- 1Taiwan United Birth-Promoting Experts Fertility Clinic, Tainan, Taiwan

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

Objectives: This study aimed to investigate the correlation of ovarian sensitivity index (OSI) and clinical parameters in IVF treatments.

Methods: IVF data files between January 2011 and December 2020 in a single unit were included. The primary outcome measure was the correlation between the OSI and clinical pregnancy and live birth rates. A generalized linear model was employed to assess group differences while controlling for age. Correlations between the OSI and clinical parameters were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation test.

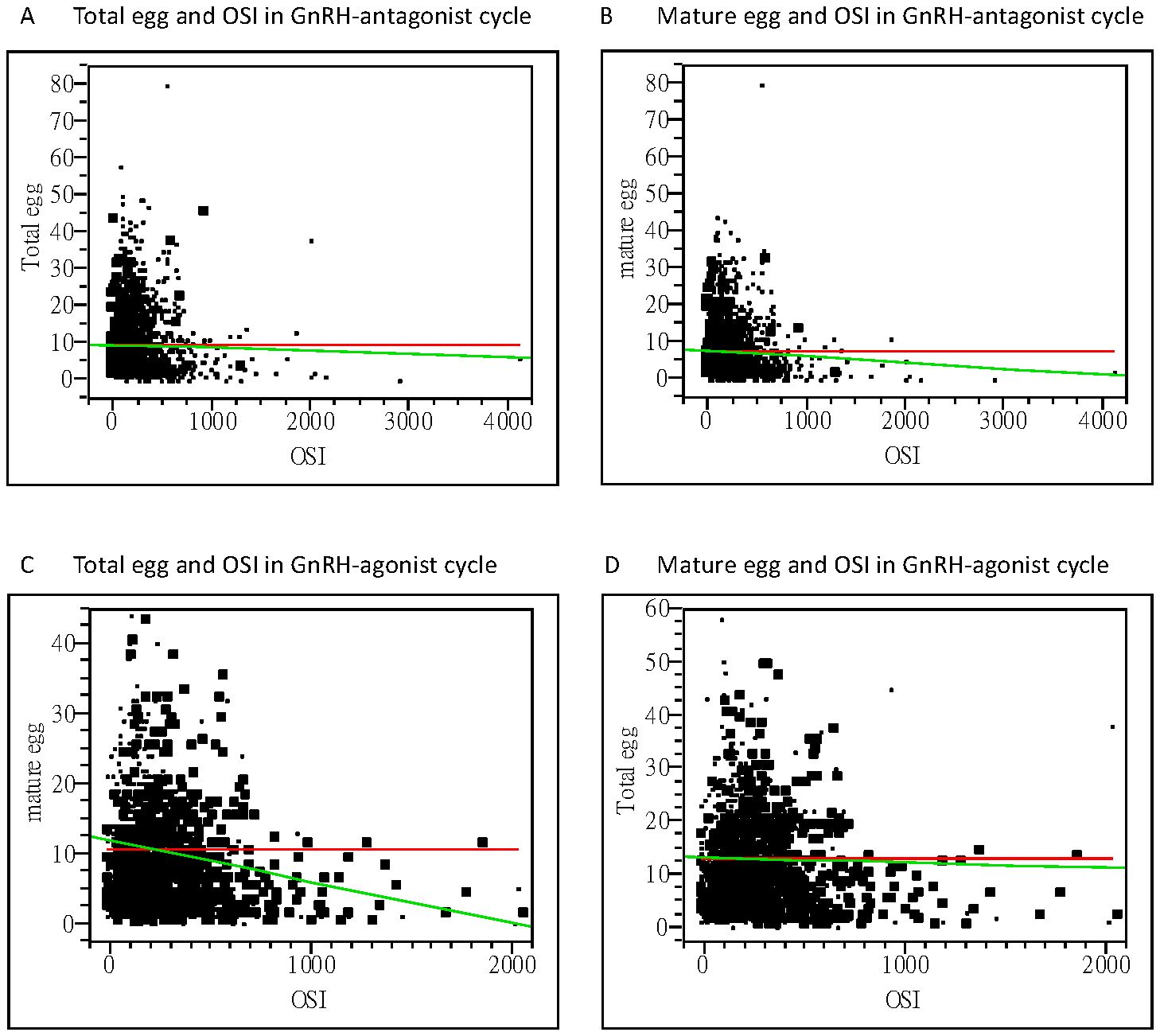

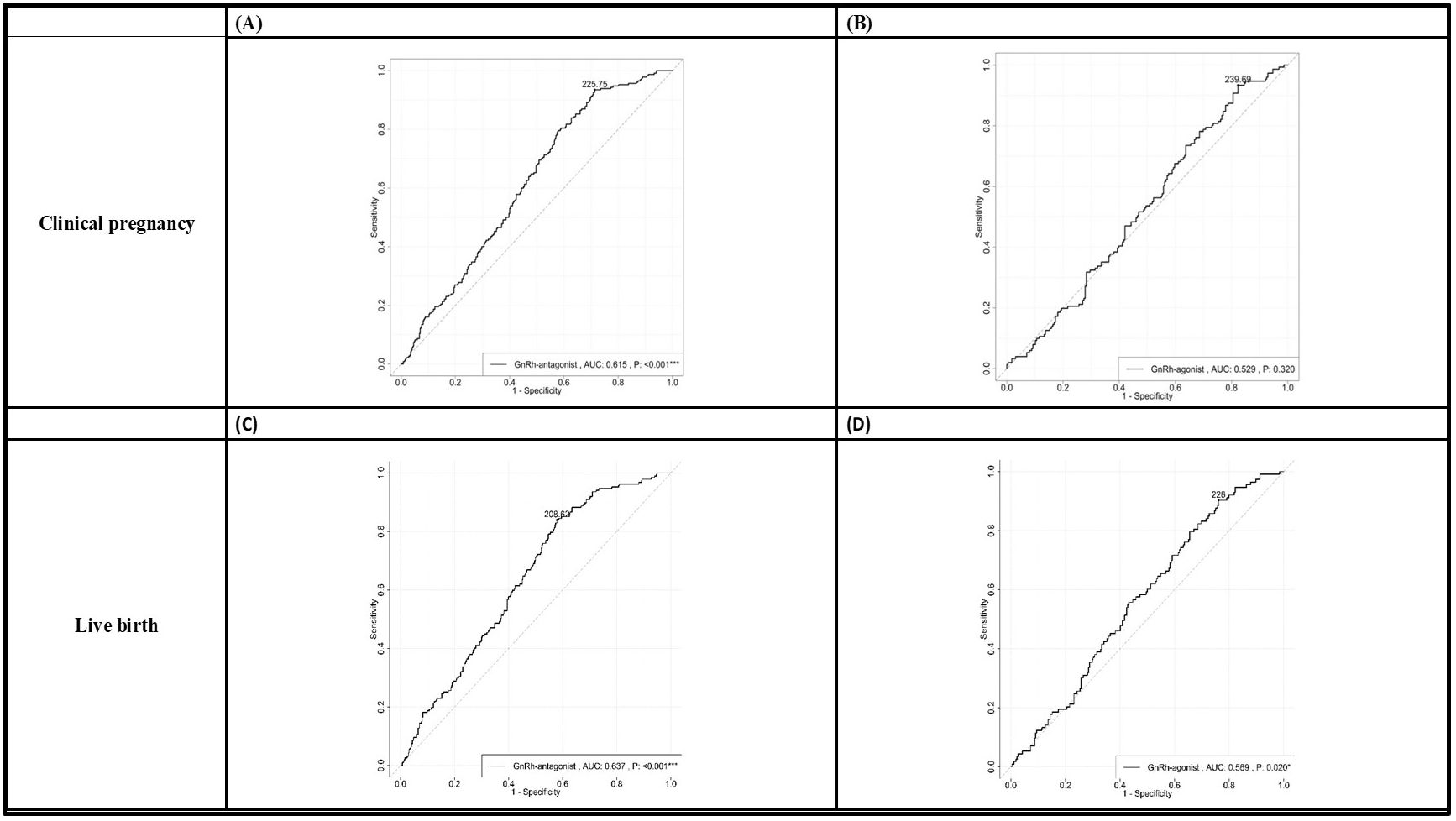

Results: In total, 1,627 patient data were reviewed, comprising 1,160 patients who received GnRH antagonists and 467 who received GnRH agonists. There was no difference in the incidence of premature ovulation and LH surge in women receiving either GnRH antagonists or agonists. A higher number of mature oocytes and good embryos were obtained in the GnRH agonist cycles. No differences were observed in pregnancy and live birth rates between both groups. Regarding the correlation of the OSI with clinical parameters, serum anti-Müllerian hormone, cycle day 2 follicle-stimulating hormone, LH, and estradiol concentrations, numbers of larger follicles, fertilization rate, and the incidence of premature LH surge were positively correlated with the OSI. Whereas the body mass index, mature oocytes obtained, embryo transfer number, and dose of GnRH antagonists were negatively correlated with the OSI. In the GnRH antagonists group, an OSI of 225.75 significantly distinguished pregnancy from non-pregnancy (p < 0.001), with an AUC of 0.615, and an OSI of 208.62 significantly distinguished live births from non-live births (p < 0.001), with an AUC of 0.637. As for the GnRH agonist group, an OSI of 228 significantly distinguished live births from non-live births, (p =0.020) with an AUC of 0.569.

Conclusion: We demonstrated the capability of employing OSI to distinguish the clinical pregnancy and live birth outcomes in IVF cycles.

1 Introduction

The efficiency of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH), which directly affects the outcomes of treatments, including clinical pregnancy and live birth rates, is a major objective for assisted reproduction. Currently, personalized treatment based on an individual’s response to exogenous gonadotropin (Gn) is the main focus in clinical practice. The goal of COH is not only to obtain enough oocytes to achieve better clinical outcomes but also to prevent the incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and manage poor ovarian response, particularly in many older women (1–3). Traditionally, women’s age, serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) levels, and antral follicle count (AFC) have been used for this purpose, and the starting dose of Gn in the COH cycle has been estimated (4, 5). Employing different doses of Gns for each patient is the most important clinical practice in individualized therapy (6).

The dynamic ovarian response to COH has attracted considerable attention in recent years. Different dynamic aspects of the ovarian response that correlate follicular growth to Gn have been studied, for example, ovarian sensitivity index (OSI, the dose of Gn used divided by the number of mature oocytes obtained) (7) and follicular output rate (FORT, the ratio of pre-ovulatory follicle count (14–22 mm in diameter) on human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) day × 100/small antral follicle count (3–8 mm in diameter) at baseline (8), and the follicle-to-oocyte index (FOI, the ratio between the number of oocytes obtained and number of antral follicles at the beginning of COS) (9). The study and application of dynamic ovarian responses to COH are based on the premise that ovarian responses rely on multiple parameters. Few studies have attempted to integrate the dynamic ovarian response to different clinical parameters with the advantages of employing Gn-releasing hormone-agonist (GnRH-a) and/or GnRH-antagonists (GnRH-antag) in COH (10, 11). In this study, we investigated the correlation between OSI and multiple clinical parameters in GnRH-a and GnRH-antag cycles. The relationship between OSI and clinical outcomes of in vitro fertilization (IVF), especially clinical pregnancy and live birth rates, was determined.

