- 1School of Earth Sciences and Engineering, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Guangdong Provincial Key Lab of Geodynamics and Geohazards, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 3Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory, Zhuhai, China

- 4Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

Permeability evolution in coal reservoirs during CO2-enhanced coalbed methane (ECBM) production is strongly influenced by swelling/shrinkage effects related to sorption and desorption of CO2 and CH4, respectively. Recent research has demonstrated fully coupled stress–strain–sorption–diffusion behavior in small samples of cleat-free coal matrix material exposed to a sorbing gas. However, it is unclear how such effects influence permeability evolution at the scale of a cleated coal seam and whether a simple fracture permeability model, such as the Walsh elastic asperity loading model, is appropriate. In this study, we performed steady-state permeability measurements, to CH4 and CO2, on a cylindrical sample of highly volatile bituminous coal (25 mm in diameter) with a clearly visible cleat system, under (near) fixed volume versus fixed stress conditions. To isolate the effect of sorption on permeability evolution, helium (non-sorbing gas) was used as a control fluid. All flow-through tests reported here were conducted under conditions of single-phase flow at 40°C, at applied Terzaghi effective confining pressures of 14–41 MPa. Permeability evolution versus effective stress data were obtained under both fixed volume and fixed stress boundary conditions, showing an exponential correlation. Importantly, permeability (

Introduction

Subsurface coal seams typically consist of nanoporous coal matrix material, within which gas adsorption/desorption and diffusion mainly occur, cut by a multiscale network of joints or cleats that act as the main transport paths for gas flow (e.g., Levine, 1996; Laubach et al., 1998; Moore, 2012). Coal seam permeability is widely accepted as the most important factor for assessing the economic feasibility of (CO2) enhanced coalbed methane (ECBM) recovery, playing a significant role in ECBM recovery and reservoir modeling (e.g., Moore, 2012). At fixed gas or fluid pressure, fracture or cleat permeability of coal samples is strongly sensitive to the Terzaghi effective normal stress (confining pressure) or (Terzaghi) effective stress, i.e., the difference between confining pressure (Pc) and pore fluid pressure (Pf) acting on the sample, decreasing rapidly with increasing Terzaghi effective stress at a rate that depends on initial permeability and the stresses employed (e.g., Somerton et al., 1975; Durucan and Edwards, 1986; Chen et al., 2011; Gensterblum et al., 2014). At the same time, adsorption or desorption of CH4/CO2 by coal matrix material due to an increase or decrease in gas/fluid pressure at constant effective stress can cause swelling or shrinkage by several percent (e.g., Levine, 1996; Karacan, 2007; Day et al., 2012; Hol and Spiers, 2012; Liu et al., 2016), also affecting strongly the evolution of fracture permeability in coal seams. Many field pilots and laboratory experiments investigating ECBM production have further demonstrated that the net swelling of coal caused by CH4 displacement by injected CO2 causes an increase in the mean stress under confined subsurface conditions, simply closing transport paths and reducing coal seam permeability (van Bergen et al., 2006; Pini et al., 2009; Fujioka et al., 2010; Kiyama et al., 2011). Much attention has therefore been paid to understanding how these effects interact and how the permeability of coal samples develops during sorption of gases, such as N2, CH4, and CO2 (e.g., Palmer, 2009; Liu et al., 2011a; Liu et al., 2011b; Pan and Connell, 2012; Zhou et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2018). The main findings from experiments and models may be summarized as follows.

First, sorption-induced swelling or desorption-induced shrinkage occurring under fixed volume boundary conditions causes the changes in stress state, involving (poro)elastic or plastic deformation or even failure (Espinoza et al., 2014; Espinoza et al., 2015; Espinoza et al., 2016). This can accordingly lead to a change in permeability (Wang et al., 2013; Espinoza et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2018).

Second, sorption-induced swelling behavior may change the mechanical properties of coal. These effects include 1) a change in elastic compressibility or bulk modulus upon microcracking caused by diffusion-controlled heterogeneous sorption (Gensterblum et al., 2014; Hol et al., 2014; Hol et al., 2012b; Karacan, 2003; Liu et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2011) and 2) an apparent change in Biot effective stress coefficient caused by competition between the change in compressibility and adsorption-induced swelling (Liu and Harpalani, 2014; Sang et al., 2017). Note here that the apparent Biot effective stress coefficient upon adsorption of CH4 or CO2 may be greater than 1.

Third, diffusion-controlled sorption processes can cause permeability evolution even at a fixed effective stress (Chen et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011c; Chen et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2014; Zang and Wang, 2017; Wang et al., 2021). This can be related to the changes in the degree of sorption as equilibrium is approached (Chen et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011c; Chen et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017), or to changes in transport paths (Brown and Scholz, 1985, 1986; Zimmerman et al., 1992) that may in turn be caused by changes in fracture surface roughness, contact area, and aperture during sorption (Hol et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017).

Fourth, experiments and thermodynamics have demonstrated the applied stress could reduce adsorption capacity for CO2 and CH4 by 5–50% (Pone et al., 2009; Hol et al., 2011; Hol et al., 2012a; Liu et al., 2016), thus changing sorption-induced swelling strain (Pan and Connell, 2007; Vandamme et al., 2010). This suggests that a fully coupled stress–strain–sorption process occurring in subsurface coal, which also has an impact on diffusion of gas/fluid molecules in the nanoporous coal matrix (Liu et al., 2017), has to be considered.

However, it remains unclear how the coupled stress–strain–sorption effects influence coal seam permeability via the likely mechanisms described above in the first to the third case, particularly under subsurface confined boundary conditions. In this study, we attempt to determine how the coupled stress–strain–sorption behavior occurring at in situ subsurface boundary conditions, where swelling is constrained by the surrounding rock mass, influences permeability evolution and whether this permeability evolution can be adequately quantified in the simple elastic asperity loading model for crack closure developed by Walsh (1981). To achieve this, flow-through tests were performed on a cored bituminous coal sample to measure permeability evolution during flow-through of helium, CH4, and CO2, under both fixed volume and fixed stress boundary conditions. The influence of effective normal stresses on permeability was compared with the Walsh permeability model. On this basis, we discuss the likely mechanisms and effects of stress–strain–sorption on the Walsh effective stress coefficient for permeability and on the internal structure of the transport paths carrying gas/fluid flow. Finally, the implications of our findings for (CO2) ECBM recovery are discussed.

Experimental Aspects

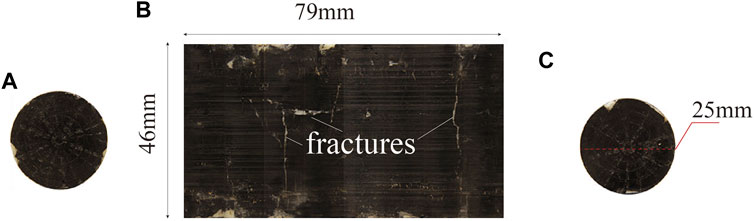

We performed measurements of permeability to CH4 and CO2, under either (near) fixed volume or fixed stress boundary conditions. The tests were performed on a cylindrical sample of highly volatile bituminous coal (25 mm in diameter) with a clearly visible cleat system (see Figure 1), using the steady-state flow method. Helium (non-sorbing gas) was used as a control fluid, in an attempt to isolate the effect of sorption on permeability evolution. All measurements were conducted under conditions of single-phase flow at 40°C, using the purpose-designed apparatus shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1. Photograph of the sample taken after the permeability experiment, consisting of (A,C) view of two flat ends and (B) rolled-out image of the full outer surface of the cylindrical sample (sample height = 46 mm, circumference = 79 mm). The initial fractures visible on the sample surface were filled with glue (white and yellow in color) to avoid failure of the sample upon employing the confining pressures. Fractures without glue may be formed during the permeability experiment. Note that mechanical failure of the sample was not observed.

