- Law School, Shandong University, Weihai, Shandong, China

The deep-seated problem of carbon neutrality is the energy problem, and the change in energy consumption structure determines the degree of achieving China’s double carbon target. The basic path to achieve the dual carbon goal is to realize the rule of law in energy governance, and the premise of the rule of law in energy governance is to establish a perfect energy legal system. In this paper, we use literary analysis to understand the current research status of this topic, normative and empirical analysis to understand the current legal norms and their implementation status of the implementation of the dual carbon goal in China, and comparative analysis to understand the construction status of the energy legal system of each country in achieving the dual carbon goal. In China, there are also problems such as the dilemma of energy law structure, the lack of dual-carbon legislative goals, the lack of basic framework laws, and the disconnection between energy laws and energy policies, etc. To remedy these dilemmas and shortcomings, the path of constructing a perfect energy law and regulation system is to: establish a Chinese energy development plan with dual-carbon goals; to formulate a basic energy law to lay the framework of China’s energy legal system; to establish the concepts and principles of energy legislation as the basis for maintaining a coordinated and unified energy legal system and so on.

1 Introduction

Global climate change is a serious issue of concern to the international community, and the United Nations, as an international organization, is critical to global climate change issues. With the signing of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Agreement, global climate change governance is on the agenda. On 8 October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, proposing carbon neutrality targets and requiring parties to take carbon-neutral actions (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IPCC, 2018). China actively participates in global climate change action and actively fulfills its international obligations. In September 2020, China committed to the “double carbon target,” in two time periods: first, by around 2030, China’s carbon emissions will reach their peak; second, by around 2060, China will achieve the goal of carbon neutrality (Xi, 2020). The fundamental measure to achieve the double carbon target is “carbon emission reduction,” and carbon emission reduction means a profound energy revolution, while the energy revolution is the process of human use of energy from carbon to carbon-free, which is a fundamental transformation of energy form, structure, technology, management, and other aspects. Fundamentally, whether it is a carbon reduction or an energy revolution, it requires changes in the energy legal system that are compatible with it. The establishment of China’s dual carbon target has undoubtedly posed a serious challenge to China’s existing energy legal system, which requires China to actively respond to the challenge and improve China’s existing energy legal system. The research object of this paper is China’s energy legal system; the research method is a combination of literature analysis, normative and empirical analysis, and comparative study. The research idea and framework of this paper are: firstly, to explore the demand status of China’s energy legal system to achieve the double carbon goal; secondly, to reveal the development path of China’s energy legal system to obtain a general understanding of China’s current energy legal system; secondly, to investigate the defects and deficiencies of China’s current energy legal system; and finally, to propose the path and direction of China’s energy legal system reform. The purpose of this paper is to reveal the energy legal system in China that supports the goal of double carbon. Although some current energy legal systems are valuable to the realization of the dual-carbon goal, they are still generally not adapted to the realization of the dual-carbon goal, and the existing theoretical studies have not yet organically linked the realization of the dual-carbon goal with the construction of the energy legal system, and this paper makes a systematic study in this regard and constructs a perfect energy legal system to support and guarantee the realization of the dual-carbon goal in China.

2 Literature review

Global climate change is beyond the control of any one country in the world and requires the joint efforts of all countries around the globe (Yu et al., 2022a). The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1992, followed by the Kyoto Protocol, a supplement to the UNFCCC, in 1997, and again in 2016 with the signing of The Paris Agreement. Upon inquiry, as of the end of June 2016, there were 197 parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; as of February 2009, a total of 183 countries had adopted the Kyoto Protocol; and as of 29 June 2016, 178 parties had signed the Paris Climate Change Agreement. The signatory countries cover industrialized countries and most developing countries (United Nations Climate Change, 2023). As a signatory country or party, it should actively fulfill its international obligations, and a legal system to promote and guarantee the achievement of carbon neutrality is indispensable to fulfill its carbon reduction commitments. The active formulation and implementation of a carbon-neutral legal system are indispensable means and methods to fulfill commitments and achieve targets (Ko et al., 2022).

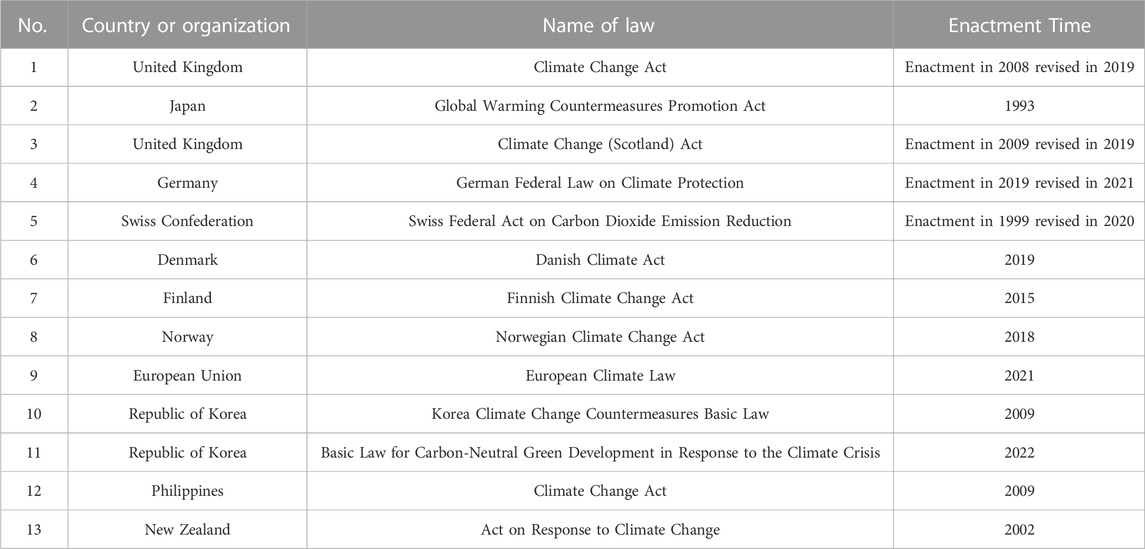

The term “carbon neutral” first appeared in the Second Assessment Report (AR2) of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1995, meaning that the life-cycle carbon cycle of biomass energy sources such as trees is net-zero for the environment, i.e., there is no increase in the amount of carbon dioxide contained in the environment (Zheng, 2022). The term was later absorbed by the Paris Climate Change Agreement and became the UN’s “net-zero” target for binding parties to CO2 emissions by the second half of this century. As a result, the term “carbon neutrality” is a term used in the United Nations’ response to climate change, which will also guide countries in setting up a legal system to promote and safeguard the achievement of carbon neutrality goals, i.e., a legal system related to climate change (Zhang, 2022), as shown in Table 1 below.

TABLE 1. Statistics on the progress of legislation to address climate change in selected international organizations or countries (Tian et al., 2021).

In addition to being one of the first countries in the world to enact specific carbon-neutral legislation, the Climate Change Act 2008, the United Kingdom has enacted several energy legal regimes, including the Energy Act (enacted in 1976, amended in 1983, 2004, 2008, and 2010); the Energy Conservation Act (enacted in 1981); the Electricity Act (enacted in 1989); the Gas Act (enacted 1986, amended 1995); Public Utilities Act (enacted 2000); Sustainable Energy Act (enacted 2003); Climate Change Tax Act (enacted 2001, amended 2002, and amended 2007); Climate Change and Sustainable Energy Act (enacted 2006); Energy Security and Green Economy Act (2010) (enacted); and the Carbon Reduction Commitment Energy Efficiency Act (enacted in 2010) to safeguard the achievement of the UK’s carbon neutrality targets (Yin et al., 2012). Germany is also reforming its energy legal system to accommodate the carbon neutrality target. In terms of energy use, one aspect is the phased requirement to phase out traditional coal power generation by 2030 through the enactment of the Act on the Reduction and Termination of Coal Power Generation and the Act on the Strengthening of the Restructuring of Coal Regions; another aspect is the continuous revision of the Renewable Energy Act, which has been in place since 2000 and has since been revised in 2004, 2011, 2014, 2017, and 2020 revisions to continuously expand the proportion of renewable energy use (Pan and Du, 2022).

