- Department of Chemistry, Indian Institute of Technology Patna, Patna, India

A set of five nanoporous (pore size <100 nm) amine-functionalized and triptycene-based organic polymers (TBPALs) were prepared using commercially available phenols (such as quinol and phloroglucinol) and triptycene amines. C–N bonds were formed in the polymerization reactions without employing transitional metal catalysts such as PdII or CuI. TBPALs demonstrated their ability to reversibly capture small gas molecules such as CO2, H2, CH4, and H2. Highest uptake of CO2 and H2 was observed for TBPAL2 at 163.7 mg g−1 (273 K) and 16.2 mg g−1 (77 K), respectively.

Introduction

Design and improvement of porous materials' properties is a frontier research area. Porous materials have versatile applications that include selective adsorption of small gas molecules for their separation or storage (Mondal and Das, 2015; Mane et al., 2017), catalysis (Huang et al., 2018), chemosensing (Gu et al., 2017), energy storage (Liao et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018), and several others (Bhanja et al., 2017; Liu and Liu, 2017; Mitra et al., 2017; Bera et al., 2018a). Metal organic frameworks (MOFs) are porous materials that utilize metal–ligand coordination bonds to stitch monomers to yield coordination polymers. In the past few decades, the scientific community has witnessed extensive research effort in the development of novel porous materials that are derived from purely organic monomers (Cong et al., 2015; Trickett et al., 2017). The resulting materials are best described as porous organic polymers (POPs) or porous organic frameworks (POFs). POPs/POFs are thus synthesized utilizing organic monomers containing lightweight, non-metallic elements (Zhang et al., 2018). The monomers are linked by strong covalent bonds, thereby imparting strength and high thermal/chemical stability to the resulting polymeric materials (Wu et al., 2019). MOFs on the other hand have relatively higher sensitivity to acid/base (lower chemical stability) since monomers (in MOFs) are linked via coordination bonds. Additionally, thermal stability of MOFs is relatively less than POPs/POFs because of the lower strength of ion–dipole interactions (ca. 200–50 kJ mol−1) in the former (MOFs) than covalent bonds (ca. 200–350 kJ mol−1) in the latter (COFs). For superior gas storage applications, it is expected that POPs are microporous in nature. These are also known as MOPs (microporous organic polymers) and polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs) to indicate that the pore widths do not exceed 2 nm (micropores) (Sing, 1985). In current research, there has been a growth in design and construction of microporous organic polymeric materials for potential use in gas separation and storage, as sensors or as catalysts (Das et al., 2017; Dey et al., 2017). In general, polymeric materials that are obtained from rigid monomers (with limited conformational freedom) contain sufficient micropores. The resulting polymers are also highly robust and rigid. The observed microporosity is due to the inefficient packing of the rigid three-dimensional (3D) building blocks that generate voids. Triptycene, the smallest member of the iptycene family, is an example of such a rigid molecular unit with a unique paddle-wheel like arrangement of three phenyl rings fused via a bicyclo[2.2.2]octane unit. As a result, triptycene-based polymers have “internal molecular free volume (IMFV)” and these porous 3D polymeric materials have large surface area and thermal stability (Swager, 2008; Zhang et al., 2016). One of the most promising application of POPs is their potential as sorbent for selective capture of CO2 gas. This is important because CO2 being a greenhouse gas is recognized as major contributor to global warming and ocean acidification. One prerequisite desirable in a good CO2 adsorbent is inclusion of sufficient CO2-philic sites in the surface of the material. Furthermore, it is well-acknowledged that CO2-philicity of a POP may be enhanced if the skeletal framework includes nitrogen-based functional groups. Literature reports indicated that porous and nitrogen-rich organic polymer networks have relatively better affinity and comparatively more selectivity toward carbon dioxide over other gases (Shuangzhi et al., 2016). One may attribute this to favorable acid–base interactions between acidic CO2 molecules and basic N centers with a lone pair of electron. Various synthetic strategies have been utilized to yield N-rich POPs such as use of N-heterocycle-based monomers or amine-based monomers. However, to the best of our knowledge, porous polymers with amine linkages (–NH–) have not been explored for applications such as selective capture of CO2 or reversible storage of H2. Synthetic protocols for obtaining such amine (–NH–) cross-linked polymeric networks should be preferentially environmentally benign and avoid use of hazardous reagents or expensive transition metal-based catalysts (Patel et al., 2013). Polymeric materials with aromatic rings connected via amine bridges have been prepared via metal-catalyzed strategies such as the Buchwald–Hartwig (BH) coupling [Pd(II) based catalysts] or Ullmann method [catalytic Cu(I)] to form C–N bonds (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2018). A greener approach would be to avoid use of transition metal-based catalysts to yield such polymers in which aromatic rings are connected via amine groups.

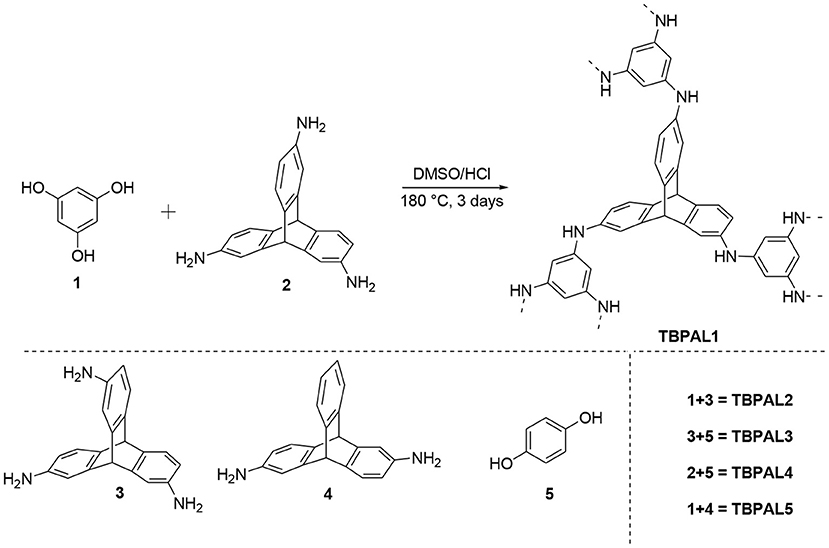

In this present work, we report synthesis of a set of unique triptycene based POPs with amine linkers (TBPALs) without the use of metal-based catalysts. The objective was to obtain amine group containing polymeric materials as amine functional groups are known to play a significant role in improving the interaction of polymeric materials and CO2 molecules. The synthetic protocol is facile since it involves condensation of amine (triptycene based triamine/diamine) and inexpensive phenols (such as phloroglucinol/hydroquinone) to yield a set of new nuclophilic amine functionalized polymers (TBPALs). These polymeric materials (TBPAL1–5) have been conveniently synthesized via condensation of triptycene-based triamine/diamine molecules with commercially available and inexpensive phenols such as phloroglucinol/hydroquinone. Following structural characterization, we have recorded their surface area and porous properties. Results obtained were compared with literature-reported POPs that are rich in nitrogen. The performance of TBPAL1–5 as adsorbent for CO2 was also recorded. To the best of our knowledge, TBPAL1, 2, and 3 display significantly better CO2/N2 selectivity at both 273 and 298 K when compared with several nitrogen-rich networks reported to date.

Experimental Section

Materials

Triptycene, phloroglucinol, and hydroquinone were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and were used as obtained. 2,6-Diaminotriptycene, 2,6,14-, and 2,7,14-triaminotriptycene were synthesized using literature-reported procedure (Zhang and Chen, 2006; Chen and Swager, 2008).

