- Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, Dresden, Germany

Ever since the discovery of thyroid hormone deficiency as the primary cause of cretinism in the second half of the 19th century, the crucial role of thyroid hormone (TH) signaling in embryonic brain development has been established. However, the biological understanding of TH function in brain formation is far from complete, despite advances in treating thyroid function deficiency disorders. The pleiotropic nature of TH action makes it difficult to identify and study discrete roles of TH in various aspect of embryogenesis, including neurogenesis and brain maturation. These challenges notwithstanding, enormous progress has been achieved in understanding TH production and its regulation, their conversions and routes of entry into the developing mammalian brain. The endocrine environment has to adjust when an embryo ceases to rely solely on maternal source of hormones as its own thyroid gland develops and starts to produce endogenous TH. A number of mechanisms are in place to secure the proper delivery and action of TH with placenta, blood-brain interface, and choroid plexus as barriers of entry that need to selectively transport and modify these hormones thus controlling their active levels. Additionally, target cells also possess mechanisms to import, modify and bind TH to further fine-tune their action. A complex picture of a tightly regulated network of transport proteins, modifying enzymes, and receptors has emerged from the past studies. TH have been implicated in multiple processes related to brain formation in mammals—neuronal progenitor proliferation, neuronal migration, functional maturation, and survival—with their exact roles changing over developmental time. Given the plethora of effects thyroid hormones exert on various cell types at different developmental periods, the precise spatiotemporal regulation of their action is of crucial importance. In this review we summarize the current knowledge about TH delivery, conversions, and function in the developing mammalian brain. We also discuss their potential role in vertebrate brain evolution and offer future directions for research aimed at elucidating TH signaling in nervous system development.

Introduction

Thyroid hormone (TH) signaling is an ancient regulatory mechanism dating back to early eukaryotes. The use of iodinated amino acids and bona fide THs to control development and trigger major life transitions precedes the ability to produce these molecules internally (1–4). Endogenous TH production within a specialized gland of animals appears in the evolution of basal chordates ~550 million years ago (1, 2, 4–6). In vertebrates THs are crucial for both development and adult life as they regulate tissue differentiation, maturation and whole body metabolic function (7). They also trigger major life transitions and metamorphosis in multiple chordate species (6, 8).

Although attempts to treat goiter with iodine-rich foods were made already in antiquity (9), the importance of thyroid gland secretions in human health was scientifically recognized only at the end of 19th century. In that time thyroid deficiency was linked to myxedematous cretinism with the first successful treatment by thyroid extract injection published by the end of the century (10, 11). THs were subsequently identified as active components, chemically characterized and synthesized in the early 20th century (12–14). Specific functions of TH signaling in brain development were also recognized with the systematic observations of the neurological cretinism prevalent in regions with iodine deficiency (15, 16). Since then our knowledge about the many roles of THs in the regulation of fetal brain development has grown exponentially. This review focuses on the functions of THs in early development of the mammalian central nervous system (CNS), with an emphasis on cerebral cortex development and evolution. Functions of THs in the postnatal development and brain function, including as regulators of adult neurogenesis, have been reviewed elsewhere (17–20).

Production and Metabolism of THs—Maternal and Fetal Sources

Mammalian THs are produced in two forms – 3,3′,5-triiodothyronine (T3) and 3′,5′,3,5-tetraiodo-L-thyronine (T4 or thyroxine). T4, the main product of thyroid gland secretion, has a low affinity for nuclear TH receptors (TRs) and therefore is thought to act largely as a prohormone in the classical TH signaling pathway (8). In contrast, biologically active T3 has a high affinity for nuclear TRs (21, 22) and is produced by either the thyroid gland or locally from T4 by target tissues and cells (23–25). Additionally, multiple TH-derivatives arise as products of TH metabolism, some of which have biological activity while others are degradation byproducts and storage forms (26).

There are two main periods in prenatal development of placental mammals with regard to TH production and delivery into the fetal nervous system. In early development an embryo relies solely on the maternal source of THs as its thyroid gland is not yet fully functional. The thyroid gland develops early in pregnancy from an anterior region of the embryonic gut, however, in humans it does not secrete significant TH levels until mid-gestation (27). Therefore the 1st trimester of human pregnancy proceeds with a full dependence on maternal TH secretion, and afterwards fetal TH production raises gradually (28, 29). In agreement with the fetal demand for THs in pregnancy total maternal T4 and T3 levels rise through the 1st trimester and stay elevated for the remainder of pregnancy. In the same time, due to the increased binding to rising levels of maternal serum thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG), free T4 and T3 levels decrease after the initial peak at the onset of pregnancy and remain comparable with non-pregnant women (30). During pregnancy, high total TH levels are needed to meet the rising demands of the fetus as well as the mother (29, 31, 32). In cases of fetal TH production deficiencies caused by events like thyroid gland agenesis, maternal THs are largely able to substitute for fetal TH production (33, 34). Even after the onset of fetal TH production the maternal source of THs seems to be important for proper brain development, as can be deduced from the developmental deficits seen in premature infants (35). Although in the fetus total T4 and T3 concentrations are very low in early pregnancy, free T4 concentrations in the amniotic fluid and fetal serum increase to almost adult levels by mid-gestation, likely due to a low presence of TH binding carrier proteins, and could therefore exert biological function (29, 31). Free T4 is taken up by fetal tissues and gets converted to T3 locally (36).

T3, T4 and some of their metabolites are subject to the activity of three selenocysteine-containing iodothyronine deiodinases (Dio1-3) that produce both active and inactive products, thereby controlling the amount of biologically active THs and targeting their metabolites for further degradation and clearance (37). Type III iodothyronine deiodinase (thyroxine 5-deiodinase, Dio3) robustly catalyzes inner ring deiodination (IRD) of T4 and T3 to rT3 (3,3′,5′-triiodothyronine) and 3,3′-T2 (3,3′-diiodothyronine), respectively (38), resulting in inactivated forms of these hormones that have little affinity for nuclear TRs and undergo rapid removal (39). In contrast, Dio2 (type II iodothyronine deiodinase) primarily activates T4 by converting it to the active receptor-binding T3 form by outer ring deiodination (ORD) (40). Dio1 (type I iodothyronine deiodinase) can catalyze both IRD and ORD, which leads to T4 inactivation or activation, respectively, but with lower activity toward T4 than Dio2 (41). It is mainly expressed postnatally and outside of the placenta or CNS, which make it less important for fetal brain development (42, 43).

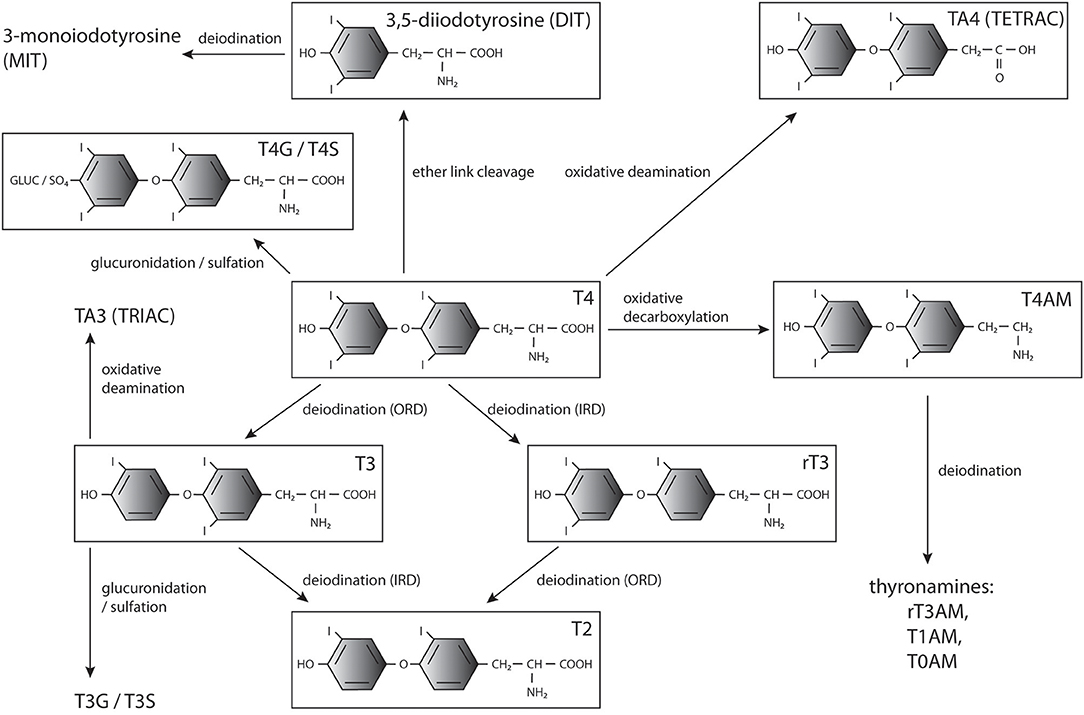

In addition, TH modifications, including decarboxylation, deamination, ether-link cleavage, sulfation, and glucuronidation, affect their bioactivity and downstream metabolism (Figure 1). Most of them lead to deactivation and eventually degradation of THs (26), however some of the generated compounds, such as rT3 (44, 45), iodothyroacetic acids (tetrac and triac) and thyronamines (46–50), have been shown to convey biological effects in specific contexts. The conversions and main metabolites of THs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. THs and major products of their metabolism. T4, 3′,5′,3,5-tetraiodo-L-thyronine (thyroxine); T3, 3,3′,5-triiodothyronine; T2, 3,3′-diiodothyronine; rT3, 3, 5′,3′,-triiodothyronine;, diiodotyrosine; MIT, monoiodotyrosine; T3G, triiodothyronine glucuronidate; T4G, thyroxine glucuronidate; T3S, triiodothyronine sulfate; T4S, thyroxine sulfate; TRIAC, triiodothyroacetic acid; TETRAC, tetraiodothyroacetic acid; T1AM, 3-iodothyronamine; T0AM, thyronamine.

