- Department of Chemical Engineering, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, United States

Wastewater resource recovery facilities are major energy consumers in a community, as well as major contributors for greenhouse gas emission. Although anaerobic digestion is widely employed in wastewater treatment to reduce the amount of solid organic waste and the sludge produced, the use of the produced biogas is mostly limited to heating and electricity generation, while the nutrient rich digestate still requires further treatment. In this work, we propose a waste-to-value platform based on a microalgae-methanotroph coculture, which can convert anaerobic digestion-generated biogas into value-added products, while simultaneously removing nutrients from digestate. The platform takes advantage of the synergistic interactions within a microalgae-methanotroph coculture to achieve significantly improved productivity of microbial biomass and enhanced nutrient recovery performance. Using Chlorella sorokiniana–Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) as the model coculture, we demonstrate that the coculture offers a highly promising platform for waste-to-value technologies, which can efficiently recover energy (from CH4) and carbon (from both CH4 and CO2) to produce microbial biomass, while removing nutrients from wastewater to produce treated clean water. Compared to microalgae monoculture, the coculture achieved 120% improvement in biomass production, 71 and 164% improvement in total nitrogen and total phosphorous removal, respectively, when the same amount of biogas was provided.

Introduction

Municipal, agricultural, and industrial processes generate large volumes of wastewater that are rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients. If not properly treated before released into waterways, wastewater can have detrimental impacts on the local community and environment. In fact, the excessive amount of nitrogen and phosphorus in released wastewater has caused increasingly negative consequences to our ecosystems and public health, including worsening of the greenhouse effect, reduction of the protective ozone layer, adding to smog, contributing to acid rain, and contaminating drinking water (Driscoll et al., 2003; Galloway et al., 2004). At the same time, wastewater contains stranded organic carbon, which represents a significant and underutilized feedstock to produce fuels and chemicals. If wastewater treatment can be integrated with producing value-added products, it will not only reduce the detrimental environmental and social impact of wastewater, but also generate revenue to offset the cost of wastewater treatment and even make the process profitable. As a result, waste-to-value (e.g., waste-to-energy, waste-to-fuel, and waste-to-chemical) technologies have drawn increasing research attention in the last few decades (Fei et al., 2014; Haynes and Gonzalez, 2014; Henard et al., 2016). However, to date, the only notable commercialized waste-to-value process at scale is anaerobic digestion (AD) which converts organic waste into biogas.

Currently, using AD to convert the stranded organic carbon in wastewater to biogas has been well-recognized and broadly adopted by municipal wastewater resource recovery facilities (WRRFs), particularly large scale WRRFs. In fact, 48% of total municipal wastewater flow in the Unites States is treated by AD (Qi et al., 2013), which corresponds to 1,484 of the 14,780 WRRFs in the Unites States. AD is a commercially proven technology, and arguably the most efficient solution for handling organic waste streams. During the AD process, a large fraction of organic matter is broken down into biogas (50–70% CH4, 30–50% CO2, with trace amounts of other gases such as H2S and NH3). Treating wastewater with AD offers many advantages including: 1) macronutrients (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, etc.) are transformed into more easily treatable forms which can significantly reduce their environmental impacts; 2) containment of the greenhouse gases as biogas (CH4 and CO2), which not only reduces greenhouse gases emission, but also provides a valuable fuel; 3) effective pathogen (>95%) and odor mitigation (Angelidaki and Ellegaard, 2003; Nasir et al., 2012). However, the impurities (CO2, NH3, H2S, etc.) in biogas limits its utilization to heating and electricity generation, and the low value of heat/electricity has hindered the installation of AD. For example, Zhang et al. (2013) show that sales of electricity and solid digestate as fertilizer do not compensate for the capital expenditures and operation expenses for small to medium-scale ADs. As a result, AD installation is currently limited to large-scale WRRFs, only 10% of all WRRFs.

Meanwhile, the liquid effluent of AD (i.e., digestate or biogas slurry) contains high concentrations of ammonia and orthophosphate which must be removed by the treatment plant prior to discharge. For the AD effluent samples provided by Columbus Water Works (Columbus, GA), the ammonia and orthophosphate concentrations were 807 ± 161 and 164 ± 71 mg/L over a 6-month period, respectively. In WRRFs with AD installed, the nutrient-rich digestate is often returned to a biological nutrient removal unit for further treatment. Biological nutrient removal is achieved through the so-called nitrification-denitrification process, where ammonia is converted to dinitrogen gas by activated sludge. However, the nitrification process requires large energy input to provide oxygen to the activated sludge (Siegrist et al., 2008), and the denitrification process often requires supplementation of an organic carbon source (e.g., methanol) to support nitrate reduction (Tam et al., 1992; Zhao et al., 1999). Pumping air and supplying organic carbon sources are the primary contributors to high operational costs for WRRFs (Drewnowski et al., 2019).

Recently, microalgae-based nutrient recovery from AD effluent and biogas upgrading has drawn increasing research interest. Many studies have shown that compared to monoculture of microalgae, cocultivation of microalgae and bacteria or fungi can deliver improved performance in terms of nutrient removal and biomass production. Zhang et al. (2020) provided a systematic review on the recent progress in this area. These microalgae-bacteria or microalgae-fungi coculture based approaches focus on biogas upgrading, i.e., removing CO2 and H2S from biogas, so that the treated biogas with high concentration of CH4 could be used for electricity generation or grid injection with less or no further cleaning up.

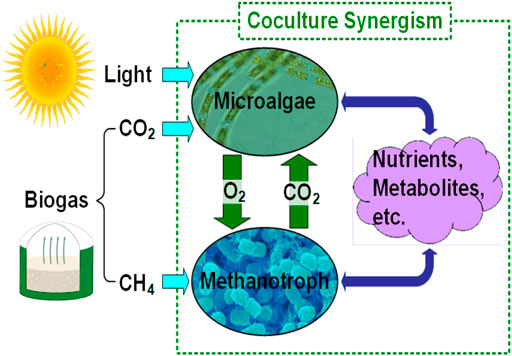

In this work, we propose a microalgae-methanotroph coculture platform for AD effluent treatment and biogas conversion, which converts both CH4 and CO2 contained in biogas into microbial biomass. The coculture biomass can be further processed into different value-added products, including animal feed supplement, biocrude, and bioplastics. As mixed microbial biomass valued much higher (e.g., dry biomass for bioplastics production has a selling price of $1,100/ton in 2020, personal communication with Algix LLC) than electricity (e.g., the average retail electricity price for industrial consumers was 6.83 ¢/kWh in 2019 according to statista.com), it is more desirable to convert CH4 into microbial biomass than burning CH4 for electricity generation. The proposed platform explores the synergistic interactions within a microalgae-methanotroph coculture to achieve significantly improved productivity of microbial biomass and enhanced nutrient recovery performance. As shown in Figure 1, through the interspecies coupling of methane oxidation to oxygenic photosynthesis, the microalgae-methanotroph coculture offers several advantages for biogas conversion: 1) exchange of in situ produced O2 and CO2 dramatically reduces mass transfer resistance of the two gas substrates; 2) excessive amount of O2 inhibits the growth of microalgae (Bilanovic et al., 2016), while in situ O2 consumption removes inhibition on microalgae and eliminates/reduces the risk of explosion (Zabetakis, 1965); 3) potential interspecies metabolic links could significantly enhance the growth of both strains in the coculture. In this work, using Chlorella sorokiniana–Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) as the model coculture, we demonstrate that the coculture achieved 100% recovery of ammonia [80% recovery of total nitrogen (TN)] and 100% recovery of orthophosphate [98% recovery of total phosphorous (TP)] when biogas supply is unlimited. In addition, the coculture achieved 100% CH4 and CO2 conversion into microbial biomass when nutrient supply is unlimited. Also, both the biomass production and nutrient (TN and TP) recovery performance of the microalgae-methanotroph coculture were significantly better compared to those of microalgae monoculture, achieving 120, 71, and 164% improvements, respectively, when the same amount of biogas was provided.

