- 1Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California, United States

- 2UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California, United States

- 3Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, Los Angeles, California, United States

- 4University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, Colorado, United States

- 5UCSF Departments of Medicine and Epidemiology and Statistics, San Francisco, California, United States

- 6UCSF Center for Vulnerable Populations, San Francisco General Hospital, San Francisco, California, United States

Objectives: The start of the COVID-19 pandemic led the Los Angeles safety net health system to dramatically reduce in-person visits and transition abruptly to telehealth/telemedicine services to deliver clinical care (remote telephone and video visits). However, safety net patients and the settings that serve them face a “digital divide” that could impact effective implementation of such digital care. The study objective was to examine attitudes and perspectives of leadership and frontline staff regarding telehealth integration in the Los Angeles safety net, with a focus on telemedicine video visits.

Methods: This qualitative study took place in the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (LAC DHS), the second-largest safety net health system in the US. This system disproportionately serves the uninsured, Medicaid, racial/ethnic minority, low-income, and Limited English Proficient (LEP) patient populations of Los Angeles County. Staff and leadership personnel from each of the five major LAC DHS hospital center clinics, and community-based clinics from the LAC DHS Ambulatory Care Network (ACN) were individually interviewed (video or phone calls), and discussions were recorded. Interview guides were based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), and included questions about the video visit technology platform and its usability, staff resources, clinic needs, and facilitators and barriers to general telehealth implementation and use. Interviews were analyzed for summary of major themes.

Results: Twenty semi-structured interviews were conducted in August to October 2020. Participants included LAC DHS physicians, nurses, medical assistants, and physical therapists with clinical and/or administrative roles. Narrative themes surrounding telehealth implementation, with video visits as the case study, were identified and then categorized at the patient, clinic (including provider), and health system levels.

Conclusions: Patient, clinic, and health system level factors must be considered when disseminating telehealth services across the safety net. Participant discussions illustrated how multilevel facilitators and barriers influenced the feasibility of video visits and other telehealth encounters. Future research should explore proposed solutions from frontline stakeholders as testable interventions towards advancing equity in telehealth implementation: from patient training and support, to standardized workflows that leverage the expertise of multidisciplinary teams.

Introduction

Digital health care has expanded over the past decade, largely driven by the financial incentives of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Meaningful Use program, part of federal health care reform. In the last few years, safety net systems (1), health systems that provide a significant level of care to minority, low-income, Limited English Proficient (LEP), and other patients from under-resourced backgrounds, have implemented digital tools for the first time. Since safety net patients already face social barriers related to the effort and cost of accessing in-person care such as taking unpaid time off from needed work, and transportation costs—digital health is an important tool for improving health equity in this group (2–9). Telehealth services like patient portals and telemedicine phone and video visits have the potential to augment access to health care and improve outcomes (10–16).

\Coupled to this, the Coronavirus-19 disease (COVID-19) pandemic propelled telehealth into the forefront as a clinical mechanism towards maintaining access to health care during a global shut down (as has occurred during other times of crisis) (17–29). However, this forced and uncharted transition immediately raised concerns about equitable access for safety net patients (3, 30, 31). Health leaders and researchers have documented how the abrupt shift from in-person visits to telemedicine with COVID-19 left many safety net health systems ill-prepared to support digital uptake (3, 31–33), especially among historically and contemporarily underserved patient groups (3, 31, 33, 34). Among those most left behind in the digital health waves are the 22.3 million LEP residents of the US (35), who already experience health access barriers due to language and literacy (36–40) that place them at higher risk for inadequate disease control, higher utilization of acute care, and poor health outcomes (41–43). A study examining Kaiser Permanente patients from 2016 to 2018 found that populations with non-English language preference were significantly less likely to access a telehealth visit than English-speakers, and that patients living in low SES areas were less likely to have a video visit than those living in higher SES neighborhoods (44). Early evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic confirmed lower rates of telehealth visits for older, non-White, and LEP patients (3, 31–33, 45).

With no established digital guidance in place for safety net settings prior to the pandemic, the evidence demonstrates that telehealth in health settings that care patients from underserved backgrounds will have to be monitored as implementation evolves—to understand and mitigate barriers to use. As such, studying telehealth implementation within safety net settings is critical for developing multi-level solutions that advance digital health equity. Therefore, to explore strategies and barriers to telehealth implementation in the safety net, we focused on the highest quality synchronous telehealth modality as the study case example—video visits—within the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (LAC DHS), the second largest municipal healthcare system in the US. The objective of this study was to interview health system leadership and frontline clinical staff to understand their perspectives on, and experiences with the delivery of video visits during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to also inform subsequent telehealth implementation efforts in this safety net, and nationwide.

Methods

Study design and setting

LAC DHS forms the core of the health care safety net for indigent populations in Los Angeles County—the largest and most ethnically diverse county in the US. Over 50% of the primary care patient population is LEP (46–49). This safety net health system serves more than 10 million residents and provides over 2.5 million ambulatory visits every year across Los Angeles County. Between August and October 2020, we conducted in-depth individual interviews with LAC DHS stakeholders who, at the time, were implementing some of the first telemedicine video visits in their respective Los Angeles safety net clinics.

