- 1College of Comprehensive Psychology, Ritsumeikan University, Ibaraki, Osaka, Japan

- 2Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University, Suita, Osaka, Japan

This cross-sectional study examined whether reputational concerns moderated the relationship between lying and depression in adolescence. We conducted an online survey of 1,022 Japanese high school students between the ages of 15 and 18 (474 males and 548 females). Results showed that the relationship between selfish lying and depression was not moderated by either rejection avoidance or praise seeking. In contrast, the relationship between prosocial lying and depression was moderated by both rejection avoidance and praise seeking. Specifically, when rejection avoidance and praise seeking were high and when rejection avoidance was high and praise seeking was low, those with higher tendencies toward prosocial lying exhibited higher levels of depression. When rejection avoidance was low and praise seeking was high, those with higher tendencies toward prosocial lying had lower levels of depression. Our findings indicate that reputational concerns complexly moderate the relationship between lying and depression in adolescence.

1 Introduction

People often lie (Cantarero et al., 2018; DePaulo and Bell, 1996; DePaulo et al., 1996; Gerlach et al., 2019). The frequency of lying is higher in adolescence than in childhood or adulthood, and the sophistication of lying also increases from childhood to adolescence (Debey et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2004; Levine et al., 2013). Although lying can help people avoid interpersonal conflict (DePaulo and Kashy, 1998), it increases depressive symptoms in adolescents who lie (Dykstra et al., 2020a,b). This study addressed sensitivity to one's reputation as a moderator of the relationship between lying and depression in adolescence.

There are two types of lying: selfish lying and prosocial lying (DePaulo and Kashy, 1998; Levine and Schweitzer, 2015). Selfish lying refers to statements made to mislead others for the liar's own benefit (Levine and Lupoli, 2022; Levine and Schweitzer, 2014). For example, an adolescent may tell their teacher that they “forgot” their homework when in fact they didn't complete it, or they may fabricate an illness to avoid a shift at their part-time job. Selfish lying is used by individuals for their own benefit or to avoid disadvantages (DePaulo and Kashy, 1998). This type of lying is likely to result in short-term self-interest but long-term issues, such as decreased self-esteem and disrupted interpersonal relationships (Levine and Schweitzer, 2015; Schweitzer et al., 2006). Prosocial lying refers to statements made to mislead others with the intention of benefiting others (Levine and Lupoli, 2022; Levine and Schweitzer, 2014). Examples in adolescent contexts include complimenting a friend's unflattering new hairstyle in order to spare their feelings, or expressing enthusiasm for an unwanted gift from a romantic partner in order to avoid disappointment. Prosocial lying is used to avoid hurting others' feelings and to facilitate interpersonal relationships (DePaulo and Kashy, 1998; Levine and Schweitzer, 2015). Individuals who lie prosocially are viewed as positive and moral when their intentions are benevolent, but negative and unethical when their intentions are paternalistic (Levine and Lupoli, 2022). These lies have the potential to be very painful when discovered.

It is challenging for adolescents to adapt to a complex and dynamic social environment. In such situations, lying has complex consequences for their social and psychological adjustment. For example, adolescents' selfish lying to their parents is one method of asserting autonomy, leading to a greater scope for self-determination (Jensen et al., 2004). Additionally, prosocial lying, such as when an adolescent receiving a disappointing gift expresses a positive response instead, may help maintain social relationships and protect others' self-esteem (DePaulo and Kashy, 1998). These findings indicate that adolescent lying also functions as a skill for social adjustment and facilitates social interactions. However, it can also lead to psychological maladjustment. For example, lying increases depressive symptoms and stress responses in adolescence (Dykstra et al., 2020a,b; Engels et al., 2006; Smetana et al., 2009; Warr, 2007). Moreover, lying leads to decreased self-esteem in and increased negative affect in adolescents and adults (Preuter et al., 2024). Thus, lying has complex consequences for social and psychological adjustment in adolescence.

