- School of Family Life, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, United States

Introduction: The current study examined adolescents’ nonprejudiced values toward sexual minorities over three years to determine change over time, as well as parenting and child characteristics as predictors of initial levels and change in values over time.

Methods: Participants included 573 US adolescents (M age at Wave 1 = 14.56, SD = 1.68, range 12–17; 49% identifying as female; 82% completely heterosexual) and their mother (n = 573, 83% completely heterosexual) and father (n = 341, 99% completely heterosexual), all of whom responded to surveys given annually over three years, starting in 2020.

Results: Growth curve analysis suggested that adolescents’ nonprejudiced values toward sexual minorities increased from ages 14–16 for both males and females. Results also suggested that both maternal and paternal teaching of nonprejudiced values were consistent predictors of initial levels of adolescent nonprejudiced values, and mothers’ teaching was associated with increases in nonprejudiced values over time, over and above other parenting variables like parental warmth and frequency of parental communication about sexual minority topics.

Discussion: The discussion focuses on the importance of parental teaching of nonprejudiced values on the development of adolescents’ own nonprejudiced values.

Introduction

Despite increasing societal acceptance (Stuart-Maver et al., 2023), sexual minorities (SM) continue to be the victims of prejudice, or hostile attitudes and behavior aligned with society’s negative regard (i.e., stigma) toward non-heterosexuals (Herek, 2016). Sexual prejudice may be complicit in SM experiencing greater mental health challenges (Feinstein et al., 2023), additional stressors and discrimination (Gordon et al., 2024), and generally less societal power (Herek, 2016) than their non-SM peers. Despite evidence of rampant sexual prejudice (Mevissen et al., 2018), not all people exhibit prejudice toward SM (Herek, 2016), and instead may be internally motivated to respond without prejudice due to personal moral standards of nonprejudice (Plant and Devine, 1998; van Nunspeet et al., 2015). Existing research has demonstrated that prejudice begins at home (Allport, 1954; Degner and Dalege, 2013), and is socialized throughout a person’s childhood and beyond (Váradi et al., 2021), yet little is known about how nonprejudiced moral values are socialized.

Previous research has demonstrated that people prioritize behaving in ways congruent with personal moral values shared by their ingroup (van Nunspeet et al., 2015), and that families may function as a type of ingroup (McConnell et al., 2019). Thus, parents who teach their children to be nonprejudiced toward SM may be acting as ingroup moral models for their children, thereby promoting prosocial attitudes and elevated moral feelings toward SM (Telesca et al., 2024). Since evidence suggests that adolescence is a fundamental developmental period when prejudice toward outgroups may solidify (Miklikowska, 2016; Váradi et al., 2021), it is important to also examine the development of nonprejudice during adolescence. Understanding nonprejudiced patterns and predictors may help scholars identify the most proactive, intentional leveraging points that support the crystallization of nonprejudice toward SM during adolescence (Váradi et al., 2021). Thus, in the current study we looked at adolescent nonprejudiced values toward SM over 3 years to determine change over time, and we explored parenting and child characteristics as predictors of initial levels and change in values over time.

The development of prejudice toward sexual minorities

Humans tend to categorize themselves into social groups that maximize similarities (Nam and Chen, 2022), thus creating ingroups (one’s membership group) and outgroups (non-membership groups; Hewstone et al., 2002). Social psychologists have demonstrated that the mere presence of ingroups and outgroups triggers discrimination toward the outgroup (Tajfel et al., 1979) due to intergroup bias (Hewstone et al., 2002), or the tendency to esteem the ingroup over the outgroup (Tajfel et al., 1979). Given the human propensity to create social groups (Tajfel et al., 1979), the term “sexual minority” effectively describes the marginalized outgroup experience of those individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and beyond (LGBTQ+).

Theoretical frameworks such as Allport’s (1954) intergroup contact theory emerged in an effort to define and address the prevalence of prejudice (specifically racial) and its origins, and was later expanded to include sexual prejudice (originally termed homophobia; Weinberg, 1972; Herek, 2004). Allport provided a definition of prejudice (i.e., superiority of one group over another derived from misconceptions, limited contact, or exaggerated stereotypes; Allport, 1954; Hecht, 1998), as well as its counter, which is tolerance. Tolerance was defined as one’s affiliation, acceptance, and respect of people regardless of social groupings (Allport, 1954), with more recent conceptualizations of the definition including the conscientious effort to reject or correct biased attitudes, beliefs, and discriminatory behavior (Witenberg, 2019). A person’s internal motivation to respond without prejudice (Plant and Devine, 1998), or being nonprejudiced (Herek, 2016), seems to closely resemble Allport’s definition of tolerance (1954) and the effort to reject bias and discrimination (Witenberg, 2019).

