95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Ecol. Evol. , 08 January 2024

Sec. Population, Community, and Ecosystem Dynamics

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1275953

This article is part of the Research Topic Evolutionary Ecology of Plant Defenses and Herbivore Interactions in the Tropics: From Molecules to Communities View all 5 articles

Capsicum (Solanaceae) includes peppers and chilies. Phytophthora capsici (Peronosporaceae) and Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) are two relevant problems in the production of this genus. Among the sustainable alternatives for disease and pest control, plant resistance and biological control stand out. The main objective of this research was to evaluate the resistance of Capsicum genotypes to damage by P. capsici and infestation by B. tabaci, as well as to diagnose whether the action of predators and parasitoids against B. tabaci could complement the resistance of the plants. The progression of disease caused by P. capsici and infestation by B. tabaci was estimated in 23 Capsicum genotypes, corresponding to the species: Capsicum annuum, Capsicum baccatum, Capsicum chinense, Capsicum frutescens and Capsicum. pubescens, from the GenBank of the National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIAP-Ecuador). Three genotypes: ECU-11993 (C. baccatum), ECU-11991 and ECU-2244 (C. pubescens) showed high susceptibility to both P. capsici damage and B. tabaci infestation. C. baccatum, C. chinense and C. frutescens genotypes showed the highest resistance to both pests, suggesting multiple resistance. Six taxa of predators and parasitoids reduced B. tabaci populations that developed in the most infested genotypes. Plant resistance is a control alternative that could allow the use of biological control, making it environmentally friendly. These results provide the basis for breeding programs in Capsicum.

The genus Capsicum (Solanaceae) is native to the Americas in a region that extends from Mexico to the south of the Andes and consequently Ecuador is part of the center of origin and domestication of species of this genus (Barboza et al., 2022). Capsicum spp. includes approximately 43 species of chilies and peppers, some of which are cultivated and represent economically important vegetables worldwide (Barboza et al., 2022). Capsicum annuum L., Capsicum baccatum L., Capsicum frutescens L., Capsicum pubescens Ruiz & Pav., Capsicum chinense Jacq. make up the five cultivated species among which C. annuum is the most economically important in the world (Barboza et al., 2022). Capsicum crops can be affected by pest and disease problems caused by various arthropods and pathogens. Diseases include root and crown rot and stem blight caused by Phytophthora capsici Leonian (Peronosporaceae) (Retes-Manjarrez et al., 2020; Vélez-Olmedo et al., 2020) and damage caused by the whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) (Singh and Joshi, 2020).

Phytophthora capsici is a highly destructive pathogen that causes leaf and stem blight, root and crown rot, and fruit rot (Retes-Manjarrez et al., 2020), which has caused severe epidemics in more than 50 plant species, mainly from the Solanaceae, Cucurbitaceae, and Fabeaceae families (Foster and Hausbeck, 2010; Quesada-Ocampo and Hausbeck, 2010; Lamour et al., 2012; Truong et al., 2012). Barchenger et al. (2018) reported that worldwide losses due to this pathogen are estimated at over $100 million annually. Bemisia tabaci causes direct damage through sap extraction and indirect damage through the growth of sooty mold produced by saprophytic fungi such as Capnodium spp. However, the most serious damage caused by B. tabaci is the transmission of viruses, especially the genera Begomovirus, Carlavirus, Crinivirus, Ipomovirus, and Torradovirus (Navas-Castillo et al., 2011). The direct and indirect damages caused by B. tabaci can lead to losses ranging from 20 to 100% of crop yield, amounting to millions of dollars (Sani et al., 2020).

The use of local genotypes of Capsicum is an alternative for the management of P. capsici and B. tabaci. Several candidate genes that could be involved in resistance to P. capsici have been identified, which interact in a complex way depending on the genotype and the Capsicum species (Rolling et al., 2020; Ro et al., 2022). However, few genotypes have been reported as sources of resistance in C. annuum (Criollo de Morelos-334 [CM334], PI 201232 and PI 201234 85 from Mexico; AC2258 from Central America, and Perennial from India) (Quirin et al., 2005); although more resistant genotypes might be found in other cultivated species of the genus. Likewise, physicochemical characteristics such as cuticle thickness, pubescence, trichomes (Ballina-Gomez et al., 2013), and secondary metabolites (Kariñho-Betancourt, 2018) are also mechanisms of resistance in plants against B. tabaci. Additionally, biological control exerted by predators and parasitoids has been successful in reducing the damage caused by B. tabaci in many countries (Kheirodin et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022).

Agroecosystems are a simplified version of natural ecosystems. They are an economic process involving living organisms such as plants and animals, developed and produced within a generally complex environmental setting. The ecological nature of the process makes it dependent on the trophic interactions of the producing organisms (plants) with their biotic and abiotic components. The abiotic components, such as climate and soil, condition the interaction of the biotic components, including insects, microbes, and other plants (Noman et al., 2020).

Tri-trophic interactions refer to the interconnections that link plants (first trophic level), herbivores or phytophagous (second trophic level), and carnivores such as predators, parasitoids, or entomopathogens (third trophic level) (Price et al., 2011). Herbivores rely on plants as primary producers to obtain vital resources for their development and reproduction, generating plant-herbivore interactions. Plants defend themselves from herbivores to survive, and through co-evolution, these interactions induce changes in herbivores for the same purposes (Burghardt and Schmitz, 2015). The second trophic level includes insects, other arthropods, as well as pathogens both aboveground and below ground (Van der Putten et al., 2001). Carnivores at the third trophic level obtain nutrients from herbivores, whose efficiency could influence cascading effects that reduce plant damage (Burghardt and Schmitz, 2015).

Utilizing trophic interactions and plant defense mechanisms against insects and pathogens, as well as the activity of parasitoids and predators, can be employed as alternatives for managing two significant issues caused by B. tabaci and P. capsici in genotypes of C. annuum, C. baccatum, C. frutescens, C. pubencens, and C. chinense. Therefore, the objective of this research was to assess the resistance of Ecuadorian genotypes of Capsicum spp. to damage caused by P. capsici and infestations by B. tabaci, as well as to estimate the impact of predators and parasitoids on B. tabaci populations.

This study was carried out at the Experimental Campus of the Faculty of Agricultural Engineering (FIAG) of the Technical University of Manabí (UTM), located in the Province of Manabí, Ecuador. The damage caused by P. capsici and B. tabaci was evaluated on 23 Capsicum genotypes (Table 1) from the gene bank of the National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIAP) (Santa Catalina Experimental Station, Quito-Ecuador); accessions were collected from different provinces of the three continental regions of Ecuador (Monteros et al., 2018).

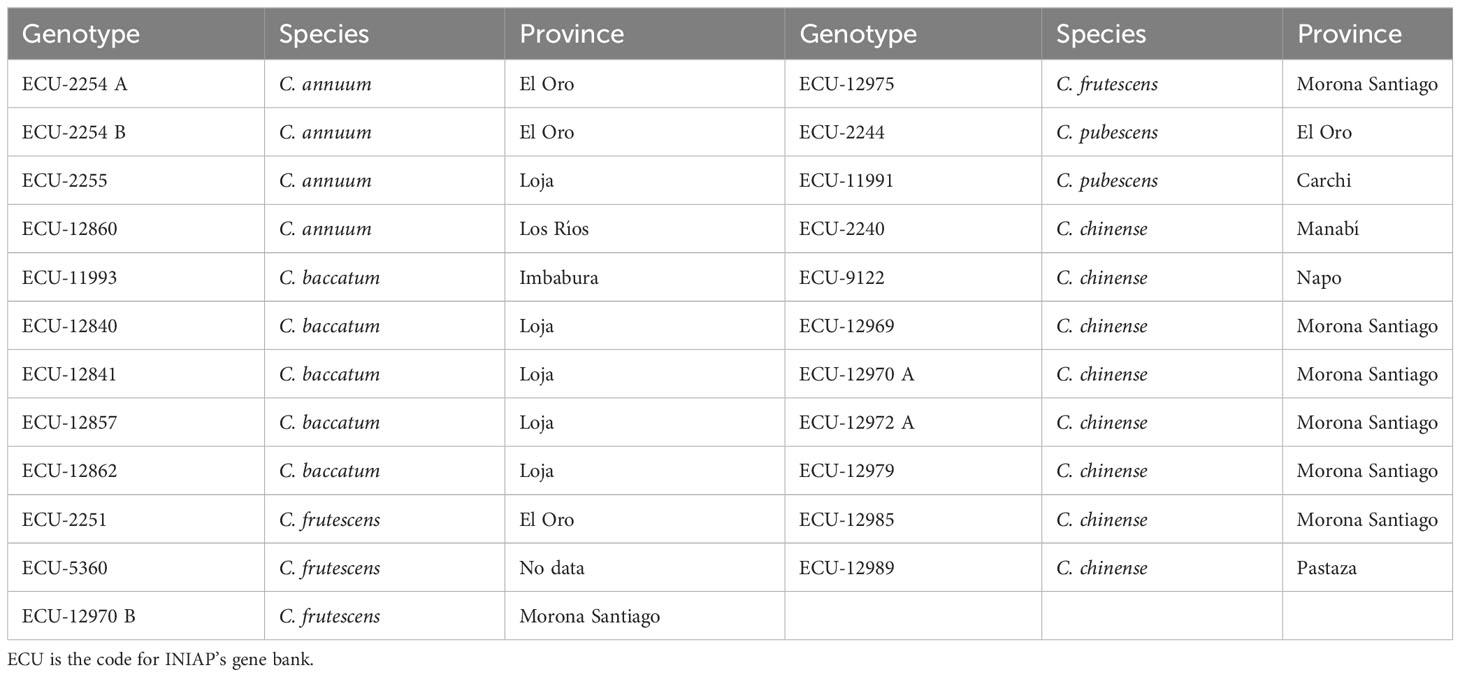

Table 1 Genotypes of the different Capsicum species evaluated in this study and the province of collecting.

Isolate Pc3 of P. capsici was used as inoculum for pathogenicity tests (Vélez-Olmedo et al., 2020). The pseudo-fungus was cultured in V8 agar culture medium (20%) at room temperature 24 ± 2 °C and under constant fluorescent light (Foster and Hausbeck, 2010). To obtain inoculum, the pathogen was sown in an Oat-Agar culture medium for the abundant production of mycelium (Saltos et al., 2020). When the colonies reached five days of age, 15 mm toothpicks were placed on top of the P. capsici colonies for colonization; 10-day-old cultures were used for inoculation.

Plants of the 23 genotypes of Capsicum spp. were planted in 50-well seedling trays, with a substrate previously sterilized (121°C and 1.5 atm) for two consecutive days and composed of a 1:1 ratio of sandy-loam soil and rice husks. During inoculation Capsicum spp. plants were decapitated following the procedures described by Pochard et al. (1976), and immediately, a wooden toothpick, colonized by the mycelium of the pathogen, was inserted into the apical meristem of the 45-day-old plants (V5 vegetative stage) (De La Torre et al., 2009). These plants were maintained under greenhouse conditions at 25±4°C and ~80% relative humidity. Plants were kept with field capacity humidity and fertilized weekly with a chemical mixture based on macronutrients (NPK 20-20-20, YaraTera Kristalon®) and foliar sprays of micronutrients (Evergreen®). The treatments comprised 23 Capsicum genotypes as aforementioned (Table 1). These were distributed in a completely randomized design with three replicates, where each replicate consisted of three plants.

The severity of the disease was quantified based on measurements of the length of stem necrosis with a ruler (Koc and Üstün, 2012). Symptoms were measured four days after inoculation (dai), and then every 48 h until 14 dai. To determine the cumulative advance of the symptom in the genotypes, the calculation of both the daily advance produced by P. capsici, as well as the time in which the maximum speed of advance the accumulated symptom were registered. Plants without of symptoms were classified as resistant, while plants that showed an accumulated lesion length between 1< and< 10 cm were categorized as moderately resistant, and plants with a lesion length > 10 cm were classified as susceptible.

