- 1Department of Oncology, Seventh People’s Hospital of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 2Department of Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 3Department of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, China

Objective: The aim of this study was to investigate the bidirectional causal relationship between sex hormones and IBD through a two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR) study.

Methods: Based on Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) pooled data on SHBG, total testosterone, bioavailable testosterone, estradiol, and IBD in a European population, we performed two-sample bidirectional MR analyses using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables. We used inverse variance weighting (IVW), weighted median, weighted mode, and MR-Egger to assess bidirectional causality between sex hormones and IBD.

Results: There was no causal relationship between sex hormones and IBD in women (P > 0.05), and there was a causal and positive correlation between SHBG and testosterone and IBD in men.The OR for SHBG was 1.22 (95% CI: 1.09-1.37, P = 0.0004), and for testosterone was 1.20 (95% CI: 1.04-1.39, P = 0.0145).IBD did not significantly interact with female sex hormones but resulted in a decrease in SHBG (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.00-1.04, P = 0.0195) and testosterone (OR = 1.01, 95% CI: 1.00 -1.02, P = 0.0200) in men.

Conclusion: There is no causal relationship between female sex hormones and IBD, but male SHBG and testosterone are positively correlated with the risk of IBD and IBD promotes elevated levels of SHBG and testosterone in males, suggesting that sex hormones play different roles in IBD patients of different sexes.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), and its prevalence has been steadily increasing in recent years (1). The development of IBD is a complex process influenced by both environmental and genetic factors (2). Previous studies have reported a disparity in the prevalence of IBD between men and women, with a higher incidence observed in men (3). A meta-analysis further supports this finding, revealing a predominant male predominance among adult IBD patients (4). Recent studies have indicated that sex hormones possess the ability to modulate the progression of IBD and impact its development (5). Furthermore, individuals utilizing hormone replacement therapy, which includes sex hormones, have been observed to exhibit a reduced risk of developing IBD (6). IBD may also impact the production of sex hormones. A study revealed that adolescent boys with IBD had delayed puberty and growth, which showed improvement upon taking androgens (7, 8).

The progression of IBD has been shown to interfere with the regulation of hormone production in the body. For instance, a study demonstrated that mice with early-stage DSS-induced enterocolitis exhibited significantly smaller seminal vesicles and reduced levels of circulating androgens (9). Similarly, male patients with CD were found to have markedly lower serum levels of testosterone, estradiol, and sex hormone-binding globulin compared to healthy individuals (10). These findings highlight a potential link between sex hormones and IBD, suggesting reciprocal interactions. However, the precise causal relationship and underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Mendelian randomization (MR) is an analytical method used to assess causality by utilizing genetic variants that are closely associated with exposure as instrumental variables (IVs) (11, 12). This method is advantageous in minimizing confounding factors, as the categorization of genetic variants occurs randomly at the time of conception and is independent of environmental influences. Now for sex hormones and IBD no one has studied them using Mendelian randomization. Therefore, in this study we aimed to investigate the potential bidirectional causal relationship between IBD and sex hormones by MR analysis of pooled data from two samples.

Methods

Data sources

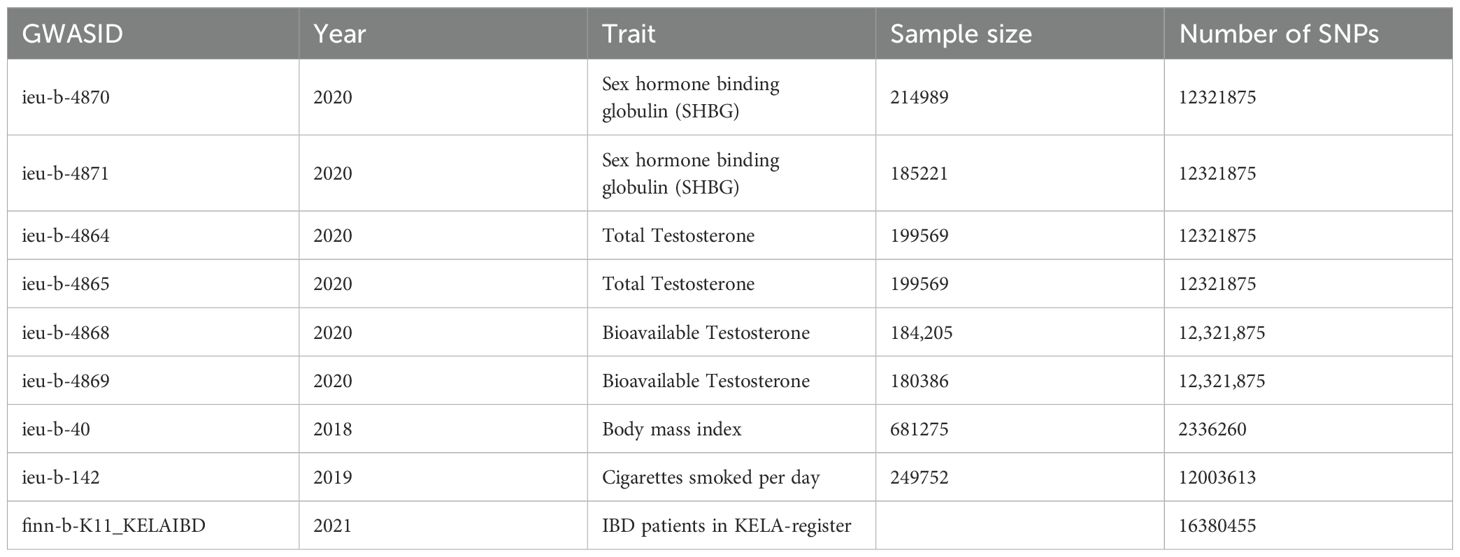

All identified datasets involved in this study are publicly available from the ieu dataset (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets) (13). Ethical approval was obtained for all original studies. The relevant ieu data used are shown in Table 1.

Instrument selection

In order to effectively demonstrate causal effects, instrumental variables (IVs) used in MR analyses must meet three key conditions: (1) they must have a strong association with the exposure, (2) they must not be associated with any confounders, and (3) they must only influence the outcome through the exposure and not through other pathways (14). To select the instrumental variables (IVs), we followed the following criteria: (1) SNPs associated with exposure at the genome-wide motif significance threshold (P < 5 × 10-8) were considered as potential IVs; (2) We used the 1000 Genomes Project European samples data as a reference panel to identify SNPs with low linkage disequilibrium (LD) and R2 < 0.001 (aggregation window size = 10,000 kb), and only the SNPs with the lowest P-value were retained to ensure that each SNP is independent; (3) SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≤ 0.01 were excluded to exclude rare variants; and (4) In cases where palindromic SNPs were present, we inferred the forward stranded alleles using allele frequency information; (5) SNPs associated with confounders (smoking, alcohol consumption, BMI, etc.) were removed using Phenoscanner. In addition, the strength of IVs was assessed using the F statistic (F = beta2/se2) for each SNP, and SNPs with F < 10 were excluded (15) to reduce bias from weak instrumental variables.

