94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Earth Sci., 18 November 2020

Sec. Solid Earth Geophysics

Volume 8 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.590295

This article is part of the Research Topic3D Printing in Geology and Geophysics: A New World of Opportunities in Research, Outreach, and EducationView all 7 articles

Three-dimensional (3D) visualization has opened up a Universe of possible scientific data representations. 3D printing has the potential to make seemingly abstract and esoteric data sets accessible, particularly through the lens of translating data into forms that can be explored in the tactile modality for people who are blind or visually impaired. This article will briefly review 3D modeling in astrophysics, astronomy, and planetary science, before discussing 3D printed astrophysical and planetary geophysical data sets and their current and potential applications with non-expert audiences. The article will also explore the prospective pipeline and benefits of other 3D data outputs in accessible scientific research and communications, including extended reality and data sonification.

This paper will summarize recent achievements made in astronomy, astrophysics, and space science using three-dimensional (3D) technology to help reach beyond expert audiences, and discuss best practices that can be shared with other sciences such as geophysics. This type of 3D work also allows for new media—both virtual and in tangible physical form—to help non-experts interact with and learn about these discoveries. We contend that the lessons learned from these space-based 3D projects could have broader impacts for many fields throughout science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields and provide educational benefits to a great number of people.

Parallel advances in acquiring 3D data from Earth and space and in 3D printing mean that today technologists can translate digital data into something that we can touch and feel, expanding the ways we can understand and communicate science, including with diverse communities including the blind or visually impaired (BVI) (Trotta et al., 2020). Currently, the amount of astronomical and planetary geological objects able to be 3D printed is low compared to the vast range of objects being studied (Arcand et al., 2017). One practical challenge is making 3D modeling easier and more accessible as a research tool. This issue can be improved with the advent of enhanced data from the next generation of more technically advanced telescopes and sensors (Gerloni et al., 2018). Creating awareness among scientific researchers of 3D data representation is also essential to increasing this technique’s frequency and convenience of use.

This article describes recent innovative 3D processes and explores the developing pipelines and contributions of 3D visualization outputs in multimodal scientific study and communications. 3D printing, for example, is a potential place of interaction between terrestrial and space science through representations of discipline-specific and interdisciplinary data alike, aimed at both non-experts and experts that can use specific accessible outputs and products. Indeed, best practices for 3D printing of scientific data can and should be shared across traditionally separate disciplines.

Astronomical and other scientific information can be shared through various human senses including touch, smell, and even taste (Trotta, 2018). The use of, and meaning-making from, scientific visualizations and related expressions of data “depend strongly on who is viewing” (Steffen, 2016, para. 4) or interpreting them. Consequently, accessibility and diversity are a critical area of emphasis for this topic, and we will summarize current evidence of and future needs for the impact of 3D visualization on enhancing equity via modeling and printing. Our analysis briefly encompasses extended reality (XR)—a suite of multisensory applications which typically involves augmented, virtual, and mixed reality formats (Najjar, 2020) for diverse communities of users.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the potential for 3D modeling and printing—from making personal protective equipment to respirators1 and ventilators (e.g., Molitch-Hou, 2020) to understanding the structure and impact of the coronavirus through 3D printing (Grove, 2020) and virtual reality (VR) (e.g., Pearson, 2020). Although geophysics and astrophysics data typically cover very different phenomena, they can benefit from multidimensional data delivery to diverse audiences during times of disruption and beyond.

Learning about the mental manipulation of 3D images is an important step in the process of science education in both astronomy (Eriksson et al., 2014) and geology (Carneiro et al., 2018). 3D modeling skills can form the basis of a framework for teaching astronomy and related topics in a manner that enables non-experts to use and understand the same visual and conceptual assets as professional astronomers (Eriksson, 2019). Multidimensional models are also useful as teaching tools in geophysics to share the textures and geological arrangement of surfaces including sedimentary basins with students and the public (Carneiro et al., 2018). Simultaneously, the ability to research celestial or geophysical objects from multiple angles and viewpoints can help improve understanding of how scientific objects are structured or how the underlying physics works (Ferrand and Warren, 2018), making them a valuable tool. Once a 3D visualization has been created, there are multiple output potentials from interactive 3D digital models or physical 3D prints to immersive XR experiences (Arcand et al., 2018). 3D printing and other outputs involving touch can help encourage more “control” (Isenberg, 2013) and interactivity on behalf of users (Madura, 2017) than computerized 3D visualization usually allows.

3D printing is a process where a type of material such as plastic, metal, or an organic substance is continually added layer by layer to formulate the object (Grice et al., 2015). Recently, “on-demand processes” of 3D printing—typically characterized as fused deposition modeling—have become increasingly accessible and affordable for consumers (Takagishi and Umezu, 2017), including those in libraries and related educational and community settings. This opens the opportunity to produce scientific or educational tools in these learning environments that may have been unachievable before (Hasiuk et al., 2017). On consumer scales, 3D printing is still rather new, but the production possibilities are far-reaching. 3D printing applications in science range from plans for an on-demand and sustainable lunar base 3D printed from Moon dust (De Kestelier et al., 2015) to medical 3D printing of skin cells to help treat burn victims (Everett-Green, 2013; Brown, 2017).

The prominence of VR as an entertainment product in recent years has made such technologies more widely available for scientific communications and research in astronomy as well (Baracaglia and Vogt, 2020). Due to the extensive time and technical effort often needed to develop VR applications for astronomical or geological objects, modifiable generic VR templates could be helpful for the scientific community, and could help spark greater adoption for observational exploration (Baracaglia and Vogt, 2020). VR is another 3D tool that can potentially be used by scientists for visualizing the immense amount of “big data” making up modern astronomy, in particular for data mining, detection, removal, and quick-look rendering (Comparato et al., 2007; Donalek et al., 2014). Interactive VR is also able to take advantage of human depth perception as an ergonomic factor that enables quick identification and characterization of complex structures (Steffen, 2016). Augmented reality (AR), which overlays digital elements onto a user’s perception of the surrounding world, and VR can be important support tools in the processing of massive and complex scientific data sets. However, for any XR product, individual differences in the way people experience multimodal information should be taken into account (Olshannikova et al., 2015).

