94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Energy Res. , 02 May 2018

Sec. Bioenergy and Biofuels

Volume 6 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2018.00027

This article is part of the Research Topic Microbial Synthesis, Gas-Fermentation and Bioelectroconversion of CO2 and other Gaseous Streams View all 13 articles

Microalgae are most versatile organisms having ability to grow under diverse conditions and utilize both organic and inorganic carbon sources. Microalgal photosynthesis can be employed to transform carbon dioxide (CO2) into essential bioactives and photofuels. In this study, microalgal growth under modified headspace gas compositions which are CO2 + H2 (1:1), CO2, H2 and Air was evaluated to determine the photosynthetic efficiency and bioactives production. A marked enhancement was observed in quantum yield (Fv/Fm: 0.77) and CO2 biosequestration rate (0.39 g.L.-1d−1) under CO2 + H2 headspace gas condition as compared to the other experimental variations. The chemoselective functioning of Rubisco under varying gas concentrations was determined, where elevated CO2 conditions negate the oxygenase activity under a high CO2/O2 ratio which enabled higher CO2 sequestration. The enhanced CO2 sequestration and altered redox conditions through H2 addition under the monophasic operation have also led to a higher average degree of unsaturation (DU) and carbon chain length (CCL) of the fatty acids produced. This study provides an approach to augment photosynthetic efficiency and lipogenesis through non-genetic modifications along with the feasibility to cultivate microalgae in integration with industrial flue gases. Exploiting the true potential of microalgae would provide sustenance from climatic changes and environmental pollution concurrently producing biobased products analogous to the fossil-derived products.

Continuously converting the fossilized carbon into atmospheric CO2 through expeditious extraction and consumption has left the carbon loop unbalancd leading to adverse climate changes and a dearth of raw material (fossils) (Hoornweg et al., 2013; Dowson and Styring, 2017). With substantial increase in the world population, need for sustainable feedstocks has also increased. In the lookout for alternative feedstocks, CO2 has gained ground as a virtuous feedstock for the production of chemicals, fuels, and energy (Venkata Mohan et al., 2016a). Utilizing CO2 as feedstock through biotechnological routes has the potential to sustainably solve the problem of global climate change primarily occuring due to increase in atmospheric CO2 levels (Butti and Mohan, 2017; Kant, 2017). Increase in the atmospheric CO2 concentration has a harmful influence on the environment like acidification of oceans which develops a higher homeostasis stress on the phytoplaktons to maintain their redox conditions, acidification of soil, and acid rains (Rodrigues et al., 2016). Photosynthesis provides a possible solution with its natural ability to biocapture CO2 using solar energy and produce valuable chemicals along with several other advantages to mitigate environmental pollution (Benemann et al., 1977; Demars et al., 2016; Keenan et al., 2016).

Amongst the photosynthetic organisms microalgae have achieved higher significance as the primary responders to the climate change with their efficient carbon assimilation mechanism, high growth rate, bioactive, and biofuels production and the ability to grow on non-arable lands. Microalgae can grow under different trophic modes of nutrition and hence can be cultivated using both inorganic and organic carbon in light and dark conditions under photoautotrophic, mixotrophic, and heterotrophic modes (Venkata Mohan et al., 2014; Rohit and Mohan, 2015). Understanding these resourceful abilities several researchers have progressed toward microalgal photo-biotechnology encompassing biosequestration of CO2, wastewater treatment and biobased products synthesis. Different microalgal strains have robust capabilities to overcome climatic changes by CO2 sequestration and production of diverse products owing to their competent metabolism. However, through an integrated approach or genetic modifications the spectrum of products synthesized can be expanded like biocrude through hydrothermal liquefaction, bioalcohols through anaerobic digestion, bioelectricity through microbial electrochemical technologies, biohydrogen/biomethane through acidogenic fermentation, biofertilizers through pyrolysis (Perez-Garcia et al., 2011; Ooms et al., 2016; Venkata Mohan et al., 2016b). Under autotrophic mode of nutrition, substrate (CO2) availability governs the photosynthetic efficiency and biomass productivity at optimum operational parameters. The incidence of a positive influence on the biomass growth and lipogenesis under higher CO2 for different microalgal strains like Chlorella, Scenedesmus, Nannochloropsis, Dunaliella, Botryococcus, and plants has been previously discussed in different studies (Riebesell et al., 1993; Hein and Sand-Jensen, 1997; Chiu et al., 2009; Yoo et al., 2010; Price and Howitt, 2014; Peng et al., 2016a; Watson-Lazowski et al., 2016). Improving the energy conversion efficiency in photosynthesis is a multivariable problem, where, it is greatly influenced by an array of operational and physiological parameters like phases of operation, nutrients/substrate availability, photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) exposure, temperature, pH, the source of essential compounds and gases (industrial exhausts; Stewart et al., 2015; Chiranjeevi and Mohan, 2016).

We hypothesize that microalgae can be optimized to selectively enhance the carbon dioxide uptake and the photo-biocommodities productivity at an economic scale under photoautotrophic cultivation by regulating the inlet gas concentrations (10% CO2 + 10% H2, 20% CO2, 20% H2, 0.04% CO2) at an elevated pressure. The varying headspace gas concentrations would ensure controlled compartmentalization of essential metabolites and determine the possibility of selective photo-products synthesis. Also, in this study a monophasic cultivation strategy with a synergistic role of CO2 and H2 was incorporated taking lead from Gaffron who suggested the possibility of CO2 reduction by molecular hydrogen in microalgae (Gaffron, 1940). While most of the preceding studies in this domain have largely focused on varying the inlet concentrations of CO2 and operating in two phases with growth and stress phase separately. The present study has the potential to provide a holistic solution to the climate change and feedstock limitation through microalgal CO2 biosequestration and pave a sustainable path for the future generation.

The freshwater microalgae Chlorella sp. was isolated from a local ecological water body (Hussain Sagar, Hyderabad, 17.4239°N, 78.4738°E—India). Water samples were collected from five different locations around the banks of the lake, each sample was filtered through a 0.2 μm hydrophilic nylon membrane filter (Spin-pure, India), and the leftover residue was washed to remove non-biological components and it was suspended into BG11 culture media. Equal aliquots of the grown culture were sub-cultured in tapered opening glass screw-cap bottles (2 l, Borosil) tightly sealed to prevent contamination. The cultures were domesticated by providing a periodic input of sterile CO2 enriched air (0.4 l.min−1) at atmospheric pressure for 4 weeks enabling the adaptive evolution at the laboratory scale. Effective illumination was continuously provided by non-heating fluorescent white lights (95 μmol.m−2.s−1) measured by photon density lux meter (Extech LT-300 Light meter) with a photoperiod of 12 h. The reactors were operated in an open top reciprocal shaker (120 rpm) maintained at 25 ± 2°C and initial pH 8, this culture was labeled as pre-culture. A total of 10 ml pre-culture from suspension in log phase was added into autoclaved screw cap glass bioreactors (500 ml, Borosil) prefilled with modified BG11 growth medium which has the concentrations of nitrates (1.1 g.L−1), phosphates (0.03 g.L−1), and sulfates (0.060 g.L−1) with the other components same as the BG11 media. Pre-filled bioreactors were operated at the same operational conditions with a stepping increase in CO2 enriched air input (0.03–20% V/V) monitored by gas flow meter to acclimatize the pre-culture for high CO2 tolerance and uptake conditions for 4 weeks (only for CO2 and CO2 + H2 conditions). Homogeneity of species was confirmed microscopically (Nikon Eclipse-80i) and the images were captured on digital camera (YIM-smt, 5 MP) using NIS-elements (D3.0) software, primary observations suggest the occurrence of Chlorella sp.

