- 1Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Mohali, Mohali, India

- 2Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, Dehradun, India

The Holocene epoch has witnessed several natural climate variations and these are well encoded in various geological archives. The present biomarker investigation in conjunction with previously published multi-proxy records was applied to reconstruct organic matter (OM) sources forming the peat succession spanning the last 8000 cal yr BP and shift in hydrological conditions from the Kedarnath region, Garhwal Himalaya. Intensified monsoon prevailed from ∼7515 until ∼2300 cal yr BP but with reversal to transient arid period particularly between ∼5200 and ∼3600 cal yr BP as revealed by the variability in n-C23/n-C31, ACL (average chain length of n-alkanes) and Paq (P-aqueous) values. A prolonged arid phase is recognizable during the interval between ∼2200 and ∼370 cal yr BP suggested by the n-alkane proxies. Regional scale heterogeneity in the monsoonal pattern is known in the studied temporal range of mid to late Holocene across the Indian subcontinent that is probably a result of complex climate dynamics, sensitivity of proxies and impact of teleconnections. The biomarker signatures deduced from gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GCMS) analysis are suggestive of a mixed biotic input that includes prokaryotes, Sphagnum spp. and gymnosperm flora. The mid chain alkanes viz. n-C23 and n-C25 denote the presence of typical peat forming Sphagnum moss that preferentially grows in humid and waterlogged conditions. Diterpane marker such as ent-kaurane indicates contribution of gymnosperms, whereas the hopanes are signatures of microbial input. The preservation of organic matter is attributed to little microbial degradation in a largely suboxic depositional environment. Our study strengthens the applicability of organic geochemical proxies for the reconstruction of past climate history and indicates their suitability for use on longer timescales given the high preservation potential of the molecular remains.

Introduction

Peatlands are highly dynamic ecosystems providing diverse ecological niches for a variety of biota and can be utilised to understand the past environmental conditions (Gorham et al., 2003; Chambers et al., 2012; Kumaran et al., 2016; Naafs et al., 2019). Peats form in a specific geomorphological environment mostly concentrated in mid to high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere covering about 2–3% of land surface on Earth (Kayranli et al., 2010; Naafs et al., 2019; Dai et al., 2020). Rapid deposition of clastic sediments facilitates the burial of plant remains in wetlands, such as bogs and fens, resulting into the formation of peat layers through compaction over time (Zhang et al., 2017; Dai et al., 2020). The accumulation and preservation of the decomposed plant matter is a complex interplay of biological, physico-chemical, geomorphological and hydrological processes (Middleton, 1973; Finlayson and Milton, 2016). Most importantly, precipitation is a significant controlling factor in the development of the peat deposits. Increased precipitation (or high groundwater level) is a necessity for the growth of peatlands, whereas drier environmental conditions negatively impact peat ecosystem (Marcisz et al., 2016).

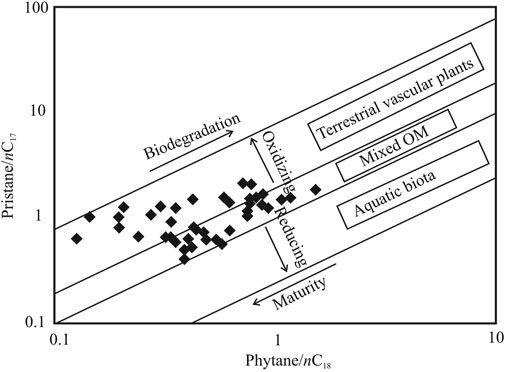

Recent advances in the application of lipid biomarkers have shaped our understanding on key aspects of past ecological and climatic dynamics (Nott et al., 2000; Bingham et al., 2010; Jordan et al., 2017; Baker et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2020). Biomarkers (such as n-alkanes, acyclic and cyclic terpenoids) have been frequently used for biotic and palaeoenvironmental reconstruction in lacustrine and marine settings (Chen and Summons, 2001; Kelly et al., 2011; Dutta et al., 2013; Tulipani et al., 2015; French et al., 2020; Ankit et al., 2021). The n-alkanes and its proxies are widely used to understand the organic source inputs and past environmental conditions (Eglinton and Hamilton, 1967; Eglinton and Eglinton, 2008; Bush and Mclnerney, 2013; Tipple and Pagani, 2013). However, the utilization of biomarkers in peat deposits for understanding the palaeovegetational changes is limited (Ficken et al., 1998; Nott et al., 2000; Pancost et al., 2002; Bingham et al., 2010; Schellekens et al., 2015; Naafs et al., 2019). A variety of peat-forming plants producing distinct carbon chain lengths in the lipid fraction is known (Cranwell, 1973; Ficken et al., 1998; Nott et al., 2000; Bingham et al., 2010). For example, the mid-chain alkanes (n-C23 and n-C25) are dominant components in peat-forming wetland plants, whereas the higher plants on land mainly comprise longer chain lengths such as n-C27, n-C29 and n-C31. Further, the ratio of acyclic terpenoids such as pristane (Pr) and phytane (Ph) (products of chlorophyll side chain of phototrophic organisms) can also be used to understand the redox potential of ambient environment (Didyk et al., 1978; Bechtel et al., 2003). Higher Pr/Ph ratios indicate oxic condition, whereas lower values are suggestive of a reducing environment. Additionally, specific cyclic terpenoids such as hopanoids (derived from prokaryotes) and diterpenoids (produced by gymnosperm vascular plants) are robust tools that specify the organisms contributing into sedimentary organic matter and provide useful information on their habitat (Brocks et al., 2003; Peters et al., 2005).

The Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM) is an important climatic element in the Indian subcontinent and provides the main water resources to the South Asian countries (Benn and Owen, 1998; Kumar et al., 2020). In recent years in the Himalaya, anomalous patterns of extreme rain events have caused huge socio-economic impacts on the human populations. Palaeoclimate studies from the region have utilized multiarchive-multiproxy approach for climate reconstructions (Anoop et al., 2013; Mishra et al., 2015; Bhushan et al., 2018; Kumar et al., 2020; Misra et al., 2020; Rawat et al., 2021). However, only a limited number of studies have targeted peat sediments for understanding the palaeovegetation and environmental and depositional conditions (Phadtare, 2000; Rawat et al., 2015; Srivastava et al., 2017). These studies have used several established climate proxies such as pollen, mineral magnetism, stable isotopes of C, N and elemental geochemistry to reconstruct the Holocene climatic changes. Sedimentary biomarkers that are now established as a strong molecular tool have so far not been explored in Indian Himalaya. Here, we utilize a well-dated peat succession spanning the past 8000 cal yr BP that was previously studied from the Kedarnath region, and analyze the succession for hydrocarbon biomarkers. This allows 1) an opportunity to provide a climate record using an independent proxy and also 2) to analyze how a molecular-based proxy relates and compares to already existing pollen and isotope-based proxy record. We have also compared the monsoonal changes in the Kedarnath region with previous records of variability pattern for clearer perspectives of the complexity of climate dynamics. Our study highlights the excellent applicability of biomarkers in improving the understanding of longer time-scale climatic fluctuations and thus can be utilized to address wider aspects in palaeoclimate research.

