94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Digit. Health, 06 May 2022

Sec. Digital Mental Health

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2022.876595

This article is part of the Research TopicDigital Suicide PreventionView all 8 articles

Suicide and suicide-related behaviors are prevalent yet notoriously difficult to predict. Specifically, short-term predictors and correlates of suicide risk remain largely unknown. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) may be used to assess how suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) unfold in real-world contexts. We conducted a systematic literature review of EMA studies in suicide research to assess (1) how EMA has been utilized in the study of STBs (i.e., methodology, findings), and (2) the feasibility, validity and safety of EMA in the study of STBs. We identified 45 articles, detailing 23 studies. Studies mainly focused on examining how known longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation perform within shorter (hourly, daily) time frames. Recent studies have explored the prospects of digital phenotyping of individuals with suicidal ideation. The results indicate that suicidal ideation fluctuates substantially over time (hours, days), and that individuals with higher mean ideation also have more fluctuations. Higher suicidal ideation instability may represent a phenotypic indicator for increased suicide risk. Few studies succeeded in establishing prospective predictors of suicidal ideation beyond prior ideation itself. Some studies show negative affect, hopelessness and burdensomeness to predict increased ideation within-day, and sleep characteristics to impact next-day ideation. The feasibility of EMA is encouraging: agreement to participate in EMA research was moderate to high (median = 77%), and compliance rates similar to those in other clinical samples (median response rate = 70%). More individuals reported suicidal ideation through EMA than traditional (retrospective) self-report measures. Regarding safety, no evidence was found of systematic reactivity of mood or suicidal ideation to repeated assessments of STBs. In conclusion, suicidal ideation can fluctuate substantially over short periods of time, and EMA is a suitable method for capturing these fluctuations. Some specific predictors of subsequent ideation have been identified, but these findings warrant further replication. While repeated EMA assessments do not appear to result in systematic reactivity in STBs, participant burden and safety remains a consideration when studying high-risk populations. Considerations for designing and reporting on EMA studies in suicide research are discussed.

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) refers to data collection methods were momentary information is collected in real life (1). EMA is also known as experience sampling method (ESM) (2) or ambulatory assessment (AA) (3). These three terms emphasize the defining features of this methodology: catching individuals in their natural environments while they go about their daily lives, and probing them about their experiences as they unfold in the moment. Indeed, the most prominent strengths of EMA are its ecological validity and the ability to perform repeated assessments (1, 4). Technological advancements have further increased the feasibility of EMA measures: as opposed to undergoing assessments that are either based on retrospective self-report or performed in non-representative laboratory settings, participants may now provide time- and context-specific data through their smartphones (1, 3, 5).

While paper-and-pen diaries and later handheld computers or personal digital assistants (PDAs) were first used to collect EMA data, many studies now use mobile phone applications specifically designed for EMA purposes (6). These applications function as electronic diaries that may be used to prompt participants to record their mood, cognitions, behavior, context (incl. social interactions) and other experiences, typically either through text entries, event logs or rating scales (6). Such electronic EMA assessments typically use either signal-contingent or event-contingent sampling, prompting participants to fill out assessments either when alerted by the device, or when certain events naturally occur in their daily lives. These methods may also be combined (1, 6, 7). Signal-contingent sampling schedules can further be divided into fixed and (pseudo)randomized schedules. EMA assessments sent out on fixed schedules prompt participants at the same time(s) each day, while randomized schedules send out prompts at random times throughout the day; pseudorandomized schedules divide each 24-h period into blocks, and random prompts are sent out per block. Pseudorandomization offers advantages over full randomization, as it ensures that assessments are sufficiently paced out within the day, but also that participants do not systematically miss prompts due pre-determined commitments like work or school schedules, or learn to anticipate prompts (8).

EMA has been increasingly adopted in the study of psychopathology. This may be a promising approach since insights into the psychological states and behavior patterns in the daily life of the patient can be targeted in therapy (9). Recent reviews have outlined the applicability of EMA in a number of clinical populations, including patients with depression (10, 11) and anxiety disorders (12), eating disorders (13), borderline personality disorder (14), and psychotic disorders (15). These reviews indicate that EMA is an acceptable and feasible data collection method in psychiatric samples as well, and that it may be used to assess a range of experiences from affect (16) to self-harm (17) and substance use (18). Indeed, EMA can hold many advantages over traditional self-report measures for these purposes. Psychiatric disorders, such as depression (19, 20) and schizophrenia (21), are often characterized by memory biases. Retrospective accounts of certain behaviors, such as substance use, are also characteristically unreliable (8). Individuals may also be more willing to disclose sensitive information, such as accounts of drug use or self-harm, when they can do so remotely without face-to-face contact with the researcher (22). Further, EMA is an especially suitable method for assessing symptoms that are dynamic in nature (such as affective instability) (6, 23), which may be time or context dependent, and for which global retrospective measures provide only approximations (1). However, the benefits of EMA should be considered together with its possible limitations, which may include increased burden and time commitment from participants, and potential reactivity to repeated assessments of negative experiences (24).

Meanwhile, EMA remains a relatively underused data collection method in suicide research, although its features make it suitable for the assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) (4, 25, 26). Suicide and suicide-related phenomena [ideation i.e., thoughts or fantasies about one's death (27), attempts] represent a major cause of mortality and disability worldwide (28, 29). Several risk-factors for suicide are known, including psychiatric and demographic variables such as depression, gender and stress (28–30). However, these factors have quite limited clinical use: they are poor predictors of short-term behavior, or are non-modifiable (e.g., gender, past STBs). Their base rate is also much higher than that of suicide, and basing clinical decisions on these risk factors would result in an abundance of false positives (31–33) and many interventions are generic and are not very efficacious (34). Meanwhile, acute warning signs of suicide risk remain less well studied and understood (35). Two recent meta-analyses concluded that there has been no improvement in the prediction of suicide risk in the past fifty years (31, 33). Many have called for a shift of focus towards prospectively predicting STBs in the short term (within days or even hours) (4, 34, 36). Both suicidal ideation and its risk factors can fluctuate substantially over short periods of time (days and hours) (37). Indeed, it has been suggested that (between-day) variability in suicidal ideation may be a better predictor of suicide than its intensity or duration (37, 38).

In summary, the study of STBs needs a new focus and methodology, for which EMA holds promise. Its limited use so far in suicide research may reflect concerns about the potentially adverse effects of repeated probing of suicidal thoughts and urges in at-risk groups. It has been demonstrated that asking individuals about their suicidal thoughts and behaviors does not induce suicidal ideation in asymptomatic individuals, nor does it increase risk in those affected. In fact, it may even serve to lessen ideation and general distress in high-risk individuals (39, 40). Limited evidence exists, however, on the question of whether this also holds for as frequently repeated assessments as with EMA schedules. The validity of EMA measures of STBs is also uncertain. Self-reports of suicidal behavior can be very unstable over time due to erroneous recall (41). Further, only a limited number of items can be used to cover a certain construct in EMA protocols (6)–sometimes only a single item is used [see e.g., (42)].

The aim of this systematic review was to determine: (i) how EMA has been used to operationalize and measure STBs (incl. methodology, aim, findings), and (ii) the feasibility, validity and safety of EMA in research on STBs. We exclude studies on non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) [recently reviewed by (17)] and studies using paper-and-pen diaries, as these data are frequently compromised by retrospective responding (43).

The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (44).

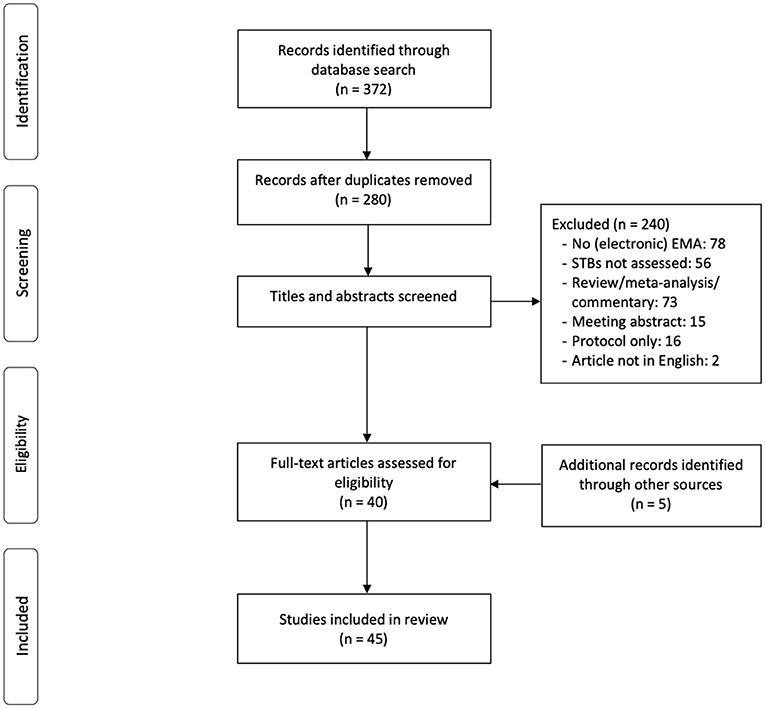

The databases Web of Science (www.webofknowledge.com) and PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) were searched for articles in December 2021, using the search term: “((EMA) OR (“ecological momentary assessment”) OR (ESM) OR (“experience sampling method”) OR (“ambulatory assessment”) OR (“ambulatory monitoring”) OR (“real time monitoring”) OR (“electronic diary”)) AND ((“suicide”) OR (“suicidal”)).” As shown in Figure 1, the search produced 372 results. After excluding duplicate records, 280 remained. Of these, 40 met the inclusion criteria given below. Another 5 articles were identified through alternate sources (i.e., review papers and other articles), resulting in a total of 45 articles for the present review.