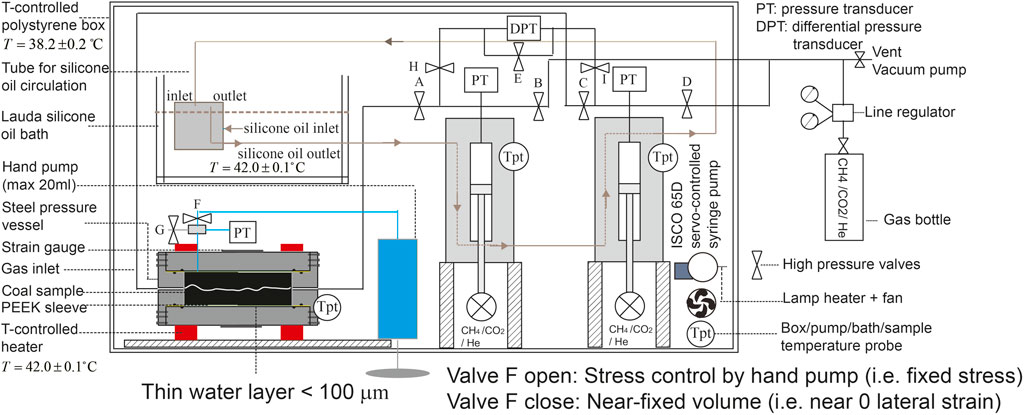

FIGURE 2. Schematic illustration of the complete experimental setup. The cylindrical sample, sleeved by a PEEK jacket, is located inside the cylindrical steel pressure vessel. The vessel, wrapped in two electrical heaters at 42.0 ± 0.1°C, is connected to two ISCO 65D syringe pumps used for permeability measurements to CH4/CO2/He. Note that a thin water layer between the PEEK sleeve and the steel vessel supports a confining pressure. The valve F is used for controlling boundary conditions employed to the sample. The confining pressure applied to the sample is measured by the pressure transducer and is controlled by a hand pump. The pressure difference between two ISCO pumps is measured by a differential pressure transducer (DPT). The temperature of the ISCO pumps is controlled at 42.0 ± 0.1°C by using Lauda silicone oil bath. An internally heated foam–polystyrene box is constructed around the syringe pumps, hand pump, oil bath, and permeability vessel to control the air temperature around the full setup at 38.2 ± 0.2°C.

Sample Preparation and Treatment

The sample material used consisted of highly volatile bituminous coal collected from Brzeszcze 364, Poland. The Brezeszcze coal has a vitrinite reflectance of 0.77 ± 0.05% and contains 74.1% carbon, 5.3% hydrogen, 1.4% nitrogen, 0.7% sulfur, and 18.5% oxygen (Hol et al., 2011). Specifically, the Brezeszcze coal contains 2.9% moisture content and 5.2% ash content. We prepared a single cylindrical sample of the Brezeszcze coal measuring 25 mm in diameter by 45.84 mm in length, cored normal to bedding (see Figure 1). Note that the sample contains a visible multiscale network of cleats. The mass and the bulk volume of the sample, measured before the permeability test, were 28.02 g and 22.49 ml, respectively. Taking 1.45 g/ml as the matrix/grain density of the Brezeszcze coal (Hol and Spiers, 2012), calculation of the initial porosity of the sample used in this study yields ∼14%.

After evacuation, the sample was pre-treated with CH4 to allow equilibration under fixed volume boundary conditions, employing 10 MPa fluid pressure and an initial confining pressure of 11 MPa. This took around 5 days and produced a maximum self-swelling stress of 30.7 MPa. The sample was then evacuated for several days for gas desorption and was then kept in a vacuum oven for a month before starting the experiment. Note that microfractures might be formed during this treatment, speeding up gas diffusion and adsorption equilibration during the experiment (Hol et al., 2012a).

Apparatus

The apparatus used in the present experiment (Figure 2) consisted of a stainless steel pressure vessel, housing the jacketed sample and wrapped in two temperature-controlled electrical heaters maintained at 42.0 ± 0.1°C. The ends of the sample were fully attached to the closure nuts of the steel vessel, sealed using O-rings against the inner PEEK jacket. The two closure nuts and the sample assembled inside the jacket were fixed to the steel vessel using screws, sealed using O-rings against the inner vessel wall, i.e., the sample was subjected to a fixed displacement in the axial direction. The jacketed sample was pressurized externally (radially compressed) as Pc, via a thin water layer (<100 μm) inside the vessel, using water as a confining fluid, driven by a hand volumetric pump and measured by an independent pressure transducer. The high pressure valve F (Figure 2) is used for achieving constant volume (close) or fixed stress (open) boundary conditions. Gas was introduced into the sample via a high pressure line passing through the closure nut of the steel vessel. The gas flow-through was controlled by two independent ISCO 65D volumetric (syringe) pumps (cf. Hol and Spiers, 2012). Both ISCO pumps were operated in constant pressure mode in the present experiments, allowing the upstream and downstream pressures (Pu and Pd) and mean pore fluid pressure (

Experimental Procedures

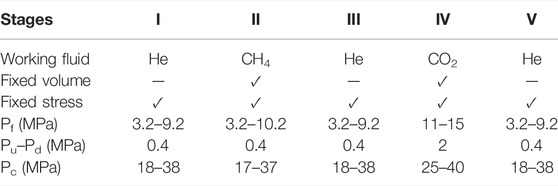

We performed one multi-stage experiment on the single cylindrical sample (Figure 1) at a constant temperature of 40°C. We measured permeability of the sample to helium, CH4, and CO2 under fixed volume versus stress boundary conditions, using the steady-state method, employing Terzaghi effective stresses of 14–41 MPa. The following stages were conducted using helium, CH4, helium, CO2, and again helium (Stages I–V), in that order, as summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Experimental lists indicating the working fluid, boundary conditions, mean pore fluid pressure (Pc) employed in the flow-through tests, pressure difference between upstream and downstream (Pu–Pd), and confining pressure (Pc) employed at fixed stress for each stage.

Stages I, III, V

Helium permeability. We measured helium permeability of the sample under the fixed stress boundary condition only because helium, as a non-sorbing gas, cannot induce coal swelling. In these stages, helium was first introduced into the sample at a given pore pressure and confining pressure. After stabilization, the flow-through test was then performed by increasing the upstream pressure by 0.4 MPa. The mean helium pressure employed in these stages was 3.2, 5.2, 7.2, and 9.2 MPa, respectively. At each mean fluid pressure, the confining pressure was stepped up (and down) in the range of 18–38 MPa, in an attempt to determine the effect of confining pressure on permeability and whether such effect is reversible. As a result, we obtained permeability of the sample to helium at Terzaghi effective stresses of 13–35 MPa for Stages I, III, V. Note that helium behaves as a supercritical fluid at PT conditions employed in this study.

Stage II

CH4 permeability. We measured the CH4 permeability of the sample under both fixed volume and fixed stress boundary conditions. The confining pressure was first applied, followed by closure of the valve F (see Figure 2). The initial confining pressure before the introduction of CH4 under the fixed volume boundary condition was 25.4 MPa. CH4 was then injected into the sample, and the pore pressure was controlled at 10 MPa using the downstream pump. Note that the Pc–Pf–T conditions thus achieved were similar to those at a burial depth of 1 km. After the introduction of CH4, the confining pressure measured by the pressure transducer instantaneously increased due to poroelastic effects, followed by a gradual increase that reflected sorption-induced swelling. The confining pressure was finally increased to 38.8 MPa after 171 h. During the sorption-induced swelling process, the CH4 uptake (mmol/g) was obtained from the volume change in the downstream pump, and permeability at given confining pressures was measured through flow-through tests performed by increasing the upstream pressure by 0.4 MPa. Note that each permeability test lasted for 20–40 min, and during such short intervals, the change in the total mass of two ISCO pumps was negligible. As equilibrium was approached with CH4 at a pore fluid pressure of 10 MPa under the fixed volume boundary condition, we performed the permeability tests under the fixed stress boundary condition (i.e., the valve F was maintained open and the confining pressure was adjusted to remain constant using the hand pump), following similar procedures described in Stage I. By comparison, the mean fluid pressures of 10.2, 8.2, 6.2, and 3.2 MPa, and Terzaghi effective stresses of 14–34 MPa, were employed, respectively. Note that we waited several to tens of hours for re-equilibration after a change in either pore pressure or confining pressure, prior to each flow-through test performed under the fixed stress boundary condition.

