94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

Front. Digit. Humanit., 14 September 2018

Sec. Cultural Heritage Digitization

Volume 5 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fdigh.2018.00021

It is well-known that the Decadent movement in European literature (fin de siècle) depends on the narrative of the antiquity, as it is revealed from the discoveries of archeology in the second half of the nineteenth century. Amid the ruins of the past authors, painters and poets re-conceptualize time and history through a modernist vision based on an imaginary reconfiguration of the antiquity. In this context, the myth of a city (Pompeii) or of a woman (Salomé) offer examples that would illustrate in a great variety the synergy of a multi-temporal and multi-cultural memory of the myth. In this paper we identify a “content-based” shortcoming of modern Mixed Reality (MR) intangible and tangible digital heritage storytelling applications for digital humanities. It is an important problem as the very nature of these applications has often been identified with either misguided storytelling, or non-compelling, non-engaging narratives, except the initial captivating moments due to the immersive 3D visual simulation. We propose a new concept that forthcoming MR applications can draw from: “Literature-based MR Presence.” Based on modern literature excerpts associated with the real heritage sites, digital narratives can achieve new depths of Presence (phenomenon of behaving and feeling, as if we are in the virtual/augmented world created by computerized displays). They would evoke deeper sensations if their dramaturgical plots were based on literary texts associated with the heritage sites, from users, as similar to those often associated with cognitive presence, e.g., when someone is feeling of being transported in an alternate reality when simply reading a compelling novel or poem. We examine modern MR simulations and serious games for digital heritage and propose this conceptual framework to study them under this new concept, in order to achieve heightened feeling of Presence in the virtual heritage simulations, based on recent novel h/w advances. Two cases of a tangible historical place (Pompeii) and an intangible character (Salome) are identified as cultural heritage items, with associated reconstruction examples via Mixed Reality simulations and corresponding early modern literary works.

To the modern mind, myth is a word with -sometimes- contradictory meanings and connotations. According to Mircea Eliade, myth is a “sacred narrative” that teaches us the profoundest knowledge of a non-historical Past and rises to the level of an archetype (Eliade, 1959). However, not all myths are sacred; and not all sacred stories are committed to writing. On the other hand, Levi-Strauss definition focuses on the primary function of the language “on an especial high level,” a “métalangage,” so he considers the myth as a distortion from the trivial language routine to the elusive nature of poetry (Levi-Strauss, 1963). For Roland Barthes, myth is a feature of everyday life and is not restricted to grand narratives. Barthes highlights that myth is simply a “type of speech” demonstrated in our dealings with ordinary things (magazine covers, domestic appliances, sports; Barthes, 1957).

It is obvious that defining myth through different times is proven difficult because the word can legitimately refer to so many things. It can often (but not always) be a sacred story; it can be a narrative that deals in the metaphoric rather than the literal or scientific truth, sometimes with or without an artistic merit. However, what is common in all these definitions is that the myth dramatizes a vision of the nature of reality and that this kind of somehow metaphysical vision affects and impacts the global tribe's cultural memory.

Considering this somehow imprecise terminology of the myth, our working hypothesis here is to show that the myth and especially the literary myth as a depiction of cultural beliefs, values or rituals, or as a culturally significant work of the creative imagination, affects the collective cultural identity and therefore it should be integrated in the modern MR digital narratives as a dynamic reference to the Past. In order to show this, we will refer to two well-known literature myths highly popular in the nineteenth century: the example of a historical city, Pompeii (tangible cultural heritage) and the example of an insignificant and most likely ahistorical person, Salome (intangible heritage). These two rather familiar stories, the story of the cataclysmic eruption of Mount Vesuvius and the narrative of Salome's dance are related by their repetitious, quasi-ceremonial reference to a virtual representation of reality. In what sense, does this ideological romantic vision differ from the modern virtual environments and simulated worlds and in what extent does their concept of reality coincide? As Richard Coyne has shown “romanticism promotes the importance of feeling and the imagination,” which becomes a basic requirement, in order to captivate notions of a lost world through ruins and debris of material culture. The long descriptions as a technique in the narratives of the nineteenth century novels and the rich illustrations of the books prove the desire of the public not only to fantasize the antiquity, but also participate in a way in its mysterious world. By suggesting parallels between the literary genre of the nineteenth century novel and the contemporary digital narrative we do not try to define a genre but rather describe a mode with criteria pertaining genre. In that sense, as the literary novels in the nineteenth century become popular and affordable, especially from the middle nineteenth century and on, they represent the only mode of an educating amusement or edutainment (or informal, gamified, playful learning), which also covers both needs of the horatian definition of Ars Poetica as dulce e utile (both enjoyable and instructive) by offering knowledge, information on other cultures, civilizations or travels, certainly not in an interactive way, as in digital culture, but surely in a way which is based on imagination skills and possibilities. In this paper we provide a conceptual framework of what we call “literature-based MR Presence” and illustrate that when literary myths, which operate as a depiction of cultural beliefs, are integrated with MR reconstructions and serious games for digital heritage, could instill higher cognitive presence to the end users. To meet this goal, we study a series of different previous, existing MR applications, which have, or have not been based on literary myths, and we leave as future work the adoption of this framework for new, forthcoming MR case studies.