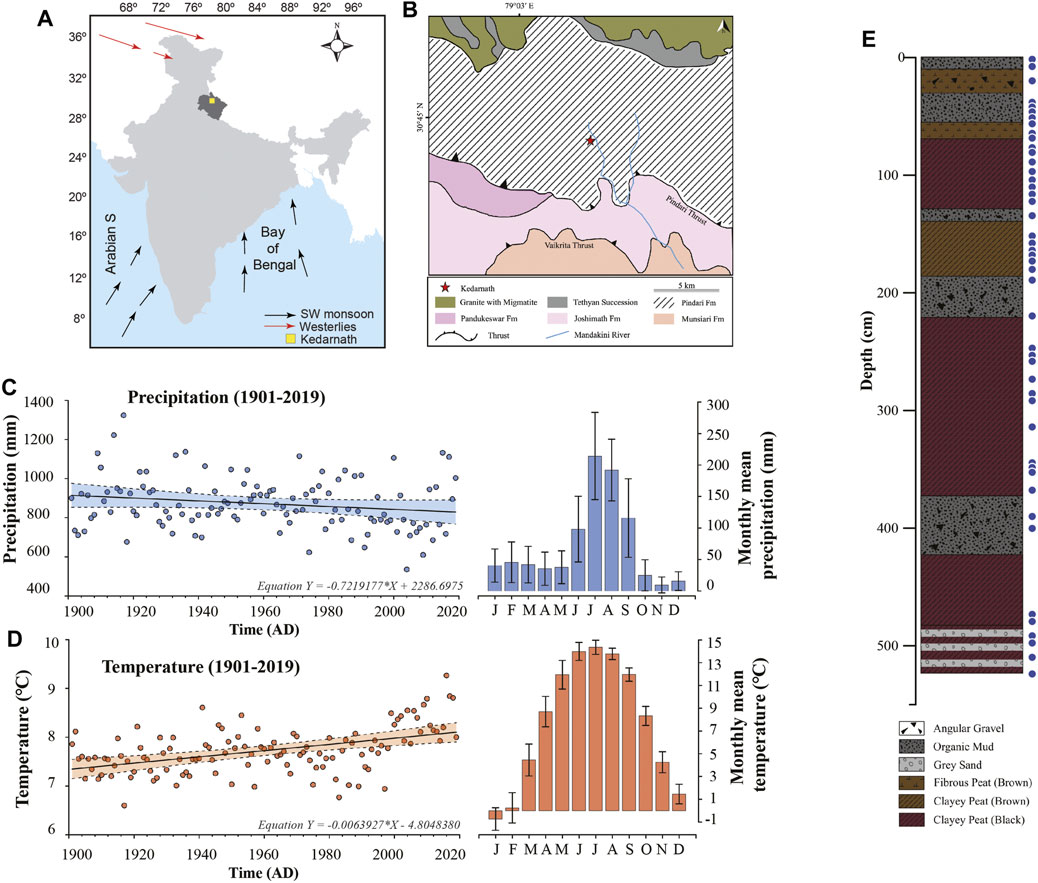

Study Area

The study area (Figures 1A,B) is located at an altitude of 3525 m above mean sea level at northwestern Himalaya in Kedarnath, Uttarakhand, India (30.73°N; 79.07°E) (Srivastava et al., 2017). The region is a climatically sensitive zone located at the periphery domain of the ISM rainfall. The peat succession formed in a glacio-fluvial environment between two lateral moraines close to the Chorabari Glacier and north of the Pindari Thrust. The moraines are the only source of sediments into the depression. Geologically, the region is situated in Pindari formation which is characterized by calc-silicate, schist, and granitic formations (Valdiya et al., 1999) (Figure 1B). The long-term precipitation data of Kedarnath region from Climate Research Unit (CRU TS v4.03) for the period 1901–2019 interpolated into 0.5° latitude/longitude gridded cell (1901–2019) (Harris et al., 2020) shows a decreasing trend with mean precipitation of 7.2 mm per decade (Figure 1C) and an increasing trend in mean temperature (0.06°C per decade) (Figure 1D). The region is typically characterized by a temperate climate (Kar et al., 2016) and receives heavy rainfall during the months of June to September primarily under the influence of the Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM) (∼71% of the mean annual rainfall). Winter precipitation comprises snowfall between the months of December to March due to intensification of the westerly winds. The temperature in the region fluctuates from a freezing −1°C to a maximum of 15°C during the months of June, July and August. The vegetation in the area is dominated by broadleaved species and conifer biota (Kar et al., 2016). Conifers are particularly abundant followed by a few broad-leaved taxa such as Quercus, Alnus and Ulmus. The most prominent herbaceous taxa include Lamiaceae, Rosaceae, Polygonaceae and Rutaceae. Few steppe elements such as Amarantheceae and sub-families of Asteraceae are also well represented (Kar et al., 2016).

FIGURE 1. (A) Location of the study area in the Indian subcontinent. (B) The geological map showing the sampling location of the peat succession in the Kedarnath region of Uttarakhand (marked with the red star). (C) The long term decreasing trend in the mean precipitation in Kedarnath region from Climate Research Unit (CRU TS v4.03) for the period 1901–2019 interpolated into 0.5° latitude/longitude gridded cell. The shaded region represents 99% confidence interval. (D) The long term increasing trend in the mean temperature in Kedarnath region from Climate Research Unit (CRU TS v4.03) for the period 1901–2019 interpolated into 0.5° latitude/longitude gridded cell. The shaded region represents 99% confidence interval. (E) The litho-column depicting the sedimentary layers across the studied depth along with the analyzed samples marked with solid blue circles.

Materials and Methods

Samples

The studied sediments were collected from a ∼5 m long peat succession (Srivastava et al., 2017). The section was dated using radiocarbon dating from seven bulk samples by accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) and the detailed description is provided in the previous study (Srivastava et al., 2017). The 14C dated succession covers the last ∼8,000 years. A total of 46 sediment samples from various time intervals covering the section have been employed for the present biomarker analysis (Figure 1E). A detailed litholog (Figure 1E) depicting the various sedimentary layers of the studied section along with the sampling points is provided.

Sample Processing

The sediments were powdered and homogenized using mortar and pestle. The powdered samples were introduced into the speed extractor (Buchi, E-914) for recovering the soluble fraction of the organic matter (total extract) using a solution of dichloromethane and methanol (9:1 ratio, respectively; v/v) at 100°C and 70 bar pressure. For removing the insoluble polar fraction, n-pentane was added to the total extract and left for 12 h. Upon precipitation of the heavier and primarily unsaturated polar constituents, the supernatant fraction was decanted and dried overnight in fume-hood. Saturated hydrocarbon fractions were isolated using column chromatography (activated silica gel; 100–200 mesh; eluent n-hexane) and analyzed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry

The aliquots of saturated hydrocarbon fraction were dissolved in dichloromethane and analyzed using an Agilent 5977C mass spectrometer interfaced to a 7890B gas chromatograph. The samples were injected by auto sampler in pulsed splitless mode. The GC is equipped with an HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 i.d. × 0.25 μm film thickness). Helium was used as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The analysis was done in full scan mode over a mass range of 40–600 Da. The ion source operated in the electron ionization mode at 70 eV. The initial temperature of the GC oven was programmed to 40°C (isothermal for 5 min) and then ramped to 310°C (isothermal for 5.5 min) at 4°C/min. Data was processed using Mass Hunter software and the compounds were identified by comparing the elution pattern and mass spectra from published literature.

n-Alkane and Terpenoid Proxies

Based on carbon chain lengths, various n-alkane indices have been assessed to understand the possible organic matter sources. The short chain n-alkanes (n-C15–n-C21) are attributed to microbial input such as algae and prokaryotes, whereas higher order terrestrial plants are dominated by the long chain (n-C27–n-C33) homologues (Eglinton and Hamilton, 1967; Eglinton and Eglinton, 2008). The aquatic plants (submerged/floating) and Sphagnum moss species are characterized by a predominance of the mid-chain lengths typically the n-C23 and n-C25 (Ficken et al., 2000).

The n-alkane based indices [carbon preference index (CPI), P-aqueous (Paq) and average chain length (ACL)] have been calculated to characterize the distribution pattern of normal alkanes in the studied Kedarnath sediment samples. The CPI, Paq and ACL are calculated based on the following equations:

CPI is used to understand the origin of hydrocarbon biomarkers and degree of molecular taphonomic alterations post deposition. Generally, CPI values tend to be higher on occasions of heavy influx of terrestrial plant matter and lower when derived from microbial biota such as algae and bacteria (Cranwell et al., 1987; Bulbul et al., 2021). In addition, significant microbial reworking and/or increasing thermal maturity also lower the CPI values. The Paq denotes the relative proportion of submerged, floating and terrestrial biota and can successfully indicate the water level history especially in peat-forming environments (Zhou et al., 2010). The ACL which is the weighted mean of chain lengths is a crucial proxy that reveals the ambient climatic conditions (Sarkar et al., 2014). The underlying principle of ACL is that arid conditions induce increased production of the longer chain n-alkanes in terrestrial plants (Andrae et al., 2019). Other n-alkane ratio such as n-C23/n-C31 has been evaluated to decipher the shift in the biotic input in response to changing environmental conditions. The ratio n-C23/n-C31 is particularly applied to trace the changes in input of Sphagnum vs. non-Sphagnum species into the preserved organic matter in sediments.

Pr/Ph has been used to reconstruct redox potential of the depositional environment (Didyk et al., 1978). The Pr/Ph values are sufficiently high (>3) in oxic environments, whereas values <0.8 pertain to suboxic to reducing conditions. Furthermore, the acyclic terpenoid/n-alkane ratios viz. Pr/n-C17 and Ph/n-C18 are used to explain the relative contributions of aquatic and terrestrial biota and also the biodegradation status since the normal alkanes are generally consumed faster than the terpenoids during microbial degradation thus increasing the Pr/n-C17 and Ph/n-C18 values.

Diterpenoid compound is identified using base peak in the selected ion chromatogram at m/z 123 (Noble et al., 1985) and hopanoids with base peak in the selected ion chromatogram at m/z 191 (Waples and Machihara, 1991; Sessions et al., 2013; Nizar et al., 2021).

Results

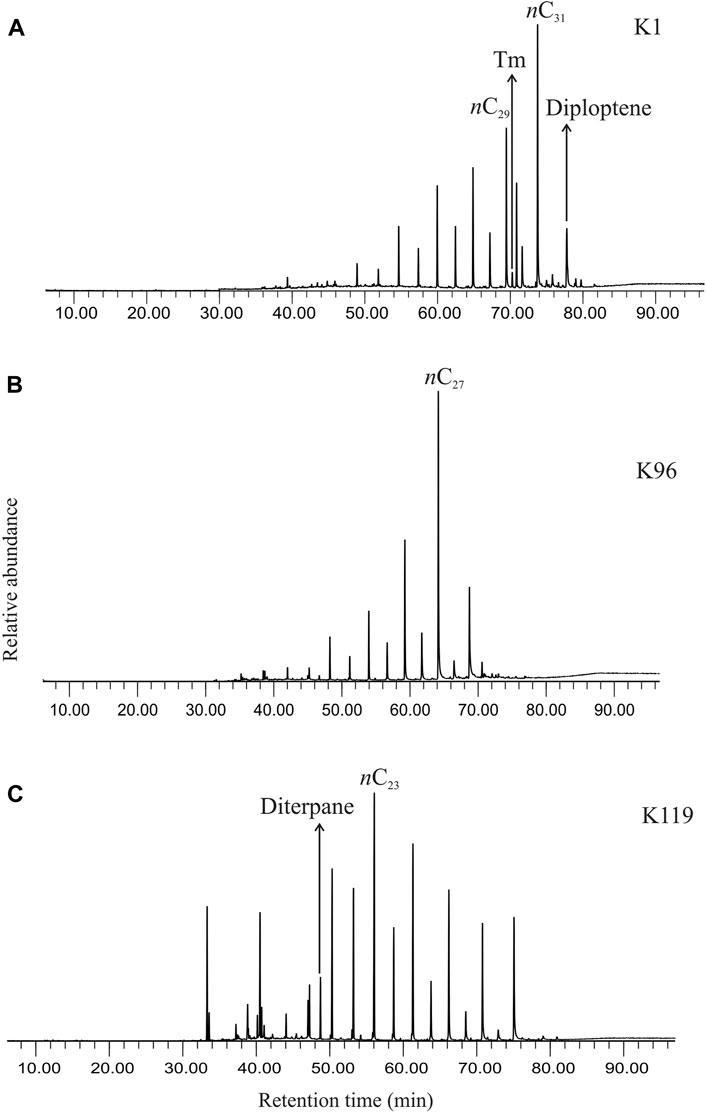

GCMS traces reveal the presence of n-alkanes, acyclic and cyclic terpenoids in the total ion chromatograms (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. (A) Total ion chromatogram showing the distribution of biomarkers, both linear chain and cyclic compounds, in the saturated hydrocarbon fraction extracted from the studied sediment (K1, ∼369 cal yr BP). (B) Total ion chromatogram showing the distribution of biomarkers, both linear chain and cyclic compounds, in the saturated hydrocarbon fraction extracted from the studied sediment (K96, ∼4842 cal yr BP). (C) Total ion chromatogram showing the distribution of biomarkers, both linear chain and cyclic compounds, in the saturated hydrocarbon fraction extracted from the studied sediment (K119, ∼5655 cal yr BP).

