- 1Endocrinology Service and Research Center, Sainte-Justine University Hospital Center, Department of Pediatrics, Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 2Division of Pediatric Endocrinology, University Children’s Hospital Basel (UKBB), University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

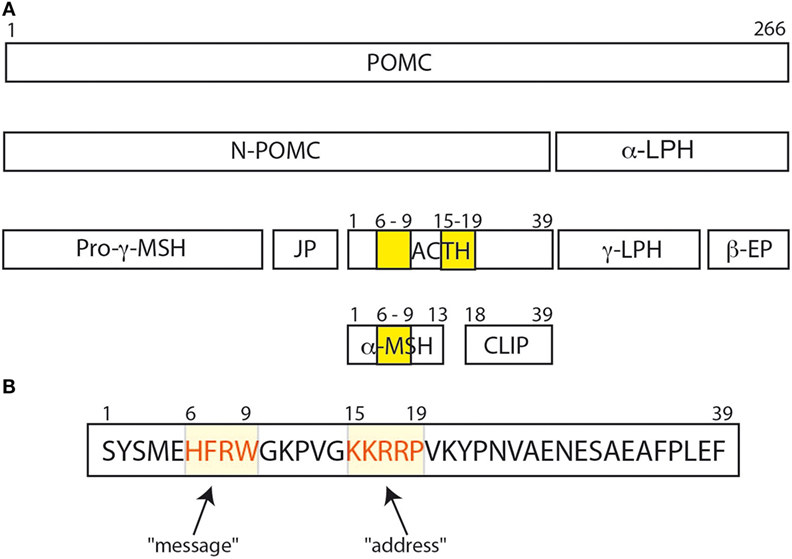

The adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) is a pituitary hormone derived from a larger peptide, the proopiomelanocortin (POMC), as are the MSHs (α-MSH, β-MSH, and γ-MSH) and the β-LPH-related polypeptides (Figure 1A). ACTH drives adrenal steroidogenesis and growth of the adrenal gland. ACTH is a 39 amino acid polypeptide that binds and activates its cognate receptor [melanocortin receptor 2 (MC2R)] through the two regions H6F7R8W9 and K15K16R17R18P19. Most POMC-derived polypeptides contain the H6F7R8W9 sequence that is conserved through evolution. This explains the difficulties in developing selective agonists or antagonists to the MCRs. In this review, we will discuss the clinical aspects of the role of ACTH in physiology and disease, and potential clinical use of selective ACTH antagonists.

From the Concept of “Stress” to the Discovery of Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH)

Adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol are nowadays associated with the physiological response to stress. Historically, the concept of stress was first introduced in 1936 by Hans Selye (1). It was first called the “general adaptation syndrome” and later renamed by Selye as “stress response.” Stress results from the balance between the stressor, an agent that produces stress at any time, and the body’s adaptive response to it. His experiments on rats in 1936 have shown that a stressor often alters the adrenal cortex, the immune system, and the gut. Indeed, rats exposed to various nocuous chemical or physical stimuli had a hypertrophy of the adrenals, an involution of the lymphatic nodes and developed gastric erosions (2).

In the 1930s–1940s, Selye performed extensive structure–function studies, resulting in the first classification of steroid hormones, e.g., corticoids, testoids/androgens, and folliculoids/estrogens (3, 4). During those years, he recognized the respective anti- and pro-inflammatory actions of gluco- and mineralocorticoids (named by Selye) in animal models, several years before demonstration of anti-rheumatic actions of cortisone and ACTHs in patients. In 1935 and 21 years after having isolated thyroxine in crystalline form, Kendall isolated and identified the structure of cortisone, and in 1936, Reichstein identified the structure of cortisol. In 1948, Hench and Kendall demonstrated that cortisone and ACTH exert a profound anti-inflammatory effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In 1950, Hench, Kendall, and Reichstein were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for these discoveries. In the same year, Harris established that ACTH secretion involves “neuronal control via the hypothalamus and the hypophyseal portal vessels of the pituitary stalk” (5). ACTH was first isolated in 1943 and then synthesized in the 1960s and 1970s by different groups (6–9). Next, the amino acid sequences of ACTH from four mammalian species were elucidated between 1954 and 1961 by three groups of Bell, Li, and Lerner (6, 10, 11). In 1955, Guillemin (a former student of Selye’s) and Rosenberg demonstrated in rats the existence of CRF, the hypothalamic factor that allows ACTH release (12).

ACTH Structure and Function

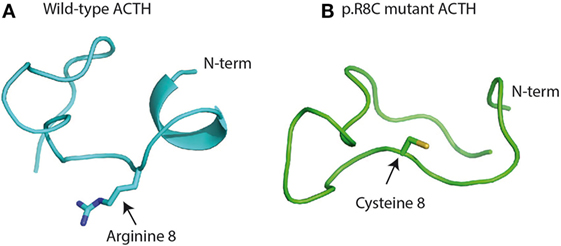

Adrenocorticotropic hormone, adrenocorticotropin, corticotropin, or ACTH, transmits information from the anterior lobe of the pituitary to the adrenal cortex. ACTH is a linear non-atriacontapeptide with species differences in the COOH terminal two-third of the molecule (13). Initially, an analysis of the ACTH crystal structure was still lacking. In the early 1970s, different polypeptides were isolated from different lobes of the vertebrate pituitary (14). Lowry showed that ACTH and β-lipotropin (β-LPH) shared the same amino acid motif H6F7R8W9 even if they have different functions (14, 15) (Figure 1). α-MSH and β-MSH were found to be embedded within the primary sequences of ACTH and β-LPH, respectively, in the melanocorticotropic cells (in the intermediate pituitary) (16). A few years later, the prediction that ACTH, the MSHs, and the β-LPH-related polypeptides were derived from the same precursor (17) was confirmed by the cloning of the proopiomelanocortin gene (POMC) mRNA (18). Initially, Schwyzer and Sieber suggested that ACTH is a linear polypeptide (19). Later, Schiller showed that residues 10–21 have a flexible conformation (20). Squire and Bewley had already suggested that a small region close to N-terminus had a tendency to form a helical structure (21). Low et al. have confirmed that a helical structure is produced in a solvent, the trifluoroethanol (22). It was suggested that this conformational change could occur when ACTH binds its receptor, to ensure a kinetically and a thermodynamically optimal hormone–receptor contact (23, 24). Later, Hruby et al. showed that the N terminal region of ACTH, between residues 4 and 10, adopts a β-turn conformation (25). Molecular modeling supports this hypothesis, given the presence of an N-terminal helical structure in the wild-type ACTH model (Figure 2A). This helical secondary structure is disrupted by validated inactivating mutations, which suggests that it is essential for ACTH bioactivity (Figure 2B).

