94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Energy Res., 24 March 2021

Sec. Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2021.634321

Response time is the key index of on-line monitoring system. To improve the response speed of traditional bead thermal conductivity CO2 sensor, this paper proposes to use multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) to improve the performance of gas sensor carrier. Nano-sized γ-Al2O3/CeO2 powder was synthesized by chemical precipitation method under the action of ultrasonic wave. SEM morphology reveals a particle size of 20–50 nm. MWCNTs were hydroxylated and the solution was then prepared by adding a certain amount of dispersant under ultrasonic wave. The composite support of γ- Al2O3/CeO2/MWCNTs was prepared by wet mixing carbon nanotube solution into the above support materials. Using dynamic resistance matching and black component technology, the influence of radiation heat and environmental temperature and humidity is reduced. Results show that the designed thermal conductivity sensor has consistent response and recovery time to different concentrations of CO2, with a T90 response time of 9 s and a T90 recovery time of 13 s, which is faster compared to major commercial Carbon dioxide sensors. The average sensitivity of the sensor is 0.0075 V/10% CO2. Therefore, the high thermal conductivity and pore characteristics of carbon nanotubes can effectively improve the response speed of the thermal conductivity sensor.

A large number of greenhouse gas CO2 emissions aggravate the global warming. Acid rain, haze, and other bad weather caused huge economic losses and serious environmental damage (Hansen and Sato, 2004). Controlling CO2 emission is the fundamental way to deal with climate warming as generally agreed by the international community (Zhang et al., 2008). In industrial production, especially in coal mines, CO2 is often a product of emissions, which is also a source of danger in the production process (there have been many carbon dioxide outburst accidents in the history of coal mining). Therefore, it is necessary to detect and control the CO2 emissions in a distributed, real-time and accurate way (Ghosh et al., 2013; Zaitsev et al., 2017).

Thermal conductivity sensor is a thermal effect sensor that can measure the concentration of gas according to the difference of thermal conductivity of different gases and air (Gardner et al., 2020). Usually, the difference of thermal conductivity is converted into the change of resistance using the Wheatstone circuit. The heat conduction mode usually includes convection, conduction, and radiation that works at about 300°C. Its response mechanism determines that it has the advantages of large detection range, good working stability, and strong reliability. However, it also exhibits the problems of slow response time and low detection accuracy (Wei-Yong et al., 2006). To achieve high precision and fast response detection in a dangerous environment, it is necessary to improve the thermal conductivity and response sensitivity of the sensor.

In recent years, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have been gradually used in the development of thermal conductive gas sensors because of their better thermal properties and pore structure compared to ordinary ceramic carriers (Huang et al., 2019). Researchers at home and abroad have studied gas sensors modified by carbon nanotubes (Zhang, 2012). The gas sensor fabricated by Guo et al. (2006) was coated with a small amount of MWCNTs between interdigital gold electrodes based on Al2O3 and has good gas sensing response to toluene at room temperature. Tang et al. (2020) used single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNT) to fabricate NH3 sensors, obtaining a superior sensitivity of 2.44% ΔR/R per ppmv NH3, which is more than 60 times higher than intrinsic SWNT-based sensors. Bin Shen (Shen et al., 2018) and others studied the pore forming technology of MWCNTs supported on aligned nanotubes and designed and fabricated a kind of hot-wire-coated ceramic powder thermal conductivity sensor for methane detection with a response recovery time of 8 s and 16 s (Xibo et al., 2013).

In this paper, MWCNTs are used to improve the blind hole carrier structure of traditional bead like thermal conductivity sensor, open up more gas transmission channels, and effectively improve the permeability of the sensitive material “ceramic bead” (Wu and Lin, 2006; Torres-Torres et al., 2013). The fabrication method and key technology of this kind of sensor are presented. The performance of the sensor is measured and the possible mechanism is discussed. Results indicate that the response and recovery time of the sensor by loading MWCNTs modification into nano-Al2O3 powders has been greatly shortened. The study has an important influence on the improvement of real-time detection technology of high concentration CO2 in coal mines (Qin et al., 2011).

