- 1Department of Clinical Neuroendocrinology, Max Planck Institut für Psychiatrie, Munich, Germany

- 2Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands

- 3Department of Medicine, Division of Neurosurgery, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands

Background: Quality of life (QoL) in patients with acromegaly is reduced irrespective of disease state. The contributions of multifactorial determinants of QoL in several disease stages are presently not well known.

Objective: To systematically review predictors of QoL in acromegalic patients.

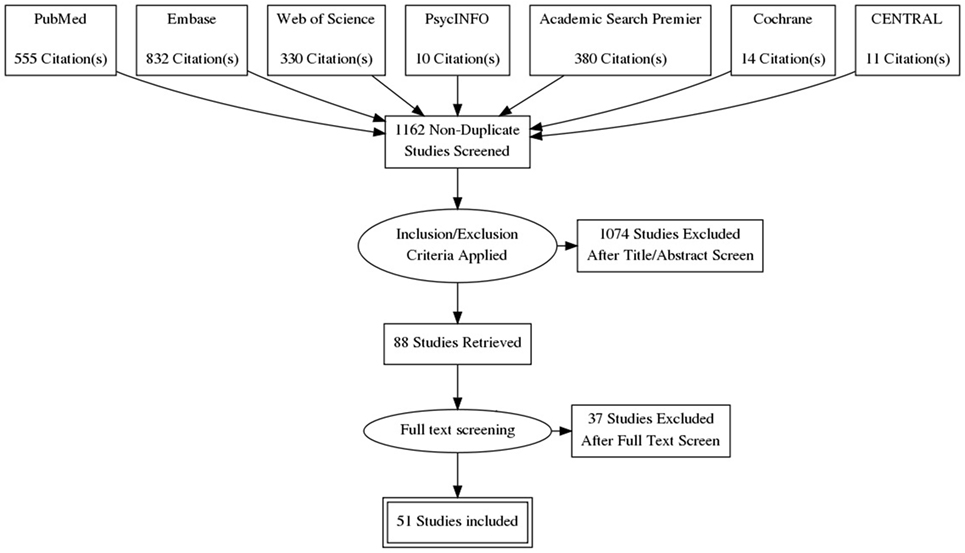

Methods: Main databases were systematically searched using predefined search terms for potentially relevant articles up to January 2017. Inclusion criteria included separate acromegaly cohort, non-hereditary acromegaly, QoL as study parameter with clearly described method of measurement and quantitative results, N ≥ 10 patients, article in English and adult patients only. Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers; studies were included using the PRISMA flow diagram.

Results: We identified 1,162 studies; 51 studies met the inclusion criteria: 31 cross-sectional observational studies [mean AcroQoL score 62.7 (range 46.6–87.0, n = 1,597)], 9 had a longitudinal component [mean baseline AcroQoL score 61.4 (range 54.3–69.0, n = 386)], and 15 were intervention studies [mean baseline AcroQoL score 58.6 (range 52.2–75.3, n = 521)]. Disease-activity reflected by biochemical control measures yielded mixed, and therefore inconclusive results with respect to their effect on QoL. Addition of pegvisomant to somatostatin analogs and start of lanreotide autogel resulted in improvement in QoL. Data from intervention studies on other treatment modalities were too limited to draw conclusions on the effects of these modalities on QoL. Interestingly, higher BMI and greater degree of depression showed consistently negative associations with QoL. Hypopituitarism was not significantly correlated with QoL in acromegaly.

Conclusion: At present, there is insufficient published data to support that biochemical control, or treatment of acromegaly in general, is associated with improved QoL. Studies with somatostatin receptor ligand treatment, i.e., particularly lanreotide autogel and pegvisomant have shown improved QoL, but consensus on the correlation with biochemical control is missing. Longitudinal studies investigating predictors in treatment-naive patients and their follow-up after therapeutic interventions are lacking but are urgently needed. Other factors, i.e., depression and obesity were identified from cross-sectional cohort studies as consistent factors associated with poor QoL. Perhaps treatment strategies of acromegaly patients should not only focus on normalizing biochemical markers but emphasize improvement of QoL by alternative interventions such as psychosocial or weight lowering interventions.

Introduction

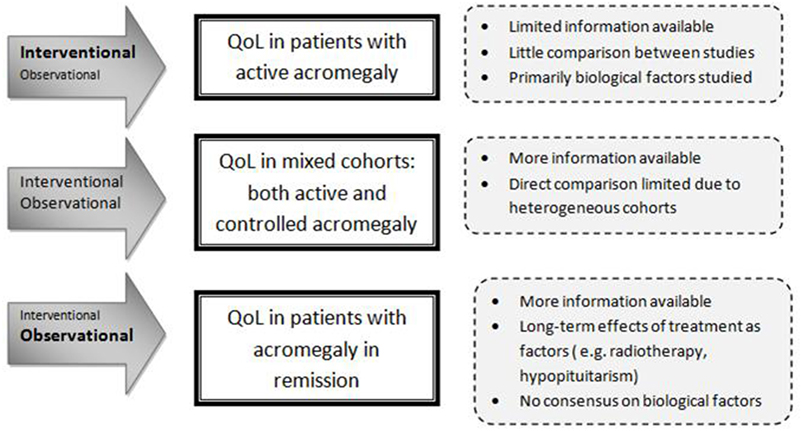

The World Health Organization recognizes three patient-related health outcome goals in chronic disease management: reducing mortality, reducing morbidity, and improving quality of life (QoL) (1). QoL is a multidimensional entity that represents the functional effect of an illness and its consequent therapy upon a patient, as perceived by the patient (2). The initial focus on reducing mortality and improving morbidity as well as normalizing biochemical target values, i.e., IGF-I and growth hormone (GH), in patients with acromegaly has yielded successful results (3–5). Nevertheless, QoL remains a major concern, since it often remains reduced despite long-term biochemical cure (6). In both patients with active or controlled acromegaly, QoL has been reported to be markedly decreased relative to the normal population, with some improvement after treatment. Studies, usually cross-sectional designed because of the rarity of the disease, have been exploring disease-related and general factors (e.g., age, gender) that can affect QoL of patients with acromegaly. These studies included rather heterogeneous groups of patients with acromegaly (in terms of disease stages, extent of disease control, and treatment history) (7, 8). Literature reports conflicting results about factors that affect QoL. For example, a number of studies found no correlation between biochemical control of acromegaly and QoL (9–11), whereas others reported a significant correlation (12, 13). A more consistent finding during long-term follow-up of acromegaly patients is the high prevalence of joint complaints, fatigue, and (neuro)psychological problems. There is increasing evidence that in patients with acromegaly an initial period of GH excess can cause permanent complications, despite long-term cure. This has been shown, e.g., with structural changes in macroscopic brain architecture, irreversible radiological joint abnormalities, and body composition (14–18). As QoL in the general sense is a multifactorial entity, it is plausible to assume that QoL in patients with acromegaly is also determined by several factors, which may differ depending on the phase of the disease. Factors that may be of importance during the untreated phase of the disease (i.e., active disease) are not necessarily of equal importance during the early treatment phase (i.e., transition from active to controlled disease) and the subsequent phase of acromegaly in chronic-treated situation (usually remission). It is important to acknowledge different study designs and the timing of the QoL measurement in relation to the disease phase, and lack of available data when analyzing factors associated with QoL in acromegaly. For example, interventional studies focus predominantly on active or treatment-naïve patients. A limited number of longitudinal observational studies have included patients with changing disease status. Long-term effects of treatment, such as post-radiation effects or hypopituitarism, are inherent to treated acromegaly and will have a more prominent role than in active acromegaly. Cohorts including patients with both active and controlled disease are therefore particularly heterogeneous, limiting direct comparison (see also Figure 1). Based on evidence based medicine, it is crucial to identify which factors are most influential on QoL during a certain phase of the disease in order to develop suitable interventions aimed at improving QoL. Therefore, the aim of this systematic literature study was to evaluate predictors of QoL in patients with acromegaly in several stages of their diseases and to identify potentially modifiable factors as targets for interventions.