Participants and recruitment

Individuals were recommended for interview by a study co-investigator (AA) who is the LAC DHS medical director for patient engagement and population health. Participants were nominated given their role in the implementation of video visit “pilots” at clinics across LAC DHS (spring 2020). Potential participants were emailed to inform them about the study. Participants could also nominate other stakeholders involved or leading the pilot video visits (e.g., snowball sampling). Those who responded and accepted were scheduled for a 1-hour video or phone interview. Each participant was offered a $50 Amazon gift card for participation. The study was approved by the UCLA and LAC DHS Institutional Review Board.

Data collection and analysis plan

We based our interview guide on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), a conceptual framework that guides systematic assessment of multilevel contexts to identify factors that might influence implementation and effectiveness (50). The questions were also based on the published digital health literature among safety net patients in the United States (AC and CL) (32, 51–67), and further amended by our study team, which included LAC DHS stakeholders (AA, GG, CM). The interviews (conducted by AC) included questions on: the debut of video visits in clinics, the preparation and process for clinics, staff, and patients to offer, schedule, and conduct video visits, and how these video pilots evolved or changed over time, and adaptions. Questions probed around issues surrounding technology platform, usability, staff resources, clinic needs, and stakeholder perceptions of facilitators and barriers. We asked interviewees to consider these discussions for the unique strata of patients served by LAC DHS: LEP, digital/health literacy challenges, and limited access to Internet and/or Internet-connected software and devices. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. Transcriptions were independently read by 3 members of the research team (AC, EW, CV) to develop a codebook. Two coders analyzed the interview transcripts (AC, CV) to organize participant quotes under unifying themes.

Results

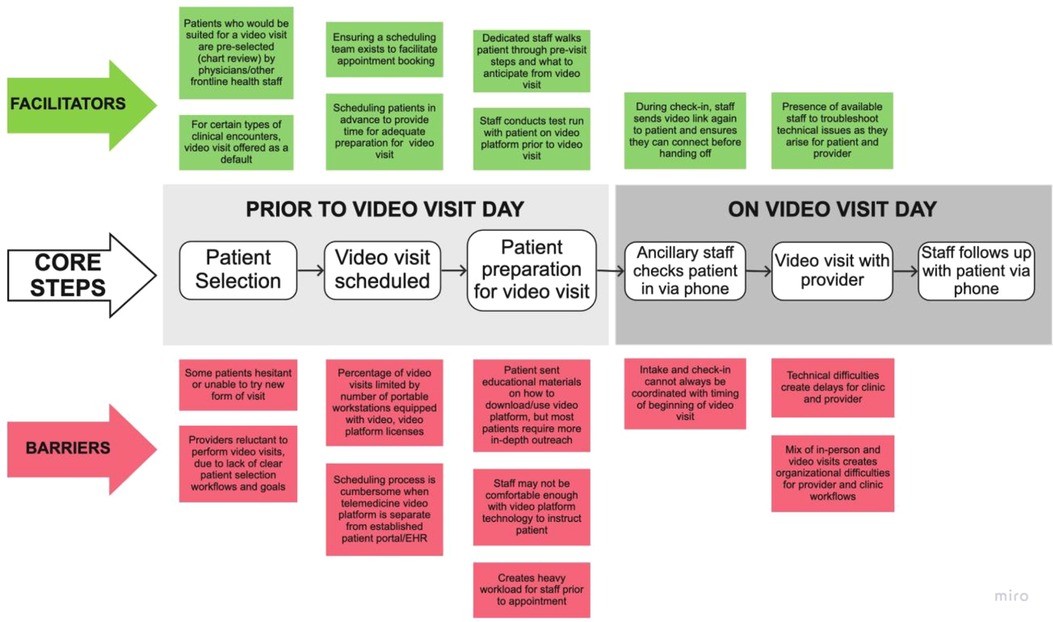

Of 27 stakeholders that were nominated, 20 individuals accepted and these semi-structured interviews were conducted between August–October 2020. Participants included physicians, nurses, medical assistants, and physical therapists with clinical and/or administrative roles (Table 1). Participants were either: primarily based at one of five major hospital/clinic medical centers that are part of the LAC DHS health system (DHS site) or worked within LAC DHS’ network of 26 non-hospital affiliated community health centers and community clinics all over Los Angeles (Ambulatory Care Network, ACN). Narrative themes surrounding telehealth implementation in the Los Angeles safety net are organized into patient, clinic/provider, and health system levels that correspond to constructs in the CFIR, with accompanying exemplar quotations (Table 2).

Table 1. Safety-net Stakeholders’ clinical role/training and operational/leadership role relevant to telehealth implementation (n = 20).

Patient level themes (CFIR Outer Setting)

Patient level themes corresponded to the CFIR “Outer Setting” construct, detailing conversations regarding patient needs and resources and patient influences in implementation feasibility.