Instrumentation

Solid-state 13C cross-polarization magic angle spinning (CPMAS 13C NMR) NMR spectra of TBPAL1–5 were recorded on a Bruker 400 spectrometer equipped with a 89-mm-wide bore and a 9.4 T superconducting magnet with a spinning rate of 12 kHz and CP contact time of 2 ms with a delay time of 2 s. Shimadzu IR Affinity-1 spectrometer was used to record FTIR spectra. P-XRD analyses were obtained using a Rigaku TTRAX III X-ray diffractometer. TGA data were obtained using TG-DSC, STA 449 F3 Jupiter NETZSCH, Selb, Germany, at a scan rate of 10°C/min under nitrogen flow (100 ml/min). FESEM data were recorded using a Carl Zeiss AG Instrument (Model—SUPRA 55). Porosity and surface area data were recorded using Quantachrome Autosorb iQ2 analyzer. In a typical gas experimental setup, TBPALs (80–120 mg) were charged in a 9-mm cell and were subjected to degassing at 120°C for 5–8 h by attaching to the degassing unit. The cells containing the degassed polymeric samples were refilled with helium gas and weighed accurately. Subsequently, cells were reattached to the analysis unit of the instrument for measurements. Various temperatures of the analysis unit sample cell were maintained using KGW isotherm bath that was filled with liquid N2 (77 K) or temperature-controlled bath (298 and 273 K).

General Procedure for Synthesis of TBPALs

A typical experiment for the syntheses of TBPALs (Scheme 1) is described using TBPAL1 as a representative example. Phloroglucinol (85 mg, 0.67 mmol) and 2,6,14-triaminotriptycene (200 mg, 0.67 mmol) were charged in a Schlenk flask fitted with a condenser. Subsequently, DMSO (10 ml) and HCl (20 μl) were added to the reaction flask and the mixture was heated under an N2 atmosphere at 180°C for 3 days. After cooling to room temperature, the precipitated product was filtered and washed with organic solvents (THF, methanol, DMSO, water, acetone, DCM, chloroform, and diethyl ether). This was followed by drying the products (under reduced pressure at 120°C) that were finally obtained as a brown powder in 85% yield (210 mg).

Synthesis of TBPAL2: TBPAL2 has been synthesized following a similar method as described for TBPAL1 using phloroglucinol (85 mg, 0.67 mmol) and 2,7,14-triaminotriptycene (200 mg, 0.67 mmol) as monomers. After drying at a reduced pressure at 120°C, the final product was obtained as a brown powder (205 mg, 83% yields).

Synthesis of TBPAL3: TBPAL3 has been synthesized following a similar method to that described for TBPAL1 using hydroquinone (110 mg, 1.0 mmol) and 2,7,14-triaminotriptycene (200 mg, 0.67 mmol). Yield: 228 mg, 83%.

Synthesis of TBPAL4: TBPAL4 has been synthesized following a similar method to that described for TBPAL1 using hydroquinone (110 mg, 1.0 mmol) and 2,6,14-triaminotriptycene (200 mg, 0.67 mmol). Yield: 239 mg, 87%.

Synthesis of TBPAL5: TBPAL5 has been synthesized following a similar method to that described for TBPAL1 using phloroglucinol (60 mg, 0.47 mmol) and 2,6-diaminotriptycene (200 mg, 0.7 mmol). Yield: 210 mg, 90%.

Characterization

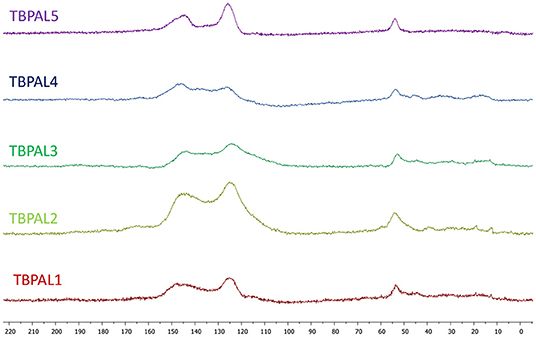

Solid-state 13C CPMAS NMR spectra of TBPAL1–5 were recorded and these exhibited the signature peak of triptycene motif at 52 ppm that is assigned to its bridgehead carbon (Deng and Wang, 2017). This peak is characteristic of the triptycene motif and its presence in the spectrum confirms its successful incorporation in the polymeric product. The broad peaks with chemical shifts in the range 125 and 145 ppm are assigned to the aromatic carbon atoms in triptycene units and aryl rings (phloroglucinol/hydroquinone) that are incorporated in the polymeric network (Figure 1). In these 13C CPMAS NMR spectra (of TBPAL1–5), the broad signal at 125 ppm is due to the carbon nuclei that are bonded to carbon/hydrogen centers, while the other broad signal at 145 ppm is assigned to those carbon nuclei that are covalently linked to nitrogen centers (Figure S1).

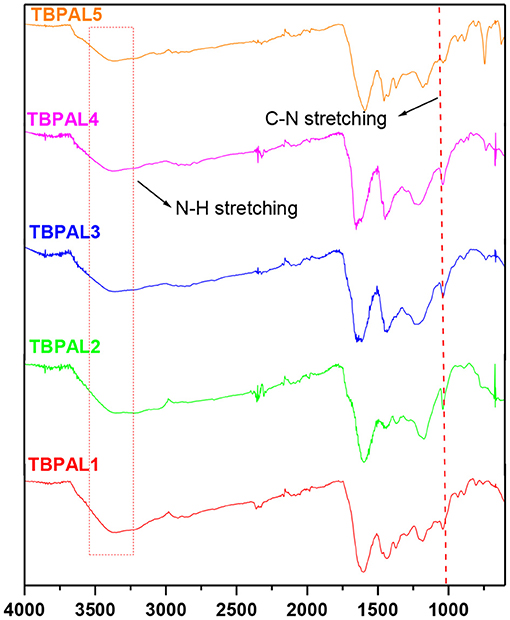

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectral analysis also supported formation of TBPALs (Figure 2). In the FTIR spectra, the bands expected due to the secondary amino group appear in between the range of 3,090 and 3,600 cm−1 (N–H stretching). The C–N stretching vibration bands were centered at 1,020 cm−1. Additionally, the bands due to aromatic C = C stretching for the aromatic rings and the N–H bending appeared in the range 1,500 to 1,700 cm−1.

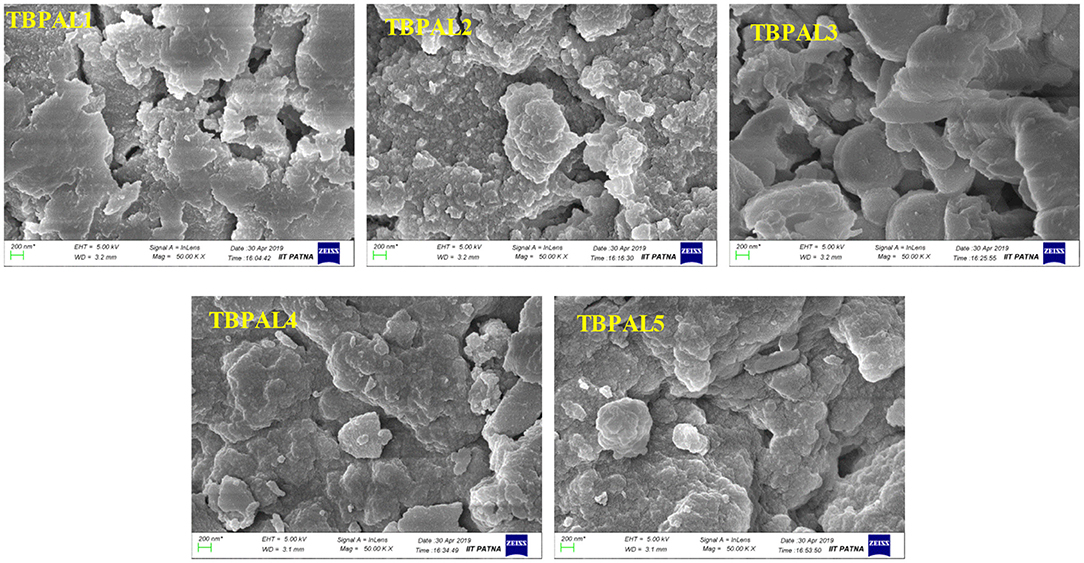

The field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images show amorphous morphology with a large number of pores on the surface of TBPALs, which may be due to cross-linking of amine functional groups in rapid and random manner across the polymer framework (Figure 3).