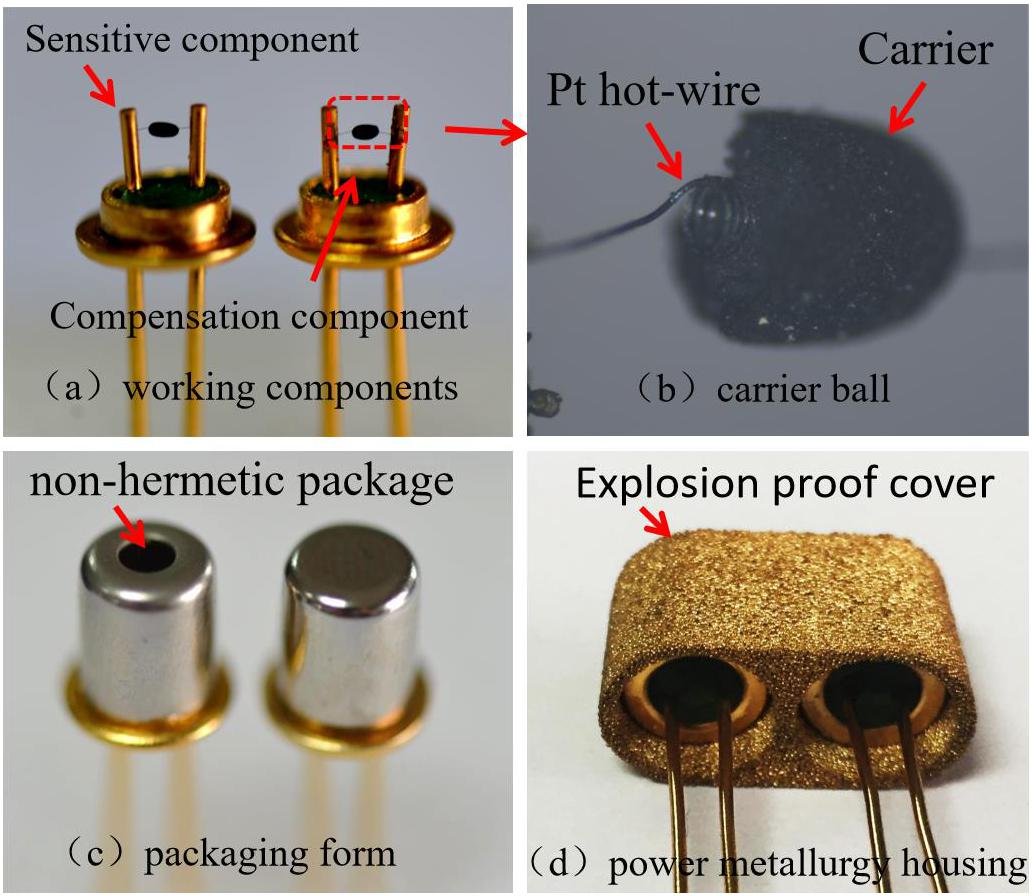

A thermal conductivity gas sensor consists of a detecting element and a compensating element, which are a pair of working components (Figure 1A) consisting of a platinum hot-wire resistor and carrier (Figure 1B). These two components are separately assembled into two standard tubes. One is non-sealing packaging (Figure 1C), and the other is sealing packaging, which is used for the interference of humidity and the compensation of ambient temperature of sensitive component. A thermal conductivity sensor is then made by assembling the two components into the powder metallurgy housing (Figure 1D) to realize explosion-proof safety designing.

Figure 1. Sensor assembly package. Label (a) shows working components, label (b) shows carrier ball, label (c) shows packaging form, label (d) shows powder metallurgy housing.