Patient preparedness

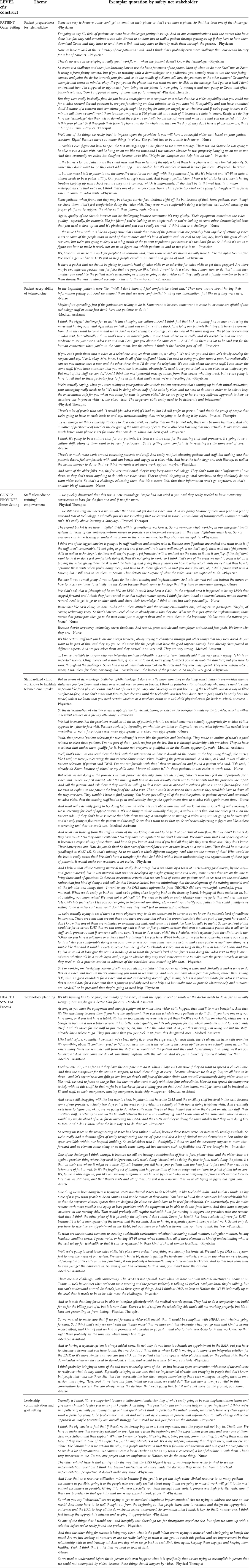

Conversations about patient preparedness encompassed digital health barriers in the patient's context that could affect the feasibility of telehealth for the safety net. Stakeholders described barriers to use of existing digital health tools due to a “digital divide” for their populations, characterized by low digital literacy, limited broadband and/or cell phone data plans, and lack of access to Internet-connected personal devices (and/or high quality digital devices). Other technology-specific challenges included patient usability of the LAC DHS telehealth interface and the English-only language of the current platform. Stakeholders noted that the current video visit system required multiple steps on behalf of the patient (see Figure 1 process map), which were challenging for most patients. Furthermore, a “successful” (i.e., completed) video visit usually depended on many staff phone calls in advance of the encounter. This was noted as not sustainable for staff given constrained resources and time. Some clinic staff indicated that their clinics had resorted to “selecting” for patients who they thought could complete a video visit, and promoted it among these groups. However, they also noted that this was not equitable, as it was unfair to promote video visits among a subset of patients—when potentially all safety net patients could benefit from the service.

Patient acceptability

Stakeholders also discussed patient acceptability, with specific conversations centering around a culture shift with regards to telehealth. Stakeholders shared how so much has been taken away from the large proportions of racial and ethnic minority communities served by the Los Angeles safety net—due not only to COVID-19, but also because of historical and contemporary systemic injustices. The threat of losing a personal connection to their doctor and health system was a perceived fear from their patients. Stakeholders suggested eliciting and directly acknowledging concerns about telehealth with patients, and then following up with discussions about benefits as a way to assuage misconceptions while shifting the patient culture about expectations for clinical visits. The goal would be to normalize telehealth visit offerings as part of high quality clinical practice.

Clinic/provider level themes (CFIR Inner Setting)

Clinic and provider level themes corresponded to the CFIR's “Inner Setting” construct—detailing issues regarding clinic characteristics such as networks and communications, workflows, culture and climate.

Staff telemedicine training and empowerment

Participants felt that leadership assumed that frontline staff, who interface the most with patients, would be familiar with telehealth and able to promote it. However, this was not always the case, as some staff were not comfortable with the technology and had not used telehealth visits or a patient portal themselves. Participants discussed the need for more recognition of the different comfort and electronic health literacy levels of staff and medical providers and endorsed a need for effective training during implementation (including “refreshers” or updates about the technology) and immediate contacts for troubleshooting problems. In these discussions, participants talked about identifying ideal staff to serve as telehealth “champions,” delineated characteristics of champions, and ways to support/reward champions, that would help in telehealth promotion and facilitation within clinics.

Standardized clinic workflows to facilitate telehealth uptake

Stakeholders discussed the informal use of workflows to identify appropriate clinical scenarios for telehealth. In the video visit pilots, this was being done ad hoc by physicians and other medical staff. It was stated that systematic identification of clinical visit types ideal for telehealth (medicine reconciliation, diabetes coaching, treatment discussions) could potentially be created, with algorithms or workflows to automatically match these to telehealth offerings (especially within each clinical specialty). Participants mentioned that such efforts could save time for nurses and doctors. Staff thought that automatized offerings could promote telehealth uptake, as patients would probably be less proactive about asking for video visits, given their low baseline awarenes and knowledge about telehealth in the safety net. The other major operational workflow that participants mentioned was the need to integrate digital readiness patient screening or assessment tools as part of clinical care. During early phases of implementation, providers spent time trying to “identify” ideal candidates to offer a telehealth visit to (e.g., those registered to a patient portal, had an email account on file in the health record, or who used apps on their phone). While this identification process was somewhat helpful to increase the yield on completed telehealth video visits, obtaining this information required extra time during the visit and limited the service to subgroups of patients. Participants brought up the potential of digital screening tools to increase immediate yield of visits and help identify patient needs and allocate resources for support. For example, a pre-visit preparation session could help make video visits more accessible to those who most needed it and troubleshoot connectivity and other problems. However, participants noted that this screening process would require a standardized tool, such as a set of validated predictor questions that could quickly and easily identify patient's needs for support. Without a uniform approach and systematic guidance, too high a burden would be placed on staff and providers.

Health system level themes (CFIR Process)

Themes that corresponded to the health system mostly reflected CFIR factors regarding the planning, engaging, execution, reflection, and evaluation over telehealth implementation.

Technology planning

Among the barriers cited were lack of planning for needed equipment and ancillary resources: such as not enough computers with cameras in the clinic, lack of physical space to expand telehealth given constraints of a simultaneous in-person and telehealth visit schedule for providers in a county clinic with a shortage of clinic rooms, need for differentiating telehealth visit procedures from in-person visits (e.g., a required “nurse intake” for a telehealth visit may not be useful), challenges with broadband Internet access in clinic such as poor Internet reception in some of the county clinics, lack of systemwide IT support to facilitate early implementation, and video visits not integrated with the system's current patient portal.

