- 1Institute of Forest Sciences, Chair of Forest History, Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

- 2Amt für Archäologie, Kanton Thurgau, Frauenfeld, Switzerland

- 3Institute of Forest Sciences, Chair of Forest Growth and Dendroecology, Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

The scientific field of forest history studies the development of woodlands and their interrelationship with past human societies. During the last decades, the subject has experienced a constant decrease of importance, reflected in the loss of representation in most universities. After 200 years of existence, an insufficient theoretical basis and the prevalence of bibliographical and institutional studies on post-medieval periods have isolated the field and hindered interdisciplinary exchange. Here we present possible new perspectives, proposing wider methodological, chronological, thematic, and geographical areas of focus. This paper summarizes the development of the field over time and recommends content enhancement, providing a specific example of application from Roman France. Furthermore, we introduce a topical definition of forest history. Following the lead of other fields of the humanities and environmental sciences focussing on the past, forest history has to adapt to using other available archives in addition to historical written sources. In particular, historical and archeological timber as well as pollen are essential sources for the study of past forests. Research into forest history can substantially add to our understanding of relevant issues like societal responses to climate change and resource scarcity in the past and contribute to future scenarios of sustainability.

Introduction

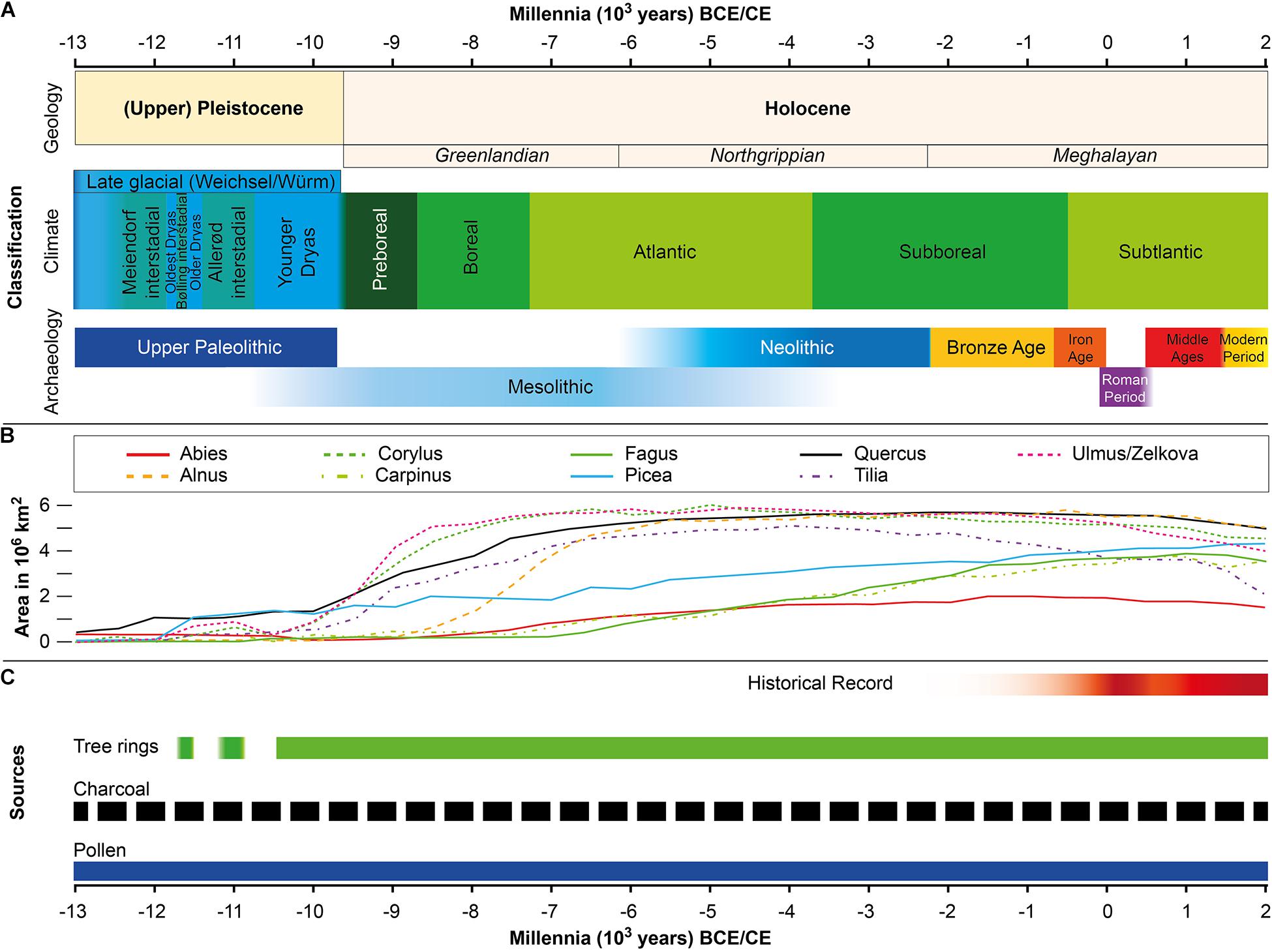

After the Last Glacial Maximum (∼21 ky ago) and from the start of the Holocene (ca. 11.7 ky ago; Figure 1A), forests recolonized large parts of Europe (Figure 1; Giesecke et al., 2017; Marquer et al., 2017). Forests provided the basis for the development of civilizations and have remained a key factor for human societies until today (Küster, 1998, 2010). Throughout the Holocene, forests had to serve multiple purposes for human societies, providing food and raw material, particularly wood, for construction and tools. Furthermore, wood was one of the most important sources of energy for domestic and productive processes until the nineteenth century (Schmidt, 2009; Mosandl et al., 2010). Growing human impact on natural forests evolved with the development of sedentism (Dow and Reed, 2015) and agriculture (Bogucki, 1996; Pryor, 2003; Dow et al., 2005; Pinhasi et al., 2005), when human societies started reaching out for wood resources, settlement areas and farmland. In Europe, this process started during the Early Neolithic period, around 6000 BCE, associated with the Starèevo culture in south-eastern Europe and the Cardial culture in the Mediterranean (Gyulai, 2007; Shennan, 2018) and expanded to areas north of the Alps during the 6th millennium BCE, manifested in the Linear Pottery culture (Tegel et al., 2012; Lipson et al., 2017). The anthropogenic influence has been shaping cultural landscapes ever since (Bradshaw, 2004; Krzywinski et al., 2009; Mercuri et al., 2015).

Figure 1. Chronological overview for possible forest history research in Europe. (A) Classification of Geology (Cohen et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2018), Climatology (Litt et al., 2001, 2007) and Archeology in central Europe (Cunliffe, 2008; Scholkmann et al., 2016). (B) Post-glacial changes of occurrence for the most common European tree taxa, established from pollen records (data from Giesecke et al., 2017). (C) Chronological range of available sources: Historical record (red), tree rings (green), charcoal (black) and pollen (blue).

The invention of metallurgy, most importantly of bronze, starting in Eurasia during the 5th millennium BCE (Radivojević et al., 2013) and iron, developed around 2000 BCE in Anatolia (Souckova-Siegelová, 2001; Akanuma, 2008) and spread to large parts of Eurasia during the early 1st millennium BCE (Pigott, 1999), significantly increasing the demand for wood for charcoal production. The exploitation of woodland resources by human societies has reshaped environments, and vice versa, as environmental conditions have had impacts on economies and societies (Ljungqvist et al., 2021). Woodland areas were cleared in times of prosperity and partially recolonized by forests during times of decline following detrimental climatic or demographic developments (Chew, 2001; Küster, 2010; Ljungqvist et al., 2018). Therefore, forest and human history are strongly interconnected. Over time, human impact intensified with growing populations, reaching a first peak in large parts of Europe during the High Medieval Period (ca. 1000–1300 CE) (Bartlett, 1993). In the following centuries, deforestation increased in large areas due to building activity and the development of proto-industrial sectors, e.g., glass and charcoal production, mining and smelting. Rising economic concerns over wood supplies, beginning in the 18th century, led to the development of modern forestry (Schmidt, 1998, 2002, cf. Hölzl, 2010; Radkau, 2012).