Sulfation and glucuronidation of the phenolic 4′-hydroxyl group of THs are considered phase II detoxification reactions as they increase the solubility of the products (51, 52). Sulfation is catalyzed by cytoplasmic sulfotransferases (SULTs) that transfer a sulfate group from the donor 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) to their substrates (53) and is utilized to inactivate THs. T3 sulfate (T3S) does not bind TRs (54) and Dio1-mediated ORD of T4 sulfate (T4S) is blocked while simultaneously IRD of both T4S and T3S is stimulated (55–58). Normally levels of sulfated THs in circulation and in excretions are low due to fast deiodination and clearance, but high levels of these metabolites are present in fetal circulation, likely due to the absence of Dio1 activity (59–62). Sulfotransferases producing T4S and T3S are present in the placenta, and sulfated TH metabolites can be transferred from the fetus into maternal circulation, potentially playing a role in regulating TH levels (52). Sulfated as well as glucuronidated THs may also serve as a pool of inactive hormones that can be mobilized by bacterial sulfatase or β-glucuronidase activity and reabsorption from the bile in the intestine (63–69) or hydrolysis by tissue sulfatases in the brain, kidneys and liver (70, 71).

TH Delivery into the Developing Brain—Transport Across Biological Barriers

TH delivery into the fetal brain requires passage through multiple barriers at the feto-maternal interface and between fetal circulation and the CNS. THs are actively transported across tissue barriers, including placenta, and brain blood barrier (BBB), and into target cells. In circulation free THs are present only in minute amounts and mostly are bound to carrier-proteins. The main TH binding proteins in human plasma are mammalian-specific TBG, albumin and transthyretin (prealbumin, TTR) (72), the latter being also an exclusive TH carrier in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), where it makes up to 20% of total protein (73–75). A minor portion of THs is bound to ApoB100 and other lipoproteins (76). Carrier binding determines the amount of free vs. total THs in circulation, from which only the free fraction is readily available for uptake by cells, whereas protein bound THs are considered to be biologically inert (77, 78). TH entry and exit from cells are mediated by membrane transporters. A number of proteins capable of TH transport have been identified, including monocarboxylate transporters MCT 8 and 10, organic anion carrier transporter polypeptides (OATPs), Na+/taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide NTCP, and heterodimeric amino acid transporter (HAT) members/L-type aromatic and large branched-chain amino acid transporters LAT1 and 2. They differ in expression pattern and affinity for THs and their metabolites as well as ability to transport other compounds. Multiple TH transporters are expressed already during fetal nervous system development, the most important being MCT8 and OATP1C1 (79–101).

Before the onset of fetal TH production THs enter fetal tissues by passing through the placenta, which serves as an active filter allowing only limited amounts of the active hormone to enter the fetus (31, 34). The main deiodinase expressed in the placenta is Dio3 (102), the ability of which to inactivate THs is thought to protect the developing fetus from toxic levels of the maternal hormones, especially in the brain, which is uniquely vulnerable (103–105). Notably, Dio3 has a preference for T3 as substrate, which contributes to T4 being the main TH passing through the placenta (106). Dio2 is also present in the placenta, albeit at lower levels than Dio3 (107, 108), and is thought to act as a provider of bioactive T3 for local use. Total fetal T4 is kept lower than the adult level for the entire gestation in both human and rodents until birth or at 2 weeks postnatally, respectively (32, 109). An additional mechanism balancing active TH levels involving sulfation was postulated (52), although only low activity toward THs by the placental sulfotransferases was detected (110).

In the 1st trimester of pregnancy most of the THs are thought to be taken up by the fetus from the coelomic and/or amniotic fluid, while from the 2nd trimester onwards direct transfer to the fetal circulation starts to play a more important role (29). Prior to neural tube closure THs can access the developing CNS directly from the amniotic fluid. Afterwards THs get delivered into the brain either through the BBB of the developing vasculature or the choroid plexus (CP) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) system. Endothelial cells of both the brain capillaries and the CP express transporters and TH modifying enzymes controlling TH levels entering the brain (111).

Cellular Signaling of THs and Its Functions in Mammalian Fetal Brain Development

Expression and Signaling Pathways of TH Receptors in the Early Nervous System

THs versatile functions are dependent on cellular responses mediated by their interaction with various receptors expressed in cell- and tissue-specific manner. In target cells THs trigger either genomic responses mediated by DNA-binding nuclear TRs or non-genomic responses by alternative non-nuclear receptors. Genomic effects on gene transcription require members of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily type II, in mammals encoded by two related genes arising from whole genome duplication in vertebrates: THRA/NR1A1 and THRB/NR1A2, which produce TR α and β, respectively (112–114). Each of these genes can undergo alternative splicing and harbors alternative promoters, resulting in a number of distinct isoforms differing in their ability to bind target DNA sites, ligand binding, and co-factor recruitment (114, 115). The isoforms that possess both DNA and ligand binding capacity and localize to the nucleus are TRα1 and β1-3 (with TRβ3 being rat-specific), and these are the ones that mediate the genomic effects of THs (116, 117). Other isoforms act as dominant-negative regulators or have non-genomic functions (118–120). TRβ1 and 2 possess the same DNA binding domain, but their N-termini differ in the activation domain, which in β2 favors coactivator recruitment (121, 122). TRα1 and TRβ1 differ in DNA-binding affinity and selectivity (123), T3 affinity (124), and the ability to form dimers (125). T3 is the active form of the hormone capable of binding to these receptors as T4 has about 10 times lower affinity for TRs (21, 22). However, direct T4 binding with biologically significant effects has also been shown recently (126, 127).

To affect transcription of target genes TRs bind DNA as either homodimers or heterodimers with retinoid-X-receptors and recognize TH response elements (TREs) in promoter regions of regulated genes (114). TRs lacking bound THs can bind DNA as aporeceptors, which represses target gene transcription by recruiting corepressor complexes with histone deacetylase activity (128, 129). T3 binding lifts this repression and leads to target gene transcription, which is necessary for normal nervous system development (130–132). While T3/TR interaction results in coactivator recruitment, chromatin restructuring, and transcriptional activation for most targets, some genes can also be repressed by TRs with bound THs (133, 134). Accordingly, a meta-analysis study of genes transcriptionally regulated by THs in the nervous system identified over 700 curated targets, however the extent and mode of their regulation is likely to differ during development and in specific cell types (135). More targeted studies are needed to explain the differential cellular responses to THs in various contexts. The interplay between various TR isoforms, chromatin re-modeling and transcriptional machinery leads to complex tissue and cell-specific responses in various contexts and comprehensive reviews on the mechanistic aspects of the genomic pathway are available (136–138).

Tissues differ in TR isoform expression patterns and cell-specific functions. TR isoforms share many common targets, however, there is marked spatiotemporal variation in the degree and mode of regulation and target overlap. Frequently cells express multiple isoforms with distinct roles arising due to differences in the respective protein levels or intrinsic activity (117). Nuclear TRs are expressed in the developing brain of humans and rodents (22, 139, 140), and T3 binding in the human brain occurs even before fetal thyroid gland maturation (22, 141, 142). TRα1 is the major isoform expressed in neurons from early fetal development in humans and rodents onwards, while TRβ increases perinatally and is more abundant in specific neuronal types such as hippocampal pyramidal and granule cells, paraventricular hypothalamic neurons and cerebellar Purkinje cells (143–145). Interestingly, TRβ1 is also expressed in the germinal zones of cerebral cortex (145). During early postnatal development in rodents TRβ is specifically required for enhancing the expression of the striatum-enriched gene Rhes (146). Rhes functions in multiple signaling pathways and has been implicated in the regulation of dopamine-mediated synaptic plasticity of striatal neurons, in striatum-related behaviors, and in neurodegeneration in the course of Huntington disease (147). Moreover, TRβ1 and 2 are required for the cochlear and retina development, and TRβ null mice have defects in auditory and visual development (148). TRβ2 also plays a role in establishment and maintenance of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid gland axis (114). Most neurons express both TRα and TRβ receptors, however, the relative expression levels differ, which can have important functional consequences such as in the hippocampus, where TRα but not β is necessary for proper GABAergic interneuron innervation and behavior (145, 149). The relative abundance of both receptors was also proposed to control proliferation/differentiation balance in the developing brain (145). In addition, certain specific cell types express exclusively either TRα or TRβ form. For instance, parvalbumin (PV) positive cells in the CA1 of the hippocampus express preferentially TRα while the PV+ interneurons in the somatosensory cortex produce mostly TRβ (149). Also developing cerebellar granule cells express TRα1 but not TRβ while Purkinje cells produce mostly TRβ (144, 145, 150).

TR mutations in both rodents and humans have been linked to a range of behavioral and cognitive phenotypes, including changes in sensory, attention, emotion and memory functions, but their effects are complex and usually more benign than those of hypothyroidism (149, 151–155). Detrimental effects of hypothyroidism are thought to occur largely due to the repressive activity of TRs lacking bound THs, as mice completely lacking both TR receptor types are viable and without major defects (153). Moreover, TRα1 KO rescues the viability of Pax8 KO mice, which present with thyroid agenesis and lethal congenital hypothyroidism during the early postnatal period (156), and partly rescues the Dio3 KO phenotype (157). TRs lacking bound THs are generally implicated in maintaining the proliferative, undifferentiated state of neural progenitors, while T3-bound receptors promote transcription of genes triggering cell differentiation and maturation (129, 158–160).