Figure 1. (A) The POMC protein and its various peptide cleavage products: the yellow bands correspond to the amino acid sequences His6Phe7Arg8Trp9 and Lys15Lys16Arg17Arg18Pro19. His6Phe7Arg8Trp9 is important for binding and signal transduction of α-MSH. (B) His6Phe7Arg8Trp9 sequence is important for adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) signal transduction and for ACTH binding to melanocortin receptor 2 (MC2R) (26), and was called the “message” sequence (13). The amino acids Lys15Lys16Arg17Arg18Pro19 was initially defined as the “address” sequence allowing specific ACTH binding to MC2R (27).

Figure 2. Structure of wild-type (A) and mutant adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (B) after a 100-ns molecular dynamics simulation in implicit water (28, 29): (A) to retain full bioactivity, the N-terminal “message” sequence has to conserve its helical secondary structure as postulated by Schwyzer 40 years ago (13). (B) Naturally occurring bioinactive ACTH mutation (p.R8C) disrupts the helical conformation and hampers proper binding and activation of the melanocortin receptor 2 (26).

Due to different bioassay systems, several research teams screened the biological activity of C terminally truncated analogs of ACTH (1–39) (30). ACTH (1–24) was as potent as ACTH (1–39) to induce glucocorticoid production by adrenal cells in culture (31), while ACTH (1–16) was unable to do so. It was concluded that the critical portion of ACTH for activating adrenal cells resided between residues 17 and 24 (31). However, the analog ACTH (11–24) was unable to induce glucocorticoid production and was even an antagonist at high concentrations (31). Fauchère et al. showed that dimers of ACTH (11–24) and ACTH (7–24) were potent antagonists, whereas ACTH (1–24) dimers remained agonists but were 70 times less potent when compared to its monomeric ACTH (1–24) (32–34).

Altogether, Schwyzer concluded that residues 17–24 were important for recognition of ACTH by its adrenal receptor, and he coined the term “address sequence” to indicate that these residues allowed the ligand to find the cognate receptor (Figure 1B) (13, 27). As Costa et al. suggested, the position 20 should be included in the address site (35). To activate the adrenal receptor, a “message” region is needed. Several studies suggested that the H6F7R8W9 motif should be considered as the “message sequence” (13) (Figure 1B). Indeed, both address and message sequences are necessary to activate the adrenal receptor: the address sequence interacts with the adrenal receptor and then the message sequence enters in contact with the receptor to induce the conformation change in the receptor that activates the adrenal cell (27). This could explain why α-MSH could not activate adrenal cells, even if it has the H6F7R8W9 motif. On the other hand, Schwyzer considered also the effect of analogs of ACTH (1–39) on the activation of melanocytes. All analogs of ACTH (N-terminally as well as C terminally truncated forms) were able to activate melanocytes as long as the H6F7R8W9 motif was intact (13, 27), and the H6F7R8W9 motif is probably both the message and the address sequence in these cells.

In the 1990s, five melanocortin receptor (MCR) genes were identified in the genome of mammals, tetrapods, birds, bony fish, and cartilaginous fish (36–39). MC1R mediates pigmentation, MC2R activates glucocorticoid biosynthesis in the adrenal cortex, MC3R and MC4R influence metabolic homeostasis in the central nervous system and periphery (40), and MC5R regulates sebaceous gland secretions (41). The MCRs belong to the rhodopsin family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (37, 42). They induce intracellular cyclic AMP production following activation by ligands (43, 44). ACTH (1–39) or α-MSH can activate MC1R, MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R (37), but MC2R can only be activated by ACTH and not by α-MSH or other analogs (45). The MCR genes have now been cloned and expressed in cell lines, allowing in vitro binding and activation assays of ACTH analogs against all MCRs. Recently, it has been shown that MC2R requires the presence of the melanocortin receptor-associated protein (MRAP) to be expressed and active at the cell surface (46–49).

Although ACTH and α-MSH both have the H6F7R8W9 motif, only ACTH can activate MC2R. This raises the question of differences between the H6F7R8W9-binding site in MC2R when compared to the other MCRs. Due to a crystal structure of the H6F7R8W9-binding site and site-directed mutagenesis analyses of human MC4R, we know that vertebrate MCRs have a common H6F7R8W9-binding site (50–53), which further confirms that the H6F7R8W9 motif is both the message sequence and the address sequence for the α-MSH. Dores hypothesized that, prior to stimulation, MC1, MC3, MC4, or MC5 receptors have a binding site that is in an open conformation for the ligand. When the ligand interacts with the receptor, it leads to a conformational change (a “docking event”) that activates the receptor (27). Therefore, the activation of MC2R may be a multistep process that requires (i) a conformational change after docking of the H6F7R8W9 motif on its MC2R-binding site and, in the second step, (ii) docking of the K15K16R17R18P19 motif of ACTH to activate the MC2R receptor (27, 54). This could explain the differential ligand selectivity of the MCRs. However, further analyses and experiments are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Familial Glucocorticoid Deficiency (FGD) and POMC Deficiency

Familial Glucocorticoid Deficiency

The glucocorticoid deficiency syndrome (FGD) is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by insensitivity to ACTH action on the adrenal cortex (55), thereby resulting in glucocorticoid insufficiency with intact mineralocorticoid secretion. It may manifest during early neonatal life but can be diagnosed later during childhood. Clinical manifestations include recurrent hypoglycemia that may lead to seizures and coma, chronic fatigue, failure to thrive, recurrent infections, and skin hyperpigmentation. Typically, plasma cortisol levels are very low or undetectable without response to ACTH, while endogenous ACTH levels are very high, which clearly shows a specific resistance to the action of ACTH in these patients. The aldosterone and renin levels are usually normal and correctly match the activation of the renin–angiotensin axis. Even if congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) (due to defects in the glucocorticoid synthesis pathway), congenital adrenal hypoplasia, and X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy are associated with high ACTH and low cortisol levels, they are distinct from FGD.

