95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Earth Sci. , 13 January 2023

Sec. Structural Geology and Tectonics

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.1061211

This article is part of the Research Topic Quantitative Characterization and Engineering Application of Pores and Fractures of Different Scales in Unconventional Reservoirs – Volume II View all 39 articles

Guangyin Cai1,2,3

Guangyin Cai1,2,3 Yifan Gu1,2,3*

Yifan Gu1,2,3* Xianyue Xiong4

Xianyue Xiong4 Xingtao Li4

Xingtao Li4 Xiongwei Sun4

Xiongwei Sun4 Jia Ni5

Jia Ni5 Yuqiang Jiang1,2,3

Yuqiang Jiang1,2,3 Yonghong Fu1,2,3

Yonghong Fu1,2,3 Fang Ou6

Fang Ou6The Lower Permian Shanxi Formation in the Eastern Ordos Basin is a set of transitional shale, and it is also a key target for shale gas exploration in China. Three sets of organic-rich transitional shale intervals (Lower shale, Middle shale and Upper shale) developed in Shan 23 Submember of Shanxi Formation. Based on TOC test, X-diffraction, porosity, in-situ gas content experiment and NMR experiments with gradient centrifugation and drying temperature, the reservoir characteristics and pore fluid distribution of the three sets of organic-rich transitional shale are studied. The results show that: 1) The Middle and Lower shales have higher TOC content, brittleness index and gas content, reflecting better reservoir quality, while the Upper shales have lower gas content and fracturing ability. The total gas content of shale in the Middle and Lower shales is high, and the lost gas and desorbed gas account for 80% of the total gas content. 2) The Middle shale has the highest movable water content (32.58%), while the Lower shale has the highest capillary bound water content (57.52%). In general, the capillary bound water content of marine-continental transitional shale in the Shan 23 Submember of the study area is high, ranging from 39.96% to 57.52%. 3) Based on pore fluid flow capacity, shale pores are divided into movable pores, bound pores and immovable pores. The Middle shale and the Lower shale have high movable pores, with the porosity ratio up to 27%, and the lower limit of exploitable pore size is 10 nm. The movable pore content of upper shale is 25%, and the lower limit of pore size is 12.6 nm. It is suggested that the Lower and Middle shales have more development potential under the associated development technology.

Marine-continental transitional facies shale is an important field of unconventional oil and gas exploration in China, which accounts for 25% of shale gas resources in China (Kuang et al., 2020). It has a wide distribution area and great resource potential (Yang et al., 2017). However, the exploration, development and geological evaluation of marine-continental transitional facies shale gas are still in the initial stage and require further improvement (Zhang et al., 2018; Dong et al., 2021). The nanoscale pore structure has been identified as one of the most important mechanisms to affect hydrocarbon recovery from unconventional shale reservoirs (Chen et al., 2018; Han et al., 2021). Understanding nanoscale pore structure and its controlling factors is beneficial for shale reservoir evaluation. A large number of pore structure studies have been carried out on marine shale and found that nanoscale pore structure is strongly affected by mineral composition and organic matter abundance (Li et al., 2016; Jia et al., 2020). However, due to the huge difference in sediment composition, mineral composition and organic matter abundance between transitional shale and marine shale (Jia et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022), the previous results of marine shale cannot be directly applied to transitional shale. The existence of pore water in shale reservoir will affect the adsorption capacity and flow capacity of shale gas to a great extent, which brings some difficulties to the evaluation of gas reservoir resources and the prediction of productivity (Zhang et al., 2022a; Xi et al., 2022). Therefore, the research on the prediction shale gas adsorption capacity and flow capacity under the condition of reservoir water cut is of great significance to the formulation of gas field development plan and the evaluation of development potential (Li et al., 2018). Therefore, it is of great significance for exploration evaluation and development plan-making to clarify different pore fluid characteristics. However, previous studies on transitional facies shale focus on the characteristics of shale gas reservoirs such as TOC content, mineral composition, pore type and gas content (Li et al., 2019). Meanwhile, many studies have been carried out on the sedimentary environment, sedimentary model and pore structure of transitional facies shale (Xi et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2018; Xi et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022), but systematic studies on pore fluid of shale pore system is rare. In this study, the effective pore size distribution is determined by dividing the fluid types in the pores, and the systematic evaluation of the transitional shale pores in the study area is realized, which also provides a new idea for the effectiveness evaluation of transitional shale reservoirs.