In addition to the classical pathway mediated by nuclear TRs, a growing list of TH effects have been linked to their non-genomic actions, including regulation of actin polymerization (161), Dio2 activity (162), ion transport (163), Akt/PKB and mTOR pathway activation (164), and fatty acid metabolism (165). Non-genomic effects of THs can also influence cell proliferation and survival (166). Among receptors mediating the non-genomic functions of THs is a cell surface TH receptor, integrin αvβ3 (167, 168), which preferentially binds the T4 pro-hormone to activate the MAPK signaling cascade. This interaction promotes angiogenesis (167) and proliferation in osteoblasts and various cancer cell types (169–171). Signaling through this receptor has also been implicated in neocortical development as T4 binding to integrin αvβ3 upregulates progenitor proliferation in this structure (172). A detailed review of the non-genomic effects of THs in various cell types can be found elsewhere (120).

THs also interact with other signaling pathways during cortical development. In neural development sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling leads to an increase in Dio3 expression while decreasing Dio2 by ubiquitination (108). In turn both fetal and adult brain T3 upregulated Shh production (134, 173), thus providing a negative feedback loop. TH and Shh pathways interact also in cerebellar development to control granule cell precursor proliferation (174). Brain morphogen retinoic acid (RA) shares common carrier proteins with THs, and their nuclear receptors dimerize. RA can also increase MCT8 expression to increase TH import (175). Another transcription factor, COUP-TF1 (Chicken Ovalbumin Upstream Transcription Factor 1), has been shown to bind to DNA sites overlapping with TREs and to block TR access and activation (176, 177) thereby modulating TH signaling. Genes that show the presence of both TR and COUP-TF1 binding elements include calcium calmodulin-dependent kinase IV (CamKIV) (177, 178), which is important for both GABAergic and glutamatergic neuron production (179, 180). Emx1 and Tbr1 genes are also controlled by both THs and COUP-TF1, with the latter factor modulating the timing and magnitude of the T3 response (180). Similarly, nuclear liver X receptor β interacts with TH signaling in regulating cortical layering, likely by influencing the expression of their common target, the reelin receptor ApoER2 (181).

Developmental Hypothyroidism and Its Impact on Brain Development

The complexity of TH production, delivery, and metabolism contributes to varying clinical presentations of different TH signaling deficiencies during gestation, with the most severe being iodine deficiency which impairs both maternal and fetal TH supply (15, 182). Maternal iodine deficiency or severe hypothyroxinemia alters embryonic brain development even before the fetal thyroid gland becomes functional (183, 184), and leads to profound neurological cretinism with defects in sensory, motor and cognitive functions (15, 28, 185, 186). TH deficiencies, even when limited to the 1st trimester of gestation, are linked to cognitive deficits and neurodevelopmental delay (183, 187, 188). In contrast, fetal TH production defects, such as congenital hypothyroidism caused by thyroid agenesis, can largely be compensated by maternal THs (33, 34, 189), with most deficiencies in development arising postnatally if these defects are not treated (109, 190).

Given the selective placental permeability for T4, even mildly hypothyroid or asymptomatic cases of maternal iodine deficiency, lowering T4 but not T3 levels, can reduce fetal THs enough to cause developmental defects (182, 186, 189). Moreover, maternal T4 but not T3 supplementation protects the brain from hypothyroid injury until birth (34, 189, 191). As in the placenta, the main TH form transported into the CNS is T4, and the majority of the cerebral cortex T3 comes from local tissue production by Dio2 (192, 193), rendering the brain dependent mostly on circulating fetal T4 levels (28). The brain seems to be privileged in taking up T4 from the fetal circulation compared to other tissues, while the opposite is true for T3 (34). TH transporters facilitate entry from the circulation into the developing brain. Postnatally T4 is mainly taken up by astrocytic OATP1C1 and converted to bioactive T3 by the action of Dio2 (94, 194), which is expressed almost exclusively in glial cells (195, 196). Generated bioactive T3 is then provided to neurons, which lack Dio2 activity but express high levels of Dio3, allowing them to deactivate glia-derived excess THs (43, 196, 197). Neurons take up T3 preferentially over T4 via the MCT8 transporter either from astrocytes or directly from the interstitial fluid (198–200).

The Dio2/Dio3 activity balance provides an important mechanism for regulating active T3 levels in the brain to protect against excess THs (201). Both Dio2 and Dio3 activities are present in the fetal brain already from the 1st trimester onwards but show opposing trends with Dio3 being more active early and Dio2 toward the end of gestation (202–204). Dio3 KO in mouse, in contrast to other deiodinases, causes widespread abnormalities in brain and sensory organs, but it is unclear to which degree this phenotype is generated prenatally and arises due to placental or CNS deficiency (104, 105, 205). Similarly, human mutations affecting Dio3 imprinting result in Temple or Kagami-Ogata syndromes that impair brain function; however, whether this phenotype can be fully attributed to the altered dosage from the Dio3 locus is unclear (206). Additional mechanisms controlling active TH levels may also be present as TH sulfotransferases were shown to be expressed and active in the developing human brain (207, 208).

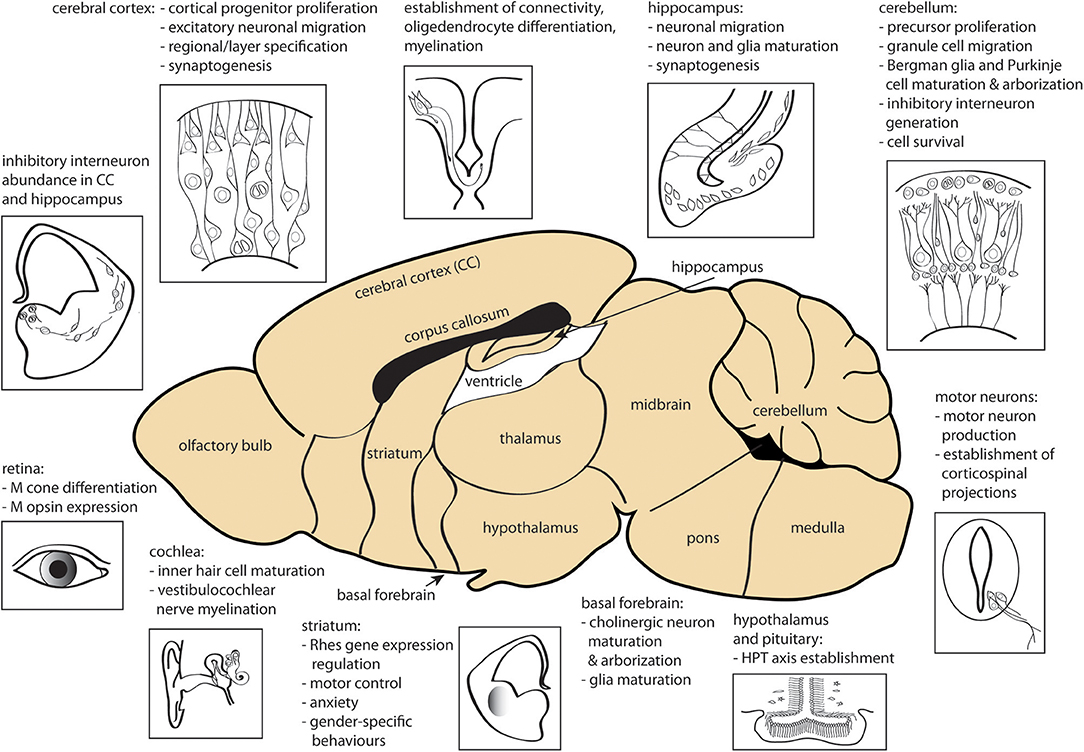

Fetal and perinatal TH deficiency, due to congenital hypothyroidism or iodine deficiency, has a dramatic negative impact on cerebral development, affecting multiple regions including cerebral cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and basal ganglia as well as motor neurons, cochlea, retina and interregional connectivity (15, 183, 184). Most of the early brain developmental events (proliferation of neural progenitors and neuronal migration in the neocortex, hippocampus, and medial ganglionic eminence) occur before fetal TH production, and thus are predominantly under the control of maternally-derived TH signaling. However, later stage processes (ongoing neurogenesis and migration, axon growth, dendritic arborization, synaptogenesis, and early myelination) occur after the onset of fetal TH production and proceed under the control of both fetal and maternal THs. Further brain developmental events (cortex pyramidal cell, hippocampal granule cell and cerebellar granule and Purkinje cell migration, gliogenesis, and myelination) occur postnatally and are therefore controlled entirely by neonatal THs. TH signaling has an effect on all of these processes (158, 209). The diverse actions of TH in early brain are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Sites of action of THs during CNS development. Processes affected by TH signaling prenatally and in early postnatal development are shown. CC, cerebral cortex; HPT, hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid gland; M, middle-wavelength sensitive. The figure was created using the mouse brain schematic available under Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication license.

