- 1The Key Laboratory of Enhanced Oil and Gas Recovery of Educational Ministry, Northeast Petroleum University, Daqing, China

- 2State Key Laboratory of Natural Gas Hydrates, Beijing, China

The methodology of using CO2 to replace CH4 to recover the natural gas hydrates (NGHs) is supposed to avoid geological disasters. However, the reaction path of the CH4–CO2 replacement method is too complex to give satisfactory replacement efficiency. Therefore, this study proposed a thermochemical reaction system that used the heat and the nitrogen released by the thermochemical reactions to recover NGHs. The performance of the thermochemical reaction system (NaNO2 and NH4Cl) regarding heat generation and gas production under low temperature (4°C) conditions was evaluated, and the feasibility of exploiting NGHs with an optimized formula of the thermochemical reaction system was also evaluated in this study. First, the effects of three catalysts (HCl, H₃PO₄, and NH2SO3H) were investigated at the same reactant concentration and catalyst concentration. It was confirmed that HCl as a catalyst can obtain better heat generation and gas production. Second, the effect of HCl concentration on the reaction was investigated under the same reactant concentration. The results showed that the higher the HCl concentration, the faster is the reaction rate. When the concentration of HCl was greater than 14 wt%, side reactions would occur to produce toxic gas; hence, 14 wt% was the optimal catalyst concentration for the reaction of NaNO2 and NH4Cl at low temperatures. Third, the heat generation and gas production of the thermochemical reaction systems were evaluated at different reactant concentrations (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 mol/L) at 14 wt% HCl concentration. It was found that the best reactant concentration was 5 mol/L. Finally, the feasibility of exploiting NGHs with the optimal system was analyzed from the perspectives of thermal decomposition and nitrogen replacement. The thermochemical reaction system provided by this study is possible to be applied to explore NGHs’ offshore.

1 Introduction

As a new type of clean energy, NGHs have huge reserves. It is estimated that the carbon content of NGHs is twice more than that of the known fossil fuels in the world (Chen et al., 2020). Owing to the enormous amount of natural gas stored in the global NGH reserves, NGHs are considered promising energy resources in the future (Chong et al., 2016). At present, there are four main production methods in recovering NGHs, namely, depressurization, thermal stimulation, inhibitor injection, and CH4–CO2 replacement method (Li et al., 2014; Song et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021). In general, depressurization, thermal stimulation, and inhibitor injection methods are based on the disruption of the NGH equilibrium (Yuan et al., 2011; Song et al., 2019) to destroy the structure of NGHs, which might result in geological disasters due to the collapse of NGH formation. CH4–CO2 replacement, on the other hand, has been proposed as a nondestructive method to recover CH4 (Zhang et al., 2017a; Sun et al., 2019) and sequestrate CO2 (Teng and Zhang 2018; Sun et al., 2021a). However, each method has its limitations. The thermal stimulation method has low gas production efficiency and high cost, and it is difficult to build and maintain the heating equipment; The use of the CH4–CO2 replacement method must be with a sufficient CO2 gas source and transportation pipe, and the replacement efficiency of this method is low (Zhang et al., 2019). To improve the replacement efficiency, Koh et al. proposed to replace CO2 with flue gas (CO2/N2). Their research results showed that the replacement efficiency increased from approximately 64–85% (Kph et al., 2012). In practice, the above methods are combined to obtain better results, e.g., electric heating–assisted depressurization, CH4–CO2 replacement–assisted depressurization, and co-injection of the inhibitor and CO2 (Li et al., 2010; Gupta and Aggarwal 2014; Minagawa 2015; Khlebnikov et al., 2017). Accordingly, we propose a thermochemical reaction to utilize both the heat generated by a thermochemical reaction to provide heat for NGH decomposition and the gas generated by the thermochemical reaction to replace the methane in NGHs.

Thermochemical reactions are widely used in heavy oil development, reservoir fracturing, and plugging removal (Mahmoud et al., 2019). However, the research studies of applying the thermochemical reactions to develop NGHs are rare. Xu et al. proposed a novel method for NGH production, namely, depressurization and in situ supplemental heat (calcium oxide, CaO powder) to provide a large amount of heat for the decomposition of NGHs. At the same time, the Ca(OH)2 produced by the reaction will fill the void volume left by NGH decomposition and hence, improve the permeability of the reservoir (Xu et al., 2021). This method, however, is not verified by experiments. The commonly used thermochemical reaction systems in oil fields include the NH4Cl and NaNO2 system, the urea and NaNO2 system, and the H2O2 system. Considering the factors of heat production, gas production, safety, corrosivity, and cost, the NH4Cl and NaNO2 system is obviously advantageous in NGH production.