The manufacturing methods of the sensitive element and the compensation element of the thermal conductivity sensor are similar, but the packaging form is different, which plays a role of differential compensation (Xue et al., 2013). The key factors that restrict the performance of the sensor are mainly the composition of the sensor carrier, microstructure, types and distribution forms of catalysts. The sensor’s main manufacturing process consists of 10 steps such as carrier produced, carrier modification (mixed carbon nanotube and catalyst loading), element coil winding, coating carrier on the coil, element sintering, element blackening, element matching and element packaging, sensors aging and performance testing and so on. The specific process is shown in Figure 2.

γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles have the advantage of a higher specific surface area. After being mixed with MWCNT, a large number of micro-nanopores will be formed (Zhang et al., 2018). Some of the through holes are conducive to the production of sensitive units for thermal conductivity sensors (Wu et al., 2013).

In this paper, nanoscale γ - Al2O3 ceramic ultrafine powder carrier materials were prepared by chemical precipitation method (Saha et al., 2005). Under the continuous action of ultrasonic wave, the solution composed of 0.02 mol formic acid, 5.4 g water and 7 ml isopropanol was slowly dropped into the mixture of 20.4 g isopropyl aluminium and 200 ml toluene. After completing the operation, the mechanical stirrer is started and the solution is heated to 50∼60°C. The reaction is then maintained for 1 h and then the semitransparent gel is obtained. The products were filtered, dried at 60°C for 12 h and dried again at 120°C for 1 h. The loose dry gel powder was then obtained. The nano-Al2O3 powder can be obtained by calcining the xerogel powder for 2 h at 700∼800°C. It should be noted that the micro droplet adding mode under ultrasonic wave and calcination temperature are the key to the formation of nano-sized γ- Al2O3 powder.

Since MWCNTs are difficult to dissolve in water, hydroxylated MWCNTs (SSA > 490m2/g, Purity > 95wt%, Chengdu Organic Chemicals Co. Ltd) was selected in the experiment. SEM characterization showed that the MWCNTs had an outer diameter of 8 nm and a length of 5–30 um. To improve the dispersion uniformity of MWCNTs in Al2O3 powder, it is necessary to prepare MWCNTs in an aqueous solution by adding certain amount of dispersant under the action of ultrasonic wave.

To improve the thermal stability of the carrier, the target composite carrier also needs to be modified by adding 5% w/W Nano-CeO2 powder (30∼50 nm, 99.99% purity, Macklin). Finally, the material was added into γ-Al2O3/CeO2 powder at the ratio of 5% w/W to form nano-γ-Al2O3/CeO2/MWCNTs composite catalyst support.

Due to the high specific surface area and surface activity of nano-γ-Al2O3, the carrier made of it has strong adsorption to polar molecules (including water molecules in the air) (Liu et al., 2011), but the desorption effect becomes poor. At the same time, the grayscale of ceramic fired by the carrier γ-Al2O3/CeO2/MWCNTs is low, which causes the heat radiation effect to be aggravated, thereby affecting the detection of thermal convection effect.

In this paper, Pd and Pt particles are formed by impregnating pure chlorinated palladium acid solution (H2PtCl6⋅6H2O and H2PdCl6⋅6H2O analytically pure, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd), which consequently electrothermally decompose the Pd and Pt particles to make the carrier change from gray to black. The heat dissipation efficiency of the carrier can be effectively reduced when the sensor is working. To reduce the catalytic effect of nano-Pd/Pt particles, lead nitrate solution was impregnated on the surface of black Pd/Pt particles and decomposed at high temperature to form desensitized lead monoxide. Finally, the sensitivity and compensation elements of thermal conductivity sensor without catalytic effect were formed.

Three key steps must be completed to solve the problem of carbon nanotubes easily burning at high temperatures.

The first step of electrified sintering is sintering the carrier powder size at high temperature to combine the grains and make micro/nano-holes, so that the carrier has a certain mechanical strength and a stable high specific surface area. The sensitive coil of the coated carrier was loaded with DC voltage under the protection of high-purity nitrogen and around 550°C, and the sintering current of 150 mA was maintained for 60 min.

