95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Energy Res. , 18 April 2019

Sec. Electrochemical Energy Storage

Volume 7 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2019.00038

This article is part of the Research Topic Surface Chemistry and Materials Design in Lithium-Sulfur Batteries View all 4 articles

High-energy-density batteries are actively sought after for next-generation electric vehicle (EV) applications, triggering the search for sulfur-based positive electrode materials with high capacity for extended driving range. One of the primary issues of sulfur cathodes is the rapid capacity decay caused by the dissolution of sulfur in the electrolyte and the resulting parasitic reactions. This can be prevented by incorporating a suitable amount of carbon material into the sulfur electrodes, because of its inherent properties; however, introducing a large amount of low-density carbon materials will lead to a decrease in the energy density of the battery. Therefore, an alternative method to suppress sulfur dissolution is required for commercial applications. Recently, we developed a Fe-containing Li2S-based material (Li8FeS5) as the sulfur cathode; it has a relatively high initial discharge capacity (>700 mAh·g−1) and electric conductivity. However, rapid capacity degradation was observed during the initial several cycles, due to some unknown reactions between the electrolyte and Li8FeS5. In this study we demonstrate an effective method to improve the cycle performance of Li8FeS5 by coating its surface with a stabilizing material. We selected titanium oxide as the coating material, based on its high stability toward liquid electrolytes and its strong interaction with sulfur. Hence, we obtained TiOx-coated Li8FeS5 particles (Li8FeS5-TiOx) by a liquid-phase reaction. The transmission electron microscopy observation revealed that the Li8FeS5 particles were coated with several tens of nanometers of TiOx layers. The Li8FeS5-TiOx cells exhibited improved cycling performance with a carbonate electrolyte. We also observed that the capacity originating from an iron redox was not affected by coating during the cycling test; in contrast, the degradation of the cell capacity corresponding to the sulfur redox was suppressed significantly after coating with the TiOx layer. Thus, the surface reaction of Li8FeS5 with the electrolyte, which could be the main reason for the cycling degradation, was effectively suppressed by coating with the TiOx layer.

High-energy-density batteries are required for next-generation electric vehicle (EV) applications. As a candidate for a positive electrode material, sulfur, in particular, is promising, owing to its high theoretical capacity of 1,670 mAh g−1. This has triggered the search for sulfur-based positive electrode materials with high capacity. One of the main limitations to utilizing a sulfur cathode is its electronically insulating nature, which requires compounding with a sufficient amount of electrically-conductive materials in the positive electrode (Obrovac and Dahn, 2002). Another issue is the poor electrochemical performance caused by polysulfide dissolution, which leads to the irreversible loss of active materials from the cathode, low coulombic efficiency, and rapid capacity fading. To offset these shortcomings, various methods have been explored, and most efforts have been devoted to developing conducting carbon with a porous matrix host structure (Schuster et al., 2012). The conducting porous hosts provide electronic conduction paths and effectively prevent rapid capacity decay by capturing kinetically formed polysulfides within the host pores. However, the introduction of porous carbon reduces the loading of active materials in the positive electrode because of the low specific gravity of carbon materials. Despite the potential of sulfur-based cathode materials, their practical use in EVs is still limited by the nature of sulfur chemistry.

Recently, Takeuchi et al. developed a low-crystalline metal polysulfide a Li2S-based material containing iron (Li8FeS5), via heat treatment and mechanical milling (Takeuchi et al., 2012, 2015, 2018). They found that Li8FeS5 had almost the same electron conductivity as a semiconductor and a high initial discharge capacity (>700 mAh g−1) at the first charge-discharge. Surprisingly, Li8FeS5 worked consistently as a positive active material even after several tens of cycles in a carbonate-based electrolyte, whereas conventional sulfur-based materials, like Li2S, were not a suitable active material in carbonate-based electrolytes. This is because typical sulfur-based materials are not stable and exhibit extremely low discharge capacity at the first cycle in a carbonate-based electrolyte (Gao et al., 2011). The low discharge capacity and poor cycle property appear to originate from the accumulation of sulfur-containing degradation products, which are formed by polysulfide attack as a nucleophilic agent against the carbonate-based electrolyte during the discharge. The sulfur in the degradation products is considered fully electrochemically inactive. This high reactivity of polysulfides against the electrolyte is considered the main reason for the poor cycling property. Thus, Fe-compounding can stabilize the Li2S framework for Li extraction/insertion reactions.

