94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Ecol. Evol. , 21 December 2022

Sec. Population, Community, and Ecosystem Dynamics

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.953042

This article is part of the Research Topic Food Webs and Stable Isotopes, volume II View all 13 articles

Sulfur isotope (δ34S) analyses are an important archaeological and ecological tool for understanding human and animal migration and diet, but δ34S can be difficult to interpret, particularly in archaeological human-mobility studies, when measured isotope compositions are strongly 34S-depleted relative to regional baselines. Sulfides, which accumulate under anoxic conditions and have distinctively low δ34S, are potentially key for understanding this but are often overlooked in studies of vertebrate δ34S. We analyze an ecologically wide range of archaeological taxa to build an interpretive framework for understanding the impact of sulfide-influenced δ34S on vertebrate consumers. Results provide the first demonstration that δ34S of higher-level consumers can be heavily impacted by freshwater wetland resource use. This source of δ34S variation is significant because it is linked to a globally distributed habitat and occurs at the bottom of the δ34S spectrum, which, for archaeologists, is primarily used for assessing human mobility. Our findings have significant implications for rethinking traditional interpretive frameworks of human mobility and diet, and for exploring the historical ecology of past freshwater wetland ecosystems. Given the tremendous importance of wetlands’ ecosystem services today, such insights on the structure and human dynamics of past wetlands could be valuable for guiding restoration work.

Stable sulfur isotopes (δ34S) are used widely in archaeological and ecological research (Krouse, 1989; Canfield, 2001) and their importance continues to grow, particularly in the context of understanding patterns in past human and animal migration and diet (Nehlich, 2015). With recent improvements in instrumentation, allowing smaller sample sizes and more efficient simultaneous measurement of δ34S alongside other isotopic compositions (e.g., Sayle et al., 2019), generation of these data is likely to see even faster growth moving forward. However, it is still common, particularly in the archaeological literature, for interpretation of some published δ34S values to remain preliminary or tentative, especially when lower values do not appear to fit with regional expectations based on local faunal baseline isotopic compositions. In the early days of applying stable carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotope data to archaeological contexts, a very simple interpretive framework was employed: more or fewer C4 plants, lower or higher trophic position, and more or fewer marine resources (Schwarcz and Schoeninger, 1991). It is now apparent that a much wider range of biogeochemical processes can influence the δ13C and δ15N compositions throughout the biosphere, often in systematic ways, facilitating a wider interpretive context for archaeological and ecological plant, animal, and human remains. A similar widening of our isotopic interpretive framework for δ34S is currently underway.

In archaeological and ecological work, δ34S is typically used as a marker for mobility or diet (Nehlich, 2015; Hobson, 2019). Because δ34S compositions are not thought to undergo significant fractionation between diet and consumer (Peterson and Howarth, 1987; Fry, 1988; Krajcarz et al., 2019), they can be considered as an indicator for provenance. The premise for this is that the δ34S compositions of the bedrock and overlying geology and hydrology (Thode, 1991) are passed on to primary producers and up to higher-level consumers (Krouse, 1989; Canfield, 2001). This means that, across wider landscapes encompassing regions with varying underlying baseline δ34S, the origin of consumers can be assessed (Vika, 2009). In this context, region-specific differences between underlying geological baselines and baselines associated with adjacent riverine environments have also been used to assess the importance of freshwater resource use (Privat et al., 2007). A second major use of δ34S relies on the distinctive and homogenous isotopic composition of δ34S of seawater sulfates (+20‰; Rees et al., 1978), which can differ from the (often lower) δ34S characterizing baselines and food webs in adjacent terrestrial environments (Fry, 1988; Dance et al., 2018). This means that sulfate contributions from sea spray, with a marine δ34S composition, can have a large impact on the δ34S values of consumers in coastal areas (Zazzo et al., 2011), even masking local terrestrial sulfate contributions entirely (Guiry and Szpak, 2020). For this reason, consumer δ34S is sometimes used to assess residence in coastal areas (Richards et al., 2001). This distinction between δ34S in marine and non-marine ecosystems has also provided a basis for assessing the presence of marine contributions to diet, with consumers of marine foods at inland locations potentially also taking on higher δ34S values (e.g., Craig et al., 2006). A third interpretation of δ34S includes use as a marker for estuarine resources. It is sometimes suggested that marine consumers in estuarine areas could have lower δ34S due to the influence of freshwater sulfate contributions that may have a lower baseline δ34S (e.g., Nehlich et al., 2013). However, studies of consumers across modern estuarine gradients show that this will not always be the case (Fry and Chumchal, 2011) on the basis of simple mass balance, since it takes a very small amount of (sulfate-rich) seawater added to freshwater (typically an order of magnitude poorer in sulfate; Marschner, 2011) to mask a freshwater δ34S signal.

More recently, there has been a growing awareness among archaeologists (e.g., Szpak and Buckley, 2020; Rand et al., 2021; Guiry et al., 2021a; Lamb and Madgwick, 2022) of the potential for sulfides, which have a very low δ34S, to influence the isotopic composition of consumer tissues, a relationship that has been noted ecologically for decades in select marine-influenced environments (Carlson and Forrest, 1982; Fry et al., 1982). Following their earlier ecological counterparts (Peterson and Howarth, 1987; Mizota et al., 1999; Oakes and Connolly, 2004; Chasar et al., 2005), recent archaeological studies have shown, for instance, that in marine-influenced settings, such as saltmarshes (Guiry et al., 2021a), seagrass beds (Guiry et al., 2021c), and benthic microalgal-subsidized areas (Szpak and Buckley, 2020), coastal and marine archaeological consumers and their broader food webs can have δ34S values that are strongly impacted by sulfur with a sulfide-influenced δ34S value. Although this relationship between low δ34S and sulfide-rich environments is established in investigations of marine and coastal settings, it remains comparatively unexplored in higher-level consumers at inland-terrestrial and freshwater environments (though see Cornwell et al., 1995).

Here we explore the question of whether sulfur with sulfide-influenced δ34S could play an important role in determining the δ34S of terrestrial and aquatic consumers of resources from freshwater wetland areas. While recent work has shown that this is certainly the case for higher-level consumers (mammalian livestock) in at least some areas where primary production is dominated by coastal saltmarsh plants in the genus Spartina (Guiry et al., 2021a), it is possible that these and other plants in saltmarsh areas have an unusual tolerance for, or the ability to draw directly on, sulfur from otherwise highly toxic sulfides. Guiry et al. (2021a) suggest that this relationship showing 34S-depleted isotopic compositions in terrestrial consumers of coastal wetland environments may also provide a marker for the broader use of, or proximity to, freshwater wetlands, and call for more research to establish this relationship. For its part, while the ecological literature has explored variation in δ34S of coastal terrestrial plants in a variety of contexts (e.g., Stribling et al., 1998), little experimental work has been done in freshwater wetlands, although one early paper by Cornwell et al. (1995) does clearly suggest that lower δ34S could also be characteristic of primary producers in some freshwater wetland areas.