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of included studies.

We included articles reporting on (1) studies using electronic EMA (PDAs, mobile phones, smartwatches), and excluded studies using paper-and-pen diaries. We also included studies using web-based survey software (such as Qualtrics, www.qualtrics.com) if mobile phones or other devices were used to alert and direct the participants to the survey. We further only included (2) studies where EMA was used to assess STBs (≥1 item assessing STBs). We excluded studies focusing solely on non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), but included studies where both NSSI and STBs were assessed.

Articles were also excluded if (1) the article was a meta-analysis, (systematic) review, editorial, or commentary, or (2) the article was not written in English.

For each article we recorded the (1) author(s) and publication year, (2) sample characteristics, (3) aim of the study, (4) variable(s) measured through EMA, (5) how STBs were operationalized (i.e., the number and type of EMA items assessing STBs), (6) duration of the EMA assessment period, (7) sampling method (i.e., schedule and number of prompts per day), (8) device and software used, (9) methodological characteristics (incl. acceptance i.e., agreement to participate, attrition, compliance i.e., average response rates, and reactivity), and (10) main findings (as relating to STBs), including any adverse events. When reported, we also recorded any procedures used to ensure participant safety during the EMA assessment period.

In total, 45 articles reporting on 23 studies were included in the review (some studies were reported in more than one article; overlap between samples is indicated where applicable). Of these, 36 articles were reports where EMA was used to measure STBs (Table 1), and nine specifically addressed methodological issues (acceptability, feasibility and validity) of using EMA to measure STBs (Table 2).

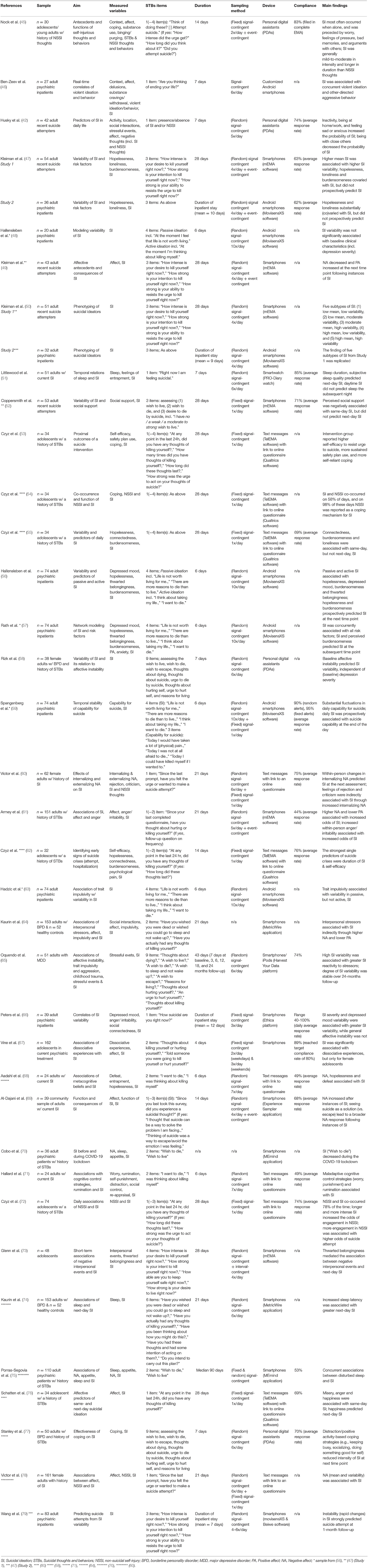

Table 1. Overview of manuscripts reporting on studies using EMA to assess suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs).

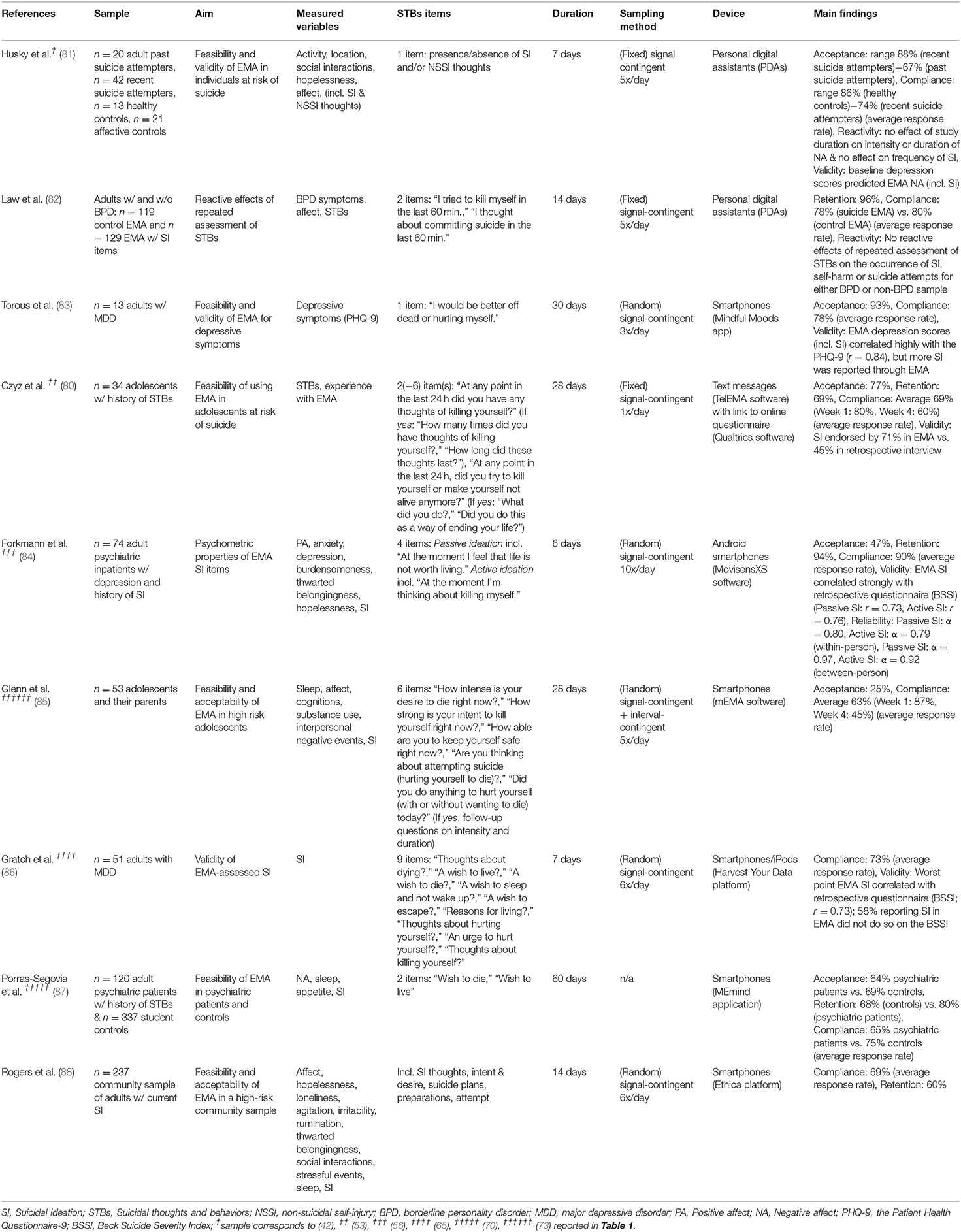

Table 2. Overview of manuscripts assessing the feasibility and validity of using EMA to assess suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs).