The energy sector is the main source of carbon emissions and is the key to achieving the “double carbon” target. Therefore, in addition to the use of technology, it is necessary to establish an energy legal system to support and guarantee the achievement of the dual carbon goal (Cheng et al., 2021).

3 The need for an energy legal regime under the dual carbon goal

The dual carbon target involves two basic concepts: carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. “ Peak carbon refers to the process of reaching a maximum amount of carbon dioxide emissions within a specific time interval, followed by a steady decline and includes three key elements: peak path, peak time, and peak level” (Zhuang et al., 2022). Carbon neutrality is simply “net zero emissions,” which means that the carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere from people’s production and lives is “net zero emissions” through certain carbon offsetting methods, such as forest carbon sinks, ocean carbon sinks, geological storage, and artificial transformation (Yu et al., 2022b). Carbon peaking is a commitment by a country to reach a maximum level of carbon dioxide emissions at a certain point in time, after which emissions are gradually reduced to a “net-zero” state, i.e., a carbon-neutral state, by controlling carbon dioxide emissions through humans or other means.

There are four types of technological pathways and approaches to achieve the “dual carbon goal” in the world (Geels et al., 2018): first, carbon substitution. For example, replacing traditional fossil energy with carbon-free or low-carbon energy sources, such as solar energy, geothermal energy, hydrogen energy, ocean energy, and other new energy sources to replace traditional coal and oil, reducing carbon emissions at sources; second, carbon reduction. That is, industries and fields where carbon substitution cannot be achieved temporarily should adopt energy efficiency technologies and use a series of carbon usage technologies to achieve the purpose of reducing carbon dioxide emissions; thirdly, they should consider carbon sequestration. Fourthly, carbon recycling, i.e., the absorption, conversion, and reuse of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere through biological or chemical means, the main methods currently available are green carbon, blue carbon, and artificial carbon conversion. Green carbon refers to the ability of terrestrial green vegetation to absorb and store atmospheric carbon dioxide; blue carbon, also known as ocean carbon sinks, “is a process, activity, and mechanism that uses marine organisms and ocean activities to absorb carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere and fix it in the deep ocean” (Fan, 2021). The United Nations Environment Programme’s rapid response assessment report, Blue Carbon: The Role of Healthy Oceans in Binding Carbon, published in 2009, concluded that blue carbon captures 55% of the carbon dioxide in natural ecosystems worldwide, “In particular, mangroves, seagrass beds, and coastal salt marshes are capable of capturing and storing significant amounts of carbon” (United Nations Environment Programme, 2009).

The introduction of the “double carbon” target is a major strategic decision made by the Party Central Committee and the State Council based on scientific forecasts of the domestic and international environment and conditions, future economic and social development trends, the new development stage, the implementation of the concept of “green water and mountains are golden mountains,” sustainable development and the community of human destiny, and the requirements for high-quality development based on the comprehensive green and low-carbon transformation of the economy and society (Gao, 2021).

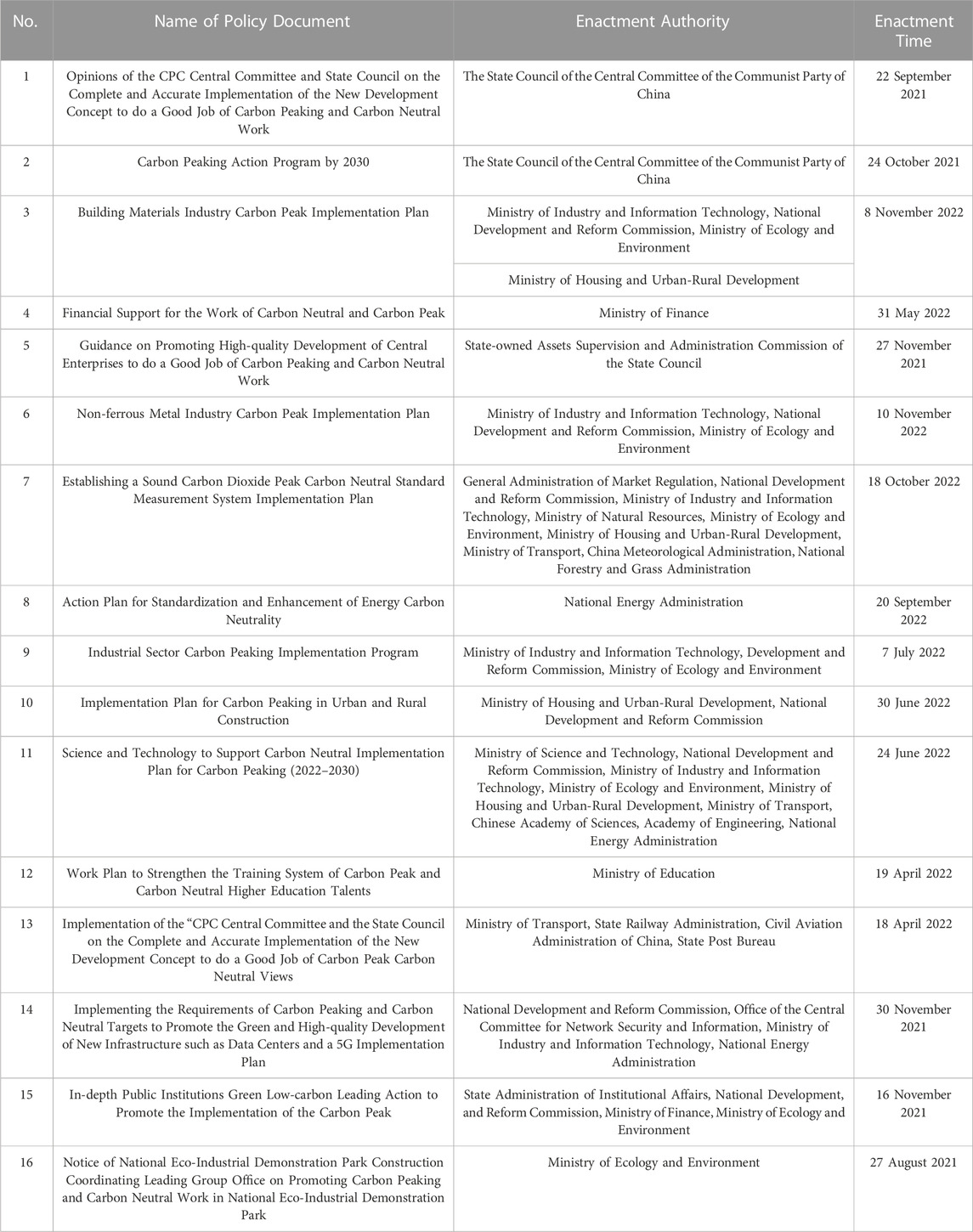

After introducing the double carbon target, the Central Committee, the State Council of the Communist Party of China, and various central departments issued a series of policies to deploy the achievement of the double carbon target; see Table 2.

TABLE 2. China’s central policies to help achieve the “double carbon goal” (Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, 2023).

In addition to policies, the relevant departments in China are actively legislating, such as the development of the Interim Regulations on the Management of Carbon Emissions Trading, the revision of the Electricity Law, the Coal Law, and the Renewable Energy Law, but compared to China’s dual carbon policy, the construction of the energy legal system is lagging and does not meet the requirements of promoting the dual carbon goal.

