95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Endocrinol. , 16 November 2021

Sec. Endocrinology of Aging

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.739257

Background: Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a transitional state between normal elderly people and dementia, with a higher risk of dementia transition. The primary purpose of the current study was to investigate whether routine blood and blood biochemical markers could be used to predict the onset of MCI.

Methods: Data was obtained from the cohort study on brain health of the elderly in Shanghai. A total of 1015 community elders were included in the current study. Based on clinical evaluation and the scores of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), these participants were divided into the MCI (n=444) and cognitively normal groups (n=571). Then we tested their fasting blood routine and blood biochemical indexes, and collected their general demographic data by using a standard questionnaire.

Results: By using binary logistic regression analysis and the ROC curve, we found that elevated fasting plasma glucose (p=0.025, OR=1.118, OR=1.014-1.233) was a risk factor for MCI.

Conclusions: Elevated fasting blood glucose may be a risk factor for mild cognitive impairment, but the above conclusions need to be verified by longitudinal studies.

The term of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was introduced in the late 1980s by Reisberg and colleagues, which represents a state of cognitive function between normal aging and dementia (1). Individuals with MCI often complain about their memory and show mild cognitive deficits on objective cognitive tests, but their cognitive impairment is not severe enough to qualify for dementia (2). However, these MCI individuals (10%-15%) generally have a ten-fold greater risk of progression to dementia than the general population (1-2%), suggesting that MCI is a prodrome stage of dementia (3). Although dementia is irreversible, MCI can be reversed to normal or maintained in a relatively stable state for a long time. Therefore, early identification of risk or protective factors affecting the progression of MCI is extremely important (4).

Previous studies have shown that depression, sex, years after menopause, daily vegetable intake, hormonal replacement, and hypertension can promote the transition from normal elderly to MCI (5–8). Similarly, certain indicators in blood also have a predictive effect. For example, Bingying Du et al. found that the ratio of glycogen Synthase Kinase (GSK)-3β to brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) was strongly related to MCI (9). Simon J Furney et al. found that biochemical markers of inflammation were better predictors of MCI conversion than APOE genotype or clinical measures (10). What’s more, Rosebud O Roberts et al. found that high C-reactive protein was a risk factor for non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment (11).

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 144 prospective studies showed that diabetes, even prediabetes and changes in diabetes-related biochemical markers could predict an increased incidence of dementia or cognitive impairment (12). Shuangling Xiu et al. (13) found that the elderly (community-dwelling participants aged ≥ 55 years) with impaired fasting glucose (IFG) had a lower performance on the MMSE test compared with subjects who had normal blood glucose. Jeannine S Skinner et al. (14) found that high non-diabetic fasting glucose levels were associated with poorer verbal memory and executive function. However, Sai Tian et al. did not find a link between fasting glucose and cognitive impairment (15). Therefore, the relationship between fasting glucose and MCI is not clear, nor can it be determined whether fasting glucose can be developed as a biomarker of MCI.

At present, other advanced biomarkers, such as MRI and PET, for the diagnosis, grading, classification and prognosis of MCI are still under investigation (16, 17). However, there is still little research on serum-based biomarkers that can be easily obtained through minimally invasive sample techniques for diagnosing MCI and assessing treatment response. To fill this gap, in the current cross-sectional study, we explored the practical value of using routine blood and blood biochemical markers, such as fasting glucose, to diagnose MCI.

Data was obtained from the cohort study on brain health of the elderly in Shanghai (http://www.shanghaibrainagingstudy.org/). This project was launched in 2016, which was a prospective and observational cohort study. The specific content of this project includes understanding the mortality, prevalence, incidence, and population distribution characteristics of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease among the elderly over 55 years old in Shanghai communities. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) ≥55 years; 2) permanent population of Shanghai; 3) no evidence of serious mental illness, such as intellectual disability and schizophrenia; 4) no evidence of serious physical illness; 5) agreed to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) <55 years old; 2) floating population; 3) serious mental illness and physical illness or acute stress state, for example, acute medical disorders; and 4) the guardians or the participants or refused to participate in the study. Finally, A total of 1015 seniors entered the database, 571 of whom were normal elderly, and the remaining 444 were identified as MCI.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Mental Health Center, and all the participants had signed informed consent before the study.