In the first part of this work we present a brief overview of modern MR technologies and Interactive Learning Events (ILEs) employed in digital heritage, since they constitute the computer science part of our proposed framework. In the first section of the second part we present the literary myth of Pompeii trying to understand how the obsession with ruins evokes the obsession with images, whereas in the second section we compare the literary discourse with the principle of recent MR reconstructions. In the first section of the third part we focus on a historical persona, who inspired painting as well as poetry and prose, whereas in second section we study the influence of the myth in an inventive, contemporary language, which translates poetry in digital terms as an example of a new shape of knowledge. We summarize with Conclusions and Future work, regarding next step implementations based on the conceptual framework of “Literature-based MR Presence” that we presented and analyzed in this paper.

Mixed Reality (MR; Milgram and Kishino, 1994; Coyne, 1999) has been depicted as a continuum that includes both Virtual Reality (VR), as well as Augmented Reality (AR; Azuma et al., 2001). Mixed Reality interactive applications are unique for digital heritage (Papagiannakis et al., 2005; Papagiannakis and Magnenat-Thalmann, 2007; White et al., 2007; Sylaiou et al., 2009; Engberg, 2017), as they are able to elude one's cognitive system and produce sense of being physically present in the real, as well as the virtual world. This “sense of being there” (Papagiannakis et al., 2015) is also known as Presence (Slater, 2014). Presence is considered as a paramount factor when someone interacts with MR environments, especially considering educational or digital heritage settings (Foni et al., 2010), since it gives an indication of whereas the virtual scenario has the ability to drain the subject into it. In this way, the level of Presence is fundamental to understanding the extension of which the subject perceives the scenario as a real world experience, even though the origin and nature of this variable are still not clear. Mixed Reality (AR and VR) Presence enabling technologies (Thomas, 2012; Kapp et al., 2013; Slater, 2014; Papagiannakis et al., 2015, 2018) have only recently started being investigated in Serious Games applications (Kateros et al., 2015) for digital heritage (Egges et al., 2007; Kapp et al., 2013; Abrash, 2014) in terms of entertainment (Markouzis and Fessakis, 2015), education: cognition and knowledge transfer (Capuano et al., 2016), as well as learning (Pollalis et al., 2018), gamification (Papagiannakis et al., 2015; Zikas et al., 2016), engagement (Di Pietro et al., 2017), emotions (Harley et al., 2016), and enjoyment (Sylaiou et al., 2010, Brancati et al., 2015).

Digital Games for Empowerment and Inclusion (DGEI; Sanchez-Vives and Slater, 2005), as well as Interactive Learning Events (ILEs): Serious games and gamification (Anderson et al., 2009) have already been successfully researched in variable paths in EU innovation projects, as well as worldwide, including applications in digital heritage and virtual museums. The vast majority of these projects have been led by renowned academics, or industrial partners specialized in MR technology and related gamified products. The mainstream European digital gaming industry has been so far not involved in these endeavors, i.e., use of digital gaming technologies in digital heritage, hence resulting in minimal uptake and adoption (Sanchez-Vives and Slater, 2005). Furthermore, many of these products rely on expensive interactive boards, or desktop PCs and not harnessing the mobile devices that the majority of Europeans now utilize in everyday life. On top of that, in the works there is currently an imminent total transformation of this very same digital gaming industry according to a broad analysis from several sources (Centeno, 2013): the advent of recent low-cost, high-quality VR Head Mounted Displays (Samsung Gear, Oculus Rift, Sony Morpheus, Zeiss VROne), AR-glasses (Microsoft Hololens, Metaview Spaceglasses, Atheer-one etc.). These new h/w advances bring ourselves at a major tipping point: the core notion of Presence research (“the feeling of being and doing there”) in an immersive environment of the Mixed Reality continuum (that includes Virtual and Augmented Reality: VR & AR) is dramatically momentarily enhanced and thus destined to transform the core nature of digital heritage applications, including games and ILEs. Exactly this innovation wave we believe that needs to be combined with literature, for sustained, prolonged original and captivating interactive experiences using “literature-based MR Presence.” After all, literature was the original Virtual Reality (Cavafy, 2012).