Materials and Methods

Wastewater Collection and Pretreatment

Municipal wastewater was collected from Columbus Water Works, a water resources facility in Columbus, GA. This facility treats an average of 45 million gallons of wastewater per day from homes, businesses, and industries. Anaerobic digestate samples were collected in clean plastic containers from the mesophilic digester #2 through sampling ports. Secondary clarifier effluent (CLE) was also collected from the top of clarifier #2 (water before chlorination and discharge into river). Wastewater samples were stored on ice for transportation to the lab where samples were frozen at −20°C.

Before each experiment, wastewater samples were thawed, and three different pretreatment methods were tested in this work—settled (S), filtered (F), and autoclaved (A). For settled samples, the thawed wastewater sample was set aside in refrigerator for 24 h to allow the solid fraction to settle down, and the top liquid phase was decanted for experiments; for filtered samples, the settled wastewater sample was filtered through a 0.2 µm filter (nylon; VWR) to remove most bacteria and small floating particles; for autoclaved samples, the filtered wastewater sample was further autoclaved to completely remove any bacteria contained in the digestate.

Precultures of the Methanotroph and Microalga

Cultures of M. capsulatus and C. sorokiniana were grown in 250 ml serum bottles sealed with a septum and aluminum cap. Pre-cultures of both strains were maintained on autoclaved anaerobic digestate diluted with the secondary CLE to ensure sterile monocultures. For methanotrophic growth, methane was supplied to a final concentration of 70% (v/v) CH4 and 30% (v/v) O2 and placed in a rotary shaker set at 200 rpm and 37°C. C. sorokiniana was also grown on the wastewater media and carbon dioxide was supplied to a final concentration of 30% (v/v) CO2 and 70% (v/v) N2. The vials were placed in a rotary shaker set at 200 rpm, 37°C and were cultivated under continuous illumination at 200 μmol m−2 s−1. Although there are reports that M. capsulatus may show optimal innate growth at 45°C (Medvedkova et al., 2009), several literatures also reported that the optimal temperature for M. capsulatus is 37°C (Patel and Hoare, 1971; Soni et al., 1998). This is debatable because the process can be limited by either methane oxidation and assimilation or mass transfer of methane from gas phase to liquid phase, which is highly dependent on many factors including reactor type, operation condition, cell density, etc. For industrial applications where most are limited by mass transfer, high temperature is not preferred due the reduced solubility of methane in aqueous solution at higher temperature and cell growth becomes even more mass transfer limited. In addition, C. sorokiniana is a thermotolerant strain and its optimal biomass production has been reported at 37–38°C (Franco et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013). Therefore, we chose to conduct the experiments under 37°C, which was also the temperature used by Rasouli et al. (2018) who examined the same coculture.

Coculture Experiments

In the following coculture experiments, cells were grown in 250 ml serum bottles sealed with a septum and aluminum cap with the differently diluted AD effluent mediums as culture media or defined medium as control. Cells were inoculated at a 3:1 (C. sorokiniana:M. capsulatus) ratio based on the optical density (OD) measured at 750 nm. In each vial, the initial OD for C. sorokiniana was 0.6 and the initial OD for M. capsulatus was 0.2. Synthetic biogas (70% CH4, 30% CO2) was used as carbon substrate and sparged through the medium for 10 min. The serum bottles were placed on a rotary shaker set at 200 rpm and 37°C with continuous illumination at 200 μmol m−2 s−1. After inoculation, both liquid and gas samples were taken once per day to measure total OD (Beckman Coulter DU Life Science UV/Vis spectrophotometer) and gas composition (Agilent 7890B with FID, TCD, Unibeads IS 60/80 mesh and MolSieve 5A 60/80 SST columns) following an established protocol (Stone et al., 2019). To track the amount of CO2 dissolved in liquid phase, total inorganic carbon of the liquid samples were also analyzed (Shimadzu TOC-VCSN analyzer). Individual biomass concentrations were determined based on an established protocol (Badr et al., 2019). Finally, ammonia-nitrogen (NH3-N) and orthophosphate (

Coculture Growth on Differently Diluted Anaerobic Digestion Effluent

Due to the high ammonia concentration and other potential inhibitors in the AD effluent, dilution of the AD effluent is necessary for microalgae and coculture-based wastewater treatment. This set of experiments was performed to investigate the effect of different diluents. In this work, three diluents were examined for their effect on coculture growth: 1) tap water (TW), 2) secondary CLE, and 3) a modified ammonium mineral salts (modified AMS) medium, which is the standard AMS medium (Whittenbury et al., 1970) without NH3-N and

Coculture Growth on Differently Pretreated Anaerobic Digestion Effluent Diluted by Clarifier Effluent

To investigate the effects of different wastewater pretreatment methods on the growth of the coculture, AD effluent diluted with CLE was used as the culture medium. Both the AD effluent and CLE were pretreated by three methods (settled, filtered, and autoclaved) as described in “Wastewater collection and pretreatment.” All pretreated AD effluent was diluted using CLE pretreated by the same method to a final NH3-N concentration of 120 mg/L. In addition, to examine the effect of potential inhibitors contained in AD effluent on the coculture growth, coculture cultivated on autoclaved AMS medium was also included as a control. In this experiment, after inoculation, both liquid and gas samples were taken once per day to measure total OD, gas composition, and individual biomass concentration.

Assessing Carbon Recovery Without Nutrient Limitation

These experiments were performed to assess the potential of the coculture for complete carbon recovery from biogas when unlimited nutrients were available. In addition, the coculture performance was compared with sequential single culture, i.e., C. sorokiniana followed by M. capsulatus. For this experiment, each 250 ml serum bottle started with 100 ml of the filtered AD effluent diluted five times with CLE. The feed gas composition of the coculture was 70% CH4, 30% CO2 while the single cultures feed gas compositions were 70% N2, 30% CO2 for C. sorokiniana and 70% CH4, 30% N2 for M. capsulatus. Every 24 h, the total amount of O2 produced by the single cultures of C. sorokiniana was determined and injected into each vial of M. capsulatus single culture. As a result, the inoculation of M. capsulatus vials occurred 24 h after the C. sorokiniana vials. The initial inoculum concentrations for each strain in the coculture were the same as that for each single culture; OD750 0.2 for M. capsulatus and OD750 0.6 for C. sorokiniana. Forty eight hours after inoculation, 20 ml of undiluted, filtered AD effluent was added to the bottle to prevent nutrient limitation. After inoculation, both liquid and gas samples were taken once per day to measure total OD750, gas composition, and individual biomass concentration.

Assessing Nutrient Recovery by the Coculture

These experiments were performed to assess the potential of the coculture for nutrient recovery from wastewater. Similarly, the coculture performance was compared with sequential single culture, i.e., C. sorokiniana followed by M. capsulatus. For this experiment, each 250 ml serum bottle started with 100 ml of the filtered AD effluent diluted five times with CLE; the feeding gas for the coculture and two single cultures was the same as that in Assessing Carbon Recovery Without Nutrient Limitation, so were the initial inoculum concentrations. After inoculation, both liquid and gas samples were taken once per day to measure total OD, gas composition, and individual biomass composition. In addition, to quantify the change in concentrations of the nutrients in the liquid medium, TN, ammonia-nitrogen (NH3-N), TP, and orthophosphate (

where

Biomass Composition Analysis

Compositional analysis of the coculture biomass was performed to determine the total carbohydrate and protein content. Total carbohydrate content of the microbial biomass was determined following the protocols given in Templeton et al. (2012) and Van Wychen and Laurens (2013). In brief, 2.0–2.5 mg of oven dried biomass were hydrolyzed by adding the cell pellet to 10 ml of 4 wt% H2SO4 and autoclaving at 121°C for 20 min. After allowing to cool to room temperature, the hydrolyzed sample was vortexed then filtered through a 0.2 µm nylon filter. Filtered hydrolysate was analyzed via high performance liquid chromatography (Agilent 1200 series with UV/Vis and IR detectors). Carbohydrates were separated using an Aminex HPX-87H column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) at 45°C with 0.05 M H2SO4 solution as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min. The time for each run was 25 min, during which only glucose and xylose were identified. Glucose and xylose concentrations were determined using calibrations performed with standard glucose and xylose solutions. Total protein content of the coculture biomass was determined following the protocol given in (Higgins et al., 2015). In summary, 2–2.5 mg of oven dried biomass were first suspended in 1.0 ml of deionized water. Zirconia beads (0.5 ml of 0.4 mm beads) were added to the cell suspension. Samples were disrupted using a Benchmark BeadBug™ 6 Homogenizer (Benchmark Scientific, Sayreville, NJ) for four cycles at maximum speed for 30 s with 90 s rest intervals. After the fourth cycle, 0.5 ml of 3× sodium dodecyl sulfate buffer (150 mM sodium phosphate, 3 mM disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.3% Triton X-100) were added to the disrupted cell suspension, followed by a final bead beat cycle. Supernatant of the disrupted cell suspension was collected, and TN concentration was determined using Nitrogen (Total) TNTplus Vial Test (HACH, Loveland, CO). Total elemental nitrogen was converted into percent protein using the following equation:

where Nf is the nitrogen factor. The nitrogen factor for C. sorokiniana was assumed to be 4.78 as given in (Laurens, 2013), whereas the specific nitrogen factor for M. capsulatus was assumed to be the traditional Kjeldahl conversion factor of 6.25. As the coculture biomass is comprised of C. sorokiniana and M. capsulatus, a coculture nitrogen factor was determined by taking the weighted average of the two individual nitrogen factors assuming a biomass ratio of 1.42:1 C. sorokiniana:M. capsulatus (determined in preliminary analyses) yielding a coculture nitrogen factor of 5.39.

Data Analysis and Statistics

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Analysis and standard deviation calculations were performed in Microsoft Excel. One-way ANOVA was performed in R using the “multcomp” package. The “PMCMRplus” package was used for performing Dunnett’s test. All statistical tests were conducted at a significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

Coculture Growth on Differently Diluted Anaerobic Digestion Effluent

AD effluent often contains various inhibitors, including volatile fatty acids, and antibiotics that may severely inhibit the growth of both microalgae and methanotroph in the coculture. For microalgae-based wastewater treatment, the digestate is usually diluted 10 or 20 times to achieve sustained growth of microalgae and enable sufficient nutrient recovery rates (Xia and Murphy, 2016; Wen et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). However, using freshwater to dilute AD effluent is not practical because freshwater is a limited resource in most locations. In this work, we examine the feasibility of using secondary CLE as a diluent in the proposed coculture technology. To ensure that the carbon substrate is not limited during the cultivation period, each vial was refed with synthetic biogas every 24 h.

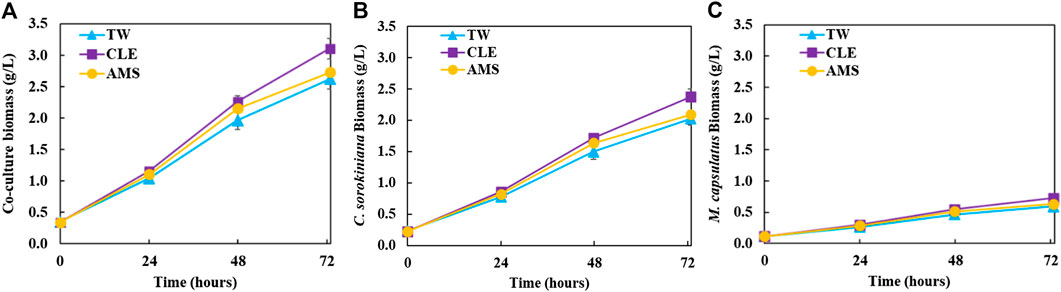

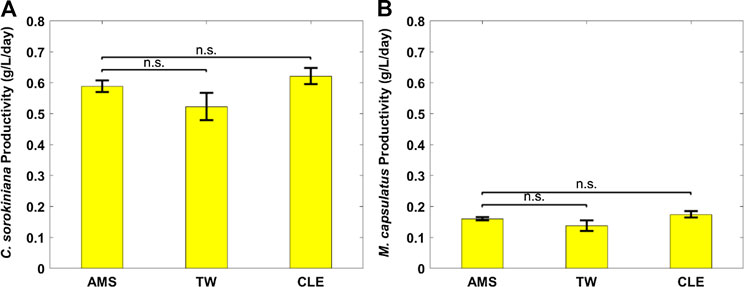

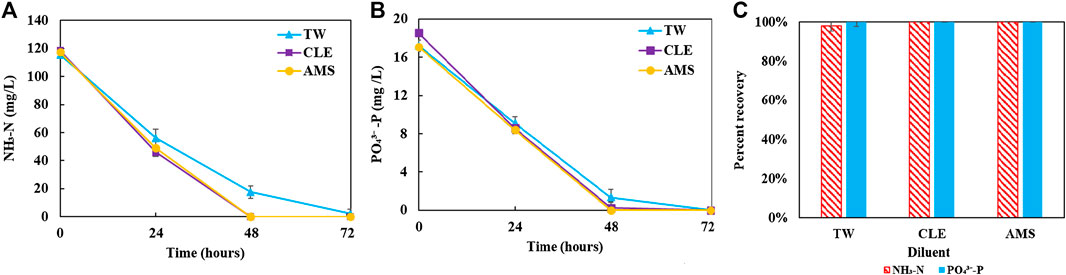

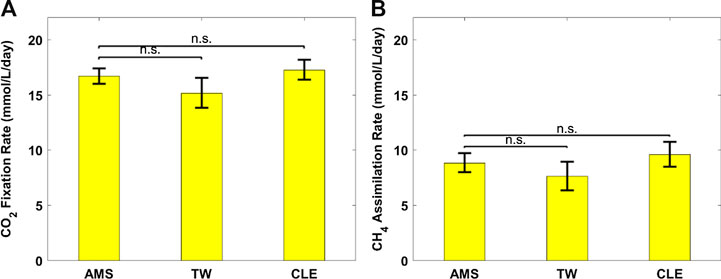

The coculture performance was evaluated by biomass production, biogas utilization and nutrient recovery. For the AD effluent diluted with three different diluents, Figure 2 plot the biomass profiles of the coculture and each microorganism in the coculture over the 72 h cultivation period; Figure 3 plot the biomass productivity of C. sorokiniana and M. capsulatus for the first 2 days; Figure 4 shows the inorganic nitrogen (NH3-N) and orthophosphates (

FIGURE 2. Growth profiles of the coculture on differently diluted anaerobic digestion effluent: (A) coculture biomass; (B) calculated Chlorella sorokiniana biomass in the coculture; (C) calculated Methylococcus capsulatus biomass in the coculture.

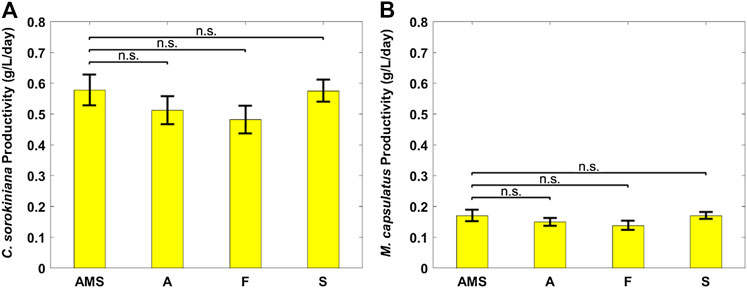

FIGURE 3. Biomass productivity of individual coculture strains on different anaerobic digestion diluents: (A) Chlorella sorokiniana and (B) Methylococcus capsulatus. The Dunnett’s test, with ammonium mineral salts (AMS) as the control, indicates that these differences are not significant (n.s.) statistically at significance level α = 0.05.

FIGURE 4. Residual nutrient concentrations: (A) inorganic ammonia nitrogen; (B) inorganic phosphorus; (C) recovery percentage at the end of culture period. They suggest that the coculture can effectively recover nutrient from diluted anaerobic digestion effluent.