So far, mutations in five genes have been associated with isolated FGD and four with FGD associated with various syndromic features. In all these genetic disorders, low cortisol and a high ACTH suggest ACTH resistance. Causative genes of isolated FGD are the ACTH receptor (MC2R; also formerly defined as FGD 1) (56), the melanocortin receptor-associated protein (MRAP; also formerly defined as FGD 2) (46), the DAX1 transcription factor (NR0B1) (57), nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT) (58–60), and mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase (TXNRD2) (61). Interestingly, NNT and thioredoxin reductase (TXNRD2) are crucial enzymes for the production of sufficient NADPH to maintain the redox potential in the steroid-producing cells. Four syndromes have been reported with FDG: (i) the AAA(A) syndrome (ACTH resistance, alacrimia, achalasia, and autonomous system dysfunction) due to AAAS mutations (62); (ii) the IMAGe syndrome (intrauterine growth restriction, metaphyseal dysplasia, adrenal hypoplasia congenita, and genital anomalies) due to CDKN1C mutations (63); (iii) a syndrome with short stature, recurrent infection due to natural killer cell deficiency, and chromosomal fragility associated with mutation of the DNA helicase, minichromosome maintenance 4 (MCM4) (64); and (iv) the MIRAGE syndrome (myelodysplasia, infection, restriction of growth, adrenal hypoplasia, genital phenotypes, and enteropathy) due to mutations in SAMD9 (65).

POMC Deficiency

Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) deficiency causes severe monogenic obesity that begins at an early age, adrenal insufficiency, red hair, and pale skin. Affected infants have a normal weight at birth, but they develop early hyperphagia that leads to excessive weight gain starting in the first year of life. During the neonatal period, patients usually present with hypoglycemic seizures, hyperbilirubinemia, and cholestasis due to secondary hypocorticism (66). Subclinical hypothyroidism was also reported. The incidence is very low, about one in 1 million. Complete POMC deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder and is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in the POMC gene on chromosome 2p23.3.

POMC is regulated by leptin and is cleaved by prohormone convertases to produce ACTH and MSH α, β, and γ. In POMC deficiency, the serum concentrations of these cleavage products are low. The red hair pigmentation, adrenal insufficiency, and obesity are caused by inability to activate the MC1, MC2, and MC4 receptors, respectively (66). In addition to complete POMC deficiency, isolated deficiency of β-MSH has been described. This isolated deficiency of β-MSH leads to severe obesity without adrenal insufficiency or red hair (67, 68).

A few years ago, we reported glucocorticoid deficiency in two unrelated patients with apparent ACTH resistance due to an unusual mutation in POMC: the p.R8C mutation in the sequence encoding ACTH and α-MSH (26). The patients (a 4-year-old girl and a 4-month-old boy) presented with hypoglycemia, low cortisol, normal electrolytes, and high ACTH. Both patients had red hair, adrenal insufficiency, and developed early-onset obesity. They were initially treated with gluco- and mineralocorticoids, but after the identification of the mutation in POMC, mineralocorticoid treatment was discontinued in both patients. Whole exome sequencing revealed that the girl was compound heterozygous for POMC mutations: one previously described null allele and one novel p.R8C mutation in the sequence encoding ACTH and α-MSH. The boy was homozygous for the p.R8C mutation. We demonstrated that even if ACTH-R8C was immunoreactive, it failed to bind and activate cAMP production in melanocortin-2 receptor (MC2R)-expressing cells. We demonstrated also that α-MSH-R8C failed to bind and stimulate cAMP production in MC1R- and MC4R-expressing cells.

Discovery of this mutation indicates that in humans, unlike rodents, the amino acid sequence H6F7R8W9 is important not only for cAMP activation but also for ACTH binding to the MC2R. Furthermore, in silico modeling suggested that the pR8C mutation disrupts the secondary structure of ACTH, which implies that this secondary structure may have a crucial role for M2R activation (Figure 2).

Diagnosis of complete POMC deficiency may be suspected on the basis of clinical manifestations and can be confirmed by identification of mutations in the POMC gene. To treat POMC-deficient patients, only hydrocortisone substitution is currently available and is required. An intranasal administration of the ACTH 4–10 melanocortin fragment did not lead to a reduction in body weight. Administration of thyroid hormone had no effect on obesity (69). Recently, two extremely obese POMC patients have been substituted with a MC4R agonist (setmelanotide), and a significant reduction of their weight has been achieved (more than 10% after 10 weeks of treatment) (70). This paves the way for treatment of this condition with specific MC4R agonists and should also prompt research into developing agonists to other MCRs such as MC2R.

Perspectives: A Role for Specific ACTH Antagonists in Human Disease

Specific ACTH antagonists would be of great value especially to treat two conditions: CAH and primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (PBMAH). Moreover, MC2R antagonists could represent a valuable alternative to anticortisolic drugs in clinical management of ACTH-dependent hypercortisolism, essentially Cushing’s disease, when removal of the source of ACTH excess is impossible or incomplete.