Methods

This systematic review aimed to adhere to the current PRISMA guidelines (19).

Data Sources and Search

Seven electronic databases were searched for potentially relevant articles. PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Academic Search Premier, COCHRANE, and CENTRAL were searched using the keywords “Pituitary Neoplasms,” “Pituitary Neoplasm,” “Pituitary Tumors,” “Pituitary Tumor,” “Pituitary Tumours,” “Pituitary Tumour,” “Pituitary Adenomas,” “Pituitary Adenoma,” “Growth Hormone-Secreting Pituitary Adenoma,” “Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas,” “Acromegaly,” “Quality of Life,” “Life quality,” “qol,” “daily functioning,” “daily routine,” health related QoL,” “well-being,” and “wellbeing.”

Study Selection

Articles were retrieved based on analysis of title and abstract whether they met the following six inclusion criteria: (1) separate acromegaly cohort, (2) non-hereditary acromegaly, (3) QoL as parameter, with clearly described method of measurement and quantitative results, (4) N ≥ 10 patients, (5) article in English, and (6) adult patients only.

Articles detailing cohorts detailing growth hormone deficiency (GHD) after acromegaly were considered a separate entity and excluded from the analysis. Studies based on similar cohorts were separately included.

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

Screening of potentially suitable articles, as well as assessing eligibility, was performed by two independent reviewers. Inclusion in the final systematic review was done upon mutual agreement.

Information about the study size, origin of the patients, outcome, and potential conflicts of interest were extracted from each study.

Only factors that were described in more than one article were included for the systematic review part. Factors were scored having (1) no significant association with QoL, (2) a significant association with a subscale of the QoL-instrument (positive- or negative association), or (3) a significant association with the total QoL-instrument (positive- or negative association). Results were stratified into general factors, disease-specific factors, or interventions inherently linked to acromegaly. Consensus was determined as all studies unidirectionally described.

Quality of the selected articles was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for cohort studies/case control studies (20). The maximum score for each article was 4 stars for the item “selection,” 2 stars for the item “comparability,” and 3 stars for either the item “outcome” or “exposure,” respectively.

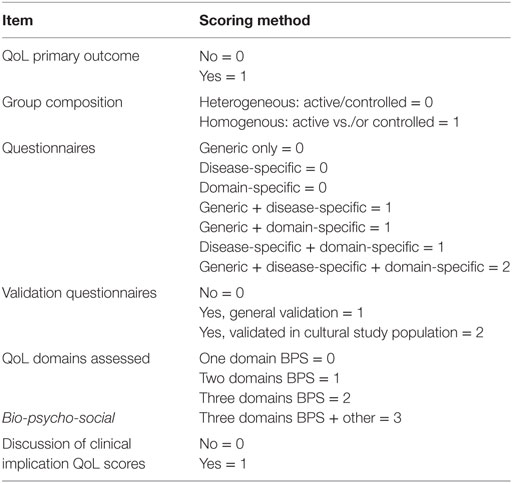

A customized evaluation tool (see Table 1) was drafted by our research group and used to determine the quality of QoL assessment specifically, with a maximum of 10 points. This tool comprises biological, psychological, and social elements of a patients’ QoL and further differentiates between generic and disease-specific QoL, allowing for both a global QoL assessment and a specific design (e.g., AcroQoL).

Results

Search Results and Study Characteristics

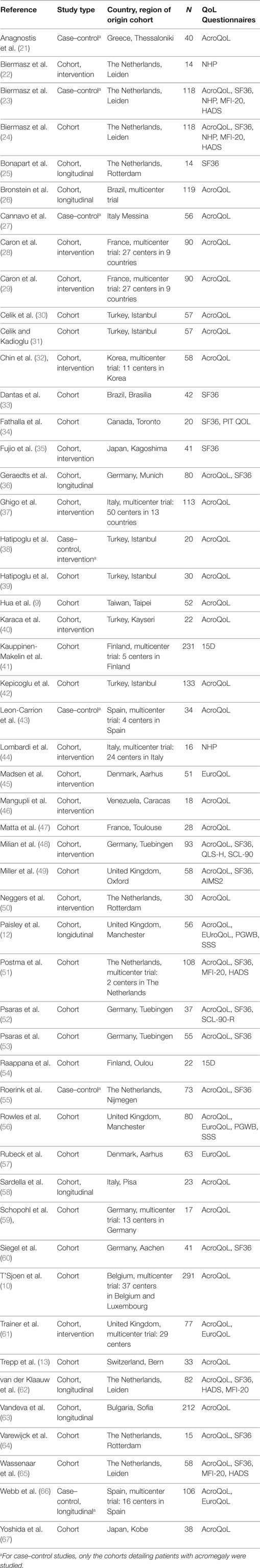

The search yielded 1,162 articles, of which 1,074 were excluded based on the title and abstract. The 88 remaining studies were checked for the aforementioned inclusion criteria; 15 of these studies were excluded on the basis of no description of predictors of QoL, and another 9 studies because the patients had been diagnosed with GHD after treatment for acromegaly. Fifty-one studies were ultimately included (see also Figure 2): 8 case–control studies and 43 cohort studies. Naturally, for the case–control studies, only the cohorts of patients with acromegaly were studied in this review. Thirty-one studies were classified as cross-sectional observational studies, 9 had an observational longitudinal component, and 15 studies were intervention studies. The selected studies, as well as abstracted data, are shown in Table 2.

Baseline AcroQol-Scores

Eighty percent of studies used the disease-specific measurement instrument AcroQoL (n = 41). Mean AcroQoL scores in cross-sectional studies were 62.7 (range 46.6–87.0, n = 1597, maximum score = 100). Baseline mean AcroQoL scores in longitudinal studies were of 61.4 (range 54.3–69.0, n = 386), and 58.6 (range 52.2–75.3, n = 521) in intervention studies. Given the heterogeneity of the individual studies, no formal conclusions can be drawn as to whether the means of the different study types are statistically different.

Quality Assessment

The quality assessment with regard to general quality (NOS) and specific QoL quality can be found in Table S1 in Supplementary Material. Five studies were classified as high quality studies (NOS ≥ 8), 33 studies were classified as medium quality studies (NOS 6-7), and 13 studies were classified as low quality studies (NOS ≤ 5). Quality of QoL assessment was high in 12 studies (≥9 points), medium in 25 studies (6–8 points), and low in 14 studies (≤5 points).

Described Factors/Interventions

Disease-specific factors that were identified from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies were biochemical control (n = 23), IGF1 (n = 17), GH (n = 11), hypopituitarism (n = 10), disease duration (n = 8), tumor size (n = 5), duration of remission (n = 4), nadir GH (n = 3), change in IGF1 (n = 2), and follow-up duration (n = 2). General predictors that were identified were age (n = 16), gender (n = 14), depression scores (n = 7), education (n = 5), BMI (n = 2), and physical activity (n = 2). (Retrospective) Interventions identified from cross-sectional studies were a history of radiotherapy (n = 15), surgery (n = 8), current use of somatostatin analogs (n = 4), and application of any treatment of acromegaly (not otherwise specified) (n = 2).

Interventions identified from intervention trials (QoL measured in patients with acromegaly before and after intervention) were somatostatin analogs (n = 8), pegvisomant (n = 3), and pituitary surgery (n = 3).