Stage IV

CO2 permeability. Following similar procedures as described in Stage II, we measured permeability of the sample to CO2 under both the fixed volume and fixed stress boundary conditions. Under the fixed volume boundary condition, CO2 was injected into the sample, using the downstream pump, at an initial confining pressure of ∼25 MPa. Note that we could not measure CO2 uptake properly during the injection because it is quite difficult to eliminate poroelastic effects, particularly when CO2 pressure and confining pressure cannot be maintained constant. After CO2 pressure stabilization at 10 MPa, we performed the flow-through test continuously, employing a pressure difference of ∼2 MPa between upstream and downstream, achieved by increasing the upstream pressure. Note that this process was unlike the flow-through tests performed at intervals during CH4 sorption, employing a pressure difference of ∼0.4 MPa. The near equilibration took around ∼44 h, and the confining pressure increased to 52 MPa. Also note that the steady-state method cannot properly give the adsorption capacity for CO2 during the flow-through test in the permeability range of 10−18–10−19 m2. Following the similar procedures performed for CH4 and helium under the fixed stress condition, we performed the permeability tests at mean fluid pressures of 11, 13, 15 MPa, employing Terzaghi effective stresses of 14–29 MPa. The pressure difference between upstream and downstream was maintained at ∼2 MPa during all flow-through tests using CO2. Note that CO2 behaves as a supercritical fluid at the conditions employed, so that the effects of phase change can be eliminated.

Note that, before each stage, the sample was evacuated for several days, using a vacuum pump, in an attempt to fully remove the residual gas from the sample used in the previous stage.

Data Acquisition and Processing

The system temperature, confining pressure signals were recorded using a computer equipped with LabView-based software, at a sampling rate of 0.2 Hz. Pump pressure and volume signals were recorded using ISCO 65D panel software at a sampling rate of 0.2 Hz. Note that the data obtained were processed by removing data intervals corresponding to pump re-stroking or other maintenance, correcting for both volume and time offsets accordingly.

Considering the evacuation process performed prior to the flow-through tests and the PT conditions employed in the present study, we focused on single-phase flow and neglected the influence of gas slippage (Klinkenberg) on permeability evolution (e.g., Peach, 1991). The obtained data were accordingly used to calculate the apparent Darcy permeability (

where

Results

Permeability of the sample to helium, CH4, and CO2 as a function of Terzaghi effective stress under the fixed stress boundary condition was obtained. Permeability evolution associated with development of the confining pressure was also obtained for the fixed volume boundary condition performed on CH4 and CO2. All data files obtained from the experiment can be found via the link https://public.yoda.uu.nl/geo/UU01/XOJCFK.html, and key data are illustrated in Figures 3–5.

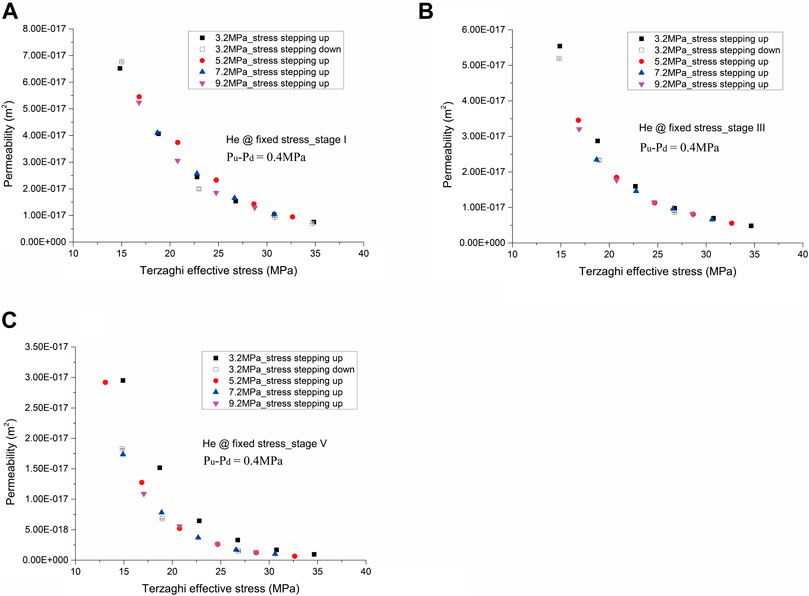

FIGURE 3. Permeability of the sample to helium against Terzaghi effective stress performed under the fixed stress boundary condition at (A) Stage I, (B) Stage III, and (C) Stage V.

Broadly speaking, the permeability of the coal sample measured at the Terzaghi effective stresses employed in this study (in the range of 14–41 MPa) lied in the range of 10−19–10−17 m2, showing the order of permeability measured was helium > CH4 > CO2 at similar Terzaghi effective stresses. The permeability versus Terzaghi effective stress yielded a clear non-linear correlation, and the permeability reduced ∼1-2 orders with increasing Terzaghi effective stress from 14 to 41 MPa. Note here that we, after the experiment, observed some new small visible fractures formed on the surface of the sample, but no mechanical failure (see Figure 1).

Helium Permeability

Permeability measured for helium at a fixed stress boundary condition, illustrated in Figure 3, yielded a function of Terzaghi effective stress, showing a near reversible process at Stages I and III, but clear hysteresis at Stage V. It is also found in Figure 3 that the permeability obtained before and after CH4 flow-through tests (Stages I, III), and after CO2 flow-through tests, shows different values even at similar Terzaghi effective stresses, yielding an order of Stage I > Stage III > Stage V. Specifically, at Stage I, the permeability was 6.5 × 10−17 m2 at a Terzaghi effective stress of 15 MPa and reduced to 6.5 × 10−18 m2 at 35 MPa (Figure 3A). The permeability measured at Stage III was a little smaller than that measured at Stage I (Figure 3B). However, by comparison with the permeability obtained at Stages I and III, it reduced a factor of 3–6 at similar Terzaghi effective stresses, after CO2 flow-through tests, and behaved more sensitive to the change of Terzaghi effective stress. This indicates a permanent effect of CO2 introduction on permeability evolution. In particular, the permeability measured at Stage V was 3 × 10−17 m2 at 15 MPa and reduced to 9.5 × 10−19 m2 at 35 MPa (Figure 3C).

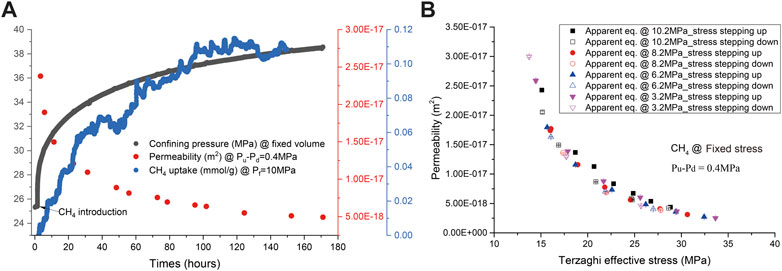

CH4 Permeability

The development of confining pressure and permeability of the sample associated with adsorption amounts during CH4 flow-through tests performed under the fixed volume boundary condition is illustrated in Figure 4A. It is clearly seen that the confining pressure showed fast increase from 25.4 to ∼28 MPa within 1 h, followed by slow evolution up to 38.6 MPa until ∼170 h with CH4 uptake of ∼0.11 mmol/g. The former may be dominated by an instant poroelastic effect and the latter by time-dependent sorption-induced swelling. In the meanwhile, the permeability reduced from 2.4 × 10−17 m2 measured at a Terzaghi effective stress of ∼19 MPa to 5 × 10−18 m2 measured at ∼28 MPa Terzaghi effective stress. The permeability of the sample measured under the fixed stress condition is shown in Figure 4B, as a function of Terzaghi effective stress. The permeability reduced from 3 × 10−17 m2 measured at 14 MPa Terzaghi effective stress to 2.5 × 10−18 m2 at 34 MPa, which are smaller, by a factor of 2, than those measured for helium at Stage I. This may suggest the effect of CH4 sorption on permeability. Also note that permeability versus Terzaghi effective stress plotted in Figure 4B showed little hysteresis, probably because the coal sample has been pre-treated with CH4.