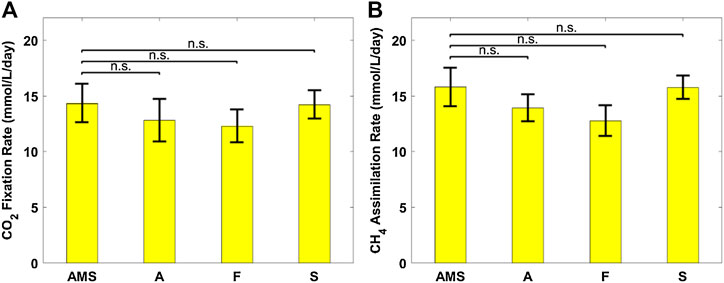

FIGURE 5. (A) CO2 fixation rate of Chlorella sorokiniana and (B) CH4 assimilation rate of Methylococcus capsulatus. The Dunnett’s test, with ammonium mineral salts (AMS) as the control, indicates that these differences are not significant (n.s.) statistically at significance level α = 0.05.

Figure 2 shows growth profiles of the coculture on differently diluted AD effluent. Biomass of individual strains in the coculture are calculated following the established protocol (Badr et al., 2019). Figure 3 compares biomass productivity of each strain. These figures show that the different diluents have negligible effects on the coculture growth and biomass productivity. This was confirmed by Dunnett’s tests with the modified AMS as the control. All pairwise comparisons of biomass productivity have p-values larger than 0.05, indicating there is no statistically significant difference among different diluents at significance level α = 0.05. This confirms that the secondary clarifier water can be used to replace TW to dilute AD effluent, therefore avoiding the need of fresh water for the proposed technology. Figure 2 shows that the growth of both microorganisms slowed down on the third day, potentially due to the depletion of nutrients in the wastewater. This is confirmed by nutrient measurements in Figure 4, which shows that most of the inorganic N and P were depleted by 48 h. This experiment confirms the effectiveness of the coculture in recovering the nutrients from wastewater, as demonstrated by near 100% recovery of ammonia nitrogen and orthophosphates. These results also confirm that the coupling of methane oxidation with oxygenic photosynthesis enabled continuous consumption of biogas (both CH4 and CO2) without external oxygen supply. In addition, there was no O2 accumulation in gas phase during the cultivation period, which eliminates the inhibition of excessive oxygen on microalgae growth and the risk of explosion. Finally, these results suggest that once N and P were exhausted, CH4 and CO2 consumption slowed down significantly, despite plenty of carbon substrate available in the gas phase.

Coculture Growth on Differently Pretreated Anaerobic Digestion Effluent Diluted by Clarifier Effluent

Liquid medium sterilization represents a major cost for most biotechnologies. Such cost could be justified if the technology produces highly valuable products such as pharmaceuticals. However, this is not the case for wastewater treatment. For the coculture-based technology to be applicable for wastewater treatment, minimum or no sterilization of the AD effluent is necessary. Therefore, we investigated the effect of different AD effluent pretreatment methods on the coculture growth to determine the feasibility of the microalgae-methanotroph coculture for wastewater treatment. Three different pretreatment methods of AD effluent were examined: settled (S), filtered (F) and autoclaved (A). In addition, we also tested coculture growth on sterilized AMS medium, which served as the control.

Figure 6 plots the biomass productivity of C. sorokiniana and M. capsulatus in the coculture grown on AD effluent pretreated differently, with AMS medium as the control case; and Figure 7 plots the CO2 fixation rate of C. sorokiniana and CH4 assimilation rate of M. capsulatus for the first 2 days. Both Figures 6 and 7 suggest that there is no significant difference among different pretreatment methods, which was confirmed by the Dunnett’s test (all pairwise comparisons with sterilized AMS medium as control have p-values larger than 0.05). This result clearly demonstrates the robustness of the coculture, as its growth was not affected by other microorganisms potentially present in the AD effluent.

FIGURE 6. Biomass productivity of individual coculture strains on differently pretreated anaerobic digestion effluent diluted by clarifier effluent: (A) Chlorella sorokiniana and (B) Methylococcus capsulatus. The Dunnett’s test, with ammonium mineral salts (AMS) as the control, indicates that these differences are not significant (n.s.) statistically at significance level α = 0.05.

FIGURE 7. (A) CO2 fixation rate of Chlorella sorokiniana and (B) CH4 assimilation rate of Methylococcus capsulatus. The Dunnett’s test, with ammonium mineral salts (AMS) as the control, indicates that these differences are not significant (n.s.) statistically at significance level α = 0.05.

Carbon Recovery by the Coculture Compared With Sequential Single Culture

This experiment was conducted to determine whether the model coculture could achieve complete biogas conversion (i.e., 100% CO2 fixation and 100% CH4 assimilation) without external oxygen supply. As shown in Coculture Growth on Differently Diluted Anaerobic Digestion Effluent, nutrient limitation will limit the carbon uptake by the coculture. To avoid such limitation, this experiment was conducted without nutrient limitation by adding 20 ml of undiluted AD effluent 48 h after inoculation to provide additional nutrients. To determine the improvement enabled by the coculture, experiments were also conducted with sequential single cultures of the individual species, i.e., C. sorokiniana followed by M. capsulatus. For the sequential single cultures experiment, oxygen produced by the microalgae single culture was provided to the methanotroph to enable methane oxidation.