Sample sizes ranged from 13 to 457 (median = 53, n = 23). Most studies (78%, n = 18) were conducted in adult, and less frequently in adolescent samples [22%, n = 5; (45, 67, 72, 80, 85)]. Participants were typically recruited from high-risk populations, such as psychiatric inpatients or those recently discharged from the hospital. Most frequent primary co-morbid diagnoses were depressive disorders (83, 84, 86) and borderline personality disorder [BPD (58, 64, 82)]; however, inclusion was typically based on (recent) history of self-reported STBs to ensure sufficient number of observations of STBs during the assessment period.

The duration of EMA monitoring ranged from 4 to 60 days (median = 14, n = 23). The number of (scheduled) EMA prompts per day ranged from 1 to 11 (median = 5, n = 21). All studies used some form of signal-contingent sampling: (pseudo)random sampling schedules were most frequently used [57%, n = 13 (42, 47, 51, 58, 61, 65, 69, 71, 79, 83, 85, 86, 88)], followed by fixed sampling [26%, n = 6 (45, 66, 67, 72, 80, 82)], and protocols that combined both fixed and (pseudo)random sampling [13%, n = 3 (47, 56, 60)]. Fixed schedules were almost exclusively used in studies with once-daily prompts (as well as three older studies with PDAs (45, 81, 82)), whereas pseudo-random schedules were typically used for repeated within-day assessments. Approximately one fourth (26%; n = 6) of studies supplemented signal-contingent sampling with event-contingent sampling [i.e., participants were encouraged to self-initiate additional entries when experiencing STBs (45, 47, 61, 69, 85)], but none of the studies used event-contingent sampling alone. Studies frequently (57%, n = 13; (47, 51, 58, 60, 61, 69, 71, 79–81, 85, 86)) reported that participants could provide input about their daily schedules (incl. sleep and wake times), allowing EMA prompt windows to be adjusted for each participant, and a minimum time window (30–60 min) between prompts was established with (pseudo)random schedules to achieve better temporal coverage.

While all studies included EMA items on suicidal ideation, four studies (18%) also assessed the occurrence of suicide attempts via EMA (45, 80, 82, 88) (see Tables 1, 2 for full list of measured variables and SI item descriptions). The number of EMA items on STBs ranged from 1 to 9 (median = 2, n = 22). The items were typically rated on a 5-point Likert-scale; seven (32%) studies used binary items, or a combination of an initial binary item on the presence of STBs, followed by ratings on frequency, intensity and/or duration (18%, n = 4). Items were often based on established self-report questionnaires or structured interviews, such as the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSSI) (89) or the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (90), and rephrased to reflect the time period of the EMA or otherwise adapted for the purposes of the study.

Several studies used gate questions to limit the number of questions presented pertaining to STBs. Such gate questions either first inquired about the presence of (any) negative thoughts prior to direct questioning of suicidal ideation [see e.g., (81)], or limited follow-up questions on the intensity, frequency and/or duration of ideation only to those instances where suicidal ideation was first endorsed [see e.g., (45, 55, 61, 85)]. Two studies used a turn-over system where a subset of questions was randomly presented at a certain time point to limit repetition (83, 87). Studies were heterogenous in their operationalization of STBs, and no clear delineation emerged over time on preferred methodologies or use of specific EMA items.

The most frequently measured predictor variables included contextual factors (incl. location, activity, social company), affect, and constructs from the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide [IPTS: hopelessness, burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (91)]. Protective factors, such as coping and social support, were less frequently assessed.

In adolescent samples, suicidal ideation was reported by 34–82% of the sample during EMA (median = 71%, n = 3), and overall, 2–39% of observations had suicidal ideation ratings >0 (median: 25% n = 3). These thoughts occurred once a week on average, and typically lasted 1 to 30 min [based on a binary measure of ideation (45)]. In adult samples, ideation was reported by 26–100% of the participants (median = 97%, n = 7), and 1–82% of observations had suicidal ideation ratings > 0 (median: 22% n = 7). While the majority of studies recruited participants with heightened risk profiles (such as those recently discharged after a suicide attempt), prevalence rates in two community-based samples with current self-reported ideation were comparable to the pooled prevalence rates (86–100% participants and 20–22% of all entries indicated suicidal ideation (69, 88). When examined separately, higher levels of passive (m = 4.54, sd = 2.25, range 2–10) than active (m = 3.18, sd = 1.50, range 2–10) suicidal ideation was reported (56).

Contextual factors of suicidal thoughts among adolescents included being alone, experiencing arguments/conflict or recalling negative memories (45). Among adolescents with a history of NSSI, suicidal ideation frequently co-occurred with NSSI (72). Among adults, being alone, at home or at work, and inactivity increased the probability of suicidal ideation, while being with family and friends or engaged in leisure activities decreased probability of ideation (42). Although negative daily life events were generally not associated with suicidal ideation, negative interpersonal events increased the probability of ideation (42, 64), whereas perceived social support decreased its probability (52). Affective precipitants (incl. negative affect, feelings of pressure, anger/irritability) were associated with increased occurrence of ideation (45, 61).

Most individuals experienced substantial variability in suicidal ideation both between- (55) and within-days (47, 56, 58). Within-day, approximately one third of ratings differed from the previous one by at least one (within-person) standard deviation, illustrating both sharp increases and decreases in ideation in a time frame of hours [4–8 h (47)]. Those with higher mean ideation (per person, across EMA period) experienced more variability (47, 65, 66). Risk factors (negative affect, hopelessness, loneliness, burdensomeness, connectedness, thwarted belongingness) occurred with similar variability, and were concurrently associated with suicidal ideation (47, 55, 56, 68, 78). General affective instability (i.e., tendency to experience frequent, sudden changes in mood) was associated with suicidal ideation variability among female BPD patients (58), and inpatient individuals diagnosed with MDD or bipolar disorder (66). Generally, baseline clinical characteristics, such as severity of depressive symptoms [retrospective self-report of symptoms over the past 2 weeks (48)] were not differentially associated with suicidal ideation variability. The test-retest reliability of EMA-assessed within-person suicidal ideation variability (as estimated by the Root Mean Square of the Successive Differences, RMSSD) was high across 24 months (65). Suicidal ideation variability (here operationalized as the individual's likelihood of experiencing extreme changes in suicidal ideation from one assessment point to the next) was also predictive of the occurrence of a suicide attempt at 1-month follow-up post-discharge, based on a pilot study of 83 adults hospitalized for a suicidal crisis (79).

Most reports failed to establish independent temporal predictors of suicidal ideation severity: of twelve articles fitting temporal prediction models (47, 51, 52, 55–57, 60, 73, 74, 76, 77), four failed to establish significant predictors after accounting for ideation at the previous time point (47, 52, 55), and five did not control for prior ideation (51, 60, 73, 74, 76). Across studies, prior suicidal ideation therefore remained the strongest (or only) predictor of subsequent ideation (i.e., suicidal ideation at T significantly predicting ideation at T+1). Regarding other predictors, the most consistent evidence was found for momentary negative affect, hopelessness and burdensomeness. These variables predicted increased momentary suicidal ideation within-day (47, 56, 57, 60). One study indicated that active coping reduced the intensity of ideation at the subsequent assessment 2 h later (77). Between days, short sleep duration (both objective and subjective), poor subjective sleep quality and increased sleep latency (i.e., time to fall asleep) predicted (mean) next-day suicidal ideation (51, 74). Negative interpersonal events were also associated with increased next-day suicidal ideation (73). The probability of finding influential predictors was further lower with increasing intervals. Studies examining day-to-day rather than within-day changes in suicidal ideation were less likely to report positive findings (55, 80). This may be due to reduced temporal granularity of data due to aggregate daily ratings.

In order to examine the feasibility of using EMA in suicide research we reviewed reports of acceptance and compliance across studies, as well as detail previously used measures to ensure participant safety during EMA periods. Reports of adverse events are further examined to estimate the safety of repeated assessments of STBs.

Acceptance rates ranged between 25 and 93% (median = 77%, n = 10). Comparing three subgroups, acceptance was highest among outpatients with a recent history of a suicide attempt (88%), as compared to clinical controls (i.e., 68% outpatients without a history of suicide attempts), and healthy controls [77%; (81)]. Acceptance was lower in inpatient samples (47–77%, median = 50%, n = 3).

