94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Endocrinol., 03 July 2015

Sec. Cancer Endocrinology

Volume 6 - 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2015.00106

This article is part of the Research TopicThe role of the Insulin/IGFs system in cancer: critical points in dysregulation, targeting problems and new blocking strategiesView all 17 articles

IGF-1R expression and activation levels generally cannot be correlated in cancer cells, suggesting that cellular proteins may modulate IGF-1R activity. Strong candidates for such modulation are found in cell-matrix and cell–cell adhesion signaling complexes. Activated IGF-1R is present at focal adhesions, where it can stabilize β1 integrin and participate in signaling complexes that promote invasiveness associated with epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) and resistance to therapy. Whether IGF-1R contributes to EMT or to non-invasive tumor growth may be strongly influenced by the degree of extracellular matrix engagement and the presence or absence of key proteins in IGF-1R-cell adhesion complexes. One such protein is PDLIM2, which promotes both cell polarization and EMT by regulating the stability of transcription factors including NFκB, STATs, and beta catenin. PDLIM2 exhibits tumor suppressor activity, but is also highly expressed in certain invasive cancers. It is likely that distinct adhesion complex proteins modulate IGF-1R signaling during cancer progression or adaptive responses to therapy. Thus, identifying the key modulators will be important for developing effective therapeutic strategies and predictive biomarkers.

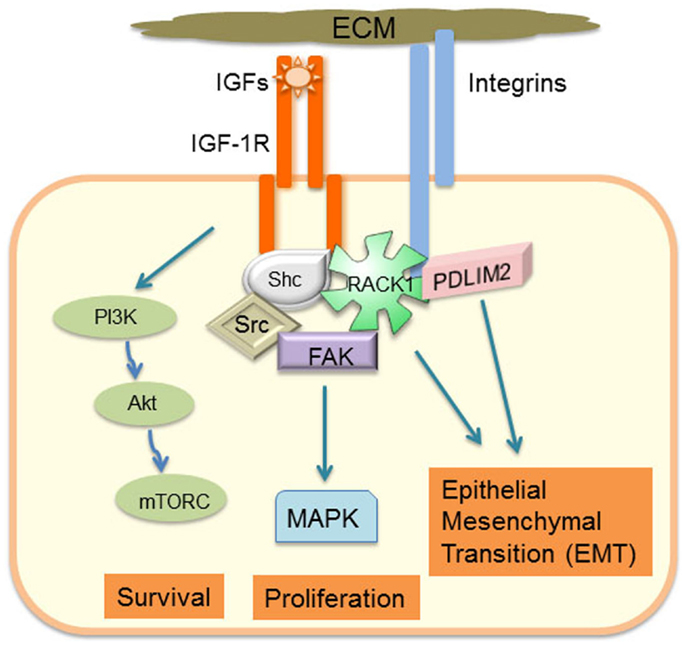

Dynamic cooperative signaling interactions between the IGF-1R and integrins are necessary for the growth and migration of normal cells and also for invasiveness and metastasis of cancer cells. Examples include how in normal cells, IGF-1R expression and activation are required for fibroblast migration, integrating signals from the extracellular matrix (ECM) via β1 integrin and RACK1 scaffolding protein (1–4) (summarized in Figure 1). In vascular smooth muscle cells, IGF-1 stimulated cell migration and division requires αvβ3 integrin cooperation [reviewed in Ref. (5)]. α5β1 integrin signaling is strongly interactive with IGF-1R signaling in prostate cancer cells, and IGF-1R has been shown both to associate with and enhance the stability of β1 integrin (6). Furthermore, the IGF-1R interaction with αv integrin in both normal and colon cancer cells is disrupted upon IGF-1 stimulation, which correlates with increased cell migration (7).

Figure 1. Schematic model of how adhesion-regulated IGF-1R signaling has a critical role in determining cancer cell phenotype.

In addition to its well-described role in cooperative signaling with integrins to promote normal cell growth and migration [reviewed in Ref. (8, 9)], IGF-1R and integrin collaborative signaling in cancer cells is implicated with an epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype (10–12). IGF-1R can promote integrin stability, and in prostate tumor models, integrin expression is required for growth in vivo and proliferation in vitro (6, 13). Alternations and co-expression of IGF-1R and adhesion signaling components have been reported in several different cancers. For example, a recent analysis of IGF-1 and ECM-induced signaling components in metastatic breast tumors demonstrated that compared with normal or primary cancer tissues, β1 integrin and fibronectin are more clearly co-located at the leading edge of tumors, which also correlates with active Akt and Erks (14).

