- 1Healthy Mind Lab, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 2Center for Healthy Work, Department of Internal Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 3Parkinson School of Health Sciences and Public Health, Loyola University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

- 4Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

- 5National Council for Mental Wellbeing, Washington, DC, United States

- 6Thriving Mind South Florida, Miami, FL, United States

Background: We employed Innovation Corps (I-Corps™) methods to adaptation of a mobile health (mHealth) short-message-system (SMS) -based interactive obesity treatment approach (iOTA) for adults with severe mentall illness receiving care in community settings.

Methods: We hypothesized “jobs to be done” in three broad stakeholder groups: “decision makers” (DM = state and community clinic administrators), “clinician consumers” (CC = case managers, peer supports, nurses, prescribers) and “service consumers” (SC = patients, peers and family members). Semistructured interviews (N = 29) were recorded and transcribed ver batim and coded based on pragmatic-variant grounded theory methods.

Results: Four themes emerged across groups: education, inertia, resources and ownership. Sub-themes in education and ownership differed between DM and CC groups on implementation ownership, intersecting with professional development, suggesting the importance of training and supervision in scalability. Sub-themes in resources and intertia differed between CC and SC groups, suggesting illness severity and access to healthy food as major barriers to engagement, whereas the SC group identified the need for enhanced emotional support, in addition to pragmatic skills like menu planning and cooking, to promote health behavior change. Although SMS was percieved as a viable education and support tool, CC and DM groups had limited familiarity with use in clinical care delivery.

Conclusions: Based on customer discovery, the characteristics of a minimum viable iOTA for implementation, scalability and sustainability include population- and context-specific adaptations to treatment content, interventionist training and delivery mechanism. Successful implementation of an SMS-based intervention will likely require micro-adaptations to fit specific clinical settings.

Introduction

Obesity is two to three times more prevalent in people with severe mental illness (SMI), contributing to higher rates of obesity-related conditions like type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared to the general population (1). This burden of cardiometabolic risk contributes to a 10–15 year mortality gap between those with SMI and the general population (2). Obesity treatments that have been tested in real-world treatment environments, like community mental health clinics (CMHCs) and Clubhouse settings where SMI is routinely treated, consist of group or individual counseling sessions delivered either by clinicians or peer health coaches (3, 4). While most interventions are associated with some health behavior change or improved self-efficacy, most fail to separate from controls on a primary outcome of weight loss (5–8). Further, reduction or reversal of weight loss achieved during active treatment is observed as soon as 2 months post-intervention (7), suggesting the need for maintenance treatment in real-world clinical settings (9).

Community-based mental health care is associated with better medical monitoring and treatment engagement in people with SMI (9–11). Many obesity interventions are designed to leverage exisiting resources by relying on clinical staff trained in health coaching (12–14). However, obesity and cardiovascular disease risk are part of a long list of clinical issues that must be addressed by clinical staff, creating significant barriers to successful implementation (15, 16). We aimed to adapt an existing interactive obesity treatment approach (iOTA) (17–19) employing short message system (SMS) texts, a highly utilized technology among low-income and mentally ill populations (20). Semi-automated support texts and weekly prompts to self-monitor weight and goal progress provide opportunities for increased engagement by consumers of clinical services, extending the reach of in-person health coaching (21, 22).

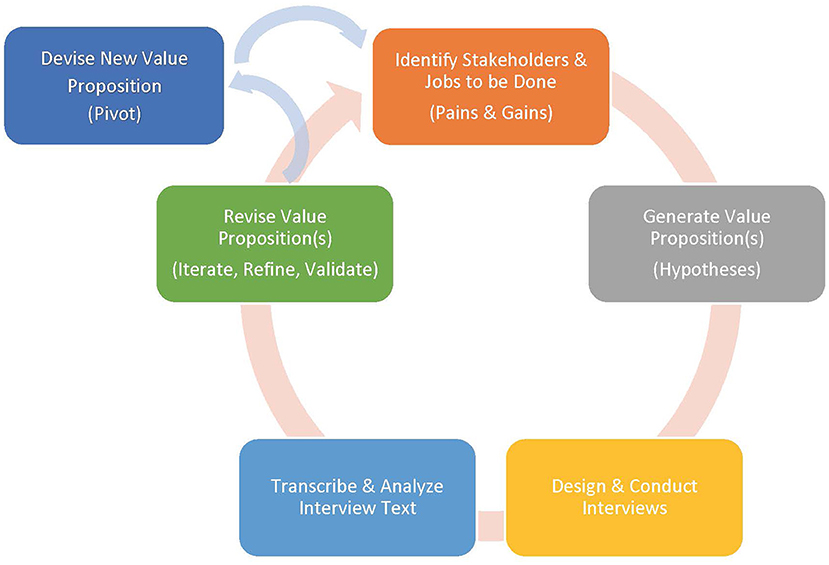

Each CMHC and Clubhouse ecosystem is unique, meaning health promotion programs must be tailored both to the clinical population and treatment setting in order to be successful (23). Thus, multi-level stakeholder engagement is critical for adapting or developing programs before they are implemented (24, 25). Innovation Corps (I-Corps™) methodology, co-created by the National Science Foundation (NSF) (26) and adopted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), (27) uses the design-based Lean Launchpad approach, popularized for tech startups for the academic research audience to facilitate customer-centered design and promote more successful commercialization of technology and engineering innovation into real-world settings and markets (28, 29). The emphasis of the I-Corps method is on immediate and iterative collection of stakeholder feedback via “customer discovery” interviews to identify and validate a “value proposition” for key consumers (Figure 1). From this, major “gains,” “pains” and “jobs to be done” are identified, and used to revise assumptions and hypotheses, testing redesigned offerings and making further small adjustments (iterations) or more substantive ones (pivots) to improve outcomes.

