94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Ecol. Evol., 01 November 2021

Sec. Chemical Ecology

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.760368

This article is part of the Research TopicChemical Ecology of Plant-Biotic Interactions in a Changing EnvironmentView all 6 articles

The damage of Riptortus pedestris is exceptional by leading soybean plants to keep green in late autumn. Identification of the salivary proteins is essential to understand how the pest-plant interaction occurs. Here, we have tried to identify them by a combination of proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. The transcriptomes of salivary glands from R. pedestris males, females and nymphs showed about 28,000 unigenes, in which about 40% had open reading frames (ORFs). Therefore, the predicted proteins in the transcriptomes with secretion signals were obtained. Many of the top 1,000 expressed transcripts were involved in protein biosynthesis and transport, suggesting that the salivary glands produce a rich repertoire of proteins. In addition, saliva of R. pedestris males, females and nymphs was collected and proteins inside were identified. In total, 155, 20, and 11 proteins were, respectively, found in their saliva. We have tested the tissue-specific expression of 68 genes that are likely to be effectors, either because they are homologs of reported effectors of other sap-feeding arthropods, or because they are within the top 1,000 expressed genes or found in the salivary proteomes. Their potential functions in regulating plant defenses were discussed. The datasets reported here represent the first step in identifying effectors of R. pedestris.

Many hemipterans are important pests that pierce their needle-like mouthparts (stylets) into crop plants and feed on sap. They eject gelling saliva during the feeding that solidifies quickly and forms a continuous sheath in host plants. The sheath is a feeding channel and protects stylets against plant toxins. Meanwhile, watery saliva is used to digest food, regulate plant defenses and facilitate pathogen transmissions (Miles, 1999; Will et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2019c). In order to study the molecular mechanism in interactions between pests and crops, we need to identify the salivary proteins and analyze their functions. Transcriptome analysis of salivary glands and proteome analysis of secreted proteins are two efficient ways to identify salivary proteins. The analyses have been performed on some agriculturally important hemipterans, such as aphids (Carolan et al., 2011; Boulain et al., 2018), planthoppers (Ji et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2018), whiteflies (Su et al., 2012) and leafhoppers (Coudron et al., 2007; DeLay et al., 2012).

Though many stink bugs are also important pests, identification of salivary effectors has been largely ignored and previous studies have mainly focused on the activities of digestive enzymes. For example, salivary glands of some pod-sucking coreid bugs produce a large amount of proteinases that are probably used to digest proteins in beans (Soyelu et al., 2007). The coreid bug Mictis profana (Fabr.) uses a sucrase to hydrolyze sucrose into monosaccharides during feeding, thereby increasing local osmotic pressure and unloading the solutes of neighboring plant cells (Miles and Taylor, 1994; Taylor and Miles, 1994). The mirid bug Apolygus lucorum (Meyer-Dür) is able to produce a series of digestive enzymes by salivary glands, such as pectinases, polygalacturonases, amylases, cellulases and proteinases (Tan et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017). Transcripts of salivary glands were sequenced in some true bug species (Francischetti et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2016). Still, the studies paid main attention to digestive enzymes again, whereas very few discussed the effector functions of the salivary proteins. However, a recent study found that a glutathione peroxidase was highly expressed in the salivary glands of A. lucorum, who probably use it to eliminate the reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation in plants (Dong et al., 2020).

In other hemipterans, a variety of salivary effectors that affect plant immunity have been identified (Hogenhout et al., 2009; Sharma et al., 2014). For example, physical puncturing of phloem sieve elements normally leads to a rapid occlusion of sieve elements because of the formation of insoluble protein complexes (e.g., forisomes) inside that are valves of sieve tubes. Phloem-feeding hemipterans, such as aphids and planthoppers, prevent phloem occlusion and the related defense responses by using salivary proteins, including calcium-binding proteins. The proteins bind calcium, thereby weakening the signaling of defenses and avoiding the occlusion of sieve elements (Will et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2014; Ye et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019c). In addition, hemipteran herbivores commonly use catalases and peroxidases that are ubiquitous heme enzymes to remove hydrogen peroxides in feeding sites (Sharma et al., 2014). Some salivary enzymes, such as phenol oxidases, dehydrogenases and cytochrome P450s, are often used to detoxify plant toxic compounds (Nicholson et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2014). In addition, non-enzymatic proteins have been increasingly identified in hemipteran saliva, and they often affect plant defenses via different mechanisms (Elzinga et al., 2014; Matsumoto and Hattori, 2018; Xu et al., 2019).

The bean bug Riptortus pedestris (Fab.) (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Alydidae) is an important pest on soybeans in East Asia. Very recently, the genome of R. pedestris was assembled (Huang et al., 2021b), which provides an important dataset in analyzing the functions of their genes. The pest invades soybean fields during flowering period and causes severe damage to soybeans by sucking pods (Endo et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2021). Severely damaged plants stay green in the stem and leaf in late autumn (Li et al., 2019), indicating that the salivary proteins of R. pedestris have possibly changed the plant development. Identification of the salivary proteins is the first step in understanding the plant’s response. Their salivary proteins have been identified by a combination of proteomic and transcriptomic analyses on salivary glands (Huang et al., 2021a). However, whether the proteins are able to be secreted into food is still unknown. And the comparisons among different developmental stages and between sexes are missing. Here, we studied the transcripts of the salivary glands of males, females and nymphs, with a special attention on identifying candidate effectors. In addition, the proteomes of male, female and nymph saliva were, respectively, analyzed. As a result, about 170 salivary proteins, in total, were found and their potential functions as effectors were also discussed.

The bean bug R. pedestris adults were collected in soybean fields, Nanjing, East China, in the summer of 2020. They were reared in tents (30 × 30 × 30 cm) in an incubator (25°C, LD = 16:8 h), where soybean seedlings (3–5 weeks old) and seeds (variety Lindou 10) were provided as food.

Thirty adults (male or female, 10-d old) or fourth-instar nymphs were anesthetized on ice and subsequently dissected to obtain salivary glands (Figure 1). The RNA was extracted by the TRIzol Total RNA Isolation Kit (Takara, Dalian, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of extracted RNA was verified by the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, CA, United States). Polyadenylated RNA (mRNA) was purified from the total RNA by using oligo(dT) magnetic beads and then the total mRNA was fragmented into short sequences in the presence of divalent cations at 94°C for 5 min. The cleaved RNA was transcribed, and the second-strand cDNA was obtained. After end-repair and adaptor ligation, the products were PCR-amplified and purified using Ampure XP Beads (Agencourt Bioscience, MA, United States) to create the cDNA library.