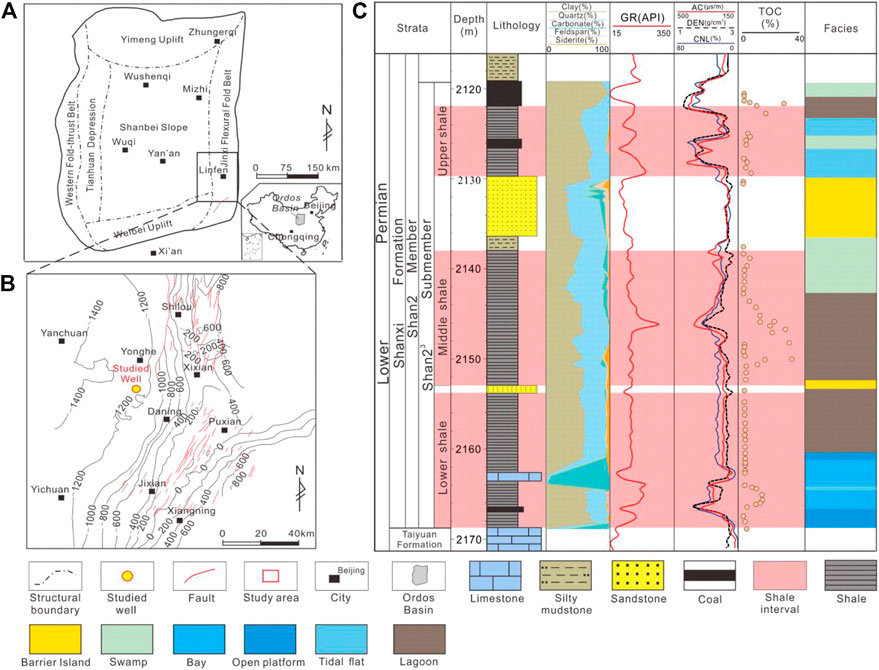

The Ordos Basin is a typical craton basin in the western part of the North China Block (Figure 1A), and the basin area is about 370,000 km2 (Zhang et al., 2021). The Ordos Basin comprises of six structural units, including Tianhuan Depression, Western Fold-Thrust Belt, Yimeng Uplift, Jinxi Flexural Fold Belt, Shenbei Slope and Weibei Uplift (Gu et al., 2022).

FIGURE 1. (A) Location of study area, North China. (B) Distribution map showing the burial depth of Shan 23 Submember transitional shale. (C) Vertical distribution of Shan 23 Submember transitional shale in the studied well (Facies is modified according to Zhang et al., 2021).

The study area, with an area of 4.5 × 104 km2, is located in the Southeastern Ordos Basin, and the studied well is located in Central part of the study area (Figure 1B). From Late Carboniferous to Early Permian Shanxi Formation period, the Ordos Basin enters the subsidence period, and a large area of transgression occurs, which is dominated by marine-continental transitional facies deposits, forming thick organic-rich marine-continental transitional shale (Chen et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2021). Until the Middle Permian Shihezi period, the Ordos Basin entered continental sedimentary evolution stage (Figure 1C).

The Shanxi Formation consist of Shan 1 Member and Shan 2 Member, and Shan 2 Member consist of three submembers: Shan 21, Shan 22 and Shan 23. During the sedimentary period of Shanxi Formation, the sedimentary environment in the study area changed rapidly due to the frequent changes in sea level, which mainly formed the Bay facies, Lagoon facies, Tidal flat facies, Swamp facies and Delta facies. The thick organic-riched black shales deposited in Bays and Lagoons are the main intervals for the breakthrough of marine-continental transitional shales in China (Zhang et al., 2021; Gu et al., 2022). Three sets of transitional shale developed in Shan 23 Submember: Lower shale, Middle shale and Upper shale (Figure 1C). Organic rich shale intervals are developed in the middle shale and the lower shale, which are formed in Lagoon and Bay facies respectively.

A total of seventy-nine shale samples were obtained from the Shan 23 Submember of studied well in the Eastern Ordos Basin. TOC of all samples, mineral composition of thirty-three samples, porosity testing of 16 samples, and in-situ gas content of fourteen samples have been collected to characterize the macro-characteristics of the shale reservoir. Four shale samples were selected to carry out NMR tests under different centrifugation and drying conditions to characterize the fluid occurrence characteristics.

The four plug samples were first dried at 110°C for 24 h to remove residual moisture in the samples. After 12 h of vacuum degassing, the samples were saturated with high-purity distilled water at a pressure of 25 MPa for 2 days. After the saturation was completed, the sample was taken out, and the NMR T2 spectrum was tested after standing in the saturated fluid for 12 h. In order to reflect the occurrence characteristics of different types of fluids, two groups of parallel plug samples saturated with water were treated with different centrifugation speeds and drying temperatures, and nuclear magnetic resonance tests were performed after each centrifugation and drying. The centrifugation time of each sample is fixed at 30 min, and the drying time is fixed at 24 h.

The NMR test parameters are as follows: the echo interval (TE) is .055 ms, the number of echoes is 12,000, the cumulative sampling times (NS) is 64 times, and the waiting time (TW) is 4,000 ms. The experimental instrument is the NMRC012V nuclear magnetic resonance instrument produced by Suzhou Niumag Company, China.

