- Quality Department, Emirates Health Services (EHS), Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Objective: This study investigated the common reasons for leaving against medical advice (LAMA) at Emirates Health Services (EHS) by comparing electronic medical records (EMR) with healthcare professionals' (HCPs) stated reasons and understanding the challenges faced by HCPs in such cases. We also explored patient-related factors associated with LAMA based on HCP interviews to improve patients' outcome.

Methods: This mixed-method study used EMR data and HCP interviews from four EHS public hospitals with LAMA rates of >2%. EMR variables, including nationality, personal and social reasons, financial reasons, sex, and triage classifications, were dummy-coded and tested using the chi-squared test. Twenty interviews were conducted and analyzed using thematic analysis (TA).

Results: Quantitative data revealed that 5,521 patients left against medical advice in the four hospitals over 6 months. The average age of these patients was 35.1 years (SD = 22.4), and 61.3% were male. Personal and social reasons accounted for 65.7% of the patients who opted for LAMA, and 69.9% were classified as triage 3. There was a significant association between Emiratis and non-Emiratis LAMA and triage category reasons X2 (1) = 138.1, p ≤ 0.001. The odds ratios indicated that Emiratis with triage 3–5 were 2.7 times more likely to leave (95% confidence interval: 2.37–3.38) than non-Emiratis. TA identified two main themes as strategies for managing LAMA: reasons for LAMA and outcomes of LAMA.

Discussion: The results highlight the perspective of HCPs on the reasons for LAMA, providing insights for developing interventions to influence patient decisions and enhance health outcomes. Interventions may include enhancing HCP-patient communication and educating patients on adherence to medical advice. In conclusion, EHS needs strategies to improve LAMA among patients despite of their nationality.

Introduction

Leaving against medical advice (LAMA) occurs when a patient leaves the hospital before a clinically defined endpoint or against a physician's recommendation (1). Patients who leave against medical advice challenge the services designed to care for them, as well as the facilities that promote continuity and improved quality of care. The prevalence of LAMA hospital discharges accounts for up to 2% of all hospital discharges (2). Alfandre (3) noted that LAMA is a global phenomenon that occurs when patients exit hospitals against doctors' advice to remain in the facility. Whether a patient leaves or is discharged against medical advice can adversely affect health outcomes.

Several studies have explored the potential outcomes of patients opting for LAMA. For example, it has been shown that LAMA can increase mortality and readmission rates (4). Hwang et al. (5) reported that LAMA patients were more likely to be readmitted within 15 days. Numerous factors that contribute to the likelihood of LAMA have been identified (2). Albayati et al. (2) reported that variables such as age, sex, lack of health insurance, substance or alcohol abuse, and mental health issues influenced patients' decisions regarding LAMA. Additionally, dissatisfaction with the care provided has been linked to an increase in LAMA rates (6, 7). Understanding the common factors influencing LAMA decisions in Emirates Health Services (EHS) facilities is crucial.

This study aimed to understand the risks associated with LAMA by investigating the demographic data of LAMA patients in public EHS hospitals. Using a sequential mixed-method design, this study examined factors contributing to LAMA and health care providers' (HCPs) perceptions of the common reasons for patients leaving against medical advice at EHS facilities using data from EHS Electronic Medical Records (EMRs).