Capsicum plants were transplanted into a greenhouse 30 days after sowing. Plants were placed at a distance of 1.30 m between rows and 0.70 m between plants. A randomized block design with four replicates was used, with five plants of each genotype planted per replicate. To accelerate the establishment of whitefly populations, pesticide sprays were applied at the beginning, following the methodology of Chirinos and Geraud-Pouey (1996). Fifteen days after plants were transplanted, profenofos (doses: 0.8 L.ha-1; 500 g active ingredient.L-1 (a.i.)) was applied and in the following two weeks, abamectin (doses: 0.75 L.ha-1, 18 g.L-1 a.i. (once a week). No more pesticide applications were done after. Sampling began one week later, taking four leaves per plant (two from the top layer and two from the middle layer) from two randomly selected plants per genotype for each replicate.

Leaf samples were collected in transparent plastic bags and taken to the Entomology Laboratory, FIAG-UTM and observed under a Carl-Zeiss® stereoscope (magnification: 10–40X), counting the number of eggs, first to third instar nymphs, and fourth instar nymphs of B. tabaci. Parasitized nymphs and predated nymphs of B. tabaci were also counted. The parasitized nymphs were identified by the larva or the pupa of the parasitoid that was observed through the integument. The predated ones were recognized because they were deflated or dry (without hemocoel content). Samplings were carried out at weekly intervals for 24 weeks. The percent (%) mortality in B. tabaci nymphs was calculated according to Equation 1.

(Equation 1)

Parasitized nymphs were placed individually in No 2 transparent gelatin capsules until the emergence of adults, which were mounted on slides using Hoyer's medium for subsequent identification to species with the keys of Polaszek and Evans (1992). The plates with the parasitoids were observed under an Olympus CX21® microscope at 4 - 100X magnification. Predatory coccinellids were identified to genus with the diagnostic characters outlined by Gonzalez (2015). Larvae of lacewings were identified to genus level by characteristics provided by Tauber et al. (2000).

Tests of normality (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homogeneity (Barllett's test) of variances were performed on the numerical data of the evaluated variables; when necessary, the data were transformed using √y obs + 0.5. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Scott-Knott clustering test (p < 0.05) was also used. A linear regression fit was performed to analyze the temporal progression of the disease and the cumulative progression of symptoms produced by P. capsici. For B. tabaci, the Friedman test was used to compare populations by genotype (p < 0.05). For genotypes where whitefly populations developed, a log regression analysis was performed between the percentage mortality and the number of nymphs (p < 0.05). A cluster analysis based on Euclidean distance was developed including the variables number of eggs, nymphs and severity of Phytophthora stem blight. Statistical analysis and preparation of graphs were performed in SAS version 9.4 (2018), Graphpad Prism software (version 8.0.2, San Diego, CA, USA) (2019), and the 'fact extra', 'ggplot2' and 'ExpDes.pt' packages available in R software version 4.3.0 (R Core Team, 2023).

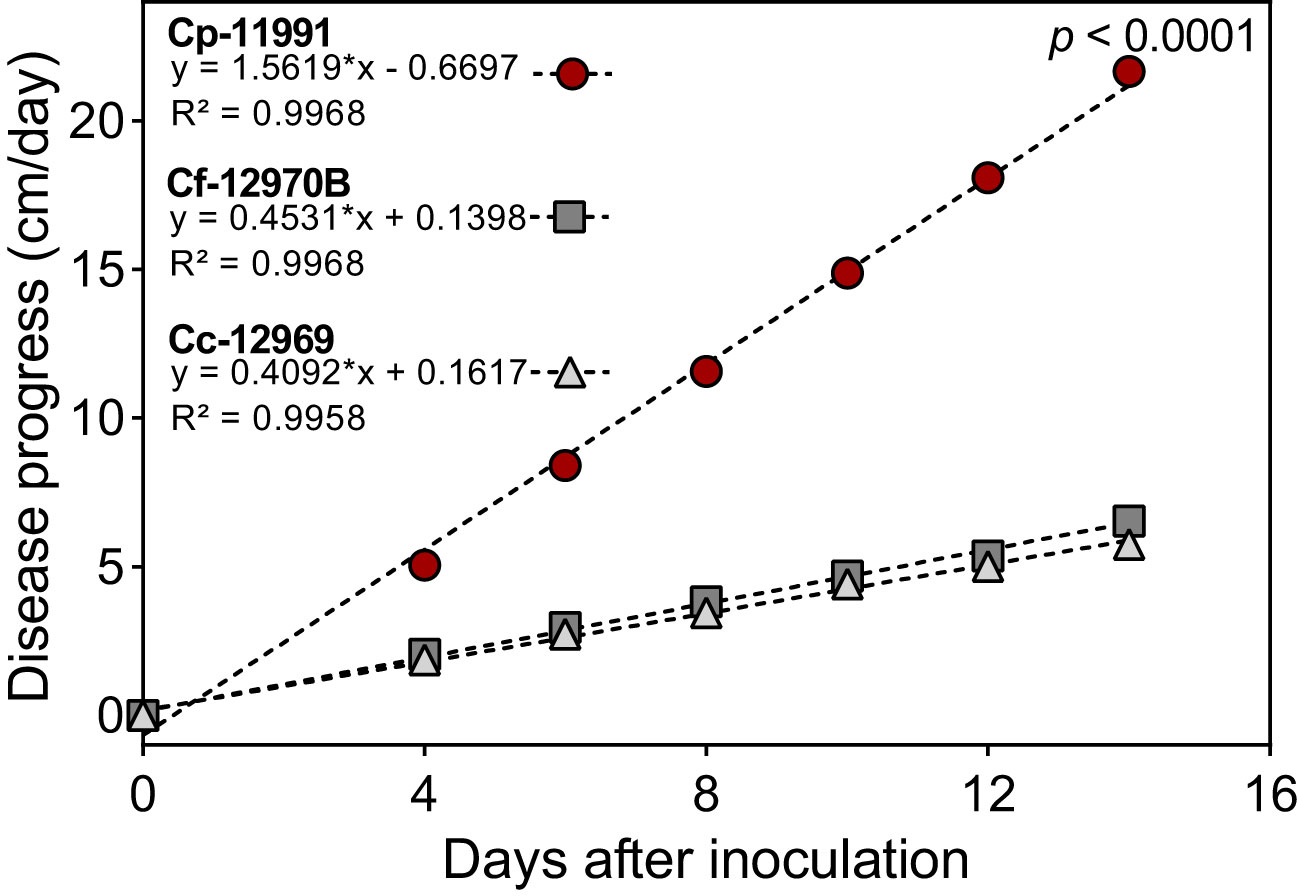

The speed of onset of Phytophthora stem blight symptoms caused by P. capsici varied among genotypes and Capsicum species. Genotypes such as ECU-11991 showed stem blight symptoms from the first day after inoculation (dai), with a daily progress of stem necrosis of 1.8 cm per day resulting in plants completely destroyed at 15 dai (Figure 1). Theses genotypes were classified as highly susceptible according to the methodology used. In genotypes such as ECU-12970B and ECU-12669, symptoms were observed from two dai, with a slow progression of stem necrosis of 0.41 and 0.47 cm per day, respectively (Figure 1). Theses genotypes were categorized as moderately resistant. The progression of Phytophthora stem rot showed a linear behavior with time, according to the regression fit.

Figure 1 Differences in the progress of Phytophthora stem blight caused by Phytophthora capsici between highly susceptible (Cp-11991) and moderately resistant genotypes (Cf-12970B y Cc-12969) of Capsicum spp. *Statistical significance for the regression model according to the F test (p < 0.0001). Cc, C. chinense Cf, C. frutescens and Cp, C. pubescens.

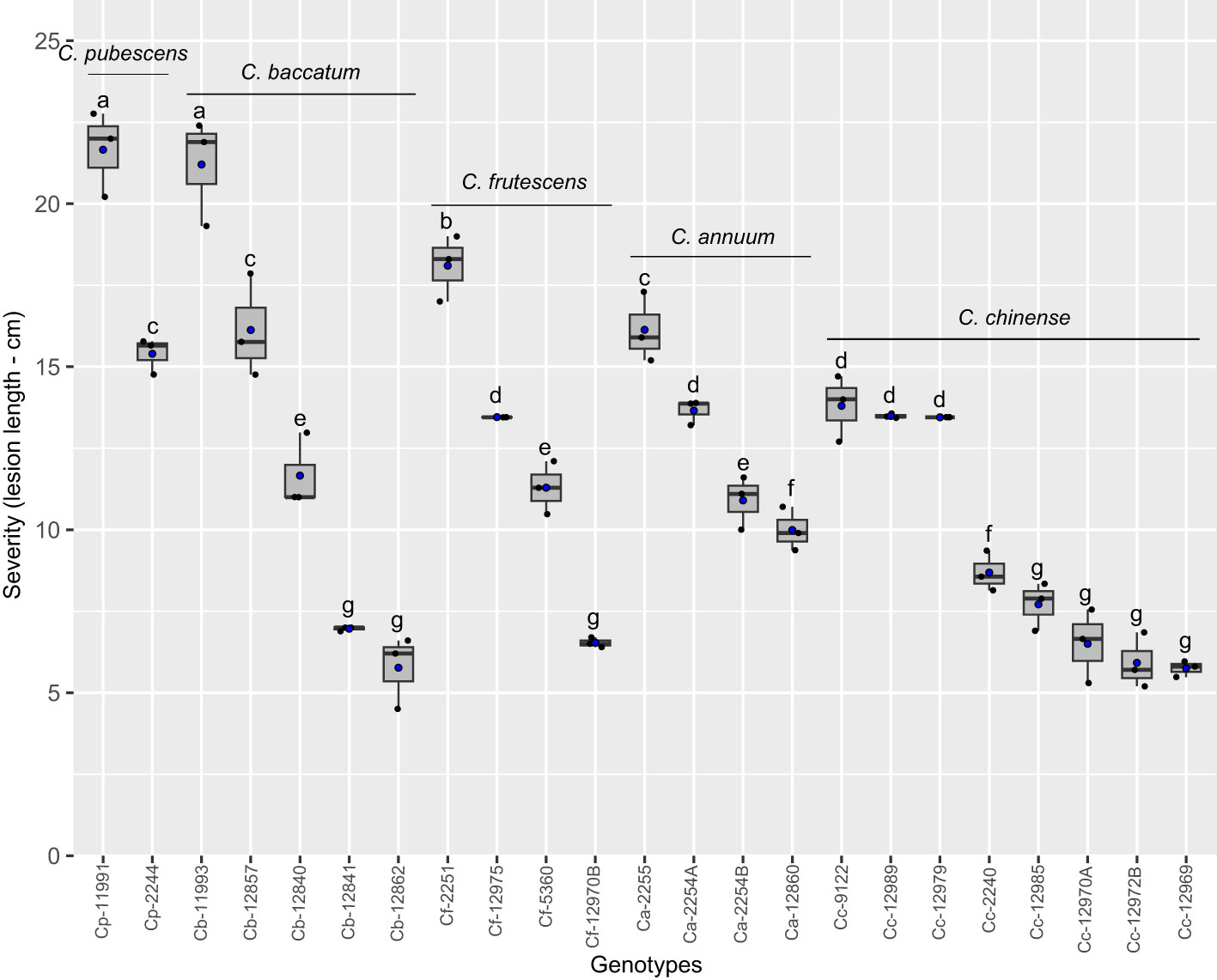

The final severity of Phytophthora stem blight caused by P. capsici was higher in genotypes ECU-11991 of C. pubescens, ECU-11993 of C. baccatum and ECU-2251 of C. frutescens, which exhibited stem necrosis length of 21.7, 21.2 and 18.1 cm, respectively (Figure 2). In ECU-2244, ECU-12857 and ECU-2255 genotypes of C. pubescens, C. baccatum and C. annuum, respectively, stem necrosis sizes exceeded 15 cm, these genotypes were classified as the second more susceptible group to infection by P. capsici. On the other hand, the genotypes with the lowest expression of symptoms were ECU-12841, ECU-12862 (C. baccatum), ECU-12985, ECU-12970A, ECU-12972B and ECU-12969 (C. chinense) and ECU-12970B (C. frutescens), whose average size of stem necrosis was 6.6 cm, being classified as moderately resistant (Figure 2). Overall, all genotypes developed symptoms of Phytophthora stem blight, suggesting no qualitative (vertical) resistance to the disease was present.