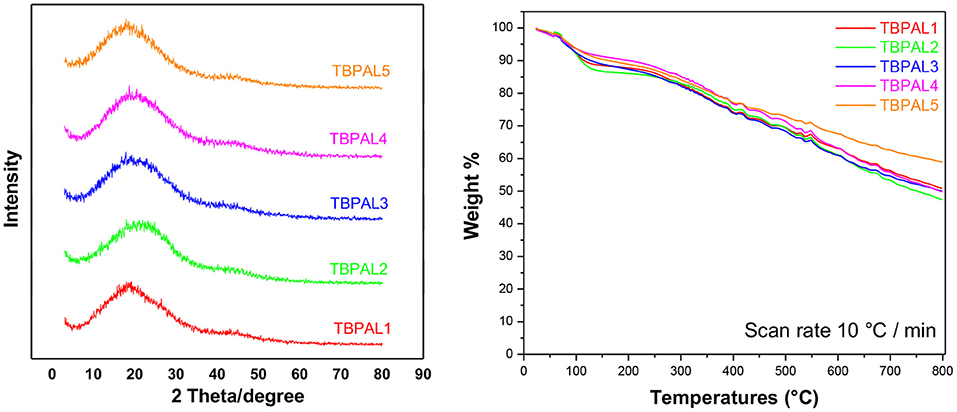

Wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) spectra (Figure 4) of TBPALs with featureless broad diffraction pattern indicated that these porous polymeric materials are amorphous in nature since sharp peaks were absent. The inclusion of rigid and robust triptycene units in the backbone of these TBPALs is known to inhibit efficient packing and this leads to loss of crystallinity in TBPALs. TGA (thermogravimetric analysis) was used to estimate the thermal stability of TBPALs under nitrogen atmosphere up to 800°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min (Figure 4). TBPALs are highly thermally stable as evident from the observed char yields at 800°C that was >50%. The observed high thermal stability may be attributed to the presence of robust triptycene units in the polymer framework.

Result and Discussion

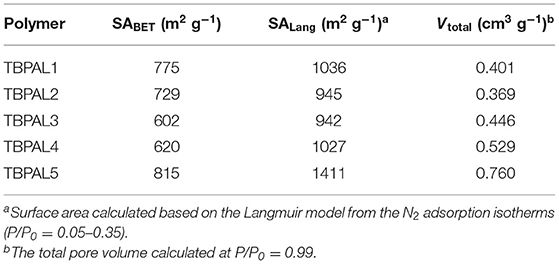

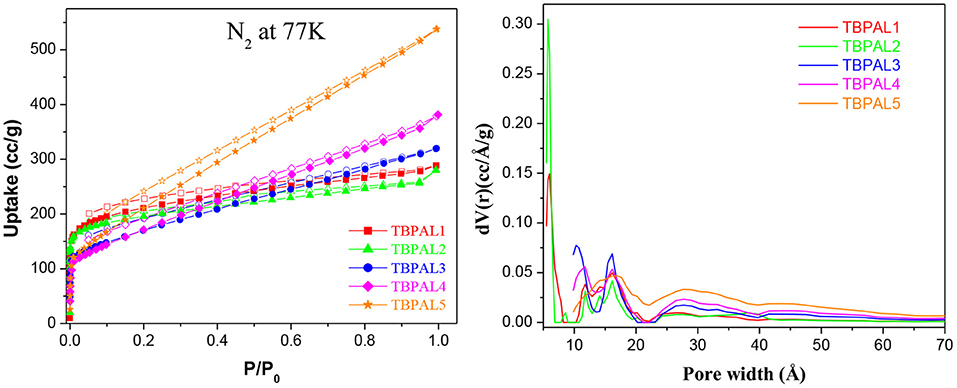

Using nitrogen sorption isotherms (collected at 77 K, Figure 5), the surface area and porosity of the TBPALs were estimated. TBPALs demonstrate substantial N2 adsorption in the low relative pressure range (P/P0 = 0–0.01). This suggests that TBPAL1–5 have abundant micropores. In addition, moderately high increase in nitrogen uptake at medium- to high-pressure region advocates the presence of macropores in these TBPALs (Zhang et al., 2014). The surface areas (SAs) of TBPALs were measured using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) model (Table 1 and Figure S2). The SABET obtained for TBPAL1, TBPAL2, TBPAL3, TBPAL4, and TBPAL5 are 775, 729, 602, 620, and 815 m2 g−1, respectively. The corresponding Langmuir surface areas are 1,036, 945, 942, 1,027, and 1,411 m2 g−1, respectively (Table 1 and Figure S3). In case of all TBPALs, the hysteresis loop in the respective sorption branches remain almost parallel over a considerable range of P/P0. This implies that TBPALs display type H4 adsorption–desorption hysteresis.

Figure 5. N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm at 77 K (left) and pore size distribution (right) of TBPALs.

According to IUPAC, “the type H4 loop appears to be associated with narrow slit-like pores” (Sing, 1982). A comparison with previously reported microporous materials clearly indicates that integration of triptycene units in polymeric framework with amine linkers yield TBPALs that are considerably porous. Additionally, the respective surface areas (SABET) are reasonably better or comparable than various previously literature reported nitrogen-rich porous materials. Representative examples of microporous materials with relatively lesser SABET than TBPALs are imine-POP (194 m2 g−1) (Yu et al., 2018), pyrene-based conjugated POPs (105–136 m2 g−1) (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2018), benzidine-based adsorbent material (100 m2 g−1) (Taskin et al., 2016), amine-based cross-linked porous polymer (305 m2 g−1) (Mahmoud Abdelnaby et al., 2018), g-C3N4-doped amine-rich POP (368–540 m2 g−1) (Ou et al., 2018) porous aromatic networks with amine linkers (178–204 m2 g−1) (Li et al., 2019), polyethylenimine (PEI)-linked MOPs (65–101 m2 g−1) (Mane et al., 2018), phthalocyanine nanoporous polymer (579 m2 g−1) (Neti et al., 2015) cyanate resin networks (PCN-TPC, PCN-TPPC, 662–686 m2 g−1) (Deng and Wang, 2017), azo-functionalized MOPs (335–706 m2 g−1) (Yang et al., 2015), porous polymers derived from Tröger's base (TB-MOP, 694 m2 g−1) (Zhu et al., 2013), as well as other MOPs such as triptycene-based polymeric nanosheet (2D-PTNS) (690 m2 g−1) (Chen et al., 2017), triptycene-based hexakis (metalsalphens) (356–427 m2 g−1) (Reinhard et al., 2018), and BODIPY-containing POPs (482–725 m2 g−1) (Xu et al., 2016a).

Pore dimensions of TBPALs were estimated using the N2 sorption isotherms and by using the density functional theory (DFT) method. Pore size distribution (PSD) profile of TBPALs (Figure 5) reveals that these polymeric networks have pores that are microporous (<2 nm) as well as mesoporous (2–50 nm). Only in the case of TBPAL1 and TBPAL2 have we observed the presence of ultramicropores (<0.7 nm). Moreover, in the case of TBPAL2, there is a greater distribution of narrow ultramicropores than TBPAL1 (Figure S4). Total pore volume of TBPALs was calculated from the volume of N2 adsorbed at a P/P0 = 0.99 and was measured to be 0.401 cc/g for TBPAL1, 0.369 cc/g for TBPAL2, 0.446 cc/g for TBPAL3, 0.529 cc/g for TBPAL4, and 0.760 cc/g for TBPAL5 (Table 1). The data obtained also suggest that PSD is comparatively narrow for polymers (TBPAL1 and TBPAL2) that utilize both trifunctional monomers in comparison to polymers (TBPAL3–TBPAL5) having bifunctional comonomers. These results evidently hint that the PSD of TBPALs may be tuned easily by changing the number of reactive sites in the monomers. The microporosity present in TBPALs is ascribed to the incorporation of the rigid 3D triptycene units in the polymer network (Chen et al., 2016; Roy et al., 2017; Bera et al., 2018b, 2019; Tan et al., 2018).