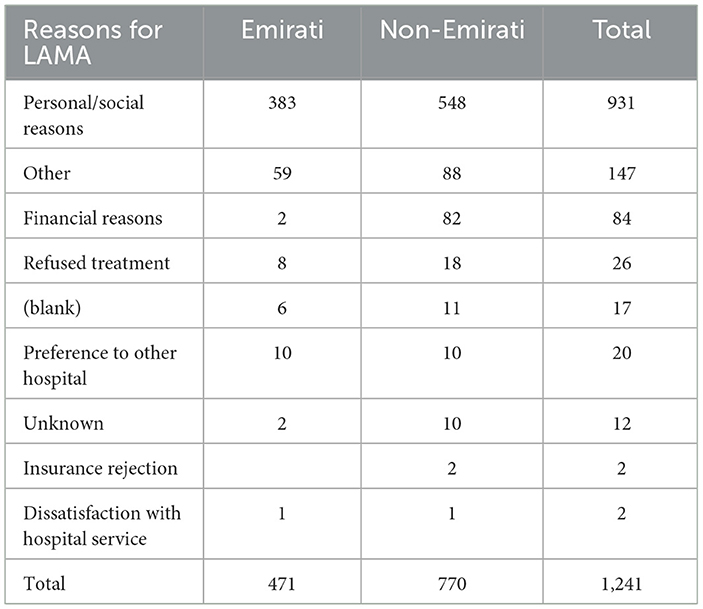

In EHS hospitals, patients who opt for LAMA are asked for the reasons behind their decisions. According to the EHS policy, HCPs document why patients choose to leave against medical advice and educate them about the risks associated with inadequate treatment. After the patient signs the LAMA Form, a thorough discharge procedure is followed, and the patient is provided with a complete discharge summary. In January 2023, a report was extracted from the EMRs to understand the most common factors leading to LAMA. The results indicated that most patients left for personal or social reasons (Table 1).

Personal and social reasons suggest social or domestic concerns. It often means that patients might have a family member to care for, preventing them from accepting the offered treatment. However, some reasons documented in the EMR need more sufficient information. For instance, 176 patients left for unidentified reasons such as “other,” “unknown,” and “blank”. Although interviewing patients may provide additional insights into LAMA, tracking patients after they decide to leave the hospital is challenging. Hence, this study targets a multidisciplinary group of HCPs to understand the common reasons they encounter for LAMA. It aimed to further explore HCPs' awareness of these reasons by conducting in-depth semi-structured interviews.

Patients' nationality can affect the frequency of LAMA. Most emergency doctors at EHS hospitals perceive that expatriates have a higher frequency of LAMA due to financial obligations if triaged in categories three to five. The new EHS legislation mandates non-Emiratis to pay for emergency health services if triaged in classes three to five. At the same time, triage one and two are considered critical and require immediate care without financial responsibilities. Therefore, the study aims to present findings to EHS leadership and discuss strategies to positively impact the total number of LAMA cases in EHS hospitals. It seeks to assist policymakers by providing empirical evidence for effective policymaking.

Aim and hypotheses

This study compared the reasons documented in the EMR system with those expressed by HCPs. The primary objective was to explore the prevalence of LAMA and its underlying causes as perceived by the HCPs in the four hospitals. This research incorporates six-month retrospective data from EMRs (i.e., January–June 2023) to better understand LAMA causes and enable comparison with HCP perceptions in EHS hospitals. The second objective of this study is to explore common reasons that motivate patients visiting the EHS emergency department to LAMA by interviewing personnel working in EHS hospitals with an average LAMA rate of 2%. By applying a mixed-method study, we aim to identify strategies to reduce the likelihood and health consequences of LAMA in EHS.

Methods

This study employed an explanatory sequential mixed methods design to address the lack of published studies on LAMA in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The study consisted of quantitative and qualitative phases that were conducted sequentially. The first phase examined the prevalence of LAMA in EHS hospitals using demographic data extracted from the EMRs. The study utilizes data from the Wareed EMR system (such as Oracle Cerner), implemented across all EHS facilities. When a patient chooses to leave the hospital against medical advice, the attending physician evaluates the reasons for their decision and discusses alternative options with them. Physicians are required to complete the LAMA (Leaving Against Medical Advice) documentation in Wareed and have it signed by the patient or their family members.