Astronomy and astrophysics (Rector et al., 2015) and geology and geophysics (Pound, 2019) are often recognized as highly visual fields both historically and today. This can create challenges in sharing data from these disciplines with BVI audiences. Evaluative studies have shown benefits in using 3D astrophysical models (Christian et al., 2015; Grice et al., 2015; Bonne et al., 2018; Arcand et al., 2019; Argudo-Fernández et al., 2020) for generating or positively impacting learning gains, inclusive practices, STEM identity, and mental visualization. Applications of 3D models in geology and geophysics have been demonstrated for use in museums and similar informal learning environments (Neitzke Adamo et al., 2019) and by other educators (Hasiuk et al., 2017).

In the past several years, research has shown that 3D printed scientific data from astrophysics and geophysics with tactile features can help communicate with BVI participants across a spectrum of abilities (Bonne et al., 2018) as well as with sighted people (European Southern Observatory, 2019), and also to promote inclusivity more broadly (Christian et al., 2015; Arcand et al., 2019). XR technologies particularly have been broadly shown to provide low-risk, high-impact virtual spaces that can accommodate physical barriers to interaction by providing learner-specific experiences (Chandrashekar, 2018), when crafted particularly through universal design techniques (McMahon and Walker, 2019; Menke et al., 2020).

Human and interpersonal issues must be considered in order to enable meaningful use of 3D prints and dynamic virtual spaces for science communication with BVI and other audiences. Audience awareness and the resulting specific development of visualizations with audience needs in mind is critical for the development of inclusive practices in 3D visualizations, facilitated by 3D printing and other emerging technologies (Díaz-Merced et al., 2011; Steffen et al., 2011; Díaz-Merced, 2013; Díaz-Merced, 2014; Steffen et al., 2014; Christian et al., 2015; Grice et al., 2015; Madura et al., 2015; Madura, 2017; Hurt et al., 2019).

Across the United States (Smithsonian Institution, 2014; ADA National Network, 2019) and around the globe (United Nations Disability, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2006), there are firm legal requirements to provide and maintain access to information, communication, and participatory opportunities for people with disabilities. Differently-abled populations need to be able to discover and share information in a way directly equivalent to how others complete such tasks (United Nations Disability, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2006). People with visual impairments, for example, exist with a specific spectrum of needs that can be affected by variables such as the timing and cause of their blindness’ onset (National Federation of the Blind and Finkelstein, 1994) or the amount of Braille literacy instruction (National Federation of the Blind Jernigan Institute, 2009).

Therefore, any effort should take into account how to effectively disseminate 3D prints and related Braille or tactile materials. Incurred costs can be problematic for organizations and individuals (Weferling, 2007; Beck-Winchatz and Riccobono, 2008; Arcand et al., 2019) as well as intended audiences, including BVI communities. These issues are particularly relevant during times of disruption and upheaval, as illustrated during the COVID-19 pandemic (McEvoy, 2020).

Planetary geology and geophysics are particularly well suited areas of study for the development of 3D visualization outputs including 3D models, 3D prints, and XR. 3D visualizations of the Earth can clarify geological phenomena to the public (Kyriakopoulos, 2019), while also supplementing instruction (Koelemeijer et al., 2019) and making it more accessible (Dolphin et al., 2019) In exoplanet research, studies on the habitability of exoplanet bodies like the TRAPPIST-1 system2 (NASA, 2019; Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 2020), and synthetic exoplanet systems (Alesina et al., 2018) have led to head-set based VR experiences for expert and non-expert audiences. 3D models have been useful in the study of asteroids (Kim, 2018) and aspects of other planetary bodies such as the atmospheres of Venus (Korycansky et al., 2002) and Titan (Charnay et al., 2014) as well as landscape evolution (Cornet et al., 2017). A wealth of data on our nearest neighbors, our Moon and Mars, has resulted in extensive 3D mapping of the various local topographies and geological structures (Edwards et al., 2005; Löwe and Klump, 2013; Ellison, 2014; Mars Exploration Rovers, 2014; Gwinner et al., 2015), and morphometric globes (Florinsky and Filippov, 2017) of these objects with outputs of 3D visualizations, primarily for scientific analysis.