2 Methods

2.1 Study population and design

This retrospective study analyzed the assisted reproduction files of all women in our IVF unit between January 2011 and December 2020. Data from those using the natural cycle or GnRH agonist ultra-long protocol, frozen embryo replacements, preimplantation genetic screening, or preimplantation genetic diagnosis were excluded. Only data from the first IVF treatment were included if the patients consecutively received several cycles of IVF in our unit.

2.2 Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (TSMH IRB/Protocol No: 18-115-B). All assisted reproductive processes were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. All patients included in the study were treated at the IVF unit at the TUBE Fertility Clinic, Tainan, Taiwan, under a license from the Taiwan Department of Health Authority. Written consent was obtained from each patient to receive different administration modes of COH. All women receiving IVF treatments were informed about the benefits, risks, and potential adverse reactions of the entire procedure, including the different administration modes of COH (Gn, GnRH-a, and GnRH-antag). Possible risks of OHSS, allergic reactions, and local transitory effects, such as ecchymosis, itching, discomfort, and irritation were explained.

2.3 Controlled ovarian stimulation

The administration of GnRH-a, GnRH-antag, and Gn followed established protocols (12, 13). For the GnRH-a protocol: starting from day 3 of the preceding menstrual cycle, oral contraceptive pills (Marvelon, containing 0.03 mg ethinyl estradiol and 0.15 mg desogestrel, NV Organon, Oss, The Netherlands) were used. From day 18, a GnRH-a nasal spray (200 mg buserelin acetate, Aventis Pharma Deutschland GMBH, Frankfurt, Germany) was administered three times daily to achieve pituitary suppression. The GnRH agonist was maintained throughout the COH until the onset of hCG triggering. Gonadotropin (Gonal-f Prefilled Pen 300 IU rhFSH in 0.5 mL, Merck Serono S.p.A., Modugno, Italy) in combination with menopur (300 IU Menopur 75 IU, corresponding to 75 IU of FSH and luteinizing hormone (LH) 75 IU; Ferring GmBH, Kiel, Germany) was initiated on day 2 of the IVF cycle once pituitary suppression was achieved as manifested by serum estradiol (E2) <50 pg/mL, LH <2.5 mIU/mL, and FSH <10 mIU/mL. Intermittent injections of Gn on cycle days 2, 5, and 8 were performed in accordance with our previously established method (13). In brief, Gonal-f 300 IU in combination with 300 IU menopur was initiated on day 2 of the IVF cycle. Follow-up of ovarian follicular growth by ultrasound scanning was mostly performed on days 5 and 8–11. On days 5 and 8, if follicular growth did not meet the criteria (≥2 follicles ≥17 mm) for egg retrieval, a second and third dose of Gn injection were administered. The dosage for the second and third dose of Gn injection was based on the number and size of the follicles detected: 450 IU Gn if ≥2 follicles were >12 mm, and 600 IU Gn if most follicles were ≤12 mm.

For the GnRH-antag protocol, the third-generation GnRH antag ganirelix (orgalutron 0.25 mg, NV Organon, Oss, The Netherlands) was initiated once the ovarian follicle reached 12 mm in size on day 5 or 8 of the COH cycle. The GnRH-a was maintained throughout the COS until the day of hCG triggering. The mode of Gn administration in the GnRH-antag cycle was similar to that described for the GnRH-a cycle protocol.

Thus, two groups of patients were identified: group A received GnRH-a, and group B received GnRH-antag injections to suppress the premature LH surge. Follicular growth was detected using two-dimensional ultrasound scanning (Aloka 900, Tokyo, Japan) and performed by the same observer (C.C. Hsu) using a 5.0-MHz transvaginal transducer. The follicle diameter was calculated as the mean diameter measured in two dimensions. Serum levels of FSH, LH, progesterone (P4), and E2 on day 2 of the menstrual cycle and the day of hCG were assessed.