Integrin engagement leads to formation of transient nascent adhesions that can mature into focal adhesions tethered to actin stress fibers. The assembly and disassembly of these focal adhesions is necessary for cell migration and involves coordinated activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), Src, and Rho GTPases (15). Activated IGF-1R can be recruited into a signaling complex with β1 integrin via scaffolding with RACK1 and FAK (1–4, 6, 16, 17) (Figure 1). RACK1 acts as a scaffold to facilitate activation of FAK, and IGF-1 stimulates dephosphorylation of FAK, which is associated with dissolution of focal adhesions (2, 18, 19). This complex contains key IGF-1-responsive signaling components, including IRS-1, IRS-2, Shc, Src, PP2A, Shp-2, and c-Abl, which have a particular role in regulating activity of the Erk signaling cascade. Indeed, cell adhesion or integrin ligation is required for optimal IGF-1-mediated activation of Shc and Erks (5, 20, 21). The intensity and duration of Erk phosphorylation in response to IGF-1 in the presence of cell adhesion may be a key determinant of cell phenotype and, in particular, EMT potential of cancer cells. For example, RACK1 over-expression biases the IGF signaling response toward increased Erk phosphorylation with concomitant increases in IGF-1 mediated cell proliferation and migration (1). G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) engagement is also a component of adhesion-regulated IGF signaling [reviewed in Ref. (22)], which biases IGF-1-mediated Erk activation (23). Several extracellular matrix and intracellular proteins have the potential to influence the level of IGF-1R association with adhesion receptors and subsequent signaling. These include ECM components, such as fibronectin and collagen; proteoglycans, such as decorin, which regulates IGF-1R activation levels and internalization (24); and IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs) that can associate with ECM proteins and modulate IGF ligand activity or adhesion signaling (25, 26). Recent studies have also implicated the discoid domain receptor 1 (DDR1), which is a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that becomes activated by collagen ligation (27, 28), and may be important for cell matrix adhesion and growth regulation. DDR1 is also over-expressed in many cancers (28) and it associates with the IGF-1R (29). DDR1 association with the IGF-1R regulates IGF-1R trafficking and expression levels and promotes collagen-dependent and -independent phosphorylation of DDR1. Hence, DDR1 is a newly characterized adhesion receptor that regulates IGF-1R expression and signaling in cancer cells (29). Interestingly, cancer genome sequencing studies indicate that head and neck cancers have many alterations in both IGF-1R and the DDR2 collagen receptor (http://cancergenome.nih.gov). Thus, IGF-1R levels alone will not necessarily determine cancer cell responses to IGF-1 and anti-IGF-1R therapies, as IGF-1R activity and downstream signaling are influenced by adhesion signals and activation of other signaling pathways, which are discussed further below.

IGF-1R can be found associated with E-cadherin in cell–cell adhesion complexes of normal corneal epithelial cells (30) and in several cancer cell types (7, 31–34). IGF-1 can stimulate cell–cell adhesion associated with survival and reduced migration in both 2D and 3D models (31, 32, 34). Indeed, in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, IGF-1R interacts with, and regulates expression of the scaffolding protein zonula occludens protein 1 (ZO-1) at E-cadherin complexes, thereby enhancing the E-cadherin-mediated cell–cell adhesion (32, 34). However, IGF-1R activation can also promote cell migration in both normal and cancer cells [reviewed in Ref. (9, 35, 36)]. Whether IGF-1R promotes cell adhesion or disruption of the E-cadherin adhesion complexes appears to be cell-type specific. For example, it has been shown that the interaction of active IGF-1R and E-cadherin is required for normal murine blastocyst formation (37). However, activation of the IGF-1R by either IGF-1 (38) or IGF-II (33) has been also shown to disrupt cell–cell contacts with concomitant redistribution of E-Cadherin and beta catenin from cell adhesion complexes to the cytoplasm or cytoplasm and nucleus, respectively, which is permissive to EMT and cell migration (7, 33). Integrin engagement by ECM is associated with dissolution of cell–cell junctions, and the integrin-activated signaling pathway to FAK, Src, and small GTPases (including RhoA), and Rho Kinase can promote phosphorylation of adherence junction proteins or the stability of E-cadherin expression (15). There is also evidence for regulation of integrin adhesion by adherens junctions (AJ), where a key signaling intermediary is thought to be the Ras family GTPase Ras-related protein 1 (Rap1), which becomes activated upon AJ disassembly and is associated with focal adhesion formation (39). Interestingly, activated IGF-IR also transiently activates Rap1 and recruits it to sites of cell motile protrusion, whereas Rap1 remains in site of cell–cell contact in the absence of IGF-1R activation (40). IGF-1R and Rap1 expressions were both reported to exhibit increased expression in invasive breast cancer (41), again suggesting that IGF-1R contributes to the invasive switch in cancer.

Adhesion signaling in cooperation with IGF-1R may have an important role in the responses of cells to kinase inhibitors, chemotherapeutic agents, and other therapies. This adaptive response may be related to an EMT phenotype, whereby cells acquire a mesenchymal phenotype allowing them to invade and migrate and has also been likened to a stem-like phenotype. IGF-1 can induce transcription of drivers of EMT including the E-cadherin transcriptional regulators, Snail and Zeb (33, 42–45). In ovarian cell models, mechanisms of adaptive resistance to PI3-K/mTOR inhibitors were attributed to extracellular matrix attachment accompanied by up-regulation of IGF-1R and other pro-survival proteins (46). Recent reports on IGF-1R and Her2 cooperation in invasiveness also indicate that the major biological effect facilitated by IGF-1R is invasion mediated by Src and FAK (47). The authors suggest that this effect is very likely to depend on integrin signaling, which would indeed be consistent with the published studies on Src, FAK, and integrin action in IGF-1R signaling.