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

Adrenocorticotropic hormone drives the synthesis and secretion of cortisol as well as androgens from the adrenal gland. In CAH due to 21 hydroxylase deficiency, excess of ACTH leads to overandrogenization. CAH is due to the enzymatic defect in the cortisol synthesis pathway, with subsequent hypocortisolism, ACTH overproduction, accumulation of androgen precursors, and adrenal gland hyperplasia. Treatment with glucocorticoids at physiological doses is life saving but is not sufficient to suppress the elevated ACTH levels and androgen overproduction. Failure to suppress excess androgens results in height acceleration, advanced skeletal maturation, and eventually leads to decreased final adult height. Other effects of androgen excess include clitoromegaly and hirsutism in females, isosexual pseudoprecocious puberty in males, and acne and deepening of the voice in both sexes. Only supraphysiological doses of glucocorticoids suppress ACTH in CAH but at the cost of hypercortisolemia with its adverse effects such as hyperglycemia, arterial hypertension, reduced growth, and osteoporosis. Since MC2R is expressed only in the adrenals, it could become a specific target. Therefore, an adjuvant drug able to specifically block the MC2R would obviate the need for supraphysiological dose of glucocorticoids in CAH and prevent the undesirable effects inherent to glucocorticoid overtreatment.

MC2R Expressing PBMAH

Primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (also known as ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia) is a rare, sporadic disease affecting men and women with an almost equal ratio. PBMAH has a bimodal age distribution: during the first year of life (minority) when it may be associated with the McCune–Albright syndrome (71) and during the fifth decade of life (majority) (72). Occurrence of familial cases of PBMAH and involvement of both adrenal glands (even in sporadic cases) strongly suggest involvement of germline genetic predisposition in PBMAH. Indeed, inactivating mutations of the armadillo repeat containing 5 (ARMC5) have been reported in 25–55% of patients with sporadic PBMAH (73–75).

The most frequent clinical manifestation of PBMAH is Cushing syndrome. In PBMAH, one previously believed that glucocorticoid secretion is ACTH independent given that, most of the time, plasma ACTH levels are undetectable, and high-dose dexamethasone administration fails to suppress cortisol secretion. This notion has been revised following the demonstration of local production of ACTH. Indeed, Cheitlin et al. studied the adrenal cells from a patient with PBMAH in vitro; the cells were cultured on an extracellular matrix and demonstrated rapid growth and a high rate of cortisol secretion in the absence of ACTH (76). Not only the MC2R was expressed in PBMAH tissue (77) but also ACTH was abnormally expressed, further stimulating the cortisol secretion through a paracrine effect (78). These findings represent a strong incentive to treat PBMAH-associated hypercortisolism with MC2R antagonists. This contrasts with primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease, sporadic large benign adenomas, and adrenocortical carcinomas, which are mostly ACTH unresponsive (79).

Even if these observations suggest that specific MC2R antagonist could help patients with PBMAH, the specific structure of the ACTH produced by PBMAH cells (78) and in ectopic Cushing’s syndrome (80) might raise unexpected difficulties. Indeed, these bioactive ACTH are not detected by antibodies directed to the ACTH C terminal portion. This may result from extrapituitary sources of ACTH producing increased amounts of precursors (pre-ACTH and POMC) due to impaired POMC processing (81, 82). Reports on receptor affinity and steroidogenic potency of ACTH precursors are conflicting (81), which may complicate the design of MC2R antagonists that also block ACTH precursors.

A Specific MC2R Antagonist: An Elusive Target

In the last four decades, extensive studies that have been performed to determine the molecular basis of the interaction of ACTH with cognate MCRs have shown inconsistent results, mainly due to technical limitations. First, the expression at the cell membrane of human MC2R in cell lines was not possible until the discovery of the melanocortin receptor-associated protein (MRAP) (46), which is required to address MC2R at the cell membrane. Second, studies on putative ACTH antagonists failed to perform a systematic analysis of ACTH antagonists’ activation and binding against all cognate MCRs to assess specificity (83, 84).

Melanocortin receptors belong to the GPCRs family that has natural agonists and antagonists. The melanocortin antagonists, agouti-related protein (AGRP) and agouti signaling protein (ASIP), are the only two endogenous antagonists of MCRs identified to date (85–87). The primary sequences of the endogenous agonists (MSHs) and antagonists (AGRP and ASIP) are different, and they interact differently with the MCRs to produce the active and inactive conformations of the ligand–receptor complex.

The design of a specific peptide remains a challenge that has not been resolved because of the difficulty of designing a peptide specific for one MCR (e.g., MC2R) (37). Indeed, all melanocortin ligands receptors shared the same H6F7R8W9 motif, which is important for MCR binding and stimulation (88) and which bind to all MCR receptors. Development of selective ligands for the melanocortin system is challenging due to the conserved amino acid sequences of the MCRs and of their structural similarity in the seven-transmembrane GPCR fold (89). The limited structural variations of the endogenous melanotropin ligands further reduce options in the design of MCR ligands for achieving selectivity. If they are not selective, these peptides could be the source of severe undesirable effects due to the numerous specific roles of the five MCRs. Of note, some ACTH fragments show variable specificity across species. For example, ACTH (7–38) fragment antagonizes the human MC2 receptor but stimulates aldosterone secretion from the rat adrenal cortex through a mechanism involving the angiotensin receptor (90). Variable specificity between species is therefore another challenge for the preclinical phase of the development of new ACTH receptor agonists. A table listing MC2R agonists and antagonists is available in Table S1 in Supplemental Material.

Designing molecules that possess both functional selectivity and human melanocortin receptor (hMCR) subtype selectivity from the melanotropin core sequence H6F7R8W9 has been difficult. Many peptides are conformationally flexible in aqueous solution, but upon interacting with their biologically relevant molecule, they assume a preferred conformation. The reduction of conformational freedom may eventually lead to the receptor bound conformation, which results in the selective interaction of a ligand with a receptor. A major step is to determine which peptide conformation is required for binding to the receptor and resulting in an agonist or antagonist effect. A critical approach is to understand if changes in ACTH three-dimensional (3D) conformation are associated with antagonist properties (Figure 2). X-ray crystal structures provide 3D conformation but may be misleading in terms of function. Incorporation of these X-ray coordinates into a computer-aided examination of function into 3D space is being pursued (91). This allows one to further explore the region/site or the surrounding 3D space occupied by the key amino acids of the protein (where the potent ligand has an affinity) so as to better understand biological actions. Nevertheless, the numerous physiological functions of the five known subtypes of hMCRs continue to be a stimulus for the production of selective melanocortin agonists and antagonists (92).