Which individuals are most likely to be negatively influenced by lying? This study focused on reputational concerns and whether they moderate the relationship between lying and depression in adolescence. Reputation plays an important role in establishing and maintaining complex social interactions (Nowak and Sigmund, 2005). Individuals differ in their sensitivity to their reputation (i.e., reputational concern), which can be broadly classified into rejection avoidance and praise seeking (Kojima et al., 2003). Rejection avoidance refers to the desire to avoid negative reputations from others, while praise seeking refers to the desire to obtain positive reputations from others (Kojima et al., 2003). Those with high rejection avoidance have a strong fear of “not being liked” or “being rejected” and tend to be modest in their behavior (e.g., avoidance of conspicuousness, fear of failure). In contrast, those with high praise seeking have a strong desire to be “praised” or “recognized” and act proactively to make a good impression on others (e.g., taking prominent roles, making self-promotional statements). Adolescents have especially high levels of both rejection avoidance and praise seeking, and their interpersonal behavior is strongly influenced by their reputational concerns. For example, adolescents are more likely to engage in risky or illegal behaviors such as drinking, smoking, and drug use with their peers, which is underpinned by both a desire to avoid a negative reputation and to earn a positive reputation from those peers (Blakemore, 2018; Tomova et al., 2021). Based on these findings, it is possible that rejection avoidance and praise seeking in adolescence are closely related not only to unhealthy and risky behaviors, but also to complex interpersonal behaviors such as lying, which can be moral or unethical depending on the situation. Because adolescents may lie about their experiences to avoid rejection by peers (Dykstra et al., 2020b), those with higher rejection avoidance tendencies may also be more likely to lie. They may also be more likely to feel anxiety and fear that others will reject them if their lies are discovered. Furthermore, because lying can be a tactic to convey a positive image of oneself (Guzikevits and Choshen-Hillel, 2022), those with high levels of praise seeking may be more likely to lie. However, no studies have examined the role of reputational concerns in the relationship between lying and depression.

This cross-sectional study examined whether reputational concerns moderate the relationship between lying and depression in adolescence. First, this study examined whether rejection avoidance and praise seeking, respectively, moderate the relationship between lying and depression. Those with high levels of rejection avoidance may be more sensitive to the fear of being rejected by others if their lies are exposed. When a lie is discovered, the liar is evaluated negatively by others (Gordon and Miller, 2000; Schweitzer et al., 2006). Moreover, the more anxious and fearful one feels, the higher the level of depression (Naragon-Gainey, 2010). Based on these findings, we predicted that higher rejection avoidance would be associated with higher depression during both selfish and prosocial lying. On the other hand, those with high levels of praise seeking are highly motivated to obtain praise and approval from others and actively seek to make a positive impression on others. This tendency may buffer the negative effects of lying because they value the social rewards of lying (DePaulo and Kashy, 1998; Levine and Lupoli, 2022) more than the potential social losses of being caught lying (Gordon and Miller, 2000; Schweitzer et al., 2006). Thus, we predicted that higher praise seeking would be associated with lower depression during both selfish and prosocial lying. Second, this study also exploratory examined whether rejection avoidance and praise seeking not only independently but also in complex interactions moderate the relationship between lying and depression. This is because it has been suggested that the two aspects of reputational concerns are intertwined in complex ways behind behavior in adolescence (Blakemore, 2018; Tomova et al., 2021). For example, those with high rejection avoidance and low praise seeking may have higher depression during selfish and prosocial lying because they are more sensitive to the fear of being rejected by others if their lies are discovered than to the approval or praise they gain from lying (Levine and Lupoli, 2022; Schweitzer et al., 2006). Conversely, those with low rejection avoidance and high praise seeking may emphasize the potential social rewards of lying, such as praise and approval (DePaulo and Kashy, 1998; Levine and Lupoli, 2022), and thus may have lower depression during selfish and prosocial lying. This suggests that rejection avoidance and praise seeking may modulate the relationship between lying and depression not only independently but also in complex interactions. Thus, we aimed to clarify how these interactions contribute to the complexity of the relationship between lying and depression and to provide a more nuanced understanding of these dynamics in adolescence.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

Our sample consisted of adolescents between the ages of 15 and 18. We believed this age range was the most appropriate to examine the questions of this study, as adolescents in this period are particularly sensitive to their own reputations (Blakemore, 2018; Tomova et al., 2021) and are the most likely to lie (Debey et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2004; Levine et al., 2013). We conducted a power analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.4 (Faul et al., 2007) to determine the sample size prior to beginning data collection. We estimated that a minimum sample size of 688 participants would be required to detect small effects (effect size f = 0.02, alpha level = 0.05, power = 0.80, number of tested predictors = 6, total number of predictors = 14). For the number of tested predictors, we entered 6 variables (rejection avoidance × selfish lying, rejection avoidance × prosocial lying, praise seeking × selfish lying, praise seeking × prosocial lying, rejection avoidance × praise seeking × selfish lying, and rejection avoidance × praise seeking × prosocial lying) that correspond to the hypotheses of this study. We collected data from 1,400 Japanese high school students between the ages of 15 and 18 (700 males and 700 females; Mage = 16.58, SD = 1.12) who were registered with an online survey company (Freeasy; iBRIDGE Company, Tokyo, Japan).

