- 1Key Laboratory of Advanced Ceramics and Machining Technology of Ministry of Education, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Composite and Functional Materials, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China

- 2National Engineering Laboratory for Public Safety Risk Perception and Control by Big Data, Beijing, China

- 3Materials Engineering, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 4College of Intelligence and Computing, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China

- 5School of Life Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

Energy shortage is a severe challenge nowadays. It has affected the development of new energy sources. Artificial intelligence (AI), such as learning and analyzing, has been widely used for various advantages. It has been successfully applied to predict materials, especially energy storage materials. In this paper, we present a survey of the present status of AI in energy storage materials via capacitors and Li-ion batteries. We picture the comprehensive progress of AI in energy storage materials, including the advantages and disadvantages of material data to support AI. Finally, we provide some ideas to solve those challenges.

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has developed as a branch of computer science for a long time since it was proposed at the Dartmouth Society in 1956. In essence, it is the simulation of human consciousness and thinking by machines. It allows machines to solve complex problems in a humanlike way. With the development of related technologies, such as big data, cloud computing, Internet of Things, etc., AI has shown great advantages due to its high speed and high accuracy. Subsequently, AI has been widely used in various fields, such as face recognition (Rehman et al., 2020), natural language processing (Giménez et al., 2020), and brain cognition (Samsonovich, 2020). With the advent of AlphaGo (Kim, 2019), the expansion of human cognition by machines and the continuous development of AI have been constantly expanded. Correspondingly, its applicable scenarios have been continuously expanded. Its application has been extended to the fields of psychology (Miller, 2020), education, and driverless breakthrough development. As a subset of AI, machine learning (ML) is becoming more and more important. It emphasizes the process and independence of learning. Turing suggested that instead of focusing on whether a machine was intelligent, researchers should consider whether it is possible for a machine to show intelligent behavior (Turing, 2006).

Since the beginning of the 21st century, energy and environmental issues have become increasingly serious. People are urgently seeking for clean and efficient energy sources. Global energy consumption is gradually shifting from traditional fossil fuels to clean and low-carbon energy sources. Energy consumption generally includes two major aspects, namely the energy conversion and storage. In terms of energy storage, due to the rapid storage and release of energy from renewable sources, the requirements of high charge and discharge rates and low cost are becoming increasingly important for modern electrochemical energy storage technology (Yang et al., 2019a; Cheng et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). We need to realize fast and reversible conversion, especially energy storage materials such as long-life, high-power, large-capacity, low-cost secondary batteries and capacitors with high dielectric constant and high energy density (Zhang et al., 2019a). This can not only promote the rapid development of electric vehicles, information transportation, and other fields but also realize the rational usage of energy as well as improved energy utilization efficiency. However, the limited energy storage capacities of the materials restrict development. Among various electrochemical energy storage devices, Li-ion batteries (LIBS) (Xu et al., 2020) and electrochemical capacitors (ECs) (Ezeigwe et al., 2020) are the two most important devices. Although recent research and development have significantly improved their electrochemical performance (Liang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020), there still exist some disadvantages. Generally speaking, energy storage techniques has the problems of low density and high cost. For LIBS, a major limitation is the slow Li-ion migration and diffusion process in solid-state electrode materials. ECs usually have limited energy densities. Hence, there is an urgent need to develop new energy storage materials to improve energy efficiency (Yan et al., 2017). However, for the development of new material, the time span from material development to market is extremely long. The key reason is that research and development of materials rely on scientific intuition and trial-and-error experiments, which is time-consuming. Hence, the development cycle is long.

Materials scientists have paid attention to this challenge and made breakthroughs. Recently, the application of ML has been made important advances in the field of materials science. This field is often called “materials informatics.” The materials science community uses materials informatics to accelerate the process of material discovery and establish a new understanding of material behavior. They also can extract new knowledge or build predictive models from existing material data. They build a model that uses complex algorithms to identify and analyze large amounts of data without the need for humans to write specific instructions, and thereby make corresponding predictions. For example, a Materials Project of MIT is a well-known large-scale high-throughput computing platform and material database for materials genome. The Materials Project contains a database that stores a large amount of information (with nearly 60,000 crystal structures) such as various calculation information, including energy band density information, battery materials, charge-discharge curves, phase diagrams, etc. This database can store the results of high-throughput material property for further calculations. The shared platform effectively reduces the proportion of human factors in the experiment and relies more on the intelligent analysis of the machine, which has accelerated the development of materials and made great progress. CEDER et al. have done a lot of research on the structure and phases of lithium battery materials (Van der Ven et al., 2000, 2001; Arroyo-de Dompablo et al., 2001; Van der Ven and Ceder, 2001). In these researches, they used a cluster expansion method developed from the Monte Carlo method of metallurgical calculation. This method is a method that uses partially known density functional calculation results to fit the total energy of the system and then uses the fitted results to predict the total energy of the unknown system. This method combines high-throughput computer calculation with the traditional method of density functional theory. It can speed up the calculation speed and improve the efficiency of research. We list some learning resources and tools associated with ML (Butler et al., 2018) for the reference of readers in Table 1.

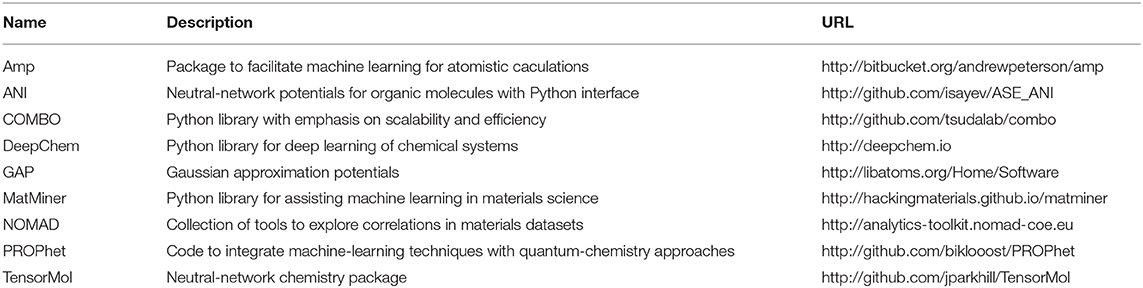

Table 1. ML tools for molecular and materials which are public and available to use from Butler et al. (2018).

In this review, firstly, we briefly introduce the development of AI technology and then introduce the application of AI technology in energy storage. Finally, the advantages, disadvantages, and future prospects of AI technology are analyzed.

AI for Capacitor Development

In recent years, electric double-layer capacitors (EDLCs, a.k.a. supercapacitors) have attracted great interest due to their huge energy storage potential, long maintenance-free life, high cycling efficiency, and high power density (Stoller and Ruoff, 2010; Berrueta et al., 2019; Song et al., 2020). Double-layer capacitors play important roles in products such as electric vehicles and batteries. Meanwhile, their low energy density is a limiting factor in their widespread usage, and one solution is using ML to boost the development of new capacitor materials. Carbon-based materials are widely used as double-layer capacitor electrodes (Ajay and Dinesh, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018a; Su et al., 2019) due to their large specific surface area, high porosity, high electrical conductivity, low cost, easy availability, and environmental friendliness.