Traditionally, studies of forest history work mainly with historical records and focus on the last few centuries (e.g., Franz, 2020), which is a strong limitation to the most recent periods of human history (Figure 1C). In this paper, we address the potential of dendroarcheological analyses as a source for forest history studies and furthermore, discuss possible interdisciplinary concepts. The combination of (dendro) archeological and palynological data enhances our understanding of demographic changes, settlement dynamics and general vegetation history, providing a wider temporal scope for future studies of forest history.

Development of the Field

In Europe, interest in the historical development of forests began with the progression of forest sciences, primarily in Germany, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Consequently, early forest history studies were predominantly published in German-speaking countries (e.g., Stisser, 1737; Walther, 1816; Behlen, 1831; Pfeil, 1839; Bernhardt, 1872, 1874, 1875; Roth, 1879; Meister, 1883; Schwappach, 1886; Seidenstricker, 1886), but also in France (Baudrillart, 1824) and Italy (Di Bérgener, 1859). The Anglo-American research advanced with the foundation of the Forest History Society (FHS) in 1946 (originally: Forest Products History Foundation, cf. Anderson, 2018).

The forester and conservationist Felix von Hornstein suggested a theoretical and methodological separation between the history of forestry (German: “Forstgeschichte”) and the history of human-nature relationships (German: “Waldgeschichte”) (von Hornstein, 1951). The International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO) Forest History Group, formed in the early 1960s, provided different definitions for the concepts of forest history sensu stricto, i.e., the history of forestry, and sensu lato, i.e., a synthesis with the history of (natural) forests and human impact (IUFRO, 1973). The forest scientist Kurt Mantel (1990) excluded pre-historic periods from forest history (German: “Forstgeschichte”), whereas Karl Hasel defined it as the study of the changing relationship between forests and human societies over centuries and millennia, yet distinguishing it from history of natural forests (German: “Waldgeschichte”), which is mainly studied with palynological methods (Hasel and Schwartz, 2006).

These definitions of forest history are contradictory, regarding methodological and chronological aspects. As they were all published in German, they were not adopted by the international research community. In the German-speaking countries, however, an increasing separation took place from the 1950s between studies on pre-historic forests (cf. German: “Waldgeschichte”), performed by experts of vegetation history (Firbas, 1949, 1952; von Hornstein, 1951, 1958; Lang, 1994), and historic forests (cf. German: “Forstgeschichte”), studied by historians (Hilf, 1938; Hausrath, 1982; Mantel, 1990). Vegetation history progressed to a modern field of science, including Holocene human impacts (e.g., Berglund, 2003; Marquer et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2018), whereas “Forstgeschichte” mostly remained within the limits of historiography (e.g., Franz, 2020, cf. Furay and Salevouris, 2017).

Outside Germany, forest history obtained new impetus in the late 1970s and 1980s when it became the interest of geographers and ecologists (e.g., Bertrand, 1975; Rackham, 1976). A first international congress of forest history was held in 1979 in Nancy, France (Schuler, 1982). In 1981 the “Groupe d’Histoire des Forêts Françaises” was founded and, in the following years, aimed for a multidisciplinary approach, combining historical, anthropological and sociological research with ecological and economic aspects (Corvol-Dessert, 2003).

Until the end of the twentieth century, various studies on forest history have been published, analyzing written and iconographic sources and mostly emphasizing on late to post-medieval periods (e.g., Kuonen, 1993; Schmidt, 1998, cf. Rubner, 2002). Earlier periods and millennia-long developments, however, have mainly been the topic of archeological and environmental science studies (Bennett et al., 1990; Bradshaw and Mitchell, 1999; Vera, 2000; Behre, 2002; Bradshaw et al., 2003; Kramer et al., 2003; Rackham, 2003; Whitehouse and Smith, 2004; Lindbladh et al., 2013; Stephens et al., 2019).

At the turn of the millennium, several authors critically addressed the position of traditional forest history and provided suggestions for a new orientation in the twenty-first century, e.g., the adaption of methodological innovations from cultural history research, social sciences, historical ecology, the inclusion of natural sciences or a shift toward a general environmental history (Seling, 1998; Agnoletti, 2000, 2006; Schmidt, 2000; Bürgi et al., 2001; Hürlimann, 2003; Johann, 2006). Several new national publications have come out in recent years (e.g., Agnoletti, 2018; Bonan, 2019; Gallé and Quéruel, 2019; Huth, 2019; Franz, 2020). International publications on the field have been issued in different journals by the FHS, i.e., “Forest History” (1957–1974), the “Journal of Forest History” (1975–1989), and “Forest and Conservation History” (1990–1995), before merging with the journal “Environmental History Review”, published by the American Society of Environmental History, in 1996 (Rothman, 1996). Since then, the quarterly journal “Environmental History” has been co-published.1 Alongside, the FHS has published the monthly magazine “Forest History Today” since 1995.

Nevertheless, the loss of representation of the scientific field in most universities or their integration into institutes of forest policy, especially in the German speaking countries, reflect a constant decrease in the importance of traditional forest history during the last decades (Johann, 2006). Recent advances of environmental history research and particularly dendroarcheological and palynological studies, call for fundamental reconsiderations of theories and methods of traditional forest history.

A Topical Definition of “Forest History”

As demonstrated above, previous definitions of forest history are contradictory and need further consideration. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines land areas larger than 0.5 ha with more than 10% crown cover of trees, which are higher than 5 m as “forests” (FAO, 1999). Some traditionally managed or treeline stands might not fulfill the FAO criteria for forests but can still be research subjects of forest history. Hence, a topical definition for the field must consider all types of woodlands.

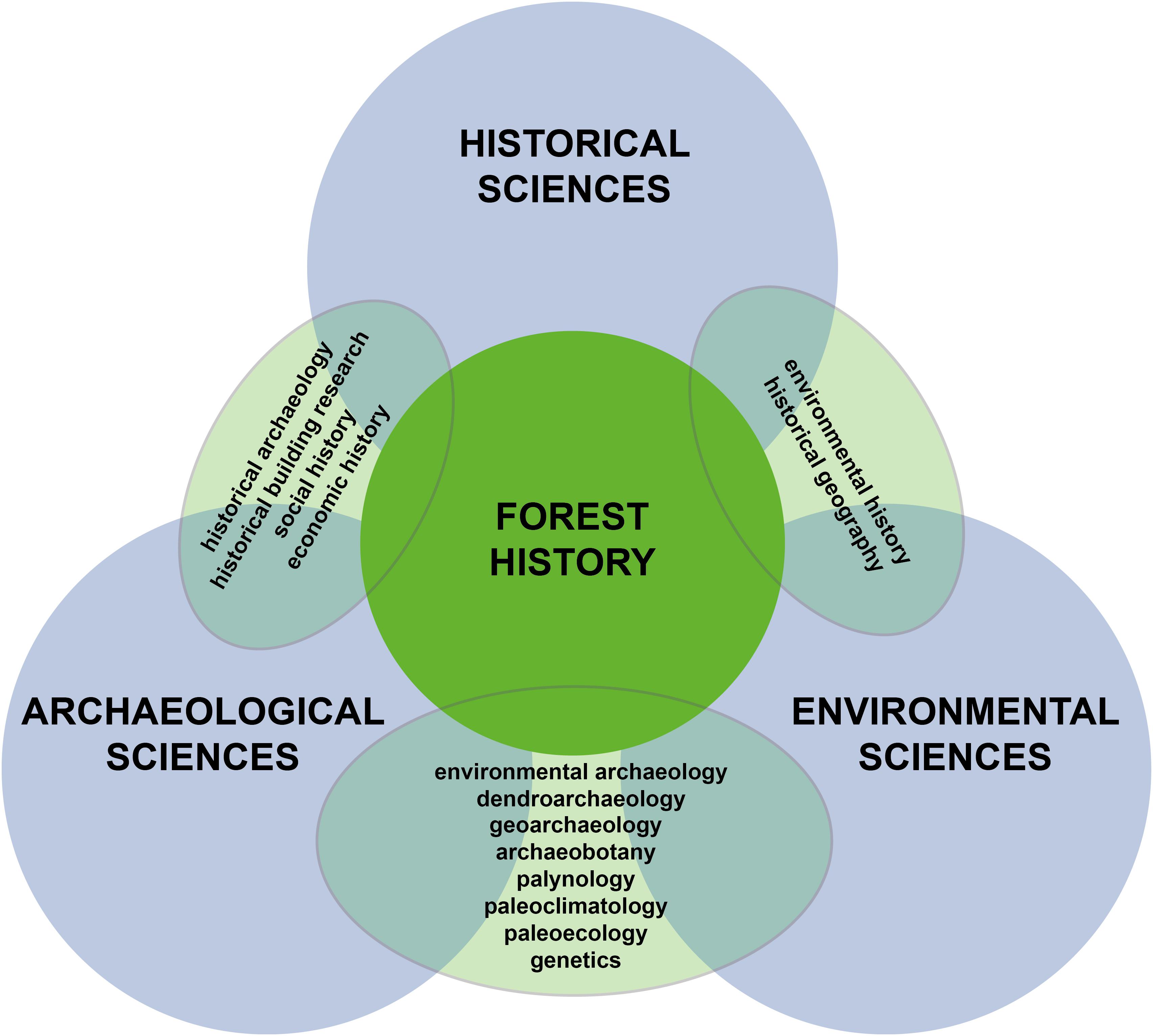

Therefore, we propose a general definition for the field of forest history as “the investigation of past woodlands and past human-woodland-interaction,” combining research into both natural forests and anthropogenic influences.