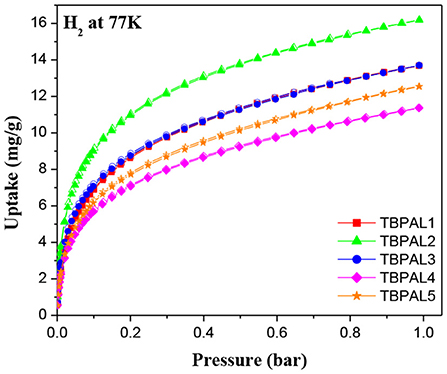

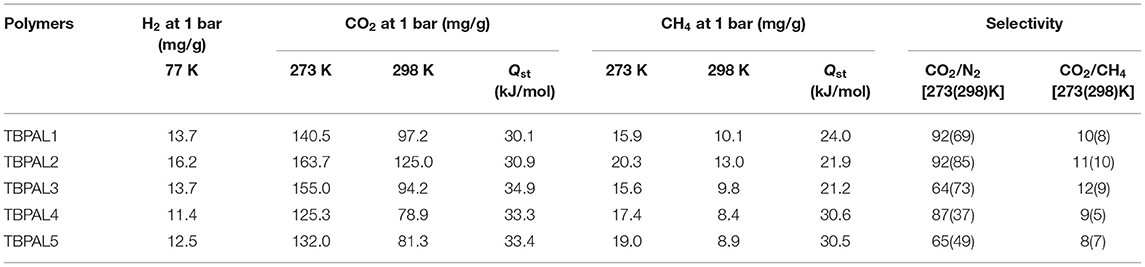

Considering the microporous nature of TBPALs, it was our curiosity to study their ability to act as adsorbent for small gaseous molecule. Therefore, sorption isotherms of CO2 (298 K), CH4 (298 K), H2 (77 K), and N2 (298 K) were obtained with the pressures up to 1 bar. Given that hydrogen is projected as a non-polluting alternative to fossil fuel, development of materials for H2 gas storage is an important research area. The H2 uptake by TBPALs was found to be in the range of 11.4–16.2 mg/g (Table 2 and Figure 6). The highest value was obtained for TBPAL2 (16.2 mg/g), and this is better than various MOPs and MOFs such as azo-bridged porphyrin-based conjugated microporous polymers (8.6–11.5 mg/g) (Xu et al., 2016b), triptycene-based hexakis (metalsalphens) (6–7 mg/g) (Reinhard et al., 2018), 3D ultramicroporous triptycene-based polyimide framework (14.1 mg/g) (Ghanem et al., 2016), rigid triptycene-hexaacid H6THA (7.8–11.8 mg/g) (Chandrasekhar et al., 2017a), porous hydrogen-bonded MOFs (1.1–1.3 mg/g) (Chandrasekhar et al., 2017b), carbazole-based POPs (11.9–12.9 mg/g) (Zhu et al., 2014), and phthalocyanine-based porous polymer (9 mg/g). (Neti et al., 2015) From the above comparison, it is clear that TBPALs reported herein show H2 uptake abilities that are better than several microporous polymeric networks reported previously in the literature. The results also reiterate the results of theoretical studies that concluded that networks with triptycene motifs may be well suited for H2 storage as efficient adsorbents. (Wong et al., 2009) Highest H2 uptake at low pressure (1 bar) recorded for TBPAL2 relative to other polymers is due to the presence of narrow ultramicropores in TBPAL2, even though its corresponding BET surface area is lesser than some other TBPALs. This is related to the kinetic diameter of H2 (0.29 nm) (Liu et al., 2015).

Table 2. H2, CO2, and CH4 uptakes, isosteric heats of adsorption (Qst) for TBPAL1–5 and CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4 selectivity.

