- Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, Qingdao Municipal Hospital, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China

Background: Expectant observation and aggressive surgery are both recommended for small nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NF-PanNETs). However, the optimal management of small NF-PanNETs remains disputable due to the heterogeneous clinical behavior.

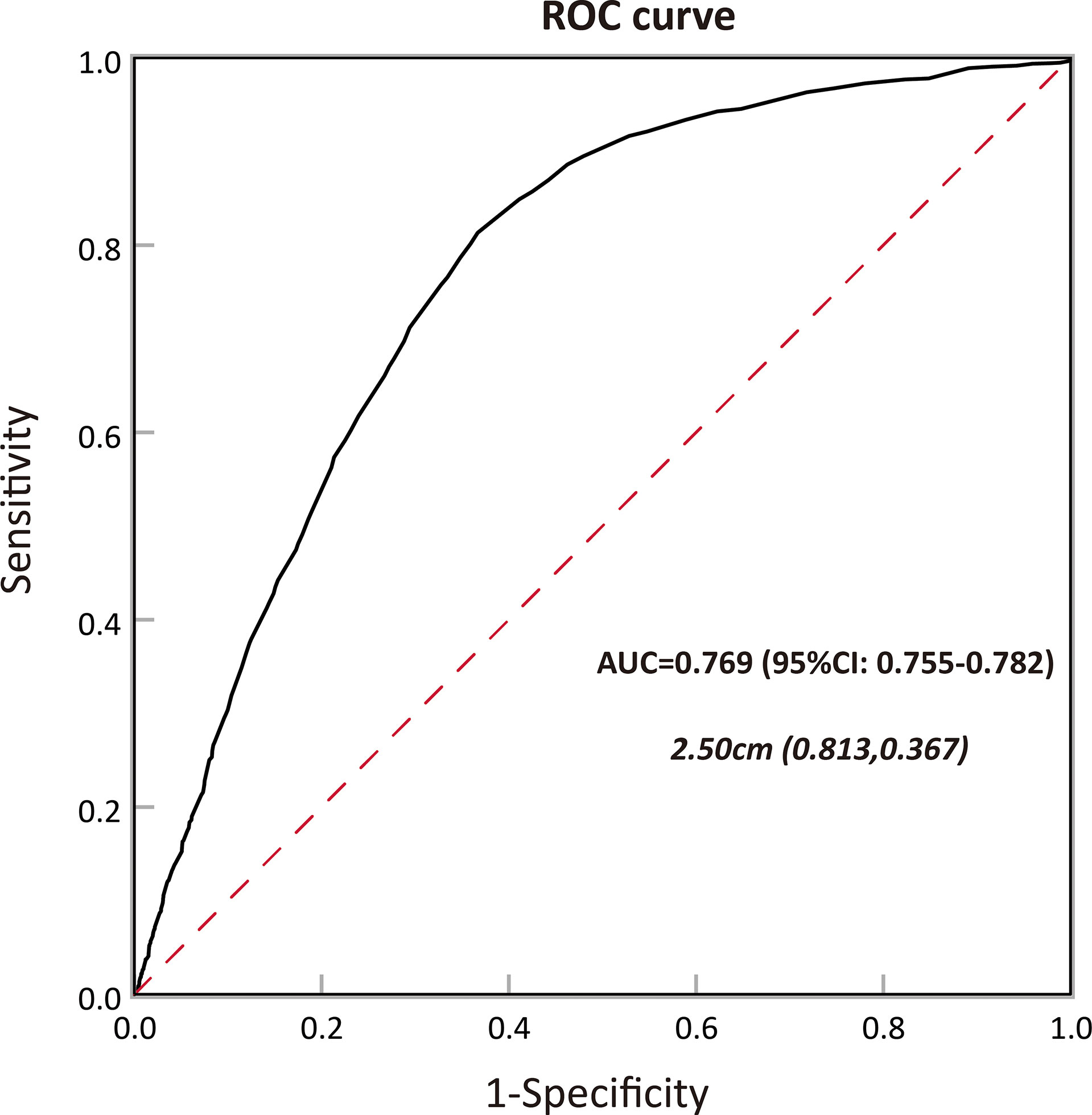

Methods: Patients who were diagnosed with pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs) between 2000 and 2018 were identified from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database and reviewed retrospectively. Tumor aggressiveness was defined as poor differentiation, lymph node involvement, liver involvement, and advanced stage. The best cutoff of tumor size associated with tumor aggressiveness was determined through the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify prognostic factors in patients with tumors of ≤2 cm.

Results: A total of 5,172 patients with PanNENs were enrolled, including 1,760 (34.0%) tumors ≤2 cm and 3,412 (66.0%) tumors >2 cm. A 2.5-cm cutoff size was found to be associated with a satisfactory ability in predicting tumor aggressiveness. On multivariate analysis, age, gender, ethnicity, tumor grade, tumor number, and stage were independent prognostic factors for overall survival (OS) in patients with tumors less than or equal to 2 cm in size. A total of 1,621 patients were diagnosed with NF-PanNETs according to the WHO classification, of whom 1,350 underwent surgery, 271 performed active observation. The OS was significantly better in the surgery group compared to the observation group regardless of propensity score analysis. Additionally, a total of 407 patients were selected based on the multivariate Cox regression analysis, of whom 46 underwent observation, 361 underwent surgery, and the OS was comparable.

Conclusion: Expectant observation may be a reasonable alternative to aggressive surgical resection in highly selected small NF-PanNET patients. Also, the decision to observe versus surgery should not only be based on tumor size alone but also take into account other important clinicopathological factors.

Introduction

Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs) are among the heterogeneous group of neoplasms with the most rapidly increasing incidence recently (1, 2). This increase is largely attributed to the advances in diagnostic techniques, including computed tomography and endoscopy. Unlike pancreatic adenocarcinoma, the vast majority of PanNENs are considered clinically indolent diseases and associated with favorable prognoses (3, 4). Clinically, PanNENs are classified into functional and nonfunctional diseases. Different from functional PanNENs (F-PanNENs) that are combined with syndromes of hormone hypersecretion, nonfunctional PanNENs (NF-PanNENs) are not accompanied by clinically significant hormonal symptoms. With the wide use of cross-sectional imaging, a sizable fraction of patients are incidentally diagnosed with small, asymptomatic NF-PanNENs. To date, the natural history is, however, not well described. According to the WHO classification, PanNENs are classified into well-differentiated, low-to-intermediate-grade pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs) and poorly differentiated, high-grade pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas (PanNECs) (5, 6). The management of F-PanNETs has less controversies, while the treatment of NF-PanNETs, especially for tumors less than or equal to 2 cm in size, remains disputable (7–9). Incidentally diagnosed NF-PanNETs generally exhibit benign behaviors, making them suitable and feasible to undergo surveillance according to some guidelines. In addition, radical treatments such as pancreatectomy may carry a high risk of developing postoperative complications. However, there are limited data examining the safety of this conservative policy. Also, some studies found that NF-PanNETs are inclined to have lymph node involvement, which may compromise the survival results in patients who conduct a “wait-to-see” strategy (10, 11). In terms of the potential risks and uncertain benefits of the observation strategy, the recommendation for its use should be interpreted with caution.

