- Program in Ecology/Department of Geography, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, USA

Dry forests are particularly subject to wildfires, insect outbreaks, and droughts that likely will increase with climate change. Efforts to increase resilience of dry forests often focus on removing most small trees to reduce wildfire risk. However, small trees often survive other disturbances and could provide broader forest resilience, but small trees are thought to have been historically rare. We used direct records by land surveyors in the late-1800s along 22,206 km of survey lines in 1.7 million ha of dry forests in the western USA to test this idea. These systematic surveys (45,171 trees) of historical forests reveal that small trees dominated (52–92% of total trees) dry forests. Historical forests also included diverse tree sizes and species, which together provided resilience to several types of disturbances. Current risk to dry forests from insect outbreaks is 5.6 times the risk of higher-severity wildfires, with small trees increasing forest resilience to insect outbreaks. Removal of most small trees to reduce wildfire risk may compromise the bet-hedging resilience, provided by small trees and diverse tree sizes and species, against a broad array of unpredictable future disturbances.

Introduction

Dry forests globally may be particularly vulnerable to climatic change, because their setting is prone to wildfires, insect outbreaks, and droughts; these disturbances may increase, and post-disturbance tree recruitment is often poor. Recruitment limitation in forests is a widespread concern (Clark et al., 1999), particularly where moisture is limiting, as in Pinus forests in drier parts of precipitation gradients (Dorman et al., 2013). For example, dry forests of the western USA (Figure S1), which include montane ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) forests and dry mixed-conifer forests also with firs (Abies spp.) and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga), can have poor tree recruitment that limits their recovery after fires, insect outbreaks, and droughts. Tree recruitment in dry P. ponderosa forests of the western USA over the last century has been poor, concentrated in episodic pluvials (Savage et al., 1996), and spatially variable (Stein, 1988; Roccaforte et al., 2012). Mortality of P. ponderosa at their ecotone with lower-elevation woodlands during a 1950s drought (Allen and Breshears, 1998) also indicates vulnerability. Rising temperatures and drought could further reduce tree recruitment in dry forests (Anderson-Teixeira et al., 2013). Climate envelopes of seedlings vs. established trees of P. ponderosa suggest general recruitment failure is underway, possibly a precursor to broader range contraction (Bell et al., 2014).

In contrast, paleoecological research shows that dry forests of the western USA persisted for thousands of years in the face of wildfires, insect outbreaks, and droughts (Jenkins et al., 2011), suggesting recruitment was not generally deficient and historical forests were resilient. However, this persistence appears incongruent with the hypothesis that these dry forests historically had low abundance of seedlings, saplings and small trees (Covington and Moore, 1994; Allen et al., 2002). This hypothesis is based in part on tree-ring reconstructions, which show that large trees were historically dominant in most sampled stands (Williams and Baker, 2012a). However, small trees could have been common, but missed in tree-ring reconstructions because small trees had high mortality rates and may decompose by the time of reconstruction (Allen et al., 2002). Also, tree-ring reconstructions are not located systematically across landscapes and plot-level size-class distributions are often averaged, masking variability (Williams and Baker, 2013). Nonetheless, frequent surface fires were thought to have limited small trees, and some early accounts do suggest low abundance of tree recruitment (Leiberg et al., 1904; Covington and Moore, 1994; Allen et al., 2002). Today, large trees are likely less abundant and small trees more abundant than historically (Covington and Moore, 1994), but our focus is only on historical abundance of small trees, not current abundance. The common hypothesis is that low-severity fires historically limited small trees, so they were a low percentage of total trees and were found across a low percentage of land area.

We use a previously untapped historical source, the General Land Office (GLO) land surveys, which provide spatially extensive direct empirical data on historical tree recruitment (seedlings/saplings, small trees). We use seven study areas that span dry forests of the western USA (Figure S1) to test the hypothesis that dry forests historically had little tree recruitment. We formalize this for the two data sources from the GLO surveys and two components of recruitment abundance: H1: Small trees were <20% of total trees, and H2: Seedlings and saplings (trees < 10 cm diameter) were present on <20% of forest area. Past specific estimates of percentages were lacking; we used test values that conservatively represent the hypotheses. Small trees are ≥10 cm dbh, with an upper size limit of 30–50 cm, defined for each study area (Williams and Baker, 2012a). We measured and compared recent risks of higher-severity wildfires and insect outbreaks in dry forests, separated into ponderosa pine forests and dry mixed-conifer forests, across the western USA using government data. We reviewed the role of tree recruitment in recovery after these disturbances. We suggest a strategy to maintain the resilience of dry forests to future disturbances, based on our findings.