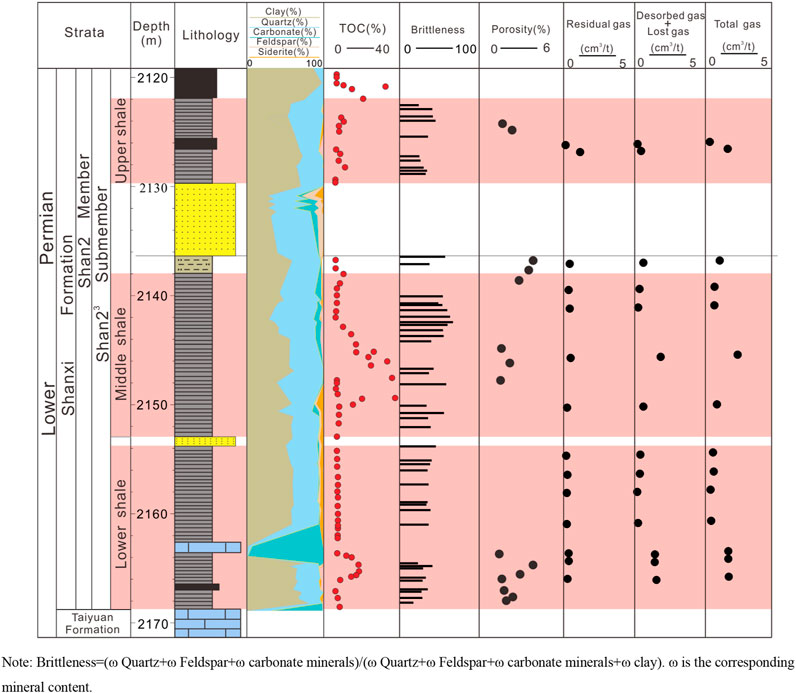

The TOC content of the Shan 23 transitional shale of the studied well is unstable in the vertical direction, and the TOC content has obvious changes (Figure 2). The TOC content of the Lower shale and the Middle shale varies widely. The TOC content of the Lower shale ranges from .32% to 26.6%, with an average of 3.37%, and the TOC content of the Middle shale ranges from .07% to 43.9%, with an average of 6.87%. The range of TOC content in the Upper shale is narrow and the content is low, ranging from .97% to 4.11%, with an average of 2.3% (Table 1). The average vitrinite reflectance of the Upper, Middle and Lower shales is 2.4, 2.73 and 2.46, respectively, all exceeding 2.0, indicating that the shale has entered the dry gas generation stage (Zhang et al., 2022b; Zhang et al., 2022c). Although the organic matter type of transitional shale is mainly type III, the rich organic matter content and high thermal maturity make it still have high hydrocarbon generation capacity (Qiu et al., 2021).

FIGURE 2. Vertical variability of TOC, mineral composition, brittleness, porosity and gas content of studied well.

Mineral composition affects the adsorption capacity of shale reservoirs (Fan et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022). Brittle minerals also determine the transformability of shale to a certain extent, so mineral composition is important for shale gas exploration and development (Ross and Marc Bustin, 2009). The mineral composition of Shan 23 transitional shale is mainly quartz and clay, more than 90%, in addition to a small amount of carbonate minerals, pyrite and siderite (Figure 2). The quartz content of the Middle shale is the highest, ranging from 29.3% to 59.7%, with an average of 46.8%. The quartz content of the Upper shale and the Lower shale is narrow, ranging from 25.1% to 47.0% (average 31.7%) and 31.7%–37.3% (average 34.4%), respectively. Most of the samples have high clay content. The clay content of the Middle shale is distributed from 28.8% to 60.6%, with an average of 44.2%, while the average clay mineral content of the Upper and Lower shale is 63.9% and 58.9%, respectively. The average content of quartz minerals in these three sets of shale is less than 50%, and the content of clay is high, which reflects that the overall fracturing ability of the transitional shale in Shan 23 is low.

The brittleness index calculation formula commonly used in shale in North America is: brittleness index = quartz/(quartz + calcite + clay mineral) × 100% (Yu et al., 2020; Li, 2022). Due to the complex mineral composition of transitional shale, the modified brittleness index calculation formula is adopted: brittleness index = (quartz + calcite + feldspar)/(quartz + calcite + feldspar + clay mineral). The brittleness index of the Middle shale is the highest, ranging from 35.28 to 69.8, with an average of 52.3, reflecting the relatively strong ability of fracturing. The brittleness index of the lower shale is between 18.09 and 47.44, with an average of 35.1, but there is a limestone interlayer in the lower shale. Considering the fracability of limestone, the lower shale still has a strong ability to be fractured. The brittleness index of the Upper shale is 2.26–68.12, with an average of 33.12, and the fracability is poor.