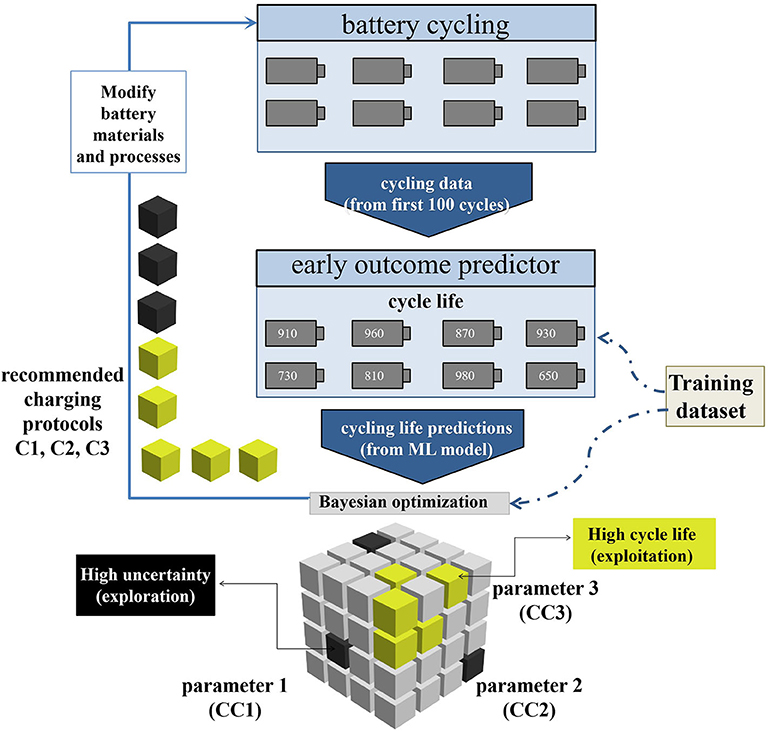

Traditionally, the larger specific surface area of the electrode leads to the greater capacitance. For this reason, the preferred pores in the electrodes are micropores (<2 nm). However, many kinds of literature prove that only micropores in the electrode decreased the power density and capacitance of the EDLC (Eliad et al., 2001; Ghosh and Lee, 2012; Hasegawa et al., 2012). Zhou et al. (2020) used AI to quantitatively correlate the structural characteristics of the electrodes with power densities to optimize the dimensions of mesopores and micropores simultaneously. In this work, they proposed a physical-based ML method to study the influence of the structural characteristics of carbon-based electrodes on the capacitance and power density. Four ML algorithms, namely the generalized linear regression, generalized linear classifier, decision tree, and neural-based network, were used. The calculation results are shown in Figure 1 (Zhou et al., 2020). As can be seen, each ML algorithm can find the correct trend. However, their efficiencies in representing the experimental results are apparently different. And ANN fits best.

Figure 1. Correlations between experimental and different ML models for the specific capacitance (Csp, F/g) of activated carbons: (A) generalized linear regression (GLR), (B) support vector machine (SVM), (C) random forest (RF), (D) artificial neural network (ANN). (E) Artificial neural network (ANN) model for correlating the power density of activated carbons. In each panel, the diagonal line represents the perfect correlation between experimental and machine-learning results.

The machine learning method can correlate the input and output while ignoring the physical conditions. Once the correlation is established, the ANN can reproduce the experimental data of the carbon electrode well in the scanning speed range of 2 mv ~ 500 mv. Utilizing the new insights in the work can boost researches on the synthesis and preparation of carbon-based electrodes, and improve the performance of supercapacitors.

AI for Battery Materials

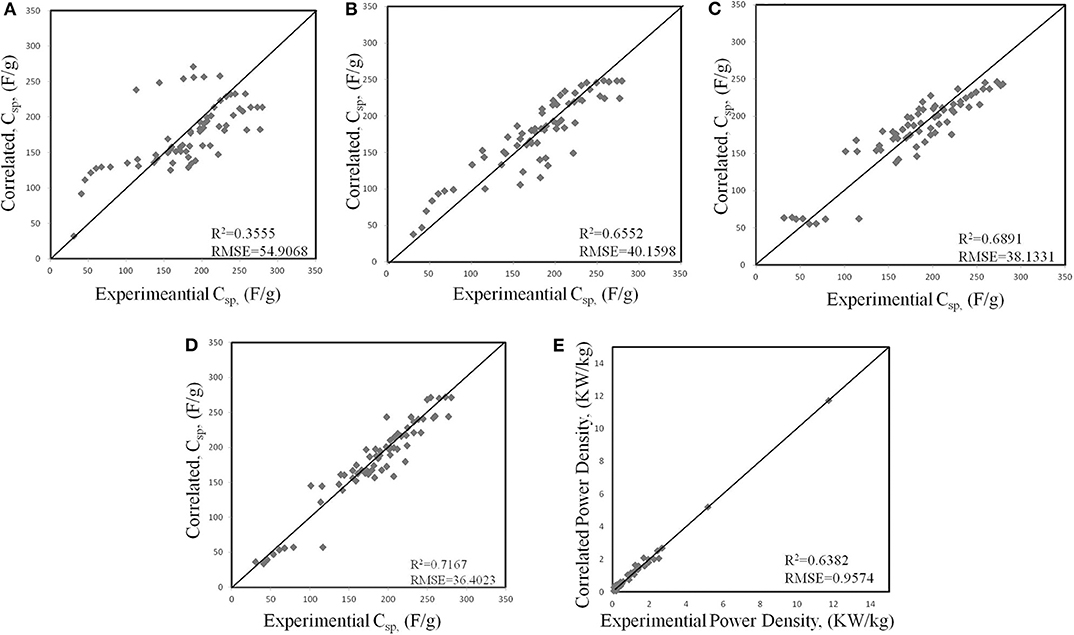

In the development of batteries, from the discovery of new materials to the testing at each stage, each link takes months or even years to evaluate. This has become a factor limiting the development of batteries. Applying AI to developing new battery materials, testing battery performance and monitoring battery state of charge (SOC) (Du et al., 2015; Flamand et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019) can greatly alleviate this problem. For instance, a team led by Stanford University professors Stefano Ermon and William Chueh developed a ML method that can reduce the testing time by 98% (Attia et al., 2020). The schematic of their closed-loop optimization (CLO) system is shown in Figure 2. Firstly, the researchers test the batteries with the first 100 cycling data, especially electrochemical measurements (capacity and voltage, etc.). The researchers make an early outcome prediction of cycling life by using this data as input. The cycling life predicted by the ML model is sent to a Bayesian optimization (BO) algorithm to test the next protocol. This procedure repeated until the test budget is used up. Not only can this method make early predictions to reduce the cycling number of each battery test, but it can also reduce the number of required experiments through optimal experimental design. These can greatly reduce time consumption. Nine validation protocols include the four protocols inspired by the battery literature (Notten et al., 2005; Zhang, 2006; Mehta and Straubel, 2009; Paryani, 2009; Min et al., 2016) (“Literature-inspired”), the top three protocols as estimated by CLO (“CLO top 3”) and two protocols selected to obtain a representative sampling from the distribution of CLO-estimated cycle lives among the validation protocols (“Other”). CLO can quickly identify high-performance charging protocols with the help of early prediction and Bayesian optimization. When resources are constrained, the benefits of Bayesian optimization will become larger. These methods can accelerate almost every stage of battery development, including designing chemical and electrochemical properties of the batteries, determining their sizes and shapes, and finding better manufacturing and storage systems, etc. This will have a wide impact on the development and production of energy storage devices.