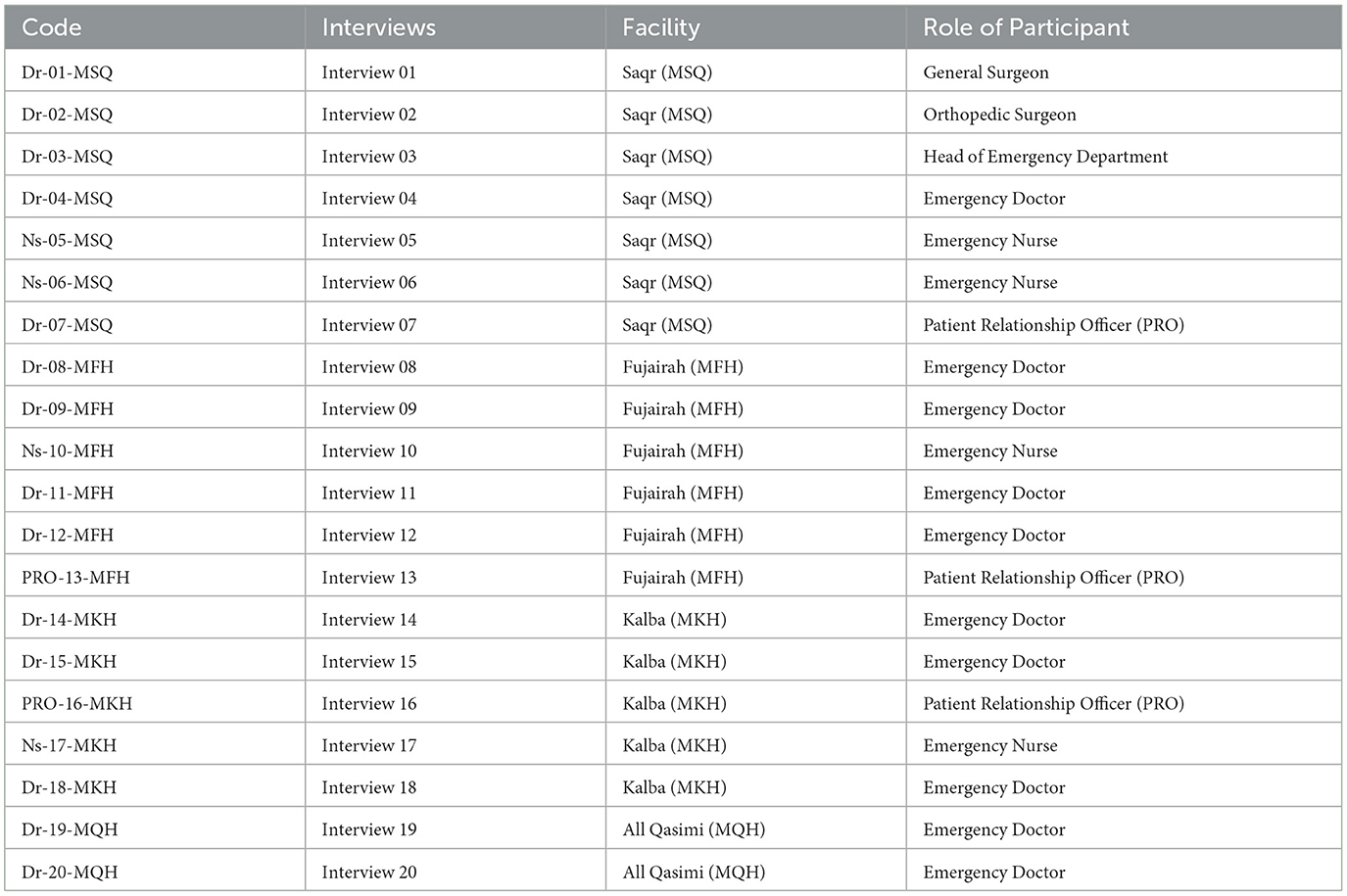

These data included age, sex, nationality, and reasons for LAMA. The second phase consisted of interviews with multidisciplinary HCPs using semi-structured questions to understand their perceptions of LAMA. Three researchers conducted one-on-one semi-structured interview sessions with participants in a private and comfortable setting. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed for analysis. Participants' anonymity was maintained using a unique coding system. For example, the code “Dr-01-MXH” was assigned to the first doctor interviewed at a hospital.

Study population

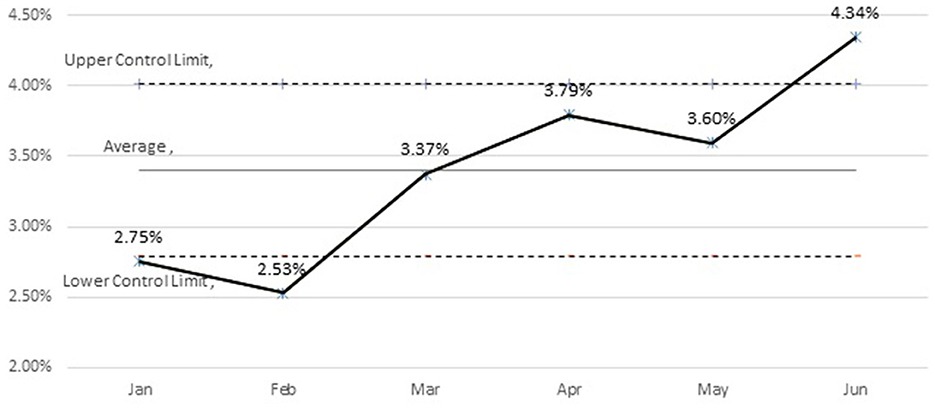

This study targeted four public hospitals within the EHS, each with an average LAMA rate of 2%. These included Al-Qassimi Hospital (MQH) with a LAMA rate of 4.7%, Fujairah Hospital (MFH) at 3.9%, Saqr Hospital (MSQ) at 2.4%, and Kalba Hospital (MKH) at 2.7%. The quantitative phase involved extracting data from the EMR for a period of 6 months prior to interviewing the participants, specifically from January to June 2023. Subsequently, 20 semi-structured interviews were conducted with a diverse group of HCPs at the selected facilities.