2.4 Oocyte retrieval and clinical outcomes

Oocytes were retrieved in accordance with our previously established method (13, 14). In brief, oocyte retrieval took place 36 h after triggering the final follicular maturation using 2 mg GnRH-a (Leuprolide acetate, FAMAR L’AIGLE, Saint Remy Sur Avre, France) in combination with 6,000 IU hCG (Ovidriel, Merck Serono) when two or more follicles reached ≥17 mm in diameter. Mature oocytes were fertilized in vitro or by intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Fertilized pre-embryos were cultured to day 3 cleavage-stage embryos or day 5–6 blastocyst stage for embryo transfer. The number of embryos transferred was based on the age of the women: one embryo for ≤35 years old, two embryos for 35–40 years old, or three embryos for ≥40 years old. Additional embryos were cryopreserved at day 3 of cleavage stage or at the blastocyst stage. Micronized P4 (utrogesterone; Besins Healthcare, Ayutthaya, Thailand) 100 mg three times daily was used for luteal support from the day after oocyte retrieval for 15 days until pregnancy was confirmed by serum hCG determination. Clinical pregnancy was confirmed using ultrasound at 4 weeks after embryo transfer. The safety endpoints included the proportion of women with moderate/severe-grade OHSS and preventive interventions for early OHSS (i.e., cycle cancellation due to excessive ovarian response). Adverse events, such as pain or skin reactions, were also recorded during Gn and GnRH-a/GnRH-antag injections.

2.5 Study outcome measures

The primary outcome was the correlation between the OSI and clinical parameters, including clinical pregnancy and live birth rates during fresh embryo transfer cycles. The secondary outcomes included mature oocytes retrieved and the incidence of premature ovulation.

2.6 Measurement of serum hormone levels

The Beckman Coulter ACCESS immunoassay system was used in the hormone assay (UniCelDxl 800, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, RRID: FSH: AB_2750983, LH: AB_2750984, AMH: AB_2892998, estradiol:AB_2892997, progesterone:AB_2756883). However, FSH and LH were measured using a sequential two-step immunoenzymatic “sandwich” assay. The lowest detectable level was 0.2 IU/L, and the assay exhibited a total imprecision of ≤10% for both FSH and LH. AMH levels were measured in serum samples using a simultaneous 1-step immunoenzymatic “sandwich” assay. The assay has a limit of detection at ≤0.02 ng/mL, with total imprecision ≤10.0% at concentrations of ≥0.16 ng/mL. A competitive binding immunoenzymatic assay was used to measure serum E2 and P4 levels. The lowest detectable level of E2 was 20 pg/mL, and that of P4 was 0.10 ng/mL.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and comparisons between groups of women were conducted using the Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, with the chi-square test applied to analyze their distributions. A generalized linear model (GLM) was employed to assess group differences while controlling for age and to evaluate the relationships between categorical and continuous variables. Correlations between the OSI and clinical parameters were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation test. Partial correlation analysis, adjusted for age, was also performed. Additionally, receiver operation characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to distinguish clinical pregnancy and live birth outcomes between the GnRH-a and GnRH-antag groups, utilizing the pROC package in R. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Statistics version 22.0 and various R packages in R Studio.

3 Results

3.1 Participant demographics

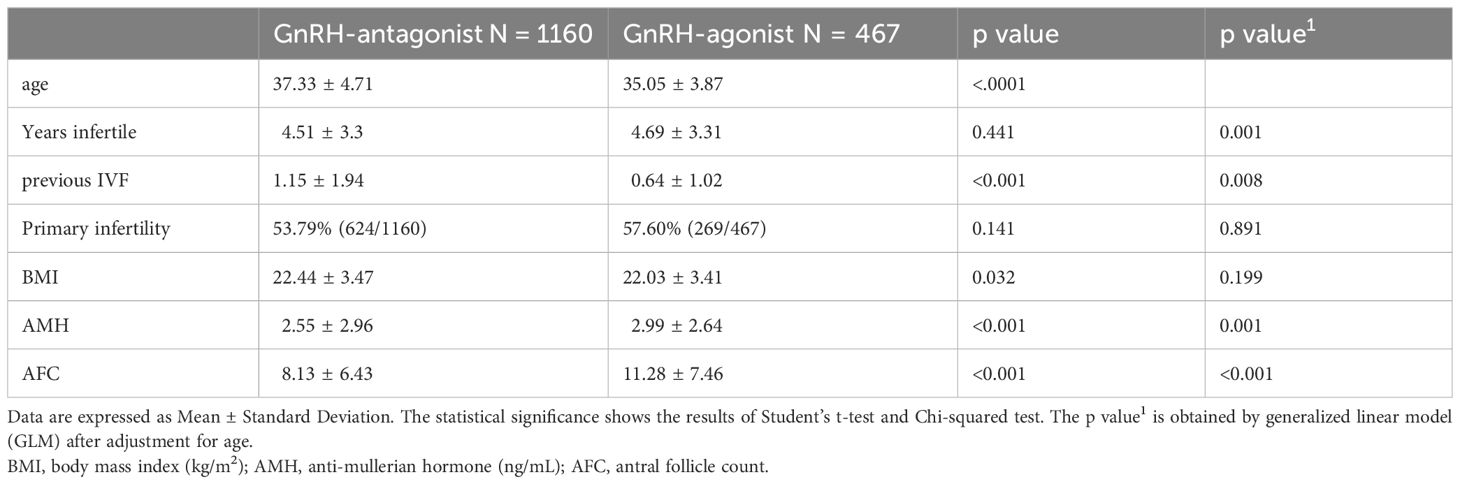

From the data of 3,012 cases, 1,385 were excluded: 764 due to frozen embryo replacement cycles; 534, repeated treatment cycles; and 87, other exclusion factors. In total, 1627 patient data files were analyzed, of which 1,160 patients received GnRH-antag and 467 received GnRH-a IVF cycles. The demographic patterns of the infertile women are presented in Table 1. The average age of the study population was 36.68 ± 4.60 years, with a body mass index (BMI) of 22.32 ± 3.46 kg/m2. The average serum AMH was 2.67 ± 2.88 ng/mL, with AFC of 9.01 ± 6.89. Younger age and better AMH and AFC parameters were noted in GnRH-a group (Table 1). The cycle day 2 serum hormones FSH, E2, and LH were higher in those received GnRH-antag (Table 2).