Anode

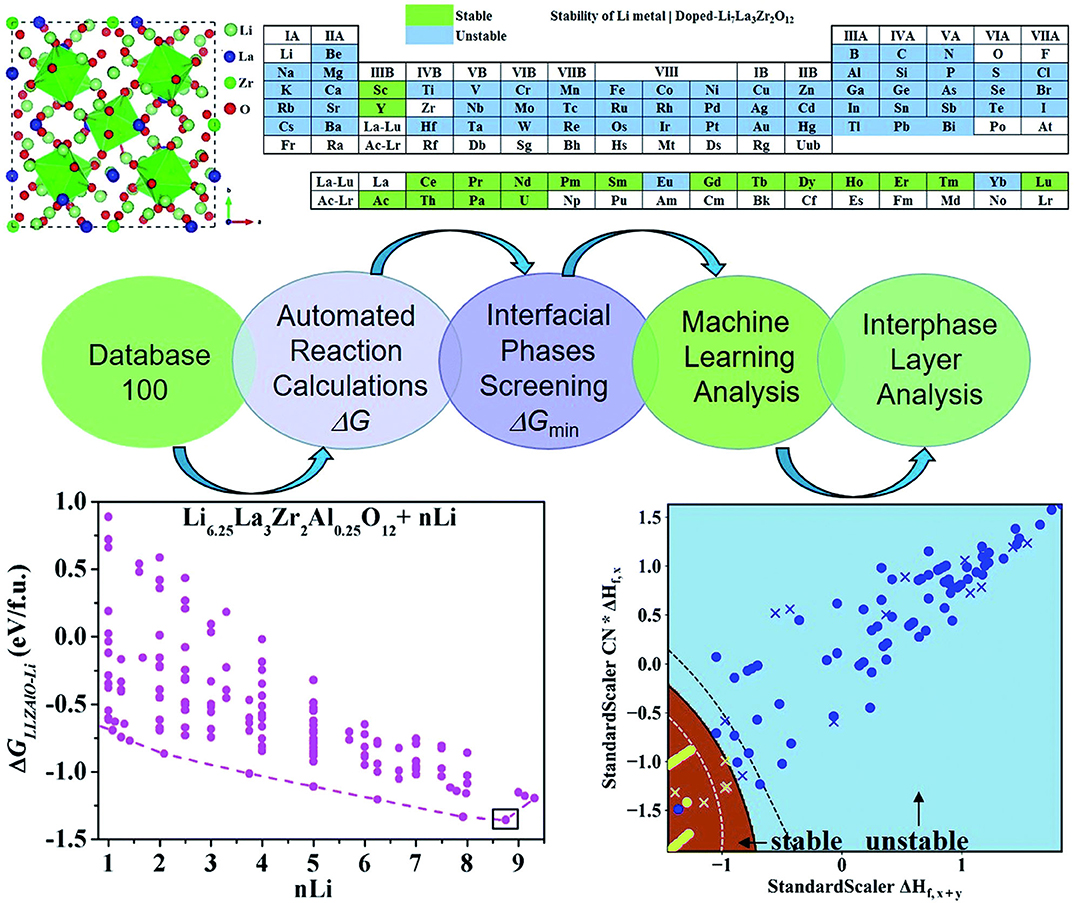

Lithium metal has low negative electrochemical potential, low density, and extremely high theoretical specific capacity. Thus, Lithium is subsequently considered as a possible anode material for future energy storage devices with high energy density. However, high reactivity and dendrite growth of lithium metal anodes lead to low cycle efficiency and serious safety risks. Currently, one solution is stabilizing lithium metal anodes through doping cations. There are many potential dopable elements, such as Zr, Nd, Lu, Pm, Tb, etc. It is labor and material wasting to perform the experiments one by one. Plus, the results might be unsatisfactory. Liu et al. (2019) use a ML method to develop a high-throughput automated reaction screening system based on the first-principle method of large material databases. They estimate the thermodynamic stability and possible reactions of the Li|Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZOM, M = dopant) interfaces. The methods include the formation of energy calculations, phase stability calculations, first-principles calculations, and ML methods. The workflow is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. ML and the automated interface reaction screening process workflow, which can expeditiously find cation-doped LLZO thermodynamically stable to lithium metal. The dopant screening, automated interface reaction screening, atomic structure, and interface stability ML classification results are presented. Reprinted with permission from Liu et al. (2019). Copyright (2013) Royal Society of Chemistry (Great Britain).

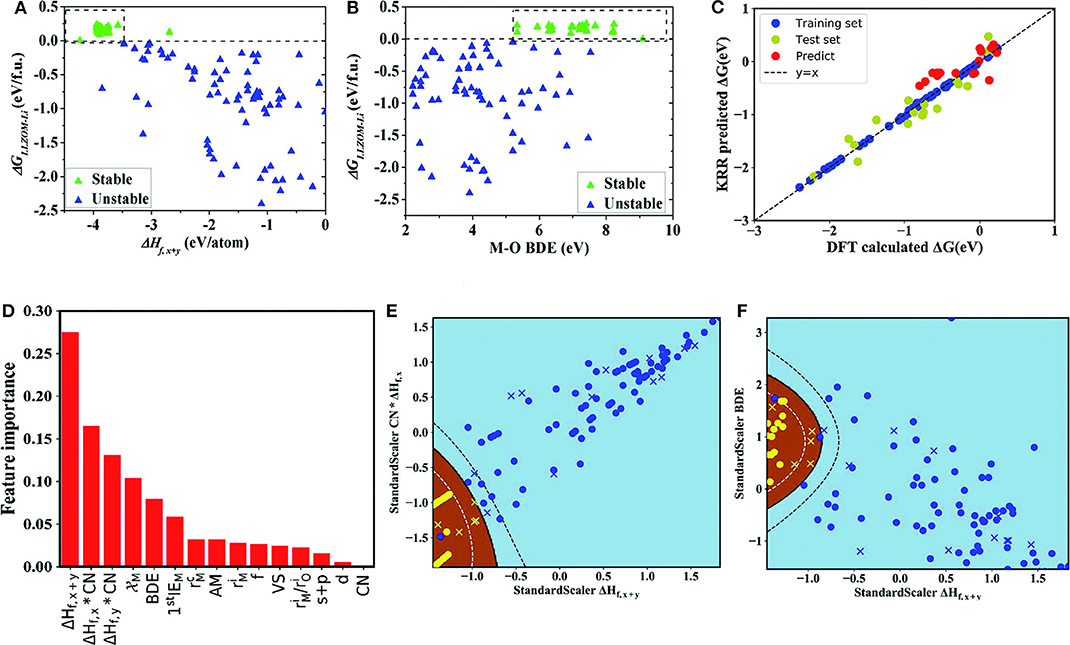

In this research, due to the different doping elements, ML can be performed while employing the relevant attributes of doping elements as features. These relevant characteristics include the valence state (VS) of the dopant element M, the ion radius and the atom radius, the first ionization energy y(1stIEM), Pauling electronegativity, and so on. This team adopts ML techniques in two ways: the binary classification problem and the regression problem. The first one was used to predict the thermodynamic stability of the Li|LLZOM interface. The other was used to predict the Li|LLZOM interface reaction energy. The team used five classification algorithms, including logistic regression (Groenitz, 2018), decision tree (Westreich et al., 2010), support vector machine (SVM) (Travis-Lumer and Goldberg, 2015), neural network (Xueliang, 2017), and extra tree. Each classification algorithm is fitted using the training data with more than one feature at a time. Based on the results of the ML program, it can be concluded that the local M-O chemical bond strength can measure the stability of the Li|LLZOM interface. The team expressed the relationships between reaction energy and single feature in Figure 4 to quantify the thermodynamic stability of the Li|LLZOM interface.