Measures

Quantitative data included patient demographics and reasons for LAMA, such as medical record numbers, sex, nationality, age, facility, reasons for LAMA, and triage classification. In this study, nationalities were categorized as Emirati or non-Emirati to compare personal, social, and financial reasons for LAMA. In EHS, patients choose to leave against medical advice for many reasons, including personal and social reasons and pressing social or domestic concerns. It often means that patients might have a family member to care for them, preventing them from accepting the offered treatment. Additionally, the triage group was further divided into two groups: 1–2 and 3–5. The new EHS legislation requires non-Emiratis to pay for health services if they are triaged in classes 3–5. Hence, we hypothesized a higher likelihood of LAMA among non-Emirati patients triaged in classes 3–5. In the chi-squared test, the variables were dummy coded: nationality (Emirati: 1, non-Emirati: 0), sex (male: 1, female: 0), personal or social reasons (personal or social: 1, other: 0), financial reasons (financial: 1, other: 0), and triage classification (Triage 3–5: 1, Triage 1–2: 0). In EHS, patients mention the reasons behind their decision to leave against medical advice. Often personal and social obligations are given as a reason, including.

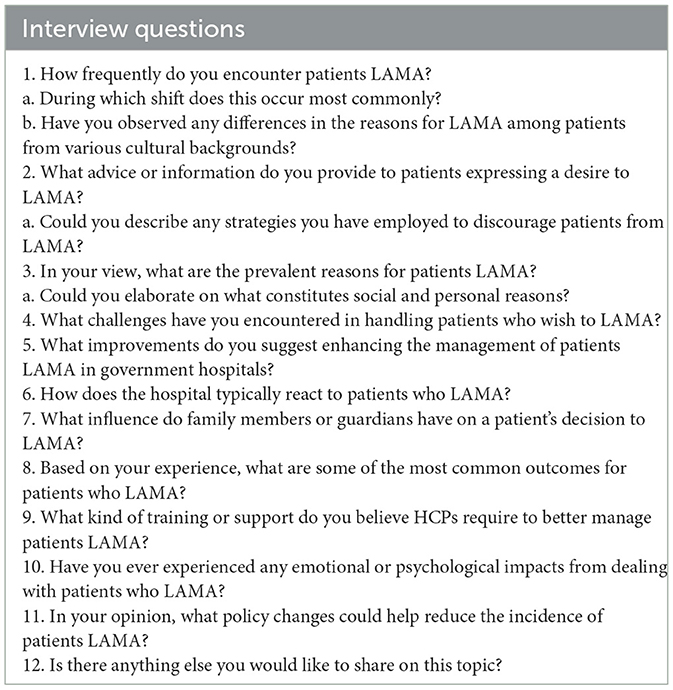

Qualitative interviews followed EMR data extraction to explore the common reasons for LAMAs and their impact on patients and staff. Interviewers gave participants information sheets that described the study's purpose and asked them to sign a consent form before the interview began. The study used twelve semi-structured questions (Table 2) focusing on common factors influencing patients' decision to leave AMA. The questions were structured according to the frequency of HCPs encountering LAMA and why patients leave against medical advice in EHS hospitals. Furthermore, questions probed work-related changes to improve the management of patients who leave against medical advice. Each interview lasted 20–30 min. Table 2 outlines the questions structured based on EMR-extracted common reasons. This study complied with the ethical guidelines of the UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention (MOHAP/DXP-REC/MMM/No. 56/2023).

Data analysis

Quantitative data were extracted from an online platform and imported into IBM SPSS software (version 29) for analysis, which included descriptive frequencies and the chi-squared test. The chi-squared test was used to statistically compare two categorical variables: the proportion of patients who left against medical advice regarding various variables.

Qualitative data were analyzed using Braun and Clarke's (8) (2006) thematic analysis approach. This method facilitated the identification of common themes and patterns within the participants' responses. The findings are illustrated with quotes from participants to substantiate the identified themes.