2.2 Procedure

This study recruited participants through the online survey company. The study collected data on reputational concerns, lying, and depression using self-report measures. The study also measured age and gender as control variables, as age and gender differences in reputational concerns, lying, and depression have been shown (Levine et al., 2013; Shorey et al., 2022; Tomova et al., 2021). The study was approved by [ethics review committee masked for blind review] and was conducted after obtaining informed consent from participants and their parents. Participants were paid for their participation by the online survey company.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Reputational concerns

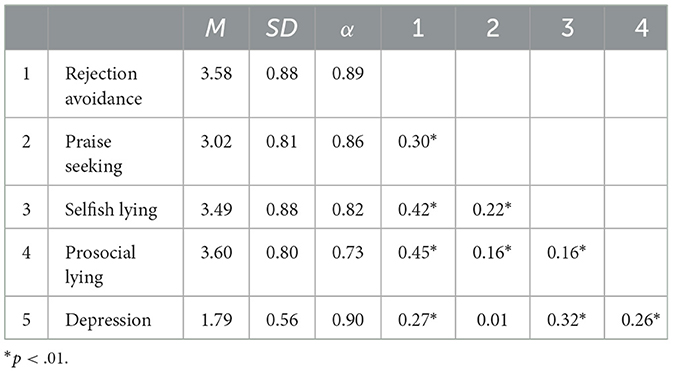

To assess rejection avoidance and praise seeking, we used the rejection avoidance and praise seeking need scales (Kojima et al., 2003). Overall, 18 items were rated using a 5-point rating scale (1 = disagree to 5 = agree). The alpha coefficients for each factor were as follows and were similar to Kojima et al. (2003): rejection avoidance: α = 0.89 and praise seeking: α = 0.86.

2.3.2 Lying

To assess selfish and prosocial lying, we used the selfish and prosocial lying scales (Taguchi, 2022). Overall, 14 items were rated using a 6-point rating scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). The alpha coefficients for each factor were α = 0.82 for selfish lying and α = 0.73 for prosocial lying, similar to Taguchi (2022).

2.3.3 Depression

To assess depression, we used the Japanese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Shima et al., 1985; original English version, Radloff, 1977). Using a 4-point scale, 20 items were rated (1 = not at all to 4 = often). Similar to Radloff (1977), the alpha coefficient of the scale was α = 0.90.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using R version 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2021) and the R packages “dplyr”, “here”, “psych”, “gvlma”, “MASS”. We determined exclusion criteria before the analysis. Exclusion criteria were established prior to analysis. We excluded data from 378 participants who failed the attention task (i.e., “Please answer '2′ for this item.”) and analyzed data from the remaining 1,022 Japanese high school students aged 15 to 18 years (474 males and 548 females; Mage = 16.59, SD = 1.13). In this study, gender was coded as a binary variable (0 = male, 1 = female).

First, we calculated correlation coefficients between the scales. Second, we conducted a multiple regression analysis with depression as the dependent variable. The independent variables included rejection avoidance, praise seeking, selfish lying, prosocial lying, and their interactions (rejection avoidance × praise seeking, selfish lying × prosocial lying, rejection avoidance × selfish lying, rejection avoidance × prosocial lying, praise seeking × selfish lying, praise seeking × prosocial lying, rejection avoidance × praise seeking × selfish lying, and rejection avoidance × praise seeking × prosocial lying). Age and gender were also included as covariates. All independent variables were mean centered. We formally tested the regression models for violations of important assumptions using “gvlma” package. Our data had issues with skewness and kurtosis, so we applied robust linear regression to address these violations. Previous studies have shown that the R2 statistic is not appropriate for assessing the fit of robust linear regressions (Willett and Singer, 1988). Therefore, we do not report it. We determined the significance of associations using bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CIs) rather than p-values. The 95% confidence intervals were calculated using a bootstrap with 10,000 bootstrap replicates. For significant interactions, simple slopes were calculated one standard deviation below and one standard deviation above the mean of the moderator variable, following recommendations for continuous variables (Aiken and West, 1991).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the correlation coefficients among all scales. Rejection avoidance was positively correlated with praise seeking, selfish lying, prosocial lying, and depression. Praise seeking was also positively correlated with rejection avoidance, selfish lying, prosocial lying, and depression.