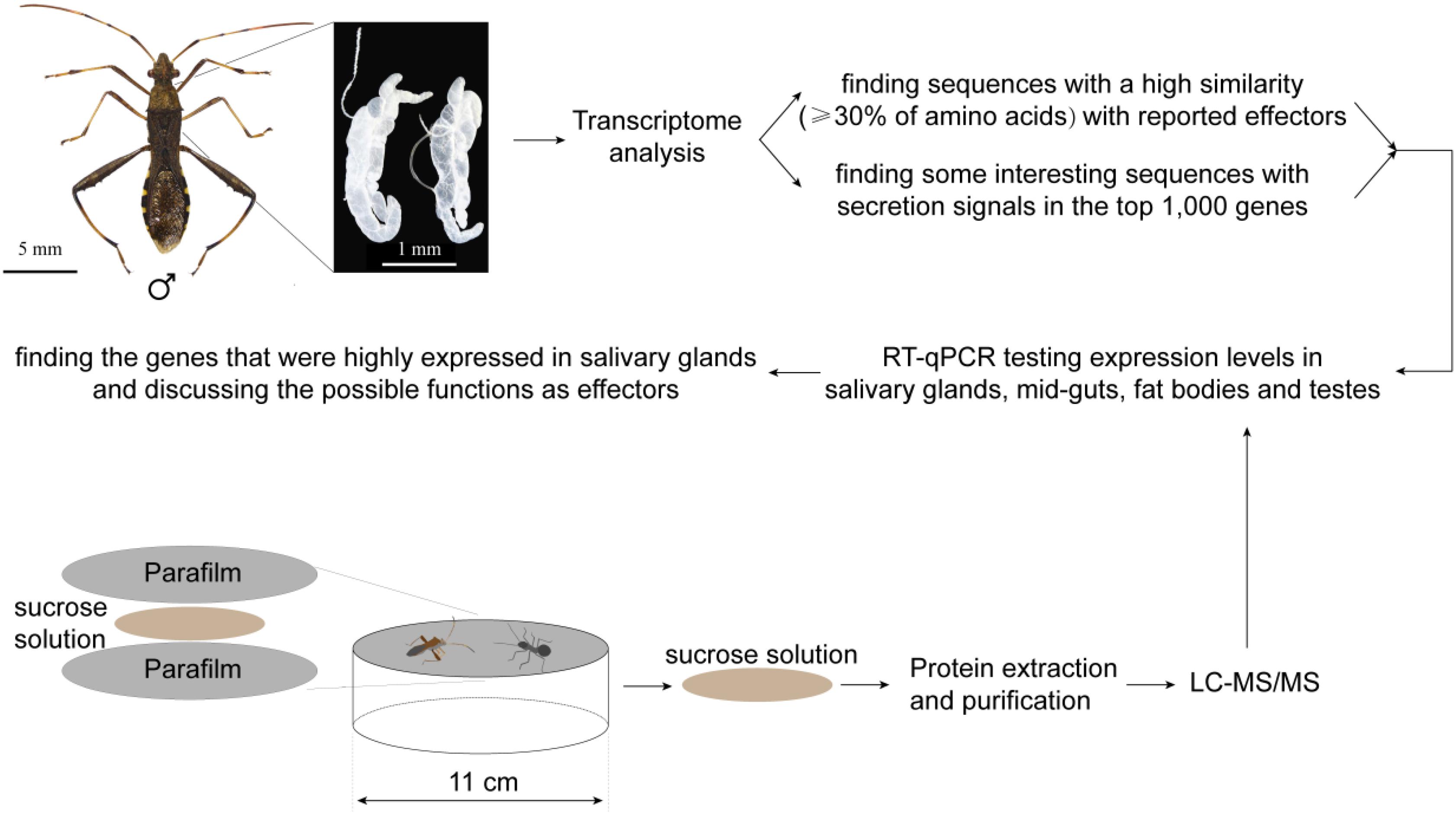

Figure 1. The procedure of the experiment and sequence analyses: salivary glands were dissected from the bean bugs (taking a male as an example here), and then the transcriptome was sequenced and analyzed. We tested the tissue-specific expression of 18 genes with secretion signals in the top 1,000 expressed genes, as well as 19 homologs of reported effectors of other sap-feeding arthropods. In addition, saliva of the bean bugs were collected and the proteomes were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The tissue-specific expression of 31 secreted salivary proteins was tested. The genes that are expressed more in salivary glands have a high potential as effectors, and their functions were discussed in the text.

The library was sequenced on the Illumina sequencing platform and the raw data were generated using Solexa GA pipeline 1.6. Low quality reads were removed, and the rest sequences were assembled using Short Oligonucleotide Analysis Package (SOAP) de novo software (Li et al., 2008), and then clustered by TGICL v2.0.6 to gain unique genes (Pertea et al., 2003). The clean reads of the transcriptomes have been deposited to SRA database with the accession number of PRJNA690963.

The sequences of unigenes were searched in one of four databases to obtain their annotations, including the NR database (NCBI1); the Gene Ontology (GO2), the KEGG Orthology (KEGG3) and the EuKaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG4).

TransDecoder.LongOrfs was used to extract the long open reading frames (ORFs). The ORFs were blasted in the SwissProt5 and Pfam databases6 by Diamond Blastp and Hmmscan, respectively. The coding sequences (CDSs) were extracted from the transcripts by TransDecoder 3.0.1 (Kim et al., 2015), and then the predicted proteins were obtained. Then, the SignalP 5.07 was used to test whether sequences have secretion signal peptides or not (Armenteros et al., 2019), while the TMHMM 2.08 was used to check the transmembrane areas of sequences (Krogh et al., 2001).

The predicted proteins with secretion signal peptides and simultaneously without transmembrane areas are likely to be secreted by salivary glands into saliva (Nielsen, 2017), and therefore with a relatively high potential in modulation of plant defenses. We had paid attention to the genes with secretion signals (about 192 individuals, Supplementary Table 1) in the top 1,000 expressed genes of the transcriptomes, and 18 genes were selected for testing their expression levels in different tissues (see below). In addition, the amino acid sequences of most reported effectors in sap-feeding arthropods were compared to the predicted proteins in the male transcriptome, and 19 proteins had a relatively high similarity (≥30%) with the effectors. Their expression levels were also compared between different tissues of R. pedestris.

Riptortus pedestris saliva was collected in a Petri dish (2 cm × 11 cm) whose open was covered by two layers of Parafilm with 2 ml sterile sucrose solution (2.5% in water) as food in between (Figure 1). The Parafilm was previously sterilized by 75% ethanol solution. The sucrose solution was prepared with aseptic water and filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter (Millipore, MA, United States) for the removal of microorganisms. Ten individuals (males, females or fourth-instar nymphs) were put in each Petri dish and the collection lasted 24 h. The collection was repeated 30 times. In total, 300 individuals were used. After collections, the sucrose solutions of each Petri dish were combined (about 60 ml) and concentrated by ultrafiltration (3-kDa, Amicon Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter Tube, Millipore; 5,000 g, 4°C, 30 min). The proteins were dissolved in 200 μl of SDT buffer (4% sodium dodecyl sulfate; 1 mM DTT and 100 mM Tris-HCl) and then were incubated in warm water for 15 min.

Subsequently, DTT was added into protein samples to a concentration of 100 mM, and then the samples were boiled for 5 min. After ultrafiltration (3-kDa; 14,000 g, 25°C, 10 min), 100 μl iodoacetamide (IAA) buffer (100 mM IAA in UA buffer) was used to dissolve the proteins, and then the samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in darkness. After ultrafiltration (3-kDa) again, the samples were washed with 100 μl UA buffer (8 M urea, 150 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) twice, and then washed with 100 μl NH4HCO3 buffer (25 mM, Sigma) twice. Finally, the proteins were digested overnight in 4 μg of trypsin (Sigma) in 40 μl NH4HCO3 buffer (25 mM) at 37°C. The digested peptides were collected by ultrafiltration (3-kDa) and were dissolved in 40 μl NH4HCO3 buffer (25 mM).