Three researchers conducted interviews using uniform questions. A separate researcher transcribed all recordings. Two researchers coded the content and collaborated to extract and formulate themes. The team deliberated and reached a consensus on the final themes. Given that this study employed a mixed-methods approach, convergence assessment, also known as triangulation (9), was utilized. This process assessed the findings based on two distinct data points to ensure a comprehensive analysis. We performed an independent data analysis and triangulated the findings to view LAMA in the selected hospitals comprehensively.

Results

Quantitative data

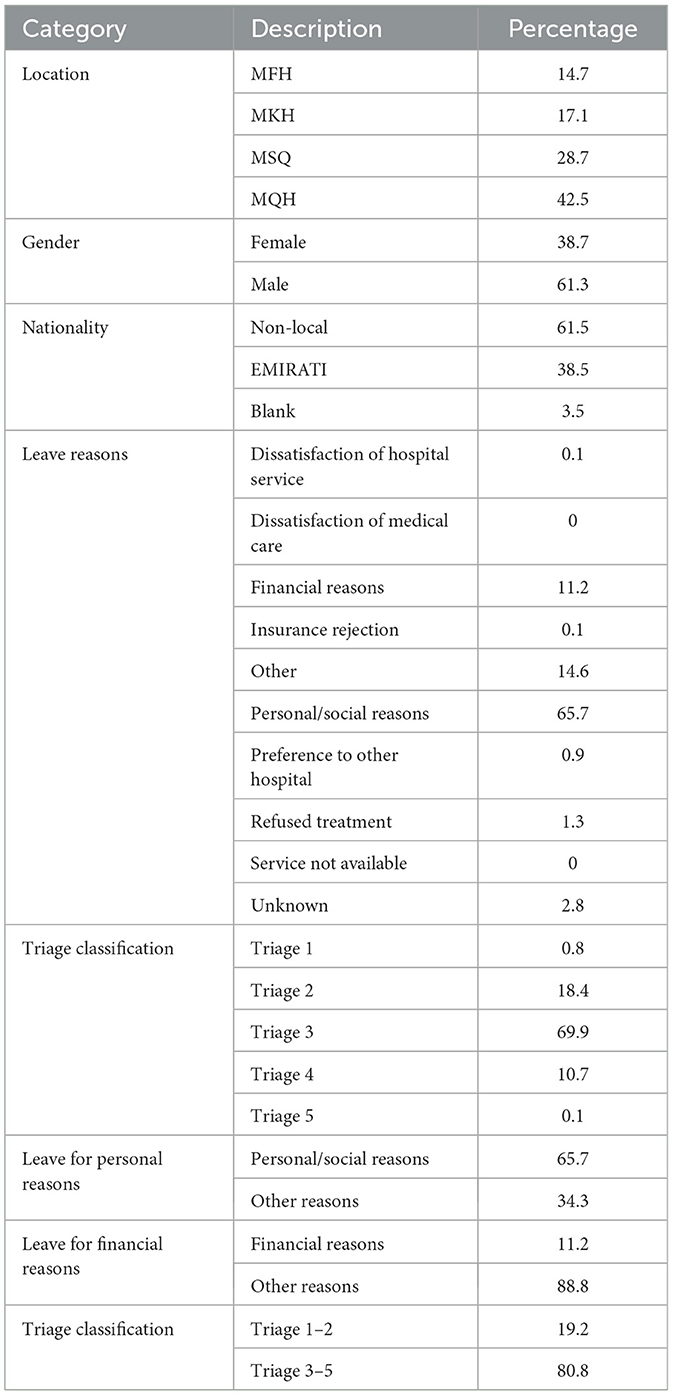

The EMR data included 4,521 patients who left against medical advice from January to June 2023. We included all patients who opted for LAMA to increase the strength of the data and avoid bias related to sampling techniques. Figure 1 the average LAMA percentages across four hospitals. LAMA patients represented 72 nationalities. UAE nationals had the highest LAMA percentage (38.5 %), followed by Pakistani (13.2%) and Indian (10.3%) nationals. For the chi-squared test, the nationality variables were coded as Emirati (1) and non-Emirati (0), comprising 39.1% and 60.9% of the sample, respectively. The mean patient age was 35.1 years (SD = 22.4); 61.3% were male, 65.7% left for personal and social reasons, and 69.8% were triage 3. Table 3 presents the patients' descriptive data.