The implementation of the “double carbon” national strategy and the promotion of the “double carbon” goal requires not only technical (promoting low-carbon technology innovation and application), market (establishing and improving the carbon market), administrative (strengthening government guidance and regulation), green (promoting the comprehensive green transformation of the economy and society), and global (strengthening carbon-neutral international cooperation) efforts (to promote a comprehensive green transformation of the economy and society) and globalization (to strengthen carbon-neutral international cooperation), but also through the establishment of a long-term and stable mechanism to implement the rule of law (Yang, 2022). Whether it is promoting the transition from “high-carbon” to “low-carbon,” overcoming the difficulties and obstacles in the transition process, promoting domestic economic and social development toward the “two-carbon” goal, or promoting international cooperation, there is a need for a comprehensive approach. Whether it is to promote domestic economic and social development toward the “dual carbon” goal or to promote international cooperation, the legal system must follow up and respond, to adjust and guarantee, promote and lead through legal means promptly. In this sense, the process of promoting the “low carbon revolution” is also a process of “rule of law” (Jiao and Xu, 2023). Therefore, China’s current legal system must make appropriate and reasonable institutional arrangements to respond to the current and future development issues and needs in the promotion of the “dual carbon” goal. The energy legal system is an important part of China’s socialist rule of law system and serves the current national energy strategy and the achievement of the dual carbon goal. It should respond to the legal demands of the dual carbon goal promptly, reform the outdated system, and establish a sound energy legal system for achieving the dual carbon goal (Sun et al., 2022).

4 Exploration and development of China's energy legal system

It has been more than 70 years since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. During these 70 years, China’s energy legal system has gone through three stages of exploration, development, and transformation and has gradually established a socialist energy legal system with Chinese characteristics.

4.1 The exploratory phase of the energy legal system (1949–1978)

The 30-year period from 1949 to 1978 was a period of exploration of China’s energy legal system. In terms of the economic system, China went through a planned economic system, a planned commodity economy, and a combination of a planned and market economy. From the perspective of the management system, from centralized power to decentralized power at the local level, the energy management system has been in a state of flux, with the energy management system being in a state of uncertainty, with the central government establishing the Ministry of Fuel Industry in 1949, with the General Administration of Coal Management, the General Administration of Electricity Management, and the Bureau of Hydroelectricity Engineering. In 1958, the central and local governments were decentralized, and the provinces were given partial management powers. The Ministry of Chemical Industry Beginning in 1975, the state gradually transferred its management authority and reshaped the vertical management system of central departments. The Ministry of Fuel and Chemical Industry was abolished, the Ministry of Coal Industry was re-established, and the Ministry of Petrochemical Industry was formed. In terms of energy structure, the situation of “one coal dominant” was highlighted, and with the exploitation of the Karamay oil field in Xinjiang in 1955 and the Daqing oil field in 1959, the proportion of oil in the energy structure became larger, and larger, and China’s “oil-poor country” was removed. China’s “oil-poor” status was lifted. China has experienced many ups and downs in these three decades, but it has gradually become self-sufficient in energy, and the layout of the energy industry has been rationalized from the early days of the coal, oil, and electricity industries to the development of various energy industries. From energy scarcity to self-sufficiency, from the waste of energy during the “Great Leap Forward” period to rational use, China’s energy system is also in the process of exploration.

The First Chinese Political Consultative Conference adopted the Common Programme of the Chinese Political Consultative Conference on 29 September 1949, a document that served as a “provisional constitution,” and article 28 of which stipulated that “the state-run economy is socialist. All undertakings, which are the lifeblood of the national economy and sufficient to control the people’s livelihood shall be operated by the State. All state-owned resources and enterprises shall be the public property of the entire people and the main material basis for developing production and economic prosperity in the People’s Republic and the leading force in the whole social economy.” In effect declaring in the form of a constitutional document that energy is the public property of the whole people and is to be operated by the state in a unified manner, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Organization of the Fuel Industry, promulgated on 24 January 1950, was the law specifically providing for establishing the organization of the fuel industry, and the first constitution after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1954 repeated in its article 6 the provisions of article 28 of the Common Programme. During this period, there were no specific laws on energy, and the State Council’s 1965 appropriation of the Measures for the Delivery of Coal should be considered administrative regulations. The relevant energy management departments, such as the Ministry of Fuel Industry, the Ministry of Coal, and the Ministry of Electricity, have formulated some norms, but they are mostly technical, have a low level of effectiveness, and are rather fragmented.

4.2 The development phase of the energy legal system (1979–2012)

After 1978, China entered the era of reform and opening up, and a consensus was formed on internal reform and opening up to the outside world. In the context of peace and development becoming the theme of the times and sustainable development becoming an international consensus, China’s energy policy was formulated closely around economic construction and sustainable development, with the leading idea of building an energy supply system centered on electricity and diversified development and gradually carrying out market-oriented reforms in areas such as the management system of the energy industry, the energy pricing system and the construction of the energy market. 1985 saw the introduction of the energy industry in China In 1985, China put forward the concept of the energy industry, which insisted that the development of the energy industry should be centered on electricity and the development of electricity was mainly through the development of thermal power, the development of hydropower and the construction of nuclear power plants in a focused and systematic manner.