Materials and Methods

Data from the public land survey system, conducted by the U.S. General Land Office, have been widely used in the USA to reconstruct historical vegetation (Schulte and Mladenoff, 2001). Surveys in the study areas were generally done in the late-1800s before widespread expansion of EuroAmerican land uses. The system consists of 9.6 × 9.6 km townships containing thirty-six 1.6 × 1.6 km sections. Surveyors marked quarter corners at the 0.8 km mark and section corners at the 1.6 km mark along section lines. Surveyors were required to record azimuth, distance, species, and diameter of two bearing trees at quarter corners and four trees at section corners. Here we used surveyors' direct estimates of tree diameters. In an accuracy study, we found surveyors estimated diameters with sufficient accuracy to place trees in 10-cm diameter bins (Williams and Baker, 2010). After applying an empirical correction, diameter distributions from bearing trees were 87–88% similar to distributions from plot data (Williams and Baker, 2011), thus are quite accurate. Bearing trees are a statistically valid sample, as they have low bias and error (Williams and Baker, 2010).

We also used section-line data recorded by surveyors. Surveyors in forests were required to record, in order of abundance, the dominant overstory trees and understory plants, often including small trees (seedlings and saplings) and shrubs (Williams and Baker, 2012a). Surveyors also often recorded qualitative estimates of understory tree density. Not all surveyors followed the instructions, thus we limited analysis to the set of surveyors who did so for at least one section-line. The section-line data represent a statistically valid line-intercept estimate of cover (Butler and McDonald, 1983).