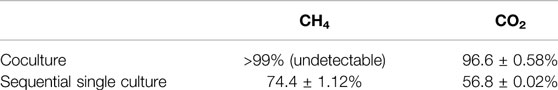

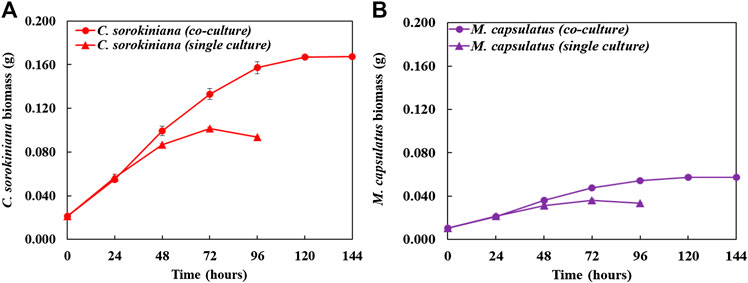

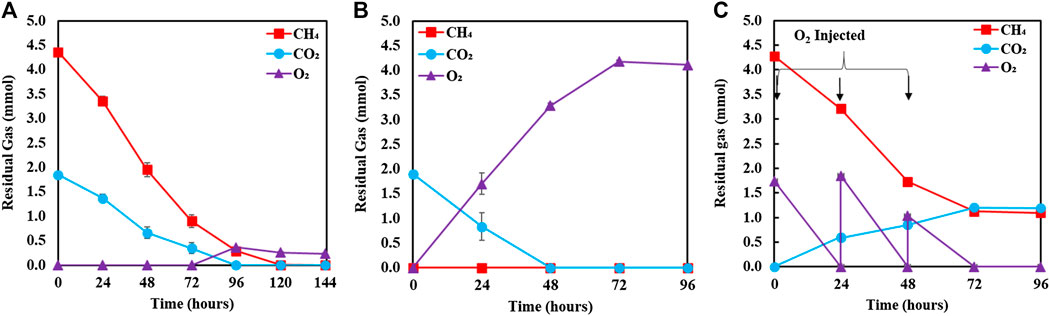

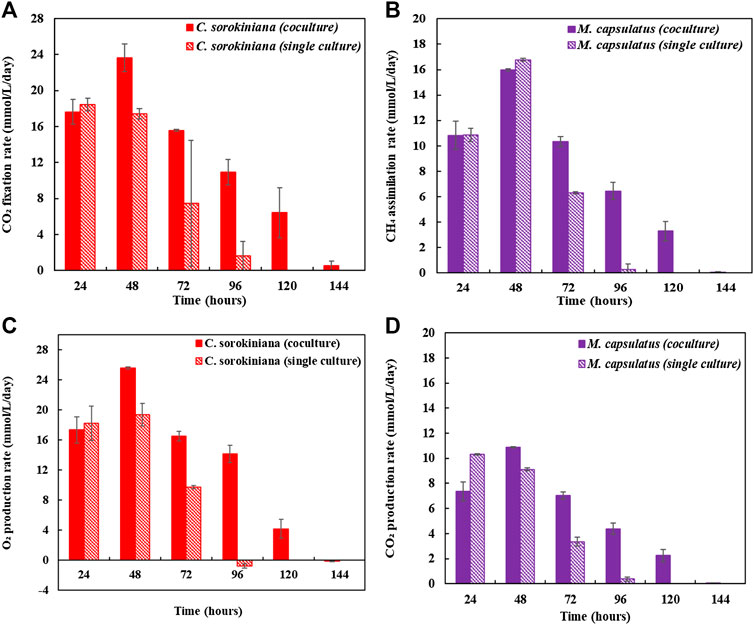

Figure 8 compares the biomass profiles of C. sorokiniana and M. capsulatus in coculture with that of sequential single cultures. Figure 9 plots the gas phase composition over time for the coculture and both single cultures. The vacuum created by the net consumption of gas substrates was compensated by filling with N2 to atmospheric pressure, which does not affect the amount, concentration, or partial pressure of the gas substrates. Figure 10 compares the CO2 fixation rate and O2 evolution rate of C. sorokiniana in coculture with that of microalgae single culture; as well as CH4 assimilation rate and CO2 production rate of M. capsulatus in the coculture with that of methanotroph single culture. Figure 8 shows that both C. sorokiniana and M. capsulatus in the coculture demonstrated significantly improved growth compared to the sequential single cultures. In this experiment, by providing the same amount of biogas, the biomass production of C. sorokiniana in the coculture (0.167 ± 0.001 g) shows a 64% increase compared to the single culture (0.102 ± 0.001 g), while the biomass production of M. capsulatus in the coculture (0.057 ± 0.001 g) shows a 58% increase compared to the sequential single culture (0.036 ± 0.001 g). Such significantly improved biomass production can be attributed to the metabolic coupling of methane oxidation and oxygenation through photosynthesis. In the coculture, CO2 generated through methane oxidation was utilized as additional substrate for photosynthesis, and the additional O2 produced from photosynthesis enabled complete CH4 conversion. This is confirmed by Figure 9, where the gas phase composition of the coculture shows no O2 accumulation until CH4 was almost depleted. As a result of the metabolic coupling, C. sorokiniana in the coculture shows significantly higher CO2 fixation rate and O2 evolution rate than the microalgae single culture; and M. capsulatus in the coculture shows much higher CH4 assimilation rate and CO2 production rate than the methanotroph single culture. In other words, there is no negative impact such as inhibition on C. sorokiniana growth due to the extra CO2 produced by M. capsulatus. In addition, the results show that CH4 has no effect on microalgae. This is likely due the very limited solubility of CH4 in the liquid medium. Table 1 compares the CH4 and CO2 conversion efficiency, which shows that the coculture was able to convert >99% of CH4 and 96.6% of CO2 while those of sequential single culture are much lower at 74.4 and 56.8%, respectively. The low conversion efficiency of CO2 in sequential single culture is mainly due to the fact that the CO2 produced by C. sorokiniana was not utilized.

FIGURE 8. Time-course profile of biomass comparing the individual species in coculture compared with sequential single culture: (A) Chlorella sorokiniana and (B) Methylococcus capsulatus.

FIGURE 9. Gas phase composition over time for (A) coculture, (B) sequential single culture microalga, and (C) sequential single culture methanotroph.

FIGURE 10. (A) CO2 fixation rate of Chlorella sorokiniana in coculture compared with that of microalgae single culture, (B) CH4 assimilation rate of Methylococcus capsulatus in the coculture compared with that of methanotroph single culture, (C) O2 evolution rate of C. sorokiniana in coculture compared with that of microalgae single culture, and (D) CO2 production rate of M. capsulatus in the coculture compared with that of methanotroph single culture.

Nutrient Recovery by the Coculture

This experiment was performed to determine whether the coculture offers an improvement in nutrient recovery compared to the sequential single cultures. The experimental setup was the same as that in the previous section, with the only difference being that no additional nutrient was added after 48 h. For all cultures, TN, inorganic nitrogen (NH3-N), TP and inorganic phosphorus (

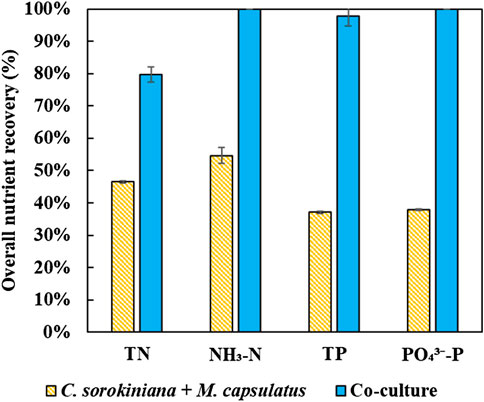

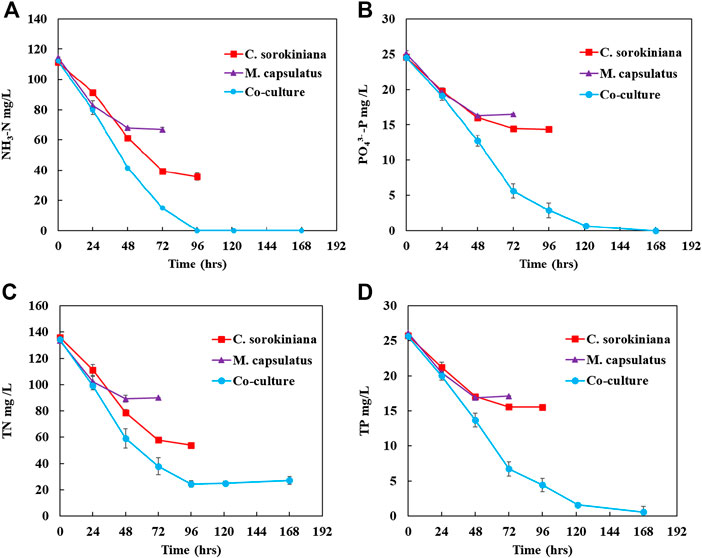

The concentration profiles for different nutrient components (NH3-N, TN,

FIGURE 11. Inorganic nutrient recovery by the sequential single cultures and by the coculture for (A) NH3-N, (B)

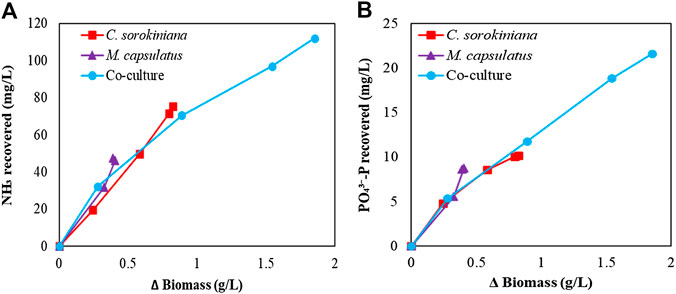

Figure 12 compares the nutrient recovery performance of the sequential single cultures summed together with that of the coculture, which clearly demonstrates the improvement provided by the coculture for nutrient recovery. The coculture demonstrated complete recovery of inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus, and significantly improved nutrient recovery efficiency than the single cultures by 83 and 164%, respectively. In terms of TN and TP, the improvements were 71 and 164%, respectively.

To determine if the enhanced nutrient recovery by the coculture was due to the enhanced growth, Figure 13 plots the amount of biomass produced vs. the amount of N and P recovered. For NH3-N recovery, Figure 13A shows that the coculture appears to recover more N per unit biomass produced than both single cultures at the beginning of the batch culture, while the rate decreases as more biomass was produced. This is likely due the reduced N supply from liquid medium. For

FIGURE 13. Correlation of the biomass produced with the recovery of (A) NH3-N and (B)

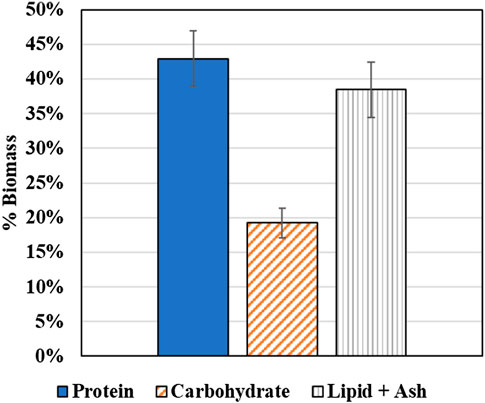

Composition Analysis of the Produced Coculture Biomass

The protein and carbohydrate composition of the coculture biomass samples were determined to identify prospective applications of the coculture biomass. While each individual species has been identified as potentially significant sources of protein for applications such as animal feed and bioplastics production, the biomass composition of the coculture grown together on diluted AD effluent as the culture medium has not been previously determined. Figure 14 plots the average biomass composition, i.e., protein, carbohydrate, and the combined lipid and ash content. As shown in Figure 14, the protein content is 43 ± 4% which makes the wastewater derived coculture biomass an ideal candidate for applications such as bioplastic production (35–60%) (personal communication with Algix LLC) and aquaculture feed (28–45%) (Craig and Helfrich, 2009).