Therefore, the purpose of the study was to identify the association between tumor size and aggressive behaviors in NF-PanNET patients as well as to compare the long-term survival outcomes between close observational monitoring and aggressive surgical resection among patients with NF-PanNETs ≤2 cm. In addition, we attempted to identify patients who were potential candidates for an observational treatment based on a large population database from the United States.

Patients and Methods

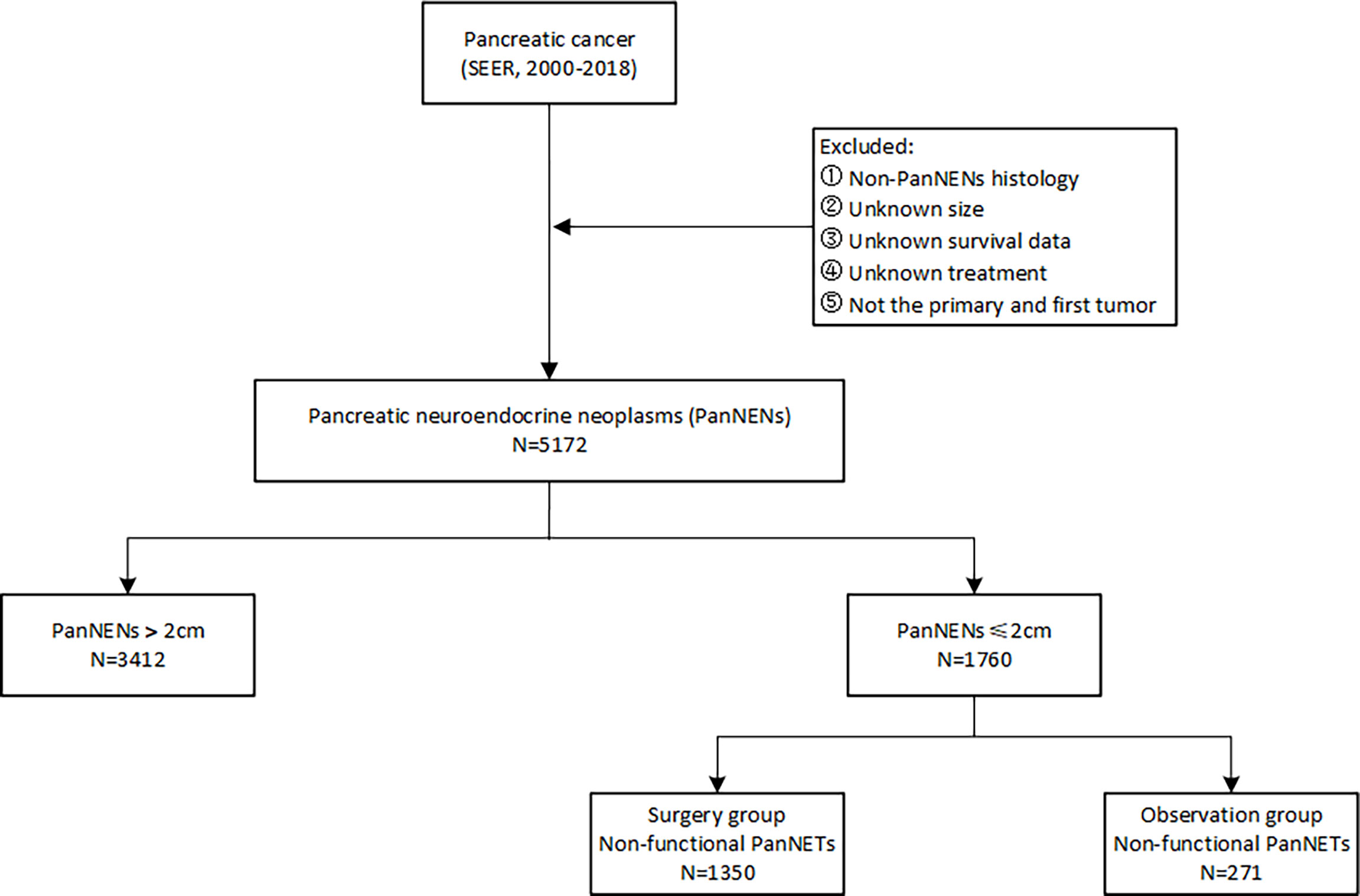

In this retrospective study, patients diagnosed with PanNENs between 2000 and 2018 were identified from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database. The evaluated variables included age at diagnosis, gender, year of diagnosis, ethnicity, marital status, tumor characteristics, functionality, treatment, and survival outcomes. The inclusion criteria for PanNENs based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3) were as follows: primary sites C25.0 to C25.9 with histological codes 8150, 8151, 8152, 8153, 8155, 8156, 8240, 8241, 8242, 8243, 8245, 8246, and 8249. Patients with unknown information on vital status and survival duration were excluded. The workflow of patient selection for this study is detailed in Figure 1. The long-term survival outcomes were compared between the observation and surgery cohorts by evaluating the overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) before and after propensity score matching.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software and SPSS with a two-sided significance level of 0.05. The categorical variables were presented as numbers (percentage) and were assessed between groups with the Chi-square (χ²) test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range) and were compared using the Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Multivariate analysis examining who was more likely to perform surgery was conducted using predictive factors statistically significant to univariate analysis. Furthermore, Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to determine the prognostic variables in patients with tumors ≤2 cm. A propensity score matching (PSM) method using a logistic regression model was utilized to reduce the selection biases and balance confounding factors. In addition, an optimal cutoff value of tumor size for predicting tumor aggressiveness was defined as poor differentiation, lymph node involvement, liver involvement, and advanced stage using the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) method. Survival results were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test between groups. In order to evaluate the efficacy of expectant observation in NF-PanNETs with less than or equal to 2 cm in size, OS and CSS rates were compared between observation and aggressive surgical resection cohorts before and after PSM.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