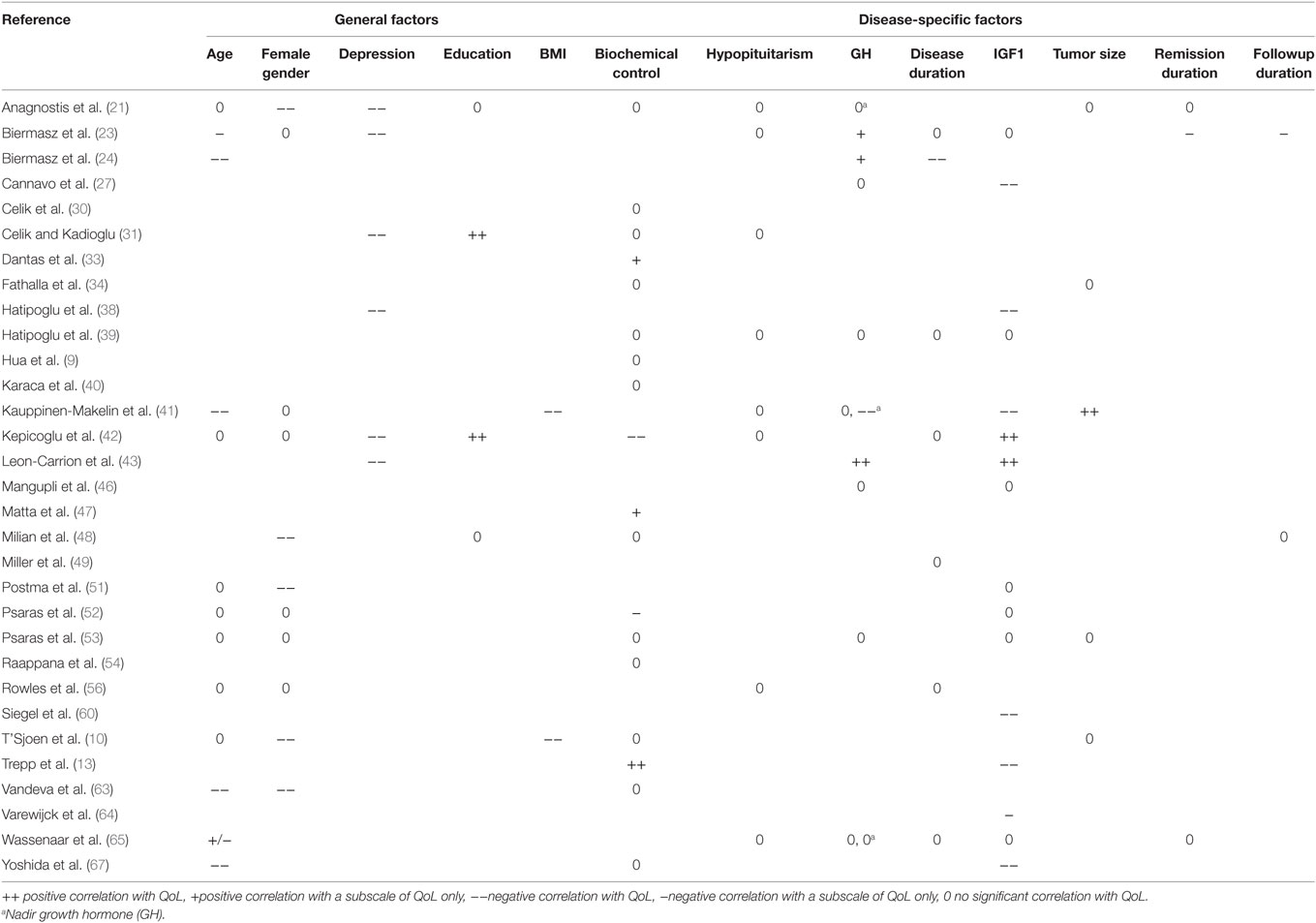

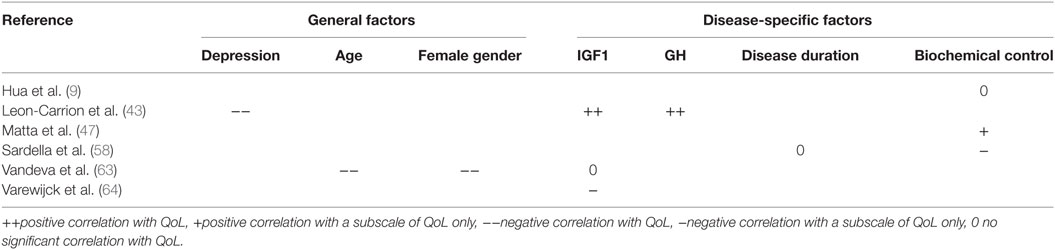

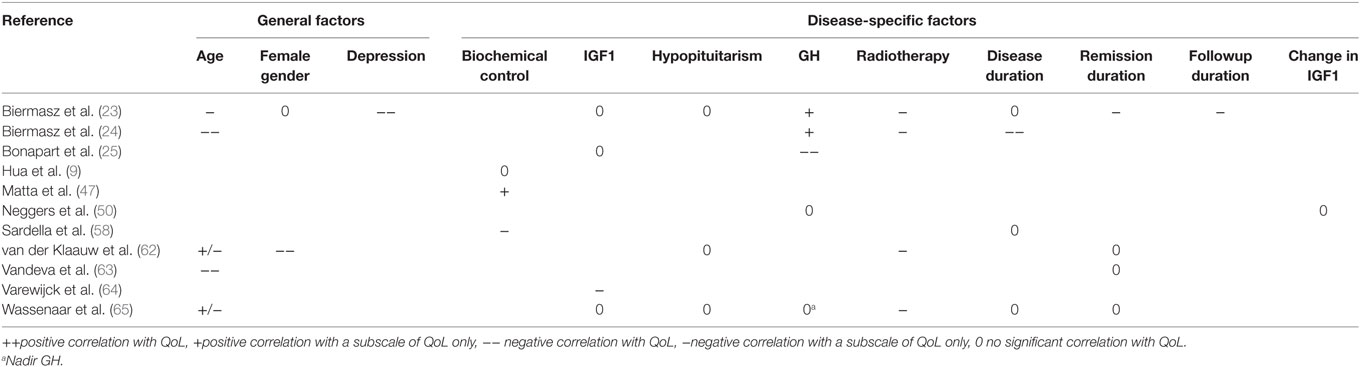

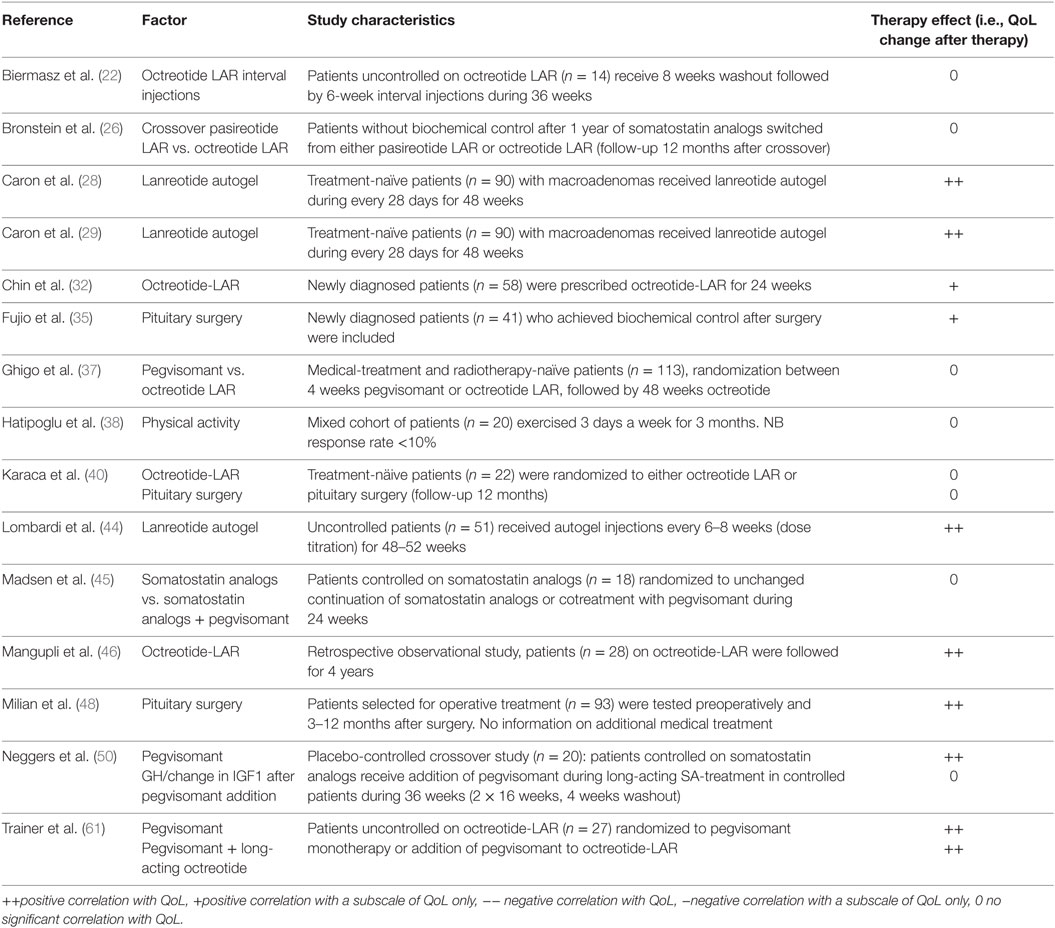

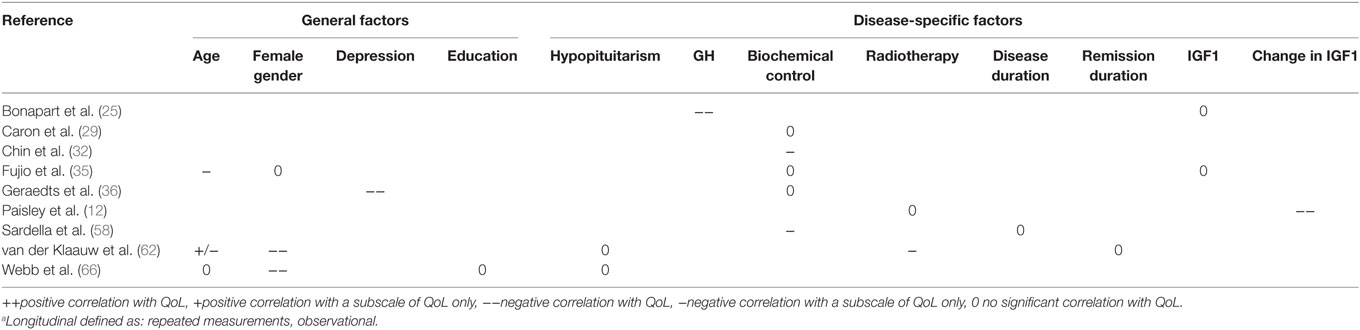

Results indicating whether a factor was described to have a significant positive, significant negative, or no significant effect are denoted in Table 3 for general and disease-specific factors, and in Table 4 for applied interventions (therapies).

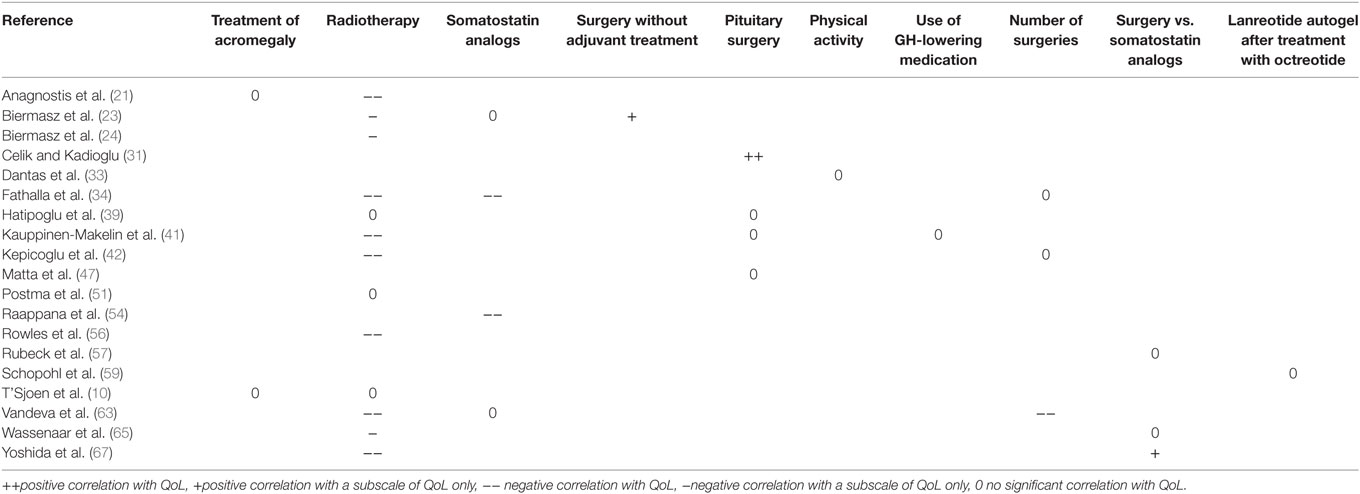

Table 4. Factors influencing QoL in acromegaly in cross-sectional observational studies (previous and ongoing interventions).

Results from Cross-sectional Studies Irrespective of Disease Status

In heterogeneous cohorts with both active and controlled disease, general factors that had a negative effect on QoL in patients with acromegaly were higher depression scores (21, 23, 31, 38, 42, 43) and higher BMI (10, 41) (see also Tables 3 and 4). The disease-specific factor hypopituitarism was described to have no significant effect (39, 41, 56, 65), while previous/ongoing treatments could not be associated with QoL in acromegaly [i.e., any treatment of acromegaly (not otherwise specified) (10, 21), surgery vs. somatostatin analogs (57, 65)] and physical activity (33). Other predictors were either not reported, or no consensus was reached on other predictors, such as the demographic factors age and gender, the biochemical parameters GH, IGF1, or biochemical control, and the duration of either disease or remission.

Results from Cross-sectional Studies Stratified for Disease Status

In cohorts with patients with active acromegaly only (six studies), the general factors depression scores (43), age and female gender (63), had a significant negative effect on QoL. The disease-specific factor GH level was described to be positively correlated with QoL (43) (see Table 5). Other predictors were either not reported, or no consensus was reached between the respective articles, such as IGF1, biochemical control, and disease duration.

In cohorts of patients with acromegaly in remission only (11 studies), the general factor depression scores (23) was found to have a negative association with QoL. The disease-specific intervention previous radiotherapy (23, 24, 62, 65) had a negative effect on QoL subscales, whereas follow-up duration (23) had a significant negative effect on QoL subscales. No significant association was found for hypopituitarism (23, 62, 65) and remission duration (62, 63, 65) (see Table 6). Other predictors were either not reported, or no consensus was reached between the respective articles, such as the demographic factors age and gender, the biochemical parameters GH, IGF1, or biochemical control, and the duration of either disease, remission, or follow-up.