Figure 4. The dependence of the reaction energy ΔGLLZOM−Li of Li|LLZOM interface on (A) ΔHf,x+y, and (B) M-O bond dissociation energy. The most appropriate range for each feature is shown by dotted boxes. (C) The predicted reaction energies using a KRR model compared with DFT calculated reaction energies (ΔG). The model is trained on a randomly selected 80% training set from the 100 LLZOM database using the 15 features. The mean squared error (MSE) and the coefficient of determination (R2) are calculated to estimate the prediction errors. The test and training points are displayed in green and blue, respectively. The black dashed line represents the perfect correlation line. (D) Rank the importance of 15 selected features using the random forest algorithm. Maps of (E) CN × ΔHf,x and ΔHf,x+y, and (F) ΔHf,x+y, and M-O bond dissociation energy (BDE) feature pairs for 100 LLZOM compounds considered in our work. Meanwhile, we predicted and plotted 18 unexplored data points, and represented them by yellow crosses and blue crosses. 100 training data points are represented by yellow circles and blue circles. Sky-blue and brown areas represent thermodynamically unstable and stable regions, respectively. Reprinted with permission from Liu et al. (2019). Copyright (2013) Royal Society of Chemistry (Great Britain).

It can be seen from the figure that the larger negative formation energies of oxide MXOy can increase the Li|LLZOM interface thermodynamic stability. The Pauling electronegativity range between 1.0 and 1.5 is more conducive to maintaining the Li|LLZOM interface stability. Therefore, it is concluded that the stronger ionic bonding properties of M-O are beneficial to the thermodynamic stability of the Li|LLZOM interface.

Researchers use the KRR algorithm to quantitatively obtain the prediction model of the reaction energy ΔG. The model uses 80% of the complete data set as training data. The results show that the reaction energy predicted by KRR has both good consistency with the calculated data of DFT and good correlation with related feature statistics as shown in Figure 4C. Therefore, the team developed an exceedingly fast target-driven method by combining high-throughput automated reaction calculations and ML technology. This method can predict the Li|LLZOM interface reaction energy. Other solid electrolyte materials can also easily apply this workflow.

Cathode

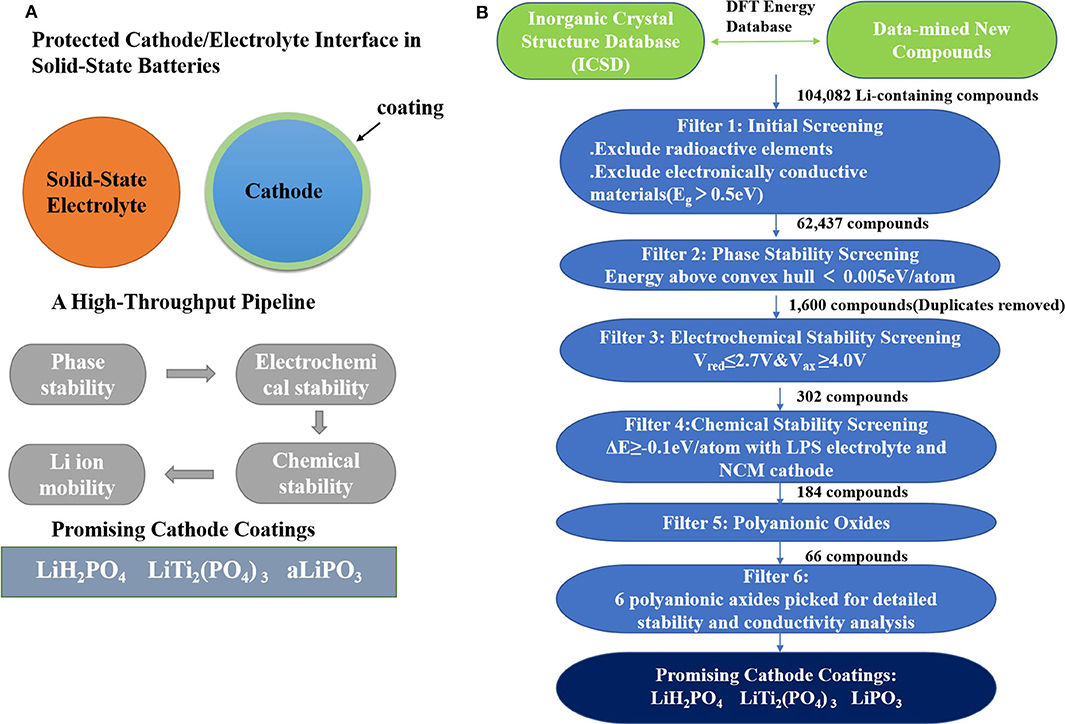

Commercial Li-ion batteries with organic liquid electrolytes have matters of limited electrochemical stability, low ion selectivity, high flammability, and poor stability of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) (Quartarone and Mustarelli, 2011; Zhang et al., 2018b; Ue and Uosaki, 2019). Solid-state batteries (SSBs) (Tateyama et al., 2019) give up using organic liquid electrolytes and use inorganic solid-state electrolytes (SSE) (Lv et al., 2019) instead. Thus, SSBs have the potential to alleviate such problems. However, because of the inter-diffusion, interfacial reaction, and poor contact between electrodes and electrolytes (due to volume changes), solid-state batteries still have high resistance (Takahashi et al., 2014; Takada and Ohno, 2016; Xu et al., 2019a). One way to solve this problem is to find a suitable electrode coating. Xiao et al. (2019) used AI to discover high-throughput screen potential coatings based on phase stability, electrochemical stability, chemical stability, Li-ion mobility, and electronic conductivity. The flow is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. (A) The computational screening schematic diagram of cathode coatings. (B) A flow diagram describes the computational screening of cathode-coating materials.

The following trends were observed after screening:

i Comparing with traditional ternary metal oxide coatings, polyanionic oxides have lower reactivity with thiophosphate electrolytes and higher oxidation limits due to the high covalent nature of oxygen.

ii In general, Li-containing polyanionic oxides have a balance between ionic conductivity and oxidation stability. A high oxidation limit requires a low Li content in the compound. Meanwhile, a high ion conductivity requires a high Li content in the compound.

They conducted further research on six polyanionic oxide coatings. There are excellent chemical and electrochemical stability in lithium borates. However, they may possess poor ionic conductivity at low Li content. In addition, there are three phosphate compounds with good comprehensive properties: LiH2PO4, LiPO3, and LiTi2(PO4)3. They also have excellent application prospects as cathode coating materials in SSB.