All the participants would undergo a clinical and cognitive assessment at baseline and follow-up. All the diagnoses were performed by trained and qualified medical clinicians. To improve the accuracy of research, we also collected their body fluids (blood and urine) and head MRI.

The diagnosis of MCI was based on Petersen’s diagnostic criteria (18): 1) self-reported or informant cognitive complaints; 2) objective memory disorder; 3) maintain the independence of functional ability; 4) without dementia.

All cognitively normal (NC) elderly people needed to meet the following criteria (19): 1) normal cognitive function; 2) without serious physical illness and mental illness; 3) absence of dementia or MCI; 4) be able to complete all tests.

In the current study, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was used to assess the subjects’ overall cognitive function. The MoCA is a brief cognitive screening tool with high specificity and sensitivity for detecting MCI as currently conceptualized in individuals performing in the normal range on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (20). Previous studies have shown that a MOCA score of 23, instead of the 26 originally recommended, can reduce the false-positive rate and show better diagnostic accuracy (21). Therefore, in the current study, we also used the MOCA 23 score as the threshold to distinguish MCI from normal.

Peripheral blood was collected from 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. after overnight fasting. Clot activating gel-containing serum separator tubes were used for testing of blood routine and blood biochemical parameters. During the same time period, samples were taken from each subject at the same approximate time, immediately sent to the hospital laboratory center, and measured before 11 a.m. that day. The red blood cell count, white blood cell count, platelet count, packed cell volume, and hemoglobin were measured by using an analyzer device (Mindray BC-6800, Shenzen, China). The total protein, triglycerides, high density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein, fasting plasma glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were measured by using an analyzer device (Roche Diagnostic COBAS c501).

By using standardized questionnaires, we collected general demographic data for these subjects, such as age, education, sex, current smoking status, current drinking status and disease related information, such as diabetes and hypertension. All of these variables would be considered as covariables.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (%). Independent sample t-test and Chi-square tests were used to compare the continuous variables and classification variables of the normal group and the MCI group, respectively. Next, we used the binary logistic regression models to examine the association between blood indicators and MCI, treating whether it is MCI or not as a dependent variable. Model 1 did not control any variables; Model 2 controlled some variables, such as education and diabetes. The ROC curve was used to explore the sensitivity and specificity of fasting plasma glucose to predict MCI.