We investigate δ34S of an ecologically wide range of taxa to assess the extent to which δ34S co-varies with use of terrestrial (land-based), lacustrian (lake-based), and wetland (slower-moving marsh- and small water body–based) environments. Using archaeological animals from southern Ontario, Canada, with differing, known ecologies, that are further constrained and verified through analyses of δ13C and δ15N compositions, we build an interpretive framework for investigating the impact of wetland use on consumer δ34S. By exploring the impact of wetland resource use on the isotopic compositions of non-human vertebrates, we aim to provide a better understanding of implications for δ34S interpretations of both human and animal mobility and diet in contemporary, historical, and ancient contexts. Our data show that the use of resources from wetlands can have a very large impact on the δ34S of higher-level consumers across a food web and indicates that archaeological and ecological interpretations in areas of the world where freshwater wetlands are present should consider wetland resource use as a potential source of variation in δ34S when assessing mobility and diet. In showing that δ34S compositions can be driven by wetland-oriented dietary choices, and are therefore not always an accurate provenance tracer, this study has global implications for the way archaeological δ34S are interpreted. While this may be a source of interpretive uncertainty for some research questions, it opens new and potentially highly valuable avenues for others.

Sulfides can form under waterlogged, anoxic conditions as the metabolic end product of dissimulatory sulfate reducers, including both bacteria and archaea, which oxidize organic compounds using sulfate as an electron acceptor (Postgate, 1959). The redox and other conditions present in wetland sediment profiles, with slow water movement and limited oxygen, can lead to the accumulation of sulfides (Bagarinao, 1992; Marschner, 2011). These processes strongly discriminate against 34S, with fractionations of −40‰ to −45‰ observed in natural and culture experiments (Kaplan and Rittenberg, 1964; Kemp and Thode, 1968; Chambers et al., 1975; Habicht and Canfield, 1997). However, a large portion of these sulfides can be re-oxidized via a suite of chemical and biological pathways (Jørgensen, 1982), making isotopically light sulfate available to primary producers. Furthermore, stronger depletions (up to −70‰) observed in analyses of natural sediments suggest these microbially mediated processes can cycle sulfur in ways that create even more 34S-depleted isotopic compositions in waterlogged sediments (Canfield and Teske, 1996; Habicht and Canfield, 2001). While the processes responsible for driving the sulfur cycle in waterlogged sediments, and thus the fractionation of 34S, are clearly tremendously complex and still under investigation (Findlay and Kamyshny, 2017; Jørgensen et al., 2019), it is widely acknowledged that they often drive δ34S downwards.

It is also well documented that sulfides are both directly toxic to most plants (Lamers et al., 2013) and, by lowering soil redox potential, can lead indirectly to root oxygen deficiency stress (Koch et al., 1990). While some plants have demonstrated tolerance of sulfides (Carlson and Forrest, 1982; Fry et al., 1982), none are fully immune to higher concentrations (Koch and Mendelssohn, 1989). The means by which sulfur with sulfide-derived δ34S enters the food web remains unclear. It is possible, for instance, that plants growing in anoxic soil conditions have symbiotic relationships with sulfur-oxidising bacteria, or are themselves chemolithotrophic, allowing them to incorporate sulfide-derived sulfur and grow in areas with low soil sulfate concentrations (Morris et al., 1996). Alternatively, plants and other primary producers could incorporate sulfates that have been created from re-oxidized sulfides. In either case, aquatic and wetland primary producers would take on sulfide-influenced δ34S values.

We analyzed bone collagen, which, owing to its slower turnover, has isotopic compositions integrating a long-term, multi-year-averaged perspective on foods consumed (Hobson and Clark, 1992; Hyland et al., 2021) (although we note that turnover rates vary within and between bones and across biological ages). Species were selected to represent different ecological groups (i.e., predominantly terrestrial, lacustrian, or wetland inhabiting), with the aim of constructing an interpretive framework that includes taxa with both more constrained and more flexible habitat preferences. Mustelids, represented by American marten (Martes americana, n = 3), fisher (Martes pennanti, n = 2), and American mink (Neovison vison, n = 3), are terrestrial carnivores that prey largely on smaller animals (Baker and Hill, 2003). Previously published δ13C and δ15N values for these samples (Guiry et al., 2021b) allowed for selection of specimens with diets typical of terrestrial predators in the region. Our terrestrial baseline also includes samples from American red squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus, n = 3), Eastern gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis, n = 4), turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo, n = 2), and ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus, n = 3). Lake Ontario’s1 now-extinct population of Atlantic salmon [Salmo salar, n = 16; data from Guiry et al. (2016a)] was made up of large lacustrian piscivores with a narrowly constrained pelagic niche2 (Guiry, 2019; Guiry et al., 2020b). Both of these groups will have had diets that were minimally influenced by wetland-derived nutrients and therefore represent baselines for δ34S in the two main non-wetland biomes in the region—terrestrial (with δ34S influenced by local geology and hydrology) and lacustrian (with δ34S influenced mainly by upstream Great Lakes, but also by local watershed inputs), respectively. At the other end of the spectrum, American beavers (Castor canadensis, n = 14) and a variety of turtles (snapping, Chelydra serpentina, n = 2; painted, Chrysemys picta, n = 10; Blanding’s, Emydoidea blandingii, n = 3; map, Graptemys geographica, n = 1), which are primarily wetland denizens (Mac Culloch, 2002), will have had diets with a stronger influence from wetland δ34S.

Together, these groups with constrained habitat preferences provide anchor points for interpreting patterns along a continuum from wetland to non-wetland (i.e., terrestrial and lacustrian) ecosystems. Natural experiments such as this come with some inherent uncertainties and we acknowledge that individuals in our wetland baseline group could have diets and habitat preferences that are not as narrowly focused as the categories into which they have been placed. Beavers, for instance consume both aquatic and terrestrial (tree bark) plant foods (Baker and Hill, 2003), while turtles may also use lacustrian environments. Although we have selected terrestrial fauna based on previous isotope work (Guiry et al., 2021b), which allowed us to target individuals that had terrestrially oriented diets, we are also aware that some of these taxa, such as the fishers and American minks, are capable of foraging in aquatic or wetland habitats. However, for the present study we expect that, while variation in individual behavior may create more isotopic variation, emergent patterns will still provide a basis for establishing general directions of isotopic shifts associated with wetland-influenced diets.

Other taxa represent a range of more flexible ecologies and we hypothesise that they will show a wider spectrum of wetland to non-wetland δ34S. Muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus, n = 9) are capable wetland specialists, but are also well adapted for use of faster-moving lacustrian and riverine environments (Baker and Hill, 2003). We also include fish taxa with a large degree of behavioral and habitat-preference flexibility. American eels (Anguilla rostrata, n = 36), for instance, live for decades in Lake Ontario and its tributary watersheds before returning to the sea to reproduce and can specialize in both lacustrian and upstream wetland areas (COSEWIC, 2012). They are particularly well known for their ability to climb over obstacles and work their way inland to access habitats in slower-moving wetland areas (Allen, 2010; Jellyman and Arai, 2016). It is also worth pointing out that given that the vast majority of their growth (and life span) occurs after migration into freshwater, we do not expect a marine isotopic signal for the earliest phases of their catadromous life cycle to be retained in adult tissues (Guiry, 2019). Lastly, lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens, n = 21) are benthic feeders and while they do travel and forage up smaller tributaries (meaning they have potential to show some wetland-influenced δ34S values), based on the sampled specimens’ larger, adult size, we might expect the majority to show a closer affinity with the broader lacustrian δ34S baseline (COSEWIC, 2014).

While, ideally, we would also have a detailed contemporary isoscape for the study region to further refine our interpretations, differences observed between species with similar ecologies in the archaeological past and their modern counterparts (Colborne et al., 2016; Guiry et al., 2016a) suggest that there may have been a δ34S baseline shift due to modern atmospheric sulfur contributions (Zhao et al., 2003). While further work would be needed to resolve this, for the present study we believe that together, these baseline- (ecologically constrained terrestrial, lacustrian and wetland endpoints) and hypotheses-driven (ecologically flexible) sample selections create a strong interpretive framework for assessing the impact of wetlands resource use on consumer δ34S.