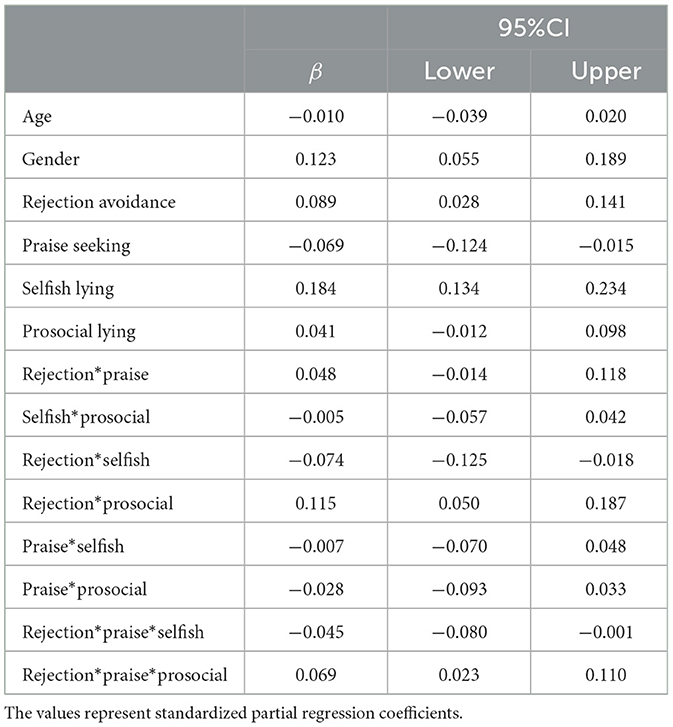

3.2 Multiple regression analysis

To determine whether reputational concerns moderated the relationship between lying and depression, we conducted a multiple regression analysis (Table 2). Results indicated that main effects of gender (β = 0.123), rejection avoidance (β = 0.089), praise seeking (β = −0.069), selfish lying (β = 0.184) were significant. Gender, rejection avoidance, and selfish lying positively predicted depression, whereas praise seeking negatively predicted depression. In addition, the interaction terms for rejection avoidance × selfish lying (β = −0.074), rejection avoidance × prosocial lying (β =0.115), rejection avoidance × praise seeking × selfish lying (β = −0.045), and rejection avoidance × praise seeking × prosocial lying (β = 0.069) were also significant.

