- 1Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand

- 2Center of Data Analytics and Knowledge Synthesis for Health Care, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand

- 3Environmental and Occupational Medicine Excellence Center, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand

Introduction: Frailty is a common degenerative condition highly prevalent in adults over 65 years old. A frail person has a higher risk of morbidities and mortality when exposed to health-related stressors. However, frailty is a reversible state when it is early diagnosed. Studies have shown that frail people who participated in an exercise prescription have a greater chance to transition from frail to fit. Additionally, with a rapid advancement of technology, a vast majority of studies are supporting evidence regarding the digital health tools application on frail population in recent years.

Methods: This review comprehensively summarizes and discusses about technology application in frail persons to capture the current knowledge gaps and propose future research directions to support additional research in this field. We used PubMed to search literature (2012–2023) with pre-specified terms. Studies required older adults using digital tools for frailty comparison, association, or prediction and we excluded non-English studies and those lacking frailty comparison or digital tool use.

Results: Our review found potential etiognostic factors in trunk, gait, upper-extremity, and physical activity parameters for diagnosing frailty using digital tools in older adults.

Conclusion: Studies suggest exercise improves frailty status, emphasizing the need for integrated therapeutic platforms and personalized prevention recommendations.

Introduction

Aging society is an inevitable ongoing trend in the world. The definition, pace, and implications of aging differ significantly between developing and developed countries. In developing countries, the elderly are typically defined as those aged 60 and above, compared to 65 in developed regions, due to variations in life expectancy, socioeconomic conditions, and healthcare access (1–6). In developing regions, the elderly population is growing 1.5 times faster and faces greater challenges, including poverty, poor health, and limited social support systems (7–9). In contrast, developed countries benefit from established healthcare, welfare systems, and healthier, more active elderly populations (10). World Health Organization reported that within 2030 1 in 6 people in the world will be aged over 65 years and by 2050 number of persons aged over 60 years old is expected to reach 426 million (6, 11). This trend is common in many countries and is attributed to a combination of factors such as improved healthcare and advancements in medical technology, which have allowed people to live longer (12). The world public health is now facing the challenges and opportunities that come with an aging society since older adults are linked to increased multiple chronic diseases, comorbidities and mortality (13–15).

Frailty is a clinical condition highly prevalent in the aged population in which a frail individual is more vulnerable to health-related risk exposure (16, 17). Studies showed that this condition has been linked to increased hospitalizations, Emergency Department (ED) visits (18–21), poorer quality of life (22), impaired cognitive function (23), increased morbidity and mortality (24). Frailty is commonly defined by Fried et al. using unintentional weight loss, gait speed, exhaustion, grip strength and physical activity as a clinical diagnostic criteria (25).

There has been an increase in studies on frailty in recent years since frailty could be decreased or reversed with a long-term-based exercise intervention (26, 27). Fairhall et al. conducted an randomized controlled trial of 241 community-dwelling older adults in Australia where the findings showed that exercise and nutrition intervention could significantly improve frailty status in the treatment group (28). The result agreed with Nakamura et al. where 111 community-dwelling older people in Japan were randomly assigned to perform a home-based training during Covid-19 pandemic (29).

Several studies have employed digital tools to help diagnose and treat frailty as technology has improved and become more accessible (30, 31). We believe that information technology can help us recognize frailty earlier, and that the earlier we identify this condition, the better healthcare providers can treat the patient with a better prognosis and health outcomes. This review aims to identify and summarize prospective characteristics, diagnostic models, and therapeutic studies in utilizing digital health technologies in community-dwelling frail older persons.

Search strategy

We used PubMed as our main source of published literature for our search strategy. The combinations of search terms were (“frailty*” OR “frail” OR “frail elderly”) AND (“digital” OR “machine learning” OR “smartphone*” OR “AI” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “deep learning” OR “device*”) AND (“older adults” OR “elderly” OR “elder” OR “old”). The selected publications in our review were limited to English publications and publications within 2012–2023. Additional literature found in systemic reviews and meta-analysis were manually selected to include in this review. Inclusion Criteria: (1) The study recruited older adults aged at least over 50 years old; (2) The study applied digital health tools to find association, causal relationship or make prediction between frail and non-frail population. Exclusion Criteria: (1) The study was not written in English; the study did not demonstrate a comparison of result between frail and non-frail population; The study did not utilize digital tools.