A dataset for IGF-1-mediated activation of Akt and Erks in 50 breast cancer cell lines is available in the library of integrated network-based cellular signatures (LINCS) consortium website from a study by Niepel et al., which collated the responses to ligand stimulation and tyrosine kinase inhibitors for a panel of growth factors (48, 49). It is clear from this dataset that IGF-1R expression levels vary substantially across the 50 cell lines and that autophosphorylation on Y1131 (activity) of the IGF-1R does not necessarily correlate with receptor levels or downstream signaling events. This implies regulation or biasing of IGF-1R activity and signaling output by other signaling pathways, as discussed in the previous section. These pathways may include those activated by fibroblast growth factor (FGF), which biases toward Erk signaling in this study (48), epidermal growth factor (EGF), c-Met, or the Wnt signaling pathway (50–53). It is also becoming increasingly clear that expression and activation of these pathways may have important implications for responses to anti-IGF-1R therapy, as has been shown for DVL3 signaling (54).

In addition to its role in stem cell renewal, the Wnt pathway is increasingly recognized as an important driver of EMT, although the mechanisms and interactions with RTK and adhesion signaling are not yet well understood [reviewed in Ref. (52)]. Wnt signaling acts through 10 known seven-transmembrane Frizzled (Fzd) family receptors and three Disheveled (DVL) isoforms (55, 56), which can activate either a canonical signaling pathway through beta catenin; a non-canonical pathway that includes Rho, Rac, PKCs, Jnk, and other proteins; or the alternative Wnt 5/Fzd2 pathway that is mediated by STAT3 and Fyn kinase (57). IGF-1R signaling can intersect with the canonical Wnt pathway at the level of GSK3 beta phosphorylation and inactivation, leading to stabilization and transcriptional activation of beta catenin. IGF-1R inhibition also modifies Wnt pathway activity (58), and Wnt pathway components may modulate IGF-1R signaling (54). DVL3, a component of Wnt signaling pathways, was recently identified as a modifier of response to IGF-1R antibody or tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and DVL3 expression can alter the kinetics of IGF-1-mediated Erk activity (54). There is also evidence for altered levels of these Wnt pathway proteins in different stages of cancer differentiation and regulation of canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling during cancer progression (59–61).

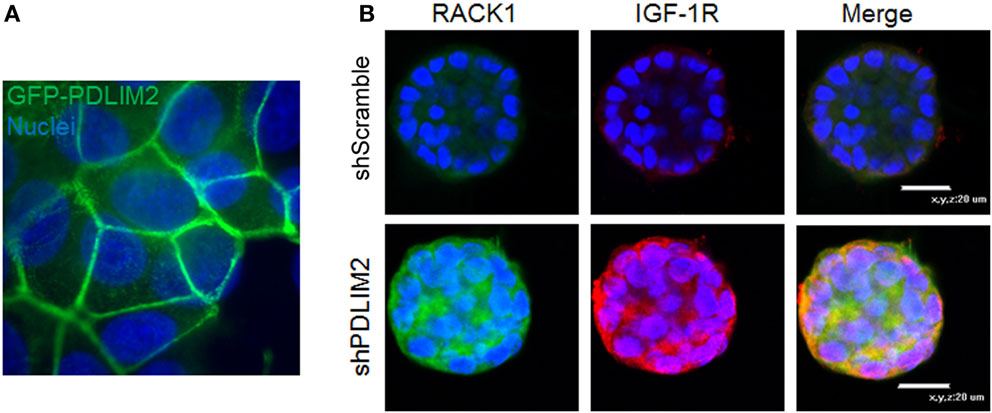

The ability of cancer cells to invade, undergo reversible EMT, and retain stemness requires integrating gene expression with cytoskeleton dynamics and cell shape in response to cues from the extracellular matrix. PDLIM2 is an IGF-1 regulated cytoskeleton and nuclear protein that is also located in cell–cell and cell-matrix adhesion complexes (62, 63) (Figure 2A). PDLIM2 is expressed in epithelial cells, may be repressed in cancer, and is also highly expressed in cancer cells that exhibit an EMT phenotype (62–67). The pdlim2 gene is located on chromosome 8p21, a region that is disrupted in many cancers and associated with metastasis (68). PDLIM2 regulates protein stability and expression of the key EMT markers, E-cadherin and Snail (63). Moreover, PDLIM2 regulates STAT and NFκB transcription factors and cytoskeleton function in inflammatory leukocytes, and the beta catenin transcriptional output in epithelial cells (63, 69–71). Suppression of PDLIM2 in normal MCF10A myoepithelial cells in 3D matrigel cultures leads to cell transformation, which, interestingly, is accompanied by markedly increased expression of both IGF-1R and RACK1 (Figure 2B). In addition, loss of PDLIM2 inhibits cell polarization and causes up-regulation of β1 integrin expression, and subsequent hyper-activation of downstream signaling through the FAK-RhoA-cofilin axis that can be reversed by pharmacological inhibition of FAK or Rho Kinases (67). Suppression of PDLIM2 in invasive cancer cells (DU145, MDA-MB-231) causes increased E-cadherin expression and cell–cell contact, loss of directional migration, altered expression and activity of many transcription factors associated with tumorigenesis, and reversal of EMT (63).