Mount Vesuvius erupted on August 24, A.D. 79, burying Pompeii and neighboring towns under tons of ash and volcanic debris. Rediscovered by accident some 1,650 years later, the Vesuvian ruins captured the imagination of artists and writers, who saw in the catastrophe the image of their “ruined and ruinous world” (Macaulay, 1953). It is well-known that the ≪ruin lust≫ that gripped European art and literature at the end of the eighteenth century imposed a cult of melancholy and a whole esthetic of romantic evocation of Time that could eventually explain the fatal attraction for the most famously dead of all ancient cities (Ginsberg, 2004).

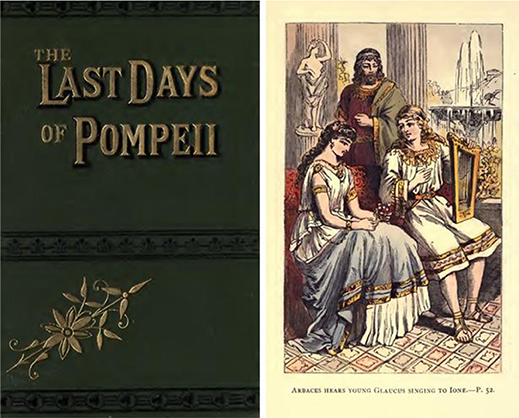

Seemingly frozen in time and although already saturated as a subject in terms of literary history or history of art, Pompeii becomes a real obsession after the huge success in 1834 of Edward Bulwer-Lytton's Victorian novel The Last Days of Pompeii (Bulwer-Lytton, 1873; Figure 1 below). This romantic melodrama, one of the most popular literary works of the nineteenth century has a dramatic impact on the modern perception of the city and will impose for decades a very precise, moralistic vision of the Pompeian life, set immediately and tragically before the eruption.

Figure 1. The Last Days of Pompeii1 (Socken, 2013), reproduced with the permission of the copyright holder (Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 3006-911).

In brief, the novel follows two interlocking love triangles. At the center is the romance of two well-born Greeks, Glaucus and Ione, who must escape the grips of an evil Egyptian priest. There is also Nydia, the most complex character a Thessalian slave who pines hopelessly for Glaucus and commits suicide at the end. Combining historical fact with Romance, the author tries to provide to the reader the illusion of a hyper-realistic, empirical experience of the ancient life, as he explains in his preface:

“From the ample materials before me, my endeavor has been to select those which would be most attractive to a modern reader: the customs and superstitions least unfamiliar to him, — the shadows that, when reanimated, would present to him such images as, while they represented the Past, might be least uninteresting to the speculations of the present” (Bulwer-Lytton, 1873).

Bulwer's consent to appropriate history in order to reproduce a near photographic picture of the antiquity shows an insecure author who asks his audience for an empirical validation, an author who insists dramatically on the fiction being fact. What is really interesting in this confession, other than his granted Victorian preoccupation with realism, is the way the author understands the term of representation being reality: “reanimate the shadows” means illustrate the historical fact through a romance with moral purpose (Foni et al., 2010). And it is definitely not a coincidence that the book inspired by a visit to the eerily well-preserved ruins of Pompeii, belongs to those novels which gained their commercial success not only as an autonomous work of literature to be read but also as a set of visual images to be seen, the first on such type of historical novels.

As Annika Bautz points out “the Last Days was most read, or at any rate most sold as a book the second half of the nineteenth century, the golden age of artistic illustrations” (St Clair and Bautz, 2012). In that sense, it is striking how the myths of Pompeii were constructed, selected, disseminated and reinforced not in the form of a literary plot but mainly in the form of pictures.

Reconstructing the Past out of its material fragments, be they stones and broken pots or fragments of memories shows an impressive affinity between the structure and the representational schemes of digital narratives. Because Pompeii has been proposed as the origin point of the digital culture and through the myriad digital reconstructions of it, it would be useful to understand the contemporary perception of the Past, in comparison with literature narratives, which also depend drastically on a visual language (Gardner Coates et al., 2012).

It is impossible to imagine Pompeii without its erupting volcano and this distortion of the memory feeds every single narrative of the city life back then. So it would not be precarious to compare the romantic mythic narrative in the Last Days with a 4D computer animation or with the computer adventure game “Time escape: Journey to Pompeii”2 (Figures 2–4).

Figure 2. “A day in Pompeii” I,3 reproduced with the permission of the copyright holder (Zero One Studio).

Figure 3. “A day in Pompeii” II,4 reproduced with the permission of the copyright holder (Zero One Studio).