Compliance ranged from 44 to 90% (median 70%, n = 19). Compliance in clinical subgroups (range 74–82%) was lower than that in a non-clinical control group (86%) (81). A similar pattern emerged when comparing psychiatric patients (65%) and student controls (75%) (87). Compliance rates were not significantly related to suicide history or current depressive symptom or suicidal ideation severity (65, 66, 71, 85, 88). Compliance rates declined over time (i.e., participants exhibited fatigue effects) (80, 84, 85). In a 4-week study, compliance decreased by twenty percentage points from the first to the fourth week of EMA assessment (80). However, this effect was not replicated by all: rather than declining in a linear manner, one study reported that compliance rates did not decrease over time (66), fluctuated before stabilizing after ~2 weeks (83), or that compliance increased over time during a 1-week EMA study (81). Compliance rates did not differ between studies employing once-daily (range 69–74%, median = 72%, n = 2), or multiple daily assessments (range 44–90%, median = 70%, n = 17). Response rates were higher in the afternoons (83) and on weekend days (84). Practice effects were also observed by participant's response times decreasing over time (81).

Attrition was low (4–40%, median = 6%, n = 10). In contrast to findings of lower compliance rates among psychiatric patients, dropout was lower among clinical cases than controls (87). The highest attrition rate (40%) was reported in an anonymous online study with no personal contact (88).

EMA measures were associated with traditional self-report and interview measures. Baseline depression severity [Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, HAMD (92)] predicted EMA-assessed sad mood and negative thoughts (incl. suicidal ideation) (81). The correlation between depression scores (incl. a suicidal ideation item) derived from the traditionally administered Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9 (93)] and EMA administered PHQ-9 was r = 0.84 (83). EMA-measured momentary suicidal ideation correlated highly1 with the BSSI [passive ideation: r = 0.73, active ideation: r = 0.76 (67)]. Correlations were higher for items assessing active (“Wish to die” r = 0.76) rather than passive ideation (“Wish to live” r = 0.37) (86). A one-item EMA measure (“How suicidal are you right now?”) correlated highly with the BSSI (r = 0.71) and moderately with the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI (95)] [r = 0.41 (71)]. Variability in momentary SI correlated moderately with the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire - Revised [SBQ-R (96)] (r = 0.41), the BSSI (r = 0.49), and the Capability for Suicide Questionnaire [GCSQ (97)] (r = 0.30) (63).

More severe depressive symptoms were reported through EMA than with a traditional retrospective questionnaire, and EMA reports of suicidal ideation were notably higher than questionnaire scores for 69% of the participants (83). In an adolescent sample, suicidal ideation was reported in EMA by 71% of the participants, and in 45% of the interviews post-EMA (80). Among adults, 58% of participant reporting SI in EMA did not do so in an interview post-EMA (86).

A feasibility study in adult suicide attempters (recent or past attempt history), clinical controls (i.e., depressed patients without suicide attempt history), and healthy controls, found no effects of study duration on the intensity of negative affect or frequency of suicidal ideation, indicating no symptom worsening with repeated prompts (81). However, there was a decrease in positive affect among recent and past suicide attempters, and a decrease in hopelessness among recent suicide attempters with increasing study duration (across seven days) (81). In another study comparing two 14-day EMA protocols (one with items on suicidal ideation, and a control EMA protocol), there were no differences in the occurrence of suicidal ideation, self-harm or suicide attempts between the two conditions for either clinical (patients with BPD) or non-clinical controls based on weekly retrospective measures (82). In a sample of adolescents assessed after 1-month of EMA, most participants reported that they generally felt no change in mood after filling out EMA (69%) or that they felt better (28%); one participant reported that they had worse mood after completing EMA (80). The clinicians of another adolescent sample reported the study, on average, to have had “neutral” to “somewhat positive” impact on their patients [incl. increased awareness into one's condition (72)]. Following a 6-day EMA assessment with 10 prompts per day, 16% of a sample of depressed inpatients reported that they had felt stressed and/or burdened by the assessments (84), but no further details were provided. Among 237 high risk adults from the community, 9% reported they had experienced the EMA as “occasionally' distressing,”' “emotionally taxing,” and, “triggering bad thoughts,” (p. 6) in comparison to 3% who reported a decrease in the frequency of and urge to act on suicidal thoughts due to study participation (88). In general, participants reported their experiences overall as neutral-to-positive but time consuming (or burdensome), and that they would be open to participating in similar research in the future (80, 84, 85).

Ten studies reported whether any suicide attempts occurred during the study period: in four studies no such events occurred (45, 47, 84). Three studies followed adolescents who were recently discharged from inpatient treatment after a suicide attempt or severe ideation. In 28 days, the incidence of suicide attempts was 6% (55), 8% (72), and 9% (85). In a sample of 50 adult BPD patients, 10% attempted suicide over 7 days (77), and in a study of 248 adults with and without BPD, approximately 5% of participants made a suicide attempt during the entire study period (including a 6-month follow-up) (82). In a community sample of 237 adults with current suicidal ideation, 3% attempted suicide during the 2-week study (88). In comparison, in similar high-risk populations (with last-year suicidal ideation or attempt) the estimated 1-year prevalence of suicide attempts is between 13 and 20% (98, 99), with the risk being higher for those with recent attempt history (99). Risk is further heightened among those with an earlier age of occurrence of first attempt, as well as those with borderline personality disorder (features) (100). No suicide mortality was reported in any of the reviewed studies.

Eight studies reported implementing some type of safety measures in their EMA protocols. Four studies implemented automatic messages sent out by the EMA device. In one study each EMA assessment began with a message reminding the participant to contact a mental health professional or emergency personnel in case of a crisis (82), and three others used similar messages that were presented if the participant's responses indicated momentary suicidal ideation (42, 61, 80). Three studies employed ongoing monitoring of the participant's responses (45, 72, 80). In a study using PDAs, participants were instructed to upload their data on a server each night for evaluation, and research personnel phoned participants in case responses indicated imminent risk or if no data had been uploaded for 72 h (45). Another study reported twice-daily (manual) checks on the participants entries; 32% of the adolescent participants were contacted for a risk assessment during the 4-week study (72). In another study, the EMA software was programmed to send out automatic email alerts to the study's on-call clinician if the participant endorsed a suicide attempt or severe ideation with suicidal intent and/or a plan, in which case the clinician made contact with the participant; <1% of the responses recorded met this threshold and required contact by the study personnel (80). Two studies required that each participant had an individualized safety plans in place established by their treating physician (61, 85), and another study instructed participants on how to make one prior to participation (88). In two studies, research personnel conducted an unspecified suicide risk assessment halfway through the 2-week EMA period (69), and in the other study participants completed the CSSRS at baseline and at follow-up and test assistants referred acute cases to the emergency department (70). Of note is that while only 36 % (n = 8) of studies reported on safety procedures, 80% (n = 4) of studies in adolescent samples had safety measures in place. None of the studies conducted in inpatient settings employed additional safety measures.

Among the 23 reviewed studies, substantial variability existed in the operationalization of STBs. This ranged from single-item binary measures of general self-harm ideation (42) to multi-item batteries assessing the intensity, frequency and duration of specific suicidal thoughts [see e.g., (55, 65)]. General guidelines for EMA research emphasize that items should be formulated in a way that allows for the assessment of the natural fluctuations in momentary experience, while limiting potential floor and ceiling effects (101). Binary items generally lack these characteristics. Single-item measures may also not be sufficient in capturing the wide spectrum of ideation, such as distinguishing passive from active ideation and intent. Further, suicidal ideation alone is not the only permissive characteristic preceding suicidal acts; a transition from ideation to attempt requires acquired capability, that is, additional cognitive and behavioral processes, such as decreased fear of death and increased pain tolerance (30). These latter characteristics can also fluctuate substantially from day to day (59).

The strength of EMA for suicide research remains in its ability to capture more variable aspects of suicide risk that may be difficult to grasp by traditional retrospective questionnaires. From our review we conclude that suicidal ideation exhibits substantial variability over time, often increasing or decreasing sharply within only a few hours in an individual [see e.g., (47)]. Witte and colleagues (37, 38) have proposed that such variability in suicidal ideation may provide a more reliable index of suicide risk than the severity or duration of ideation alone. This notion is tentatively supported by findings of higher suicidal ideation variability among patients with more severe suicidal ideation (47, 65, 66), as well as those with a prior suicide attempt history (66), and by higher EMA suicidal ideation variability predicting attempts at 1-month follow-up (79). In line with these findings, a previous review of EMA studies on NSSI also identified affective variability as a risk factor for engaging in self-harm behavior (17). While these preliminary findings warrant further replication, they indicate that suicidal ideation variability may represent a promising marker for suicide risk.