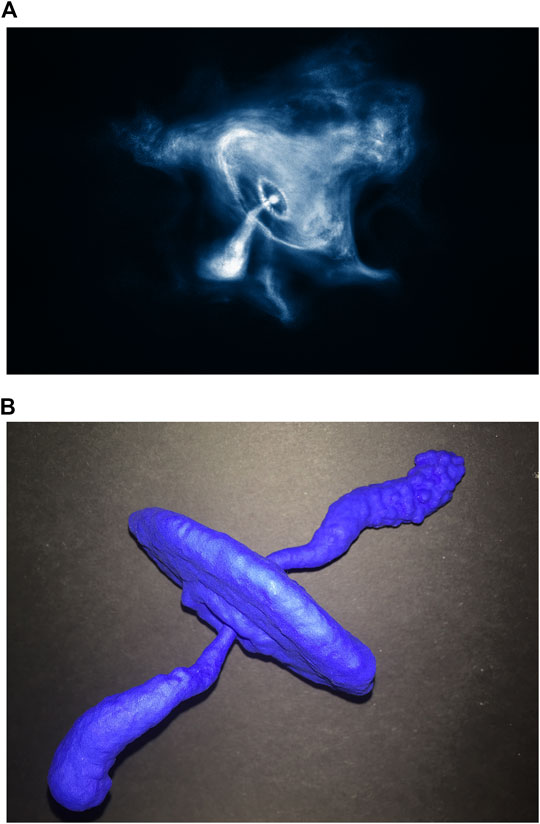

In astronomy and astrophysics, data and simulation driven 3D printed objects include multiple object types across a range of scales. In high-energy astrophysics, supernova remnants have been particularly conducive to 3D modeling, encompassing such examples as Cassiopeia A (Arcand et al., 2017; Arcand et al., 2018; Arcand et al., 2019; DeLaney et al., 2010; Orlando et al., 2016), Tycho’s supernova remnant (Chandra X-ray Observatory, 2019; Ferrand et al., 2019), Supernova 1987a (Arcand et al., 2017; Orlando et al., 2018; Arcand et al., 2019), and the Crab Nebula (Figures 1A,B) (Arcand et al., 2020; Summers et al., 2020). Beyond supernovae, other areas of 3D research and output range from star formation regions such as M16 (McLeod et al., 2015), a massive star system with colliding winds called Eta Carinae (Steffen et al., 2014; Madura et al., 2015; Arcand et al., 2017; Madura, 2017), double star system V745 Sco (Chandra X-ray Observatory, 2017; Arcand et al., 2019), protostellar jets like DG Tau (Ustamujic et al., 2016; Ustamujic et al., 2018; Orlando et al., 2019; Chandra X-ray Observatory, 2020a), and beyond to much larger structures including the South Pole Wall (Pomarède et al., 2020), the Cosmic Web (Diemer and Facio, 2017) and the Cosmic Microwave Background (Clements et al., 2016; Arcand et al., 2017).

FIGURE 1. The Crab Nebula is the remnant of a massive stellar explosion, or supernova, that was seen on Earth in 1054 AD. The nebula is about six light years across, or 60 trillion kilometers, and expanding outward at about 3 million miles/h. At the center of the bright nebula (A) is a rapidly spinning neutron star, or pulsar, that emits pulses of radiation 30 times a second. In this 3D print (B) of the inner region of the nebula is a ringed disk which is made up of energized material. Additionally, there is a pair of jets of particles firing off from opposite ends of the pulsar (the pulsar is hidden inside the ringed disk). Credits: 2D Image: NASA/CXC/SAO; 3D file: NASA/STScI/F. Summers et al.; NASA/Caltech/IPAC/R. Hurt; NASA/CXC/SAO/N. Wolk et al.; 3D Print: NASA/CXC/SAO/A. Jubett, K. Arcand et al.

Multidimensional renderings of astronomical and geological data in accessible formats can simplify the discovery of previously hidden or overlooked structures in objects and, through the presence of interactive features, can enable close-up views of data via a personalized perspective (Madura, 2017). This variety of technologies that have proven useful for accessible public engagement has helped to clarify the context of current observational science data (Madura et al., 2015; Arcand et al., 2017). The catalog of data-driven astrophysical or geological models continues to grow (Hurt et al., 2019), and can be used in communicating contemporary science with non-expert audiences (Löwe and Klump, 2013). Additionally, artistic imaginings with scientific underpinnings (Pauwels, 2020), in contrast to data-driven or simulation based 3D models, can tangibly provide perceptual value in communicating information that can be abstract, esoteric, or perhaps invisible to the human or robotic eye (Keefe et al., 2005) particularly in this area of multidimensional visualization.

One important factor for the accessibility of 3D models, particularly with non-experts, is the availability of open access or creative commons data. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)3 and the Smithsonian Institution (Pearlman, 2020), for example, each maintains open access or public domain databases of 3D objects, ranging from supernova remnants to geological maps of the Apollo lunar landing sites. Open access and creative commons materials can reduce complexities or legalities regarding the adaptation of content to customized learning experiences for multiple audiences (Zhang et al., 2020). Flexible, customizable materials, derived from openly accessible materials, can potentially improve experiences for all learners, particularly for those with special access requirements (Zhang et al., 2020).

Once a 3D visualization has been created, there are myriad options for how to output that data into a usable product, specific to an intended audience. This underlines the importance of understanding and establishing pipelines in creating 3D data sets, whether ultimately working with files types from .vtk to .obj to .stl. to .unity3d or beyond, for scientific research or for scientific engagement. Narrative information should be provided to interpret context and scale.

Preliminary astrophysical VR applications of simulated worlds (such as Farr et al., 2009) through recent astronomical VR experiences as individual applications (e.g., Russell et al., 2017; Arcand et al., 2018; Ferrand and Warren, 2018; Chandra X-ray Observatory, 2020b), include artistically illustrated worlds, simulated data mapped to astronomical observations, and three-dimensional models derived from scientific observations. Users can comb Martian surfaces based on observational data from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2017), travel to the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets via scientifically-influenced 3D artists’ impressions that were converted into VR applications (NASA, 2019), and explore the solar surface based on observational data from the Hinode spacecraft (Hinode Science Center at NAOJ, 2018). Explorers equipped with emerging technologies can also virtually walk inside the remains of an exploded star (Arcand et al., 2018) or experience a spiral galaxy like NGC 3198 via radio data cubes (Ferrand et al., 2016). Computational models and simulations constrained by scientific observations also provide numerous options for VR application development, including simulation and time-domain based applications of Sagittarius A, the supermassive black hole at our Galactic Center (Russell, 2017; Davelaar et al., 2018).

Expert analysis of scientific data in XR spaces can provide active and immersive simulations of astrophysical topics like photometry of the billions of stars in our Milky Way (Ramírez et al., 2019). And at even greater scales, cosmological topics such as dark matter can be rendered in VR with particular attention towards accessibility, for example haptic (vibrational) cues that work together with wheelchair use (Aviles, 2018). Current research into, and evaluation of, such immersive projects that take advantage of human perception in 3D spaces are investigating potential outcomes in enabling better detections and manipulations of large or complex data sets on behalf of the scientist (Ferrand et al., 2016). Additionally, in geology and geophysics there are projects across topographical maps (Woods et al., 2016), geological surveys (Westhead et al., 2013) and other ways to provide 3D data in a digestible way to “enable non-expert users to begin to interact with a complex science in an expert way which was not possible for previous generations” (Westhead et al., 2013, p. 189; see e.g., Mathiesen et al., 2012; Gerloni et al., 2018; Trexler et al., 2018).