The specifically designed photobioreactor (height 25 cm, base diameter 11 cm, opening diameter 5 cm, glass thickness 3 mm, equipped with separate sampling and gas exchange ports i.d/o.d-−0.9/1.1 and 0.4/0.64 mm, respectively) with the ability to sustain pressures of upto 2 bar and having maximum light penetration. The working volume of the reactor was 400 ml with an effective headspace of 100 ml. Four identical reactor setups were evaluated with specific sterile gases; CO2 (20% v/v), H2 (20% v/v), CO2 + H2 (20% v/v + 20% v/v), and Air (as control with 0.03% CO2 v/v) input with initial pH 8 (Table 1). The gas inputs were provided from GC grade gas cylinders through pneumatic pressure and flow control values to maintain constant pressure and flowrate in the reactors. The different inlet CO2, H2, and N2 gases concentrations in the reactors were monitored using gas chromatography with a thermal conductivity detector (Nucon-5765, Centurion Scientific, India) operated under specific conditions: packed (1/8″ × 2 m Heysep Q) column, injection volume 0.5 ml, argon as a carrier gas (47 ml.min−1), the injector and detector temperatures were maintained at 60°C and the oven was operated at 40°C isothermally. Culture and gas sampling were done through specifically provided ports using sterile needles on alternate days to determine the exponential growth, cellular components, carbon dioxide fixation, and occurrence of contamination was preventively monitored.

Microalgal samples were collected at every 48 h interval to evaluate growth by measuring optical density at 750 nm using a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Electron). Dry cell weight (g.L−1) was determined after the biomass was centrifuged twice at 10,000 rpm at 4°C for 5 min (XT/XF centrifuge, Thermo Scientific) the resulting pellet was washed twice with Milli-Q water and dried in hot air oven at 65°C for 24 h. The resulting biomass dry cell weight was used to calculate growth rate μ (g.L−1.d−1) as mentioned in Equation (1) (Cabanelas et al., 2016).

Where, DWtf and DWto represent dry cell weight of biomass (g.L−1), at time tf (the final sample time) and to (the initial sample time) in days respectively. Mean of the biomass concentrations was considered for measurement at specific time intervals.

The microalgal photosynthetic efficiency was evaluated using pulse-amplitude modulated fluorometry employing AquaPen-C (AP-C 100, Photon System Instruments, Czech Republic) which was monitored and controlled through PC using FluorPen software (PSI, Czech Republic). Chlorophyll fluorescence of PSII Quantum yield (Fv/Fm) was evaluated for samples directly withdrawn from the reactors after the biomass density was adjusted to 0.025 g.L−1 using MilliQ water and placed in a closed chamber for dark adaptation (10 min). The maximum quantum yield was calculated using Equation (2),

Where, the minimum fluorescence (F0) and maximum fluorescence (Fm) were determined after the samples were dark adapted and variable fluorescence (Fv) was determined according to calculation Fv = Fm – F0 which gives the fluorescence difference between the closed and open reaction centers in PSII under real time photosynthetic active radiation (PAR) (de Mooij et al., 2016).

The biomass at the end of the cycle was collected (10 ml), washed with MilliQ water twice and left overnight for drying in a glass crucible. The carbon content in the biomass was determined by the CHNS analyser (vario MICRO cube, Elementar). The relation between biomass productivity and carbon fixation rates (g.d−1.L−1), when cultivated under different CO2 concentrations, was determined by the Equation (3), average biomass productivities were considered (Gonçalves et al., 2016).

Where CC was the carbon content of the microalgal cells (% w/w), Pmax was the maximum biomass productivity (g.L−1.d−1), MCO2 was the molar mass of CO2 (44 g.mol−1), and MC was the molar mass of carbon (12 g.mol−1).

The total lipid content in the dry algal biomass was determined by the modified Bligh and Dyer method (Bligh and Dyer, 1959), where, 10 ml of 2:1 chloroform: methanol was added to 100 mg of dry biomass and sonicated at 40 KHz using probe Sonicator (Qsonica, Q55) for 2 min. Later, the solution is centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant was transferred into pre-weighed tubes and left overnight at 50°C in hot air oven. The neutral lipid content was determined using the same method with n-Hexane as the solvent (Venkata Mohan and Prathima Devi, 2012). The percentage gain in weight determined by the gravimetric means was used to conventionally quantify the total and neutral lipid content in the biomass. The lipid productivity in the batch culture was calculated using Equation (4) (Han et al., 2013).

Where, T was the culture time in days, Ct and Lt were the biomass concentration and lipid content at T and C0 and L0 were the initial biomass concentration and initial lipid content. Fatty acid composition was determined by acidic transesterification of the lipids using acid saturated methanol. The dried lipid was refluxed with acidified methanol for 2 h in hot water bath at 80°C. The esterified mixture was washed with ethyl acetate and water until the solution became alkaline. Later, it was filtered through an anhydrous Na2SO3 impregnated filter paper to remove moisture. The solvent recovery is done using rotary evaporator (Hei-VAP, Heidolph) and the pooled fame mix obtained is dissolved in chloroform and injected into GC for compositional analysis. The quantification of fatty acid methyl esters is done by GC-FID (Nucon-5765) with a capillary wax column (Valcobond 30 mm) using hydrogen as fuel and nitrogen as carrier gas. The oven temperature was initially maintained at 140°C later ramped to 240°C with 4°C/min increase, the detector and injector were maintained at 300 and 280°C, respectively with a split ratio of 1:10. Obtained FAME composition was compared to the standard FAME mix (C8-C22; LB66766, SUPELCO; Rohit and Mohan, 2015). The average carbon chain length (CCL) and average degree of unsaturation (DU) observed in the fatty acid profile were calculated using the equations

Where, CCL and DU represent the CCL and DU observed in the fatty acids synthesized, Ci and Di are the chain lengths and unsaturation of the particular fatty acid and FAi is the fatty acid abundance (Hoekman et al., 2012).

The carbohydrate content was determined by a phenol-sulfuric acid method where the pelleted biomass after centrifugation was powdered and dried (DuBois et al., 1956). The dry powder (10 mg) was acid hydrolyzed with 5 ml 2.5N HCl in a boiling water bath for 30 min. The solution volume is made upto 10 ml with distil-water, then centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min. To 0.2 ml of supernatant 1 ml 5% phenol solution and 5 ml 96% sulfuric acid is added. The contents are vortexed and placed in water bath for 20 min at 30°C later optical density was measured at 490 nm to determine the carbohydrate concentration.