Leadership communication and goal setting

Participants endorsed the importance of routine telehealth discussions between leadership, IT, and front-line staff, especially for the sharing of best operational practices, digital educational tools for patients (and staff), and patient-centered digital engagement across different sites in this large county health system. Most participants recommended that the health system invest more to support patient education that impacted preparedness for telehealth access and high quality utilization. They described feeling like they were designing these processes in real time. Additionally, although tailoring to their specific settings is needed, they would have benefited from learning about other clinical sites' models, approaches, and “mistakes,” particularly those sites that started earlier with telehealth implementation. They called for LAC DHS to develop more centralized patient and staff telehealth educational resources.

Participants also discussed being “unclear” about the goals of the implementation, expectations from leadership and what telehealth “success” looked like in the safety net. Did this mean that all patients should be using video visits or a goal number or percentage of visits by some date? Would these metrics be uniform across specialties and clinic sites? The stakeholders we interviewed felt it would be important to have staff partner with leadership in asking these questions and in goal setting. They also emphasized the importance of transparency about specific telehealth goals and regular updates to their frontline staff. Participants also mentioned that these metrics should be set with the overarching aim of offering the highest quality of care possible to their patients and not for the sake of simply reaching some arbitrary telehealth uptake or usage metric at LAC DHS. Finally, participants noted that without measurable telehealth goals, objectives and metrics, there was less incentive and accountability to continue the use of video visits beyond the pilot phase.

Discussion

This qualitative study of informed safety net stakeholders presents some important multilevel lessons learned around telehealth implementation in settings caring for historically and contemporarily underserved patient populations. Of note, thematic narratives from these interviews highlighted the following takeaways: patients' longstanding risk for and history of the digital divide must be addressed up front, with the aid of trained multidisciplinary teams, established workflows tailored to each clinical setting that facilitate telehealth, and with clear communication and partnership between safety net leadership and on-the-ground staff about the objectives and goals for telehealth care for their patients. Most participants stressed the need for the health system to invest more resources to support patient engagement and education that impacted preparedness for telehealth access and high quality utilization. If these challenges are not addressed, this could be a set-up for worsening health disparities for these patients (not only LA safety net patients, but all over the US), already at higher risk of poor disease management outcomes.

Our study does reinforce the findings of prior digital health literature regarding the need to better understand patient preparedness for telemedicine. This includes several dimensions for digital access and uptake which have been described in the digital divide literature addressing safety net patient populations—(51–67) including devices and data plans as well as clear expectations for digital skills from more basic (opening an app) to more sophisticated skills like finding, sending, and/or interpreting health information digitally (68–73). Discussions of digital health equity must also address patient acceptability of telemedicine, with specific conversations centering around a culture shift for patients. The safety net serves a large proportion of minority patients, with populations that value a personal relationship with the doctor (i.e., “familismo” in the Latina/o/x community, a primary ethnic minority population served by LAC DHS) (74). The introduction of video or phone visits is an adjustment for patients, and requires reassurance that their patient-doctor relationships would be conserved, something that has been noted in early patient portal studies within the safety net, especially among Black patients (75).

Our study adds new content around the readiness and culture of providers and staff to deliver telemedicine, which is not actively explored in previous literature. Participants discussed that there was almost an assumption made by leadership that frontline safety net staff interfacing the most with patients would be comfortable using these new telehealth tools. Future implementation will have to focus on the technology needs and understanding of the workforce, and staff telehealth training and empowerment for those at the front lines of the health technology implementation in the safety net (76). Also, much of the discussion at the clinic and provider level revolved around the extra use of resources to identify high quality clinical scenarios and appropriately identifying what support patients needed to use the video visit service, to meet these unmet digital needs (52, 77–79). In a busy and under-resourced setting, the concept of standardized clinic workflows to facilitate telehealth uptake is an approach for this, and has been recommended by other organizations who have focused on digital health uptake in safety net settings (79).

Health system-specific challenges in the discussions encompassed technology planning barriers like usability and the English-only language of the video visit platform, which has also been previously discussed in the literature as major factors (80–83). Participants mentioned the lack of infrastructure in clinic spaces and the incompatibilities with concurrent in-person and telehealth visits functioning efficiently for a provider in the same clinic workrooms and nurse teams. In terms of leadership communication and goal setting, there was a clear need for more partnered goal setting around telehealth implementation, and transparency of process. Of note, these early stakeholder discussions have led to the development of the LAC DHS Virtual Care Workgroup, a consortium of LAC DHS primary care clinic directors, patients and community advocates from Patient Family Advisory Councils (PFAC's), interpreter services, social work and chronic disease health educators. This workgroup has been meeting every week since the spring of 2021 to help shape LAC DHS local telehealth policy and determine the evidence-based interventions needed to appropriately deliver effective telehealth. Some recent innovations borne out of this workgroup include: addition of telehealth (video visits, patient portal) tutorials into educational content delivered by health educators in their chronic disease self-management classes for LAC DHS patients, and the development of a health technology navigator community health worker corps with health technology navigators “stationed” at various LAC DHS clinic waiting rooms—helping patients enroll and use their portal and become familiar with other telehealth offerings while they wait for their in-person appointments.