Figure 4. “A day in Pompeii” III,4 reproduced with the permission of the copyright holder (Zero One Studio).

The kinetic image of the catastrophe rhymed by frightening pauses underlined with the silence and the deep dark screen transports the virtual visitor to a complete sensory experience.

This tactile notion of the vision creates an access to reality, where language seems absent or reduced to a vague noise.

Hence the gaze is oriented to one direction and the disaster narrative obeys to one dimension: the symbolic of the power of nature is subordinated to the panopticon of the human despair, since the empty space of the city only evokes but not highlights the human presence.

On the contrary, in Bulwer's Last Days of Pompeii survives glamorously through the apocalyptic, operatic spectacle but also through the array of individual characters in a romance that unfolds in time.

“Another—and another—and another shower of ashes, far more profuse than before, scattered fresh desolation along the streets. Darkness once more wrapped them as a veil; and Glaucus, his bold heart at last quelled and despairing, sank beneath the cover of an arch, and, clasping Ione to his heart—a bride on that couch of ruin—resigned himself to die” (Bulwer-Lytton, 1873).

Almost the same narrative canvas will be used in the scenario of the computer game “Time escape: Journey to, Pompeii”.6 Timescape was originally published in Europe by Cryo Interactive.

You play as Adrian Blake, presumably an archeologist “on a mission for the crown” at the end of World War I. While exploring a cave, Adrian is approached by the goddess Ishtar, who offers to cure him in exchange for his love. Adrian refuses, so Ishtar decides to punish him for not believing in “love incarnate.” Consequently, his beloved has been sent back in time to Pompeii and Adrian has to convince her to leave the city, before the eruption occurs. All the elements of the narrative coexist in a rather simple structure, whose main character acts in a multiple, imaginative historical environment, where the artificial dialog sequences detract from any sense of immersion. Above all, the first person perspective excludes the multiplicity that the Virtual Reality claims to restore.

The same first person perspective we can meet in another famous nineteenth century novel: Théophile Gautier's “Arria Marcella” (Gautier, 1852). Here the protagonist Octavian is mesmerized when visiting the museum by the sight of a molded contour of a breast preserved by the catastrophe, and he is transported by his passion back two millenniums. The magical resurrection of Arria Marcella reflects the Romanticism's obsession with archeology and the imaginative reconstruction of the Past: through the return to the pagan antiquity, the young hero discovers not only the ancient landscape, but also the most primitive region of his own being, his deeply instinctual nature. As Gautier and Arria used to say:

“Indeed nothing dies, but all exists perpetually, that which was once, no power can annihilate. Every act, every word, every shape, every thought, which has fallen into the universal ocean of being forms widening circles that go on expanding to the far reaches of eternity… Passionate minds, powerful wills, have succeeded in summoning forth ostensibly vanished centuries and in resurrecting human beings from the dead” (Gautier, 1852).

Though, if “Arria Marcella” is more classified as a fantastic novel in the history of literature and less as a “Souvenir de Pompeii,” this very special mythic canvas of archeology, delusion and dream is used in another popular novel: Jenssen's famous Gradiva (Jenssen, 1918). The young archeologist Norbert Hanold, discovers at Rome, in a collection of antiques, a bas-relief which attracts him so exceptionally that it absorbs all his attention and gradually haunts him to the point that through a terribly frightful dream he is made eye witness of the destruction of the city.

“The heavens held the doomed city wrapped in a black mantle of smoke only here and there the flaring masses of flame from the crater made distinguishable something steeped in blood red light. […] As he stood thus at the edge of the Forum near the Jupiter temple, he suddenly saw Gradiva a short distance in front of him. Until then no thought of her presence there had moved him, but now suddenly, it seemed natural to him, as she was, of course, a Pompeian girl that she was living in her native city and, without his having any suspicion of it, was his contemporary” (Jenssen, 1918).

Exposed to this extrasensory experience being between Past and present Norbert discovers through this delusional dream an intimate reality in terms of “repression,” as Freud will explain later (Freud, 1995). We could then imagine that Pompeii surveys as “heterotopia,” which functions as a placeless place, a reflection of the being.