n-Alkanes

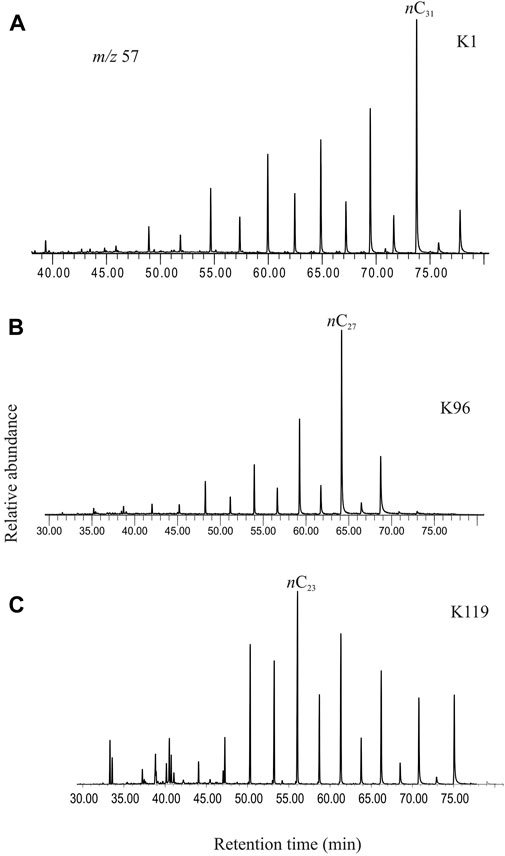

The n-alkanes, detected in selected ion chromatogram at m/z 57, in the saturated hydrocarbon fractions of the studied sediments comprise a homologous series ranging from n-C16 to n-C33 (Figure 3). The short-chain n-alkanes depict a moderate abundance of n-C16, n-C17 and n-C18, whereas n-C27, n-C29 and n-C31 generally dominate the longer-chain range. The mid-chain n-alkanes comprise relatively high abundance of n-C23 and n-C25. The n-alkane series exhibits a bimodal distribution with two distinct centers at n-C16– n-C18 and a dominant n-C23– n-C31 range. A strong odd-over-even carbon predominance is observed in the range of n-C23–n-C31 homologues.

FIGURE 3. (A) Selected ion chromatogram at m/z 57 showing the chain length distributions of the n-alkanes in the saturated hydrocarbon fraction extracted from the studied sediment (K1, ∼369 cal yr BP). (B) Selected ion chromatogram at m/z 57 showing the chain length distributions of the n-alkanes in the saturated hydrocarbon fraction extracted from the studied sediment (K96, ∼4842 cal yr BP). (C) Selected ion chromatogram at m/z 57 showing the chain length distributions of the n-alkanes in the saturated hydrocarbon fraction extracted from the studied sediment (K119, ∼5655 cal yr BP). A clear shift in the predominant chain length in the sediments from different age intervals is observed. The changeover is a clear signature of response of the ambient vegetation to changing climatic conditions.

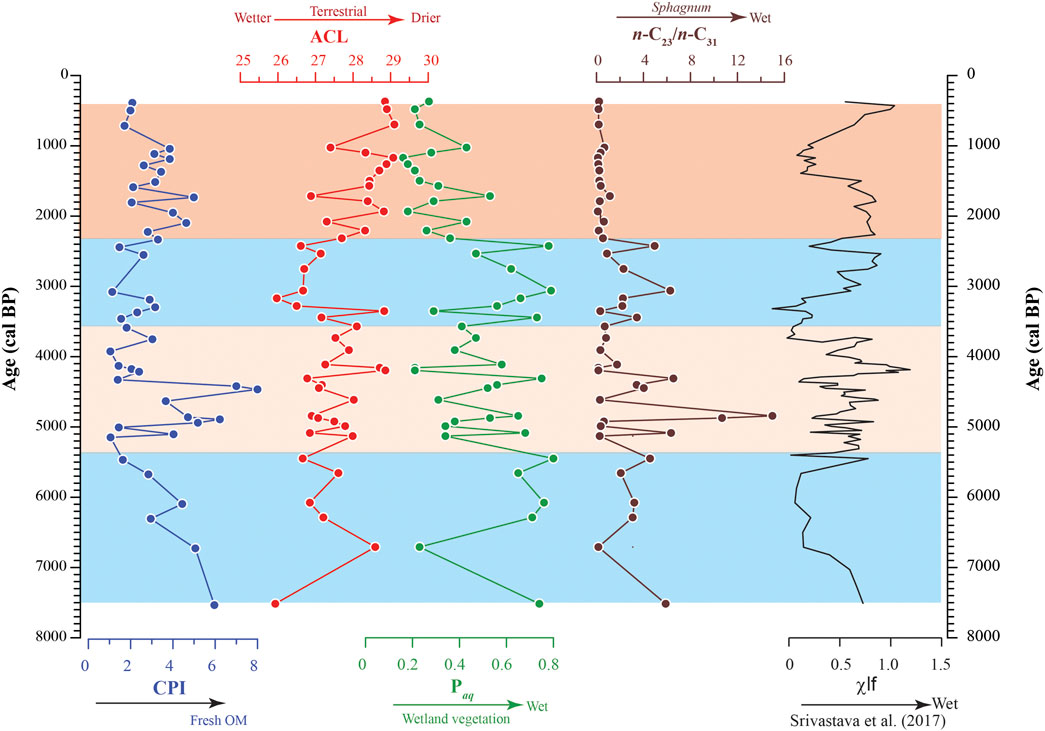

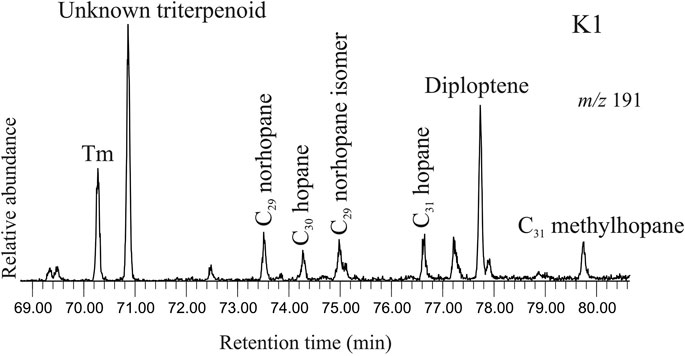

CPI values for the n-C23–n-C29 homologues are characterized by a wide spread ranging between 1.0 and 11.4 and averaging at 3.3 (Figure 4; Table 1). Values are seen to fluctuate throughout the studied succession and no systematic trend could be discerned. However, a short interval between ∼4900 and ∼4400 cal yr BP distinctly displays considerably high CPI values between 3.7 and 8.0 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. The temporal variation of the CPI, ACL, Paq and n-C23/n-C31 across the studied ∼8000 cal yr BP sedimentary succession. The Paq and n-C23/n-C31 reflect the influx of wetland vegetation and ACL indicates wetter or drier hydrological conditions. The palaeohydrological reconstruction by Srivastava et al. (2017) based on multiproxy records has been incorporated on the right representing the changing dry and wet phases across the studied succession as deduced from the previous work.