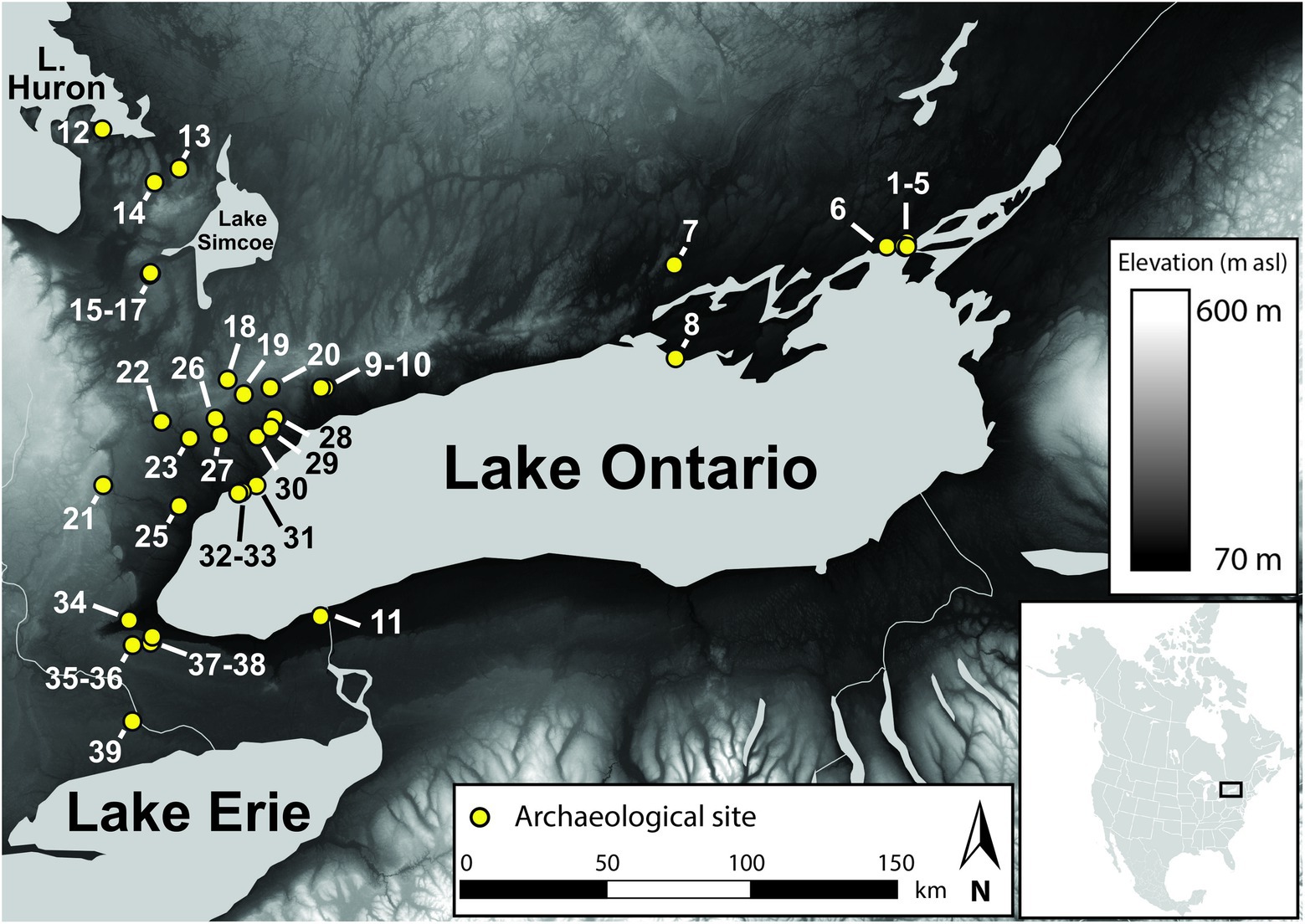

Samples (n = 132) come from 39 sites in southern Ontario, Canada (Figure 1 and Table 1), and date to between 500 CE and 1900 CE, although the vast majority (83%) date to between 1250 and 1650 CE (Supplementary Table S1). Bone samples were selected based on minimum number of individual estimates per archaeological context in order to minimise the possibility of sampling the same individual more than once. Bone collagen extractions followed well established methods (Longin, 1971). Samples were cut into small chunks, demineralized in 0.5 M hydrochloric acid (HCl), and then rinsed to neutrality in Type 1 water. For fish, prior to demineralization, samples were soaked in a bath of 2: 1 chloroform methanol to remove potential residual lipids (Guiry et al., 2016b). Following demineralization, samples were soaked in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide in an ultrasonic bath (solution refreshed every 15 min until solution remained clear) to remove base soluble contaminants. Samples were then neutralized in Type 1 water and refluxed in 10−3 HCl (pH 3) at 70°C for 36 h. Samples were centrifuged and the solubilized fraction was transferred into a fresh tube, frozen, and lyophilized.

Figure 1. Map showing sites and study region. Numbers correspond to site contextual details listed in Supplementary Tables S1; S6.

Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope and elemental compositions were measured on 0.5 mg subsamples of collagen using a Vario MICRO cube elemental analyzer (EA) coupled to an Isoprime isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS; Elementar, Hanover, Germany) or an EA 300 (Eurovector, Pavia, Italy) coupled to a Horizon IRMS (Nu Instruments, Wrexham, United Kingdom). Stable sulfur isotope and elemental compositions were measured separately on 8.0 mg (for mammals and reptiles) or 6.0 mg (for fish) subsamples of collagen along with a combustion enhancer (10 mg of V2O5) using an ANCA EA coupled to a Europa SL/20–20 IRMS (Europa, Crewe, United Kingdom). Replicate analyses were performed on ca. 30 and 10% of samples for δ13C/δ15N and δ34S, respectively. Isotopic compositions were calibrated relative to VPDB and AIR for δ13C and δ15N and to VCDT for δ34S (Supplementary Table S2). We monitored precision and accuracy with internal collagen standards (Supplementary Table S2). Long-term observed averages (check standards) or known (calibration standards) values for all reference materials are reported in Supplementary Table S3. Averages and standard deviations for calibration standards (Supplementary Table S4), check standards (Supplementary Table S5), and sample replicates (Supplementary Table S6) for all analytical sessions are also available in the Supplementary material. For δ13C, δ15N, and δ34S, systematic errors [μ (bias)] were ± 0.11‰, ±0.12‰, and ± 0.23‰, respectively; random errors [μR(w)] were ± 0.12‰, ±0.14‰, and ± 0.12‰, respectively; and standard uncertainty was ±0.16‰, ±0.19‰, and ± 0.26‰, respectively (Szpak et al., 2017). Collagen quality control (QC) was assessed using conservative C: N (Guiry and Szpak, 2021), %C (>13%), and %N (>4.8%) criteria (Ambrose, 1990). Statistical comparisons were performed in PAST version 3.22 (Hammer et al., 2001). Pearson’s r tests were used to test the significance of correlations between δ13C and δ34S.