Results from Intervention Studies

Three intervention studies demonstrated a significant positive effect of lanreotide autogel treatment on QoL of naïve patients with acromegaly (28, 29, 44), two of those detail the same cohort. Pegvisomant addition to somatostatin receptor ligands also demonstrated to have significant positive effects, both in a cohort biochemically well-controlled by somatostatin analogs (50) and with suboptimal control (61) (see Table 7). A cohort in which patients using octreotide LAR for at least 3 months demonstrated no effect of the injection interval on QoL (22). No significant effect was found for the interventions pegvisomant vs. octreotide-LAR, a study in which treatment-naïve patients were randomized between either pegvisomant or octreotide-LAR with QoL as a secondary outcome (37), physical activity (38), a crossover trial with patients switching to either pasireotide- or octreotide LAR (26) and somatostatin analogs vs. somatostatin analogs plus pegvisomant, a study in which patients controlled on somatostatin analogs were randomized to either continuation of treatment or co-treatment with pegvisomant (45) (see Table 7). Other predictors were either not reported, or no consensus was reached between the respective articles, such as surgery or octreotide treatment.

Results from Longitudinal Studies

Longitudinal, defined as multiple-time point observational studies (nine studies), indicated that higher GH levels (25) as well as depression (36) had a significant negative impact on QoL during follow-up in patients with acromegaly. A reduction in IGF-1 significantly improved QoL (12); hypopituitarism had no significant effect on QoL in follow-up (62, 66). No significant contribution to QoL was found for the factor IGF-1 (25), disease duration (58), duration of remission (62), and education (66) (see Table 8). Other predictors were either not reported, or no consensus was reached between the respective articles.

Discussion

In the present systematic review that included 51 studies, we observed only a limited amount of randomized controlled trials with QoL as an endpoint. Only six randomized trials have been listed (37, 40, 44, 45, 50, 61), with only three of these investigating baseline data of treatment-naïve patients (37, 40, 44). Several risk factors that have shown a significant effect on QoL in cross-sectional observational studies have not been studied in a longitudinal design, such as depression scores and BMI. Studies investigating treatment for either depression or BMI (with the exception of one study that studied physical therapy but not formally targeted BMI) are absent. There are very few studies that assess long-term QoL patients with acromegaly throughout different phases of the disease; current studies do not properly reflect the transition a patient makes from active to controlled disease.

The general factors depression scores and BMI had a significant negative impact on QoL in a number of studies, in cohorts comprising both active and non-active patients. Intriguingly, the disease-specific factor hypopituitarism had no significant association with QoL in patients with acromegaly.

The association of depression scores with reduced QoL may be self-explanatory; previously, we have reported a marked superiority of depression scores over other predictors of QoL (23, 36). Increased scores for psychopathology have been described to be prevalent in patients with acromegaly (16, 21, 62, 68). Whether this observation is caused by acromegaly per se or is the result of a chronic disease in general is not clear. The demonstrated consensus on the significance of depression scores in QoL in patients with acromegaly provides further circumstantial evidence that paying attention to- and treatment of psychopathological comorbidities (by either psychological and/or pharmaceutical approaches) may provide added value to the chronic care of patients with acromegaly. However, no results on the effect of psychotherapy on QoL in patients with acromegaly have been published, whereas it has been a well-established intervention in several other chronic illnesses.

Higher BMI is considered to be associated with reduced QoL both in the general population and in those with chronic disease (69, 70); therefore, it is not surprising that there is a consensus on the significance of BMI as a factor in patients with acromegaly as well. Moreover, Turgut et al. reported that a polymorphism of the GH receptor leading to greater sensitivity (mirroring GH excess) correlated with increased BMI, suggesting a role of GH in acquiring greater body mass (71), independent of acromegaly. Moreover, obesity is a common symptom in acromegaly as GH excess changes one’s body composition even after biochemical control (72), making it a clinically relevant factor to be targeted in order to improve QoL in acromegaly. Up to now, only one study was performed aiming at weight reduction by physical activity, and this study failed to show an improvement in QoL (change in weight was not reported). Further research is needed to evaluate optimal weight reduction strategies in acromegaly and also take into account mobility issues related to arthropathy.

Many comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, which are more prevalent in acromegaly, may also influence QoL in this population. Most published studies have too small numbers to evaluate these parameters.

Many studies have however corrected for the effect of hypopituitarism next to demographic variables without taking into account its individual effect. The observation that hypopituitarism was not associated with QoL in patients with acromegaly may therefore be biased, because hypopituitarism per se is well-known to be a relevant factor in studying health outcomes in other pituitary diseases. With that in mind, we excluded all studies that investigated cohorts with GHD after acromegaly. Second, treatment of other hormone deficiencies in GHD patients has been demonstrated to significantly ameliorate QoL which further substantiates our motivation to exclude this specific condition from the present study (73–76). Moreover, the degree of hypopituitarism may play an important role in its association with QoL. Fathalla et al. described that pan-hypopituitarism had a significant negative effect on QoL (34), however, as this was the only study that investigated the role of pan-hypopituitarism it was not included in the final table.

Remarkably, no consensus on the role of biochemical variables has been reached. GH was shown in one study to be positively associated with QoL in active acromegaly, whereas this association was disputed in other cross-sectional cohorts. Although normalization of GH and IGF-I levels are obviously an important goal for treatment of acromegaly, our results strongly suggests that QoL in acromegaly is a different entity in addition biochemical control per se and may warrant clinical attention transcending current criteria for remission.

Although it seems likely that biomedical treatment of acromegaly would improve its symptoms, including an improvement of QoL, convincing evidence for this is as yet missing. The interventions of treatment with pegvisomant and somatostatin receptor ligands, in particular lanreotide autogel (from cross-sectional studies) reported a significant positive impact on QoL, while general treatment of acromegaly (not otherwise specified) and the comparison of surgery to somatostatin analogs were not reported to be significantly associated with QoL from available cross-sectional data. Obviously, it should be expected that treatments of a similar class as lanreotide autogel would ameliorate QoL in an equally similar fashion. Interestingly, the results on the effect of surgery, long-since the gold standard for cure of acromegaly, are conflicting. This effect, however, has not been investigated in longitudinal trials, rendering evidence on the benefit of surgery in QoL therefore inconclusive. Recent studies show a trend toward a relative positive effect of surgery on QoL, this trend is not supported by cross-sectional studies which predominantly show no correlation between surgery and QoL. Intervention trials are the optimum study design for investigating treatment, further research in larger populations than the current three intervention studies should be conducted to verify whether surgery indeed has a beneficial effect on QoL as it obviously is the first line treatment to establisg remission and amelioration of acromegalic symptoms.

Therefore, large trials with sufficient follow-up data which specifically studies QoL (generic and disease-specific) as a primary long-term outcome for each of the most widely used treatment strategies, either medicinal or surgical, are urgently needed. In an era of treatment choices and increasing focus on the patient perspective knowledge of the effect of distinct treatment options and modalities on QoL from prospective studies is of paramount importance to enable individually tailored decisions based on evidence based medicine.

The relation between GH/IGF1 excess and QoL is complex due limitations inherent to our current understanding of acromegaly. First, the reflection of disease activity is not straightforward and many different parameters to reflect GH excess have been used, usually single time-point measurements rather than time-weighted average GH activity that may not reflect tissue exposure. In addition, a direct comparison between naïve active patients and treated/cured patients is often lacking, both in prospective studies and in cross-sectional studies. Given the fluctuations in GH levels throughout the day, as well as individual differences in set point and sensitivity, it is uncertain whether decisive evidence proving the role of GH levels in QoL will be found in future research (77, 78).

Considering QoL as a complex entity with at least three domains (biological, psychological, and social components) (79), there may be disparity between generic QoL scores and disease-specific/domain-specific scores. Because of limited numbers and the use of many different questionnaires (n = 12), we could not evaluate results for all questionnaires. Limitations of this review include the small size of the studies with heterogeneous cohorts (mean N = 53.47, range 10–291) and the limited amount of longitudinal studies and intervention studies.