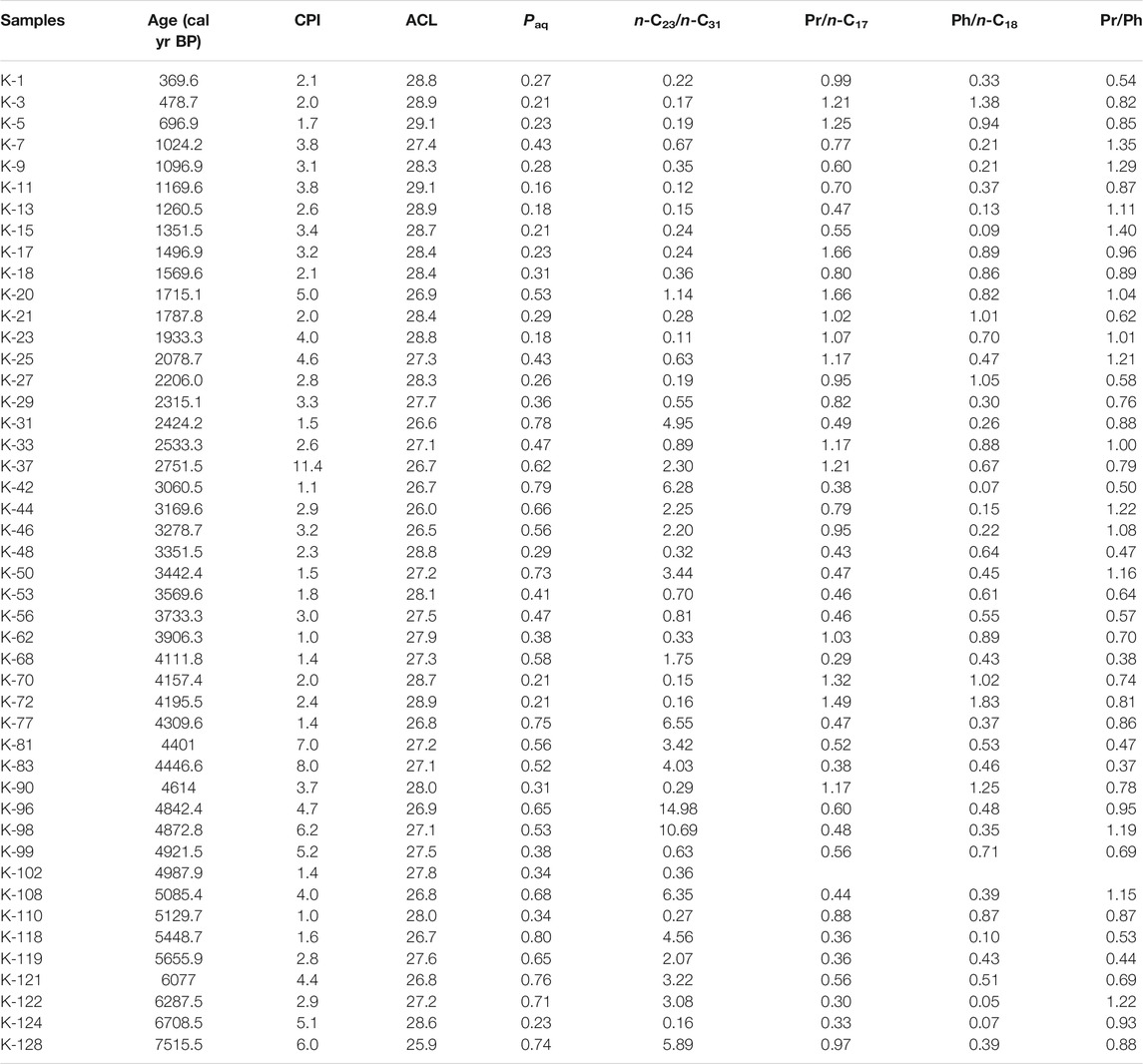

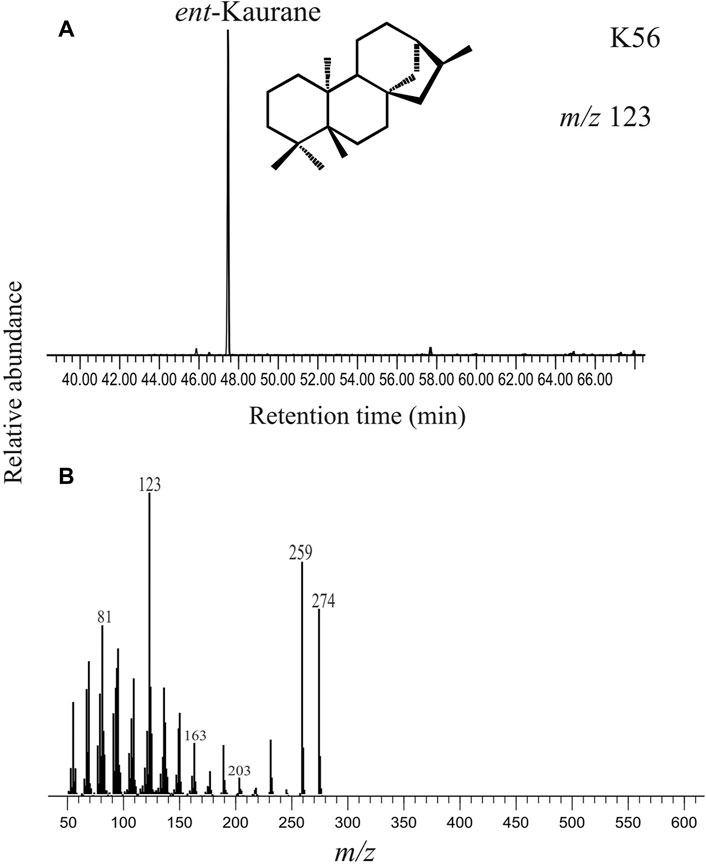

TABLE 1. A list of n-alkane (CPI, ACL, Paq and n-C23/n-C31) and acyclic terpenoid (Pr/n-C17, Ph/n-C18 and Pr/Ph) proxies across the studied sedimentary succession from the Kedarnath region, Garhwal Himalaya.

The ACL values also vary throughout the Kedarnath peat succession between 25.9 and 29.1. Generally, lower values are observed in the interval between ∼7515 and ∼2300 cal yr BP and the ACL fluctuates between 25.9 and 28.9 averaging at 27.3 (Figure 4). In the above-mentioned interval, the temporal range between ∼5300 and ∼3600 cal yr BP shows many minor and short-lived fluctuations (Figure 4). During the period between ∼3600 and ∼2300 cal yr BP, the ACL shows minimum values (between 26.0 and 28.8 with a mean value of 27.1) followed by a sharp increasing trend until ∼370 cal yr BP (between 26.9 and 29.1 and averaging at 28.3) (Figure 4).

Paq is generally characterized by higher values between ∼7515 and ∼2300 cal yr BP varying between 0.21 and 0.80 (averaging at 0.54) and relatively lower values in the range ∼2300 to ∼370 cal yr BP fluctuating between 0.16 and 0.53 (averaging at 0.28). Similar to ACL, fluctuations are clearly discernible in the range between ∼5300 and ∼3600 cal yr BP (Figure 4). Notably, the Paq values exhibit a negative correlation (r = −0.91) with the ACL wherein higher values of ACL are accompanied by lower values of Paq and vice versa in the studied succession.

Another parameter namely the n-C23/n-C31 has been calculated to evaluate the distribution pattern of the n-alkanes. Typically, higher values, with a mean value of 3.10 are observed during the sufficiently long period between ∼7500 and ∼2400 cal yr BP (Figure 4; Table 1). A significant drop in the n-C23/n-C31 ratio values is observed in the range between ∼2300 and ∼370 cal yr BP ranging between 0.11 and 0.67 (mean value 0.35). It is noteworthy that a concomitant decrease in the ACL is also observed during this time interval.

Acyclic Terpenoids

Pristane (Pr) and phytane (Ph), the C19 and C20 acyclic terpenoids, respectively are monitored by selected ion chromatogram at m/z 57 and detected by major fragments at m/z 183 and m/z 197 in the sediment samples. The Pr/Ph ranges between 0.37 and 1.35 with a mean of 0.83. Frequent oscillations in the Pr/Ph are observed over the studied sedimentary section and no distinct trend could be discerned. Similarly, fluctuations are observed for Pr/n-C17 and Ph/n-C18 (Table 1).

Diterpenoids

Diterpane is identified in selected ion chromatogram at m/z 123 in all the sediment samples (Noble et al., 1985). Other major fragments include m/z 231, 259 and 274. Tetracyclic diterpanes such as ent-phyllocladane and ent-kaurane have a very similar mass fragmentogram with major fragments at m/z 231, 259 and 274. However, these two compounds can be readily distinguished by the m/z 259/274 ion ratio wherein ent-kaurane is characterized by higher relative intensity of m/z 259 as compared to m/z 274. In our study, the diterpane peak is identified as ent-kaurane based on the higher m/z 259/274 ion ratio (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. (A) Selected ion chromatogram at m/z 123 depicting the peak for the diterpane compound detected as ent-kaurane in the saturated hydrocarbon fraction extracted from the studied sediment (K56, ∼3733 cal yr BP). The structure of ent-kaurane is provided. (B) The mass spectrum of ent-kaurane with the base peak at m/z 123 and major mass fragments at m/z 259 and m/z 274 are given.

Hopanoids

Hopanoids are identified in selected ion chromatogram at m/z 191 in saturated hydrocarbon fractions of the studied sediments (Figure 6). The spectrum comprises both saturated and unsaturated compounds. 22, 29, 30-Trisnorhop-17(21)-ene (Te) is identified from the characteristic mass fragment at m/z 368 and other major diagnostic fragments at m/z 191 and m/z 231 (Nizar et al., 2021). The molecular ion fragment at m/z 368 (M+ -2H+) indicates unsaturation in the cyclic structure. C30 Diploptene [hop-22(29)-ene] is identified by the molecular ion at m/z 410 and characteristic mass fragments at m/z 191, 395, 299 (Sessions et al., 2013). 17α(H)-22, 29, 30-Trisnorhopane (Tm), a saturated C27 hopane, is identified based on the typical mass fragments in selected ion chromatogram at m/z 149 and major ions at m/z 191, 355 and 370 (Waples and Machihara, 1991). Other saturated hopanes include C29 norhopane and its isomer detected in selected ion chromatogram at m/z 177, C30 hopane and C31 hopane. Additionally, C31 methyl hopane, in selected ion chromatogram at m/z 205 is found to be present in the sediment samples. The mass fragment at m/z 177 signifies loss of a methyl group from the pentacyclic structure of hopane, whereas the presence of the fragment at m/z 205 indicates presence of a methyl group in the A-ring.

FIGURE 6. Selected ion chromatogram at m/z 191 depicting the peaks for the hopanoids in the saturated hydrocarbon fraction extracted from the studied sediment (K1, ∼369 cal yr BP). The hopanoid spectrum comprises both unsaturated (diploptene) and saturated compounds viz. Tm, C29 norhopane and its isomer, C30 hopane, C31 hopane and C31 methylhopane.

Discussion

Depositional Conditions and Preservation of Organic Matter

Depositional Condition of the Environment

A significantly well-preserved organic matter transforming into the peat layers is evident from the high CPI values indicating limited microbial breakdown and diagenetic alterations (Alexander et al., 1981; Marzi et al., 1993; Peters et al., 2005). Further, low degree of biodegradation and relatively mild diagenesis are confirmed by the relation between Pr/n-C17 and Ph/n-C18 (Peters et al., 1999) (Figure 7) and presence of the unsaturated hopanes such as 22, 29, 30-trisnorhop-17(21)-ene (Te), and hop-22(29)-ene (diploptene). With increasing microbial degradation, values for the ratios Pr/n-C17 and Ph/n-C18 increase (>1) since normal alkanes are consumed faster than acyclic terpenoids. The structural similarity between 22, 29, 30-trisnorhop-17(21)-ene (Te) and 17α(H)-22, 29, 30-trisnorhopane (Tm) suggests that Te is the biogenic precursor of Tm and that the latter is produced during early diagenetic conditions in the sediment matrix. Further, the unsaturated hopanes indicate that the depositional condition was favorable towards inhibiting complete oxidation and degradation of the hopanoid class of compounds. Moderate degeneration of the organic matter and little taphonomic changes of the molecular fossils are plausibly consequential to the suboxic depositional condition of the environment as evident from low Pr/Ph values (Table 1) and corroborated by the relation between Pr/n-C17 and Ph/n-C18 (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7. Cross plot between pristane/n-C17 and phytane/n-C18 describing the type of biota forming the peat and organic rich layers in the studied section. The cross plot also indicates the extent of biodegradation of the preserved organic matter in the sediments, level of thermal maturity and the redox condition [modified after Alexander et al. (1981)].