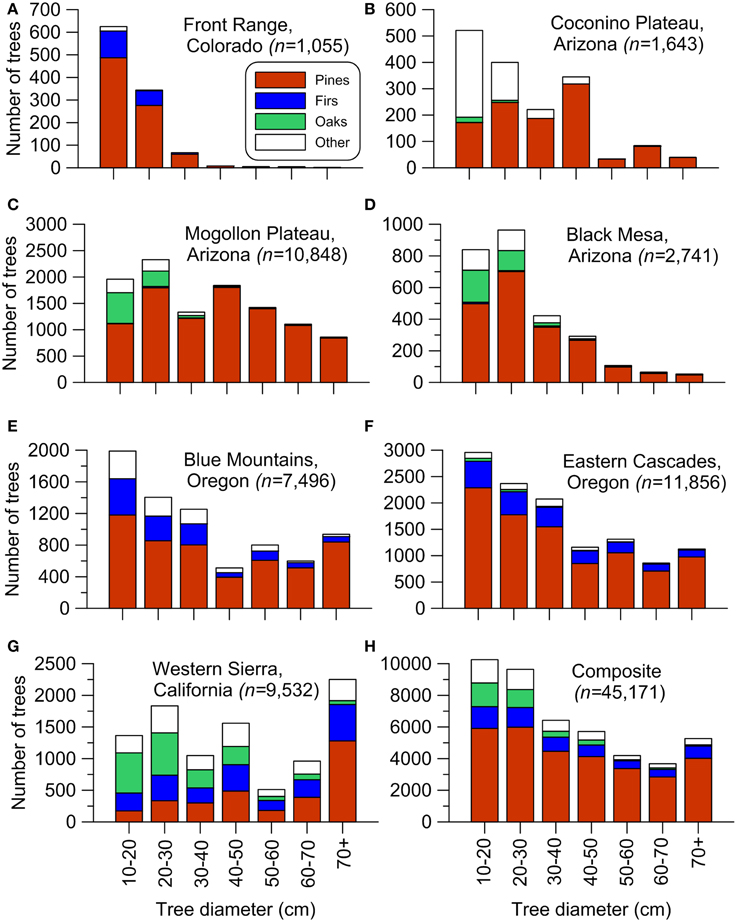

To provide data to test hypothesis H1, we totaled small and large trees in each of the seven study areas and for the composite (Table 1, Figure 1). Small trees were defined as ≥10 cm but ≤40 cm, except ≤30 cm in the Colorado Front Range, where tree growth is slower (Williams and Baker, 2012a) and ≤50 cm in the western Sierra, where tree growth is faster (Baker, 2014). These diameters generally represent trees that are less than about 140 years old (Bright, 1912; Baker, 2012, 2014; Williams and Baker, 2013). Trees this size today are often thought to have widely established after EuroAmerican settlement because of logging, livestock grazing, and fire exclusion (Covington and Moore, 1994; Allen et al., 2002; Franklin and Johnson, 2012), and thus may be removed in restoration treatments. To test H1, we used a chi-square goodness-of-fit test of a null hypothesis that small trees were 0.2 of total trees and large trees were 0.8 of total trees. If this null was rejected, we rejected H1if small trees were <0.2 of total trees. To control error rates, we Bonferroni-corrected α = 0.05, for 8 planned tests, one per study area and one for the composite (Table 1, Figure 1), to α = 0.00625.

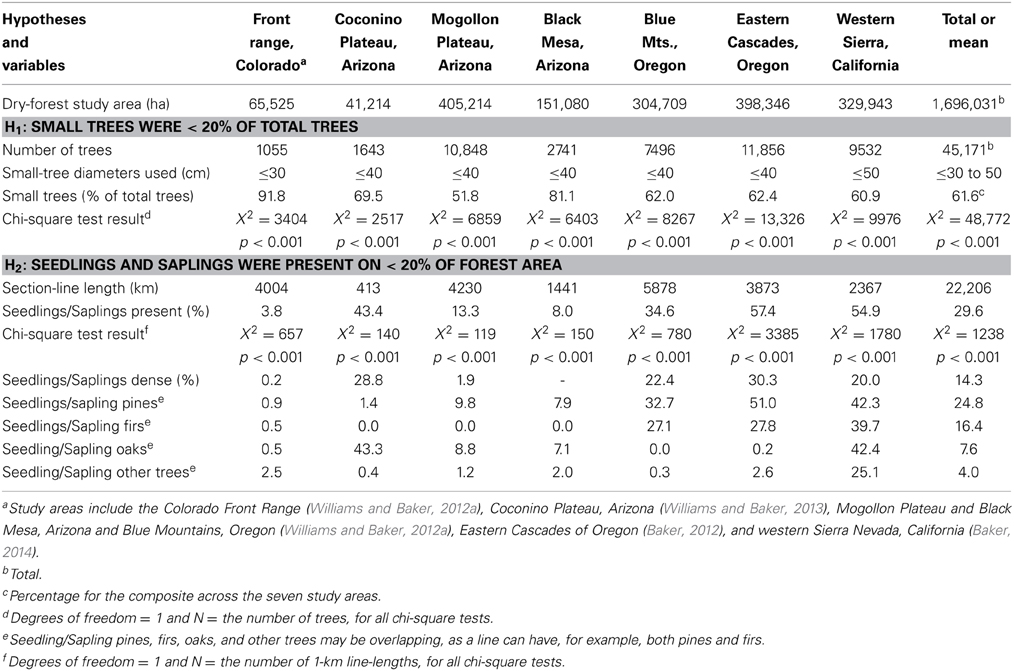

Table 1. Study areas, corresponding number of trees and section-line length in forested area, and the percentage of forest section line-length with seedlings and saplings.

Figure 1. Historical tree size-class distributions for the seven study areas and a composite across all the study areas: (A) Front Range, Colorado, (B) Coconino Plateau, Arizona, (C) Mogollon Plateau, Arizona, (D) Black Mesa, Arizona, (E) Blue Mountains, Oregon, (F) Eastern Cascades, Oregon, (G) Western Sierra, California, (H) The composite of all areas. Distributions use 10-cm bins compatible with the accuracy of diameters measured by the surveyors (Williams and Baker, 2011). Other trees, not found in every area, include Pinus edulis and Juniperus spp., Calocedrus decurrens, Populus tremuloides, and Larix occidentalis. As in Table 1, small trees were defined as trees ≥10 cm but ≤40 cm diameter, except ≤30 cm in Colorado (A) and ≤50 cm in California (G).

To provide data to test H2, we totaled 1-km section lines for which surveyors recorded understory trees in each of the study areas and for the composite. Similarly, to test H2, we used a chi-squared goodness-of-fit test of a null hypothesis that the area with seedlings/saplings was 0.2 of the total forested area and the area without seedlings/saplings was 0.8 of the total forested area. If this null was rejected, we then rejected H2 if seedlings/saplings were found across <0.2 of total forest area. We also Bonferroni-corrected an initial α = 0.05 for 8 planned tests.