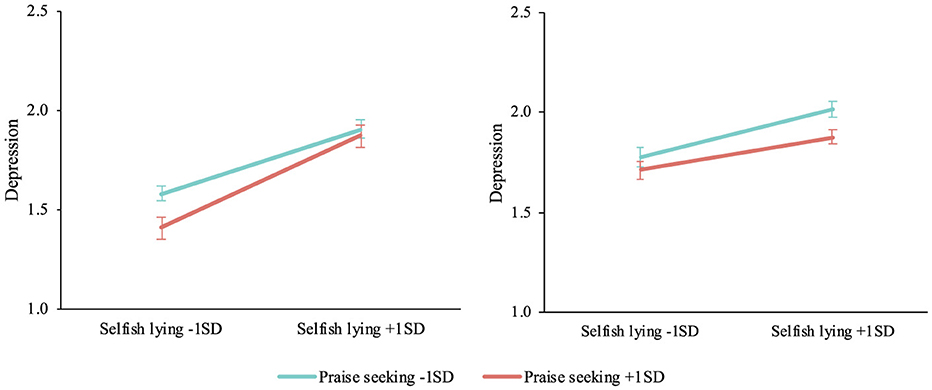

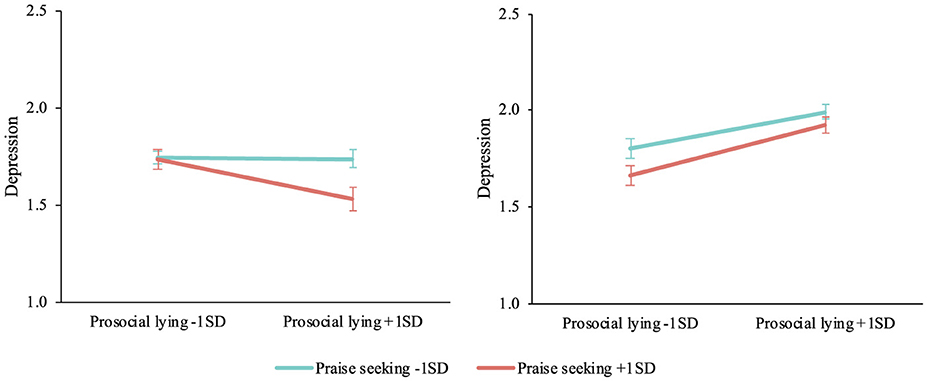

Results of the simple slope analysis for the interaction of rejection avoidance × praise seeking × selfish lying are presented in Figure 1 and for the interaction of rejection avoidance × praise seeking × prosocial lying in Figure 2. Simple slope analysis revealed that for all cases of rejection avoidance −1SD and praise seeking −1SD (β = 0.351, 95%CI [0.219, 0.497]), rejection avoidance −1SD and praise seeking +1SD (β = 0.433, 95%CI [0.266,0.571]), rejection avoidance +1SD and praise seeking +1SD (β = 0.128, 95%CI [0.012,0.246]), and rejection avoidance +1SD and praise seeking −1SD (β = 0.246, 95%CI [0.110, 0.391]), those with higher levels of selfish lying reported more depression than those with lower levels. In addition, the results indicated that for rejection avoidance + 1SD and praise seeking −1SD (β = 0.166, 95%CI [0.041, 0.323]) and rejection avoidance +1SD and praise seeking +1SD (β = 0.241, 95%CI [0.104, 0.393]), those with higher tendencies toward prosocial lying exhibit higher levels of depression. Conversely, for rejection avoidance −1SD and praise seeking +1SD (β = −0.190, 95%CI [−0.351, −0.026]), those with higher tendencies toward prosocial lying exhibit lower levels of depression. There was no association between prosocial lying and depression for rejection avoidance −1SD and praise seeking – 1SD (β = 0.015, 95%CI [−0.108, 0.149]).

Figure 1. Three-way interaction effects of rejection avoidance × praise seeking × selfish lying on depression. Left: rejection avoidance −1SD, right: rejection avoidance + 1SD. Error bars indicate standard error.

Figure 2. Three-way interaction effects of rejection avoidance × praise seeking × prosocial lying on depression. Left: rejection avoidance −1SD, right: rejection avoidance + 1SD. Error bars indicate standard error.

4 Discussion

This cross-sectional study examined whether reputational concerns moderated the relationship between lying and depression in adolescence. We showed that the relationship between selfish lying and depression was not moderated by either rejection avoidance or praise seeking. In contrast, we found that the relationship between prosocial lying and depression was moderated by both rejection avoidance and praise seeking. Specifically, when both rejection avoidance and praise seeking were high, and when rejection avoidance was high and praise seeking was low, those with higher tendencies toward prosocial lying had higher levels of depression. In contrast, when rejection avoidance was low and praise seeking was high, those with higher tendencies toward prosocial lying had lower levels of depression.

This study demonstrated that reputational concerns moderate the relationship between lying and depression. First, we showed that the effects of selfish lying on depression were not moderated by reputational concerns (rejection avoidance and praise seeking). Specifically, those with higher tendencies toward selfish lying also tend to exhibit higher levels of depression, regardless of their level of rejection avoidance or praise seeking. This suggests that selfish lying has a consistently negative impact on an individual's psychological health. The feelings of guilt and self-discrepancy that result from lying seem to increase depressive symptoms, regardless of the individual's level of reputational concern. This supports and extends the findings of Dykstra et al. (2020a,b). In contrast, we showed that the effect of prosocial lying on depression was moderated by reputational concerns (rejection avoidance and praise seeking). Specifically, when rejection avoidance and praise seeking were both high or when rejection avoidance was high and praise seeking was low, those with higher tendencies toward prosocial lying had higher levels of depression, whereas when rejection avoidance was low and praise seeking was high, those with higher tendencies toward prosocial lying had lower levels of depression. This suggests that the effect of prosocial lying on depression is complexly moderated by reputational concerns. Our results thus suggest that regardless of the level of praise seeking, individuals with high rejection avoidance can experience an increase in depression when lying even for prosocial reasons. This finding is important as it suggests that high rejection avoidance can have negative psychological consequences when combined with lying, including prosocial lying. On the other hand, when praise seeking was high and rejection avoidance was low, prosocial lying was associated with a lower level of depression. This suggests that individuals who are both more likely to seek positive evaluations from others and less concerned with negative evaluations may experience beneficial effects from prosocial lying. These individuals may maintain psychological health by facilitating relationships with others and maintaining a positive self-image through prosocial lying. These findings suggest that lying and its psychological consequences in adolescence vary greatly depending on individual differences in reputational concerns. In particular, the effects of prosocial lying can be both positive and negative depending on the balance of an individual's reputational concerns. These results extend previous findings that lying increases depression (e.g., Dykstra et al., 2020a). However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as they are based on an exploratory analysis of three-way interactions and lack a strong a priori theoretical justification. These results need to be validated and their implications clarified through further research.

