94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Endocrinol. , 30 August 2022

Sec. Obesity

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.983180

Kirubel Dagnaw Tegegne1*

Kirubel Dagnaw Tegegne1* Gebeyaw Biset Wagaw2

Gebeyaw Biset Wagaw2 Natnael Atnafu Gebeyehu3

Natnael Atnafu Gebeyehu3 Lehulu Tilahun Yirdaw4

Lehulu Tilahun Yirdaw4 Nathan Estifanos Shewangashaw1

Nathan Estifanos Shewangashaw1 Nigusie Abebaw Mekonen5

Nigusie Abebaw Mekonen5 Mesfin Wudu Kassaw6

Mesfin Wudu Kassaw6Introduction: Obesity is a global public health concern that is now on the rise, especially in low- and middle-income nations. Despite the fact that there are several studies reporting the prevalence of central obesity among adults in Ethiopia, there is a lack of a systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizing the existing observational studies. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the prevalence of central obesity and its associated factors in Ethiopia.

Methods: Online libraries such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Science Direct, and Addis Ababa University were searched. Data were extracted using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using STATA statistical software (v. 16). Forest plots, Begg’s rank test, and Egger’s regression test were all used to check for publication bias. To look for heterogeneity, I2 was computed, and an overall estimated analysis was carried out. Subgroup analysis was done by region and study setting. In addition, the pooled odds ratio for related covariates was calculated.

Results: Out of 685 studies assessed, 20 met our criteria and were included in the study. A total of 12,603 people were included in the study. The prevalence of central obesity was estimated to be 37.31% [95% confidence interval (CI): 29.55–45.07]. According to subgroup analysis by study region and setting, the highest prevalence was observed in the Dire Dawa region (61.27%) and community-based studies (41.83%), respectively. Being a woman (AOR = 6.93; 95% CI: 3.02–10.85), having better socioeconomic class (AOR = 5.45; 95% CI: 0.56–10.34), being of age 55 and above (AOR = 5.23; 95% CI: 2.37–8.09), being physically inactive (AOR = 1.80; 95% CI: 1.37–2.24), being overweight (AOR = 4.00; 95% CI: 2.58–5.41), being obese (AOR = 6.82; 95% CI: 2.21–11.43), and having hypertension (AOR = 3.84; 95% CI: 1.29–6.40) were the factors associated with central obesity.

Conclusion: The prevalence of central obesity was high in Ethiopia. Being a woman, having a higher socioeconomic class, being older, being physically inactive, being overweight or obese, and having hypertension were all associated. Therefore, it is vital for the government and health organizations to design and implement preventive measures like early detection, close monitoring, and positive reversal of central obesity in all patients and the general population. High-quality investigations on the prevalence of central obesity in the Ethiopian people are required to better understand the status of central obesity in Ethiopia.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO, identifier: CRD42022329234.

Obesity is a serious and pressing public health issue. Over the last few decades, the prevalence has steadily increased, with rates nearly tripling since 1975 to the point where 30% of the world’s population are overweight or obese (1). In 2016, an estimated 1.9 billion adults worldwide were overweight, about 650 million of them being obese. Obesity is becoming a global public health concern, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (2). Every year, 1.8 million individuals die prematurely as a result of noncommunicable diseases, in which obesity plays a key role (3).

Despite the fact that obesity was previously thought to be an issue only in high-income countries, recent reports reveal a dramatic increase in overweight and obesity in various LMICs (4). Whereas obesity in higher-income nations has been plateauing since the mid-2000s, it has been quickly increasing in LMICs, especially in numerous African countries, during the same time period (5). Obesity is common in Ethiopia, with 30% in Addis Ababa (6) and 28.5% in Hawasa, according to community-based surveys (7).

Obesity is a multifactorial medical condition characterized by complex pathogenesis involving biological (8), psychosocial (9), socioeconomic (10), and environmental factors (11, 12) and heterogeneity in the pathways and mechanisms by which it leads to adverse health outcomes (13, 14). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines central obesity (abdominal obesity) as a waist circumference (WC) of greater than 94 and 80 cm for men and women, respectively (15). Overall obesity and central obesity have a strong correlation. WC is an indicator of central obesity, which is linked with cardiometabolic diseases and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and is predictive of mortality (16, 17). Despite overall obesity being established as a cardiometabolic risk factor, central obesity is the strongest predictor of this risk regardless of the body mass index (BMI) (18, 19). In a recent study, it 7was discovered that WC had a better integrated discrimination index than the BMI in both men (6.9% versus 3.2%) and women (9.6% versus 9.2%) (20). Although High Density Lipoprotein cholesterol, High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (HDL-C), hypertension, and diabetes increase the risk of CVD, central obesity remained the single significant factor for the risk after controlling for these factors. This implies that central obesity is the primary target for primary prevention of CVD. Furthermore, central obesity has been linked to a variety of health issues, including stroke (21), type 2 diabetes mellitus (22), hypertension (23), cancers, and all-cause mortality (24).

In Ethiopia, numerous cross-sectional studies have investigated the prevalence of central obesity and its associated factors among adults. These small and fragmented studies reported that central obesity among adults varied from 16.45% in Northern Ethiopia (25) to 76.1% in Eastern Ethiopia (26). These studies are small in sample size and confined in a certain geographic area, which cannot show the country-level prevalence of central obesity. Thus, a systematic review and meta-analysis is required as it provides a comprehensive overview of central obesity as a country-level burden. Given that there is no previous systematic review conducted, we aim to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of central obesity and its associated factors in Ethiopia. We pooled central obesity prevalence estimates from different regions of Ethiopia and analyzed the prevalence and associated factors of central obesity among Ethiopian adults. Estimating the country-level prevalence of central obesity and identifying the associated factors is crucial as it may inform strategy design and policy-making to mitigate the burden through health education, screening, and early intervention.