Second, under the protection of high-purity nitrogen, a sintering current of 140 mA is passed through at about 500°C, and the current is maintained for 30 min to thermally decompose the palladium chloride solution impregnated in the carrier. Therefore, the sensitive components and compensation components will turn black.

The third step is in high purity nitrogen protection and under 550°C, through sintering current of 150 mA, decompose the dipping lead nitrate solution black carrier 30 min, due to the thermal decomposition of lead nitrate solution to form the office and PbO, will eliminate the Pt and Pd catalyst carrier. As a result, the sensitive component will only have the thermal conductivity effect during working.

The dynamic test system in Figure 3 consists of the input and output devices (including computer, DC stabilized power supply, and data collector), pure carbon dioxide gas, three-way valve, dynamic test chamber (sensor and sensor base), measuring circuit, interface, and bus. Among them, the dynamic test chamber is the core part of the whole system and the volume can be adjusted by the external piston (similar to the needle cylinder piston). The target gas concentration is controlled by adjusting the volume of the test chamber and the volume ratio of the injected carbon dioxide gas. The sensor base is fixed on the outside of the test chamber, and the sensor can be quickly switched between the target gas and the air using the piston. This structure solves the disadvantage of slow air exchange in the traditional sensor test chamber and eliminates the influence of gas diffusion on the response time of the sensor.

Sensor module is a typical Wheatstone bridge for converting gas concentration to voltage output, as shown in Figure 4. Fixed resistors R1 and R2 (200Ω) are connected to the bridge arm at one end, while the sensing element and compensation element (C, D) are connected at the other end. The two arms are connected to each other using 3.0 V (Vin) constant voltage power supply. The detection circuit can output values in millivolts according to the change of target gas concentration. R3 is a sliding rheostat used to adjust the sensor’s zero output value, which is 2000 Ω.

Zeiss Supra 55 scanning electron microscope was used to observe and measure the morphology of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and its composite carrier materials with the working voltage of 15,000 V. The micro size of the prepared Al2O3 carrier is 20–50 nm, as shown in Figure 5. Carbon nanotubes in Al2O3 carrier are intertwined to form a channel inside the carrier, as shown in Figure 6. The formation of carbon nanotubes is mainly the mixture of sp2-hybridized and sp3-hybridized nanotubes. By the influence of quantum physics, it may produce special electrical properties depending on the network structure and diameter. At the same time, carbon nanotubes are also synthesized into carbon-carbon double bonds, hollow cages and closed topologies, so they have excellent thermal and mechanical properties (Dongmei et al., 2014).

Figure 7 indicates that the carrier mainly consists of carbon nanotubes, Al2O3, and CeO2. The expected components of carbon nanotubes and CeO2 have been modified. The mass ratio of Pt and Pd is 2:1 as shown in the mapping characterization results (Table 1), while carbon nanotubes reached 4.14%.

Figure 8 shows the sensitivities at different working voltages from 1.5 to 3.0 V with 10% CO2. Obviously, the relationship between sensitivity and the working voltage is not linear. With increased working voltage, the sensitivity first presents a rising tendency and then declines from the fitting sensitivity. The sensitivity reaches its maximum at 2.7 V and thus, the working voltage of 2.7 V is used in subsequent tests. It shows that the MWCNTs-modified sensor can work at a lower voltage and has lower power consumption than the commercial sensor operating at 3.0 V voltage.

The response recovery curve of CO2 concentration is determined from 0 to 100% by controlling the CO2 concentration in the test system at ambient temperature of 25°C and humidity of 45% with an interval concentration of 10% and an operating voltage of 2.7 V by three times. Linear fitting of the average output voltage of the sensor and the CO2 concentration is shown in Figure 9 which reveals that the sensor has a good linear relationship (y = 0.464 + 0.754X, R2 = 0.9986) with an average sensitivity of about 0.00754 V/10% CO2. The sensitivity of CO2 with less than 40% concentration is slightly higher than that with more than 40%.