Figure 2. (A) PDLIM2 is expressed at cell–cell adhesions: MCF-7 cells overexpressing GFP-PDLIM2 were seeded on coverslips and cultured to confluency in complete growth medium (DMEM and 10% FBS) for 48 h. Cells were fixed and nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye (blue). Cells were photographed at the focus plane of cell adhesion to the coverslip to demonstrate the location of GFP-PDLIM2 (green). Nuclei are shown in slightly different focus plane in the background. Note: nuclei appear to be larger or overlapping compared with GFP-PDLIM2 expression between the cells because GFP-PDLIM2 outlines the area of the cell that is adhered to the coverslip, which in a confluent monolayer, adopts to different shapes and sizes that do not represent the full body of the cell. (B) Suppression of PDLIM2 causes increased expression of IGF-1R and the scaffolding protein, RACK1. Control MCF10A cells (shScramble) or MCF10A cells with PDLIM2 expression stably suppressed (shPDLIM2) were cultured in a 3D Matrigel assay for 12 days. Cell structures were fixed and processed for confocal microscopy analysis for RACK1 (green) and IGF-1R (red) expression and nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue), as described in Ref. (67).

Since PDLIM2 silencing impairs the formation of polarized acinar structures and also suppresses EMT and directional migration, it regulates both E-cadherin-mediated cell–cell adhesion and ECM-Integrin activated signaling. This is consistent with a function as a cytoskeleton to nucleus courier protein, integrating signals from sites of cell adhesion with the cytoskeleton to gene expression in the nucleus. The presence of PDLIM2 in both cell–cell adhesion and cell–matrix adhesion complexes also suggests a role in signaling crosstalk. The most likely mechanisms for this are through controlling protein stability of key components of the adhesion complexes and the activity of their transcriptional regulators. PDLIM2 associates with the Cop9 signalosome [in particular, the CSN5 subunit (JAB1)], which regulates the activity of Cullin-E3 ligase complexes and protein degradation (63). However, it is not yet clear whether PDLIM2 function in adhesion complexes contributes directly to protein stability in these complexes or is associated with its sequestration away from the nucleus to enhance stability of transcription factors. Identifying the key targets of PDLIM2 within adhesion complexes will be necessary to establish its precise function.

The insulin receptor isoform A (IR-A) has been firmly established as an important contributor to cancer phenotype, in particular, by promoting the renewal and survival of cancer stem cells and mediating responses to environmental conditions including hyperglycemia [reviewed in Ref. (10, 72, 73)] and resistance to IGF-1R-targeted therapies (74). Since cancer stem cell growth may require switching on an EMT phenotype, it will be interesting to establish whether the IGF-1R and IR-A function differently in cooperation with adhesion signaling. This issue is complicated by the fact that IGF-1R is activated preferentially by IGF-1 and the IR-A by IGF-2, and ligand-induced internalization and trafficking of the receptors may be different in response to ligand stimulation (29, 75, 76). Another key difference may reside in signaling or its regulation by the C terminal tails of these receptors. This region of the receptor exhibits least (approximately 40%) homology. In particular, the 1248-SFYYS-1252 motif in the C terminal tail of the IGF-1R lacks tyrosines in the IR and has the amino acid sequence SFFHS. Substitution of the tyrosines Y1250/Y1251 with phenylalanine in the IGF-1R is sufficient to impair recruitment of the IGF-1R into a complex with β1 integrin, and disrupt cooperative signaling and cytoskeleton organization (2, 77). Substitution of serine S1248 with alanine in the IGF-1R impairs migration slightly but increases ligand-independent survival (78). Internalization and trafficking of these mutant receptors is also impaired, but it remains to be determined whether the actions of this motif of the C terminal tails can distinguish between IGF-1R and IR-A activity and whether they behave similarly in cancer stem cell renewal and in promoting cell invasiveness in EMT. IGF-1R signaling adaptation may also be associated with DNA damage-directed therapy. Initial resistance to cisplatin in ovarian cancer has been associated with increased IGF-1R expression, whereas IGF-1R expression levels decrease in later stages of resistance (79). This again indicates an adaptation that involves suppression of IGF-1R expression levels, but not necessarily activity. Taken together, it is clear that IGF-1R expression is highly adaptable during cancer progression. It can cooperate with many other signaling pathways and may be influenced by different cellular responses and phenotypes. Thus, it may be a major contributor to cancer cell escape, survival, and ability to activate redundant cellular signaling pathways.

IGF-1R signaling at focal adhesion complexes and its interplay with adhesion/cytoskeleton signaling has a critical role in cellular transformation, EMT, therapy resistance, and the plasticity of cancer cells. In addition to altered kinetics of canonical Akt and Erk signaling pathways, it is intimately involved in complex bi-directional cytoskeletal–nuclear signaling to determine gene expression necessary for cell polarity and phenotypic changes. Determining the key regulators of IGF-1R expression and how their expression is regulated in phenotypically distinct cancers may unlock new ways to target invasiveness and resistance to kinase inhibitors and conventional cancer therapies.

OC and RC prepared the manuscript. OC, SS, ET, MG, and RD reviewed manuscript and contributed to the design, execution, and interpretation of experiments for data, either published or unpublished, referred to in the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We are grateful to our colleagues in the Cell Biology Laboratory. We acknowledge funding by the Breast Cancer Campaign (2008NovPR24), Science Foundation Ireland (PI awards 07/INI/β107 and 11/PI/1136), the Health Research Board (HRA 2009/41), and the Irish Cancer Society Collaborative Cancer Research Centre BREAST-PREDICT Grant CCRC13GAL.

ECM, extracellular matrix; EMT, epithelial to mesenchymal transition; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor; IRS-1(2), insulin receptor substrate 1(2); NFκB, nuclear factor κB; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription.