Electrolyte

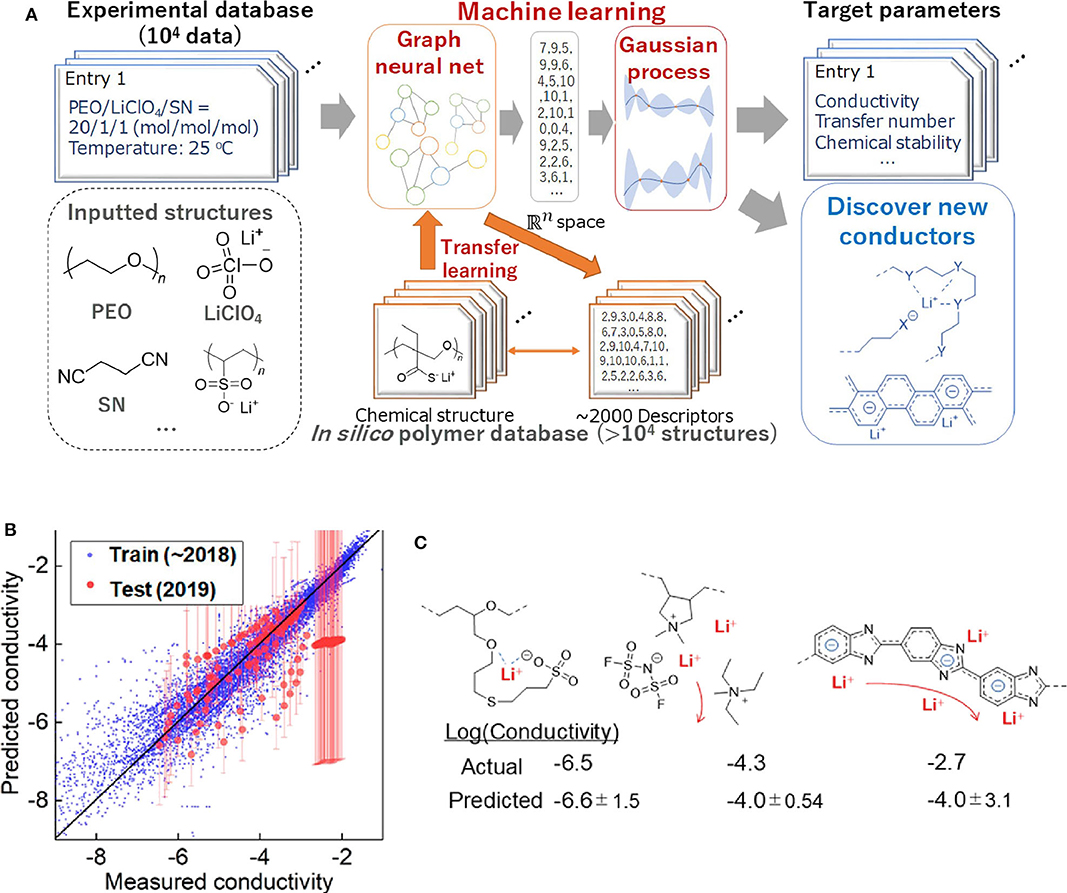

As mentioned previously, commercial Li-ion batteries using organic liquid electrolytes may cause a safety concern. Thus, the discovery of solid electrolytes with excellent performance has become the highlight area of current batteries researches. Polymer-based lithium super ion conductor (Li+-conducting polymer) is a promising solid-state battery material. Although previous studies have shown that various physical factors can affect the diffusion of Li-ion in solids (De Klerk et al., 2016, 2018; Chen et al., 2019a; Xu et al., 2019b) due to the complex interactions (such as orbit coupling and magnetic domain effects), it is still impossible to fully calculate the total conductivity using existing computing capacity. Furthermore, most Li-ion conductors has added polymers, such as plasticizers, which makes the computational process more complex. In order to solve the difficulties of predicting the properties of complex chemical systems, Professor Kenichi Oyaizu's team at Waseda University constructed the largest ML database for Li-ion conductive polymers (Hatakeyama-Sato et al., 2020). This ML database contains comprehensive information on the relationship between chemical structure and conductivity. Their research process of using AI to predict conductivity is shown in Figure 6A. These researchers used conductors reported (up to 2018) to train AI. Then they predicted the conductivity values of ~150 representative conductors that have not been trained by AI which are reported in early 2019. Figure 6B shows the relationship between the measured and predicted values of conductivity. It turns out that most conductors can be predicted correctly. For example, for traditional polyether and aliphatic polymer electrolytes plasticized with ionic liquids, the experimental values and predicted values almost coincided (Figure 6C) (Hatakeyama-Sato et al., 2019; Nag et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019b). This study shows that experiment-oriented ML that can be used to discover promising composites consisting of ordinary chemicals, which can greatly reduce experiment time.

Figure 6. (A) Scheme for using AI to predict the conductivity of the solid polymer electrolytes in this study. (B) Relationship between the measured and predicted conductivity (original units of S/cm, log scale). Training data contained liquids, plasticized/gelled conductors, and solid-state conductors. R2 scores were 0.16 and 0.90 for test and training datasets, respectively. Excluding a polybenzimidazole electrolyte with a conductivity of about −2, the test score would become 0.37. (C) Recently reported polymer-based conductors with example structures and room-temperature conductivity. Reprinted with permission from Hatakeyama-Sato et al. (2020). Copyright (2020) American Chemical Society.

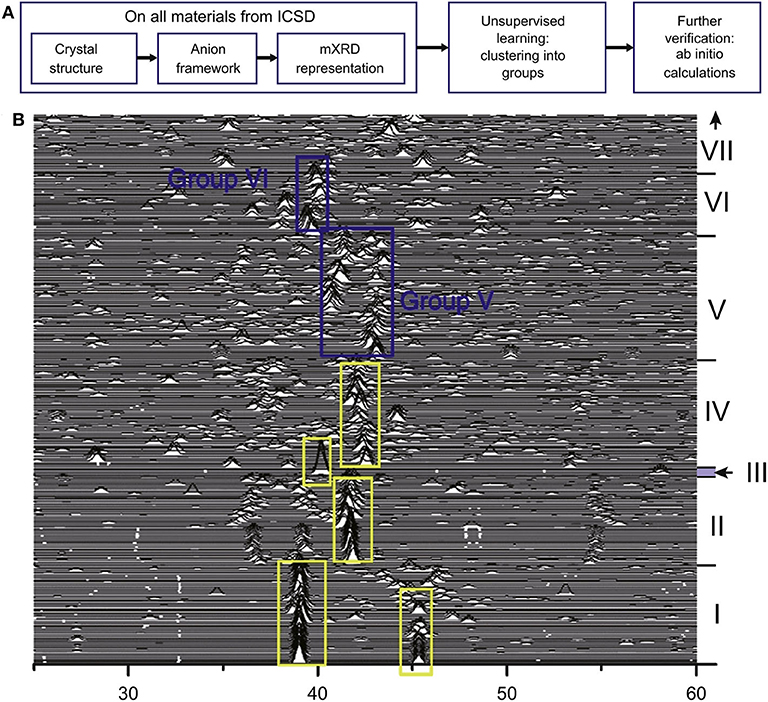

Because the composition-structure space is made up of a huge amount of materials, it is vast and difficult to explore. The number of candidate materials is also limited. Subsequently, the advantages of ML emerge. ML methods can discover complex patterns hiding behind multi-dimensional data. This greatly improves the accuracy and efficiency of exploring new materials. Researchers from the University of Maryland and North American Toyota Research Institute developed a method of unsupervised ML for screening and classifying known Li-containing compounds of the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). The workflow is shown in Figure 7A (Zhang et al., 2019b). In this work, unsupervised machine learning models divide materials into high conductivity group and low ionic conductivity group. In addition, the improved XRD (mXRD), features for the unsupervised model, only consider the anion lattice of the crystal structures. In Figure 7B, the researchers propose that anion lattices of the compounds in groups V and VI with moderate distortion are likely caused by high conductivity of Li-ions, and anion lattice go hand in hand with the disordered Li sublattice. Then, they systematically calculated the Li-ion conductivities of these compounds through high-throughput ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations and obtained sixteen new compounds with σRT higher than 10−4 Scm−1. Among them, σRT of Li8N2Se, Li6KBiO6, and Li5P2N5 reaches 10−2S cm−1.

Figure 7. (A) Workflow of the unsupervised ML for guiding discovery of SSLCs and (B) the modified XRD (mXRD). Reprinted with permission from Zhang et al. (2019b). Copyright (2019) Elsevier.