The digested peptides were separated by Thermo Scientific Easy nanoLC 1000 that was equipped with a C18 column (Thermo Scientific Acclaim PepMap100, 100 μm × 2 cm). Buffer A (0.1% formic acid in water) including 5% buffer B (84% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water) were used as the mobile phase for gradient separation. The sample was uploaded onto the column at a flow rate of 0.3 μl/min. Subsequently, the column was eluted by a linear gradient of buffer B at a flow rate of 0.25 μl/min (0–50 min, concentration increasing from 0 to 35%; 50–55 min, 35 to 100%; and finally pure buffer B maintained for 5 min).

The eluted peptides were analyzed by the Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). Full MS scans were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer over the range m/z 300–1800 with a mass resolution of 70000 (at m/z 200). The twenty most intense peaks with charge state ≥2 were fragmented in the higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) with a normalized collision energy of 30% (the isolation window was 2 m/z), and tandem mass spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer with a mass resolution of 17,500 at m/z 200. For all detections, the dynamic exclusion time was set to 60 s.

Proteins were identified and annotated by using Mascot 2.2 to search UniProt (see footnote 5) with the restriction to R. pedestris data. The following parameters were used: trypsin was selected as the enzyme; two missed cleavage sites were allowed; 20 ppm mass tolerances for MS and 0.6 Da for MS/MS fragment ions; oxidation was a variable modification; carbamidomethyl was a static modification.

The relative expression of selected genes (68 genes) in different tissues of R. pedestris males, including salivary glands, mid-guts, fat bodies and testes, were compared. Those are 31 proteins found in male saliva, 18 genes that exist in the top 1,000 transcripts and 19 genes (shown in Table 1) that are homologs to reported effectors. First, the total RNA of each tissue (30 individuals) was extracted by the TRIzol Total RNA Isolation Kit (Takara, Dalian, China). The first strand cDNA was synthesized from RNA by using the HiScript III RT SuperMix qPCR kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Then, real time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed on a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) by using the Top Green qPCR SuperMix kit (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). The reaction program started with an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 30 s, and then 40 cycles including two steps per cycle, 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 34 s, were performed. The gene-specific primers were designed by using the Primer Premier 5.0 software. To evaluate the primers, the cDNA concentrations were either unchanged, or further diluted by 4, 16, or 64 times. When amplification efficiencies ranged from 90–110%, and the R2 values were over 0.99 in the regression analysis, the primers were selected. Three biological replicates and three technical replicates were applied. The individual efficiency–corrected calculation method was used to compare the fold changes in expression levels of genes in mid-guts, testes and fat bodies, related to that in salivary glands (Rieu and Powers, 2009; Rao et al., 2013). Two housekeeping genes RpEF-1 and actin were used as reference genes (Lee et al., 2019). The primers and the result of the regression analysis of each gene were listed in the Supplementary File 1.

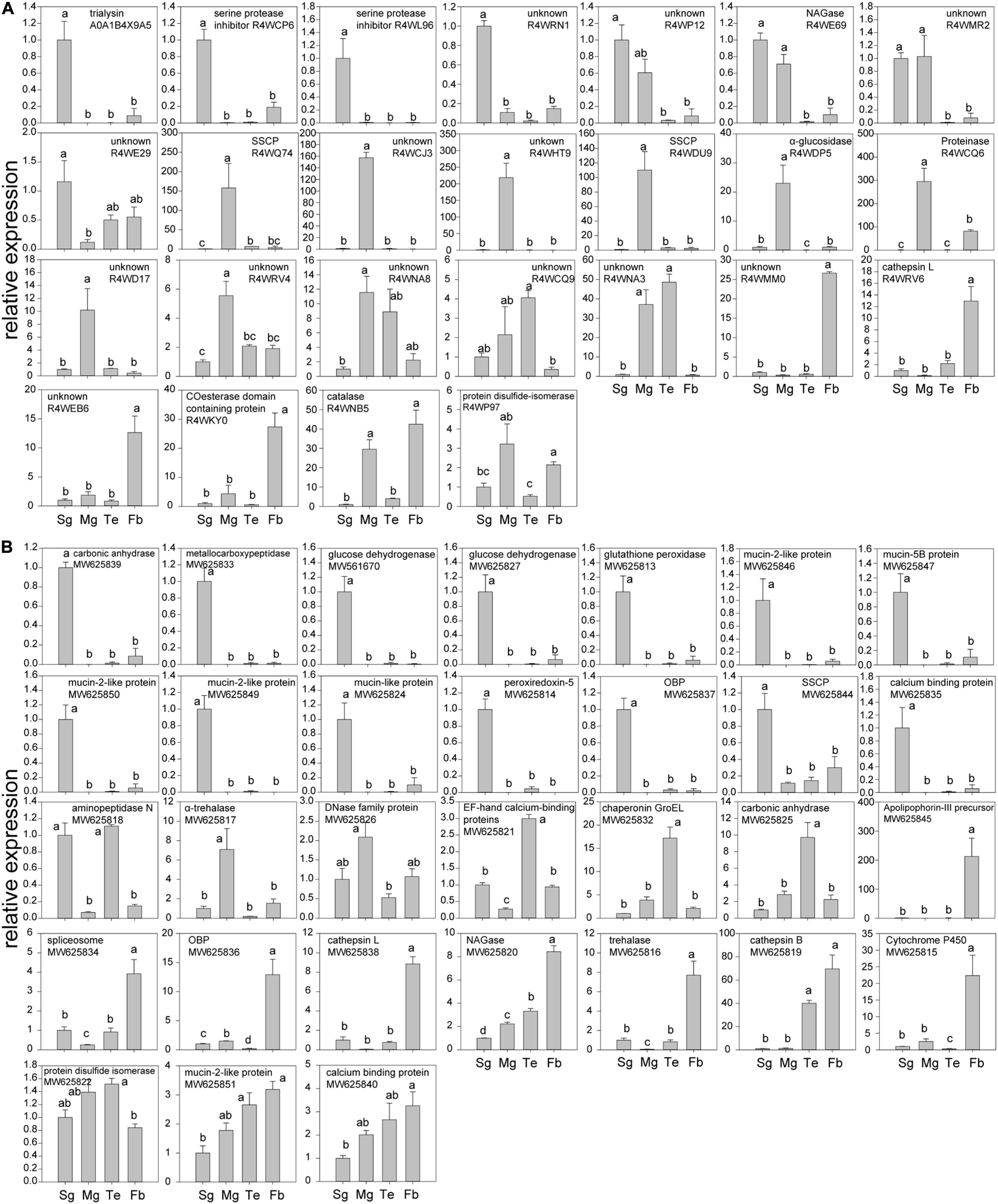

The statistical analyses on RT-qPCR data were carried out by using SigmaPlot 14 with one-way ANOVA tests. A Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis was used for pairwise comparisons. When the expression levels in four tissues (salivary glands, mid-guts, testes and fat bodies) were fitted with a normal distribution, the comparisons were performed in one run. Otherwise, pairwise comparisons were conducted by each pairs, and the normality always passed. Different lowercase letters above the bars in the Figure 2 indicate that there are significant differences (P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 2. RT-qPCR testing the tissue-specific expression of genes in salivary glands (Sg), mid-guts (Mg), testes (Te), and fat bodies (Fb) of R. pedestris males. (A) Expression levels of genes that encoded proteins found in male saliva; (B) genes that were selected from the transcriptome of salivary glands. The graphs were shown as: first are genes that are highly expressed in salivary glands, then those that are abundantly produced by mid-guts, testes, or fat bodies. In addition, the expression levels of another 12 genes (6 from the transcriptome and 6 found in saliva) were not biased to a tested tissue and their data were shown in Supplementary Table 4. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate that there are significant differences (P ≤ 0.05).

