulation. J. Agro-Forestry Econ. Manag. 21, 167–177.

Zhou, Y. H., Pu, Y. L., Chen, S. Y., and Fang, F. (2015). Government support and development of emerging industries---A new energy industry survey. Econ. Res. J. 50, 147–161.

Keywords: incentive environmental regulation, command environmental regulation, sustainable entrepreneurship, absorptive capability, adaptive capability, innovative capability

Citation: Peng H and Pan Y (2024) The effects of environmental regulations on the sustainable entrepreneurship from the perspective of dynamic capabilities: a study based on Chinese new energy enterprises. Front. Energy Res. 11:1295448. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2023.1295448

Received: 16 September 2023; Accepted: 11 December 2023;

Published: 04 January 2024.

Edited by:

Shahjadi Hisan Farjana, Deakin University, AustraliaCopyright © 2024 Peng and Pan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yueyi Pan, eXVleWkxNTU0OTA2MDIyMEAxNjMuY29t

Huatao Peng

Huatao Peng Yueyi Pan

Yueyi Pan