FIGURE 4. Development of CH4 permeability, the confining pressure, and CH4 uptake against time obtained under the fixed volume boundary condition, illustrated in (A,B) showing development of CH4 permeability as a function of Terzaghi effective stress performed under the fixed stress boundary condition.

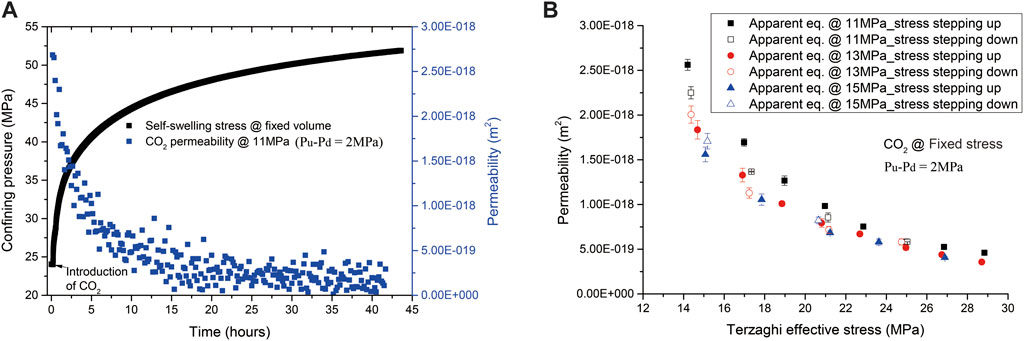

CO2 Permeability

The development of confining pressure and permeability of the sample during CO2 flow-through tests performed under the fixed volume boundary condition is plotted versus time in Figure 5A. The confining pressure showed fast increase from 24 to ∼34 MPa in an hour, followed by a gradual change up to 52 MPa until ∼44 h since first CO2 introduction. This indicates the combined effects of poroelastic and sorption-induced swelling. Meanwhile, the permeability reduced from 2.7 × 10−18 m2 obtained at a Terzaghi effective stress of ∼14 MPa to 1.8 × 10−19 m2 at ∼52 MPa Terzaghi effective stress, which, in magnitude, are an order lower than those for CH4 measured at similar Terzaghi effective stresses. Recall that we did not obtain the CO2 uptake data in this flow-through test. The permeability of the sample measured under the fixed stress condition, plotted in Figure 5B against Terzaghi effective stress, showed that the permeability reduced from 2.6 × 10−18 m2 measured at 14 MPa Terzaghi effective stress to 4 × 10−19 m2 at 29 MPa. These also, in magnitude, are an order lower than those for CH4 measured at similar Terzaghi effective stresses. Such a large difference in permeability may suggest, compared to CH4, CO2 has a faster sorption process, higher sorption-induced swelling, and a stronger sorption effect on permeability, which is consistent with the findings widely reported in the literature (e.g., Gensterblum et al., 2014). Also note that permeability versus Terzaghi effective stress plotted in Figure 5B showed hysteresis, suggesting a permanent change in transport paths of the sample.

FIGURE 5. Development of CO2 permeability and the confining pressure versus time obtained under the fixed volume boundary condition, illustrated in (A,B) showing development of CO2 permeability versus Terzaghi effective stress performed under the fixed stress boundary condition. Note that the scattered permeability data points shown in (A) reflect the noise caused by data processing via moving average at low permeability (<10−18 m2) using the steady-state method.

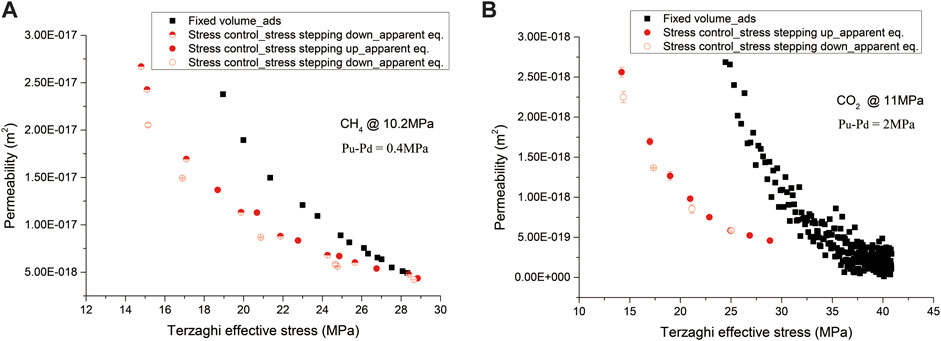

Effect of Boundary Condition on Permeability: Fixed Volume Versus Fixed Stress

Permeability of the sample to CH4 and CO2 performed under fixed volume versus fixed stress boundary conditions, employing the same pore fluid pressure, is plotted against Terzaghi effective stress in Figure 6. It is clear that permeability, even at similar Terzaghi effective stresses, measured under the fixed volume boundary condition is higher than that measured, at equilibration, under the fixed stress boundary condition, reflecting the effect of boundary condition on permeability. Interestingly, the lower the Terzaghi effective stress occurring at the initial sorption process under the fixed volume boundary condition, the higher the difference in permeability upon such effects. This may suggest the effect of boundary condition could be related to the degree of sorption equilibration, depending on diffusion. Particularly, for CH4 shown in Figure 6A, permeability reduced by a factor up to ∼2 at 18.4 MPa, while for CO2 shown in Figure 6B, permeability reduced by an order at 25 MPa. This again reflects CO2 has a stronger sorption effect on permeability evolution.

FIGURE 6. Permeability to CH4 shown in (A) and to CO2 shown in (B), performed under the fixed volume versus the fixed stress boundary condition, employing the same pore fluid pressure, plotted against Terzaghi effective stress. The black and red dots represent the data points measured under the fixed volume and fixed stress boundary conditions, respectively.

Discussion

The flow-through experiment performed in this study demonstrated the permeability reduced exponentially with increasing effective stress, regardless of the fluids used as well as the boundary conditions employed. This suggests the permeability is stress-dependent. Importantly, our results also showed that, at similar Terzaghi effective stresses, the permeability of the sample to CO2 is an order lower than that to CH4, and the permeability to CH4 is also 2–3 times lower than that to helium. This is in good agreement with experimental observations reported in the literature (e.g., Gensterblum et al., 2014). Moreover, our results shown in Figure 6 demonstrated the effect of boundary condition on permeability. This all suggests sorption effects on permeability evolution, independently of poroelastic effects. Interestingly, the differences in helium permeability obtained in Stages I, III, and V suggest a permanent effect of sorption on permeability. It is difficult to distinguish, directly from the experiments, whether this permanent effect is caused by the change of effective stress or by adsorption, especially for the fixed volume boundary condition. Instead, we attempt to use a simple fracture permeability model proposed by Walsh (1981) for an elastic asperity loading framework (i.e., reversible deformation), to distinguish any permanent effects on permeability caused by diffusion-controlled adsorption/desorption. In the following, we will first investigate whether the Walsh permeability model can describe the direct effect of effective normal stress on permeability observed in this study. Subsequently, we will discuss the effects of sorption process on permeability and, finally, the implications of our findings for CO2-ECBM recovery.