The chi-squared test was conducted to assess the frequency of patients who left against medical advice. Initially, the odds ratios (ORs) for Emirati LAMA patients in triage 3–5 were tested. Results indicated a significant association between Emirati and non-Emirati LAMA patients and triage categories, χ2 (1) = 138.1, p < 0.001. The odds ratios indicated that Emiratis with triage 3–5 who left against medical advice were 2.7 times more likely (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.37–3.38) than non-Emiratis. Given that personal/social reasons constituted the highest LAMA percentage (69.8%), the association of sex with LAMA for personal/social reasons was tested, showing significant association (χ2 [1] = 32.5, p < 0.001). ORs indicated that males were 1.45 times less likely (95% CI: 1.35–1.76) to leave for personal/social reasons than females.

Moreover, a significant association was observed between Emiratis and non-Emiratis LAMA with LAMA for personal/social reasons (χ2 [1] = 358.9, p < 0.001). ORs showed Emiratis were 3.8 times more likely (95% CI: 3.45–4.69) to leave for these reasons than non-Emiratis. LAMA's association with patient nationality in terms of leaving for financial reasons was examined. A significant association emerged between Emiratis and non-Emiratis (χ2 [1] = 313.4, p < 0.001). Emiratis were 0.032 times less likely (95% CI: 0.017–0.055) to leave for financial reasons than non-Emiratis.

It was also found that patients with triage 3–5 who left for financial reasons were 1.12 times more likely than those with triage 1–2 who left for the same reasons; however, this association was not significant (χ2 [1] = 0.928, p = 0.341). Additionally, no significant association was detected between triage level and LAMA for personal and social reasons (χ2 [1] = 0.065, p = 0.812).

Qualitative data

Twenty semi-structured interviews with HCPs, including 13 doctors, four nurses, and three public relations officers (PROs) (Appendix 1), were conducted across the four hospitals. Thematic analysis (TA) generated two main themes to aid in understanding EMR-generated data:

• Theme 1: Reasons behind LAMA

• Theme 2: Outcomes of LAMA

Researchers corrected grammatical errors and removed speech fillers such as “you know” and “okay” for anonymity, preserving participants' disclosed names.

Theme 1: reasons behind LAMA

This theme explores the reasons for LAMA. Most participants noted that non-Emirati patients often left because of financial constraints, especially if triaged at levels 3–5, requiring payment for their medical services. For these patients, LAMA primarily arises from financial challenges or a lack of insurance coverage. Thus, they sought healthcare at alternative hospitals that accommodated their financial limitations or that accepted their insurance.

“Approximately more than 90% of these patients, non-Emirati, leave because they say, ‘We do not have money to pay.' Some patients mention that they don't have insurance coverage in this hospital.”—Dr-01-MSQ stated.

Moreover, non-Emirati patients often choose to continue treatment in their home countries. This was driven by familial support and lower treatment costs in their home countries.

“[The patient went] to her country, [which costs her] less money than in the UAE.”—Ns-05-MSQ

Emirati patients often preferred other facilities, public or private. This stemmed from greater trust in other healthcare facilities and the proximity of other hospitals to their homes. Delays in seeing non-urgent patients and test results have led to more LAMA cases.

“For locals [i.e., Emiratis], it is that maybe they do not like the treatment here; they want to be treated in another hospital.”—Dr-09-MFH

Theme 2: outcomes of LAMA

The participants universally confirmed that LAMA adversely affected the patients, HCPs, and resources. This theme includes two subthemes: patient-related outcomes and outcomes affecting HCPs.

Outcomes affecting patients

The participants noted LAMA's impact on patient deterioration and increased mortality rates. LAMA patients often revisit the facility, thus increasing resource utilization. Hwang et al. (5) found that patients with LAMAs were more likely to be readmitted to hospitals within 15 days. Conversely, two participants cited instances in which patients did not return post-LAMA.

“I cannot forget one case. [In] one case, he was diagnosed with STEMI [ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction], an old [patient], he said: ‘no, I do not [want to] stay in the hospital'—Emirati also—[he had] no problem with finances, nothing, but he [did not] want to stay in the hospital…Imagine this patient came the next day, arrested (i.e., dead). I was crying also with the family.”—Dr-14-MKH

Outcome affecting HCPs

LAMA not only affects patients but also deeply impacts HCPs' mental wellbeing. Participants described emotional distress, ranging from sadness and sympathy to tears, with a strong desire to prevent patients from leaving, often leading to self-blame and preoccupation.