1. Kiely PA, Sant A, O’Connor R. RACK1 is an insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor-interacting protein that can regulate IGF-1-mediated Akt activation and protection from cell death. J Biol Chem (2002) 277:22581–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201758200

2. Kiely PA, Leahy M, O’Gorman D, O’Connor R. RACK1-mediated integration of adhesion and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) signaling and cell migration are defective in cells expressing an IGF-I receptor mutated at tyrosines 1250 and 1251. J Biol Chem (2005) 280:7624–33. doi:10.1074/jbc.M412889200

3. Kiely PA, O’Gorman D, Luong K, Ron D, O’Connor R. Insulin-like growth factor I controls a mutually exclusive association of RACK1 with protein phosphatase 2A and β1 integrin to promote cell migration. Mol Cell Biol (2006) 26:4041–51. doi:10.1128/MCB.01868-05

4. Kiely PA, Baillie GS, Lynch MJ, Houslay MD, O’Connor R. Tyrosine 302 in RACK1 is essential for insulin-like growth factor-I-mediated competitive binding of PP2A and β1 integrin and for tumor cell proliferation and migration. J Biol Chem (2008) 283:22952–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.M800802200

5. Clemmons DR, Maile LA. Interaction between insulin-like growth factor-I receptor and alphaVbeta3 integrin linked signaling pathways: cellular responses to changes in multiple signaling inputs. Mol Endocrinol (2005) 19:1–11. doi:10.1210/me.2004-0376

6. Sayeed A, Fedele C, Trerotola M, Ganguly KK, Languino LR. IGF-IR promotes prostate cancer growth by stabilizing alpha5beta1 integrin protein levels. PLoS One (2013) 8:e76513. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076513

7. Canonici A, Steelant W, Rigot V, Khomitch-Baud A, Boutaghou-Cherid H, Bruyneel E, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor, E-cadherin and alpha v integrin form a dynamic complex under the control of alpha-catenin. Int J Cancer (2008) 122:572–82. doi:10.1002/ijc.23164

8. Clemmons DR, Maile LA. Minireview: integral membrane proteins that function coordinately with the insulin-like growth factor I receptor to regulate intracellular signaling. Endocrinology (2003) 144:1664–70. doi:10.1210/en.2002-221102

9. Guvakova MA. Insulin-like growth factors control cell migration in health and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (2007) 39:890–909. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2006.10.013

10. Malaguarnera R, Frasca F, Garozzo A, Giani F, Pandini G, Vella V, et al. Insulin receptor isoforms and insulin-like growth factor receptor in human follicular cell precursors from papillary thyroid cancer and normal thyroid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2011) 96:766–74. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-1255

11. Chen WJ, Ho CC, Chang YL, Chen HY, Lin CA, Ling TY, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts regulate the plasticity of lung cancer stemness via paracrine signalling. Nat Commun (2014) 5:3472. doi:10.1038/ncomms4472

12. Kim IG, Kim SY, Choi SI, Lee JH, Kim KC, Cho EW. Fibulin-3-mediated inhibition of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and self-renewal of ALDH+ lung cancer stem cells through IGF1R signaling. Oncogene (2014) 33:3908–17. doi:10.1038/onc.2013.373

13. Goel HL, Breen M, Zhang J, Das I, Aznavoorian-Cheshire S, Greenberg NM, et al. beta1A integrin expression is required for type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor mitogenic and transforming activities and localization to focal contacts. Cancer Res (2005) 65:6692–700. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4315

14. Plant HC, Kashyap AS, Manton KJ, Hollier BG, Hurst CP, Stein SR, et al. Differential subcellular and extracellular localisations of proteins required for insulin-like growth factor- and extracellular matrix-induced signalling events in breast cancer progression. BMC Cancer (2014) 14:627. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-14-627

15. Canel M, Serrels A, Frame MC, Brunton VG. E-cadherin-integrin crosstalk in cancer invasion and metastasis. J Cell Sci (2013) 126:393–401. doi:10.1242/jcs.100115

16. Beattie J, Mcintosh L, van der Walle CF. Cross-talk between the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) axis and membrane integrins to regulate cell physiology. J Cell Physiol (2010) 224:605–11. doi:10.1002/jcp.22183

17. Sayeed A, Alam N, Trerotola M, Languino LR. Insulin-like growth factor 1 stimulation of androgen receptor activity requires β1A integrins. J Cell Physiol (2012) 227:751–8. doi:10.1002/jcp.22784

18. Guvakova MA, Surmacz E. The activated insulin-like growth factor I receptor induces depolarization in breast epithelial cells characterized by actin filament disassembly and tyrosine dephosphorylation of Fak, Cas, and paxillin. Exp Cell Res (1999) 251:244–55. doi:10.1006/excr.1999.4566

19. Kiely PA, Baillie GS, Barrett R, Buckley DA, Adams DR, Houslay MD, et al. Phosphorylation of RACK1 on tyrosine 52 by c-Abl is required for insulin-like growth factor i-mediated regulation of focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem (2009) 284:20263–74. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.017640

20. Weng LP, Smith WM, Brown JL, Eng C. PTEN inhibits insulin-stimulated MEK/MAPK activation and cell growth by blocking IRS-1 phosphorylation and IRS-1/Grb-2/Sos complex formation in a breast cancer model. Hum Mol Genet (2001) 10:605–16. doi:10.1093/hmg/10.6.605