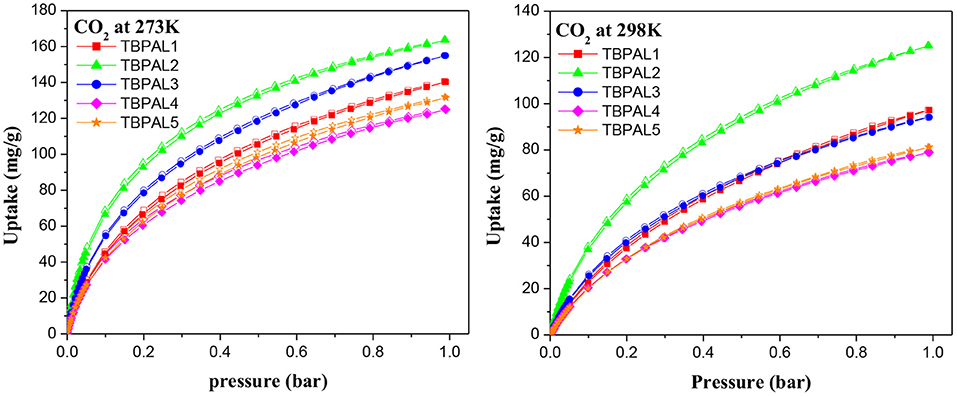

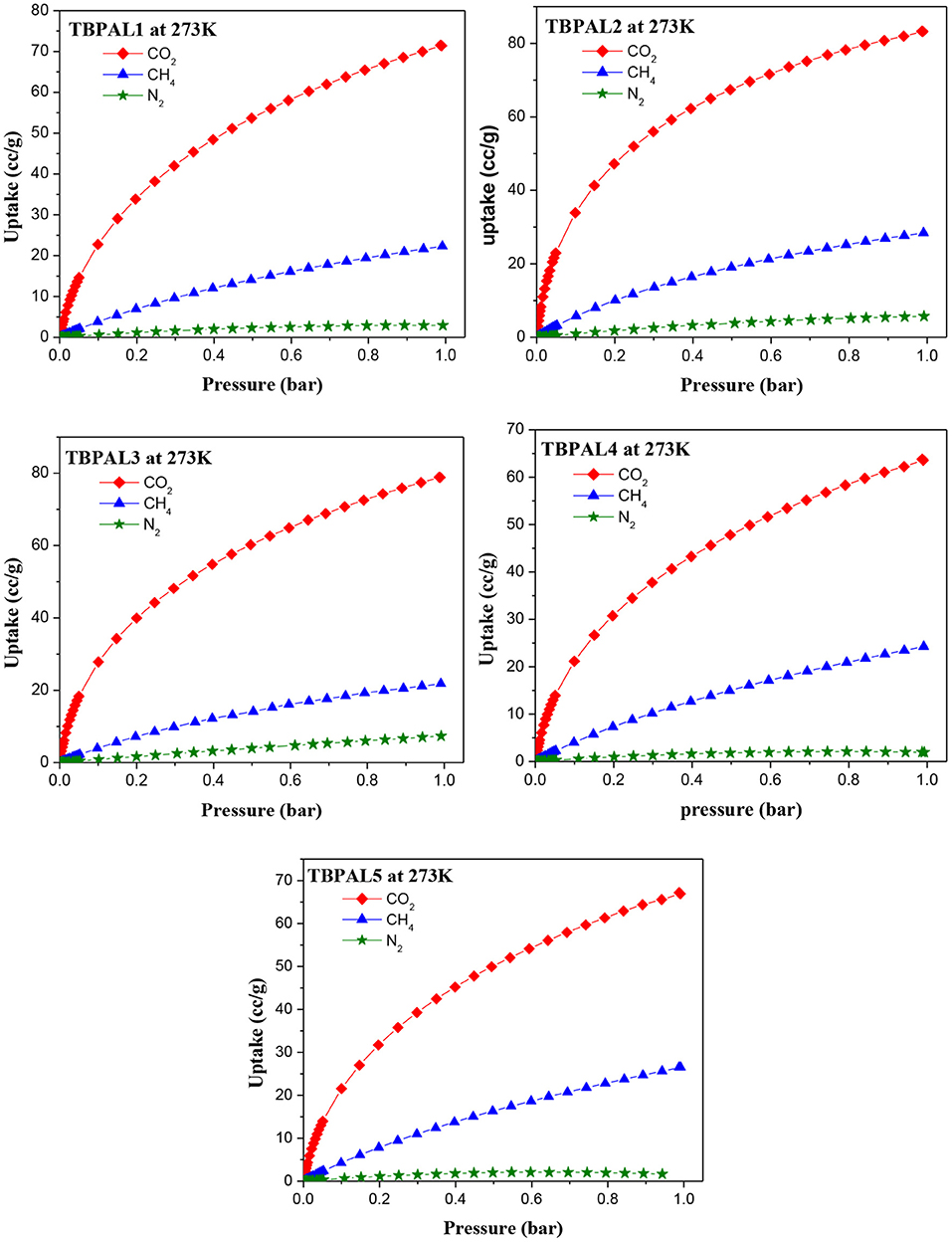

Capture of carbon dioxide gas at the polluting source is considered as a possible futuristic technological solution to contain the CO2 level in the atmosphere with the objective to curtail climatic changes such as global warming due to increasing concentration of greenhouse gases. Therefore, the CO2 adsorption properties of TBPALs were explored. Characteristic features of CO2 isotherm of TBPALs are their fully reversible nature (absence of sorption hysteresis) as well as steep rise in the low-pressure region (Figure 7). Reversible isotherm hints at easy regeneration of adsorbent without much energy expenditure. CO2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of TBPALs showed negligible hysteresis indicating the complete reversibility of CO2 adsorption, suggesting physisorption process rather than chemisorption of CO2 (Puthiaraj et al., 2017). TBPAL2 registers the highest CO2 uptake of 163.7 and 125.0 mg g−1 at 273 and 298 K, respectively, at 1 bar pressure. Presence of considerable narrow ultra micropores in TBPAL2 is also responsible for its efficient CO2 uptake ability in the low-pressure region, and this feature is related to the kinetic diameter of CO2 (0.33 nm) (Liu et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the extent of CO2 uptake by these TBPALs (125–164 mg g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar) is similar or superior to several previously reported POPs in general and N-rich porous polymers in particular. Representative examples of such POPs are amine-based cross-linked porous polymer (66.8 mg/g) (Mahmoud Abdelnaby et al., 2018), 3D ultramicroporous triptycene-based polyimide framework (149.6 mg/g) (Ghanem et al., 2016), triptycene-based hyper-cross-linked polymer sponge (157 mg/g) (Zhang et al., 2015), azo-functionalized MOPs (77.7–134.8 mg/g) (Yang et al., 2015), phthalocyanine nanoporous polymer (157 mg/g) (Neti et al., 2015), porous covalent triazine polymer (CTP) (6.6–29.5 mg/g) (Lee et al., 2018), and triptycene-based hexakis (metalsalphens) (50–58 mg/g) (Reinhard et al., 2018). The observed high CO2 uptake capacity of TBPALs is due to the high affinity between amine functional groups in the polymeric framework and carbon dioxide molecules via strong dipole–dipole interactions and Lewis acid–base interactions.

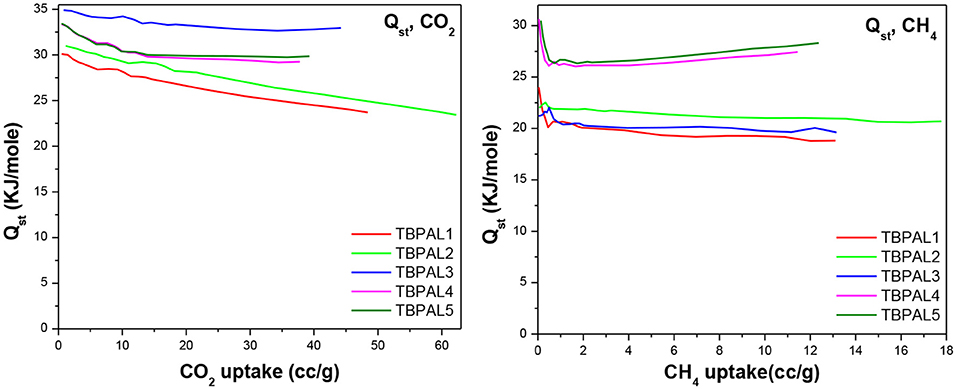

We also estimated isosteric heats of CO2 adsorption (Qst) for TBPALs at 273 and 298 K using the Clausius–Clapeyron equation. The Qst values for CO2 at zero coverage were observed to be in between 30.1 and 34.9 kJ mol−1 (Table 2 and Figure 8). Since the magnitude of Qst is <40 kJ mol−1, it may concluded that there is reasonable CO2 physisorption by TBPALs (Patel et al., 2013). The reasonably high Qst value seen at the onset of adsorption may be assigned to strong interactions between carbon dioxide molecules (Lewis acidic) and polar amine functional groups (Lewis basic). The Qst values obtained for TBPALs are comparable with various literature reported porous materials such as porous cyanate resin networks (31.0–34.6 kJ mol−1) (Deng and Wang, 2017), porous covalent triazine polymer (CTP) (22.4-34.6 kJ mol−1) (Lee et al., 2018), and triptycene-based hexakis (metalsalphens) (24.4–29.1 kJ mol−1) (Reinhard et al., 2018).

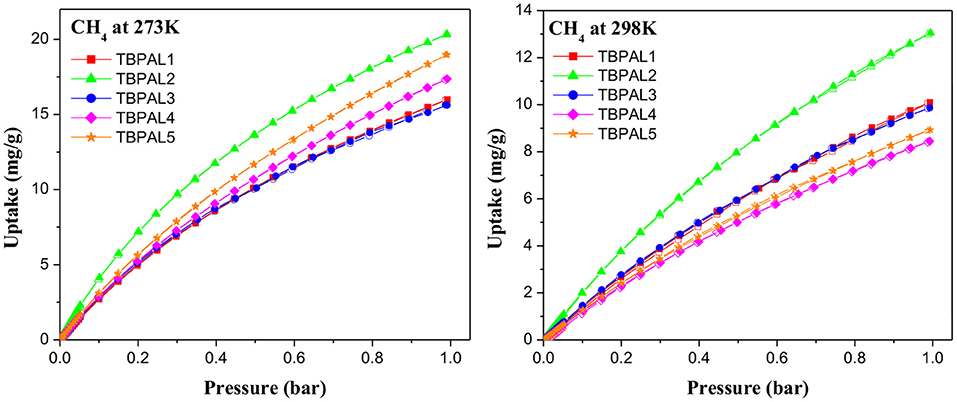

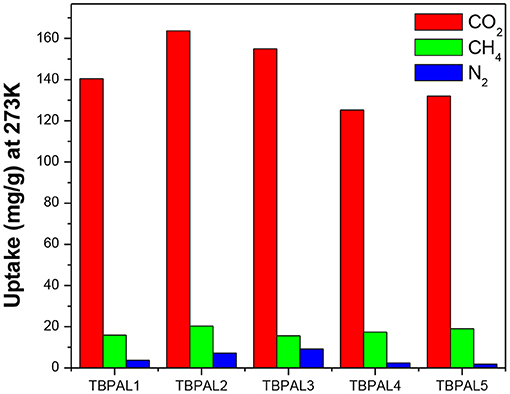

In addition to CO2 and H2, TBPALs were also considered as potential sorbent for methane gas. CH4 gas isotherms of TBPALs were collected at 273 K and 298 K up to 1 bar pressure (Figure 9). In both cases, the isotherms are reversible. At 273 K, TBPAL2 records highest methane uptake (20.3 mg g−1) while TBPAL3 registers the lowest (15.6 mg g−1). We have also investigated the Qst for methane adsorption in TBPALs and values at very low coverage are in the range of 21.2–30.6 kJ mol−1 (Table 2 and Figure 8). These values suggest physisorption of methane and as good as that observed for various organic porous polymers and MOFs such as phthalocyanine nanoporous polymer (17.8 mg g−1) (Neti et al., 2015), B,N-containing cross-linked polymers (PPs-BN, 15.7–18.44 mg/g) (Zhao et al., 2015), triptycene-based hexakis (metalsalphens) (7–8 mg g−1) (Reinhard et al., 2018), azo-PPors (11.54–12.83 mg g−1) (Jiang et al., 2015), and nanoporous triptycene-based network polyamides (4.0–8.3 mg g−1) (Bera et al., 2017). Figure 10 shows comparative uptake of carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and methane by TBPALs at 273 K.