In addition to suicidal ideation itself, a number of its risk factors (incl. negative affect, hopelessness, loneliness, burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness) were also found to exhibit similar variability patterns and associate with momentary ideation. However, fewer studies so far have succeeded in establishing prospective predictors of suicidal ideation. A similar pattern is observable in the EMA literature on NSSI, where most studies have elucidated on the immediate context, rather than precipitants, of self-harm behavior (17). Kaurin et al. (64) outlined the ongoing discourse in EMA literature over the relative value of time-lagged vs. concurrent (or contemporaneous) modeling approaches. While longitudinal modeling is often regarded as superior in traditional research designs, contemporaneous associations derived from EMA data reflect associations beyond simple co-occurrences; rather, they reflect systematic covariances between variables, and can signal the presence of temporal associations occurring very close in time. Hence, these findings indicate that a number of known longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation are also involved in its imminent emergence over shorter time frames. Considering emerging evidence that suicidal ideation variability may represent an important marker for acute risk, increased understanding of the factors underlying these fluctuations is of great importance.

While our review supports the general acceptability of EMA in suicide research, the burden of EMA measures may be less tolerable for those currently experiencing very severe symptoms, analog to findings in individuals with depressive disorders (102). Meanwhile, compliance was good and not substantially lower than in other clinical (103) or non-clinical populations [see e.g., (104)]. This is in line with reports that EMA compliance is not significantly influenced by demographic or clinical characteristics (105).

Regardless, maintaining compliance with EMA remains a challenge, especially when assessment periods grow long, as compliance decreases over time with each subsequent week of EMA [see e.g., (80, 85)]. Meanwhile, compliance rates did not appear lower in studies using multiple measures per day (vs. once-daily ratings). It has also previously been reported that more frequent assessments may not reduce compliance (106), or may even increase compliance (107), as long as questionnaires are kept brief (108). Shorter time intervals between prompts can also increase compliance (109). However, overly lengthy measures can induce fatigue and reduce compliance, as well as impact data quality due to increased careless responding or skipping questions (108, 110). Based on our review, researchers may be advised to prioritize more frequent, but brief assessments over short time periods to establish higher compliance; future research should aim to more systematically examine how increasing the number of daily prompts affects compliance rates, in order to establish optimal sampling schedules that balance temporal coverage with participant burden. Researchers may also consider implementing incentives for compliance. Many of the reviewed studies used monetary rewards for increasing or sustaining compliance [see e.g., (85, 88)]. However, monetary incentives are reported as relatively unimpactful in increasing compliance, based on a review of 481 EMA studies (111). Alternative incentives, such as personalized feedback based on EMA data, may be regarded as more valuable (112).

In line with the observation that all of the reviewed studies used signal-contingent sampling (either alone or in conjunction with event-contingent sampling), we may also recommend this approach for future research, as signal-contingent sampling more optimally allows for the examination of the variability in experience of STBs. Finally, further research is needed to generalize these recommendations to other age groups (such as the elderly) and non-Western societies. As the reviewed studies exclusively focused on adolescents and adults (who may already be more accustomed to using technology to track their lives), it remains to be established whether such electronic symptom self-monitoring would be perceived as equally acceptable, and helpful, by older populations.

While EMA measures showed high correlations with traditional self-report, more individuals reported suicidal ideation through EMA, and more severe instances of ideation were detected through EMA than retrospective measures. We further found that EMA reports of active suicidal ideation were more highly correlated with retrospective measures than those of passive ideation (86). It is tempting to speculate that EMA has increased sensitivity in detecting momentary, fleeting, and/or passive instances of ideation. However, the possibility that part of this increased reporting is due to reactivity to the EMA questions (i.e., symptom increases due to enhanced focus on them) cannot be disregarded (24, 113), although the current evidence does not support such assessment reactivity (see below).

Our review did not uncover systematic (negative) mood reactivity to EMA, and importantly, there was no evidence of reactivity on STBs specifically (81, 82). These findings are in line with reports of no symptom reactivity in other patient populations, such as those with chronic pain (114) and mood disorders (81). Some behaviors, like alcohol use among substance dependent patients, may be more subject to reactive effects than cognitive or affective symptoms (103). However, these conclusions are tentative at best due to the low number of studies directly assessing reactivity, and the general lack of control groups across studies. Further, available studies were seriously limited in their assessment and reporting of adverse events (suicide attempts, mortality) occurring during the study period. Future research should more transparently examine and describe these events if, and when, they occur.

A defining strength of smartphone-based EMA for suicide research is that it enables the real-time monitoring of participant's responses. However, it remains to be determined how such risk detection can be done with optimal sensitivity and specificity. Changes in symptoms over time, especially drastic changes over short periods of time (within days, hours), may provide a better indication of risk than absolute ratings at any single time point (35). Further, participants may not always provide accurate reports of their experiences for fear of intervention, as many people planning suicide explicitly deny such intentions (115). EMA safety protocols should consequently also involve contact with participants lost to attrition, and additional contact should be made not only when participants indicate severe symptomatology, but also when EMA prompts are systematically missed [as also previously done by e.g., (45)].

Across the reviewed studies, there was considerable heterogeneity in study characteristics and their reporting thereof. This, together with the diversity in aims and samples across studies, prevented us from conducting meta-analyses. Little rationale was provided for the selection of the EMA items used (or if pilots were run to establish the item set for the population under study) with the exception of questions adapted from established self-report questionnaires. However, these questions may not always optimally translate to EMA, as they can lack sufficient sensitivity to variability, especially over shorted time frames. Notably, three (14%) studies did not provide EMA item descriptions, two (9%) did not report sampling frequency, and three (14%) did not report sampling technique (i.e., fixed or random). Further, there was insufficient reporting of other study characteristics: 12 (55%) studies did not report acceptability, three (14%) did not report any index of compliance (with further inconsistencies in how compliance was defined), 14 (63%) did not report on attrition, 12 (55%) did not report adverse events, and 11 (50%) did not report whether any safety measures were implemented. Additional characteristics that may impact data quality and inference, such as amount and patterns of missing data, and information on average time intervals between prompts, as well as delay from alert to response, were rarely reported. A recent review of EMA of NSSI noted similar study heterogeneity and lack of reporting on compliance (17). Reviewers evaluating EMA studies for publication should require these to be reported. Finally, how to adequately measure EMA item reliability and validity remains to be established (although first initiatives have started, such as the Experience Sampling Method (ESM) Item Repository (https://osf.io/kg376/). Correlations with retrospective measures, or moment-to-moment reliability statistics may not provide adequate indications of good psychometric fit, as EMA ratings are expected to vary over time rather than stay constant.

Based on the reviewed studies, in Table 3 we provide an overview of considerations for designing and reporting on EMA studies in suicide research. Directions for future research are discussed further below.

While only one of the reviewed studies employed EMA to assess the effectiveness of an intervention (53), EMA also has broad potential in applicability in clinical practice (24). Beyond EMA interventions (116, 117), EMA assessments in themselves may serve a therapeutic purpose: feedback from participants indicates that EMA made them more reflective, introspective, and mindful of their experiences [see e.g., (88)]. Further, for patients experiencing (persistent) suicidal ideation, demonstrating that ideation is variable, and hence malleable, may provide relief. In accordance with the finding that suicidal ideation variability may serve as a potential marker for increased suicide risk, this characteristic of ideation may be an especially valuable target for EMA monitoring and/or interventions in clinical practice. First applications of using EMA in clinical practice to monitor and manage symptoms are already underway (87). The extensive nature of EMA data also allows for more opportunities for single-case data analysis that may be used to examine individual symptom profiles or identify person-specific triggers (118)–an important goal in the treatment of the very heterogeneous group of patients experiencing STBs (119). However, despite these considerable inter-individual differences, most studies reviewed here solely examined group-level associations, while in clinical practice, the focus is on individual patients (120). Hence, the precise utility of this methodology in clinical practice in relation to STBs remains to be established.

The prospect of digital phenotyping of suicidal ideators (such as identifying those with high/low variability) based on EMA data has been discussed by many [see e.g., (121, 122)], but so far implemented by few (50, 57, 70). EMA data has revealed notable inter-individual differences in suicide symptom profiles (57), highlighting the importance of identifying meaningful subtypes of suicidal ideators that could improve risk assessments and choice of treatment targeting specific symptom profiles. However, the network theory is subject to certain pitfalls that still need to be solved before it can be implemented in clinical practice (24, 123). Next steps in EMA research may also involve intensive longitudinal assessments over longer time periods (i.e., months) in order to more reliably establish such phenotypes. Further, determining the value of such phenotyping would require additional follow-up assessments connecting these symptom profiles to overt outcomes (i.e., suicide attempt, mortality) over time.