This systematic review and meta-analysis study was conducted to determine the pooled prevalence of central obesity and its associated factors in Ethiopia using the standard PRISMA checklist guideline (27) (Table S1). This systematic review and meta-analysis is registered in PROSPERO under a registration number of CRD42022329234 and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO.

International online databases (Pub Med, Science Direct, Scopus, and Google Scholar) were used to search articles on the prevalence of central obesity. We also retrieved gray literature from Addis Ababa University’s online research institutional repository. The search string was established using “AND” and “OR” Boolean operators. The following core search terms and phrases with Boolean operators were used to search related articles: [(prevalence) OR (magnitude) OR (proportion) AND (central obesity) OR (abdominal obesity) OR (abdominal adiposity) OR (central fatness) OR (visceral obesity) OR (visceral adiposity) OR (metabolic syndrome) OR (metabolic risk factor) OR (cardiometabolic risk factor)) OR (waist circumference) AND (factors) OR (determinants) OR (predictors) AND (adults) OR (elders) OR (geriatrics) AND (Ethiopia)]. Search terms were based on PICO principles to retrieve relevant articles through the databases mentioned above. The search period was from 1 April 2022 to 5 May 2022.

All adults with WC greater than 94 and 80 cm for men and women, respectively, were considered to have central obesity (15).

This meta-analysis includes studies that reported the prevalence of central obesity in adults as study participants, only English language publications, both published and unpublished studies with full text available for search, and studies that took place in Ethiopia. Studies published between 1 January 2000 and 20 March 2022 were included. Studies that reported duplicated sources, qualitative studies from developed countries, studies with unreported outcome of interest, and articles without full text available were excluded from this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Two authors (KDT and NAG) independently appraised the standard of the studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardized quality appraisal checklist (28). The disagreement raised during the quality assessment was resolved through a discussion led by the third author (GBW). Finally, the argument was solved and an agreement was reached. The critical analysis checklist has eight parameters with yes, no, unclear, and not applicable options. The parameters involve the following questions:

1. Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined?

2. Were the study described the study setting and participants in detail?

3. Did the exposure measure the result validly and reliably?

4. Were the main objective and standard criteria used to measure the event?

5. Were confounding factors identified?

6. Did the study use strategies to deal with confounders?

7. Did the study use valid and reliable outcome measurement?

8. Was the statistical analysis appropriate?

Studies were considered of low risk when they scored 50% and above on the quality assessment indicators, as reported in a supplementary file (Table S2).

Two authors (KDT and NAG) independently assessed included studies for risk of bias through the bias assessment tool developed by Hoy et al. (29), consisting of 10 items that assess four domains of bias and internal and external validity. Any disagreement raised during the risk of bias assessment was resolved through a discussion led by the third author (GBW). Finally, the argument was solved and an agreement reached. The first four items (items 1–4) evaluate the presence of selection bias, nonresponse bias, and external validity. The other six items (items 5–10) assess the presence of measuring bias, analysis-related bias, and internal validity. Therefore, studies that received “yes” for eight or more of the 10 questions were classified as “low risk of bias”. Studies that received “yes” for six to seven of the 10 questions were classified as ”moderate risk”, whereas studies that received “yes” for five or fewer of the 10 questions were classified as “high risk”, as reported in a supplementary file (Table S3).

Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (2016) and STATA version 16 software were utilized for data extraction and analysis, respectively. Two authors (KDT and GBW) independently extracted all relevant data using a standardized JBI data extraction format. The disagreement raised during data extraction was resolved through a discussion led by the third author (LTY). Finally, the argument was solved and an agreement reached. The data automation tool was not used due to this study’s absence of the paper form (manual data). The name of the first author, the year of publication, the study region, the study setting, the study design, the prevalence of central obesity, the sample size, and the quality of each paper were extracted.

After extracting all relevant findings in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, the data were exported to STATA software version 16 for analysis. The pooled prevalence of central obesity was computed using a 95% confidence interval (CI). Publication bias was checked by a funnel plot and more objectively through Begg’s and Egger’s regression tests (30), and a p-value less than 0.05 indicates that it is statistically significant (31). The presence of between-study heterogeneity was checked by using the Cochrane Q statistic. This heterogeneity between studies was quantified using I2, in which values of 25%, 50%, and 75% represented low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively (32). We used a forest plot to visually assess the presence of heterogeneity, which, as presented at a high-level random-effects model, was used for analysis to estimate the overall prevalence of central obesity. Subgroups were classified according to study setting (community setting versus institutional setting) and region (between 10 regions). Sensitivity analysis was executed to see the effect of a single study on the overall prevalence of the meta-analysis estimate. The findings of the study were presented in the form of text, tables, and figures.