Organic Matter Sources

Further, to understand the OM sources, biomarker signatures have been utilized here. The reconstruction of organic matter input is important to understand the endemic vegetation forming peat layers in the region (discussed herein) as well as to detect any biotic changes induced due to climatic and/or environmental shifts (see Changes in Monsoonal Intensity as Inferred From Molecular Markers). The ratio between Pr/n-C17 and Ph/n-C18 indicates that most of the samples lie in the zone of mixed organic matter, whereas only a few of them are exclusively characterized in land plants-derived organic matter (terrestrial vascular plants) (Figure 7). The sediment samples in the “mixed OM” zone are those that comprise OM formed from both wetland biota and terrestrial vascular plant. These samples characteristically have moderate to high Paq and n-C23/n-C31 and low ACL (signifying higher water levels and stronger precipitation). Conversely, the samples in “terrestrial vascular plants” zone represent the ones that have low Paq and n-C23/n-C31 and high ACL (indicating lowering of water levels that reduced the aquatic vegetation cover possibly consequential to decreased precipitation). The high molecular weight alkanes and strong odd-over-even carbon predominance also primarily indicate the contribution of vascular plants in the formation of the peat deposits. Sphagnum moss, a bryophyte, generally thrives in submerged/floating conditions and is one of the quintessential peat-forming aquatic biota (Cranwell, 1973; Ficken et al., 1998; Nott et al., 2000; Bingham et al., 2010). The Sphagnum species are dominant producers of the mid-chain lengths, typically the n-C23 and n-C25 (Bingham et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2017). Therefore, the periodic enrichment of n-C23/n-C31 ratio in the studied succession indicates contribution of Sphagnum-rich vegetation into formation of the peat layers. Further, the higher order terrestrial plants are dominated by the long chain (n-C27–n-C33) homologues. Notably, the modern arboreal vegetation cover in the study area is dominated by a preponderance of conifer elements (Kar et al., 2016; Srivastava et al., 2017). In particular, the vascular plant input includes gymnosperms as reflected by the presence of specific ent-kaurane diterpane compound. The compound ent-kaurene, which is the precursor for ent-kaurane is produced abundantly in conifer resins. Additionally, microbial biota such as bacteria also contributed into the peat-forming OM as revealed by the presence of the hopanoids. These compounds are produced as an integral part of the cellular membrane by prokaryotes of diverse taxonomic clades (Ourisson and Albrecht, 1992). The presence of the mono-unsaturated hopanoid compounds viz. 22, 29, 30-trisnorhop-17(21)-ene (Te), and C30 diploptene, i.e., hop-22(29)-ene are tracers of bacterial input into the organic matter (Ochs et al., 1992). A possible cyanobacterial source for 17α(H)-22, 29, 30-trisnorhopane (Tm) is suggested by Freeman et al. (1994). The C31 methylhopane is also known to be produced by cyanobacteria (Brocks et al., 2003). Likewise, the short chain n-alkanes (n-C15–n-C21) in the present study could be attributed to microbial input such as prokaryotes or algae (Cranwell et al., 1987). Concentrations of the shorter chain alkanes viz. n-C17, n-C19 are relatively low as compared to the mid- and long-chain alkanes throughout our studied sedimentary record suggesting subdued presence of microbial biota. The acyclic terpenoids pristane and the phytane, produced from the phytyl side chain of chlorophyll upon diagenetic alterations in the sediments, could also be derivatives of microbial organisms or vascular higher plants.

Changes in Monsoonal Intensity as Inferred From Molecular Markers

Various n-alkane proxies derived from sedimentary records are robust indicators of source biota in peat along with the palaeohydrological conditions (Baker et al., 2016; Basu et al., 2017; He et al., 2019). For e.g., higher ACL values reflect the modification of wax lipid composition by plants as an adaptive measure to changing climatic conditions. The longer chain n-alkanes are hydrophobic in nature and hence increasingly produced in arid condition. Being hydrophobic, the longer chain n-alkanes create an impermeable layer that minimizes desiccation in drier environment. Hence, greater synthesis of the longer chain n-alkanes, reflected by higher ACL and lower n-C23/n-C31 values, is one of the survival strategies of vascular land plants to combat dry spells and protect the cellular apparatus (Sarkar et al., 2014; Andrae et al., 2019). Marked variations are observed for CPI values in the studied section and higher values (>2) are reflective of preservation of fresh organic matter in the region (Figure 4). Further, the relative contribution of Sphagnum spp. and other vascular land plants has been assessed by the n-C23/n-C31 and Paq ratios wherein higher values are corelatable with expansion of wetland biota The trend in the n-C23/n-C31 ratios complements the variability in ACL values as deduced from the studied sediments and a clear inverse correlation could be established between the ACL and n-C23/n-C31 ratios (Figure 4; Table 1). Likewise, higher values of Paq across the studied succession, related to increased aquatic taxa input, correlates well with higher range of n-C23/n-C31 (Figure 4; Table 1). In terms of the n-alkanes proxy variables, climate variability in Kedarnath region can be divided into four distinct intervals: 1) ∼7515 to ∼5300 cal yr BP depicting higher Paq and n-C23/n-C31 and lower ACL values 2) ∼5300 to ∼3600 cal yr BP characterized by oscillating ACL and Paq (also n-C23/n-C31) 3) ∼3600 to ∼2300 cal yr BP with reversal to higher Paq and n-C23/n-C31 4) ∼2300 to ∼370 cal yr BP characterized by lower n-C23/n-C31, Paq and increase in ACL index (Figure 4). During the time span between ∼7515 and ∼2300 cal yr BP, the higher n-C23/n-C31 values are accompanied by lower ACL (and higher Paq) and vice versa (Figure 4). This is reflective of a generally enhanced monsoonal phase and wetter hydrological condition that facilitates the proliferation of the hygrophilic Sphagnum moss biota. Despite generally intensified monsoon, there were brief periods of aridity during the time span between ∼5300 and ∼3600 cal yr BP. Further, a significant deviation towards lower ACL and higher n-C23/n-C31 is observed for a short interval between ∼3600 and ∼2300 cal yr BP (Figure 4). This reflects return of humid condition briefly consequential to strengthening of monsoon that again resulted into proliferation of aquatic vegetation in the area. The increased precipitation facilitated expansion of waterlogged condition that is highly desirable for expansion of Sphagnum flora (Inglis et al., 2015). Conversely, lower values for the n-C23/n-C31 are co-relatable with higher ACL values between the interval ∼2300 and ∼370 cal yr BP (Figure 4). This observation suggests arid conditions resulting into sparse cover of Sphagnum-dominated vegetation during the period.

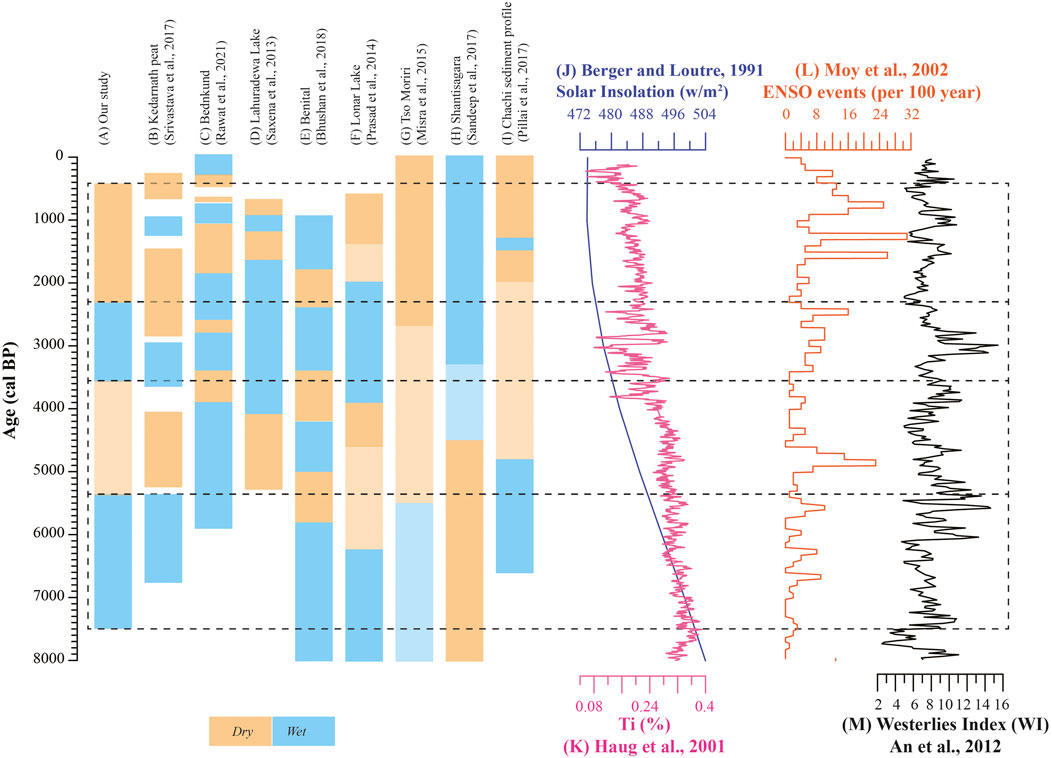

Palaeohydrological Changes in Kedarnath and a Regional Comparison

The present study based on n-alkane proxies from Kedarnath peat succession clearly demonstrates a shift in the biotic composition in response to a change in the hydrological conditions since mid-Holocene (ca. 7500 cal yr BP).