We obtained about 28,000 unigenes in the transcriptomes of salivary glands, and about 40% unigenes have complete ORFs (Supplementary Table 1). The average length of the unigenes was range from 828 to 1,001 bp with some differences between treatments. In the top 1,000 expressed genes of the male transcriptome, there were about 192 genes with the secretion signals (i.e., with secretion signal peptides and without transmembrane domain) and they are likely to be secreted from the gland cells without being anchored to the membranes (Cherqui and Tjallingii, 2000; Nielsen, 2017).

The top 1,000 expressed genes were mainly involved in ribosomal functions, amino acid metabolisms and posttranslational modifications etc. (Supplementary Figure 1), indicating that the salivary glands are specialized to produce many proteins. The GO annotations showed that many proteins in the salivary glands fulfilled binding and catalytic activities (Supplementary Figure 2).

Effector proteins normally have cysteine-rich residues and evolve quickly (Hogenhout and Bos, 2011; Dou and Zhou, 2012). A higher proportion of the secreted proteins in the transcriptome have cysteine-rich residues as opposed to that of housekeeping genes (Supplementary Figure 3). Though a high percentage of the secreted proteins matched with analogous sequences (E-value < 1 × 10–5) in the NCBI NR database, with or without the restriction to the R. pedestris data, the relevant ratios of housekeeping genes in the transcriptome were always higher (Supplementary Figure 3). The data together suggest that many secreted proteins in the salivary glands are still unknown and have a potential as effectors.

Dozens of effectors have been reported in hemipterans and other sap-sucking arthropods to date, and 19 homologous proteins (≥30% similarity in amino acids) were also found in the transcriptomes (Table 1). The expression levels of those genes were compared in different tissues (salivary glands, mid-guts, testes, and fat bodies) of R. pedestris males. In addition, in the 192 proteins with secretion signals in the top 1,000 expressed genes of the male transcriptome, 18 genes that are likely to be effectors based on their annotations (Sharma et al., 2014), were selected and their tissue-specific expression was examined. In addition, a total of 155 proteins were identified from watery saliva of R. pedestris males by LC-MS/MS analysis (Table 2). A significantly fewer proteins were found in female (only 20) and nymph (11) saliva (Supplementary Table 3). About 60% of female and nymph saliva proteins were also found in male saliva (Supplementary Table 3). The functions of many proteins in the proteomes remained unannotated (Table 2). The tissue-specific expression of 31 proteins (normally with a secretion signal) found in the male saliva was compared among different tissues. The expression levels that were significantly biased to a tested tissue (56 genes) were shown in the Figure 2. Otherwise, the data were given in Supplementary Table 4 (12 genes). In a previous paper, the salivary proteins of R. pedestris adults were identified by proteomic analysis on salivary glands (Huang et al., 2021a). By comparing to their data, we found that 127 proteins identified here were still novel (Supplementary Table 5), indicating that analysis on secreted proteins in saliva is an important way to identify salivary proteins of insects.

Riptortus pedestris has been one of the main pests on soybeans for decades in Korea and Japan (Endo et al., 2011). Recently, its outbreaks have also been found in China (Li et al., 2019). The severely damaged soybeans stay green in late autumn (Li et al., 2019). However, the mechanism is not yet understood. In the seed-filling period in soybean, leaves continuously transport photosynthates to seeds until leaf senescence (Zhang et al., 2016). However, damage on pods or sink removal may delay leaf abscission (Crafts-Brandner and Egli, 1987; Zhang et al., 2016). Damage by R. pedestris on pods possibly leads to the staygreen of soybeans with a similar mechanism. For example, many digestive enzymes were identified in the transcriptomes and proteomes, and they seemed to be specialized to digest beans (see below). In addition, the bugs often feed on veins of soybean leaves, when they possibly inject effectors that might regulate the soybean development. However, the key effectors remain to be identified.

Male R. pedestris migrate to soybean fields earlier than females during the flowering period, and then they will release pheromone and possibly induce plants to release volatiles for attracting females and nymphs (Endo et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2021). The release of male pheromone is stimulated by feeding (Morishima et al., 2005). So males may excrete more salivary proteins when feeding on newly located plants to overcome a relatively intact immunity. In addition, adults express some genes specifically by salivary glands, as opposed to nymphs (Huang et al., 2021a), which may also contribute to more proteins found in adult saliva than in nymph saliva. However, a strong variance sometimes occurs among replicates, when proteomes in saliva were analyzed in hemipterans, as reported in other papers (Carolan et al., 2009, 2011; Huang et al., 2018).

In the 814 proteins with secretion signals in the male transcriptome, many of them are probably used for digesting proteins and lipids, as also suggested by Huang et al. (2021a), including 112 proteases (peptidases) and 41 lipases (esterases). Since R. pedestris prefers to feed on bean pods in nature, the enzymes are possibly applied to digest proteins and oils in beans. Similar results were obtained from studies on other seed-feeding bugs, as well as predator bugs (Soyelu et al., 2007; Bigham and Hosseininaveh, 2010; Zibaee et al., 2012). Extra-oral digestion seems to be important for many stink bug species (Miles and Taylor, 1994). In laboratory, R. pedestris is normally reared on dry soybean seeds and water supply (Takeshita and Kikuchi, 2017), indicating the extra-oral digestion is a primary process of feeding. In addition, enzymes for sugar digestion were also found, including 6 α-amylases and other glucosidases. The enzymes appeared to be less abundant than proteinases in the salivary glands, as also found in other pod-feeding bugs (Soyelu et al., 2007).

In the male proteome, we found an α-glucosidase (UniProt ID: R4WDP5) and a proteinase (R4WQ74), and the both enzymes are highly expressed in mid-guts (Figure 2A). We also found several cathepsin L enzymes in the saliva of males and females (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3), which are normally expected to occur in lysosomes and never leave the cells. However, the enzymes are often secreted by digestive systems in insects and act as cysteine proteinases (Terra and Ferreira, 2005). The cathepsins L in R. pedestris saliva normally have the secretion signals and are probably used for extra-oral digestion.

Catalases, glutathione peroxidases and peroxiredoxins are oxidoreductases that are well recognized for degrading ROS and maintaining redox homeostasis in the damaged plant cells (Petrova and Smith, 2014; Sharma et al., 2014; Chaudhary et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2020). A catalase (R4WNB5) existed in male saliva, and the enzyme was abundantly expressed in fat bodies (Figure 2). A peroxiredoxin (MW625814) and a glutathione peroxidase (MW625813) were produced by salivary glands in a relatively high amount (Figure 2B). These enzymes may also play an important role in suppressing the first-line defense of plants (Sharma et al., 2014; Dong et al., 2020).

Dehydrogenases may regulate plant defense signaling and detoxify plant toxic compounds (Sharma et al., 2014). For example, glucose dehydrogenases were found in the saliva of some aphid species and the activities of the enzymes were corresponding to their virulence (Carolan et al., 2011; Nicholson et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2014). Several dehydrogenases (R4WD44, R4WCW6, R4WEC6, R4WIH8, and R4WQZ0) were found in the saliva of males and females. In addition, R. pedestris produced two glucose dehydrogenases (MW561670 and MW625827) in a higher amount in salivary glands (Figure 2B). The functions of these enzymes remained to be confirmed in R. pedestris.