Functions of TH Signaling During Development of Mammalian CNS

Human cretinism has been extensively modeled in rodents. In human, cortical neurogenesis occurs between week 5 and 20 of gestation, which is the period when the fetus depends primarily on the maternal source of THs, corresponding roughly to rat E12-18 (27, 209). In cortical development neurons are generated from progenitor cells residing in the subventricular zone and migrate basally along radial glia fibers to form an ordered 6-layered cortical plate, a process controlled largely by pioneer Cajal-Retzius and subplate neurons (210, 211). Perturbations of this migratory process lead to defects in cortical morphology and function (212). Even mild or transient maternal hypothyroxinemia during neurogenesis retards fetal glutamatergic neuron migration along the radial glia scaffold in the rat sensory cortex and hippocampus, without affecting tangentially migrating GABAergic neurons. This deficiency results in reduced neocortical thickness, blurred cortical layering and subcortical band heterotopia, likely responsible for increased seizure susceptibility and altered behavior (184, 190, 213–216). Improper neuronal migration also leads to alterations in callosal connectivity (213, 217). These migration defects can be at least partly attributed to a direct effect of the lack of THs on guiding cues as THs regulate Reelin, Dab1, and Vldlr expression in rat neocortex and cerebellum (218–220). T3 signaling also controls the expression of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 in Cajal-Retzius cells and hippocampal neurons during development (221), a protein known to affect glial cell migration (222). Moreover, a large subset of subplate neuron-enriched genes were shown to be under TH regulation (160). Maternal hypothyroidism alters gene expression in the brain by midgestation, and while it can be corrected by T4 application (223), the morphological changes persist if hormones are replaced after the critical window has closed (36).

TH signaling affects not only migration but also enhances progenitor proliferation and cortical neurogenesis, which is regulated by both genomic and non-genomic TH action (172, 180, 224). Hypothyroidism causes cell cycle disruption, increased apoptosis and reduction in both apical and basal progenitor pools and defects in neuronal differentiation, leading to cortical thickness reduction and decreased neuron number, especially in upper cortical layers (224). THs were shown to upregulate genes involved in cell cycle regulation and sustained proliferation in the developing cortex, such as POU2F1/Oct-1 or Nov (178, 223). Signaling through various pathways could have opposing roles in regulating proliferation/differentiation balance as T4 binding to integrin αvβ3 upregulates progenitor proliferation in the developing cortex (172), while T3 regulates gene expression in primary cerebrocortical cells via a nuclear TR-dependent pathway consistent with a role in promoting neuronal differentiation (160). Even mild hypothyroxinemia induces shifts in gene expression in developing hippocampus and neocortex (225). Among TH-regulated targets are genes involved in neuronal specification and function, such as Emx1 (Empty spiracles homolog 1), Tbr1 and neurogranin (180, 226–228), as well as cytoskeleton components and ECM molecules, which impact on both proliferation and neuronal migration (134, 229). T3 also regulates the expression of DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a in mouse brain, potentially extending the genomic effects of TH action beyond directly regulated genes by affecting global DNA methylation states (230). Seemingly contradictory functions of THs in promoting progenitor proliferation and neuronal differentiation may stem from specific spatiotemporal expression of their transporters, metabolizing enzymes, and effectors that mediate different actions in various cell types in the course of development.

While progenitor proliferation, cortical neurogenesis and early neuronal migration occur largely prenatally, THs have a profound effect also on perinatal CNS developmental events. During that period, the TH deficiency associated with congenital hypothyroidism leads, in both rodent and humans, to defects in late neuron migration, cerebellar neuron and glia arborization and maturation (231–233), astrocyte and neuron differentiation in hippocampus (234–236), inhibitory neuron development and function (237, 238), oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination (129, 239, 240), and synaptogenesis (241, 242). TH signaling also controls spinal motor neuron generation in vertebrates (243) and establishment of corticospinal projections (244).

The impact of perinatal TH deficiency on brain development has been intensely studied in two vital regions associated with hypothyroid injury, especially related to motor function impairment—the striatum and the cerebellum (245). In mammalian cerebellum the final TH-dependent stages of development occur perinatally, when cells from the external germinal layer proliferate and migrate to the inner granular layer forming connections with maturing Purkinje cells (246). TH signaling affects all of these processes. In cerebellum migration of granular cells requires ligand bound TRα, while maturation of Purkinje cells depends on the functions of both TRα and β isoforms. Additionally, TRβ is required for adequate granule cell proliferation (247). Interestingly, the hypothyroid injury on the developing cerebellum can be largely rescued by TRα1 deletion, in agreement with the function of TH in relieving the receptor-mediated transcriptional repression (248).

In the striatum a connection between TH-regulated gene expression and brain-region specific function involves the Ras-like GTP-binding protein Rhes/Rasd1. Despite being expressed in multiple brain regions from midgestation this gene shows a specific striatal upregulation in early postnatal rodent development that is critically dependent on THs (249–251). Developmental Rhes enrichment in this structure is dependent on T3 binding to TRβ isoform (146), however adult expression seems to rely primarily on TRα (252). Interestingly, Rhes functions in G-protein coupled receptor signaling as well as in PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways (253, 254) to modulate synaptic transmission (255), and Rhes KO animals have deficits in striatum-controlled behaviors (256), providing a potential functional link between hypothyroidism and resulting motor and affect dysfunctions.

THs in Mammalian Brain Evolution

In addition to their relevance regarding neurodevelopmental disorders, THs may have played a crucial role in human brain evolution. Although mostly limited to comparison between human and rodents, a number of important differences in TH signaling have been characterized. Spatiotemporal expression patterns of TH transporters are species-specific and can lead to drastic differences in TH metabolism, evident especially in disease states. Strikingly, the effects of MCT8/SLC16A2 mutations, which in human cause severe brain hypothyroidism with concomitant hyperthyroidism in circulation and peripheral organs, known as Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome (AHDS), characterized by severe intellectual and motor disability (257–259), are not fully recapitulated by mice, especially with regard to the neurological phenotype (91, 260–262). In rodents, only MCT8 and OATP1C1 double-inactivation causes cerebral hypothyroidism and associated defects (263). Various explanations, including the presence of compensatory alternative transport or T3 production pathways in rodents (264, 265) or the differential expression of the LAT2 transporter in neurons (91), have been suggested.

A potential evolutionary difference in TH delivery between rodents and human may exist, pertaining to the carrier protein TTR. In human TTR is present in the CSF as early as from the 8th fetal week (75), and in contrast to TBG and albumin there are no known individuals with TTR null mutations, suggesting its vital role in development (72). However, TTR null mice are viable and do not have overt symptoms of hypothyroidism in the CNS (266). Interestingly, TTR evolution in vertebrates, leading to its synthesis in the CP and a shift in specificity from T3 to T4 in the mammalian protein, coincides with the emergence of the cerebral cortex as a novel structure (72). It is tempting to speculate that the evolutionary expansion of the neocortex in the primate lineage may be linked to increased dependence on the function of TTR during development. Subtle differences in serum TTR abundance and posttranslational modifications were detected between human and several other species of great apes, but their functional and evolutionary importance remains to be elucidated (267).

In rodent neocortex development increasing TH-mediated integrin αvβ3 activation promotes basal progenitor proliferation (172). In contrast, blocking integrin αvβ3 has the opposite effect on ferret basal progenitors (268). Increased pool size and proliferative capacity of basal progenitors are thought to have contributed to the evolutionary expansion of the neocortex, especially in the primate lineage (229). Interestingly, a number of human genes implicated in TH metabolism are altered in human basal progenitors compared to mouse (208), which may affect the magnitude and timing of TH action during cortical neurogenesis.

One of the major concepts in human evolution is neoteny, especially in relation to brain development and function (269). Alterations is TH signaling are known to underlie evolutionary heterochrony in various animal species (6), including our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees and bonobos (270). The global TH status in rodents is connected to either accelerated or delayed development in hyperthyroid and hypothyroid pups, respectively (271). Given that in the CNS THs tend to accelerate cell type maturation (272, 273), one could speculate that prolonged or enhanced brain protection from THs and spatiotemporal alterations in metabolic enzyme and effector expression in the primate lineage could have delayed differentiation, contributing to human neoteny. Further studies investigating species-specific differences in TH pathways in brain development, especially including other model species, beyond human and rodent, could help to test this hypothesis.

Conclusions

TH action with regard to mammalian brain development is highly pleiotropic, and despite many advances the complexity of their delivery, metabolism, and cell-specific responses make it difficult to dissect specific functions in brain regions and cell subtypes in the course of development. With the advent of single-cell transcriptomics and the CRISPR/Cas9 technology, the spatiotemporal dissection of TH signaling in various cell types across the nervous system should become faster and more precise. This is of crucial importance, as in addition to the long-recognized role of TH deficiency in neurodevelopmental defects, undiagnosed developmental hypothyroxinemia may be linked to common neurological disorders such as ataxias and epilepsy (274, 275). Elucidation of the mechanisms underlying these pathologies down to the cellular and subcellular level could aid better diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Understanding and expanding the existing catalog of the evolutionary differences in TH signaling, which momentarily includes mostly genes linked to human genetic diseases such as AHDS or Kagami-Ogata syndrome, could also contribute to the generation of better disease models. Of note, when reaching conclusions about the role of THs in the human brain from rodent studies, it is important to keep in mind the at times profound phenotypic variation across species and its impact on disease presentation and potential treatments.

Author Contributions

BS and WH made substantial contributions to the conception and drafting of the work and revising it critically. WH approved the final version of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kaja Moczulska and Nereo Kalebic for critically reading the manuscript and Jonas Töle for providing the mouse brain schematic used in Figure 2 under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication license through Wikimedia Commons. Work in the Huttner lab was supported by grants from the DFG (SFB 655, A2), the ERC (250197), and ERA-NET NEURON (MicroKin).