Statistical analyses

In this study, we employed multiple methods, including Inverse Variance Weighting (IVW), Simple mode, MR Egger regression, weighted median, and weighted modeling, to investigate the potential causal relationship between sex hormones and IBD. Moreover, we utilized MR-PRESSO analysis to identify and mitigate horizontal pleiotropy by eliminating significant outliers. The heterogeneity of individual SNP effects was assessed using the Cochran Q test (16). Furthermore, to evaluate the causal association between IBD and sex hormones, we conducted a reverse MR analysis, employing the same methods and settings as the forward MR analysis. The estimates are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), which indicate the average change in the outcome resulting from each exposure. These results only provide evidence of a causal effect between the exposure and the outcome, without any other interpretation.

The analyses were primarily conducted using the statistical software R (version 4.1.0). Various packages including TwoSampleMR (version 0.5.6), MendelianRandomization (version 0.6.0), MRPRESSO (version 1.0), and ggplot2 (version: 3.3.5) were utilized for data manipulation, graph creation, and reading.

Results

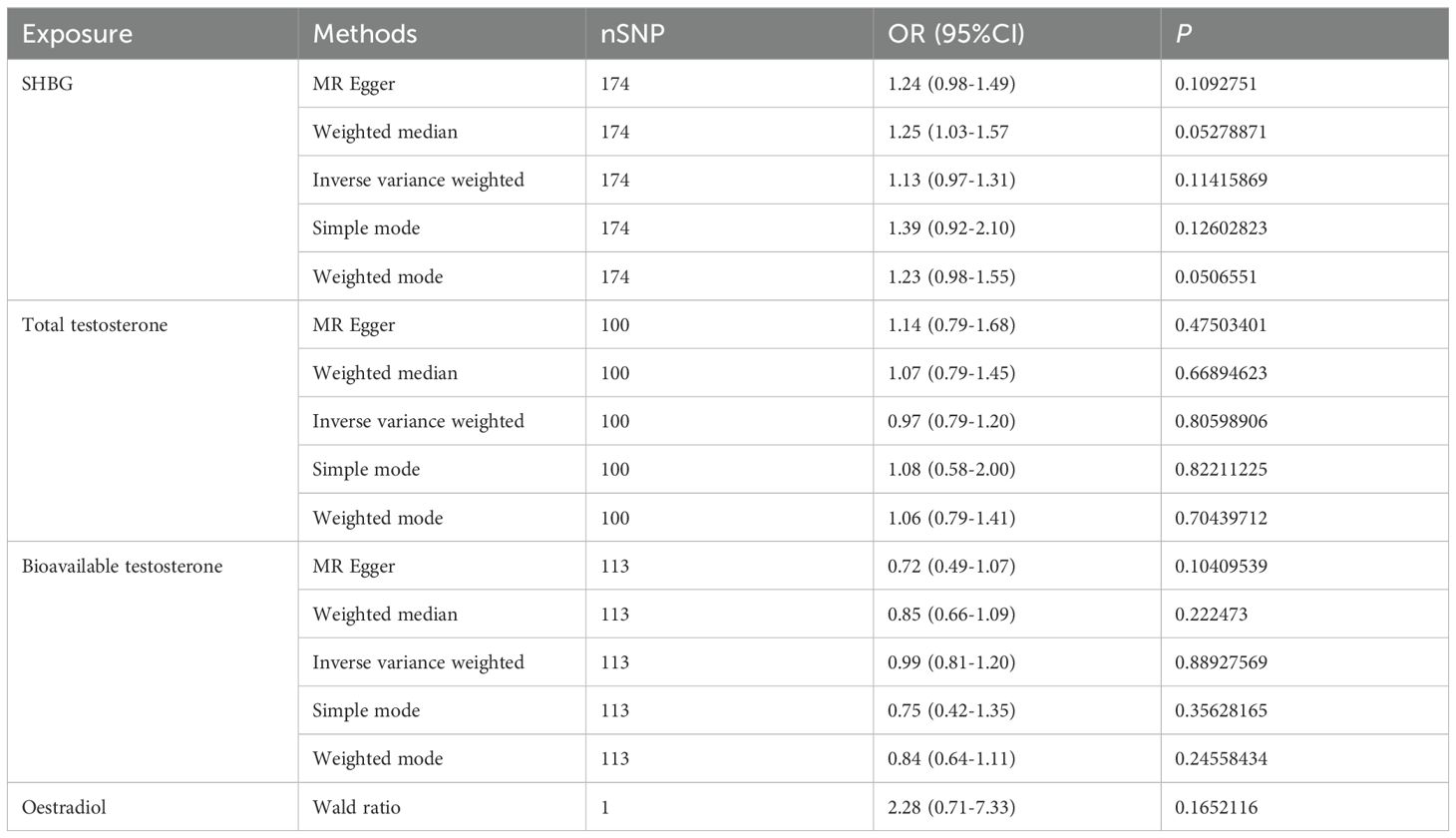

Causal relationship between female sex hormones and IBD

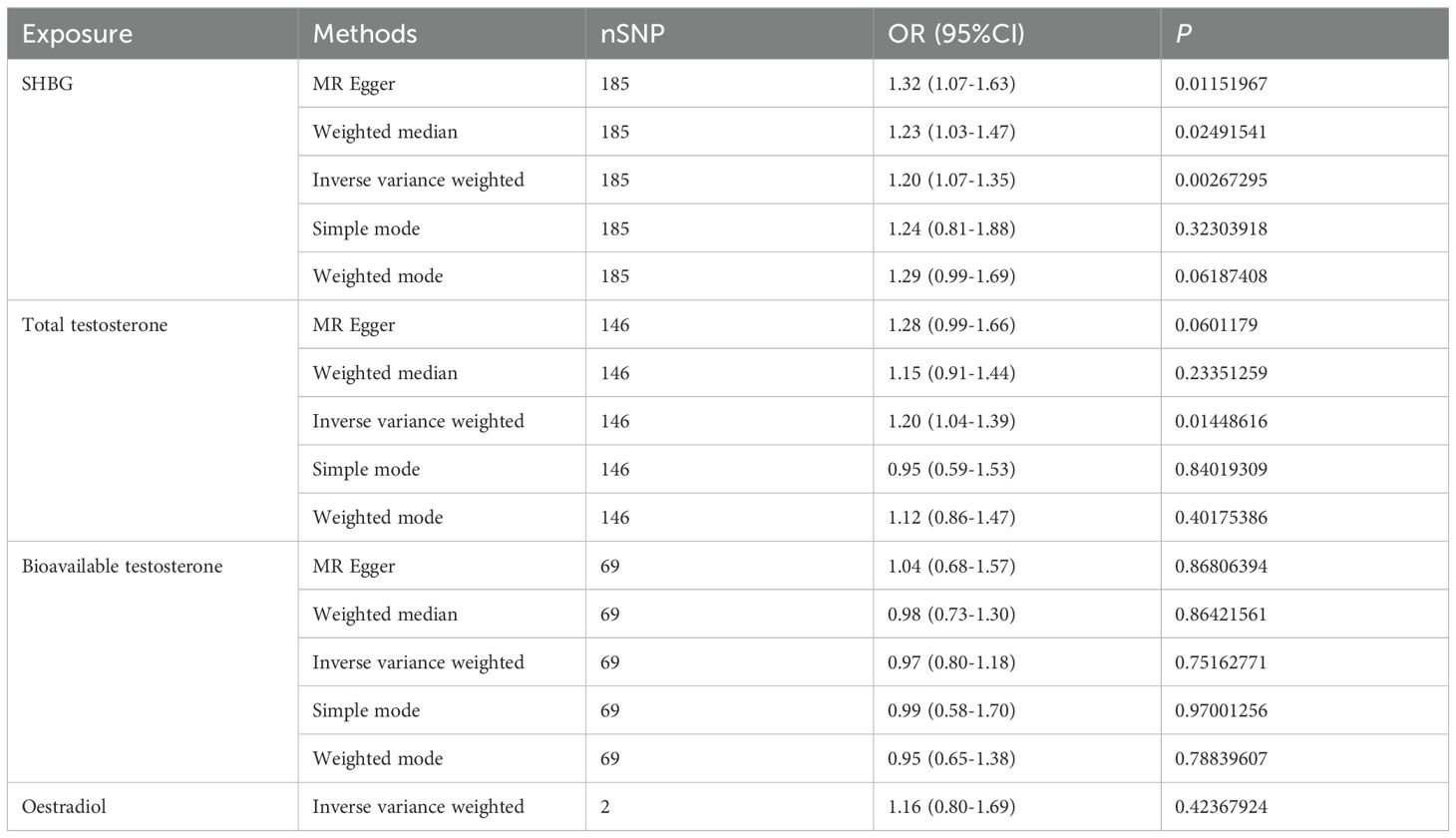

We conducted a Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to investigate the relationship between female sex hormone levels (SHBG, total testosterone, bioavailable testosterone, and estradiol) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). After excluding factors such as horizontal pleiotropy and F>10, we identified a total of 174,100,113 and 1 SNPs for MR analysis, respectively. However, our findings did not reveal any statistically significant effect of SHBG, total testosterone, bioavailable testosterone, or estradiol on IBD in females (Figure 1A, Table 2). Furthermore, the funnel plot shows no bias (Supplementary Figures 1A–C) and removal-by-removal tests demonstrated that no individual SNP significantly influenced the robustness of our results, indicating the stability of our study (Supplementary Figures 1D–F).