Our new definition aims at the inclusion of methods from archeological and environmental sciences (Figure 2). Furthermore, it repeals the temporal limitations of earlier definitions. A prevailing focus on the Holocene is acknowledged, as significant human impact on forests is restricted to the post-glacial period (Figure 1A). However, some sedentary societies had developed long before the invention of agriculture, influencing their local environment more strongly than mobile groups (Dow and Reed, 2015; Arranz-Otaegui et al., 2016; Alenius et al., 2020). Accordingly, the new definition is deliberately not restricted to the Holocene.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of modern forest history (green), positioned between the scientific fields of history, archeology and environmental sciences (light blue). A selection of overlapping sub-fields is illustrated in light green.

Reading Forest History From Dendroarcheological Sources

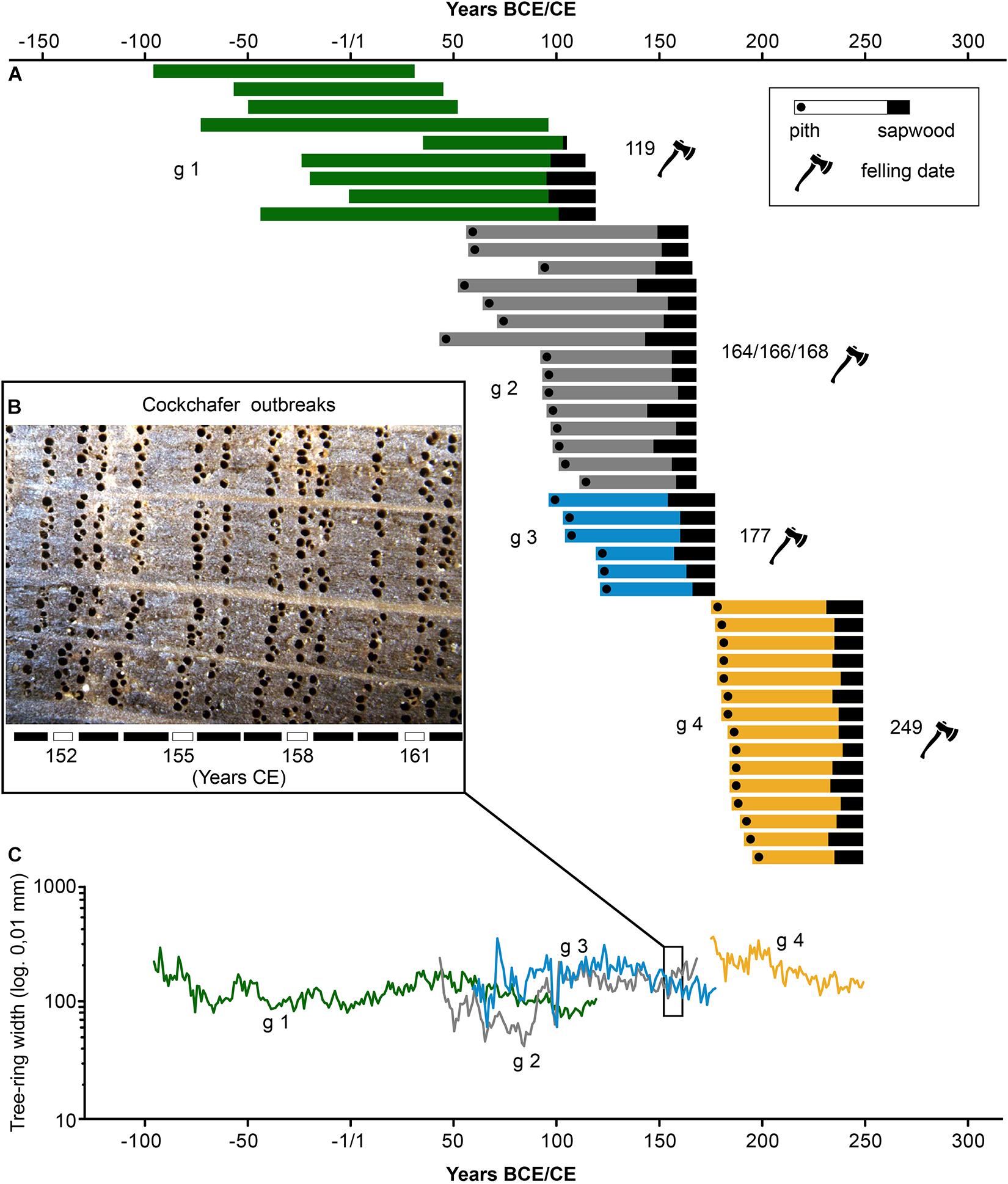

A case study from Roman Gaul illustrates the potential of dendroarcheology for forest history research: The city of Divodurum (Mediomatricorum, or Divodurum of the Mediomatrici), today’s Metz in north-eastern France, was one of the largest cities in Roman Gaul with about 40,000 inhabitants (Vigneron, 1986). Archeological excavations on Boulevard Paixhans in 1995 discovered the remains of wooden Roman quay structures (Rohmer, 1996, 1999). Dendrochronological analyses of 53 oak piles specified the structures’ age and allowed the distinction of four construction phases between 119 and 249 CE (Figure 3A; Rohmer and Tegel, 1999). The oldest phase (g 1) exclusively used split wood for the piles felled in 119 CE, whereas roundwood was utilized during the other phases (g 2–g 4), dating between 164 and 249 CE. The trees used as piles of the youngest construction phase were approximately 70 years old, while the trees from older phases show different age distribution, mostly between 80 and 120, with some individuals up to more than 170 years. The temporal proximity of the felling dates for construction g 3 and the initial growth onset of trees from g 4 suggests the successive use of a nearby woodland (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Dendroarcheological case study example Metz, Boulevard Paixhans (Rohmer and Tegel, 1999). (A) Bar graph of single trees grouped by construction phases (g 1–g 4). Presence of pith and sapwood is indicated (black). (B) Detail photography of characteristic growth pattern caused by 3-year cyclic cockchafer outbreaks. Below: Years of outbreaks highlighted. (C) Mean tree-ring width curves for each construction phase (g 1–g 4). Note the onset of g 4 right after the felling of g 3.

All piles were anatomically identified as oak (Quercus spp.) and when synchronized, generate a mean chronology of 346 years (Rohmer and Tegel, 1999), permitting the reconstruction of several stages of work processes and at the same time, the local forest history between 97 BCE and 249 CE:

(1) A local oak dominated uneven-aged broadleaf or mixed forest had been growing during the first century BCE until it was cut in 119 CE for the initial construction phase of a pile row (g 1). As the old-grown trees provided large stem diameters, the timber was split radially, i.e., along the rays, to obtain smaller piles.

(2) Roughly 50 years later, two more rows of piles were assembled (g 2 and g 3). Higher annual growth rates indicate less dense forest stand conditions (Figure 3C). The distribution of felling dates between 164 and 177 CE suggest a decreasing availability of local timber resources (cf. Hughes, 1994).

(3) After the harvest, a coppice-like forest of even-aged oak shoots was growing from the older stools, probably reaching a dense stocking after 20–30 years, as indicated by a visible decrease of annual growth rates (Figure 3C). These were felled after approximately 70 years in 249 CE to provide timber for the last construction phase (g 4).