Porosity is the main index to evaluate the storage capacity of shale reservoirs. The average porosity of the three sets of shale in this study is small. The average porosity of the Middle and Lower shale is 2.34% and 2.04% respectively, and the Upper shale porosity is low, with an average of 1.87%. The porosity of most samples is less than 2%, but the porosity of shale in the high TOC range is up to 4% (Figure 2), with strong self-generation and self-storage capacity.

The in-situ total gas content of the Upper, Middle and Lower shales is distributed in .4–1.57 m3/t (average .99 m3/t), .7–2.22 m3/t (average 1.11 m3/t), .45–1.64 m3/t (average 1.01 m3/t), respectively (Figure 2). In general, the contents of residual gas, lost gas and desorbed gas in the Middle shale are distributed in .16–.33 m3/t (average .29 m3/t), .2–.65 m3/t (average .38 m3/t), .27–1.19 m3/t (average .43 m3/t). The contents of residual gas, lost gas and desorbed gas in the Upper shale are distributed in .06–1.01 m3/t (average .54 m3/t), .22–.53 m3/t (average .38 m3/t), .11–.69 m3/t (average .4 m3/t). The contents of residual gas, lost gas and desorbed gas in the Lower shale are distributed in .1–.31 m3/t (average .2 m3/t), .12–.41 m3/t (average .28 m3/t), .19–1.05 m3/t (average .54 m3/t). Residual gas, lost gas, desorbed gas content ratio and comparative analysis can qualitatively reflect the relative effective porosity and permeability, and to a certain extent, reflect the reservoir quality (Ghosh et al., 2022). The total gas content of the Middle and Lower shale is high, and the content of lost gas and desorbed gas accounts for 80% of the total gas content, reflecting the high reservoir quality.

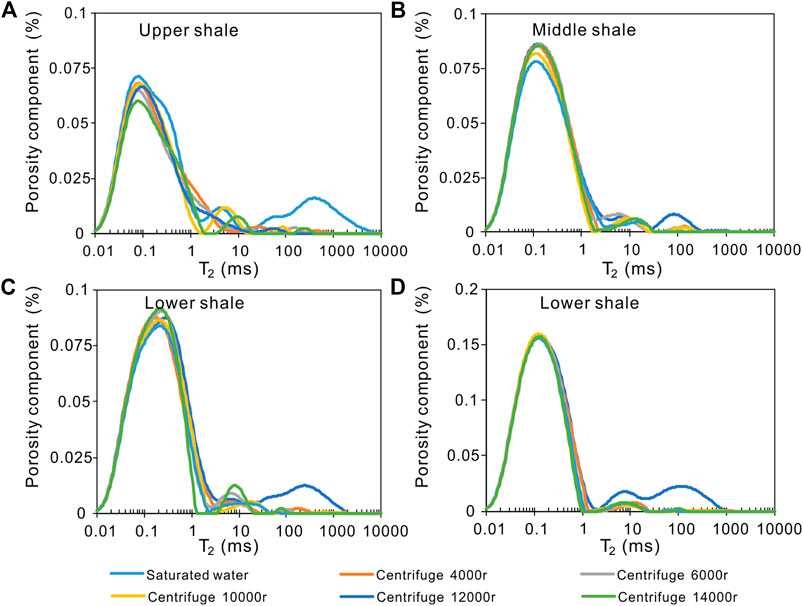

The NMR T2 spectra of 4 samples in saturated water showed three peaks, with the main peak of the upper shale less than .1 m and the main peak of the lower shale and central shale at .2 m (Figure 3). The second peak of the Upper shale is distributed in 1–10 ms, and the third peak is distributed in 100–1,000 ms. The second and third peaks of the Middle and Lower shale are distributed in 2–20 ms and 20–1,000 ms, respectively, indicating that the Middle and Lower shale have larger pore size distribution. All samples show that the first peak signal is the highest, and its porosity component accounts for more than 70% of the total porosity, indicating that the small pores of shale are more developed, and there are a small number of large pores and microfractures.

FIGURE 3. NMR T2 spectra of Shan 23 Submember transitional shale under different centrifugation conditions.

Compared with the NMR T2 spectrum of saturated water, the centrifuged NMR T2 spectrum helps to analyze the flow and distribution of fluids in rock pores, thus distinguishing between movable and bound fluids. Figure 3 is the nuclear magnetic resonance T2 spectrum of saturated water samples after centrifugation at different speeds. With the increase of centrifugal speed, the main peak of NMR T2 spectrum of each sample changed little, but the long relaxation peaks decreased obviously. When the centrifugal speed increased to 4,000 rpm, the NMR porosity decreased by an average of nearly 2% (Figure 4). The change of NMR T2 spectrum is the most obvious, and the long relaxation peak of each sample basically disappears, reflecting that the water in macropores or microfractures is discharged from pores under the action of centrifugal force. As the centrifugal speed continues to increase, when the centrifugal speed reaches 12,000 rpm, the second peak begins to decrease slightly, and the porosity decreases by an average of .2%. After the centrifugal speed increased to 14,000 rpm, NMR T2 spectrum and NMR porosity did not change, at this time the water in the macropores or micro-cracks is basically discharged. Centrifugal process, movable water is preferentially discharged, but a large amount of water remains in the pores, in addition to the Upper shale, other samples NMR porosity of more than 4%.