We used maps of ponderosa pine and dry mixed-conifer forests from Landfire Biophysical Settings (www.landfire.gov). Wildfire area and severity were from raster maps of actual burned area, not fire perimeters, from the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity (MTBS) program (http://www.mtbs.gov). Insect-caused mortality was from the US Forest Service Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team (http://foresthealth.fs.usda.gov/portal/Flex/IDS). Insect outbreaks were detected using annual aerial surveys. To limit analysis to dry western forests, aerial survey polygons and wildfires were both clipped by the maps of ponderosa pine and dry mixed conifer. The annual sample area varied, but averaged about 9.8 million ha of ponderosa pine and 10.9 million ha of dry mixed-conifer forests (Table S1), about 80% of the 25.8 million ha area of western dry forests.

Comparison of wildfire and insect outbreaks was done for each year both datasets were available. We compared moderate- and high-severity wildfire area, which are the severities with substantial tree mortality, with areas where tree mortality from insects was also substantial, as it was visually detected from aerial surveys. We calculated the rate of wildfire using the fire rotation, which is the number of survey years divided by the fraction of the survey area impacted by fire in those years. The rate of insect outbreaks was determined similarly. Some outbreak areas appeared to overlap in subsequent years and potentially be cumulative. We performed a union and spatial dissolve in GIS to derive a conservative estimate of total area impacted by insect outbreaks over the analysis period. Additional details are in Supplementary Methods.

Results

Small Trees Historically Abundant and Dominant

Hypothesis H1 is rejected across all seven study areas and the composite (Table 1). Small trees generally dominated historical dry forests, ranging from 51.8 to 91.8% of total trees across the seven study areas and equaling 61.6% of trees in the overall composite (Table 1, Figure 1). Small trees can be suppressed older individuals, but were predominantly <140 years old (Bright, 1912; Williams and Baker, 2012a). Small trees were somewhat diverse, with pines most abundant, but also firs, oaks and other conifers and hardwoods (Figure 1). Hypothesis H2 is rejected for study areas in California and Oregon, but not in Arizona and Colorado (Table 1).

Higher Recent Threat from Insect Outbreaks than from Wildfire

Data from government agencies show that insect outbreaks were recently a more significant threat to dry forests than were moderate- to high-severity wildfires; similar data are not available for droughts. It is conservatively estimated (i.e., consolidating all areas of spatial overlap) that insect outbreaks caused substantial detectable tree mortality in 5,193,752 ha of western dry forests over the 1999–2012 period for which spatial data were available, which is 5.6 times the 934,551 ha impacted by moderate- to high-severity wildfires (Table S1). Mean ratios of insect to fire impact were 4.5 in ponderosa pine and 6.9 in dry mixed-conifer forests (Table S1). At the rates during 1999–2012, it would require 311 years for moderate- to high-severity wildfires to burn once across an area equal to the area of western dry forests, but only 56 years for insect outbreaks to impact this area (Table S1). Rotations for fire varied from 265 years in ponderosa pine to 367 years in dry mixed-conifer forests, and for insects from 53 years in dry mixed-conifer to 59 years in ponderosa pine forests (Table S1).

Discussion

Natural Disturbances Fostered Historically Abundant Small Trees and Diverse Tree Sizes

Historical dominance of small trees in dry forests (Figure 1) does not support the hypothesis that surface fires generally kept small trees rare. Small trees had successfully recruited and were dominant in all dry-forest areas (Figure 1). These small, established trees are given more weight, than smaller, more ephemeral seedlings/saplings, for which evidence is more mixed. Seedlings/saplings were abundant in the majority of areas, except two southwestern landscapes (Black Mesa, Mogollon Plateau) and the Colorado Front Range (Table 1). Early scientific sources corroborate limited seedlings/saplings in these areas (Leiberg et al., 1904; Williams and Baker, 2012b). Early foresters emphasized preserving advanced recruitment during logging (Pearson, 1923). Thus, recent high-severity fires do not have unprecedented poor recruitment (Savage and Mast, 2005). Seedling/sapling populations in these landscapes must have fluctuated, since small trees had been able to recruit and dominate all dry forests (Figure 1). Particular sequences of fires, droughts, and other disturbances may explain fluctuating seedling/sapling populations (Dugan and Baker, in press), and reinforce the historical role of advanced recruitment.