All samples passed collagen QC criteria. Stable sulfur isotope compositions show a very large range spanning 17.0‰ (−5.0 to +12.0‰; Figures 2A,B; data summarized in Table 1, full results in Supplementary Table S6). Data from baseline species map closely onto our ecological expectations based on their terrestrial, lacustrian, or wetland habitat preferences. There is a slight difference between our terrestrial (mustelids, squirrels, and ground-dwelling birds; n = 20, mean δ34S = +6.9 ± 1.8‰, range = +3.6 to +11.8‰) and lacustrian (Atlantic salmon; n = 17, mean δ34S = +8.8 ± 1.6‰, range = +5.8 to +11.4‰) taxa, suggesting that δ34S baselines from these environments, while potentially variable, may rely on isotopically different sources.

Limited geological and hydrological isotopic baseline data are available for the study region (some examples exist from adjacent regions to the north; e.g., Hesslein et al., 1988). The isotopic variability in our data could, for instance, reflect broad-scale differences in the geologies (OGS, 1991; Henry et al., 2008) that underlie local terrestrial and aquatic vs. upstream aquatic habitats. The uppermost geology across much of the study region is composed of marine-derived sedimentary bedrock of various ages and compositions, which typically has relatively high δ34S values (Bottrell and Newton, 2006). In contrast, the deeper bedrock underlying this, which becomes exposed immediately to the north of the study region and is an important bedrock system for some of the upstream Great Lakes (Huron and Superior), is the Canadian Shield. The Canadian Shield is a large region of Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rock, a rock type that, although variable, typically has δ34S values that are lower than those found in marine environments (for review see, Thode, 1991). This latter source is, however, unlikely to be a major contributor of sulfate to biota due to the low sulfur content of silicious igneous rocks, which often means that ecosystems in these regions rely mainly on atmospheric deposition for their sulfur budget (for review see, Mitchell et al., 1998). Nonetheless, in this context, to the extent that the sulfur budget of lacustrian habitats of Lake Ontario might be subsidized by sulfate contributions from upstream watersheds, we might expect to find higher δ34S values in terrestrial fauna living atop bedrock composed of ancient marine sediments compared with lacustrian counterparts, for which baselines could reflect greater contributions from older, non-marine geologies and/or atmosphere-dominated sources. Although the average difference we see between our terrestrial and lacustrian groups is small (<2.0‰), we observe the opposite pattern. We note, however that this basic interpretive scenario (marine vs. non-marine origins of uppermost bedrock) is highly simplified and that surface geology may be influenced by a wide range of other factors, such as the presence of glacially re-deposited, non-marine sediments and local variation in the presence of other bedrock types. It is also possible that Lake Ontario’s lacustrian and terrestrial sulfur isotope baselines are simply dominated by sulfate sources endemic to the watershed (i.e., a combination of glacial re-deposition, marine-derived bedrock, atmospheric deposition, and smaller contributions from other local bedrock types). Regardless of what geological or hydrological processes are responsible for the differences we observed between our lacustrian and terrestrial fauna, we consider them to be valid, if approximate, baselines for establishing a backdrop against which to compare and contrast wetland-derived δ34S variation. We also note that, although sample sizes are too small (averaging 3.3 samples per each of our 39 sites) to assess covariance between site location and δ34S values for our terrestrial and lacustrian baseline groups, we see no obvious patterns between geographical locations and isotopic variation across the study region (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S6).

In comparison to these terrestrial and lacustrian baselines, our wetland taxa (beavers n = 14, mean δ34S = +0.5 ± 4.1‰, range = −5.0 to +8.3‰; turtles; n = 16, mean δ34S = +4.4 ± 2.4‰, range = +0.1 to +10.1‰) both indicate a lower baseline δ34S for wetland denizens. Variation among turtles includes individuals with δ34S that overlap with the lacustrian and terrestrial baseline taxa, suggesting that some may have lived in larger water bodies and/or made use of terrestrial resources. Beavers show the lowest values, with the widest range (spanning 13.1‰). This matches closely with their diet range which includes both roots from wetland plants [these structures have been observed to have δ34S values that are more sulfide-influenced than plant tissues that are not in contact with sediments; Frederiksen et al., 2006)] and bark from trees in adjacent terrestrial habitat. This supports the use of these groups as δ34S baselines for assessing the influence of wetland (i.e., sulfide-cycled) sulfur on the δ34S of more behaviorally flexible taxa.

In that context, the wide spectrum of δ34S values from eels (n = 36, mean δ34S = +8.5 ± 3.8‰) which spans 17‰ and matches well with their known ecology, including both high (+12.0‰) and low (−1.0‰) δ34S values that closely follow our wetland and lacustrian baselines. Muskrats also show a wide, but on average lower, range of δ34S values (n = 9, mean δ34S = +3.6 ± 3.7‰, range = −0.8 to +9.5‰) consistent with their flexible ecology feeding along a lacustrian–wetland spectrum. In contrast, but as expected, the bulk of lake sturgeon samples produced δ34S values falling at the lacustrian end of the spectrum (n = 21, mean δ34S = +9.3 ± 2.0‰, range = +3.2 to +11.3‰), with only one individual producing a value significantly lower than our lacustrian baseline, suggesting significant use of wetland-influenced areas.

Considering δ15N helps to further contextualize the ecology of these taxa. Each species’ δ15N (Figures 2B,C) is broadly consistent with its respective trophic position (DeNiro and Epstein, 1981), with more herbivorous aquatic (beavers, n = 14, +4.1 ± 1.3‰; muskrats n = 9, +4.7 ± 2.5‰) and terrestrial (squirrels n = 6, +7.0 ± 1.8‰; ground birds n = 5 + 5.9 ± 0.5‰) animals having lower values than apex predators (Atlantic salmon, n = 16, +10.8 ± 1.2‰; mustelids n = 8, +9.0 ± 1.0‰) in their respective habitat types. Atlantic salmon and one eel with higher δ15N (> 12‰) provide an exception to this observation, but these samples come from historical contexts after 1850 CE, postdating a large-scale, early nineteenth-century isotopic shift in Lake Ontario’s nitrogen cycle that followed major forestry activities in the watershed (Guiry et al., 2020a). Consistency among the δ34S values of these historical Atlantic salmon with higher δ15N and earlier salmon with lower δ15N suggests that Lake Ontario’s broader sulfur cycle did not undergo a similar isotopic shift at this time. These individuals aside, the overall consistency between δ15N and expected trophic positions across our dataset suggests that, with respect to nitrogen cycling and sources, these samples are from a well-integrated wider biome with a consistent δ15N baseline.