Characteristic growth patterns in the studied oak samples of phase g 2 and g 3 during the mid-second century CE, identified cyclic cockchafer (Melolontha melolontha L.) outbreaks in 152, 155, 158, and 161 CE (Figure 3B) and provide evidence for the local preponderance of open vegetation (arable land, pasture meadows, orchards), as these insects require such vegetation for their 3–4-year larva stadium (Huiting et al., 2006; Švestka, 2010; Kolář et al., 2013; Billamboz, 2014a). The constantly large proportion of open vegetation, also displayed in local pollen records (Brkojewitsch et al., 2013), indicates a limited amount of local woodland area in Roman times and thus, further supports the model of successive exploitation of consecutive forest generations originating from the same nearby forest area (Rohmer and Tegel, 1999).

Discussion

The short case study demonstrates the possibility to obtain precise information on forest structure and management in the past without the use of written sources and displays the advantage of preventive archeology (Laurelut et al., 2014). Furthermore, it shows the potential of gaining knowledge on forest history from a combination of dendrochronological, archeological, wood anatomical and ecological aspects. As afforestation was not practiced by Roman authorities, except for some sacred districts (Nenninger, 2001), we need to consider a shortage of wood supply in the vicinity of Metz in the mid-second century. For Carnuntum, a roman city of comparable size to Divodurum in today’s Austria (Neubauer et al., 2012), 15,5 ha of forest area were required for the fuelwood for one winter heating season (Lehar, 2017), not including fuelwood for year-round domestic use (e.g., cooking) and production processes (e.g., glass, pottery, metallurgy, lime burning), timber production and other woodworking.

Local to supra-regional shortages of woodland resources occasionally appeared throughout human history and led to different consequences from the abandonment of settlements to shifts in socio-economical strategies. The last severe concerns over supra-regional wood supplies in Europe led to the foundation of forest institutes and the development of forest sciences and modern forestry in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Schmidt, 1998, 2002; Hölzl, 2010). The recent decline of forest history, mentioned above, must be considered in view of a general decline of forest sciences within the last decades (Oesten and von Detten, 2006).

Following the newly formulated definition, forest history is closely connected with environmental history as well as historical ecology and historical geography, when dealing with woodlands and woodland products. Various methods allow for the investigation of past woodlands and human-woodland interactions, for example dendroarcheology, palynology or genetics (Herbig, 2006; Gugerli and Sperisen, 2010; Lindbladh et al., 2013; Billamboz, 2013, 2014b, Marquer et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2018; Wagner et al., 2018; Dominguez-Delmás, 2020). Other disciplines, such as paleoclimatology, paleoecology, archeology or archeobotany, have developed various data archives (Figure 1C), and successfully compared multiple proxy data to obtain new information (e.g., Jacomet, 2013; Lindbladh et al., 2013; Kimiaie and McCorriston, 2014; Tegel et al., 2020). These archives allow scholars to study the history of past woodlands across the Holocene and beyond, providing essential information to overcome temporal limitations in forest history (e.g., Jahns et al., 2019).

However, previous forest history studies have mostly worked with historical methods and are therefore restricted to periods with evolved textuality (e.g., Bamford, 1956; Appuhn, 2010). It is indispensable for future research to extend the temporal focus by consulting wood itself as a primary source for forest history. The investigation of current vegetation can provide important information on former woodland structures. Living trees in old-growth forests can reach back several centuries to the past (e.g., Martin-Benito et al., 2020). Vast amounts of construction timber from past centuries are preserved in historical buildings, providing information for the last millennium (e.g., Hoffsummer and Mayer, 2002; Seiller et al., 2014; Haneca et al., 2020). Under waterlogged conditions, wooden constructions and objects are preserved for millennia (e.g., Tegel et al., 2012; Rybníček et al., 2020). Archeological excavations constantly unearth wooden structures from past epochs and provide new insights into woodlands in prehistoric times (Billamboz, 2003; Čufar et al., 2015; Tegel and Vanmoerkerke, 2016). Combined approaches hold valuable sources for forest history studies (e.g., Jamrichová et al., 2013; McGrath et al., 2015).

The field of dendrochronology offers millennia-long and annually resolved data yielding extensive information on forest composition, structure and possible management as well as anthropogenic species selection, felling activities, timber transport, wood technology and climate (e.g., Kuniholm, 2001; Baillie, 2002; Briffa and Matthews, 2002; Tegel and Vanmoerkerke, 2014; Tegel et al., 2016; Billamboz et al., 2017; Ljungqvist et al., 2018; Haneca et al., 2020; Muigg et al., 2020). Age/diameter models, also suitable for young individuals with few tree rings, might contribute additional information on forest management (Out et al., 2018). Palynological studies provide vast amounts of data for previous forest vegetation and innovative models for spatio-temporal landscape development on local to supra-regional scales (Waller et al., 2012; Lindbladh et al., 2013; Marquer et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2018). Archeobotany and anthracology can contribute specific evidence for resource management strategies by comparing on-site and off-site pollen, charcoal and macrofossil data (Jacomet, 2013; Kabukcu and Chabal, 2020). Recent advances in ancient plant DNA research hold great potential for reconstructing the dynamics of reforestation and species distribution (Wagner et al., 2018).

A general geographical scope for the field of forest history must include all areas with woodland vegetation as well as regions where forest products have been imported by humans (e.g., Hellmann et al., 2013, 2015; Shumilov et al., 2020). Despite earlier attempts for an international approach (Johann, 2006) and occasional studies from Asia (e.g., Liu and Cui, 2002; Sheppard et al., 2004) and Africa (e.g., Stahle et al., 1999; Campbell et al., 2017), the current field of forest history has a strong focus on Europe (e.g., Smith and Whitehouse, 2010; Eckstein et al., 2011; Novák et al., 2019; Wiezik et al., 2020) and North America (e.g., Mackovjak, 2010; Anderson, 2018; Gajewski et al., 2019). Considering that only 14% of today’s global forest lie within temperate zones and 61‘ of the world’s primary forests are located outside this area (FAO, 2020), a global perspective should generally be the aim of future forest history research.

Conclusion

In the last decades, several disciplines from the fields of humanities have adapted and opened up to novel methodological concepts and research designs, leading to new interdisciplinary sub-fields like “environmental archeology” (Branch, 2015; O’Connor, 2019) or “environmental history” (Simmons, 1993, 2008; Hoffmann, 2014). Other fields have traditionally used a combined historical approach, e.g., “historical ecology” (Crumley, 1994; Balée, 1998, 2006; Bürgi and Gimmi, 2007) and “historical geography” (Baker, 2003; Schenk, 2011; Haffke et al., 2011).

Following their lead, the field of forest history will have to (i) open up to multilateral discussions with adjacent fields of both humanities (history, archeology) and sciences (paleoclimatology, paleoecology), (ii) approach research questions with a multidisciplinary spectrum of methods, (iii) position itself in the context of new research fields, e.g., environmental history, and (iv) integrate itself into the wider research context of paleoenvironmental sciences, following the concept of consilience (Wilson, 1998; McCormick, 2011; Izdebski et al., 2016).

Data Availability Statement

Datasets are available on request.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This article processing charge was funded by the Baden-Wuerttemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Art and the University of Freiburg in the funding program Open Access Publishing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Wallace-Hare for language editing.

Footnotes

References

Agnoletti, M. (2000). “The development of forest history research,” in Methods and approaches in forest history, eds M. Agnoletti and S. Anderson (New York, NY: CAB International), 1–20. doi: 10.1079/9780851994208.0001

Agnoletti, M. (2006). Man, forestry, and forest landscapes. Trends and perspectives in the evolution of forestry and woodland history research. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 157, 384–392. doi: 10.3188/szf.2006.0384

Akanuma, H. (2008). The Significance of Early Bronze Age Iron Objects from Kaman-Kalehöyük, Turkey. Anatol. Archaeol. Stud. 17, 313–320.

Alenius, T., Marquer, L., Molinari, C., Heikkilä, M., and Ojala, A. (2020). The environment they lived in: anthropogenic changes in local and regional vegetation composition in eastern Fennoscandia during the Neolithic. Vegetat. Hist. Archaeobot. 2020, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s00334-020-00796-w

Appuhn, K. (2010). A Forest on the Sea. Environmental Expertise in Renaissance Venice. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Arranz-Otaegui, A., Colledge, S., Zapata, L., Teira-Mayolini, L. C., and Ibáñez, J. (2016). Regional diversity on the timing for the initial appearance of cereal cultivation and domestication in southwest Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 14001–14006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612797113

Baillie, M. G. L. (2002). Future of dendrochronology with respect to archaeology. Dendrochronologia 20, 69–85. doi: 10.1078/1125-7865-00009

Baker, A. R. H. (2003). Geography and History. Bridging the Divide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Balée, W. (1998). “Historical ecology: Premises and postulates,” in Advances in Historical Ecology, ed. W. Balée (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), 13–29.