In the present study, we employed I-Corps methods to identify challenges or “pains” associated with wellness program implementation in CMHC and Clubhouse settings. In general, the project team hypothesized that some areas of concern would be thematically unified across stakeholder groups. We also expected that certain barriers faced by each group would be unique, with overlap between stakeholders with similar roles. In order to allow for a broader interview framework, we formed our hypotheses based on stakeholder groups condensed into three broad categories: decision makers (DM; state and local clinical administration), clinician consumers (CC; nurses, prescribers, community support workers, case managers, psychosocial rehabilitation counselors, peer supports) and service consumers (SC), related to successful implementation of hybrid health coaching interventions targeting weight management via lifestyle change. We hypothesized that barriers for the DM groups would include limited resources to support implementation, while CC groups would experience barriers relative to burnout and mismatch between administrative expectations and clinician reality. Lastly, we expected barriers at the SC level to include illness-related difficulties managing the increased cognitive load associated with learning and practicing new health behaviors, leading to reduced motivation and engagement.

Methods

I-Corps methodology consists of four steps: (1) identify the relevant target consumers and decision-makers as key stakeholders, (2) identify potential unmet needs or issues in the existing services or products relative to available alternatives, including the status quo, (3) create testable and pliable “value proposition” hypotheses for the proposed products or services solutions based on these unmet needs, and (4) conduct customer-stakeholder interviews to identify and validate which problems resonate as the most critical or most important to solve (Figure 1).