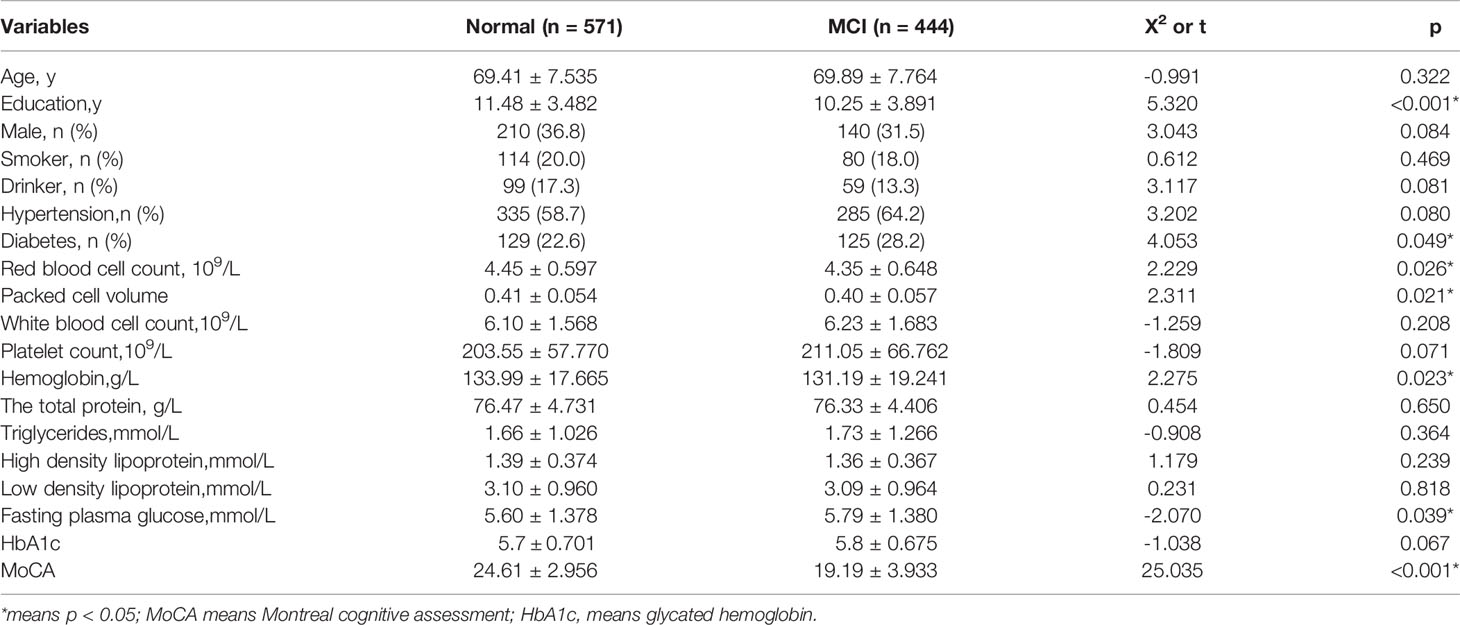

Compared with the MCI group, the normal group had longer years of education, a higher red blood cell count, a higher hemoglobin number, a higher packed cell volume, and a higher MOCA score, but lower fasting glucose levels and a lower proportion of diabetes(p<0.05). However, there was no statistical difference in age, sex, smoker, drinker, hypertension, white blood cell count, platelet count, hemoglobin, HbA1c, the total protein, triglycerides, high density lipoprotein and low density lipoprotein. Table 1 presents the results.

Table 1 Comparison of general demographic data, blood routine and blood biochemical indexes between the two groups.

Table 2 shows the results of stepwise binary logistics regression analysis (treating whether it is MCI or not as the dependent variable). Model 1 did not control any covariates (red blood cell count, packed cell volume, hemoglobin and fasting plasma glucose were treated as the independent variables), and the results showed that packed cell volume (p=0.013, OR=0.047, 95%CI:0.004-0.519) and fasting blood glucose (p=0.025, OR=1.118, OR=1.014-1.233) were the influencing factors of MCI. Model 2 built on Model 1 by further controlling for age, education, and diabetes, and did not change the results. Table 2 shows the results. Then, the ROC curve was used to determine packed cell volume or fasting blood glucose to predict the risk of MCI, and it was found that the area under the curve was 0.457 (p=0.028, 95%CI:0.420~0.495) and 0.553 (p=0.006, 95%CI:0.516-0.591), respectively. And the results suggest that fasting blood glucose had a mild effect in predicting MCI. Figure 1 presents the results.

In the current study, we explored the relationship between blood routine and common blood biochemical markers and MCI, and ultimately found that elevated fasting glucose was a risk factor for MCI. To my knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an inverse association between elevated fasting glucose and MCI. Therefore, we hypothesize that good control of fasting blood glucose might reduce the risk of future cognitive impairment.