Balée, W. (2006). The research program of historical ecology. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 35, 75–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123231

Bamford, P. W. (1956). Forests and French sea power 1660 –1789. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Bartlett, R. (1993). The Making of Europe. Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 950–1350.

Baudrillart, J. J. (1824). Histoire des forêts et de leur législation: discours préliminaire au Traité général des eaux et forêts. Paris: Mme Huzard.

Behre, K.-E. (2002). “Zur Geschichte der Kulturlandschaft Nordwestdeutschlands seit dem Neolithikum,” in Bericht der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission 83, ed. Römisch-Germanische Kommission des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts (Mainz: RGK), 39–68.

Bennett, K. D., Simonson, W. D., and Peglar, S. M. (1990). Fire and man in post-glacial woodlands in eastern England. J. Archaeol. Sci. 17, 635–642. doi: 10.1016/0305-4403(90)90045-7

Berglund, B. (2003). Human impact and climate changes—synchronous events and a causal link? Quatern. Int. 105, 7–12. doi: 10.1016/s1040-6182(02)00144-1

Bernhardt, A. (1872). Geschichte des Waldeigentums, der Waldwirtschaft und Forstwissenschaft in Deutschland. Erster Band: Von den ältesten Zeiten bis zum Jahre 1750. Berlin: Julius Springer.

Bernhardt, A. (1874). Geschichte des Waldeigentums, der Waldwirtschaft und Forstwissenschaft in Deutschland. Zweiter Band: von 1750 bis 1820. Berlin: Julius Springer.

Bernhardt, A. (1875). Geschichte des Waldeigentums, der Waldwirtschaft und Forstwissenschaft in Deutschland. Dritter Band: von 1820 bis 1860. Berlin: Julius Springer.

Bertrand, G. (1975). “Ouverture: pour une histoire écologique de la France rurale,” in Histoire de la France rurale, eds G. Duby and A. Wallon (Paris: Seuil), 34–113.

Billamboz, A. (2003). Tree rings and wetland occupation in southwest Germany between 2000 and 500 BC: dendroarchaeology beyond dating in tribute to F. H. Schweingruber. Tree Ring Res. 59, 37–49.

Billamboz, A. (2013). “Dendrotypology as a key approach of former woodland and settlement developments. Examples from the prehistoric pile dwellings on Lake Constance (Germany),” in TRACE - Tree Rings in Archaeology, Climatology and Ecology 12. Scientific Technical Report 14/05, eds A. Di Filippo, G. Piovesan, M. Romagnoli, G. Helle, and H. Gärtner (Potsdam: GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences), 6–11. doi: 10.2312/GFZ.b103-1405

Billamboz, A. (2014a). Dendroarchaeology and cockchafers north of the Alps: Regional patterns of a middle frequency signal in oak tree-ring series. Environ. Archaeol. 19, 114–123. doi: 10.1179/1461410313Z.00000000055

Billamboz, A. (2014b). Regional patterns of settlement and woodland developments: Dendroarchaeology in the Neolithic pile-dwellings on Lake Constance (Germany). Holocene 24, 1278–1287. doi: 10.1177/0959683614540956

Billamboz, A., Bleicher, N., and Gassmann, P. (2017). “Dendroarchéologie du Bronze Moyen au Nord et Sud des Alpes : de la chronologie des occupations en milieu humide aux questions de climat et d’écologie,” in Le Bronze moyen et l’origine du Bronze final (XVIIe-XIIIe siècle av. J.-C.) Mémoires d’Archéologie du Grand Est 1, eds T. Lachenal, C. Mordant, T. Nicolas, and C. Véber (Strasbourg: Association por la Valosiation de l’Archéologie du Grand-Est), 601–613.

Bonan, G. (2019). The State in the Forest. Contested Commons in the Nineteenth Century Venetian Alps. Winwick: The White Horse Press.

Bradshaw, R. H. W. (2004). Past anthropogenic influence on European forests and some possible genetic consequences. For. Ecol. Manage. 197, 203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2004.05.025

Bradshaw, R. H. W., Hannon, G. E., and Lister, A. (2003). A long term perspective on ungulate-vegetation interactions. For. Ecol. Manage. 181, 267–280. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1127(03)00138-5

Bradshaw, R., and Mitchell, F. J. G. (1999). The palaeoecological approach to reconstructing former grazing-vegetation interactions. For. Ecol. Manage. 120, 3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1127(98)00538-6

Branch, N. (2015). “Environmental Archaeology,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edn, ed. J. D. Wright (Oxford: Elsevier), 692–698.

Briffa, K. R., and Matthews, J. A. (2002). ADVANCE-10K: a European contribution towards a hemispheric dendroclimatology for the Holocene. Holocene 12, 639–642. doi: 10.1191/0959683602hl576ed

Brkojewitsch, G., Marquié, S., Gauthier, É, Jouanin, G., Sedlbauer, S., Morel, A., et al. (2013). Nouvelles données sur le quartier Outre-Seille à Metz (Moselle) (époques romaine, médiévale et moderne): la fouille de la place Mazelle. Revue archéologique de l’Est 62, 283–314.

Bürgi, M., and Gimmi, U. (2007). Three objectives of historical ecology: the case of litter collecting in Central European forests. Landscape Ecol. 22, 77–87. doi: 10.1007/s10980-007-9128-0

Bürgi, M., Hürlimann, K., and Schuler, A. (2001). Wald- und Forstgeschichte in der Schweiz. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 152, 476–483. doi: 10.3188/szf.2001.0476

Campbell, J. F. E., Fletcher, W. J., Joannin, S., Hughes, P. D., Rhanem, M., and Zielhofer, C. (2017). Environmental Drivers of Holocene Forest Development in the Middle Atlas, Morocco. Front. Ecol. Evolut. 5:113. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00113

Chew, S. C. (2001). World Ecological Degradation: Accumulation, Urbanization, and Deforestation, 3000 BC–2000 AD. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

Cohen, K. M., Finney, S. C., Gibbard, P. L., and Fan, J.-X. (2013). The ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart. Episodes 36, 199–204. doi: 10.18814/epiiugs/2013/v36i3/002

Corvol-Dessert, A. (2003). Le groupe d’histoire des forêts françaises. La revue pour l’histoire du CNRS 8/2003, 1–5. doi: 10.4000/histoire-cnrs.560

Crumley, C. L. (1994). “Historical Ecology: A Multidimensional Ecological Orientation,” in Historical Ecology: Cultural Knowledge and Changing Landscapes, ed. C. L. Crumley (Santa Fe: School of American Research Press), 1–16.

Čufar, K., Tegel, W., Merela, M., Kromer, B., and Veluscek, A. (2015). Eneolithic pile dwellings south of the Alps precisely dated with tree-ring chronologies from the north. Dendrochronologia 35, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.dendro.2015.07.005

Cunliffe, B. (2008). Europe between the oceans: Themes and variations: 9000 BC–AD 1000. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Di Bérgener, A. (1859). Dell’antica storia e giurisprudenza forestale in Italia. Treviso and Venice: G. Longo.

Dominguez-Delmás, M. (2020). Seeing the forest for the trees: New approaches and challenges for dendroarchaeology in the 21st century. Dendrochronologia 62:125731. doi: 10.1016/j.dendro.2020.125731

Dow, G. K., and Reed, C. G. (2015). The origins of sedentism: Climate, population, and technology. J. Econom. Behav. Organizat. 119, 56–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2015.07.007

Dow, G. K., Olewiler, N., and Reed, C. (2005). The Transition to Agriculture: Climate Reversals, Population Density, and Technical Change. Soc. Sci. Res. Network 2005:698342. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.698342

Eckstein, J., Leuschner, H. H., and Bauerochse, A. (2011). Mid-Holocene pine woodland phases and mire development – significance of dendroecological data from subfossil trees from northwest Germany. J. Vegetat. Sci. 22, 781–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01283.x

Firbas, F. (1949). Spät- und nacheiszeitliche Waldgeschichte Mitteleuropas nördlich der Alpen. Band 1: Allgemeine Waldgeschichte. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Firbas, F. (1952). Spät- und nacheiszeitliche Waldgeschichte Mitteleuropas nördlich der Alpen. Band 2: Waldgeschichte der einzelnen Landschaften. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Furay, C., and Salevouris, M. J. (2017). The Methods and Skills of History: A Practical Guide, 4th Edn. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Gajewski, K., Kriesche, B., Chaput, M. A., Kulik, R., and Schmidt, V. (2019). Human–vegetation interactions during the Holocene in North America. Vegetat. Hist. Archaeobot. 28, 635–647. doi: 10.1007/s00334-019-00721-w

Gallé, H., and Quéruel, D. (2019). “La fôret dans la literature médiévale,” in La forêt au Moyen Age, eds S. Bépoix and H. Richard (Paris: Les Belles Lettres), 25–83.