Data sonification is another example of a potential extension or output of 3D data sets. Sonification can help improve upon analysis of big data through vision alone by taking advantage of the unique capacities of sound to provide information from different dimensions simultaneously, with quick interaction or playback (Cooke et al., 2017). This strategy can work with XR in order to speedily evaluate features of 3D data (Ribeiro et al., 2012). Díaz-Merced (2013) demonstrated that listening function can be improved through targeted interventions as applied to such data sonification outputs. Beyond data sonification there are additional 3D visualization outputs and enhancements that can be considered to reach specific audiences, from holograms (Royal Astronomical Society, 2019) and haptic information (Isenberg, 2013; Trotta et al., 2020) to tactile tablets (Touch Graphics, Inc., 2015) and multisensory experiences (Najjar, 2020).

At this time, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to result in monumental challenges that reach nearly every aspect of life. The pandemic does not spare the fields of science research, visualization or engagement, but instead presents particular obstacles—and opportunities—to these areas. Some of the recent difficulties related to the use of 3D printed materials include reliance on tactile surfaces while combating a virus that can spread through surface contact (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020) and a reduction in tangible resources presently available to populations who need enhanced accessibility, such as BVI audiences (McEvoy, 2020). However, due to social distancing there is now a greater demand than ever before in modern times for remote learning and work. The 3D astrophysical and geophysical models, prints, and virtual spaces could serve scientists, educators, learners and others who are unable to spend their usual time in physical settings. We propose partnering with groups who both advocate for and engage with affected audiences so the science and engagement communities can best serve the needs of their audiences.

KA, as the principal investigator, provided the main points, literature references and scientific topics, as well as technical writings for the article. SP, as the research assistant, formatted the outline and citations, organized the literature review, and provided summative text on specific subsections. MW provided detailed editing and drafting, gave input on overall organization, and wrote summary texts as needed.

This paper was written with funding from NASA under contract NAS8-03060 with the authors working for the Chandra X-ray Observatory. NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Chandra X-ray Center controls science and flight operations from Cambridge and Burlington, MA.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Authors gratefully acknowledge Lisa Frattare for her stellar copy editing skills. The Authors also acknowledge the Chandra communications and public engagement group members, NASA’s Universe of Learning, and the many scientists, technologists and researchers that have contributed to the ever growing library of 3D printed objects of our Universe.

1https://medeng.jpl.nasa.gov/covid-19/respirators/ (Accessed June 26, 2020).

2http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/vr (Accessed June 17, 2020).

3https://nasa3d.arc.nasa.gov/models (Accessed June 16, 2020).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feart.2020.590295/full#supplementary-material

ADA National Network (2019). What is the Americans with disabilities act (ADA)? Available at: https://adata.org/learn-about-ada (Accessed July 26, 2019).

Alesina, F., Cabot, F., Buchschacher, N., and Burnier, J. (2018). “Exoplanets data visualization in multi-dimensional plots using virtual reality in DACE,” in Astronomical data analysis software and systems XXVII. Proceedings of a Conference Held at Sheraton Santiago Convention Center, Santiago de Chile, Chile, October 22−26, 2017 (College Park, MD: Astronomical Society of the Pacific). Available at: http://aspbooks.org/publications/523/025.pdf (Accessed January 1, 2019).

Arcand, K. K., Edmonds, P., and Watzke, M. (2020). X-Ray universe: make a pulsar: crab nebula in 3D. Cambridge, MA: Chandra X-ray Center Available at: https://chandra.cfa.harvard.edu/deadstar/crab.html (Accessed January 10, 2020).

Arcand, K. K., Jiang, E., Price, S., Watzke, M., Sgouros, T., and Edmonds, P. (2018). Walking through an exploded star: rendering supernova remnant Cassiopeia A into virtual reality. Commun. Astron. Public J. 1 (24), 17–24.

Arcand, K. K., Jubett, A., Watzke, M., Price, S., Williamson, K. T. S., and Edmonds, P. (2019). Touching the stars: improving NASA 3D printed data sets with blind and visually impaired audiences. J. Sci. Commun. 18 (4), A01. doi:10.22323/2.18040201

Arcand, K. K., Watzke, M., DePasquale, J., Jubett, A., Edmonds, P., and DiVona, K. (2017). Bringing cosmic objects down to Earth: an overview of 3D modeling and printing in astronomy. Commun. Astron. Public J. 1 (22), 14–20.

Argudo-Fernández, M., Bonne, N., Krawczyk, C., Gupta, J., Rodríguez Quiroz, A., Longa-Peña, P., et al. (2020). Highlights in the implementation of the Astro BVI project to increase quality education and reduce inequality in Latin America. Commun. Astron. Public J. 1 (27), 35–38.

Aviles, R. B. (2018). Perception ultra: using virtual reality technology to visualize astronomical data. Undergraduate honors thesis. Oakland (CA): University of California.

Baracaglia, E., and Vogt, F. P. A. (2020). E0102-VR: exploring the scientific potential of virtual reality for observational astrophysics. Astron. Comp. 30, 100352. doi:10.1016/j.ascom.2019.100352

Beck-Winchatz, B., and Riccobono, M. A. (2008). Advancing participation of blind students in science, technology, engineering, and math. Adv. Space Res. 42 (11), 1855–1858. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2007.05.080

Bonne, N. J., Gupta, J. A., Krawczyk, C. M., and Masters, K. (2018). Tactile Universe makes outreach feel good. Astron. Geophys. 59 (1), 1.30–1.33. doi:10.1093/astrogeo/aty028

Brown, C. (2017). 3D printing set to revolutionize medicine. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 189 (29), E973–E974. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1095442

Carneiro, C. D. R., Santos, K. M., Lopes, T. R., dos Santos, F. C., Silva, J. V. L. da., and Harris, A. L. N. de. C. (2018). Three-dimensional physical models of sedimentary basins as a resource for teaching-learning of geology. Terrae Didatica 14 (4), 379–384. doi:10.20396/td.v14i4.8654098

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): people with disabilities. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-disabilities.html (Accessed April 7, 2020).