References

1. Johnson LG. Thyroxine's evolutionary roots. Perspect Biol Med. (1997) 40:529–35. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1997.0076

2. Heyland A, Moroz LL. Cross-kingdom hormonal signaling: an insight from thyroid hormone functions in marine larvae. J Exp Biol. (2005) 208(Pt 23):4355–61. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01877

3. Yun AJ, Lee PY, Bazar KA, Daniel SM, Doux JD. The incorporation of iodine in thyroid hormone may stem from its role as a prehistoric signal of ecologic opportunity: an evolutionary perspective and implications for modern diseases. Med Hypotheses. (2005) 65:804–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.02.007

4. Crockford SJ. Evolutionary roots of iodine and thyroid hormones in cell-cell signaling. Integr Comp Biol. (2009) 49:155–66. doi: 10.1093/icb/icp053

5. Paris M, Brunet F, Markov GV, Schubert M, Laudet V. The amphioxus genome enlightens the evolution of the thyroid hormone signaling pathway. Dev Genes Evol. (2008) 218:667–80. doi: 10.1007/s00427-008-0255-7

6. Laudet V. The origins and evolution of vertebrate metamorphosis. Curr Biol. (2011) 21:R726–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.030

7. Pascual A, Aranda A. Thyroid hormone receptors, cell growth and differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2013) 1830:3908–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.03.012

8. Paris M, Laudet V. The history of a developmental stage: metamorphosis in chordates. Genesis. (2008) 46:657–72. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20443

9. Slater S. The discovery of thyroid replacement therapy. Part 1: in the beginning. J R Soc Med. (2011) 104:15–8. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k050

10. Murray GR. Note on the treatment of myxoedema by hypodermic injections of an extract of the thyroid gland of a sheep. Br Med J. (1891) 2:796–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.1606.796

11. Slater S. (2011). The discovery of thyroid replacement therapy. Part 3: a complete transformation. J R Soc Med. 104:100–6. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k052

12. Kendall EC. The isolation in crystalline form of the compound containing iodin, which occurs in the thyroid its chemical nature and physiologic activity. JAMA. (1915) 250:2042–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.1915.02570510018005

13. Harington CR. Chemistry of thyroxine: constitution and synthesis of desiodo-thyroxine. Biochem J. (1926) 20:300–13. doi: 10.1042/bj0200300

14. Harington CR, Barger G. Chemistry of thyroxine: constitution and synthesis of thyroxine. Biochem J. (1927) 21:169–83. doi: 10.1042/bj0210169

15. Connolly KJ, Pharoah POD. Iodine Deficiency, Maternal Thyroxine Levels in Pregnancy and Developmental Disorders in the Children. New York, NY; Boston, MA: Springer. (1989).

16. Lamberg BA. Endemic goitre–iodine deficiency disorders. Ann Med. (1991) 23:367–72. doi: 10.3109/07853899109148075

17. Remaud S, Gothie JD, Morvan-Dubois G, Demeneix BA. Thyroid hormone signaling and adult neurogenesis in mammals. Front Endocrinol. (2014) 5:62. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00062

18. Calza L, Baldassarro VA, Fernandez M, Giuliani A, Lorenzini L, Giardino L. Thyroid hormone and the white matter of the central nervous system: from development to repair. Vitam Horm. (2018) 106:253–81. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2017.04.003

19. Fanibunda SE, Desouza LA, Kapoor R, Vaidya RA, Vaidya VA. Thyroid hormone regulation of adult neurogenesis. Vitam Horm. (2018) 106:211–51. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2017.04.006

20. Noda M. Thyroid hormone in the CNS: contribution of neuron-glia interaction. Vitam Horm. (2018) 106:313–31. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2017.05.005

21. Samuels HH, Tsai JS. Thyroid hormone action. Demonstration of similar receptors in isolated nuclei of rat liver and cultured GH1 cells. J Clin Invest. (1974) 53:656–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI107601

22. Bernal J, Pekonen F. Ontogenesis of the nuclear 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine receptor in the human fetal brain. Endocrinology. (1984) 114:677–9. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-2-677

23. Silva JE. Role of circulating thyroid hormones and local mechanisms in determining the concentration of T3 in various tissues. Prog Clin Biol Res. (1983) 116:23–44.

24. van Doorn J, van der Heide D, Roelfsema F. Sources and quantity of 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine in several tissues of the rat. J Clin Invest. (1983) 72:1778–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI111138

25. Chanoine JP, Braverman LE, Farwell AP, Safran M, Alex S, Dubord S, et al. The thyroid gland is a major source of circulating T3 in the rat. J Clin Invest. (1993) 91:2709–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI116510

26. van der Spek AH, Fliers E, Boelen A. The classic pathways of thyroid hormone metabolism. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2017) 458:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.01.025

27. Obregon MJ, Calvo RM, Del Rey FE, de Escobar GM. Ontogenesis of thyroid function and interactions with maternal function. Endocr Dev. (2007) 10:86–98. doi: 10.1159/000106821

28. Morreale de Escobar G, Obregon MJ, Escobar del Rey F. Is neuropsychological development related to maternal hypothyroidism or to maternal hypothyroxinemia? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2000) 85:3975–87. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6961

29. Calvo RM, Jauniaux E, Gulbis B, Asuncion M, Gervy C, Contempre B, et al. Fetal tissues are exposed to biologically relevant free thyroxine concentrations during early phases of development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2002) 87:1768–77. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8434

30. Guillaume J, Schussler GC, Goldman J. Components of the total serum thyroid hormone concentrations during pregnancy: high free thyroxine and blunted thyrotropin (TSH) response to TSH-releasing hormone in the first trimester. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1985) 60:678–84. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-4-678

31. Contempre B, Jauniaux E, Calvo R, Jurkovic D, Campbell S, de Escobar GM. Detection of thyroid hormones in human embryonic cavities during the first trimester of pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1993) 77:1719–22.

32. Fisher DA. Physiological variations in thyroid hormones: physiological and pathophysiological considerations. Clin Chem. (1996) 42:135–9.

33. Vulsma T, Gons MH, de Vijlder JJ. Maternal-fetal transfer of thyroxine in congenital hypothyroidism due to a total organification defect or thyroid agenesis. N Engl J Med. (1989) 321:13–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907063210103

34. Calvo R, Obregon MJ, Ruiz de Ona C, Escobar del Rey F, Morreale de Escobar G. Congenital hypothyroidism, as studied in rats. Crucial role of maternal thyroxine but not of 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine in the protection of the fetal brain. J Clin Invest. (1990) 86:889–99. doi: 10.1172/JCI114790

35. LaFranchi S. Thyroid function in the preterm infant. Thyroid. (1999) 9:71–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.71

36. Morreale de Escobar G, Obregon MJ, Escobar del Rey F. Role of thyroid hormone during early brain development. Eur J Endocrinol. (2004) 151(Suppl 3):U25–37. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.151u025

37. Darras VM, Van Herck SL. Iodothyronine deiodinase structure and function: from ascidians to humans. J Endocrinol. (2012) 215:189–206. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0204

38. Visser TJ, Schoenmakers CH. Characteristics of type III iodothyronine deiodinase. Acta Med Austriaca. (1992) 19(Suppl 1):18–21.

39. Visser TJ. Role of sulfation in thyroid hormone metabolism. Chem Biol Interact. (1994) 92:293–303. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90071-X

40. Williams GR, Bassett JH. Deiodinases: the balance of thyroid hormone: local control of thyroid hormone action: role of type 2 deiodinase. J Endocrinol. (2011) 209:261–72. doi: 10.1530/JOE-10-0448

41. Maia AL, Goemann IM, Meyer EL, Wajner SM. Deiodinases: the balance of thyroid hormone: type 1 iodothyronine deiodinase in human physiology and disease. J Endocrinol. (2011) 209:283–97. doi: 10.1530/JOE-10-0481

42. Campos-Barros A, Hoell T, Musa A, Sampaolo S, Stoltenburg G, Pinna G, et al. Phenolic and tyrosyl ring iodothyronine deiodination and thyroid hormone concentrations in the human central nervous system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1996) 81:2179–85.

43. Guadano-Ferraz A, Obregon MJ, St Germain DL, Bernal J. The type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase is expressed primarily in glial cells in the neonatal rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1997) 94:10391–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10391

44. Farwell AP, Dubord-Tomasetti SA, Pietrzykowski AZ, Stachelek SJ, Leonard JL. Regulation of cerebellar neuronal migration and neurite outgrowth by thyroxine and 3,3',5'-triiodothyronine. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. (2005) 154:121–35. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.07.016

45. Domingues JT, Cattani D, Cesconetto PA, Nascimento de Almeida BA, Pierozan P, Dos Santos K, et al. Reverse T3 interacts with αvβ3 integrin receptor and restores enzyme activities in the hippocampus of hypothyroid developing rats: insight on signaling mechanisms. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2018) 470:281–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.11.013

46. Bellusci L, Laurino A, Sabatini M, Sestito S, Lenzi P, Raimondi L, et al. New insights into the potential roles of 3-Iodothyronamine (T1AM) and newly developed thyronamine-like TAAR1 agonists in neuroprotection. Front Pharmacol. (2017) 8:905. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00905

47. Gachkar S, Oelkrug R, Martinez-Sanchez N, Rial-Pensado E, Warner A, Hoefig CS, et al. 3-Iodothyronamine induces tail vasodilation through central action in male mice. Endocrinology. (2017) 158:1977–84. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1951

48. Rutigliano G, Zucchi R. Cardiac actions of thyroid hormone metabolites. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2017) 458:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.01.003

49. Braunig J, Dinter J, Hofig CS, Paisdzior S, Szczepek M, Scheerer P, et al. The trace amine-associated receptor 1 Agonist 3-Iodothyronamine induces biased signaling at the serotonin 1b Receptor. Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:222. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00222

50. Braunig J, Mergler S, Jyrch S, Hoefig CS, Rosowski M, Mittag J, et al. 3-Iodothyronamine activates a set of membrane proteins in murine hypothalamic cell lines. Front Endocrinol. (2018) 9:523. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00523

51. Visser TJ. Role of sulfate in thyroid hormone sulfation. Eur J Endocrinol. (1996) 134:12–4. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1340012

52. Wu SY, Green WL, Huang WS, Hays MT, Chopra IJ. Alternate pathways of thyroid hormone metabolism. Thyroid. (2005) 15:943–58. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.943

53. Yamazoe Y, Nagata K, Ozawa S, Kato R. Structural similarity and diversity of sulfotransferases. Chem Biol Interact. (1994) 92:107–17. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90057-4

54. Spaulding SW, Smith TJ, Hinkle PM, Davis FB, Kung MP, Roth JA. Studies on the biological activity of triiodothyronine sulfate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1992) 74:1062–7.