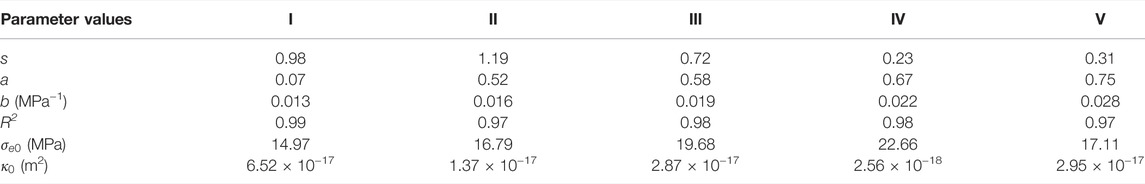

Experimental Data Versus the Walsh Permeability Model: Effect of Normal Stress

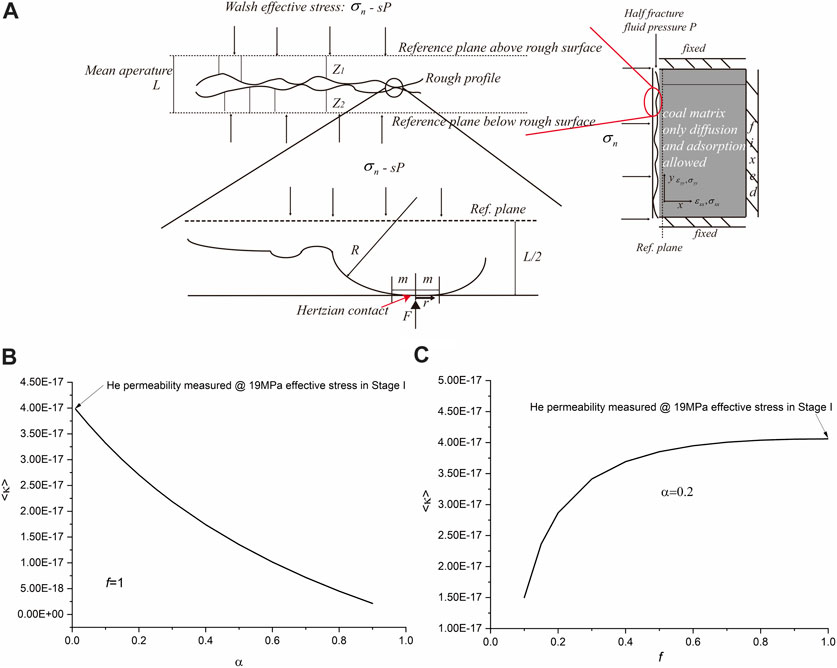

Our results shown in Figure 3, Figure 4B, and Figure 5B demonstrate that the permeability of the coal sample containing visible fractures exponentially reduced with increasing Terzaghi effective stress. This is in good agreement with stress-dependent permeability of coal samples (Somerton et al., 1975; Durucan and Edwards, 1986; Gensterblum et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2011). We here quantitatively determine the direct correlation between permeability and effective stress, using the Walsh permeability model, in an attempt to capture the direct effect of effective normal stress on fracture permeability. Recall that the Walsh permeability model was constructed for describing the fracture permeability change between two roughness surfaces, with respect to the change in the applied effective stress, which considered the effect of elastic fracture asperity contacts on fracture permeability (

Here,

This simplification, in turn, is exactly in the same format as the cubic model using the exponential function expressing the correlation between the effective stress and the joint closure (cf. Cook, 1992). In addition, the effective stress is given by Walsh as

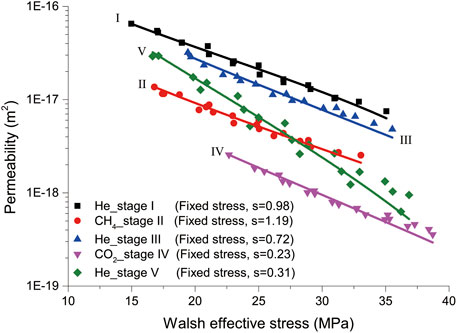

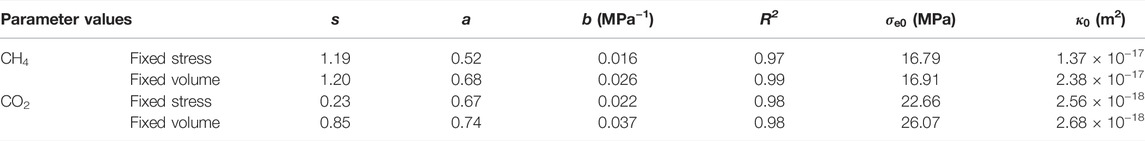

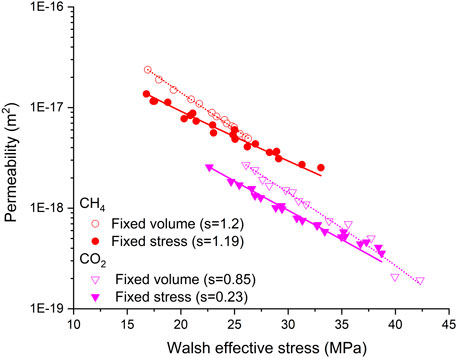

We here focus on the permeability data obtained under the fixed stress boundary condition in which the coal sample was equilibrated with the gas/fluid at given Pc–Pf–T conditions. We further assumed that 1) the fracture contacts and roughness, i.e., the values of s, a, and b in Eq. 2, remained constant during the flow-through tests performed at each experimental stage (Stages I–V, see Table 1), while the values may be different between stages, implying permanent changes in coal structures and flow paths, and 2) the permeability development shown in Figure 3, Figure 4B, and Figure 5B for each stage is only dependent on the change in Walsh effective stress. Following the least square method and using the Walsh permeability model presented in Eq. 2, we obtained the parameters s, a, and b for each stage, as listed in Table 2. On this basis, the permeability data obtained for each stage are plotted in Figure 7, as a function of the Walsh effective stress. Note that the values of

TABLE 2. List of the values of

FIGURE 7. Permeability measured at all stages performed under the fixed stress boundary condition, plotted in logarithms, as a function of the Walsh effective stress. Note that s is the Walsh effective stress coefficient, and the lines represent the best fittings of Eq. 2 to the data points. The values of

Following the above assumptions, the difference in these parameter values obtained from helium permeability data measured at different stages may imply the permanent changes in fracture structure and transport paths upon the sorption effects. Note that the permeability to helium measured at Stage V was most sensitive to the Walsh effective stress. This can be explained by the highest b value obtained at Stage V, as it means the contact areas of the fracture, after CO2 adsorption, would increase the most, i.e., the aperture spacing would reduce the most, at given changes in the Walsh effective stress. This all indicates that the Walsh permeability model can well describe stress-dependent permeability of coal with respect to sorbing gases, given proper parameter values reflecting the sorption effects on fracture properties.

Effects of Stress–Strain–Sorption on Permeability Evolution

Apart from the stress-dependent permeability, Figure 7 also clearly indicates that permeability of the sample measured at similar Walsh effective stresses lies in the following order:

Effective Permeability: Effect of Stress–Strain–Sorption Behavior on Fracture Contacts

Recall that the Walsh permeability model was used to determine how permeability changes with respect to the change in effective stress. This means that the large reduction in permeability upon CO2 adsorption observed at similar Walsh effective stresses cannot be explained by the changes in parameter values listed in Table 2. In an attempt to gain insights into such sorption-induced permeability changes, we introduce the effective permeability

FIGURE 8. A conceptual fracture model shown in (A) illustrating the effect of asperity contacts on fracture permeability, including (B) the effect of contact area ratio (α) on permeability development when the fracture contains the circular cylindrical asperities only (i.e., f = 1) and (C) the effect of shape factor f for ellipse contacts on permeability development at a constant contact area ratio of α = 0.2. Note that the starting permeability is 4 × 10−19 m2 that was measured at Stage I for helium at 19 MPa Walsh effective stress (s = 0.98).