One of the challenges in the application of thermal conductivity gas sensors is the consistency of the response of target gases with different concentrations, which is affected by both the test conditions and the performance of the sensor. In this test, a dynamic gas chamber with volume scale is used to realize the fast switch between the air and the gas to be measured. The ideal result is then obtained. Figure 10 shows that the sensor has a good response and recovery performance for different CO2 concentrations with the same response and recovery characteristics at ten different concentrations. The test results of three times response & recovery time are shown in Figure 11, the T90 response time of the developed sensor is 9 s and the T90 recovery time is 13 s.

Response time is an important index of gas sensor. Generally, the time taken for the output value of the gas sensor to reach 90% of the stable value after contacting the target gas is defined as the sensor response time, which is expressed by T90. The smaller the value is, the faster the response speed is. The response time of the sensor is divided into the diffusion of CO2 gas to the powder metallurgy shell and the direct response time of the sensor to CO2 gas. The gas diffusion time will be affected by the size of this powder metallurgy overlay. It is determined that 400 mesh specification is the best choice for gas test.

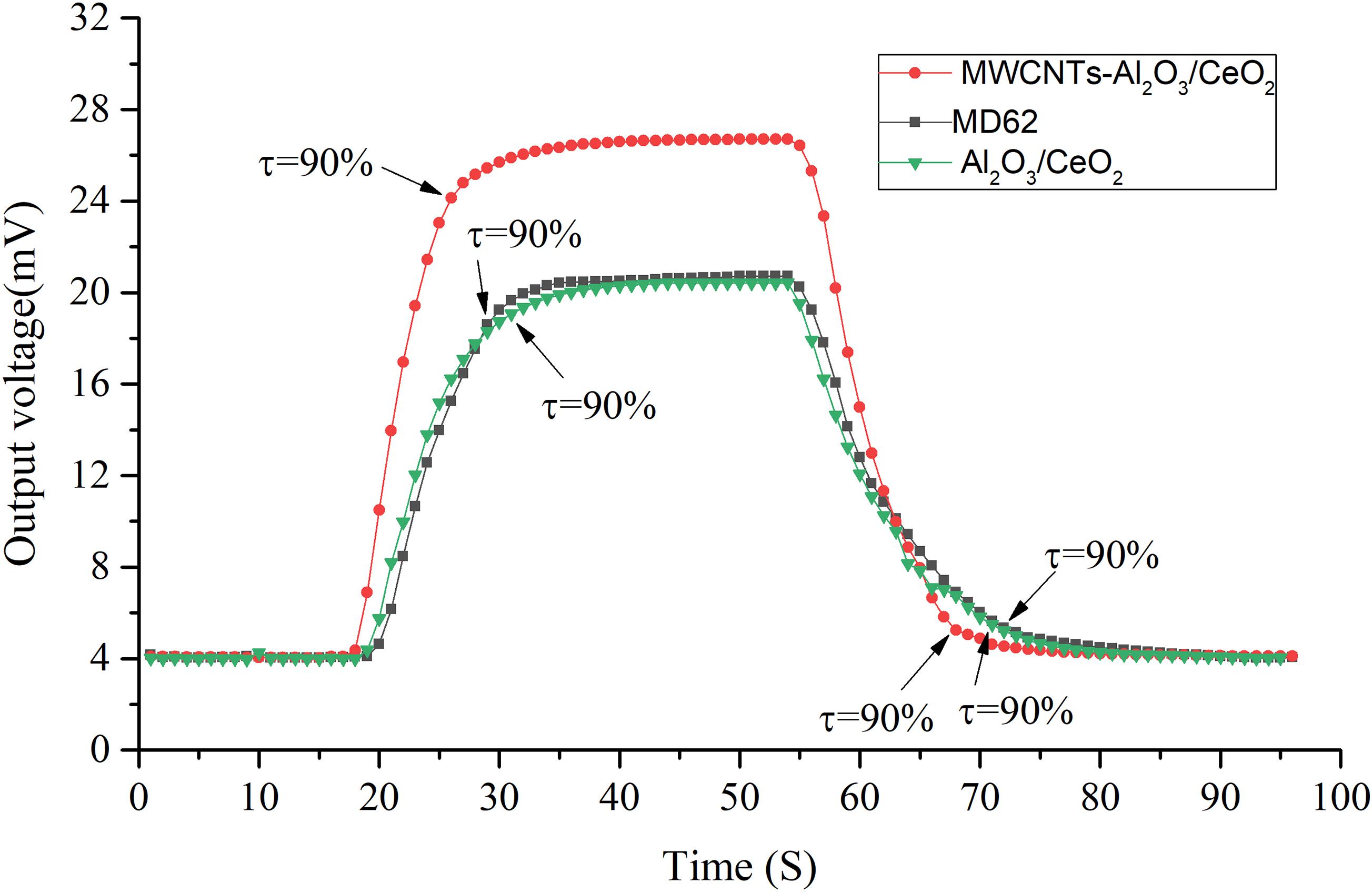

Under the condition of 30% CO2 concentration, the working voltage of the sensor was set as 2.7 V, and the response and recovery curves of three kinds of thermal conductivity sensor of non-MWCNTs modified, MWCNTs modified and MD62 which produced by Winsen (China) company (Winsen, 2018) with sensitivity of 0.0061 V/10% CO2 were tested, as shown in Figure 12. The sensitivity of the modified MWCNTs is much higher compared with the sensor before modification and MD62. The T90 response time of the non-MWCNTs modified sensor is 11 s and the T90 recovery time is 17 s. The T90 response time of the MD62 sensor is 10 s and the T90 recovery time is 18 s. The results show that the developed sensor with T90 response time of 9 s and T90 recovery time of 13 s has better performance. Moreover, the modified carbon nanotubes can greatly improve the thermal conductivity sensor’s response recovery performance.