Characteristics studies

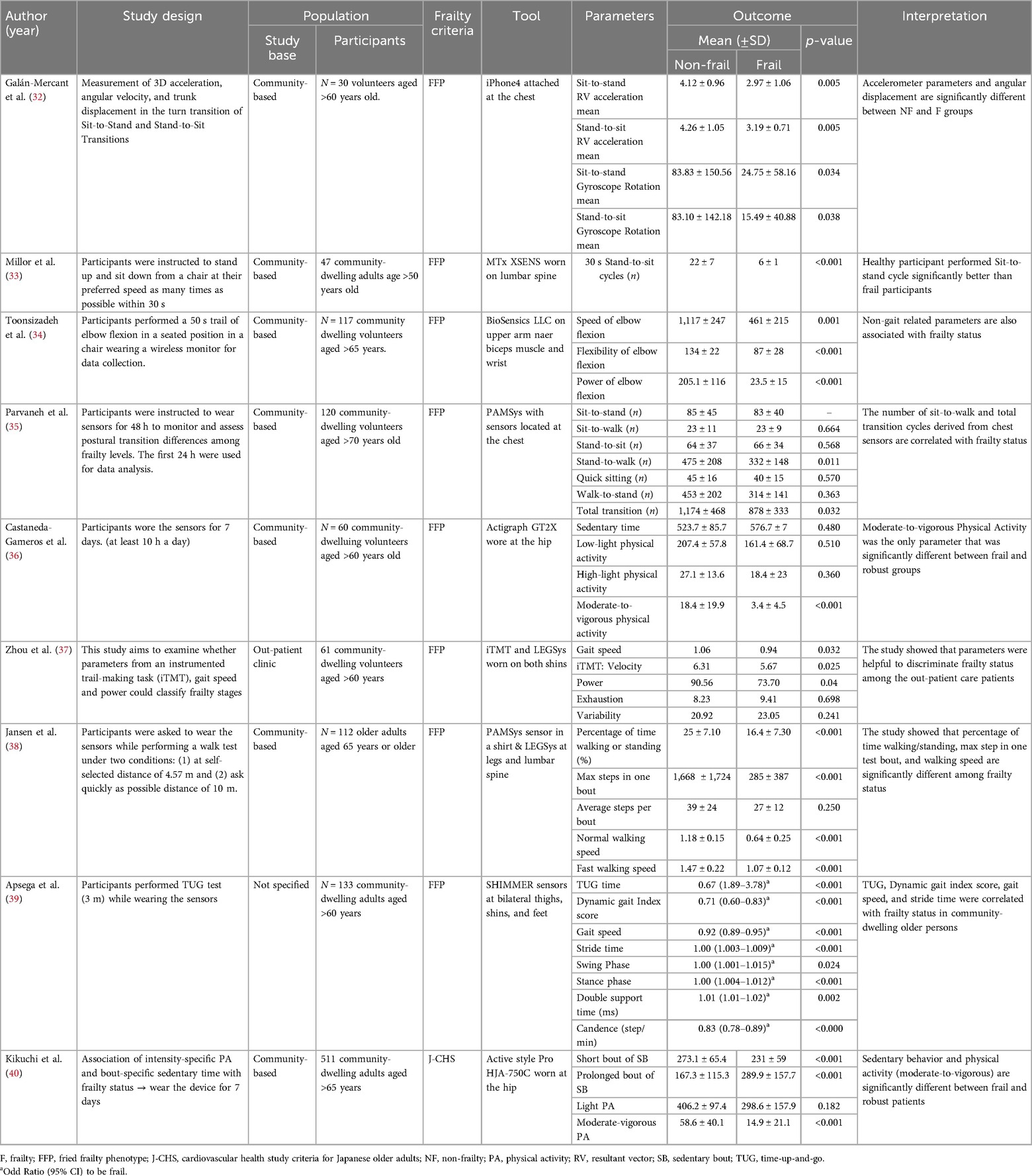

We found 9 relevant frailty characteristics studies and summarized them into Table 1. Most studies used various types of digital sensors to measure surrogate outcome of frailty and are categorized into (1) Trunk parameter (2) Gait parameter and (3) Non-gait parameters.

Trunk parameter

Most studies' methods involved researchers instructing volunteers to perform physical function tests while wearing a digital sensor that measures characteristics that likely represents frailty. Galan-Mercant et al. studied 30 community-dwelling volunteers over the age of 60 who performed a sit-to-stand, stand-to-sit test while wearing an iPhone4 attached to the chest to assess 3D acceleration, angular velocity, and trunk displacement during the turn transition (32). The findings revealed all factors differed significantly between frail and non-frail subjects.

Parvaneh et al. conducted a study using a wearable necklace-like sensors located at the chest of 120 community-dwelling participants aged over 70 years old to monitor and assess postural transition differences among frailty levels for 24 h, and the results showed that the number of Stand-to-walk and total postural transitions were significantly different between groups (35). Millor et al. asked 47 community-dwelling volunteers over the age of 50 to perform stand-up and sit-down from a chair as many times as they could in 30 s while wearing an inertial orientation tracking sensors on their lumbar spine (33). The study showed that healthy participants outperformed frail people with less sway on the sit-to-stand cycle.

Therefore, the parameters derived from sensors attached to the trunk such as 3D acceleration, velocity and postural sway while doing physical function tests could discriminate frail and robust in the community-dwelling older adults.

Gait parameter

Gait assessment was another method used by researchers to analyze diagnostic variables in frail older adults. Zhou et al. investigated whether parameters from an instrumented trail making task (iTMT) and gait sensors worn on both shins to measure gait speed and iTMT derived parameters could distinguish between frail and robust participants (37). The findings revealed that gait speed and iTMT velocity were significant parameters that could help classify frailty status among the outpatient care population. Moreover, Jasen et al. carried out an intervention research which 112 community-dwelling older persons were requested to wear a wearable sensor in a shirt while undertaking a walking test under two conditions: (1) Walk a distance of 4.57 m at your own speed; and (2) Walking a 10-m distance as rapidly as possible (38). The findings correlated with the previous studies, which suggested that the proportion of time spent walking and standing, the maximum steps in one test bout, and walking speed might all be potential predictors of frailty classification (39).