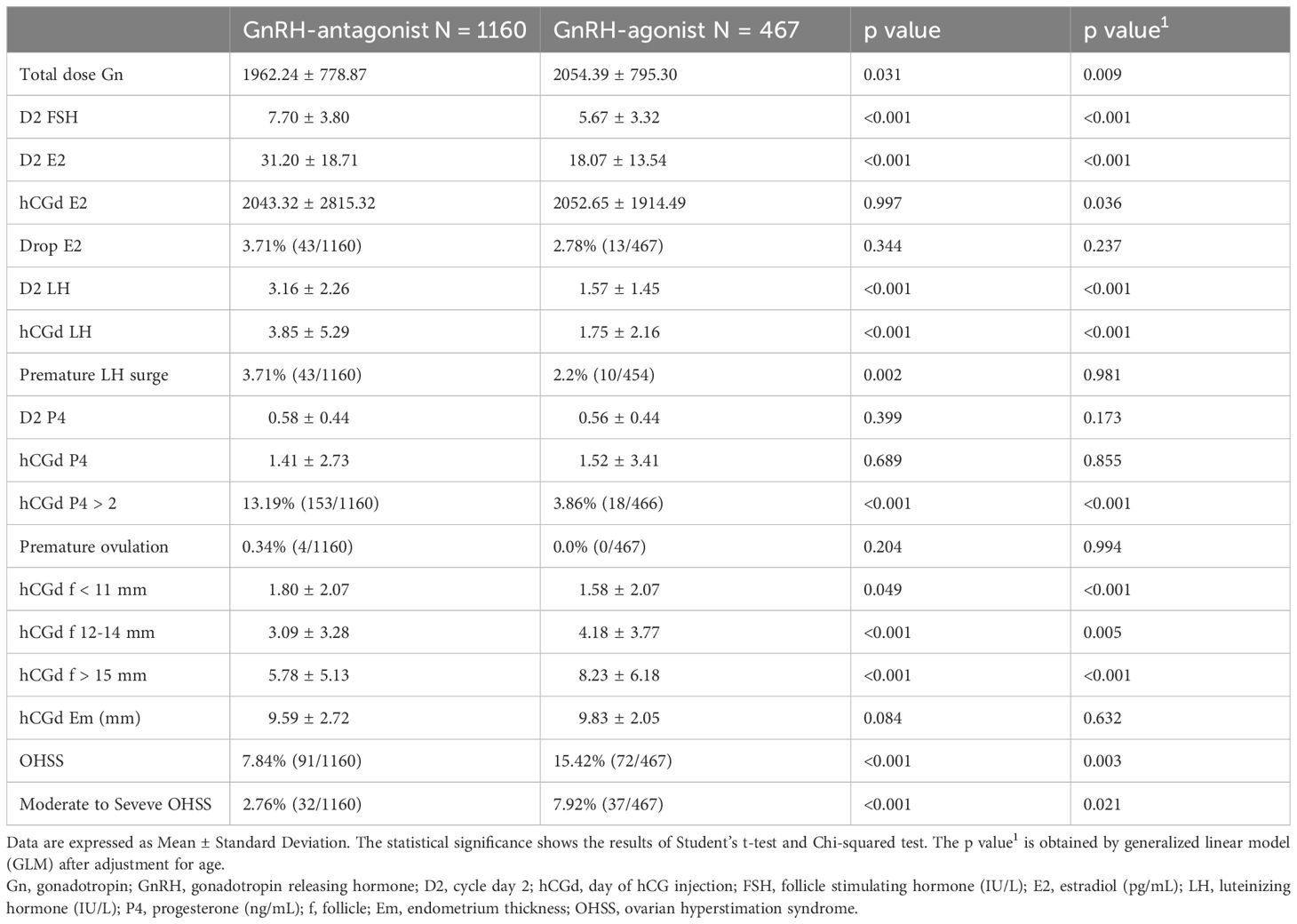

3.2 Clinical response after COH using GnRH-antag or GnRH-a cycles

Elevated serum concentrations of LH, >2.5 times the baseline level and surpassing 17 IU/L, were not different between the two groups of women. Serum E2 levels on the day of hCG triggering were 2043.32 ± 2815.32 and 2052.65 ± 1914.49 pg/mL in women who received GnRH-antag and GnRH-a, respectively, with a significant difference (p = 0.036). Premature luteinization (P4 >2 ng/mL) was noted in 13.19% (153/1160) and 3.86% (18/466) of women who received GnRH-antag and GnRH-a, respectively (p <0. 001). However, the incidence of premature ovulation, indicated by the disappearance of growing follicles before oocyte retrieval, did not differ between the two groups. The number of medium-to-large-sized follicles (12–14 mm and >15 mm) and the incidence of OHSS were higher in women who received GnRH-a (Table 2).