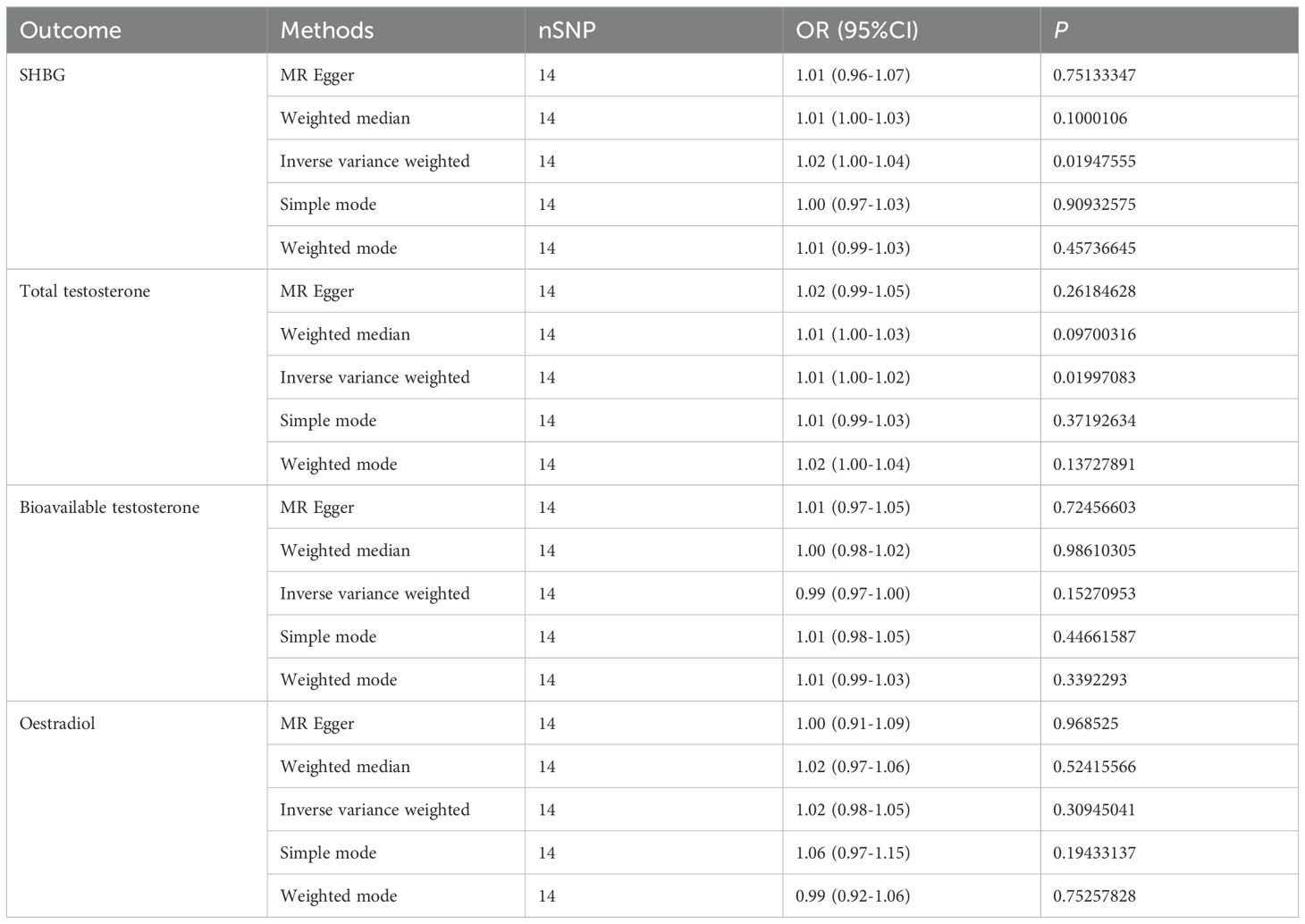

Figure 1. Causal relationship between female sex hormone and IBD. (A) Forest plot of the causal relationship between female sex hormones and IBD via univariate Mendelian randomization. (B) Forest plot of the causal relationship between female sex hormones and IBD by multivariate Mendelian randomization. (C) Forest plot of the causal relationship between IBD and female sex hormones. SHBG, Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin; nSNP, Number of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms; OR (95% CI), Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval); MR Egger, Mendelian Randomization Egger Regression; IVW, Inverse Variance Weighted.