Nguyen et al. mentioned that the reaction rate of NH4Cl and NaNO2 is related to the initial temperature, hydrogen ion concentration, and reactant concentration (Nguyen et al., 2003). This reaction of NH4Cl and NaNO2 cannot happen at room temperature unless an acid catalyst is added to the system (Sun et al., 2021b). Normally, the rate of thermochemical reaction increases with the increase of acid catalyst concentration until a threshold concentration is reached which can produce harmful NO2 (Qian et al., 2019). Some researchers have studied the influences of acid catalysts on the reaction and suggested that the pH value of the reaction system shall be controlled within a reasonable range. The experimental results may not exactly be the same, depending on the experimental conditions. Wang et al. mentioned that a red-brown gas was produced when the hydrogen ion concentration reached 0.0356 mol/L (the pH value was ∼1.5) at 30°C (Wang et al., 2020). Wu et al. pointed out that the pH value should be around three for the reaction system of NaNO2 and NH4Cl so that the reaction can occur smoothly at room temperature without producing lots of poisonous red-brown gas (Wu et al., 2007). It is noteworthy that these experiments were carried out above room temperatures. If the NH4Cl and NaNO2 system was applied to exploit the NGHs, it is necessary to study the effect of acid catalyst on the reaction of NaNO2 and NH4Cl under low temperatures of a real NGH reservoir.

This study, thus, aims to use the thermochemical reaction system of NH4Cl and NaNO2 with an acid catalyst to recover the NGH reservoir in the South Sea, China. The heat generation and gas production performance of the thermochemical reaction system of NH4Cl and NaNO2 under the reservoir temperature (4°C) were evaluated, and the influences of catalyst and reactant concentrations were studied by the experiments to obtain an optimal formula for the thermochemical reaction system. In the end, the feasibility of using the optimal thermochemical reaction system to recover NGHs was determined to guide the application of our system in exploiting the NGH reservoir.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

The chemical reagents used in the experiments include NH4Cl (analytical purity), NaNO2 (analytical purity), HCl (37.5%), NH2SO3H (analytical purity), H₃PO₄ (analytical purity), and ethylene glycol (EG, 98%). NH4Cl and NaNO2 were used as reactants. HCl or NH2SO3H or H₃PO₄ was used as a catalyst. EG was used to mix with distilled water as an anti-freezer for maintaining low temperature in a water bath. The experimental temperature in the reactor was maintained at 4°C to simulate the real reservoir temperature (Li et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2014; Natural Gas Hydrates in Flow Assurance 2010). The chemicals used in this study were purchased from Quanrui Reagent Co., Ltd. (Liaoning, China).

2.2 Methods

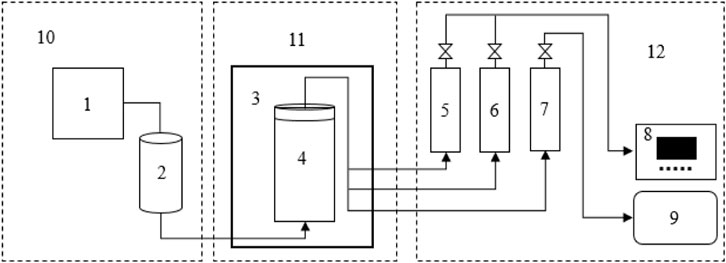

Figure 1 is a schematic graph of the experimental apparatus for the reaction and data collection. The apparatus includes a liquid injection system, low-temperature reaction system, and data acquisition system. The liquid injection system consists of a pump and a steal piston container (200ml, ≤ 32 MPa). The low-temperature reaction system consists of a cylindrical Hastelloy reactor (500ml, ≤ 70 MPa) and a water bath (10 L). The data acquisition system consists of a gas flowmeter, gas collecting bag, temperature, and pressure transducers with an accuracy of ±0.1°C and ±0.01 MPa, respectively.

FIGURE 1. Schematic representation of the experimental apparatus. 1–260D double cylinder constant pressure constant speed pump, 2- piston container, 3-DC-0530 water bath, 4- cylindrical Hastelloy reactor, 5- pressure transducer, 6-PT100 temperature transducer, 7- gas flowmeter, 8- monitor, 9- gas collecting bag, 10- liquid injection system, 11- low-temperature reaction system, 12- data acquisition system.

2.2.1 Experimental Operation Process

The first step was to prepare the solution. First, the aqueous solution of NaNO2 (75 ml) was prepared, and then, it was put into the piston container. Second, the aqueous solution of NH4Cl (75 ml) was prepared, and then, it was put into the reactor. Third, the acid catalyst solution (5 ml) was prepared, and then, it was slowly dropped into the reactor. After the mixed solution was electronically stirred at 500 rpm for 10 min, the reactor was sealed.

The second step was to inject the solution. 75 ml NaNO2 solution was injected into the reactor by a double cylinder pump at a rate of 40 ml/min. The pump was quickly closed after the injection of NaNO2 solution, and the reactor was shaken for 30 s to mix the solution thoroughly.

The third step was to observe the experimental phenomenon and record the data. The temperature change in the reactor was recorded by the data acquisition system, and meanwhile, the gas production rate of the reaction was measured by the gas flowmeter, and the cumulative gas production was collected by the gas collection bag. The overall reaction lasted 1 h.