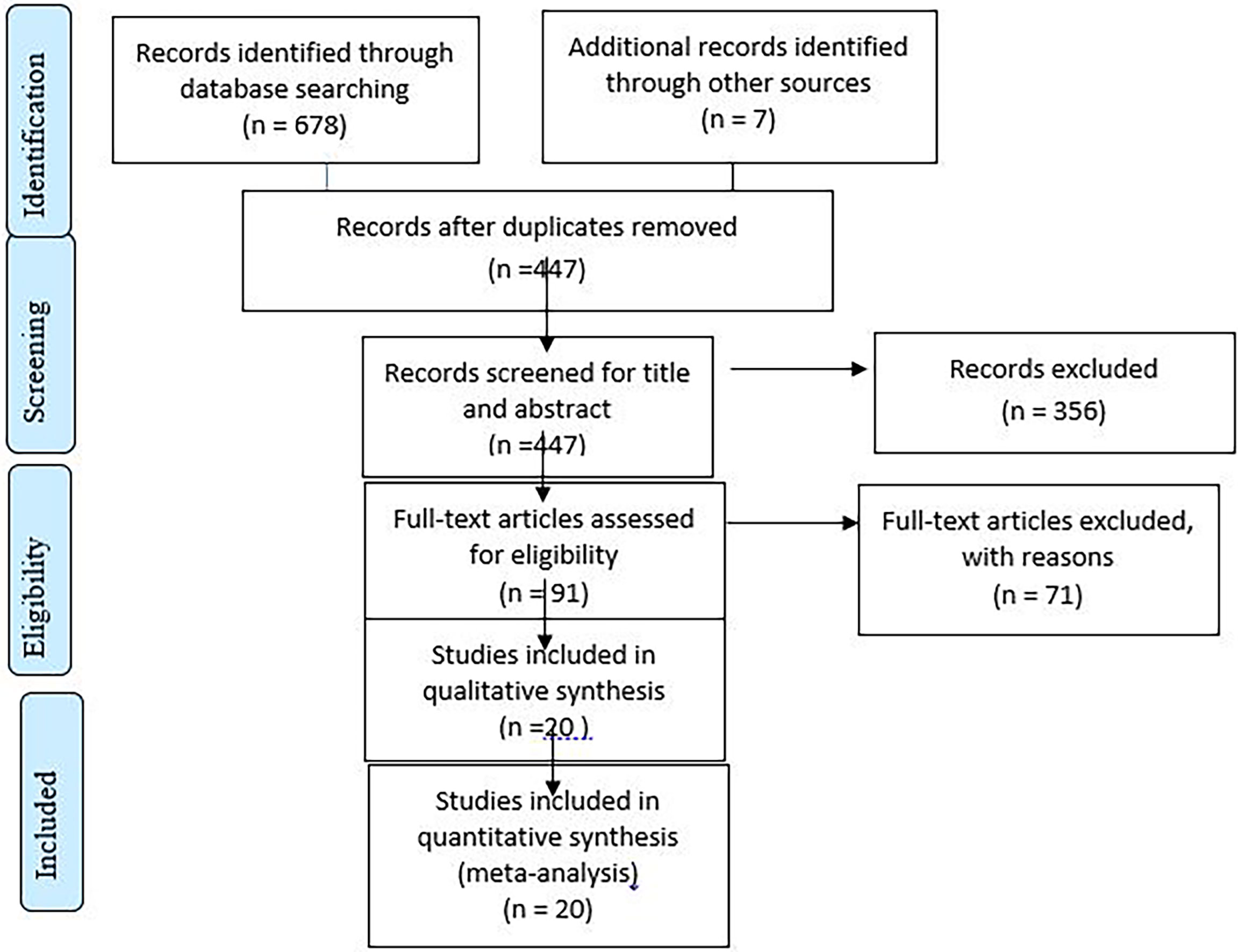

The literature search has yielded 685 records through electronic databases of PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Science direct, and online research repository home. After duplicates were removed, 447 articles remained. Then, 356 studies were excluded after reviewing for full title and abstracts from the remaining 447 studies. Therefore, 91 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility criteria, which further excluded 71 studies due to unreported outcome of interest and being from different study populations or areas. Finally, 20 articles were included as the criteria for this systematic review and meta-analysis study (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Flow chart illustrating the process of search and selection of studies included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis.

All included studies were employed by cross-sectional study design. Of these, five studies were community-based, whereas 15 were institutional-based cross-sectional studies: six studies in Amhara (25, 33–37), five studies in Addis Ababa (38–42), three studies in Tigray (43–45), two studies in Oromia (46, 47), two studies in Dire Dawa (26, 48), one study in Southern Nations Nationalists and Peoples Region (49), and one study in Harari (50). The sample sizes ranged from 225 to 1,935. The prevalence of central obesity ranges from 16.45 to 76.1. All studies were assessed by using the JBI quality appraisal checklist. Finally, 20 cross-sectional studies were evaluated, and all received a quality score of 75% or above on the quality scale, indicating that they are of low risk and included in the analysis (Table 1).