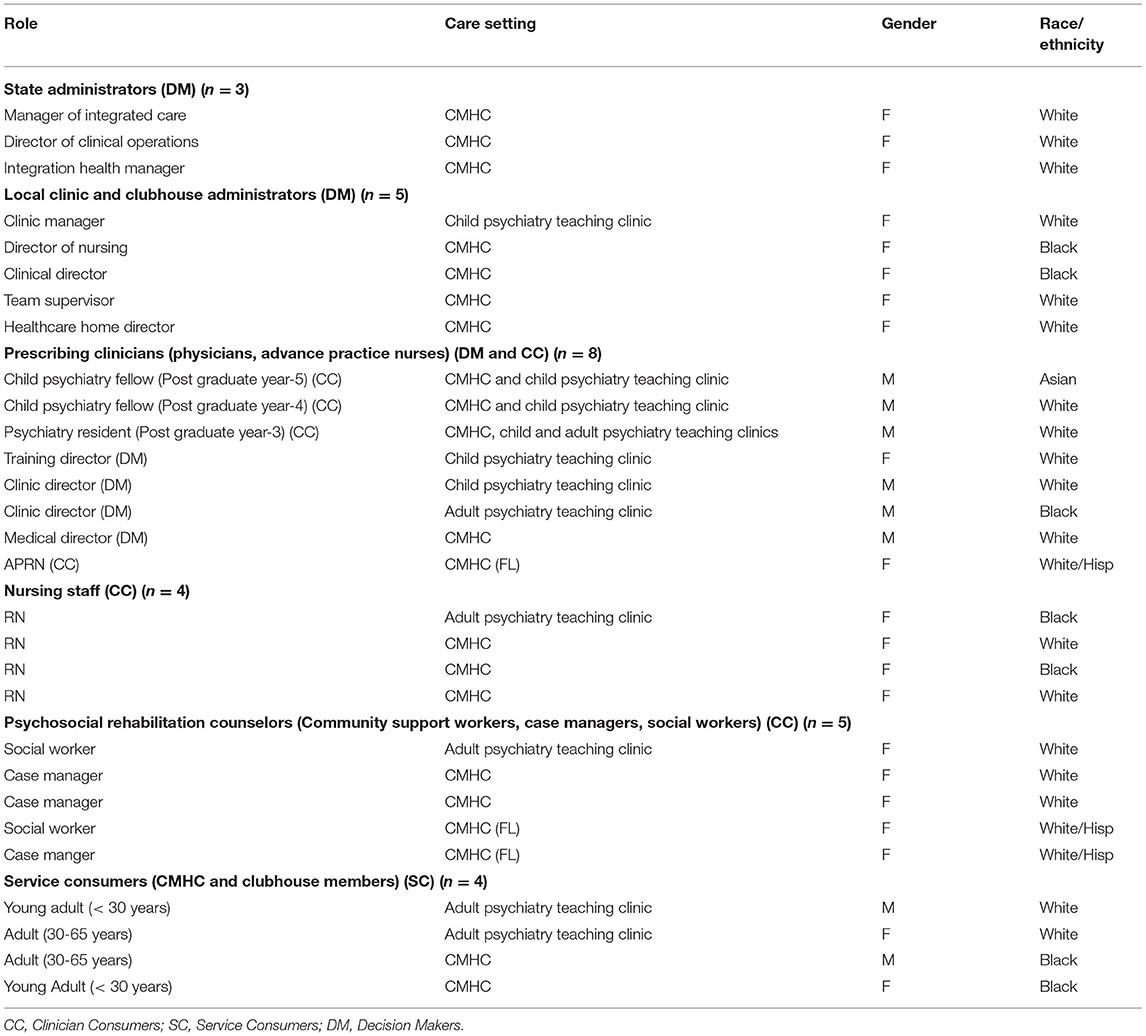

Five settings in Missouri and Florida were identified for discovery—two CMHCs treating children, adolescents and adults, one Clubhouse, and two ambulatory academic teaching clinics, one treating children and adolescents, and one treating adults. Purposive sampling methods were used to identify relevant stakeholders with diverse perspectives on technology, community mental health care and healthy lifestyle interventions (30). Specifically, the study team built upon existing relationships with clinical leadership and knowledge of the clinical settings to recruit for interview and focus group participants. Clinical leadership were asked to provide recommendations for stakeholders, as well as introductions to leaders in each stakeholder group.

Based on the clinical structure and hierarchy in most community clinical settings, and in consultation with clinical leadership in each setting, we identified 6 broad stakeholder groups across the three categories: “Service Consumers,” included ambulatory outpatients, CMHC and Clubhouse members, (n = 4); “Clinician Consumers,” included nurses (n = 4), psychosocial rehabilitation (PSR) counselors, community support workers, case mangers, social workers (n = 5), and prescribing clinicians (attending, resident and fellow physicians, advance practice nurses) (n = 8); “Decision Makers,” included local clinic and clubhouse administrators (n = 5), and state administrators (n = 3).

We hypothesized that each stakeholder group would have unique jobs and associated barriers when engaging clinical service consumers in health behavior change related to weight management, but that the use of simple technology to provide reminders and reinforce goal-oriented health behavior change would be viewed favorably as a tool for providing enhanced support to clinical service consumers compared to existing practices thereby extending the clinician's impact without increasing work burden or cost. From this hypothesis, we generated an initial value proposition statement: “an iOTA, in combination with existing health coaching approaches, can help clinicians more effectively engage consumers of clinical services in health behavior change compared with the leading alternative of counseling on energy-balance (e.g., calories consumed versus calories burned) delivered by staff with limited training or programmatic structure.”

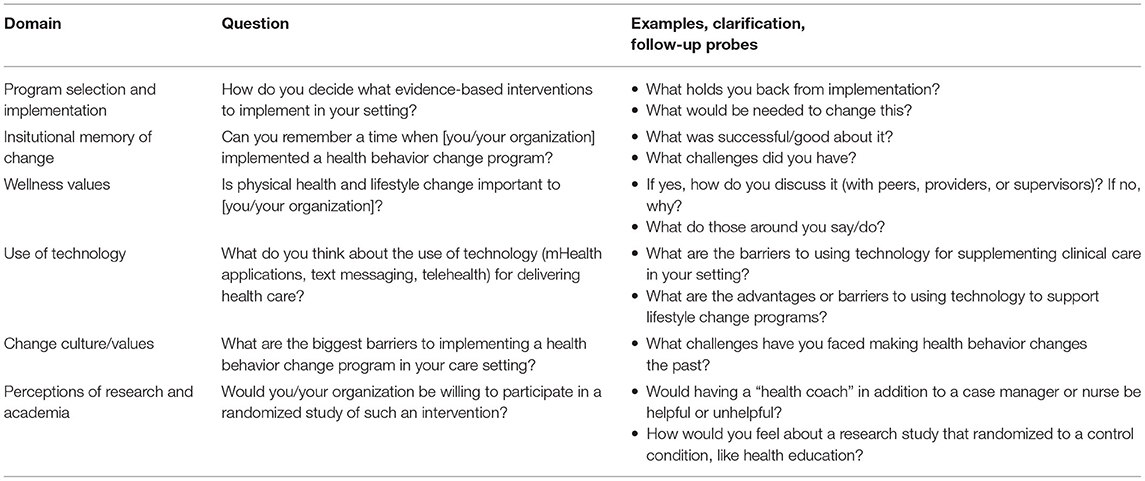

We then created a brief semi-structured interview (Table 1) to identify stakeholder attitudes and beliefs about weight managemet (is it a priority “job to be done”?), experience with selecting and executing wellness interventions, including benefits or benchmarks of success (“gains”) and barriers or challenges to successful implementation (“pains”). Follow-up questions were based on the research team's prior knowledge of the CMHC settings, as well as review of the existing implementation research in this area (15).