Stable carbon isotope compositions (Table 1 and Figures 2A,C) show patterns that complement and reinforce our interpretations of those observed in δ34S. Freshwater ecosystems such as Lake Ontario can have extremely variable δ13C (Schelske and Hodell, 1991; Hodell and Schelske, 1998), owing to complex and multifaceted processes that govern the cycling, sourcing, and partitioning of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) pools across varied intra- and inter-annual temporal scales and physical and biological conditions (Guiry, 2019). In this context, variation at the higher end of our observed δ13C spectrum, which characterizes samples from lacustrian taxa such as Atlantic salmon (n = 16, −19.9 ± 0.3‰) and lake sturgeon (n = 21, −18.4 ± 2.3‰), are consistent with their expected foraging behavior in more pelagic and littoral areas, respectively (France, 1995; Guiry, 2019). In contrast, the extremely low δ13C and high degree of variation among turtles (n = 16, −24.8 ± 2.3‰) suggests a wetland DIC budget more heavily influenced by CO2 sourced from the breakdown of allochthonous terrestrial detritus [typically 13C-depleted relative to atmospheric sources used by their terrestrial and, to some extent, lacustrian counterparts (Finlay and Kendall, 2007)]. Together these data show that, for this study region, while lacustrian food webs have higher δ13C values, wetlands have distinctively low δ13C, as might be expected in contexts where water movement is slow and CO2 released from breakdown of allochthonous organic matter can contribute to a larger fraction of the DIC budget. In that context, we note that low δ13C values are also apparent among eels (as low as −27.7‰, with 22% of individuals falling below the range for lacustrian taxa) which have the most ecological flexibility of our taxa, enabling them to thrive anywhere along a wetland-to-lacustrian continuum. A strong positive correlation between δ13C and δ34S for eels (n = 36, Pearson’s r = 0.674, p = <0.000) indicates that factors driving δ34S downward occur in areas where δ13C is more impacted by wetland isotopic compositions (i.e., influenced by 13C-depleted carbon from allochthonous terrestrial detritus). What is more, while this correlation does not appear within other taxa (as expected given their less flexible ecologies, although see below for more detail; Supplementary Table S7), it is observed to a similar degree across the entire dataset (i.e., from all species; Figures 2A, n = 132, Pearson’s r = 0.608, p = <0.000), indicating that the relationship operates at a much broader level than species-specific behavior. In other words, the known ecologies of these taxa, coupled with the observed isotopic patterns (in δ34S and the correlation between δ13C and δ34S) matching expectations based on these ecologies, strongly supports our interpretation that the primary driver of variation in δ34S toward the lower end of the spectrum is an influence from 34S-depleted sulfides in wetlands.

Results include another noteworthy species-specific pattern. The δ13C and δ34S correlation between wetland use and the most ecologically flexible taxa (i.e., eels) does not appear in beavers. In particular, although beavers are wetland specialists, with diets that include wetland plants as well as terrestrial trees, we do not see δ13C co-vary with δ34S. Instead we see δ13C values (n = 14, −23.0 ± 1.3‰) that appear to consistently suggest that the primary production upon which beavers relied drew CO2 from atmospheric (terrestrial; i.e., higher δ13C) sources3 rather than from sources where CO2 came from the breakdown of allochthonous organic matter (i.e., lower δ13C). Dietary ecology, however, offers a clear explanation for this difference (Baker and Hill, 2003). Of the aquatic plants consumed by beavers, the favorites are lily pads (Nymphaea spp., Nuphar spp.) and other emergent aquatic vegetation (Jenkins, 1981; Novak, 1987), which, unlike other, fully aquatic primary producers (e.g., algae, macrophytes), draw a significant portion of their CO2 directly from the atmosphere. This means that, although specialists in wetlands habitats, beavers are not necessarily expected to share low δ13C values with other wetland denizens. For instance, in contrast to beavers, eels and turtles (carnivores and omnivores) consume a wider range of prey for which the basal primary production occurs in the water column (i.e., integrating isotopic compositions influenced by CO2 from the breakdown of allochthonous materials). It therefore makes sense that beavers, while still showing a wetland diet spectrum, sit somewhat apart from other taxa. This also explains why a relationship between δ13C and δ34S for muskrats is weaker (and not statistically significant, Supplementary Table S7). While muskrats are omnivorous, their dominant food sources are plants, with overall diets that can be more similar isotopically to beavers that focus on emergent aquatic vegetation.

Our data indicate that wetland fauna can have δ34S values that incorporate an isotopic signal from sulfides. This means that higher-level consumers using resources from these environments, including humans, can have δ34S values that do not reflect prevailing local baselines. While this phenomenon has been documented archaeologically before for various marine and coastal settings (Szpak and Buckley, 2020; Guiry et al., 2021a,c), its observation among vertebrates in freshwater wetlands is new and is something that could have a significant, and largely overlooked, impact on interpretations of δ34S data from archaeological and ecological contexts.

To date, the vast majority of archaeological studies examining past diet and mobility have done so based on the premise that δ34S compositions in consumers primarily reflect underlying geology and hydrology, with the added caveat that these values could be influenced near the top end of a typical δ34S range by marine sulfates (through either sea spray or direct consumption of marine primary producers and animals; Nehlich, 2015). This study shows that the use of wetland resources could influence consumer δ34S towards the bottom end of a typical δ34S interpretive range. In other words, where interpretations involve data from humans or animals that could have lived near and used wetland resources, δ34S values could be influenced. This finding has important, global implications for the utility of δ34S as a tool for reconstructing past human mobility and migration. The existence of a source of δ34S variation that is not linked to location (i.e., not derived from geology or hydrology), means that human δ34S compositions, even at inland areas (i.e., far from sea spray influences and where marine foods were not available), could be driven at least partly by wetland-oriented dietary choices and would, therefore, not provide a faithful provenance tracer. Because wetlands are globally distributed and provide a resource-rich area attracting human habitation, this finding could have implications for interpretation of δ34S data on a broad scale. While this could make interpretation of potentially affected data more complicated, it should also help to clarify interpretations of lower δ34S, which are sometimes left with tentative interpretations (e.g., Pearson et al., 2016; Rand et al., 2020; Le Roy et al., 2022), by linking them with potential consumption of local wetland resources, rather than mobility to distant or unknown areas with very low δ34S baselines.

It is also worth considering these data for what they can tell us about variation in wetland δ34S as well as our ability to identify it archaeologically. It is apparent from the wide δ34S ranges among species, even within our baseline groups, that δ34S associated with ecotonal areas that include wetlands can be highly variable. It is only when we combine a wide range of ecologically diverse taxa, constrained by other isotopic data, that a cohesive pattern emerges. The high degree of variation may simply reflect the fact that these kinds of natural experiments, particularly ones using archaeological materials that integrate longer time spans, are prone to incorporating data influenced by a wider range of biogeochemical processes. It is nonetheless the case that, for mobile, higher-trophic-level vertebrate consumers, especially in archaeological studies, in which our aim is to interpret cultural behaviors from both human and animal data, these kinds of issues with broader spatial and temporal scales will often necessarily be present. This heightened variability means that we can expect that interpreting smaller numbers of (or isolated) δ34S data from bone collagen (typically the only material available to archaeologists) may be challenging or impossible and suggests that larger numbers of samples may be needed to observe clear patterns. Additional research with plants and bone collagen from contemporary samples from known species and carefully selected locations may allow this relationship to be characterized in finer detail and perhaps offer new insights to help further constrain interpretations of wetland-related δ34S variation in the archaeological past.

A further point, of broader relevance, is that these data also speak to the value of including a wider variety of taxa in archaeological and ecological faunal isotopic baselines. If, for instance, we had instead examined only one or two of these species, the overall pattern we have observed might have been less clear. In other words, it is only by incorporating data from a broader suite of species across ecosystems that we gain a fuller understanding of the primary axes of isotopic variation relevant for interpreting human and animal behaviors. While the key roles that faunal baselines, particularly from animals of major economic importance, can play in isotopic research have long been recognized (Katzenberg, 1989), in this context, our results provide a clear example for the value of sampling more widely, and including species that are traditionally overlooked or seen as having less interpretive value. In order to make space for this kind of open exploration, and generation of more substantial datasets, curators may need to remain open to larger, broad-scale sampling programs. In this way we can gain a more detailed picture of the wider environmental framework in which humans and animals lived. At the same time, we acknowledge that budgetary constraints and limitations on what taxa have been preserved in relevant archaeological assemblages may mean that some archaeological projects will necessarily be limited to smaller-scale, less taxonomically diverse sampling programs.

Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, while our finding of a potentially globally significant source of variation at the bottom end of the δ34S spectrum adds a source of interpretive uncertainty for some research questions, it opens the way for others. Wetlands were and are areas of tremendous cultural and ecological importance (Bernick, 2011). At the same time that wetlands continue to disappear due to human impacts (Davidson, 2014), we are learning more about the ecosystem services they provide and their value for mitigating or reversing major environmental issues, such as biodiversity loss, pollution/eutrophication, and climate change (Zedler and Kercher, 2005). In this context, having a broad-scale marker for human interactions with and use of wetlands in the past could help shed light and temporal depth on how wetlands have responded to human land management pressures through time. Moreover, such a marker for changes in the importance of wetlands for the ecology of archaeological fauna (whether wild or domestic) could provide an important source of information about the long-term ecological structure of wetlands in general, and in particular those which have long since disappeared due to human impacts. This can further inform archaeological interpretation of the importance of wetland resources for ancestors, thereby helping contemporary Indigenous peoples to reclaim part of their heritage (General and Warrick, 2012; Lesage, 2016). These findings also open the way for a range of historical-ecological research programs that could use δ34S of archaeological animal remains to contribute directly to our understanding of the ecology of endangered or recovering wetland species. In turn, information from these and other lines of study have potential to help shape future conservation strategy and policy.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

EG designed research. SN-H, TO, and EG contributed samples and background knowledge for analysis. EG performed isotopic analyses and interpreted results. EG wrote the manuscript with assistance from PS, SN-H, and TO. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by Department of Anthropology, University of British Columbia; Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Insight Development Grant. The award number for the listed Insight Development Grant is “430-2017-01120”.

We thank representatives of descendant First Nations (Louis Lesage, Huron-Wendat Nation, and Henry Lickers, Mohawks of Akwesasne) for permission for this analysis. For a full list of persons and organizations we wish to thank, see the Supplementary material.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2022.953042/full#supplementary-material

1. ^While there are several large lakes in the study region, the most important major water body for this study is Lake Ontario (Figure 1), in part because Niagara Falls created a natural barrier preventing key species, including Atlantic salmon and American eel, from inhabiting upstream lakes.

2. ^The term "pelagic" can refer to both marine and freshwater environments. Samples come from Lake Ontario’s now-extinct endemic complex of Atlantic salmon populations, which were potamodromous. In other words, these fish lived their entire lives in Lake Ontario and its tributaries and did not travel to the ocean as part of their life cycle.

3. ^Note that mustelids and squirrels, although also terrestrial, are expected to have higher δ13C. For squirrels, this is based on their consumption of tree mast that, being composed of non-photosynthetic tissues, is relatively 13C enriched (Guiry et al., 2021b) in the context of local C3 plant foods. For mustelids, this is based on their consumption of taxa that focus on tree mast, such as squirrels.

Ambrose, S. H. (1990). Preparation and characterization of bone and tooth collagen for isotopic analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 17, 431–451. doi: 10.1016/0305-4403(90)90007-R

Bagarinao, T. (1992). Sulfide as an environmental factor and toxicant: tolerance and adaptations in aquatic organisms. Aquat. Toxicol. 24, 21–62. doi: 10.1016/0166-445X(92)90015-F

Baker, B., and Hill, E. (2003). “Beaver (Castor canadensis)” in Wild mammals of North America: Biology, management, and conservation. eds. G. A. Feldhamer, B. C. Thompson, and J. A. Chapman (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press), 288–310.

Bernick, K. (2011). Hidden dimensions: The cultural significance of wetland archaeology. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Bottrell, S. H., and Newton, R. J. (2006). Reconstruction of changes in global sulfur cycling from marine sulfate isotopes. Earth Sci. Rev. 75, 59–83. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.10.004

Canfield, D. (2001). Biogeochemistry of sulfur isotopes. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 43, 607–636. doi: 10.2138/gsrmg.43.1.607

Canfield, D. E., and Teske, A. (1996). Late Proterozoic rise in atmospheric oxygen concentration inferred from phylogenetic and Sulfur-isotope studies. Nature 382, 127–132. doi: 10.1038/382127a0

Carlson, P. R., and Forrest, J. (1982). Uptake of dissolved sulfide by Spartina alterniflora: evidence from natural sulfur isotope abundance ratios. Science 216, 633–635. doi: 10.1126/science.216.4546.633

Chambers, L. A., Trudinger, P. A., Smith, J. W., and Burns, M. S. (1975). Fractionation of sulfur isotopes by continuous cultures of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Can. J. Microbiol. 21, 1602–1607. doi: 10.1139/m75-234

Chasar, L. C., Chanton, J. P., Koenig, C. C., and Coleman, F. C. (2005). Evaluating the effect of environmental disturbance on the trophic structure of Florida bay, United States: Multiple stable isotope analyses of contemporary and historical specimens. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50, 1059–1072. doi: 10.4319/lo.2005.50.4.1059

Colborne, S. F., Rush, S. A., Paterson, G., Johnson, T. B., Lantry, B. F., and Fisk, A. T. (2016). Estimates of lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush) diet in Lake Ontario using two and three isotope mixing models. J. Great Lakes Res. 42, 695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jglr.2016.03.010

Cornwell, J. C., Stevenson, J. C., and Neill, C. (1995). Biogeochemical origin of δ34S isotopic signatures in a prairie marsh. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 52, 1816–1820. doi: 10.1139/f95-174

COSEWIC. (2012). COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife. ed. Taylor, E.

COSEWIC. (2017). COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens in Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife. ed. Mandrak, N.

Craig, O., Ross, R., Andersen, S. H., Milner, N., and Bailey, G. (2006). Focus: Sulfur isotope variation in archaeological marine fauna from northern Europe. J. Archaeol. Sci. 33, 1642–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2006.05.006

Dance, K. M., Rooker, J. R., Shipley, J. B., Dance, M. A., and Wells, R. J. D. (2018). Feeding ecology of fishes associated with artificial reefs in the Northwest Gulf of Mexico. PLoS One 13:e0203873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203873

Davidson, N. C. (2014). How much wetland has the world lost? Long-term and recent trends in global wetland area. Mar. Freshw. Res. 65, 934–941. doi: 10.1071/MF14173

DeNiro, M. J., and Epstein, S. (1981). Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 45, 341–351. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(81)90244-1

Findlay, A. J., and Kamyshny, A. (2017). Turnover rates of intermediate sulfur species (Sx2-, S0, S2O32-, S4O62-, SO32-) in anoxic freshwater and sediments. Front. Microbiol. 8:2551. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02551

Finlay, J. C., and Kendall, C. (2007). Stable isotope tracing of temporal and spatial variability in organic matter sources to freshwater ecosystems. Stable Isotop. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2, 283–333. doi: 10.1002/9780470691854.ch10

France, R. (1995). Carbon-13 enrichment in benthic compared to planktonic algae: foodweb implications. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 124, 307–312. doi: 10.3354/meps124307

Frederiksen, M. S., Holmer, M., Borum, J., and Kennedy, H. (2006). Temporal and spatial variation of sulfide invasion in eelgrass (Zostera marina) as reflected by its sulfur isotopic composition. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 2308–2318. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.2308