Dominance of small trees, and even ephemeral seedling/sapling populations in most areas, indicates more imperfect limitation of tree recruitment by historical low-severity fires than previously thought. Other disturbances, including droughts, insect outbreaks, and more severe fires likely killed canopy trees and increased tree recruitment, particularly if followed by pluvials (Savage et al., 1996; Dugan and Baker, in press). The Colorado Front Range and Black Mesa (Williams and Baker, 2012a) had the greatest dominance of small trees (Figures 1A,D), and our reconstructions showed these areas had more higher-severity fires (Williams and Baker, 2012a,b). Historical abundance of small trees and importance of higher-severity fires in structuring tree populations across dry-forest landscapes are supported by an independent dataset of tree ages (Odion et al., 2014). Higher-severity fires likely interacted with other disturbances to produce diverse tree sizes that were together more resilient to disturbance than would have been the case if only low-severity fires had occurred and large trees had dominated. Historical dominance by small trees and diverse trees sizes are consistent with long-term persistence and resilience of dry forests after disturbances (Jenkins et al., 2011).

Abundant Small Trees and Diverse Tree Sizes Confer Resilience in Modern Forests

Modern observations also document key, but contrasting roles for advance recruitment and surviving larger trees in forest resilience after fires, insect outbreaks, and droughts. Higher-severity fires may be followed by variable recruitment, including poor recruitment, lags in recruitment, or abundant recruitment in some areas (Roccaforte et al., 2012), with large, surviving trees and proximity to them important (Bonnet et al., 2005; Haire and McGarigal, 2010).

About a dozen bark-beetles, that kill trees over large areas of dry forests in the western USA, are the major outbreak insects (Bentz et al., 2010; Weed et al., 2013). In this case, larger trees are differentially susceptible, which often leaves smaller surviving trees as the key source of post-outbreak recruitment. Vulnerability of larger trees to bark beetles is related to greater food resources (Raffa et al., 2008). In a 1970s outbreak of mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) in ponderosa pine in Colorado, tree survival was substantially higher for trees <20 cm diameter (McCambridge et al., 1982). Similarly, western pine beetles (Dendroctonous brevicomis) kill relatively few trees <40 cm (Miller and Keen, 1960). However, Ips in Arizona preferentially kill smaller trees (Negrón et al., 2009). Nonetheless, advance recruitment generally dominates post-outbreak recruitment. After spruce beetle (DeRose and Long, 2010) and mountain pine beetle outbreaks (Astrup et al., 2008), small trees present before outbreaks dominated post-outbreak recruitment. Since these small trees were more diverse than pre-outbreak canopy trees, post-outbreak forests may have greater resilience to future outbreaks (Diskin et al., 2011; Kayes and Tinker, 2012).

Drought often also differentially kills the largest, oldest trees, with less mortality in small and mid-sized trees (Allen et al., 2010), thus also leaving advance recruitment. Drought effects on tree mortality can be widespread and affect forests for centuries (Allen et al., 2010). Drought also influences the occurrence of wildfires, insect outbreaks, and regional tree mortality (Allen et al., 2010), thus it is difficult to parse the impacts of drought alone.

The upshot is that both small trees and surviving larger trees and a diversity of tree species provide resilience to disturbances. Surviving larger trees are particularly important after higher-severity fires and abundant small trees are particularly important after insect outbreaks and droughts.

Restoring and Maintaining the Bet-Hedging Resilience of Historical Forests

Current restoration strategies that seek to increase forest resilience focus predominately on impacts from severe wildfires, but bark-beetle outbreaks and other insects affected 5.6 times the area of western dry forests impacted by moderate- to high-severity fires over the most recent 14-year period (1999–2012). Current rates of moderate- and high-severity fire, with a combined rotation of 311 years (Table S1), would likely not prevent recovery of old-growth forests in the interlude between fires, but rates of insect outbreaks, with a rotation of 56 years (Table S1), could prevent recovery of most older dry forests. Previous research, using the same data sources, in a more limited and lower-elevation area in the southwestern United States, found that beetle-outbreaks affected 2.5–4 times as much area as moderate- to severe wildfires (Williams et al., 2010). Both wildfires (Dennison et al., 2014) and beetle-outbreaks (Bentz et al., 2010; Weed et al., 2013) are increasing in parts of the western United States. Future outcomes are uncertain and complex, however, as beetle-outbreaks can affect wildfire probability (Simard et al., 2011), and as tree mortality occurs, both beetle outbreaks and wildfires could become self-limited (Williams et al., 2010).