The wetter climatic condition during ∼7515 to ∼5300 cal yr BP inferred by n-alkane proxies is in agreement with previous geochemical and bulk organic proxy-based data from the region which shows warmer and wetter condition during mid-Holocene (∼6500 to ∼5400 cal yr BP) (Srivastava et al., 2017). Likewise, the pollen-based investigations from Bednikund and Tso Kar lakes (NW Himalaya) shows a short-term mid-Holocene climate optimum and intensified ISM (Demske et al., 2009; Rawat et al., 2021). In contrast, the terrestrial records from the Himalayan region (Tso Moriri and Benital lakes), southern India (Shantisagara Lake) and the central India (Lonar and Nonia Tal lakes) demonstrate early Holocene intensification followed by general weakening in monsoonal precipitation during the mid-Holocene (Prasad et al., 2014; Mishra et al., 2015; Sandeep et al., 2017; Bhushan et al., 2018; Kumar et al., 2019). Similarly, the Globigerina bulloides-based study from Arabian Sea (Gupta et al., 2003) and Globigerinoides ruber from Bay of Bengal (Rashid et al., 2011) have also portrayed an early Holocene intensification in response to the Northern Hemispheric solar insolation (Berger and Loutre, 1991) (Figure 8). Conversely, the pollen-based palaeorecord from Indo-Gangetic plain (Lahuradewa Lake) indicate a prolonged ISM intensification during ∼9200 to ∼5300 cal yr BP (Saxena et al., 2013). The δ18O record from Kotumsar cave in central India represent mid-Holocene wetter climatic condition punctuated by series of megadroughts probably linked to increased frequency of El Nino events and weaker North Atlantic circulations (Band et al., 2018).

Further, a major shift in climatic pattern in the Kedarnath region is observed between ∼5300 and 3600 cal yr BP. This brief period of generally weakened monsoon with high frequency climate variability is clearly visible in both our proxy records and the previous study by Srivastava et al. (2017). Such a scenario is well recorded in several other studies from the Indian sub-continent (e.g., Lahuradewa in central India, Benital and Tso Moriri in NW Himalaya, Lonar Lake in central India, and Chachi sediment profile in the western India) (Saxena et al., 2013; Prasad et al., 2014; Mishra et al., 2015; Pillai et al., 2017; Bhushan et al., 2018). Further, low ACL and high Paq and n-C23/n-C31 values between ∼3600 and ∼2300 cal yr BP reflect wetter climatic condition due to increased monsoonal precipitation in the studied region. The NW Himalayan region (Bednikund Lake during ∼3300 to ∼2800 cal yr BP and Benital Lake between ∼3500 and ∼2400 cal yr BP) have also recorded wetter climatic condition in response to Northern Hemisphere temperature variability and increased solar irradiance (Bhushan et al., 2018; Rawat et al., 2021). In contrast, the record from central and southern India shows drier (weak monsoon) climatic condition due to weakening of ISM precipitation (Prasad et al., 2014; Sandeep et al., 2017). This discrepancy might be attributed to increased contribution of Westerlies as the region receives precipitation from dual sources (both ISM and Westerlies). This is supported by increased westerly contribution during ∼3600 to ∼2300 cal yr BP (An et al., 2012) (Figure 8).

Lastly, the period between ∼2300 and ∼370 cal yr BP exhibit low n-C23/n-C31 and Paq and high ACL suggesting progressive weakening of monsoonal condition in the region. Other signatures such as subdued presence of broad-leaved taxa and marshy flora also confirms the prevalence of drier conditions (Bingham et al., 2010; Inglis et al., 2015). The previous study has revealed two short-term centennial scale climatic events such as Medieval Climate Anomaly (during ∼1250 to ∼800 cal yr BP) and Little Ice Age (∼600 and ∼250 cal yr BP) (Srivastava et al., 2017). However, in our present proxy study, the identification of these events is beyond the scope due to relatively low sample resolution as a result of unavailability of sediments in these intervals that are most appropriate for organic geochemical analyses. Moreover, with the exception of these short term events, the majority of palaeoclimate records demonstrate depreciating monsoonal condition over the Indian subcontinent. This progressive decrease in monsoonal precipitation is mostly interpreted in terms of southern migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) coupled with increased frequency of El Niño events (Haug et al., 2001; Moy et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2020). For example, the proxy records from Bednikund suggest intermittent weak monsoonal condition (1860–1050 cal yr BP followed by 760 to 580 cal yr BP and 500 to 320 cal yr BP) punctuated by several short term wet phase (Rawat et al., 2021). The study suggests the role of solar insolation and Northern Hemisphere temperature effects in controlling the climatic condition in the NW Himalaya. Likewise, the evaporative carbonates from Tso Moriri Lake indicate weakest monsoon (2700 cal yr BP to present) in response to reduced solar insolation (Mishra et al., 2015).

Thus succinctly, similar multiproxy studies from different climatic sensitive region are warranted to further understand the mechanisms for the spatial and temporal heterogeneity and the impact of teleconnections in monsoon variability (e.g., El Nino) (Figure 8).

Conclusion

A sedimentary succession with peat layers from the Kedarnath region, Garhwal Himalaya spanning the last 8000 cal yr BP has been investigated for lipid biomarkers. The peat-forming organic constituents include gymnosperms and Sphagnum moss as evident from the presence of ent-kaurane and high abundance of the n-C23 alkane, respectively. A variety of hopanoid compounds both unsaturated including hop-22(29)-ene and 22, 29, 30-trisnorhop-17(21)-ene (Te) and saturated such as the 17α(H)-22, 29, 30-trisnorhopane (Tm), C29 norhopanes, C30 hopane, C31 hopane and C31 methyl hopane reveal the suite of microbially derived lipid constituents. The n-alkane proxies used in the present study (Paq, ACL, n-C23/n-C31) and previously published records clearly reveal shift in the intensity of monsoon and a concomitant changeover in the vegetation cover. The relatively high abundance of mid-chain alkane homologues during the interval between ∼7515 and ∼2300 cal yr BP suggests significant aquatic vegetation cover. The palaeohydrologic condition is established as wetter during the aforementioned interval although interlude periods of aridity had prevailed as evident from frequent shifts towards the longer n-alkane chain lengths, typically during ∼5300 to ∼3600 cal yr BP. Beginning at around 2300 cal yr BP until around 370 cal yr BP, the climate entered a prolonged phase of aridity triggering the synthesis of longer chain n-alkanes as a protective measure by the terrestrial plants to combat the dry spells. The climate reconstruction as inferred from the n-alkane proxies is consistent with the previously determined multiproxy records and attests the applicability of hydrocarbon biomarkers for past climatic reconstructions in sedimentary successions. The overall comparison of palaeoclimate data from the Kedarnath peat succession with other regional records reveals temporal and spatial heterogeneity in monsoonal pattern over the Indian sub-continent during mid to late Holocene.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

SB, PM, and PS designed the research; PS collected the samples; HK and YA performed the analyses; SB and PM interpreted the data; SB and PM wrote the manuscript; YA and PS provided useful comments on the draft manuscript.

Funding

We thank Department of Science and Technology (DST) for the financial support (INSPIRE-18-149 and INSPIRE-15-2769).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Anoop Ambili for the access to speed extractor and GC-MS at his laboratory and useful discussion and all the members of PRISM lab for technical support. SB greatly appreciates Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, IISER Mohali for the necessary infrastructure and facilities provided for accomplishing the research.

References

Alexander, R., Kagi, R., and Woodhouse, G. W. (1981). Geochemical Correlation of Windalia Oil and Extracts of Winning Group (Cretaceous) Potential Source Rocks, Barrow Subbasin, Western Australia. AAPG Bull. 65, 235–250. doi:10.1306/2f9197b0-16ce-11d7-8645000102c1865d

An, Z., Colman, S. M., Zhou, W., Li, X., Brown, E. T., Jull, A. J. T., et al. (2012). Interplay between the Westerlies and Asian Monsoon Recorded in Lake Qinghai Sediments since 32 Ka. Sci. Rep. 2, 1–7. doi:10.1038/srep00619

Andrae, J. W., McInerney, F. A., Tibby, J., Henderson, A. C. G., Hall, P. A., Marshall, J. C., et al. (2019). Variation in Leaf Wax N-Alkane Characteristics with Climate in the Broad-Leaved Paperbark (Melaleuca Quinquenervia). Org. Geochem. 130, 33–42. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2019.02.004

Ankit, Y., Muneer, W., Lahajnar, N., Gaye, B., Misra, S., Jehangir, A., et al. (2021). Long Term Natural and Anthropogenic Forcing on Aquatic System - Evidence Based on Biogeochemical and Pollen Proxies from lake Sediments in Kashmir Himalaya, India. Appl. Geochem. 131, 105046. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2021.105046

Anoop, A., Prasad, S., Krishnan, R., Naumann, R., and Dulski, P. (2013). Intensified Monsoon and Spatiotemporal Changes in Precipitation Patterns in the NW Himalaya during the Early-Mid Holocene. Quat. Int. 313-314, 74–84. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.08.014

Baker, A., Routh, J., and Roychoudhury, A. N. (2018). n-Alkan-2-one Biomarkers as a Proxy for Palaeoclimate Reconstruction in the Mfabeni Fen, South Africa. Org. Geochem. 120, 75–85. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.03.001

Baker, A., Routh, J., and Roychoudhury, A. N. (2016). Biomarker Records of Palaeoenvironmental Variations in Subtropical Southern Africa since the Late Pleistocene: Evidences from a Coastal Peatland. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 451, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.03.011

Band, S., Yadava, M. G., Lone, M. A., Shen, C.-C., Sree, K., and Ramesh, R. (2018). High-resolution Mid-holocene Indian Summer Monsoon Recorded in a Stalagmite from the Kotumsar Cave, Central India. Quat. Int. 479, 19–24. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2018.01.026

Basu, S., Anoop, A., Sanyal, P., and Singh, P. (2017). Lipid Distribution in the lake Ennamangalam, South India: Indicators of Organic Matter Sources and Paleoclimatic History. Quat. Int. 443, 238–247. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.08.045