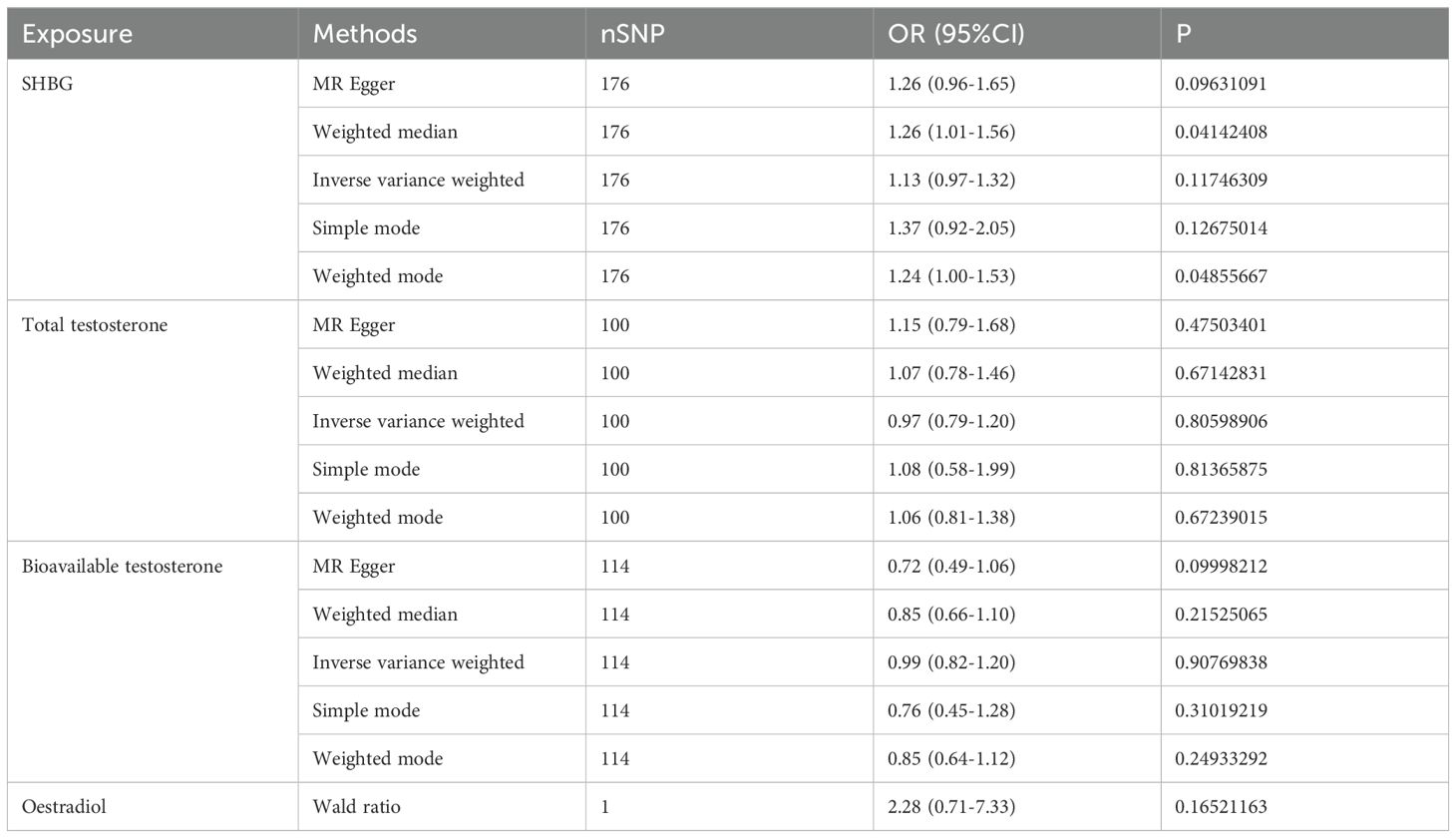

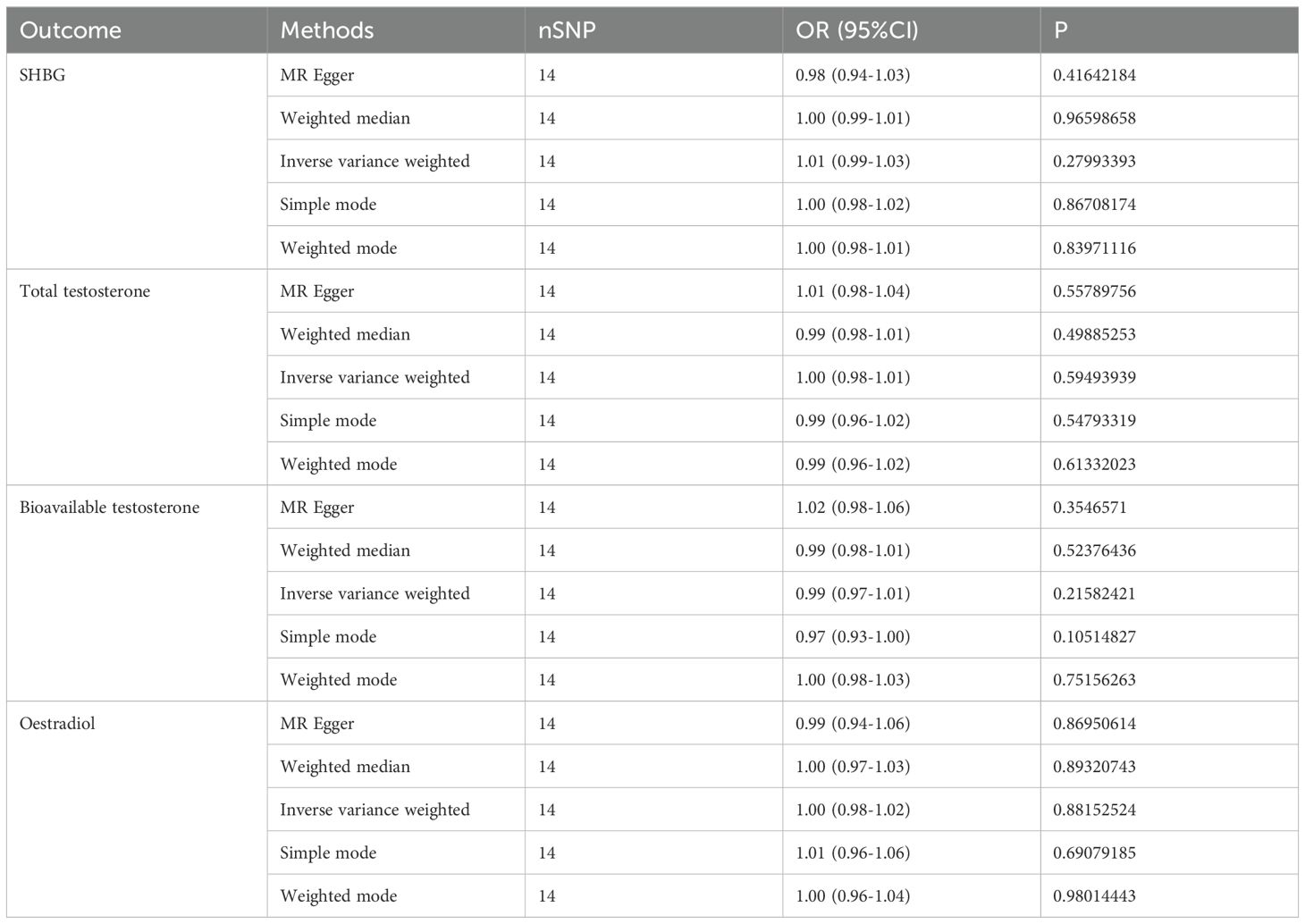

In our study, we investigated the causal relationship between sex hormones and IBD using multivariate Mendelian randomization. After accounting for confounding factors such as other sex hormones, BMI, and smoking, we did not find a statistically significant relationship between sex hormones and IBD in women (Figure 1B, Table 3). Furthermore, we conducted reverse Mendelian randomization to explore the causal association between IBD and female sex hormones, and our results also showed no statistically significant association between IBD and female sex hormones (Figure 1C, Table 4).