55. Visser TJ, Mol JA, Otten MH. Rapid deiodination of triiodothyronine sulfate by rat liver microsomal fraction. Endocrinology. (1983) 112:1547–9. doi: 10.1210/endo-112-4-1547

56. Mol JA, Visser TJ. Synthesis and some properties of sulfate esters and sulfamates of iodothyronines. Endocrinology. (1985) 117:1–7. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-1-1

57. Visser TJ, Kaptein E, Terpstra OT, Krenning EP. Deiodination of thyroid hormone by human liver. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1988) 67:17–24. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-1-17

58. Moreno M, Berry MJ, Horst C, Thoma R, Goglia F, Harney JW, et al. Activation and inactivation of thyroid hormone by type I iodothyronine deiodinase. FEBS Lett. (1994) 344:143–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00365-3

59. Chopra IJ, Wu SY, Teco GN, Santini F. A radioimmunoassay for measurement of 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine sulfate: studies in thyroidal and nonthyroidal diseases, pregnancy, and neonatal life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1992) 75:189–94.

60. Wu S, Polk D, Wong S, Reviczky A, Vu R, Fisher DA. Thyroxine sulfate is a major thyroid hormone metabolite and a potential intermediate in the monodeiodination pathways in fetal sheep. Endocrinology. (1992) 131:1751–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.4.1396320

61. Wu SY, Huang WS, Polk D, Florsheim WH, Green WL, Fisher DA. Identification of thyroxine-sulfate (T4S) in human serum and amniotic fluid by a novel T4S radioimmunoassay. Thyroid. (1992) 2:101–5. doi: 10.1089/thy.1992.2.101

62. Polk DH, Reviczky A, Wu SY, Huang WS, Fisher DA. Metabolism of sulfoconjugated thyroid hormone derivatives in developing sheep. Am J Physiol. (1994) 266(6 Pt 1):E892–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.266.6.E892

63. Rutgers M, Bonthuis F, de Herder WW, Visser TJ. Accumulation of plasma triiodothyronine sulfate in rats treated with propylthiouracil. J Clin Invest. (1987) 80:758–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI113131

64. de Herder WW, Bonthuis F, Rutgers M, Otten MH, Hazenberg MP, Visser TJ. Effects of inhibition of type I iodothyronine deiodinase and phenol sulfotransferase on the biliary clearance of triiodothyronine in rats. Endocrinology. (1988) 122:153–7. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-1-153

65. Hazenberg MP, de Herder WW, Visser TJ. Hydrolysis of iodothyronine conjugates by intestinal bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. (1988) 4:9–16.

66. de Herder WW, Hazenberg MP, Pennock-Schroder AM, Oosterlaken AC, Rutgers M, Visser TJ. On the enterohepatic cycle of triiodothyronine in rats; importance of the intestinal microflora. Life Sci. (1989) 45:849–56. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90179-3

67. Rutgers M, Heusdens FA, Bonthuis F, de Herder WW, Hazenberg MP, Visser TJ. Enterohepatic circulation of triiodothyronine (T3) in rats: importance of the microflora for the liberation and reabsorption of T3 from biliary T3 conjugates. Endocrinology. (1989) 125:2822–30. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-6-2822

68. Santini F, Hurd RE, Chopra IJ. A study of metabolism of deaminated and sulfoconjugated iodothyronines by rat placental iodothyronine 5-monodeiodinase. Endocrinology. (1992) 131:1689–94. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.4.1396315

69. Santini F, Hurd RE, Lee B, Chopra IJ. Thyromimetic effects of 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine sulfate in hypothyroid rats. Endocrinology. (1993) 133:105–10. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.1.8319558

70. Kung MP, Spaulding SW, Roth JA. Desulfation of 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine sulfate by microsomes from human and rat tissues. Endocrinology. (1988) 122:1195–200. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-4-1195

71. Hays MT, Cavalieri RR. Deiodination and deconjugation of the glucuronide conjugates of the thyroid hormones by rat liver and brain microsomes. Metabolism. (1992) 41:494–7. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90207-Q

72. McLean TR, Rank MM, Smooker PM, Richardson SJ. Evolution of thyroid hormone distributor proteins. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2017) 459:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.02.038

73. Chanoine JP, Braverman LE. The role of transthyretin in the transport of thyroid hormone to cerebrospinal fluid and brain. Acta Med Austriaca. (1992) 19(Suppl 1):25–8.

74. Chang L, Munro SL, Richardson SJ, Schreiber G. Evolution of thyroid hormone binding by transthyretins in birds and mammals. Eur J Biochem. (1999) 259:534–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00076.x

75. Fleming CE, Nunes AF, Sousa MM. Transthyretin: more than meets the eye. Prog Neurobiol. (2009) 89:266–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.07.007

76. Benvenga S, Cahnmann H, Gregg R, Robbins J. Binding of thyroxine to human plasma low density lipoprotein through specific interaction with apolipoprotein B (apoB-100). Biochimie. (1989) 71:263–8. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(89)90063-1

77. Mendel CM, Weisiger RA, Jones AL, Cavalieri RR. Thyroid hormone-binding proteins in plasma facilitate uniform distribution of thyroxine within tissues: a perfused rat liver study. Endocrinology. (1987) 120:1742–9. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-5-1742

78. Mendel CM. The free hormone hypothesis: a physiologically based mathematical model. Endocr Rev. (1989) 10:232–74. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-3-232

79. Blondeau JP, Beslin A, Chantoux F, Francon J. Triiodothyronine is a high-affinity inhibitor of amino acid transport system L1 in cultured astrocytes. J Neurochem. (1993) 60:1407–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03302.x

80. Gao B, Hagenbuch B, Kullak-Ublick GA, Benke D, Aguzzi A, Meier PJ. Organic anion-transporting polypeptides mediate transport of opioid peptides across blood-brain barrier. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2000) 294:73–9.

81. Tamai I, Nezu J, Uchino H, Sai Y, Oku A, Shimane M, et al. Molecular identification and characterization of novel members of the human organic anion transporter (OATP) family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2000) 273:251–60. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2922

82. Friesema EC, Docter R, Moerings EP, Verrey F, Krenning EP, Hennemann G, et al. Thyroid hormone transport by the heterodimeric human system L amino acid transporter. Endocrinology. (2001) 142:4339–48. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8418

83. Fujiwara K, Adachi H, Nishio T, Unno M, Tokui T, Okabe M, et al. Identification of thyroid hormone transporters in humans: different molecules are involved in a tissue-specific manner. Endocrinology. (2001) 142:2005–12. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.5.8115

84. Ritchie JW, Taylor PM. Role of the system L permease LAT1 in amino acid and iodothyronine transport in placenta. Biochem J. (2001) 356(Pt 3):719–25. doi: 10.1042/bj3560719

85. Pizzagalli F, Hagenbuch B, Stieger B, Klenk U, Folkers G, Meier PJ. Identification of a novel human organic anion transporting polypeptide as a high affinity thyroxine transporter. Mol Endocrinol. (2002) 16:2283–96. doi: 10.1210/me.2001-0309

86. Friesema EC, Ganguly S, Abdalla A, Manning Fox JE, Halestrap AP, Visser TJ. Identification of monocarboxylate transporter 8 as a specific thyroid hormone transporter. J Biol Chem. (2003) 278:40128–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300909200

87. St-Pierre MV, Stallmach T, Freimoser Grundschober A, Dufour JF, Serrano MA, Marin JJ, et al. Temporal expression profiles of organic anion transport proteins in placenta and fetal liver of the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2004) 287:R1505–16. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00279.2003

88. Friesema EC, Jansen J, Milici C, Visser TJ. Thyroid hormone transporters. Vitam Horm. (2005) 70:137–67. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)70005-4

89. Huber RD, Gao B, Sidler Pfandler MA, Zhang-Fu W, Leuthold S, Hagenbuch B, et al. Characterization of two splice variants of human organic anion transporting polypeptide 3A1 isolated from human brain. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2007) 292:C795–806. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00597.2005

90. Friesema EC, Jansen J, Jachtenberg JW, Visser WE, Kester MH, Visser TJ. Effective cellular uptake and efflux of thyroid hormone by human monocarboxylate transporter 10. Mol Endocrinol. (2008) 22:1357–69. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0112

91. Wirth EK, Roth S, Blechschmidt C, Holter SM, Becker L, Racz I, et al. Neuronal 3',3,5-triiodothyronine (T3) uptake and behavioral phenotype of mice deficient in Mct8, the neuronal T3 transporter mutated in Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome. J Neurosci. (2009) 29:9439–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6055-08.2009

92. Kinne A, Kleinau G, Hoefig CS, Gruters A, Kohrle J, Krause G, et al. Essential molecular determinants for thyroid hormone transport and first structural implications for monocarboxylate transporter 8. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:28054–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.129577

93. Braun D, Kinne A, Brauer AU, Sapin R, Klein MO, Kohrle J, et al. Developmental and cell type-specific expression of thyroid hormone transporters in the mouse brain and in primary brain cells. Glia. (2011) 59:463–71. doi: 10.1002/glia.21116

94. Kinne A, Schulein R, Krause G. Primary and secondary thyroid hormone transporters. Thyroid Res. (2011) 4(Suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/1756-6614-4-S1-S7