Figure 2 Phytophthora stem blight severity in Capsicum genotypes infected by Phytophthora capsici. Boxes with the same letters do not differ statistically from each other according to the Scott-Knott test (p < 0.05). Black and blue points represent the distribution and mean of the observations (n = 3), respectively. Ca, C. annuum. Cb, C. baccatum, Cc, C. chinense Cf, C. frutescens and Cp, C. pubescens.

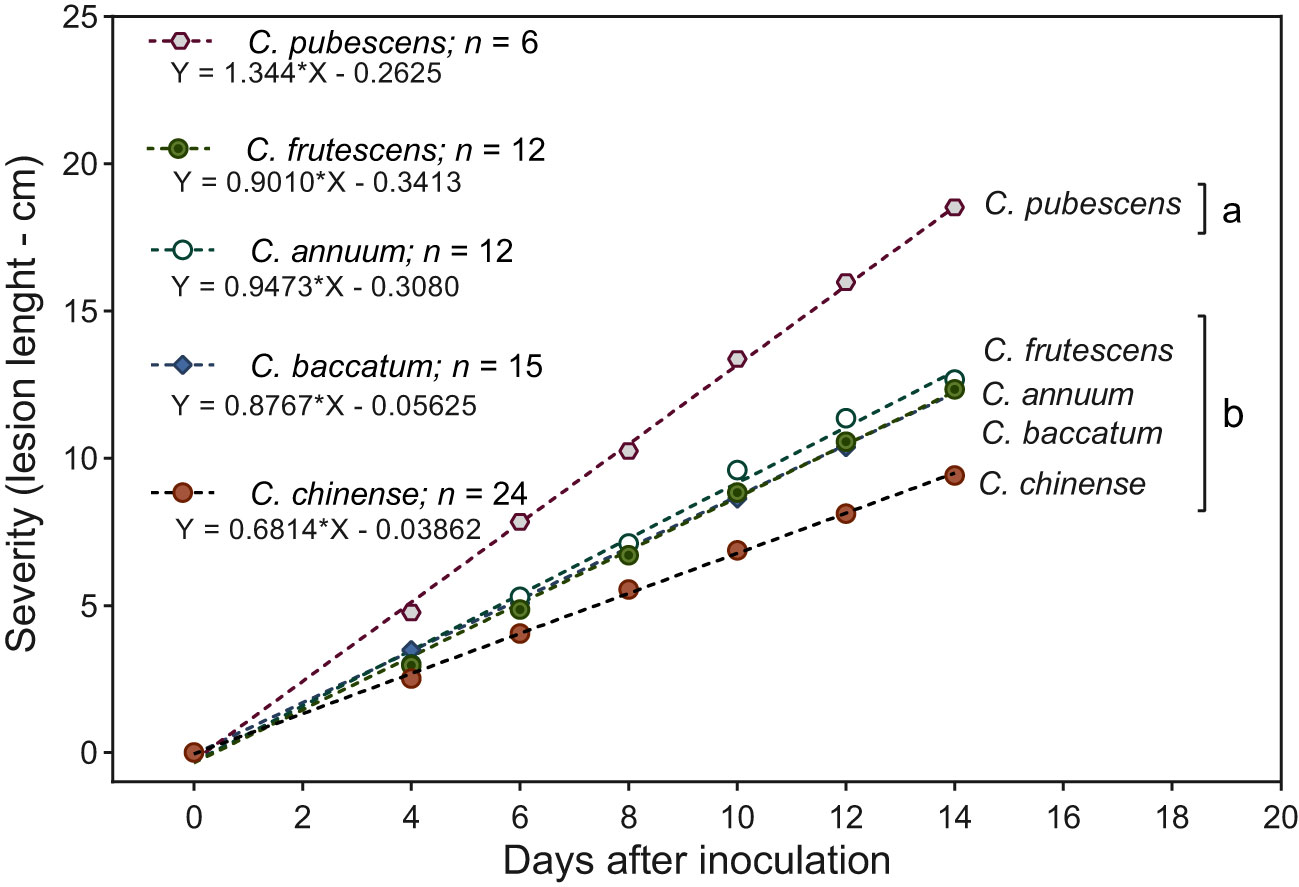

Species presented significant differences (p < 0.05) in response to infection of Phytophthora stem blight. The highest resistance responses were exhibited by C. annuum, C. baccatum, C. chinense and C. frutescens with mean stem lesion severity of 9.4, 12.3, 12.4 and 12.6 cm, respectively (Figure 3), while C. pubescens exhibited a higher degree of severity of the disease with 18.5 cm on average. The temporal progress of Phytophthora stem blight showed a linear growth through time in the five species evaluated, supported by the high statistical significance (p < 0.0001) of the regression fit.

Figure 3 Temporal severity of Phytophthora stem blight in five Capsicum species. Species grouped with different letters differ statistically by the Scott-Knott test (p < 0.05). * Statistical significance for the regression model according to the F test (p < 0.0001).

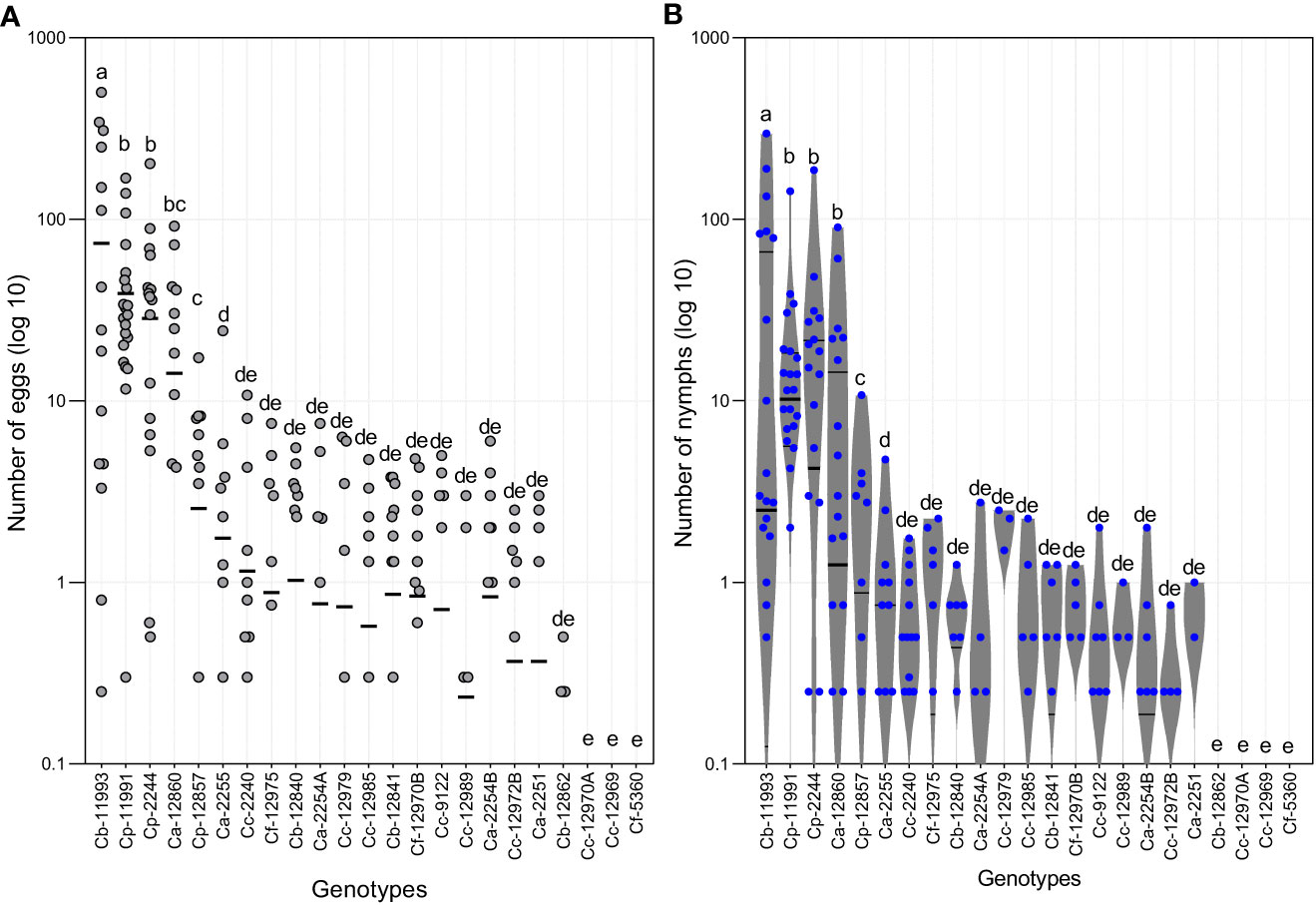

Eggs and nymphs of B. tabaci were abundant on four Capsicum genotypes (Figures 4, 5). The Friedman test showed that both, the number of eggs and nymphs of B. tabaci, were significantly higher in ECU-11993 (C. baccatum), with average values of 73 and 38 eggs and nymphs per leaf, respectively. Genotypes ECU-11991 and ECU-2244 (C. pubescens) were the second most infested, followed by ECU-12860 (C. annuum). Likewise, in three genotypes, two of C. chinense (ECU-12970A and ECU-12969), and one of C. frutescens (ECU-5360) no eggs were detected. Regarding the nymphs, in addition to these genotypes, this phase was not found in ECU-12862 of C. baccatum. The number of eggs on genotype ECU-11993 varied from 0 to 500, while in ECU-11991 and ECU-2244 the eggs fluctuated from 0 to 170 and 200, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4 (A) Numbers of eggs and (B) Number of nymphs of Bemisia tabaci on the genotypes of Capsicum spp. evaluated. Ca, Capsicum annuum; Cb, Capsicum baccatum; Cc, Capsicum chinense; Cf, Capsicum frutescens; Cp, Capsicum pubescens. The horizontal lines represent quartile 1, median and quartile 3. Means of equal letters do not differ significantly. Friedman test (p < 0.05).