Fry, B. (1988). Food web structure on Georges Bank from stable C, N, and S isotopic compositions. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33, 1182–1190. doi: 10.4319/lo.1988.33.5.1182

Fry, B., and Chumchal, M. M. (2011). Sulfur stable isotope indicators of residency in estuarine fish. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 1563–1576. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.5.1563

Fry, B., Scalan, R. S., Winters, J. K., and Parker, P. L. (1982). Sulfur uptake by salt grasses, mangroves, and seagrasses in anaerobic sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 46, 1121–1124. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(82)90063-1

Guiry, E. (2019). Complexities of stable carbon and nitrogen isotope biogeochemistry in ancient freshwater ecosystems: implications for the study of past subsistence and environmental change. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7. 1–24. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00313

Guiry, E. J., Buckley, M., Orchard, T. J., Hawkins, A. L., Needs-Howarth, S., Holm, E., et al. (2020a). Deforestation caused abrupt shift in Great Lakes nitrogen cycle. Limnol. Oceanogr. 65, 1921–1935. doi: 10.1002/lno.11428

Guiry, E. J., Kennedy, J. R., O’Connell, M. T., Gray, D. R., Grant, C., and Szpak, P. (2021c). Early evidence for historical overfishing in the Gulf of Mexico. Science. Advances 7:2525. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abh2525

Guiry, E. J., Needs-Howarth, S., Friedland, K. D., Hawkins, A. L., Szpak, P., Macdonald, R., et al. (2016a). Lake Ontario salmon (Salmo salar) were not migratory: a long-standing historical debate solved through stable isotope analysis. Sci. Rep. 6:36249. doi: 10.1038/srep36249

Guiry, E., Noël, S., and Fowler, J. (2021a). Archaeological herbivore δ13C and δ34S provide a marker for saltmarsh use and new insights into the process of 15N-enrichment in coastal plants. J. Archaeol. Sci. 125:105295. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2020.105295

Guiry, E., Orchard, T. J., Needs-Howarth, S., and Szpak, P. (2021b). Isotopic evidence for garden hunting and resource depression in the late woodland of northeastern North America. Am. Antiq. 86, 90–110. doi: 10.1017/aaq.2020.86

Guiry, E. J., Royle, T. C. A., Orchard, T. J., Needs-Howarth, S., Yang, D. Y., and Szpak, P. (2020b). Evidence for freshwater residency among Lake Ontario Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) spawning in New York. J. Great Lakes Res. 46, 1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.jglr.2020.05.009

Guiry, E., and Szpak, P. (2020). Seaweed-eating sheep show that δ34S evidence for marine diets can be fully masked by sea spray effects. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 34:e 8868. doi: 10.1002/rcm.8868

Guiry, E. J., and Szpak, P. (2021). Improved quality control criteria for stable carbon and nitrogen isotope measurements of ancient bone collagen. J. Archaeol. Sci. 132:105416. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2021.105416

Guiry, E. J., Szpak, P., and Richards, M. P. (2016b). Effects of lipid extraction and ultrafiltration on stable carbon and nitrogen isotopic compositions of fish bone collagen. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 30, 1591–1600. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7590

Habicht, K. S., and Canfield, D. E. (1997). Sulfur isotope fractionation during bacterial sulfate reduction in organic-rich sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 5351–5361. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(97)00311-6

Habicht, K. S., and Canfield, D. E. (2001). Isotope fractionation by sulfate-reducing natural populations and the isotopic composition of sulfide in marine sediments. Geology 29, 555–558. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0555:IFBSRN>2.0.CO;2

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A., and Ryan, P. D. (2001). PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4:9

Henry, A. P., Barnett, P. J., and Cowan, W. R. (2008). Quaternary geology of Ontario, southern sheet, Ontario geological survey, M 2556. Sudbury, Ontario: Ministry of Energy, Northern Development and Mines.

Hesslein, R., Capel, M., and Fox, D. (1988). Sulfur isotopes in sulfate in the inputs and outputs of a Canadian shield watershed. Biogeochemistry 5, 263–273. doi: 10.1007/BF02180067

Hobson, K. A. (2019). “Application of isotopic methods to tracking animal movements,” in Tracking animal migration with stable isotopes. eds. K. A. Hobson and L. I. Wassenaar Second ed (New York: Academic Press), 85–115. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-814723-8.00004-0

Hobson, K. A., and Clark, R. G. (1992). Assessing avian diets using stable isotopes I: turnover of 13C in tissues. Condor 94, 181–188. doi: 10.2307/1368807

Hodell, D. A., and Schelske, C. L. (1998). Production, sedimentation, and isotopic composition of organic matter in Lake Ontario. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 200–214. doi: 10.4319/lo.1998.43.2.0200

Hyland, C., Scott, M. B., Routledge, J., and Szpak, P. (2021). Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope variability of bone collagen to determine the number of isotopically distinct specimens. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 29, 666–686. doi: 10.1007/s10816-021-09533-7

Jellyman, D. J., and Arai, T. (2016). “Juvenile eels: upstream migration and habitat use,” in Biology and ecology of anguillid eels. ed. T. Arai (Boco Ratton, FL: CRC Press), 171–191.

Jenkins, S. (1981). “Problems, progress, and prospects in studies of food selection by beavers,” in Proceedings of the worldwide furbearer conference. eds. A. Chapman and D. Pursley (Worldwide Furbearer Conference: Baltimore, MD), 559–579.

Jørgensen, B. B. (1982). Mineralization of organic matter in the sea bed—the role of sulfate reduction. Nature 296, 643–645. doi: 10.1038/296643a0

Jørgensen, B. B., Findlay, A. J., and Pellerin, A. (2019). The biogeochemical sulfur cycle of marine sediments. Front. Microbiol. 10:849. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00849

Kaplan, I., and Rittenberg, S. (1964). Microbiological fractionation of Sulfur isotopes. Microbiology 34, 195–212.

Katzenberg, M. A. (1989). Stable isotope analysis of archaeological faunal remains from southern Ontario. J. Archaeol. Sci. 16, 319–329. doi: 10.1016/0305-4403(89)90008-3

Kemp, A., and Thode, H. (1968). The mechanism of the bacterial reduction of sulfate and of sulfite from isotope fractionation studies. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 32, 71–91. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(68)90088-4

Koch, M., and Mendelssohn, I. (1989). Sulfide as a soil phytotoxin: differential responses in two marsh species. J. Ecol. 77, 565–578. doi: 10.2307/2260770

Koch, M. S., Mendelssohn, I. A., and McKee, K. L. (1990). Mechanism for the hydrogen sulfide-induced growth limitation in wetland macrophytes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 35, 399–408. doi: 10.4319/lo.1990.35.2.0399

Krajcarz, M. T., Krajcarz, M., Drucker, D. G., and Bocherens, H. (2019). Prey-to-fox isotopic enrichment of 34S in bone collagen: implications for paleoecological studies. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 33, 1311–1317. doi: 10.1002/rcm.8471

Krouse, H. (1989). “Sulfur isotope studies of the pedosphere and biosphere” in Stable isotopes in ecological research. eds. W. Rundel, J. Ehleringer, and K. Nagy (New York: Springer), 424–444. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-3498-2_24

Lamb, A., and Madgwick, R. (2022). “Wet feet—using Sulfur isotope analysis to identify wetland dwellers,” in United Kingdom archaeological science conference (Aberdeen)

Lamers, L. P., Govers, L. L., Janssen, I. C., Geurts, J. J., Van der Welle, M. E., Van Katwijk, M. M., et al. (2013). Sulfide as a soil phytotoxin—a review. Front. Plant Sci. 4:268. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00268

Le Roy, M., Magniez, P., and Goude, G. (2022). Stable-isotope analysis of collective burial sites in southern France at late Neolithic/early bronze age transition. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 32, 396–407. doi: 10.1002/oa.3074

Lesage, C.-L. (2016). Écologie historique et connaissances écologiques traditionnelles huronnes-wendat relatives à douze espèces animales et végétale dans le Wendake Sud: Report prepared by Bureau du Nionwentsïo, Nation huronne-wendat, in collaboration with Environment and Climate Change Canada/Environnement et Changement climatique Canada.