Like the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) (Huang et al., 2016), R. pedestris secret leucyl aminopeptidases (R4WCJ9) in saliva (Table 2). The enzymes cleave defense peptides (e.g., hormones and neuropeptides) at N-terminus, especially leucine residues. In addition, an aminopeptidase (MW625818) in transcriptome was also found to be specific in salivary glands and testes of R. pedestris. The enzymes were considered to be essential in defending aphids against plant lectins (Nicholson et al., 2012). Metalloproteases, in contrast, possibly cleave peptides at the C-terminal end (Carolan et al., 2011). In aphids and thrips, they are able to counteract host defenses, by degrading plant defense proteins (Carolan et al., 2009, 2011; Stafford-Banks et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015b). The metalloprotease (MW625833) of R. pedestris appeared to be a Zn-metallocarboxypeptidase, and it was abundantly expressed in salivary glands. These enzymes have a great potential in degrading defense proteins of host plants.

The chitooligosaccharidolytic beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAGase, R4WE69) is a chitinase. The enzyme was highly expressed in salivary glands of R. pedestris and found in male saliva (Tables 1, 2). Plants NAGases act as an antifungal compound by hydrolyzing N-glycans of polysaccharides and glycoproteins (Altmann et al., 1999). Therefore, insects may also use NAGases for inhibiting fungal infection during feeding on plants (Nicholson et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2014). In addition, NAGases in the saliva of sap-sucking herbivores possibly affect plant immunity by the interaction with NAGases of host plants (Nicholson et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2014).

Phloem sieve elements respond to the feeding by piercing-sucking insects by quickly inducing calcium flux which possibly triggers the occlusion of sieve elements and increases the related plant defenses (Will et al., 2009). However, the calcium-binding proteins in saliva possibly reduce the reaction, which guarantees a continuous feeding (Will et al., 2007; Ye et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2021). Indeed, several types of calcium-binding proteins were found in the proteomes and transcriptomes (Tables 1, 2), and one of them (MW625835) had been found to be highly expressed in salivary glands of R. pedestris.

Trialysins have been found in saliva of the hematophagous bug Triatoma infestans (Klug) (Amino et al., 2002). The protein may lyse cells of both animals and microorganisms, indicating it plays an important role in interaction with hosts (Amino et al., 2002). Similarly, two trialysins (A0A1B4X9A5 and A0A1B4X9A9) were found in the saliva of the bean bug (Table 2). And the A0A1B4X9A5 was abundantly produced by salivary glands (Figure 2A).

We also found several mucin-like proteins in the top 1,000 expressed genes of the transcriptomes that were commonly with secretion signals, and most of them were expressed in a relatively higher amount in salivary glands (Table 1 and Figure 2). Similar result was found in N. lugens that secreted mucin-like proteins into both watery and gelling saliva (Huang et al., 2016). One of their functions was to form a developed salivary sheath and increase the adaptation of the brown planthoppers to rice plants (Huang et al., 2017). In the laboratory, we observed many salivary sheaths on soybean seeds after fed by R. pedestris under an optical microscope. The sheaths are normally white tubes with helical curves and with variable lengths. Whether mucin-like proteins also contribute the formation of salivary sheaths in R. pedestris needs further studies.

Two serine protease inhibitors (R4WL96 and R4WCP6) were found in the salvia of males and females. The proteins have been found to be essential in regulation of host defenses by various hematophagous arthropods (Amino et al., 2001; Chmelař et al., 2017; Soares et al., 2018). Both enzymes of R. pedestris were highly expressed in salivary glands (Figure 2), and they are expected to be important in interaction with plant defenses.

The effector proteins of fungal pathogens are often small secreted cysteine-rich proteins (SSCPs) with less than 200 amino acid residues, and have a high cysteine content (>2%) (Stergiopoulos and de Wit, 2009). The strategy might also occur in insects. For example, Nl28 is a species-specific SSCP in N. lugens, which induced cell-death symptoms after the transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana (Rao et al., 2019). The cysteines in the effectors often contribute the formation of disulfide bonds, thereby supporting effectors a specific structure (Saunders et al., 2012). Here, we also found three SSCPs (R4WDU9, R4WQ74, and MW625844) that were greatly expressed in salivary glands or mid-guts of R. pedestris (Figure 2). Therefore, R. pedestris might also use SSCPs to modulate host plant immunity, like fungi and the brown planthoppers.

Insect chemosensory proteins (CSPs) are well known for their functions in olfaction and gustation (Pelosi et al., 2005). However, some papers have found that the proteins are sometimes specifically expressed in salivary glands, and they trigger chlorosis and dwarf phenotypes of N. benthamiana after the transient expressions (Copenhaver et al., 2010; Rao et al., 2019). The MP10, a CSP of the green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Sulz.), activated the jasmonic acid and salicylic acid signaling pathways of N. benthamiana during feeding (Rodriguez et al., 2014; Mugford et al., 2016). Here, two CSPs (A0A2Z4HQ00 and MW625831) were found in saliva or transcriptomes of R. pedestris. However, their expression levels were not biased to a tested tissue (Supplementary Table 4).

Similar with CSPs, odorant binding proteins (OBPs) are also well recognized for the function in sensing odors (Zhu et al., 2019). Here, an OPB (A0A2Z4HQ32) was found in the male saliva (Table 2), and another OPB (MW625837) was largely produced in R. pedestris salivary glands (Figure 2B). How OBPs could act as effectors in herbivores is not yet understood. However, some OBPs are used by mosquitoes to scavenge host amines during feeding, which contributes to anti-inflammatory effect (Calvo et al., 2006, 2009). Since OBPs possibly have ligand-binding hydrophobic channels (Calvo et al., 2009), they may be used by herbivores to bind defense-related molecules of plants.

Carbonic andydrases are zinc metalloenzymes that catalyze the reversible hydration of carbon dioxide to bicarbonate. A carbonic andydrase (MW625839) was specifically expressed in salivary glands of R. pedestris (Figure 2B). Carbonic andydrases were also found in the watery saliva of a leafhopper and a planthopper species (Hattori et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016). Silencing the gene resulted in lethality of N. lugens (Huang et al., 2016). How the enzymes help hemipterans feed on plants is not clear. They may play a protective role in the elevated CO2 concentration during feeding (Huang et al., 2016).

Transcriptome analysis indicates that salivary glands of R. pedestris possibly produce a rich repertoire of proteins, in which many of them are possibly used to digest proteins and oils in beans. In addition, rich proteins were found in their saliva, and a high proportion of the proteins are not yet annotated, indicating knowledge on the salivary proteins of the pest is very limited. Therefore, the datasets reported here represent an important first step in identifying effectors in R. pedestris. In addition, a few elicitors of moth species are relatively small molecules that are not complete proteins, such as volicitin and inceptin peptides (Alborn et al., 1997; Steinbrenner et al., 2020). Those elicitors might also exist in heteropteran species, in which they have been ignored so far. The different kinds of elicitors and effector proteins are likely to work together in facilitating the feeding success of R. pedestris on soybeans.