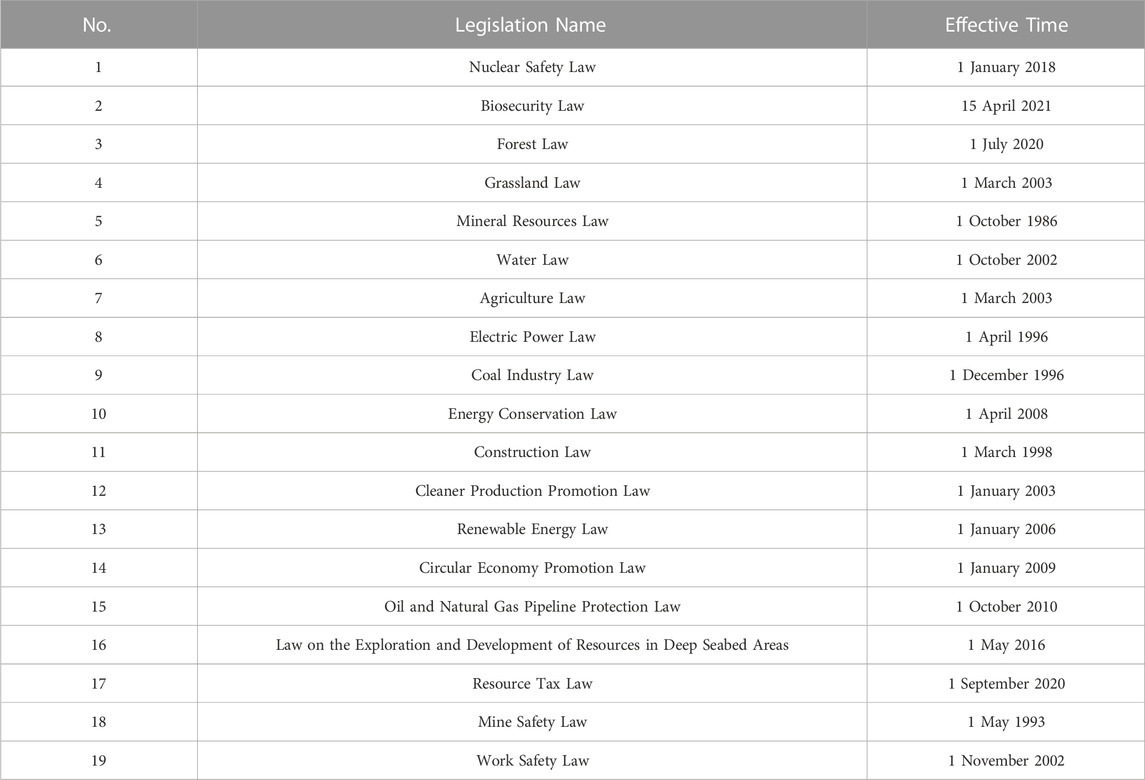

The energy legal system entered a new stage after the reform and opening up. 1984 saw the introduction of the Forestry Law, which established a system for the protection of forests, which are an important carbon sink resource. 1986 saw the introduction of the Mineral Resources Law, which made comprehensive provisions for the exploration, exploitation, and protection of mineral resources such as coal and petroleum; 1988 saw the introduction of the Water Law, which proposed the exploitation of hydraulic resources, and hydropower constituted Article 58 of the 1993 Agriculture Law stipulates that the State protects and makes reasonable use of natural resources such as water, forests, grasslands, wildlife, and plants to prevent them from being polluted or destroyed. 1995, 1996, 1997, and 2005 saw the successful introduction of the Electricity Law, the Coal Law, the Energy Conservation Law, and the Renewable Energy Law, all of which These laws constitute China’s specialized energy laws, while the relevant authorities also initiated the draft of the basic energy law, i.e., the Energy Law, during this period. In addition to the specific energy legal system, related laws include the Grassland Law, the Fisheries Law, the Construction Law, the Law on the Promotion of Clean Production, the Law on the Promotion of Circular Economy, the Law on the Protection of Oil and Gas Pipelines, the Law on Mine Safety, and the Law on Work Safety, etc. Meanwhile, other legislative bodies, such as the State Council, have formulated the Regulations on Foreign Cooperation in the Exploitation of Onshore Petroleum Resources, the Regulations on the Exploration and Development of Offshore Petroleum, the Regulations on the Environmental Protection of Electricity, and the Regulations on the Exploration and Development of Electricity. Regulations on the Administration of Environmental Protection,” “Regulations on the Protection of Electricity,” “Regulations on Compensation for Land Acquisition and Resettlement of Migrants for the Construction of Large and Medium-sized Water Conservancy and Hydropower Projects,” “Regulations on the Safety Management of Reservoir Dams,” “Regulations on the Administration of Power Grid Dispatch,” “Regulations on Energy Conservation in Civil Buildings,” “Regulations on Energy Conservation in Public Institutions,” etc. Local legislative bodies also formulated a series of local energy regulations and rules. This stage laid the groundwork for China’s energy legal system.

4.3 Transformation phase of the energy legal regime (2012 to present)

At the 18th Party Congress in 2012, the construction of socialism with Chinese characteristics entered a new era. At this stage, China’s energy strategy entered a phase of transformation, and in 2014, General Secretary Xi Jinping proposed at the sixth meeting of the Central Leading Group on Finance and Economics to promote a revolution in energy consumption, a revolution in energy supply, a revolution in energy technology, a revolution in the energy system, and an all-round strengthening of international cooperation, guiding the direction and path for China’s energy development in the new era. According to the profound and complex changes in the development situation at home and abroad, Xi Jinping has made a series of important statements such as building a clean, low-carbon, safe, and efficient energy system and doing a good job in the modern energy economy. Responding to the new pattern of the global response to climate change, he made a major strategic decision to achieve peak carbon and carbon neutrality, put forward the construction of a new type of power system, plans and build a new energy system, and meet other deployment requirements. Responding to the global energy supply tensions, he stressed the need to keep the rice bowl of energy firmly intact and stressed the need to keep the rice bowl of energy firmly intact. It was stressed that the rice bowl of energy must be firmly in one’s own hands to ensure a smooth domestic economic cycle under extreme conditions. These important statements are the enrichment and development of a new strategy for energy security, guiding the energy revolution with Chinese characteristics to continue to advance in depth. In the new era and on a new journey, energy development must thoroughly implement the strategic plan of the 20th Party Congress, keep pace with the times, promote the new practice of high-quality energy development, accelerate the construction of a new pattern of energy security, and provide strong support and reliable power for the comprehensive construction of a modern socialist country.

This phase of China’s energy legal system is characterized by the following features (Wang, 2019).

First, the layout of new energy legislation. To promote the green and low-carbon energy transition and high-quality development, China’s basic development idea is to expand the production and consumption of non-fossil energy and increase its proportion in the national energy consumption system. Energy legislation has become a key area of legislation at this stage, with the Nuclear Safety Law enacted and adopted by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on 1 September 2017, and other legislation on new and renewable energy on the agenda; Second, amendments were made to the energy legal system enacted. After the introduction of the double carbon target, the legislature initiated the revision of China’s relevant energy laws that were not adapted to the double carbon target; for example, the Energy Conservation Law went through two amendments in 2016 and 2018; the Coal Law also went through amendments in 2013 and 2016; the Electricity Law also went through two amendments in 2015 and 2018, etc.

Third, improve the formulation of relevant supporting legal systems. For example, after the Renewable Energy Law was enacted, the relevant departments of the State Council issued hundreds of supporting regulations and policies in the areas of resource survey, total target, planning and guidance, application demonstration, industry monitoring, grid connection, and consumption, etc., regulating the management of renewable energy power generation, clarifying the feed-in tariff and cost-sharing system, and formulating technical standards for renewable energy equipment and equipment, engineering construction, and grid connection operation. This has created a good policy environment for promoting the rapid development of renewable energy. Local people’s congresses and governments have formulated and introduced local regulations and policies in line with local realities; for example, Hebei and Zhejiang have formulated regulations on the promotion of renewable energy development and utilization; Heilongjiang, Shandong, Hubei, and Hunan provinces have formulated regulations on rural renewable energy; Jilin and Guangxi have introduced regulations on the development and utilization of water resources; Inner Mongolia, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Ningxia have introduced regulations on the development and utilization of wind, solar, and geothermal energy, etc.; Shanxi has introduced regulations on the development and utilization of renewable energy The relevant regulations on the development and utilization of wind, solar and geothermal energy, etc., and Shanxi has introduced management measures for the fully guaranteed acquisition of renewable energy power generation, and the supporting regulations and policy systems to support the development of renewable energy around the world have been gradually improved.

Fourth, the policy should be implemented first. After the 18th Party Congress, China established the basic content of its energy policy: adhering to the energy development policy of “giving priority to conservation, being domestically based, diversified development, protecting the environment, scientific and technological innovation, deepening reform, international cooperation, and improving people’s livelihood”, promoting changes in the way energy is produced and used, building a modern energy system that is safe, stable, economic, and clean, and striving to support sustainable economic and social development through sustainable energy development. We will strive to support the sustainable development of the economy and society through the sustainable development of energy. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, the State Council, its departments, and local governments have issued relevant policies, such as the “Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on the Complete and Accurate Implementation of the New Development Concept and the Good Work of Carbon Peaks and Carbon Neutrality,” the “Action Plan for Carbon Peaks by 2030” the “Implementation Plan for Science and Technology to Support Carbon Peaks and Carbon Neutrality (2022–2030),” etc. These policies When the conditions for implementation are ripe, the relevant departments will form them into national laws and regulations, which will become an important part of China’s energy legal system (Zhang, 2013).

5 The dilemma of China's energy legal system at this stage under the dual carbon target

Even though the dual carbon goal has not been proposed for a long time, China’s energy legal system has been developing toward “energy conservation and emission reduction.” In the 70 years since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, China has formed an energy legal system to support the dual carbon goal (see Table 3 below).

TABLE 3. China’s current energy law statistics support achieving the dual carbon goal (National People’s Congress, 2023).

The above are the laws enacted by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), while other legislative bodies such as the State Council, various departments of the State Council, local people’s congresses and their standing committees, and local people’s governments have also enacted energy laws and regulations to support the achievement of the dual carbon targets, constituting the legal system of energy in China.