Longin, R. (1971). New method of collagen extraction for radiocarbon dating. Nature 230, 241–242. doi: 10.1038/230241a0

Mac Culloch, R. D. (2002). The ROM field guide to amphibians and reptiles of Ontario. Ontario: McClelland & Stewart Limited.

Mitchell, M. J., Roy Krouse, H., Mayer, B., Stam, A. C., and Zhang, Y. (1998). “Chapter 15- use of stable isotopes in evaluating sulfur biogeochemistry of Forest ecosystems,” in Isotope tracers in catchment hydrology. eds. C. Kendall and J. J. McDonnell (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 489–518. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-81546-0.50022-7

Mizota, C., Shimoyama, S., and Yamanaka, T. (1999). An isotopic characterization of sulfur uptake by benthic animals from Tsuyazaki inlet, northern Kyushu, Japan. Benthos Res. 54, 81–85. doi: 10.5179/benthos1996.54.2_81

Morris, J. T., Haley, C., and Krest, R. (1996). Effects of Sulfide on Growth and Dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) Concentration in Spartina Alterniflora. In: Kiene RP, Visscher PT, Keller MD, Kirst GO, editors. Biological and Environmental Chemistry of DMSP and Related Sulfonium Compounds. Boston, MA: Springer, US. 87–95.

Nehlich, O. (2015). The application of Sulfur isotope analyses in archaeological research: a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 142, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.12.002

Nehlich, O., Barrett, J. H., and Richards, M. P. (2013). Spatial variability in Sulfur isotope values of archaeological and modern cod (Gadus morhua). Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 27, 2255–2262. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6682

Novak, M. (1987). “Beaver” in Wild furbearer management and conservation in North America. eds. M. Novak, J. A. Baker, M. E. Obbard, and B. Malloch (Toronto: Ontario Trappers Association and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources), 283–312.

Oakes, J. M., and Connolly, R. M. (2004). Causes of sulfur isotope variability in the seagrass, Zostera capricorni. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 302, 153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2003.10.011

OGS. (1991). Bedrock geology of Ontario, southern sheet, Ontario geological survey, map 2544. Sudbury, Ontario: Ministry of Energy, Northern Development and Mines.

Pearson, M. P., Chamberlain, A., Jay, M., Richards, M., Sheridan, A., Curtis, N., et al. (2016). Beaker people in Britain: migration, mobility and diet. Antiquity 90, 620–637. doi: 10.15184/aqy.2016.72

Peterson, B. J., and Howarth, R. W. (1987). Sulfur, carbon, and nitrogen isotopes used to trace organic matter flow in the salt-marsh estuaries of Sapelo Island, Georgia. Limnol. Oceanogr. 32, 1195–1213. doi: 10.4319/lo.1987.32.6.1195

Postgate, J. (1959). Sulfate reduction by bacteria. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 505–520. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.13.100159.002445

Privat, K. L., O'Connell, T. C., and Hedges, R. E. (2007). The distinction between freshwater- and terrestrial-based diets: methodological concerns and archaeological applications of Sulfur stable isotope analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 34, 1197–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2006.10.008

Rand, A. J., Freiwald, C., and Grimes, V. (2021). A multi-isotopic (δ13C, δ15N, and δ34S) faunal baseline for Maya subsistence and migration studies. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 37:102977. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102977

Rand, A. J., Matute, V., Grimes, V., Freiwald, C., Źrałka, J., and Koszkul, W. (2020). Prehispanic Maya diet and mobility at Nakum, Guatemala: a multi-isotopic approach. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 32:102374. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102374

Rees, C. E., Jenkins, W. J., and Monster, J. (1978). The Sulfur isotopic composition of ocean water sulfate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 42, 377–381. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(78)90268-5

Richards, M., Fuller, B., and Hedges, R. (2001). Sulfur isotopic variation in ancient bone collagen from Europe: implications for human palaeodiet, residence mobility, and modern pollutant studies. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 191, 185–190. doi: 10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00427-7

Sayle, K. L., Brodie, C. R., Cook, G. T., and Hamilton, W. D. (2019). Sequential measurement of δ15N, δ13C and δ34S values in archaeological bone collagen at the Scottish universities environmental research Centre (SUERC): a new analytical frontier. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 33, 1258–1266. doi: 10.1002/rcm.8462

Schelske, C. L., and Hodell, D. A. (1991). Recent changes in productivity and climate of Lake Ontario detected by isotopic analysis of sediments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 36, 961–975. doi: 10.4319/lo.1991.36.5.0961

Schwarcz, H. P., and Schoeninger, M. J. (1991). Stable isotope analyses in human nutritional ecology. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 34, 283–321. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330340613

Stribling, J. M., Cornwell, J. C., and Currin, C. (1998). Variability of stable sulfur isotopic ratios in Spartina alterniflora. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 166, 73–81. doi: 10.3354/meps166073

Szpak, P., and Buckley, M. (2020). Sulfur isotopes (δ34S) in Arctic marine mammals: indicators of benthic vs. pelagic foraging. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 653, 205–216. doi: 10.3354/meps13493

Szpak, P., Metcalfe, J. Z., and Macdonald, R. A. (2017). Best practices for calibrating and reporting stable isotope measurements in archaeology. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 13, 609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.05.007

Thode, H. (1991). “Sulfur isotopes in nature and the environment: an overview” in Stable isotopes: Natural and anthropogenic Sulfur in the environment. eds. H. Krouse and V. Grinenko (Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley), 1–26.

Vika, E. (2009). Strangers in the grave? Investigating local provenance in a Greek bronze age mass burial using δ34S analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 2024–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2009.05.022

Zazzo, A., Monahan, F., Moloney, A., Green, S., and Schmidt, O. (2011). Sulfur isotopes in animal hair track distance to sea. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 25, 2371–2378. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5131

Zedler, J. B., and Kercher, S. (2005). Wetland resources: status, trends, ecosystem services, and restorability. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 30, 39–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144248

Keywords: wetlands, sulfur isotopes, historical ecology, migration, archaeology

Citation: Guiry EJ, Orchard TJ, Needs-Howarth S and Szpak P (2022) Freshwater wetland–driven variation in sulfur isotope compositions: Implications for human paleodiet and ecological research. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10:953042. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2022.953042

Received: 25 May 2022; Accepted: 23 November 2022;

Published: 21 December 2022.

Edited by:

Jason Newton, University of Glasgow, United KingdomReviewed by:

Derek Hamilton, University of Glasgow, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Guiry, Orchard, Needs-Howarth and Szpak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eric J. Guiry, ZWpnMjZAbGVpY2VzdGVyLmFjLnVr

†ORCID: Eric J. Guiry https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1467-1521

Trevor J. Orchard https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9040-7522

Suzanne Needs-Howarth https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4040-0810

Paul Szpak https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1364-6834

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.