2.2.2 Optimization of the System Formula

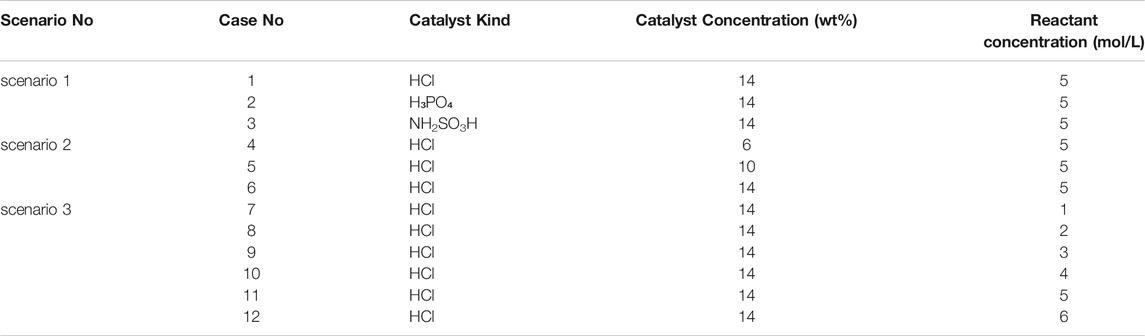

It has been reported that when the molar concentration ratio of NaNO2 with NH4Cl was 1:1, the reaction system can produce more gas at a better gas production rate (Wang et al., 2020). Therefore, the experiments of this study were carried out at a molar concentration proportion of 1:1 of NaNO2 with NH4Cl. Three scenarios and twelve experiments were carried out in this study to investigate the effects of the catalyst type, catalyst concentration, and reactant concentration, respectively (see Table 1). Temperature, gas production rate, and (the total of something over time) cumulative gas production were selected as key parameters to evaluate the performance of the thermochemical reaction systems to select the best formula.

In scenario 1, the heat generation and gas production performance of the thermochemical reaction system was investigated by using three kinds of acid catalysts at a reactant concentration of 5 mol/L and catalyst concentration of 14 wt%. In scenario 2, the best catalyst from scenario 1 was utilized to evaluate the influence of catalyst concentration at 6, 10, and 14 wt% on the heat generation and gas production of the thermochemical reaction system. While in scenario 3, the concentration of the reactants was changed from 1 to 6 mol/L to explore the impact of reactant concentrations on the heat generation and gas production performance of the thermochemical reaction system; the optimum catalyst kind from scenario 1 and the optimal catalyst concentration from scenario 2 were used in scenario 3.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Effect of the Catalyst Type

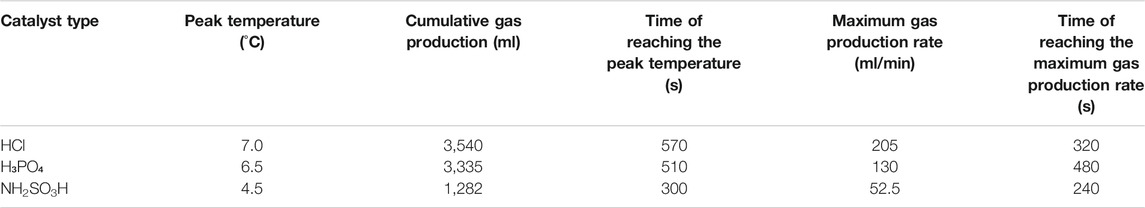

In scenario 1, the reaction was performed at NaNO2 or NH4Cl concentration of 5 mol/L and acid catalysts’ concentration of 14 wt% by using three kinds of catalysts, that is, HCl, H₃PO₄, and NH2SO3H. The temperature, gas production rate, and cumulative gas production profiles were compared at the equal volume of these three catalyst solutions. The experimental results are shown in Table 2.