Gas Selectivity

Data from CO2 isotherms suggest that TBPALs have a reasonably high carbon dioxide adsorption ability. Additionally, for TBPALs to be potential adsorbents of post-combustion CO2 present in flue gas, these should show high CO2/N2 selectivity. The CO2/N2 selectivity of each TBPAL was measured at two temperatures (273 and 298 K) by using the single component gas adsorption isotherms (Figure 11 and Figure S5). Ratios of initial slopes of CO2 and N2 isotherms provided the magnitude of CO2/N2 selectivity at a given temperature (Figures S6, S7). The initial region of the respective CO2 isotherm is much steeper than the corresponding isotherm of N2 for each TBPAL. In flue gas, the partial pressure of CO2 is 0.15 bar at 273 K. Therefore, it is relevant to compare relative uptake of CO2 and N2 (the two major components in flue gas) at 0.15 bar pressure. The CO2/N2 selectivity results of TBPALs are depicted in Table 2. Among the five polymers reported herein, TBPAL1 and TBPAL2 exhibit the highest selectivity (92) for CO2 over N2 at 273 K. On the other hand, such CO2/N2 selectivity is lowest for TBPAL3 (64) under similar experimental conditions. Nevertheless, TBPALs (TBPAL1–5) show a reasonably high CO2/N2 selectivity (64–92), and this parameter is better than various literature reported porous materials—representative examples are covalent triazine-based frameworks (CTFs) (20–25) (Dey et al., 2016), porous cyanate resin networks (39–60) (Deng and Wang, 2017), triptycene-derived benzimidazole-linked polymers (59–63) (Rabbani et al., 2012), triptycene-based hyper-cross-linked polymer sponge, THPS (38) (Zhang et al., 2015), benzothiazole- and benzoazole-linked polymers (41–55) (Rabbani et al., 2017), triptycene-based 1,2,3-triazole linked network (31–48) (Mondal and Das, 2015), HCPs reported such as C1M2-Al (32.3) (Liu et al., 2015), and microporous polymer such as azo-linked polymers (ALPs, 44-60) (Arab et al., 2015). The CO2/N2 selectivity is even more significant at 298 K because this mimics more closely the condition required for the post-combustion CO2 uptake from flue gas. Among the five TBPALs reported herein, except for TBPAL3, the others show a decrease in CO2/N2 selectivity at higher temperature. This trend (decreased selectivity at higher temperature) is commonly observed for most POPs reported to date (Arab et al., 2014). For TBPAL2, the selectivity decreases only to a small extent at elevated temperature from 92 (at 273 K) to 85 (at 298 K). However, in case of TBPAL3, its selectivity for CO2 over N2 was found to be larger at higher temperature−64 (at 273 K) vs. 73 (at 298 K). Such a gain in CO2/N2 selectivity on going to 298 from 273 K is rare but not unprecedented and has been reported by Patel et al. (2013) and Zhu et al. (2013). Next, the CO2/CH4 selectivity of TBPALs was estimated, employing the initial slope ratios from Henry's law constant for single carbon dioxide or methane adsorption isotherms at 273 and 298 K (Figure 11 and Figure S5). Adsorbents that selectively capture CO2 over methane are important from the aspect of purification of natural gas that contains CO2 as an undesirable contaminant up to 8%. The contamination of methane with carbon dioxide in the natural gas results in lowering of calorific value (of natural gas). Further, presence of acidic CO2 in natural gas may be responsible for pipeline and equipment corrosion. The extent of CO2/CH4 selectivity shown by TBPALs was in the range of 8–12 at 273 K (1 bar pressure). At 298 K, the CO2/CH4 selectivity did not decrease substantially as tabulated in Table 2. Thus, one may infer that TBPALs maintain the CO2/CH4 selectivity even at higher temperatures. However, in comparison to CO2/N2 selectivity, the degree of CO2/CH4 selectivity of TBPALs is significantly lower and this can be ascribed to the higher polarizibility of CH4 in comparison to N2 (Arab et al., 2014).

Conclusions

In summary, we report herein for the first time a set of five triptycene-based porous polymers (TBPALs) with hierarchical porosity in which the triptycene units are interconnected via –NH– functional groups. Such unique triptycene networks cross-linked by amine functional groups were conveniently synthesized in high yields from commercially available phloroglucinol as one of the monomers. Formation of C–N bonds did not require the use of transition metal-based catalysts, such as the ones used in Buchwald-Hartwig cross-coupling reaction or the Ullmann method. Important properties of such TBPALs are good thermal stability with improved surface area (SABET up to 815 m2 g−1) relatively to previously reported porous aromatic networks linked via amine units. For the first time, CO2/N2 selectivity has been measured for such amine-linked POPs, and these values are in the range of 64–92 (at 273 K). Again, for the first time, these amine-functionalized and triptycene-based POPs were explored as materials for H2 storage. Highest H2 uptake (16.2 mg g−1) was registered by TBPAL2 and that is comparable with several hyper cross-linked polymers (HCPs) reported previously. These results suggest that amine-based polymers with robust and rigid units (such as triptycene) are a new addition to the family of nanoporous materials that display considerably high CO2 uptake with reasonably good CO2/N2 selectivities for CO2 capture applications. These results motivate us and others to develop new polyamine porous polymers with promising applications as smart materials in environment/alternative energy sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Author Contributions

ND conceived the research and supervised the experimental work related to synthesis and characterization reported herein. AA synthesized all polymeric networks reported in this manuscript. MA and AH assisted AA in the synthesis of literature reported triptycene monomers. AA characterized the polymers and was assisted by RB. All authors have contributed to interpretation of results, compiled the manuscript, and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

ND thanks the Indian Institute of Technology Patna for instrumental facilities. AA, RB, MA, and AH thankfully acknowledge IIT Patna for their respective Institute Research Fellowships.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenrg.2019.00141/full#supplementary-material

References

Arab, P., Parrish, E., Islamoglu, T., and El-Kaderi, H. M. (2015). Synthesis and evaluation of porous azo-linked polymers for carbon dioxide capture and separation. J. Mater. Chem. 3, 20586–20594. doi: 10.1039/C5TA04308E

Arab, P., Rabbani, M. G., Sekizkardes, A. K., Islamoglu, T., and El-Kaderi, H. M. (2014). Copper(I)-catalyzed synthesis of nanoporous azo-linked polymers: impact of textural properties on gas storage and selective carbon dioxide capture. Chem. Mater. 26, 1385–1392. doi: 10.1021/cm403161e

Bandyopadhyay, S., Singh, C., Jash, P., Hussain, M. D., Paul, W., Redox-active, A., et al. (2018). pyrene-based pristine porous organic polymers for efficient energy storage with exceptional cyclic stability. ChemComm 54, 6796–6799. doi: 10.1039/C8CC02477D