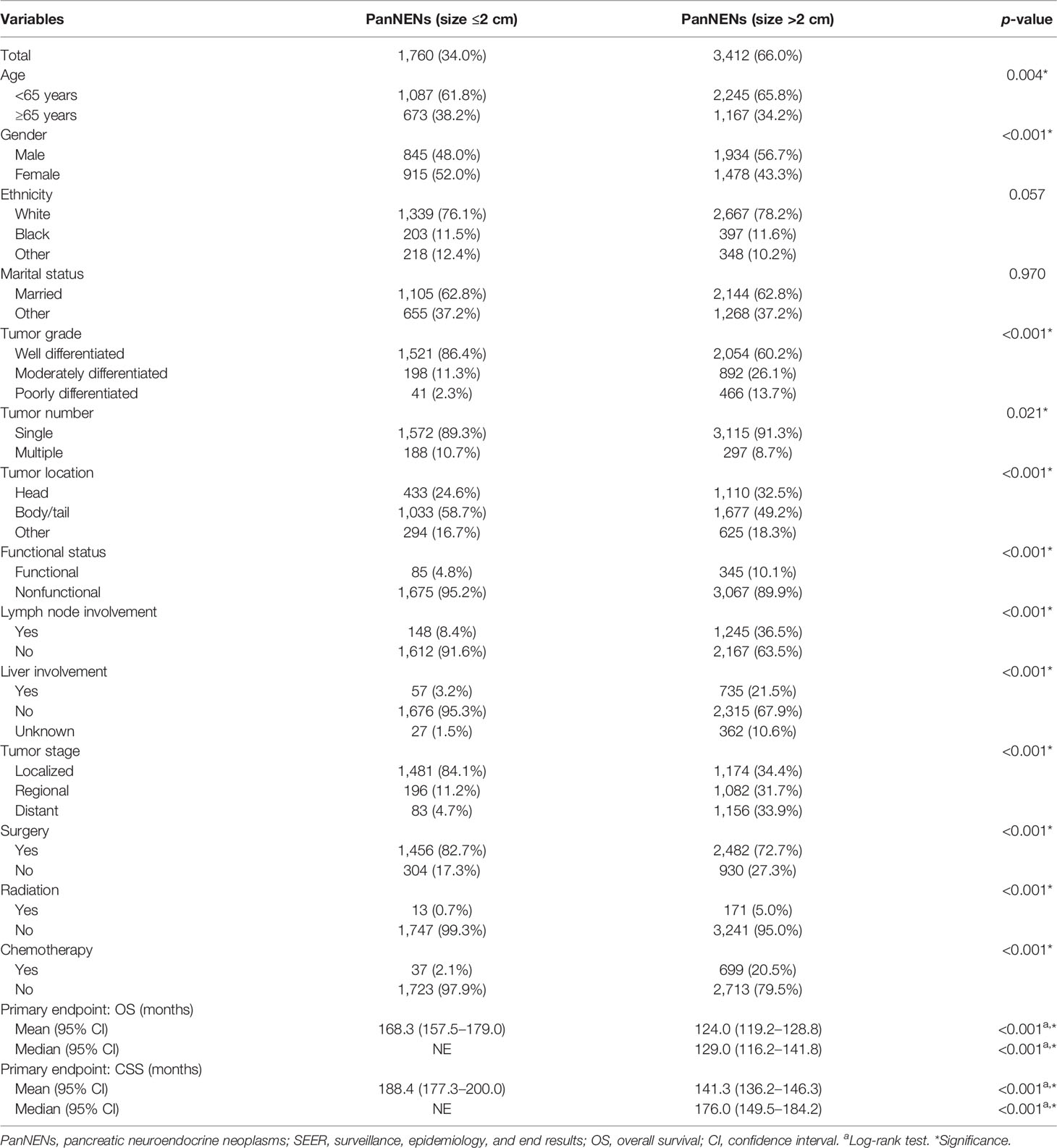

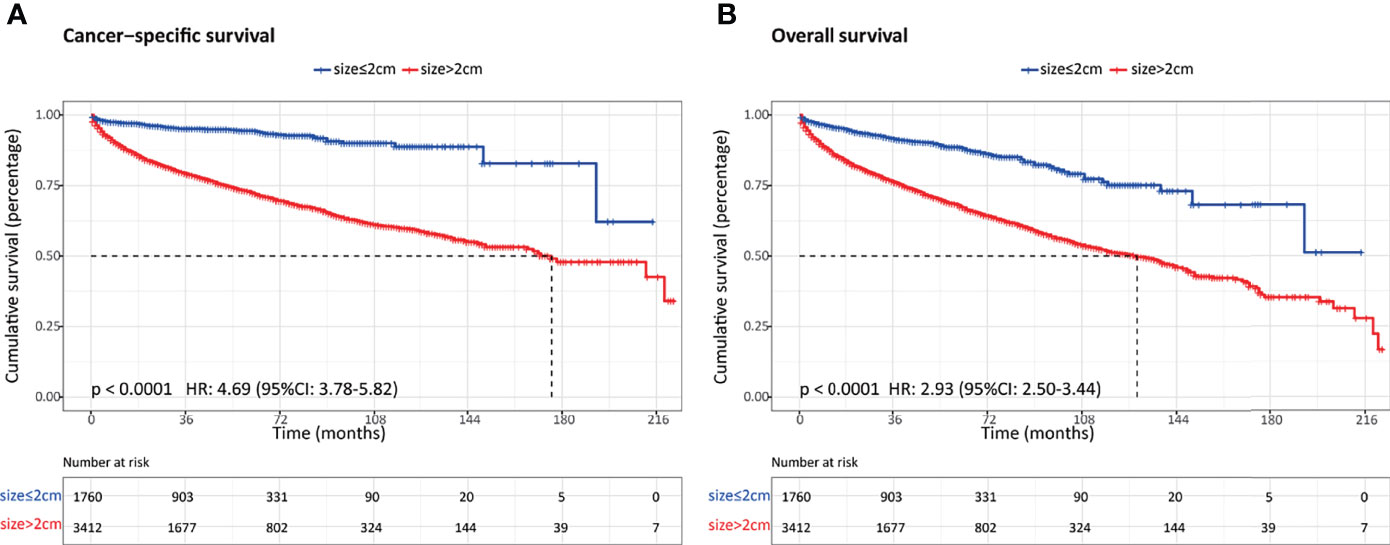

Overall, a total of 5,172 patients with PanNENs between 2001 and 2018 were identified from the SEER database, including 1,760 (34.0%) tumors ≤2 cm and 3,412 (66.0%) tumors >2 cm. Among the cohort with PanNENs ≤2 cm, a vast majority of patients were white (76.1%), married (62.8%), younger than 65 years old (61.8%), well-differentiated (86.4%), and had the loco-regional disease at diagnosis (95.3%). Of note, about 82.7% of these neoplasms were surgically resected while only 0.7% received radiation and 2.1% received chemotherapy. As for patients with tumors larger than 2 cm, the baseline characteristics were significantly different from those with tumors ≤2 cm. Patients with PanNENs >2 cm presented with a more advanced tumor burden, including higher proportions of poor differentiation, lymph node involvement, liver involvement, and late tumor stage. Additionally, the rate of surgical treatment was significantly lower compared to that in patients with PanNENs ≤2 cm. The more detailed clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Kaplan–Meier curves revealed that PanNENs >2 cm were associated with worse survival outcomes than PanNENs ≤2 cm (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Comparison of survival outcomes between patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs) ≤2 cm and PanNENs >2 cm. (A) Cancer-specific survival. (B) Overall survival.