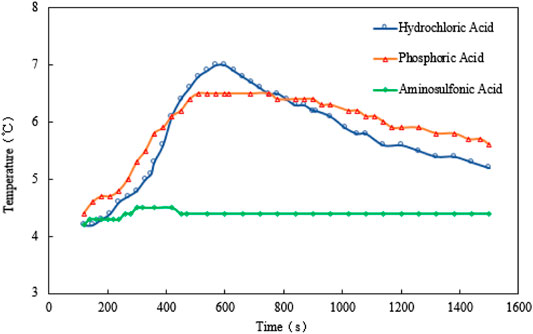

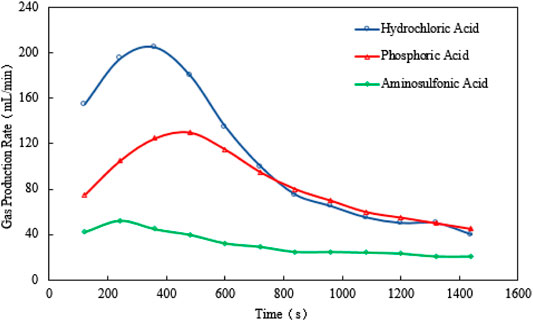

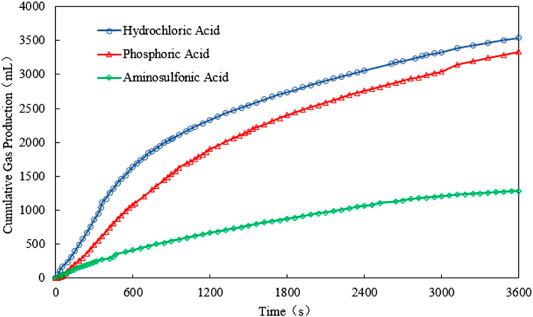

For scenario 1, the temperature, gas production rate, and cumulative gas production are plotted against the time (see Figure 2–4). It is implied from the figures that NaNO2 and NH4Cl can react at 4°C with the three kinds of catalyst, whereas the effects of each kind of catalyst are different. Figure 2 gives the reaction temperature of different kinds of catalysts within 1-h reaction. The peak reaction temperature of using HCl, H₃PO₄, and NH2SO3H as the catalyst is 7°C, 6.5°C, and 4.5°C, respectively. In addition, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the peak gas production rate is 205 ml/min at 320 s, and the cumulative gas production is 3,540 ml by using HCl as the catalyst. The peak gas production rate is 130 ml/min at 480 s, and the cumulative gas production is 3,335 ml using H₃PO₄ as the catalyst. The peak gas production rate is 52.5 ml/min obtained at 240 s, and the cumulative gas production is 1,282 ml using NH2SO3H as the catalyst. By comparing the results of these three catalysts, it is found that the peak heat value reaches at the shortest time for NH2SO3H, while the gas production rate and the cumulative gas production are the lowest. It is supposed that when the solid acid dissolves in the water, H+ slowly ionizes, resulting in mild reaction and hence long reaction time; however, such a long reaction time is not favorable as it will cause excessive heat loss. In the end, HCl is selected as the optimal catalyst due to its better performance in heat and gas production within a reasonable reaction time at low temperatures.

3.2 Effect of Catalyst Concentrations

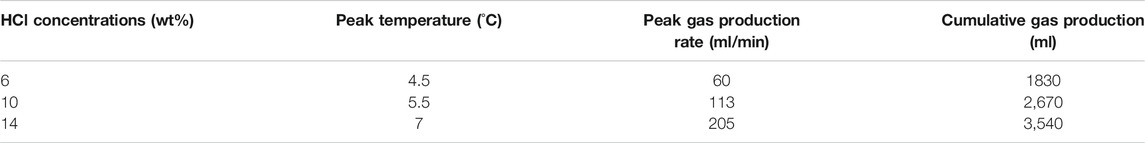

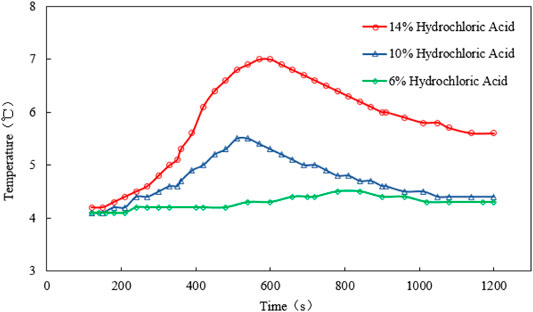

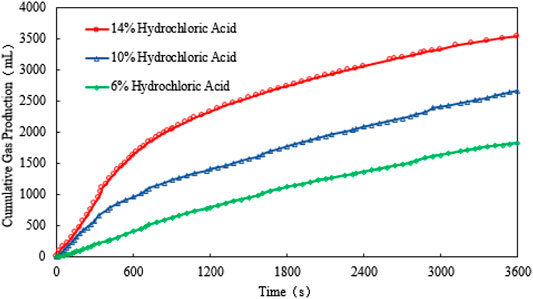

In scenario 2, the reactions were performed at a concentration of 5 mol/L of NaNO2 or NH4Cl with the HCl catalyst at the concentrations of 6, 10, and 14 wt%. To compare the resultant temperature, gas production rate, and cumulative gas production profiles, an equal volume of the catalyst solutions was injected in the three cases. The experimental results are shown in Table 3.

For scenario 2, the temperature, gas production rate, and cumulative gas production are plotted against the time (see Figures 5, 6, and 7). It is observed that the peak temperature, gas production rate, and the cumulative gas production increase with the increase in the catalyst concentration. It should be noted that the concentration of H+in the solution cannot be too high because H+ will react with NO2- to form unstable nitrite, which is easy to decompose into toxic NO and NO2 gases. During the experiment, it was found that when the catalyst concentration exceeds 14% or the H+ concentration of the reaction system is larger than 0.132 mol/L (pH value is less than 1), a reddish-brown irritant gas will be produced. Therefore, 14% is the optimum HCl concentration when being used as the catalyst.