Proteins were extracted from the microalgal cells using 0.5N NaOH for 24 h followed by heating upto 40°C followed by lysis buffer (Rausch, 1981; Fernández-Reiriz et al., 1989). Quantitative estimation of protein content in the biomass is determined by the Lowry's method (Lowry et al., 1951) and the nitrate removal is determined by the standard APHA methods (Chandra et al., 2015). Chlorophyll was estimated using spectrophotometry, the 10 ml of cell biomass was pelleted using a centrifuge at 5,000 rpm for 5 min. To the pellet 10 ml of acetone and ethanol (in 1:1 ratio) were added and sonicated at 40 kHz for 2 min using probes sonicator (Qsonica, Q55). The cell debris was separated by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 5 min, the resulting supernatant was used to quantify chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b by measuring the OD at 647 and 664 nm respectively using Equations (7–9) (Chiranjeevi and Mohan, 2016).

Redox conditions (pH) was continuously monitored (Eutech, Thermo Scientific) to determine the effective CO2 uptake and the dissolved inorganic carbon fraction in the media under elevated pressure and gas inputs.

The different experimental conditions are given codes for ease of understanding and are uniformly followed throughout the manuscript. Where, experimental variations with Air, CO2, CO2 + H2, and H2 are coded as AI, CC, CH, and HY, respectively based on the gas provided in the headspace. Correlative analysis of the photosynthetic activity and the cellular metabolite synthesis are delineated to understand the functional role of the specific gas inlets.

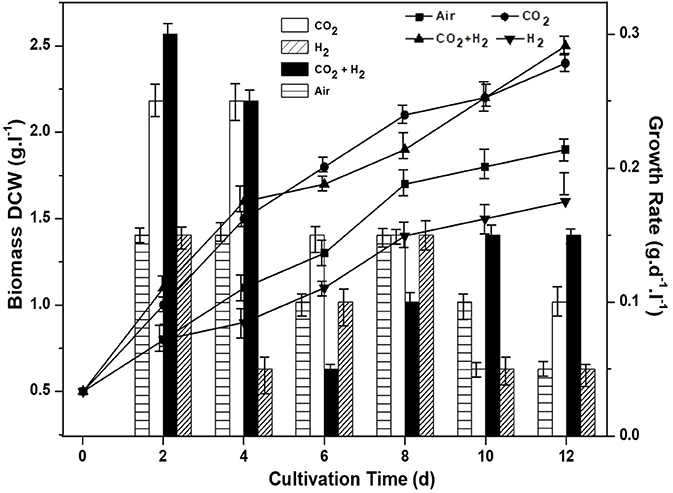

Biomass growth, quantum yield, CO2 fixation rate and chlorophyll pigment were monitored for all the experimental variations to assess the photosynthetic efficiency and understand the influence of controlled gas composition. CH condition has resulted in relatively higher biomass productivity of 2.5 g.L−1 with a positive growth rate of 0.3 g.d−1 on the 2nd day of cultivation. The maximum biomass growth was followed by CC, AI and HY with 2.3 g.L−1 (0.27 g.d−1), 1.9 g.L−1 (0.21 g.d−1), and 1.5 g.L−1 (0.17 g.d−1), respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Influence of specific gas inlet in the headspace on biomass concentration (g.L−1) and biomass productivity (g.L−1.d−1) of the microalgal cultures.

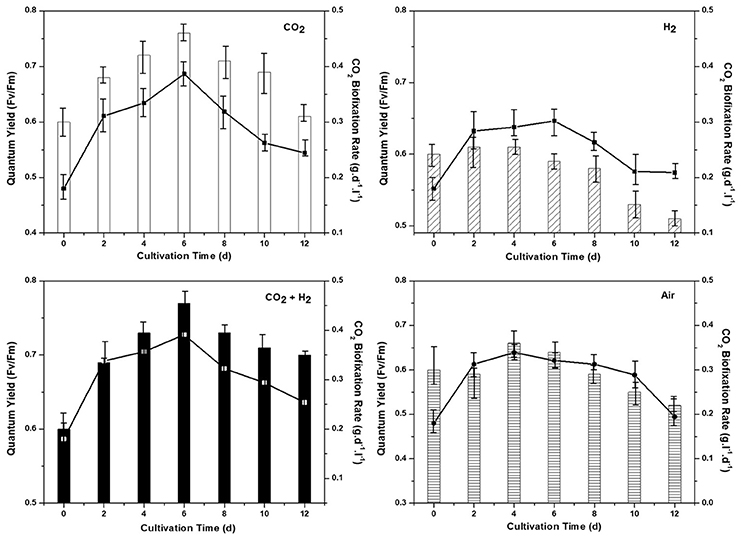

Biosequestration of CO2 was evaluated in correlation with the quantum yield for all the experimental conditions. Rate of CO2 sequestration was observed to be higher in the CH condition with 0.39 g.d−1 followed by CC (0.37 g.L−1d−1), AI (0.33 g.L−1d−1), and HY (0.30 g.L−1d−1) conditions respectively. The rate of CO2 sequestration is well in correlation with the biomass growth were higher CO2 uptake under the photoautotrophic conditions has led to higher biomass productivity. Efficiency of the photosynthetic machinery responsible for light energy harvestation is quantified by monitoring the quantum yield (Fv/Fm). Higher quantum yield was observed in CH- 0.77 followed by CC (0.75), AI (0.66), and HY (0.61) which supports the higher biomass growth and CO2 fixation rate (Figure 2). The marked increment in biomass productivity with CH condition might be attributed to the enhanced photosynthetic activity with the function of key photoautotrophic enzymes (carbonic anhydrase and Rubisco) associated with light reactions (Sun et al., 2016b). Enzymatic catalysis of CO2 into usable form is catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase which increases the dissolved inorganic carbon, augmenting its accessibility for the cellular metabolism under CH condition followed by CC, AI, and HY (Moroney and Ynalvez, 2007). Calvin cycle operates by utilizing the reducing energy generated during the light reactions (in form of NADH and ATP) for the reduction of CO2 catalyzed by Rubisco to form carbohydrates (Blankenship, 2002). Maintaining elevated CO2 gas concentrations in the CH and CC conditions, the CO2/O2 ratio gets escalated (compared to the ambient condition) thereby negating the oxygenase activity which has a detrimental effect on the CO2 uptake (Kitaya et al., 2003; Lohman et al., 2015; Mortensen and Gislerod, 2015). The improved uptake of CO2 through photocatalytic carbon fixation releases ADP and NAD+ rapidly making them readily available for accepting inorganic phosphorous and electrons by the electron transport chain thereby increasing the photosynthetic efficiency (correlating well with the quantum yields). The addition of H2 gas along with elevated CO2 maintains the cellular redox conditions with abundant proton concentrations that reduce the reactive oxygen species thereby increasing the photosynthetic efficiency as observed in CH condition. The increment in biomass productivity with elevated CO2 gas has been reported in different studies (Bowes, 1991; Hu and Gao, 2006; Mohammadi, 2016; Sun et al., 2016a). The supplementation of hydrogen along with higher CO2 also has a governing influence on higher biomass productivity and photosynthetic efficiency where hydrogen could be acting as an energy source as reported by Gaffron (1940). Apart from being an energy source it also maintains cellular redox conditions which allows the effective availability of dissolved inorganic carbon for uptake and reduces the reactive oxygen species (Gaffron, 1940; Cuellar-Bermudez et al., 2015). On the contrary, much higher levels of CO2 or H2 causes acidification below the optimal level thus causing decrement in microalgal growth. However, in the HY conditions the non-availability of carbon as compared to other conditions has resulted in lower biomass yields.