“Places of this kind are outside of all places even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality. Because these places are absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about, we shall call them, by way of contrast to utopias, heterotopias. we believe that between utopias and these quite other sites, these heterotopias, there might be a sort for mixed joint experience, which would be the mirror. The mirror is, after all, a utopia, since it is a placeless place. In the mirror, I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind own visibility to myself, that enables me to see myself there where I am absent: such is the utopia of the mirror. But it is also a heterotopia in so far as the mirror does exist in reality, where it exerts a sort of counteraction on the position that I occupy” (Foucault, 1984).7

If we transfer in the Information Technology this “mixed joint experience” that Foucault describes here, we should perhaps examine Virtual and Augmented Reality (AR) as a pattern of a new post-modern sensibility. Virtual and Augmented Reality (AR) and their concept of cyber-real space invoke such interactive digital narratives that promote new patterns of understanding. The word “narrative” refers to a set of events happening during a certain period of time and providing esthetic, dramaturgical and emotional elements, objects and attitudes. Mixing such esthetic ambiences with virtual augmentations and adding dramatic tension, can develop these narrative patterns into an exciting new edutainment medium (Foucault, 1984; Azuma et al., 2001). By employing “literature-based MR Presence” i.e., basing the dramatic storytelling on literary texts, would develop even further these narratives and prolong Presence for the end users.

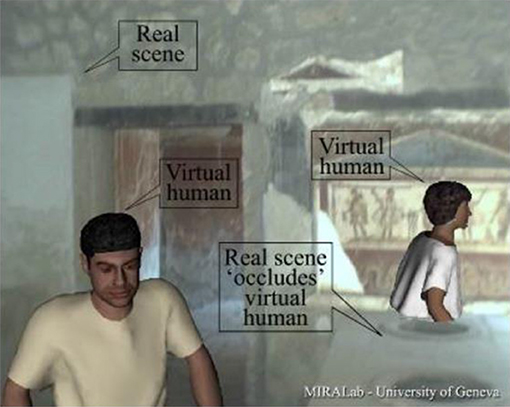

The abandonment of traditional concepts of static cultural artifacts with interactive, augmented historical character-based event representation based on literature is an important component of this redefinition. For such digital narratives realized with Mixed Realities (Virtual and Augmented Reality), the conditioned notion of artifact gives away to a far more liberated notion. As suspended in MR space, the visitor leaves the prison of petrified cultural heritage and emerges in a contextualized world of informative intangible sensation. In such a world, “the dream of perfect FORMS becomes the dream of information”8 (Tamura et al., 2001; Papagiannakis et al., 2005), as depicted in the LIFEPLUS project (Figure 5).

Figure 5. LIFEPLUS project [19], reproduced with the permission of the copyright holder (LIFEPLUS project).

Hence, the core notion of the conceptual “literature-based MR presence” framework is the following: Without the original experience of writing, or the authenticity of text, basically without the notion of literature, the dream of hybrid information proves a mere technological achievement8, a condensed fantasy of imagination and material reality, which however doesn't really lead the imaginary into a sharp and clear form of Presence in the reconstructed MR of the digital heritage site.

If we examined Pompeii as a “placeless place” that could combine the literary and the digital myth, we would like now to extend our conceptual framework using as example another nineteenth century myth, this time not about a place but about a historical person: Herodias's daughter, Salome, as an example of intangible heritage. “Major Myth of the collective unconscious” (Papagiannakis and Magnenat-Thalmann, 2007) Salome's story, insignificant historical incident, which leads however to a fundamental murder, John the Baptist's death, nourishes the literary imagination for centuries with obsessive fantasies of an eternally guilty femininity. Almost non-existent in biblical texts -Matthew or Mark's Evangelic texts in the parsimony of the story open all possible interpretations- Salome undergoes such a mythical crystallization that it becomes one of the great archetypes of the femme fatale, who mutilates and disinherits (Bochet, 2007).

Unlike Pompeii, in Salome's case we deal with a myth without a tangible historical trace. The daughter of Herodias and Herod's niece is not named Salome in the two biblical accounts. As a matter of fact, she does not have a name. It wasn't until Flavius Josephus wrote his Jewish Antiquities, that the beautiful stepdaughter of Herod was named Salome (Girard, 1984). Unlike Pompeii whose historical reality becomes and survives as a post-modern myth, Salome floats between the vague boundaries of a mythic presence, which becomes historical reality.

However, Salome's popular story makes an excellent subject matter in artwork and hundreds of revisions of Salome appear in literature. Oscar Wilde wrote his one-act play Salomé, originally written in French, to shock audiences with its spectacle of perverse passions (Flavius, 1906). Wilde's play became the source and inspiration for Richard Strauss's one-act opera also named Salomé, first produced in 1905 and from that point a real obsession for the dancer captures the whole Europe. In the same time, Salome becomes a cult figure through the drawings of Beardsley, which bring out powerfully the secret of unspeakable eroticism of the play (Wilde, 1893).

One of the ways to undertake a deconstructive reading of a text is to understand its assumptions through a study of its intertextual repetitions. Inspired by Oscar Wilde's Salome and a French poem written for the occasion of the performance in Paris by Jules Boissières, the Greek poet C. P. Cavafy writes in Alexandria, Egypt his version distorting the initial myth toward a new cast of persons (Salome vs. Sophist; Zagona, 1960):

“Upon a golden charger Salome bears the head of John the Baptist to the young Greek sophist who recoils from her love, indifferent.