Discussion

Application of Microalgae and Microalgae-Bacteria Coculture for Combined Biogas Upgrade and Wastewater Treatment

Due to their photosynthetic and nutrient recovery capabilities, microalgae have been studied in municipal wastewater treatment for over 50 years (Olguín, 2012; Su et al., 2012; Hende et al., 2014), and more recently for bioremediation of manure effluents (Woertz et al., 2009; Abou-Shanab et al., 2013). For algal biomass production, using alternative sources such as wastewater to support cell growth is highly attractive since nutrient costs have been one of the major limiting factors for sustained microalgae cultivation. In addition, it has been shown that supplementing CO2 in the municipal wastewater treatment can increase the algal biomass productivity by almost 3-fold (Abdel-Raouf et al., 2012). Recently microalgae have also been studied to upgrade biogas produced from AD of swine wastewater, and multiple studies have shown that microalgae or microalgae-bacteria consortia can remove >99% of H2S in biogas (Muñoz et al., 2015). These studies have demonstrated that using microalgae to remove CO2 and H2S is a promising method for biogas upgrading as well.

Recently microalgae-based, especially microalgae-bacteria coculture based, nutrient recovery from AD effluent (also called biogas slurry) and biogas upgrading have drawn increasing research interest. Among published microalgae-bacteria cocultures research, microalgae cultivated with activated sludge has received most research attention, which has shown improved performance in both nutrient recovery and biogas upgrade. Activated sludge contains nitrifiers and sulphur oxidizing bacteria, where nitrifiers oxidize ammonia into nitrate and sulphur oxidizing bacteria oxide hydrogen sulphide into sulphate. Both groups of bacteria consume the oxygen produced from microalgae photosynthesis, which reduces the oxygen content in the upgraded biogas. The recovery rate of TN, TP, and CO2, by most microalgae-bacteria cocultures were in the range of 40–70, 50–80, and 40–60%, respectively, and few studies reported recovery rate in the 80–90% range. It is important to note that the performances of different studies usually cannot be compared directly. For microalgae-bacteria cocultures-based nutrient recover and biogas upgrade, its performance depends heavily on species of microorganisms and the operation conditions, including light intensity, the photobioreactor configuration and operation mode (batch vs. continuous), the source of the wastewater (i.e., N and P content in the wastewater), etc. In addition, these microalgae-based approaches focus on biogas upgrading, i.e., removing CO2 and H2S from biogas, so that the upgraded biogas (i.e., biomethane) can be used for electricity generation.

In the last few years, microalgae-methanotroph coculture started to draw research attention. This is due to methanotrophs’ unique capability of using CH4 as the sole source of carbon and energy to grow. Among published research, Hill et al. (2017) validated the robustness of a cyanobacteria-methanotroph (20z–7002) pair in converting raw biogas (which contains 3000 ppm of H2S) into microbial biomass with synthetic media; Rasouli et al. (2018) demonstrated the first application of using microalgae-methanotroph (C. sorokiniana–M. capsulatus) coculture for nutrient recovery from a potato plant wastewater with synthetic biogas. Although the coculture pair examined in this work and by Rasouli et al. is the same and experiments were carried out under the same temperature, there are some major differences as well. Rasouli et al. utilized wastewater from a potato processing plant instead of AD effluent, and its N and P content were much lower (19 mg/L NH3-N and 14 mg/L TP); in addition, the wastewater was autoclaved and then centrifuged to ensure that none indigenous bacteria are active; the bioreactor volume is 600 ml with an additional 1 L gas bag, with a much higher light intensity (2,700 μmol m−2 s−1). Finally, the experiment was lasted for 24 h only. The final recovery rate for TN, TP, and CO2 achieved by the coculture by Rasouli et al. was 67, 43, and 27.5%, respectively, with the O2 in the gas phase of about 28%. It is also interesting to note that the coculture performance by Rasouli et al. was worse than the sequential single cultures.

Compared to the published work on microalgae-methanotroph research, this work is the first to demonstrate the robust growth of the coculture on minimally treated AD effluent, i.e., gravitational settling. More importantly, this work demonstrated complete biogas conversion, as well as complete recovery of ammonia and orthophosphate from AD effluent, with recovery rate and TN and TP reaching 79.8 and 97.8%, respectively. However, it is important to note that the performance of biogas conversion and nutrient recovery are interdependent of each other, and process optimization will play a critical role in the scaling up of the proposed application of the microalgae-methanotroph coculture.

Potential Products From the Coculture Microbial Biomass

Currently, most of the microalgae produced from wastewater treatment process is fed back to the AD to enhance biogas production. This is mainly due to the high cost of downstream processing needed to upgrade microalgae into biodiesel. To address this limitation, we suggest the following potential products for the coculture microbial biomass, which all directly utilize the whole cells of coculture biomass without separation or extensive processing.

First, if the source of the wastewater is determined to be safe (i.e., low level of heavy metal and antibiotics), such as the wastewater produced from winery and food processing plants, the wastewater-derived coculture biomass could be used as single cell protein for aquafeed supplement. It is worth noting that both microalgae and methanotroph have been extensively studied and tested as protein supplement for aquafeed supplements. For methanotrophs, trials in fish have shown that the protein meal derived from methanotrophs performs well as an alternative protein source to fish meal in feed formulations for Atlantic salmon (Aas et al., 2006), as well as improved growth performance and health benefits in aquatic and terrestrial animals (Romarheim et al., 2010; Øverland et al., 2010). For microalgae, positive testing results in fish and shrimp have suggested that a significantly higher dietary inclusion level of microalgal biomass in aquafeeds is expected (Becker, 2007; Teimouri et al., 2013; Gamboa-Delgado and Márquez-Reyes, 2018). These existing research reports suggest that the coculture biomass of microalgae and methanotroph could be a highly promising source for single cell protein, pending biomass composition analysis of the coculture. In this work, the microalgae-methanotroph coculture we obtained from AD effluent contained roughly 40% protein, confirming that the coculture biomass could be a potential source for single cell protein as animal feed or aquafeed protein supplement.

Next, microalgae-methanotroph coculture biomass is a promising source for producing bioplastics. As worldwide usage of plastics continues to increase, it is urgent to find ways of producing bioplastics in large quantities economically with comparable material properties to their petroleum counterparts. This is due to the detrimental environmental impact of petroleum-based plastics: preventing biodegradation, increasing demand and size of landfills. In addition, the process of resin production from crude oil further harms the environment by producing waste products, leading to air, water and ground contaminations (Zeller et al., 2013). It has been reported that microalgae derived bioplastics have similar properties as the petroleum-based plastics and thus can be “dropped in” to existing infrastructure and applications (Wang et al., 2016). Furthermore, existing research also suggest that mixed microalgae-bacteria biomass with proper protein content demonstrate similar properties as microalgae biomass for bioplastic production (Rahman and Miller, 2017). Therefore, as long as the protein content of microalgae-methanotroph coculture is within proper range (roughly 35–60%), the coculture biomass can be used to produce bioplastics.