FIGURE 4. NMR porosity changes of Shan 23 Submember transitional shale under different centrifugation and drying conditions.

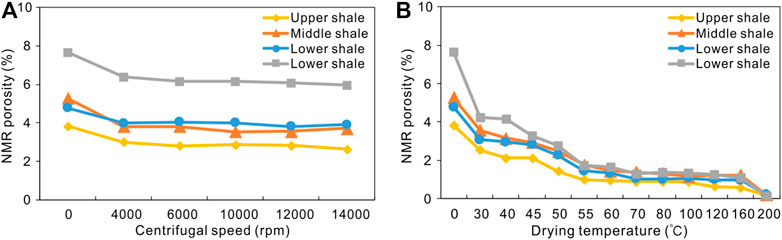

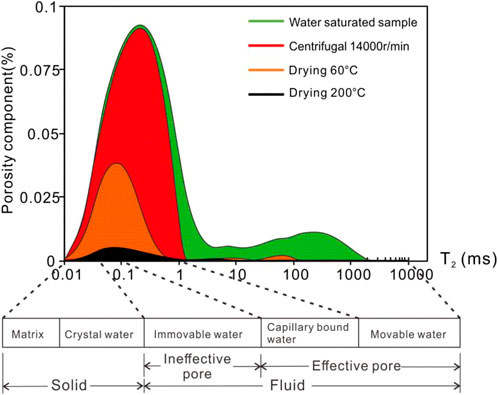

Testamanti and Rezaee (2017) proposed that centrifugation can only remove the easily flowing water in macropores and microfractures. Centrifugal experiments cannot provide sufficient capillary pressure to remove the flowing water in the matrix. Therefore, Testamanti and Rezaee (2017) proposed to obtain capillary bound water and clay bound water content in shale by variable temperature drying. With the increase of drying temperature, the NMR porosity of shale samples has a significant linear relationship with the rising temperature, and it has segmentation, and the slopes of the three sections are obviously different (Figure 4B). Because the minimum capillary force required to expel different types of fluid is very different, the slope changes significantly when the type of fluid being drained changes. The first stage is the evaporation of movable water at a relatively large rate, and the temperature threshold is 40°C. The second stage is the evaporation of capillary bound water at a uniform speed, and the temperature threshold is 60°C; the third stage is when the temperature is higher (more than 160°C), the clay bound water in the pore begins to evaporate (Figure 4B).

Figure 5 shows the T2 spectrum changes of saturated water samples at different drying temperatures. With the increase of drying temperature, the T2 spectrum of all samples first showed that the long relaxation peak disappeared, then the short relaxation peak decreased, and the main peak shifted to the left obviously. Finally, the T2 spectrum of all samples showed a single peak with a main peak of .1 ms. When the drying temperature reaches 40°C, the long relaxation peaks of all samples basically disappear, which is consistent with the centrifugal process, and the movable water in the macropores and microcracks discharges the rock. The NMR porosity after drying at 40°C is 1% lower than that after centrifugation. This may be because the drying process enhances the mobility of water molecules, so the water in the pores of the second peak migrates to the macropores, so the water loss is slightly more. When the drying temperature increased to 60°C, the NMR porosity of each sample decreased significantly. The NMR porosity of the four saturated water samples decreased by an average of 4% (Figure 4B), and the capillary bound water evaporated until it was completely lost. When the drying temperature exceeds 160°C, the NMR porosity decreases rapidly again, and the clay bound water begins to evaporate.

NMR experiments based on high-speed centrifugation and drying at gradient temperatures are an effective method for classifying pore fluid types and determining the relative content of mobile and bound fluids (Testamanti and Rezaee, 2017). The water loss in the sample after centrifugation at 14,000 rpm is movable water. After drying at 60°C, the capillary bound water in the matrix pores is also basically removed. The water loss in the sample after drying at 160°C can be approximated as clay bound water. The remaining signal is derived from the unremoved matrix signal. The calculation formulas of various types of fluids are as follows:

S1, S2, S3 and S4 are movable water saturation, capillary bound water saturation, clay bound water saturation and matrix content respectively. Tc1, Tc2, and Tc3 are the cutoff values between movable water and capillary bound water, between capillary bound water and clay bound water, and between clay bound water and base signal, respectively. The method for determining the T2 cutoff value of shale samples is shown in Figure 6. First, the T2 spectrum of four states was obtained, namely saturated water, 14,000 rpm centrifugation, 60°C drying and 200°C drying. Then the T2 spectrum is converted into the cumulative spectrum of NMR porosity and displayed in the same map. The Tc1, Tc2 and Tc3 are determined by the projection process.