Conclusion

The ACTH is the pituitary hormone that allows growth and development of the adrenal cortex and glucocorticoid synthesis. Even if the structure of ACTH has been known for decades, the exact mechanism of activation of MC2R, the specific ACTH receptor on adrenal cells, is still unknown. Understanding this activation and the development of specific MC2R antagonists would allow the treatment of some difficult-to-treat diseases such as CAH or PBMAH.

Author Contributions

CG wrote the review and revised the final version; J-MV performed bioinformatic analysis and revised the final version; and JD wrote the review and revised the final version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This work has been supported by Clinical Fellowship Award of the CHU Ste-Justine—Université de Montréal and Academic Medical Interdisciplinary Research Association (AMIR) of the Université Libre de Bruxelles to CG and Clinician-Scientist scholarship of the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé (FRQS) to JD.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fendo.2017.00017/full#supplementary-material.

Abbreviations

ACTH, adrenocorticotropin; PBMAH, primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia; AGRP, agouti-related protein; ASIP, agouti signaling protein; CAH, congenital adrenal hyperplasia; FGD, family glucocorticoid deficiency; MSH, melanocyte-stimulating hormone; MCR, melanocortin receptor; MRAP, melanocortin receptor-associated protein; POMC, proopiomelanocortin.

References

1. Selye H. A syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents. 1936. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci (1998) 10:230–1. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.2.230a

2. Selye H, Collip JB. Fundamental factors in the interpretation of stimuli influencing endocrine glands. Endocrinology (1936) 20:667–72. doi:10.1210/endo-20-5-667

4. Szabo S, Tache Y, Somogyi A. The legacy of Hans Selye and the origins of stress research: a retrospective 75 years after his landmark brief “letter” to the editor# of nature. Stress (2012) 15:472–8. doi:10.3109/10253890.2012.710919

6. Li CH, Geschwind II, Levy AL, Harris JI, Dixon JS, Pon NG, et al. Isolation and properties of alpha-corticotrophin from sheep pituitary glands. Nature (1954) 173:251–3. doi:10.1038/173251b0

7. Li CH, Simpson ME, Evans HM. Isolation of adrenocorticotropic hormone from sheep pituitaries. Science (1942) 96:450. doi:10.1126/science.96.2498.450

8. Ramachandran J, Chung D, Li CH. Synthesis of biologically active peptides related to ACTH. Metabolism (1964) 13(Suppl):1043–58. doi:10.1016/S0026-0495(64)80024-X

9. Nishimura O, Hatanaka C, Fujino M. Synthesis of peptides related to corticotropin (ACTH). IX. Application of N-hydroxy-5-norbornene-2,3-dicarboximide active ester procedure to the synthesis of human adrenocorticotropic hormone (alphah-ACTH). Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) (1975) 23:1212–20.

10. Clayton GW, Bell WR, Guillemin R. Stimulation of ACTH-release in humans by non-pressor fraction from commercial extracts of posterior pituitary. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med (1957) 96:777–9. doi:10.3181/00379727-96-23605

11. Lee TH, Lerner AB, Buettner-Janusch V. On the structure of human corticotropin (adrenocorticotropic hormone). J Biol Chem (1961) 236:2970–4.

12. Guillemin R, Rosenberg B. Humoral hypothalamic control of anterior pituitary: a study with combined tissue cultures. Endocrinology (1955) 57:599–607. doi:10.1210/endo-57-5-599

13. Schwyzer R. ACTH: a short introductory review. Ann N Y Acad Sci (1977) 297:3–26. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb41843.x

14. Lowry PJ, Bennett HP, McMartin C. The isolation and amino acid sequence of an adrenocorticotrophin from the pars distalis and a corticotrophin-like intermediate-lobe peptide from the neurointermediate lobe of the pituitary of the dogfish Squalus acanthias. Biochem J (1974) 141:427–37. doi:10.1042/bj1410427

15. Lowry PJ, Chadwick A. Interrelations of some pituitary hormones. Nature (1970) 226:219–22. doi:10.1038/226219a0

16. Lowry PJ, Scott AP. The evolution of vertebrate corticotrophin and melanocyte stimulating hormone. Gen Comp Endocrinol (1975) 26:16–23. doi:10.1016/0016-6480(75)90211-7

17. Eipper BA, Mains RE. Structure and biosynthesis of pro-adrenocorticotropin/endorphin and related peptides. Endocr Rev (1980) 1:1–27. doi:10.1210/edrv-1-1-1

18. Nakanishi S, Inoue A, Kita T, Nakamura M, Chang AC, Cohen SN, et al. Nucleotide sequence of cloned cDNA for bovine corticotropin-beta-lipotropin precursor. Nature (1979) 278:423–7. doi:10.1038/278423a0

19. Schwyzer R, Sieber P. Total synthesis of adrenocorticotrophic hormone. Nature (1963) 199:172–4. doi:10.1038/199172b0

20. Schiller PW. Study of adrenocorticotropic hormone conformation by evaluation of intramolecular resonance energy transfer in N-dansyllysine 21-ACTH-(1-24)-tetrakosipeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1972) 69:975–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.4.975

21. Squire PG, Bewley T. Adrenocorticotropins. XXXV. The optical rotatory dispersion of sheep adrenocorticotropic hormone in acidic and basic solutions. Biochim Biophys Acta (1965) 109:234–40.

22. Low M, Kisfaludy L, Fermandjian S. Proposed preferred conformation of ACTH. Acta Biochim Biophys Acad Sci Hung (1975) 10:229–31.