The raw datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repositories and accession numbers can be found below: NCBI SRA database (accession: PRJNA690963) and ProteomeXchange (accession: PXD027846).

HX, RJ, and JL designed the experiment. WF, XL, CR, and YW performed the experiment. HX, WF, and XB analyzed the data and made the figures and tables. HX wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

The research was funded by the Anhui Provincial Key Research and Development Program (202104a06020035) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (JCQY201904).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We would like to thank Baoping Li for the improvement of the writing. We also appreciate the suggestions by Haijian Huang, Bingyao Wang, and Jiarong Cui on the experimental design and data analyses. Feng Zhang and his team helped us take photos of R. pedestris. Our colleagues helped with the insect rearing.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2021.760368/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Tables 1–4 and Figures | The general information and annotations of the transcriptomes; the proteomes of females and nymphs.

Supplementary Table 5 | Salivary proteins found in this paper were compared to that in Huang et al. (2021a).

Supplementary File 1 | The list of primers used in RT-qPCR analyses.

Alborn, H., Turlings, T., Jones, T., Stenhagen, G., Loughrin, J., and Tumlinson, J. (1997). An elicitor of plant volatiles from beet armyworm oral secretion. Science 276, 945–949. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5314.945

Altmann, F., Staudacher, E., Wilson, I. B., and März, L. (1999). Insect cells as hosts for the expression of recombinant glycoproteins. Glycotechnology 16, 109–123.

Amino, R., Martins, R. M., Procopio, J., Hirata, I. Y., Juliano, M. A., and Schenkman, S. (2002). Trialysin, a novel pore-forming protein from saliva of hematophagous insects activated by limited proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6207–6213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m109874200

Amino, R., Tanaka, A. S., and Schenkman, S. (2001). Triapsin, an unusual activatable serine protease from the saliva of the hematophagous vector of Chagas’ disease Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 31, 465–472. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(00)00151-x

Armenteros, J. J. A., Tsirigos, K. D., Sønderby, C. K., Petersen, T. N., Winther, O., Brunak, S., et al. (2019). SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 420–423. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z

Atamian, H. S., Chaudhary, R., Dal Cin, V., Bao, E., Girke, T., and Kaloshian, I. (2013). In planta expression or delivery of potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae effectors Me10 and Me23 enhances aphid fecundity. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 26, 67–74. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-06-12-0144-fi

Bigham, M., and Hosseininaveh, V. (2010). Digestive proteolytic activity in the pistachio green stink bug, Brachynema germari Kolenati (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 13, 221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.aspen.2010.03.004

Boulain, H., Legeai, F., Guy, E., Morliere, S., Douglas, N. E., Oh, J., et al. (2018). Fast evolution and lineage-specific gene family expansions of aphid salivary effectors driven by interactions with host-plants. Genome Biol. Evol. 10, 1554–1572. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy097

Calvo, E., Mans, B. J., Andersen, J. F., and Ribeiro, J. M. (2006). Function and evolution of a mosquito salivary protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1935–1942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m510359200

Calvo, E., Mans, B. J., Ribeiro, J. M., and Andersen, J. F. (2009). Multifunctionality and mechanism of ligand binding in a mosquito antiinflammatory protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3728–3733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813190106

Carolan, J. C., Caragea, D., Reardon, K. T., Mutti, N. S., Dittmer, N., Pappan, K., et al. (2011). Predicted effector molecules in the salivary secretome of the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum): a dual transcriptomic/proteomic approach. J. Proteome Res. 10, 1505–1518. doi: 10.1021/pr100881q

Carolan, J. C., Fitzroy, C. I. J., Ashton, P. D., Douglas, A. E., and Wilkinson, T. L. (2009). The secreted salivary proteome of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum characterised by mass spectrometry. Proteomics 9, 2457–2467.

Chaudhary, R., Atamian, H. S., Shen, Z. X., Briggs, S. P., and Kaloshian, I. (2015). Potato aphid salivary proteome: enhanced salivation using resorcinol and identification of aphid phosphoproteins. J. Proteome Res. 14, 1762–1778. doi: 10.1021/pr501128k

Chaudhary, R., Atamian, H. S., Shen, Z., Briggs, S. P., and Kaloshian, I. (2014). GroEL from the endosymbiont Buchnera aphidicola betrays the aphid by triggering plant defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 8919–8924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407687111

Cherqui, A., and Tjallingii, W. F. (2000). Salivary proteins of aphids, a pilot study on identification, separation and immunolocalisation. J. Insect Physiol. 46, 1177–1186. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(00)00037-8

Chmelař, J., Kotál, J., Langhansová, H., and Kotsyfakis, M. (2017). Protease inhibitors in tick saliva: the role of serpins and cystatins in tick-host-pathogen interaction. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7:216. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00216

Copenhaver, G. P., Bos, J. I. B., Prince, D., Pitino, M., Maffei, M. E., Win, J., et al. (2010). A functional genomics approach identifies candidate effectors from the aphid species Myzus persicae (Green Peach Aphid). PLoS Genet. 6:e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001216

Coudron, T. A., Brandt, S. L., and Hunter, W. B. (2007). Molecular profiling of proteolytic and lectin transcripts in Homalodisca vitripennis (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha: Cicadellidae) feeding on sunflower and cowpea. Arch. Insect Biochem. 66, 76–88. doi: 10.1002/arch.20200

Crafts-Brandner, S. J., and Egli, D. B. (1987). Sink removal and leaf senescence in soybean: cultivar effects. Plant Physiol. 85, 662–666. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.3.662

DeLay, B., Mamidala, P., Wijeratne, A., Wijeratne, S., Mittapalli, O., Wang, J., et al. (2012). Transcriptome analysis of the salivary glands of potato leafhopper, Empoasca fabae. J. Insect Physiol. 58, 1626–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.10.002

Dong, Y., Jing, M., Shen, D., Wang, C., Zhang, M., Liang, D., et al. (2020). The mirid bug Apolygus lucorum deploys a glutathione peroxidase as a candidate effector to enhance plant susceptibility. J. Exp. Biol. 71, 2701–2712. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa015

Dou, D., and Zhou, J.-M. (2012). Phytopathogen effectors subverting host immunity: different foes, similar battleground. Cell Host Microbe 12, 484–495. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.003

Elzinga, D. A., De Vos, M., and Jander, G. (2014). Suppression of plant defenses by a Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) salivary effector protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27, 747–756. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-01-14-0018-r

Endo, N., Wada, T., and Sasaki, R. (2011). Seasonal synchrony between pheromone trap catches of the bean bug, Riptortus pedestris (Heteroptera: Alydidae) and the timing of invasion of soybean fields. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 46, 477–482. doi: 10.1007/s13355-011-0065-7

Francischetti, I. M., Lopes, A. H., Dias, F. A., Pham, V. M., and Ribeiro, J. M. (2007). An insight into the sialotranscriptome of the seed-feeding bug, Oncopeltus fasciatus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37, 903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.04.007

Fu, J., Shi, Y., Wang, L., Zhang, H., Li, J., Fang, J., et al. (2021). Planthopper-secreted salivary disulfide isomerase activates immune responses in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 11:622513. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.622513

Guo, H., Zhang, Y., Tong, J., Ge, P., Wang, Q., Zhao, Z., et al. (2020). An aphid-secreted salivary protease activates plant defense in phloem. Curr. Biol. 30, 4826–4836.e.