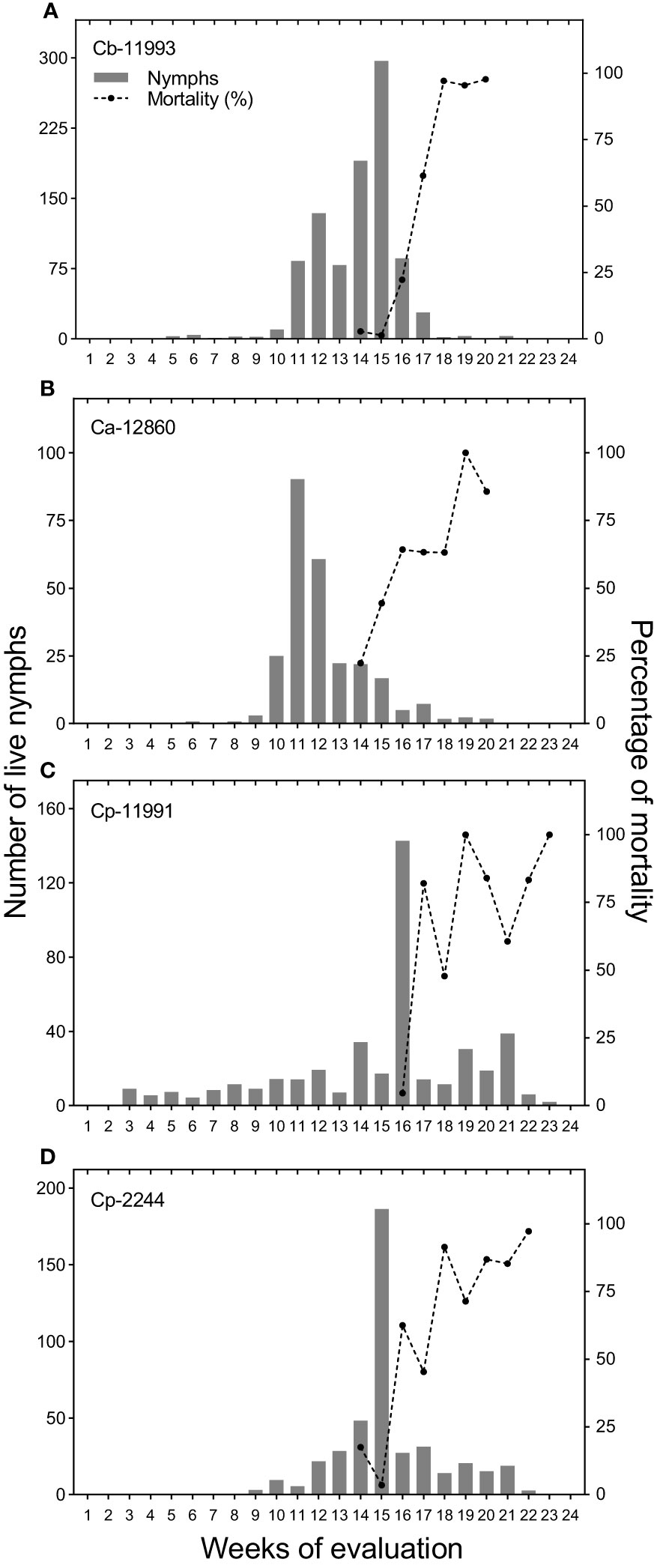

Figure 5 Population densities of Bemisia tabaci nymphs and percentage mortality of nymphs on the most infested Capsicum genotypes evaluated. (A) Capsicum baccatum (Cb-11993), (B) Capsicum annuum (Ca-12860), (C) Capsicum pubescens (Cp-11991) and (D) C. pubescens (Cp-2244).

Our results showed that four genotypes had high infestation rates and in the other 19 genotypes, low numbers of B. tabaci eggs and nymphs were detected. On ECU-12857 (C. pubescens) and ECU-2255 (C. annuum) eggs and nymphs did not exceed two individuals. In the remaining 17 genotypes, the average number of nymphs and eggs was even lower, reaching values ranging from 0 to 0.4 individuals.

The densities of B. tabaci nymphs together with the mortality percentage were plotted for the four most infested genotypes (Figure 5). Bemisia tabaci nymphs reached their highest number on the fifteenth week of evaluation for ECU-11993 and ECU-2244 genotypes with approximately 300 and 180 nymphs per leaf, respectively; while genotype ECU-11991 had the highest density on the sixteenth week, with 140 nymphs per leaf. The largest population of B. tabaci in ECU-12860 was observed on the eleventh week with 90 nymphs per leaf.

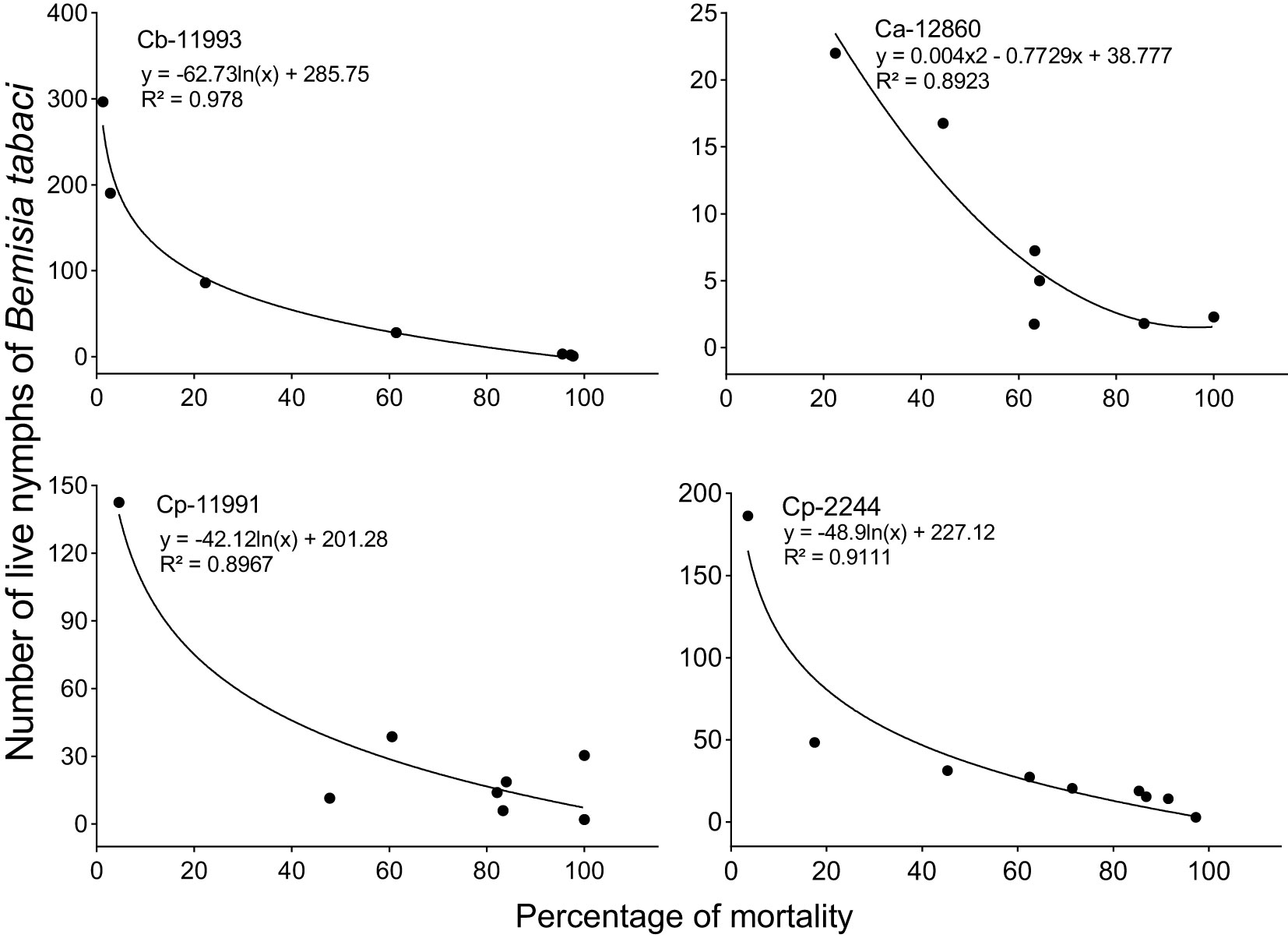

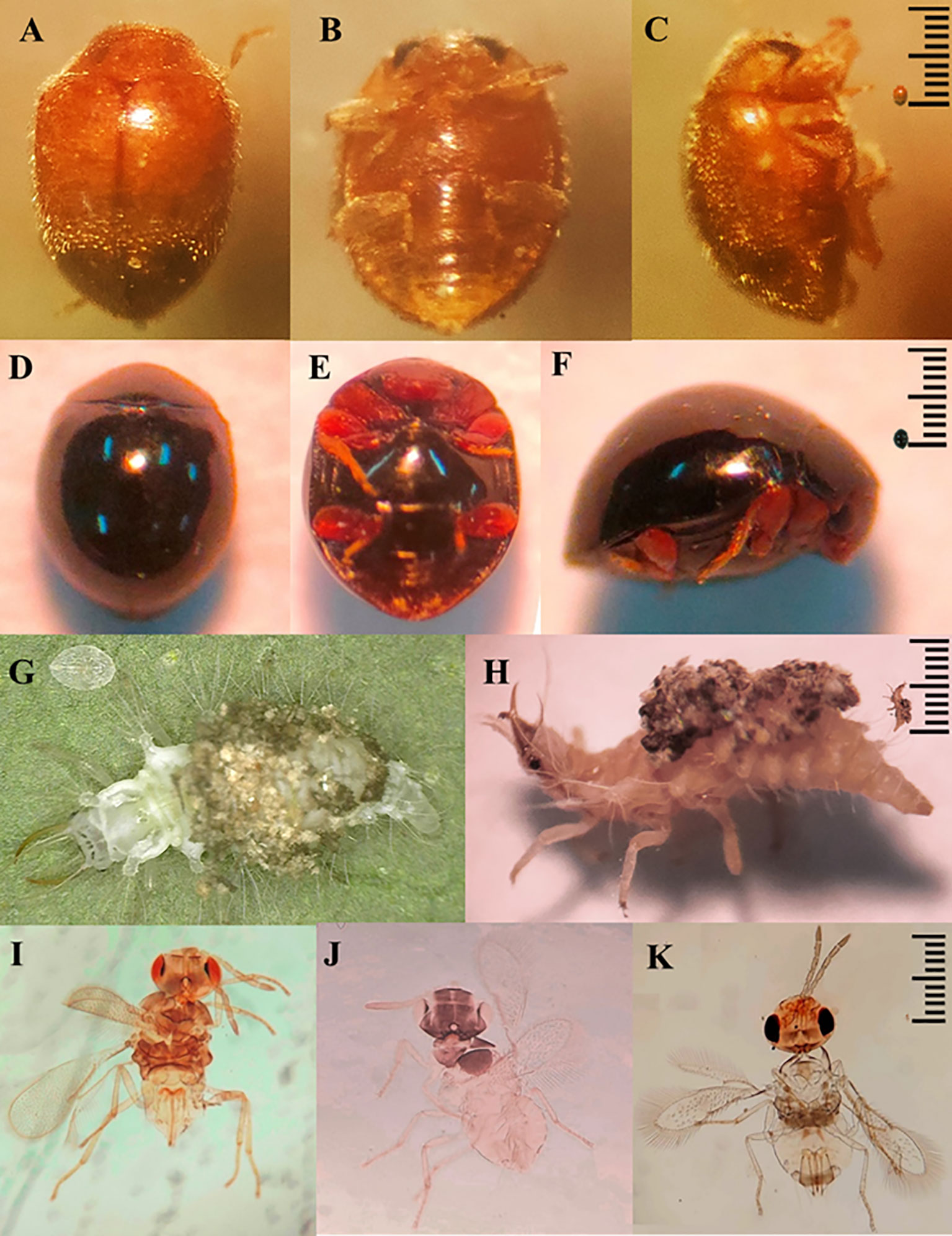

Between the fourteenth and sixteenth week of evaluation, predators and parasitoids became notorious which decimated the populations of B. tabaci with maximum mortality percentages varying from 85 to 100% depending on the genotype (Figure 5). Thus, the increase in the percentage of mortality was associated with the decrease in the densities of B. tabaci nymphs in the most infested genotypes. This was corroborated by the logarithmic regression equations calculated in which the decrease in the densities of B. tabaci nymphs was explained by an increase in the percentage of mortality with an R2 > 0.89 (Figure 6). Three taxa of predators and three species of parasitic wasps caused the death of B. tabaci (Figure 7). The predators were among the genera Nephaspis sp. and Delphastus sp. (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), and the genus Ceraeochrysa sp. (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae). Parasitoid species found attacking B. tabaci nymphs were Encarsia formosa Gahan, Encarsia nigricephala Dozier and Encarsia pergandiella Howard (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae).