Giesecke, T., Brewer, S., Finsinger, W., Leydet, M., and Bradshaw, R. H. W. (2017). Patterns and dynamics of European vegetation change over the last 15,000 years. J. Biogeogr. 44, 1441–1456. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12974

Gugerli, F., and Sperisen, C. (2010). Genetische Struktur von Waldbäumen im Alpenraum als Folge (post)glazialer Populationsgeschichte. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 161, 207–215. doi: 10.3188/szf.2010.0207

Gyulai, F. (2007). “Seed and fruit remains associated with neolithic origins in the Carpathia Basin,” in The Origins and Spread of Domestic Plants in Southwest Asia and Europe, eds S. Colledge and J. Connolly (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press), 125–140.

Haffke, J., Kleefeld, K., and Schenk, W. (2011). Historische Geographie – Konzepte und Fragestellungen – Gestern – Heute – Morgen. Festschrift für Klaus Fehn zum 75. Geburtstag. Colloquium Geographicum 33. Bergisch Gladbach: E. Ferger.

Haneca, K., Debonne, V., and Hoffsummer, P. (2020). The ups and downs of the building trade in a medieval city: Tree-ring data as proxies for economic, social and demographic dynamics in Bruges (c. 1200–1500). Dendrochronologia 64:125773. doi: 10.1016/j.dendro.2020.125773

Hasel, K., and Schwartz, E. (2006). Forstgeschichte. Ein Grundriss für Studium und Praxis, 3rd Edn. Remagen: Kessel.

Hausrath, H. (1982). Geschichte des deutschen Waldbaus von seinen Anfängen bis 1850. Freiburg: Hochschulverlag.

Hellmann, L., Tegel, W., Eggertsson, O., Schweingruber, F. H., Blanchette, R., Gärtner, H., et al. (2013). Tracing the origin of Arctic driftwood. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 118, 68–76. doi: 10.1002/jgrg.20022

Hellmann, L., Tegel, W., Kirdyanov, A. V., Eggertsson, O., Esper, J., Agafonov, L., et al. (2015). Timber logging in central Siberia is the main source for recent Arctic driftwood. Arctic Antarct. Alpine Res. 47, 43–54.

Herbig, C. (2006). Archaeobotanical investigations in a settlement of the Horgener culture (3300 BC) ‘Torwiesen II’ at Lake Federsee, southern Germany (Archobotanische Untersuchungen in einer Siedlung der Horgener Kultur (3300 BC) ‘Torwiesen II’ am Federsee, Süddeutschland). Environ. Archaeol. 11, 131–142. doi: 10.1179/174963106x97115

Hoffmann, R. (2014). An Environmental History of Medieval Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoffsummer, P., and Mayer, J. (eds) (2002). Les charpentes du Xe au XIXe siècle: Typologie et évolution en France du Nord et en Belgique. Paris: Monum’ – Editions du patrimoine.

Hölzl, R. (2010). Umkämpfte Wälder. Die Geschichte einer ökologischen Reform in Deutschland 1760-1860. Campus Historische Studien 51. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

Hughes, J. D. (1994). Pan’s Travail. Environmental Problems of the Ancient Greeks and Romans. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Huiting, H. F., Moraal, L. G., Griepink, F. C., and Ester, A. (2006). Biology, control and luring of the cockchafer, Melolontha melolontha. Literature report on biology, life cycle and pest incidence, current control possibilities and pheromones. https://edepot.wur.nl/121073 (accessed June 13, 2021).

Hürlimann, K. (2003). Worum geht es in der Wald- und Forstgeschichte? Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 154, 322–327. doi: 10.3188/szf.2003.0322

Huth, M. (2019). “Prosopographie und Mikrohistorie im Dienste der Forstgeschichte,” in Neue Beiträge zur Wald- und Forstgeschichte 1, ed. M. Huth (Remagen-Oberwinter: Kessel), 76–107.

IUFRO (1973). Leitfaden für die Bearbeitung von Regionalwaldgeschichten, Reviergeschichten und Bestandesgeschichten, ed. S6.07 FOREST HISTORY. Zürich: IUFRO.

Izdebski, A., Holmgren, K., Weiberg, E., Stocker, S. R., Büntgen, U., Florenzano, A., et al. (2016). Realising consilience: How better communication between archaeologists, historians and natural scientists can transform the study of past climate change in the Mediterranean. Quatern. Sci. Rev. 136, 5–22. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.10.038

Jacomet, S. (2013). “Archaeobotany: analyses of plant remains from waterlogged archaeological sites,” in The Oxford Handbook of Wetland Archaeology, eds F. Menotti and A. O’Sullivan (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 497–514.

Jahns, S., Begemann, I., and Sudhaus, D. (2019). “Zur spät- und nacheiszeitlichen Geschichte des Waldes in der Niederlausitz,” in Neue Beiträge zur Wald- und Forstgeschichte 1, ed. M. Huth (Remagen-Oberwinter: Kessel), 60–75.

Jamrichová, E., Szabó, P., Hédl, R., Kuneš, P., Bobek, P., and Pelánková, B. (2013). Continuity and change in the vegetation of a Central European oakwood. Holocene 23, 46–56. doi: 10.1177/0959683612450200

Johann, E. (2006). Zur Entwicklung des Forschungsgebietes Wald- und Forstgeschichte in Europa – Rückblick und Ausblick. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 157, 372–376. doi: 10.3188/szf.2006.0372

Kabukcu, C., and Chabal, L. (2020). Sampling and quantitative analysis methods in anthracology from archaeological contexts: Achievements and prospects. Quatern. Int. 2020:004. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2020.11.004

Kimiaie, M., and McCorriston, J. (2014). Climate, human palaeoecology and the use of fuel in Wadi Sana, Southern Yemen. Vegetat. Hist. Archaeobot. 23, 394–392. doi: 10.1007/s00334-013-0394-2

Kolář, T., Rybníèek, M., and Tegel, W. (2013). Dendrochronological evidence of cockchafer (Melolontha sp.) outbreaks in subfossil tree-trunks from Tovaèov (CZ Moravia). Dendrochronologia 31, 29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.dendro.2012.04.004

Kramer, K., Groen, T. A., and van Wieren, S. E. (2003). The interacting effects of ungulates and fire on forest dynamics: an analysis using the model FORSPACE. For. Ecol. Manage. 181, 205–222. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1127(03)00134-8

Krzywinski, K., O’Connell, M., and Küster, H. (eds) (2009). Cultural landscapes of Europe. Fields of Demeter, haunts of Pan. Bremen: Aschenbeck Media.

Kuniholm, P. I. (2001). “Dendrochronology and Other Applications of Tree-ring Studies in Archaeology,” in The Handbook of Archaeological Sciences, eds D. R. Brothwell and A. M. Pollard (London: Wiley), 1–11.

Kuonen, T. (1993). Histoire des forêts de la région de Sion du Moyen-Age à nos jours. Cahiers de Vallesia 3. Sion: Archives de l’Etat.

Küster, H. (2010). Geschichte der Landschaft in Mitteleuropa. Von der Eiszeit bis zur Gegenwart. München: Beck.

Lang, G. (1994). Quartäre Vegetationsgeschichte Europas. Methoden und Ergebnisse. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Laurelut, C., Blancquaert, G., Blouet, V., Klag, T., Malrain, F., Marcigny, C., et al. (2014). “Vingt-cinq ans de recherche préventive protohistorique en France du Nord: Évolution des pratiques et changements de perspectives, de l’accumulation à la synthèse des données,” in Méthodologie des recherches de terrain sur la Préhistoire récente en France. Nouveaux acquis, nouveaux outils, 1987-2012. Actes des premières rencontres Nord/sud de Préhistoire récente, Marseille, mai 2012, eds I. Sénépart, C. Billard, F. Bostyn, I. Praud, and É Thirault (Toulouse: Archives d’Ecologie Préhistorique), 419–457.