Predictor of Aggressive Behavior: Role of Tumor Size

In order to determine the association between tumor size and aggressive behavior, the predictive ability of preoperative size in the subset of NF-PanNENs was evaluated using the ROC method. In our study, tumor aggressiveness was defined as poor tumor differentiation, lymph node involvement, liver involvement, and advanced tumor stage. In receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, tumor size resulted in an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.769 (95% CI, 0.755–0.782), showing a satisfactory ability to predict aggressiveness in patients with NF-PanNENs. The optimum tumor size cutoff value distinguishing tumor aggressiveness was 2.50 cm, resulting in 81.3% sensitivity and 63.3% specificity (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Calculation of the cutoff value for tumor size in predicting tumor aggressiveness among patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs) by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and the area under the curve (AUC).

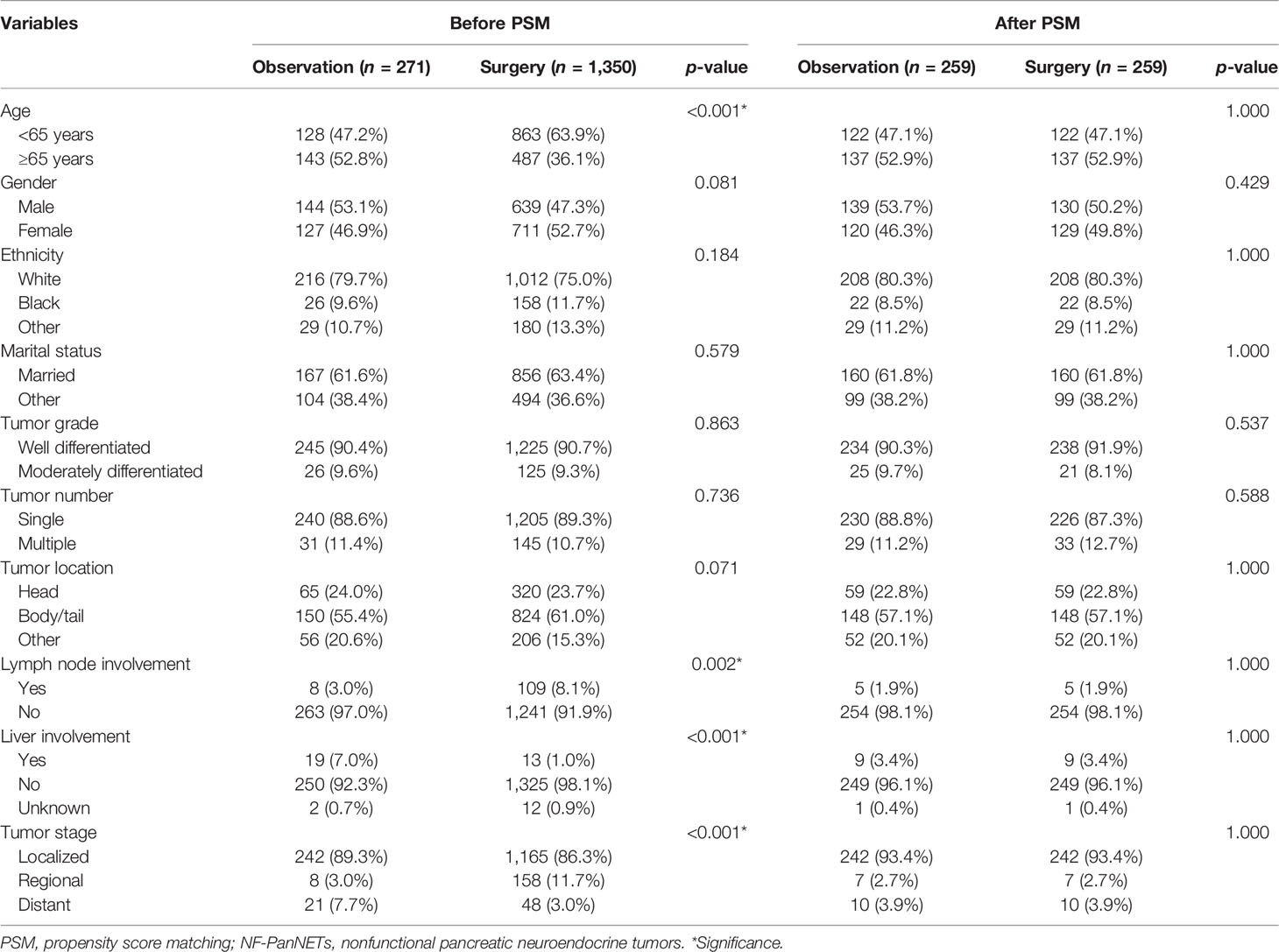

Characteristics of NF-PanNETs ≤2 cm Between Observation and Surgery Cohorts

Among the 5,172 patients with PanNENs enrolled in the SEER database, 1,621 patients were diagnosed with NF-PanNETs according to the WHO classification, of whom 1,350 underwent surgery and 271 performed a conservative treatment. Baseline demographics and clinicopathologic features were displayed in Table 2. As shown in the table, age at diagnosis, the rates of lymph node involvement and liver involvement, as well as tumor stage were significantly different between these two cohorts. In the surgery cohort, patients were more frequently presented with lymph node involvement and loco-regional disease.

Table 2 Comparison of baseline characteristics before and after PSM in patients with NF-PanNETs ≤2 cm.