Finally, for the coculture biomass with low protein content, it can be processed through hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) to produce biocrude. HTL is a promising route for producing renewable fuels and chemicals from wet biomass (Biller and Ross, 2012). It uses water contained in wet biomass at sub- or super-critical temperatures and pressures as a reactant and reaction medium (Gupta and Demirbas, 2010). Compared to conventional thermochemical processes (such as pyrolysis and gasification), HTL does not require dry biomass, which saves a huge amount of energy (Zou et al., 2009). In addition, HTL converts the whole cell, i.e., lipid, protein and carbohydrate, into biocrude, which increases the total oil production (Biller and Ross, 2011; Garcia Alba et al., 2011). Finally, HTL can use various feedstocks, such as microbial biomass, woody biomass, and sewage sludge, without pre-treatment. Therefore, using coculture biomass as a feedstock for biocrude production is also a viable option. However, at the end of HTL, the N and P content will be mainly left in the aqueous phase, which requires further treatment. Therefore, if the coculture biomass contains high protein content, producing biocrude through HTL may not be preferred.

Conclusion

In this work, we demonstrated that the microalgae-methanotroph coculture platform offers a highly promising technology for wastewater treatment and biogas valorization, which can simultaneously recover nutrients from AD effluent while converting biogas into microbial biomass. The coculture platform takes advantage of the metabolic coupling of methane oxidation with oxygenic photosynthesis and demonstrated significantly improved biomass productivity compared to microalgae-based wastewater treatment. Specifically, through an ongoing collaboration with Columbus Water Works (a municipal WRRF in Georgia), this work is the first to demonstrate that the model coculture C. sorokiniana and M. capsulatus can grow well and robustly on gravitationally settled AD effluent, without requiring any sterilization. In addition, it was confirmed that clarifier water from wastewater treatment can be used to replace fresh water to dilute AD effluent without affecting coculture growth. This is important as it demonstrated that the coculture-based wastewater treatment does not require fresh water supply to dilute the effluent. Enabled by the in situ exchange of O2 and CO2, the coculture was able to achieve complete biogas conversion, i.e., “zero emission” without external oxygen supply. More importantly, the coculture demonstrated complete recovery of inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus, and significantly improved efficiency than the single cultures by 83 and 164%, respectively. The enhanced capability of nutrient recovery by the coculture was highly correlated to the improved coculture growth due to the synergistic interaction within the culture. Finally, three groups of value-added products that can be derived from the coculture without requiring extensive processing were discussed, which include single cell protein for animal feed supplement, bioplastics and biocrude through HTL.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article have been provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

JW and QH conceived the idea, lead the experimental design, wrote the initial draft, and revised the manuscript; NR participated in the experimental design and conducted the experiments; NR and MH analyzed the results, and participated in the manuscript revision. NR, MH, QH, and JW read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, Genomic Science Program under award number DE-SC0019181 (for NR, QH, and JW) and by the US Department of Education, Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need Program under award number P200A150074 (for MH), P200A180002 (for JW).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenrg.2020.563352/full#supplementary-material

References

Aas, T. S., Grisdale-Helland, B., Terjesen, B. F., and Helland, S. J. (2006). Improved growth and nutrient utilisation in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) fed diets containing a bacterial protein meal. Aquaculture 259, 365–376. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.05.032

Abdel-Raouf, N., Al-Homaidan, A. A., and Ibraheem, I. B. M. (2012). Microalgae and wastewater treatment. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 19, 257–275. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2012.04.005

Abou-Shanab, R. A. I., Ji, M.-K., Kim, H.-C., Paeng, K.-J., and Jeon, B.-H. (2013). Microalgal species growing on piggery wastewater as a valuable candidate for nutrient removal and biodiesel production. J. Environ. Manage. 115, 257–264. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.11.022

Angelidaki, I., and Ellegaard, L. (2003). Codigestion of manure and organic wastes in centralized biogas plants: status and future trends. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 109, 95–105. doi:10.1385/abab:109:1-3:95

Badr, K., Hilliard, M., Roberts, N., He, Q. P., and Wang, J. (2019). Photoautotroph-methanotroph coculture—a flexible platform for efficient biological CO2-CH4 co-utilization. IFAC-PapersOnLine 52, 916–921. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2019.06.179

Becker, E. W. (2007). Micro-algae as a source of protein. Biotechnol. Adv. 25, 207–210. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2006.11.002

Bilanovic, D., Holland, M., Starosvetsky, J., and Armon, R. (2016). Co-cultivation of microalgae and nitrifiers for higher biomass production and better carbon capture. Bioresour. Technol. 220, 282–288. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2016.08.083

Biller, P., and Ross, A. B. (2011). Potential yields and properties of oil from the hydrothermal liquefaction of microalgae with different biochemical content. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 215–225. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2010.06.028

Biller, P., and Ross, A. B. (2012). Hydrothermal processing of algal biomass for the production of biofuels and chemicals. Biofuels 3, 603–623. doi:10.4155/bfs.12.42

Craig, S., and Helfrich, L. (2009). Understanding fish nutrition, feeds, and feeding, Communications and Marketing, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Virginia Tech, publication 420-256.

Drewnowski, J., Remiszewska-Skwarek, A., Duda, S., and Łagód, G. (2019). Aeration process in bioreactors as the main energy consumer in a wastewater treatment plant. Review of solutions and methods of process optimization. Processes 7 (5), 311. doi:10.3390/pr7050311

Driscoll, C., Whitall, D., Aber, J., Boyer, E., Castro, M., Cronan, C., et al. (2003). Nitrogen pollution: sources and consequences in the U.S. northeast. Environment 45, 8–22. doi:10.1080/00139150309604553

Fei, Q., Guarnieri, M. T., Tao, L., Laurens, L. M. L., Dowe, N., and Pienkos, P. T. (2014). Bioconversion of natural gas to liquid fuel: opportunities and challenges. Biotechnol. Adv. 32, 596–614. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.03.011

Franco, M. C., Buffing, M. F., Janssen, M., Lobato, C. V., and Wijffels, R. H. (2012). Performance of Chlorella sorokiniana under simulated extreme winter conditions. J. Appl. Phycol. 24, 693–699. doi:10.1007/s10811-011-9687-y

Galloway, J. N., Dentener, F. J., Capone, D. G., Boyer, E. W., Howarth, R. W., Seitzinger, S. P., et al. (2004). Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future. Biogeochemistry 70, 153–226. doi:10.1007/s10533-004-0370-0

Gamboa-Delgado, J., and Márquez-Reyes, J. M. (2018). Potential of microbial-derived nutrients for aquaculture development. Rev. Aquacult. 10, 224–246. doi:10.1111/raq.12157

Garcia Alba, L., Torri, C., Samorì, C., van der Spek, J., Fabbri, D., Kersten, S. R. A., et al. (2011). Hydrothermal treatment (HTT) of microalgae: evaluation of the process as conversion method in an algae biorefinery concept. Energy Fuels 26, 642–657. doi:10.1021/ef201415s

Gupta, R. B., and Demirbas, A. (2010). Gasoline, diesel, and ethanol biofuels from grasses and plants. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Haynes, C. A., and Gonzalez, R. (2014). Rethinking biological activation of methane and conversion to liquid fuels. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 331–339. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1509

Henard, C. A., Smith, H., Dowe, N., Kalyuzhnaya, M. G., Pienkos, P. T., and Guarnieri, M. T. (2016). Bioconversion of methane to lactate by an obligate methanotrophic bacterium. Sci. Rep. 6, 21585. doi:10.1038/srep21585

Hende, S. V. D., Carré, E., Cocaud, E., Beelen, V., Boon, N., and Vervaeren, H. (2014). Treatment of industrial wastewaters by microalgal bacterial flocs in sequencing batch reactors. Bioresour. Technol. 161, 245–254. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2014.03.057.

Higgins, B. T., Labavitch, J. M., and VanderGheynst, J. S. (2015). Co-culturing Chlorella minutissima with Escherichia coli can increase neutral lipid production and improve biodiesel quality. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 112, 1801–1809. doi:10.1002/bit.25609

Hill, E. A., Chrisler, W. B., Beliaev, A. S., and Bernstein, H. C. (2017). A flexible microbial co-culture platform for simultaneous utilization of methane and carbon dioxide from gas feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. 228, 250–256. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2016.12.111

Laurens, L. M. L. (2013). NREL/TP-5100-60943. Summative mass analysis of algal biomass – integration of analytical procedures: laboratory analytical procedure (LAP). Available at: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1118072 (Accessed August 30, 2020).