The young man quips, “Salome, your own head is what I wanted them to bring me.” This is what he says jokingly.

And her slave came running on the morrow holding aloft the head of the Beloved, its tresses blond, upon a golden plate.

But all his eagerness of yesterday the Sophist has forgotten as he studied. He sees the dripping blood and is disgusted.

He orders this bloody thing to be taken from him, and he continues his reading of the Dialogues of Plato”.9

Last year, Cavafy's Salome danced to Tokyo in the frame of an animated student project inspired by the Cavafy's poetry organized by the Art/European Animation Center and the Musashino Art University, Tokyo (Vassiliadi, 2008), illustrated in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6. Salome made in Japan (Vassiliadi, 2008), reproduced with the permission of the copyright holder (Sae Matsumura, Musashino Art University, Dino Sato, 2013, Art/European Animation Center).

In this light, focusing on Salome's myth, whose afterlife depends also on the field of a constantly multiple representation, our current aim is to include digital interpretation to the various versions of the myth, in order to emphasize also to the symbolic reality behind the narrative.

In this paper we have analyzed the theoretical discourse of a new concept of “Literature-based MR Presence” for digital humanities and MR digital heritage applications. We presented examples of the first modern novel of the nineteenth century that, in order to depict a historical catastrophe in a digital heritage site (Pompeii, tangible heritage), included images as part of its transcript. We also present examples of another historical figure (Salome, intangible heritage), who also has extensively being identified in modern literature, as well as digital narratives. As we were among the first in the bibliography to create MR narratives in real sites (Pompeii; Foucault, 1984; Papagiannakis et al., 2005) using modern computer graphics techniques, we aim to implement “Literature-based MR Presence” in our ongoing MR research in forthcoming digital heritage reconstructions.

Such is the contradictory working of myths. And as the quintessential reductive machine, the computer is employed as the device that will restore its unity through multiplicity and fragmentation. Hence, we need to consider this work as a further step toward reconciliation and a renewed mutual beneficial relationship between humanities and computer science.

MV provided all the literary research and how literary myths can be employed as input to MR simulations. GP provided all the MR related research and Presence. SS provided the connection between literary excerpts and storytelling in MR.

The research leading to these results was partially funded by the Virtual Multimodal Museum (ViMM-727107), a Coordination and Support Action (CSA), funded under the EU Horizon 2020 programme (CULT-COOP-8-2016).The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n°608013 ITN-DCH—Initial Training Networks for Digital Cultural Heritage: Projecting our Past to the Future.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. ^Cover and illustration from the copy of Bulwer-Lytton's The Last Days of Pompeii in the special collections of the Getty Research Institute (London, William Nicholson, ca. 1883), Available at: http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/apocalypse-then-bulwer-lyttons-the-last-days-of-pompeii/

2. ^A Day in Pompeii, Full Length Animation, Zero One. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dY_3ggKg0Bc&t=62s

3. ^A Day in Pompeii, Full Length Animation, Zero One. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dY_3ggKg0Bc&t=62s

4. ^A Day in Pompeii, Full Length Animation, Zero One. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dY_3ggKg0Bc&t=62s

5. ^A Day in Pompeii, Full Length Animation, Zero One. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dY_3ggKg0Bc&t=62s

6. ^Poole, S. Journey to Pompeii Review. Available at: http://www.Gamespot.Com/Reviews/Timescape-Journey-To-Pompeii-Review/1900-2678110/

7. ^Mirror is a heterotopia, one of the ‘other places’, since it is a real object, relates to the real space that surrounds it, and –at the same time- it is an unreal object, because it mirrors/ creates a virtual image. A MR environment for cultural heritage is also a heterotopia, it has different layers of meaning and relations, since it is a virtual place that represents reality, but at the same time it is “real” for the users that are fully involved, feel present in it and immersed to it.

8. ^C. P. Cavafy in Tokyo. Available at: https://cavafy.arteac.eu/tokyo/en/project/

9. ^Bulwer-Lytton E., Nothing changes under the sun: Authenticity in The Last Days of Pompeii. Available at: http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/bulwer/pompeii/sawhney.html

Abrash, M. (2014). What VR Could, Should and Almost Certainly Will be Within Two Years. Available online at: http://media.steampowered.com/apps/abrashblog/Abrash%20Dev%20Days%202014.pdf.