23. Schwyzer R. Chemical structure and biological activity in the field of polypeptide hormones. Pure Appl Chem (1963) 6:265–95. doi:10.1351/pac196306030265

24. Schwyzer R. Organization and read-out of biological information in polypeptides. Proc IV Int Congr Pharmacol (1970) 5:196–209.

25. Hruby VJ, Sharma SD, Toth K, Jaw JY, al-Obeidi F, Sawyer TK, et al. Design, synthesis, and conformation of superpotent and prolonged acting melanotropins. Ann N Y Acad Sci (1993) 680:51–63. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb19674.x

26. Samuels ME, Gallo-Payet N, Pinard S, Hasselmann C, Magne F, Patry L, et al. Bioinactive ACTH causing glucocorticoid deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2013) 98:736–42. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3199

27. Dores RM. Adrenocorticotropic hormone, melanocyte-stimulating hormone, and the melanocortin receptors: revisiting the work of Robert Schwyzer: a thirty-year retrospective. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2009) 1163:93–100. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04434.x

28. Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theory Comput (2008) 4:435–47. doi:10.1021/ct700301q

29. Inoue M, Tawata M, Yokomori N, Endo T, Onaya T. Expression of thyrotropin receptor on clonal osteoblast-like rat osteosarcoma cells. Thyroid (1998) 8:1059–64. doi:10.1089/thy.1998.8.1059

30. Schwyzer R, Schiller P, Seelig S, Sayers G. Isolated adrenal cells: log dose response curves for steroidogenesis induced by ACTH(1-24), ACTH(1-10), ACTH(4-10) and ACTH(5-10). FEBS Lett (1971) 19:229–31.

31. Seelig S, Lindley BD, Sayers G. A new approach to the structure-activity relationship for ACTH analogs using isolated adrenal cortex cells. Methods Enzymol (1975) 39:347–59. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(75)39031-9

32. Fauchère JL, Rossier M, Capponi A, Vallotton MB. Potentiation of the antagonistic effect of ACTH11-24 on steroidogenesis by synthesis of covalent dimeric conjugates. FEBS Lett (1985) 183:283–6. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(85)80794-8

33. Feuilloley M, Stolz MB, Delarue C, Fauchère JL, Vaudry H. Structure-activity relationships of monomeric and dimeric synthetic ACTH fragments in perifused frog adrenal slices. J Steroid Biochem (1990) 35:583–92. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(90)90202-4

34. Fauchère JL, Pelican GM. [Specific covalent attachment of adrenocorticotropin and angiotensin II derivatives to polymeric matrices for use in affinity chromatography (author’s transl)]. Helv Chim Acta (1975) 58:1984–94. doi:10.1002/hlca.19750580713

35. Costa JL, Bui S, Reed P, Dores RM, Brennan MB, Hochgeschwender U. Mutational analysis of evolutionarily conserved ACTH residues. Gen Comp Endocrinol (2004) 136:12–6. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2003.11.005

36. Cone RD, Mountjoy KG, Robbins LS, Nadeau JH, Johnson KR, Roselli-Rehfuss L, et al. Cloning and functional characterization of a family of receptors for the melanotropic peptides. Ann N Y Acad Sci (1993) 680:342–63. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb19694.x

37. Cone RD. Studies on the physiological functions of the melanocortin system. Endocr Rev (2006) 27:736–49. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0034

38. Ringholm A, Fredriksson R, Poliakova N, Yan YL, Postlethwait JH, Larhammar D, et al. One melanocortin 4 and two melanocortin 5 receptors from zebrafish show remarkable conservation in structure and pharmacology. J Neurochem (2002) 82:6–18. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00934.x

39. Ringholm A, Klovins J, Fredriksson R, Poliakova N, Larson ET, Kukkonen JP, et al. Presence of melanocortin (MC4) receptor in spiny dogfish suggests an ancient vertebrate origin of central melanocortin system. Eur J Biochem (2003) 270:213–21. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03371.x

40. Begriche K, Girardet C, McDonald P, Butler AA. Melanocortin-3 receptors and metabolic homeostasis. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci (2013) 114:109–46. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386933-3.00004-2

41. Chen W, Kelly MA, Opitz-Araya X, Thomas RE, Low MJ, Cone RD. Exocrine gland dysfunction in MC5-R-deficient mice: evidence for coordinated regulation of exocrine gland function by melanocortin peptides. Cell (1997) 91:789–98. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80467-5

42. Fredriksson R, Schioth HB. The repertoire of G-protein-coupled receptors in fully sequenced genomes. Mol Pharmacol (2005) 67:1414–25. doi:10.1124/mol.104.009001

43. Gallo-Payet N, Battista MC. Steroidogenesis-adrenal cell signal transduction. Compr Physiol (2014) 4:889–964. doi:10.1002/cphy.c130050

44. Gallo-Payet N. 60 years of POMC: adrenal and extra-adrenal functions of ACTH. J Mol Endocrinol (2016) 56:T135–56. doi:10.1530/JME-15-0257

45. Mountjoy KG, Robbins LS, Mortrud MT, Cone RD. The cloning of a family of genes that encode the melanocortin receptors. Science (1992) 257:1248–51. doi:10.1126/science.1325670

46. Metherell LA, Chapple JP, Cooray S, David A, Becker C, Rüschendorf F, et al. Mutations in MRAP, encoding a new interacting partner of the ACTH receptor, cause familial glucocorticoid deficiency type 2. Nat Genet (2005) 37:166–70. doi:10.1038/ng1501

47. Cooray SN, Clark AJ. Melanocortin receptors and their accessory proteins. Mol Cell Endocrinol (2011) 331:215–21. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2010.07.015

48. Hinkle PM, Sebag JA. Structure and function of the melanocortin2 receptor accessory protein (MRAP). Mol Cell Endocrinol (2009) 300:25–31. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2008.10.041

49. Hinkle PM, Serasinghe MN, Jakabowski A, Sebag JA, Wilson KR, Haskell-Luevano C. Use of chimeric melanocortin-2 and -4 receptors to identify regions responsible for ligand specificity and dependence on melanocortin 2 receptor accessory protein. Eur J Pharmacol (2011) 660:94–102. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.10.113