To understand the stabilization mechanism of Li8FeS5, the low-crystallinity Li8FeS5 structure was analyzed by X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) analysis after the cycle test (Takeuchi et al., 2012). Result showed that a Fe-S chemical bond is formed in Li8FeS5 after the first charge-discharge cycle, which is retained even after several tens of cycles. The reversibility of the XAFS spectrum indicated that the bulk structure of Li8FeS5 is more stable than that of Li2S during cycling. It was deduced that the Fe-S bonding prevents polysulfide dissolution and the reaction with the carbonate-based electrolyte. Even though Li8FeS5 intrinsically showed rather reversible structural changes for Li extraction/insertion reactions, a rapid capacity degradation was observed during the initial several cycles of the Li8FeS5 cathode. Considering these XAFS results, it is likely that the relatively unstable surface of Li8FeS5 particles might react with the electrolyte, thereby leading to the initial decay.

During the past few years, some potentially effective coatings for sulfur-active materials have been proposed, such as metal sulfides (Seh et al., 2014), various structures of carbon (Wang et al., 2010; Jayaprakash et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2017), organic materials such as polymers (Yang et al., 2011; Lia et al., 2013), and metal oxides (Wei Seh et al., 2013). Considering the need for chemical stability toward the electrolyte, coating the metal sulfide with a metal oxide material appears to be one of the most promising solutions.

Recent reports showed that titanium oxide (TiO2) can absorb a polysulfide on its surface and improve the cycle property of lithium-sulfur battery. Ding et al. encapsulated sulfur in a nanoporous TiO2 to trap polysulfide (Ding et al., 2013). Xiao et al. applied a graphene-TiO2 layer as a polysulfide absorbent interlayer in a lithium-sulfur battery (Xiao et al., 2015). Yan et al. incorporated TiO2 nanowires in the electrode, which effectively suppressed the dissolution of polysulfide (Yan et al., 2018). Li et al. used microporous/mesoporous TiO2 derived from metal organic frameworks (MOFs) precursors as a porous matrix host structure (Li et al., 2016). It was believed that TiO2 adsorb polysulfide dissolution from electrode and avoid redox shuttle reaction.

In this study, we focused on improving the cycle performance of Li8FeS5 by coating its surface with titanium oxide (TiOx). We then compared the electrochemical performances of the pristine Li8FeS5 and TiOx-coated Li8FeS5 (Li8FeS5-TiOx) cells.

Li8FeS5 was prepared based on a previously reported method (Takeuchi et al., 2018). Because of the sensitivity of Li2S to moisture, all material synthesis procedures were carried out in an argon atmosphere. First, 0.5 g of Li8FeS5 and 0.157 g of commercially available titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4, special grade, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.) were mixed in 40 dm3 of heptane (super dehydrated, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.); the using a glass filter (Glass Microfiber filters, Grade GF/F) the solid was filtered after stirring for 1 h followed by washing with a copious amount of dimethyl carbonate (DMC, battery grade, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.) (Chianelli and Dines, 1978). This intermediate product was heated at 400°C for 10 h in an argon atmosphere, whereby the chlorides were removed, resulting in the formation of coated Li8FeS5 particles labeled as Li8FeS5-TiOx.

The elemental composition of Li8FeS5-TiOx was determined by inductively coupled plasma (ICP) atomic emission microscopy (IRIS Advantage, Nippon Jarrell-Ash Co. Ltd.).

The electrochemical impedance was potentiostatically measured with an oscillation of 10 mV amplitude over frequencies from 106 to 0.1 Hz using a Solartron analytical 1470E Cell test system, 1455A Multi-Channel analyzer, controlled by Zplot software.

Cross-section of the Li8FeS5-TiOx particles were prepared by milling the positive electrode with a focused ion beam (FIB, FB2200, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation.) for analysis by scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM, HD-2700, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation).

The electrochemical lithium insertion/extraction reaction was carried out using lithium coin-type cells. The working electrode consisted of a mixture of 5.5 mg Li8FeS5 or Li8FeS5-TiOx as an active material, 2.0 mg ketjen black (EC-300J, LION Corporation) as a conductive material, and 0.3 mg polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) as a binder. All materials were mixed in a mortar and pressed to achieve uniform thickness by using a roller. Then, a positive electrode was punched into a 10 mm-diameter disk. The thickness of the electrodes was controlled to contain 3 mg of active material. The negative electrode was a 15 mm-diameter and 200 nm-thick disk of lithium foil, and the separator was a microporous polyolefin sheet.