The question of how to achieve the “double carbon” goal, and how to transform the terms “peak carbon,” “carbon neutral” and “low carbon” from concept to reality, is not only a matter of national strategic decision-making but also a matter of not only positioning it as a response to climate change but also incorporating it into the current comprehensive and deepening construction of the rule of law system, the first of which is the legal system. The priority is the legal system, the legal response to the problem, and the concrete actions to implement it. At this level, although China has an energy law system that supports the achievement of the “double carbon” goal, there are certain difficulties in the current legal system and the achievement of the “double carbon” goal:

5.1 Structural dilemmas of the legal system

The structural dilemma of the legal system lies in the lack of an overall or fundamental law on low-carbon energy. The lack of an overall or fundamentally specialized law on low-carbon energy. The current energy legal system in China can be categorized into four types of energy legal systems (Wen, 2021). The first is the conventional energy legal system, such as the Coal Law, the Mineral Resources Law, the Electricity Law, and the Oil and Gas Pipeline Protection Law; the second is the energy conservation legal system, such as the Energy Conservation Law and the Regulations on Energy Conservation in Civil Buildings; the third is the renewable energy legal system, such as the Renewable Energy Law; and the fourth is the legal system in the production and consumption process, such as the Cleaner Production Promotion Law and the Circular Economy Promotion Law. These existing energy legal systems have the following shortcomings: First, they lack a basic or holistic energy legal system. Generally speaking, for a country’s energy legal system to form a system, there must be a basic law on energy to lay the framework of the country’s energy legal system. This aspect is lacking in China. Second, there is a lack of relevant special energy laws, especially in new and renewable energy, such as the Solar Energy Law, Wind Energy Law, Biomass Energy Law, Rural Renewable Energy Law, and Marine Energy Law, etc. China only has a special law on coal, and the only law on oil and gas is the Oil and Gas Pipeline Law, which also lacks a special oil law and a natural gas law. Thus, there is a lack of special laws regulating the regulation of energy.

5.2 Lack of legislative values

Legislation is subject to certain values, and the energy legal system is of course subordinated to certain values and guided by certain value objectives. Existing energy laws do not reflect the values, objectives, or transformative approaches to green and low-carbon development or actions that are embedded in “dual carbon”, which is lacking both in terms of the absence of low-carbon guidance and content in past energy legislation and the absence of relevant (energy) legislation based on low-carbon concepts. The lack of “low-carbon legislation” is reflected both in the lack of guidance and low-carbon content in past energy legislation and the lack of relevant (energy) legislation based on low-carbon concepts (Xiong, 2022). For example, the Coal Law currently in force in China stipulates in Article 1 that “This Law is enacted to reasonably develop, use, and protect coal resources, regulate coal production and operation activities, and promote and safeguard the development of the coal industry.” There is a complete absence of energy conservation and carbon reduction as value objectives of the legislation. Although the Energy Conservation Law proposes energy conservation, it does not have the value objective of carbon reduction or low-carbon, stating that “this Law is enacted to promote energy conservation in society, improve energy usage efficiency, protect and improve the environment, and promote comprehensive, coordinated, and sustainable economic and social development.” The current energy legal system is mostly deficient in the design of value objectives, making it difficult to support the legal system required by the “dual carbon” objective (Ji and Zhang, 2022).

5.3 The legal system is lacking in content

The dual-carbon goal emphasizes the responsibility of policy regulation and the responsibility of carbon-emitting enterprises for carbon emissions, and therefore, the content of the energy system should be designed with the responsibility of carbon emitters for violating the law and the responsibility of regulators to minimize carbon emissions (Liu et al., 2023). However, the existing energy law system does not contain any laws directly related to “double carbon,” carbon intensity, total carbon emission control, or low carbon energy transition, nor is there any relevant content in the various forms of energy law. Existing energy laws are mainly about energy production and consumption, security, and promotion, such as the Electricity Law, which is about “electricity construction, production, supply, and use activities,” and the Coal Law, which is about “engaging in coal production and operation activities” The Coal Law is a law that regulates “engaging in coal production and operation activities,” while the Law on “Double Carbon” targets, energy transformation, low-carbon energy share, and related binding mechanisms, incentive mechanisms, and new “double carbon” energy management system and market system reform, behavioral changes, and various energy There is also no legal arrangement for the rights and obligations of various energy stakeholders (e.g., new energy technology research and development stakeholders, low-carbon energy production and consumption stakeholders).

5.4 Legal system harmonization dilemma

The function of the energy legal system and the formation of the authority of the rule of law require a sound system of energy legal systems with coordinated content and internal and external echoes. However, the existing energy legal system in China has a coordination dilemma, which is highlighted by the coordination dilemma between the old and new energy legal systems, between legal systems of different levels of effectiveness, and between the energy legal system and other legal systems. For example, the Electricity Law, the Coal Law, the Mineral Resources Law, the Renewable Energy Law, and the Energy Conservation Law have the problem of uncoordinated or even conflicting energy management systems; the conflict between legal systems of different levels of effectiveness is even more obvious, as the higher law has been amended, but the lower law has not been amended accordingly, and there is a lag in the amendment of the lower law, which affects Harmonisation of legal systems. There is no effective mechanism to connect the energy legal system with other legal systems, such as the Environmental Protection Law and the Natural Resources Law, resulting in each speaking for itself and failing to bring the overall effect of the legal system into play.

5.5 Disconnect between energy law and energy policy

In the context of the national strategy to achieve the “double carbon” target, “double carbon” policies, including those in the energy sector, have been introduced frequently, and the “1 + N” national strategy is a system of policy implementation. Although the policies have the characteristics of early and pilot implementation, they should be transformed into legal regulations as soon as possible after the implementation is mature to effectively enhance the binding and compulsory power of the regulations. China currently formulates many policies for the realization of double carbon, whether it is the central people’s government or its constituent departments, or local people’s governments at all levels; although they all act actively, they still rely on policies and formulate and introduce a large number of double carbon policies, and there are too few laws and regulations, which leads to a disconnect between laws and policies, energy laws and energy policies cannot effectively synergize, and energy laws are seriously lagging, which also limits the This has led to a disconnect between law and policy, the inability to effectively synergize energy law with energy policy, and a serious lag in energy law, which also limits the effectiveness of energy policy implementation.

6 The improvement path of China's energy legal system under the double carbon target and prospect

To achieve the double carbon goal, it is not only necessary to transform China’s existing energy legal system but also to build an energy legal system adapted to the double carbon goal, so that the development and improvement path of China’s energy legal system is as follows:

6.1 China’s energy development plan with a double carbon goal and energy legislation plan

Energy production and consumption activities are the most important sources of carbon emissions and are crucial to achieving the goal of peak carbon and carbon neutrality, accelerating the new energy revolution, and promoting a low-carbon energy transition. In this regard, it is necessary to formulate a plan for China’s energy development to achieve the dual-carbon goal, which must clarify the basic guidelines for China’s energy development in the coming decades: domestic-based, conservation-first, diversified development, clean and low-carbon, and oil substitution. Domestically means relying on domestic energy resources to meet the needs of economic and social development. To give conservation priority means to vigorously conserve and use energy wisely. Diversified development is to adhere to the energy structure strategy based on coal, with electricity as the center and new energy as the focus. Diversified development means adhering to the energy structure strategy based on coal, with electricity as the center and new energy as the focus. Oil substitution, mainly to accelerate the development of electric and hydrogen vehicles, large-scale promotion of modified methanol fuel, and other ways to achieve the replacement of imported oil and gas (Sun et al., 2022).

The energy development plan is a programmatic and directional document that guides the development of the energy industry. The energy development plan with a dual carbon target must establish the time-phased and graded targets for carbon peaking and carbon neutrality and refine its indicator system. The State Council has already issued the 14th Five-Year Plan for Energy Development (2021–2025), the 14th Five-Year Plan for Renewable Energy Development, and the Action Plan for Carbon Peaking by 2030, and various localities in China have also issued their “The 14th Five-Year Plan for Energy Development also specifies a phased indicator system for energy development under the dual carbon targets of the central government and each local government.”