Figure 6 Logarithmic regression equations between the percentage of mortality (X) and Bemisia tabaci nymphs (Y). Ca, Capsicum annuum; Cb, C. baccatum and Cp, C. pubescens.

Figure 7 Predators: Nephaspis sp. (A–C), Delphastus sp. (D–F), Ceraeochrysa sp. (G, H). Parasitoids: Encarsia formosa (I), Encarsia nigricephala (J) y Encarsia pergandiella (K).

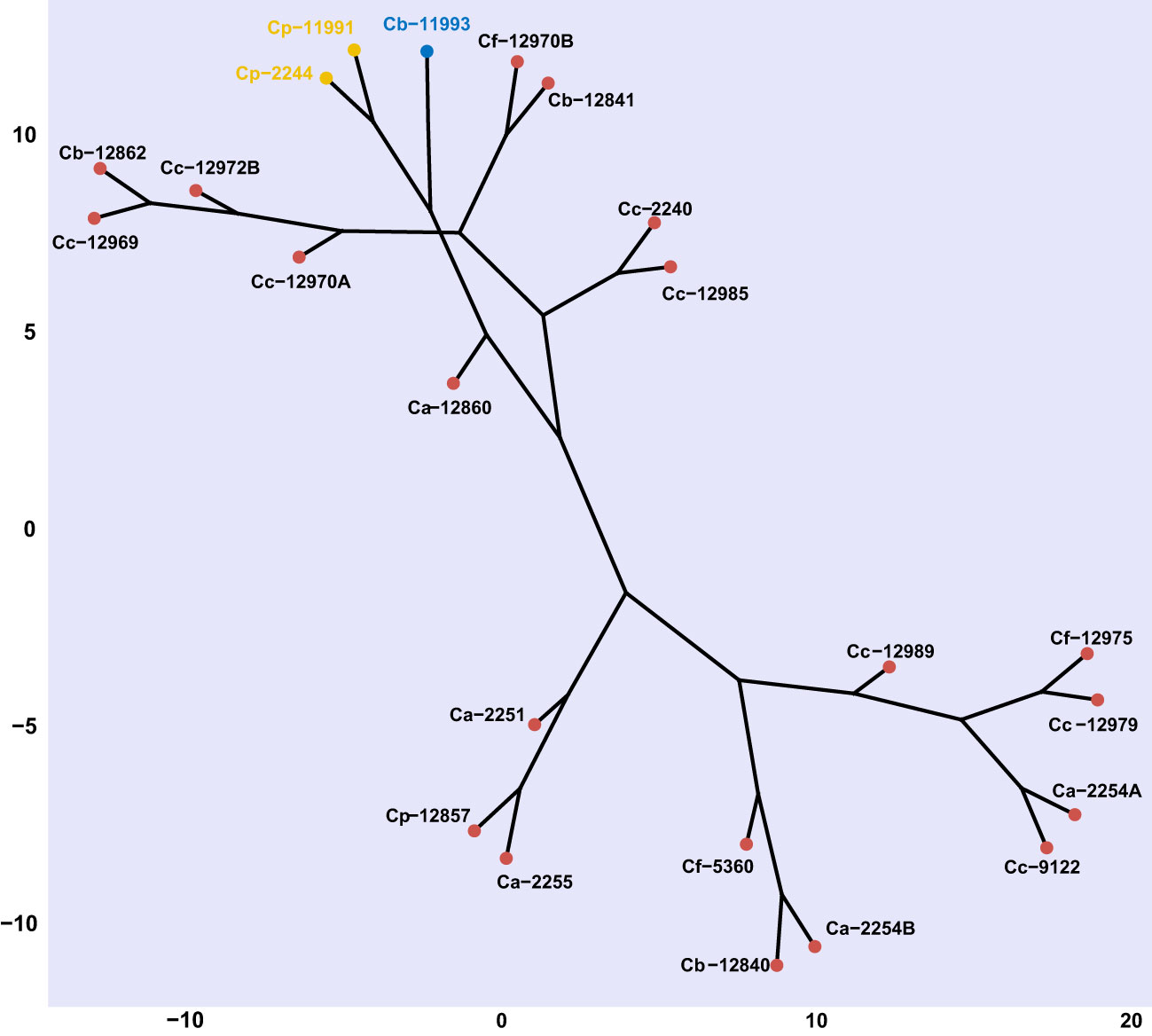

Capsicum genotypes were grouped into three distinctive clades based on the severity of Phytophthora stem blight and the level of infestations by B. tabaci using Euclidean distance with a cut-off point of 2.93 based on the Majena method. A first clade was made up of the ECU-11993 genotype, a second clade grouped C. pubescens genotypes ECU-11991 and ECU-2244, both groups showed high susceptibility to Phytophthora stem blight and B. tabaci. A third clade was comprised of the 20 remaining genotypes, which presented variable responses to infection by P. capsici and B. tabaci, however, they showed greater resistance in relation to the first two groups (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Cluster analysis (Euclidean method) based on phenotypic variables (number of eggs, number of nymphs and disease severity) of response against Bemisia tabaci and Phytophthora capsici in Capsicum genotypes. Ca, Capsicum annuum. Cb, C. baccatum, Cc, C. chinense Cf, C. frutescens and Cp, C. pubescens. Genotypes with the same font color belong to the same clade according to Majena's method grouping (k = 1.25).

Our findings showed that genotypes C. pubescens (ECU-11991 and ECU-2244) as well as C. annuum genotype (ECU-2255), C. baccatum (ECU-11993); and, C. frutescens (ECU-2251) showed high susceptibility to Phytophthora stem blight, with a faster progression of symptoms (stem necrosis). Regarding susceptibility at a species level, C. pubescens could be considered a susceptible, in relation to C. annuum, C. baccatum, C. chinense and C. frutescens, which could be classified as moderately resistant. There are reports in which genotypes moderately resistant to P. capsici show progression of stem necrosis length of around 1.95 cm at 3 days after inoculation (dai), while susceptible genotypes express nearly double the magnitude of P. capsici symptoms, with 3.5 cm lesions (Maillot et al., 2022). These results are similar to those found in our trial, where genotypes with high levels of resistance significantly delayed the progression of symptoms, to the point of stopping the infectious process. Barchenger et al. (2018) indicate that Capsicum plants with resistance to P. capsici quickly recognize and activate mechanisms related to defense in comparison with susceptible plants. Interactions between partially resistant Capsicum spp. plants with P. capsici adapted isolates showed little or no progress of the pathogen in infected tissue, possibly due to the activation of a detoxification system associated with the expression of phytoalexins in the plants (Maillot et al., 2022). Additionally, Zhang et al. (2013) reported that CaRGA2-like genes increased their expression during P. capsici infection. Therefore, resistant genotypes present higher levels of transcription of R genes in relation to the susceptible ones (Xia et al., 2013; Barraza et al., 2022).

Different varieties of Capsicum spp. have been identified as containing resistance genes against P. capsici (Candole et al., 2010). Until now, the best source of resistance against P. capsici has been found in the Morelos Creole genotype (CM-334) of C. annuum (Glosier et al., 2008; Ro et al., 2022). Other sources of resistance have been identified in varieties such as "PI 188476", "PI 201232", "PI 201234", "Chile Ancho San Luis", "Fyuco" and "Línea 29" (Kimble and Grogan, 1960; Walker and Bosland, 1999; Roig et al., 2009; Candole et al., 2010) and Dokyachunhchung (Glosier et al., 2008; Ro et al., 2022). However, despite the fact that CM-334 is an old source of resistance, it is the reference genotype in relation to its response capacity against various P. capsici isolates from different hosts and geographical regions (Oelke et al., 2003; Sarath et al., 2011; Sy et al., 2005). Genotype CM-334 presents at least two resistance genes against P. capsici, but this phenomenon has been associated with more genes (Walker and Bosland, 1999; Thabuis et al., 2003; Sy et al., 2005); however, Kim and Hur (1990) and Saini and Sharma (1978) indicate the presence of a single dominant gene. The moderate resistance of Capsicum spp. to P. capsici could be modulated by a multi-gene additive system (Lefebvre and Palloix, 1996). Our findings suggest the presence of potential sources of quantitative resistance, as genotypes such as ECU-12969, ECU-12972b, ECU-12970a, ECU-12985, and ECU-12970b showed mild symptoms but did not succumb to the infection caused by P. capsici. Therefore, this phenomenon could be associated with the combined action of various genes governing resistance in the aforementioned genotypes (Naegele and Hausbeck, 2020). In Ecuador, the presence of P. capsici has been reported as the causal agent of root and crown rot (Vélez-Olmedo et al., 2020) and the evaluation of resistance in commercial pepper cultivars to the pathogen (Saltos et al., 2020). However, the resistance of Capsicum germplasm with resistance to P. capsici has not been explored.

Ro et al. (2022) reported that accessions of C. chinense (PI 439449) and C. frutescens (PI82005) have exhibited moderate resistance to P. capsici, while accessions of C. baccatum did not show any type of resistance. Similarly, our results showed high levels of resistance in C. chinense genotypes, highlighting ECU-12969, ECU-12972B, ECU-12970A and ECU-12985 genotypes; and, C. frutescens ECU-12970B. In contrast with Ro et al. (2022), we also detected resistance against P. capsici in C. baccatum genotypes ECU-12941 and ECU-12862. These findings highlight the genetic diversity available in Capsicum and its potential for the development of varieties resistant to this pathogen.

For B. tabaci three instances were found depending on the population densities of B. tabaci in the genotypes. One in which at least one genotype of C. annuum, C. baccatum and C. pubescens reached high infestations, while the rest of the genotypes of these species showed incipient infestations indicating susceptibility and resistance within the same species. In the other, all the evaluated genotypes of C. chinense and C. frutescens exhibited little or no infestation, evidencing resistance against B. tabaci.

Evaluation of C. annuum genotypes in other regions has also shown differential resistance. For example, the Amaxito and Simojovel genotypes of C. annuum were tested against B. tabaci infestation among 15 native genotypes from Chiapas and Yucatán, Mexico, and both showed low oviposition and high nymphal mortality (Hernández-Alvarado et al., 2019). Chan et al. (2014) evaluated adult attraction and oviposition preference of B. tabaci to 14 local genotypes of C. annuum collected in Chiapas, Tabasco, and Yucatán. The Maax ik genotype from Yucatán was the least attractive for oviposition compared to Jalapeño, a commercial genotype susceptible to attack by this insect (Chan et al., 2014).

In Thailand, free-choice trials showed that the Keenu (C. frutescens) and Karang (C. chinense) cultivars were more attractive to B. tabaci adults for both feeding and oviposition (Sripontan et al., 2022), which contrasts with our results, since the genotypes of these species showed low or no infestation by B. tabaci. Firdaus et al. (2011) examined the resistance to B. tabaci infestations of 44 genotypes of C. annuum, C. baccatum, C. chinense and C. frutescens; the results showed one genotype of C. annuum, two of C. baccatum, five of C. chinense and one of C. frutescens were susceptible. Our results are similar for the first two species; however, they differ for the C. frutescens and C. chinense genotypes classified as susceptible, since resistance was detected in our study.