Figure 2. Quantum yield (Fv/Fm) of the dark adapted samples along with the chronological CO2 biofixation rate (g.l−1.d−1) for all the experimental conditions AI, CC, HY, and CH represent clockwise from top left.

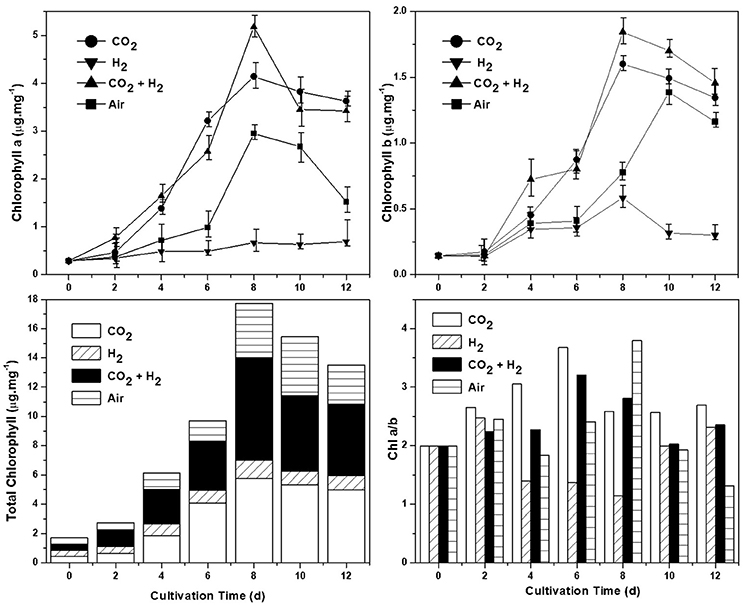

Chlorophyll content (both a and b) was estimated for all the experimental variations, as the primary light harvesting pigment it correlates with the photosynthetic efficiency. The total chlorophyll quantified was observed to be higher in CH followed by CC, AI, and HY conditions (Figure 3). High chlorophyll a concentration was observed in CH conditions during the eighth day of operation with 5.1 μ.mg−1 followed by CC, AI, and HY with 4.1, 2.9, and 0.66 μ.mg−1 respectively. Similar trends were observed in the case of chlorophyll b where CH (1.8 μ.mg−1) was quantified to be higher followed by CC (1.5 μ.mg−1), AI (1.3 μ.mg−1), and HY (0.58 μ.mg−1). Based on the mode of operation and nutrient availability the concentration of chlorophyll varies. Hence, the chlorophyll content showed a decremental trend toward the end of the cycle as the result of nitrate limitation and lower pH (Matich et al., 2016). The photosynthetic efficiency also correlates with the Chl a/b ratio as the chlorophyll a is the primary light harvesting pigment and chlorophyll b is the accessory pigment. Positive and higher chl a/b ratio symbolizes the effective photosynthetic activity and light conversion efficiency (Karpagam et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015). CH and CC showed ratio above 2, whereas, AI and HY showed ratio in between 1 and 2 correlating to the biomass productivity and quantum yields.

Figure 3. Chlorophyll estimation under different gas conditions determining the photosynthetic activity. Chlorophyll a (μg.mg−1), chlorophyll b (μg.mg−1), Chlorophyll a/b ratio, and total chlorophyll (μg.mg−1) are depicted clockwise from the top left.

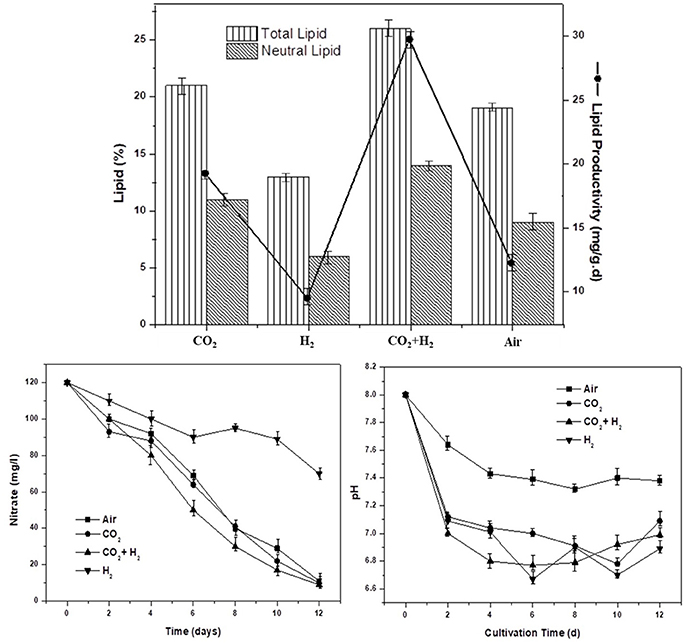

To understand the role of varying gas conditions (CH, AI, CC, and HY) on lipid biosynthesis. Total lipids, neutral lipids, and lipid productivity are evaluated in correlation with nitrate utilization and pH variation. The elevated CO2 levels enhanced the overall lipogenesis, possibly thorough the upregulated activities of acetyl CoA carboxylase and the fatty acid synthase complexes (Yasmin Anum Mohd Yusof et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011; Peng et al., 2016b). The total lipid content was observed to be higher in CH condition with 26% followed by CC, AI, and HY with 21, 19, and 13%, respectively. The trend of higher total lipids positively correlated with sufficient carbon supply and nitrate stress in the case of CH and CC compared to AI and HY. Single stage non-replete nitrogen conditions were employed in all the experimental conditions where, lower nitrogen (120 mg/l) was provided which enables simultaneous biomass growth and lipogenesis (Klok et al., 2013; Benavente-Valdés et al., 2016). The maximum lipid productivity of 29, 19, 12, and 9 mg.g−1.d−1 were observed in CH, CC, AI, and HY conditions, respectively. The nitrate removal showed a steady decremental trend in the CH, CC, and AI conditions compared to HY condition where the nitrate utilization was relatively lower (Velmurugan et al., 2014). The nitrates concentrations dropped from 120 mg/l at the initial day of operation to 10 ± 1 mg/l at the end of operation in CH, CC, and AI conditions, whereas in the HY condition the concentration has only dropped to 70 mg/l which explains the lower biomass as well as lipid productivity. Carbon availability has played the major role in lipid synthesis under CH condition followed by CC and AI as the nitrate utilization trend is similar (Figure 4). Initial pH was setup at 8.0 to increase the system buffering at elevated CO2 and H2 conditions. The pH was observed to drop in all the conditions from 8 to 6.89, 6.99, 7.09, and 7.38 in HY, CH, CC, and AI, respectively (Figure 4). The nutrient stress in the form nitrogen limitation and pH variations governed the lipogenesis along with carbon availability.