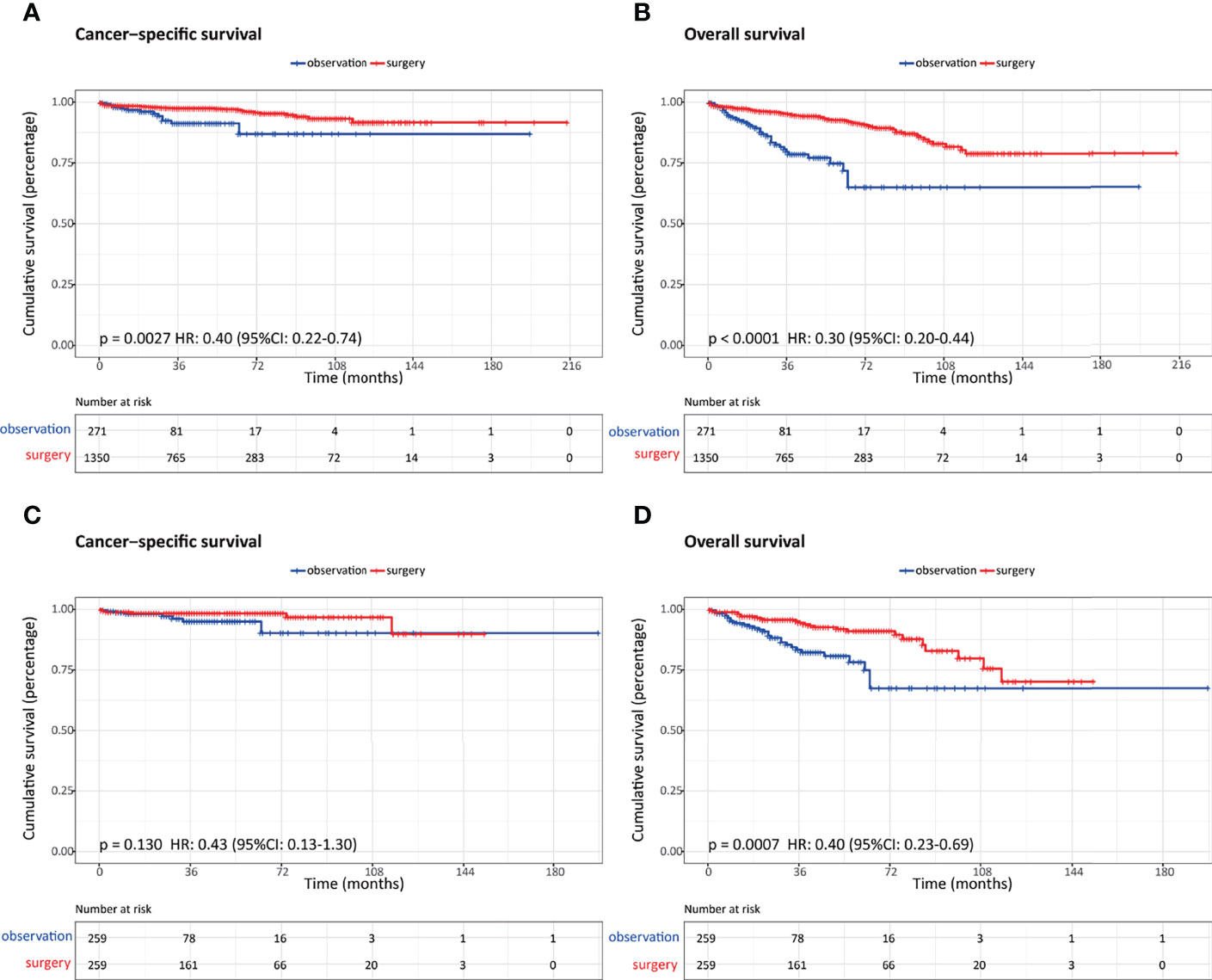

Comparison of Survival Outcomes After Propensity Score Matching

After PSM, 259 patients were matched in each cohort, and the baseline characteristics were well-balanced (Table 2). With regard to survival results, the overall survival was significantly better in patients who underwent surgery regardless of the propensity score analysis. While the cancer-specific survival was comparable between these two groups after propensity score matching (Figure 4.)

Figure 4 Comparison of survival outcomes in patients with nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (NF-PanNENs) ≤2 cm who underwent observation and surgery before and after propensity score matching (PSM). (A) Cancer-specific survival before PSM. (B) Overall survival before PSM. (C) Cancer-specific survival after PSM. (D) Overall survival after PSM.