The electrochemical charge/discharge tests were performed with 1 mol dm−3 lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6, Kishida Chemical Co., Ltd.) in 10: 90 (v/v) ethylene carbonate (EC, Kishida Chemical Co., Ltd.) and propylene carbonate (PC, Kishida Chemical Co., Ltd.) electrolyte at a current density of 98.6 mA g−1 (corresponding to 0.1 C) and a voltage between 2.6 and 1.0 V vs. Li/Li+.

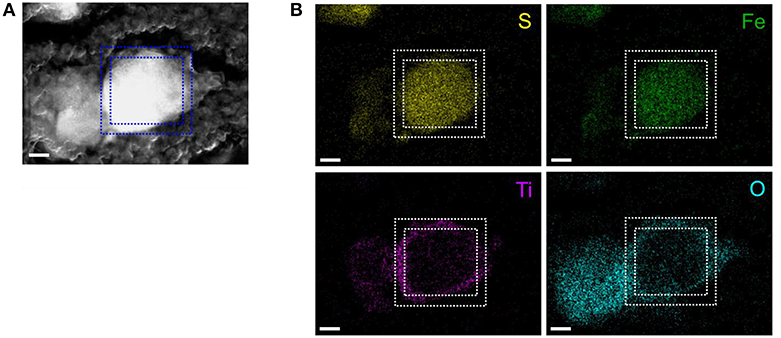

Figure 1 shows the TEM Energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS) images of the cross-sections of the positive electrode surface containing Li8FeS5-TiOx particles. The dotted square indicates a Li8FeS5-TiOx particle in Figure 1A. Figure 1B shows the EDS mapping results, in which sulfur and iron are detected in the core of the particle, whereas titanium and oxygen are detected mainly on the edge of the particle. Therefore, the Li8FeS5 particle is covered with a titanium oxide surface layer which is several tens to hundreds of nanometers thick.

Figure 1. Cross-sectional TEM images of the composite positive electrode containing Li8FeS5-TiOx particles (A) High-angle annular dark field image, (B) STEM-EDS mappings for sulfur K-edge, iron K-edge, titanium K-edge, and oxygen K-edge. Scale bars: 100 nm.

Figure 2 shows an electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) spectrum of the titanium L edge. The EELS spectrum was acquired at the dotted square indicated in Figure 1A. Characteristic peaks related to titanium oxide are observed around 460 and 465 eV. In a previous study, these peaks were assigned as Ti2O3 or TiO (Akita et al., 2005).

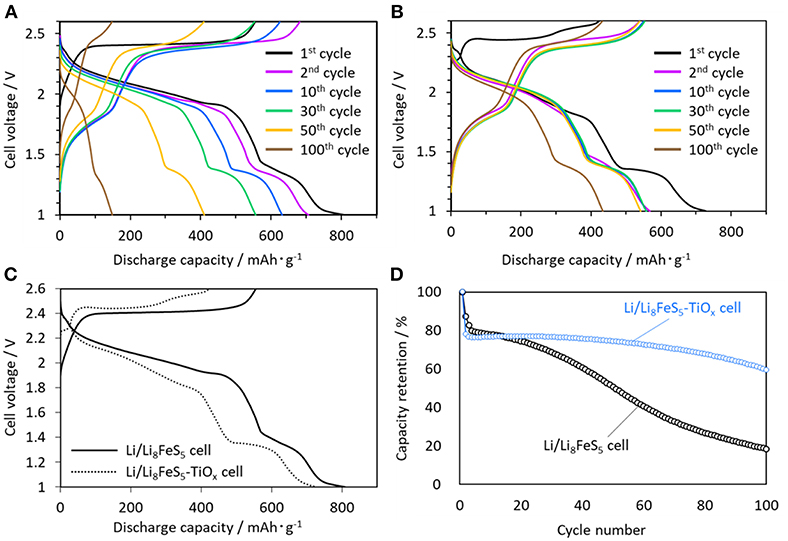

Figure 3 shows the charge-discharge curves of the Li/Li8FeS5 (Figure 3A) and Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cells (Figure 3B). Figure 3C compares the initial charge-discharge curves of the Li/Li8FeS5 cell and Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cells. Both cells shown two plateaus around 2.0 V vs. Li/Li+ and 1.4 V vs. Li/Li+ for the discharge process. In a previous study, it was concluded that the higher plateau around 2.0 V vs. Li/Li+ corresponds to sulfur redox, and the lower plateau around 1.4 V vs. Li/Li+ is related to the redox of the Fe-S component (Takeuchi et al., 2015). Figure 3D shows the capacity retention of the Li/Li8FeS5 and Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cells. The coating layer has effectively suppressed capacity fading for 100 cycles. However, the Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cell exhibits a relatively lower capacity than the Li/Li8FeS5 cell at the first discharge. Particularly, the plateau corresponding to sulfur redox during the discharge shrinks after coating and rapidly decreases at the beginning of the initial cycles.