Bera, R., Ansari, M., Alam, A., and Das, N. (2018b). Nanoporous azo polymers (NAPs) for selective CO2 uptake. J. CO2 Util. 28, 385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jcou.2018.10.016

Bera, R., Ansari, M., Alam, A., and Das, N. (2019). Triptycene, phenolic-OH, and Azo-functionalized porous organic polymers: efficient and selective CO2 capture. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 1, 959–968. doi: 10.1021/acsapm.8b00264

Bera, R., Ansari, M., Mondal, S., and Das, N. (2018a). Selective CO2 capture and versatile dye adsorption using a microporous polymer with triptycene and 1,2,3-triazole motifs. Eur. Polym. J. 99, 259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2017.12.029

Bera, R., Mondal, S., and Das, N. (2017). Nanoporous triptycene based network polyamides (TBPs) for selective CO2 uptake. Polymer 111, 275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2017.01.056

Bhanja, P., Mishra, S., Manna, K., Mallick, A., Das Saha, K., and Bhaumik, A. (2017). Covalent organic framework material bearing phloroglucinol building units as a potent anticancer agent. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 31411–31423. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b07343

Chandrasekhar, P., Mukhopadhyay, A., Savitha, G., and Moorthy, J. N. (2017b). Orthogonal self-assembly of a trigonal triptycene triacid: signaling of exfoliation of porous 2D metal–organic layers by fluorescence and selective CO2 capture by the hydrogen-bonded MOF. J. Mater. Chem. 5, 5402–5412. doi: 10.1039/C6TA11110F

Chandrasekhar, P., Savitha, G., and Moorthy, J. N. (2017a). Robust MOFs of “tsg” topology based on trigonal prismatic organic and metal cluster SBUs: single crystal to single crystal postsynthetic metal exchange and selective CO2 capture. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 7297–7305. doi: 10.1002/chem.201700139

Chen, D., Gu, S., Fu, Y., Zhu, Y., Liu, C., Li, G., et al. (2016). Tunable porosity of nanoporous organic polymers with hierarchical pores for enhanced CO2 capture. Polym. Chem. 7, 3416–3422. doi: 10.1039/C6PY00278A

Chen, J.-J., Zhai, T.-L., Chen, Y.-F., Geng, S., Yu, C., Liu, J.-M., et al. (2017). triptycene-based two-dimensional porous organic polymeric nanosheet. Polym. Chem. 8, 5533–5538. doi: 10.1039/C7PY01122A

Chen, Z., and Swager, T. M. (2008). Synthesis and characterization of Poly(2,6-triptycene). Macromolecules 41, 6880–6885. doi: 10.1021/ma8012527

Cong, H., Zhang, M., Chen, Y., Chen, K., Hao, Y., Zhao, Y., et al. (2015). Highly selective CO2 capture by nitrogen enriched porous carbons. Carbon N. Y. 92, 297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2015.04.052

Das, S., Heasman, P., Ben, T., and Qiu, S. (2017). Porous organic materials: strategic design and structure–function correlation. Chem. Rev. 117, 1515–1563. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00439

Deng, G., and Wang, Z. (2017). Triptycene-based microporous cyanate resins for adsorption/separations of benzene/cyclohexane and carbon dioxide gas. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 41618–41627. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b15050

Dey, S., Bhunia, A., Breitzke, H., Groszewicz, P. B., Buntkowsky, G., and Janiak, C. (2017). Two linkers are better than one: enhancing CO2 capture and separation with porous covalent triazine-based frameworks from mixed nitrile linkers. J. Mater. Chem. 5, 3609–3620. doi: 10.1039/C6TA07076K

Dey, S., Bhunia, A., Esquivel, D., and Janiak, C. (2016). Covalent triazine-based frameworks (CTFs) from triptycene and fluorene motifs for CO2 adsorption. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 6259–6263. doi: 10.1039/C6TA00638H

Ghanem, B., Belmabkhout, Y., Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Han, Y., Eddaoudi, M., et al. (2016). A unique 3D ultramicroporous triptycene-based polyimide framework for efficient gas sorption applications. RSC Adv. 6, 97560–97565. doi: 10.1039/C6RA21388J

Gu, S., Guo, J., Huang, Q., He, J., Fu, Y., Kuang, G., et al. (2017). 1,3,5-triazine-based microporous polymers with tunable porosities for CO2 capture and fluorescent sensing. Macromolecules 50, 8512–8520. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b01857

Huang, K., Zhang, J.-Y., Liu, F., and Dai, S. (2018). Synthesis of porous polymeric catalysts for the conversion of carbon dioxide. ACS Catal. 8, 9079–9102. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b02151

Jiang, X., Liu, Y., Liu, J., Luo, Y., and Lyu, Y. (2015). Facile synthesis of porous organic polymers bifunctionalized with azo and porphyrin groups. RSC Adv. 5, 98508–98513. doi: 10.1039/C5RA19422A

Lee, S. P., Mellon, N., Shariff, A. M., and Leveque, J. M. (2018). Geometry variation in porous covalent triazine polymer (CTP) for CO2 adsorption. New J. Chem. 42, 15488–15496. doi: 10.1039/C8NJ00638E

Li, Q., Mu, X., Xiao, S., Wang, C., Chen, Y., and Yuan, X. (2019). Porous aromatic networks with amine linkers for adsorption of hydroxylated aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 136:46919. doi: 10.1002/app.46919

Li, Y., Zheng, S., Liu, X., Li, P., Sun, L., Yang, R., et al. (2018). Conductive microporous covalent triazine-based framework for high-performance electrochemical capacitive energy storage. Angew. Chem. 57, 7992–7996. doi: 10.1002/anie.201711169

Liao, Y., Wang, H., Zhu, M., and Thomas, A. (2018). Efficient supercapacitor energy storage using conjugated microporous polymer networks synthesized from buchwald–hartwig coupling. Adv. Mater. Weinheim. 30:1705710. doi: 10.1002/adma.201705710

Liu, G., Wang, Y., Shen, C., Ju, Z., and Yuan, D. (2015). A facile synthesis of microporous organic polymers for efficient gas storage and separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 3051–3058. doi: 10.1039/C4TA05349D

Liu, H., and Liu, H. (2017). Selective dye adsorption and metal ion detection using multifunctional silsesquioxane-based tetraphenylethene-linked nanoporous polymers. J. Mater. Chem. 5, 9156–9162. doi: 10.1039/C7TA01255A

Mahmoud Abdelnaby, M., Alloush, A. M., Qasem, N. A., Al-Maythalony, A., Mansour, A., and Al Hamouz, O. C. S. (2018). Carbon dioxide capture in the presence of water by an amine-based crosslinked porous polymer. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 6455–6462. doi: 10.1039/C8TA00012C

Mane, S., Gao, Z.-Y., Li, Y. X., Liu, X. Q., and Sun, L. B. (2018). Rational fabrication of polyethylenimine-linked microbeads for selective CO2 capture. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 250–258. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b04212

Mane, S., Gao, Z. Y., Li, Y. X., Xue, D. M., Liu, X. Q., and Sun, L. B. (2017). Fabrication of microporous polymers for selective CO2 capture: the significant role of crosslinking and crosslinker length. J. Mater. Chem. 5, 23310–23318. doi: 10.1039/C7TA07188D

Mitra, S., Sasmal, H. S., Kundu, T., Kandambeth, S., Illath, K., and Banerjee, R. (2017). Targeted drug delivery in covalent organic nanosheets (CONs) via sequential postsynthetic modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 4513–4520. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00925

Mondal, S., and Das, N. (2015). Triptycene based 1,2,3-triazole linked network polymers (TNPs): small gas storage and selective CO2 capture. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 23577–23586. doi: 10.1039/C5TA06939D