Ecological restoration of public dry forests in the western USA is increasingly a goal, because these forests were altered by unsustainable logging, livestock grazing, and fire exclusion that allowed abundant small trees to recruit (Covington and Moore, 1994). Retaining older trees, while removing most small trees up to ages or sizes of trees recruited since EuroAmerican settlement (Figure S2A), is thus often a restoration focus (Covington and Moore, 1994; Allen et al., 2002; Abella et al., 2006; Franklin and Johnson, 2012). Typical upper tree age and size limits are 120–150 years old or 30–50 cm diameter (Abella et al., 2006; Franklin and Johnson, 2012).

We show here, however, that these small trees were the tree sizes historically dominant in these forests (Figure 1, Table 1), thus removing most small trees so they are no longer dominant is not ecological restoration. There are also efforts underway to increase resilience of forests to droughts by removing most small trees and lowering stand density. However, stand density does not appear to play a major role in level of tree mortality from drought (Ganey and Vojta, 2011). Thus, strategies to reduce most small trees are neither restorative nor very effective.

We suggest diverse historical tree sizes and abundant and dominant small trees long provided bet hedging in dry-forest landscapes subject to unpredictable disturbances. These forests can be more effectively restored and their resiliency to future disturbances increased by maintaining or restoring the historical abundance, dominance, and diversity of small trees, while also restoring large trees depleted by logging (Figure S2B). This can be achieved with historically congruent diversities of forest structures across landscapes, based on GLO and other spatial reconstructions. This bet-hedging landscape approach to ecological restoration is consistent with long-term persistence of historical forests, the high current threat from insects, and would likely confer more resilience to disturbances, that may all increase in the future, than would just retaining larger or older trees across large areas.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This research had no specific funding source, and builds on datasets from previous research.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fevo.2014.00088/abstract

References

Abella, S. R., Fulé, P. Z., and Covington, W. W. (2006). Diameter caps for thinning southwestern ponderosa pine forests: viewpoints, effects, and tradeoffs. J. For. 104, 407–414.

Allen, C. D., and Breshears, D. D. (1998). Drought-induced shift of a forest-woodland ecotone: rapid landscape response to climate variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 14839–14842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14839

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Allen, C. D., Macalady, A. K., Chencouni, H., Bachelet, D., McDowell, N., Vennetier, M., et al. (2010). A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 259, 660–684. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001

Allen, C. D., Savage, M., Falk, D. A., Suckling, K. F., Swetnam, T. W., Schulte, T., et al. (2002). Ecological restoration of southwestern ponderosa pine ecosystems: a broad perspective. Ecol. Applic. 12, 1418–1433. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2002)012[1418:EROSPP]2.0.CO;2

Anderson-Teixeira, K., Miller, A. D., Mohansk, J. E., Hudiburg, T. W., Duval, B. D., and DeLucia, E. H. (2013). Altered dynamics of forest recovery under a changing climate. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 2001–2021. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12194

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Astrup, R., Coates, K. D., and Hall, E. (2008). Recruitment limitation in forests: lessons from an unprecedented mountain pine beetle epidemic. For. Ecol. Manage. 256, 1743–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2008.07.025

Baker, W. L. (2012). Implications of spatially extensive historical data from surveys for restoring dry forests of Oregon's eastern Cascades. Ecosphere 3, 23. doi: 10.1890/ES11-00320.1

Baker, W. L. (2014). Historical forest structure and fire in Sierran mixed-conifer forests reconstructed from General Land Office survey data. Ecosphere 5, 79. doi: 10.1890/ES14-00046.1

Bell, D. M., Bradford, J. B., and Lauenroth, W. K. (2014). Early indicators of change: divergent climate envelopes between tree life stages imply range shifts in the western United States. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 23, 168–180. doi: 10.1111/geb.12109

Bentz, B. E., Régniére, J., Fettig, C. J., Hansen, E. M., Hayes, J. L., Hicke, J. A., et al. (2010). Climate change and bark beetles of the western United States and Canada: direct and indirect effects. Bioscience 60, 602–613. doi: 10.1525/bio.2010.60.8.6

Bonnet, V. H., Schoettle, A. W., and Shepperd, W. D. (2005). Postfire environmental conditions influence the spatial pattern of regeneration for Pinus ponderosa. Can. J. For. Res. 35, 37–47. doi: 10.1139/x04-157

Bright, G. A. (1912). A Study of the Growth of Yellow Pine in Oregon. Report, Umatilla National Forest, Pendleton, Oregon.