This study has several limitations. First, the participants in this study were limited to adolescents aged 15 to 18 years. Future studies should examine whether our findings are specific to adolescents by examining a broader age range. Second, this study relied on self-report measures and cannot rule out the possibility that social desirability influenced participants' responses to the questionnaire. For example, participants with higher levels of reputational concern may have underreported lying. This potential for systematic reporting bias may have led to an underestimation of the relationship between reputational concerns, lying, and depression. Future research should examine whether the results of this study can be replicated by measuring actual lying behavior through laboratory and field experiments. Third, this study cannot establish causality because it used cross-sectional design. Future research should use a longitudinal design to determine whether the effects of lying on depression are moderated by reputational concerns. Fourth, we do not consider the multidimensionality of depression. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale used in this study considers depression as a single dimension. However, depression can also be assessed from multiple dimensions, such as emotional, cognitive, somatic, and interpersonal (Cheung and Power, 2012). Future research should consider the multidimensionality of depression and which aspects are related to reputational concerns and lying.

Despite these issues, this study demonstrated that reputational concerns moderate the relationship between lying and depression in adolescence. These results indicate that reputational concerns are complexly related to lying and its negative consequences in adolescence, providing insight into understanding the potential negative effects associated with social development and providing appropriate support during adolescence. Future research should explore how we can use this knowledge to adequately support the healthy development of adolescents who are undergoing significant psychological and social changes.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/hbaut/.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ritsumeikan University Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects (Kinugasa-Human-2024–36). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

RO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants 24K22806 and Research Support Program for Institute of Human Sciences Exploratory Project at Ritsumeikan University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Blakemore, S. J. (2018). Avoiding social risk in adolescence. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 27, 116–122. doi: 10.1177/0963721417738144

Cantarero, K., Van Tilburg, W. A., and Szarota, P. (2018). Differentiating everyday lies: A typology of lies based on beneficiary and motivation. Pers. Individ. Dif. 134, 252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.013

Cheung, H. N., and Power, M. J. (2012). The development of a new multidimensional depression assessment scale: preliminary results. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 19, 170–178. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1782

Debey, E., De Schryver, M., Logan, G. D., Suchotzki, K., and Verschuere, B. (2015). From junior to senior Pinocchio: a cross-sectional lifespan investigation of deception. Acta Psychol. 160, 58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2015.06.007

DePaulo, B. M., and Bell, K. L. (1996). Truth and investment: lies are told to those who care. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 71, 703–716. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.4.703

DePaulo, B. M., and Kashy, D. A. (1998). Everyday lies in close and casual relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 63–79. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.63

DePaulo, B. M., Kashy, D. A., Kirkendol, S. E., Wyer, M. M., and Epstein, J. A. (1996). Lying in everyday life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 979–995. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.979

Dykstra, V. W., Willoughby, T., and Evans, A. D. (2020a). A longitudinal examination of the relation between lie-telling, secrecy, parent–child relationship quality, and depressive symptoms in late-childhood and adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 438–448. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01183-z

Dykstra, V. W., Willoughby, T., and Evans, A. D. (2020b). Lying to friends: Examining lie-telling, friendship quality, and depressive symptoms over time during late childhood and adolescence. J. Adolesc. 84, 123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.08.003

Engels, R. C., Finkenauer, C., and van Kooten, D. C. (2006). Lying behavior, family functioning and adjustment in early adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 35, 949–958. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9082-1