Causal relationship between male sex hormones and IBD

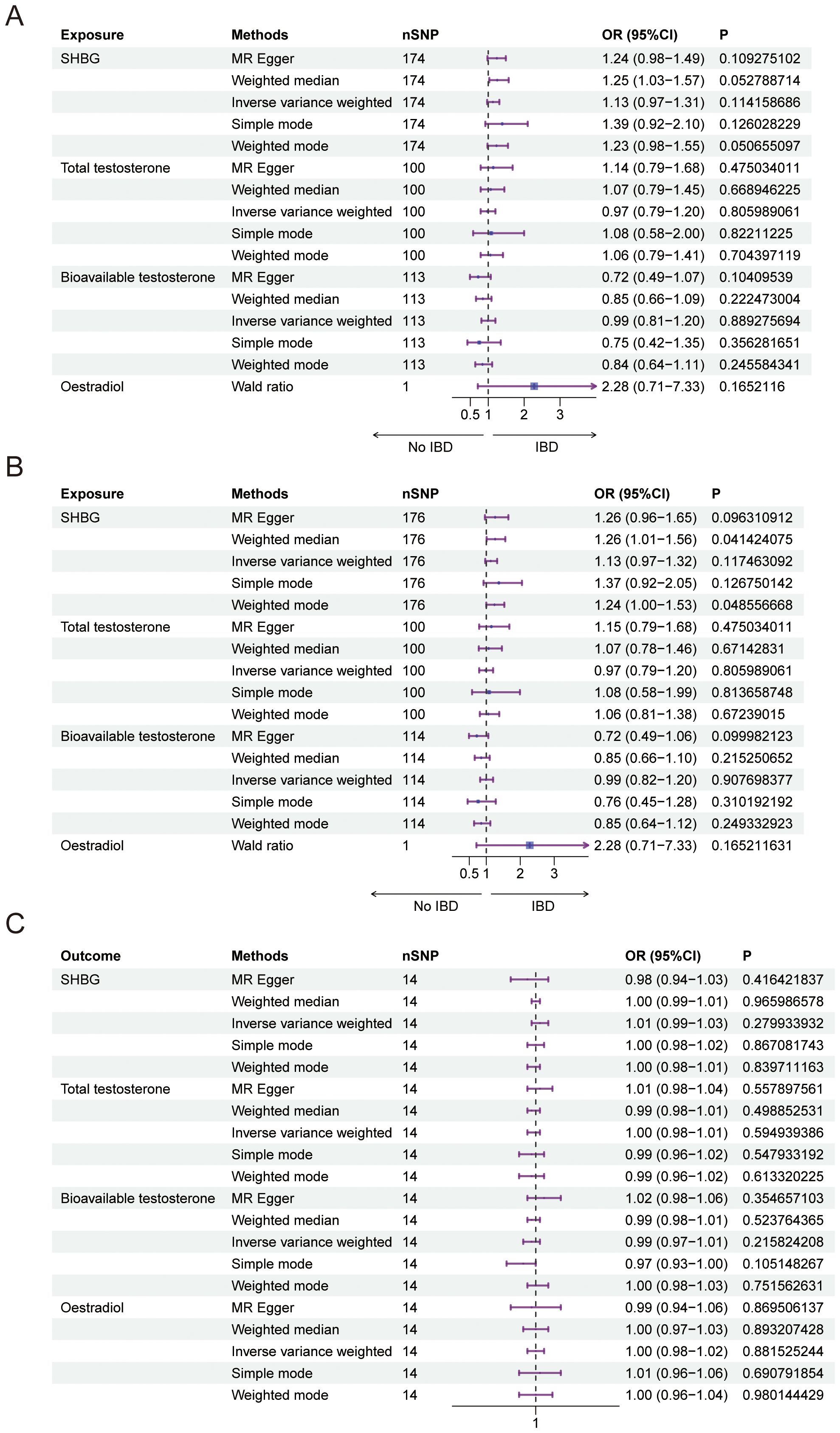

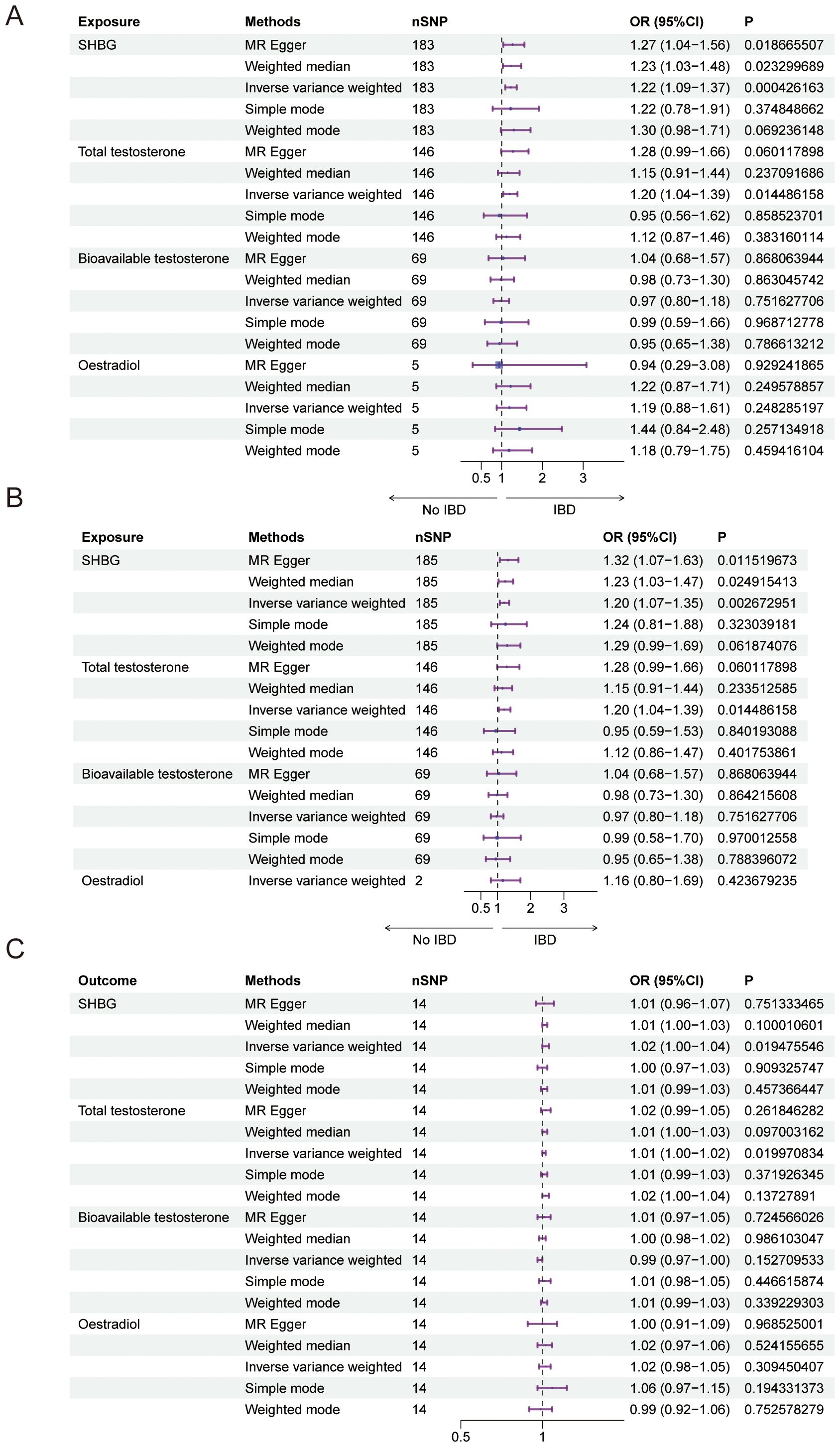

We conducted a Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to examine the relationship between male sex hormone levels (SHBG, total testosterone, bioavailable testosterone, and estradiol) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). We excluded factors such as horizontal pleiotropy and F>10, resulting in a total of 183,146,69 SNPs and 5 SNPs for MR analysis, respectively. Our findings revealed a positive and causal correlation between SHBG and total testosterone with IBD. The odds ratio (OR) for the IVW analysis method was 1.22 (95% CI: 1.09-1.37, P = 0.0004) for SHBG and 1.20 (95% CI: 1.04-1.39, P = 0.0145) for SHBG. However, bioavailable testosterone and estradiol did not show statistical significance (Figure 2A, Table 5). Additionally, the funnel plot shows no bias (Supplementary Figures 2A–C) and the one-by-one method did not identify any single SNP that significantly influenced the results, indicating the stability of our findings (Supplementary Figures 1D–F).

Figure 2. Causal relationship between male sex hormone and IBD. (A) Forest plot of the causal relationship between male sex hormones and IBD via univariate Mendelian randomization. (B) Forest plot of the causal relationship between male sex hormones and IBD by multivariate Mendelian randomization. (C) Forest plot of the causal relationship between IBD and male sex hormones. SHBG, Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin; nSNP, Number of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms; OR (95% CI), Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval); MR Egger, Mendelian Randomization Egger Regression; IVW, Inverse Variance Weighted.