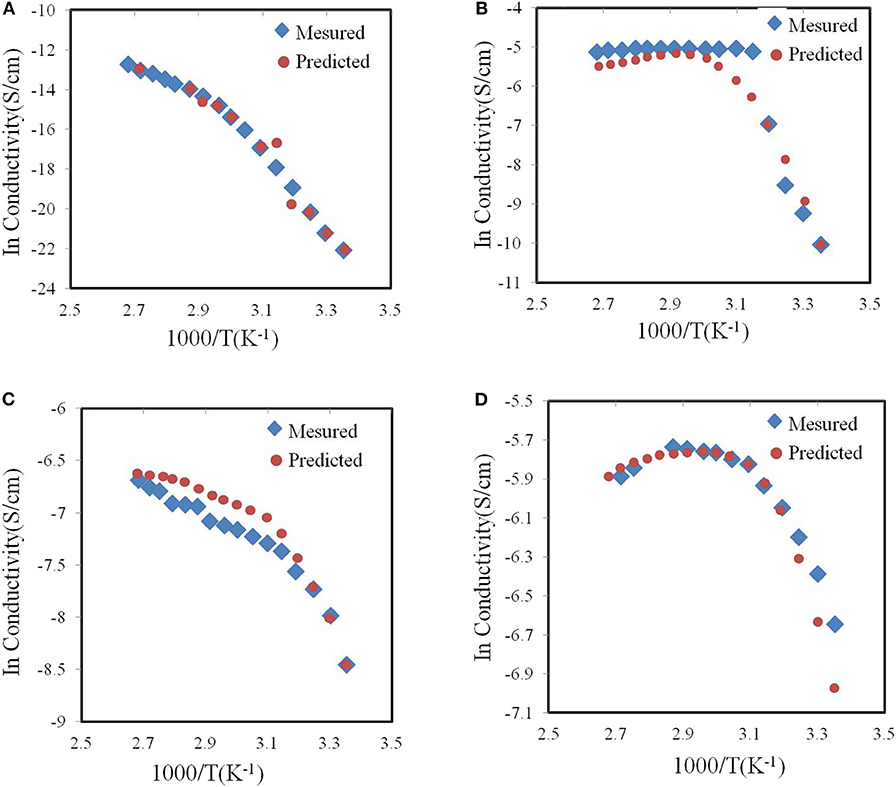

Johan, M.R. and S. Ibrahim used neural networks to optimize the ionic conductivity of the nano-composite solid polymer electrolyte system (Johan and Ibrahim, 2012). In the early days of polymer electrolyte research, many studies focused on the complexity of polyethylene oxide (PEO) and inorganic salts. PEO has become a popular choice for Li-ion conductors polymer matrix. However, the original PEO matrix has low Li-ion conductivity at ambient temperature. Therefore, in the experiment, Johan et al. studied the influence of different ratios of PEO, carbon nanotubes (CNT), lithium hexaflfluorofluorophosphate (LiPF6) and ethylene carbonate (EC) on the ionic conductivity. They used different temperatures and chemical compositions as input data and used the ionic conductivity of the obtained polymer electrolyte as output data to train the neural networks. Finally, they used experimental data to check the accuracy of the neural network after training. As shown in Figure 8, after training, the neural network model can universally well-predict the ionic conductivity of the nanocomposite polymer electrolyte systems (PEO-LiPF6-EC-CNT).

Figure 8. Neural network predicted and experimentally measured curves of (A) pure PEO conductivity (B) pure PEO–Salt conductivity (C) PEO–Salt–EC conductivity and (D) PEO–Salt–EC–CNT conductivity according to temperature.

Conclusions and Perspectives

At present, the long research and development cycle is the most important challenge for the development of new materials. It takes about 20–30 years for a new material to develop from the discovery to the practical application. For products with high requirements, such as aviation equipment, the development time will be longer. There are four reasons for the time-consuming and laborious development of new materials:

(1) The research object is complex.

(2) Researches rely on personal accumulated experience.

(3) The research method is iterative and based on trial and error.

(4) After the development of new materials is completed, it takes a lot of time to determine the production process and operating parameters.

The application of AI to the research and development of materials is a new solution to solve the problem of current long research and development cycle of materials. The ML method can correlate the input and output while ignoring the physical conditions. Therefore, as long as there is enough training data to complete the training of ML, it can find the hidden relations and patterns behind the complex data without wasting attention on the physical details. The autonomous material testing machine with AI can optimize the selection and control of large and complex test parameters, and form closed-loop feedback. Material research, prototyping, testing, validation and lifecycle assessment that used to take a lot of time in the labs can now be done in a virtual laboratory. Thus, it can increase the speed of material development.

However, the use of AI in material research still has certain short-comes. The first problem when using AI for materials discovery is the establishment of a database. The database established by researchers should contain a wide range of material data, such as electronegativity, first ionization energy, chemical bond energy, unit cell parameters, etc. It should also make various data have implicit correlations to form a reticulated knowledge structure. On the one hand, the current database information is fragmented and not comprehensive enough. One solution is to supplement the database with the latest feature data of the materials from unstructured literature. However, how to extract data from unstructured literature automatically, efficiently and accurately is another problem to be solved. On the other hand, how to mine the implicit relationship between various materials feature data is also a problem. After the data is collected, because of its complexity and extensive sources, the error data contained in it is difficult to eliminate. This will affect the accuracy of the model. How to establish a database correction and screening mechanism is also one of the problems. In the process of data analysis and prediction, the standard ML methods are essentially a form of data interpolation. The new unseen data which we get from labeled data is essentially resulting from interpolating the previously available examples. Technically, the test examples (unseen examples) are assumed from the same probability distribution of the training examples (Zhang et al., 2018b). However, during the research process, scientists usually hope that the trained ML can predict data outside the training set, which is also a problem. Therefore, although material calculation and simulation can effectively reduce development time, it is still less than a substitute for experimental verification. In the future, attempting to draw on the methods of feature engineering in the computer field to eliminate incomplete, inconsistent and out of expectations noise data, and using transfer learning technology to improve the applicable range of prediction models may be two possible ways to solve various data set problems. In addition, integration of multiple complementary AI technologies (such as ML, reasoning, planning, search, and knowledge representation), as well as the development of superconductors (Zhang et al., 2015) and the synthesis of ultra-fast nanoparticles (Chen et al., 2016a,b,c, 2017, 2019b), can further accelerate the research and development of materials science.

Author Contributions

YW, XZ, and YD conceived of the presented idea. ZL and XY completed the main body of the article. SL, WL, and JX collected data and literature. WH, HZ, and JT proposed constructive amendments to the article. YZ made pictures and applied for copyright. SD, KX, and ZH checked and revised the grammar. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Ajay, K. M., and Dinesh, M. N. (2018). “Dinesh: influence of various activated carbon based electrode materials in the performance of super capacitor,” in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Bengaluru), 310. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/310/1/012083

Arroyo-de Dompablo, M. E., Marianetti, C., Van der Ven, A., and Ceder, G. (2001). Jahn-Teller mediated ordering in layered LixMO2 compounds. Phys. Rev. B. 63:14. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.63.144107

Attia, P. M., Grover, A., Jin, N., Severson, K. A., Markov, T. M., Liao, Y. H., et al. (2020). Closed-loop optimization of fast-charging protocols for batteries with machine learning. Nature 278, 397–402. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1994-5

Berrueta, A., Ursúa, A., San Martín, I., Eftekhari, A., and Sanchis, P. (2019). Supercapacitors:electrical characteristics, modeling, applications, and future trends. IEEE Access 7:50869. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2908558

Butler, K. T., Davies, D. W., Cartwright, H., Isayev, O., and Walsh, A. (2018). Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 559, 547–555. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0337-2