Zimmerman et al. (1992) modified the above relation for the ellipse contacts by introducing the shape factor f, as

where

Crude analysis performed using Eqs 3, 4 suggests the combined changes in contact area ratio and contact shape could reduce permeability from 4 × 10−17 to 4 × 10−18 or even lower (see Figures 8B,C), which is in good agreement with the change observed in Figure 7. This means the large reduction in permeability upon CO2 adsorption may be explained by the changes in contact area and contact shape. Similar changes that occurred in the fracture structure caused by sorption-induced heterogeneous swelling are also reported by Wu et al. (2011). Such changes can be caused by the coupled stress–strain–sorption behavior of coal upon adsorption of CH4 and CO2 (Liu et al., 2016). Liu et al. (2016) constructed a thermodynamic model for describing adsorbed concentration of any sorbing gas/fluid by the coal matrix subjected to the applied stress states. The model demonstrates the higher the applied stress, the lower the adsorbed concentration. Considering the fracture structure illustrated in Figure 8A, the asperity solid contact with high normal stress would adsorb little CH4 or CO2 accompanied by little sorption-induced swelling, while the free surfaces of the aperture having low normal stress would adsorb more CH4 or CO2, accompanied by large swelling. Such heterogeneous deformation occurring at fracture surfaces upon adsorption would lead to an increase in

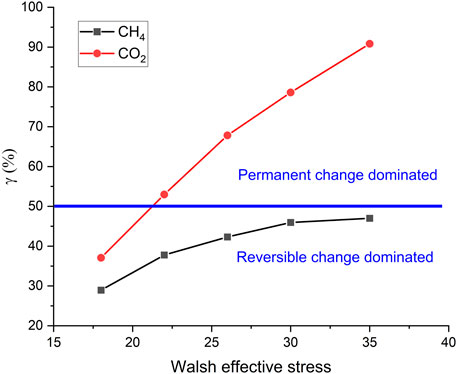

To quantitatively evaluate the role of such permanent changes occurring on fracture surfaces in controlling permeability, we introduce a ratio

where

FIGURE 9.

Effects of Sorption-Induced Swelling on Walsh Effective Stress Coefficient

Figure 7 and Table 2 indicate that s experienced an increase from 0.98 to 1.19 upon CH4 sorption, followed by a significant reduction to ∼0.3 upon CO2 sorption. To explain such changes, we introduce a revised Walsh effective stress coefficient (

where

Returning now to our data, the increase of

Now, we discuss the term

Effect of Sorption Equilibration Degree on Permeability

Permeability against Terzaghi effective stress shown in Figure 6 suggests an apparent effect of boundary condition on permeability at similar Terzaghi effective stresses. Corrected for such effect on parameters s, a, and b (see Table 3), permeability plotted in Figure 10 as a function of Walsh effective stress demonstrates the similar results that permeability measured under the fixed volume boundary condition is higher than that measured at similar Walsh effective stresses under the fixed stress boundary condition that was equilibrated with CH4/CO2 and that the largest difference occurred at the initial sorption process. This suggests that gradual, diffusion-controlled equilibration also plays a role in changing the fracture structure through the mechanism discussed in Effective Permeability: Effect of Stress–Strain–Sorption Behavior on Fracture Contacts, as illustrated in Figure 8 (Liu et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). This is also supported by the evidence that CH4 uptake by the Brezeszcze coal obtained from this study performed under the fixed volume boundary condition was 0.11 mmol/g, which is ∼7 times lower than that obtained, at equilibrium, from our previous study performed, at similar Pc–Pf–T conditions, under the fixed stress boundary condition (Liu et al., 2016). In addition, this mechanism, together with the mechanisms discussed in Effects of Sorption-Induced Swelling on Walsh Effective Stress Coefficient, could also explain why the values for the Walsh effective stress coefficient obtained under the fixed volume boundary condition are higher than those obtained under the fixed stress boundary condition. Similarly, Liu and co-authors (Liu et al., 2011c; Peng et al., 2014) proposed that diffusion-controlled time-dependent sorption-induced swelling as a mechanism caused permeability of coal to CO2 and CH4 showing a “V” shape with increasing pore fluid pressure at a fixed confining pressure that was observed by Wang et al. (2011).

TABLE 3. List of the values of

FIGURE 10. Permeability data obtained from Figure 6, plotted in logarithms, as a function of the Walsh effective stress. Circle points represent all permeability data for CH4 shown in Figure 6A, while triangle points represent selected data for CO2 shown in Figure 6B. Solid and hollow represent the fixed volume and fixed stress boundary conditions, respectively. s is the Walsh effective stress coefficient, and the lines represent the best fittings of Eq. 2 to the data points. The values of

Implications for ECBM and Reservoir Modeling

The results obtained from our flow-through experiment, performed at 40°C under the fixed volume boundary condition, employing an initial confining pressure of ∼25 MPa and 10 MPa pore fluid pressure, imply that injecting CO2 into coal seams at a burial depth of ∼1 km with initial permeability in the order of 10−17 would result in a dramatical reduction in permeability by ∼2 orders, accompanied by permanent changes occurring in transport paths. This, together with our results obtained under the fixed stress boundary condition, further demonstrates that permeability evolution of coal seam during CO2-ECBM recovery operating at in situ conditions could be strongly influenced by the fully coupled stress–strain–sorption–diffusion effects, involving 1) self-stress generated by time-dependent adsorption-induced swelling or desorption-induced shrinkage plus instant poroelastic effects, 2) the change in (Walsh) effective stress coefficient upon sorption-induced swelling, 3) sorption-induced closure of transport paths independently of poroelastic effect, and 4) diffusion-controlled heterogeneous gas penetration and equilibration. This may offer a new basis to enhance coal seam permeability by controlling those mechanisms.

Regarding reservoir modeling, our analysis suggests the Walsh permeability model offers a promising basis for relating permeability evolution to the change of in situ stress, regardless of boundary conditions, using appropriate parameter values corrected for the effects of stress–strain–sorption. The parameter values can be obtained from the lab experiments, but it remains unclear whether those values can be extrapolated to the field predictions. Importantly, our results strongly suggest monitoring evolution of in situ stresses during CO2-ECBM recovery may offer the most promising basis for predicting reservoir permeability evolution.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the coupled stress–strain–sorption effects on coal permeability evolution under the fixed volume versus the fixed stress boundary conditions, by performing flow-through tests on a cylindrical bituminous coal sample with respect to helium, CH4, and CO2, employing PT conditions equivalent to a burial depth of ∼1 km. Using the framework of the elastic asperity loading model developed by Walsh as a reference model, we determined the specific mechanisms responsible for permeability evolution upon sorption process, both qualitatively and quantitatively. The main findings are summarized as follows:

1) The Brezeszcze coal sample used in this study shows helium permeability, at a constant Terzaghi effective stress of 15 MPa, which decreases from 6.5 × 10−17 m2 measured before CH4 introduction, to 5.5 × 10−17 m2 after CH4 sorption, and to 1.7-3×10−17 m2 after CO2 sorption, demonstrating a permanent change upon sorption.

2) Regardless of the boundary conditions employed and the fluids used in this study, the permeability of the coal sample decreased exponentially with increasing Terzaghi effective stress, in a manner that can be described by the Walsh permeability model. This finding offers a promising basis for predicting permeability evolution with respect to in situ stress changes, i.e., using the Walsh permeability model with appropriate parameter values corrected for the stress–strain–sorption effects.