Anderson, E. F., McLoughlin, L., Liarokapis, F., Peters, C., Petridis, P., and Freitas, S. (2009). “Serious games in cultural heritage,” in 10th VAST International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (VAST'09). Available online at: https://curve.coventry.ac.uk/open/file/8a308515-08b5-ac5f-eaf9-b61adeeaf60a/1/Serious%20games%20in%20cultural%20heritage.pdf.

Azuma, R., Baillot, Y., Behringer, R., Feiner, S., Julier, S., and MacIntyre, B. (2001). Recent advances in augmented reality. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 21, 34–47. doi: 10.1109/38.963459

Barthes, R. (1957). Mythologies. Paris: Éditions Du Seuil. See also Barthes, R. (1984). Mythologies. Trans. Lavers, A. New York: Hill and Wang.

Brancati, N., Caggianese, G., De Pietro, G., Frucci, M., Gallo, L., and Neroni, P. (2015). “Usability evaluation of a wearable augmented reality system for the enjoyment of the cultural heritage,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Signal-Image Technology & Internet-Based Systems (SITIS) 2015 (Bangkok: IEEE), 768–774.

Capuano, N., Gaeta, A., Guarino, G., Miranda, S., and Tomasiello, S. (2016). Enhancing augmented reality with cognitive and knowledge perspectives: a case study in museum exhibitions. Behav. Inform. Technol. 35, 968–979 doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2016.1208774

Centeno, C. (Ed.) (2013). The Potential of Digital Games for Empowerment and Social Inclusion. JRC Scientific and Policy Reports, 1–172. Available online at: http://ftp.jrc.es/EURdoc/JRC78777.pdf.

Coyne, R. (1999). Technoromanticism: Digital Narrative, Holism, and the Romance of the Real. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Di Pietro, L., Guglielmetti Mugion, R., Arcese, G., and Mattia, G. (2017). Cultural visitors' engagement and augmented reality: an empirical investigation. Int. J. Environ. Policy Decis. Making 2, 97–103.doi: 10.1504/IJEPDM.2017.083920

Egges, A., Papagiannakis, G., and Magnenat-Thalmann, N. (2007). Presence and interaction in mixed reality environments. Vis. Comput. 23, 317–333. doi: 10.1007/s00371-007-0113-z

Eliade, M. (1959). The Myth of the Eternal Return: Or Cosmos and History. Trans. Trask, W. R. New York, NY: Harper Torchbooks and Eliade, M. (1968). Myth and Reality. New York, NY: Harper and Row. See also What is Myth. The History of the Term, Related Genres and a Working Definition. Available online at: http://saleonard.people.ysu.edu/What%20is%20Myth.html.

Engberg, M. (2017). “Augmented and mixed reality design for contested and challenging histories,” in Museums and the Web Conference 2017. Available online at: https://mw17.mwconf.org/paper/augmented-and-mixed-reality-design-for-contested-and-challenging-histories-postcolonial-approaches-to-site-specific-storytelling/.

Foni, A., Papagiannakis, G., and Magnenat-Thalmann, N. (2010). A taxonomy of visualization strategies for cultural heritage applications. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Heritage 3, 1–21. doi: 10.1145/1805961.1805962

Foucault, M. (1984). Of other spaces: utopias and heterotopias. Trans. Miskowiec, J. Diacritics 16, 22–27. Available online at: http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/foucault1.pdf

Freud, S. (1995). Le Délire Et Les Rêves Dans La Gradiva De W. Jensen [1907] (Trad. de L'allemand Par J. Bellemin-Noël, Éd. J.-B. Pontalis), Paris: Gallimard, 1986. See Also Roland Barthes, “La Gradiva,” Fragments d'un Discours Amoureux [1977], Œuvres Complètes (Éd. É. Marty), Paris: Le Seuil, T. III, P. 573–575.

Gardner Coates, V.C., Lapatin, K., and Seydl, J.L. (2012). The Last Days of Pompei. Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection. Los Angeles, CA: J. P. Getty.

Girard, R. (1984). The scandal and the dance. Salomé in The Gospel of Marc. New Lit. Hist. 15, 311–324. doi: 10.2307/468858

Harley, J. M., Poitras, E. G., Jarrell, A., Duffy, M. C., and Lajoie, S. P. (2016). Comparing virtual and location-based augmented reality mobile learning: emotions and learning outcomes. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 64, 359–388. doi: 10.1007/s11423-015-9420-7

Kapp, K.M., Blair, L., and Mesch, R. (2013). The Gamification of Learning and Instruction Fieldbook. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Kateros, S., Georgiou, S., Papaefthymiou, M., Papagiannakis, G., and Tsioumas, M. (2015). A comparison of gamified, immersive VR curation methods for enhanced presence and human-computer interaction in digital humanities. Int. J. Digital Era 4, 221–233. doi: 10.1260/2047-4970.4.2.221

Levi-Strauss, C. (1963). Structural Anthropology. New York, NY: Library of Congress. Trans. Claire Jacobson, 210–211.