Figure 3. Charge-discharge curves measured at 30°C, (A) Li/Li8FeS5 cell, (B) Li/Li8FeS5-Tix cell, (C) initial charge-discharge curves of the Li/Li8FeS5 cell and Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cell, (D) cycle performance of the Li/Li8FeS5 cell and Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cell.

There are several plausible reasons for the decrease in the discharge capacity of the Li8FeS5-TiOx sample cell. The first is the loss of sulfur during the coating process. In order to examine this quantitatively, we carried out ICP measurements for the Li8FeS5-TiOx sample powder; the measured atomic ratio was Li: Fe: S: Ti = 57: 7.0: 32: 4.1. Assuming that the coating layer consisted of only Ti and O, the core component was Li8.1Fe1.0S4.6. The slight loss of sulfur (ca. 8 at%) compared to its initial content (Li8FeS5) corresponds to a capacity loss of ca. 4% (corresponding to ca. 36 mAh·g−1 based on the theoretical capacity value). In addition, the weight of the coating layer (TiOx) might also decrease the apparent gravimetric capacity value. From the above result, the Li8FeS5-TiOx sample was considered to be 7Li8FeS5 · 2Ti2O3, assuming that the coating layer was Ti2O3. This corresponds to a weight ratio of Li8FeS5: Ti2O3 = 87: 13, and would decrease the capacity value by ca. 13% (corresponding to ca. 130 mAh·g−1 based on the theoretical capacity value), assuming that the capacity of coating Ti2O3 negligible in the present voltage range.

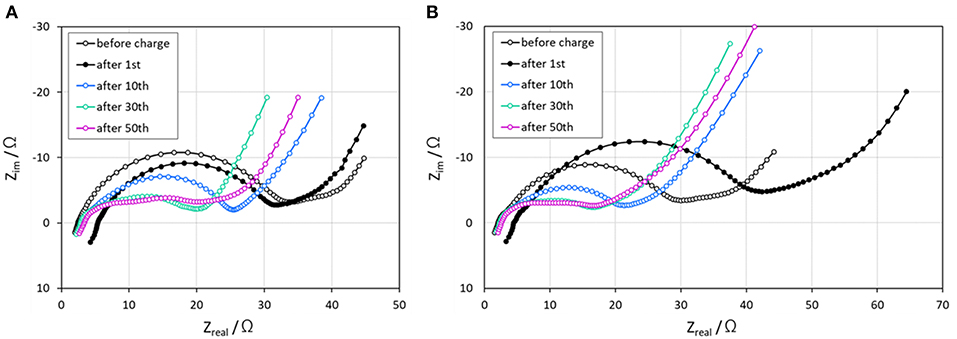

Moreover, an increase in the interfacial resistance at the electrode/electrolyte due to the TiOx coating might decrease the capacity value. Hence, we carried out AC impedance measurements for the Li8FeS5-TiOx sample cell to determine the influence of the coating layer on the cell resistance. Figure 4 shows the Nyquist plots of the Li/Li8FeS5 and Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cells. The semi-circle for the Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cell after the first cycle is relatively larger than that of the uncoated cell; the larger semi-circle at the low frequency region is related to surface reactions, such as the side reaction between lithium or sulfur and the surface layer. A high surface resistance would limit the utilization of the active material, and hence is responsible for the relatively lower initial capacity. However, the semi-circle for both cells exhibited a similar gradual reduction of size with the cycle number. Therefore, the effect of high interfacial resistance originating from the surface coating will be negligibly small after several cycles. Actually, the measured capacity loss after the TiOx coating was ca. 13% (ca. 100 mAh·g−1), as shown in Figure 3C. This may be explained by the above effects; primarily, the presence of the TiOx layer would be responsible for the loss of the initial gravimetric capacity value. After prolonged cycling, we have observed local-structure change of Li8FeS5 by XAFS analysis (Takeuchi et al., 2012) and tentatively conclude that the decrease in semi-circles after several cycles might correlate with the structural change of Li8FeS5.