A difficulty in comparing studies of different designs (cross-sectional observational vs. intervention vs. longitudinal studies) is exemplified by differences in baseline QoL, particularly with regard to the range in QoL between the studies. Assuming a large difference in effect size of individual factors, direct comparison between the respective studies limits quantitative analyses.

A remarkable limitation in interpreting the results on biochemical control is the timeframe after which biochemical control was achieved. Although we report the parameters studied in both active acromegaly and acromegaly in remission, the largest portion of the studies was conducted in heterogeneous cohorts, which includes a large variety of disease- and follow-up durations. Despite this being a good reflection of clinical practice-cohorts, it may be beneficial to study QoL in acromegaly over an extended period of time, from diagnosis to long-term follow-up.

In conclusion, this article provides a comprehensive overview of the available literature until January 2017 for associative factors and predictors of QoL in acromegaly. It provides systematic evidence for the significant role of depression scores and BMI, but does not provide further arguments to support the role of biochemical parameters such as hormonal normalization as well as hypopituitarism and the main therapeutic modalities for acromegaly. At present, only interventions with lanreotide autogel and pegvisomant have shown to consistently improve QoL, while the effect of other interventions is either unclear or not properly assessed prospectively. Future research should include prospective and longitudinal measurements of QoL and the patient perspective to be able to use QoL scores in clinical decision making. Finally, treatment of depressive symptoms and BMI-reducing strategies are promising targets for QoL improvement strategies.

Author Contributions

VG, CS, and NB conceived the study; are responsible for the integrity of the study; VG and CA collected and analyzed the data. All authors critically reviewed various draft of the manuscript and approval was consensual by all authors for the final version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fendo.2017.00040/full#supplementary-material.

References

1. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med (1995) 41(10):1403–9.

2. Schipper H, Clinch JJ, Olweny CLM. Quality of life studies: definitions and conceptual issues. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers (1996). p. 11–23.

3. Arosio M, Reimondo G, Malchiodi E, Berchialla P, Borraccino A, De ML, et al. Predictors of morbidity and mortality in acromegaly: an Italian survey. Eur J Endocrinol (2012) 167(2):189–98. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0084

4. Mercado M, Gonzalez B, Vargas G, Ramirez C, Espinosa de Los Monteros AL, Sosa E, et al. Successful mortality reduction and control of co-morbidities in patients with acromegaly followed at a highly specialized multidisciplinary clinic. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2014) 99(12):4438–46. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-2670

5. Schofl C, Franz H, Grussendorf M, Honegger J, Jaursch-Hancke C, Mayr B, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with acromegaly: analysis of 1344 patients from the German Acromegaly Register. Eur J Endocrinol (2013) 168(1):39–47. doi:10.1530/EJE-12-0602

6. Johnson MD, Woodburn CJ, Vance ML. Quality of life in patients with a pituitary adenoma. Pituitary (2003) 6(2):81–7. doi:10.1023/B:PITU.0000004798.27230.ed

7. Giustina A, Chanson P, Kleinberg D, Bronstein MD, Clemmons DR, Klibanski A, et al. Expert consensus document: a consensus on the medical treatment of acromegaly. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2014) 10(4):243–8. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2014.21

8. Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Klibanski A, Bronstein MD, Chanson P, Lamberts SW, et al. A consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly complications. Pituitary (2013) 16(3):294–302. doi:10.1007/s11102-012-0420-x

9. Hua SC, Yan YH, Chang TC. Associations of remission status and lanreotide treatment with quality of life in patients with treated acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol (2006) 155(6):831–7. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02292

10. T’Sjoen G, Bex M, Maiter D, Velkeniers B, Abs R. Health-related quality of life in acromegalic subjects: data from AcroBel, the Belgian registry on acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol (2007) 157(4):411–7. doi:10.1530/EJE-07-0356

11. Webb SM. Quality of life in acromegaly. Neuroendocrinology (2006) 83(3–4):224–9. doi:10.1159/000095532

12. Paisley AN, Rowles SV, Roberts ME, Webb SM, Badia X, Prieto L, et al. Treatment of acromegaly improves quality of life, measured by AcroQol. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2007) 67(3):358–62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02891.x

13. Trepp R, Everts R, Stettler C, Fischli S, Allemann S, Webb SM, et al. Assessment of quality of life in patients with uncontrolled vs. controlled acromegaly using the Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire (AcroQoL). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2005) 63(1):103–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02307.x

14. Sievers C, Samann PG, Dose T, Dimopoulou C, Spieler D, Roemmler J, et al. Macroscopic brain architecture changes and white matter pathology in acromegaly: a clinicoradiological study. Pituitary (2009) 12(3):177–85. doi:10.1007/s11102-008-0143-1

15. Colao A, Pivonello R, Scarpa R, Vallone G, Ruosi C, Lombardi G. The acromegalic arthropathy. J Endocrinol Invest (2005) 28(8 Suppl):24–31.

16. Sievers C, Dimopoulou C, Pfister H, Lieb R, Steffin B, Roemmler J, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in acromegaly: a cross-sectional study in 81 acromegalic patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2009) 71(5):691–701. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03555.x

17. Freda PU, Shen W, Heymsfield SB, Reyes-Vidal CM, Geer EB, Bruce JN, et al. Lower visceral and subcutaneous but higher intermuscular adipose tissue depots in patients with growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I excess due to acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2008) 93(6):2334–43. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-2780

18. Sucunza N, Barahona MJ, Resmini E, Fernandez-Real JM, Ricart W, Farrerons J, et al. A link between bone mineral density and serum adiponectin and visfatin levels in acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2009) 94(10):3889–96. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-0474

19. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). (2009). Available from: www.prisma-statement.org

20. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. (2014). Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

21. Anagnostis P, Efstathiadou ZA, Charizopoulou M, Selalmatzidou D, Karathanasi E, Poulasouchidou M, et al. Psychological profile and quality of life in patients with acromegaly in Greece. Is there any difference with other chronic diseases? Endocrine (2014) 47(2):564–71. doi:10.1007/s12020-014-0166-5

22. Biermasz NR, van den Oever NC, Frolich M, Arias AM, Smit JW, Romijn JA, et al. Sandostatin LAR in acromegaly: a 6-week injection interval suppresses GH secretion as effectively as a 4-week interval. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2003) 58(3):288–95. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01710.x

23. Biermasz NR, van Thiel SW, Pereira AM, Hoftijzer HC, van Hemert AM, Smit JW, et al. Decreased quality of life in patients with acromegaly despite long-term cure of growth hormone excess. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2004) 89(11):5369–76. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0669

24. Biermasz NR, Pereira AM, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Roelfsema F. Morbidity after long-term remission for acromegaly: persisting joint-related complaints cause reduced quality of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2005) 90(5):2731–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-2297

25. Bonapart IE, van DR, ten Have SM, de Herder WW, Erdman RA, Janssen JA, et al. The ’bio-assay’ quality of life might be a better marker of disease activity in acromegalic patients than serum total IGF-I concentrations. Eur J Endocrinol (2005) 152(2):217–24. doi:10.1530/eje.1.01838

26. Bronstein MD, Fleseriu M, Neggers S, Colao A, Sheppard M, Gu F, et al. Switching patients with acromegaly from octreotide to pasireotide improves biochemical control: crossover extension to a randomized, double-blind, Phase III study. BMC Endocr Disord (2016) 16:16. doi:10.1186/s12902-016-0096-8