3) Permeability obtained at similar Walsh effective stresses showed

4) Permeability measured under the fixed volume boundary condition, particularly at the initial sorption process, was higher than that measured at equilibration under the fixed stress boundary condition, even at similar Walsh effective stresses. This apparent effect indicates diffusion-controlled equilibration also plays a considerable role in permeability evolution occurring at a constant Walsh effective stress.

5) Permeability evolution of coal seams with respect to CH4 or CO2 at in situ PT and boundary conditions can be expected to be strongly influenced by the coupled effects of a) self-stress development induced by sorption-induced swelling, b) the change in (Walsh) effective stress coefficient upon sorption-induced swelling, c) sorption-induced closure of transport paths independently of poroelastic effects, and d) heterogeneous gas penetration and equilibration, caused by slow diffusion.

Data Availability Statement

The original data package of this research has been published on EPOS Reposit, and can be found via the link https://public.yoda.uu.nl/geo/UU01/XOJCFK.html.

Author Contributions

All the authors performed investigation and research. Specifically, JL performed experiments, processed data, and wrote the original draft under the supervision of CS. JL and CS formulated the ideas and research goals of this paper. CS conducted a critical review and revision.

Funding

The China Scholarship Council (CSC) is thanked for financial support to the first author to perform this experimental research. The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; project No. 41802230) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangzhou City (project No. 202002030144) are also appreciated for their support to the first author to finish/publish this paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The experimental research was conducted at HPT Lab. Eimert de Graaff, Gert Kastelein, and Floris van Oort are thanked for their technical support. Vincent Brunst is thanked for his technical support to publish the original data package on EPOS Repository.

References

Brown, S. R., and Scholz, C. H. (1985). Closure of Random Elastic Surfaces in Contact. J. Geophys. Res. 90, 5531–5545. doi:10.1029/jb090ib07p05531

Brown, S. R., and Scholz, C. H. (1986). Closure of Rock Joints. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 4939. doi:10.1029/jb091ib05p04939

Chen, R., Qin, Y., Wei, C., Wang, L., Wang, Y., and Zhang, P. (2017). Changes in Pore Structure of Coal Associated with Sc-CO2 Extraction during CO2-ECBM. Appl. Sci. 7, 931. doi:10.3390/app7090931

Chen, Z., Liu, J., Pan, Z., Connell, L. D., and Elsworth, D. (2012). Influence of the Effective Stress Coefficient and Sorption-Induced Strain on the Evolution of Coal Permeability: Model Development and Analysis. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 8, 101–110. doi:10.1016/j.ijggc.2012.01.015

Chen, Z., Pan, Z., Liu, J., Connell, L. D., and Elsworth, D. (2011). Effect of the Effective Stress Coefficient and Sorption-Induced Strain on the Evolution of Coal Permeability: Experimental Observations. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 5, 1284–1293. doi:10.1016/j.ijggc.2011.07.005

Cook, N. G. W. (1992). Natural Joints in Rock: Mechanical, Hydraulic and Seismic Behaviour and Properties under normal Stress. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. Geomechanics Abstr. 29, 198–223. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(92)93656-5

Day, S., Fry, R., and Sakurovs, R. (2012). Swelling of Coal in Carbon Dioxide, Methane and Their Mixtures. Int. J. Coal Geology. 93, 40–48. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2012.01.008

Durucan, S., and Edwards, J. S. (1986). The Effects of Stress and Fracturing on Permeability of Coal. Mining Sci. Technology 3 (3), 205–216. doi:10.1016/s0167-9031(86)90357-9

Espinoza, D. N., Pereira, J.-M., Vandamme, M., Dangla, P., and Vidal-Gilbert, S. (2015). Desorption-induced Shear Failure of Coal Bed Seams during Gas Depletion. Int. J. Coal Geology. 137, 142–151. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2014.10.016

Espinoza, D. N., Vandamme, M., Dangla, P., Pereira, J.-M., and Vidal-Gilbert, S. (2016). Adsorptive-mechanical Properties of Reconstituted Granular Coal: Experimental Characterization and Poromechanical Modeling. Int. J. Coal Geology. 162, 158–168. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2016.06.003

Espinoza, D. N., Vandamme, M., Pereira, J.-M., Dangla, P., and Vidal-Gilbert, S. (2014). Measurement and Modeling of Adsorptive-Poromechanical Properties of Bituminous Coal Cores Exposed to CO2: Adsorption, Swelling Strains, Swelling Stresses and Impact on Fracture Permeability. Int. J. Coal Geology. 134-135, 80–95. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2014.09.010

Fujioka, M., Yamaguchi, S., and Nako, M. (2010). CO2-ECBM Field Tests in the Ishikari Coal Basin of Japan. Int. J. Coal Geology. 82, 287–298. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2010.01.004

Gensterblum, Y., Ghanizadeh, A., and Krooss, B. M. (2014). Gas Permeability Measurements on Australian Subbituminous Coals: Fluid Dynamic and Poroelastic Aspects. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 19, 202–214. doi:10.1016/j.jngse.2014.04.016

Hol, S., Gensterblum, Y., and Massarotto, P. (2014). Sorption and Changes in Bulk Modulus of Coal - Experimental Evidence and Governing Mechanisms for CBM and ECBM Applications. Int. J. Coal Geology. 128-129, 119–133. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2014.04.010

Hol, S., Peach, C. J., and Spiers, C. J. (2011). Applied Stress Reduces the CO2 Sorption Capacity of Coal. Int. J. Coal Geology. 85, 128–142. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2010.10.010

Hol, S., Peach, C. J., and Spiers, C. J. (2012a). Effect of 3-D Stress State on Adsorption of CO2 by Coal. Int. J. Coal Geology. 93, 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2012.01.001

Hol, S., and Spiers, C. J. (2012). Competition between Adsorption-Induced Swelling and Elastic Compression of Coal at CO2 Pressures up to 100MPa. J. Mech. Phys. Sol. 60 (11), 1862–1882. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2012.06.012

Hol, S., Spiers, C. J., and Peach, C. J. (2012b). Microfracturing of Coal Due to Interaction with CO2 under Unconfined Conditions. Fuel 97, 569–584. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2012.02.030

Karacan, C. Ö. (2003). Heterogeneous Sorption and Swelling in a Confined and Stressed Coal during CO2 Injection. Energy Fuels 17 (6), 1595–1608. doi:10.1021/ef0301349

Karacan, C. Ö. (2007). Swelling-induced Volumetric Strains Internal to a Stressed Coal Associated with CO2 Sorption. Int. J. Coal Geology. 72, 209–220. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2007.01.003

Kiyama, T., Nishimoto, S., Fujioka, M., Xue, Z., Ishijima, Y., Pan, Z., et al. (2011). Coal Swelling Strain and Permeability Change with Injecting Liquid/supercritical CO2 and N2 at Stress-Constrained Conditions. Int. J. Coal Geology. 85, 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2010.09.010

Laubach, S. E., Marrett, R. A., Olson, J. E., and Scott, A. R. (1998). Characteristics and Origins of Coal Cleat: A Review. Int. J. Coal Geology. 35, 175–207. doi:10.1016/s0166-5162(97)00012-8

Levine, J. R. (1996). Model Study of the Influence of Matrix Shrinkage on Absolute Permeability of Coal Bed Reservoirs. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 109, 197–212. doi:10.1144/gsl.sp.1996.109.01.14

Liu, J., Chen, Z., Elsworth, D., Miao, X., and Mao, X. (2011a). Evolution of Coal Permeability from Stress-Controlled to Displacement-Controlled Swelling Conditions. Fuel 90, 2987–2997. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2011.04.032

Liu, J., Chen, Z., Elsworth, D., Qu, H., and Chen, D. (2011b). Interactions of Multiple Processes during CBM Extraction: A Critical Review. Int. J. Coal Geology. 87, 175–189. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2011.06.004