50. Chai BX, Pogozheva ID, Lai YM, Li JY, Neubig RR, Mosberg HI, et al. Receptor-antagonist interactions in the complexes of agouti and agouti-related protein with human melanocortin 1 and 4 receptors. Biochemistry (2005) 44:3418–31. doi:10.1021/bi0478704

51. Pogozheva ID, Chai BX, Lomize AL, Fong TM, Weinberg DH, Nargund RP, et al. Interactions of human melanocortin 4 receptor with nonpeptide and peptide agonists. Biochemistry (2005) 44:11329–41. doi:10.1021/bi0501840

52. Li J, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Villa C, Schertler GF. Structure of bovine rhodopsin in a trigonal crystal form. J Mol Biol (2004) 343:1409–38. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.090

53. Fowler CB, Pogozheva ID, LeVine H III, Mosberg HI. Refinement of a homology model of the mu-opioid receptor using distance constraints from intrinsic and engineered zinc-binding sites. Biochemistry (2004) 43:8700–10. doi:10.1021/bi036067r

54. Davis P, Franquemont S, Liang L, Angleson JK, Dores RM. Evolution of the melanocortin-2 receptor in tetrapods: studies on Xenopus tropicalis MC2R and Anolis carolinensis MC2R. Gen Comp Endocrinol (2013) 188:75–84. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.04.007

55. Meimaridou E, Hughes CR, Kowalczyk J, Guasti L, Chapple JP, King PJ, et al. Familial glucocorticoid deficiency: new genes and mechanisms. Mol Cell Endocrinol (2013) 371:195–200. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2012.12.010

56. Clark AJ, McLoughlin L, Grossman A. Familial glucocorticoid deficiency associated with point mutation in the adrenocorticotropin receptor. Lancet (1993) 341:461–2. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)90208-X

57. Muscatelli F, Strom TM, Walker AP, Zanaria E, Récan D, Meindl A, et al. Mutations in the DAX-1 gene give rise to both X-linked adrenal hypoplasia congenita and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Nature (1994) 372:672–6. doi:10.1038/372672a0

58. Meimaridou E, Kowalczyk J, Guasti L, Hughes CR, Wagner F, Frommolt P, et al. Mutations in NNT encoding nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase cause familial glucocorticoid deficiency. Nat Genet (2012) 44:740–2. doi:10.1038/ng.2299

59. Hasselmann C, Deladoey J, Vuissoz J-M, Patry L, Alirezaie N, Schwartzentruber J, et al. Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT) mutations and using whole exome sequencing to discover potential disease modifiers. J. Genomes Exomes (2013) 2:19–30. doi:10.4137/JGE.S11378

60. Scott R, Van Vliet G, Deladoëy J. Association of adrenal insufficiency with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in a patient with inactivating mutations in nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase: a phenocopy of the animal model. Eur J Endocrinol (2017) 176(3):C1–2. doi:10.1530/EJE-16-0970

61. Prasad R, Chan LF, Hughes CR, Kaski JP, Kowalczyk JC, Savage MO, et al. Thioredoxin Reductase 2 (TXNRD2) mutation associated with familial glucocorticoid deficiency (FGD). J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2014) 99:E1556–63. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-3844

62. Tullio-Pelet A, Salomon R, Hadj-Rabia S, Mugnier C, de Laet MH, Chaouachi B, et al. Mutant WD-repeat protein in triple-A syndrome. Nat Genet (2000) 26:332–5. doi:10.1038/81642

63. Arboleda VA, Lee H, Parnaik R, Fleming A, Banerjee A, Ferraz-de-Souza B, et al. Mutations in the PCNA-binding domain of CDKN1C cause IMAGe syndrome. Nat Genet (2012) 44:788–92. doi:10.1038/ng.2275

64. Hughes CR, Guasti L, Meimaridou E, Chuang CH, Schimenti JC, King PJ, et al. MCM4 mutation causes adrenal failure, short stature, and natural killer cell deficiency in humans. J Clin Invest (2012) 122:814–20. doi:10.1172/JCI60224

65. Narumi S, Amano N, Ishii T, Katsumata N, Muroya K, Adachi M, et al. SAMD9 mutations cause a novel multisystem disorder, MIRAGE syndrome, and are associated with loss of chromosome 7. Nat Genet (2016) 48:792–7. doi:10.1038/ng.3569

66. Krude H, Biebermann H, Luck W, Horn R, Brabant G, Grüters A. Severe early-onset obesity, adrenal insufficiency and red hair pigmentation caused by POMC mutations in humans. Nat Genet (1998) 19:155–7. doi:10.1038/509

67. Challis BG, Pritchard LE, Creemers JW, Delplanque J, Keogh JM, Luan J, et al. A missense mutation disrupting a dibasic prohormone processing site in pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) increases susceptibility to early-onset obesity through a novel molecular mechanism. Hum Mol Genet (2002) 11:1997–2004. doi:10.1093/hmg/11.17.1997

68. Lee YS, Challis BG, Thompson DA, Yeo GS, Keogh JM, Madonna ME, et al. A POMC variant implicates beta-melanocyte-stimulating hormone in the control of human energy balance. Cell Metab (2006) 3:135–40. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.006

69. Krude H, Biebermann H, Schnabel D, Tansek MZ, Theunissen P, Mullis PE, et al. Obesity due to proopiomelanocortin deficiency: three new cases and treatment trials with thyroid hormone and ACTH4-10. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2003) 88:4633–40. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-030502

70. Kühnen P, Clément K, Wiegand S, Blankenstein O, Gottesdiener K, Martini LL, et al. Proopiomelanocortin deficiency treated with a melanocortin-4 receptor agonist. N Engl J Med (2016) 375:240–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1512693

71. Kirk JM, Brain CE, Carson DJ, Hyde JC, Grant DB. Cushing’s syndrome caused by nodular adrenal hyperplasia in children with McCune-Albright syndrome. J Pediatr (1999) 134:789–92. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70302-1