3.3 Effect of Reactant Concentrations

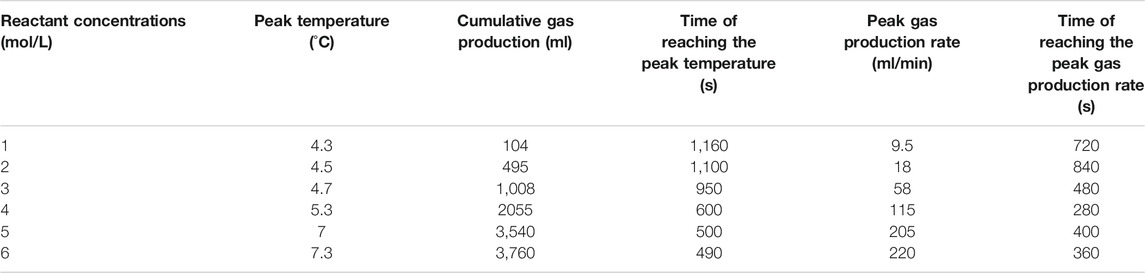

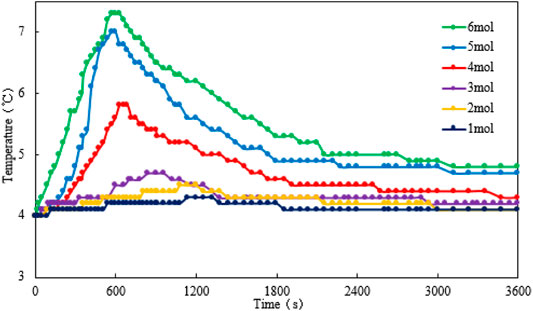

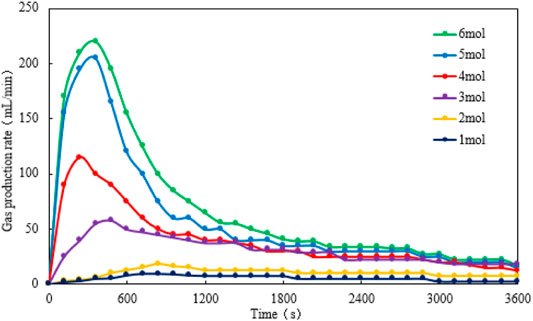

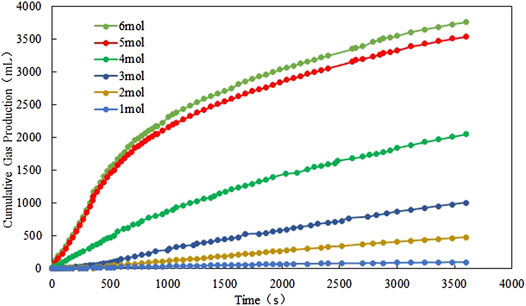

In scenario 3, the reactions were performed at NaNO2 and NH4Cl concentrations of 1∼6 mol/L at an HCl concentration of 14 wt%. To compare the temperature, gas production rate, and cumulative gas production profiles, an equal volume of catalyst solutions was injected in the six cases. The experimental results are shown in Table 4.

For scenario 3, the temperature, gas production rate, and cumulative gas production are plotted against the time (see Figures 8–10). It is implied from the figure that NaNO2 and NH4Cl can react at 4°C with the presence of HCl catalyst. Figure 8 shows the reaction temperature changes at different concentrations of NaNO2 and NH4Cl within 1 h. The temperature is observed to increase with the increase of reactant concentrations. The peak temperature reaches after 600 s, and additionally, the higher the concentration of the reactants, the faster the peak temperature reaches. Moreover, although the temperature profile is the highest when the reaction concentration is 6 mol/L, the temperature profile at the reactant concentration of 5 mol/L is close to it.

In Figures 9, 10 it is implied that the gas production rate or the cumulative gas production increases when the reactant concentration increases from 1 mol/L to 6 mol/L; however, when the concentration of the reactants reaches 5 mol/L, the growth rate slows down. Again, the gas production rate and the cumulative gas production profiles of 5 mol/L reactants are close to those profiles of 6 mol/L reactants. On the other hand, when the concentration of the reactants is larger than 3 mol/L, the gas production rate peak is watched before 600 s, whereas the temperature peak is observed after 600 s. The difference in these two peak times is probably due to the time delay caused by the heat exchange between the cold fluid and hot fluid in the reactor.

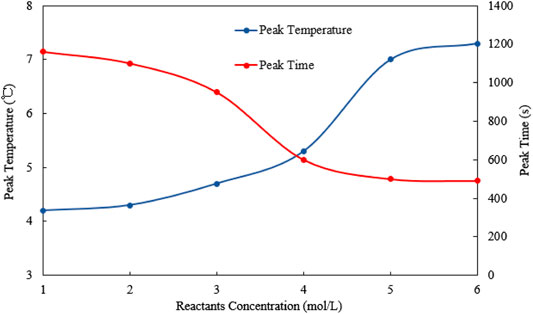

Peak temperature and peak time are plotted against the concentration of the reactants (see Figure 11). It is obvious that with the increase of the reactant concentration, the peak temperature increases gradually. When the concentration of the reactants reaches 5 mol/L, the peak temperature can reach more than 7°C. When the concentration of the reactants reaches 6 mol/L, although the peak temperature still increases, the upward trend slows down. With the increase of the reactant concentration, the time to reach the peak temperature gradually decreases. When the concentration of the reactants reaches 5 mol/L, the downward trend of the peak time slows down, indicating that once the concentration of the reactants is greater than 5 mol/L, the heat generation rate becomes similar.

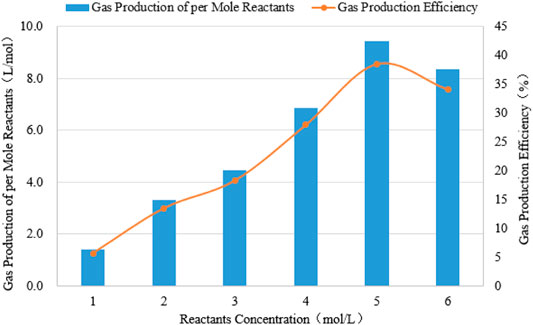

Gas production of per mole reactant and gas production efficiency are plotted against the concentration of the reactants in Figure 12. Here, the gas production efficiency is defined as the ratio of the actual gas production volume to the theoretical gas production volume wherein the theoretical gas production volume is the gas volume obtained when all reactants are converted into products based on the principle of material conservation (Wang et al., 2020). It was implied that the gas production efficiency increases when the reactant concentration increases from 1 mol/L to 5 mol/L, whereas when the concentration of the reactants further increases, it exerts a negative effect on the gas production efficiency, as shown in Figure 12. The highest incremental gas production efficiency can be obtained when 5 mol/L reactants are used. Whereas further increasing the concentration of the reactants, will reduce the incremental gas production efficiency, and the gas production of reactants per mole also decreases, which could be due to the occurrence of side reactions under high concentration conditions. In conclusion, 5 mol/L is the concentration of the optimum reactants.