Currently, sociodemographic and clinical risk-factors, such as a current mental health diagnosis or previous attempt history, are considered the best predictors of future suicidal behavior–“the best” in this instance indicating the best of the worst, with currently established longitudinal risk factors being no better than chance at differentiating between those at high vs. low risk (33). More recently, real-time methodologies have identified new potential targets for risk-detection, namely rapid changes in momentary affect, interpersonal experiences, and sleep (124). However, these observations still warrant replication. The use of EMA in suicide research has grown rapidly in the past years, and review of the literature suggests that the fluctuating nature of suicidal ideation makes it an especially suited target for EMA, which may provide unique insights into the temporal correlates and imminent warning signs of increased suicide risk. Retrospective reports can be unreliable, especially when individuals are asked to recall fleeting or highly variable experiences (61), but EMA may have increased sensitivity in detecting these momentary experiences. Meanwhile, it has been proposed that identifying instability in suicidal ideation offers promise in improving the detection of those most at risk of suicide (37, 38), and attempts have been made to create new categorizations of suicidal ideators based on real-time data (50). Such risk profiling may hence represent next steps not only in EMA research, but in the improved treatment of patients with suicidal ideation.

LK and NA conceptualized the article. LK conducted the initial literature search and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NA checked the literature search and provided feedback. NA, WvdD, and HR contributed to subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Funding for this study was provided by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (N.W.O) Research Talent Grant 406.18.521. N.W.O. had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Interpretation of correlation coefficients based on r = 0.50 indicating large, r = 0.30 medium, and r = 0.10 small correlations (94).

1. Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2008) 4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415

2. Larson R, Csikszentmihalyi M. The Experience Sampling Method. In: Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands (2014). doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9088-8_2

3. Trull TJ, Ebner-Priemer U. The role of ambulatory assessment in psychological science. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. (2014) 23:466–70. doi: 10.1177/0963721414550706

4. Davidson CL, Anestis MD, Gutierrez PM. Ecological momentary assessment is a neglected methodology in suicidology. Arch Suicide Res. (2017) 21:1–11. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1004482

5. Kaplan RM, Stone AA. Bringing the laboratory and clinic to the community: mobile technologies for health promotion and disease preventiona. Ann Rev Psychol. (2013) 64:471–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143736

6. Myin-Germeys I, Kasanova Z, Vaessen T, Vachon H, Kirtley O, Viechtbauer W, et al. Experience sampling methodology in mental health research: new insights and technical developments. World Psychiatry. (2018) 17:123–32. doi: 10.1002/wps.20513

7. Janssens KAM, Bos EH, Rosmalen JGM, Wichers MC, Riese H. A qualitative approach to guide choices for designing a diary study. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2018) 18:140. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0579-6

8. Shiffman S. How many cigarettes did you smoke? Assessing cigarette consumption by global report, time-line follow-back, and ecological momentary assessment. Health Psychol. (2009) 28:519–26. doi: 10.1037/a0015197

9. Riese H, Wichers M. Comment on: eronen MI (2019). the levels problem in psychopathology. Psychological Medicine. (2021) 52:525–6. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003623

10. Bos FM, Snippe E, Bruggeman R, Wichers M, van der Krieke L. Insights of patients and clinicians on the promise of the experience sampling method for psychiatric care. Psychiatr Serv. (2019) 70:983–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900050

11. Colombo D, Fernández-Álvarez J, Patané A, Semonella M, Kwiatkowska M, García-Palacios A, et al. Current state and future directions of technology-based ecological momentary assessment and intervention for major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:465. doi: 10.3390/jcm8040465

12. Walz LC, Nauta MH, Aan het Rot M. Experience sampling and ecological momentary assessment for studying the daily lives of patients with anxiety disorders: a systematic review. J Anxiety Disord. (2014) 28:925–37. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.022

13. Smith KE, Mason TB, Juarascio A, Schaefer LM, Crosby RD, Engel SG, et al. Moving beyond self-report data collection in the natural environment: a review of the past and future directions for ambulatory assessment in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. (2019) 52:1157–75. doi: 10.1002/eat.23124

14. Santangelo P, Bohus M, Ebner-Priemer UW. Ecological momentary assessment in borderline personality disorder: a review of recent findings and methodological challenges. J Pers Disord. (2014) 28:555–76. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2012_26_067

15. Bell IH, Lim MH, Rossell SL, Thomas N. Ecological momentary assessment and intervention in the treatment of psychotic disorders: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. (2017) 68:1172–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600523

16. Ebner-Priemer UW, Trull TJ. Ambulatory assessment: an innovative and promising approach for clinical psychology. Eur Psychol. (2009) 14:109–19. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.14.2.109

17. Rodríguez-Blanco L, Carballo JJ, Baca-García E. Use of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI): a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 263:212–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.051

18. Serre F, Fatseas M, Swendsen J, Auriacombe M. Ecological momentary assessment in the investigation of craving and substance use in daily life: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2015) 148:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.024

19. Dalgleish T, Watts FN. Biases of attention and memory in disorders of anxiety and depression. Clin Psychol Rev. (1990) 10:589–604. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(90)90098-U

20. Williams JMG, Barnhofer T, Crane C, Hermans D, Raes F, Watkins E, et al. Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychol Bull. (2007) 133:122–48. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122

21. Forbes NF, Carrick LA, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Working memory in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. (2009) 39:889–905. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004558

22. Gnambs T, Kaspar K. Disclosure of sensitive behaviors across self-administered survey modes: a meta-analysis. Behav Res Methods. (2014) 47:1237–59. doi: 10.3758/s13428-014-0533-4

23. Trull TJ, Lane SP, Koval P, Ebner-Priemer UW. Affective dynamics in psychopathology. Emot Rev. (2015) 7:355–61. doi: 10.1177/1754073915590617

24. Bos FM. Ecological Momentary Assessment as a Clinical Tool in Psychiatry: Promises, Pitfalls, and Possibilities [Doctoral Dissertation]. University of Groningen (2021).

25. de Beurs D, Kirtley O, Kerkhof A, Portzky G, O'Connor RC. The role of mobile phone technology in understanding and preventing suicidal behavior. Crisis. (2015) 36:79–82. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000316

26. Nock MK. Recent and needed advances in the understanding, prediction, and prevention of suicidal behavior. Depress Anxiety. (2016) 33:460–3. doi: 10.1002/da.22528

27. Ringel E. The presuicidal syndrome. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (1976) 6:131–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1976.tb00328.x

28. Borges G, Nock MK, Abad JMH, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Alonso J, et al. Twelve-month prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts in the world health organization world mental health surveys. J Clin Psychiatry. (2010) 71:1617–28. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04967blu

29. Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. (2008) 30:133–54. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002

30. van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. (2010) 117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697

31. Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. (2017) 143:187–232. doi: 10.1037/bul0000084

32. Large M, Ryan C, Nielssen O. The validity and utility of risk assessment for inpatient suicide. Australasian Psychiatry. (2011) 19:507–12. doi: 10.3109/10398562.2011.610505

33. Large M, Kaneson M, Myles N, Myles H, Gunaratne P, Ryan C. Meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies of suicide risk assessment among psychiatric patients: heterogeneity in results and lack of improvement over time. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0156322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156322

34. Chesin M, Stanley B. Risk assessment and psychosocial interventions for suicidal patients. Bipolar Disord. (2013) 15:584–93. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12092

35. Rudd MD, Berman AL, Joiner TE, Nock MK, Silverman MM, Mandrusiak M, et al. Warning signs for suicide: theory, research, and clinical applications. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2006) 36:255–62. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.255

36. Glenn CR, Nock MK. Improving the short-term prediction of suicidal behavior. Am J Prev Med. (2014) 47:S176–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.004

37. Witte TK, Fitzpatrick KK, Warren KL, Schatschneider C, Schmidt NB. Naturalistic evaluation of suicidal ideation: variability and relation to attempt status. Behav Res Ther. (2006) 44:1029–40. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.004

38. Witte TK, Fitzpatrick KK, Joiner TE, Schmidt NB. Variability in suicidal ideation: a better predictor of suicide attempts than intensity or duration of ideation? J Affect Disord. (2005) 88:131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.05.019

39. Smith P, Poindexter E, Cukrowicz K. The effect of participating in suicide research: does participating in a research protocol on suicide and psychiatric symptoms increase suicide ideation and attempts? Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2010) 40:535–43. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.6.535

40. Gould MS, Marrocco FA, Kleinman M, Thomas JG, Mostkoff K, Cote J, et al. Evaluating iatrogenic risk of youth suicide screening programs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. (2005) 293:1635–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1635

41. Eikelenboom M, Smit JH, Beekman ATF, Kerkhof AJFM, Penninx BWJH. Reporting suicide attempts: sonsistency and its determinants in a large mental health study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2014) 23:257–66. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1423

42. Husky M, Swendsen J, Ionita A, Jaussent I, Genty C, Courtet P. Predictors of daily life suicidal ideation in adults recently discharged after a serious suicide attempt: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 256:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.035

43. Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Hufford MR. Patient compliance with paper and electronic diaries. Control Clin Trials. (2003) 24:182–99. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(02)00320-3

44. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. (2009) 339:2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