Based on China’s energy development plan, promotes the rule of law in energy governance and establishes a sound energy legal system. 2023 The Legislative Law was amended for the second time, stipulating in its Article 56 that “the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress shall strengthen the co-ordination of legislative work through legislative planning and annual legislative plans, special legislative plans, and other forms.” China’s double carbon target is China’s commitment to the international community and has become a basic national policy of China, therefore, the relevant energy management departments in China should actively formulate an energy legislative plan, an annual plan for energy legislation, or set up a special plan for energy legislation in the legislative plan of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, to lead the energy legislative work in China in the next five or decade. The relevant energy management departments must seriously study: firstly, the relationship between the double carbon target and the energy development plan; secondly, the relationship between the energy development plan and the energy legislation plan; thirdly, the relationship between the annual plan for energy legislation and the long-term plan for energy legislation; fourthly, the way to realize the leading, regulating, and safeguarding role of energy legal norms on energy development; and fifthly, the relationship between China’s energy legislation and foreign energy legislation. Fifth, the relationship between China’s energy legislation and that of foreign countries; sixth, the feasibility of implementing China’s energy legislation plan or annual plan, etc. The formulation of a sound energy legislation plan to establish a system of energy laws and regulations in line with China’s energy development plan is a prerequisite and the basis for promoting the rule of law in China (Liu et al., 2022).

6.2 Formulate a basic energy law to lay the framework of the energy legal system under China’s dual carbon goal

The energy legal system is an organic and unified whole composed of several sectoral laws, but in this whole, there must be a part of the basic and programmatic laws to oversee the entire energy legal system, which is a country’s basic energy law, such as in Japan Basic Law of Energy Policy, South Koreas Basic Law of Energy, Germanys Energy Economy Act, the United States Energy Policy Act, etc (Du, 2022). Although China has a series of individual laws such as the Law on the Protection of Natural Resources, the Law on Renewable Energy, the Water Law, and the Electricity Law, these individual laws are not comprehensive basic energy laws, and they only regulate certain aspects of energy issues but do not cover all energy issues. The absence of a basic energy law makes it difficult to address the comprehensive issues of energy planning strategies, energy management systems, energy structures, energy security, and coordination between energy and the environment in the energy sector (Li and Zhu, 2021). China has been exploring the formulation of energy law as a basic energy law since 2005, and the first energy law of the People’s Republic of China (a draft for public comments) was issued by the Office of the National Energy Leading Group in 2007, and the energy law (a draft for public comments) was issued again by the National Energy Administration in April 2020, but no such law has been issued yet.

In the context of the dual carbon goal, China should promptly formulate a basic energy law to oversee the construction of China’s entire energy legal system. Drawing on the legislative experience of Japan, the United States, Republic of Korea, Germany and other countries as well as the actual energy development in China, China’s basic energy law, i.e., the Energy Law, should regulate the following six aspects (Wang et al., 2021): first, to clarify the overall energy development strategy and the legal status of energy planning in China and the formulation procedures, so as to provide legal guarantee for the realization of energy development goals; Second, it should establish the legislative guidelines and basic principles of the various individual laws in the energy industry and coordinate the various individual energy legislation; Third, it should establish legal regulations for the comprehensive use of energy and the improvement of energy efficiency, effectively promote technological innovation and industrial restructuring, promote the development of a circular economy, and form energy- and resource-saving mode of economic growth; Fourth, it should institutionalize the relevant energy policies and provide or confirm them in the form of legal norms for various policy systems such as energy resource exploration, market access, management systems, price systems, reserve systems, investment systems, taxation systems, and statistical systems; fifth, establish legal systems to guarantee energy security and energy emergency systems; and sixth, regulate international cooperation and exchanges in energy.

The Energy Law can only be the basis for the homogeneity of the energy legal system if it is the basic law or the supreme law of the individual energy laws and if the internal and external norms of the energy laws, which are interdependent, form a homogeneous and effective energy legal order. The internal and external harmonization of energy law is achieved through the basic energy law, and the individual energy laws cannot exist independently of the basic energy law; they are homogenized by the content, manner of application, and function of the basic energy law and harmonized by the internal and external norms of the basic energy law.

6.3 Establishing the philosophy and principles of energy legislation under the dual carbon goal as the basis for maintaining a harmonized energy legal system

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) establishes five principles for carbon neutrality targets: the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, the principle of equity, the principle of respective capabilities, the principle of sustainable development, and the principle of international cooperation. The most important principle here is first, the “common but differentiated principle,” which has two meanings: first, “shared responsibility,” which means that every country, regardless of its size and wealth, lives on the same planet and that climate change on the planet is caused by the common action of human beings. First, “shared responsibility” means that every country, large or small, rich or poor, lives on the same planet and that the planet’s climate change is the result of the joint action of humankind. It is therefore imperative that all human acts together and takes on a common responsibility to protect the planet. The global nature of climate change is the basic basis for determining the shared responsibility of all countries in the world for global climate change; secondly, “differentiated responsibility” means that, although countries have a shared responsibility to protect global climate capacity resources, they are unequally responsible for the international climate change, depending on their historical responsibility for climate change, their realities, and their future development needs. The responsibility for climate change is unevenly distributed but has “differentiated” consequences.

Some scholars have proposed several principles for energy legislation with a dual carbon goal in China: the principle of enhanced responsibility, the principle of risk prevention, the principle of synergy in reducing pollution and carbon, the principle of joint promotion of carbon reduction and reduction of other greenhouse gases, and the principle of “clean-up before legislation” (Sun and Wang, 2022). Other scholars have examined the principles of energy legislation in the European Union, which, in addition to the traditional principles of environmental law such as sustainable development, public participation, and polluter control, has established three basic principles that regulate certain social relations with certain characteristics: the principle of environmental integrity, the principle of flexibility, and the principle of no harm (Feng, 2022).

China’s energy legislation under the dual carbon target can draw on the UNFCCC and the basic principles of energy in various countries and the actual energy development in China, and should establish the following principles:

6.3.1 The “common but differentiated principle”

The Common but Differentiated Principle is the cornerstone of the international community’s response to climate change. It establishes that all countries should be responsible for global environmental damage, but unequally so. It recognizes that while all countries should be responsible for developing the global community, each country’s contribution to climate protection will vary depending on its capacity. Our energy legislation establishes the “common but differentiated principle,” which means that the requirements for different industries and enterprises are different and that although they all must contribute to the goal of carbon neutrality, they should be differentiated and the system should be designed differently so that a common goal can be established and different strategies can be adopted for carbon reduction strategies.

6.3.2 The principles of collaborative governance and balance of interests

The dilemma in the introduction of China’s basic energy law lies in the dilemma of the game of multiple interests, and the effective solution to this problem requires a balance of multiple interests through collaborative governance, i.e., maximizing the public interest. Cooperative governance realizes the integration of multiple interests in the process of public affairs governance through the coordination of relations and structural coupling between various sub-systems. Under the guidance of the concept of the green development community, market players should focus on “goal synergy” and “coordination of interests,” improve the design of the mechanism for collaborative governance of pollution reduction and carbon reduction, follow the principle of “who pollutes, who pays, who protects, who benefits,” and improve the balance of interests. The principle of “who pollutes, who pays, who protects, who benefits” is followed, laws and policies are improved, cross-regional and cross-sectoral coordination of interests and compensation mechanisms are built with low-carbon energy development as the main line, and the development of green and low-carbon transformation of China’s industrial structure is supported in a diversified manner.

6.3.3 The principle of sustainable development

Article 3.4 of the UNFCCC states that “each party has the right to and shall promote sustainable development,” which is the “principle of sustainable development.” Article 4.7 states that the extent to which developing country Parties can effectively implement their commitments under this Convention will depend on the effective implementation by developed country Parties of their commitments under this Convention relating to financial resources and transfer of technology, taking fully into account that economic and social development and poverty eradication are the first and overriding priorities of developing country Parties. These provisions of the Convention reflect the right to development as well as the right to development. These provisions of the Convention reflect the right to development and the obligation to change unsustainable patterns of production and consumption. Article 2, paragraph 1, of the Kyoto Protocol, also links emission reduction commitments to sustainable development. As a developing country, China must take into account the relationship between carbon emission reduction and economic development, the relationship between carbon emission reduction and people’s livelihoods, and the relationship between carbon emission reduction and the survival of market players. This should also be the principle that China follows in designing its carbon reduction system.