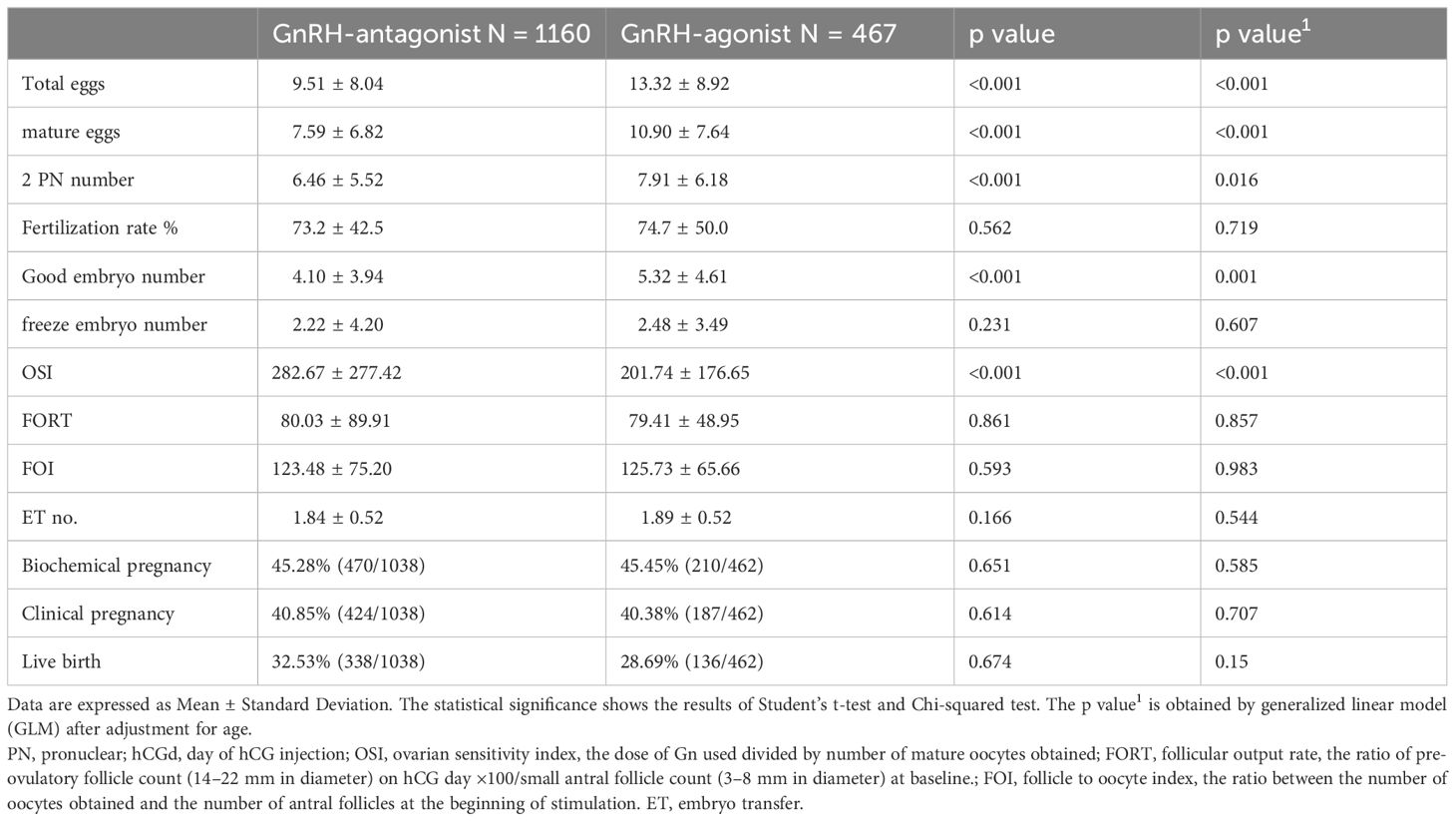

3.3 Embryology and clinical outcomes in GnRH-antag or GnRH-a cycles

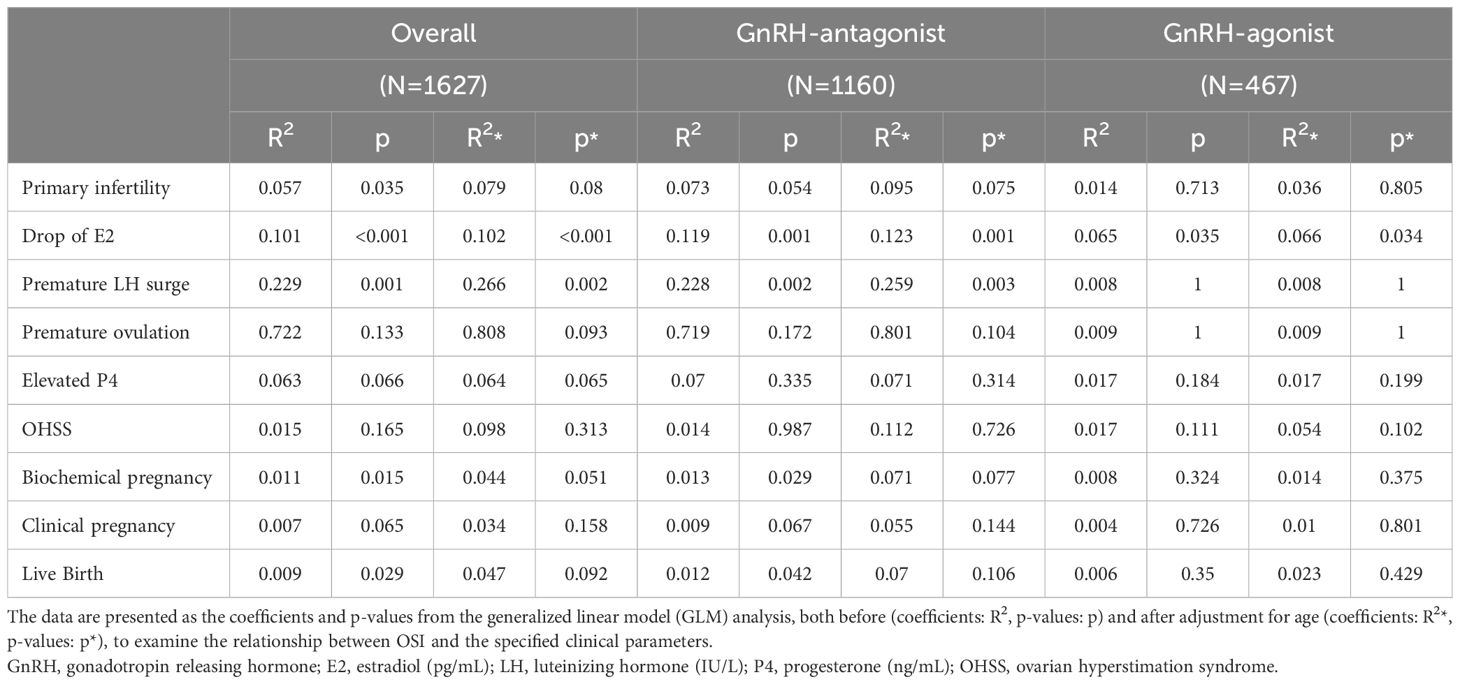

In the embryo laboratory, higher total oocyte numbers, mature oocytes, two pronuclear pre-embryos, and good embryo numbers were obtained following GnRH-a treatment cycles. Linear regression analysis of receiver operating characteristics indicated that higher numbers of oocytes were obtained from younger women, especially in the GnRH-a group (area under curve = 0.63), in comparison to area under curve = 0.52 in the GnRH-antag group. However, in both GnRH-a and GnRH-antag cycles, age was significantly correlated with total oocytes and mature oocytes (p <0.0001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bivariate fit of oocytes retrieved and women’s age. (A) A significant correlation between the total oocytes obtained and age is noted with a correlation coefficient of −0.65 using linear regression analysis (p <0.0001) in the GnRH antagonist cycle. (B) A significant correlation between the mature oocytes obtained and age is noted, with a correlation coefficient of −0.56 using linear regression analysis (p <0.0001) in the GnRH antagonist cycle. (C) A significant correlation between the total oocytes obtained and age is noted, with a correlation coefficient of−0.54 using linear regression analysis (p <0.0001) in the GnRH-agonist cycle. (D) A significant correlation between the mature oocytes obtained and their age was noted, with a correlation coefficient of −0.42 using linear regression analysis (p <0.0001) in the GnRH-agonist cycle. GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

Higher OSI of 282.67 ± 277.42 was noted in GnRH-antag treatment cycles in comparison to 201.74 ± 176.65 in GnRH-a treatment cycles (p <0.0001), indicating that higher Gns is required to stimulate one mature oocyte in GnRH-antag cycles. No difference was noted based on the FORT and FOI indices between the two groups (Table 3). Thus, OSI is very useful as a predictive value than FORT and FOI and was used as the ovarian response factor for further analysis with other clinical parameters.

A total of 680 women conceived following fresh embryo transfer, with a clinical pregnancy rate of 40.85% and 40.38%, and a live birth rate of 32.53% and 28.69% in the GnRH-antag and GnRH-a cycles, respectively (Table 3). No differences were noted in clinical pregnancy and live birth rates between the two groups.