FIGURE 12. Relationships of the reactant concentration with gas production of per mole reactants and with gas production efficiency.

4 Discussion

Hydrate-based technologies are all built on the simple rationale that hydrate formation and dissociation can induce a reversible phase change in water through pressure and temperature manipulations (Dong et al., 2021). The thermochemical reaction system of NaNO2 and NH4Cl has good heat generation and gas production performance. Theoretically, the reaction of NaNO2 and NH4Cl can release 333 kJ heat per mole (Wang et al., 2020). In this study, when the volume of NaNO2 and NH4Cl solution is 75 ml, respectively, and the concentration of these two reactants is 5 mol/L, hence the amount of NaNO2 and NH4Cl is 0.375 mol, respectively. Assuming that the reactants can react completely, they will release 125 kJ heat and produce 8,400 ml N2. The experimental results show that 0.375 mol NaNO2 and NH4Cl produce 3,540 ml N2 within 1 h at 4°C and 14 wt% catalyst concentrations. This calculation suggests that the reaction degree of the thermochemical reaction system with the optimal formula is 42%, and the actual heat released by the reaction is 52.56 kJ. The decomposition latent heat of NGHs is 52.0–54.5 kJ/mol (Rydzy Marisa et al., 2007). Therefore, the heat released by 0.375 mol NaNO2 and NH4Cl can decompose 0.96∼1.01 mol NGHs at the low temperature of 4 C. From the perspective of thermal decomposition, the thermochemical reaction system in this study is feasible in exploiting the of NGH reservoir. Moreover, a novel concept of injecting air or gaseous N2 into NGHs has been proposed recently (Panter et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2017b; Okwananke et al., 2018). As N2 is injected at the gaseous state, it can readily be dispersed in plugged pipelines or NGH-saturated layers with high permeability. Haneda et al. observed that the NGHs dissociated in the sediment were closely examined for the gas production from the NGHs by continuously injecting the N2 gas (Haneda et al., 2009). Panter et al. also investigated the NGH dissociation behavior inside a blocked pipeline during N2 gas injection and they found that the continuous injection of gaseous N2 as a thermodynamic inhibitor into structure I/structure II hydrates resulted in NGH crush through channel formation, unlike the radial dissociation observed in the depressurization method (Panter et al., 2011). The experimental results indicated the synthesis effects of N2 as both an inhibitor to dissociate the NGHs and an external medium to replace the CH4 molecules in the NGH cages (Mok et al., 2021). The above discussion, thus, shows that the thermochemical reaction system in this study is also feasible in the exploitation of the NGHs from the perspective of nitrogen inhibition and replacement. Further studies are therefore needed to determine the NGHs’ recovery efficiency of the optimal formulation system by experiments based on the mass-transfer theory of hydrate formation and decomposition (Liang et al., 2022).

5 Conclusion

This study investigated the heat generation and gas production performance of the thermochemical reaction system (NaNO2 and NH4Cl) under a low temperature condition (4°C) of real marine NGH reservoirs. It was found that the thermochemical reaction system can react at low temperature with the presence of acid as the catalyst, and it can release heat and produce nitrogen. By comparing the reaction rates of three acid catalysts, the results indicated that HCl was the best acid catalyst for the thermochemical reaction system in this study. In addition, with the increase of HCl concentration, the produced heat and gas by the thermochemical reaction system increased. However, when the catalyst concentration exceeded 14 wt%, a reddish-brown irritant gas was produced during the experiment at the experimental temperature of 4°C; hence 14 wt% HCl was the optimal concentration for the thermochemical reaction at 4°C in this study in considering the application security. The impacts of reactant concentrations were also analyzed by this study. An increase in the reactant concentration could assist the gas production efficiency from 6 to 42%, after which it had a negative effect on the gas production efficiency. In conclusion, an optimal formula of the thermochemical reaction system was 5 mol/L NaNO2 or NH4Cl as reactants and 14 wt% HCl as the catalyst.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

YW and ZS conceived the study; YW, ZS, QL, XL, and YG contributed to methodology; ZS, QL, XL, and YG carried out the investigation; YW, ZS, QL, XL, and YG were responsible for validation; YW, ZS, QL, XL, and YG wrote the original draft; YW, ZS, QL, XL, and YG reviewed and edited the draft; YW, ZS, QL, XL, and YG were responsible for visualization; QL contributed to project administration; QL, XL, and YG helped with the funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Open Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Natural Gas Hydrates (Grant No. 2020-YXKJ-014), and the Guiding Innovation Fund of Northeast Petroleum University (Grant No. 2021YDL-28).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Chen, L., Merey, S., Pecher, I., Okajima, J., Komiya, A., Diaz-Naveas, J., et al. (2020). A Review Analysis of Gas Hydrate Tests: Engineering Progress and Policy Trend. Environ. Geotechnics, 1–17. doi:10.1680/jenge.19.00208