Figure 12. Response curves of 30% CO2 compared with non-MWCNTs-modified sensor and commercial sensor MD62.

When the target ambient gas changes, making the sensor measurement components quickly achieve a new balance is the key to improve the performance of the thermal conductivity gas sensor. From the response mechanism of the thermal conductivity sensor, the thermal balance ability of the sensing element is the key to affect the response of the sensor, which depends on the thermal conductivity and microstructure of the sensor itself. The traditional way is to reduce the size of the alumina carrier and increase the specific surface area. When the alumina powder is reduced to the nano size (< 50 nm) due to the carrier formation mechanism, a large number of holes are observed in the inner of the alumina carrier. However, a large proportion of these holes are blind holes and the impermeability of which will lead to gas transmission barrier, resulting in insufficient air exchange and consequently slows down the sensor response speed and easily causes performance drift.

The electrical properties of the sensor carrier can be enhanced through the improvement of carbon nanotubes. First, carbon nanotubes improve the transport efficiency of the measured gas by improving the microchannel of the carrier, as shown in Figure 13. The inner diameter of MWCNTs is 2–5 nm, which allows CO2 gas to diffuse and transport in MWCNTs.MWCNTs and alumina powder are cemented together, which play a role of secondary pore formation and provide a variety of channels for the carrier, so that the original surface expansion heat exchange can be extended to the internal exchange. Second, the current length of carbon nanotubes is 5–30 um and its thermal conductivity can reach up to 1,000 W/m⋅K, which is 100 times that of Al2O3, thus effectively improving the thermal conductivity of the composite carrier material (Shanni et al., 2020). In addition, because of the large area of carbon nanotubes, it can also accelerate the heat exchange efficiency of the measured gas on the sensitive carrier, greatly improving the response time and stability of the sensor.