Chen, D., Jie, J., Weng, M., Li, S., Chen, D., Pan, F., et al. (2019a). High throughput identification of Li ion diffusion pathways in typical solid state electrolytes and electrode materials by BV-Ewald method. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 1300–1306. doi: 10.1039/C8TA09345H

Chen, Y., Egan, G. C., Wan, J., Zhu, S., Jacob, R. J., Zhou, W., et al. (2016a). Ultra-fast self-assembly and stabilization of reactive nanoparticles in reduced graphene oxide films. Nat. Commun. 7:12332. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12332

Chen, Y., Fu, K., Zhu, S., Luo, W., Wang, Y., Li, Y., et al. (2016c). Reduced graphene oxide films with ultrahigh conductivity as Li-ion battery current collectors. Nano Lett. 16, 3616–3623. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b00743

Chen, Y., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Fu, K., Danner, V. A., Dai, J., et al. (2016b). Rapid, in situ synthesis of high capacity battery anodes through high temperature radiation-based thermal shock. Nano Lett. 16, 5553–5558. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02096

Chen, Y., Xu, S., Li, Y., Jacob, R. J., Kuang, Y., Liu, B., et al. (2017). FeS2 nanoparticles embedded in reduced graphene oxide toward robust, high-performance electrocatalysts. Adv. Energy Mater. 7:19. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201700482

Chen, Y., Xu, S., Zhu, S., Jacob, R. J., Pastel, G., Wang, Y., et al. (2019b). Millisecond synthesis of CoS nanoparticles for highly efficient overall water splitting. Nano Res. 12, 2259–2267. doi: 10.1007/s12274-019-2304-0

Cheng, X., Liu, M., Yin, J., Ma, C., Dai, Y., Wang, D., et al. (2020). Regulating surface and grain boundary structures of Ni-rich layered cathodes for ultrahigh cycle stability. Small 16, 16–13. doi: 10.1002/smll.201906433

De Klerk, N. J., Rosło,n, I., and Wagemaker, M. (2016). Diffusion mechanism of Li argyrodite solid electrolytes for li-ion batteries and prediction of optimized halogen doping: the effect of Li vacancies, halogens, and halogen disorder. Chem. Mater. 28, 7955–7963. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b03630

De Klerk, N. J. J., van der Maas, E., and Wagemaker, M. (2018). Analysis of diffusion in solid-state electrolytes through MD simulations, improvement of the Li-ion conductivity in β-Li3PS4 as an example. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 3230–3242. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.8b00457

Du, T., Li, A., Ma, J., and Liu, F. (2015). Research progress of SOC estimation of power battery. Chinese J. Power Sour. 39, 844–845.

Eliad, L., Salitra, G., Soffer, A., and Aurbach, D. (2001). Ion sieving effects in the electrical double layer of porous carbon electrodes: estimating effective ion size in electrolytic solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 105, 6880–6887. doi: 10.1021/jp010086y

Ezeigwe, E. R., Khiew, P. S., Siong, C. W., and Tan, M. T. (2020). Mesoporous Zinc–Nickel–Cobalt nanocomposites anchored on graphene as electrodes for electrochemical capacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 816:152646. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.152646

Flamand, E., Rossi, D., Conti, F., Loi, I., Pullini, A., Rotenberg, F., et al. (2018). “GAP-8: A RISC-V SoC for AI at the edge of the IoT,” in IEEE International Conference on Application-Specific Systems Architectures and Processors, 67–72. doi: 10.1109/ASAP.2018.8445101

Ghosh, A., and Lee, Y. H. (2012). Carbon-based electrochemical capacitors. ChemSusChem. 5, 480–499. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201100645

Giménez, M., Palanca, J., and Botti, V. (2020). Semantic-based padding in convolutional neural networks for improving the performance in natural language processing. A case of study in sentiment analysis. Neurocomputing. 378, 315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2019.08.096

Groenitz, H. (2018). Logistic regression analyses for indirect data. Commun. Statist. Theory Methods 47, 3838–3856. doi: 10.1080/03610926.2017.1364387

Hasegawa, G., Kanamori, K., Nakanishi, K., and Abe, T. (2012). New insights into the relationship between micropore properties, ionic sizes, and electric double-layer capacitance in monolithic carbon electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 26197–26203. doi: 10.1021/jp309010p

Hatakeyama-Sato, K., Tezuka, T., Nishikitani, Y., Nishide, H., and Oyaizu, K. (2019). Synthesis of lithium-ion conducting polymers designed by machine learning-based prediction and screening. Chem. Lett. 48, 130–132. doi: 10.1246/cl.180847

Hatakeyama-Sato, K., Tezuka, T., Umeki, M., and Oyaizu, K. (2020). AI-assisted exploration of superionic glass-type Li+ conductors with aromatic structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3301–3305. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b11442

Johan, M.R., and Ibrahim, S. (2012). Optimization of neural network for ionic conductivity of nanocomposite solid polymer electrolyte system (PEO-LiPF6-EC-CNT). Commun. Nonlin. Sci. Numer. Simul. 17, 329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2011.04.017

Kim, H. (2019). AI, big data, and robots for the evolution of biotechnology. Genomics Inform. 17:44. doi: 10.5808/GI.2019.17.4.e44

Li, S., He, H., and Li, J. (2019). Big data driven lithium-ion battery modeling method based on SDAE-ELM algorithm and data pre-processing technology. Appl. Energy 242, 1259–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.03.154

Liang, Z., Zhao, R., Qiu, T., Zou, R., and Xu, Q. (2019). Metal-organic framework-derived materials for electrochemical energy applications. EnergyChem. 1:100001. doi: 10.1016/j.enchem.2019.100001

Liu, B., Yang, J., Yang, H., Ye, C., Mao, Y., Wang, J., et al. (2019). Rationalizing the interphase stability of Li|doped-Li7La3Zr2O12 via automated reaction screening and machine learning. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 19961–19969. doi: 10.1039/C9TA06748E

Liu, Y., Wang, J., Wu, J., Ding, Z., Yao, P., Zhang, S., et al. (2020). 3D cube-maze-like Li-rich layered cathodes assembled from 2D porous nanosheets for enhanced cycle stability and rate capability of lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 10:5. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201903139

Lv, F., Wang, Z., Shi, L., Zhu, J., Edström, K., Mindemark, J., et al. (2019). Challenges and development of composite solid-state electrolytes for high-performance lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources. 441. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.227175

Mehta, V. H., and Straubel, J. B. (2009). Fast Charging With Negative Ramped Current Profile. US20090651246. Palo Alto, CA: Tesla Motors, Inc.

Miller, D. D. (2020). Machine Intelligence in Cardiovascular Medicine. Cardiol. Rev. 28, 53–64. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000294

Min, K. J., Bin, S. S., Sick, J. J., Seok, L. M., Dmitry, G., Green, B., et al. (2016). Battery charging method and battery pack using the same. US201615006883.

Nag, A., Asif Ali, M., Singh, A., Vedarajan, R., Matsumi, N., and Kaneko, T. (2019). N-Boronated polybenzimidazole for composite electrolyte design of highly ion conducting pseudo solid-state ion gel electrolytes with a high Li-transference number. J. Mater. Chem. A. 7, 4459–4468. doi: 10.1039/C8TA10476J

Notten, P. H., het Veld, J. O., and Van Beek, J. R. G. (2005). Boostcharging Li-ion batteries: a challenging new charging concept. J. Power Sources. 145, 89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2004.12.038

Paryani, A. (2009). Low Temperature Charging of Li-Ion Cells. US12570640. Palo Alto, CA: Tesla Motors, Inc.