Non-gait parameters

To determine frailty status, other variables could be used in addition to those mentioned above. Toosizadeh et al. studied the association between frailty status and non-gait parameters using a wearable gyroscope sensor attached to the upper arm and wrist of 117 community-dwelling adults over 65 years old to measure elbow function while performing a 50-s trail of elbow flexion in a seated position (34). The results revealed that the speed of elbow flexion, flexibility, and power of elbow flexion differed significantly between robust and frail participants. In the study by Castaneda-Gameros et al., moderate-to-vigorous physical activity measured by a sensor that records acceleration and gyroscopic data worn on the hip for 7 days was associated with frailty status in community-dwelling old adults (36). Additionally, Kikuchi et al. found the association of intensity-specific physical activity. The results showed that sedentary behavior and physical activity (moderate-to-vigorous) were significantly different between frail and robust in 511 Japanese community-dwelling participants aged over 65 (40).

As a result of the mentioned studies, there are multiple potential variables that could represent characteristics of frailty. Non-gait parameters appeared to have the highest clinical feasibility if researchers could integrate a model into a smartwatch since a wrist-worn device is simple to use and most older adults are already accustomed to wearing a smartwatch.

Diagnostic studies

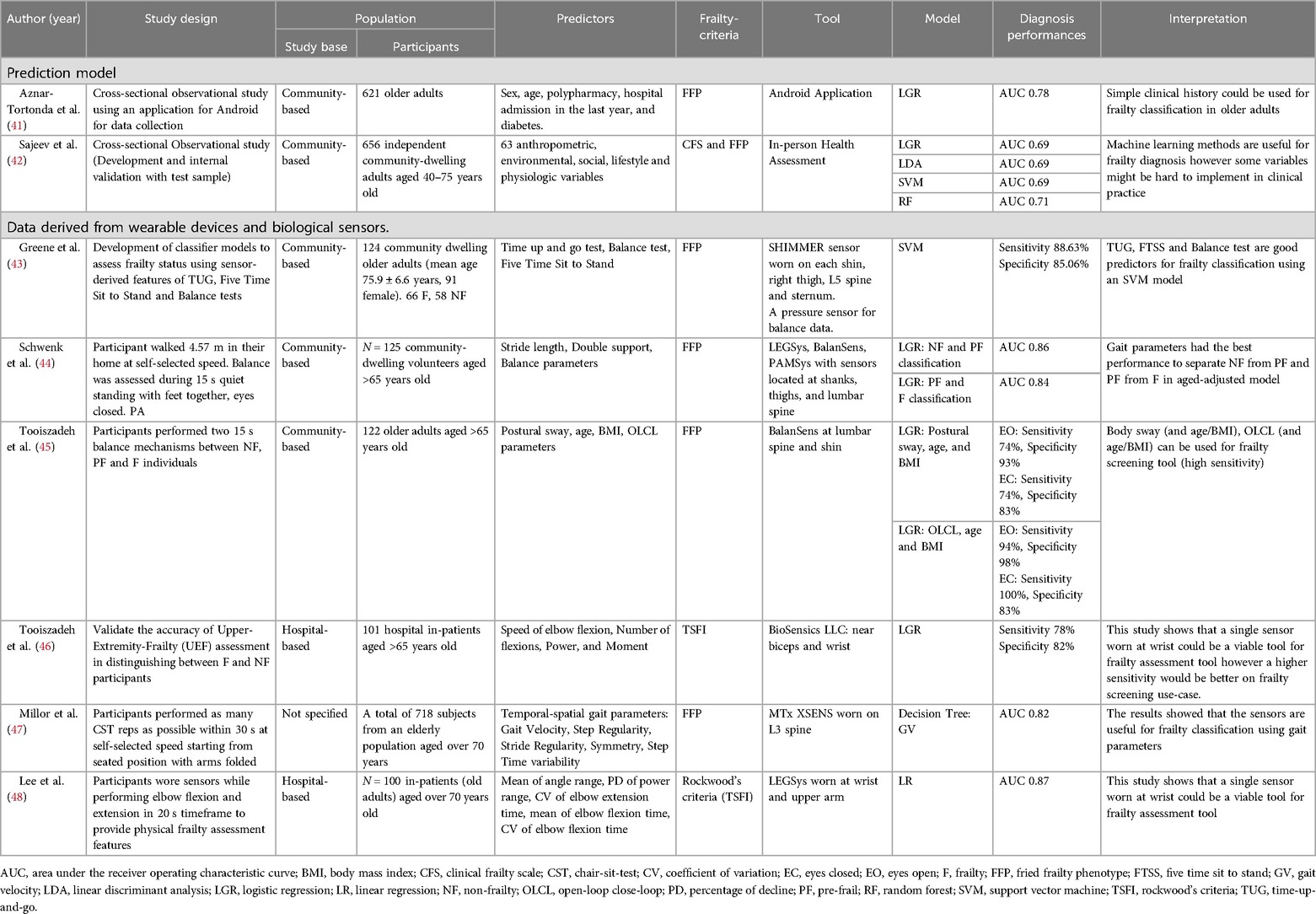

Frailty identification is a clinically relevant topic since it is a condition that may be reversed from frail to robust. Several studies are being conducted to develop tools and diagnostic models for classifying frail and non-frail older adults. According to the authors’ evaluation of the published evidence in this field, there are two types of frailty diagnostic tools that use technology: (1) Clinical Data; and (2) Data derived from wearable devices and biological sensors which are summarized in Table 2.