Accumulated evidence suggests that abnormal glucose metabolism may contribute to the pathogenesis of MCI, for example, Sai Tian et al. found that increased plasma levels of β-Site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) were associated with poor overall cognition functions, especially visual/logical memory, visuospatial abilities, and executive functions in Diabetes-MCI patients (22). Sai Tian et al. found that high plasma Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) levels were correlated with an increased risk for MCI in diabetes patients (15). Hongjun Zhao et al. found that insulin resistance might be a risk factor for mild cognitive impairment and could be a biomarker for prediction of MCI in patients with diabetes (23). What’s more, our previous work also suggests that diabetes may contribute to the development of MCI (24).

In our study, we explored the relationship between a series of common blood biochemical and routine Indexes and MCI, such as red blood cells, white blood cells, hemoglobin, fasting glucose, etc. Through binary logistics regression analysis, and after controlling several variables such as age and education, we found that red blood cell count and fasting blood glucose were the influencing factors of MCI. However, since the area under the ROC curve of MCI predicted by red blood cell count was less than 0.5, we finally judged that elevated fasting blood glucose was the risk factor of MCI and had a mild predictive effect. Since there was no previous study on the relationship between fasting blood glucose and MCI, we could not judge whether the conclusion of our study was consistent with that of others.

There are several mechanisms to explain why elevated fasting blood glucose increases the risk of MCI. First, poorly controlled fasting blood glucose was associated with the development of long-term micro- and macro-vascular complications (25); Second, elevated fasting blood glucose was strongly associated with depression, which was considered a risk factor for MCI; Third, higher fasting blood glucose levels was associated with decreased striatal and hippocampal volume (26, 27). Fourth, elevated fasting blood glucose was associated with altered N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors/Wnt signaling and oxidative stress in the hippocampus (28). Finally, elevated fasting blood glucose could also lead to elevated inflammatory cytokines (29, 30).

We admit that our research has some limitations. First, it was only a cross-sectional study and could not establish a causal relationship between fasting blood glucose and MCI. Second, we did not further classify MCI, so it is impossible to determine whether fasting blood glucose is more likely to induce amnesiac MCI or vascular MCI.

Elevated fasting blood glucose may be a risk factor for mild cognitive impairment, but the above conclusions need to be verified by longitudinal studies.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Mental Health Center. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

WL contributed to the study concept and design. LY acquired the data. SX and LS analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by grants from the China Ministry of Science and Technology (2009BAI77B03), National Natural Science Foundation of China (number 81671402), Clinical research center project of Shanghai Mental Health Center (CRC2017ZD02), the National Key R&D program of China (2017YFC1310501500), the Cultivation of Multidisciplinary interdisciplinary Project in Shanghai Jiao Tong University (YG2019QNA10), curriculum reform of Medical College of Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Feixiang Program of Shanghai Mental Health Center(2020-FX-03), Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA12040101), Shanghai Clinical Research Center for Mental Health (SCRC-MH, 19MC1911100); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82101564); the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (20Y11906800).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

This project was funded by Shanghai Elderly Brain Health Cohort Institute, and we also thanked the patient advisers.

1. Petersen RC. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Continuum (Minneapolis Minn) (2016) 22(2 Dementia):404–18. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000313

2. Belleville S, Fouquet C, Hudon C, Zomahoun HTV, Croteau J. Neuropsychological Measures That Predict Progression From Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Type Dementia in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol Rev (2017) 27(4):328–53. doi: 10.1007/s11065-017-9361-5

3. Giau VV, Bagyinszky E, An SSA. Potential Fluid Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20(17):4149–55. doi: 10.3390/ijms20174149

4. Wang Y, Du Y, Li J, Qiu C. Lifespan Intellectual Factors, Genetic Susceptibility, and Cognitive Phenotypes in Aging: Implications for Interventions. Front Aging Neurosci (2019) 11:129. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00129

5. Hayajneh AA, Rababa M, Alghwiri AA, Masha’al D. Factors Influencing the Deterioration From Cognitive Decline of Normal Aging to Dementia Among Nursing Home Residents. BMC Geriatr (2020) 20(1):479. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01875-3

6. Trivitayaratana W, Bunyaratavej N, Trivitayaratana P, Kotivongsa K, Suphaya-Achin K, Chongcharoenkamol T. The Use of Historical and Anthropometric Data as Risk Factors for Screening of Low mBMD & MCI. J Med Assoc Thailand = Chotmaihet Thangphaet (2000) 83(2):129–38.