Choi, W., Lee, Y., Mok, J., and Seo, Y. (2020). Influence of Feed Gas Composition on Structural Transformation and Guest Exchange Behaviors in sH Hydrate - Flue Gas Replacement for Energy Recovery and CO2 Sequestration. Energy 207, 118299. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.118299

Choi, W., Mok, J., Lee, Y., Lee, J., and Seo, Y. (2021). Optimal Driving Force for the Dissociation of CH4 Hydrates in Hydrate-Bearing Sediments Using Depressurization. Energy 223, 120047. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.120047

Chong, Z. R., Yang, S. H. B., Babu, P., Linga, P., and Li, X.-S. (2016). Review of Natural Gas Hydrates as an Energy Resource: Prospects and Challenges. Appl. Energ. 162, 1633–1652. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.12.061

Natural Gas Hydrates in Flow Assurance (2010). Burlington: Gulf Professional Publishing: 757 Gulf Professional Publishing.

Dong, H., Wang, J., Xie, Z., Wang, B., Zhang, L., and Shi, Q. (2021). Potential Applications Based on the Formation and Dissociation of Gas Hydrates. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 143. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.110928

Gupta, A., and Aggarwal, A. (2014). “Gas Hydrates Extraction by Swapping- Depressurization Method,” in Proceedings of the Annual Offshore Thchnology Conference, Kuala.

Haneda, H., Sakamoto, Y., Kawamura, T., Miyazaki, K., Tenma, N., and Komai, T. (2009). Research on Productivity Evaluation of Methane Hydrate by Nitrogen Injection Method. Jpn. Assoc. Petrol. Technol. doi:10.3720/japt.74.325

Khlebnikov, V. N., Gushchin, Pa., and Antonov, S. V. (2017). Simultaneous Injection of Thermodynamic Inhibitors and CO2 to Exploit Natural Gas Hydrate: An Experimental Study. Nat. Gas Ind. 37, 40–46. doi:10.3787/j.issn.1000-0976.2017.12.006

Kph, D. Y., Kang, H., Kim, D. O., Park, J., Cha, M., and Lee, H. (2012). Recovery of Methane from Gas Hydrates Intercalated within Natural Sediments Using CO2 and a CO2/N2 Gas Mixture. Chemsuschem 5, 1443–1448. doi:10.1002/cssc.201100644

Li, G., Li, X.-S., Li, B., and Wang, Y. (2014). Methane Hydrate Dissociation Using Inverted Five-Spot Water Flooding Method in Cubic Hydrate Simulator. Energy 64, 298–306. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2013.10.015

Li, G., Moridis, G. J., Zhang, K., and Li, X.-S. (2010). Evaluation of Gas Production Potential from marine Gas Hydrate Deposits in Shenhu Area of South China Sea. Energy Fuels 24, 6018–6033. doi:10.1021/ef100930m

Li, L., Lei, X., Zhang, X., and Sha, Z. (2013). Gas Hydrate and Associated Free Gas in the Dongsha Area of Northern South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geology. 39, 92–101. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2012.09.007

Liang, H., Guan, D, Shi, K., Yang, L., Zhang, L., Zhao, J., et al. (2022). Characterizing Mass-Transfer Mechanism during Gas Hydrate Formation from Water Droplets. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 626. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.132626

Liu, Y., Hou, J., Chen, Z., Bai, Y., Su, H., Zhao, E., et al. (2021). Enhancing Hot Water Flooding in Hydrate Bearing Layers through a Novel Staged Production Method. Energy 217, 119319. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.119319

Mahmoud, M., Alade, O. S., Hamdy, M., Patil, S., and Mokheimer, E. M. A. (2019). In Situ steam and Nitrogen Gas Generation by Thermochemical Fluid Injection: A New Approach for Heavy Oil Recovery. Energ. Convers. Manage. 202, 112203. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112203

Minagawa, H. (2015). “Depressurization and Electrical Heating of Hydrate Sediment for Gas Production,” in Eleventh Ocean Mining and Gas Hydrates Symposium (Kona, Hawaii: Kona: International Society of Offshore and Polar Engineers), 82–88.

Mok, J., Choi, W., and Seo, Y. (2021). The Dual-Functional Roles of N2 Gas for the Exploitation of Natural Gas Hydrates: An Inhibitor for Dissociation and an External Guest for Replacement. Energy 232, 124054. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.121054

Nguyen, D. A., Iwaniw, M. A., and Fogler, H. S. (2003). Kinetics and Mechanism of the Reaction between Ammonium and Nitrite Ions: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. Chem. Eng. Sci. 58 (19), 4351–4362. doi:10.1016/s0009-2509(03)00317-8

Okwananke, A., Yang, J., Tohidi, B., Chuvilin, E., Istomin, V., Bukhanov, B., et al. (2018). Enhanced Depressurisation for Methane Recovery from Gas Hydrate Reservoirs by Injection of Compressed Air and Nitrogen. The J. Chem. Thermodynamics 117, 138–146. doi:10.1016/j.jct.2017.09.028

Panter, J. L., Ballard, A. L., Sum, A. K., Sloan, E. D., and Koh, C. A. (2011). Hydrate Plug Dissociation via Nitrogen Purge: Experiments and Modeling. Energy Fuel 25, 572–2578. doi:10.1021/ef200196z