21. Leahy M, Lyons A, Krause D, O’Connor R. Impaired Shc, Ras, and MAPK activation but normal Akt activation in FL5.12 cells expressing an insulin-like growth factor I receptor mutated at tyrosines 1250 and 1251. J Biol Chem (2004) 279:18306–13. doi:10.1074/jbc.M309234200

22. Crudden C, Girnita A, Girnita L. Targeting the IGF-1R: the tale of the tortoise and the hare. Front Endocrinol (2015) 6:64. doi:10.3389/fendo.2015.00064

23. Zheng H, Worrall C, Shen H, Issad T, Seregard S, Girnita A, et al. Selective recruitment of G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) controls signaling of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109:7055–60. doi:10.1073/pnas.1118359109

24. Iozzo RV, Buraschi S, Genua M, Xu SQ, Solomides CC, Peiper SC, et al. Decorin antagonizes IGF receptor I (IGF-IR) function by interfering with IGF-IR activity and attenuating downstream signaling. J Biol Chem (2011) 286:34712–21. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.262766

25. Burrows C, Holly JM, Laurence NJ, Vernon EG, Carter JV, Clark MA, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 has opposing actions on malignant and nonmalignant breast epithelial cells that are each reversible and dependent upon cholesterol-stabilized integrin receptor complexes. Endocrinology (2006) 147:3484–500. doi:10.1210/en.2006-0005

26. Kashyap AS, Hollier BG, Manton KJ, Satyamoorthy K, Leavesley DI, Upton Z. Insulin-like growth factor-I:vitronectin complex-induced changes in gene expression effect breast cell survival and migration. Endocrinology (2011) 152:1388–401. doi:10.1210/en.2010-0897

27. Vogel W, Gish GD, Alves F, Pawson T. The discoidin domain receptor tyrosine kinases are activated by collagen. Mol Cell (1997) 1:13–23. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80003-9

28. Valiathan RR, Marco M, Leitinger B, Kleer CG, Fridman R. Discoidin domain receptor tyrosine kinases: new players in cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev (2012) 31:295–321. doi:10.1007/s10555-012-9346-z

29. Malaguarnera R, Nicolosi ML, Sacco A, Morcavallo A, Vella V, Voci C, et al. Novel cross talk between IGF-IR and DDR1 regulates IGF-IR trafficking, signaling and biological responses. Oncotarget (2015).

30. Robertson DM, Zhu M, Wu YC. Cellular distribution of the IGF-1R in corneal epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res (2012) 94:179–86. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2011.12.006

31. Guvakova MA, Surmacz E. Overexpressed IGF-I receptors reduce estrogen growth requirements, enhance survival, and promote E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion in human breast cancer cells. Exp Cell Res (1997) 231:149–62. doi:10.1006/excr.1996.3457

32. Mauro L, Bartucci M, Morelli C, Ando S, Surmacz E. IGF-I receptor-induced cell-cell adhesion of MCF-7 breast cancer cells requires the expression of junction protein ZO-1. J Biol Chem (2001) 276:39892–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106673200

33. Morali OG, Delmas V, Moore R, Jeanney C, Thiery JP, Larue L. IGF-II induces rapid beta-catenin relocation to the nucleus during epithelium to mesenchyme transition. Oncogene (2001) 20:4942–50. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204660

34. Mauro L, Salerno M, Morelli C, Boterberg T, Bracke ME, Surmacz E. Role of the IGF-I receptor in the regulation of cell-cell adhesion: implications in cancer development and progression. J Cell Physiol (2003) 194:108–16. doi:10.1002/jcp.10207

35. Leventhal PS, Feldman EL. Insulin-like growth factors as regulators of cell motility signaling mechanisms. Trends Endocrinol Metab (1997) 8:1–6. doi:10.1016/S1043-2760(96)00202-0

36. LeRoith D, Roberts CT Jr. The insulin-like growth factor system and cancer. Cancer Lett (2003) 195:127–37. doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00159-9

37. Bedzhov I, Liszewska E, Kanzler B, Stemmler MP. Igf1r signaling is indispensable for preimplantation development and is activated via a novel function of E-cadherin. PLoS Genet (2012) 8:e1002609. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002609

38. Playford MP, Bicknell D, Bodmer WF, Macaulay VM. Insulin-like growth factor 1 regulates the location, stability, and transcriptional activity of beta-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2000) 97:12103–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.210394297

39. Balzac F, Avolio M, Degani S, Kaverina I, Torti M, Silengo L, et al. E-cadherin endocytosis regulates the activity of Rap1: a traffic light GTPase at the crossroads between cadherin and integrin function. J Cell Sci (2005) 118:4765–83. doi:10.1242/jcs.02584

40. Guvakova MA, Lee WS, Furstenau DK, Prabakaran I, Li DC, Hung R, et al. The small GTPase Rap1 promotes cell movement rather than stabilizes adhesion in epithelial cells responding to insulin-like growth factor I. Biochem J (2014) 463:257–70. doi:10.1042/BJ20131638

41. Furstenau DK, Mitra N, Wan F, Lewis R, Feldman MD, Fraker DL, et al. Ras-related protein 1 and the insulin-like growth factor type I receptor are associated with risk of progression in patients diagnosed with carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2011) 129:361–72. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1227-y