7. Li X, Ma C, Zhang J, Liang Y, Chen Y, Chen K, et al. Prevalence of and Potential Risk Factors for Mild Cognitive Impairment in Community-Dwelling Residents of Beijing. J Am Geriatr Soc (2013) 61(12):2111–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12552

8. Campbell NL, Lane KA, Gao S, Boustani MA, Unverzagt F. Anticholinergics Influence Transition From Normal Cognition to Mild Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults in Primary Care. Pharmacotherapy (2018) 38(5):511–9. doi: 10.1002/phar.2106

9. Du B, Lian Y, Chen C, Zhang H, Bi Y, Fan C, et al. Strong Association of Serum GSK-3β/BDNF Ratio With Mild Cognitive Impairment in Elderly Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Curr Alzheimer Res (2019) 16(12):1151–60. doi: 10.2174/1567205016666190827112546

10. Furney SJ, Kronenberg D, Simmons A, Güntert A, Dobson RJ, Proitsi P, et al. Combinatorial Markers of Mild Cognitive Impairment Conversion to Alzheimer’s Disease–Cytokines and MRI Measures Together Predict Disease Progression. J Alzheimer’s Dis JAD (2011) 26(Suppl 3):395–405. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-0044

11. Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Cha RH, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, et al. Metabolic Syndrome, Inflammation, and Nonamnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment in Older Persons: A Population-Based Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord (2010) 24(1):11–8. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a4485c

12. Xue M, Xu W, Ou YN, Cao XP, Tan MS, Tan L, et al. Diabetes Mellitus and Risks of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 144 Prospective Studies. Ageing Res Rev (2019) 55:100944. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100944

13. Xiu S, Zheng Z, Liao Q, Chan P. Different Risk Factors for Cognitive Impairment Among Community-Dwelling Elderly, With Impaired Fasting Glucose or Diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther (2019) 12:121–30. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S180781

14. Skinner JS, Morgan A, Hernandez-Saucedo H, Hansen A, Corbett S, Arbuckle M, et al. Associations Between Markers of Glucose and Insulin Function and Cognitive Function in Healthy African American Elders. J Gerontol Geriatr Res (2015) 4(4):432–40. doi: 10.4172/2167-7182.1000232

15. Tian S, Huang R, Han J, Cai R, Guo D, Lin H, et al. Increased Plasma Interleukin-1β Level is Associated With Memory Deficits in Type 2 Diabetic Patients With Mild Cognitive Impairment. Psychoneuroendocrinology (2018) 96:148–54. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.06.014

16. Ottoy J, Niemantsverdriet E, Verhaeghe J, De Roeck E, Struyfs H, Somers C, et al. Association of Short-Term Cognitive Decline and MCI-To-AD Dementia Conversion With CSF, MRI, Amyloid- and (18)F-FDG-PET Imaging. NeuroImage Clin (2019) 22:101771. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101771

17. Sanchez-Catasus CA, Stormezand GN, van Laar PJ, De Deyn PP, Sanchez MA, Dierckx RA. FDG-PET for Prediction of AD Dementia in Mild Cognitive Impairment. A Review of the State of the Art With Particular Emphasis on the Comparison With Other Neuroimaging Modalities (MRI and Perfusion SPECT). Curr Alzheimer Res (2017) 14(2):127–42. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666160629081956

18. Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rabins PV, et al. Current Concepts in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Arch Neurol (2001) 58(12):1985–92. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985