Qian, C., Wang, Y., Yang, Z., Qu, Z., Ding, M., Chen, W., et al. (2019). A Novel In Situ N2 Generation System Assisted by Authigenic Acid for Formation Energy Enhancement in an Oilfield. RSC Adv. 9, 39914–39923. doi:10.1039/c9ra07934c

Rydzy, M. B., Schicks, J. M., Rudolf, N., and Erzinger, J. (2007). Dissociation Enthalpies of Synthesized Multicomponent Gas Hydrates With Respect to the Guest Composition and Cage Occupancy. J. Phys. Chem. B 111(32), 9539–9545. doi:10.1021/jp0712755

Song, S., Shi, B., Yu, W., Ding, L., Chen, Y., Yu, Y., et al. (2019). A New Methane Hydrate Decomposition Model Considering Intrinsic Kinetics and Mass Transfer. Chem. Eng. J. 361, 1264–1284. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2018.12.143

Song, Y., Cheng, C., Zhao, J., Zhu, Z., Liu, W., and Yang, M. (2015). Evaluation of Gas Production from Methane Hydrates Using Depressurization, thermal Stimulation and Combined Methods. Appl. Energ. 145, 265e77. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.02.040

Sun, Y., Jiang, S., Li, S., Wang, X., and Peng, S. (2021). Hydrate Formation from clay Bound Water for CO2 Storage. Chem. Eng. J. 406, 126872. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.126872

Sun, Y., Wang, C., and Sun, J. (2021). Study on Autogenous Heat Technology of Offshore Oilfield: Experiment Research, Process Design, and Application. London: Geofluids.

Sun, Y., Zhang, G., Li, S., and Jiang, S. (2019). CO2/N2 Injection into CH4 + C3H8 Hydrates for Gas Recovery and CO2 Sequestration. Chem. Eng. J. 375, 121973. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.121973

Teng, Y., and Zhang, D. (2018). Long-term Viability of Carbon Sequestration in Deep-Sea Sediments. Sci. Adv. 4 (7), eaao6588. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao6588

Wang, X.-H., Sun, C.-Y., Chen, G.-J., He, Y.-N., Sun, Y.-F., Wang, Y.-F., et al. (2015). Influence of Gas Sweep on Methane Recovery from Hydrate-Bearing Sediments. Chem. Eng. Sci. 134, 727–736. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2015.05.043

Wang, Y. F., Qian, C., Ji, Z. J., Yan, F., Yang, Z., Ding, M. C., et al. (2020). Reaction Characteristics of Sodium Nitrite and Ammonium Chloride System. ACTA PETROLEI SINICA 41, 226–234. doi:10.7623/syxb202002008

Wu, W. G., Xiong, Y., Wang, J., and Chen, D. J. (2007). A Self-Foaming Solution for Bottom Liquid Removal in Gas Wells. Oilfield Chem., 106–108. doi:10.19346/j.cnki.1000-4092.2007.02.004

Xu, T., Zhang, Z. B., Li, S. D., Li, X., and Lu, C. (2021). Numerical Evaluation of Gas Hydrate Production Performance of the Depressurization and Backfilling with an In Situ Supplemental Heat Method. ACS omega 6, 2274–12286. doi:10.1021/acsomega.1c01143

Zhang, X., Lu, X., and Li, P. (2018). A Comprehensive Review in Natural Gas Hydraterecovery Methods. Sci. Sin. Phys. Mech. Astron. 49 (3), 034604. doi:10.1360/SSPMA2018-00212

Yu, X., Wang, J., Liang, J., Li, S., Zeng, X., and Li, W. (2014). Depositional Characteristics and Accumulation Model of Gas Hydrates in Northern South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geology. 56, 74–86. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2014.03.011

Yuan, Q., Sun, C. Y., Yang, X., Ma, P. C., Ma, Z. W., Li, Q. P., et al. (2011). Gas Production from Methane-Hydrate-Bearing Sands by Ethylene Glycol Injection Using a Three-Dimensional Reactor. Energy Fuels 25, 3108–3115. doi:10.1021/ef200510e

Zhang, L., Kuang, Y., Zhang, X., Song, Y., Liu, Y., and Zhao, J. (2017). Analyzing the Process of Gas Production from Methane Hydrate via Nitrogen Injection. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56, 585–7592. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.7b01011

Keywords: NGHs, thermochemical reaction, heat generation, gas production, replacement efficiency

Citation: Wang Y, Sun Z, Li Q, Lv X and Ge Y (2022) A Thermal Chemical Reaction System for Natural Gas Hydrates Exploitation. Front. Energy Res. 9:804498. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2021.804498

Received: 29 October 2021; Accepted: 13 December 2021;

Published: 12 January 2022.

Edited by:

Qi Zhang, China University of Geosciences Wuhan, ChinaReviewed by:

Hongsheng Dong, Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (CAS), ChinaJiaqi Wang, Harbin Engineering University, China

Copyright © 2022 Wang, Sun, Li, Lv and Ge. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhenxin Sun, c3p4OTUxMTE4QDEyNi5jb20=

Yanan Wang1,2

Yanan Wang1,2 Zhenxin Sun

Zhenxin Sun