“[We] will continue thinking about him. [We] want to contact him to make sure that he is still in good condition, at least to feel mentally relaxed.”—Dr-07-MSQ

Some HCPs felt distressed, whereas others saw such incidents as routine. Some participants managed to detach their emotions from their work.

Discussion

This study utilized a mixed methods design to explore retrospective LAMA data and HCPs' perceptions in four EHS hospitals. It compared EMRs-documented reasons with HCP perceptions. Patient demographics aligned with those of previous studies (2, 4, 6), with most being male (61.3%) and averaging 35.1 years of age. Figure 1 shows the LAMA percentages across the hospitals. Contrary to predictions, Emirati patients unexpectedly had LAMA 2.7 times more than non-Emiratis patients. This study confirms nationality's LAMA association with the triage classification, albeit not as anticipated, possibly because Emirati patients have better access to alternative facilities, as revealed by the interviews. Furthermore, patients from other nationalities may be more accepting of the EHS health system, considering its continuous effort to improve the quality of its services and attain international accreditation.

The study revealed that males were 1.45 times less likely than females to leave for personal or social reasons, which was attributed to females seeking more family support. Additionally, female patients were more likely to leave the hospital because of family obligations. This contrasts with previous studies associating LAMA with sex (10). Naderi et al. (10) reported females leave more often for financial reasons. Despite the interview suggestions of non-Emirati patients leaving for financial reasons, the quantitative data did not support this link to the triage classification.

Patient-related factors influence LAMA decisions; however, HCPs, especially emergency personnel, may face communication challenges when addressing LAMA requests due to high workloads and staffing shortages. Additionally, the burden of LAMA significantly affects Emergency HCPs, affecting patient morbidity and mortality rates. These patients account for 1 in 50 hospital discharges (11). Emergency HCPs may lack the necessary knowledge and skills to effectively manage LAMA cases in high-stress environments, such as emergency departments. LAMA patients can be a source of frustration and distress for doctors who may take the refusal personally and feel powerless or guilty regarding patient care (12).

The second part of this study examined HCPs' perceptions of LAMA and revealed its impact on patients, HCPs, and resources. Participants noted that LAMA patients often revisited the facility with the same complaints, which is consistent with the findings of Hwang et al. (5), who showed increased readmission within 15 days. The study also revealed a prevalent sentiment of sadness and concern among HCPs when dealing with LAMA patients, given the potential for health deterioration. Based on the interviews, the study recommends effective communication with patients who express a desire for LAMA. Most participants agreed on the strategic approach that involved convincing the patient and their family through effective communication and detailed explanations of their medical condition. Previous studies emphasized the importance of effective communication (13).

To reduce the LAMA rate, we suggest ongoing training that specifically targets LAMA management is recommended (14). EHS hospitals should establish a standardized LAMA discharge protocol to ensure patient safety. The protocol should incorporate assessing the patient's ability to make such a decision. Also, follow-up assessment is essential. Although locating patients after they decide to LAMA is challenging, HCPs should seek permission to follow up with patients by phone. Good communication with other healthcare team members is not just important; it's essential when a patient leaves AMA, fostering collaboration and ensuring a comprehensive approach to patient care. EHS has 17 hospitals distributed across the UAE. Therefore, EHS should consider expanding its insurance collaborations to include flexible health insurance options for visitors and non-Emirati patients in its facilities.

This study has several limitations despite its valuable insights. The primary limitation is its reliance on data from only four out of the 17 hospitals in the EHS, which was due to limited resources for arranging interviews. Additionally, the analysis needed to account for variations in the scope of services provided by different hospitals. However, the study focused on LAMA at the EHS level, given the similarities in policies and procedures across EHS hospitals. Another significant area for improvement is the study's dependence on the perspectives of healthcare professionals (HCPs) rather than direct feedback from patients. While HCPs interact closely with patients, their understanding of patients' motivations may be limited or shaped by their professional viewpoints. Therefore, future studies should prioritize direct interviews or surveys with patients following LAMA events. This approach could provide more accurate insights into patients' reasoning and offer additional details regarding the “Others” category in their responses, helping to reduce potential biases.