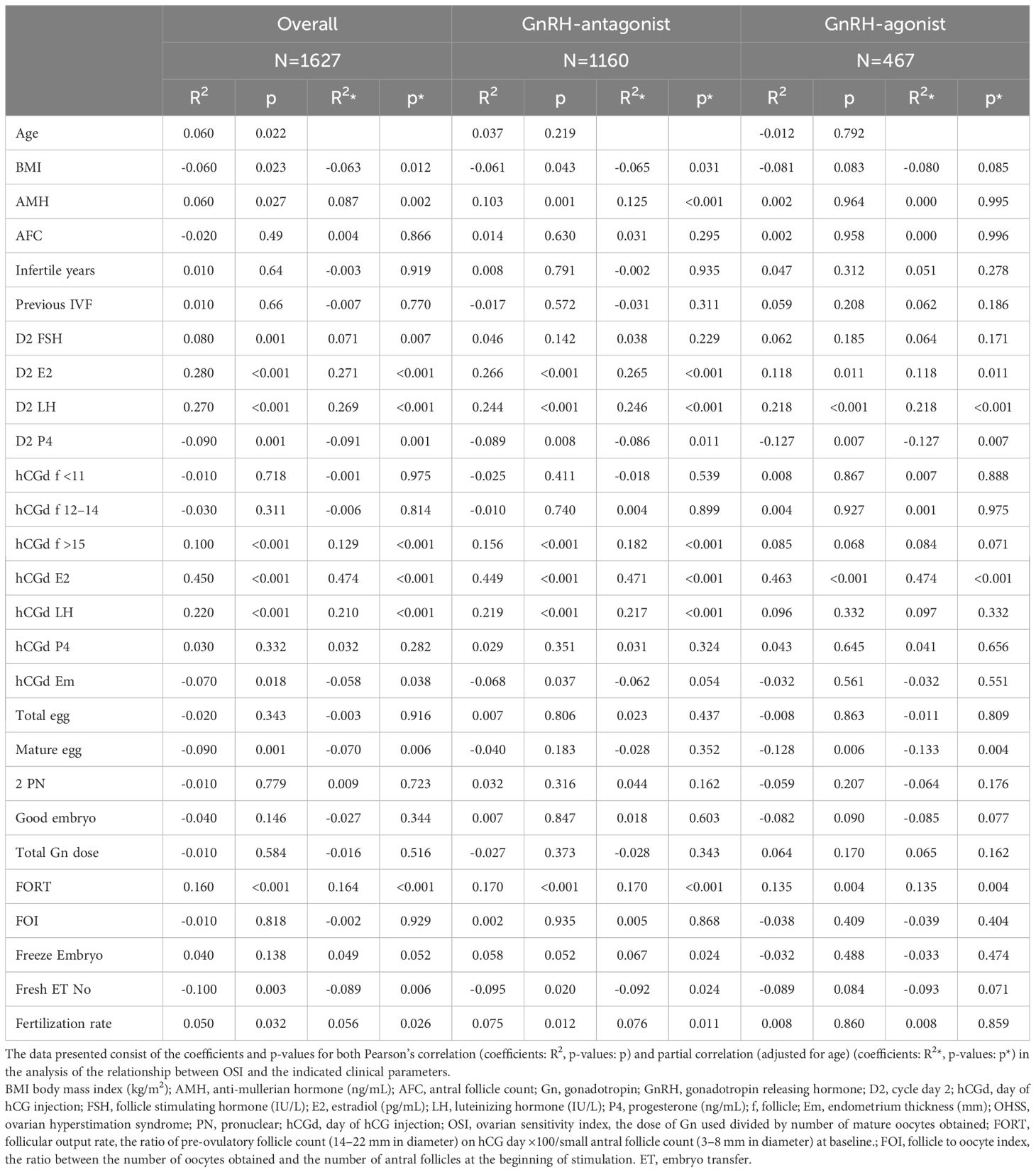

3.4 The correlation between OSI and clinical parameters

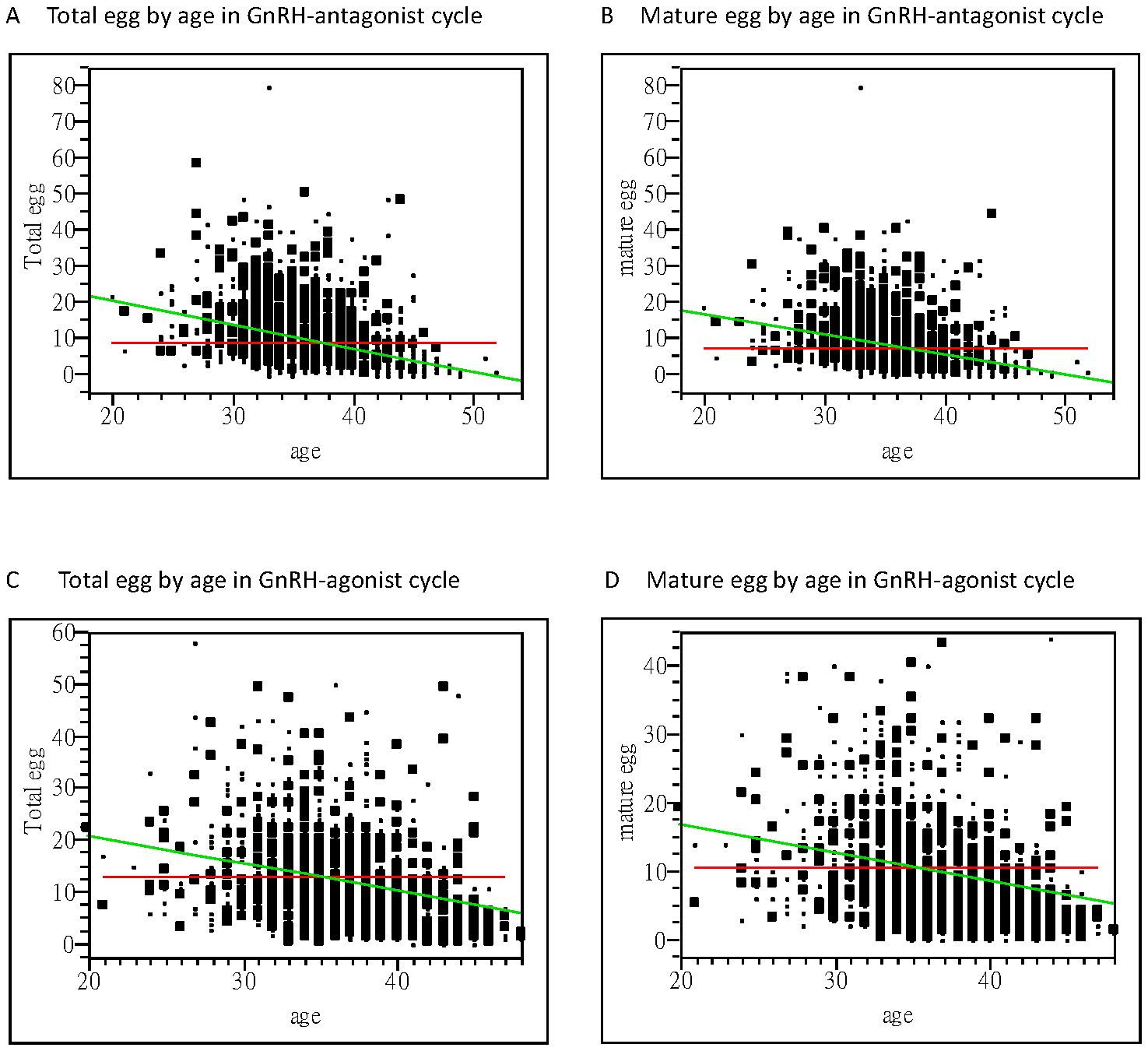

In all the participants, serum AMH, FSH, LH, and E2 at cycle day 2, E2, LH at hCG day, and patients’ age, fertilization rate, and signs of uncontrolled COH (including drop of E2, premature LH surge), and numbers of larger follicles were positively correlated with the OSI. Whereas BMI, serum P4 at day 2, endometrium thickness at hCG day and numbers of mature oocytes, fresh cycle embryo transfer number and dose of GnRH-antag were negatively correlated with the OSI (Tables 4, 5). Among those received GnRH-antag, which represent 71.3% of our participants, the correlation between OSI and clinical parameters studied were similar to the total population. Compared with GnRH-antag cycles, higher negative correlation between numbers of mature oocytes and OSI were noted in women received GnRH-a (Tables 4, 5; Figure 2). In the GnRH-antag group (Figures 3A, C), an OSI of 225.75 significantly distinguished pregnancy from non-pregnancy (p < 0.001), with an AUC of 0.615. It also revealed that an OSI of 208.62 significantly distinguished live births from non-live births, (p < 0.001), with an AUC of 0.637. As for the GnRH-a group (Figures 3B, D), an OSI couldn’t differentiate pregnant from non-pregnant individuals (p=0.320), while an OSI of 228 significantly distinguished live births from non-live births, (p =0.020) with an AUC of 0.569.

Figure 2. Bivariate fit of oocytes retrieved and OSI. (A) Correlation between the total oocytes obtained and OSI, with a correlation coefficient of −0.98 using linear regression analysis (p=0.3359) in the GnRH antagonist cycle. (B) Correlation between the mature oocytes obtained and OSI, with a correlation coefficient of −2.76 using linear regression analysis (p=0.0215) in the GnRH antagonist cycle. (C) Correlation between the total oocytes obtained and OSI, with a correlation coefficient of −0.39 using linear regression analysis (p=0.6715) in the GnRH-agonist cycle. (D) Correlation between the mature oocytes obtained and OSI, with a correlation coefficient of −3.13 using linear regression analysis (p=0.0034) in the GnRH-agonist cycle. OSI, ovarian sensitivity index; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

Figure 3. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve plots demonstrated the ability to distinguish clinical pregnancy outcomes in both the GnRH antagonist group (A) and the GnRH agonist group (B). Additionally, the plots also illustrated the ability to differentiate live birth outcomes in the GnRH antagonist group (C) and the GnRH agonist group (D). We determined the optimal cutoff value for OSI through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. In the GnRH antagonist group (A, C), an OSI of 225.75 significantly distinguished pregnancy from non-pregnancy (p < 0.001), with an AUC of 0.615. The sensitivity and specificity in this group were 0.935 and 0.286, respectively. It also revealed that an OSI of 208.62 significantly distinguished live births from non-live births, (p < 0.001), with an AUC of 0.637. The sensitivity and specificity in this case were 0.840 and 0.421, respectively. As for the GnRH agonist group (B, D), an OSI couldn’t differentiate pregnant from non-pregnant individuals (p=0.320), while an OSI of 228 significantly distinguished live births from non-live births, (p =0.020) with an AUC of 0.569. The sensitivity and specificity were 0.903 and 0.239, respectively. GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; OSI, ovarian sensitivity index.