45. Nock MK, Pristein MJ, Sterba SK. Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: a real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. J Abnorm Psychol. (2009) 118:816–27. doi: 10.1037/a0016948

46. Ben-Zeev D, Scherer EA, Brian RM, Mistler LA, Campbell AT, Wang R. Use of multimodal technology to identify digital correlates of violence among inpatients with serious mental illness: a pilot study. Psychiatr Serv. (2017) 68:1088–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700077

47. Kleiman EM, Turner BJ, Fedor S, Baele EE, Huffman JC, Nock MK. Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. J Abnorm Psychol. (2017) 126:726–38. doi: 10.1037/abn0000273

48. Hallensleben N, Spangenberg L, Forkmann T, Rath D, Hegerl U, Kersting A, et al. Investigating the dynamics of suicidal ideation: preliminary findings from a study using ecological momentary assessments in psychiatric inpatients. Crisis. (2018) 39:65–9. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000464

49. Kleiman EM, Coppersmith DDL, Millner AJ, Franz PJ, Fox KR, Nock MK. Are suicidal thoughts reinforcing? a preliminary real-time monitoring study on the potential affect regulation function of suicidal thinking. J Affect Disord. (2018) 232:122–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.033

50. Kleiman EM, Turner BJ, Fedor S, Beale EE, Picard RW, Huffman JC, et al. Digital phenotyping of suicidal thoughts. Depress Anxiety. (2018) 35:601–8. doi: 10.1002/da.22730

51. Littlewood DL, Kyle SD, Carter LA, Peters S, Pratt D, Gooding P. Short sleep duration and poor sleep quality predict next-day suicidal ideation: an ecological momentary assessment study. Psychol Med. (2019) 49:403–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001009

52. Coppersmith DDL, Kleiman EM, Glenn CR, Millner AJ, Nock MK. The dynamics of social support among suicide attempters: a smartphone-based daily diary study. Behav Res Ther. (2019) 120:103348. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.016

53. Czyz EK, King CA, Biermann BJ. Motivational interviewing-enhanced safety planning for adolescents at high suicide risk: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2019) 48:250–62. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1496442

54. Czyz EK, Glenn CR, Busby D, King CA. Daily patterns in nonsuicidal self-injury and coping among recently hospitalized youth at risk for suicide. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 281:112588. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112588

55. Czyz EK, Horwitz AG, Arango A, King CA. Short-term change and prediction of suicidal ideation among adolescents: a daily diary study following psychiatric hospitalization. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. (2019) 60:732–41. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12974

56. Hallensleben N, Glaesmer H, Forkmann T, Rath D, Strauss M, Kersting A, et al. Predicting suicidal ideation by interpersonal variables, hopelessness and depression in real-time: an ecological momentary assessment study in psychiatric inpatients with depression. Eur Psychiatry. (2019) 56:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.11.003

57. Rath D, de Beurs D, Hallensleben N, Spangenberg L, Glaesmer H, Forkmann T. Modelling suicide ideation from beep to beep: application of network analysis to ecological momentary assessment data. Internet Interv. (2019) 18:100292. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2019.100292

58. Rizk MM, Choo TH, Galfalvy H, Biggs E, Brodsky BS, Oquendo MA, et al. Variability in suicidal ideation is associated with affective instability in suicide attempters with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry. (2019) 82:173–8. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2019.1600219

59. Spangenberg L, Glaesmer H, Hallensleben N, Rath D, Forkmann T. (In)stability of capability for suicide in psychiatric inpatients: Longitudinal assessment using ecological momentary assessments. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2019) 49:1560–72. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12547

60. Victor SE, Scott LN, Stepp SD, Goldstein TR I. want you to want me: interpersonal stress and affective experiences as within-person predictors of nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide urges in daily life. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2019) 49:1157–77. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12513

61. Armey MF, Brick L, Schatten HT, Nugent NR, Miller IW. Ecologically assessed affect and suicidal ideation following psychiatric inpatient hospitalization. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2020) 63:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.09.008

62. Czyz EK, Yap JRT, King CA, Nahum-Shani I. Using intensive longitudinal data to identify early predictors of suicide-related outcomes in high-risk adolescents: practical and conceptual considerations. Assessment. (2020) 28:1949–59. doi: 10.1177/1073191120939168

63. Hadzic A, Spangenberg L, Hallensleben N, Forkmann T, Rath D, Strauß M, et al. The association of trait impulsivity and suicidal ideation and its fluctuation in the context of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Compr Psychiatry. (2020) 98:152158. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.152158

64. Kaurin A, Dombrovski AY, Hallquist MN, Wright AGC. Momentary interpersonal processes of suicidal surges in borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med. (2020). doi: 10.1017/S0033291720004791. [Epub ahead of print].

65. Oquendo MA, Galfalvy HC, Choo TH, Kandlur R, Burke AK, Sublette ME, et al. Highly variable suicidal ideation: a phenotypic marker for stress induced suicide risk. Mol Psychiatry. (2020) 26:5079–86. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0819-0

66. Peters EM, Dong LY, Thomas T, Khalaj S, Balbuena L, Baetz M, et al. Instability of suicidal ideation in patients hospitalized for depression: an exploratory study using smartphone ecological momentary assessment. Arch Suicide Res. (2022) 26:56–69. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2020.1783410

67. Vine V, Victor SE, Mohr H, Byrd AL, Stepp SD. Adolescent suicide risk and experiences of dissociation in daily life. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 287:112870. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112870

68. Aadahl V, Wells A, Hallard R, Pratt D. Metacognitive beliefs and suicidal ideation: an experience sampling study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:12336. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312336

69. Al-Dajani N, Uliaszek AA. The after-effects of momentary suicidal ideation: a preliminary examination of emotion intensity changes following suicidal thoughts. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 302:114027. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114027

70. Cobo A, Porras-Segovia A, Pérez-Rodríguez MM, Artés-Rodríguez A, Barrigón ML, Courtet P, et al. Patients at high risk of suicide before and during a COVID-19 lockdown: ecological momentary assessment study. BJPsych Open. (2021) 7:e82. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.43

71. Hallard RI, Wells A, Aadahl V, Emsley R, Pratt D. Metacognition, rumination and suicidal ideation: an experience sampling test of the self-regulatory executive function model. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 303:114083. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114083

72. Czyz EK, Glenn CR, Arango A, Koo HJ, King CA. Short-term associations between nonsuicidal and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a daily diary study with high-risk adolescents. J Affect Disord. (2021) 292:337–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.104

73. Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Kandlur R, Esposito EC, Liu RT. Thwarted belongingness mediates interpersonal stress and suicidal thoughts: an intensive longitudinal study with high-risk adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychology. (2021). doi: 10.1080/15374416.2021.1969654. [Epub ahead of print].

74. Kaurin A, Hisler G, Dombrovski AY, Hallquist MN, Wright AGC. Sleep and next-day negative affect and suicidal ideation in borderline personality disorder. Pers Disord Theory Res Treat. (2021) 13:160–70. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/z9qke

75. Porras-Segovia A, Cobo A, Díaz-Oliván I, Artés-Rodríguez A, Berrouiguet S, Lopez-Castroman J, et al. Disturbed sleep as a clinical marker of wish to die: a smartphone monitoring study over three months of observation. J Affect Disord. (2021) 286:330–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.059

76. Schatten HT, Brick LA, Holman CS, Czyz E. Differential time varying associations among affective states and suicidal ideation among adolescents following hospital discharge. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 305:114174. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114174

77. Stanley B, Martínez-Alés G, Gratch I, Rizk M, Galfalvy H, Choo TH, et al. Coping strategies that reduce suicidal ideation: an ecological momentary assessment study. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 133:32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.012

78. Victor SE, Brown SL, Scott LN, Hipwell AE, Stepp SD. Prospective and concurrent affective dynamics in self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: an examination in young adult women. Behav Ther. (2021) 52:1158–70. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2021.01.003

79. Wang SB, Coppersmith DDL, Kleiman EM, Bentley KH, Millner AJ, Fortgang R, et al. A pilot study using frequent inpatient assessments of suicidal thinking to predict short-term postdischarge suicidal behavior. JAMA. (2021) 4:e210591. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0591

80. Czyz EK, King CA, Nahum-Shani I. Ecological assessment of daily suicidal thoughts and attempts among suicidal teens after psychiatric hospitalization: lessons about feasibility and acceptability. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 267:566–74. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.031

81. Husky M, Olié E, Guillaume S, Genty C, Swendsen J, Courtet P. Feasibility and validity of ecological momentary assessment in the investigation of suicide risk. Psychiatry Res. (2014) 220:564–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.019