Li, T., Zheng, Y., Yu, L., and Chen, S. (2013). High productivity cultivation of a heat-resistant microalga Chlorella sorokiniana for biofuel production. Bioresour. Technol. 131, 60–67. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.11.121

Medvedkova, K. A., Khmelenina, V. N., Suzina, N. E., and Trotsenko, Y. A. (2009). Antioxidant systems of moderately thermophilic methanotrophs Methylocaldum szegediense and Methylococcus capsulatus. Microbiology 78, 670. doi:10.1134/s0026261709060022

Muñoz, R., Meier, L., Diaz, I., and Jeison, D. (2015). A review on the state-of-the-art of physical/chemical and biological technologies for biogas upgrading. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 14, 727–759. doi:10.1007/s11157-015-9379-1

Nasir, I. M., Mohd Ghazi, T. I., and Omar, R. (2012). Anaerobic digestion technology in livestock manure treatment for biogas production: a review. Eng. Life Sci. 12, 258–269. doi:10.1002/elsc.201100150

Olguín, E. J. (2012). Dual purpose microalgae-bacteria-based systems that treat wastewater and produce biodiesel and chemical products within a biorefinery. Biotechnol. Adv. 30, 1031–1046. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.05.001

Øverland, M., Tauson, A.-H., Shearer, K., and Skrede, A. (2010). Evaluation of methane-utilising bacteria products as feed ingredients for monogastric animals. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 64, 171–189. doi:10.1080/17450391003691534

Patel, R. N., and Hoare, D. S. (1971). Physiological studies of methane and methanol-oxidizing bacteria: oxidation of C-1 compounds by Methylococcus capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 107, 187–192. doi:10.1128/jb.107.1.187-192.1971

Qi, Y., Beecher, N., and Finn, M. (2013). Biogas production and use at water resource recovery facilities in the United States. Alexandria, VA: Water Environment Federation.

Rahman, A., and Miller, C. D. (2017). “Microalgae as a source of bioplastics,” in Algal green chemistry: recent progress in biotechnology. Editors R. Rastogi, D. Madamwar, and A. Pandey (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier), 121–138.

Rasouli, Z., Valverde-Pérez, B., D’Este, M., De Francisci, D., and Angelidaki, I. (2018). Nutrient recovery from industrial wastewater as single cell protein by a co-culture of green microalgae and methanotrophs. Biochem. Eng. J. 134, 129–135. doi:10.1016/j.bej.2018.03.010

Romarheim, O. H., Øverland, M., Mydland, L. T., Skrede, A., and Landsverk, T. (2010). Bacteria grown on natural gas prevent soybean meal-induced enteritis in Atlantic salmon. J. Nutr. 141, 124–130. doi:10.3945/jn.110.128900

Siegrist, H., Salzgeber, D., Eugster, J., and Joss, A. (2008). Anammox brings WWTP closer to energy autarky due to increased biogas production and reduced aeration energy for N-removal. Water Sci. Technol. 57, 383. doi:10.2166/wst.2008.048

Soni, B. K., Conrad, J., Kelley, R. L., and Srivastava, V. J. (1998). Effect of temperature and pressure on growth and methane utilization by several methanotrophic cultures. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 70, 729–738. doi:10.1007/BF02920184

Stone, K. A., He, Q. P., and Wang, J. (2019). Two experimental protocols for accurate measurement of gas component uptake and production rates in bioconversion processes. Sci. Rep. 9, 5899. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42469-3

Su, Y., Mennerich, A., and Urban, B. (2012). Comparison of nutrient removal capacity and biomass settleability of four high-potential microalgal species. Bioresour. Technol. 124, 157–162. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.08.037

Tam, N., Wong, Y., and Leung, G. (1992). Effect of exogenous carbon sources on removal of inorganic nutrient by the nitrification-denitrification process. Water Res. 26, 1229–1236. doi:10.1016/0043-1354(92)90183-5

Teimouri, M., Amirkolaie, A. K., and Yeganeh, S. (2013). The effects of Spirulina platensis meal as a feed supplement on growth performance and pigmentation of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture 396–399, 14–19. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.02.009

Templeton, D. W., Quinn, M., Van Wychen, S., Hyman, D., and Laurens, L. M. L. (2012). Separation and quantification of microalgal carbohydrates. J. Chromatogr. A 1270, 225–234. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2012.10.034

Van Wychen, S., and Laurens, L. M. L. (2013). NREL/TP-5100-60957. Determination of total carbohydrates in algal biomass: laboratory analytical procedure (LAP). Available at: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1118073 (Accessed August 30, 2020).

Wang, K., Mandal, A., Ayton, E., Hunt, R., Zeller, M. A., and Sharma, S. (2016). “Modification of protein rich algal-biomass to form bioplastics and odor removal,” in Protein byproducts. Editor G. Singh Dhillon (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier), Chap. 6.

Wang, Q., Higgins, B., Ji, H., and Zhao, D. (2018). “Improved microalgae biomass production and wastewater treatment: pre-treating municipal anaerobic digestate for algae cultivation,” in ASABE 2018 Annual International Meeting, Detroit, MI, July 29–August 1, 2018.

Whittenbury, R., Phillips, K. C., and Wilkinson, J. F. (1970). Enrichment, isolation and some properties of methane-utilizing bacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 61, 205 doi:10.1099/00221287-61-2-205

Wen, Y., He, Y., Ji, X., Li, S., Chen, L., Zhou, Y., et al. (2017). Isolation of an indigenous Chlorella vulgaris from swine wastewater and characterization of its nutrient removal ability in undiluted sewage. Bioresour. Technol. 243, 247–253. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.094

Woertz, I., Feffer, A., Lundquist, T., and Nelson, Y. (2009). Algae grown on dairy and municipal wastewater for simultaneous nutrient removal and lipid production for biofuel feedstock. J. Environ. Eng. 135, 1115–1122. doi:10.1061/(asce)ee.1943-7870.0000129

Xia, A., and Murphy, J. D. (2016). Microalgal cultivation in treating liquid digestate from biogas systems. Trends Biotechnol. 34, 264–275. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.12.010

Zabetakis, M. G. (1965). Bulletin 627. Flammability characteristics of combustible gases and vapors. Bureau of Mines, US Department of The Interior doi:10.2172/7328370

Zeller, M. A., Hunt, R., Jones, A., and Sharma, S. (2013). Bioplastics and their thermoplastic blends from Spirulina and Chlorella microalgae. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 130, 3263–3275. doi:10.1002/app.39559

Zhang, B., Li, W., Guo, Y., Zhang, Z., Shi, W., Cui, F., et al. (2020). Microalgal-bacterial consortia: from interspecies interactions to biotechnological applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 118, 109563. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2019.109563

Zhang, Y., White, M. A., and Colosi, L. M. (2013). Environmental and economic assessment of integrated systems for dairy manure treatment coupled with algae bioenergy production. Bioresour. Technol. 130, 486–494. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.11.123

Zhao, H. W., Mavinic, D. S., Oldham, W. K., and Koch, F. A. (1999). Controlling factors for simultaneous nitrification and denitrification in a two-stage intermittent aeration process treating domestic sewage. Water Res. 33, 961–970. doi:10.1016/S0043-1354(98)00292-9

Keywords: microalgae-methanotroph coculture, wastewater treatment, waste-to-value conversion, anaerobic digestion, biogas valorization, nutrient recovery

Citation: Roberts N, Hilliard M, He QP and Wang J (2020) A Microalgae-Methanotroph Coculture is a Promising Platform for Fuels and Chemical Production From Wastewater. Front. Energy Res. 8:563352. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2020.563352

Received: 18 May 2020; Accepted: 18 August 2020;

Published: 08 September 2020.

Edited by:

Wei Wang, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (DOE), United StatesReviewed by:

Dillirani Nagarajan, National Cheng Kung University, TaiwanShunni Zhu, Guangzhou Institute of Energy Conversion (CAS), China

Copyright © 2020 Wang, Roberts, Hilliard and He. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jin Wang, d2FuZ0BhdWJ1cm4uZWR1

Nathan Roberts

Nathan Roberts