Clinical data

Aznar-Tortonda et al. collected data from 621 community-based participants in a cross-sectional observational study utilizing an Android mobile device application. Sex, age, polypharmacy, hospitalization, and diabetes history were chosen characteristics and employed in a logistic regression model (41). This model obtained an AUC of 0.78, suggesting that a brief clinical history might be utilized to classify frailty in older persons. Sajeev et al. used 20 anthropometric, environmental, social, lifestyle, and physiologic variables from 656 community-dwelling adults aged 40–65 years old to develop and internally validate four machine learning models, including logistic regression, linear discriminant analysis, support vector machine, and random forest (42). With an AUC of 70.8, the random forest model achieved the highest discrimination performance. This study found that machine learning models could be used to diagnose frailty. However, the large number of variables in the purposed models could make it difficult to implement them in clinical practices and community settings, and the selected features appeared to be more difficult to measure and more complicated than the standard diagnostic criteria for frailty. A future study is required to demonstrate the real-world application of a frailty diagnostic machine learning model based on clinical characteristic data.

Data derived from wearable devices and biological sensors

Most studies for biological sensors and wearable devices employ criteria similar to characteristics research. We divided the parameters into three major categories: (1) Physical Function test; (2) Gait and balance test; and (3) Non-gait-related test.

Physical function test

Greene et al. created a support vector machine classifier model based on characteristics gathered from 124 community-dwelling people who wore inertial and pressure sensors on each shin, right thigh, L5 spine, and sternum while undertaking Time-up-and-go, Five Time Sit to Stand, and Balance tests (43). Their model had 88.63% sensitivity and 85.06% specificity, indicating that the demonstrated tests had good frailty classifying characteristics. Schwenk et al. had 125 community-dwelling older adults walk 4.57 m in their home at their own pace, followed by a balance assessment while wearing multiple sensors on their shanks, thighs, and lumbar spine to collect gait and balance parameters for logistic regression model development (44). The results revealed an AUC of 0.857 for non-frail and pre-frail classification and an AUC of 0.841 for pre-frail and frail classification. The mentioned models have shown good and applicable discrimination performance.

Gait and balance test

Tooiszadeh et al. demonstrated that postural sway, age, and BMI parameters derived from sensors located at the lumbar spine and shin could predict frailty with 97% sensitivity and 88% specificity (45). Millor et al. developed decision tree models using gait characteristics acquired from an inertia sensor worn on the L3 spine of 718 senior volunteers aged over 70 years (47). With an AUC of 0.823–0.896, the results also demonstrated that gait characteristics and decision tree models were beneficial for frailty classification.

Upper extremity

According to Lee et al., participants wore accelerometers and gyroscope sensors at their wrist and upper arm while performing elbow flexion and extension in a 20-s timeframe to provide physical features such as the mean of the angle range coefficient of variation of elbow flexion and extension time and the mean of elbow movement time (48). These characteristics were used to develop a linear regression model with an AUC of 0.87. Tooiszadeh et al. created a logistic regression model utilizing upper-extremity frailty assessment data from a wearable gyroscope sensor, which was collected from the upper extremities of 101 hospital in-patients over the age of 65 (46). The study's performance was 78% sensitivity and 82% specificity. These studies demonstrated that a single non-gait-related sensor could be used to distinguish frailty and robustness in the elderly population.

In conclusion, research revealed that physical function tests, gait-related, and non-gait-related measures were useful in developing prediction models to diagnose frailty state in the aged population. However, the fitness test approach may be unsuitable for prospective frailty data collection because performing all the aforementioned fitness tests would take a significant amount of time to obtain the required feature in order to diagnose frailty in an individual, which may be comparable to simply performing tests according to Fried's criteria. We propose that future research should focus on upper extremity features because we believe that integrating a frailty predictive model into a smartwatch and mobile application has clinically significant implications.