95. Svoboda M, Riha J, Wlcek K, Jaeger W, Thalhammer T. Organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs): regulation of expression and function. Curr Drug Metab. (2011) 12:139–53. doi: 10.2174/138920011795016863

96. Visser WE, Friesema EC, Visser TJ. Minireview: thyroid hormone transporters: the knowns and the unknowns. Mol Endocrinol. (2011) 25:1–14. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0095

97. Loubiere LS, Vasilopoulou E, Glazier JD, Taylor PM, Franklyn JA, Kilby MD, et al. Expression and function of thyroid hormone transporters in the microvillous plasma membrane of human term placental syncytiotrophoblast. Endocrinology. (2012) 153:6126–35. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1753

98. Muller J, Heuer H. Expression pattern of thyroid hormone transporters in the postnatal mouse brain. Front Endocrinol. (2014) 5:92. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00092

99. Sun YN, Liu YJ, Zhang L, Ye Y, Lin LX, Li YM, et al. Expression of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1c1 and monocarboxylate transporter 8 in the rat placental barrier and the compensatory response to thyroid dysfunction. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e96047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096047

100. Gaccioli F, Aye IL, Roos S, Lager S, Ramirez VI, Kanai Y, et al. Expression and functional characterisation of System L amino acid transporters in the human term placenta. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2015) 13:57. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0054-8

101. Zevenbergen C, Meima ME, Lima de Souza EC, Peeters RP, Kinne A, Krause G, et al. Transport of Iodothyronines by human L-type amino acid transporters. Endocrinology. (2015) 156:4345–55. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1140

102. Wasco EC, Martinez E, Grant KS, St Germain EA, St Germain DL, Galton VA. Determinants of iodothyronine deiodinase activities in rodent uterus. Endocrinology. (2003) 144:4253–61. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0490

103. Anselmo J, Cao D, Karrison T, Weiss RE, Refetoff S. Fetal loss associated with excess thyroid hormone exposure. JAMA. (2004) 292:691–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.6.691

104. Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Fiering S, Galton VA, St Germain D. Type 3 deiodinase is critical for the maturation and function of the thyroid axis. J Clin Invest. (2006) 116:476–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI26240

105. Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Liao XH, Van Sande J, Refetoff S, Galton VA, et al. Type 3 deiodinase deficiency results in functional abnormalities at multiple levels of the thyroid axis. Endocrinology. (2007) 148:5680–7. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0652

106. Salvatore D, Low SC, Berry M, Maia AL, Harney JW, Croteau W, et al. Type 3 lodothyronine deiodinase: cloning, in vitro expression, and functional analysis of the placental selenoenzyme. J Clin Invest. (1995) 96:2421–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI118299

107. Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, Larsen PR. Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocr Rev. (2002) 23:38–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0455

108. Gereben B, Zeold A, Dentice M, Salvatore D, Bianco AC. Activation and inactivation of thyroid hormone by deiodinases: local action with general consequences. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2008) 65:570–90. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7396-0

109. Sawin S, Brodish P, Carter CS, Stanton ME, Lau C. Development of cholinergic neurons in rat brain regions: dose-dependent effects of propylthiouracil-induced hypothyroidism. Neurotoxicol Teratol. (1998) 20:627–35. doi: 10.1016/S0892-0362(98)00020-8

110. Stanley EL, Hume R, Visser TJ, Coughtrie MW. Differential expression of sulfotransferase enzymes involved in thyroid hormone metabolism during human placental development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2001) 86:5944–55. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8081

111. Wirth EK, Schweizer U, Kohrle J. Transport of thyroid hormone in brain. Front Endocrinol. (2014) 5:98. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00098

112. Escriva H, Manzon L, Youson J, Laudet V. Analysis of lamprey and hagfish genes reveals a complex history of gene duplications during early vertebrate evolution. Mol Biol Evol. (2002) 19:1440–50. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004207

113. Dehal P, Boore JL. Two rounds of whole genome duplication in the ancestral vertebrate. PLoS Biol. (2005) 3:e314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030314

114. Flamant F, Baxter JD, Forrest D, Refetoff S, Samuels H, Scanlan TS, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LIX The pharmacology and classification of the nuclear receptor superfamily: thyroid hormone receptors. Pharmacol Rev. (2006) 58:705–11. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.3

115. Harvey CB, Williams GR. Mechanism of thyroid hormone action. Thyroid. (2002) 12:441–6. doi: 10.1089/105072502760143791

116. Williams GR. Cloning and characterization of two novel thyroid hormone receptor beta isoforms. Mol Cell Biol. (2000) 20:8329–42. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.22.8329-8342.2000

117. Cheng SY, Leonard JL, Davis PJ. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev. (2010) 31:139–70. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0007

118. Chassande O, Fraichard A, Gauthier K, Flamant F, Legrand C, Savatier P, et al. Identification of transcripts initiated from an internal promoter in the c-erbA alpha locus that encode inhibitors of retinoic acid receptor-alpha and triiodothyronine receptor activities. Mol Endocrinol. (1997) 11:1278–90.

119. Salto C, Kindblom JM, Johansson C, Wang Z, Gullberg H, Nordstrom K, et al. Ablation of TRalpha2 and a concomitant overexpression of alpha1 yields a mixed hypo- and hyperthyroid phenotype in mice. Mol Endocrinol. (2001) 15:2115–28. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.12.0750

120. Davis PJ, Leonard JL, Lin HY, Leinung M, Mousa SA. Molecular basis of nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Vitam Horm. (2018) 106:67–96. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2017.06.001

121. Yang Z, Privalsky ML. Isoform-specific transcriptional regulation by thyroid hormone receptors: hormone-independent activation operates through a steroid receptor mode of co-activator interaction. Mol Endocrinol. (2001) 15:1170–85. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.7.0656

122. Lee S, Young BM, Wan W, Chan IH, Privalsky ML. A mechanism for pituitary-resistance to thyroid hormone (PRTH) syndrome: a loss in cooperative coactivator contacts by thyroid hormone receptor (TR)beta2. Mol Endocrinol. (2011) 25:1111–25. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0448

123. Rastinejad F, Perlmann T, Evans RM, Sigler PB. Structural determinants of nuclear receptor assembly on DNA direct repeats. Nature. (1995) 375:203–11. doi: 10.1038/375203a0

124. Schueler PA, Schwartz HL, Strait KA, Mariash CN, Oppenheimer JH. Binding of 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine (T3) and its analogs to the in vitro translational products of c-erbA protooncogenes: differences in the affinity of the alpha- and beta-forms for the acetic acid analog and failure of the human testis and kidney alpha-2 products to bind T3. Mol Endocrinol. (1990) 4:227–34. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-2-227

125. Velasco LF, Togashi M, Walfish PG, Pessanha RP, Moura FN, Barra GB, et al. Thyroid hormone response element organization dictates the composition of active receptor. J Biol Chem. (2007) 282:12458–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610700200

126. Schroeder A, Jimenez R, Young B, Privalsky ML. The ability of thyroid hormone receptors to sense t4 as an agonist depends on receptor isoform and on cellular cofactors. Mol Endocrinol. (2014) 28:745–57. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1335

127. Gil-Ibanez P, Belinchon MM, Morte B, Obregon MJ, Bernal J. Is the intrinsic genomic activity of thyroxine relevant in vivo? Effects on gene expression in primary cerebrocortical and neuroblastoma cells. Thyroid. (2017) 27:1092–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0024

128. Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. (2000) 14:121–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.14.2.121

129. Castelo-Branco G, Lilja T, Wallenborg K, Falcao AM, Marques SC, Gracias A, et al. Neural stem cell differentiation is dictated by distinct actions of nuclear receptor corepressors and histone deacetylases. Stem Cell Rep. (2014) 3:502–15. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.07.008

130. Hashimoto K, Curty FH, Borges PP, Lee CE, Abel ED, Elmquist JK, et al. An unliganded thyroid hormone receptor causes severe neurological dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2001) 98:3998–4003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051454698

131. Venero C, Guadano-Ferraz A, Herrero AI, Nordstrom K, Manzano J, de Escobar GM, et al. Anxiety, memory impairment, and locomotor dysfunction caused by a mutant thyroid hormone receptor alpha1 can be ameliorated by T3 treatment. Genes Dev. (2005) 19:2152–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.346105

132. Wallis K, Sjogren M, van Hogerlinden M, Silberberg G, Fisahn A, Nordstrom K, et al. Locomotor deficiencies and aberrant development of subtype-specific GABAergic interneurons caused by an unliganded thyroid hormone receptor alpha1. J Neurosci. (2008) 28:1904–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5163-07.2008

133. Rentoumis A, Chatterjee VK, Madison LD, Datta S, Gallagher GD, Degroot LJ, et al. Negative and positive transcriptional regulation by thyroid hormone receptor isoforms. Mol Endocrinol. (1990) 4:1522–31. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-10-1522

134. Hernandez A, Morte B, Belinchon MM, Ceballos A, Bernal J. Critical role of types 2 and 3 deiodinases in the negative regulation of gene expression by T(3)in the mouse cerebral cortex. Endocrinology. (2012) 153:2919–28. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1905

135. Chatonnet F, Flamant F, Morte B. A temporary compendium of thyroid hormone target genes in brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2015) 1849:122–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.05.023

136. Aranda A, Alonso-Merino E, Zambrano A. Receptors of thyroid hormones. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. (2013) 11:2–13.