Hattori, M., Komatsu, S., Noda, H., and Matsumoto, Y. (2015). Proteome analysis of watery saliva secreted by green rice leafhopper, Nephotettix cincticeps. PLoS One 10:e0123671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123671

Hogenhout, S. A., and Bos, J. I. (2011). Effector proteins that modulate plant–insect interactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14, 422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.05.003

Hogenhout, S. A., Van Der Hoorn, R. A., Terauchi, R., and Kamoun, S. (2009). Emerging concepts in effector biology of plant-associated organisms. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22, 115–122. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-22-2-0115

Huang, H. J., Liu, C. W., Huang, X. H., Zhou, X., Zhuo, J. C., Zhang, C. X., et al. (2016). Screening and functional analyses of Nilaparvata lugens salivary proteome. J. Proteome Res. 15, 1883–1896. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00086

Huang, H. J., Liu, C. W., Xu, H. J., Bao, Y. Y., and Zhang, C. X. (2017). Mucin-like protein, a saliva component involved in brown planthopper virulence and host adaptation. J. Insect Physiol. 98, 223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2017.01.012

Huang, H. J., Lu, J. B., Li, Q., Bao, Y. Y., and Zhang, C. X. (2018). Combined transcriptomic/proteomic analysis of salivary gland and secreted saliva in three planthopper species. J. Proteomics 172, 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.11.003

Huang, H. J., Zhang, C. X., and Hong, X. Y. (2019c). How does saliva function in planthopper–host interactions? Arch. Insect Biochem. 100:e21537.

Huang, H. J., Cui, J. R., Xia, X., Chen, J., Ye, Y. X., Zhang, C. X., et al. (2019b). Salivary DNase II from Laodelphax striatellus acts as an effector that suppresses plant defence. New Phytol. 224, 860–874. doi: 10.1111/nph.15792

Huang, H. J., Cui, J. R., Chen, L., Zhu, Y. X., and Hong, X. Y. (2019a). Identification of saliva proteins of the spider mite Tetranychus evansi by transcriptome and LC–MS/MS analyses. Proteomics 19:1800302. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201800302

Huang, H.-J., Ye, Y.-X., Ye, Z.-X., Yan, X.-T., Wang, X., Wei, Z.-Y., et al. (2021b). Chromosome-level genome assembly of the bean bug Riptortus pedestris. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 2423–2436. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13434

Huang, H.-J., Yan, X.-T., Wei, Z.-Y., Wang, Y.-Z., Chen, J.-P., Li, J.-M., et al. (2021a). Identification of Riptortus pedestris salivary proteins and their roles in inducing plant defenses. Biology 10:753. doi: 10.3390/biology10080753

Ji, R., Yu, H., Fu, Q., Chen, H., Ye, W., Li, S., et al. (2013). Comparative transcriptome analysis of salivary glands of two populations of rice brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, that differ in virulence. PLoS One 8:e79612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079612

Kim, H. S., Lee, B. Y., Won, E. J., Han, J., Hwang, D. S., Park, H. G., et al. (2015). Identification of xenobiotic biodegradation and metabolism-related genes in the copepod Tigriopus japonicus whole transcriptome analysis. Mar. Genomics 24(Pt 3), 207–208. doi: 10.1016/j.margen.2015.05.011

Krogh, A., Larsson, B., Von Heijne, G., and Sonnhammer, E. L. (2001). Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315

Lee, S. J., Yang, Y. T., Kim, S., Lee, M. R., Kim, J. C., Park, S. E., et al. (2019). Transcriptional response of bean bug (Riptortus pedestris) upon infection with entomopathogenic fungus, Beauveria bassiana JEF-007. Pest Manag. Sci. 75, 333–345. doi: 10.1002/ps.5117

Li, K., Zhang, X., Guo, J., Penn, H., Wu, T., Li, L., et al. (2019). Feeding of Riptortus pedestris on soybean plants, the primary cause of soybean staygreen syndrome in the Huang-Huai-Hai river basin. Crop J. 7, 360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2018.07.008

Li, R. Q., Li, Y. R., Kristiansen, K., and Wang, J. (2008). SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics 24, 713–714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025

Li, W., Zhao, X., Yuan, W., and Wu, K. (2017). Activities of digestive enzymes in the omnivorous pest Apolygus lucorum (Hemiptera: Miridae). J. Econ. Entomol. 110, 101–110. doi: 10.1093/jee/tow263

Lü, J., Yang, C., Zhang, Y., and Pan, H. (2018). Selection of reference genes for the normalization of RT-qPCR data in gene expression studies in insects: a systematic review. Front. Physiol. 9:1560. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01560

Matsumoto, Y., and Hattori, M. (2018). The green rice leafhopper, Nephotettix cincticeps (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae), salivary protein NcSP75 is a key effector for successful phloem ingestion. PLoS One 13:e0202492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202492

Miao, Y.-T., Deng, Y., Jia, H.-K., Liu, Y.-D., and Hou, M.-L. (2018). Proteomic analysis of watery saliva secreted by white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera. PLoS One 13:e0193831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193831

Miles, P., and Taylor, G. (1994). ‘Osmotic pump’ feeding by coreids. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 73, 163–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1994.tb01852.x

Morishima, M., Tabuchi, K., Ito, K., Mizutani, N., and Moriya, S. (2005). Effect of feeding on the attractiveness of Riptortus clavatus (Thunberg) (Heteroptera: Alydidae) males to conspecific individuals. Jpn. J. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 49, 262–265. doi: 10.1303/jjaez.2005.262

Mugford, S. T., Barclay, E., Drurey, C., Findlay, K. C., and Hogenhout, S. A. (2016). An immuno-suppressive aphid saliva protein is delivered into the cytosol of plant mesophyll cells during feeding. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 29, 854–861. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-08-16-0168-r

Nicholson, S. J., Hartson, S. D., and Puterka, G. J. (2012). Proteomic analysis of secreted saliva from Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia Kurd.) biotypes that differ in virulence to wheat. J. Proteomics 75, 2252–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.01.031

Nielsen, H. (2017). “Predicting secretory proteins with SignalP,” in Protein Function Prediction: Methods and Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology, ed. D. Kihara (Berlin: Springer), 59–73. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7015-5_6

Pelosi, P., Calvello, M., and Ban, L. (2005). Diversity of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in insects. Chem. Senses 30, i291–i292.

Pertea, G., Huang, X. Q., Liang, F., Antonescu, V., Sultana, R., Karamycheva, S., et al. (2003). TIGR gene indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics 19, 651–652. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg034

Petrova, A., and Smith, C. M. (2014). Immunodetection of a brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stal) salivary catalase-like protein into tissues of rice, Oryza sativa. Insect Mol. Biol. 23, 13–25. doi: 10.1111/imb.12058

Rao, W. W., Zheng, X. H., Liu, B. F., Guo, Q., Guo, J. P., Wu, Y., et al. (2019). Secretome analysis and in planta expression of salivary proteins identify candidate effectors from the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 32, 227–239. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-05-18-0122-r

Rao, X., Huang, X., Zhou, Z., and Lin, X. (2013). An improvement of the 2^(-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat. Bioinforma. Biomath. 3, 71–85.