Therapeutic studies

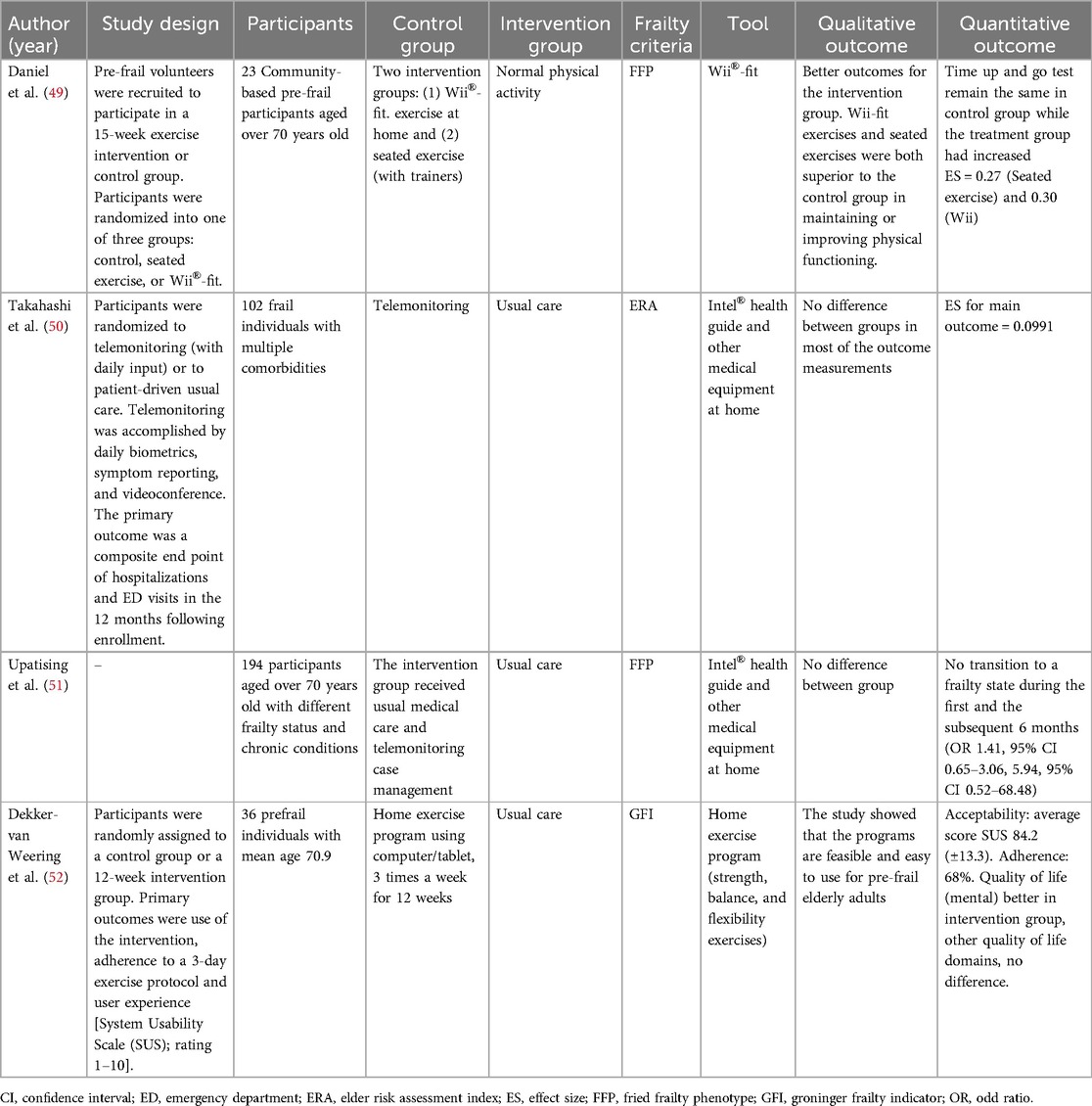

Based on the current evidence summarized in Table 3, pre-frail and frail older adults are recommended for multi-component physical activity program and progressive resistance training program. Multiple studies have shown improved cognitive function, physical function, and frailty status in older adults after physical exercise intervention. Therefore, our review selected frailty therapeutic studies that integrated the use of technology to improve frailty state in the elderly.

Daniel et al. conducted a study where 23 community-dwelling pre-frail volunteers aged over 70 years old were randomized into one of three groups: control, seated exercise, or Wii®-fit. The findings showed better outcomes for all intervention groups (49). Wii-fit exercises and seated exercises were both superior to the control group in maintaining or improving physical functions. Liao et al. recruited a randomized controlled trial of 52 prefrail and frail elderly where the participants were divided into two exercise intervention (1) Exergaming group and (2) Combined resistance, aerobic and balance exercise group for 36 sessions over 12 weeks (53). The results revealed both gaming exercise and combined exercise groups improved frailty status among the elderly. The study correlated with Moreira et al. where an RCT of 66 pre-frail older adults were assigned to either exergaming intervention and traditional multicomponent exercise (54). The findings showed that both programs were clinically effective for delaying frailty status and improving physical and cognitive function.

Exergaming have shown positive health outcomes in terms of enhancing physical function, cognitive function, and frailty status. The programs could be done in a home setting, making exercise intervention easily accessible. However, the majority of frail people are older adults, who may face challenges using technologies because of their lack of digital literacy and technology acceptance. One of the studies cited above had a dropout rate of over 30%, which suggests that a portion of older persons might not find the use of a digital intervention tool appropriate.

Discussion

From our review, we found that there are many potential etiognostic factors that could help diagnose frailty status using digital tools from trunk, gait, upper-extremity, and physical activity parameters. Researchers had used these parameters to create multiple well-performing models to classify frailty status in the older adults. We found non-gait parameters the most appealing variables for future research as a frailty diagnostic model integration into a wearable device. However, the model classification results should be interpreted with caution because these models may be overfitting due to a lack of external validation studies.

Regardless of the tools used, studies have shown that exercise can improve frailty status. Rather than developing a single standalone exercise platform, digital health technology developers should focus on how to implement these therapeutic platforms with health care providers or coaching platforms that could encourage and motivate prefrail and frail old adults to engage in more physical activity.

Integrating digital health tools into frailty diagnosis and management presents challenges, particularly in terms of adoption among older individuals. A study showed that Frailty was linked to both physical activity and technology adoption (55). In order to counteract frailty, this study suggests that older persons who are less receptive to technology engage in physical exercise. Another study showed that, whereas elderly people use mobile phones extensively, wearable device adoption is low and 63.2% of surveyed participants were unable to install or delete applications independently. Furthermore, pre-frail and frail older persons use healthcare apps more frequently than their healthy colleagues, showing a significant desire for health-related services situation, helping individuals enhance their health and cognitive abilities (56). This encourages researchers to develop solutions using digital health tools for frail older adults. However, the solutions should also be both user-friendly, gamified and engaging, ensuring active involvement and adherence for older populations.