(1) The γ-Al2O3/CeO2 carrier material modified by carbon nanotubes is crucial to the sensitivity of the thermal conductivity sensor. Heat treatment can change its crystal form, make it have greater activity and maintain good physical and chemical properties, inhibit carrier agglomeration, and improve the stability of the sensor. Under air conditions, the CO2 test showed that the average sensitivity of the sensor was 0.0075 V/10% CO2 and exhibited good linearity.

(2) For different concentrations of CO2, the sensor exhibited good response performance and recovery performance, which are similar at different concentrations. The T90 response time and T90 recovery time of the sensor are 9 s and 13 s, respectively, which are better compared to non-MWCNTs-improved sensor and the same type of commercial sensor.

(3) Multi-walled carbon nanotubes exhibited thermal conductivity. The modified composite carrier is conducive to the full heat transfer of the measured gas in the hole and improves the heat transfer efficiency of the measured gas on the carrier, which can greatly improve the thermal conductivity of the carrier and enable the sensor to exhibit fast response characteristics.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

BS: conceptualization, investigation, writing–review, project administration, and funding acquisition. XWL: methodology and supervision. FZ and XLL: software. BS and LJ: validation. XQ: resources. FZ and XS: data curation. BS and XLL: writing–original draft preparation and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC0810500), National Natural Science Foundation of China (52074111), Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (YQ2020E034), and Universities Youth Innovation Talent Training Program project of Heilongjiang province (UNPYSCT-2018095).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank Hongquan Zhang and his team from Harbin Engineering University for their provided long-term all kinds of gas and technical guidance. They would also like to thank the reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments.

Dongmei, Z., Zhenwei, L., Lingdi, L., Yanhong, Z., Decai, R., and Jian, L. (2014). Progress of preparation and application of graphene/carbon nanotube composite materials. Acta Chimi. Sin. 72, 185–200. doi: 10.6023/A13080857

Gardner, E. L. W., Luca, A. D., Vincent, T., Jones, R. G., Gardner, J. W., and Udrea, F. (2020). Thermal Conductivity Sensor with Isolating Membrane Holes. 2019 IEEE SENSORS. New York, NY: IEEE.

Ghosh, R., Midya, A., Santra, S., Ray, S. K., and Guha, P. K. (2013). Chemically reduced graphene oxide for ammonia detection at room temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 7599–7603. doi: 10.1021/am4019109

Guo, M., Pan, M., Chen, J., Mi, Y., and Chen, Y. (2006). Palladium modified multi-walled carbon nanotubes for benzene detection at room temperature. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 34, 1755–1758. doi: 10.1016/S1872-2040(07)60020-6

Hansen, J., and Sato, M. (2004). Greenhouse gas growth rates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 16109–16114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406982101

Huang, J. R., Yang, X. X., Her, S. C., and Liang, Y. M. (2019). Carbon nanotube/graphene nanoplatelet hybrid film as a flexible multifunctional sensor. Sensors 19:317. doi: 10.3390/s19020317

Liu, F., Abed, M. R. M., and Li, K. (2011). Preparation and characterization of poly(vinylidene fluoride) (pvdf) based ultrafiltration membranes using nano γ-al2o3. J. Memb. Sci. 366, 97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2010.09.044

Qin, X., Fu, M., and Shen, B. (2011). “Coal mine gas wireless monitoring system based on WSNs[C],” in Proceedings of the 2011 Second International Conference on Digital Manufacturing & Automation (Zhangjiajie: IEEE), 309–312. doi: 10.1109/ICDMA.2011.82

Saha, D., Mistry, K. K., Giri, R., Guha, A., and Sensgupta, K. (2005). Dependence of moisture absorption property on sol–gel process of transparent nano-structured γ-al2o3 ceramics. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 109, 363–366. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2005.01.002

Shanni, W. U., Yuan, Z., Hong, J., Feng, W., and Chunrong, X. (2020). Construction of w/al2o3 functional nano-multilayers with low thermal conductivity and superior mechanical properties. Mater. Rep. 34, 2023–2028.