Table 2 shows T2 cut-off values for four samples and calculated saturation for different types of fluids. After comparing different fluid saturations, it is suggested that the most abundant shale fluid is capillary bound water, which is 39.96%–57.52%. This part of the fluid needs good fracturing effect to be exploited. The movable water has strong flowing ability and low mining difficulty, and its content is distributed in 20.46%–32.58%. Among the three sets of shale, the Middle shale has the highest movable water content of 32.58% and the lowest capillary bound water content of 39.96%. The Lower shale has the highest capillary bound water content (maximum 57.52%), but the movable water content is low, with an average of 20.52%.

There is a certain positive correlation between T2 time and shale pore size, and the full pore size distribution of rock samples can be characterized by nuclear magnetic resonance experiment (Chen et al., 2021). According to the method (Chen et al., 2021), the NMR relaxation rate of each sample can be obtained by comparing the full pore size distribution curve of shale with the T2 spectrum, and then the Tc1, Tc2, and Tc3 of all samples are converted to the corresponding pore sizes rc1, rc2, and rc3, respectively (Table 3).

Under formation conditions, the space occupied by clay bound water cannot be filled by gas, so Tc2 can be used as the minimum pore size limit for shale gas development. The lower limit of pore diameter of Middle shale and Lower shale is 10 nm, and the lower limit of pore diameter of Upper shale is 12.6 nm. According to the occurrence characteristics of fluid and the possible difficulty of mining, shale pores can be divided into movable pores, bound pores and immovable pores (Figure 7). The results show that the Middle shale and the Lower shale have high movable pores, and the proportion of pores can reach 27%, while that in the Upper shale is lower, which is 25%. In addition, the total content of movable pores and bound pores in the Lower shale is the highest, which is 78.61% (Table 3). It is suggested that the Lower and Middle shales may have more development potential under the associated development technology.

FIGURE 7. Pore fluid distribution characteristics and pore type classification of transitional shale.

(1) Three sets of organic-rich transitional shale intervals (Lower shale, Middle shale and Upper shale) developed in Shan 23 Submember of Shanxi Formation. The average TOC content of the Middle shale and the Lower shale is 6.87% and 3.37% respectively, the average porosity is 2.34% and 2.04% respectively, and the average total gas content is 1.11 and 1.01 m3/t respectively. The reservoir quality is better than that of the Upper shale. The average vitrinite reflectance results all belong to the dry gas generation stage.

(2) NMR experiments with high speed centrifugation and gradual temperature drying are effective methods to classify pore fluid types and determine the relative content of movable fluid and bound fluid. The Middle shale has the highest movable water content (32.58%) and the lowest capillary bound water content (39.96%). The Lower shale has the highest capillary bound water content, up to 57.52%.

(3) Based on the flow capacity of pore fluid, shale pores are divided into movable pores, bound pores and immovable pores, so as to realize the systematic evaluation of the pores of sea land transitional shale in the study area. The results show that the Middle shale and the Lower shale have high movable pores, and the proportion of pores can reach 27%. In addition, the total content of movable pores and bound pores in the Lower shale is the highest, which is 78.61%. The movable pores in the Upper shale is lower, which is 25%. It is suggested that the Lower and Middle shales may have more development potential under the associated development technology.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

GC contributed as the major author of the article. XX, XL, and XS conceived the project. JN, YG, FO, and YF collected the samples. YJ analyzed the samples. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by the Science and Technology Cooperation Project of the CNPC-SWPU Innovation Alliance (Grant No. 2020CX030101).

Authors XX, XL, and XS were employed by PetroChina Coalbed Methane Company. Authors JN and FO were employed by PetroChina Southwest Oil and Gas field Company.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Chen, D., Zhang, J., Wang, X., Lan, B., Li, Z., and Liu, T. (2018). Characteristics of lacustrine shale reservoir and its effect on methane adsorption capacity in fuxin basin. Energy & Fuels 32 (11), 11105–11117. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.8b01683

Chen, H., Li, J., Zhang, C., Cheng, L., and Cheng, L. (2011). Discussion of sedimentary environment and its geological enlightenment of Shanxi Formation in Ordos Basin. Acta Petrol. Sin. 27 (8), 2213–2229.