27. Cannavo S, Condurso R, Ragonese M, Ferrau F, Alibrandi A, Arico I, et al. Increased prevalence of restless legs syndrome in patients with acromegaly and effects on quality of life assessed by Acro-QoL. Pituitary (2011) 14(4):328–34. doi:10.1007/s11102-011-0298-z

28. Caron PJ, Bevan JS, Petersenn S, Flanagan D, Tabarin A, Prevost G, et al. Tumor shrinkage with lanreotide Autogel 120 mg as primary therapy in acromegaly: results of a prospective multicenter clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2014) 99(4):1282–90. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-3318

29. Caron PJ, Bevan JS, Petersenn S, Houchard A, Sert C, Webb SM. Effects of lanreotide Autogel primary therapy on symptoms and quality-of-life in acromegaly: data from the PRIMARYS study. Pituitary (2016) 19(2):149–57. doi:10.1007/s11102-015-0693-y

30. Celik O, Hatipoglu E, Akhan SE, Uludag S, Kadioglu P. Acromegaly is associated with higher frequency of female sexual dysfunction: experience of a single center. Endocr J (2013) 60(6):753–61. doi:10.1507/endocrj.EJ12-0424

31. Celik O, Kadioglu P. Quality of life in female patients with acromegaly. J Endocrinol Invest (2013) 36(6):412–6. doi:10.3275/8761

32. Chin SO, Chung CH, Chung YS, Kim BJ, Kim HY, Kim IJ, et al. Change in quality of life in patients with acromegaly after treatment with octreotide LAR: first application of AcroQoL in Korea. BMJ Open (2015) 5(6):e006898. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006898

33. Dantas RA, Passos KE, Porto LB, Zakir JC, Reis MC, Naves LA. Physical activities in daily life and functional capacity compared to disease activity control in acromegalic patients: impact in self-reported quality of life. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol (2013) 57(7):550–7. doi:10.1590/S0004-27302013000700009

34. Fathalla H, Cusimano MD, Alsharif OM, Jing R. Endoscopic transphenoidal surgery for acromegaly improves quality of life. Can J Neurol Sci (2014) 41(6):735–41. doi:10.1017/cjn.2014.106

35. Fujio S, Arimura H, Hirano H, Habu M, Bohara M, Moinuddin FM, et al. Changes in quality of life in patients with acromegaly after surgical remission – a prospective study using SF-36 questionnaire. Endocr J (2016) 64(1):27–38. doi:10.1507/endocrj.EJ16-0182

36. Geraedts VJ, Dimopoulou C, Auer M, Schopohl J, Stalla GK, Sievers C. Health outcomes in acromegaly: depression and anxiety are promising targets for improving reduced quality of life. Front Endocrinol (2014) 5:229. doi:10.3389/fendo.2014.00229

37. Ghigo E, Biller BM, Colao A, Kourides IA, Rajicic N, Hutson RK, et al. Comparison of pegvisomant and long-acting octreotide in patients with acromegaly naive to radiation and medical therapy. J Endocrinol Invest (2009) 32(11):924–33. doi:10.1007/BF03345774

38. Hatipoglu E, Topsakal N, Atilgan OE, Alcalar N, Camliguney AF, Niyazoglu M, et al. Impact of exercise on quality of life and body-self perception of patients with acromegaly. Pituitary (2014) 17(1):38–43. doi:10.1007/s11102-013-0463-7

39. Hatipoglu E, Yuruyen M, Keskin E, Yavuzer H, Niyazoglu M, Doventas A, et al. Acromegaly and aging: a comparative cross-sectional study. Growth Horm IGF Res (2015) 25(1):47–52. doi:10.1016/j.ghir.2014.12.003

40. Karaca Z, Tanriverdi F, Elbuken G, Cakir I, Donmez H, Selcuklu A, et al. Comparison of primary octreotide-lar and surgical treatment in newly diagnosed patients with acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2011) 75(5):678–84. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04106.x

41. Kauppinen-Makelin R, Sane T, Sintonen H, Markkanen H, Valimaki MJ, Loyttyniemi E, et al. Quality of life in treated patients with acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2006) 91(10):3891–6. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0676

42. Kepicoglu H, Hatipoglu E, Bulut I, Darici E, Hizli N, Kadioglu P. Impact of treatment satisfaction on quality of life of patients with acromegaly. Pituitary (2014) 17(6):557–63. doi:10.1007/s11102-013-0544-7

43. Leon-Carrion J, Martin-Rodriguez JF, Madrazo-Atutxa A, Soto-Moreno A, Venegas-Moreno E, Torres-Vela E, et al. Evidence of cognitive and neurophysiological impairment in patients with untreated naive acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2010) 95(9):4367–79. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0394

44. Lombardi G, Minuto F, Tamburrano G, Ambrosio MR, Arnaldi G, Arosio M, et al. Efficacy of the new long-acting formulation of lanreotide (lanreotide Autogel) in somatostatin analogue-naive patients with acromegaly. J Endocrinol Invest (2009) 32(3):202–9. doi:10.1007/BF03346453

45. Madsen M, Poulsen PL, Orskov H, Moller N, Jorgensen JO. Cotreatment with pegvisomant and a somatostatin analog (SA) in SA-responsive acromegalic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2011) 96(8):2405–13. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0654

46. Mangupli R, Camperos P, Webb SM. Biochemical and quality of life responses to octreotide-LAR in acromegaly. Pituitary (2014) 17(6):495–9. doi:10.1007/s11102-013-0533-x

47. Matta MP, Couture E, Cazals L, Vezzosi D, Bennet A, Caron P. Impaired quality of life of patients with acromegaly: control of GH/IGF-I excess improves psychological subscale appearance. Eur J Endocrinol (2008) 158(3):305–10. doi:10.1530/EJE-07-0697

48. Milian M, Honegger J, Gerlach C, Psaras T. Health-related quality of life and psychiatric symptoms improve effectively within a short time in patients surgically treated for pituitary tumors – a longitudinal study of 106 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) (2013) 155(9):1637–45. doi:10.1007/s00701-013-1809-7

49. Miller A, Doll H, David J, Wass J. Impact of musculoskeletal disease on quality of life in long-standing acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol (2008) 158(5):587–93. doi:10.1530/EJE-07-0838

50. Neggers SJ, van Aken MO, de Herder WW, Feelders RA, Janssen JA, Badia X, et al. Quality of life in acromegalic patients during long-term somatostatin analog treatment with and without pegvisomant. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2008) 93(10):3853–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-0669

51. Postma MR, Netea-Maier RT, van den Berg G, Homan J, Sluiter WJ, Wagenmakers MA, et al. Quality of life is impaired in association with the need for prolonged postoperative therapy by somatostatin analogs in patients with acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol (2012) 166(4):585–92. doi:10.1530/EJE-11-0853

52. Psaras T, Honegger J, Gallwitz B, Milian M. Are there gender-specific differences concerning quality of life in treated acromegalic patients? Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes (2011) 119(5):300–5. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1267912

53. Psaras T, Milian M, Hattermann V, Will BE, Tatagiba M, Honegger J. Predictive factors for neurocognitive function and quality of life after surgical treatment for Cushing’s disease and acromegaly. J Endocrinol Invest (2011) 34(7):e168–77. doi:10.3275/7333

54. Raappana A, Pirila T, Ebeling T, Salmela P, Sintonen H, Koivukangas J. Long-term health-related quality of life of surgically treated pituitary adenoma patients: a descriptive study. ISRN Endocrinol (2012) 2012:675310. doi:10.5402/2012/675310

55. Roerink S, Marsman D, van BA, Netea-Maier R. A missed diagnosis of acromegaly during a female-to-male gender transition. Arch Sex Behav (2014) 43(6):1199–201. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0309-z