Figure 4. Nyquist plots before charge, and after 1st, 10th, 30th, and 50th discharge, (A) Li/Li8FeS5 cell, (B) Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cell.

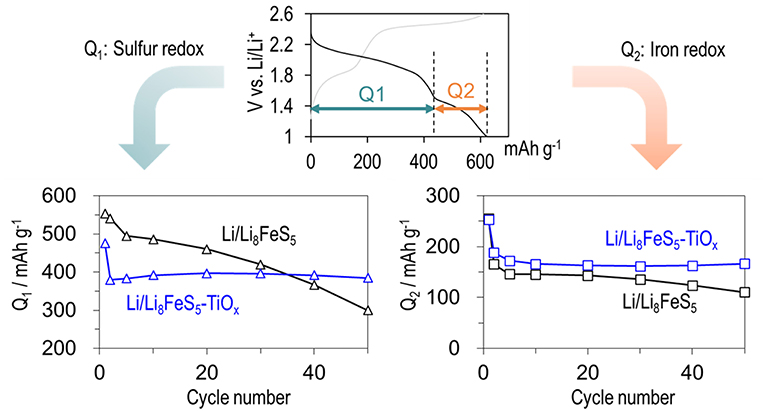

Further detailed analysis of the charge-discharge curves was conducted to clarify the reason for the improvement in the cycle property by coating. The capacity values corresponding to each plateau are plotted against the cycle number in Figure 5. The capacity values corresponding to a lower plateau (Q2) which related to redox capacity of the Fe-S component decrease with cycling for both sample cells; in particular, the capacity decreases more rapidly during the first 5 cycles. Figure 1 indicates that iron is only present in bulk particles. Therefore, the continuous capacity fading indicated that the fine structure around iron changed drastically during the initial cycles. In contrast, the degradation of the capacity values corresponding to the higher plateau (Q1) which correspond to sulfur redox was suppressed significantly after the surface coating. Specifically, excellent cycle stability was observed after the second cycle. Therefore, we can conclude that the surface reaction of Li8FeS5 with the electrolyte, which could be the main reason for cycle degradation related to sulfur deactivation, may have been suppressed by coating with the TiOx layer.

Figure 5. Cycle performance of Q1 corresponding to the sulfur redox capacity and Q2 which related to redox capacity of the Fe-S component. The black line represents the Li/Li8FeS5 cell and the blue line represents the Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cell.

In conclusion, Li8FeS5 was successfully surface-coated with titanium oxide by a liquid-phase reaction to prevent rapid capacity fading as a cathode material. By coating with TiOx, the Li/Li8FeS5-TiOx cells demonstrated considerable improvement in the cycle performance for a 100-cycle test. In addition, analysis of the charge-discharge curves indicated that the surface degradation related to sulfur deactivation was effectively suppressed by the TiOx coating.

EY wrote the manuscript and TT and HS revised the manuscript. EY designed the work and conducted the experiments. EY, TT, and HS contributed to the discussions about research results.

This work was financially supported by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) under the RISING2 project.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Akita, T., Okumura, M., Tanaka, K., Ohkuma, K., Kohyama, M., Koyanagi, T., et al. (2005). Transmission electron microscopy observation of the structure of TiO2 nanotube and Au/TiO2 nanotube catalyst. Surface and Interface Analysis. 37, 265–269. doi: 10.1002/sia.1979

Chen, C., Li, D., Gao, L., Harks, P. P., Eichelbd, R.-A., Notten, P. H. L., et al. (2017). Carbon-coated core–shell Li2S@C nanocomposites as high performance cathode materials for lithium–sulfur batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 5, 1428–1433. doi: 10.1039/C6TA09146F

Chianelli, R. R., and Dines, M. B. (1978). Low-temperature solution preparation of group 4B, 5B, and 6B transition-metal dichalcogenides. Inorg. Chem. 17, 2758–2762. doi: 10.1021/ic50188a014

Ding, B., Shen, L., Xu, G., Nie, P., and Zhang, X. (2013). Encapsulating sulfur into mesoporous TiO2 host as a high performance cathode for lithium–sulfur battery. Electrochim. Acta 107, 78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.06.009

Gao, J., Lowe, M. A., Kiya, Y., and Abruna, H. D. (2011). Effects of liquid electrolytes on the charge-discharge performance of rechargeable lithium/sulfur batteries: electrochemical and in-situ X-ray absorption spectroscopic studies. J. Phys. Chem. C. 115, 25132–25137. doi: 10.1021/jp207714c