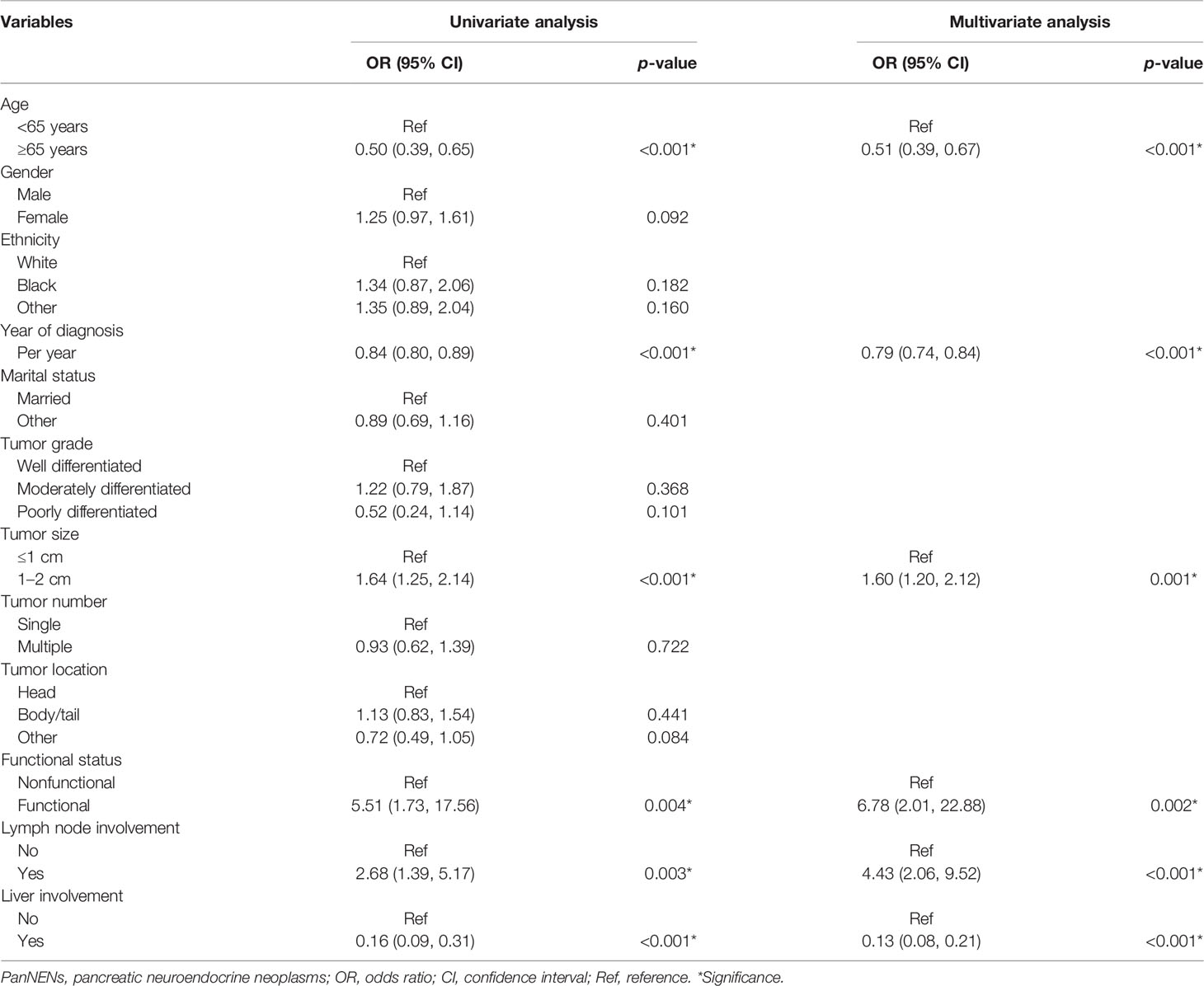

Factors Associated With Patients With NF-PanNENs Who Underwent Surgery

On univariate logistic regression analysis, age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, tumor size, functional status, lymph node status, liver involvement, and tumor stage were associated with patients who were more likely to receive surgical treatment. In multivariate analysis, diagnosis at early year, age (<65 years), size 1–2 cm, functional tumors, lymph node involvement, and liver involvement were significant predictors for patients treated with surgery (Table 3).

Table 3 Factors associated with patients with PanNENs ≤2 cm who underwent surgery in the SEER database.

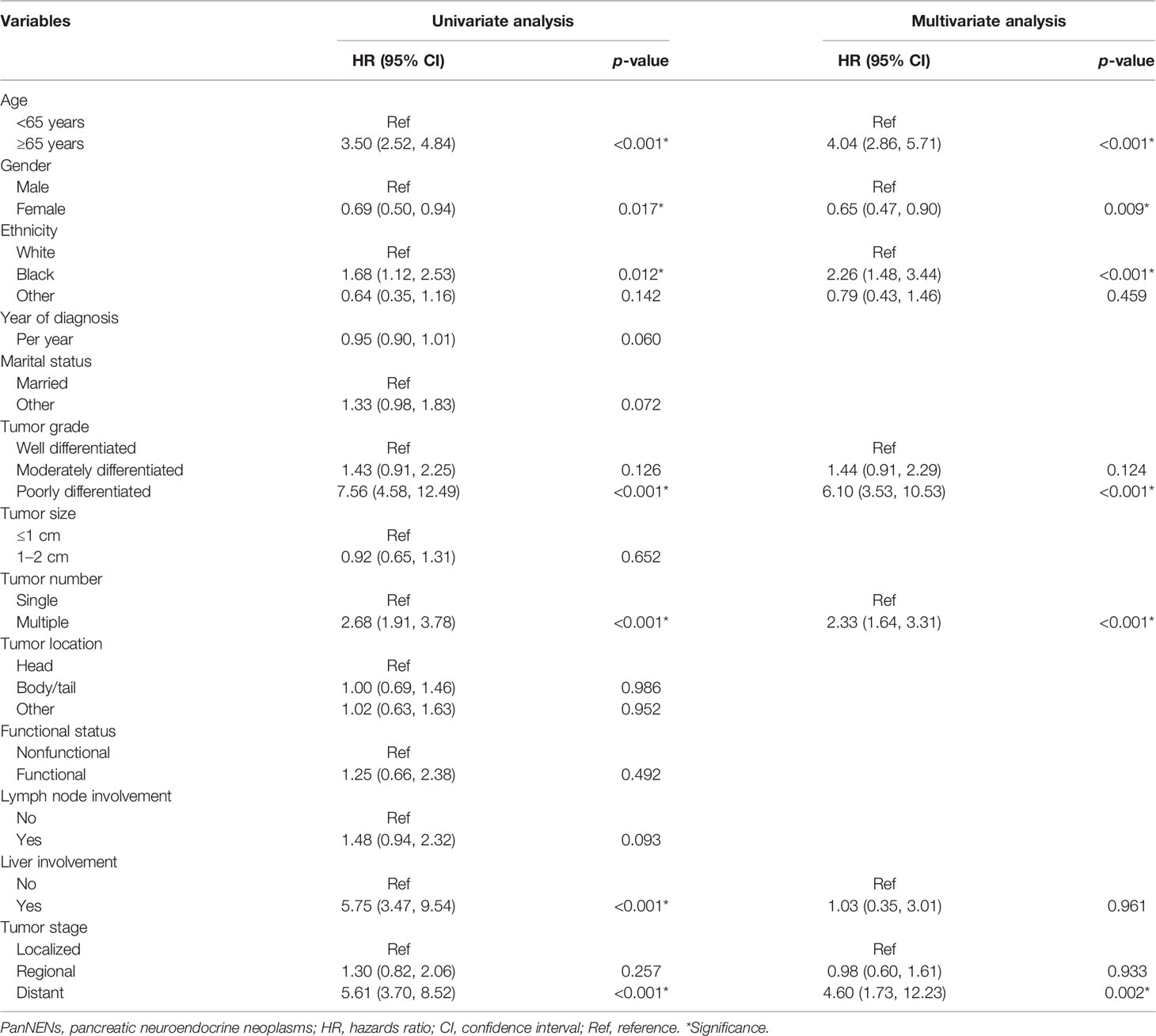

Analysis of Risk Factors for OS in Patients With PanNENs ≤2 cm

The estimated OS rates at 3, 5, and 10 years were 92.3%, 89.2%, and 75.6%, respectively, while the estimated CSS probabilities at 3, 5, and 10 years were 95.8%, 95.0%, and 89.6%, respectively. On multivariate analysis, age, gender, ethnicity, tumor grade, tumor number, and tumor stage were independent prognostic factors for OS in patients with small-sized PanNENs (Table 4).