72. Lieberman SA, Eccleshall TR, Feldman D. ACTH-independent massive bilateral adrenal disease (AIMBAD): a subtype of Cushing’s syndrome with major diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Eur J Endocrinol (1994) 131:67–73. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1310067

73. Assié G, Libé R, Espiard S, Rizk-Rabin M, Guimier A, Luscap W, et al. ARMC5 mutations in macronodular adrenal hyperplasia with Cushing’s syndrome. N Engl J Med (2013) 369:2105–14. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1304603

74. Espiard S, Drougat L, Libé R, Assié G, Perlemoine K, Guignat L, et al. ARMC5 mutations in a large cohort of primary macronodular adrenal hyperplasia: clinical and functional consequences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2015) 100:E926–35. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-4204

75. Fragoso MC, Alencar GA, Lerario AM, Bourdeau I, Almeida MQ, Mendonca BB, et al. Genetics of primary macronodular adrenal hyperplasia. J Endocrinol (2015) 224:R31–43. doi:10.1530/JOE-14-0568

76. Cheitlin RA, Westphal M, Cabrera CM, Fujii DK, Snyder J, Fitzgerald PA. Cushing’s syndrome due to bilateral adrenal macronodular hyperplasia with undetectable ACTH: cell culture of adenoma cells on extracellular matrix. Horm Res (1988) 29:162–7. doi:10.1159/000180995

77. Bourdeau I, D’Amour P, Hamet P, Boutin JM, Lacroix A. Aberrant membrane hormone receptors in incidentally discovered bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2001) 86:5534–40. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.11.8062

78. Louiset E, Duparc C, Young J, Renouf S, Tetsi Nomigni M, Boutelet I, et al. Intraadrenal corticotropin in bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia. N Engl J Med (2013) 369:2115–25. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215245

79. Matsukura S, Kakita T, Sueoka S, Yoshimi H, Hirata Y, Yokota M, et al. Multiple hormone receptors in the adenylate cyclase of human adrenocortical tumors. Cancer Res (1980) 40:3768–71.

80. Smallridge RC, Bourne K, Pearson BW, Van Heerden JA, Carpenter PC, Young WF. Cushing’s syndrome due to medullary thyroid carcinoma: diagnosis by proopiomelanocortin messenger ribonucleic acid in situ hybridization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2003) 88:4565–8. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021796

81. Stewart PM, Gibson S, Crosby SR, Penn R, Holder R, Ferry D, et al. ACTH precursors characterize the ectopic ACTH syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (1994) 40:199–204. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb02468.x

82. Gibson S, Ray DW, Crosby SR, Dornan TL, Jennings AM, Bevan JS, et al. Impaired processing of proopiomelanocortin in corticotroph macroadenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1996) 81:497–502. doi:10.1210/jcem.81.2.8636257

83. Kovalitskaya YA, Zolotarev YA, Kolobov AA, Sadovnikov VB, Yurovsky VV, Navolotskaya EV. Interaction of ACTH synthetic fragments with rat adrenal cortex membranes. J Pept Sci (2007) 13:513–8. doi:10.1002/psc.873

84. Kapas S, Cammas FM, Hinson JP, Clark AJ. Agonist and receptor binding properties of adrenocorticotropin peptides using the cloned mouse adrenocorticotropin receptor expressed in a stably transfected HeLa cell line. Endocrinology (1996) 137:3291–4. doi:10.1210/en.137.8.3291

85. Nijenhuis WA, Oosterom J, Adan RA. AgRP(83-132) acts as an inverse agonist on the human-melanocortin-4 receptor. Mol Endocrinol (2001) 15:164–71. doi:10.1210/mend.15.1.0578

86. Yang YK, Dickinson C, Lai YM, Li JY, Gantz I. Functional properties of an agouti signaling protein variant and characteristics of its cognate radioligand. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol (2001) 281:R1877–86.

87. McNulty JC, Jackson PJ, Thompson DA, Chai B, Gantz I, Barsh GS, et al. Structures of the agouti signaling protein. J Mol Biol (2005) 346:1059–70. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.030

88. Hruby VJ, Wilkes BC, Hadley ME, Al-Obeidi F, Sawyer TK, Staples DJ, et al. Alpha-melanotropin: the minimal active sequence in the frog skin bioassay. J Med Chem (1987) 30:2126–30. doi:10.1021/jm00394a033

89. Barrett P, MacDonald A, Helliwell R, Davidson G, Morgan P. Cloning and expression of a new member of the melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor family. J Mol Endocrinol (1994) 12:203–13. doi:10.1677/jme.0.0120203

90. Malendowicz LK, Rebuffat P, Nussdorfer GG, Nowak KW. Corticotropin-inhibiting peptide enhances aldosterone secretion by dispersed rat zona glomerulosa cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol (1998) 67:149–52. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(98)00081-8

91. Cai M, Hruby VJ. The melanocortin receptor system: a target for multiple degenerative diseases. Curr Protein Pept Sci (2016) 17(5):488–96. doi:10.2174/1389203717666160226145330

Keywords: stress, cortisol, adrenals, ACTH, antagonist

Citation: Ghaddhab C, Vuissoz J-M and Deladoëy J (2017) From Bioinactive ACTH to ACTH Antagonist: The Clinical Perspective. Front. Endocrinol. 8:17. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00017

Received: 11 October 2016; Accepted: 18 January 2017;

Published: 08 February 2017

Edited by:

Andre Lacroix, Université de Montréal, CanadaCopyright: © 2017 Ghaddhab, Vuissoz and Deladoëy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Johnny Deladoëy, am9obm55LmRlbGFkb2V5QHVtb250cmVhbC5jYQ==

Chiraz Ghaddhab

Chiraz Ghaddhab Jean-Marc Vuissoz2

Jean-Marc Vuissoz2 Johnny Deladoëy

Johnny Deladoëy