56. Rowles SV, Prieto L, Badia X, Shalet SM, Webb SM, Trainer PJ. Quality of life (QOL) in patients with acromegaly is severely impaired: use of a novel measure of QOL: acromegaly quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2005) 90(6):3337–41. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1565

57. Rubeck KZ, Madsen M, Andreasen CM, Fisker S, Frystyk J, Jorgensen JO. Conventional and novel biomarkers of treatment outcome in patients with acromegaly: discordant results after somatostatin analog treatment compared with surgery. Eur J Endocrinol (2010) 163(5):717–26. doi:10.1530/EJE-10-0640

58. Sardella C, Lombardi M, Rossi G, Cosci C, Brogioni S, Scattina I, et al. Short- and long-term changes of quality of life in patients with acromegaly: results from a prospective study. J Endocrinol Invest (2010) 33(1):20–5. doi:10.1007/BF03346555

59. Schopohl J, Strasburger CJ, Caird D, Badenhoop K, Beuschlein F, Droste M, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of lanreotide Autogel(R) 120 mg at different dose intervals in patients with acromegaly previously treated with octreotide LAR. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes (2011) 119(3):156–62. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1267244

60. Siegel S, Streetz-van der Werf C, Schott JS, Nolte K, Karges W, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I. Diagnostic delay is associated with psychosocial impairment in acromegaly. Pituitary (2013) 16(4):507–14. doi:10.1007/s11102-012-0447-z

61. Trainer PJ, Ezzat S, D’Souza GA, Layton G, Strasburger CJ. A randomized, controlled, multicentre trial comparing pegvisomant alone with combination therapy of pegvisomant and long-acting octreotide in patients with acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2009) 71(4):549–57. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03620.x

62. van der Klaauw AA, Biermasz NR, Hoftijzer HC, Pereira AM, Romijn JA. Previous radiotherapy negatively influences quality of life during 4 years of follow-up in patients cured from acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2008) 69(1):123–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03169.x

63. Vandeva S, Yaneva M, Natchev E, Elenkova A, Kalinov K, Zacharieva S. Disease control and treatment modalities have impact on quality of life in acromegaly evaluated by Acromegaly Quality of Life (AcroQoL) Questionnaire. Endocrine (2015) 49(3):774–82. doi:10.1007/s12020-014-0521-6

64. Varewijck AJ, van der Lely AJ, Neggers SJ, Lamberts SW, Hofland LJ, Janssen JA. In active acromegaly, IGF1 bioactivity is related to soluble Klotho levels and quality of life. Endocr Connect (2014) 3(2):85–92. doi:10.1530/EC-14-0028

65. Wassenaar MJ, Biermasz NR, Kloppenburg M, van der Klaauw AA, Tiemensma J, Smit JW, et al. Clinical osteoarthritis predicts physical and psychological QoL in acromegaly patients. Growth Horm IGF Res (2010) 20(3):226–33. doi:10.1016/j.ghir.2010.02.003

66. Webb SM, Badia X, Surinach NL. Validity and clinical applicability of the acromegaly quality of life questionnaire, AcroQoL: a 6-month prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol (2006) 155(2):269–77. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02214

67. Yoshida K, Fukuoka H, Matsumoto R, Bando H, Suda K, Nishizawa H, et al. The quality of life in acromegalic patients with biochemical remission by surgery alone is superior to that in those with pharmaceutical therapy without radiotherapy, using the newly developed Japanese version of the AcroQoL. Pituitary (2015) 18(6):876–83. doi:10.1007/s11102-015-0665-2

68. Sievers C, Ising M, Pfister H, Dimopoulou C, Schneider HJ, Roemmler J, et al. Personality in patients with pituitary adenomas is characterized by increased anxiety-related traits: comparison of 70 acromegalic patients with patients with non-functioning pituitary adenomas and age- and gender-matched controls. Eur J Endocrinol (2009) 160(3):367–73. doi:10.1530/EJE-08-0896

69. Kim CH, Luedtke CA, Vincent A, Thompson JM, Oh TH. Association of body mass index with symptom severity and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) (2012) 64(2):222–8. doi:10.1002/acr.20653

70. de Hollander EL, Picavet HS, Milder IE, Verschuren WM, Bemelmans WJ, de Groot LC. The impact of long-term body mass index patterns on health-related quality of life: the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol (2013) 178(5):804–12. doi:10.1093/aje/kwt053

71. Turgut S, Akin F, Ayada C, Topsakal S, Yerlikaya E, Turgut G. The growth hormone receptor polymorphism in patients with acromegaly: relationship to BMI and glucose metabolism. Pituitary (2012) 15(3):374–9. doi:10.1007/s11102-011-0329-9

72. Dimopoulou C, Sievers C, Wittchen HU, Pieper L, Klotsche J, Roemmler J, et al. Adverse anthropometric risk profile in biochemically controlled acromegalic patients: comparison with an age- and gender-matched primary care population. Pituitary (2010) 13(3):207–14. doi:10.1007/s11102-010-0218-7

73. Valassi E, Brick DJ, Johnson JC, Biller BM, Klibanski A, Miller KK. Effect of growth hormone replacement therapy on the quality of life in women with growth hormone deficiency who have a history of acromegaly versus other disorders. Endocr Pract (2012) 18(2):209–18. doi:10.4158/EP11134.OR

74. Miller KK, Wexler T, Fazeli P, Gunnell L, Graham GJ, Beauregard C, et al. Growth hormone deficiency after treatment of acromegaly: a randomized, placebo-controlled study of growth hormone replacement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2010) 95(2):567–77. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-1611

75. Giavoli C, Profka E, Verrua E, Ronchi CL, Ferrante E, Bergamaschi S, et al. GH replacement improves quality of life and metabolic parameters in cured acromegalic patients with growth hormone deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2012) 97(11):3983–8. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-2477

76. van der Klaauw AA, Bax JJ, Roelfsema F, Stokkel MP, Bleeker GB, Biermasz NR, et al. Limited effects of growth hormone replacement in patients with GH deficiency during long-term cure of acromegaly. Pituitary (2009) 12(4):339–46. doi:10.1007/s11102-009-0186-y

77. Ilias I, Vgontzas AN, Provata A, Mastorakos G. Complexity and non-linear description of diurnal cortisol and growth hormone secretory patterns before and after sleep deprivation. Endocr Regul (2002) 36(2):63–72.

78. Gill MS, Thalange NK, Foster PJ, Tillmann V, Price DA, Diggle PJ, et al. Regular fluctuations in growth hormone (GH) release determine normal human growth. Growth Horm IGF Res (1999) 9(2):114–22. doi:10.1054/ghir.1999.0095

Keywords: acromegaly, quality of life, systematic review, depression, biochemical control

Citation: Geraedts VJ, Andela CD, Stalla GK, Pereira AM, van Furth WR, Sievers C and Biermasz NR (2017) Predictors of Quality of Life in Acromegaly: No Consensus on Biochemical Parameters. Front. Endocrinol. 8:40. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00040

Received: 05 December 2016; Accepted: 16 February 2017;

Published: 03 March 2017

Edited by:

Carmen E. Georgescu, Iuliu Haţieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, RomaniaReviewed by:

Anton Luger, Medical University of Vienna, AustriaGianluca Tamagno, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Ireland

Copyright: © 2017 Geraedts, Andela, Stalla, Pereira, van Furth, Sievers and Biermasz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nienke R. Biermasz, bi5yLmJpZXJtYXN6QGx1bWMubmw=

Victor J. Geraedts

Victor J. Geraedts Cornelie D. Andela2

Cornelie D. Andela2 Günter K. Stalla

Günter K. Stalla Alberto M. Pereira

Alberto M. Pereira Nienke R. Biermasz

Nienke R. Biermasz