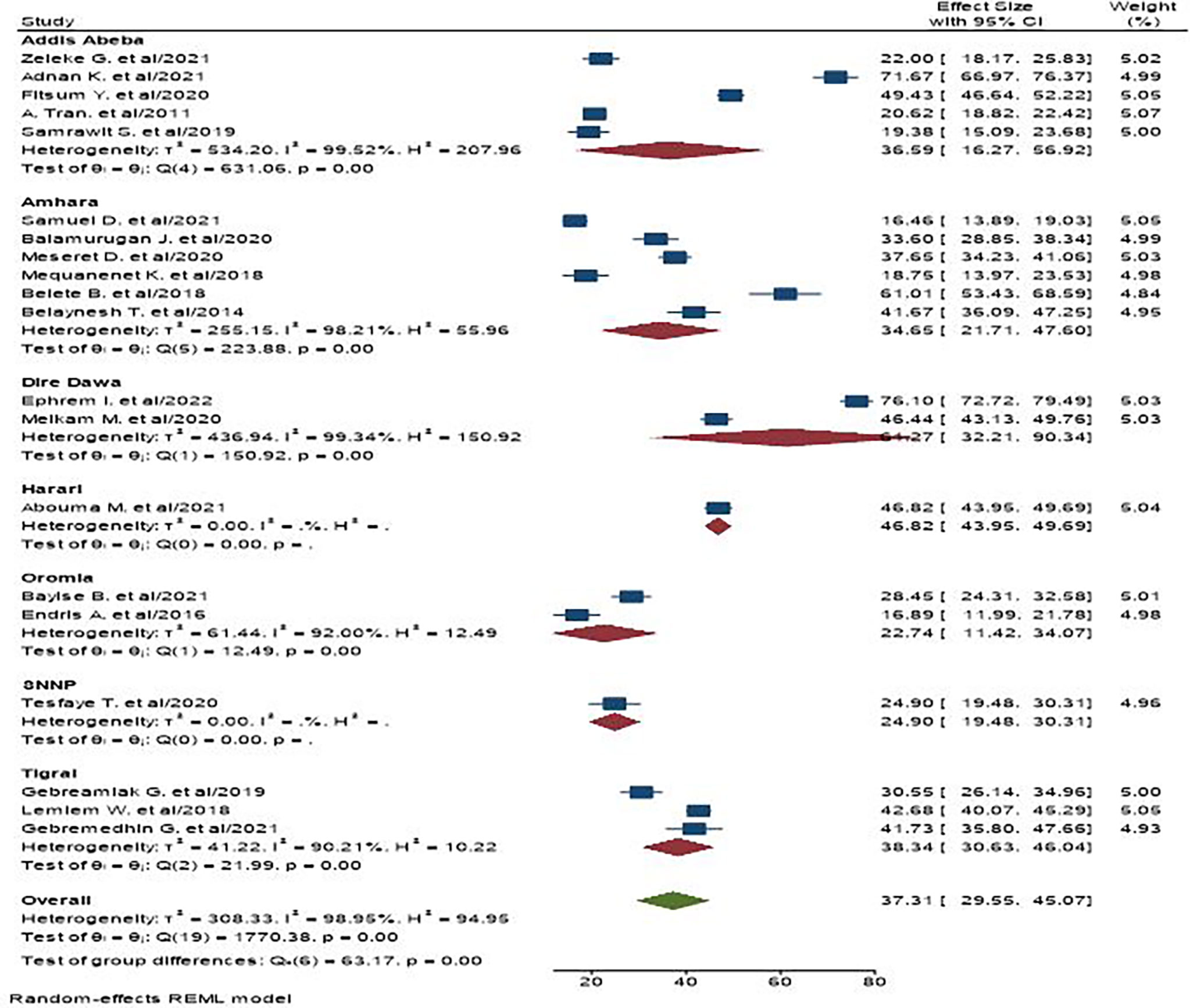

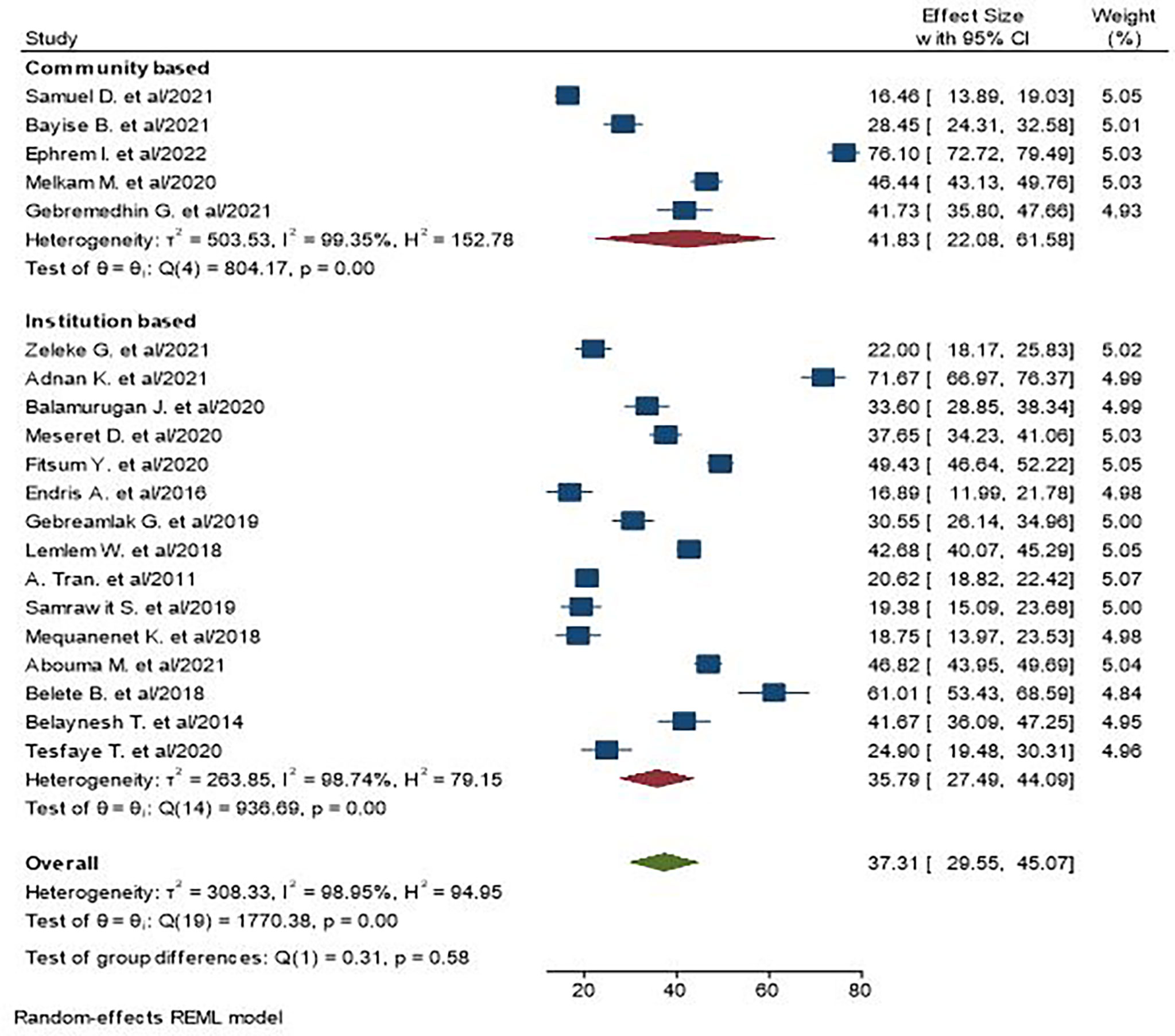

The random-effects pooled prevalence of central obesity in Ethiopia was 37.31% (95% CI: 29.55–45.07), with significant heterogeneity observed between studies (I2 = 98.95%, P < 0.00) (Figure 2).