Developing comprehensive platforms that integrate screening with therapeutic recommendations, such as apps providing tailored guidance on physical activity, diet, and medical consultations based on clinical guidelines for frailty might serve as a single resource for early screening and frailty intervention (57, 58). This could fit in the healthcare system by enabling early detection and giving interventions to the individual with risks, reducing the burden on physicians and patients by stratifying risks for efficient healthcare human resources management, and can be integrated with hospital systems to streamline care using data-driven insights from the frailty risk assessment models.

For instance, a study that developed and validated a fitness application for specific populations, like seafarers, demonstrated that they can improve physical activity and health outcomes by providing tailored physical training programs suitable for the maritime environment (59). This bridge the gaps between technology, frail individuals, healthcare professionals, and caregivers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the review highlights the promising role of digital health tools in addressing frailty among older adults. The use of sensor-derived metrics for upper extremity, trunk, and gait evaluation has improved the early detection of frailty and provided useful intervention options. Furthermore, therapeutic applications, such as exergaming and home-based programs, have demonstrated significant improvements in physical and cognitive functions, albeit with challenges related to technology acceptance among older adults. Our study underlines the necessity for future research to bridge the gap between frailty screening and therapeutic interventions by developing comprehensive, user-friendly digital platforms that combine diagnosis with personalized preventive care. This integrated approach has the potential to enhance health outcomes and quality of life for the aging population.

Author contributions

NI: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The APC was funded by Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by Chiang Mai University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Islam MS, Ng TKS, Manierre M, Hamiduzzaman M, Tareque MI. Modifications of traditional formulas to estimate and project dependency ratios and their implications in a developing country, Bangladesh. Popul Res Policy Rev. (2022) 41(5):1931–49. doi: 10.1007/s11113-022-09720-8

2. Kang’ethe S. Violation of human rights of older persons in South Africa. The case of lavela old age centre, Ntselamanzi, Eastern Cape province, South Africa. Soc Work Werk. (2018) 54(3):283. doi: 10.15270/52-2-649

3. World Population Prospects 2024: Methodology of the United Nations population estimates and projections.

4. Moon M, Guo J, McSorley VE. Is 65 the Best Cutoff for Defining “Older Americans?”. American Institutes for Research (2015). Available online at: https://www.air.org/resource/brief/65-best-cutoff-defining-older-americans (Accessed December 17, 2024).

5. World Bank. (cited 2024 December 17). World Bank Support to Aging Countries (Approach Paper). Available online at: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/870611561130594816/World-Bank-Support-to-Aging-Countries (Accessed June 21, 2019).

6. World population ageing, 2019: highlights. (2019). Available online at: http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3846855 (Accessed January 14, 2020).

7. Khanal A. Social condition of elderly people of Pashupati elderly’s home. J Popul Dev. (2022) 3(1):1–10. doi: 10.3126/jpd.v3i1.48800

8. Editorial: Ageing and nutrition in developing countries - Dangour - 2003 - Tropical Medicine & International Health - Wiley Online Library. (cited 2024 December 17). Available online at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01028_1.x (Accessed April 01, 2003).

9. World Population Ageing 2023: Challenges and opportunities of population ageing in the least developed countries | DESA Publications. (2024). (cited 2024 December 17). Available online at: https://desapublications.un.org/publications/world-population-ageing-2023-challenges-and-opportunities-population-ageing-least (Accessed December 17, 2024).

10. Bloom DE, Canning D, Fink G. Implications of Population Aging for Economic Growth. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network (2011). Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1748232

11. Ageing and health. (cited 2022 August 2). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (Accessed October 01, 2024).

12. Sabri SM, Annuar N, Rahman NLA, Musairah SK, Mutalib HA, Subagja IK. Major trends in ageing population research: a bibliometric analysis from 2001 to 2021. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. (2022) 82(1):19. doi: 10.3390/proceedings2022082019

13. MacNee W, Rabinovich RA, Choudhury G. Ageing and the border between health and disease. Eur Respir J. (2014) 44(5):1332–52. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00134014

14. da Costa GM, Sanchez MN, Shimizu HE. Factors associated with mortality of the elderly due to ambulatory care sensitive conditions, between 2008 and 2018, in the federal district, Brazil. PLoS One. (2022) 17(8):e0272650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272650

15. Ayaz T, Sahin SB, Sahin OZ, Bilir O, Rakıcı H. Factors affecting mortality in elderly patients hospitalized for nonmalignant reasons. J Aging Res. (2014) 2014:e584315. doi: 10.1155/2014/584315

16. Lekan DA, Collins SK, Hayajneh AA. Definitions of frailty in qualitative research: a qualitative systematic review. J Aging Res. (2021) 2021:6285058. doi: 10.1155/2021/6285058

17. Sternberg SA, Wershof Schwartz A, Karunananthan S, Bergman H, Mark Clarfield A. The identification of frailty: a systematic literature review. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2011) 59(11):2129–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03597.x

18. Srinonprasert V, Chalermsri C, Aekplakorn W. Frailty index to predict all-cause mortality in Thai community-dwelling older population: a result from a national health examination survey cohort. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2018) 77:124–8. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2018.05.002

19. British Geriatrics Society. (cited 2022 August 2). End of Life Care in Frailty: Falls. Available online at: https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/end-of-life-care-in-frailty-falls (Accessed May 12, 2020).