82. Law MK, Furr RM, Arnold EM, Mneimne M, Jaquett C, Fleeson W. Does assessing suicidality frequently and repeatedly cause harm? a randomized control study. Psychol Assess. (2015) 27:1171–81. doi: 10.1037/pas0000118

83. Torous J, Staples P, Shanahan M, Lin C, Peck P, Keshavan M, et al. Utilizing a personal smartphone custom app to assess the patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. JMIR Mental Health. (2015) 2:e8. doi: 10.2196/mental.3889

84. Forkmann T, Spangenberg L, Rath D, Hallensleben N, Hegerl U, Kersting A, et al. Assessing suicidality in real time: a psychometric evaluation of self-report items for the assessment of suicidal ideation and its proximal risk factors using ecological momentary assessments. J Abnorm Psychol. (2018) 127:758–69. doi: 10.1037/abn0000381

85. Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Kearns JC, Santee AC, Esposito EC, Conwell Y, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of ecological momentary assessment with high-risk suicidal adolescents following acute psychiatric care. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2022) 51:32–48. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2020.1741377

86. Gratch I, Choo TH, Galfalvy H, Keilp JG, Itzhaky L, Mann JJ, et al. Detecting suicidal thoughts: the power of ecological momentary assessment. Depress Anxiety. (2021) 38:8–16. doi: 10.1002/da.23043

87. Porras-Segovia A, Molina-Madueño RM, Berrouiguet S, López-Castroman J, Barrigón ML, Pérez-Rodríguez MS, et al. Smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in psychiatric patients and student controls: a real-world feasibility study. J Affect Disord. (2020) 274:733–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.067

88. Rogers ML. Feasibility and acceptability of ecological momentary assessment in a fully online study of community-based adults at high risk for suicide. Psychol Assess. (2021) 33:1215–25. doi: 10.1037/pas0001054

89. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the scale for suicide ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. (1979) 47:343–52. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.47.2.343

90. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova Kv, Oquendo MA, et al. The Columbia–suicide severity rating scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. (2011) 168:1266–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704

91. Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Tucker RP, Hagan CR, et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol Bull. (2017) 143:1313–45. doi: 10.1037/bul0000123

92. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1960) 23:56–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56

93. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

94. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Routledge (1988).

95. Beck AT. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1961) 4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

96. Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, Barrios FX. The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment. (2001) 8:443–54. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800409

97. Cwik JC, Forkmann T, Glaesmer H, Paashaus L, Schönfelder A, Rath D, et al. Validation of the German capability for suicide questionnaire (GCSQ) in a high-risk sample of suicidal inpatients. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:412. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02812-9

98. Han B, Compton WM, Gfroerer J, McKeon R. Prevalence and correlates of past 12-month suicide attempt among adults with past-year suicidal ideation in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. (2015) 76:295–302. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09287

99. Parra-Uribe I, Blasco-Fontecilla H, Garcia-Parés G, Martínez-Naval L, Valero-Coppin O, Cebrià-Meca A, et al. Risk of re-attempts and suicide death after a suicide attempt: a survival analysis. BMC Psychiatry. (2017) 17:163. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1317-z

100. Aouidad A, Cohen D, Mirkovic B, Pellerin H, Garny de La Rivière S, Consoli A, et al. Borderline personality disorder and prior suicide attempts define a severity gradient among hospitalized adolescent suicide attempters. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:525. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02930-4

101. Hektner J, Schmidt J, Csikszentmihalyi M. Experience Sampling Method. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications (2007). doi: 10.4135/9781412984201

102. van Genugten CR, Schuurmans J, Lamers F, Riese H, Penninx BWJH, Schoevers RA, et al. Experienced burden of and adherence to smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment in persons with affective disorders. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:322. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020322

103. Johnson EI, Grondin O, Barrault M, Faytout M, Helbig S, Husky M, et al. Computerized ambulatory monitoring in psychiatry: a multi-site collaborative study of acceptability, compliance, and reactivity. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2009) 18:48–57. doi: 10.1002/mpr.276

104. Courvoisier DS, Eid M, Lischetzke T. Compliance to a cell phone-based ecological momentary assessment study: the effect of time and personality characteristics. Psychol Assess. (2012) 24:713–20. doi: 10.1037/a0026733

105. Hartley S, Varese F, Vasconcelose Sa D, Udachina A, Barrowclough C, Bentall RP, et al. Compliance in experience sampling methodology: the role of demographic and clinical characteristics. Psychosis. (2014) 6:70–3. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2012.752520

106. Jones A, Remmerswaal D, Verveer I, Robinson E, Franken IHA, Wen CKF, et al. Compliance with ecological momentary assessment protocols in substance users: a meta-analysis. Addiction. (2019) 114:609–19. doi: 10.1111/add.14503

107. Wen CKF, Schneider S, Stone AA, Spruijt-Metz D. Compliance with mobile ecological momentary assessment protocols in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2017) 19:e132. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6641

108. Eisele G, Vachon H, Lafit G, Kuppens P, Houben M, Myin-Germeys I, et al. The effects of sampling frequency and questionnaire length on perceived burden, compliance, and careless responding in experience sampling data in a student population. Assessment. (2020) 29:136–51. doi: 10.1177/1073191120957102

109. Rintala A, Wampers M, Myin-Germeys I, Viechtbauer W. Momentary predictors of compliance in studies using the experience sampling method. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 286:112896. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112896

110. Daniëls NEM, Hochstenbach LMJ, van Zelst C, van Bokhoven MA, Delespaul PAEG, Beurskens AJHM. Factors that influence the use of electronic diaries in health care: scoping review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. (2021) 9:e19536. doi: 10.2196/19536

111. Ottenstein C, Werner L. Compliance in ambulatory assessment studies: investigating study and sample characteristics as predictors. Assessment. (2021) 20:10731911211032718. doi: 10.1177/10731911211032718

112. Folkersma W, Veerman V, Ornée DA, Oldehinkel AJ, Alma MA, Bastiaansen JA. Patients' experience of an ecological momentary intervention involving self-monitoring and personalized feedback for depression. Internet Interv. (2021) 26:100436. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100436

113. Barta WD, Tennen H, Litt MD. Measurement reactivity in diary research. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, editors. Handbook of Research Methods For Studying Daily Life. New York, NY: The Guilford Press (2012). p. 108–23.

114. Cruise CE, Broderick J, Portera L, Kae1l A, Stone AA. Reactive effects of diary self-assessment in chronic pain patients. Pain. (1996) 67:253–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03125-9

115. Busch KA, Fawcett J, Jacobs DG. Clinical correlates of inpatient suicide. J Clin Psychiatry. (2003) 64:14–9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v64n0105

116. McDevitt-Murphy ME, Luciano MT, Zakarian RJ. Use of ecological momentary assessment and intervention in treatment with adults. Focus. (2018) 16:370–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20180017

117. Berrouiguet S, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Larsen M, Baca-García E, Courtet P, Oquendo M. From eHealth to iHealth: transition to participatory and personalized medicine in mental health. J Med Int Res. (2018) 20:e2. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7412

118. Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Elliott G, Huffman JC, Nock MK. Real-time monitoring technology in single-case experimental design research: opportunities and challenges. Behav Res Ther. (2019) 117:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.017

119. Harmer B, Lee S, Duong TVH, Saadabadi A. Suicidal Ideation. StatPearls. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441982/ (accessed March 11, 2022).

120. Zuidersma M, Riese H, Snippe E, Booij SH, Wichers M, Bos EH. Single-subject research in psychiatry: facts and fictions. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:539777. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.539777

121. Ballard ED, Gilbert JR, Wusinich C, Zarate CA. New methods for assessing rapid changes in suicide risk. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:598434. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.598434

122. Barrigon ML, Courtet P, Oquendo M, Baca-García E. Precision medicine and suicide: an opportunity for digital health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2019) 21:131. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1119-8

123. von Klipstein L, Riese H, van der Veen DC, Servaas MN, Schoevers RA. Using person-specific networks in psychotherapy: challenges, limitations, and how we could use them anyway. BMC Med. (2020) 18:345. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01818-0

Keywords: suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, experience sampling method, ambulatory assessment, electronic diary

Citation: Kivelä L, van der Does WAJ, Riese H and Antypa N (2022) Don't Miss the Moment: A Systematic Review of Ecological Momentary Assessment in Suicide Research. Front. Digit. Health 4:876595. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2022.876595

Received: 15 February 2022; Accepted: 13 April 2022;

Published: 06 May 2022.

Edited by:

Heleen Riper, VU Amsterdam, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Hiran Thabrew, The University of Auckland, New ZealandCopyright © 2022 Kivelä, van der Does, Riese and Antypa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Niki Antypa, bmFudHlwYUBmc3cubGVpZGVudW5pdi5ubA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.