We observed high heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 98.95%). As a result, subgroup analysis was conducted on the basis of study region and setting. As per the region, the highest pooled prevalence of central obesity was found at 61.27% in Dire Dawa, and in the context of study setting, the pooled prevalence in community-based studies appeared to be higher, i.e., 41.83% (Figures 3, 4).

Figure 3 The pooled prevalence of central obesity among adult populations based on region the study is conducted in Ethiopia.

Figure 4 The pooled prevalence of central obesity among adult populations based on setting in Ethiopia.

The presence of publication bias was checked using funnel plot visualization and Egger’s and Begg’s regression tests (P < 0.05). Egger’s and Begg’s tests both revealed no statistical evidence of publication bias for prevalence of central obesity (P = 0.5432 and P = 0.9225), respectively (Figures 5, 6).

To check the individual effect of included studies on the pooled prevalence of central obesity in Ethiopia, sensitivity analysis was performed using a random effect model, and the result revealed that no single study influenced the pooled prevalence of central obesity among adults. The pooled estimated prevalence of central obesity was estimated from 35.22 (28.59, 41.85) to 38.4 (30.64, 46.16) after omission of a single study (Figure 7).

There are many factors associated with central obesity among adults in primary studies, but variables reported as a significant factor of central obesity in at least two primary studies were included in this meta-analysis. As a result, being a woman, having high socioeconomic status, being of age 55 and above, being physically inactive, being overweight or obese, and having hypertension are factors associated with central obesity.

As a result, being a woman (AOR = 6.93; 95% CI: 3.02–10.85; I2 = 99.65%, P = 0.00) is nearly seven times more likely to be obese compared with their counterparts. The odds of central obesity among people with higher socioeconomic status (AOR = 5.45; 95% CI: 0.56–10.34; I2 = 98.59%, P = 0.00) were five times more likely than those with lower socioeconomic status. The finding of our study showed that the odds of central obesity among older people of age greater than 55 (AOR = 5.23; 95% CI: 2.37–8.09; I2 = 96.86%, P = 0.00) were five times more than those who are of younger age. Moreover, this study showed that the prevalence of central obesity among people who are physically inactive (AOR = 1.80; 95% CI: 1.37–2.24; I2 = 41.76, P = 0.00) was 1.8 times more than adults who are physically active. The odds of central obesity of adults who are overweight (AOR = 4.00; 95% CI: 2.58–5.41; I2 = 0.00%, P = 0.00) were four times more likely than adults who are not overweight. Our finding also showed that the prevalence of central obesity among obese adults (AOR = 6.82; 95% CI: 2.21–11.43; I2 = 94.00%, P = 0.00) was 6.8 times more likely than adults who are not obese. Moreover, adults with hypertension (AOR = 3.84; 95% CI: 1.29–6.40; I2 = 95.75%, P = 0.00) were 3.8 times more likely than adults who are not overweight (Table 2).

This review was conducted to determine the pooled prevalence of and factors for central obesity among adults aged 18 years and older in Ethiopia. To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review and meta-analysis is the first English-language study on the prevalence of central obesity among Ethiopian adults. In this meta-analysis, 20 articles with a total of 12,603 study subjects were included. The overall prevalence of central obesity in this study was 37.31% (95% CI: 29.55–45.07).

This higher figure of central obesity attributed to increased gender differences (36, 51), educational attainment and socioeconomic status (52), physical inactivity (26), and other diseases such as diabetes and hypertension (25, 53). Consistent with our result, the global prevalence of central obesity was reported to be 41.5% (54). Our results are likewise comparable to those reported in Nigeria (39%) (55) and China (37.6%) (56). One study among the population of 25–64 years old found that 22.5% of adults were centrally obese (57). Variations in the study population and geographical area can explain the disparity. Other studies such as those by Eyitayo et al. showed 67% (58)—a higher prevalence of central obesity compared with ours, which is 37.31% (95% CI: 29.55–45.07). A higher socioeconomic level and associated unhealthy lifestyle in South Africa relative to Ethiopia might explain the difference. Higher socioeconomic status is linked with the occurrence of central obesity (59).

A wide range of central obesity prevalence was found among the included studies, which could be attributable to the high heterogeneity of the samples included in this review. As a result, we further performed subgroup analyses by study region and setting related to central obesity. Thus, on the basis of region, Dire Dawa has the highest prevalence of central obesity, which is 61.27%. Dire Dawa is one of the metropolitan cities in the country, where industrialization and urbanization are higher compared with the rural areas in the country. Individuals who live in urban areas and industrialized towns are at a higher risk of getting central obesity due to their overconsumption of processed and energy-dense foods more frequently than that of the rural people (60, 61). Moreover, the prevalence of central obesity in a community setting is higher than institutions. This can be explained, in part, by people with obesity in the community who are less likely to seek obesity care in health institutions unless they have obesity-related diseases (62). Sample size and study population variations can be additional contributors for the difference between the two settings.

We found that being a woman is a significant predictor of central obesity; women appear to be nearly seven times more likely to develop central obesity. This result is in line with various previous studies (54, 55, 63, 64). Biological differences where women have higher body fat composition compared to men could be the reason for the variation between females and males. Cultural and social restrictions imposed on women might also explain this gender difference. Women tend to be less physically active due to lower educational level, sedentary lifestyle, and higher household activities engagement (65, 66). Furthermore, sex hormones and the effect of menopause could explain the difference between men and women. Central obesity seems to be linked with low levels of testosterone as the hormone increases fat consumption and thus decreases central obesity (67–69).