20. Cheng MH, Chang SF. Frailty as a risk factor for falls among community dwelling people: evidence from a meta-analysis: falls with frailty. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2017) 49(5):529–36. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12322

21. Davis-Ajami ML, Chang PS, Wu J. Hospital readmission and mortality associations to frailty in hospitalized patients with coronary heart disease. Aging Health Res. (2021) 1(4):100042. doi: 10.1016/j.ahr.2021.100042

22. Nguyen AT, Nguyen LH, Nguyen TX, Nguyen HTT, Nguyen TN, Pham HQ, et al. Frailty prevalence and association with health-related quality of life impairment among rural community-dwelling older adults in Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16(20):3869. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16203869

23. Robertson DA, Savva GM, Kenny RA. Frailty and cognitive impairment—a review of the evidence and causal mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev. (2013) 12(4):840–51. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.06.004

24. Castillo-Angeles M, Cooper Z, Jarman MP, Sturgeon D, Salim A, Havens JM. Association of frailty with morbidity and mortality in emergency general surgery by procedural risk level. JAMA Surg. (2021) 156(1):68–74. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5397

25. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2001) 56(3):M146–57. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146

26. Liu CK, Fielding RA. Exercise as an intervention for frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. (2011) 27(1):101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.001

27. Furtado G, Caldo A, Rodrigues R, Pedrosa A, Neves R, Letieri R, et al. Exercise-Based interventions as a management of frailty syndrome in older populations: design, strategy, and planning. In: Palermo S, editor. Frailty in the Elderly—Understanding and Managing Complexity. London: IntechOpen (2020). p. 1–10. Available online at: https://www.intechopen.com/state.item.id

28. Fairhall N, Kurrle SE, Sherrington C, Lord SR, Lockwood K, John B, et al. Effectiveness of a multifactorial intervention on preventing development of frailty in pre-frail older people: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. (2015) 5(2):e007091. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007091

29. Nakamura M, Ohki M, Mizukoshi R, Takeno I, Tsujita T, Imai R, et al. Effect of home-based training with a daily calendar on preventing frailty in community-dwelling older people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(21):14205. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192114205

30. Linn N, Goetzinger C, Regnaux JP, Schmitz S, Dessenne C, Fagherazzi G, et al. Digital health interventions among people living with frailty: a scoping review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2021) 22(9):1802–1812.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.04.012

31. Guasti L, Dilaveris P, Mamas MA, Richter D, Christodorescu R, Lumens J, et al. Digital health in older adults for the prevention and management of cardiovascular diseases and frailty. A clinical consensus statement from the ESC council for cardiology practice/taskforce on geriatric cardiology, the ESC digital health committee and the ESC working group on e-cardiology. ESC Heart Fail. (2022) 9(5):2808–22. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.14022

32. Galán-Mercant A, Cuesta-Vargas AI. Differences in trunk accelerometry between frail and nonfrail elderly persons in sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit transitions based on a mobile inertial sensor. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2013) 1(2):e21. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2710

33. Millor N, Lecumberri P, Gómez M, Martínez-Ramírez A, Izquierdo M. An evaluation of the 30-s chair stand test in older adults: frailty detection based on kinematic parameters from a single inertial unit. J NeuroEngineering Rehabil. (2013) 10(1):86. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-10-86

34. Toosizadeh N, Mohler J, Najafi B. Assessing upper extremity motion: an innovative method to identify frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2015) 63(6):1181–6. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13451

35. Parvaneh S, Mohler J, Toosizadeh N, Grewal GS, Najafi B. Postural transitions during activities of daily living could identify frailty status: application of wearable technology to identify frailty during unsupervised condition. Gerontology. (2017) 63(5):479–87. doi: 10.1159/000460292

36. Castaneda-Gameros D, Redwood S, Thompson JL. Physical activity, sedentary time, and frailty in older migrant women from ethnically diverse backgrounds: a mixed-methods study. J Aging Phys Act. (2018) 26(2):194–203. doi: 10.1123/japa.2016-0287

37. Zhou H, Razjouyan J, Halder D, Naik AD, Kunik ME, Najafi B. Instrumented trail-making task: application of wearable sensor to determine physical frailty phenotypes. Gerontology. (2019) 65(2):186–97. doi: 10.1159/000493263

38. Jansen CP, Toosizadeh N, Mohler MJ, Najafi B, Wendel C, Schwenk M. The association between motor capacity and mobility performance: frailty as a moderator. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. (2019) 16(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s11556-019-0223-4

39. Apsega A, Petrauskas L, Alekna V, Daunoraviciene K, Sevcenko V, Mastaviciute A, et al. Wearable sensors technology as a tool for discriminating frailty levels during instrumented gait analysis. Appl Sci. (2020) 10(23):8451. doi: 10.3390/app10238451

40. Kikuchi H, Inoue S, Amagasa S, Fukushima N, Machida M, Murayama H, et al. Associations of older adults’ physical activity and bout-specific sedentary time with frailty status: compositional analyses from the NEIGE study. Exp Gerontol. (2021) 143:111149. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2020.111149