Butler, S. A., and McDonald, L. L. (1983). Unbiased systematic sampling plans for the line intercept method. J. Range Manage. 36, 463–468. doi: 10.2307/3897941

Clark, J. S., Beckage, B., Camill, P., Cleveland, B., HilleRisLambers, J., Lichter, J., et al. (1999). Interpreting recruitment limitation in forests. Am. J. Bot. 86, 1–16. doi: 10.2307/2656950

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Covington, W. W., and Moore, M. M. (1994). Southwestern ponderosa pine forest structure: changes since Euro-American settlement. J. For. 92, 39–47.

Dennison, P. E., Brewer, S. C., Arnold, J. D., and Moritz, M. A. (2014). Large wildfire trends in the western United States, 1984-2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2928–2933. doi: 10.1002/2014GL059576

DeRose, R. J., and Long, J. N. (2010). Regeneration response and seedling bank dynamics on a Dendroctonus rufipennis-killed Picea engelmannii landscape. J. Veg. Science 21, 377–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2009.01150.x

Diskin, M., Rocca, M. E., Nelson, K. N., Aoki, C. F., and Romme, W. H. (2011). Forest development trajectories in mountain pine beetle disturbed forests of Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado. Can. J. For. Res. 41, 782–792. doi: 10.1139/x10-247

Dorman, M., Svoray, T., Perevolotsky, A., and Sarris, S. (2013). Forest performance during two consecutive drought periods: diverging long-term trends and short-term along a climatic gradient. For. Ecol. Manage. 310, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2013.08.009

Dugan, A. J., and Baker, W. L. (in press). Sequentially contingent fires, droughts, and pluvials structured a historical dry-forest landscape and suggest future contingencies. J. Veg. Sci.

Franklin, J. F., and Johnson, K. N. (2012). A restoration framework for federal forests in the Pacific Northwest. J. For. 110, 429–439. doi: 10.5849/jof.10-006

Ganey, J. L., and Vojta, S. C. (2011). Tree mortality in drought-stressed mixed-conifer and ponderosa pine forests, Arizona, USA. For. Ecol. Manage. 261, 162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2010.09.048

Haire, S. L., and McGarigal, K. (2010). Effects of landscape patterns of fire severity on regenerating ponderosa pine forests (Pinus ponderosa) in New Mexico and Arizona, USA. Landsc. Ecol. 25, 1055–1069. doi: 10.1007/s10980-010-9480-3

Jenkins, S. E., Sieg, C. H., Anderson, D. E., Kaufman, D. S., and Pearthree, P. A. (2011). Late Holocene geomorphic record of fire in ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests, Kendrick Mountain, northern Arizona, USA. Int. J. Wildland Fire 20, 125–141. doi: 10.1071/WF09093

Kayes, L. J., and Tinker, D. B. (2012). Forest structure and regeneration following a mountain pine beetle epidemic in southeastern Wyoming. For. Ecol. Manage. 263, 57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2011.09.035

Leiberg, J. B., Rixon, T. F., and Dodwell, A. (1904). Forest Conditions in the San Francisco Mountains Forest Reserve, Arizona. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper No. 22, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

McCambridge, W. F., Hawksworth, F. G., Edminster, C. B., and Laut, J. G. (1982). Ponderosa Pine Mortality Resulting from a Mountain Pine Beetle Outbreak. USDA Forest Service Research Paper RM-235, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Miller, J. M., and Keen, F. P. (1960). Biology and Control of the Western Pine Beetle, a Summary of Fifty Years of Research. USDA Miscellaneous Publication 800, Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D.C.

Negrón, J. F., McMillin, J. D., Anhold, J. A., and Coulson, D. (2009). Bark beetle-caused mortality in a drought-affected ponderosa pine landscape in Arizona, USA. For. Ecol. Manage. 257, 1353–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2008.12.002

Odion, D. C., Hanson, C. T., Arsenault, A., Baker, W. L., DellaSala, D. A., Hutto, R. L., et al. (2014). Examining historical and current mixed-severity fire regimes in ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests of western North America. PLoS ONE 9:e87852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087852

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pearson, G. A. (1923). Natural Reproduction of Western Yellow Pine in the Southwest. USDA Department Bulletin No. 1105, Superintendent of Documents, Washington, DC.