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

Gerlach, P., Teodorescu, K., and Hertwig, R. (2019). The truth about lies: a meta-analysis on dishonest behavior. Psychol. Bull. 145, 1–44. doi: 10.1037/bul0000174

Gordon, A. K., and Miller, A. G. (2000). Perspective differences in the construal of lies: is deception in the eye of the beholder? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 26, 46–55. doi: 10.1177/0146167200261005

Guzikevits, M., and Choshen-Hillel, S. (2022). The optics of lying: How pursuing an honest social image shapes dishonest behavior. Curr. Opini. Psychol. 46, 101384. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101384

Jensen, L. A., Arnett, J. J., Feldman, S. S., and Cauffman, E. (2004). The right to do wrong: Lying to parents among adolescents and emerging adults. J. Youth Adolesc. 33, 101–112. doi: 10.1023/B:JOYO.0000013422.48100.5a

Kojima, Y., Ohta, K., and Sugawara, K. (2003). Praise seeking and rejection avoidance need scales: development and examination of validity. Jap. J. Personal. 11, 86–98. doi: 10.2132/jjpjspp.11.2_86

Levine, E. E., and Lupoli, M. J. (2022). Prosocial lies: causes and consequences. Curr. Opini. Psychol. 43, 335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.006

Levine, E. E., and Schweitzer, M. E. (2014). Are liars ethical? On the tension between benevolence and honesty. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 53, 107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2014.03.005

Levine, E. E., and Schweitzer, M. E. (2015). Prosocial lies: When deception breeds trust. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 126, 88–106. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.10.007

Levine, T. R., Serota, K. B., Carey, F., and Messer, D. (2013). Teenagers lie a lot: a further investigation into the prevalence of lying. Commun. Res. Reports 30, 211–220. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2013.806254

Naragon-Gainey, K. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relations of anxiety sensitivity to the depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychol. Bull. 136, 128–150. doi: 10.1037/a0018055

Nowak, M. A., and Sigmund, K. (2005). Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature 437, 1291–1298. doi: 10.1038/nature04131

Preuter, S., Jaeger, B., and Stel, M. (2024). The costs of lying: Consequences of telling lies on liar's self-esteem and affect. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 63, 894–908. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12711

R Core Team (2021). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

Schweitzer, M. E., Hershey, J. C., and Bradlow, E. T. (2006). Promises and lies: Restoring violated trust. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 101, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.05.005

Shima, S., Shikano, T., Kitamura, T., and Asai, M. (1985). New self-rating scale for depression. Clini. Psychiat. 27, 717–723. (In Japanese with English abstract.)

Shorey, S., Ng, E. D., and Wong, C. H. (2022). Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clini. Psychol. 61, 287–305. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12333

Smetana, J. G., Villalobos, M., Tasopoulos-Chan, M., Gettman, D. C., and Campione-Barr, N. (2009). Early and middle adolescents' disclosure to parents about activities in different domains. J. Adolesc. 32, 693–713. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.010

Taguchi, K. (2022). Prosocial lying and depressive mood: friendship as a mediator discriminating between adjusted and maladjusted function. Jap. J. Personal. 31, 102–111. doi: 10.2132/personality.31.2.4

Tomova, L., Andrews, J. L., and Blakemore, S. J. (2021). The importance of belonging and the avoidance of social risk taking in adolescence. Dev. Rev. 61:100981. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2021.100981

Warr, M. (2007). The tangled web: delinquency, deception, and parental attachment. J. Youth Adolesc. 36, 607–622. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9148-0

Keywords: reputational concerns, rejection avoidance, praise seeking, lying, selfish lying, prosocial lying, depression, adolescence

Citation: Oguni R and Taguchi K (2025) Reputational concerns moderate the relationship between lying and depression. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2:1513617. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2024.1513617

Received: 18 October 2024; Accepted: 24 December 2024;

Published: 14 January 2025.

Edited by:

Jordan Ashton Booker, University of Missouri, United StatesReviewed by:

Rashid Baloch Shar, Indus University, PakistanRichard Fabes, Arizona State University, United States

Cynthia Guo, Harvard University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Oguni and Taguchi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ryuji Oguni, b2d1bmlAZmMucml0c3VtZWkuYWMuanA=

Ryuji Oguni

Ryuji Oguni Keiya Taguchi

Keiya Taguchi