Figure 4. The total lipid and neutral lipid contents in the dry biomass at the end of the cycle along with specific lipid productivity (mg.g−1.d−1) under nutrient and redox stress are depicted for the varied gas concentrations in the headspace.

The elevated CO2 gas concentrations have a governing influence on the lipogenic enzymes (phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, and pyruvate carboxylase) along with anaplerotic carbon assimilation reactions which could have catalyzed the enhanced lipid synthesis (Peng et al., 2016b). The intracellular and extracellular redox conditions have a marked influence on the neutral lipids synthesis which are primarily storage lipids (TAGs and esters; Juneja et al., 2013). The neutral lipids were dominant under the CH condition followed by CC, AI, and HY condition with 14, 11, 9, and 6%, respectively. Under acidic conditions, to limit the proton gradient across the cell membrane, the microalgal cells discontinue the membrane polar lipid synthesis, and surge the storage lipid synthesis which are primarily neutral lipids (Juneja et al., 2013). The role of pH apart from governing the lipogenesis is also to regulate the carbonaceous species availability for cellular metabolism, where at high alkaline pH the carbon is in the inaccessible form of carbonates (Azov, 1982).

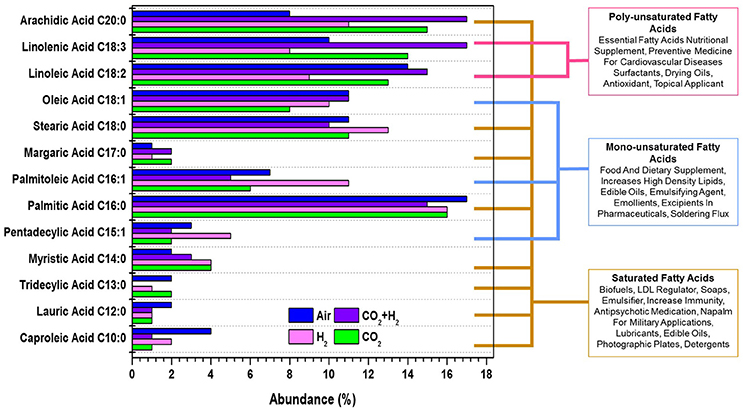

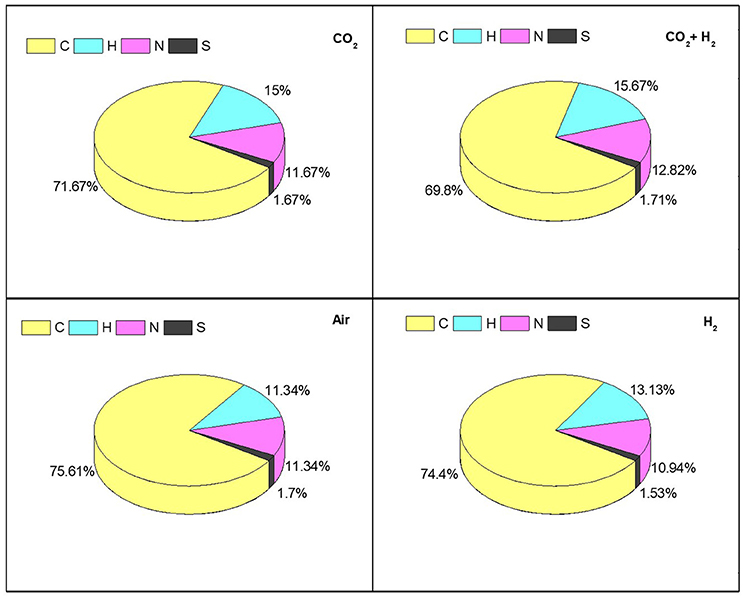

Transesterified fatty acid profile of the lipids produced in all the experimental conditions were quantified to determine the photofuels and bioactive compounds production under each experimental variation. The Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME) composition showed synthesis of fatty acids with CCL ranging from C10 to C20 and having unsaturation (mono/poly). Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA; C18:3 and C18:2) were observed with relative abundance of 17 and 15%, 14 and 13%, 10 and 14%, and 8 and 9% in CH, CC, AI, and HY conditions, respectively (Figure 5). PUFA have a multitude of applications as bioactive compounds that are of high nutrient value, edible oil supplements, pharmaceutical precursors which help in lowering cardiovascular diseases apart from being used as a intermediates for various industrial chemicals. Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA; C18:1, C16:1, and C15:1) were observed, amongst which C18:1 was quantitatively higher in the case of CH and AI (11%) followed by HY (10%) and lowest was observed in CC (8%). C18:1 fatty acids has a property of being used as a food and dietary supplement and pharmaceutical ingredient. C16:1 and C15:1 were observed to have relative abundance of 11 and 5%, 7 and 3%, 6 and 2%, and 5 and 2% in the case of CH, AI, CC, and HY, respectively which have fuel properties and is applied in detergent industries as emulsifiers and also as a cosmetics for topical application. Saturated Fatty Acids (SFA; C18:0, C16:0, and C20:0) are relatively higher along with low concentrations of fatty acids like C14:0, C13:0, C12:0, and C10:0. The quantitative variations in C18:0, C16:0, and C20:0 are 11, 16, and 15% in the case of CC, 13, 16, and 11% in the case of HY, 10, 15, and 17% in the case of CH and 11, 17, and 8% in the case of AI, respectively. SFAs find application as biofuels, soaps, medicines, military lubricants and photographic plates. The lipogenic potential of microalgae is observed to be regulated through CO2 and H2 variation enabling the selective production of photofuels and bioactive compounds which have a significant role in developing a sustainable future analogous to the petroleum based precursor chemicals.

Figure 5. Fatty acid methyl esters profile showing the variations in the photofuels and bioactive compounds synthesis abundance with the function of varying gas compositions is presented for all experimental variations.