In conclusion, the present study aimed to investigate the common reasons for leaving against medical advice (LAMA) at Emirates Health Services (EHS) by comparing electronic medical records (EMR) with healthcare professionals' (HCPs) stated reasons and understanding the challenges faced by HCPs in such cases. The most prominent finding from this study is that younger age, female gender, triage category, and Emirati patients were associated with LAMA in EHS facilities. Prospective primary data collection studies are needed to understand better why patients leave EHS hospitals against medical advice and the clinical implications of this decision.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical guidelines provided by the UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention (MOHAP/DXP-REC/MMM/No. 56/2023).

Author contributions

AIA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AAb: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AI: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AAl: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. EA: Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. NA: Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Alfandre DJ. “I'm going home”: discharges against medical advice. Mayo Clinic Proc. (2009) 84:255–60. doi: 10.4065/84.3.255

2. Albayati A, Douedi S, Alshami A, Hossain MA, Sen S, Buccellato V, et al. Why do patients leave against medical advice? Reasons, consequences, prevention, and interventions. Healthcare. (2021) 9:111. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9020111

3. Alfandre D. Improving quality in against medical advice discharges—more empirical evidence, enhanced professional education, and directed systems changes. J Hosp Med. (2017) 12:59–60. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2678

4. Pant MN, Jha SK, Shrestha S. Cases of left against medical advice from the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in kathmandu: a descriptive cross-sectional study. J Nepal Med Assoc. (2020) 58:992–7. doi: 10.31729/jnma.5411

5. Hwang SW Li J, Gupta R, Chien V, Martin RE. What happens to patients who leave hospital against medical advice? Can Med Assoc J (CMAJ). (2003) 168:417–20.

6. Lee CA, Cho JP, Choi SC, Kim HH, Park JO. Patients who leave the emergency department against medical advice. Clini Experim Emerg Med. (2016) 3:88–94. doi: 10.15441/ceem.15.015

7. Choi M, Kim H, Qian H, Palepu A. Readmission rates of patients discharged against medical advice: a matched cohort study. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e24459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024459

8. Braun V, Clarke V. Successful Qualitative Research: a Practical Guide for Beginners. In: Braun V, Clarke V, editor. Los Angeles: Los Angeles: SAGE. (2013).

9. Farmer T, Robinson K, Elliott SJ, Eyles J. Developing and implementing a triangulation protocol for qualitative health research. Qual Health Res. (2006) 16:377–94. doi: 10.1177/1049732305285708

10. Naderi S, Acerra JR, Bailey K, Mukherji P, Taraphdar T, Mukherjee T, et al. Patients in a private hospital in India leave the emergency department against medical advice for financial reasons. Int J Emerg Med. (2014) 7:13. doi: 10.1186/1865-1380-7-13

11. Edwards J, Markert R, Bricker D. Discharge against medical advice: how often do we intervene? J Hosp Med. (2013) 8:574–7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2087

12. Spooner KK, Salemi JL, Salihu HM, Zoorob RJ. Discharge against medical advice in the United States, 2002-2011. Mayo Clinic proceedings. (2017) 92:525–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.12.022

13. Trépanier G, Laguë G, Dorimain MV. A step-by-step approach to patients leaving against medical advice (AMA) in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med. (2023) 25:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s43678-022-00385-y

14. Pasay-An E, Mostoles R, Villareal S, Saguban R. Factors contributing to leaving against medical advice (LAMA): a consideration of the patients' perspective. Healthcare. (2023) 11:506. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11040506

Appendix

Keywords: leave against medical advice, emergency care, personal reasons, mixed methods, financial reasons

Citation: Alshamsi AI, Abuquta A, Ibrahim A, AlSaadi A, Altaee E and AlAli N (2024) Leaving against medical advice: a mixed method study to explore the prevalence, causes, and challenges in the emirates health services' hospitals. Front. Disaster Emerg. Med. 2:1474687. doi: 10.3389/femer.2024.1474687

Received: 02 August 2024; Accepted: 04 November 2024;

Published: 28 November 2024.

Edited by:

Theodore Chan, University of California, San Diego, United StatesReviewed by:

Tamorish Kole, University of South Wales, United KingdomOzgur Karcioglu, University of Health Sciences, Türkiye

Copyright © 2024 Alshamsi, Abuquta, Ibrahim, AlSaadi, Altaee and AlAli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amna I. Alshamsi, YW1uYS5hbG5hYm91ZGFoMUBlaHMuZ292LmFl

Amna I. Alshamsi

Amna I. Alshamsi Alaa Abuquta

Alaa Abuquta Alaedin Ibrahim

Alaedin Ibrahim Amna AlSaadi

Amna AlSaadi Esam Altaee

Esam Altaee