Data Analysis

Interviews were continued until thematic saturation was achieved and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were analyzed using an inductive coding approach based on pragmatic-variant grounded theory (31). The first and second authors (RH and CD) independently identified emergent codes related to barriers to and facilitators of successful health behavior change programming across stakeholder groups. This initial set of coding was reviewed by the senior authors (GN and JN) to identify and remove unclear and redundant codes, or discrepancies, and to evaluate for any bias. Reliability in the initial coding phase was achieved through consensus discussions and related code modifications until consensus was reached. Revisions to hypothesized “jobs to be done”, “pains” and “gains” for each stakeholder group were based on prevalent themes and reviewed for consensus among members of the research team before being included in the final data set. The final set of themes and subthemes were then used to revise the value proposition. Nvivo-12 (32) software was used to track coding notes, changes, categories, and frequencies of codes and quotations.

Results

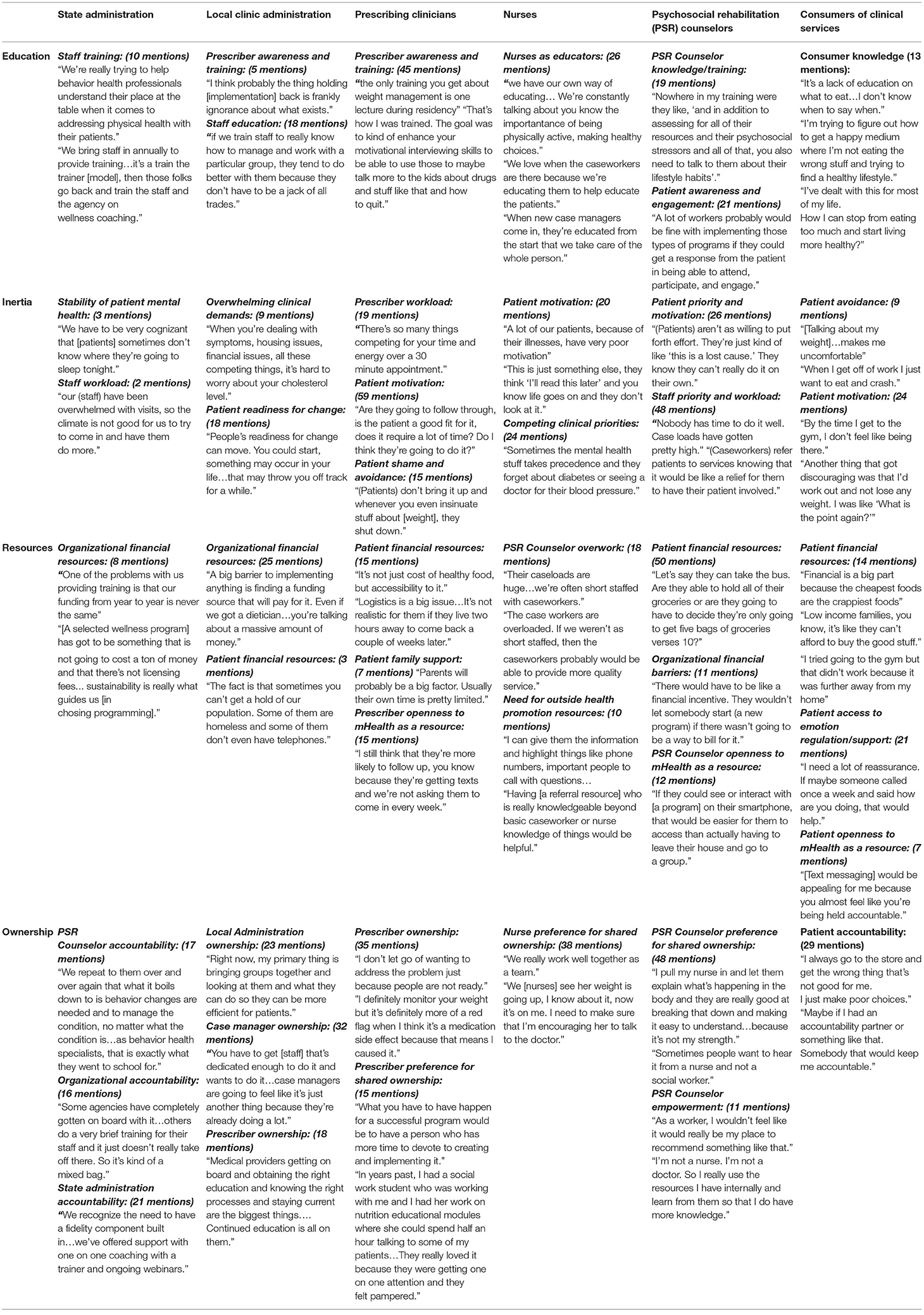

Twenty-nine stakeholder participants were identified within the selected clinical settings and consented to participate in the study. The breakdown of characteristics by stakeholder group can be found in Table 2. Four broad themes emerged across stakeholders. These included Education, with sub-themes of existing knowledge and awareness, professional training, and clinicians as educators; Inertia, with sub-themes of symptom severity, readiness for change, motivation, avoidance and overwhelm; Resources, with sub-themes of scarcity in financial resources, social support, referral resources, access to psychological support and consideration of mobile technology as a resource; and Ownership, with sub-themes of accountability, preference for individual vs. shared process ownership, and staff empowerment. Unique jobs to be done, pains and gains were identified in each stakeholder group. Representative quotes and number of mentions within each sub-theme, by stakeholder group are listed in Table 3 and summarized in detail below based on stage of the I-Corps customer discovery process.