Previous studies have shown that aging is strongly associated with the prevalence of central obesity (54, 57, 64). The present study results also show the natural pattern of central obesity increase with age, and the highest prevalence of central obesity was seen in people over 55 years. Aged people become often less active, which contributes to reduced energy expenditure, and this leads to fat accumulation in the abdominal area (70). In addition, our study revealed that people from higher socioeconomic status are more likely to be centrally obese, and this result is supported by studies conducted globally (54). Studies suggest that, in lower-income countries, people from higher socioeconomic status are more likely to be obese (71). Similarly, this may also be applied to central obesity. The high prevalence of central obesity from higher socioeconomic family underscores the importance for policy-makers and clinicians to design strategies favorable for patients and the general population. Physical inactivity is the other critical factor that drives people to be centrally obese. Physical inactivity has become increasingly popular over the past few decades and may have contributed to the upsurge of central obesity. A study from the global perspective (54) also mentioned that physical inactivity accounts for the problem of central obesity. The current low levels of physical activity attributed to rapid urbanization and associated sedentary behaviors in working and domestic environments (72).

This systematic review showed that being overweight or obese is associated with central obesity. We found that people who are overweight and obese are 4 and 6.8 times more likely to be centrally obese, respectively. People who are overweight or obese can gain extra fat throughout the whole body, and this includes fat accumulation in the abdominal area, named as central obesity. It is also evident that being hypertensive is associated with central obesity. As shown in our study, patients who are hypertensive are 3.8 times more likely to be centrally obese compared with those without hypertension. Activation of the renin-angiotensin system in hypertension is well known and plays a role in insulin resistance, which contributes to central obesity (73). This implies that designing health education strategies and early control of hypertension by the concerned bodies is a priority. Overall, the implications for policy-makers, health professionals, and supporting agencies are to encourage the prevention of central obesity, weight loss, and more physical activity in women and older population, and to manage other comorbidities such as hypertension.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that the prevalence of central obesity is increasing. Moreover, the pooled prevalence of central obesity varies on the basis of study settings and regions. Being a woman, having high socioeconomic status, being of age 55 and above, being physically inactive, being overweight or obese, and having hypertension were factors associated with central obesity. Therefore, it is vital for the government and health organizations to design and implement preventive measures like early detection, close monitoring, and positive reversal of central obesity in all patients and the general population. High-quality investigations on the prevalence of central obesity in the Ethiopian people are required to better understand the status of central obesity in Ethiopia.

This study has some limitations. First, articles were restricted to only being published in the English language, which may result in the exclusion of other articles. Second, the meta-analyses revealed high heterogeneity in the estimated pooled prevalence. Sample size variations, geographical areas, and other different factors in the studies might explain the high heterogeneity of estimates observed in the current study. Therefore, the results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted cautiously. Third, all included studies were cross-sectional, which might affect the outcome variable because of other confounding factors.

This study has strengths. First, compressive electronic online international search engines were used. Second, both published and unpublished (gray literature) studies were included in this review. Third, factors associated with central obesity were identified.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

KT conceptualized the study; KT, GB, and LT contributed during data extraction and analysis; KT, GB, and NS interpreted the results; KT and GB prepared the first draft; KT, NG, GB, and LT contributed during the conceptualization and interpretation of results and substantial revision; KT, NM, NS, GB, MK, and LT revised and finalized the final draft manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2022.983180/full#supplementary-material

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular diseases; JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute; LMICs, low- and middle-income countries; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; WC, waist circumference; WHO, World Health Organization.

1. Organization WH. Obesity and overweight (2020). Available at: https://wwwwho.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight27.

2. Organization. WH. Obesity and overweight (2018). Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/.

3. Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation (2001) 104(22):2746–53. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487

4. Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet (9945) 2014:766–81:384. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8

5. Ford ND, Patel SA, Narayan KV. Obesity in low-and middle-income countries: burden, drivers, and emerging challenges. Annu Rev Public Health (2017) 38:145–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044604

6. Non-Communicable O. National strategic action plan (nsap) for prevention & control of non-communicable diseases in Ethiopia. (2016) Addis Ababa, Ministry of Health.

7. Darebo T, Mesfin A, Gebremedhin S. Prevalence and factors associated with overweight and obesity among adults in hawassa city, southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Obes (2019) 6(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40608-019-0227-7

8. Loos RJ. Genetic determinants of common obesity and their value in prediction. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab (2012) 26(2):211–26. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2011.11.003

9. Gebreab SZ, Vandeleur CL, Rudaz D, Strippoli M-PF, Gholam-Rezaee M, Castelao E, et al. Psychosocial stress over the lifespan, psychological factors, and cardiometabolic risk in the community. Psychosomatic Med (2018) 80(7):628–39. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000621

10. Sommer I, Griebler U, Mahlknecht P, Thaler K, Bouskill K, Gartlehner G, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in non-communicable diseases and their risk factors: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health (2015) 15(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2227-y

11. Franks PW, McCarthy MI. Exposing the exposures responsible for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Science (2016) 354(6308):69–73. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5094

12. Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Quarterly (2009) 87(1):123–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00550.x

13. Gordon-Larsen P, Heymsfield SB. Obesity as a disease, not a behavior. Circulation (2018) 137(15):1543–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.032780

14. Jastreboff AM, Kotz CM, Kahan S, Kelly AS, Heymsfield SB. Obesity as a disease: the obesity society 2018 position statement. Obesity (2019) 27(1):7–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.22378

15. Organization WH. Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio: report of a WHO expert consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization (2011) p. 8–11.