Lehar, H. (2017). “Römische Heizsysteme und ihr Verbrauch – Wie viel Wald frisst die Heizung einer römischen Stadt?,” in Wald- und Holznutzung in der römischen Antike. Festgabe für Jutta Meurers-Balke zum 65. Geburtstag. Archäologische Berichte 27, eds T. Kazab-Olschewski and I. Tamerl (Kerpen-Loogh: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte), 203–214.

Lindbladh, M., Fraver, S., Edvardsson, J., and Felton, A. (2013). Past forest composition, structures and processes - How paleoecology can contribute to forest conservation. Biol. Conservat. 168, 116–127.

Lipson, M., Szécsényi-Nagy, A., Mallick, S., Pósa, A., Stégmár, B., Keerl, V., et al. (2017). Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers. Nature 551, 368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature24476

Litt, T., Behre, K.-E., Meyer, K.-D., Stephan, H.-J., and Wansa, S. (2007). Stratigraphische Begriffe für das Quartär des norddeutschen Vereisungsgebietes. Eiszeitalter und Gegenwart Quater. Sci. J. 56, 7–65. doi: 10.3285/eg.56.1-2.02

Litt, T., Brauer, A., Goslar, T., Merkt, J., Balaga, K., Müller, H., et al. (2001). Correlation and synchronisation of Lateglacial continental sequences in northern central Europe based on annually laminated lacustrine sediments. Quater. Sci. Rev. 20, 1233–1249. doi: 10.1016/s0277-3791(00)00149-9

Liu, H., and Cui, H. (2002). Holocene History of Desertification along the Woodland-Steppe Border in Northern China. Quatern. Res. 57, 259–270. doi: 10.1006/qres.2001.2310

Ljungqvist, F. C., Seim, A., and Huhtamaa, H. (2021). Climate and society in European history. WIREs Clim. Change 2021:e691. doi: 10.1002/wcc.691

Ljungqvist, F. C., Tegel, W., Krusic, P. J., Seim, A., Gschwind, F. M., Haneca, K., et al. (2018). Linking European building activity with plague history. J. Archaeol. Sci. 98, 81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2018.08.006

Mackovjak, J. (2010). Tongass Timber: A History of Logging and Timber Utilization in Southeast Alaska. Durham: Forest History Society.

Marquer, L., Gaillard, M.-J., Sugita, S., Poska, A., Trondman, A.-K., Mazier, F., et al. (2017). Quantifying the effects of land use and climate on Holocene vegetation in Europe. Quate. Sci. Rev. 171, 20–37.

Martin-Benito, D., Pederson, N., Férriz, M., and Gea-Izquierdo, G. (2020). Old forests and old carbon: A case study on the stand dynamics and longlivety of aboveground carbon. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:142737. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142737

McCormick, M. (2011). History’s changing climate: climate science, genomics, and the emerging consilient approach to interdisciplinary history. J. Interdiscipl. Hist. 42, 251–273. doi: 10.1162/jinh_a_00214

McGrath, M. J., Luyssaert, S., Meyfroidt, P., Kaplan, J. O., Bürgi, M., Chen, Y., et al. (2015). Reconstructing European forest management from 1600 to 2010. Biogeosciences 12, 4291–4316. doi: 10.5194/bg-12-4291-2015

Meister, U. (1883). Die Stadtwaldungen von Zürich. Ihre Geschichte, Einrichtung und Zuwachsverhältnisse nebst Ertragstafeln für die Rotbuche. Zürich: Orell Füssli & Co.

Mercuri, A. M., Marignani, M., and Sadori, L. (2015). Palaeoecology and long-term human impact in plant biology. Plant Biosyst. 149, 136–143. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2014.998309

Mosandl, R., Summa, J., and Stimm, B. (2010). Coppice-With-Standards: Management Options for an ancient Forest System. For. Ideas 16, 65–74.

Muigg, B., Skiadaresis, G., Tegel, W., Herzig, F., Krusic, P. J., Schmidt, U. E., et al. (2020). Tree rings reveal signs of Europe’s sustainable forest management long before the first historical evidence. Sci. Rep. 10:21832. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78933-8

Nenninger, M. (2001). Die Römer und der Wald. Untersuchungen zum Umgang mit einem Naturraum am Beispiel der römischen Nordwestprovinzen. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner.

Neubauer, W., Doneus, M., Trinks, I., Verhoeven, G., Hinterleitner, A., Seren, S., et al. (2012). “Long-term Integrated Archaeological Prospection at the Roman Town of Carnuntum/Austria,” in Archaeological Survey and the City. Monograph Series. Nr. 3, eds P. Johnson and M. Millett (Oxford: Oxbow), 202–221. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvh1dwwz.12

Novák, J., Abraham, V., Šida, P., and Pokornı, P. (2019). Holocene forest transformations in sandstone landscapes of the Czech Republic: Stand-scale comparison of charcoal and pollen records. Holocene 29, 1468–1479. doi: 10.1177/0959683619854510

O’Connor, T. (2019). Pinned Down in the Trenches? Revisiting environmental archaeology. Internet Archaeol. 53:5. doi: 10.11141/ia.53.5

Oesten, G., and von Detten, R. (2006). Zunkunftsfähige Forstwissenschaften? Eine Standortbestimmung zwischen Anspruch und Wirklichkeit in sieben Thesen und drei Fragen. Institut für Forstökonomie, Arbeitsbericht 43. Freiburg: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität.

Out, W. A., Hänninen, K., and Vermeeren, C. (2018). Using Branch Age and Diameter to Identify Woodland Management: New Developments. Environ. Archaeol. 23, 254–266. doi: 10.1080/14614103.2017.1309805

Pigott V. C. (ed.) (1999). The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World. University Museum Monograph 89 / MASCA Research Papers in Science and Archaeology 16. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

Pinhasi, R., Fort, J., and Ammermann, A. J. (2005). Tracing the Origin and Spread of Agriculture in Europe. PLoS Biol. 3:2220–2228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.003041

Pryor, F. L. (2003). From Foraging to Farming: The So-Called ‘Neolithic Revolution’. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2003:395040. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.395040

Rackham, O. (2003). Ancient Woodland. Its History, Vegetation and Use in England. Dalbeattie: Castlepoint Press.

Radivojević, M., Rehren, T., Kuzmanović-Cvetković, J., Jovanović, M., and Northover, J. P. (2013). Tainted ores and the rise of tin bronzes in Eurasia, c. 6500 years ago. Antiquity 87, 1030–1045. doi: 10.1017/s0003598x0004984x

Roberts, N., Fyfe, R. M., Woodbridge, J., Gaillard, M. J., Davis, B. A. S., Kaplan, J. O., et al. (2018). Europe’s lost forests: a pollen based synthesis for the last 11,000 years. Sci. Rep. 8:716. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18646-7

Rohmer, P. (1996). Metz, Boulevard Paixhans. D.R. A.C. Lorraine, S.R.A., Metz. Bilan Scientif. 1996:74.

Rohmer, P. (1999). Metz (Moselle) Boulevard PAIXHANS. D.F.S. de fouille d’archéologie préventive, A.F.A.N., S. R. A. Metz 1996. Metz: Assotiation pour les fouilles archéologiques nationales/Service régional de l’archéologie.

Rohmer, P., and Tegel, W. (1999). Aménagements en bois dans un ancien lit de la Seille (Metz, Boulevard Paixhans) - Etude d’un ouvrage en milieu fluvial et aspects dendroécologiques du bois d’oeuvre. Nachrichtenblatt Arbeitskreis Unterwasserarchäologie 6, 21–25.

Roth, G. (1879). Geschichte des Forst- und Jagdwesens in Deutschland. Berlin: Wiegandt, Hempel & Parey.

Rubner, H. (2002). Sammelbericht Neue Literatur zur europäischen Forstgeschichte mit besonderer Berücksichtigung Mitteleuropas (1990—2000). VSWG Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 89, 307–316.