Shen, B., Zhang, H., Liu, X., Cao, S., and Yang, P. (2018). Fabrication and characterizations of catalytic methane sensor based on microelectromechanical systems technology. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 13, 1816–1822. doi: 10.1166/jno.2018.2435

Tang, S., Chen, W., Zhang, H., Song, Z., and Wang, Y. (2020). The functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes gas sensor with pd nanoparticles for hydrogen detection in the high-voltage transformers. Front. Chem. 8:174. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00174

Torres-Torres, C., Peréa-López, N., Martínez-Gutiérrez, H., Trejo-Valdez, M., Ortíz-López, J., and Terrones, M. (2013). Optoelectronic modulation by multi-wall carbon nanotubes. Nanotechnology 24:045201. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/24/4/045201

Wei-Yong, H., Min-Ming, T., and Zi-Hui, R. (2006). New method of gas concentration detection using thermal conductivity sensor. Chin. J. Sens. Actuators 19, 973–975. doi: 10.1016/S1005-8885(07)60041-7

Winsen (2018). MD62 Thermal Gas Sensor. [EB/OL]. Available online at: http://www.winsensor.com/redao/MD62rdCO2cgq_41.html (accessed May 20, 2018).

Wu, T. M., and Lin, Y. W. (2006). Doped polyaniline/multi-walled carbon nanotube composites: preparation, characterization and properties. Polymer 47, 3576–3582. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2006.03.060

Xibo, D., Xiaoyan, G., Yuechao, C., Xue, S., and Zhaoxia, L. (2013). Study on thermal conductivity methane sensor constant temperature detection method. Telkomnika 11:725. doi: 10.12928/TELKOMNIKA.v11i4.1168

Xue, S., Xibo, D., Yuechao, C., Gen, H., and Long, B. (2013). “Temperature drift and compensation techniques for the thermal conductivity gas sensor,” in Proceedings of the 2013 8th International Forum on Strategic Technology (IFOST) (New York, NY: IEEE).

Wu, Y., Ma, J., Li, M., and Hu, F. (2013). Synthesis of gamma-al2o3 with high surface area and large pore volume by; reverse precipitation-azeotropic distillation method. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 29, 206–209. doi: 10.1007/s40242-013-2207-7

Zaitsev, B. D., Teplykh, A. A., Borodina, I. A., Kuznetsova, I. E., and Verona, E. (2017). Gasoline sensor based on piezoelectric lateral electric field excited resonator. Ultrasonics 80:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2017.05.003

Zhang, H., Shen, B., Hu, W., and Liu, X. (2018). Research on a fast-response thermal conductivity sensor based on carbon nanotube modification. Sensors 18, 2191–2120. doi: 10.3390/s18072191

Zhang, Q. (2012). Rescuing the Earth: Legal Approaches to Climate Change Adaptation: Safeguarding the Interests of Victims. Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press.

Keywords: gas sensor, thermal conductivity, CO2, multi-walled carbon nanotubes, fast-response, nano γ-Al2O3

Citation: Shen B, Zhang F, Jiang L, Liu X, Song X, Qin X and Li X (2021) Improved Sensing Properties of Thermal Conductivity-Type CO2 Gas Sensors by Loading Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Into Nano-Al2O3 Powders. Front. Energy Res. 9:634321. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2021.634321

Received: 27 November 2020; Accepted: 01 March 2021;

Published: 24 March 2021.

Edited by:

Dongliang Zhong, Chongqing University, ChinaReviewed by:

Chungang Xu, Guangzhou Institute of Energy Conversion (CAS), ChinaCopyright © 2021 Shen, Zhang, Jiang, Liu, Song, Qin and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinlei Liu, THhsMjAyMEAxNjMuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.