Consumer Jobs to Be Done

State Administrators

State administrators considered physical and mental health to be of equal importance, and viewed their primary jobs related to physical health and weight management of clinical consumers as (1) selecting physical health and wellness programs for statewide implementation based on needs identified by local clinical administration, (2) providing staff training for dissemination, and (3) ensuring sustainability of implementation with ongoing fidelity monitoring.

Local Clinic Administrators

Local clinic administrators acknowledged the importance of addressing SC physical health in balance with acute SC care needs and staff workload, and perceived their primary responsibilities as promoting clinician accountability for professional development, fostering a workplace culture of team-based clinical care, and protecting clinician time for SC care.

Prescribing Clinicians

Prescribing clinicians felt a responsibility to help treatment teams prioritize the often competing physical and mental health demands in order to determine which SCs would benefit from or be likely to engage in an intervention, support the clinician providing health coaching and reduce health risks by optimizing medical monitoring and management.

Nurses

Nurses embraced responsibility for supporting physical health of SCs, and considered themselves as process owners who prioritize organizational values regarding physical health and wellness. Among their primary job functions, nurses supported medical recommendations via education and coaching to promote health behavior change.

Psychosocial Rehabilitation Counselors

PSR counselors were the clinicians most likely to be assigned health coacing roles in each setting. They viewed themselves as process owners for implementation of the treatment plan, focused on optimizing psychosocial functioning and quality of life, and addressing acute psychosocial concerns (e.g., housing, legal concerns). However, this group did not believe they were best suited to own the process of addressing physical health, including the implementation of weight management programming, which was viewed as separate from the overall treatment plan.

Service Consumers

SCs indicated that their greatest needs were in accountability, particularly in staying engaged with self-monitoring. Thus, as physicians noted engagement as a reason for their inertia in delivering behavioral lifestyle counseling, SCs also noted this as a problem—one they wanted help with.

Consumer Barriers or “Pains”

State Administrators

State administrators noted that many available health and wellness programs required financial commitments for ongoing training or licensing (education, resources). Inconsistent program implementation at the local level was attributed to turnover or attrition of staff trained as trainers, and to limited time to participate in ongoing training to ensure fidelity of intervention delivery (resources, education). Digital and mobile health (mHealth) interventions were perceived as potential barriers to adoption of new interventions due to variability in use of technology from setting to setting, with equally varied attitudes toward technology within each unique clinical setting.

Local Clinic Administrators

Local clinic administrators noted that although training offered by the state was free, clinics were still responsible for covering the time away from SC care to accommodate training and trainer activities. In absence of resources to make up for loss of revenue-generating activities, directors were tasked with identifying existing resources to support program implementation and sustainability.

Prescribing Clinicians

Prescribing clinicians in teaching roles expressed confidence in the use of motivational interviewing for promoting healthier behaviors, while physician trainees were less confident, indicating limited didactic or experiential learning on the subject. Both groups acknowledged implementation challenges related to process ownership and SC engagement.

Nurses

Nurses were most likely to either create resource lists or design their own coaching approach with SC in settings where internally available programs were not available. Limited time and competing clinical demands posed the biggest challenges to implementation.

Psychosocial Rehabilitation Counselors

PSR counselors, though trained as health coaches in many settings, felt less secure in their medical knowledge, and were reluctant to accept ownership of this role. Attrition of staff who led original trainings lead to degradation of treatment delivery over time.

Service Consumers

SCs noted that lack of emotion regulation skills and social supports reduced their resolve to make healthy choices. They indicated a need for problem-solving help with pragmatic issues such as where to buy fresh produce with limited money, how to cook healthier foods and how to make healthy selections when not eating at home (e.g., at the Clubhouse cafeteria).

Consumer Benefits or “Gains”

State Administration

State administration considered successful training and program implementation in terms of SC-level health outcomes, as well as in workforce development. Employing a “train the trainer” model was seen as a way to reduce training costs while empowering local organizations and staff, increasing uptake and organizational culture change. The use of semi-automated SMS texting was seen as a possible augmentation to existing care to extend clinician reach and increase SC engagement.

Local Clinic Administration

Local clinic administration viewed collaboration with academic researchers as a career development opportunity for staff and an opportunity to enhance clinical care. Administrators considered mobile technology as useful in concept, but saw potential barriers to implementation in terms of integration with the current work flow for clinicians. Subthemes under ownership also involved protection—of SCs (safety) and of staff (from additional work burden).