Chandra X-ray Observatory (2017). V745 Sco: two stars, three dimensions, and oodles of energy [Press release]. Available at: https://chandra.si.edu/photo/2017/v745/index.html (Accessed September 18, 2017).

Chandra X-ray Observatory (2019). The clumpy and lumpy death of a star [Press release]. Available at: https://chandra.si.edu/photo/2019/tycho/ (Accessed October 17, 2019).

Chandra X-ray Observatory (2020a). Stellar explosions and jets showcased in new three dimensional visualizations [Press release]. Available at: https://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2020/3dmodels/ (Accessed January 29, 2020).

Chandra X-ray Observatory (2020b). A new Galactic Center adventure in virtual reality [Press release]. Available at: https://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2020/gcenter/ (Accessed June 2, 2020).

Chandrashekar, S. (2018). GAAD: how virtual reality can transform the way people with disabilities learn. Desire2Learn Available at: https://www.d2l.com/corporate/blog/gaad-virtual-reality-people-disabilities-learn/ (Accessed May 17, 2018).

Charnay, B., Forget, F., Tobie, G., Sotin, C., and Wordsworth, R. (2014). Titan’s past and future: 3D modeling of a pure nitrogen atmosphere and geological implications. Icarus 241, 269–279. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.07.009

Christian, C. A., Nota, A., Greenfield, P., Grice, N., and Shaheen, N. (2015). You can touch these! Creating 3d tactile representations of hubble space telescope images. J. Rev. Astron. Edu. Outreach 3, 282.

Clements, D. L., Sato, S., and Fonseca, A. P. (2016). Cosmic sculpture: a new way to visualise the cosmic microwave background. Eur. J. Phys. 38 (1), 015601. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/38/115601

Comparato, M., Beccani, U., Costa, A., Larsson, B., Garilli, B., Gheller, C., et al. (2007). Visualization, exploration, and data analysis of complex astrophysical data. Pub. Astron. Soc. Pac. 119, 898–913. doi:10.1086/ 5213

Cooke, J., Díaz-Merced, W., Foran, G., Hannam, J., and Garcia, B. (2017). Exploring data sonification to enable, enhance, and accelerate the analysis of big, noisy, and multi-dimensional data: workshop 9. Proc. Int. Astron. Union 14, 251–256. doi:10.1017/S1743921318002703

Cornet, T., Fleurant, C., Seignovert, B., Cordier, D., Bourgeois, O., Le Mouelic, S., et al. (2017). Dissolution on Saturn’s moon Titan: a 3D karst landscape evolution model.European Geosciences Union (EGU) general assembly 2017, Vienna, Austria,April 23–28, 2017 [Conference presentation abstract]. Available at: https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU2017/EGU2017-12475.pdf (Accessed April 23–28, 2017)

Davelaar, J., Bronzwaer, T., Kok, D., Younsi, Z., Moscibrodzka, M., and Falcke, H. (2018). Observing supermassive black holes in virtual reality. Comput. Astrophys. Cosmol. 5, 1. doi:10.1186/s40668-018-0023-7

De Kestelier, X., Dini, E., Cesaretti, G., Colla, V., and Pambaguian, L. (2015). The design of a lunar outpost. Foster + Partners Available at: https://www.fosterandpartners.com/media/2634652/lunar_outpost_design_foster_and_partners.pdf (Accessed January 31, 2015).

DeLaney, T., Rudnick, L., Stage, M. D., Smith, J. D., Isensee, K., Rho, J., et al. (2010). The three-dimensional structure of Cassiopeia A. Astrophys. J. 725 (2), 2038–2058. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/725/2/2038 |

Díaz-Merced, W. L. (2013). Sound for the exploration of space physics data. PhD dissertation. Glasgow (Scotland): University of Glasgow.

Díaz-Merced, W. L. (2014). Making astronomy accessible for the visually impaired. Voices Available at: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/voices/making-astronomy-accessible-for-the-visually-impaired/ (Accessed September 22, 2014).

Díaz-Merced, W. L., Candey, R. M., Brickhouse, N., and Schneps, M. (2011). Sonification of astronomical data. Proc. Int. Astron. Union 7, 133–136. doi:10.1017/S1743921312000440

Diemer, B., and Facio, I. (2017). The fabric of the universe: exploring the cosmic web in 3D prints and woven textiles. Pub. Astron. Soc. Pac. 129, 058013. doi:10.1088/1538-3873/aa6a46

Dolphin, G., Dutchak, A., Karchewski, B., and Cooper, J. (2019). Virtual field experiences in introductory geology: addressing a capacity problem, but finding a pedagogical one. J. Geosci. Educ. 67 (2), 114–130. doi:10.1080/10899995.2018.1547034

Donalek, C., Djorgovski, S. G., Cioc, A., Wang, A., Zhang, J., Lawler, E., et al. (2014). Immersive and collaborative data visualization using virtual reality platforms. arXiv [Preprint]. Available at: https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1410/1410.7670.pdf (Accessed October 2014).

Edwards, L., Sims, M., Kunz, C., Lees, D., and Bowman, J. (2005). “Photo-realistic terrain modeling and visualization for Mars exploration Rover science operations,” in 2005 IEEE international conference on systems, man, and cybernetics, Waikoloa, HI, October 10–12, 2005 [Paper presentation]. Available at: (Accessed October 12, 2005).

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSMC.2005.1571341CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ellison, D. (2014). Gale crater. NASA 3D resources. Available at: https://nasa3d.arc.nasa.gov/detail/gale-crater (Accessed June 26, 2014).

Eriksson, U. (2019). Disciplinary discernment: reading the sky in astronomy education. Phys. Rev. Phys. Edu. Res. 15, 010133. doi:10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.15.010133

Eriksson, U., Linder, C., Airey, J., and Redfors, A. (2014). Who needs 3D when the universe is flat? Sci. Educ. 98 (3), 412–442. doi:10.1002/sce.21109

European Southern Observatory (2019). A dark tour of the Universe [Press release]. Available at: https://www.eso.org/public/announcements/ann19045/ (Accessed September 13, 2019).