Exploratory Analyses

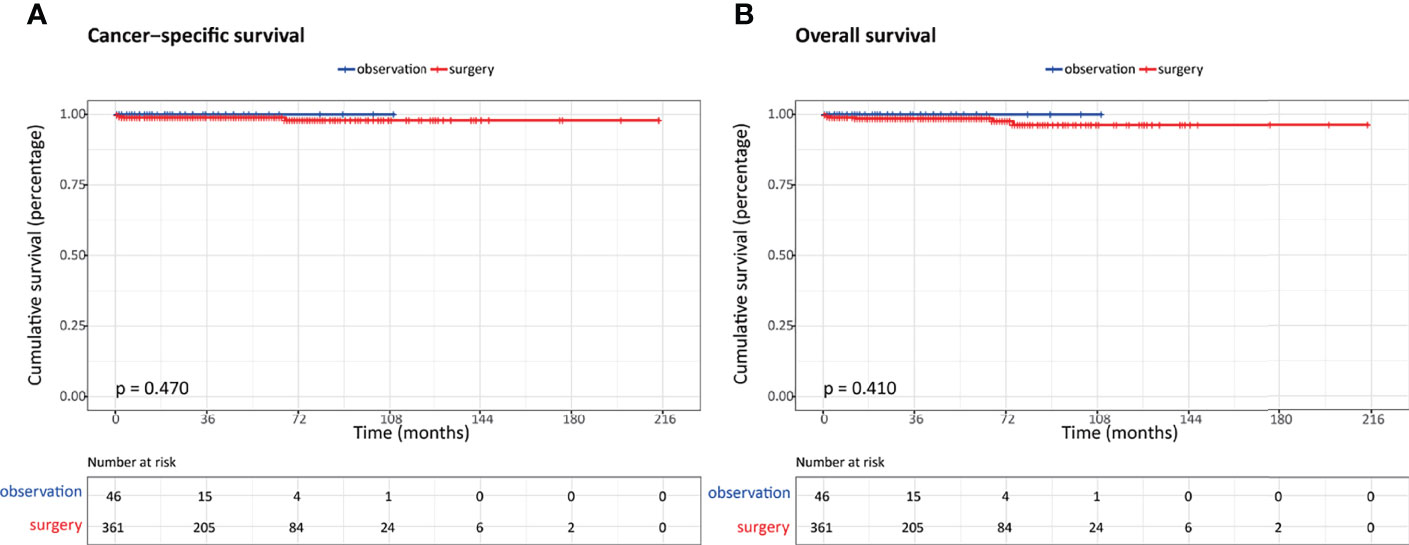

In order to better define the appropriate indications for nonoperative management, we selected a cohort of patients based on the results of a multivariate survival analysis. Overall, a total of 407 patients were identified, of whom 46 underwent observation and 361 underwent aggressive surgery. In addition, the OS and CSS were comparable between these two groups (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Comparison of survival outcomes in patients with highly selected nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (NF-PanNENs) ≤2 cm between observation and surgery cohorts after propensity score matching (PSM). (A) Cancer-specific survival. (B) Overall survival.

Discussion

Our study provides a comprehensive characterization of PanNENs and NF-PanNETs based on a large cohort of the population from the United States. Generally, the choice between observation and aggressive surgery should be on the basis of an accurate estimate of the malignant potential. However, our results indicate that using a 2-cm cutoff size alone to guide treatment decisions does not seem to be appropriate and safe. Surgery was found to be associated with survival advantages in patients with NF-PanNETs ≤2 cm compared to observation regardless of PSM analysis. Instead, patients with NF-PanNENs who were younger than 65 years old, of the female sex, white or other ethnicities rather than black, low-to-intermediate grade, with single tumor, and loco-regional stage were the suitable candidates for active surveillance.

The optimal management of NF-PanNETs less than or equal to 2 cm in size represented an unsolved clinical challenge in recent years, especially with the steadily increasing incidence of these incidentally discovered tumors. Lacking adequately powered studies investigating their clinical features and identifying the prognostic factors, indications for expectant observation in treating small tumors remain ambiguous and inconsistent. A preoperative tumor size had been proposed to predict the malignant potential and help in clinical decision-making (12, 13). Some consensus recommendations suggest that observation can be considered an option due to the clinically indolent and benign course of tumors less than or equal to 2 cm. Both the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) Consensus Guidelines and NCCN guidelines offer an active surveillance strategy for patients with low-grade tumors measuring less than 2 cm in size, with a comprehensive assessment of the individual patient characteristics (14, 15). Lee et al. retrospectively reviewed 133 incidentally detected, small NF-PanNETs patients (77 nonoperative, 56 operatives), and they found that nonoperative treatment may be advocated as these tumors commonly showed minimal or no growth during follow-up (16). In a matched case-control study, Ssdot et al. analyzed the natural history of small (<3 cm), asymptomatic PanNETs and evaluated the efficacy of surgical resection versus observation. Among the patients who were initially observed, none of them developed distant metastases or died, with a median follow-up of 44 months (17). Similarly, Barenboim et al. identified 44 small asymptomatic NF-PanNETs treated with expectant observation between 2001 and 2018 and reported that no patients presented with regional or systemic disease progression or cancer-related death after a follow-up of 52.8 months. Considering the potential risks of preoperative morbidity and mortality, a strategy of conservative management seemed to be acceptable in selected patients (18). A systematic review including 5 retrospective literatures with 540 asymptomatic, small NF-PanNENs was conducted to evaluate the outcome between active surveillance with surgery. During the follow-up, the observation group did not occur disease-related deaths; therefore, they concluded that expectant management may be a reasonable alternative to aggressive surgery in highly selected patients (19). However, other studies have questioned the safety and feasibility of a conservative strategy and demonstrated that NF-PanNETs were associated with small but measurable malignant potential and aggressive surgical resection could provide long-term survival benefits (11). Gratian et al. found that 3 of 56 NF-PanNETs with tumors less than 2 cm developed metastatic disease and 2 of them died. In addition, tumor size was not related to distant metastasis or survival outcomes, which implied that it should not be used as an indication for treatment decisions (20). In a retrospective study including 3,243 cases with early-stage PanNETs ≤2 cm selected from the National Cancer Database, Chivukula et al. demonstrated a survival benefit of surgical resection for tumors 1 to 2 cm in size (21). Overall, the dilemma in managing patients with NF-PNETs ≤2 cm results from the benefits of surgery, which need to be weighed against the risks of possible disease progression, surgery-related morbidity, and comorbidities.