The average CCL was observed to be higher in the case of CH condition with 17.58 followed by CC with 17.33, HY with 17 and AI with 16.84. Along with the variations in chain length the additional CO2 and H2 influenced the DU observed in the fatty acids. Average DU was quantified, which portrayed higher unsaturation in the case of CH (0.99) followed by CC (0.88), AI (0.85), and HY (0.73). Though the variations in the average CCL is modest, a noteworthy influence of elevated CO2 and H2 was observed on the DU. The supplementation of CO2 influenced the shift of saturated fatty acids toward unsaturation which could be to maintain the membrane fluidity allowing efficient CO2 uptake. Most of the unsaturated fatty acids are membrane bound lipids and hence the increase in unsaturation could be observed in the CH, HY, and CC conditions sequentially as compared to AI. The predominant shifts of saturated fatty acid to unsaturated fatty acids was observed in C18:0 fatty acid to C18:1, C18:2, and C18:3 fatty acids (Table 2). Similar trends of unsaturation under elevated CO2 conditions were reported in different studies with microalgae, which suggested the upregulation of desaturase enzymes catalytic activity that results in more of unsaturation (Tsuzuki et al., 1990; Nagaich et al., 2014; Cuellar-Bermudez et al., 2015). However, the lowering of pH has shown an increase in the saturated fatty acids that is specifically observed in the change of C18 and C16 fatty acids which could protect the cells from the extracellular low pH (Santos et al., 2014). Total SFA:MUFA:PUFA was observed to be 47:18:32 in the case of CH, 49:21:17 in the case of HY, 51:16:27 in the case of CC and 47:14:24 in the case of AI depicting an increased chain length and unsaturation of fatty acids in the case of CH (Yasmin Anum Mohd Yusof et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011).

Table 2. FAME compositional distribution with desaturation, average carbon chain length, average degree of unsaturation for lipids extracted from samples grown under different headspace gas concentrations.

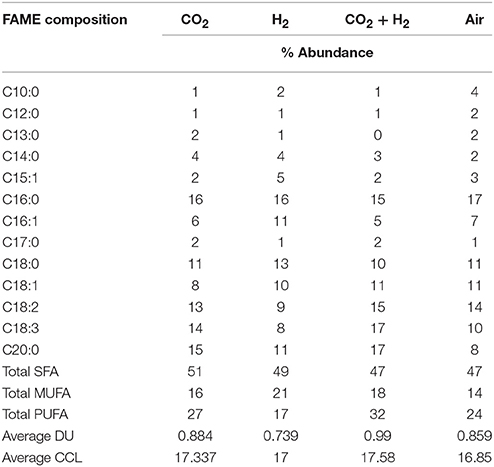

Under photoautotrophy the primary metabolites synthesized are carbohydrates and proteins which serve as the energy source for cellular metabolism in dark/stress conditions. The carbohydrate synthesis has shown a linear increase with time correlating to the photosynthetic activity, as the energy for CO2 hydrogenation catalyzed by Rubisco is drawn from the light reactions and supplemented hydrogen. Relatively higher carbohydrates synthesis was observed in CH conditions (274 mg.g−1; 8th day) followed by CC (243 mg.g−1; 9th day), AI (197 mg.g−1; 9th day), and HY (120 mg.g−1; 8th day) which has correlating trends with photosynthetic activities and CO2 fixation. Post the maximum productivity carbohydrate concentration showed a decremental trend in all the conditions with 231, 180, 174, and 101 mg.g−1 in CH, CC, AI, and HY conditions, respectively. The decrease in carbohydrate concentration maybe due to its consumption for lipids synthesis under stress conditions correlating with nutrient uptake and lowering of pH conditions (Figure 6). Proteins are synthesized during biomass growth most of which are essential enzymes, membrane bound electron shuttlers and redox mediators required for the cellular functioning. The higher protein levels were observed in CH followed by AI, CC, and HY conditions with 48, 46, 45, and 26 mg.g−1, respectively. Owing to the reduced biomass growth during the nutrient stress conditions the protein concentrations have also shown a decrement in concentrations toward the end of the operation reaching 24, 37, 43, and 44 mg.g−1 in HY, CC, AI, and CH conditions, respectively.

Figure 6. Cellular biochemicals carbohydrates (mg.g−1) and proteins (mg.g−1) synthesis under different gas concentrations is depicted for all the experimental variations.

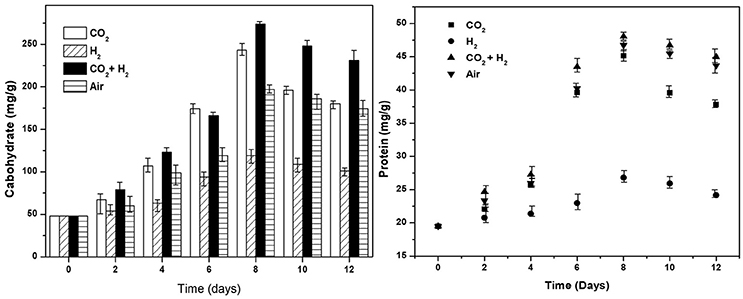

The dry algal biomass at the end of the experiment was analyzed to determine the carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur distribution for all the experimental conditions (Figure 7). The carbon and hydrogen distribution correlates with the carbohydrate synthesis and CO2 fixation as the reactors are operated in photoautotrophic mode of nutrition amounting to 85 ± 1% of the total elemental composition in all the experimental conditions. The distribution of nitrogen was modestly varying in CH (12.82%) compared to the other CC, AI, and HY (11 ± 0.5%) conditions which could be the result of enhanced protein synthesis in CH condition supporting the hypothesis that elevated CO2 inlets under photoautotrophic mode resemble the heterotrophic mode of nutrition. The sulfur content showed similar distribution (1.5 ± 0.2%) amongst all the experimental variations (Gonçalves et al., 2016). The increase in CO2 uptake had the influence on the carbon accumulation along with the protein synthesis which govern the C:N distribution of the biomass.

Figure 7. Determining the relative abundance of CHNS influenced by photosynthetic activity and CO2 sequestration trough elemental composition analysis for individual specific gas inlet variations.

Present study shows the possibilities of selectively producing microalgal based bioactives and photofuels from industrial effluent gasses. The influence of elevated CO2 and H2 gas concentrations on both biomass growth and lipogenesis was specifically evident from the fatty acids compositions and the quantum yield. This study unwraps the possibility of cultivating microalgae in integration with industrial effluent treatment by utilizing the flue gases with low investments and also help in generating additional revenue, making the process economically feasible. However, deeper insights for growth and metabolite regulation in photosynthesis can be determined through molecular level quantification and transcriptomics of the targeted proteins/enzymes. The recent advances in photosynthetic research provide a ray of hope to overcome climate change and progress toward sustainable development with the multifaceted applications of microalgae.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

SKB acknowledges University Grants Commission (UGC) for providing research fellowship.

Azov, Y. (1982). Effect of pH on inorganic carbon uptake in algal cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43, 1300–1306.

Benavente-Valdés, J. R., Aguilar, C., Contreras-Esquivel, J. C., Méndez-Zavala, A., and Montañez, J. (2016). Strategies to enhance the production of photosynthetic pigments and lipids in chlorophycae species. Biotechnol. Rep. 10, 117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2016.04.001

Benemann, J. R., Weissman, J. C., Koopman, B. L., and Oswald, W. J. (1977). Energy production by microbial photosynthesis. Nature 268, 19–23. doi: 10.1038/268019a0

Blankenship, R. E. (2002). “The basic principles of photosynthetic energy storage,” in Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science Ltd.), 1–10.