19. Li W, Li Y, Qiu Q, Sun L, Yue L, Li X, et al. Associations Between the Apolipoprotein E ϵ4 Allele and Reduced Serum Levels of High Density Lipoprotein a Cognitively Normal Aging Han Chinese Population. Front Endocrinol (2019) 10:827. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00827

20. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc (2005) 53(4):695–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

21. Carson N, Leach L, Murphy KJ. A Re-Examination of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Cutoff Scores. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2018) 33(2):379–88. doi: 10.1002/gps.4756

22. Tian S, Huang R, Guo D, Lin H, Wang J, An K, et al. Associations of Plasma BACE1 Level and BACE1 C786G Gene Polymorphism With Cognitive Functions in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Cross- Sectional Study. Curr Alzheimer Res (2020) 17(4):355–64. doi: 10.2174/1567205017666200522210957

23. Zhao H, Wu C, Zhang X, Wang L, Sun J, Zhuge F. Insulin Resistance Is a Risk Factor for Mild Cognitive Impairment in Elderly Adults With T2DM. Open Life Sci (2019) 14:255–61. doi: 10.1515/biol-2019-0029

24. Li W, Sun L, Li G, Xiao S. Prevalence, Influence Factors and Cognitive Characteristics of Mild Cognitive Impairment in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Aging Neurosci (2019) 11:180. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00180

25. Heller S, Houwing N, Kragh N, Ploug UJ, Nikolajsen A, Alleman CJ. Investigating the Evidence of the Real-Life Impact of Acute Hyperglycaemia. Diabetes Ther Res Treat Educ Diabetes Relat Disord (2015) 6(3):389–93. doi: 10.1007/s13300-015-0126-y

26. Zhang T, Shaw ME, Walsh EI, Sachdev PS, Anstey KJ, Cherbuin N. Higher Fasting Plasma Glucose Is Associated With Smaller Striatal Volume and Poorer Fine Motor Skills in a Longitudinal Cohort. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging (2018) 278:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2018.06.002

27. Cherbuin N, Sachdev P, Anstey KJ. Higher Normal Fasting Plasma Glucose is Associated With Hippocampal Atrophy: The PATH Study. Neurology (2012) 79(10):1019–26. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826846de

28. He A, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Li L, Feng X, Wei B, et al. Prenatal High Sucrose Intake Affected Learning and Memory of Aged Rat Offspring With Abnormal Oxidative Stress and NMDARs/Wnt Signaling in the Hippocampus. Brain Res (2017) 1669:114–21. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.05.022

29. Li X, Liao M, Shen R, Zhang L, Hu H, Wu J, et al. Plasma Asprosin Levels Are Associated With Glucose Metabolism, Lipid, and Sex Hormone Profiles in Females With Metabolic-Related Diseases. Mediators Inflamm (2018) 2018:7375294. doi: 10.1155/2018/7375294

30. Gunathilake R, Oldmeadow C, McEvoy M, Inder KJ, Schofield PW, Nair BR, et al. The Association Between Obesity and Cognitive Function in Older Persons: How Much Is Mediated by Inflammation, Fasting Plasma Glucose, and Hypertriglyceridemia? J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci (2016) 71(12):1603–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw070

Keywords: fasting plasma glucose, MCI, cross-sectional, elderly, Chinese

Citation: Li W, Yue L, Sun L and Xiao S (2021) Elevated Fasting Plasma Glucose Is Associated With an Increased Risk of MCI: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Endocrinol. 12:739257. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.739257

Received: 10 July 2021; Accepted: 28 October 2021;

Published: 16 November 2021.

Edited by:

Fabio Monzani, University of Pisa, ItalyReviewed by:

Maria Cristina Barbalace, University of Bologna, ItalyCopyright © 2021 Li, Yue, Sun and Xiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lin Sun, eGlhb3N1YW4yMDA0QDEyNi5jb20=; Shifu Xiao, eGlhb3NoaWZ1QG1zbi5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.