Generally, tumor differentiation based on the WHO classification and the AJCC staging system were regarded as two main determinants in the selection of optimal management for patients with PanNETs. While both of these two elements were not easily obtained before surgery, the preoperatively available clinical variable, tumor size, was frequently used to predict the tumor metastatic progression and aid clinical decision-making. However, as NF-PanNETs are a heterogeneous group of entities that exhibit a broad spectrum of biological behavior, there is no clear cutoff for benign disease. The current study demonstrates that tumor size alone cannot differentiate whether patients with NF-PNETs less than 2 cm are the appropriate candidates for an expectant observation, and other preoperatively available clinical features need to be taken into account as well, such as individual patient characteristics, comorbidities, and other risk factors for survival. In our study, a number of clinicopathological variables were identified to be associated with overall survival in NF-PanNENs ≤2 cm, including age, gender, ethnicity, tumor grade, tumor number, and tumor stage. Therefore, when considering the clinical factors that may inform the decision to perform observation or surgical resection, tumor size and these risk factors should act as a marker for the clinicians.

Our study had several limitations. The inherent biases with a retrospective design could not be completely eliminated even though we used propensity score matching. Secondly, the lack of important data in the SEER database may fail to incorporate some recognized prognostic parameters, such as the Ki-67 index and surgery-related complications. Last, the small size of patients after propensity score matching may therefore limit the generalization of the results.

In conclusion, expectant observation of small NF-PanNETs may be a reasonable alternative to aggressive surgical resection in highly selected patients. Also, the decision to observe versus surgery should not only be based on tumor size alone but also take into account other important clinicopathological factors. Further prospective multicentric studies and robust data are required to validate the benefit of this conservative policy.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: https://seer.cancer.gov/.

Author Contributions

GS contributed to the conception and designed the study. ZY drafted the manuscript. DZ conducted the statistical analysis. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Orditura M, Petrillo A, Ventriglia J, Diana A, Laterza MM, Fabozzi A, et al. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Nosography, Management and Treatment. Int J Surg (2016) 28 (Suppl 1):S156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.12.052

2. Halfdanarson TR, Rabe KG, Rubin J, Petersen GM. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PNETs): Incidence, Prognosis and Recent Trend Toward Improved Survival. Ann Oncol (2008) 19(10):1727–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn351

3. Guilmette JM, Nosé V. Neoplasms of the Neuroendocrine Pancreas: An Update in the Classification, Definition, and Molecular Genetic Advances. Adv Anat Pathol (2019) 26(1):13–30. doi: 10.1097/pap.0000000000000201

4. Khanna L, Prasad SR, Sunnapwar A, et al. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: 2020 Update on Pathologic and Imaging Findings and Classification. Radiographics (2020) 40(5):1240–62. doi: 10.1148/rg.2020200025

5. Choe J, Kim KW, Kim HJ, Kim DW, Kim KP, Hong SM, et al. What Is New in the 2017 World Health Organization Classification and 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms? Korean J Radiol (2019) 20(1):5–17. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.0040

6. Fang JM, Shi J. A Clinicopathologic and Molecular Update of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms With a Focus on the New World Health Organization Classification. Arch Pathol Lab Med (2019) 143(11):1317–26. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2019-0338-RA

7. Mpilla GB, Philip PA, El-Rayes B, Azmi AS. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Therapeutic Challenges and Research Limitations. World J Gastroenterol (2020) 26(28):4036–54. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i28.4036

8. Clancy TE. Surgical Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am (2016) 30(1):103–18. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.09.004

9. Hain E, Sindayigaya R, Fawaz J, Gharios J, Bouteloup G, Soyer P, et al. Surgical Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: An Introduction. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther (2019) 19(12):1089–100. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2019.1703677

10. Finkelstein P, Sharma R, Picado O, Gadde R, Stuart H, Ripat C, et al. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (panNETs): Analysis of Overall Survival of Nonsurgical Management Versus Surgical Resection. J Gastrointest Surg (2017) 21(5):855–66. doi: 10.1007/s11605-017-3365-6

11. Vega EA, Kutlu OC, Alarcon SV, Salehi O, Kazakova V, Kozyreva O, et al. Clinical Prognosticators of Metastatic Potential in Patients With Small Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. J Gastrointest Surg (2021) 25(10):2593–9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-021-04946-x

12. Bettini R, Partelli S, Boninsegna L, Capelli P, Crippa S, Pederzoli P, et al. Tumor Size Correlates With Malignancy in Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Endocrine Tumor. Surgery (2011) 150(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.02.022

13. Partelli S, Muffatti F, Rancoita PMV, Andreasi V, Balzano G, Crippa S, et al. The Size of Well Differentiated Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Correlates With Ki67 Proliferative Index and is Not Associated With Age. Dig Liver Dis (2019) 51(5):735–40. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2019.01.008

14. Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, Bartsch DK, Capdevila J, Caplin M, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Patients With Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Non-Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology (2016) 103(2):153–71. doi: 10.1159/000443171

15. Tempero MA. NCCN Guidelines Updates: Pancreatic Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw (2019) 17(5.5):603–5. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.5007

16. Lee LC, Grant CS, Salomao DR, Fletcher JG, Takahashi N, Fidler JL, et al. Small, Nonfunctioning, Asymptomatic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PNETs): Role for Nonoperative Management. Surgery (2012) 152(6):965–74. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.08.038

17. Sadot E, Reidy-Lagunes DL, Tang LH, Do RK, Gonen M, D'Angelica MI, et al. Observation Versus Resection for Small Asymptomatic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Matched Case-Control Study. Ann Surg Oncol (2016) 23(4):1361–70. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4986-1

18. Barenboim A, Lahat G, Nachmany I, Nakache R, Goykhman Y, Geva R, et al. Resection Versus Observation of Small Asymptomatic Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. J Gastrointest Surg (2020) 24(6):1366–74. doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04285-y

19. Partelli S, Cirocchi R, Crippa S, Cardinali L, Fendrich V, Bartsch DK, et al. Systematic Review of Active Surveillance Versus Surgical Management of Asymptomatic Small non-Functioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Br J Surg (2017) 104(1):34–41. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10312

20. Cherenfant J, Stocker SJ, Gage MK, Du H, Thurow TA, Odeleye M, et al. Predicting Aggressive Behavior in Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Surgery (2013) 154(4):785–791; discussion 791-783. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.07.004

Keywords: pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, observation, surgery, tumor size, survival

Citation: Yang Z, Zhang D and Shi G (2022) Reappraisal of a 2-cm Cutoff Size for the Management of Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Population-Based Study. Front. Endocrinol. 13:928341. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.928341

Received: 25 April 2022; Accepted: 31 May 2022;

Published: 18 July 2022.

Edited by:

Antongiulio Faggiano, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Yang, Zhang and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guangjun Shi, c2dqenBAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=

Zhen Yang

Zhen Yang Dongsheng Zhang

Dongsheng Zhang