6.4 Implementing a “wraparound” legislative model to develop and amend energy laws and fill in gaps

China has some existing energy laws and regulations that support the dual carbon goals, such as the coal law, the electricity law, the renewable energy law, the energy conservation law, the mineral resources law, the construction law, and the nuclear safety law, etc. However, these laws were enacted in different historical periods, with different legislative concepts and objectives, and there is a certain gap between them and the requirements of the dual carbon goal, and because they are not subordinated to one legislative concept, Moreover, because they are not subordinated to one legislative concept and principle, it is also difficult to effectively connect the institutional design. Simultaneously, from the perspective of the energy legal system that supports the dual-carbon goal, there are still some institutional deficiencies in China, and the gaps in the individual energy laws should be filled as soon as possible. China should speed up the legislation of the Oil and Gas Law and the Atomic Energy Law and draft special laws for some special industries, such as the protection of atomic energy facilities. Additionally, although China has formulated the Renewable Energy Law with the long-term goal of optimizing China’s energy structure, it can also draw on foreign legislative experience in the future at an appropriate time to introduce the Solar Energy Law, the Wind Energy Law, the Geothermal Law, and other renewable energy laws.

To enact some new energy laws as soon as possible and to revise the existing energy legal system as a whole, it is necessary to adopt a “wraparound legislation” model to improve the legislation’s efficiency and the energy system.

The concept of package legislation originated in Germany, which refers to a legislative model in which the legislature, for a common legislative purpose, puts several legal provisions involved in a single law case, arranges them in an orderly manner, and makes a package of enactment or amendment at one time (Wang and Huang, 2015). According to Prof. Chen Xinmin, “Although parliamentary law-making can manifest the concept of sovereignty in the people, the current situation of party rivalry and the uneven legal knowledge of public representatives hinders the goal of efficient parliamentary law-making” (Chen, 2005).

Due to the complexity of life in modern society and the increasing rigidity of legal norms, the enactment or amendment of one law often results in the need to amend other laws that are related to it. Traditionally, the relevant laws would have to be amended separately, which would not allow all the relevant legislative issues to be resolved in a single legislative exercise. This is why the legislative technique of “parcel legislation” allows for the enactment or amendment of laws in conjunction with the enactment or amendment of other laws.

Package legislation is a legislative model and a legislative technique; its greatest benefit is to guarantee the unity of the legal system, prevent the conflict of legal norms, be able to achieve the same legislative purpose, legal system legal norms will not conflict, make up for the loopholes between legal norms, and enhance the operability of regulations. Therefore, the relevant legislative bodies in China can adopt this legislative model to formulate and amend relevant energy laws, which can establish an energy legal system in line with the dual carbon objectives in a relatively short period.

6.5 Parallel energy policies, energy laws, and the legalization of energy policies

Since China committed to the international community to achieve the “double carbon” target, the relevant departments have started to act and introduced a series of double carbon energy policies, so in terms of institutional design, China is “policy first.” At present, a “1 + N” policy system has been formed, led by the “Opinions on the complete and accurate implementation of the new development concept of carbon peaking and carbon neutral work.” Of course, policies and laws have different meanings, as they have certain unique adjustment functions and can achieve goals that are difficult to achieve by legal means (Gong, 2020). However, in the long term, without a pre-designed and structured arrangement in law, the lack of long-term stability, normativity, and sustainability may magnify the legal system’s shortcomings in terms of low carbon development and carbon reduction actions. Without legislative protection, regulation, and facilitation, it is likely that the relevant policies will be distorted or distorted in the process of implementation. In the context of the new era of “dual carbon” goals and the comprehensive rule of law, we must follow a path of legal and policy synergy. Energy laws must be synchronized with low-carbon energy policies, with legislation transforming low-carbon energy policies into energy laws based on the formulation and implementation of policies, including law enforcement and justice, using both laws and policies as the basis for the application so that policies and laws can jointly regulate “dual-carbon” behavior and promote clean technologies. This is a synergistic approach to policy and law in the field of low-carbon energy.

7 Conclusion

The deep-rooted problem of carbon neutrality is an energy issue, and the replacement of fossil energy with renewable energy is the leading direction to achieve the “double carbon” target. However, for a long time, China’s energy resource endowment has been summarized as “one coal,” characterized by “rich coal, poor oil, and little gas,” which seriously restricts the emission reduction process. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China’s total annual energy consumption in 2022 will be 5.41 billion tons of standard coal, an increase of 2.2% compared to 2021, with coal consumption increasing by 4.3%, crude oil consumption decreasing by 3.1%, natural gas consumption decreasing by 1.2%, and electricity consumption increasing by 3.6%. China ranks first in the world in terms of total energy production and coal consumption, and its external dependence on oil and natural gas has reached over 70% and 40%, respectively, putting pressure on energy security. The power industry, which integrates energy producers and consumers, especially the thermal power industry, is under pressure at both the supply and demand ends. At the end of 2022, China’s installed coal power capacity was as high as 1.12 billion kilowatts, accounting for 50% of the world’s installed coal power, and coal power accounted for about 54% of China’s coal use (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022).

Energy legislation is the basis for ensuring the healthy and orderly development of energy in China. Improving the energy legal system to provide legal protection for increasing energy supply, regulating the energy market, optimizing the energy structure, and maintaining energy security is an inevitable requirement for China’s energy development. The establishment of a sound and complete energy legal system is a fundamental guarantee for achieving China’s dual carbon goals. At present, China should comprehensively clean up the existing energy laws and regulations that are incompatible with the requirements of carbon compliance and carbon neutrality, enhance the relevance and effectiveness of relevant laws and regulations, strengthen the formulation of basic energy laws and other individual energy laws, and improve the energy legal system to meet the needs of carbon compliance and carbon neutrality. The improved energy legislation system should be based on the Constitution, with the Energy Law as the basic law, the Energy Conservation Law, the Renewable Energy Law, the Coal Law, the Electricity Law, the Oil and Gas Law, the Atomic Energy Law, and other specific energy laws, with supporting implementation rules to follow.

Each country has different energy resources, different structures, and different energy production and consumption conditions, but the construction of the energy legal system is indispensable, and the goal of fulfilling the task of reducing carbon emissions is the same, although there are differences in the design of the specific content of the energy legal system, the concept, and goal are the same. Therefore, China’s energy legal system is the key measure to support and achieve China’s dual carbon goal as well as China’s solution, which has some enlightening significance for some countries to establish their energy legal system, which also requires countries to strengthen energy cooperation, including the cooperation of energy legal system, and jointly promote the good governance of global climate.

Of course, there are limitations in this study, including the research objects, data, and methods, which only focus on China’s current energy legal system, and lack of in-depth research with other countries in the world, but it is still a framework study, and some contents are left for more in-depth expansion and research

Author contributions

QW determined the basic framework of the thesis, clarified the basic ideas and central thoughts of the paper, and revised and reviewed the thesis. LH and XW collected and organized the literature, wrote the first draft of the thesis, made the preliminary layout of the thesis, unified, and standardized the format of the literature, etc. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by Shandong Provincial Social Science Planning Project (22BKRJ03).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China (2023). Latest policies. Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/index.htm. (accessed on January 25, 2023).

Chen, X. M. (2005). Principles and practice of public law in the state of law and order. China: China University of Political Science and Law Press, 395.