Bechtel, A., Sachsenhofer, R. F., Markic, M., Gratzer, R., Lücke, A., and Püttmann, W. (2003). Paleoenvironmental Implications from Biomarker and Stable Isotope Investigations on the Pliocene Velenje lignite Seam (Slovenia). Org. Geochem. 34, 1277–1298. doi:10.1016/s0146-6380(03)00114-1

Benn, D. I., and Owen, L. A. (1998). The Role of the Indian Summer Monsoon and the Mid-latitude Westerlies in Himalayan Glaciation: Review and Speculative Discussion. J. Geol. Soc. 155, 353–363. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.155.2.0353

Berger, A., and Loutre, M. F. (1991). Insolation Values for the Climate of the Last 10 Million Years. Quat. Sci. Rev. 10, 297–317. doi:10.1016/0277-3791(91)90033-Q

Bhushan, R., Sati, S. P., Rana, N., Shukla, A. D., Mazumdar, A. S., and Juyal, N. (2018). High-resolution Millennial and Centennial Scale Holocene Monsoon Variability in the Higher Central Himalayas. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 489, 95–104. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.09.032

Bingham, E. M., McClymont, E. L., Väliranta, M., Mauquoy, D., Roberts, Z., Chambers, F. M., et al. (2010). Conservative Composition of N-Alkane Biomarkers in Sphagnum Species: Implications for Palaeoclimate Reconstruction in Ombrotrophic Peat Bogs. Org. Geochem. 41, 214–220. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2009.06.010

Brocks, J. J., Buick, R., Logan, G. A., and Summons, R. E. (2003). Composition and Syngeneity of Molecular Fossils from the 2.78 to 2.45 Billion-Year-Old Mount Bruce Supergroup, Pilbara Craton, Western Australia. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 67, 4289–4319. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(03)00208-4

Bulbul, M., Ankit, Y., Basu, S., and Anoop, A. (2021). Characterization of Sedimentary Organic Matter and Depositional Processes in Mandovi Estuary, Western India: An Integrated Lipid Biomarker, Sedimentological and Stable Isotope Approach. Appl. Geochem. 131, 105041. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2021.105041

Bush, R. T., and McInerney, F. A. (2013). Leaf Wax N-Alkane Distributions in and across Modern Plants: Implications for Paleoecology and Chemotaxonomy. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 117, 161–179. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2013.04.016

Chambers, F. M., Booth, R. K., De Vleeschouwer, F., Lamentowicz, M., Le Roux, G., Mauquoy, D., et al. (2012). Development and Refinement of Proxy-Climate Indicators from Peats. Quat. Int. 268, 21–33. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.04.039

Chen, J., and Summons, R. E. (2001). Complex Patterns of Steroidal Biomarkers in Tertiary Lacustrine Sediments of the Biyang Basin, China. Org. Geochem. 32, 115–126. doi:10.1016/s0146-6380(00)00145-5

Cranwell, P. A. (1973). Chain-length Distribution of N-Alkanes from lake Sediments in Relation to post-glacial Environmental Change. Freshw. Biol 3, 259–265. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.1973.tb00921.x

Cranwell, P. A., Eglinton, G., and Robinson, N. (1987). Lipids of Aquatic Organisms as Potential Contributors to Lacustrine Sediments-II. Org. Geochem. 11, 513–527. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(87)90007-6

Dai, S., Bechtel, A., Eble, C. F., Flores, R. M., French, D., Graham, I. T., et al. (2020). Recognition of Peat Depositional Environments in Coal: A Review. Int. J. Coal Geology. 219, 103383. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2019.103383

Demske, D., Tarasov, P. E., Wünnemann, B., and Riedel, F. (2009). Late Glacial and Holocene Vegetation, Indian Monsoon and westerly Circulation in the Trans-himalaya Recorded in the Lacustrine Pollen Sequence from Tso Kar, Ladakh, NW India. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 279, 172–185. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.05.008

Didyk, B. M., Simoneit, B. R. T., Brassell, S. C., and Eglinton, G. (1978). Organic Geochemical Indicators of Palaeoenvironmental Conditions of Sedimentation. Nature 272, 216–222. doi:10.1038/272216a0

Dutta, S., Bhattacharya, S., and Raju, S. V. (2013). Biomarker Signatures from Neoproterozoic-Early Cambrian Oil, Western India. Org. Geochem. 56, 68–80. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2012.12.007

Eglinton, G., and Hamilton, R. J. (1967). Leaf Epicuticular Waxes. Science 156, 1322–1335. doi:10.1126/science.156.3780.1322

Eglinton, T. I., and Eglinton, G. (2008). Molecular Proxies for Paleoclimatology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 275, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.07.012

Ficken, K. J., Barber, K. E., and Eglinton, G. (1998). Lipid Biomarker, δ13C and Plant Macrofossil Stratigraphy of a Scottish Montane Peat Bog over the Last Two Millennia. Org. Geochem. 28, 217–237. doi:10.1016/S0146-6380(97)00126-5

Ficken, K. J., Li, B., Swain, D. L., and Eglinton, G. (2000). An N-Alkane Proxy for the Sedimentary Input of Submerged/floating Freshwater Aquatic Macrophytes. Org. Geochem. 31, 745–749. doi:10.1016/S0146-6380(00)00081-4

Finlayson, C. M., and Milton, G. R. (2016). “Peatlands,” in The Wetland Book. Editors C. Finlayson, G. Milton, R. Prentice, and N Davidson (Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media), 227–244. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6173-5_202-1

Freeman, K. H., Wakeham, S. G., and Hayes, J. M. (1994). Predictive Isotopic Biogeochemistry: Hydrocarbons from Anoxic marine Basins. Org. Geochem. 21, 629–644. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(94)90009-4

French, K. L., Birdwell, J. E., and Vanden Berg, M. D. (2020). Biomarker Similarities between the saline Lacustrine Eocene Green River and the Paleoproterozoic Barney Creek Formations. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 274, 228–245. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2020.01.053

Gorham, E., Janssens, J. A., and Glaser, P. H. (2003). Rates of Peat Accumulation during the Postglacial Period in 32 Sites from Alaska to Newfoundland, with Special Emphasis on Northern Minnesota. Can. J. Bot. 81, 429–438. doi:10.1139/b03-036

Gupta, A. K., Anderson, D. M., and Overpeck, J. T. (2003). Abrupt Changes in the Asian Southwest Monsoon during the Holocene and Their Links to the North Atlantic Ocean. Nature 421, 354–357. doi:10.1038/nature01340

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P., and Lister, D. (2020). Version 4 of the CRU TS Monthly High-Resolution Gridded Multivariate Climate Dataset. Sci. Data 7, 1–18. doi:10.1038/s41597-020-0453-3

Haug, G. H., Hughen, K. A., Sigman, D. M., Peterson, L. C., and Röhl, U. (2001). Southward Migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone through the Holocene. Science 293, 1304–1308. doi:10.1126/science.1059725

He, D., Huang, H., and Arismendi, G. G. (2019). n-Alkane Distribution in Ombrotrophic Peatlands from the Northeastern Alberta, Canada, and its Paleoclimatic Implications. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 528, 247–257. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.05.018

Inglis, G. N., Collinson, M. E., Riegel, W., Wilde, V., Robson, B. E., Lenz, O. K., et al. (2015). Ecological and Biogeochemical Change in an Early Paleogene Peat-Forming Environment: Linking Biomarkers and Palynology. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 438, 245–255. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.08.001

Jiang, L., Ding, W., and George, S. C. (2020). Late Cretaceous-Paleogene Palaeoclimate Reconstruction of the Gippsland Basin, SE Australia. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 556, 109885. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109885

Jordan, S. F., Murphy, B. T., O'Reilly, S. S., Doyle, K. P., Williams, M. D., Grey, A., et al. (2017). Mid-Holocene Climate Change and Landscape Formation in Ireland: Evidence from a Geochemical Investigation of a Coastal Peat Bog. Org. Geochem. 109, 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.02.004

Kar, R., Bajpai, R., and Mishra, K. (2016). Modern Pollen Rain in Kedarnath: Implications for Past Vegetation and Climate. Curr. Sci. 110, 296–298. doi:10.18520/cs/Fv110/Fi/2F296-298

Kayranli, B., Scholz, M., Mustafa, A., and Hedmark, Å. (2010). Carbon Storage and Fluxes within Freshwater Wetlands: A Critical Review. Wetlands 30, 111–124. doi:10.1007/s13157-009-0003-4

Kelly, A. E., Love, G. D., Zumberge, J. E., and Summons, R. E. (2011). Hydrocarbon Biomarkers of Neoproterozoic to Lower Cambrian Oils from Eastern Siberia. Org. Geochem. 42, 640–654. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2011.03.028

Kumar, K., Agrawal, S., Sharma, A., and Pandey, S. (2019). Indian Summer Monsoon Variability and Vegetation Changes in the Core Monsoon Zone, India, during the Holocene: A Multiproxy Study. The Holocene 29, 110–119. doi:10.1177/0959683618804641

Kumar, O., Ramanathan, A., Bakke, J., Kotlia, B. S., Shrivastava, J. P., Kumar, P., et al. (2021). Role of Indian Summer Monsoon and Westerlies on Glacier Variability in the Himalaya and East Africa during Late Quaternary: Review and New Data. Earth-Science Rev. 212, 103431. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103431

Kumaran, N. K. P., Padmalal, D., Limaye, R. B., S., V. M., Jennerjahn, T., and Gamre, P. G. (2016). Tropical Peat and Peatland Development in the Floodplains of the Greater Pamba Basin, South-Western India during the Holocene. PLoS One 11, e0154297–21. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154297

Marcisz, K., Colombaroli, D., Jassey, V. E. J., Tinner, W., Kołaczek, P., Gałka, M., et al. (2016). A Novel Testate Amoebae Trait-Based Approach to Infer Environmental Disturbance in Sphagnum Peatlands. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–11. doi:10.1038/srep33907

Marzi, R., Torkelson, B. E., and Olson, R. K. (1993). A Revised Carbon Preference index. Org. Geochem. 20, 1303–1306. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(93)90016-5