In addition, we also used multivariate Mendelian randomization to explore the causal relationship between sex hormones and IBD. After excluding the effects of other sex hormones, BMI and smoking as confounders, we found that, consistent with the results of the univariate Mendelian randomization, the OR for SHBG in men was 1.20 (95%CI: 1.07-1.35, P = 0.0027), and that the OR for total testosterone in men was 1.20 (95%CI: 1.04-1.39, P = 0.0144), and bioavailable testosterone and estradiol were not statistically significant (Figure 2B, Table 6). We also performed reverse Mendelian randomization to investigate the causal association between IBD and sex hormones and demonstrated a significant association between IBD and SHBG and total testosterone in men, with an OR of 1.02 (95% CI: 1.00-1.04, P=0.0195) for IBD on SHBG in men and an OR of 1.01 (95% CI: 1.00-1.02, P=0.0200), and was not statistically significant for bioavailable testosterone versus estradiol in men (Figure 2C, Table 7).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the bidirectional causal relationship between sex hormones and IBD by Mendelian randomization. We found that there was no causal relationship between sex hormones and IBD in women, whereas SHBG and total testosterone were positively correlated with each other and IBD in men, and the reliability of our conclusions was further demonstrated by sensitivity analysis.

IBD is a chronic disease (17) and it is worth noting that there are sex differences in the risk of developing IBD (18, 19) A previous study found that younger women had a lower incidence of IBD than men, but women over 35 had higher IBD compared to men, so we hypothesized that estrogen may be playing a role (20) There have been studies demonstrating an association between estrogen and IBD, and one mouse experiment demonstrated that estradiol may be involved in the progression of IBD, with her mediating a less severe degree of IBD in female mice and a better ability to recover (21). In addition, other studies have shown that estrogen receptors play an important role in the progression of IBD (22).

Total testosterone refers to the combined concentrations of protein-bound and unbound testosterone in the bloodstream. Available testosterone, on the other hand, represents the portion of circulating testosterone that is not bound to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). SHBG is produced by the liver and has a strong attraction to testosterone, with both substances playing a crucial role in the functioning of living organisms (23). Some studies have demonstrated that SHBG-bound testosterone is distributed differently in men and women (23, 24) A significant association between SHBG and testosterone in gastrointestinal disorders has been observed in various studies. A meta-analysis conducted on the UK Biobank dataset revealed that SHBG and testosterone were found to be linked with an increased risk of colorectal cancer specifically in men, but no statistically significant association was observed in women (25, 26). This is consistent with our finding that SHBG and testosterone are associated with IBD risk only in men. Mechanistically, SHBG can mitigate oxidative stress by modulating the expression of endogenous antioxidant enzymes, including SOD1, CAT, and GPx. This regulation reduces the intracellular accumulation of ROS, ultimately alleviating inflammation (27). Furthermore, evidence suggests that SHBG also influences adipose tissue metabolism, contributing to the suppression of inflammatory responses (28). In addition, testosterone treatment induces an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines which in turn affects the progression of inflammation (29). These findings highlight the significant roles of SHBG and testosterone in the pathogenesis of IBD, particularly in men.

It has been shown that estrogens play a protective role in the gastrointestinal tract (30), with estradiol (E2) being the most biologically active, and that the high binding affinity of SHBG for both estrogens and E2 leads to a decrease in the biological activity of E2 (31). There are several factors that affect SHBG: estrogen can increase SHBG levels; testosterone can decrease SHBG levels. Therefore, we performed multivariate Mendelian randomization to exclude the effects of other estrogens and found that SHBG is elevated for the risk of IBD in men. In addition to this, we performed reverse Mendelian randomization and found that IBD also leads to altered SHBG versus testosterone levels in men. A study showing that IBD affects sex hormone production in boys is consistent with our study (7, 8). Additionally, a cross-sectional study demonstrated that IBD severity significantly impacts sex hormone levels in an East Asian male cohort (32). Correspondingly, data from a Chinese population reveal that testosterone and androstenedione levels are inversely related to inflammatory markers (33). These findings suggest a linkage between sex hormones and IBD that extends beyond European demographics to include various ethnic groups.

The present study used bidirectional two-sample Mendelian analysis to explore the bidirectional causal relationship between sex hormones and IBD has the following advantages: first, it can exclude the bias caused by confounding factors. Second, the huge sample size of GWAS can ensure the correctness of the results.

The study has a few limitations that should be considered. Firstly, the population in this study was limited to individuals of European ancestry, and it is important to acknowledge that there may be genetic differences among different ethnic groups. Secondly, while this study establishes a causal relationship between sex hormones and IBD, it does not provide a detailed explanation of the specific molecular mechanisms involved. Further verification through functional experiments is necessary to gain a deeper understanding of these mechanisms. Although adjustments were made for certain confounders, other unknown factors may still influence IBD. Further research will be required to address these potential limitations in future studies.

In conclusion, we found that SHBG and total testosterone were positively correlated with the risk of IBD in men. In addition, IBD was also positively correlated with SHBG versus total testosterone in men and they may have a mutually reinforcing relationship. In addition, further studies on different populations are needed due to ethnospecificity. Our study indicates that SHBG and total testosterone could serve as potential biomarkers for guiding the management of IBD. These findings propose a basis for their application in tailoring treatment strategies and optimizing patient care in IBD management.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

KW: Writing – original draft. YL: Writing – original draft. ST: Writing – original draft. ZT: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the “Famous Chinese Medicine Successor” Talent Cultivation Program (JCR2023-2) of the Shanghai Seventh People’s Hospital and the Pudong New Area Chinese Medicine Senior Teacher Succession Talent Program (PDZY-2022-0606).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the people who helped us accomplish this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2025.1338701/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Ailsa L Hart DTR. Entering the era of disease modification in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. (2022) 162(5):1367–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.013

2. Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2015) 12:720–7. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150

3. Xu L, Huang G, Cong Y, Yu YB, Li YL. Sex-related differences in inflammatory bowel diseases: the potential role of sex hormones. Inflammatory Bowel Dis. (2022) 28:1766–75. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izac094

4. Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, Chan FKL, Ng SC. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: A systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2012) 27:1266–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07150.x

5. Riis L, Vind I, Politi P, Wolters F, Vermeire S, Tsianos E, et al. Does pregnancy change the disease course? A study in a European cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. (2006) 101(7):1539–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00602.x

6. Sunanda V, Kane DR. Hormonal replacement therapy after menopause is protective of disease activity in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. (2008) 103(5):1193–6.