Study limitations included the small sample size of staff and leadership who were nominated to participate in the interviews, and limited generalizability to safety net health systems outside of Los Angeles County. This study focused on workforce and leadership stakeholder perspectives in the implementation—however, research centered around patient perspectives will be needed to validate changes, and advance substantial progress. In addition, this study did not address the relevant role of external policies like Medicaid reimbursement of phone and video visits, impact of patient-centered staff such as health educators and community health workers (who have been shown to improve digital health uptake in these settings), and availability of telehealth platforms and technology support in multiple non-English languages—all of which have been shown to be critical factors in the sustainability of telehealth in the safety net (84). Future research will need to more fully explore these in safety net settings to ensure that evidence-based factors that affect long-term high quality telehealth for these patients are addressed.

Overall, the purpose of this formative study was to generate initial health stakeholder insights regarding meaningful telehealth implementation for safety net patients and settings, as all health systems around the country are integrating remote strategies to reach out to patients, even beyond COVID-19. Although telehealth is not a full replacement for all in-person health care, it is important to note that telehealth is an added and complimentary clinical tool to address longstanding and continued health access inequities among underserved patients, if implemented appropriately in these settings. Because Los Angeles County is the largest and most ethnically diverse county in the country, these unique insights will be applicable to safety net systems across the US who are working to augment access to care and prevent worsening of chronic disease conditions among their patients. This augmented access will be especially needed after the disproportionate physical and mental health traumas inflicted upon this safety net population from COVID-19—effects that will resonate years beyond the end of the pandemic.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by UCLA. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

All authors listed have contributed sufficiently to the project to be included as authors, and all those who are qualified to be authors are listed in the author byline. To the best of our knowledge, no conflict of interest, financial or other, exists. AC conducted the study. AC and AA designed the study. AC, CV, and EW carried out the analysis. CRL, CM, GG, and AB guided all aspects of the study from a research and operational/stakeholder perspective. AC wrote the manuscript with secondary writing from CV and EW. All other authors edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study is supported by career development awards for Casillas to support this work: UCLA K12 funded by AHRQ and PCORI, as well as a K23 from NIMHD. CRL was supported by NIDDK Center Grant (DK092924) and a UCSF-Genentech mid-career award for advancing health equity.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Safety Net. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [Internet]. Ahrq.gov. 2021 [cited 2021 Feb 4]; Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/topics/safety-net.html.

2. Casillas A, Abhat A, Mahajan A, Moreno G, Brown AF, Simmons S, et al. Portals of change: how patient portals will ultimately work for safety net populations. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22(10):e16835. doi: 10.2196/16835

3. Nouri S, Khoong EC, Lyles CR, Karliner L. Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the COVID-19 pandemic. NEJM Catalyst Innov Care Deliv. (2020) 1(3):1–13. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0123

4. Lyles C, Fields J, Lisker S, Sharma A, Aulakh V, Sarkar U. Launching a toolkit for safety-net clinics implementing telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. To the Point (blog), Commonwealth Fund (2020). https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/launching-toolkit-safety-net-clinics-implementing-telemedicine-during-covid-19-pandemic [accecced 2022 Mar 25], doi: 10.26099/df1p-7x02

5. Resources for Telehealth at Safety Net Settings | Center for Vulnerable Populations [Internet]. Ucsf.edu. 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 27]. Available from: https://cvp.ucsf.edu/telehealth.

6. Becker J. How Telehealth Can Reduce Disparities, BILL OF HEALTH: BLOG,September 11, 2020. [cited 2021 Jan 28]; Available at: https://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2020/09/11/telehealth-disparities-health-equity-covid19/.

7. Telediagnosis for Acute Care: Implications for the Quality and Safety of Diagnosis. Telehealth and Health Disparities. [Internet]. Ahrq.gov. 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 27]; Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/reports/issue-briefs/teledx-5.html.

8. Sutton JP, Washington RE, Fingar KR, Elixhauser A. Characteristics of Safety-Net Hospitals, 2014: Statistical Brief #213. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD) (2006).

9. Li V, McBurnie MA, Simon M, Crawford P, Leo M, Rachman F, et al. Impact of social determinants of health on patients with complex diabetes who are served by national safety-net health centers. J Am Board Fam Med. (2016) 29(3):356–70. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150226

10. Car J, Sheikh A. Email consultations in health care: 1–scope and effectiveness. Br Med J. (2004) 329(7463):435–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7463.435

11. Car J, Sheikh A. Telephone consultations. Br Med J. (2003) 326(7396):966–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7396.966

12. Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, Schore J, Razafindrakoto CM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Aff (Millwood). (2012) 31(6):1156–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0393

13. Green BB, Cook AJ, Ralston JD, Fishman PA, Catz SL, Carlson J, et al. Effectiveness of home blood pressure monitoring, web communication, and pharmacist care on hypertension control: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. (2008) 299(24):2857–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.24.2857

14. Ralston JD, Hirsch IB, Hoath J, Mullen M, Cheadle A, Goldberg HI. Web-based collaborative care for type 2 diabetes: a pilot randomized trial. Diabetes Care. (2009) 32(2):234–9. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1220

15. McGeady D, Kujala J, Ilvonen K. The impact of patient-physician web messaging on healthcare service provision. Int J Med Inform. (2008) 77(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.11.004

16. Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. Transforming primary care: from past practice to the practice of the future. Health Aff (Millwood). (2010) 29(5):779–84. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0045

17. Rudowitz R, Rowland D, Shartzer A. Health care in New Orleans before and after Hurricane Katrina. Health Aff (Millwood). (2006) 25(5):w393–w406. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w393

18. Krousel-Wood MA, Islam T, Muntner P, Stanley E, Phillips A, Webber LS, et al. Medication adherence in older clinic patients with hypertension after Hurricane Katrina: implications for clinical practice and disaster management. Am J Med Sci. (2008) 336(2):99–104. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318180f14f

19. Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory G, Kessler RC. Hurricane Katrina’s impact on the care of survivors with chronic medical conditions. J Gen Intern Med. (2007) 22(9):1225–30. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0294-1

20. Malik S, Lee DC, Doran KM, Grudzen CR, Worthing J, Portelli I, et al. Vulnerability of older adults in disasters: emergency department utilization by geriatric patients after hurricane sandy. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2018) 12(2):184–93. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2017.44

21. Pearlman DN, O’Connell S, Kaw D, Dona Goldman R. Predictors of non-completion of community-based chronic disease self-management programs: The Rhode Island experience during an economic recession. R I Med J (2013). (2015) 98(6):47–50. PMID: 26020266

22. O’Toole TP, Buckel L, Redihan S, DeOrsey S, Sullivan D. Staying healthy during hard times: the impact of economic distress on accessing care and chronic disease management. Med Health R I. (2012) 95(11):363–6. PMID: 23477281

23. Sharma AJ, Weiss EC, Young SL, Stephens K, Ratard R, Straif-Bourgeois S, et al. Chronic disease and related conditions at emergency treatment facilities in the New Orleans area after Hurricane Katrina. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2008) 2(1):27–32. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31816452f0

24. Mokdad AH, Mensah GA, Posner SF, Reed E, Simoes EJ, Engelgau MM, et al. When chronic conditions become acute: prevention and control of chronic diseases and adverse health outcomes during natural disasters. Prev Chronic Dis. (2005) 2 (Spec no):A04. PMID: 16263037; PMCID: PMC1459465.

25. Burke MP, Martini LH, Cayir E, Hartline-Grafton HL, Meade RL. Severity of household food insecurity is positively associated with mental disorders among children and adolescents in the United States. J Nutr. (2016) 146(10):2019–26. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.232298

26. Tsubokura M, Hara K, Matsumura T, Sugimoto A, Nomura S, Hinata M, et al. The immediate physical and mental health crisis in residents proximal to the evacuation zone after Japan’s nuclear disaster: an observational pilot study. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2014) 8(1):30–6. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2014.5

27. Evans-Lacko S, Knapp M, McCrone P, Thornicroft G, Mojtabai R. The mental health consequences of the recession: economic hardship and employment of people with mental health problems in 27 European countries. PLoS One. (2013) 8(7):e69792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069792

28. Der-Martirosian C, Chu K, Dobalian A. Use of telehealth to improve access to care at the US department of veterans affairs during the 2017 atlantic hurricane season. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2020) 1–5. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.88

29. Der-Martirosian C, Heyworth L, Chu K, Mudoh Y, Dobalian A. Patient characteristics of VA telehealth users during hurricane harvey. J Prim Care Community Health. (2020) 11:2150132720931715. doi: 10.1177/2150132720931715

30. Kaplan J. Hospitals have left many COVID-19 patients who don’t speak English alone, confused and without proper care. ProPublica. (2020) [cited 2022 Mar 15]; Avaiable from https://www.propublica.org/article/hospitals-have-left-many-covid19-patients-who-dont-speak-english-alone-confused-and-without-proper-care

31. How the telemedicine boom threatens to increase inequities [Internet]. AAMC (2020) [cited 2021 Feb 4]; Available from: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/how-telemedicine-boom-threatens-increase-inequities.

32. Schillinger D.Literacy and health communication: reversing the “inverse care law”. Am J Bioeth. (2007) 7(11):15–8; discussion W1-2. doi: 10.1080/15265160701638553

33. Coughlin TA, Ramos C, Samuel-Jakubos H. Safety Net Hospitals in the Covid-19 Crisis: How Five Hospitals Have Fared Financially. Available from: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103483/safety-net-hospitals-in-the-covid-19-crisis-how-five-hospitals-have-fared-financially_0.pdf2020.

34. Jain V, Al Rifai M, Lee MT, Kalra A, Petersen LA, Vaughan EM, et al. Racial and geographic disparities in internet use in the U.S. among patients with hypertension or diabetes: implications for telehealth in the era of COVID-19. Diabetes Care. (2021) 44(1):e15–7. doi: 10.2337/dc20-2016

36. Flores G. Language barriers to health care in the United States. N Engl J Med. (2006) 355(3):229–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058316

37. Kim EJ, Kim T, Paasche-Orlow MK, Rose AJ, Hanchate AD. Disparities in hypertension associated with limited English proficiency. J Gen Intern Med. (2017) 32(6):632–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-3999-9

38. DuBard CA, Gizlice Z. Language spoken and differences in health status, access to care, and receipt of preventive services among US Hispanics. Am J Public Health. (2008) 98(11):2021–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119008