Middleton, G. V. (1973). Johannes Walther's Law of the Correlation of Facies. Geol. Soc. America Bull. 84, 979–988. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1973)84<979:JWLOTC>2.0.CO;2

Mishra, P. K., Anoop, A., Schettler, G., Prasad, S., Jehangir, A., Menzel, P., et al. (2015). Reconstructed Late Quaternary Hydrological Changes from Lake Tso Moriri, NW Himalaya. Quat. Int. 371, 76–86. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.11.040

Misra, S., Bhattacharya, S., Mishra, P. K., Misra, K. G., Agrawal, S., and Anoop, A. (2020). Vegetational Responses to Monsoon Variability during Late Holocene: Inferences Based on Carbon Isotope and Pollen Record from the Sedimentary Sequence in Dzukou valley, NE India. Catena 194, 104697. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2020.104697

Moy, C. M., Seltzer, G. O., Rodbell, D. T., and Anderson, D. M. (2002). Variability of El Niño/Southern Oscillation Activity at Millennial Timescales during the Holocene Epoch. Nature 420, 162–165. doi:10.1038/nature01194

Naafs, B. D. A., Inglis, G. N., Blewett, J., McClymont, E. L., Lauretano, V., Xie, S., et al. (2019). The Potential of Biomarker Proxies to Trace Climate, Vegetation, and Biogeochemical Processes in Peat: A Review. Glob. Planet. Change 179, 57–79. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2019.05.006

Nizar, O., Jean-Pierre, G., and Habib, B. (2021). Significance of 2-methylhopane and 22,29,30Trisnorhop17(21)-Ene Biomarkers in Holocene Sediments from the Gulf of Tunis - Southern Mediterranean Sea. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 173, 104043. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2020.104043

Noble, R. A., Alexander, R., Kagi, R. I., and Knox, J. (1985). Tetracyclic Diterpenoid Hydrocarbons in Some Australian Coals, Sediments and Crude Oils. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 49, 2141–2147. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(85)90072-9

Nott, C. J., Xie, S., Avsejs, L. A., Maddy, D., Chambers, F. M., and Evershed, R. P. (2000). n-Alkane Distributions in Ombrotrophic Mires as Indicators of Vegetation Change Related to Climatic Variation. Org. Geochem. 31, 231–235. doi:10.1016/S0146-6380(99)00153-9

Ochs, D., Kaletta, C., Entian, K. D., Beck-Sickinger, A., and Poralla, K. (1992). Cloning, Expression, and Sequencing of Squalene-Hopene Cyclase, a Key Enzyme in Triterpenoid Metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 174, 298–302. doi:10.1128/jb.174.1.298-302.1992

Ourisson, G., and Albrecht, P. (1992). Hopanoids. 1. Geohopanoids: the Most Abundant Natural Products on Earth? Acc. Chem. Res. 25, 398–402. doi:10.1021/ar00021a003

Pancost, R. D., Baas, M., van Geel, B., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. (2002). Biomarkers as Proxies for Plant Inputs to Peats: an Example from a Sub-boreal Ombrotrophic Bog. Org. Geochem. 33, 675–690. doi:10.1016/S0146-6380(02)00048-7

Peters, K. E., Fraser, T. H., Amris, W., Rustanto, B., and Hermanto, E. (1999). Geochemistry of Crude Oils from Eastern Indonesia. AAPG Bull. 83, 1927–1942. doi:10.1306/e4fd4643-1732-11d7-8645000102c1865d

Peters, K. E., Walters, C. C., and Moldowan, J. M. (2005). “The Biomarker Guide,” in Volume 2: Biomarkers and Isotopes in the Petroleum Exploration and Earth History. Second Edition (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press).

Phadtare, N. R. (2000). Sharp Decrease in Summer Monsoon Strength 4000-3500 Cal Yr B.P. In the Central Higher Himalaya of India Based on Pollen Evidence from Alpine Peat. Quat. Res. 53, 122–129. doi:10.1006/qres.1999.2108

Pillai, A. A. S., Anoop, A., Sankaran, M., Sanyal, P., Jha, D. K., and Ratnam, J. (2017). Mid-late Holocene Vegetation Response to Climatic Drivers and Biotic Disturbances in the Banni Grasslands of Western India. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 485, 869–878. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.07.036

Prasad, S., Anoop, A., Riedel, N., Sarkar, S., Menzel, P., Basavaiah, N., et al. (2014). Prolonged Monsoon Droughts and Links to Indo-Pacific Warm Pool: A Holocene Record from Lonar Lake, central India. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 391, 171–182. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.01.043

Rashid, H., England, E., Thompson, L., and Polyak, L. (2011). Late Glacial to Holocene Indian Summer Monsoon Variability Based upon Sediment Records Taken from the Bay of Bengal. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 22, 215–228. doi:10.3319/TAO.2010.09.17.02(TibXS)

Rawat, S., Gupta, A. K., Sangode, S. J., Srivastava, P., and Nainwal, H. C. (2015). Late Pleistocene-Holocene Vegetation and Indian Summer Monsoon Record from the Lahaul, Northwest Himalaya, India. Quat. Sci. Rev. 114, 167–181. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.01.032

Rawat, V., Rawat, S., Srivastava, P., Negi, P. S., Prakasam, M., and Kotlia, B. S. (2021). Middle Holocene Indian Summer Monsoon Variability and its Impact on Cultural Changes in the Indian Subcontinent. Quat. Sci. Rev. 255, 106825. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.106825

Sandeep, K., Shankar, R., Warrier, A. K., Yadava, M. G., Ramesh, R., Jani, R. A., et al. (2017). A Multi-Proxy lake Sediment Record of Indian Summer Monsoon Variability during the Holocene in Southern India. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 476, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.03.021

Sarkar, S., Wilkes, H., Prasad, S., Brauer, A., Riedel, N., Stebich, M., et al. (2014). Spatial Heterogeneity in Lipid Biomarker Distributions in the Catchment and Sediments of a Crater lake in central India. Org. Geochem. 66, 125–136. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2013.11.009

Saxena, A., Prasad, V., and Singh, I. B. (2013). Holocene Palaeoclimate Reconstruction from the Phytoliths of the lake-fill Sequence of Ganga plain. Curr. Sci. 104, 1054–1062.

Schellekens, J., Bradley, J. A., Kuyper, T. W., Fraga, I., Pontevedra-Pombal, X., Vidal-Torrado, P., et al. (2015). The Use of Plant-specific Pyrolysis Products as Biomarkers in Peat Deposits. Quat. Sci. Rev. 123, 254–264. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.06.028

Sessions, A. L., Zhang, L., Welander, P. V., Doughty, D., Summons, R. E., and Newman, D. K. (2013). Identification and Quantification of Polyfunctionalized Hopanoids by High Temperature Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Org. Geochem. 56, 120–130. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2012.12.009

Singh, S., Gupta, A. K., Dutt, S., Bhaumik, A. K., and Anderson, D. M. (2020). Abrupt Shifts in the Indian Summer Monsoon during the Last Three Millennia. Quat. Int. 558, 59–65. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.08.033

Srivastava, P., Agnihotri, R., Sharma, D., Meena, N., Sundriyal, Y. P., Saxena, A., et al. (2017). 8000-year Monsoonal Record from Himalaya Revealing Reinforcement of Tropical and Global Climate Systems since Mid-holocene. Sci. Rep. 7, 14515. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-15143-9

Tipple, B. J., and Pagani, M. (2013). Environmental Control on Eastern Broadleaf forest Species' Leaf Wax Distributions and D/H Ratios. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 111, 64–77. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2012.10.042

Tulipani, S., Grice, K., Greenwood, P. F., Haines, P. W., Sauer, P. E., Schimmelmann, A., et al. (2015). Changes of Palaeoenvironmental Conditions Recorded in Late Devonian Reef Systems from the Canning Basin, Western Australia: a Biomarker and Stable Isotope Approach. Gondwana Res. 28, 1500–1515. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2014.10.003

Valdiya, K. S., Paul, S. K., Chandra, T., Bhakuni, S. S., and Upadhyaya, R. C. (1999). Tectonic and Lithological Characterization of Himardri (Great Himalayan) between Kali and Yamuna Rivers, central Himalaya. Himal Geol. 20, 1–17.

Wang, M., Zhang, W., and Hou, J. (2015). Is Average Chain Length of Plant Lipids a Potential Proxy for Vegetation, Environment and Climate Changes? Biogeosciences Discuss. 12, 5477–5501. doi:10.5194/bgd-12-5477-2015

Waples, D. W., and Machihara, T. (1991). Biomarkers for Geologists. Tulsa, OK: American Association of Petroleum Geologists.

Zhang, Y., Meyers, P. A., Gao, C., Liu, X., Wang, J., and Wang, G. (2017). Holocene Climate Change in Northeastern China Reconstructed from Lipid Biomarkers in a Peat Sequence from the Sanjiang Plain. Org. Geochem. 113, 105–114. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.07.018

Keywords: lipid biomarkers, peat, vegetation shift, Kedarnath, Garhwal Himalaya, palaeohydrological conditions

Citation: Bhattacharya S, Kishor H, Ankit Y, Mishra PK and Srivastava P (2021) Vegetation History in a Peat Succession Over the Past 8,000 years in the ISM-Controlled Kedarnath Region, Garhwal Himalaya: Reconstruction Using Molecular Fossils. Front. Earth Sci. 9:703362. doi: 10.3389/feart.2021.703362

Received: 30 April 2021; Accepted: 19 August 2021;

Published: 06 September 2021.

Edited by:

Steven L. Forman, Baylor University, United StatesReviewed by:

Nadia Solovieva, University College London, United KingdomFrancien Peterse, Utrecht University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2021 Bhattacharya, Kishor, Ankit, Mishra and Srivastava. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sharmila Bhattacharya, c2JoYXR0YWNoYXJ5YUBpaXNlcm1vaGFsaS5hYy5pbg==

Sharmila Bhattacharya

Sharmila Bhattacharya Harsh Kishor

Harsh Kishor Yadav Ankit

Yadav Ankit Praveen K. Mishra2

Praveen K. Mishra2