42. Kim HJ, Litzenburger BC, Cui X, Delgado DA, Grabiner BC, Lin X, et al. Constitutively active type I insulin-like growth factor receptor causes transformation and xenograft growth of immortalized mammary epithelial cells and is accompanied by an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition mediated by NF-kappaB and snail. Mol Cell Biol (2007) 27:3165–75. doi:10.1128/MCB.01315-06

43. Graham TR, Zhau HE, Odero-Marah VA, Osunkoya AO, Kimbro KS, Tighiouart M, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I-dependent up-regulation of ZEB1 drives epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res (2008) 68:2479–88. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2559

44. Lorenzatti G, Huang W, Pal A, Cabanillas AM, Kleer CG. CCN6 (WISP3) decreases ZEB1-mediated EMT and invasion by attenuation of IGF-1 receptor signaling in breast cancer. J Cell Sci (2011) 124:1752–8. doi:10.1242/jcs.084194

45. Li H, Xu L, Zhao L, Ma Y, Zhu Z, Liu Y, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition via GSK-3beta and ZEB2 in the BGC-823 gastric cancer cell line. Oncol Lett (2015) 9:143–8.

46. Muranen T, Selfors LM, Worster DT, Iwanicki MP, Song L, Morales FC, et al. Inhibition of PI3K/mTOR leads to adaptive resistance in matrix-attached cancer cells. Cancer Cell (2012) 21:227–39. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.024

47. Sanabria-Figueroa E, Donnelly SM, Foy KC, Buss MC, Castellino RC, Paplomata E, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling increases the invasive potential of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing breast cancer cells via Src-focal adhesion kinase and forkhead box protein M1. Mol Pharmacol (2015) 87:150–61. doi:10.1124/mol.114.095380

48. Niepel M, Hafner M, Pace EA, Chung M, Chai DH, Zhou L, et al. Profiles of basal and stimulated receptor signaling networks predict drug response in breast cancer lines. Sci Signal (2013) 6:ra84. doi:10.1126/scisignal.2004379

49. Niepel M, Hafner M, Pace EA, Chung M, Chai DH, Zhou L, et al. Analysis of growth factor signaling in genetically diverse breast cancer lines. BMC Biol (2014) 12:20. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-12-20

50. Bendall SC, Stewart MH, Menendez P, George D, Vijayaragavan K, Werbowetski-Ogilvie T, et al. IGF and FGF cooperatively establish the regulatory stem cell niche of pluripotent human cells in vitro. Nature (2007) 448:1015–21. doi:10.1038/nature06027

51. Wu X, Zhou J, Rogers AM, Janne PA, Benedettini E, Loda M, et al. c-Met, epidermal growth factor receptor, and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor are important for growth in uveal melanoma and independently contribute to migration and metastatic potential. Melanoma Res (2012) 22:123–32. doi:10.1097/CMR.0b013e3283507ffd

52. Lindsey S, Langhans SA. Crosstalk of oncogenic signaling pathways during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Front Oncol (2014) 4:358. doi:10.3389/fonc.2014.00358

53. Zhang Z, Wang J, Ji D, Wang C, Liu R, Wu Z, et al. Functional genetic approach identifies Met, HER3, IGF1R, INSR pathways as determinants of lapatinib unresponsiveness in HER2-positive gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2014) 20:4559–73. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3396

54. Gao S, Bajrami I, Verrill C, Kigozi A, Ouaret D, Aleksic T, et al. Dsh homolog DVL3 mediates resistance to IGFIR inhibition by regulating IGF-RAS signaling. Cancer Res (2014) 74:5866–77. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0806

55. Gao C, Chen YG. Dishevelled: the hub of Wnt signaling. Cell Signal (2010) 22:717–27. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.11.021

56. Willert K, Nusse R. Wnt proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2012) 4:a007864. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a007864

57. Gujral TS, Chan M, Peshkin L, Sorger PK, Kirschner MW, Macbeath G. A noncanonical Frizzled2 pathway regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis. Cell (2014) 159:844–56. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.032

58. Rota LM, Albanito L, Shin ME, Goyeneche CL, Shushanov S, Gallagher EJ, et al. IGF1R inhibition in mammary epithelia promotes canonical Wnt signaling and Wnt1-driven tumors. Cancer Res (2014) 74:5668–79. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0970

59. Giles RH, Van Es JH, Clevers H. Caught up in a Wnt storm: Wnt signaling in cancer. Biochim Biophysica Acta (2003) 1653:1–24. doi:10.1016/S0304-419X(03)00005-2

60. Grumolato L, Liu G, Mong P, Mudbhary R, Biswas R, Arroyave R, et al. Canonical and noncanonical Wnts use a common mechanism to activate completely unrelated coreceptors. Genes Dev (2010) 24:2517–30. doi:10.1101/gad.1957710

61. Baldwin LA, Hoff JT, Lefringhouse J, Zhang M, Jia C, Liu Z, et al. CD151-alpha3beta1 integrin complexes suppress ovarian tumor growth by repressing slug-mediated EMT and canonical Wnt signaling. Oncotarget (2014) 5:12203–17.