7. Mason A, Wong SC, McGrogan P, Ahmed SF. Effect of testosterone therapy for delayed growth and puberty in boys with inflammatory bowel disease. Horm Res Paediatr. (2011) 75(1):8–13. doi: 10.1159/000315902

8. Ballinger AB, Savage MO, Sanderson IR. Delayed puberty associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatr Res. (2003) 34(21):2926–40. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000047510.65483.C9

9. Sullivan O, Sie C, Ng KM, Cotton SC, Rosete CR, Hamden JE, et al. Early-life gut inflammation drives sex-dependent shifts in the microbiome-endocrine-brain axis. Brain Behavior Immun. (2025) 125:117–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.12.003

10. Klaus J, Reinshagen M, Adler G, Boehm B, von Tirpitz C. Bones and Crohn’s: Estradiol deficiency in men with Crohn’s disease is not associated with reduced bone mineral density. BMC Gastroenterol. (2008) 8:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-48

11. Chen J, Xu F, Ruan X, Sun J, Zhang YZ, Zhang HZ, et al. Therapeutic targets for inflammatory bowel disease: proteome-wide Mendelian randomization and colocalization analyses. eBioMedicine. (2023) 89:104494. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104494

12. Sekula P, Del Greco MF, Pattaro C, Köttgen A. Mendelian randomization as an approach to assess causality using observational data. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2016) 27:3253–65. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010098

13. Long Y, Tang L, Zhou Y, Zhao S, Zhu H. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and cancers: a two-sample Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med. (2023) 21(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-02761-6

14. Wang Z, Li S, Tan D, Abudourexiti W, Yu Z, Zhang T, et al. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and periodontitis: A bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J Clin Periodontology. (2023) 50:736–43. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13782

15. Li P, Wang H, Guo L, Gou X, Chen G, Lin D, et al. Association between gut microbiota and preeclampsia-eclampsia: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med. (2022) 20(1).:443. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02657-x

16. Greco M FD, Minelli C, Sheehan NA, Thompson JR. Detecting pleiotropy in Mendelian randomisation studies with summary data and a continuous outcome. Stat Med. (2015). doi: 10.1002/sim.v34.21

17. Barberio B, Massimi D, Cazzagon N, Zingone F, Ford AC, Savarino EV. Prevalence of primary sclerosing cholangitis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. (2021) 161:1865–77. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.032

18. Greuter T, Manser C, Pittet V, Vavricka SR, Biedermann L. Gender differences in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. (2020) 101:98–104. doi: 10.1159/000504701

19. Annese V. IBD. and Malignancies: The gender matters. Digestive Liver Dis. (2020) 52:156–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2019.10.006

20. Shah SC, Khalili H, Gower-Rousseau C, Olen O, Benchimol EI, Lynge E, et al. Sex-based differences in incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases—Pooled analysis of population-based studies from western countries. Gastroenterology. (2018) 155:1079–1089.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.043

21. Bábíčková J, Tóthová Ľ, Lengyelová E, Bartoňová AB, Hodosy JH, Gardlík R, et al. Sex differences in experimentally induced colitis in mice: a role for estrogens. Inflammation. (2015) 38:1996–2006. doi: 10.1007/s10753-015-0180-7

22. Jacenik D, Cygankiewicz AI, Mokrowiecka A, Małecka-Panas E, Fichna J, Krajewska WM. Sex- and age-related estrogen signaling alteration in inflammatory bowel diseases: modulatory role of estrogen receptors. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20(13):3175. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133175

23. Goldman AL, Bhasin S, Wu FCW, Krishna M, Matsumoto AM, Jasuja R. A reappraisal of testosterone’s binding in circulation: physiological and clinical implications. Endocrine Rev. (2017) 38:302–24. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00025

24. Dunn JF, Nisula BC, Rodbard D. Transport of steroid hormones binding of 21 endogenous steroids to both testosterone-binding globulin and corticosteroid-binding globulin in human plasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1981) 53(1):58–68. doi: 10.1210/jcem-53-1-58

25. Liu Z, Zhang Y, Lagergren J, Li S, Li J, Zhou Z, et al. Circulating sex hormone levels and risk of gastrointestinal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. (2023) 32:936–46. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-23-0039

26. McMenamin ÚC, Liu P, Kunzmann AT, Cook MB, Coleman HG, Johnston BT, et al. Circulating sex hormones are associated with gastric and colorectal cancers but not esophageal adenocarcinoma in the UK biobank. Am J Gastroenterol. (2021) 116:522–9. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001045

27. Bourebaba N, Sikora M, Qasem B, Bourebaba L, Marycz K. Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) mitigates ER stress and improves viability and insulin sensitivity in adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASC) of equine metabolic syndrome (EMS)-affected horses. Cell Communication Signaling. (2023) 21(1):230. doi: 10.1186/s12964-023-01254-6

28. Bourebaba L, Kępska M, Qasem B, Zyzak M, Łyczko J, Klemens M, et al. Sex hormone-binding globulin improves lipid metabolism and reduces inflammation in subcutaneous adipose tissue of metabolic syndrome-affected horses. Front Mol Biosci. (2023) 10. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2023.1214961

29. Iannantuoni F, Salazar JD, Martinez de Marañon A, Bañuls C, López-Domènech S, Rocha M. Testosterone administration increases leukocyte-endothelium interactions and inflammation in transgender men. Fertility Sterility. (2021) 115:483–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.08.002

30. Nie X, Xie R, Tuo B. Effects of estrogen on the gastrointestinal tract. Digestive Dis Sci. (2018) 63:583–96. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-4939-1

31. Zhu H, Sun Y, Guo S, Zhou Q, Jiang Y, Shen Y, et al. Causal relationship between sex hormone-binding globulin and major depression: A Mendelian randomization study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (2023) 148:426–36. doi: 10.1111/acps.v148.5

32. Darmadi D, Pakpahan C, Singh R, Saharan A, Pasaribu WS, Hermansyah H, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis type) severity shows inverse correlation with semen parameters and testosterone levels. Asian J Andrology. (2024) 26:155–9. doi: 10.4103/aja202353

Keywords: sex hormone, IBD, Mendelian randomization, genome-wide association, biomarker

Citation: Wang K, Lou Y, Tian S and Tao Z (2025) Causal relationship between inflammatory bowel disease and sex: a Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 16:1338701. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1338701

Received: 08 December 2023; Accepted: 06 January 2025;

Published: 29 January 2025.

Edited by:

Changzheng Chen, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Jose Luis Fachi, Washington University in St. Louis, United StatesBarada Mohanty, University of Saskatchewan, Canada

Copyright © 2025 Wang, Lou, Tian and Tao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhihui Tao, ZGFvbW9ndXlhbkAxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Kaiwen Wang1†

Kaiwen Wang1† Zhihui Tao

Zhihui Tao