Prescribing Clinicians

Prescribing clinicians identified SC engagement as a major contributor to successful treatment outcomes, impacted by intrinsic motivation or incentive, shame/avoidance, and previous negative experiences—both from the perspective of the physician (limited perceived benefit for additional work burden) and the SC/family (limited perceived benefit for additional burden of time and mental energy). In general, physicians viewed mobile technology as a potential solution to the additional work burden and to SC engagement in wellness programming.

Nurses

Nurses noted they could fill in gaps when case managers were dealing with competing psychosocial clinical priorities that took precedence over health prevention measures. In settings where wellness programming was available, nurses consistently refered SCs to those programs and seemed to have the most knowledge about them. Nurses cautiously perceived mobile technology as a way to increase engagement in wellness programming, but did not feel this could take the place of education or clinical care.

Psychosocial Rehabilitation Counselors

PSR counselors preferred a team approach to delivering health interventions with their SCs, and perceived the use of technology to extend their reach to SCs as potentially helpful as long as this respected therapeutic boundaries or safety of personal data.

Service Consumers

SCs indicated an openness to the use of mHealth technology to increase their sense of external support and accountability, indicating that they would be most comfortable with a case manager in the role as health coach.

Evolution of the Value Proposition

Similarities in priorities across groups were observed (Table 3). Administartors wanted a sustainable, effective and low-cost intervention. Nurses asked for an intervention that takes into consideration the dynamic needs of the SC population and emphasizes team-based care. PSR counselors supported an intervention that would help them and their SCs without adding a time burden, and were supportive of mHealth for this purpose. Physicians wanted to be able to refer to a behavioral weight loss program and actively track their pateint's results. SCs wanted a simple intervention that addresses energy balance while providing emotional support. With this insight, our overall value proposition became “Enhancement of existing wellness programming with low-cost text messaging support can promote health behavior change in SCs with SMI better than the current leading alternative of counseling on energy balance delivered by staff with limited training.”

Discussion

Using I-Corps, a novel stakeholder-centered method for designing health intervention for dissemination and sustainabilitys, our results suggest adjustments to the current health coaching delivery model are needed for successful implementation in community setting. In particular, case manager time constraints and challenges to successful SC engagement were cited as significant barriers to implementation, with most respondents expressing a belief that technology could be used to simplify treatment delivery and improve engagement. Additional barriers to uptake included role confusion (e.g., which clinician holds ownership of the process), fragmented communication between providers, and low motivation for change among SCs. This study provides critically-needed information for the successful adaptation of obesity treatment for the SMI population, addressing contextual factors relevant to the CMHC and Clubhouse settings.

The four major “barrier” themes (resources, education, inertia and ownership), while similar across groups, were interpreted differently based on stakeholder “jobs to be done.” A final fifth barrier was identified, involving discrepancy in who should function as the health coach. Decision makers identified PSR counselors and/or case managers as being the best positioned to function as health coaches, given their proximity and rapport with SCs. Nonetheless, this group was reluctant to accept ownership of this role. These results extend previous work suggesting that barriers to successful treatment engagement are multifactorial, involving specific challenges at the SC, provider and organizational levels (33). However, few studies have explicitly evaluated barriers specific to treatment setting, including the perspective of SCs, potential interventionists, treatment team leaders and decision-makers (34).

The use of technology to extend the reach of health coaches was seen as promising by both clinicians and SCs. Our results suggest adaptations to traditional health coaching delivery models, where existing clinical staff are trained and responsible for implementation, may benefit from the introduction of technology. These results are consistent with previous reports in SMI populations suggesting openness to the use of technology for delivering health behavior change interventions, which have been shown to boost treatment engagement in non-mentally ill obese adults (1, 35, 36).

The present study is subject to strengths and limitations. First, the I-Corps approach is a proven methodology consistent with best practices for designing for dissemination and diffusion of health innovations (37, 38). Though we perceive interviewing stakeholders at different settings in two states as a major strength, this approach does not fully address limitations to the generalizability of our results. Grouping all mental illnesses under “SMI”, and interviewing only four SCs also limits generalizability for specific diagnoses. Finally, using a qualitative process that relies heavily on self report subjects our data to reporting bias. Despite these limitations, this study also has several innovative aspects that strengthen the qualitative research methods. First, we employed an evidence-based, holistic mixed-methods approach (39, 40), including clinical use validation, to anticipate context-specific treatment adaptations ahead of implementation. This is a critical step in translating evidence-based interventions into real-world settings. We also employed gold-standard sampling methods and coding techniques, as well as strengthened rigor and reproducibility by engaging in consensus coding exercises (41, 42). In summary, this study demonstrates the application of novel qualitative methodology as first steps toward adapting and implementing weight management interventions in community mental health treatment settings.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Washington University Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UL1TR002535, UL1TR003096, UL1TR001417, and the National Institute of Mental Health Grant Numbers MH112473 and MH118395. This work was also made possible by Public Health Cubed seed funding via the Washington University School of Medicine Institute for Public Health.