62. Loughran G, Healy NC, Kiely PA, Huigsloot M, Kedersha NL, O’Connor R. Mystique is a new insulin-like growth factor-I-regulated PDZ-LIM domain protein that promotes cell attachment and migration and suppresses anchorage-independent growth. Mol Biol Cell (2005) 16:1811–22. doi:10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1052

63. Bowe RA, Cox OT, Ayllon V, Tresse E, Healy NC, Edmunds SJ, et al. PDLIM2 regulates transcription factor activity in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via the COP9 signalosome. Mol Biol Cell (2014) 25:184–95. doi:10.1091/mbc.E13-06-0306

64. Torrado M, Senatorov VV, Trivedi R, Fariss RN, Tomarev SI. Pdlim2, a Novel PDZ-LIM domain protein, interacts with {alpha}-actinins and filamin A. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2004) 45:3955–63. doi:10.1167/iovs.04-0721

65. Qu Z, Fu J, Yan P, Hu J, Cheng S-Y, Xiao G. Epigenetic Repression of PDZ-LIM domain-containing protein 2. J Biol Chem (2010) 285:11786–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.086561

66. Qu Z, Yan P, Fu J, Jiang J, Grusby MJ, Smithgall TE, et al. DNA methylation-dependent repression of PDZ-LIM domain-containing protein 2 in colon cancer and its role as a potential therapeutic target. Cancer Res (2010) 70:1766–72. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3263

67. Deevi RK, Cox OT, O’Connor R. Essential function for PDLIM2 in cell polarization in three-dimensional cultures by feedback regulation of the beta1-integrin-RhoA signaling axis. Neoplasia (2014) 16:422–31. doi:10.1016/j.neo.2014.04.006

68. Macartney-Coxson D, Hood K, Shi H-J, Ward T, Wiles A, O’Connor R, et al. Metastatic susceptibility locus, an 8p hot-spot for tumour progression disrupted in colorectal liver metastases: 13 candidate genes examined at the DNA, mRNA and protein level. BMC Cancer (2008) 8:187. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-8-187

69. Tanaka T, Soriano MA, Grusby MJ. SLIM is a nuclear ubiquitin E3 ligase that negatively regulates STAT signaling. Immunity (2005) 22:729–36. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.008

70. Tanaka T, Grusby M, Kaisho T. PDLIM2-mediated termination of transcription factor NF-kappaB activation by intranuclear sequestration and degradation of the p65 subunit. Nat Immunol (2007) 8:584–91. doi:10.1038/ni1464

71. Healy NC, O’Connor R. Sequestration of PDLIM2 in the cytoplasm of monocytic/macrophage cells is associated with adhesion and increased nuclear activity of NF-{kappa}B. J Leukoc Biol (2009) 85:481–90. doi:10.1189/jlb.0408238

72. Frasca F, Pandini G, Sciacca L, Pezzino V, Squatrito S, Belfiore A, et al. The role of insulin receptors and IGF-I receptors in cancer and other diseases. Arch Physiol Biochem (2008) 114:23–37. doi:10.1080/13813450801969715

73. Belfiore A, Malaguarnera R. Insulin receptor and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer (2011) 18:R125–47. doi:10.1530/ERC-11-0074

74. Malaguarnera R, Belfiore A. The emerging role of insulin and insulin-like growth factor signaling in cancer stem cells. Front Endocrinol (2014) 5:10. doi:10.3389/fendo.2014.00010

75. Morcavallo A, Gaspari M, Pandini G, Palummo A, Cuda G, Larsen MR, et al. Research resource: new and diverse substrates for the insulin receptor isoform A revealed by quantitative proteomics after stimulation with IGF-II or insulin. Mol Endocrinol (2011) 25:1456–68. doi:10.1210/me.2010-0484

76. Morcavallo A, Stefanello M, Iozzo RV, Belfiore A, Morrione A. Ligand-mediated endocytosis and trafficking of the insulin-like growth factor receptor I and insulin receptor modulate receptor function. Front Endocrinol (2014) 5:220. doi:10.3389/fendo.2014.00220

77. Blakesley VA, Koval AP, Stannard BS, Scrimgeour A, Leroith D. Replacement of tyrosine 1251 in the carboxyl terminus of the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor disrupts the actin cytoskeleton and inhibits proliferation and anchorage-independent growth. J Biol Chem (1998) 273:18411–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.29.18411

78. Kelly GM, Buckley DA, Kiely PA, Adams DR, O’Connor R. Serine phosphorylation of the insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-1) receptor C-terminal tail restrains kinase activity and cell growth. J Biol Chem (2012) 287:28180–94. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.385757

Keywords: IGF-1R, PDLIM2, adhesion, EMT, signaling, phenotype, resistance

Citation: Cox OT, O’Shea S, Tresse E, Bustamante-Garrido M, Kiran-Deevi R and O’Connor R (2015) IGF-1 receptor and adhesion signaling: an important axis in determining cancer cell phenotype and therapy resistance. Front. Endocrinol. 6:106. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00106

Received: 09 April 2015; Accepted: 19 June 2015;

Published: 03 July 2015

Edited by:

Krzysztof Reiss, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, USAReviewed by:

Andrea Morrione, Thomas Jefferson University, USACopyright: © 2015 Cox, O’Shea, Tresse, Bustamante-Garrido, Kiran-Deevi and O’Connor. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rosemary O’Connor, Cell Biology Laboratory, BioSciences Institute, School of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland,ci5vY29ubm9yQHVjYy5pZQ==

†Present address: Ravi Kiran-Deevi, Centre for Cancer Research and Cell Biology, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, UK

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.