Raffa, K. F., Aukema, B. H., Bentz, B. J., Carroll, A. L., Hicke, J. A., Turner, M. G., et al. (2008). Cross-scale drivers of natural disturbances prone to anthropogenic amplification: the dynamics of bark beetle eruptions. Bioscience 58, 501–517. doi: 10.1641/B580607

Roccaforte, J. P., Fulé, P. Z., Chancellor, W. W., and Laughlin, D. C. (2012). Woody debris and tree regeneration dynamics following severe wildfires in Arizona ponderosa pine forests. Can. J. For. Res. 42, 593–604. doi: 10.1139/x2012-010

Savage, M., Brown, P. M., and Feddema, J. (1996). The role of climate in a pine forest regeneration pulse in the southwestern United States. Ecoscience 3, 310–318.

Savage, M., and Mast, J. N. (2005). How resilient are southwestern ponderosa pine forests after crown fires? Can. J. For. Res. 35, 967–977. doi: 10.1139/x05-028

Schulte, L. A., and Mladenoff, D. J. (2001). The original US public land survey records: their use and limitations in reconstructing presettlement vegetation. J. For. 99, 5–10.

Simard, M., Romme, W. H., Griffin, J. M., and Turner, M. G. (2011). Do mountain pine beetle outbreaks change the probability of active crown fire in lodgepole pine forests? Ecol. Monogr. 81, 3–24. doi: 10.1890/10-1176.1

Stein, S. J. (1988). Explanations of the imbalanced age structure and scattered distribution of ponderosa pine within a high-elevation mixed coniferous forest. For. Ecol. Manage. 25, 139–152. doi: 10.1016/0378-1127(88)90125-9

Weed, A. S., Ayres, M. P., and Hicke, J. A. (2013). Consequences of climate change for biotic disturbances in North American forests. Ecol. Monogr. 83, 441–470. doi: 10.1890/13-0160.1

Williams, A. P., Allen, C. D., Millar, C. I., Swetnam, T. W., Michaelsen, J., Still, C. J., et al. (2010). Forest responses to increasing aridity and warmth in the southwestern United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 50, 21289–21294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914211107

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Williams, M. A., and Baker, W. L. (2010). Bias and error in using survey records for ponderosa pine landscape restoration. J. Biogeogr. 37, 707–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02257.x

Williams, M. A., and Baker, W. L. (2011). Testing the accuracy of new methods for reconstructing historical structure of forest landscapes using GLO survey data. Ecol. Monogr. 81, 63–88. doi: 10.1890/10-0256.1

Williams, M. A., and Baker, W. L. (2012a). Spatially extensive reconstructions show variable-severity fire and heterogeneous structure in historical western United States dry forests. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 21, 1042–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00750.x

Williams, M. A., and Baker, W. L. (2012b). Comparison of the higher-severity fire regime in historical (A.D. 1800s) and modern (A.D. 1984-2009) montane forests across 624,156 ha of the Colorado Front Range. Ecosystems 15, 832–847. doi: 10.1007/s10021-012-9549-8

Keywords: dry forests, wildfires, insect outbreaks, droughts, climate change, resilience, land surveys, bet-hedge

Citation: Baker WL and Williams MA (2015) Bet-hedging dry-forest resilience to climate-change threats in the western USA based on historical forest structure. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2:88. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2014.00088

Received: 10 November 2014; Paper pending published: 29 November 2014;

Accepted: 22 December 2014; Published online: 13 January 2015.

Edited by:

Scott Andrew Mensing, University of Nevada, Reno, USAReviewed by:

John Birks, University of Bergen, NorwayChristy Briles, University of Colorado Denver, USA

Copyright © 2015 Baker and Williams. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: William L. Baker, Program in Ecology/Department of Geography, University of Wyoming, Dept. 3371, 1000 E. University Ave., Laramie, Wyoming 82071, USA e-mail:YmFrZXJ3bEB1d3lvLmVkdQ==

William L. Baker

William L. Baker Mark A. Williams

Mark A. Williams