16. Piché M-E, Poirier P, Lemieux I, Després J-P. Overview of epidemiology and contribution of obesity and body fat distribution to cardiovascular disease: an update. Prog Cardiovasc Dis (2018) 61(2):103–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2018.06.004

17. Sahakyan KR, Somers VK, Rodriguez-Escudero JP, Hodge DO, Carter RE, Sochor O, et al. Normal-weight central obesity: implications for total and cardiovascular mortality. Ann Internal Med (2015) 163(11):827–35. doi: 10.7326/M14-2525

18. Reis JP, Macera CA, Araneta MR, Lindsay SP, Marshall SJ, Wingard DL. Comparison of overall obesity and body fat distribution in predicting risk of mortality. Obesity (2009) 17(6):1232–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.664

19. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Bautista L, Franzosi MG, Commerford P, et al. Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27 000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. Lancet (2005) 366(9497):1640–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67663-5

20. Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr (2004) 79(3):379–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.379

21. Seo MH, Kim Y-H, Han K, Jung J-H, Park Y-G, Lee S-S, et al. Prevalence of obesity and incidence of obesity-related comorbidities in koreans based on national health insurance service health checkup data 2006–2015. J Obes Metab Syndrome (2018) 27(1):46. doi: 10.7570/jomes.2018.27.1.46

22. Collaboration OiA. Waist circumference thresholds provide an accurate and widely applicable method for the discrimination of diabetes. Diabetes Care (2007) 30(12):3116–8. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1455

23. James WPT, Jackson-Leach R, Mhurchu CN, Kalamara E, Shayeghi M, Rigby NJ, et al. Overweight and obesity (high body mass index). In: Comparative quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors, vol. 1. Geneva: World Health Organization (2004). p. 497–596.

24. Katzmarzyk P, Craig C, Bouchard C. Adiposity, adipose tissue distribution and mortality rates in the Canada fitness survey follow-up study. Int J Obes (2002) 26(8):1054–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802057

25. Dagne S, Menber Y, Petrucka P, Wassihun Y. Prevalence and associated factors of abdominal obesity among the adult population in woldia town, northeast Ethiopia, 2020: Community-based cross-sectional study. PloS One (2021) 16(3):e0247960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247960

26. Israel E, Hassen K, Markos M, Wolde K, Hawulte B. Central obesity and associated factors among urban adults in dire dawa administrative city, Eastern Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obes: Targets Ther (2022) 15:601. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S348098

27. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group* P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Internal Med (2009) 151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

28. Institute JB. JBI critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data. Adelaide: University of Adelaide (2017).

29. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol (2012) 65(9):934–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014

30. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj (1997) 315(7109):629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

32. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj (2003) 327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

33. Biadgo B, Melak T, Ambachew S, Baynes HW, Limenih MA, Jaleta KN, et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at a tertiary hospital, northwest Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Sci (2018) 28(5):645–54. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v28i5.16

34. Birarra MK, Gelayee DA. Metabolic syndrome among type 2 diabetic patients in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord (2018) 18(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12872-018-0880-7

35. Janakiraman B, Abebe SM, Chala MB, Demissie SF. Epidemiology of general, central obesity and associated cardio-metabolic risks among university employees, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obes: Targets Ther (2020) 13:343. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S235981

36. Molla MD, Wolde HF, Atnafu A. Magnitude of central obesity and its associated factors among adults in urban areas of northwest Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obes: Targets Ther (2020) 13:4169. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S279837

37. Tachebele B, Abebe M, Addis Z, Mesfin N. Metabolic syndrome among hypertensive patients at university of gondar hospital, north West Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord (2014) 14(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-177

38. Geto Z, Challa F, Lejisa T, Getahun T, Sileshi M, Nagasa B, et al. Cardiometabolic syndrome and associated factors among Ethiopian public servants, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Sci Rep (2021) 11(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99913-6

39. Kemal A, Ahmed M, Sinaga Teshome M, Abate KH. Central obesity and associated factors among adult patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) in armed force comprehensive and specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Obes (2021) 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2021/1578653

40. Solomon S, Mulugeta W. Disease burden and associated risk factors for metabolic syndrome among adults in Ethiopia. BMC Cardiovasc Disord (2019) 19(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1201-5

41. Tran A, Gelaye B, Girma B, Lemma S, Berhane Y, Bekele T, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among working adults in Ethiopia. Int J Hypertension (2011) 2011:1–8. doi: 10.4061/2011/193719

42. Yifrashewa F. Sedentary behavior and central obesity among adults working in public offices in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Institutional repository (2020).

43. Gebremariam LW, Chiang C, Yatsuya H, Hilawe EH, Kahsay AB, Godefay H, et al. Non-communicable disease risk factor profile among public employees in a regional city in northern Ethiopia. Sci Rep (2018) 8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27519-6

44. Gebremedhin Gebreegziabiher TB, Mehari K, Tamiru D. Magnitude and associated factors of metabolic syndrome among adult urban dwellers of northern Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obes: Targets Ther (2021) 14:589. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S287281

45. Gebremeskel GG, Berhe KK, Belay DS, Kidanu BH, Negash AI, Gebreslasse KT, et al. Magnitude of metabolic syndrome and its associated factors among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in ayder comprehensive specialized hospital, tigray, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes (2019) 12(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4609-1

46. Abda E, Hamza L, Tessema F, Cheneke W. Metabolic syndrome and associated factors among outpatients of jimma university teaching hospital. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obes: Targets Ther (2016) 9:47. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S97561

47. Biru B, Tamiru D, Taye A, Regassa Feyisa B. Central obesity and its predictors among adults in nekemte town, West Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med (2021) 9:20503121211054988. doi: 10.1177/20503121211054988

48. Mengesha MM, Ayele BH, Beyene AS, Roba HS. Clustering of elevated blood pressure, elevated blood glucose, and abdominal obesity among adults in dire dawa: a community-based cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obes: Targets Ther (2020) 13:2013. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S250594

49. Teshome T, Kassa DH, Hirigo AT. Prevalence and associated factors of metabolic syndrome among patients with severe mental illness at hawassa, southern-Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obes: Targets Ther (2020) 13:569. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S235379

50. Motuma A, Gobena T, Roba KT, Berhane Y, Worku A. Metabolic syndrome among working adults in eastern Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obes: Targets Ther (2020) 13:4941. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S283270

51. Prasad D, Kabir Z, Devi KR, Peter PS, Das B. Gender differences in central obesity: Implications for cardiometabolic health in south asians. Indian Heart J (2020) 72(3):202–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2020.04.008