Cheng, Y., Sinha, A., Ghosh, V., Sengupta, T., and Luo, H. W. (2021). Carbon tax and energy innovation at crossroads of carbon neutrality: Designing a sustainable decarbonization policy. J. Environ. Manag. 294, 112957. doi:10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2021.112957

Du, X. W. (2022). The global path towards "double carbon" and the energy revolution. Petroleum Sci. Technol. Forum 41 (1), 3–4. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-302X.2022.01.001

Fan, Z. L. (2021). Developing blue carbon sinks to help achieve carbon neutrality. China Land Resour. Econ. 4, 12. doi:10.19676/j.cnki.1672-6995.000597

Feng, S. (2022). Carbon neutral legislation: EU experience and China's reference: A principle-rule approach. Glob. Law Rev. 4, 182–183. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1009-6728.2022.04.013

Gao, H. (2021). Reflections on China's energy transition path under the "double carbon" target. Int. Pet. Econ. 3, 1–6. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-7298.2021.03.001

Geels, F. W., Schwanen, T., Sorrell, S., Jenkins, K., and Sovacool, B. K. (2018). Reducing energy demand through low carbon innovation: A socio-technical transitions perspective and thirteen research debates. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 40, 23–35. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.11.003

Gong, R. (2020). Constructing a renewable energy legal policy system led by the energy law. China Electr. Enterp. Manag. 16, 27–29. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3361.2020.16.007

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/(accessed January 22, 2023).

Ji, Q., and Zhang, D. Y. (2022). The construction of China's energy security system under the goal of "double carbon" is explored. Natl. Gov. 18, 22–26. doi:10.16619/j.cnki.cn10-1264/d.2022.18.001

Jiao, B., and Xu, C. X. (2023). The evolution logic and future trend of China's energy policy since the 13th Five-Year Plan--a perspective based on the expansion of energy revolution to the "double carbon" goal. J. Xi'an Univ. Finance Econ. 36 (1), 98–112. doi:10.19331/j.cnki.jxufe.2023.01.005

Ko, D. H., Ge, Y. Z., Park, J. S., Liu, L., Ma, C. L., Chen, F. Y., et al. (2022). A comparative study of laws and policies on supporting marine energy development in China and Korea. Mar. Policy 141, 105057. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105057

Li, S. F., and Zhu, G. Y. (2021). Exploration of energy transition path under the vision of "double carbon. Nanjing Soc. Sci. 12, 48–56. doi:10.15937/j.cnki.issn1001-8263.2021.12.006

Liu, M., Xu, X., Peng, K., Hou, P., Yuan, Y., Li, S., et al. (2022). Heparanase modulates the prognosis and development of BRAF V600E-mutant colorectal cancer by regulating AKT/p27Kip1/Cyclin E2 pathway. Liaoning Econ. 7, 58–63. doi:10.1038/s41389-022-00428-0

Liu, Y. Z., Qi, X. L., and Yang, L. H. (2023). Summary of research on low-carbon development of the construction industry under the dual carbon goal. China State Nation 1, 24–28. doi:10.54691/fsd.v3i5.5010

National Bureau of Statistics (2022). Installed power generation capacity to grow with electricity consumption in 2022. Available online at: https://hxny.com/nd-85831-0-50.html (accessed on March 5, 2023).

National People's Congress (2023). 291 laws in force. Available online at: https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_16998667 (accessed on March 5, 2023).

Pan, X. B., and Du, B. J. (2022). A review of German emissions trading system practice based on fuel regulation. Resour. Conservation Environ. Prot. 2, 113–115. doi:10.16317/j.cnki.12-1377/x.2022.02.020

Sun, B. D., Zhang, J., and Han, Y. J. (2022). Trends and paths in the evolution of China's energy system under the goal of "double carbon" to integrate energy security and low carbon transition. China coal. 48 (10), 1–15. doi:10.19880/j.cnki.ccm.2022.10.001

Sun, Y. H., and Wang, T. T. (2022). Research on legislative strategies to promote carbon neutrality in carbon dumping. J. Shandong Univ. (Philosophy Soc. Sci. Ed. 1, 159–160. doi:10.19836/j.cnki.37-1100/c.2022.01.014

Tian, D. Y., Wang, Q., and Zhu, Z. R. (2021). The status of European legislation to address climate change and the lessons learned from its experience. Environ. Prot. 20, 69–72. doi:10.14026/j.cnki.0253-9705.2021.20.016

United Nations Climate Change (2023). History of the convention. Available online at: https://unfccc.int/process/the-convention/history-of-the-convention (accessed on March 5, 2023).

United Nations Environment Programme (2009). Blue carbon: The role of Healthy Oceans in binding carbon. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/7772 (accessed on January 25, 2023).

Wang, J., Deng, L. C., and Feng, S. B. (2021). The significance of energy demand-side management and the development path under the goal of "double carbon" and suggestions. China Energy 43 (9), 50–56. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-2355.2021.09.008

Wang, Q. S., and Huang, L. S. (2015). An examination of the wraparound legislative model-an examination of the wraparound revision of education law. J. Gansu Acad. Political Sci. Law 3, 1–8. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-788X.2015.03.001

Wang, S. Y. (2019). Changes in the legal system in the 40 Years of reform and opening up (environmental law volume). Xiamen: Xiamen University Press, 289.

Wen, X. (2021). Energy transition under the "double carbon" goal: A multidimensional interpretation and Chinese strategy. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 10, 145–151. doi:10.13713/j.cnki.cssci.2021.10.014

Xi, J. (2020). Xi Jinping's speech at the general debate of the 75th session of the UN General Assembly. Available online at: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1678595656103445127&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed January 22, 2023).

Xiong, X. (2022). A Chinese solution for global energy governance reform under the "double carbon" goal. Social. Stud. 1, 155–162.

Yang, X. J. (2022). The decarbonization of China's energy legal system. Polit. Law Ser. 5, 55–65. doi:10.13317/j.cnki.jdskxb.2022.029

Yin, P. H., Dong, W. F., and Wang, Y. (2012). Environmental regulation of greenhouse gas emissions. China: China Environmental Science Press, 10.

Yu, J. H., Xiao, R. L., and Ma, R. F. (2022). Hot areas and trends of "carbon neutral" research in international trade. J. Nat. Resour. 5, 18. doi:10.31497/zrzyxb.20220514

Yu, Y., Radulescu, M., Ifelunini, A. I., Ogwu, S. O., Onwe, J. C., and Jahanger, A. (2022). Achieving carbon neutrality pledge through clean energy transition: Linking the role of green innovation and environmental policy in E7 countries. Energies 17, 6456. doi:10.3390/EN15176456

Zhang, H. (2022). Exploring energy resilience in China’s energy law in the carbon neutrality era. Asia Pac Law Rev. 30, 167–187. doi:10.1080/10192557.2022.2045711

Zhang, J. B. (2013). Research on the legal system of low carbon economy. China: China University of Political Science and Law Press, 287.

Zheng, S. G. (2022). Carbon neutral: A study in conceptual history. Sci. Econ. Soc. 5, 4. doi:10.19946/j.issn.1006-2815.2022.05.001

Keywords: dual carbon targets, energy legal system, rule of law in governance, energy policy, decarbonization transformation

Citation: Huang L, Wei X and Wang Q (2023) Challenges and responses of China’s energy legal system under the double carbon target. Front. Energy Res. 11:1198525. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2023.1198525

Received: 01 April 2023; Accepted: 25 May 2023;

Published: 05 June 2023.

Edited by:

Syed Ahsan Ali Shah, University of Salamanca, SpainReviewed by:

Remus Cretan, West University of Timișoara, RomaniaGalina Chebotareva, Ural Federal University, Russia

Copyright © 2023 Huang, Wei and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Quansheng Wang, d2FuZ3F1YW5zaGVuZ0BzZHUuZWR1LmNu

†ORCID: Lansong Huang, orcid.org/0000-0001-8853-3917; Xuezhi Wei, orcid.org/0000-0002-8899-6804; Quansheng Wang, orcid.org/0000-0002-4676-9478

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work

Lansong Huang

Lansong Huang Xuezhi Wei†‡

Xuezhi Wei†‡ Quansheng Wang

Quansheng Wang