3.5 Adverse reactions

OHSS was noted in 7.84% (91/1160) and 15.42% (72/467) of patients in the GnRH-antag and GnRH-a treatment cycles, respectively. Among them, 4 and 8 patients experienced severe OHSS, 28 and 29 experienced moderate OHSS, and 59 and 35 experienced mild OHSS in those who received GnRH-antag and GnRH-a, respectively. Thus, moderate-to-severe OHSS was experienced by 2.76% (32/1160) and 7.92% (37/467) in the GnRH-antag and GnRH-a cycles, respectively. No cycle cancellation due to excessive ovarian response was noted in this study.

4 Discussion

In the present study, more mature oocytes and good embryos were obtained in the GnRH-a treatment cycles, which is similar to the results of most previous studies, including many systematic reviews and meta-analysis (15–19). A previous study indicated better synchronization of the follicular cohort with GnRH-a treatment and more natural recruitment of follicles in the follicular phase by employing the GnRH-antag cycle (20). They reported a strong correlation between patient age and the number of oocytes only in the GnRH-antag group (20). However, a strong correlation was noted between the woman’s age and oocytes retrieved from our patients who received either GnRH-a or GnRH-antag COH in the present study. The GnRH-antag COH has been criticized for its relatively low pregnancy rate, and it may be used as a second-line treatment (15, 21). However, our data revealed similar clinical pregnancy and live birth rates when the GnRH-a and GnRH-antag protocols were used. Under equal demographic and clinical features, previous studies have shown similar pregnancy rates with either GnRH-a or GnRH-antag protocols (20, 22). Thus, the advantage of reducing the incidence of OHSS using GnRH-antag protocols without compromising clinical outcomes is encouraged based on our results.

Previous work showed the highest correlation between ovarian response (including OSI) and AFC, AMH, LH-to-FSH ratio, age, and FSH in GnRH-antag COH cycles (10). In the present study, including GnRH-a and GnRH-antag cycles, AMH, hormone status (FSH, E2, and LH levels) on cycle day 2 before COH and E2 and LH levels on the hCG day were positively correlated with OSI. However, BMI, and number of mature oocytes were negatively correlated with OSI in these women. Our results were also different from recent reports in which OSI was inversely related to age and BMI and directly related to AMH and AFC in their GnRH-a and GnRH-antag protocols (23), and another report indicated a negative correlation between OSI and age, FSH, basal FSH/LH, and Gn total dose, and a positive correlation between OSI and AMH, AFC, total oocytes, and mature oocytes (24). However, these studies did not compare the different clinical parameters relevant to OSI separately in either the GnRH-a or GnRH-antag protocols (23, 24). Among those received GnRH-antag in the present study, the correlation between OSI and clinical parameters studied were similar to the total population as described above. Compared with GnRH-antag cycles, negative correlation between numbers of mature oocytes and OSI were noted in women received GnRH-a in our study. For the parameters of AMH and AFC in the present study, only women who received GnRH-antag showed significant correlation with OSI in AMH (correlation coefficient of 0.125; p< 0.001), with no significant correlation with OSI in AFC in either group of women. Thus, our results do not support the previous findings in which the OSI was strongly and significantly correlated with AMH and AFC (7, 25, 26).

A previous study suggested that instead of oocyte number, OSI is a better indicator of the ovarian response to Gn stimulation. For more personalized treatment, OSI has been suggested as an indicator of multiple confounding effects on oocyte number (26). The OSI has also been used as a tool to define poor, normal, and high response patterns in IVF cycles based on the long protocol GnRH-a COH (27). However, a recent study showed a marked intercycle variability of the OSI in 18% of women investigated, suggesting an intrinsic variability of ovarian sensitivity, both with the GnRH-a and GnRH-antag protocols (23). The most remarkable correlation between the OSI and clinical parameters in the present study was the demonstration of the ability to distinguish clinical pregnancy outcomes in both the GnRH-antag group and the GnRH-a group using the optimal cutoff value for OSI through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Our results echo the recent study which showed a strong correlation between OSI values and the clinical pregnancy rate (23, 28). As the results were derived from data of our single institution, further investigations were warrented to confirm our finding using data from other sources. Further studies should be conducted to elucidate more consolidated clinical evidence of employing ovarian responses, including OSI, in IVF treatments, which might aid clinical decisions in the COH protocol.

There are limitations to this study, such as discrepancies in the baseline parameters of our participants; for example, the difference in the participants’ age. One factor might be the accessibility of the medicine; for example, the GnRH-a (Supremone nasal spray; Buserelin acetate, Aventis Pharma Deutschland GMBH, Frankfurt, Germany) routinely used in the long protocol for our patients who underwent IVF was no longer available in Taiwan during the last 6 years. Additionally, the mean age of women receiving IVF treatment in Taiwan has increased from 32.7 to 37.8 years between 1998 and 2021 (29). These may be important factors causing the demographic patterns of the two groups of women to differ. Moreover, retrieving ovarian follicles through vaginal puncture, especially in those suffering marked pelvic and ovarian adhesion or distorted pelvic anatomy due to huge myoma/adenomyoma, and whether or not the operating clinician retrieves oocytes from small follicles may affect OSI accuracy (10). Furthermore, low correlations between patient parameters and OSI have been related to intercycle variations in ovarian responses using the same FSH doses in the same patients (30, 31). Thus, future larger randomized controlled studies should be carried out to achieve more accuracy in the determination of ovarian response to COH, such as OSI, and towards a better elucidation of the ovarian response relevant to clinical outcomes, including clinical pregnancy and live birth rates.

In conclusion, this study reconfirmed the efficiency of both GnRH-a and GnRH-antag in suppressing premature LH surges and premature ovulation in COH for IVF treatment. Similar clinical pregnancy and live birth rates were noted when using either the GnRH-a or GnRH-antag protocols. We further demonstrated the capability of employing OSI to distinguish the clinical pregnancy and live birth outcomes in both GnRH-a and GnRH-antag cycles.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical Committe, Antai Tian-Sheng Memorial Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

CH: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology. SD: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. YC: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology. TC: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. YC: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage for English language editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Honnma H, Baba T, Sasaki M, Hashiba Y, Oguri H, Fukunaga T, et al. Different ovarian response by age in an anti-Müllerian hormone-matched group undergoing in vitro fertilization. J assisted Reprod Genet. (2012) 29:117–25. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9675-9

2. La Marca A, D’Ippolito G. Ovarian response markers lead to appropriate and effective use of corifollitropin alpha in assisted reproduction. Reprod BioMedicine Online. (2014) 28:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.10.012

3. La Marca A, Sunkara SK. Individualization of controlled ovarian stimulation in IVF using ovarian reserve markers: from theory to practice. Hum Reprod update. (2014) 20:124–40. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt037

4. Broekmans F, Kwee J, Hendriks D, Mol B, Lambalk C. A systematic review of tests predicting ovarian reserve and IVF outcome. Hum Reprod update. (2006) 12:685–718. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml034

5. Nelson SM, Yates RW, Fleming R. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone and FSH: prediction of live birth and extremes of response in stimulated cycles—implications for individualization of therapy. Hum Reproduction. (2007) 22:2414–21. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem204

6. La Marca A, Grisendi V, Giulini S, Argento C, Tirelli A, Dondi G, et al. Individualization of the FSH starting dose in IVF/ICSI cycles using the antral follicle count. J Ovarian Res. (2013) 6:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-11