Liu, J., Fokker, P. A., and Spiers, C. J. (2017). Coupling of Swelling, Internal Stress Evolution, and Diffusion in Coal Matrix Material during Exposure to Methane. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122 (2), 844–865. doi:10.1002/2016jb013322

Liu, J., Spiers, C. J., Peach, C. J., and Vidal-Gilbert, S. (2016). Effect of Lithostatic Stress on Methane Sorption by Coal: Theory vs. experiment and Implications for Predicting In-Situ Coalbed Methane Content. Int. J. Coal Geology. 167, 48–64. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2016.07.012

Liu, J., Wang, J., Chen, Z., Wang, S., Elsworth, D., and Jiang, Y. (2011c). Impact of Transition from Local Swelling to Macro Swelling on the Evolution of Coal Permeability. Int. J. Coal Geology. 88, 31–40. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2011.07.008

Liu, S., and Harpalani, S. (2014). Determination of the Effective Stress Law for Deformation in Coalbed Methane Reservoirs. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 47, 1809–1820. doi:10.1007/s00603-013-0492-6

Moore, T. A. (2012). Coalbed Methane: A Review. Int. J. Coal Geology. 101, 36–81. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2012.05.011

Palmer, I. (2009). Permeability Changes in Coal: Analytical Modeling. Int. J. Coal Geology. 77, 119–126. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2008.09.006

Pan, Z., and Connell, L. D. (2007). A Theoretical Model for Gas Adsorption-Induced Coal Swelling. Int. J. Coal Geology. 69, 243–252. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2006.04.006

Pan, Z., and Connell, L. D. (2012). Modelling Permeability for Coal Reservoirs: A Review of Analytical Models and Testing Data. Int. J. Coal Geology. 92, 1–44. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2011.12.009

Peach, C. J. (1991). Influence of Deformation on the Fluid Transport Properties of Salt Rocks. Geologica Ultraiectina 77, 1–238. (PhD thesis).

Peng, Y., Liu, J., Wei, M., Pan, Z., and Connell, L. D. (2014). Why Coal Permeability Changes under Free Swellings: New Insights. Int. J. Coal Geology. 133, 35–46. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2014.08.011

Pini, R., Ottiger, S., Burlini, L., Storti, G., and Mazzotti, M. (2009). Role of Adsorption and Swelling on the Dynamics of Gas Injection in Coal. J. Geophys. Res. 114, B04203. doi:10.1029/2008jb005961

Pone, J. D. N., Halleck, P. M., and Mathews, J. P. (2009). Sorption Capacity and Sorption Kinetic Measurements of CO2 and CH4 in Confined and Unconfined Bituminous Coal. Energy Fuels 23 (9), 4688–4695. doi:10.1021/ef9003158

Sang, G., Elsworth, D., Liu, S., and Harpalani, S. (2017). Characterization of Swelling Modulus and Effective Stress Coefficient Accommodating Sorption-Induced Swelling in Coal. Energy Fuels 31 (9), 8843–8851. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b00462

Shi, R., Liu, J., Wei, M., Elsworth, D., and Wang, X. (2018). Mechanistic Analysis of Coal Permeability Evolution Data under Stress-Controlled Conditions. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 110, 36–47. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.07.003

Somerton, W. H., Söylemezoḡlu, I. M., and Dudley, R. C. (1975). Effect of Stress on Permeability of Coal. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. Geomechanics Abstr. 12, 129–145. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(75)91244-9

Tanikawa, W., and Shimamoto, T. (2009). Comparison of Klinkenberg-Corrected Gas Permeability and Water Permeability in Sedimentary Rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 46, 229–238. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2008.03.004

van Bergen, F., Pagnier, H., and Krzystolik, P. (2006). Field experiment of Enhanced Coalbed methane-CO2 in the Upper Silesian basin of Poland. Environ. Geosci. 13, 201–224. doi:10.1306/eg.02130605018

Vandamme, M., Brochard, L., Lecampion, B., and Coussy, O. (2010). Adsorption and Strain: The CO2-induced Swelling of Coal. J. Mech. Phys. Sol. 58, 1489–1505. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2010.07.014

Walsh, J. B. (1981). Effect of Pore Pressure and Confining Pressure on Fracture Permeability. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. Geomechanics Abstr. 18, 429–435. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(81)90006-1

Walsh, J. B. (1965). The Effect of Cracks on the Compressibility of Rock. J. Geophys. Res. 70, 381–389. doi:10.1029/jz070i002p00381

Wang, C., Zhai, P., Chen, Z., Liu, J., Wang, L., and Xie, J. (2017). Experimental Study of Coal Matrix-Cleat Interaction under Constant Volume Boundary Condition. Int. J. Coal Geology. 181, 124–132. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2017.08.014

Wang, C., Zhang, J., Zang, Y., Zhong, R., Wang, J., Wu, Y., et al. (2021). Time-dependent Coal Permeability: Impact of Gas Transport from Coal Cleats to Matrices. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 88, 103806. doi:10.1016/j.jngse.2021.103806

Wang, S., Elsworth, D., and Liu, J. (2013). Permeability Evolution during Progressive Deformation of Intact Coal and Implications for Instability in Underground Coal Seams. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 58, 34–45. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2012.09.005

Wang, S., Elsworth, D., and Liu, J. (2011). Permeability Evolution in Fractured Coal: The Roles of Fracture Geometry and Water-Content. Int. J. Coal Geology. 87, 13–25. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2011.04.009

Wu, Y., Liu, J., Elsworth, D., Siriwardane, H., and Miao, X. (2011). Evolution of Coal Permeability: Contribution of Heterogeneous Swelling Processes. Int. J. Coal Geology. 88, 152–162. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2011.09.002

Zang, J., and Wang, K. (2017). Gas Sorption-Induced Coal Swelling Kinetics and its Effects on Coal Permeability Evolution: Model Development and Analysis. Fuel 189, 164–177. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2016.10.092

Zhang, D., Gu, L., Li, S., Lian, P., and Tao, J. (2013). Interactions of Supercritical CO2 with Coal. Energy Fuels 27 (1), 387–393. doi:10.1021/ef301191p

Zhou, F., Hussain, F., and Cinar, Y. (2013). Injecting Pure N2 and CO2 to Coal for Enhanced Coalbed Methane: Experimental Observations and Numerical Simulation. Int. J. Coal Geology. 116-117, 53–62. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2013.06.004

Zhu, W., Liu, L., Liu, J., Wei, C., and Peng, Y. (2018). Impact of Gas Adsorption-Induced Coal Damage on the Evolution of Coal Permeability. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 101, 89–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2017.11.007

Zimmerman, R. W., Chen, D.-W., and Cook, N. G. W. (1992). The Effect of Contact Area on the Permeability of Fractures. J. Hydrol. 139, 79–96. doi:10.1016/0022-1694(92)90196-3

Keywords: adsorption-induced swelling, swelling stress, Walsh effective stress, transport paths, diffusion and equilibrium, CO2-ECBM

Citation: Liu J and Spiers CJ (2022) Permeability of Bituminous Coal to CH4 and CO2 Under Fixed Volume and Fixed Stress Boundary Conditions: Effects of Sorption. Front. Earth Sci. 10:877024. doi: 10.3389/feart.2022.877024

Received: 16 February 2022; Accepted: 30 March 2022;

Published: 09 May 2022.

Edited by:

Jienan Pan, Henan Polytechnic University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yanjun Meng, Taiyuan University of Technology, ChinaYinbo Zhou, Henan University of Engineering, China

Gaofeng Liu, Henan Polytechnic University, China

Copyright © 2022 Liu and Spiers. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinfeng Liu, bGl1amluZjVAbWFpbC5zeXN1LmVkdS5jbg==

Jinfeng Liu

Jinfeng Liu Christopher J. Spiers4

Christopher J. Spiers4