Rieu, I., and Powers, S. J. (2009). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR: design, calculations, and statistics. Plant Cell 21, 1031–1033. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.066001

Rodriguez, P. A., Stam, R., Warbroek, T., and Bos, J. I. (2014). Mp10 and Mp42 from the aphid species Myzus persicae trigger plant defenses in Nicotiana benthamiana through different activities. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27, 30–39. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-05-13-0156-r

Saunders, D. G., Win, J., Cano, L. M., Szabo, L. J., Kamoun, S., and Raffaele, S. (2012). Using hierarchical clustering of secreted protein families to classify and rank candidate effectors of rust fungi. PLoS One 7:e29847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029847

Sharma, A., Khan, A. N., Subrahmanyam, S., Raman, A., Taylor, G. S., and Fletcher, M. J. (2014). Salivary proteins of plant-feeding hemipteroids-implication in phytophagy. Bull. Entomol. Res. 104, 117–136. doi: 10.1017/s0007485313000618

Soares, T. S., Rodriguez Gonzalez, B. L., Torquato, R. J. S., Lemos, F. J. A., Costa-Da-Silva, A. L., Capurro Guimarães, M. D. L., et al. (2018). Functional characterization of a serine protease inhibitor modulated in the infection of the Aedes aegypti with dengue virus. Biochimie 144, 160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.11.005

Soyelu, O., Akingbohungbe, A., and Okonji, R. (2007). Salivary glands and their digestive enzymes in pod-sucking bugs (Hemiptera: Coreoidea) associated with cowpea Vigna unguiculata ssp. unguiculata in Nigeria. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 27, 40–47. doi: 10.1017/s1742758407744466

Stafford-Banks, C. A., Rotenberg, D., Johnson, B. R., Whitfield, A. E., and Ullman, D. E. (2014). Analysis of the salivary gland transcriptome of Frankliniella occidentalis. PLoS One 9:e94447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094447

Steinbrenner, A. D., Muñoz-Amatriaín, M., Chaparro, A. F., Aguilar-Venegas, J. M., Lo, S., Okuda, S., et al. (2020). A receptor-like protein mediates plant immune responses to herbivore-associated molecular patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 31510–31518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2018415117

Stergiopoulos, I., and de Wit, P. J. (2009). Fungal effector proteins. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 47, 233–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.112408.132637

Su, Y. L., Li, J. M., Li, M., Luan, J. B., Ye, X. D., Wang, X. W., et al. (2012). Transcriptomic analysis of the salivary glands of an invasive whitefly. PLoS One 7:e39303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039303

Takeshita, K., and Kikuchi, Y. (2017). Riptortus pedestris and Burkholderia symbiont: an ideal model system for insect–microbe symbiotic associations. Res. Microbiol. 168, 175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.11.005

Tan, X., Xu, X., Gao, Y., Yang, Q., Zhu, Y., Wang, J., et al. (2016). Levels of salivary enzymes of Apolygus lucorum (Hemiptera: Miridae), from 1st instar nymph to adult, and their potential relation to bug feeding. PLoS One 11:e0168848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168848

Taylor, G. S., and Miles, P. W. (1994). Composition and variability of the saliva of coreids in relation to phytoxicoses and other aspects of the salivary physiology of phytophagous Heteroptera. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 73, 265–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1994.tb01864.x

Terra, W. R., and Ferreira, C. (2005). “Biochemistry of digestion,” in Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science, ed. L. I. Gilbert (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 171–224.

Tian, T., Ji, R., Fu, J., Li, J., Wang, L., Zhang, H., et al. (2021). A salivary calcium-binding protein from Laodelphax striatellus acts as an effector that suppresses defense in rice. Pest Manag. Sci. 77, 2272–2281. doi: 10.1002/ps.6252

Wang, W., Luo, L., Lu, H., Chen, S. L., Kang, L., and Cui, F. (2015b). Angiotensin-converting enzymes modulate aphid-plant interactions. Sci. Rep. 5:8885.

Wang, W., Dai, H. E., Zhang, Y., Chandrasekar, R., Luo, L., Hiromasa, Y., et al. (2015a). Armet is an effector protein mediating aphid-plant interactions. FASEB J. 29, 2032–2045. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-266023

Will, T., Kornemann, S. R., Furch, A. C., Tjallingii, W. F., and Van Bel, A. J. (2009). Aphid watery saliva counteracts sieve-tube occlusion: a universal phenomenon? J. Exp. Biol. 212, 3305–3312. doi: 10.1242/jeb.028514

Will, T., Steckbauer, K., Hardt, M., and Bel, A. J. E. V. (2012). Aphid gel saliva: sheath structure, protein composition and secretory dependence on stylet-tip milieu. PLoS One 7:e46903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046903

Will, T., Tjallingii, W. F., Thönnessen, A., and Van Bel, A. J. (2007). Molecular sabotage of plant defense by aphid saliva. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10536–10541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703535104

Xu, H. X., Qian, L. X., Wang, X. W., Shao, R. X., Hong, Y., Liu, S. S., et al. (2019). A salivary effector enables whitefly to feed on host plants by eliciting salicylic acid-signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 490–495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714990116

Xu, H., Zhao, J., Li, F., Yan, Q., Meng, L., and Li, B. (2021). Chemical polymorphism regulates the attractiveness to nymphs in the bean bug Riptortus pedestris. J. Pest Sci. 94, 463–472. doi: 10.1007/s10340-020-01268-w

Ye, W. F., Yu, H. X., Jian, Y. K., Zeng, J. M., Ji, R., Chen, H. D., et al. (2017). A salivary EF-hand calcium-binding protein of the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens functions as an effector for defense responses in rice. Sci. Rep. 7:40498.

Zhang, W., Liu, B., Lu, Y., and Liang, G. (2017). Functional analysis of two polygalacturonase genes in Apolygus lucorum associated with eliciting plant injury using RNA interference. Arch. Insect Biochem. 94:e21382. doi: 10.1002/arch.21382

Zhang, X., Wang, M., Wu, T., Wu, C., Jiang, B., Guo, C., et al. (2016). Physiological and molecular studies of staygreen caused by pod removal and seed injury in soybean. Crop J. 4, 435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2016.04.002

Zhu, G.-H., Zheng, M.-Y., Sun, J.-B., Khuhro, S. A., Yan, Q., Huang, Y., et al. (2019). CRISPR/Cas9 mediated gene knockout reveals a more important role of PBP1 than PBP2 in the perception of female sex pheromone components in Spodoptera litura. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 115:103244. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.103244

Zhu, Y.-C., Yao, J., and Luttrell, R. (2016). Identification of genes potentially responsible for extra-oral digestion and overcoming plant defense from salivary glands of the tarnished plant bug (Hemiptera: Miridae) using cDNA sequencing. J. Insect Sci. 16:60. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iew041

Keywords: plant-insect interaction, stink bug, legume, elicitor, plant immunity

Citation: Fu W, Liu X, Rao C, Ji R, Bing X, Li J, Wang Y and Xu H (2021) Screening Candidate Effectors of the Bean Bug Riptortus pedestris by Proteomic and Transcriptomic Analyses. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9:760368. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.760368

Received: 18 August 2021; Accepted: 11 October 2021;

Published: 01 November 2021.

Edited by:

Swayamjit Ray, Cornell University, United StatesReviewed by:

Takeshi Suzuki, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, JapanCopyright © 2021 Fu, Liu, Rao, Ji, Bing, Li, Wang and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hao Xu, aGFveHVAbmphdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.