41. Aznar-Tortonda V, Palazón-Bru A, dela Rosa DMF, Espínola-Morel V, Pérez-Pérez BF, León-Ruiz AB, et al. Detection of frailty in older patients using a mobile app: cross-sectional observational study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. (2020) 70(690):e29–35. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X706577

42. Sajeev S, Champion S, Maeder A, Gordon S. Machine learning models for identifying pre-frailty in community dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. (2022) 22(1):794. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03475-9

43. Greene BR, Doheny EP, Kenny RA, Caulfield B. Classification of frailty and falls history using a combination of sensor-based mobility assessments. Physiol Meas. (2014) 35(10):2053–66. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/35/10/2053

44. Schwenk M, Mohler J, Wendel C, D’’Huyvetter K, Fain M, Taylor-Piliae R, et al. Wearable sensor-based in-home assessment of gait, balance, and physical activity for discrimination of frailty Status: baseline results of the Arizona frailty cohort study. Gerontology. (2015) 61(3):258–67. doi: 10.1159/000369095

45. Toosizadeh N, Mohler J, Wendel C, Najafi B. Influences of frailty syndrome on open-loop and closed-loop postural control strategy. Gerontology. (2015) 61(1):51–60. doi: 10.1159/000362549

46. Toosizadeh N, Joseph B, Heusser MR, Orouji Jokar T, Mohler J, Phelan HA, et al. Assessing upper-extremity motion: an innovative, objective method to identify frailty in older bed-bound trauma patients. J Am Coll Surg. (2016) 223(2):240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.03.030

47. Millor N, Lecumberri P, Gomez M, Martinez A, Martinikorena J, Rodriguez-Manas L, et al. Gait velocity and chair sit-stand-sit performance improves current frailty-status identification. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. (2017) 25(11):2018–25. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2017.2699124

48. Lee H, Joseph B, Enriquez A, Najafi B. Toward using a smartwatch to monitor frailty in a hospital setting: using a single wrist-wearable sensor to assess frailty in bedbound inpatients. Gerontology. (2018) 64(4):389–400. doi: 10.1159/000484241

49. Daniel K. Wii-Hab for Pre-frail older adults. Rehabil Nurs. (2012) 37(4):195–201. doi: 10.1002/rnj.25

50. Takahashi PY, Pecina JL, Upatising B, Chaudhry R, Shah ND, Van Houten H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of telemonitoring in older adults with multiple health issues to prevent hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Arch Intern Med. (2012) 172(10):773–9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.256

51. Upatising B, Hanson GJ, Kim YL, Cha SS, Yih Y, Takahashi PY. Effects of home telemonitoring on transitions between frailty states and death for older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gen Med. (2013) 145:145–51. doi: 10.2147/ijgm.s40576

52. Weering MD-v, Jansen-Kosterink S, Frazer S, Vollenbroek-Hutten M. User experience, actual use, and effectiveness of an information communication technology-supported home exercise program for Pre-frail older adults. Front Med. (2017) 4:208. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00208

53. Liao YY, Chen IH, Wang RY. Effects of kinect-based exergaming on frailty status and physical performance in prefrail and frail elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. (2019) 9(1):9353. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45767-y

54. Moreira NB, Rodacki ALF, Costa SN, Pitta A, Bento PCB. Perceptive-Cognitive and physical function in prefrail older adults: exergaming versus traditional multicomponent training. Rejuvenation Res. (2021) 24(1):28–36. doi: 10.1089/rej.2020.2302

55. Kwan RYC, Yeung JWY, Lee JLC, Lou VWQ. The association of technology acceptance and physical activity on frailty in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. (2023) 20(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s11556-023-00334-3

56. Lee H, Choi JY, Wook KS, Ko KP, Park YS, Kim KJ, et al. Digital health technology use among older adults: exploring the impact of frailty on utilization, purpose, and satisfaction in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. (2023) 39(1):e7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e7

57. Dent E, Lien C, Lim WS, Wong WC, Wong CH, Ng TP, et al. The Asia-pacific clinical practice guidelines for the management of frailty. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2017) 18(7):564–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.04.018

58. Dent E, Morley JE, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Woodhouse L, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Fried LP, et al. Physical frailty: iCFSR international clinical practice guidelines for identification and management. J Nutr Health Aging. (2019) 23(9):771–87. doi: 10.1007/s12603-019-1273-z

Keywords: digital health tools, frailty, geriatrics, prevention, older adults

Citation: Isaradech N and Sirikul W (2025) Digital health tools applications in frail older adults—a review article. Front. Digit. Health 7:1495135. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2025.1495135

Received: 12 September 2024; Accepted: 12 February 2025;

Published: 3 March 2025.

Edited by:

Jie Li, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Giovanna Ricci, University of Camerino, ItalyTiming Liu, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom

Copyright: © 2025 Isaradech and Sirikul. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wachiranun Sirikul, d2FjaGlyYW51bi5zaXJAZ21haWwuY29t; d2FjaGlyYW51bi5zaXJAY211LmFjLnRo

†ORCID:

Wachiranun Sirikul

orcid.org/0000-0002-9183-4582

Natthanaphop Isaradech

Natthanaphop Isaradech Wachiranun Sirikul

Wachiranun Sirikul