Author Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

BE has received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). EM has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the CDC and has consulted for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Eli Lilly and Company. JP has participated in Advisory panels or consulted with Merck, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Janssen. JN has participated in advisory panels or consulted with Merck, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Janssen; has received grant support from the NIH and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); has served as a consultant for Alkermes, Inc., Intra-cellular Therapies, Inc., Sunovion and Merck; and served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Amgen. GN has received grant support from the NIH, the Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation, the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience, and Usona Institute (drug only), and has served as a consultant for Alkermes, Inc., Otsuka and Sunovion.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank everyone who participated in interviews for this project, including leadership, clinicians, staff, consumers, and their family members at BJC Behavioral Health, the Independence Center, Places for People, the Washington University School of Medicine Outpatient Child, and Adult Psychiatry Clinics in St. Louis Missouri, Fellowship House in Miami, FL, and the leadership at the Missouri Coalition for Behavioral Health and the National Council on Behavioral Health.

References

1. Nicol G, Worsham E, Haire-Joshu D, Duncan A, Schweiger J, Yingling M, et al. Getting to more effective weight management in antipsychotic-treated youth: a survey of barriers and preferences. Child Obes. (2016) 12:70–6. doi: 10.1089/chi.2015.0076

2. Prevention CfDCa. Fitness for Mentally Ill Who Have Obesity. Atlanta, GA: Prevention CfDCa(2017).

3. Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, Bona JR, Fricks L, Jenkins-Tucker S, et al. The health and recovery peer (HARP) program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Res. (2010) 118:264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.026

4. O'Hara K, Stefancic A, Cabassa LJ. Developing a peer-based healthy lifestyle program for people with serious mental illness in supportive housing. Transl Behav Med. (2017) 7:793–803. doi: 10.1007/s13142-016-0457-x

5. Verhaeghe N, De Maeseneer J, Maes L, Van Heeringen C, Bogaert V, Clays E, et al. Health promotion intervention in mental health care: design and baseline findings of a cluster preference randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health Jun. (2012) 12:431. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-431

6. Goldberg RW, Reeves G, Tapscott S, Medoff D, Dickerson F, Goldberg AP, et al. “MOVE!” outcomes of a weight loss program modified for veterans with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. (2013) 64:737–44. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200314

7. Bartels SJ, Pratt SI, Aschbrenner KA, Barre LK, Naslund JA, Wolfe R, et al. Pragmatic replication trial of health promotion coaching for obesity in serious mental illness and maintenance of outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. (2015) 172:344–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030357

8. Bartels SJ, Pratt SI, Aschbrenner KA, Barre LK, Jue K, Wolfe RS, et al. Clinically significant improved fitness and weight loss among overweight persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. (2013) 64:729–36. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.003622012

9. Murphy KA, Daumit GL, Stone E, McGinty EE. Physical health outcomes and implementation of behavioural health homes: a comprehensive review. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2018) 30:224–41. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1555153

10. Nicol GE, Campagna EJ, Garfield LD, Newcomer JW, Parks JJ, Morrato EH. The role of clinical setting and management approach in metabolic testing among youths and adults treated with antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv. (2016) 67:128–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400428

11. Stein GL, Lee CS, Shi P, Cook BL, Papajorgji-Taylor D, Carson NJ, et al. Characteristics of community mental health clinics associated with treatment engagement. Psychiatr Serv. (2014) 65:1020–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300231

12. Daumit GL, Dickerson FB, Wang NY, Dalcin A, Jerome GJ, Anderson CA, et al. A behavioral weight-loss intervention in persons with serious mental illness. N Engl J Med. (2013) 368:1594–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214530

13. Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Correll CU, John M, Kurian BT, Marcy P, et al. Psychopharmacological Treatment in the RAISE-ETP Study: Outcomes of a Manual and Computer Decision Support System Based Intervention. Am J Psychiatry. (2017) 175:169–79. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16080919

14. Alvarez-Jiménez M, González-Blanch C, Vázquez-Barquero JL, Pérez-Iglesias R, Martínez-García O, Pérez-Pardal T, et al. Attenuation of antipsychotic-induced weight gain with early behavioral intervention in drug-naive first-episode psychosis patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. (2006) 67:1253–60. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0812

15. Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, Monroe-DeVita M, Pfahler C. Burnout in mental health services: a review of the problem and its remediation. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2012) 39:341–52. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0352-1

16. Veage S, Ciarrochi J, Deane FP, Andresen R, Oades LG, Crowe TP. Value congruence, importance and success and in the workplace: links with well-being and burnout amongst mental health practitioners. J Contextual Behav Sci. (2014) 3:258–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.06.004

17. Glasgow RE, Askew S, Purcell P, Levine E, Warner ET, Stange KC, et al. Use of RE-AIM to address health inequities: application in a low-income community health center based weight loss and hypertension self-management program. Transl Behav Med. (2013) 3:200–10. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0201-8

18. Ritzwoller DP, Glasgow RE, Sukhanova AY, Bennett GG, Warner ET, Greaney ML, et al. Economic analyses of the be fit be well program: a weight loss program for community health centers. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 28:1581–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2492-3

19. Bennett GG, Warner ET, Glasgow RE, Askew S, Goldman J, Ritzwoller DP, et al. Obesity treatment for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients in primary care practice. Arch Intern Med. (2012) 172:565–74. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1

20. Newport F. The New Era of Communication Among Americans. Gallup News (2014). Available online at: http://news.gallup.com/poll/179288/new-era-communication-americans.aspx (accessed November 10, 2014).