Everett-Green, R. (2013). A 3-D machine that prints skin? How burn care could be revolutionized. The Globe and Mail. Available at: January 20. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitnesshealth/a-3-d-machine-that-prints-skin-how-burn-care-could-be-revolutionized/article7540819/ (Accessed January 20, 2013)

Farr, W., Hut, P., Ames, J., and Johnson, A. (2009). An experiment in using virtual worlds for scientific visualization of self-gravitating systems. J. Vir. Worlds Res. 2 (3), 1941–8477. doi:10.4101/JVWR.V2I3.659

Ferrand, G., English, J., and Irani, P. (2016). “3D visualization of astronomy data cubes using immersive displays,” in Canadian Astronomical Society Conference (CASCA), Winnipeg, Manitoba, May 30–June 2, 2016 [Paper presentation]. Available at: http://hci.cs.umanitoba.ca/assets/publication_files/Gilles.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2016).

Ferrand, G., and Warren, D. (2018). Engaging the public with supernova and supernova remnant research using virtual reality. Comm. Astron. Public J. 1 (24), 25–31.

Ferrand, G., Warren, D. C., Ono, M., Nagataki, S., Röpke, F. K., and Seitenzahl, I. R. (2019). From supernova to supernova remnant: the three-dimensional imprint of a thermonuclear explosion. Astrophys. J. 877 (2), 17. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab1a3d

Florinsky, I. V., and Filippov, S. V. (2017). A desktop system of virtual morphometric globes for Mars and the Moon. Planet. Space Sci. 137, 32–39. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2017.01.005

Gerloni, I. G., Carchiolo, V., Vitello, F. R., Sciacca, E., Becciani, U., Costa, A., et al. (2018). “Immersive virtual reality for earth sciences,” in 2018 Federated conference on computer science and information systems (FedCSIS), Poznan, Poland, September 9–12, 2018 [Paper presentation]. Available at: (Accessed September 9–12, 2018).

Grice, N., Christian, C., Nota, A., and Greenfield, P. (2015). 3D printing technology: a unique way of making hubble space telescope images accessible to non-visual learners. J. Blindness Innov. Res. 5 (1).

Grove, E. (2020). 3D anatomic modeling lab prints model of virus that causes COVID-19 [Press release]. Mayo Clinic Available at: https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/3d-anatomic-modeling-lab-prints-model-of-virus-that-causes-covid-19/ (Accessed March 24, 2020).

Gwinner, K., Hauber, E., Jaumann, R., Michael, G., Hoffman, H., and Heipke, C. (2015). Global topography of Mars from High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) multi-orbit data products: the first quadrangle (MC-11E) and the landing site areas of ExoMars,” in European Geosciences Union (EGU) general assembly 2015, Vienna, Austria, April 12–17, 2015 [Conference presentation abstract]. Available at: https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU2015/EGU2015-13158.pdf (Accessed April 12–17, 2015).

Hasiuk, F. J., Harding, C., Renner, A. R., and Winer, E. (2017). TouchTerrain: a simple web-tool for creating 3D-printable topographic models. Comput. Geosci., 109, 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.cageo.2017.07.005

Hinode Science Center at NAOJ (2018). VR app “Excursion to the Sun” has been released! [Press release]. Available at: https://hinode.nao.ac.jp/en/news/notice/vr-app-excursion-to-the-sun-has-been-released/ (Accessed July 9, 2018).

Hurt, R., Wyatt, R., Subbarao, M., Arcand, K., Faherty, J. K., Lee, J., et al. (2019). Making the case for visualization [White paper]. arXiv, [Preptint]. Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1907.10181.pdf (Accessed July 24, 2019).

Isenberg, T. (2013). “Position paper: touch interaction in scientific visualization,” in Proceedings of the workshop on data exploration on interactive surfaces. Editors P. Isenberg, S. Carpendale, T. Hesselman, T. Isenberg, and B. Lee, (HAL), 24–27.

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2017). Take a walk on Mars - in your own living room [Press release]. Available at: https://www.nasa.gov/feature/jpl/take-a-walk-on-mars-in-your-own-living-room (Accessed October 19, 2017).

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2020). Operate a great observatory with new VR experience [Press release]. Available at: http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/news/2222-ssc2020-05-Operate-a-NASA-Great-Observatory-With-New-VR-Experience (Accessed January 24, 2020).

Keefe, D. F., Karelitz, D. B., Vote, E. L., and Laidlaw, D. H. (2005). Artistic collaboration in designing VR visualizations. IEEE Comp. Grap. Appl. 25 (2), 18–23. doi:10.1109/MCG.2005.34

Kim, R. (2018). Asteroid vesta. NASA 3D resources. Available at: https://nasa3d.arc.nasa.gov/detail/asteroid-vesta (Accessed November 5, 2018).

Koelemeijer, P., Winterbourne, J., Toussaint, R., and Zaroli, C. (2019). “3D printing the world: developing geophysical teaching materials and outreach packages,” in AGU 2019 fall meeting, San Francisco, CA, December 9–13, 2019 [Poster presentation]. Available at: (Accessed December 13, 2019).

https://doi.org/10.1002/essoar.10501627.1CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Korycansky, D. G., Zahnle, K. J., and Mac Low, M.-M. (2002). High-resolution simulations of asteroids into the Venusian atmosphere II: 3D models. Icarus 157 (1), 1–23.

Kyriakopoulos, C. (2019). 3D printing: a remedy to common misconceptions about earthquakes. Seismol Res. Lett. 90 (4), 1689–1691. doi:10.1785/0220190121

Löwe, P., and Klump, J. (2013). “3D printouts of geological structures, land surfaces and human interaction - an emerging field for science communication,” in 8th international symposium on archaeological mining history, Hesse, Germany, July 1–2, 2013 [Paper presentation]. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Peter_Loewe/publication/237079004_3D_Printouts_of_geological_structures_land_surfaces_and_human_interaction_-_an_emerging_field_in_science_communication/links/00b7d51b5c26fc35fe000000/3D-Printouts-of-geological-structures-land-surfaces-and-human-interaction-an-emerging-field-in-science-communication.pdf (Accessed 2013).