Chen, Y., Jiang, C., Leung, J. Y., Wojtanowicz, A. K., and Zhang, D. (2021). Multiscale characterization of shale pore-fracture system: Geological controls on gas transport and pore size classification in shale reservoirs. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 202, 108442. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2021.108442

Dong, D., Qiu, Z., Zhang, L., Li, S., Zhang, Q., Li, X., et al. (2021). Progress on sedimentology of transitional facies shales and new discoveries of shale gas. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 39 (1), 28–44. doi:10.14027/j.issn.1000-0550.2021.002

Fan, C., Li, H., Qin, Q., He, S., and Zhong, C. (2020). Geological conditions and exploration potential of shale gas reservoir in Wufeng and Longmaxi Formation of southeastern Sichuan Basin, China. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 191, 107138. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2020.107138

Fan, C., Xie, H., Li, H., Zhao, S., Shi, X., Liu, J., et al. (2022). Complicated fault characterization and its influence on shale gas preservation in the southern margin of the Sichuan Basin, China. Lithosphere 2022, 8035106. doi:10.2113/2022/8035106

Ghosh, K. K., Das, K., Bhattacharyya, S., and Ramteke, C. P. (2022). Characterization of shale gas reservoir of lower gondwana litho-assemblage at mohuda sub-basin, jharia coalfield, Jharkhand, India. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 97, 104316. doi:10.1016/j.jngse.2021.104316

Gu, Y., Li, X., Qi, L., Li, S., Jiang, Y., Fu, Y., et al. (2022). Sedimentology and geochemistry of the lower permian Shanxi Formation Shan 23 submember transitional shale, eastern Ordos Basin, north China. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 859845. doi:10.3389/feart.2022.859845

Han, H., Dai, J., Guo, C., Zhong, N., Pang, P., Ding, Z., et al. (2021). Pore characteristics and factors controlling lacustrine shales from the upper cretaceous qingshankou formation of the songliao basin, Northeast China: A study combining SEM, low-temperature gas adsorption and MICP experiments. Acta Geol. Sin. Engl. Ed. 95 (2), 585–601. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.14419

Jia, A., Hu, D., He, S., Guo, X., Hou, Y., Wang, T., et al. (2020). Variations of pore structure in organic-rich shales with different lithofacies from the jiangdong Block, fuling shale gas field, SW China: Insights into gas storage and pore evolution. Energy & Fuels 34, 12457–12475. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c02529

Kuang, L., Dong, D., He, W., Wen, S., Sun, S., Li, S., et al. (2020). Geological characteristics and development potential of transitional shale gas in the east margin of the Ordos Basin, NW China. Petroleum Explor. Dev. 47 (3), 471–482. doi:10.1016/S1876-3804(20)60066-0

Li, H. (2022). Research progress on evaluation methods and factors influencing shale brittleness: A review. Energy Rep. 8, 4344–4358. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.03.120

Li, J., Chen, Z., Li, X., Wang, X., Wu, K., Feng, D., et al. (2018). A quantitative research of water distribution characteristics inside shale and clay nanopores. Sci. Sin. Tech. 48, 1219–1233. doi:10.1360/N092017-00137

Li, J., Li, H., Yang, C., Wu, Y., Gao, Z., and Jiang, S. (2022). Geological characteristics and controlling factors of deep shale gas enrichment of the Wufeng-Longmaxi Formation in the southern Sichuan Basin, China. Lithosphere 2022 (Special 12), 4737801. doi:10.2113/2022/4737801

Li, Y., Yang, J., Pan, Z., Meng, S., Wang, K., and Niu, X. (2019). Unconventional natural gas accumulations in stacked deposits: A discussion of upper paleozoic coal-bearing strata in the east margin of the Ordos Basin, China. Acta Geol. Sin. Engl. Ed. 93 (1), 111–129. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.13767

Liang, Q., Tian, J., Zhang, X., Sun, X., and Yang, C. (2020). Elemental geochemical characteristics of lower—middle permian mudstones in taikang uplift, southern north China basin: Implications for the four-paleo conditions. Geosciences J. 24 (1), 17–33. doi:10.1007/s12303-019-0008-9

Liang, Q., Zhang, X., Tian, J., Sun, X., and Chang, H. (2018). Geological and geochemical characteristics of marine-continental transitional shale from the lower permian taiyuan formation, taikang uplift, southern north China basin. Mar. Petroleum Geol. 98, 229–242. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.08.027

Liu, S., Wu, C., Li, T., and Wang, H. (2018). Multiple geochemical proxies controlling the organic matter accumulation of the marine-continental transitional shale: A case study of the upper permian longtan formation, Western guizhou, China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 56, 152–165. doi:10.1016/j.jngse.2018.06.007

Luo, W., Hou, M., Liu, X., Huang, S., Chao, H., Zhang, R., et al. (2018). Geological and geochemical characteristics of marine-continental transitional shale from the Upper Permian Longtan formation, Northwestern Guizhou, China. Mar. Petroleum Geol. 89, 58–67. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2017.06.029

Qiu, Z., Song, D., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q., Zhao, Q., Wang, Y., et al. (2021). The geochemical and pore characteristics of a typical marine–continental transitional gas shale: A case study of the permian Shanxi Formation on the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin. Energy Rep. 7, 3726–3736. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.06.056