21. Tabak RG, Schwarz CD, Kemner A, Schechtman KB, Steger-May K, Byrth V, et al. Disseminating and implementing a lifestyle-based healthy weight program for mothers in a national organization: a study protocol for a cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:68. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0916-0

22. Stein RI, Strickland JR, Tabak RG, Dale AM, Colditz GA, Evanoff BA. Design of a randomized trial testing a multi-level weight-control intervention to reduce obesity and related health conditions in low-income workers. Contemp Clin Trials. (2019) 79:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.01.011

23. Daumit GL, Dalcin AT, Dickerson FB, Miller ER, Evins AE, Cather C, et al. Effect of a comprehensive cardiovascular risk reduction intervention in persons with serious mental illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e207247. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.7247

24. Ward MC, White DT, Druss BG. A meta-review of lifestyle interventions for cardiovascular risk factors in the general medical population: lessons for individuals with serious mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. (2015) 76:e477–86. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08657

25. Liu NH, Daumit GL, Dua T, Aquila R, Charlson F, Cuijpers P, et al. Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry. (2017) 16:30–40. doi: 10.1002/wps.20384

26. Foundation, NS. NSF Innovation Corps. https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2021/nsf21552/nsf21552.htm (accessed February 5, 2018).

27. Health NIo. I-Corps at NIH. Available online at: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PA-19-029.html (accessed February 5, 2018).

28. Blank S. How We Changed the Way the US Government Commercializes Science. New York, NY: Huffington Post (2015).

29. Blank SEJ. The National Science Foundation Innovation Corps™ Teaching Handbook. Hadley, MA: VentureWell (2018).

30. American Psychological Association. Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association (2012). p. viii, 330

31. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

33. Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, Siskind D, Rosenbaum S, Galletly C, et al. The lancet psychiatry commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:675–712. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30132-4

34. Kepper MM, Walsh-Bailey C, Brownson RC, Kwan BM, Morrato EH, Garbutt J, et al. Development of a health information technology tool for behavior change to address obesity and prevent chronic disease among adolescents: designing for dissemination and sustainment using the ORBIT model. Front Digit Health. (2021) 3:648777. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2021.648777

35. Young AS, Cohen AN, Goldberg R, Hellemann G, Kreyenbuhl J, Niv N, et al. Improving weight in people with serious mental illness: the effectiveness of computerized services with peer coaches. J Gen Intern Med Apr. (2017) 32:48–55. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3963-0

36. Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh HC, Wang NY, Coughlin JW, Daumit G, et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med Nov. (2011) 365:1959–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108660

37. Dearing JW, Kreuter MW. Designing for diffusion: how can we increase uptake of cancer communication innovations? Patient Educ Couns. (2010) 81:S100–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.013

38. Chambers DA. Sharpening our focus on designing for dissemination: Lessons from the SPRINT program and potential next steps for the field. Transl Behav Med. (2019) 10:1416–8. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz102

39. Albright K, Gechter K, Kempe A. Importance of mixed methods in pragmatic trials and dissemination and implementation research. Acad Pediatr. (2013) 13:400–7. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.06.010

40. Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. A typology of mixed methods research designs. Qual Quant. (2009) 43:265–75. doi: 10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3

41. Schwarze ML, Kaji AH, Ghaferi AA. Practical guide to qualitative analysis. JAMA Surg. (2020) 155:252–3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4385

Keywords: mentally ill persons, health services, implementation science, innovation-corps, clinical and translational science, obesity

Citation: Haddad R, Badke D'Andrea C, Ricchio A, Evanoff B, Morrato EH, Parks J, Newcomer JW and Nicol GE (2022) Using Innovation-Corps (I-Corps™) Methods to Adapt a Mobile Health (mHealth) Obesity Treatment for Community Mental Health Settings. Front. Digit. Health 4:835002. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2022.835002

Received: 14 December 2021; Accepted: 25 April 2022;

Published: 27 May 2022.

Edited by:

Oswald David Kothgassner, Medical University of Vienna, AustriaReviewed by:

Michael Musker, University of South Australia, AustraliaLinda Fleisher, Fox Chase Cancer Center, United States

Copyright © 2022 Haddad, Badke D'Andrea, Ricchio, Evanoff, Morrato, Parks, Newcomer and Nicol. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ginger E. Nicol, bmljb2xnQHd1c3RsLmVkdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Rita Haddad

Rita Haddad Carolina Badke D'Andrea

Carolina Badke D'Andrea Amanda Ricchio1

Amanda Ricchio1 Bradley Evanoff

Bradley Evanoff Elaine H. Morrato

Elaine H. Morrato Ginger E. Nicol

Ginger E. Nicol