Neti, V. S. P., Wang, K., Deng, J., and Echegoyen, S. L. (2015). High and selective CO2 adsorption by a phthalocyanine nanoporous polymer. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 10284–10288. doi: 10.1039/C5TA00587F

Ou, H., Zhang, W., Yang, X., Cheng, Q., Liao, G., Xia, H., et al. (2018). One-pot synthesis of g-C3N4-doped amine-rich porous organic polymer for chlorophenol removal. Environ. Sci. Nano 5, 169–182. doi: 10.1039/C7EN00787F

Patel, H. A., Hyun Je, S., Park, J., Chen, D. P., Jung, Y., and Coskun, A. (2013). Unprecedented high-temperature CO2 selectivity in N2-phobic nanoporous covalent organic polymers. Nat. Commun. 4:1357. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2359

Puthiaraj, P., Lee, Y. R., and Ahn, W. S. (2017). Microporous amine-functionalized aromatic polymers and their carbonized products for CO2 adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 319, 65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.03.001

Rabbani, M. G., Islamoglu, T., and El-Kaderi, H. M. (2017). Benzothiazole- and benzoxazole-linked porous polymers for carbon dioxide storage and separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 258–265. doi: 10.1039/C6TA06342J

Rabbani, M. G., Reich, T. E., Kassab, R. M., Jackson, K. T., and El-Kaderi, H. M. (2012). High CO2 uptake and selectivity by triptycene-derived benzimidazole-linked polymers. ChemComm 48, 1141–1143. doi: 10.1039/C2CC16986J

Reinhard, D., Zhang, W.-S., Rominger, F., Curticean, R., Wacker, I., Schröder, R., et al. (2018). Discrete triptycene-based hexakis(metalsalphens): extrinsic soluble porous molecules of isostructural constitution. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 11433–11437. doi: 10.1002/chem.201802041

Roy, S., Kim, J., Kotal, M., Kim, K. J., and Oh, I. K. (2017). Electroionic antagonistic muscles based on nitrogen-doped carbons derived from Poly(Triazine-Triptycene). Adv. Sci. 4:1700410. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700410

Shuangzhi, C., Liu, H., Zhang, X., Han, Y., Hu, N., Wei, L., et al. (2016). Synthesis of a novel β-ketoenamine-linked conjugated microporous polymer with NH functionalized pore surface for carbon dioxide capture. Appl. Surf. Sci. 384, 539–543. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.05.068

Sing, K. S. W. (1982). Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity. Pure Appl. Chem. 54, 2201–2218. doi: 10.1351/pac198254112201

Sing, K. S. W. (1985). Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems. Pure Appl. Chem. 57, 603–619. doi: 10.1351/pac198557040603

Swager, T. M. (2008). Iptycenes in the design of high performance polymers. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1181–1189. doi: 10.1021/ar800107v

Tan, H., Chen, Q., Chen, T., and Liu, H. (2018). Selective adsorption and separation of Xylene isomers and benzene/cyclohexane with microporous organic polymers POP-1. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 32717–32725. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b11657

Taskin, O. S., Kiskan, B., Aksu, A., Balkis, N., and Yagci, Y. (2016). Copper(II) removal from the aqueous solution using microporous benzidine-based adsorbent material. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 4, 899–907. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2015.12.041

Trickett, C. A., Helal, A., Al-Maythalony, B. A., Yamani, Z. H., Cordova, K. E., and Yaghi, O. M. (2017). The chemistry of metal–organic frameworks for CO2 capture, regeneration and conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2:17045. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.45

Wong, M., Van Kuiken, B. E., Buda, C., and Dunietz, B. D. (2009). Multiadsorption and coadsorption of hydrogen on model conjugated systems. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 12571–12579. doi: 10.1021/jp8106588

Wu, J., Xu, F., Li, S., Ma, P., Zhang, X., Liu, Q., et al. (2019). Porous polymers as multifunctional material platforms toward task-specific applications. Adv. Mater. Weinheim. 31:1802922. doi: 10.1002/adma.201802922

Xu, Y., Chang, D., Feng, S., Zhang, C., and Jiang, J. X. (2016a). BODIPY-containing porous organic polymers for gas adsorption. N. J. Chem. 40, 9415–9423. doi: 10.1039/C6NJ01812B

Xu, Y., Li, Z., Zhang, F., Zhuang, X., Zeng, Z., and Wei, J. (2016b). New nitrogen-rich azo-bridged porphyrin-conjugated microporous networks for high performance of gas capture and storage. RSC Adv. 6, 30048–30055. doi: 10.1039/C6RA04077B

Yang, Z., Zhang, H., Yu, B., Zhao, Y., Ma, Z., Ji, G., et al. (2015). Azo-functionalized microporous organic polymers: synthesis and applications in CO2 capture and conversion. ChemComm 51, 11576–11579. doi: 10.1039/C5CC03151F

Yu, X., Yang, Z., Guo, S., Liu, Z., Zhang, H., Yu, B., et al. (2018). Mesoporous imine-based organic polymer: catalyst-free synthesis in water and application in CO2 conversion. ChemComm 54, 7633–7636. doi: 10.1039/C8CC03346C

Zhang, C., and Chen, C. F. (2006). Synthesis and structure of 2,6,14- and 2,7,14-trisubstituted triptycene derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 71, 6626–6629. doi: 10.1021/jo061067t

Zhang, C., Zhai, T. L., Wang, J. J., Wang, Z. J., Liu, M., Xu, B., et al. (2014). Triptycene-based microporous polyimides: synthesis and their high selectivity for CO2 capture. Polymer 55, 3642–3647. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2014.06.074

Zhang, C., Zhu, P. C., Tan, L., Liu, J. M., Tan, B., and Xu, B. (2015). Triptycene-based hyper-cross-linked polymer sponge for gas storage and water treatment. Macromolecules 48, 8509–8514. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b02222

Zhang, S., Yang, Q., Wang, C., Luo, X., Kim, J., Wang, Z., et al. (2018). Porous organic frameworks: advanced materials in analytical chemistry. Adv. Sci. 5:1801116. doi: 10.1002/advs.201801116

Zhang, Y., Zhu, Y., Guo, J., Gu, S., Wang, Y., Fu, Y., et al. (2016). The role of the internal molecular free volume in defining organic porous copolymer properties: tunable porosity and highly selective CO2 adsorption. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 11323–11329. doi: 10.1039/C6CP00981F

Zhao, W., Han, S., Zhuang, X., Zhang, F., Mai, Y., and Feng, X. (2015). Cross-linked polymer-derived B/N co-doped carbon materials with selective capture of CO2. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 23352–23359. doi: 10.1039/C5TA06702B

Zhu, J.-H., Chen, Q., Sui, Z.-Y., Pan, L., Yu, J., and Han, B. H. (2014). Preparation and adsorption performance of cross-linked porous polycarbazoles. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 16181–16189. doi: 10.1039/C4TA01537A

Keywords: triptycene copolymer, CO2/N2 selectivity, nanoporous, H2 adsorption activity, carbon dioxide adsorption

Citation: Alam A, Bera R, Ansari M, Hassan A and Das N (2019) Triptycene-Based and Amine-Linked Nanoporous Networks for Efficient CO2 Capture and Separation. Front. Energy Res. 7:141. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2019.00141

Received: 16 August 2019; Accepted: 15 November 2019;

Published: 20 December 2019.

Edited by:

Fateme Rezaei, Missouri University of Science and Technology, United StatesReviewed by:

Youn-Sang Bae, Yonsei University, South KoreaEduardo René Perez Gonzalez, São Paulo State University, Brazil

Copyright © 2019 Alam, Bera, Ansari, Hassan and Das. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Neeladri Das, bmVlbGFkcmlAaWl0cC5hYy5pbg==; bmVlbGFkcmkyMDAyQHlhaG9vLmNvLmlu

Akhtar Alam

Akhtar Alam Ranajit Bera

Ranajit Bera Atikur Hassan

Atikur Hassan Neeladri Das

Neeladri Das