Differential levels of infra-species infestations by B. tabaci are probably related to the wide genetic variability within species. Genetic variability has been detected in Capsicum hybrids resulting in distinct morphological and molecular characteristics (Tripodi and Kumar, 2019; Barboza et al., 2022). In those genotypes that were hardly or not infested, resistance could be associated with antixenosis, which is a mechanism of plant resistance to deter colonization by an insect including morphological changes, such as variations in the plant surface, color changes, flavor, waxy or pubescent leaves, as well as gummy or resinous exudations (Kogan and Ortman, 1978). However, the antibiosis (mechanism of resistance) of the plant on the nymphs of B. tabaci is not ruled out.

The predator taxa detected in this study have been observed in Ecuador and other regions attacking whiteflies and other sucking insects. Nephaspis and Delphastus species have been reported preying on whiteflies in Ecuador (González, 2009). Gonzalez (2015) points out that an unspecified species of Nephaspis was found attacking whiteflies and hard scales on coconut, lemon and mango trees. Likewise, Delphastus species attacks whiteflies (Gonzalez, 2015). Ceraeochrysa sp. attacks leafhoppers and aphids in sugarcane, and the Asian psyllid in citrus (Cevallos et al., 2021). Kheirodin et al. (2020) report that Delphastus and Nephaspis species have shown effectiveness in regulating B. tabaci. Arno et al. (2010) point to a species of Ceraeochrysa as an effective predator of B. tabaci eggs and nymphs.

Regarding parasitoids, the identified species of Encarsia have been referred to as important biological control agents of B. tabaci in various crops. Yang et al. (2022) indicate that the genera Encarsia and Eretmocerus have been successfully used for biological control of B. tabaci in many countries. In Ecuador, E. formosa has been the subject of biological control programs for tomato whitefly (Castillo et al., 2020). Encarsia nigricephala and E. pergandiella have been reported to attack B. tabaci nymphs on melon and cotton (Zambrano et al., 2021; García-Vélez et al., 2023).

In several pepper-producing areas in Ecuador, at least two weekly organo-synthetic pesticide sprays have been carried out during a crop cycle to control pests, without taking into account the confidence intervals before harvest (Chirinos et al., 2020). In contrast, our results show the existence of biological control agents that have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing B. tabaci populations, one of the main pests of Capsicum. Given the existence of beneficial entomofauna that shows effectiveness in reducing insect pest populations, the implementation of conservation biological control programs is necessary. Chirinos et al. (2021) indicated that the two main strategies of conservation biological control consist of modifying the habitat to increase the survival, longevity, and reproduction of natural enemies, as well as reducing the exposure of these beneficial insects to pesticides.

Based on these results, 15 genotypes of Capsicum spp. showed susceptibility to P. capsici (Figure 2), while four genotypes developed high populations of B. tabaci (Figures 4, 5). Of these, three genotypes: ECU-11993 (C. baccatum); ECU-11991 and ECU-2244 (C. pubescens), exhibited susceptibility to both P. capsici infection and B. tabaci infestation. On the other hand, eight Capsicum genotypes showed resistance to both P. capsici and B. tabaci. The latter could be a mechanism of multiple resistance expressed in such genotypes.

Phytophthora capsici and B. tabaci are important phytosanitary problems in Solanaceae, causing devastating losses in pepper worldwide (Lamour et al., 2012; Li et al., 2021). Thus, the use of cultivars resistant to both biotic problems represent a less impactful measure for disease and pest management compared to the use of synthetic pesticides (Firdaus et al., 2012; Barchenger et al., 2018).

Multiple resistance to pests and diseases has been reported, although not frequently. In tomato, resistance to the root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne spp., aphids and whitefly has been found and attributed to the expression of the Mi-1.2 gene (Nombela et al., 2003). Similarly, multiple resistance against P. capsici and Verticillium dahliae Kleb. has been detected in the Grif 9073 genotype of C. annuum (Gurung et al., 2015). Multiple resistance mechanisms against various pests in Solanum pennellii Correll were associated with the presence of type IV glandular trichomes and secreted acyl sugars (Gentile and Stoner, 1968).

The use of resistant cultivars in integrated pest management programs, along with other control methods, favors the presence of natural enemies of both B. tabaci and P. capsici. The exploration of plant genetic resources to identify sources of resistance to diseases and pests is a critical task in the plant breeding process (Srivastava and Mangal, 2019). By identifying sources of resistance and understanding the mechanisms involved in plant responses to biotic factors, it is possible to develop varieties that are adapted to local conditions. Advances in the genetic improvement of this vegetable not only contribute to the development of more productive Capsicum varieties, but also provide long-term solutions for disease and pest management in sustainable production systems.

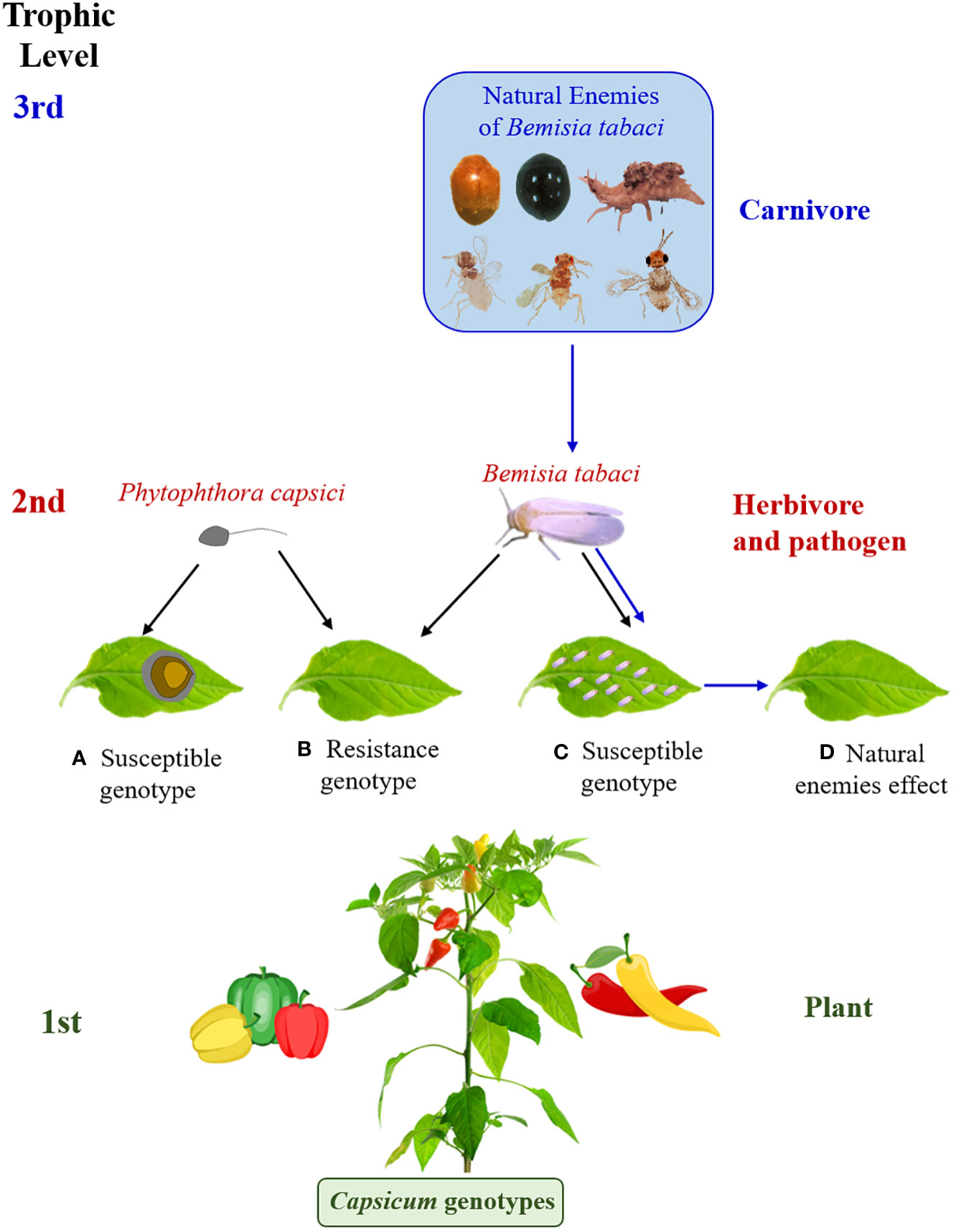

The base of the trophic chain is composed of "green" plants, which are organisms that synthesize organic matter from carbon dioxide, oxygen, water and solar energy, which becomes metabolically more complex with the participation of mineral nutrients found in the soil. Consumers (heterotrophic organisms) obtain vital nutrients from the plant that they cannot produce on their own. Consumer food chains constitute different trophic levels (phytophagous, carnivorous and saprophagous) (Price et al., 2011), which form structurally and functionally complex networks. Additionally, some individuals can be found sharing functions in more than one trophic level (Price et al., 2011; Centeno-Parrales et al., 2022). In this complexity lies the dynamic stability of biotic communities. Then, at the base of the trophic chain would be the genotypes of Capsicum spp., while B. tabaci and P. capsici constitute the second trophic level and the natural enemies of B. tabaci the third level (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Illustration of plant - herbivore, pathogen - carnivore interactions. (A–C) representation of the effect of Phytophthora capsici and Bemisia tabaci on resistant and susceptible genotypes of Capsicum spp., (D) effect of population reduction of B. tabaci by natural enemies. The photos are of our authorship and the pepper figures were acquired under license from Canva.

Within this context, plants have generated a diversity of mechanisms to defend themselves against herbivory, ranging from structural defenses such as spines or hard or difficult to chew tissues, to chemical defenses consisting of toxic compounds (Burghardt and Schmitz, 2015). It has been proposed by several researchers that plant-herbivore co-evolution has contributed significantly to the diversification of plant defense mechanisms that in turn generate evolutionary changes in herbivores (Luckmann and Metcalf, 1975; Johnson et al., 2015).

Three basic strategies frame plant resistance: deterrence (antixenosis), resistance (antibiosis) and tolerance (Kant et al., 2015). Antixenosis prevents colonization by the herbivore and involves constitutive characters, including morphological changes, such as subtle variations in plant surface, changes in color, taste, waxy or hairy leaves, as well as exudations of colored gums or resins (Kogan and Ortman, 1978). In antibiosis, the herbivore feeds on the plant, but the plant has adverse effects on the biology and can kill the herbivore or slow its development and reproduction (Painter, 1951; Shi et al., 2023). In tolerance, plant traits do not interact negatively with the herbivore, but compensate for damage caused by changes in assimilation rate, compensatory growth, phenological changes, resource allocation or morphological changes (Tiffin, 2000; Pérez-Hedo et al., 2015). Additionally, preformed structural characters constitute barriers that are referred to as constitutive defenses while induced defenses are triggered in response to herbivore attack (Kant et al., 2015).

As mentioned, we estimate that the resistance of the 19 Capsicum spp. genotypes that had low or no infestation by B. tabaci is related to antixenosis due to low oviposition and low abundance of nymphs found in these genetic materials, in which constitutive characters of the genotypes prevented the colonization of the insect. On the other hand, induced defenses could participate in the low damage of P. capsici on Capsicum spp. genotypes that resisted the progress of the disease caused by this pathogen.

Regarding the herbivore-carnivore interaction, in this study and despite the susceptibility of four Capsicum spp. genotypes to infestations by this insect, when carnivores (predators and parasitoids) attacked, B. tabaci populations were dramatically reduced in those susceptible Capsicum genotypes.