Bligh, E. G., and Dyer, W. J. (1959). A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917. doi: 10.1139/y59-099

Bowes, G. (1991). Growth at elevated CO2: photosynthetic responses mediated through Rubisco. Plant. Cell Environ. 14, 795–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1991.tb01443.x

Butti, S. K., and Mohan, S. V. (2017). Autotrophic biorefinery: dawn of the gaseous carbon feedstock. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 364, 1–8. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx166

Cabanelas, I. T., van der Zwart, M., Kleinegris, D. M., Wijffels, R. H., and Barbosa, M. J. (2016). Sorting cells of the microalga Chlorococcum littorale with increased triacylglycerol productivity. Biotechnol. Biofuels 9:183. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0595-x

Chandra, R., Arora, S., Rohit, M. V., and Venkata Mohan, S. (2015). Lipid metabolism in response to individual short chain fatty acids during mixotrophic mode of microalgal cultivation: influence on biodiesel saturation and protein profile. Bioresour. Technol. 188, 169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.01.088

Chiranjeevi, P., and Mohan, S. V. (2016). Critical parametric influence on microalgae cultivation towards maximizing biomass growth with simultaneous lipid productivity. Renew. Energy 98, 64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2016.03.063

Chiu, S.-Y., Kao, C.-Y., Tsai, M.-T., Ong, S.-C., Chen, C.-H., and Lin, C.-S. (2009). Lipid accumulation and CO2 utilization of Nannochloropsis oculata in response to CO2 aeration. Bioresour. Technol. 100, 833–838. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.06.061

Cuellar-Bermudez, S. P., Romero-Ogawa, M. A., Vannela, R., Lai, Y. S., Rittmann, B. E., and Parra-Saldivar, R. (2015). Effects of light intensity and carbon dioxide on lipids and fatty acids produced by Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 during continuous flow. Algal Res. 12, 10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2015.07.018

Demars, B. O. L., Gislason, G. M., Olafsson, J. S., Manson, J. R., Friberg, N., Hood, J. M., et al. (2016). Impact of warming on CO2 emissions from streams countered by aquatic photosynthesis. Nat. Geosci. 9, 758–761. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2807

de Mooij, T., de Vries, G., Latsos, C., Wijffels, R. H., and Janssen, M. (2016). Impact of light color on photobioreactor productivity. Algal Res. 15, 32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2016.01.015

Dowson, G. R. M., and Styring, P. (2017). Demonstration of CO2 conversion to synthetic transport fuel at flue gas concentrations. Front. Energy Res. 5:26. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2017.00026

DuBois, M., Gilles, K. A., Hamilton, J. K., Rebers, P. A., and Smith, F. (1956). Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 28, 350–356. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017

Fernández-Reiriz, M. J., Perez-Camacho, A., Ferreiro, M. J., Blanco, J., Planas, M., Campos, M. J., et al. (1989). Biomass production and variation in the biochemical profile (total protein, carbohydrates, RNA, lipids and fatty acids) of seven species of marine microalgae. Aquaculture 83, 17–37. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(89)90057-4

Gaffron, H. (1940). Carbon dioxide reduction with molecular hydrogen in green algae. Am. J. Bot. 27, 273–283. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1940.tb14683.x

Gonçalves, A. L., Rodrigues, C. M., Pires, J. C. M., and Simões, M. (2016). The effect of increasing CO2 concentrations on its capture, biomass production and wastewater bioremediation by microalgae and cyanobacteria. Algal Res. 14, 127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2016.01.008

Han, F., Huang, J., Li, Y., Wang, W., Wan, M., Shen, G., et al. (2013). Enhanced lipid productivity of Chlorella pyrenoidosa through the culture strategy of semi-continuous cultivation with nitrogen limitation and pH control by CO2. Bioresour. Technol. 136, 418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.017

Hein, M., and Sand-Jensen, K. (1997). CO2 increases oceanic primary production. Nature 388, 526–527. doi: 10.1038/41457

Hoekman, S. K., Broch, A., Robbins, C., Ceniceros, E., and Natarajan, M. (2012). Review of biodiesel composition, properties, and specifications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 143–169. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2011.07.143

Hoornweg, D., Bhada-tata, P., and Kennedy, C. (2013). Waste production must peak this century. Nature 502, 615–617. doi: 10.1038/502615a

Hu, H., and Gao, K. (2006). Response of growth and fatty acid compositions of Nannochloropsis sp. to environmental factors under elevated CO2 concentration. Biotechnol. Lett. 28, 987–992. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9026-6

Juneja, A., Ceballos, R., and Murthy, G. (2013). Effects of environmental factors and nutrient availability on the biochemical composition of algae for biofuels production: a review. Energies 6, 4607–4638. doi: 10.3390/en6094607

Kant, M. (2017). Overcoming barriers to successfully commercializing carbon dioxide utilization. Front. Energy Res. 5:22. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2017.00022

Karpagam, R., Preeti, R., Ashokkumar, B., and Varalakshmi, P. (2015). Enhancement of lipid production and fatty acid profiling in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, CC1010 for biodiesel production. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 121, 253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.03.015

Keenan, T. F., Prentice, I. C., Canadell, J. G., Williams, C., Wang, H., Raupach, M. R., et al. (2016). Recent pause in the growth rate of atmospheric CO2 due to enhanced terrestrial carbon uptake. Nat. Commun. 7:13428. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13428

Kitaya, Y., Okayama, T., Murakami, K., and Takeuchi, T. (2003). Effects of CO2 concentration and light intensity on photosynthesis of a rootless submerged plant, Ceratophyllum demersum L., used for aquatic food production in bioregenerative life support systems. Adv. Space Res. 31, 1743–1749. doi: 10.1016/S0273-1177(03)00113-3

Klok, A. J., Martens, D. E., Wijffels, R. H., and Lamers, P. P. (2013). Simultaneous growth and neutral lipid accumulation in microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 134, 233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.02.006

Li, D., Wang, L., Zhao, Q., Wei, W., and Sun, Y. (2015). Improving high carbon dioxide tolerance and carbon dioxide fixation capability of Chlorella sp. by adaptive laboratory evolution. Bioresour. Technol. 185, 269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.03.011

Lohman, E. J., Gardner, R. D., Pedersen, T., Peyton, B. M., Cooksey, K. E., and Gerlach, R. (2015). Optimized inorganic carbon regime for enhanced growth and lipid accumulation in Chlorella vulgaris. Biotechnol. Biofuels 8:82. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0265-4

Lowry, O. H., Rosebrough, N. J., Farr, A. L., and Randall, R. J. (1951). Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275.