Rybníček, M., Koèár, P., Muigg, B., Peška, J., Sedláèek, R., Tegel, W., et al. (2020). World’s oldest dendrochronologically dated archaeological wood construction. J. Archaeol. Sci. 115:105082. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2020.105082

Schmidt, U. E. (1998). Waldressourcenknappheit in Deutschland im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert - eine politisch-historische Analyse. Bielefeld: Schriftenreihe des Forstvereins für Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Schmidt, U. E. (2000). “Neue Ansätze in der Forstgeschichtsforschung,” in Beiträge zur Forstgeschichte - Eine Sammlung von Vorträgen zu generellen Fragestellungen der Geschichtsforschung sowie zu aktuellen Forschungsergebnissen, Vol. 21, ed. Forstliche Versuchs- und Forschungsanstalt Baden-Württemberg (Freiburg: Berichte Freiburger forstliche Forschung), 28–36.

Schmidt, U. E. (2002). Der Wald in Deutschland im 18. und 19.Jahrhundert. Das Problem der Ressourcenknappheit dargestellt am Beispiel der Waldressourcenknappheit in Deutschland im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert - eine historisch-politische Analyse. Saarbrücken: Conte-Verlag.

Schmidt, U. E. (2009). “Historische Aspekte der Energiewaldfrage,” in Forum Forstgeschichte - Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag von Prof. Dr. Egon Gundermann, Vol. 206, ed. J. Hamberger (München: Schriftenreihe des Zentrums Wald Forst Holz Weihenstephan / Forstliche Forschungsberichte München), 98–102.

Scholkmann, B., Kenzler, H., and Schreg, R. (2016). Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit : Grundwissen. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Schuler, A. (1982). Rapport de travail du Groupe I: l‘utilisation et l‘exploitation des forêts, in Actes du Symposium International d‘Histoire Forestière, Nancy, 24-28 septembre 1979. Nancy: ENGREF, 305–316.

Seiller, M., Lohrum, B., Tegel, W., and Werlé, M. (2014). Des châssis de fenêtre en bois du XIe siècle et de nouvelles observations sur les parties orientales de l’ancienne église collégiale de Surbourg. Cahiers alsaciens d’archéologie, d’art et d’histoire 57, 57–74.

Seling, I. (1998). Wissenschaftstheoretische Überlegungen zur Forstgeschichte. Historiographie, Soziologie und Forstwissenschaft. Allgemeine Forst- und Jagdzeitung 169, 52–58.

Shennan, S. (2018). The First Farmers of Europe: An Evolutionary Perspective. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, doi: 10.1017/9781108386029

Sheppard, P. R., Tarasov, P. E., Graumlich, L. J., Heussner, K.-U., Wagner, M., Österle, H., et al. (2004). Annual precipitation since 515 B.C. reconstructed from living and fossil juniper growth of northeastern Qinghai Province, China. Clim. Dynam. 23, 869–881. doi: 10.1007/s00382-004-0473-2

Shumilov, O. I., Kasatkina, E. A., Krapiec, M., Chochorowski, J., and Szychowska-Krapiec, E. (2020). Tree-ring dating of Russian Pomor settlements in Svalbard. Dendrochronologia 62:125721. doi: 10.1016/j.dendro.2020.125721

Simmons, I. G. (2008). Global Environmental History 10,000 BC to AD 2000. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Smith, D., and Whitehouse, N. J. (2010). How fragmented was the British Holocene wildwood? Perspectives on the “Vera” grazing debate from the fossil beetle record. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 29, 539–553. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.10.010

Souckova-Siegelová, J. (2001). Treatment and usage of iron in the Hittite Empire in the 2nd millennium BC. Mediterr. Archaeol. 14, 189–193.

Stahle, D. W., Mushove, P. T., Cleaveland, M. K., Roig, F., and Haynes, G. A. (1999). Management implications of annual growth rings of Pterocarpus angolensis from Zimbabwe. For. Ecol. Manag. 124, 217–229. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1127(99)00075-4

Stephens, L., Fuller, D., Boivin, N., Rick, T., Gauthier, N., Kay, A., et al. (2019). Archaeological assessment reveals Earth’s early transformation through land use. Science 365, 897–902. doi: 10.1126/science.aax1192

Švestka, M. (2010). Changes in the abundance of Melolontha hippocastani Fabr. and Melolontha melolontha (L.) (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) in the Czech Republic in the period 2003–2009. J. For. Sci. 56, 417–428. doi: 10.17221/109/2009-jfs

Tegel, W., and Vanmoerkerke, J. (2014). “Recherches dendroarchéologiques sur la fin de l’âge du fer et le début de l’époque romaine en Champagne-Ardenne,” in Silva et saltus en Gaule romaine: dynamique et gestion des forêts et des zones rurales marginales – Actes du VIIe colloque AGER VII Rennes, 27–28 oct. 2004, eds V. Bernard, F. Favory, and J.-L. Fiches (Besancon: Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté), 175–182. doi: 10.4000/books.pufc.8453

Tegel, W., and Vanmoerkerke, J. (2016). Contribution des bois subfossiles à la chronologie et à l’environnement en France orientale: état de la recherche. Internéo 11, 35–39.

Tegel, W., Elburg, R., Hakelberg, D., Stäuble, H., and Büntgen, U. (2012). Early Neolithic Water Wells Reveal the World’s Oldest Wood Architecture. PLoS One 7:e51374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051374

Tegel, W., Seim, A., Skiadaresis, G., Ljungqvist, F. C., Kahle, H.-P., Land, A., et al. (2020). Higher groundwater levels in western Europe characterize warm periods in the Common Era. Sci. Rep. 10:16284. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73383-8

Tegel, W., Vanmoerkerke, J., Hakelberg, D., and Büntgen, U. (2016). “Des cernes de bois à l’histoire de la conjoncture de la construction et à l’évolution de la pluviométrie en Gaule du Nord entre 500 BC et 500 AD,” in Évolution des sociétés gauloises du Second âge du Fer, entre mutations internes et influences externes. Actes du 38e colloque de l’AFEAF. Revue Archéologique de Picardie n° spécial 30, eds G. Blancquaert and F. Malrain (Amiens: Geers Offset), 639–653.

von Hornstein, F. (1951). Wald und Mensch. Waldgeschichte des Alpenvorlands Deutschlands, Österreichs und der Schweiz. Ravensburg: Otto Maier.

von Hornstein, F. (1958). Waldgeschichte - Vorgang und Darstellung. Allgemeine Forstzeitschrift 13, 733–738.

Wagner, S., Lagane, F., Seguin-Orlando, A., Schubert, M., Leroy, T., Guichoux, E., et al. (2018). High-Throughput DNA sequencing of ancient wood. Mol. Ecol. 27, 1138–1154. doi: 10.1111/mec.14514

Walker, M., Head, M. J., Berkelhammer, M., Björck, S., Cheng, H., Cwynar, L., et al. (2018). Formal ratification of the subdivision of the Holocene Series/Epoch (Quaternary System/Period): two new Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSPs) and three new stages/subseries. Episodes Subcommiss. Quater. Stratigr. 41, 213–223. doi: 10.18814/epiiugs/2018/018016

Waller, M., Grant, M. J., and Bunting, M. J. (2012). Modern pollen studies from coppiced woodlands and their implications for the detection of woodland management in Holocene pollen records. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 187, 11–28. doi: 10.1016/j.revpalbo.2012.08.008

Whitehouse, N. J., and Smith, D. N. (2004). ‘Islands’ in Holocene forests: Implications for Forest Openness, Landscape Clearance and ‘Culture-Steppe’ Species. Environ. Archaeol. 9, 203–212.

Wiezik, M., Jamrichová, E., Hájková, P., Hrivnák, R., Máliš, F., Petr, L., et al. (2020). The Last Glacial and Holocene History of Mountain Woodlands in the Southern Part of the Western Carpathians, with Emphasis on the Spread of Fagus sylvatica. Palynology 44, 709–722. doi: 10.1080/01916122.2019.1690066

Keywords: forest history, dendroarcheology, environmental history, interdisciplinary research, historical wood utilization

Citation: Muigg B and Tegel W (2021) Forest History—New Perspectives for an Old Discipline. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9:724775. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.724775

Received: 14 June 2021; Accepted: 31 August 2021;

Published: 30 September 2021.

Edited by:

Triin Reitalu, Tallinn University of Technology, EstoniaCopyright © 2021 Muigg and Tegel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bernhard Muigg, bXVpZ2dAZGVuZHJvYXJjaGFlb2xvZ3kuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Bernhard Muigg

Bernhard Muigg Willy Tegel

Willy Tegel