Madura, T. I. (2017). A case study in astronomical 3-D printing: the mysterious η Carinae. Publ. Astron. Soc. Public 129 (975), 058011. doi:10.1088/1538-3873/129/975/058011

Madura, T. I., Clementel, N., Gull, T. R., Kruip, C. J. H., and Paardekooper, J.-P. (2015). 3D printing meets computational astrophysics: deciphering the structure of η Carinae’s inner colliding winds. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 449 (4), 3780–3794. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv422

Mars Exploration Rovers (2014). Replicating a rock on Mars [Press release]. NASA Available at: https://mars.nasa.gov/mer/newsroom/pressreleases/20140407a.html (Accessed April 17, 2014).

Mathiesen, D., Myers, T., Atkinson, I., and Trevathan, J. (2012). “Geological visualisation with augmented reality,” in 15th international conference on network-based information systems, Melbourne, Victoria, September 26–28, 2012 [Paper presentation]. Available at: (Accessed September 2012).

https://doi.org/10.1109/NBiS.2012.199CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

McEvoy, J. (2020). With a Braille printing press in his garage, this Sonoma Teacher goes the extra mile. KQED Available at: https://www.kqed.org/news/11818669/with-a-braille-printing-press-in-his-garage-this-sonoma-teacher-goes-the-extra-mile (Accessed May 24, 2020).

McLeod, A. F., Dale, J. E., Ginsburg, A., Ercolano, B., Gritschneder, M., Ramsay, S., et al. (2015). The pillars of creation revisited with MUSE: gas kinematics and high-mass stellar feedback traced by optical spectroscopy. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 450 (1), 1057–1076. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv680

McMahon, D. D., and Walker, Z. (2019). Leveraging emerging technology to design an inclusive future with universal design for learning. Center Educ. Policy Stud. J. 9 (3), 75–93. doi:10.26529/cepsj.639

Menke, K., Beckmann, J., and Weber, P. (2020). “39. Universal design for learning in augmented and virtual reality trainings,” in Universal access through inclusive instructional design. Editors S. L. Gronseck, and E. M. Dalton, (Routledge), 294–304.

Molitch-Hou, M. (2020). 3D printing and COVID-19, May 5, 2020 update. 3DPrint.com Available at: https://3dprint.com/266910/3d-printing-and-covid-19-may-5-2020-update/ (Accessed May 5, 2020).

Najjar, R. (2020). Extended Reality (XR) explained through the 5+1 senses. MediumAvailable at: https://uxdesign.cc/xr-through-5-1-senses-f396acf8a89f (Accessed February 15, 2020).

NASA (2019). ‘NASA selfies’ and TRAPPIST-1 VR apps now available [Press release]. Available at: https://www.nasa.gov/feature/jpl/nasa-selfies-and-trappist-1-vr-apps-now-available (Accessed June 21, 2019).

National Federation of the Blind & Finkelstein (1994). Common eye conditions and causes of blindness in the United States. MD, United States: National Federation of the Blind.

National Federation of the Blind Jernigan Institute (2009). The Braille literacy crisis in America: facing the truth, reversing the trend, empowering the blind. MD, United States: National Federation of the Blind.

Neitzke Adamo, L., Criscione, J., Irizarry, P., Pagenkopf, L., and Hayden, D. (2019). “Utilizing photogrammetry and 3D printers to create inclusive natural history tours and activities for the visually impaired at the Rutgers Geology Museum,” in Fall meeting 2019, San Francisco, CA, December 9–13. 2019 (American Geophysical Union) [Conference presentation abstract]. Available at: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2019AGUFMED33A.02N/abstract (Accessed December 2019).

Olshannikova, E., Ometov, A., Koucheryavy, Y., and Olsson, T. (2015). Visualizing big data with augmented and virtual reality: challenges and research agenda. J. Big Data 2, doi:10.1186/s40537-015-0031-2

Orlando, S., Miceli, M., Petruk, O., Ono, M., Nagataki, S., Aloy, M. A., et al. (2018). 3D MHD modeling of the expanding remnant of SN 1987A. Role of magnetic field and non-thermal radio emission. Astron. Astrophys. 622, A73. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201834487

Orlando, S., Miceli, M., Pumo, M. L., and Bocchino, F. (2016). Modeling SNR Cassiopeia A from the supernova explosion to its current age: the role of post-explosion anisotropies of ejecta. Astrophys. J. 822 (1). doi:10.3847/0004-637X/822/1/22

Orlando, S., Pillitteri, I., Bocchino, F., Daricello, L., and Leonardi, L. (2019). 3DMAP-VR, a project to visualize 3-dimensional models of astrophysical phenomena in virtual reality. Res. Notes AAS 3 (11). doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ab5966/meta

Pauwels, L. (2020). “On the nature and role of visual representations in knowledge production and science communication,” in Science communication: book 17. Handbooks of communication science [HoCS]. Editors A. Leßmöllman, M. Dascal, and T.Gloning, 235–256.

Pearlman, R. Z. (2020). Smithsonian open access launches with space artifact 2D and 3D images. Space.com Available at: https://www.space.com/smithsonian-open-access-space-artifacts.html (Accessed February 28, 2020).

Pearson, D. (2020). Virtual reality shows COVID-19 lungs in vivid detail. AI in Healthcare Available at: https://www.aiin.healthcare/topics/diagnostic-imaging/virtual-reality-covid-19-lungs (Accessed April 2, 2020).

Pomarède, D., Tully, R. B., Graziani, R., Courtois, H. M., Hoffman, Y., and Lezmy, J. (2020). Cosmicflows-3: the south pole wall. Astrophys. J. 897 (2). doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab9952

Pound, K. S. (2019). ‘Seeing’ geology: development of learning materials for visually impaired students,” in American Geophysical Union, fall meeting 2019, SanFrancisco, CA, December 9–13, 2019 [Conference presentation abstract] Available at: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2019AGUFMIN21B.16P/abstract

Ramírez, E., Núñez, J. G., Hernandez, J., Salgado, J., Mora, A., Lammers, U., et al. (2019). Analysis of astronomical data using VR: the Gaia catalog in 3D,” in Astronomical data analysis software and systems XXVIII. ASP conference series. Editors P. J. Teuben, M. W. Pound, B. A. Thomas, and E. M. Warner, (Astronomical Society of the Pacific), Vol. 523, 21–24.