Burghardt and Schmitz (2015) indicated that, in the absence of predators, plant abundance is limited by herbivore consumption. However, predators can reduce herbivore abundance and consequently have an indirect effect on plants through cascading effects and can reduce plant damage, which is called trophic cascade (Burghardt and Schmitz, 2015). This could also be contributed by plant traits that attract natural enemies of herbivores, such as predators and parasitoids. Figure 9 is a representation of the effect of P. capsici and B. tabaci on resistant and susceptible genotypes of Capsicum spp. and the action of natural enemies on B. tabaci populations and its indirect effect on the plant.

Kant et al. (2015) reported that indirect plant defense consists of traits that enhance the attraction of natural enemies of the herbivore, such as predators and parasitoids, among which plant odor would be used by predators as an orientation to locate prey. Population reduction of B. tabaci by predators and parasitoids was corroborated in the four most infested genotypes. Thus, when efficient herbivory regulation by predators and parasitoids occurs, the increase in plant biomass "dilutes" the effects of consumption, mitigating the significance of damage.

In this research, the same genotypes that resisted B. tabaci infestations also resisted damage by P. capsici. This suggests multiple defense strategies of Capsicum spp. plants against an aerial herbivore and a soil-borne pathogens. Furthermore, the action of predators and parasitoids may contribute to the reduction of B. tabaci abundance.

Plant resistance is considered an alternative for managing these two phytosanitary problems. For B. tabaci, our results show that resistance and the existence of natural enemies could complement each other in the management of this pest. Starks et al. (1972) indicated that a marked resistance effect of the plant against a phytophagous insect is not essential, since moderate effects can be enhanced in combination with other factors such as natural enemies, such as the predators and parasitoids identified in this study.

Nineteen genotypes of Capsicum spp. showed resistance to Bemisia tabaci infestations while eight genotypes were moderately resistant to Phytophthora capsici. Consequently, eight genotypes exhibited resistance to both types of harmful organisms. This research constitutes unprecedented work in the detection of multiple resistance of Capsicum spp. genotypes to two of the main biotic problems that affect Capsicum species, such as Bemisia tabaci and P. capsici, which generate severe losses in crop yield in the main producing areas of the world. The introduction of promising genotypes in productive systems could substantially improve the management of these phytosanitary problems, making pepper and chili pepper cultivation a sustainable and economically viable activity for the farmer.

The finding of predators and parasitoids at the third trophic level that dramatically suppressed B. tabaci populations represents a fundamental aspect for implementing biological control programs.

Future studies should focus on determining the genetic factors involved in plant resistance, as well as estimating the functional and numerical responses of the main natural enemies of B. tabaci to establish further biological control programs.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical review and approval was not required for this study because the arthropods found in this research are associated with pepper crops, previously and widely reported in Ecuador so they were not collected in protected forests. Massive collections were not carried out, but rather they were observed on the sampled pepper leaves and consequently their presence was determined.

LC-Q: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration. DC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. LS-R: Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM-A: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was partially financed by the UTM. Permission for research to obtain resistant lines of Capsicum No. 008VZZ-DPAM-MAE.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Arno J., Gabarra R., Liu T.-X., Simmons A. M., Gerling D. (2010). “Natural enemies of Bemisia tabaci: predators and parasitoids,” in Bemisia: Bionomics and Management of a Global Pest. Eds. Stansly P. A., Naranjo S. E. (Dordrecht, Holland: Springer), 385–421. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-1524-0_11

Ballina-Gomez H., Ruiz-Sanchez E., Chan-Cupu,l W., Latournerie-Moreno L., Hernández-Alvarado L., Islas-Flores I., et al. (2013). Response of Bemisia tabaci Genn. (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) Biotype B to genotypes of pepper Capsicum annuum (Solanales: Solanaceae). Neotrop. Entomol. 42, 205–210. doi: 10.1007/s13744-012-0106-0

Barboza G. E., Garcí,a C. C., de Bem Bianchetti L., Romero M. V., Scaldaferro M. (2022). Monograph of wild and cultivated chili peppers (Capsicum L., Solanaceae). PhytoKeys 200, 1–423. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.200.71667

Barchenger D. W., Lamour K. H., Bosland P. W. (2018). Challenges and strategies for breeding resistance in Capsicum annuum to the multifarious pathogen, Phytophthora capsici. Front. Plant Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00628

Barraza A., Núñez-Pastrana R., Loera-Muro A., Castellanos T., Aguilar-Martínez C. J., Sánchez-Sotelo I. S., et al. (2022). Elicitor Induced JA-Signaling Genes Are Associated with Partial Tolerance to Hemibiotrophic Pathogen Phytophthora capsici in Capsicum chinense. Agronomy 12 (7):1637. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12071637

Burghardt K. T., Schmitz O. J. (2015). “Influence of plant defenses and nutrients on trophic control of ecosystems,” in Trophic ecology: Bottom-Up and Top-Down Interactions across Aquatic and Terrestrial Systems. Eds. Hanley T. C., La Pierre K. J. (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press), 203–232.

Candole B. L., Conner P. J., Ji P. (2010). Screening Capsicum annuum accessions for resistance to six isolates of Phytophthora capsici. HortScience 45 (2), 254–259. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.45.2.254

Castillo C. C., Gallegos P. G., Causton C. E. (2020). “Biological control in continental Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands,” in Biological Control in Latin America and the Caribbean: Its Rich History and Bright Future. Eds. van Lenteren J. C., Bueno V. H. P., Luna M. G., Colmenarez Y. C. (Wallingford, United Kingdom: CABI), 220–244. doi: 10.1079/9781789242430.0220

Centeno-Parrales J. A., Chirinos D. T., Kondo T. (2022). Trophic networks associated with the corn leaf aphid, Rhopalosiphum maidis (Fitch 1856) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in a cornfield, Manabí, Ecuador. Sci. agropecu. 13 (4), 327–333. doi: 10.17268/sci.agropecu.2022.029

Cevallos D., Santana, Cedeño J., Chirinos D. T. (2021). Predators and the management of some agricultural pests in Ecuador. Manglar 18 (1), 51–59. doi: 10.17268/manglar.2021.007

Chan W., Ruiz Sánchez E., Chan Díaz J. R., Latournerie Moreno L., Rosado Calderón A. T. (2014). Atracción de adultos y preferencia de oviposición de mosquita blanca (Bemisia tabaci) en genotipos de Capsicum annuum. Rev. Mexicana Cienc. Agric. 5 (1), 77–86. doi: 10.29312/remexca.v5i1.1011

Chirinos D. T., Anchundia M., Castro R., Castro J., Geraud J. E., Kondo T. (2021). Diversity of native and exotic parasitoids attacking agricultural pests in Ecuador: Are Ecuadorian biocontrol programs in decline. Anartia 33 (2), 7–26. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.5812416

Chirinos D. T., Castro R., Cun J., Castro J., Peñarrieta Bravo S., Solis L., et al. (2020). Insecticides and agricultural pest control: the magnitude of its use in crops in some provinces of Ecuador. Cienc. Tecnol. Agropecuaria 21 (1), 84–99. doi: 10.21930/rcta.vol21_num1_art:1276

Chirinos D. T., Geraud-Pouey F. (1996). Efectos de algunos insecticidas sobre entomofauna del cultivo del tomate, en el noroeste del estado Zulia, Venezuela. Interciencia 21 (1), 31–36.

De La Torre R., Cota F., García J., Campos J., San-Martín F. (2009). Etiología de la muerte descendente del mezquite (Prosopis laevigata L.) en la reserva de la biosfera del valle de Zapotitlán, México. Agrociencia 43 (2), 197–208.

Firdaus S., Heusden A., Harpenas A., Supena E. D. J., Visser R. G. F., Vosman B. (2011). Identification of silverleaf whitefly resistance in pepper. Plant Breed. 130, 708–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2011.01894.x

Firdaus S., van Heusden A. W., Hidayati N., Supena E. D. J., Visser R. G. F., Vosman B. (2012). Resistance to Bemisia tabaci in tomato wild relatives. Euphytica 187, 31–45. doi: 10.1007/s10681-012-0704-2

Foster J. M., Hausbeck M. K. (2010). Resistance of pepper to Phytophthora crown, root, and fruit rot is affected by isolate virulence. Plant Dis. 94 (1), 24–30. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-94-1-0024

García-Vélez C. J., Chirinos D. T., Centeno Parrales J., Cedeño L., Pin D. (2023). Effect of a synthetic insecticide and a botanical on pests , natural enemies and melon productivity. Rev. Fac. Agron. (LUZ) 40 (1), e234010.

Gentile A. G., Stoner A. K. (1968). Resistance in Lycopersicon and Solanum species to the potato aphid. J. Econ. Entomol. 61 (5), 1152–1154. doi: 10.1093/jee/61.5.1152

Glosier B. R., Ogundiwin E. A., Sidhu G. S., Sischo D. R., Prince J. P. (2008). A differential series of pepper (Capsicum annuum) lines delineates fourteen physiological races of Phytophthora capsici: Physiological races of P. capsici in pepper. Euphytica 162 (1), 23–30. doi: 10.1007/s10681-007-9532-1

Gonzalez G. (2015) Coccinellidae de Ecuador. Available at: https://www.coccinellidae.cl/paginasWebEcu/Paginas/InicioEcu.php.

González G. F. (2009). Nuevas especies de Nephaspis casey (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) de Perú, Ecuador y Brasil. Bol. Soc Entomol. Aragonesa 45, 101–108.

Gurung S., Short D. P. G., Hu X., Sandoya G. V., Hayes R. J., Subbarao K. V. (2015). Screening of wild and cultivated Capsicum germplasm reveals new sources of Verticillium wilt resistance. Plant Dis. 99 (10), 1404–1409. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-15-0113-RE

Hernández-Alvarado L. A., Ruiz-Sánchez E., Latournerie-Moreno L., Garruña-Hernández R., González-Mendoza D., Chan-Cupul W. (2019). Resistance of Capsicum annuum genotypes to Bemisia tabaci and influence of plant leaf traits. Rev. fitotec. mex. 42 (3), 251–257. doi: 10.35196/rfm.2019.3.251-257

Johnson M. T., Campbell S. A., Barrett S. C. (2015). Evolutionary interactions between plant reproduction and defense against herbivores. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 46, 191–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-112414-054215

Kant M. R., Jonckheere W., Knegt B., Lemos F., Liu J., Schimmel B. C., et al. (2015). Mechanisms and ecological consequences of plant defence induction and suppression in herbivore communities. Ann. Bot. 115 (7), 1015–1051. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcv054

Kariñho-Betancourt E. (2018). Plant-herbivore interactions and secondary metabolites of plants: Ecological and evolutionary perspectives. Bot. Sci. 96 (1), 35–51. doi: 10.17129/botsci.1860

Kheirodin A., Simmons A. M., Legaspi J. C., Grabarczyk E. E., Toews M. D., Roberts P. M., et al. (2020). Can generalist predators control Bemisia tabaci. Insects 11 (11), 1–22. doi: 10.3390/insects11110823

Kim B. S., Hur J. M. (1990). Inheritance of resistance to bacterial spot and to Phytophthora blight in peppers. Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 31 (4), 350–357.

Kimble K. A., Grogan R. G. (1960). Resistance to Phytophthora root rot in pepper. Plant Dis. 44, 872–873.