7. Biasoni V, Patriarca A, Dalmasso P, Bertagna A, Manieri C, Benedetto C, et al. Ovarian sensitivity index is strongly related to circulating AMH and may be used to predict ovarian response to exogenous gonadotropins in IVF. Reprod Biol Endocrinology. (2011) 9:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-112

8. Gallot V, Berwanger da Silva A, Genro V, Grynberg M, Frydman N, Fanchin R. Antral follicle responsiveness to follicle-stimulating hormone administration assessed by the Follicular Output RaTe (FORT) may predict in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer outcome. Hum reproduction. (2012) 27:1066–72. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der479

9. Alviggi C, Conforti A, Esteves SC, Vallone R, Venturella R, Staiano S, et al. Understanding ovarian hypo-response to exogenous gonadotropin in ovarian stimulation and its new proposed marker—the follicle-to-oocyte (FOI) index. Front endocrinology. (2018) 9:589. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00589

10. Chalumeau C, Moreau J, Gatimel N, Cohade C, Lesourd F, Parinaud J, et al. Establishment and validation of a score to predict ovarian response to stimulation in IVF. Reprod Biomedicine Online. (2018) 36:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.09.011

11. Cesarano S, Pirtea P, Benammar A, De Ziegler D, Poulain M, Revelli A, et al. Are there ovarian responsive indexes that predict cumulative live birth rates in women over 39 years? J Clin Med. (2022) 11:2099. doi: 10.3390/jcm11082099

12. Hsu C-C, Hsu I, Lee L-H, Hsu R, Hsueh Y-S, Lin C-Y, et al. Ovarian follicular growth through intermittent vaginal gonadotropin administration in diminished ovarian reserve women. Pharmaceutics. (2022) 14:869. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14040869

13. Hsu CC, Hsu I, Chang HH, Hsu R, Dorjee S. Extended injection intervals of gonadotropins by intradermal administration in IVF treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2022) 107:e716–e33. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab709

14. Hsu C-C, Hsu I, Lee L-H, Hsueh Y-S, Lin C-Y, Chang HH. Intraovarian injection of recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone for luteal-phase ovarian stimulation during oocyte retrieval is effective in women with impending ovarian failure and diminished ovarian reserve. Biomedicines. (2022) 10:1312. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10061312

15. Al-Inany H, Abou-Setta A, Aboulghar M. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonists for assisted conception: a Cochrane review. Reprod biomedicine online. (2007) 14:640–9. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61059-0

16. Kadoura S, Alhalabi M, Nattouf AH. Conventional GnRH antagonist protocols versus long GnRH agonist protocol in IVF/ICSI cycles of polycystic ovary syndrome women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:4456. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08400-z

17. Wang R, Lin S, Wang Y, Qian W, Zhou L. Comparisons of GnRH antagonist protocol versus GnRH agonist long protocol in patients with normal ovarian reserve: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. (2017) 12:e0175985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175985

18. Lambalk C, Banga F, Huirne J, Toftager M, Pinborg A, Homburg R, et al. GnRH antagonist versus long agonist protocols in IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis accounting for patient type. Hum Reprod update. (2017) 23:560–79. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx017

19. Yang R, Guan Y, Perrot V, Ma J, Li R. Comparison of the long-acting GnRH agonist follicular protocol with the GnRH antagonist protocol in women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Ther. (2021) 38:2027–37. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01612-7

20. Depalo R, Lorusso F, Palmisano M, Bassi E, Totaro I, Vacca M, et al. Follicular growth and oocyte maturation in GnRH agonist and antagonist protocols for in vitro fertilisation and embryo transfer. Gynecological Endocrinology. (2009) 25:328–34. doi: 10.1080/09513590802617762

21. Depalo R, Jayakrishan K, Garruti G, Totaro I, Panzarino M, Giorgino F, et al. GnRH agonist versus GnRH antagonist in in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF/ET). Reprod Biol endocrinology. (2012) 10:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-26

22. Engel JB, Griesinger G, Schultze-Mosgau A, Felberbaum R, Diedrich K. GnRH agonists and antagonists in assisted reproduction: pregnancy rate. Reprod biomedicine online. (2006) 13:84–7. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)62019-6

23. Revelli A, Gennarelli G, Biasoni V, Chiadò A, Carosso A, Evangelista F, et al. The ovarian sensitivity index (OSI) significantly correlates with ovarian reserve biomarkers, is more predictive of clinical pregnancy than the total number of oocytes, and is consistent in consecutive IVF cycles. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:1914. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061914

24. He Y, Liu L, Yao F, Sun C, Meng M, Lan Y, et al. Assisted reproductive technology and interactions between serum basal FSH/LH and ovarian sensitivity index. Front Endocrinology. (2023) 14:1086924. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1086924

25. Broer S, Dólleman M, Opmeer B, Fauser B, Mol B, Broekmans F. AMH and AFC as predictors of excessive response in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation: a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod update. (2011) 17:46–54. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq034

26. Li HWR, Lee VCY, Ho PC, Ng EHY. Ovarian sensitivity index is a better measure of ovarian responsiveness to gonadotrophin stimulation than the number of oocytes during in-vitro fertilization treatment. J assisted Reprod Genet. (2014) 31:199–203. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0144-5

27. Huber M, Hadziosmanovic N, Berglund L, Holte J. Using the ovarian sensitivity index to define poor, normal, and high response after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in the long gonadotropin-releasing hormone-agonist protocol: suggestions for a new principle to solve an old problem. Fertility sterility. (2013) 100:1270–6. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.06.049

28. Pan W, Tu H, Jin L, Hu C, Xiong J, Pan W, et al. Comparison of recombinant and urinary follicle-stimulating hormones over 2000 gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist cycles: a retrospective study. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:5329. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41846-2

29. Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. The Assisted Reproductive Technology Summary 2021 National Report of Taiwan SEP 2023 . Available online at: https://www.hpa.gov.tw/File/Attach/17531/File_22374.pdf (accessed September 2023).

30. Brodin T, Hadziosmanovic N, Berglund L, Olovsson M, Holte J. Comparing four ovarian reserve markers–associations with ovarian response and live births after assisted reproduction. Acta obstetricia gynecologica Scandinavica. (2015) 94:1056–63. doi: 10.1111/aogs.2015.94.issue-10

31. Rombauts L, Lambalk CB, Schultze-Mosgau A, van Kuijk J, Verweij P, Gates D, et al. Intercycle variability of the ovarian response in patients undergoing repeated stimulation with corifollitropin alfa in a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist protocol. Fertility Sterility. (2015) 104:884–90. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.06.027

Keywords: GnRH-agonist, GnRH-antagonist, ovarian sensitivity index, controlled ovarian hyperstimulation, in vitro fertilization, clinical pregnancy rate, live birth rate

Citation: Hsu CC, Hsu I, Dorjee S, Chen YC, Chen TN and Chuang YL (2024) Ovarian sensitivity index affects clinical pregnancy and live birth rates in gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and antagonist in vitro fertilization cycles. Front. Endocrinol. 15:1457435. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1457435

Received: 30 June 2024; Accepted: 26 November 2024;

Published: 13 December 2024.

Edited by:

Jan Tesarik, MARGen Clinic, SpainReviewed by:

Yujia Zhang, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United StatesRavikrishna Cheemakurthi, Krishna IVF Clinic, India

Copyright © 2024 Hsu, Hsu, Dorjee, Chen, Chen and Chuang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chao Chin Hsu, dHViZTIzNjM4MDhAZ21haWwuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Chao Chin Hsu

Chao Chin Hsu Isabel Hsu

Isabel Hsu Sonam Dorjee1

Sonam Dorjee1