Rector, T., Arcand, K., and Watzke, M. (2015). Coloring the universe. 1st Edn. University of Alaska Press.

Ribeiro, F., Florencio, D., Chou, P. A., and Zhang, Z. (2012). “Auditory augmented reality: object sonification for the visually impaired,” in 2012 IEEE 14th international workshop on multimedia signal processing (MMSP), Banff, Alberta, September 17–19 2012 [Paper presentation]. Available at: (Accessed September 2012).

https://doi.org/10.1109/MMSP.2012.6343462CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Royal Astronomical Society (2019). 3-D holograms bringing astronomy to life. Phys.org Available at: https://phys.org/news/2019-07-d-holograms-astronomy-life.html (Accessed July 1, 2019).

Russell, C. M. P. (2017). 360-degree videos: a new visualization technique for astrophysical simulations. arXiv [Preprint]. Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1707.06954.pdf (Accessed November 2017).

Russell, C. M. P., Wang, Q. D., and Cuadra, J. (2017). Modelling the thermal X-ray emission around the Galactic Centre from colliding Wolf-Rayet winds. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 464 (4), 4958–4965. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw2584

Smithsonian Institution (2014). Smithsonian directive 215: accessibility for people with disabilities. Available at:airandspace.si.edu/rfp/exhibitions/files/j3-directive-215.pdf (Accessed June 2, 2014).

Steffen, W. (2016). Why 3-D is essential in astronomy outreach. 3D Astrophysics. Available at: https://3dastrophysics.wordpress.com/2016/06/27/why-3-d-is-essential-in-astronomy-outreach/ (Accessed June 27, 2016).

Steffen, W., Koning, N., Wenger, S., Morisset, C., and Magnor, M. (2011). Shape: a 3D modeling tool for astrophysics. IEEE Trans. Visual. Comput. Graph. 17 (4), 454–465. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2010.62

Steffen, W., Teodoro, M., Madura, T. I., Groh, J. H., Gull, T. R., Mehner, A., et al. (2014). The three-dimensional structure of the eta Carinae Homunculus. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 442 (4), 3316–3328. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu1088

Summers, F., Hurt, R., and Wolk, N. (2020). “117.05-a 3D multiwavelength visualization of the Crab Nebula,” in 235th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, Honolulu, HI, January 4–8, 2020 [Conference presentation abstract]. Available at: https://aas.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/AAS235-Meeting-Abstracts.pdf (Accessed January 8, 2020).

Takagishi, K., and Umezu, S. (2017). Development of the improving process for the 3D printing structure. Sci. Rep. 7, 39852. doi:10.1038/srep39852

Touch Graphics, Inc. (2015). Talking tactile tablet 2 (TTT). Availabel at: http://touchgraphics.com/portfolio/ttt/ (Accessed April 2, 2015).

Trexler, C. C., Morelan, A. E., Oskin, M. E., and Kreylos, O. (2018). Surface slip from the 2014 South Napa earthquake measured with structure from motion and 3-D virtual reality. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 5985–5991. doi:10.1029/2018GL078012

Trotta, R. (2018). The hands-on Universe: making sense of the Universe with all your senses. Comm. Astron. Public J. 1 (23), 20–25.

Trotta, R., Hajas, D., Camargo-Molina, J. E., Cobden, R., Maggioni, E., and Obrist, M. (2020). Communicating cosmology with multisensory metaphorical experiences. J. Sci. Comm. 19 (2), N01. doi:10.22323/2.19020801

United Nations Disability, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD), article 21-Freedom of opinion and expression, and access to information. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-21-freedom-of-expression-and-opinion-and-access-to-information.html (Accessed March 30, 2007).

Ustamujic, S., Orlando, S., Bonito, R., Miceli, M., Gómez de Castro, A. I., and López-Santiago, J. (2016). Formation of X-ray emitting stationary shocks in magnetized protostellar jets. Astron. Astrophys. 596, A99. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/01628712

Ustamujic, S., Orlando, S., Bonito, R., Miceli, M., and Gómez de Castro, A. I. (2018). Structure of X-ray emitting jets close to the launching site: from embedded to disk-bearing sources. Astron. Astrophys. 615, A124. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201732391

Weferling, T. (2007). Astronomy for the blind and visually impaired: an introductory lesson. Astron. Educ. Rev. 1 (5), 102–109. doi:10.3847/AER2006006

Westhead, R. K., Smith, M., Shelley, W. A., Pedley, R. C., Ford, J., and Napier, B. (2013). Mobile spatial mapping and augmented reality applications for environmental geoscience. J. Internet Technol. Secured Trans. 2 (1–4), 185–190.

Woods, T. L., Reed, S., Hsi, S., Woods, J. A., and Woods, M. R. (2016). Pilot study using the augmented reality sandbox to teach topographic maps and surficial processes in introductory geology labs. J. Geosci. Educ. 64, 199–214. doi:10.5408/15-135.1

Keywords: 3D printing, 3D visualization, virtual reality, astrophysics, geophysics, science communication, inclusivity

Citation: Arcand KK, Price SR and Watzke M (2020) Holding the Cosmos in Your Hand: Developing 3D Modeling and Printing Pipelines for Communications and Research. Front. Earth Sci. 8:590295. doi: 10.3389/feart.2020.590295

Received: 31 July 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020;

Published: 18 November 2020.

Edited by:

Paula Koelemeijer, Royal Holloway, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Bernhard Maximilian Steinberger, Helmholtz Centre Potsdam, GermanyCopyright © 2020 Arcand, Price and Watzke. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sara R. Price, c2FyYS5wcmljZUBjZmEuaGFydmFyZC5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.