137. Flamant F, Gauthier K. Thyroid hormone receptors: the challenge of elucidating isotype-specific functions and cell-specific response. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2013) 1830:3900–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.06.003

138. Astapova I. Role of co-regulators in metabolic and transcriptional actions of thyroid hormone. J Mol Endocrinol. (2016) 56:73–97. doi: 10.1530/JME-15-0246

139. Iskaros J, Pickard M, Evans I, Sinha A, Hardiman P, Ekins R. Thyroid hormone receptor gene expression in first trimester human fetal brain. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2000) 85:2620–3. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.7.6766

140. Kilby MD, Gittoes N, McCabe C, Verhaeg J, Franklyn JA. Expression of thyroid receptor isoforms in the human fetal central nervous system and the effects of intrauterine growth restriction. Clin Endocrinol. (2000) 53:469–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01074.x

141. Perez-Castillo A, Bernal J, Ferreiro B, Pans T. The early ontogenesis of thyroid hormone receptor in the rat fetus. Endocrinology. (1985) 117:2457–61. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-6-2457

142. Ferreiro B, Bernal J, Goodyer CG, Branchard CL. Estimation of nuclear thyroid hormone receptor saturation in human fetal brain and lung during early gestation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1988) 67:853–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-4-853

143. Bradley DJ, Young WS III, Weinberger C. Differential expression of alpha and beta thyroid hormone receptor genes in rat brain and pituitary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1989) 86:7250–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7250

144. Mellstrom B, Naranjo JR, Santos A, Gonzalez AM, Bernal J. Independent expression of the alpha and β c-erbA genes in developing rat brain. Mol Endocrinol. (1991) 5:1339–50. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-9-1339

145. Bradley DJ, Towle HC, Young WS III. Spatial and temporal expression of alpha- and beta-thyroid hormone receptor mRNAs, including the beta 2-subtype, in the developing mammalian nervous system. J Neurosci. (1992) 12:2288–302. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02288.1992

146. Manzano J, Morte B, Scanlan TS, Bernal J. Differential effects of triiodothyronine and the thyroid hormone receptor beta-specific agonist GC-1 on thyroid hormone target genes in the b ain. Endocrinology. (2003) 144:5480–7. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0633

147. Napolitano F, D'Angelo L, de Girolamo P, Avallone L, de Lange P, Usiello A. The Thyroid Hormone-target gene rhes a novel crossroad for neurological and psychiatric disorders: new insights from animal models. Neuroscience. (2018) 384:419–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.05.027

148. Jones I, Srinivas M, Ng L, Forrest D. The thyroid hormone receptor beta gene: structure and functions in the brain and sensory systems. Thyroid. (2003) 13:1057–68. doi: 10.1089/105072503770867228

149. Guadano-Ferraz A, Benavides-Piccione R, Venero C, Lancha C, Vennstrom B, Sandi C, et al. Lack of thyroid hormone receptor alpha1 is associated with selective alterations in behavior and hippocampal circuits. Mol Psychiatry. (2003) 8:30–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001196

150. Strait KA, Schwartz HL, Seybold VS, Ling NC, Oppenheimer JH. Immunofluorescence localization of thyroid hormone receptor protein beta 1 and variant alpha 2 in selected tissues: cerebellar Purkinje cells as a model for beta 1 receptor-mediated developmental effects of thyroid hormone in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1991) 88:3887–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3887

151. Forrest D, Hanebuth E, Smeyne RJ, Everds N, Stewart CL, Wehner JM, et al. Recessive resistance to thyroid hormone in mice lacking thyroid hormone receptor beta: evidence for tissue-specific modulation of receptor function. EMBO J. (1996) 15:3006–15. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00664.x

152. Wong R, Vasilyev VV, Ting YT, Kutler DI, Willingham MC, Weintraub BD, et al. Transgenic mice bearing a human mutant thyroid hormone beta 1 receptor manifest thyroid function anomalies, weight reduction, and hyperactivity. Mol Med. (1997) 3:303–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03401809

153. Gothe S, Wang Z, Ng L, Kindblom JM, Barros AC, Ohlsson C, et al. Mice devoid of all known thyroid hormone receptors are viable but exhibit disorders of the pituitary-thyroid axis, growth, and bone maturation. Genes Dev. (1999) 13:1329–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1329

154. Dellovade TL, Chan J, Vennstrom B, Forrest D, Pfaff DW. The two thyroid hormone receptor genes have opposite effects on estrogen-stimulated sex behaviors. Nat Neurosci. (2000) 3:472–5. doi: 10.1038/74846

155. Tinnikov A, Nordstrom K, Thoren P, Kindblom JM, Malin S, Rozell B, et al. Retardation of post-natal development caused by a negatively acting thyroid hormone receptor alpha1. EMBO J. (2002) 21:5079–87. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf523

156. Flamant F, Poguet AL, Plateroti M, Chassande O, Gauthier K, Streichenberger N, et al. Congenital hypothyroid Pax8(-/-) mutant mice can be rescued by inactivating the TRalpha gene. Mol Endocrinol. (2002) 16:24–32. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0766

157. Peeters RP, Hernandez A, Ng L, Ma M, Sharlin DS, Pandey M, et al. Cerebellar abnormalities in mice lacking type 3 deiodinase and partial reversal of phenotype by deletion of thyroid hormone receptor α1. Endocrinology. (2013) 154:550–61. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1738

158. Williams GR. Neurodevelopmental and neurophysiological actions of thyroid hormone. J Neuroendocrinol. (2008) 20:784–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01733.x

159. Dillman AA, Hauser DN, Gibbs JR, Nalls MA, McCoy MK, Rudenko IN, et al. mRNA expression, splicing and editing in the embryonic and adult mouse cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci. (2013) 16:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nn.3332

160. Gil-Ibanez P, Garcia-Garcia F, Dopazo J, Bernal J, Morte B. Global transcriptome analysis of primary cerebrocortical cells: identification of genes regulated by triiodothyronine in specific cell types. Cereb Cortex. (2017) 27:706–17. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv273

161. Siegrist-Kaiser CA, Juge-Aubry C, Tranter MP, Ekenbarger DM, Leonard JL. Thyroxine-dependent modulation of actin polymerization in cultured astrocytes. A novel, extranuclear action of thyroid hormone. J Biol Chem. (1990) 265:5296–302.

162. Farwell AP, Dubord-Tomasetti SA, Pietrzykowski AZ, Leonard JL. Dynamic nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone in the developing rat brain. Endocrinology. (2006) 147:2567–74. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1272

163. Menegaz D, Royer C, Rosso A, Souza AZ, Santos AR, Silva FR. Rapid stimulatory effect of thyroxine on plasma membrane transport systems: calcium uptake and neutral amino acid accumulation in immature rat testis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2010) 42:1046–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.03.015

164. Cao X, Kambe F, Moeller LC, Refetoff S, Seo H. Thyroid hormone induces rapid activation of Akt/protein kinase B-mammalian target of rapamycin-p70S6K cascade through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in human fibroblasts. Mol Endocrinol. (2005) 19:102–12. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0093

165. Sayre NL, Lechleiter JD. Fatty acid metabolism and thyroid hormones. Curr Trends Endocinol. (2012) 6:65–76.

166. Kalyanaraman H, Schwappacher R, Joshua J, Zhuang S, Scott BT, Klos M, et al. Nongenomic thyroid hormone signaling occurs through a plasma membrane-localized receptor. Sci Signal. (2014) 7:ra48. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004911

167. Bergh JJ, Lin HY, Lansing L, Mohamed SN, Davis FB, Mousa S, et al. Integrin alphaVbeta3 contains a cell surface receptor site for thyroid hormone that is linked to activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and induction of angiogenesis. Endocrinology. (2005) 146:2864–71. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0102

168. Cody V, Davis PJ, Davis FB. Molecular modeling of the thyroid hormone interactions with alpha v beta 3 integrin. Steroids. (2007) 72:165–70. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.11.008

169. Hoffman SJ, Vasko-Moser J, Miller WH, Lark MW, Gowen M, Stroup G. Rapid inhibition of thyroxine-induced bone resorption in the rat by an orally active vitronectin receptor antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2002) 302:205–11. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.205

170. Hercbergs A, Mousa SA, Davis PJ. Nonthyroidal illness syndrome and thyroid hormone actions at integrin αvβ3. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2018) 103:1291–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01939

171. Mousa SA, Glinsky GV, Lin HY, Ashur-Fabian O, Hercbergs A, Keating KA, et al. Contributions of thyroid hormone to cancer metastasis. Biomedicines. (2018) 6:E89. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6030089

172. Stenzel D, Wilsch-Brauninger M, Wong FK, Heuer H, Huttner WB. Integrin αvβ3 and thyroid hormones promote expansion of progenitors in embryonic neocortex. Development. (2014) 141:795–806. doi: 10.1242/dev.101907

173. Desouza LA, Sathanoori M, Kapoor R, Rajadhyaksha N, Gonzalez LE, Kottmann AH, et al. Thyroid hormone regulates the expression of the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway in the embryonic and adult Mammalian brain. Endocrinology. (2011) 152:1989–2000. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1396

174. Wang Y, Wang Y, Dong J, Wei W, Song B, Min H, et al. Developmental hypothyroxinemia and hypothyroidism reduce proliferation of cerebellar granule neuron precursors in rat offspring by downregulation of the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. Mol Neurobiol. (2014) 49:1143–52. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8587-3

175. Kogai T, Liu YY, Richter LL, Mody K, Kagechika H, Brent GA. Retinoic acid induces expression of the thyroid hormone transporter, monocarboxylate transporter 8 (Mct8). J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:27279–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123158

176. Anderson GW, Larson RJ, Oas DR, Sandhofer CR, Schwartz HL, Mariash CN, et al. Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor (COUP-TF) modulates expression of the Purkinje cell protein-2 gene. A potential role for COUP-TF in repressing premature thyroid hormone action in the developing brain. J Biol Chem. (1998) 273:16391–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16391