Matich, E. K., Butryn, D. M., Ghafari, M., del Solar, V., Camgoz, E., Pfeifer, B. A., et al. (2016). Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics of value-added biochemicals from Ettlia oleoabundans. Algal Res. 19, 146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2016.08.009

Mohammadi, F. S. (2016). Investigation of effective parameters on biomass and lipid productivity of Chlorella vulgaris. Period. Biol. 118, 123–129. doi: 10.18054/pb.2016.118.2.3197

Moroney, J. V., and Ynalvez, R. A. (2007). Proposed carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot. Cell 6, 1251–1259. doi: 10.1128/EC.00064-07

Mortensen, L. M., and Gislerod, H. R. (2015). The growth of as influenced by high CO and low O in flue gas from a silicomanganese smelter. J. Appl. Phycol. 27, 633–638. doi: 10.1007/s10811-014-0357-8

Nagaich, V., Dongre, S. K., Singh, P., Yadav, M., and Tiwari, A. (2014). Maximum-CO2 tolerance in microalgae : possible mechanisms and higher lipid accumulation. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2, 101–106.

Ooms, M. D., Dinh, C. T., Sargent, E. H., and Sinton, D. (2016). Photon management for augmented photosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 7:12699. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12699

Peng, H., Wei, D., Chen, F., and Chen, G. (2016a). Regulation of carbon metabolic fluxes in response to CO2 supplementation in phototrophic Chlorella vulgaris: a cytomic and biochemical study. J. Appl. Phycol. 28, 737–745. doi: 10.1007/s10811-015-0542-4

Peng, H., Wei, D., Chen, G., and Chen, F. (2016b). Transcriptome analysis reveals global regulation in response to CO2 supplementation in oleaginous microalga Coccomyxa subellipsoidea C-169. Biotechnol. Biofuels 9, 1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0571-5

Perez-Garcia, O., Escalante, F. M., de-Bashan, L. E., and Bashan, Y. (2011). Heterotrophic cultures of microalgae: metabolism and potential products. Water Res. 45, 11–36. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.08.037

Price, G. D., and Howitt, S. M. (2014). Plant science: towards turbocharged photosynthesis. Nature 513, 497–498. doi: 10.1038/nature13749

Rausch, T. (1981). The estimation of micro-algal protein content and its meaning to the evaluation of algal biomass I. Comparison of methods for extracting protein. Hydrobiologia 78, 237–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00008520

Riebesell, U., Wolf-Gladrow, D. A., and Smetacek, V. (1993). Carbon dioxide limitation of marine phytoplankton growth rates. Nature 361, 249–251. doi: 10.1038/361249a0

Rodrigues, W. P., Martins, M. Q., Fortunato, A. S., Rodrigues, A. P., Semedo, J. N., Simões-Costa, M. C., et al. (2016). Long-term elevated air [CO2] strengthens photosynthetic functioning and mitigates the impact of supra-optimal temperatures in tropical Coffea arabica and C. canephora species. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 415–431. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13088

Rohit, M. V., and Mohan, S. V. (2015). Tropho-metabolic transition during Chlorella sp. cultivation on synthesis of biodiesel. Renew. Energy 98, 84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2016.03.041

Santos, A. M., Wijffels, R. H., and Lamers, P. P. (2014). PH-upshock yields more lipids in nitrogen-starved Neochloris oleoabundans. Bioresour. Technol. 152, 299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.10.079

Stewart, J. J., Bianco, C. M., Miller, K. R., and Coyne, K. J. (2015). The marine microalga, heterosigma akashiwo, converts industrial waste gases into valuable biomass. Front. Energy Res. 3:12. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2015.00012

Sun, Z., Chen, Y. F., and Du, J. (2016a). Elevated CO2 improves lipid accumulation by increasing carbon metabolism in Chlorella sorokiniana. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 557–566. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12398

Sun, Z., Dou, X., Wu, J., He, B., Wang, Y., and Chen, Y. F. (2016b). Enhanced lipid accumulation of photoautotrophic microalgae by high-dose CO2 mimics a heterotrophic characterization. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11274-015-1963-6

Tsuzuki, M., Ohnuma, E., Sato, N., Takaku, T., and Kawaguchi, A. (1990). Effects of CO2 concentration during growth on fatty acid composition in microalgae. Plant Physiol. 93, 851–856. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.3.851

Velmurugan, N., Sung, M., Yim, S. S., Park, M. S., Yang, J. W., and Jeong, K. J. (2014). Systematically programmed adaptive evolution reveals potential role of carbon and nitrogen pathways during lipid accumulation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biotechnol. Biofuels 7:117. doi: 10.1186/s13068-014-0117-7

Venkata Mohan, S., Modestra, J. A., Amulya, K., Butti, S. K., and Velvizhi, G. (2016a). A circular bioeconomy with biobased products from CO2 sequestration. Trends Biotechnol. 34, 506–519. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.02.012

Venkata Mohan, S., Nikhil, G. N., Chiranjeevi, P., Nagendranatha Reddy, C., Rohit, M. V., Kumar, A. N., et al. (2016b). Waste biorefinery models towards sustainable circular bioeconomy: critical review and future perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 215, 2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.03.130

Venkata Mohan, S., and Prathima Devi, M. (2012). Fatty acid rich effluent from acidogenic biohydrogen reactor as substrate for lipid accumulation in heterotrophic microalgae with simultaneous treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 123, 627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.07.004

Venkata Mohan, S., Rohit, M. V., Chiranjeevi, P., Chandra, R., and Navaneeth, B. (2014). Heterotrophic microalgae cultivation to synergize biodiesel production with waste remediation: progress and perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 184, 169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.10.056

Watson-Lazowski, A., Lin, Y., Miglietta, F., Edwards, R. J., Chapman, M. A., and Taylor, G. (2016). Plant adaptation or acclimation to rising CO2? Insight from first multigenerational RNA-Seq transcriptome. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 3760–3773. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13322

Yasmin Anum Mohd Yusof, Y. A. M., Basari, J. H., Mukti, N. A., Sabuddin, R., Muda, A. R., Sulaiman, S., et al. (2011). Fatty acids composition of microalgae Chlorella vulgaris can be modulated by varying carbon dioxide concentration in outdoor culture. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10, 13536–13542. doi: 10.5897/AJB11.1602

Yoo, C., Jun, S.-Y., Lee, J.-Y., Ahn, C.-Y., and Oh, H.-M. (2010). Selection of microalgae for lipid production under high levels carbon dioxide. Bioresour. Technol. 101, S71–S74. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.03.030

Keywords: photoautotrophy, quantum yield, CO2 biosequestration, biorefinery, FAME, CO2 fixation rate, biohydrogen

Citation: Butti SK and Venkata Mohan S (2018) Photosynthetic and Lipogenic Response Under Elevated CO2 and H2 Conditions—High Carbon Uptake and Fatty Acids Unsaturation. Front. Energy Res. 6:27. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2018.00027

Received: 22 October 2017; Accepted: 28 March 2018;

Published: 02 May 2018.

Edited by:

Deepak Pant, Flemish Institute for Technological Research, BelgiumReviewed by:

Ahmed ElMekawy, University of Sadat City, EgyptCopyright © 2018 Butti and Venkata Mohan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: S. Venkata Mohan, c3Ztb2hhbkBpaWN0LnJlcy5pbg==; dm1vaGFuX3NAeWFob28uY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.