52. Tulp OL, Obidi OF, Oyesile TC, Einstein GP. The prevalence of adult obesity in Africa: A meta-analysis. Gene Rep (2018) 11:124–6. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2018.03.006

53. Harbuwono DS, Pramono LA, Yunir E, Subekti I. Obesity and central obesity in Indonesia: evidence from a national health survey. Med J Indonesia (2018) 27(2):114–20. doi: 10.13181/mji.v27i2.1512

54. Wong M, Huang J, Wang J, Chan PS, Lok V, Chen X, et al. Global, regional and time-trend prevalence of central obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13.2 million subjects. Eur J Epidemiol (2020) 35(7):673–83. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00650-3

55. Bashir M, Yahaya A, Muhammad M, Yusuf A, Mukhtar I. Prevalence of central obesity in Nigeria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health (2022) 206:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2022.02.020

56. Wang H, Wang J, Liu M-M, Wang D, Liu Y-Q, Zhao Y, et al. Epidemiology of general obesity, abdominal obesity and related risk factors in urban adults from 33 communities of northeast China: the CHPSNE study. BMC Public Health (2012) 12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-967

57. Cisse K, Samadoulougou S, Ouedraogo M, Kouanda S, Kirakoya-Samadoulougou F. Prevalence of abdominal obesity and its association with cardiovascular risk among the adult population in Burkina Faso: findings from a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMJ Open (2021) 11(7):e049496. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049496

58. Owolabi EO, Ter Goon D, Adeniyi OV. Central obesity and normal-weight central obesity among adults attending healthcare facilities in buffalo city metropolitan municipality, south Africa: a cross-sectional study. J Health Population Nutr (2017) 36(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s41043-017-0133-x

59. Yoon YS, Oh SW, Park HS. Socioeconomic status in relation to obesity and abdominal obesity in Korean adults: a focus on sex differences. Obesity (2006) 14(5):909–19. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.105

60. Bell AC, Ge K, Popkin BM. The road to obesity or the path to prevention: motorized transportation and obesity in China. Obes Res (2002) 10(4):277–83. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.38

61. Pradeepa R, Anjana RM, Joshi SR, Bhansali A, Deepa M, Joshi PP, et al. Prevalence of generalized & abdominal obesity in urban & rural India-the ICMR-INDIAB study (Phase-I)[ICMR-INDIAB-3]. Indian J Med Res (2015) 142(2):139. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.164234

62. Stokes A, Collins JM, Grant BF, Hsiao CW, Johnston SS, Ammann EM, et al. Prevalence and determinants of engagement with obesity care in the united states. Obesity (2018) 26(5):814–8. doi: 10.1002/oby.22173

63. Aranceta-Bartrina J, Pérez-Rodrigo C, Alberdi-Aresti G, Ramos-Carrera N, Lázaro-Masedo S. Prevalence of general obesity and abdominal obesity in the Spanish adult population (aged 25–64 years) 2014–2015: the ENPE study. Rev Española Cardiologia (English Edition) (2016) 69(6):579–87. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2016.02.009

64. Okosun IS, Choi ST, Boltri JM, Parish DC, Chandra KD, Dever GA, et al. Trends of abdominal adiposity in white, black, and Mexican-American adults, 1988 to 2000. Obes Res (2003) 11(8):1010–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.139

65. Al-Lawati JA, Mohammed AJ, Al-Hinai HQ, Jousilahti P. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among omani adults. Diabetes Care (2003) 26(6):1781–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1781

66. Azizi F, Salehi P, Etemadi A, Zahedi-Asl S. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an urban population: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2003) 61(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(03)00066-4

67. Haffner SM, Mykkänen L, Valdez RA, Katz MS. Relationship of sex hormones to lipids and lipoproteins in nondiabetic men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1993) 77(6):1610–5.doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.6.8263149

68. Laaksonen DE, Niskanen L, Punnonen K, Nyyssonen K, Tuomainen T-P, Salonen R, et al. Sex hormones, inflammation and the metabolic syndrome: a population-based study. Eur J Endocrinol (2003) 149(6):601–8. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1490601

69. Schunkert H, Hense H-W, Andus T, Riegger GA, Straub RH. Relation between dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and blood pressure levels in a population-based sample. Am J Hypertension (1999) 12(11):1140–3. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(99)00128-4

70. Slawik M, Vidal-Puig AJ. Lipotoxicity, overnutrition and energy metabolism in aging. Ageing Res Rev (2006) 5(2):144–64. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2006.03.004

71. Ravishankar A. Is India shouldering a double burden of malnutrition? J Health Manage (2012) 14(3):313–28. doi: 10.1177/0972063412457513

72. Chen X, Jiang Y, Wang L, Li Y, Zhang M, Hu N, et al. Leisure-time physical activity and sedentary behaviors among Chinese adults in 2010. Zhonghua yu Fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese J Prev Medicine] (2012) 46(5):399–403. doi: 10.3760/cma.J.issn.0253-9624.2012.05.005

Keywords: prevalence, central obesity, associated factors, meta-analysis, Ethiopia

Citation: Tegegne KD, Wagaw GB, Gebeyehu NA, Yirdaw LT, Shewangashaw NE, Mekonen NA and Kassaw MW (2022) Prevalence of central obesity and associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 13:983180. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.983180

Received: 30 June 2022; Accepted: 12 August 2022;

Published: 30 August 2022.

Edited by:

Josep A. Tur, University of the Balearic Islands, SpainReviewed by:

Esther López-Bayghen, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Avanzados (CINVESTAV)(IPN), MexicoCopyright © 2022 Tegegne, Wagaw, Gebeyehu, Yirdaw, Shewangashaw, Mekonen and Kassaw. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kirubel Dagnaw Tegegne, a2lydWJlbGRhZ25hd0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.