39. Schulson L, Novack V, Smulowitz PB, Dechen T, Landon BE. Emergency department care for patients with limited English proficiency: a retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. (2018) 33(12):2113–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4493-8

40. Anderson TS, Karliner LS, Lin GA. Association of primary language and hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Med Care. (2020) 58(1):45–51. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001245

41. Rawal S, Srighanthan J, Vasantharoopan A, Hu H, Tomlinson G, Cheung AM. Association between limited English proficiency and revisits and readmissions after hospitalization for patients with acute and chronic conditions in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. JAMA. (2019) 322(16):1605–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.13066

42. Casillas A, Perez-Aguilar G, Abhat A, Gutierrez G, Olmos-Ochoa TT, Mendez C, et al. Su salud a la mano (your health at hand): patient perceptions about a bilingual patient portal in the Los Angeles safety net. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2019) 26(12):1525–35. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz115

43. Sentell T, Braun KL. Low health literacy, limited English proficiency, and health status in Asians, Latinos, and other racial/ethnic groups in California. J Health Commun. (2012) 17(Suppl 3):82–99. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.712621

44. Reed ME, Huang J, Graetz I, Lee C, Muelly E, Kennedy C, et al. Patient characteristics associated with choosing a telemedicine visit vs office visit with the same primary care clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3(6):e205873. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5873

45. Ferguson JM, Jacobs J, Yefimova M, Greene L, Heyworth L, Zulman DM. Virtual care expansion in the veterans health administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2021) 28(3):453–62. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa284

46. Daskivich LP, Vasquez C, Martinez C Jr, Tseng CH, Mangione CM. Implementation and evaluation of a large-scale teleretinal diabetic retinopathy screening program in the Los Angeles county department of health services. JAMA Intern Med. (2017) 177(5):642–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0204

47. Towfighi A, Cheng EM, Ayala-Rivera M, McCreath H, Sanossian N, Dutta T, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a coordinated care intervention to improve risk factor control after stroke or transient ischemic attack in the safety net: secondary stroke prevention by Uniting Community and Chronic care model teams Early to End Disparities (SUCCEED). BMC Neurol. (2017) 17(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0792-7

48. Wikipedia Contributors. Los Angeles County Department of Health Services [Internet]. Wikipedia (2020) [cited 2021 Jan 27]; Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Los_Angeles_County_Department_of_Health_Services.

49. Diabetes Continues to Increase in Los Angeles County. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health News Release. November 1, 2016. Available from: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/diabetes/docs/Press_Release_Diabetes_Continues_to_Increase_in_LA_County_November2016.pdf. (Accessed February 3, 2021).

50. Keith RE, Crosson JC, O’Malley AS, Cromp DeA, Taylor EF. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: a rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implementation Sci. (2017) 12:15. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0550-7

51. Lyles CR, Fruchterman J, Youdelman M, Schillinger D. Legal, practical, and ethical considerations for making online patient portals accessible for all. Am J Public Health. (2017) 107(10):1608–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303933

52. Sequist TD. Health information technology and disparities in quality of care. J Gen Intern Med. (2011) 26(10):1084–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1812-8

53. Smith SG, O’Conor R, Aitken W, Curtis LM, Wolf MS, Goel MS. Disparities in registration and use of an online patient portal among older adults: findings from the LitCog cohort. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2015) 22(4):888–95. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv025

54. Arora S, Ford K, Terp S, Abramson T, Ruiz R, Camilon M, et al. Describing the evolution of mobile technology usage for Latino patients and comparing findings to national mHealth estimates. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2016) 23(5):979–83. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv203

55. File T. Digital Divides: A connectivity continuum for the United States. Data from the 2011 Current Population Survey. (2012). Available from: http://paa2013.princeton.edu/papers/130743 (Accessed February 20, 2018).

56. File T, editor. Digital Divides: A Connectivity Continuum for the United States. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America 2013 April 11-13, 2013; New Orleans, LA Social and Economic Statistics Division, U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce.

57. File T. Computer and Internet Use in the United States. Current Population Survery Reports, P20-568. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, 2013.

58. File T, Camille R. Computer and Internet Use in the United States: 2013. American Community Survey Reports, ACS-28. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau (2014).

59. Kontos E, Blake KD, Chou WY, Prestin A. Predictors of eHealth usage: insights on the digital divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012. J Med Internet Res. (2014) 16(7):e172. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3117

60. Laz TH, Berenson AB. Racial and ethnic disparities in internet use for seeking health information among young women. J Health Commun. (2013) 18(2):250–60. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.707292

61. Livingston G. Latinos and digital technology, 2010. Pew Hispanic Center website. Published February 9, 2011. Available from: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2011/02/09/latinos-and-digital-technology-2010/ (Accessed February 20, 2018).

62. Perzynski AT, Roach MJ, Shick S, Callahan B, Gunzler D, Cebul R, et al. Patient portals and broadband internet inequality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2017) 24(5):927–32. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx020

63. Ratanawongsa N, Barton JL, Lyles CR, Wu M, Yelin EH, Martinez D, et al. Computer use, language, and literacy in safety net clinic communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2017) 24(1):106–12. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw062

64. Turner-Lee N, Brian S, Joseph M. . Minorities Mobile Broadband and the Management of Chronic Diseases. Washington, DC: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies (2012). http://jointcenter.org/research/minorities-mobile-broadband-and-management-chronic-diseases (Accessed February 20, 2018).