Koc E., Üstün A. S. (2012). Influence of Phytophthora capsici L. inoculation on disease severity, necrosis length, peroxidase and catalase activity, and phenolic content of resistant and susceptible pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plants. Turk. J. Biol. 36 (3), 357–371. doi: 10.3906/biy-1109-12

Kogan M., Ortman E. F. (1978). Antixenosis: a new term proposed to define Painter’s “nonpreference” modality of resistance. Bull. Entomol. Soc Am. 24 (2), 175–176. doi: 10.1093/%20besa/24.2.175

Lamour K. H., Stam R., Jupe J., Huitema E. (2012). The oomycete broad-host-range pathogen Phytophthora capsici. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13 (4), 329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00754.x

Lefebvre V., Palloix A. (1996). Both epistatic and additive effects of QTLs are involved in polygenic induced resistance to disease: A case study, the interaction pepper—Phytophthora capsici Leonian. Theor. Appl. Genet. 93, 503–511. doi: 10.1007/BF00417941

Li Y., Mbata G. N., Punnuri S., Simmons A. M., Shapiro-Ilan D. I. (2021). Bemisia tabaci on vegetables in the Southern United States: Incidence, impact, and management. Insects 12 (98), 1–29. doi: 10.3390/insects12030198

Luckmann W. H., Metcalf R. L. (1975). “The pestmanagement concept,” in Introduction to Insect Pest Management. Eds. Metcalf R. L., Luckmann W. H. (New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons), 1–60.

Maillot G., Szadkowski E., Massire A., Brunaud V., Rigaill G., Caromel B., et al. (2022). Strive or thrive: Trends in Phytophthora capsici gene expression in partially resistant pepper. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.980587

Monteros-Altamirano A., Tacán M., Peña G., Tapia C., Paredes N., Lima L. (2018)Guía para el manejo y conservación de recursos fitogenéticos en Ecuador in Protocolos P. miscelánea No. 432 Eds, INIAP-FAO. (Mejia, Ecuador: INIAP). Available at: http://repositorio.iniap.gob.ec/handle/41000/4889.

Naegele R. P., Hausbeck M. K. (2020). Phytophthora Root Rot Resistance and Its Correlation with Fruit Rot Resistance in Capsicum annuum. HortScience 55 (12), 1931–1937. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI15362-20

Navas-Castillo J., Fiallo-Olivé E., Sánchez-Campos S. (2011). Emerging virus diseases transmitted by whiteflies. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 49, 219–248. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095235

Noman A., Aqeel M., Qasim M., Haider I., Lou Y. (2020). Plant-insect-microbe interaction: A love triangle between enemies in ecosystem. Sci. Total. Environ. 699, 134181. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134181

Nombela G., Williamson V. M., Muñiz M. (2003). The root-knot nematode resistance gene Mi-1.2 of tomato is responsible for resistance against the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16 (7), 645–649. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.7.645

Oelke L. M., Bosland P. W., Steiner R. (2003). Differentiation of race specific resistance to Phytophthora root rot and foliar blight in Capsicum annuum. J. Am. Soc Hortic. Sci. 128 (2), 213–218. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.128.2.0213

Painter R. H. (1951). Insect Resistance In Crop Plants (New York, USA: Macmillan), 520 p. doi: 10.1097/00010694-195112000-00015

Pérez-Hedo M., Urbaneja-Bernat P., Jaques J. A., Flors V., Urbaneja A. (2015). Defensive Plant Responses Induced By Nesidiocoris Tenuis (Hemiptera: Miridae) On Tomato Plants. J. Of Pest Sci. 88, 543–554. doi: 10.1007/S10340-014-0640-0

Pochard E., Clerjeau M., Pitrat M. (1976). “La résistance du piment, Capsicum annuum L. à Phytophthora capsici Leon I. Mise en évidence d'une induction progressive de la résistance, Ann Amélior. Plantes 26 (1), 35-50.

Polaszek A., Evans G. A. (1992). and Bennett, F Encarsia parasitoids of Bemisia tabaci (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae, Homoptera: Aleyrodidae): A preliminary guide to identification. D.Bull. Entomol Res. 82 (3), 375–392. doi: 10.1017/S0007485300041171

Price P. W., Denno R. F., Eubanks M. D., Finke D. L., Kaplan I. (2011). Multitrophic interactions. Insect Ecol. (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press), 489–534. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511975387.019

Quesada-Ocampo L. M., Hausbeck M. K. (2010). Resistance in tomato and wild relatives to crown and root rot caused by Phytophthora capsici. Phytopathology 100 (6), 619–627. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-100-6-0619

Quirin E. A., Ogundiwin E. A., Prince J. P., Mazourek M., Briggs M. O., Chlanda T. S., et al. (2005). Development of sequence characterized amplified region (SCAR) primers for the detection of Phyto. 5.2, a major QTL for resistance to Phytophthora capsici Leon. in pepper. Theor. Appl. Genet. 110, 605–612. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1874-7

R Core Team (2023). “R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing,” in R Foundation for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation). Available at: https://www.R-project.org/.

Retes-Manjarrez J. E., Rubio-Aragón W. A., Márques-Zequera I., Cruz-Lachica I., García-Estrada R. S., Sy O. (2020). Novel sources of resistance to Phytophthora capsici on pepper (Capsicum sp.) landraces from mexico. Plant Pathol. J. 36 (6), 600–607. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.07.2020.0131

Ro N., Haile M., Hur O., Geum B., Rhee J., Hwang A., et al. (2022). Genome-Wide Association study of resistance to Phytophthora capsici in the pepper (Capsicum spp.) collection. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.902464

Roig J. M., Occhiuto P., Piccolo R. J., Galmarini C. R. (2009). Evaluación de resistencia a Phytophthora capsici Leo. en germoplasma argentino de pimiento para pimentón. Hortic. Argent. 28 (66), 5–9.

Rolling W., Lake R., Dorrance A. E., McHale L. K. (2020). Genome-wide association analyses of quantitative disease resistance in diverse sets of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] plant introductions. PloS One 15 (3), e0227710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227710

Saini S. S., Sharma P. P. (1978). Inheritance of resistance to fruit rot (Phytophthora capsici Leon.) and induction of resistance in bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Euphytica 27, 721–723. doi: 10.1007/BF00023707

Saltos L. A., Corozo-Quiñones L., Pacheco-Coello R., Santos-Ordóñez E., Monteros-Altamirano Á., Garcés-Fiallos F. R. (2020). Tissue specific colonization of Phytophthora capsici in Capsicum spp.: Molecular insights over plant-pathogen interaction. Phytoparasitica 49 (1), 113–122. doi: 10.1007/s12600-020-00864-x

Sani I., Ismail. S. I., Abdullah S., Jalinas J., Jamian S., Saad N. (2020). A review of the biology and control of whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), with special reference to biological control using entomopathogenic fungi. Insects 11 (9), 619. doi: 10.3390/insects11090619

Sarath B., Pandravada S. R., Rao R. P., Anitha K., Chakrabarty S. K., Varaprasad K. S. (2011). Global sources of pepper genetic resources against arthropods, nematodes and pathogens. Crop Prot. 30 (4), 389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2010.12.011

Shi H., Liu Y., Ding A., Wang W., Sun Y. (2023). Induced defense strategies of plants against Ralstonia solanacearum. Front. Microbiol. 14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1059799

Singh H., Joshi N. (2020). Management of the aphid, Myzus persicae (Sulzer) and the whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius), using biorational on Capsicum under protected cultivation in India. J. Biol. Pest Control 30, 67. doi: 10.1186/s41938-020-00266-5

Sripontan Y., Chiu C.-I., Charoensak K., Sukthongsa N. (2022). Host selection of the tobacco whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) among four pepper cultivars (Capsicum spp.), Thailand. Khon Kaen Agr. J. 50 (3), 899–909. doi: 10.14456/kaj.2022.77.900

Srivastava A., Mangal M. (2019). “Capsicum Breeding: History and Development,” in The Capsicum Genome. Eds. Ramchiary N., Kole C. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature), 25–55. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-97217-6_3

Starks K. J., Muniappan R., Eikenbary R. D. (1972). Interaction between plant resistance and parasitism against the greenbug on barley and sorghum. Ann. Entomol. Soc Am. 65 (3), 650–655. doi: 10.1093/aesa/65.3.650

Sy O., Bosland P. W., Steiner R. (2005). Inheritance of Phytophthora stem blight resistance as compared to phytophthora root rot and phytophthora foliar blight resistance in Capsicum annuum L. J. Am. Soc Hortic. Sci. 130 (1), 75–78. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.130.1.75

Tauber C. A., De León T., Penny N. D., Tauber M. J. (2000). The genus Ceraeochrysa (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) of America north of Mexico: larvae, adults, and comparative biology. Ann. Entomol. Soc Am. 93 (6), 1195–1221. doi: 10.1603/0013-8746(2000)093[1195:TGCNCO]2.0.CO;2

Thabuis A., Palloix A., Pflieger S., Daubèze A.-M., Caranta C., Lefebvre V. (2003). Comparative mapping of Phytophthora resistance loci in pepper germplasm: Evidence for conserved resistance loci across Solanaceae and for a large genetic diversity. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106, 1473–1485. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1206-3

Tiffin P. (2000). Mechanisms of tolerance to herbivore damage:what do we know? Evolutionary Ecol. 14, 523–536. doi: 10.1023/A:1010881317261

Tripodi P., Kumar S. (2019). “The Capsicum Crop: An Introduction,” in The Capsicum Genome, Compendium of Plant Genomes. Eds. Ramchiary N., Kole C.. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG), 1–8. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-97217-6_1

Truong N. V., Burgess L. W., Liew E. C. (2012). Cross-infectivity and genetic variation of Phytophthora capsici isolates from chilli and black pepper in Vietnam. Australas. Plant Pathol. 41, 439–447. doi: 10.1007/s13313-012-0136-4

Van der Putten W. H., Vet L. E., Harvey J. A., Wäckers F. L. (2001). Linking above-and belowground multitrophic interactions of plants, herbivores, pathogens, and their antagonists. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16 (10), 547–554. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02265-0

Vélez-Olmedo J. B., Saltos L., Corozo L., Bonfim B. S., Vélez-Zambrano S., Arteaga F., et al. (2020). First Report of Phytophthora capsici causing wilting and root and crown rot on Capsicum annuum (bell pepper) in Ecuador. Plant Dis. 104 (7), 2032-2032. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-11-19-2432-PDN

Walker S. J., Bosland P. W. (1999). Inheritance of Phytophthora root rot and foliar blight resistance in pepper. J. Am. Soc Hortic. Sci. 124 (1), 14–18. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-12-0242-R

Xia S., Cheng Y. T., Huang S., Win J., Soards A., Jinn T.-L., et al. (2013). Regulation of transcription of nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat-encoding genes SNC1 and RPP4 via H3K4 trimethylation. Plant Physiol. 162 (3), 1694–1705. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.214551

Yang S., Dou W., Li M., Wang Z., Chen G., Zhang X. (2022). Flowering agricultural landscapes enhance parasitoid biological control to Bemisia tabaci on tomato in south China. PloS One 17 (8), e0272314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272314

Zambrano N. D., Arteaga W., Velasquez J., Chirinos D. T. (2021). Side effects of Lambda Cyhalothrin and Thiamethoxam on insect pests and atural enemies associated with cotton. Sarhad J. Agric. 37 (4), 1098–1106. doi: 10.17582/journal.sja/2021/37.4.1098.1106

Keywords: antixenosis, resistance, predator, parasitoid, peppers, Phytophthora stem blight

Citation: Corozo-Quiñónez L, Chirinos DT, Saltos-Rezabala L and Monteros-Altamirano A (2024) Can Capsicum spp. genotypes resist simultaneous damage by both Phytophthora capsici and Bemisia tabaci? Can natural enemies of Bemisia complement plant resistance? Front. Ecol. Evol. 11:1275953. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2023.1275953

Received: 10 August 2023; Accepted: 01 December 2023;

Published: 08 January 2024.

Edited by:

Rafael E. Cárdenas, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, EcuadorReviewed by:

Maria Ordonez, University of California, Riverside, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Corozo-Quiñónez, Chirinos, Saltos-Rezabala and Monteros-Altamirano. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dorys T. Chirinos, ZG9yeXMuY2hpcmlub3NAdXRtLmVkdS5lYw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.