Markouzis, D., and Fessakis, G. (2015). “Interactive storytelling and mobile augmented reality applications for learning and entertainment–a rapid prototyping perspective,” in Proceedings International Conference on Interactive Mobile Communication, Technologies and Learning (IMCL) 2015, Thessaloniki, Greece. 4–8.

Milgram, P., and Kishino, F. (1994). A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. IEICE Trans. Inform. Syst. 77, 1321–1329.

Papagiannakis, G., Geronikolakis, E., Pateraki, M., López-Menchero, V. M., Tsioumas, M., Sylaiou, S., et al. (2018). Mixed Reality Gamified Presence and Storytelling for Virtual Museums, Encyclopedia of Computer Graphics and Games. Cham: Springer.

Papagiannakis, G., Greasidou, E., Trahanias, P., and Tsioumas, M. (2015). Mixed-reality geometric algebra animation methods for gamified intangible heritage. Int. J. Heritage Digital Era 3, 683–699. doi: 10.1260/2047-4970.3.4.683

Papagiannakis, G., and Magnenat-Thalmann, N. (2007). Mobile augmented heritage: enabling human life in ancient pompeii. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 5, 395–415. doi: 10.1260/1478-0771.5.2.396

Papagiannakis, G., Schertenleib, S., O'Kennedy, B., Arevalo-Poizat, M., Magnenat-Thalmann, N., Stoddart, A., et al. (2005). Mixing virtual and real scenes in the site of ancient pompeii. Comput. Anim. Virtual Worlds 16, 11–24. doi: 10.1002/cav.53

Pollalis, Chr., Minor, E. J., Westendorf, L., Fahnbulleh, Wh., Virgilio, I., Kun, A. L., et al. (2018). “Evaluating learning with tangible and virtual representations of archaeological artifacts,” in Proceedings of ACM International Conference on Tangible, Embedded and Embodied Interaction (TEI) 2018, Stockholm, Sweden. Available online at: https://cs.wellesley.edu/~hcilab/publication/TEI18_holomuse.pdf.

Sanchez-Vives, M. V., and Slater, M. (2005). From presence to consciousness through virtual reality. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 332–339. doi: 10.1038/nrn1651

Slater, M. (2014). Grand challenges in virtual environments. Front. Robot. AI 1:3. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2014.00003

St Clair, W., and Bautz, A. (2012). Imperial decadence: the making of myths in Edward Bulwer-Lytton's last days in pompeii. Victorian Lit. Cult. 40, 359–396. doi: 10.1017/S1060150312000010

Sylaiou, S., Liarokapis, F., Kotsakis, K., and Patias, P. (2009). Virtual museums, a survey and some issues for consideration. J. Cult. Herit. 10, 520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.culher.2009.03.003

Sylaiou, S., Mania, K., Karoulis, A., and White, M. (2010). Presence-centred usability evaluation of a virtual museum: exploring the relationship between presence, previous user experience and enjoyment. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 68, 243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2009.11.002

Tamura, H., Yamamoto, H., and Katayama, A. (2001). Mixed reality: future dreams seen at the border between real and virtual worlds. Comput. Graph. Appl. 21, 64–70. doi: 10.1109/38.963462

Thomas, B. H. (2012). A survey of visual, mixed, and augmented reality gaming. Comput. Entertainment 10, 1–33. doi: 10.1145/2381876.2381879

White, M., Petridis, P., Liarokapis, F., and Plecinckx, D. (2007). Multimodal mixed reality interfaces for visualizing digital heritage. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 5, 322–337. doi: 10.1260/1478-0771.5.2.322

Zagona, H. G. (1960). The Legend of Salome and the Principle of Art for Art's Sake. Genève; Paris: Librairie Droz.

Keywords: digital humanities, mixed reality, comparative literature, neo-romanticism, sense of presence

Citation: Vassiliadi M, Sylaiou S and Papagiannakis G (2018) Literary Myths in Mixed Reality. Front. Digit. Humanit. 5:21. doi: 10.3389/fdigh.2018.00021

Received: 08 February 2018; Accepted: 20 August 2018;

Published: 14 September 2018.

Edited by:

Josep Lladós, Autonomous University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Ioanna N. Koukouni, Independent Researcher, Athens, GreeceCopyright © 2018 Vassiliadi, Sylaiou and Papagiannakis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: George Papagiannakis, cGFwYWdpYW5AaWNzLmZvcnRoLmdy

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.