65. Zickuhr K, Smith A. Digital Differences. Pew Internet and American Life Project. Published April 13, 2012. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/04/13/digital-differences/ (Accessed February 20, 2018).

66. Gonzalez M, Sanders-Jackson A, Emory J. Online health information-seeking behavior and confidence in filling out online forms among latinos: a cross-sectional analysis of the California health interview survey, 2011–2012. J Med Internet Res. (2016) 18(7):e184. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5065

67. Dhanireddy S, Walker J, Reisch L, Oster N, Delbanco T, Elmore JG. The urban underserved: attitudes towards gaining full access to electronic medical records. Health Expect. (2014) 17(5):724–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00799.x

68. Gordon NP, Hornbrook MC. Differences in access to and preferences for using patient portals and other eHealth technologies based on race, ethnicity, and age: a database and survey study of seniors in a large health plan. J Med Internet Res. (2016) 18(3):e50. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5105

69. Roblin DW, Houston TK 2nd, Allison JJ, Joski PJ, Becker ER. Disparities in use of a personal health record in a managed care organization. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2009) 16(5):683–9. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3169

70. Moreno G, Lin EH, Chang E, Johnson RL, Berthoud H, Solomon CC, et al. Disparities in the use of internet and telephone medication refills among linguistically diverse patients. J Gen Intern Med. (2016) 31(3):282–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3500-6

71. Garrido T, Kanter M, Meng D, Turley M, Wang J, Sue V, et al. Race/ethnicity, personal health record access, and quality of care. Am J Manag Care. (2015) 21(2):e103–13. PMID: 25880485.25880485

72. Turner-Lee N, Smedley B, Miller J. Minorities, mobile broadband and the management of chronic diseases. Washington, DC: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies (2012).

73. Sieck CJ, Sheon A, Ancker JS, Castek J, Callahan B, Siefer A. Digital inclusion as a social determinant of health. NPJ Digit Med. (2021) 4(1):52. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00413-8. PMID: 33731887; PMCID: PMC7969595 33731887

74. Katiria Perez G, Cruess D. The impact of familism on physical and mental health among Hispanics in the US. Health Psychol Rev. (2014) 8(1):95–127. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2011.569936

75. Lyles CR, Allen JY, Poole D, Tieu L, Kanter MH, Garrido T. “I want to keep the personal relationship with my doctor”: understanding barriers to portal use among African Americans and latinos. J Med Internet Res. (2016) 18(10):e263. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5910

76. Denson VL, Graves JM. Language assistance services in nonfederally funded safety-net medical clinics in the United States. Health Equity. (2022) 6(1):32–9. doi: 10.1089/heq.2021.0103

77. Livingston G. Latinos and digital technology, 2010. Pew Hispanic Center website. Published February 9, 2011. Available from: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2011/02/09/latinos-and-digital-technology-2010/ (Accessed February 20, 2018).

78. Househ MS, Borycki EM, Rohrer WM, Kushniruk AW. Developing a framework for meaningful use of personal health records (PHRs). Health Policy Techn. (2014) 3(4):272–80. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2014.08.009

79. https://www.careinnovations.org/virtualcare/virtual-care/toolkits-telemedicine-for-health-equity/.

80. Casillas A, Moreno G, Grotts J, Tseng CH, Morales LS. A digital language divide? The relationship between internet medication refills and medication adherence among limited English proficient (LEP) patients. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2018) 5(6):1373–80. doi: 10.1007/s40615-018-0487-9

81. Lyles CR. Capsule commentary on moreno et al., disparities in the use of internet and telephone medication refills among linguistically diverse patients. J Gen Intern Med. (2016) 31(3):322. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3520-2

82. Language Equity is Essential in Outpatient Practice [Internet]. Lean Forward. 2019 [cited 2021 Jan 27]; Available from: https://leanforward.hms.harvard.edu/2019/04/11/language-equity-is-essential-in-outpatient-practice.

83. Messias DKH, Estrada RD. Patterns of communication technology utilization for health information among hispanics in South Carolina: implications for health equity. Health Equity. (2017) 1(1):35–42. doi: 10.1089/heq.2016.0013

Keywords: telehealth, telemedicine, digital divide, digital health disparities, safety net, vulnerable populations, COVID-19, community-partnered participatory research, qualitative research

Citation: Casillas A, Valdovinos C, Wang E, Abhat A, Mendez C, Gutierrez G, Portz J, Brown A and Lyles CR (2022) Perspectives from leadership and frontline staff on telehealth transitions in the Los Angeles safety net during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Front. Digit. Health 4:944860. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2022.944860

Received: 16 May 2022; Accepted: 11 July 2022;

Published: 9 August 2022.

Edited by:

Terika McCall, Yale University, United StatesReviewed by:

Michael Musker, University of South Australia, AustraliaKarthik Adapa, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United States

© 2022 Casillas, Valdovinos, Wang, Abhat, Mendez, Gutierrez, Portz, Brown and Lyles. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alejandra Casillas YWNhc2lsbGFzQG1lZG5ldC51Y2xhLmVkdQ==

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Human Factors and Digital Health, a section of the journal Frontiers in Digital Health

Alejandra Casillas

Alejandra Casillas Cristina Valdovinos2

Cristina Valdovinos2 Griselda Gutierrez

Griselda Gutierrez