Quartarone, E., and Mustarelli, P. (2011). Electrolytes for solid-state lithium rechargeable batteries: recent advances and perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 2525–2540. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00081g

Rehman, Y. A. U., Po, L. M., and Liu, M. (2020). SLNet: Stereo face liveness detection via dynamic disparity-maps and convolutional neural network. Expert Systems With Appl. 142, 182–193. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2019.113002

Samsonovich, A. V. (2020). Socially emotional brain-inspired cognitive architecture framework for artificial intelligence. Cogn. Syst. Res. 60, 57–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cogsys.2019.12.002

Song, K., Wang, X., Li, J., Zhang, B., Yang, R., Liu, P., et al. (2020). 3D hierarchical CoFe2O4/CoOOH nanowire arrays on Ni-Sponge for high-performance flexible supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta. 340. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2020.135892

Stoller, M. D., and Ruoff, R. S. (2010). Best practice methods for determining an electrode material's performance for ultracapacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1294–1301. doi: 10.1039/c0ee00074d

Su, H., Lin, S., Deng, S., Lian, C., Shang, Y., and Liu, H. (2019). Predicting the capacitance of carbon-based electric double layer capacitors by machine learning. Nanoscale Adv. 1, 2162–2166. doi: 10.1039/C9NA00105K

Takada, K., and Ohno, T. (2016). Experimental and computational approaches to interfacial resistance in solid-state batteries. Front. Energy Res. 4. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2016.00010

Takahashi, K., Maekawa, H., and Takamura, H. (2014). Effects of intermediate layer on interfacial resistance for all-solid-state lithium batteries using lithium borohydride. Solid State Ionics. 262, 179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2013.10.028

Tateyama, Y., Gao, B., Jalem, R., and Haruyama, J. (2019). Theoretical picture of positive electrode–solid electrolyte interface in all-solid-state battery from electrochemistry and semiconductor physics viewpoints. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 17, 149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.coelec.2019.06.003

Travis-Lumer, Y., and Goldberg, Y. (2015). Support vector machines for current status data statistics. arXiv:1505.00991.

Turing, A. (2006). The essential turing: the ideas that gave birth to the computer age. Br. J. Hist. Sci. 39, 470–471. doi: 10.1017/S0007087406448688

Ue, M., and Uosaki, K. (2019). Recent progress in liquid electrolytes for lithium metal batteries. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 17, 106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.coelec.2019.05.001

Van der Ven, A., and Ceder, G. (2001). Lithium diffusion mechanisms in layered intercalation compounds. J. Power Sources 97–98, 529–531. doi: 10.1016/S0378-7753(01)00638-3

Van der Ven, A., Ceder, G., Asta, M., and Tepesch, PD. (2001). First-principles theory of ionic diffusion with nondilute carriers. Phys. Rev. B. 64:18. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.64.184307

Van der Ven, A., Marianetti, C., Morgan, D., and Ceder, G. (2000). Phase transformations and volume changes in spinel LixMn2O4. Solid State Ionics. 135, 21–32. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2738(00)00326-X

Westreich, D., Lessler, J., and Funk, M. J. (2010). Propensity score estimation: neural networks, support vector machines, decision trees (CART), and meta-classifiers as alternatives to logistic regression. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63, 826–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.020

Xiao, Y., Miara, L. J., Wang, Y., and Ceder, G. (2019). Computational screening of cathode coatings for solid-state batteries. Joule 3, 1252–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2019.02.006

Xu, J., Gao, B., Huo, K. F., and Chu, P. K. (2020). Recent progress in electrode materials for nonaqueous lithium-ion capacitors. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 20, 2652–2667. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2020.17475

Xu, P., Rheinheimer, W., Shuvo, S. N., Qi, Z., Levit, O., Wang, H., et al. (2019a). Origin of high interfacial resistances in solid-state batteries: interdiffusion and amorphous film formation in li0.33La0.57TiO3/LiMn2O4 Half Cells. ChemElectroChem. 6, 4576–4585. doi: 10.1002/celc.201901068

Xu, Z., Chen, X., Liu, K., Chen, R., Zeng, X., and Zhu, H. (2019b). Influence of anion charge on li ion diffusion in a new solid-state electrolyte, Li3LaI6. Chemistry of Materials. 31, 7425–7433. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b02075

Xueliang, X. (2017). The development and status of artificial neural network. Microelectronics. 47, 239–242.

Yan, Y., Wang, T., Li, X., Pang, H., and Xue, H. (2017). Noble metal-based materials in high-performance supercapacitors. Inorganic Chem. Front. 4, 33–51. doi: 10.1039/C6QI00199H

Yang, C., Lv, F., Zhang, Y., Wen, J., Dong, K., Su, H., et al. (2019a). Confined Fe2VO4 subset of nitrogen-doped carbon nanowires with internal void space for high-rate and ultrastable potassium-ion storage. Adv. Energy Mater. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201902674

Yang, K., Liao, Z., Zhang, Z., Yang, L., and Hirano, S-.I. (2019b). Ionic plastic crystal-polymeric ionic liquid solid-state electrolytes with high ionic conductivity for lithium ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 236, 554–557. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2018.11.003

Zhang, L., Li, Q., Xue, H., and Pang, H. (2019a). Fabrication of Cu2O-based materials for lithium-ion batteries. ChemSusChem 11, 1581–1599. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201702325

Zhang, M., Tao, S., Huang, W., Song, L., Wu, Z., and Chu, W. (2015). An ab initio study for electrochemistry: Superconductor layer FeAs as a novel anode material for lithium ion batteries. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. China 45, 353–358.

Zhang, Q., Zhang, D., Miao, Z., Zhang, X., and Chou, S. (2018a). Research progress in MnO2 -carbon based supercapacitor electrode materials. Small 14:24. doi: 10.1002/smll.201702883

Zhang, S. S. (2006). The effect of the charging protocol on the cycle life of a Li-ion battery. J. Power Sources. 161, 1385–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.06.040

Zhang, X., Tang, B., and Zhou, Z. (2019b). Unsupervised machine learning accelerates solid electrolyte discovery. Green Energy Environ. doi: 10.1016/j.gee.2019.12.003

Zhang, X. Q., Zhao, C. Z., Huang, J. Q., and Zhang, Q. (2018b). Recent advances in energy chemical engineering of next-generation lithium batteries. Engineering. 4, 831–847. doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2018.10.008

Keywords: artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, energy storage, energy materials

Citation: Luo Z, Yang X, Wang Y, Liu W, Liu S, Zhu Y, Huang Z, Zhang H, Dou S, Xu J, Tian J, Xu K, Zhang X, Hu W and Deng Y (2020) A Survey of Artificial Intelligence Techniques Applied in Energy Storage Materials R&D. Front. Energy Res. 8:116. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2020.00116

Received: 25 March 2020; Accepted: 15 May 2020;

Published: 03 July 2020.

Edited by:

Zhanxi Fan, City University of Hong Kong, Hong KongCopyright © 2020 Luo, Yang, Wang, Liu, Liu, Zhu, Huang, Zhang, Dou, Xu, Tian, Xu, Zhang, Hu and Deng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yingxue Wang, d2FuZ3lpbmd4dWVAY3Nkc2xhYi5uZXQ=; Xiaowang Zhang, eGlhb3dhbmd6aGFuZ0B0anUuZWR1LmNu; Wenbin Hu, d2JodUB0anUuZWR1LmNu; Yida Deng, eWlkYS5kZW5nQHRqdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Ziyi Luo1†

Ziyi Luo1† Xinyi Yang

Xinyi Yang Yingxue Wang

Yingxue Wang Weidi Liu

Weidi Liu Yida Deng

Yida Deng