Jayaprakash, N., Shen, J., Moganty, S. S., Corona, A., and Archer, L. A. (2011). Porous hollow carbon@sulfur composites for high-power lithium–sulfur batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 5904–5908. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100637

Li, C., Li, Z., Li, Q., Zhang, Z., Dong, S., and Yin, L. (2016). MOFs derived hierarchically porous TiO2 as effective chemical and physical immobilizer for sulfur species as cathodes for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Electrochem. Acta 215, 689–698. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.08.044

Lia, W., Zheng, G., Yang, Y., Seh, Z. W., Liu, N., and Cui, Y. (2013). High-performance hollow sulfur nanostructured battery cathode through a scalable, room temperature, one-step, bottom-up approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 7148–7153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220992110

Obrovac, M. N., and Dahn, J. R. (2002). Electrochemically active lithia/metal and lithium sulfide/metal composites. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 5, A70–A73. doi: 10.1149/1.1452482

Schuster, J., He, G., Mandlmeier, B., Yim, T., Lee, K. T., Bein, T., et al. (2012). Spherical ordered mesoporous carbon nanoparticles with high porosity for lithium–sulfur batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 3591–3595. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107817

Seh, Z. W., Yu, J. H., Li, W., Hsu, P. C., Wang, H., Sun, Y., et al. (2014). Two-dimensional layered transition metal disulphides for effective encapsulation of high-capacity lithium sulphide cathodes. Nat. Commun. 5:5017. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6017

Takeuchi, T., Kageyama, H., Nakanishi, K., Inada, Y., Katayama, M., Ohta, T., et al. (2012). Improvement of cycle capability of FeS2 positive electrode by forming composites with Li2S for ambient temperature lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 159, A75–A84. doi: 10.1149/2.026202jes

Takeuchi, T., Kageyama, H., Nakanishi, K., Ogawa, M., Ohta, T., Sakuda, A., et al. (2015). Preparation of Li2S-FeSx composite positive electrode materials and their electrochemical properties with pre-cycling treatments. J. Electrochem. Soc. 162, A1745–A1750. doi: 10.1149/2.0301509jes

Takeuchi, T., Kageyama, H., Taguchi, N., Nakanishi, K., Kawaguchi, T., Ohara, K., et al. (2018). Structure analyses of Fe-substituted Li2S-based positive electrode materials for Li-S batteries. Solid State Ionics 320, 287–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2018.03.028

Wang, C., Chen, J., Shi, Y., Zheng, M., and Dong, Q.-F. (2010). Preparation and performance of a core–shell carbon/sulfur material for lithium/sulfur battery. Electrochim. Acta 55, 7010–7015. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.06.019

Wei Seh, Z., Li, W., Cha, J. J., Zheng, G., Yang, Y., McDowell, M. T., et al. (2013). Sulphur–TiO2 yolk–shell nanoarchitecture with internal void space for long-cycle lithium–sulphur batteries. Nat. Commun. 4:1331. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2327

Xiao, Z., Yang, Z., Wang, L., Nie, H., Zhong, M., Lai, Q., et al. (2015). A lightweight TiO2/graphene interlayer, applied as a highly effective polysulfi de absorbent for fast, long-life lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 27, 2891–2898. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405637

Yan, Y., Lei, T., Jiao, Y., Wu, C., and Xiong, J. (2018). TiO2 nanowire array as a polar absorber for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Electrochim. Acta 264, 20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.01.038

Yang, Y., Yu, G., Cha, J. J., Wu, H., Vosgueritchian, M., Yao, Y., et al. (2011). Improving the performance of lithium-sulfur batteries by conductive polymer coating. ACS Nano. 5, 9187–9193. doi: 10.1021/nn203436j

Keywords: high-energy-density battery, lithium-sulfur battery, iron sulfide, surface coating, titanium oxide

Citation: Yamauchi E, Takeuchi T and Sakaebe H (2019) Improvement of Cycling Capability of Li2S-FeS Composite Positive Electrode Materials by Surface Coating With Titanium Oxide. Front. Energy Res. 7:38. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2019.00038

Received: 07 December 2018; Accepted: 22 March 2019;

Published: 18 April 2019.

Edited by:

Wen Liu, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Huan Pang, Yangzhou University, ChinaCopyright © 2019 Yamauchi, Takeuchi and Sakaebe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hikari Sakaebe, aGlrYXJpLnNha2FlYmVAYWlzdC5nby5qcA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.