Ross, D. J. K., and Marc Bustin, R. (2009). The importance of shale composition and pore structure upon gas storage potential of shale gas reservoirs. Mar. Petroleum Geol. 26, 916–927. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2008.06.004

Testamanti, M. N., and Rezaee, R. (2017). Determination of NMR T2 cut-off for clay bound water in shales: A case study of carynginia formation, perth basin, western Australia. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 149, 497–503. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2016.10.066

Wang, Z., Guo, B., Jiang, C., Qi, L., Jiang, Y., Gu, Y., et al. (2022). Nanoscale pore characteristics of the lower permian Shanxi Formation transitional facies shale, eastern Ordos Basin, north China. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 842955. doi:10.3389/feart.2022.842955

Wu, J., Wang, H., Shi, Z., Wang, Q., Zhao, Q., Dong, D., et al. (2021). Favorable lithofacies types and Genesis of marine-continental transitional black shale: A case study of permian Shanxi Formation in the eastern margin of Ordos Basin, NW China. Petroleum Explor. Dev. 48 (6), 1315–1328. doi:10.1016/S1876-3804(21)60289-6

Xi, Z., Tang, S., Wang, J., Yang, G., and Li, L. (2018200). Formation and development of pore structure in marine-continental transitional shale from northern China across a maturation gradient: Insights from gas adsorption and mercury intrusion. Int. J. Coal Geol. 200, 87–102. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2018.10.005

Xi, Z., Tang, S., Zhang, S., Lash, G. G., and Ye, Y. (2022). Controls of marine shale gas accumulation in the eastern periphery of the Sichuan Basin, South China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 251, 103939. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2022.103939

Xi, Z., Tang, S., Zhang, S., and Sun, K. (2017). Pore structure characteristics of marine–continental transitional shale: A case study in the qinshui basin, China. Energy & Fuels 31, 7854–7866. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b00911

Yang, C., Zhang, J., Tang, X., Ding, J., Zhao, Q., Dang, W., et al. (2017). Comparative study on micro-pore structure of marine, terrestrial, and transitional shales in key areas, China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 171, 76–92. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2016.12.001

Yu, K., Gan, Y., Ju, Y., and Shao, C. (2020). Influence of sedimentary environment on the brittleness of coal-bearing shale: Evidence from geochemistry and micropetrology. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 185, 106603. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2019.106603

Zhang, J., Li, X., Zhang, X., Zhang, M., Cong, G., Zhang, G., et al. (2018). Geochemical and geological characterization of marine-continental transitional shales from Longtan Formation in Yangtze area, South China. Mar. Petroleum Geol. 96, 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.05.020

Zhang, K., Jiang, S., Zhao, R., Wang, P., Jia, C., and Song, Y. (2022c). Connectivity of organic matter pores in the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation shale, Sichuan Basin, Southern China: Analyses from helium ion microscope and focused ion beam scanning electron microscope. Geol. J. 57, 1912–1924. doi:10.1002/gj.4387

Zhang, K., Jiang, Z., Song, Y., Jia, C., Yuan, X., Wang, X., et al. (2022a). Quantitative characterization for pore connectivity, pore wettability, and shale oil mobility of terrestrial shale with different lithofacies-A case study of the Jurassic Lianggaoshan Formation in the Southeast Sichuan Basin of the Upper Yangtze Region in Southern China. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 864189. doi:10.3389/feart.2022.864189

Zhang, K., Song, Y., Jia, C., Jiang, Z., Han, F., Wang, P., et al. (2022b). Formation mechanism of the sealing capacity of the roof and floor strata of marine organic-rich shale and shale itself, and its influence on the characteristics of shale gas and organic matter pore development. Mar. Petroleum Geol. 140, 105647. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2022.105647

Zhang, L., Dong, D., Qiu, Z., Wu, C., Zhang, Q., Wang, Y., et al. (2021). Sedimentology and geochemistry of Carboniferous-Permian marine-continental transitional shales in the eastern Ordos Basin, North China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 571 (1-3), 110389. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110389

Keywords: transitional shale, pore structure, fluid evaluation, upper permian, Shan 23 Submember, Ordos Basin

Citation: Cai G, Gu Y, Xiong X, Li X, Sun X, Ni J, Jiang Y, Fu Y and Ou F (2023) Reservoir characteristics and pore fluid evaluation of Shan 23 Submember transitional shale, eastern Ordos Basin, China: Insights from NMR experiments. Front. Earth Sci. 10:1061211. doi: 10.3389/feart.2022.1061211

Received: 04 October 2022; Accepted: 27 December 2022;

Published: 13 January 2023.

Edited by:

Shuai Yin, Xi’an Shiyou University, ChinaReviewed by:

Caifang Wu, China University of Mining and Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Cai, Gu, Xiong, Li, Sun, Ni, Jiang, Fu and Ou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yifan Gu, eG5zeWd5ZkAxMjYuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.