Using intergroup contact theory as a guide, this study will theoretically represent the idea of tolerance by focusing on nonprejudiced values (Herek, 2016). Although prior work has identified limitations of intergroup contact such as failure to consider the structural and systemic context in which interactions occur (e.g., the majority-minority composition of one’s environment; Dixon, 2006), as well as individual-level characteristics that can shape the nature of intergroup contact (McMillan et al., 2023; Veenstra et al., 2013), intergroup contact theory provides a framework to examine how the development of morals (specifically regarding prejudice and nonprejudice) and group identity in childhood and adolescence may result in full-fledged prejudice in adulthood (Rutland and Killen, 2015). Empirical research has found that prejudice develops early in young children, reaches a peak in middle childhood (5–7 years), tapers down slightly in late childhood (8–10 years; Raabe and Beelmann, 2011), and remains quite stable throughout adolescence, although at varying levels for different individuals (Crocetti et al., 2021). However, we know little about the development of nonprejudiced values (or tolerance) toward SM during adolescence. Thus, the current study explored the development of nonprejudiced values toward SM during middle adolescence (ages 14–16), and variables that might be associated with initial levels and changes in nonprejudice over time, including parenting, gender stereotypes, and prosocial behavior.

Parent predictors of nonprejudiced values

Parental teaching of nonprejudiced values

Scholars posit that prejudice is socialized at home (Allport, 1954) from an early age (Herek, 2007), and that parent messages may shape their children’s prejudiced or nonprejudiced attitudes (Pahlke et al., 2021). Similarly, Allport (1954) related tolerance and prejudice socialization (specifically from parents to children) as consisting of two processes: first, a direct transfer of outgroup attitudes through parents’ words and gestures; and second, the family atmosphere parents create which implicitly communicates attitudes of prejudice or tolerance to children (Odenweller and Harris, 2018). This has since been supported by findings which indicate parents and children do tend to share similar beliefs and moral orientations (Kil et al., 2023), which could include the moral ideal of nonprejudice (van Nunspeet et al., 2015). Thus, in the current study we sought to determine if parental self-reported teaching of nonprejudiced values was associated with adolescents’ nonprejudiced values over and above other common correlates, including parental warmth and parental communication.

Parental warmth

Research on parental warmth has consistently established protective associations between warmth and a variety of positive adolescent outcomes (e.g., Khaleque, 2013; Liu et al., 2020; Pinquart, 2017a, 2017b). Parental warmth is associated with secure attachment styles in adolescence (Brown and Whiteside, 2008), and, apropos to this study, evidence suggests that securely attached adolescents display the lowest levels of prejudice (Di Pentima and Toni, 2009). Additionally, parental warmth provides an environment where children are more likely to internalize parental attitudes (Jaspers et al., 2008), suggesting that parental warmth facilitates the reinforcement of parental attitudes in the child, including parental prejudiced attitudes (Jaspers et al., 2008; Miklikowska, 2016; Zagrean et al., 2022). Thus, we suspected that parental warmth would be positively associated with adolescent nonprejudiced values, as parental warmth is well established as an aspect of the parent–child relationship that models prosocial responding and emotions and creates a positive environment for the internalization of values (Padilla-Walker, 2014).

Parent–child communication about sexual minorities

Much research has also been done supporting the importance of parent–child sex communication on adolescent sexual outcomes (for a review, see Flores and Barroso, 2017). Although a majority of parent–child sex communication has traditionally focused on sexual risk reduction topics (e.g., HIV/AIDs; Rogers et al., 2022) as parents prioritize sexual safety for their children (Butts et al., 2018), communication topics that promote sexual health in adolescents are necessarily broader than only risk reduction (e.g., positive aspects of sexuality; Rogers et al., 2022), and can also include discussion of non-heterosexual identities (Flores and Barroso, 2017). That being said, evidence suggests that parents do not frequently talk about sexual minorities with their children (Calzo and Ward, 2009), despite adolescents’ reporting these topics as important (Flores and Barroso, 2017). Aligned with the positive effects of most parent–child sex communication (Flores and Barroso, 2017), it could be that parental communication about sexual orientation would be associated with nonprejudice in adolescents (Herek, 2016), especially when parental messages are positive or neutral regarding sexual minorities (Harkness and Israel, 2018). Therefore, in the current study we suspected that frequency of sex communication about sexual minorities would be positively associated with adolescent nonprejudiced values, although we were unsure of the strength of this relation given sex communication provides no indication of tone or quality of the conversation, and could be indicative of a high level of prejudice or nonprejudice communication.

Parental endorsement of gendered sexual scripts

Families are often the first source of sexual information for children (Flores and Barroso, 2017), providing the earliest exposure to and imprinting of sexual script beliefs (Leonhardt et al., 2019), which can be thought of as behavioral expectations of how to think and act regarding sexuality (Rossetto and Tollison, 2017). For instance, Stanaland et al. (2024) found that parents’ endorsement of hegemonic beliefs about masculinity directly correlated with males pressured motivation to conform to gender typicality and that adolescent males were likely to respond with aggression when they perceived a threat to their masculinity. Similarly, gendered sexual script beliefs (Trinh et al., 2014) set expectations and social norms for certain gendered behaviors in sexual relationships (Ward et al., 2022), tend to be hegemonic in nature (Masters et al., 2013), and reinforce heteronormative relationships as normal (Rossetto and Tollison, 2017). These gender stereotype beliefs contribute to the reproduction of a heteronormative, gendered sexual script (Ward et al., 2022; Reigeluth and Addis, 2021), and conformity to a gendered sexual script contributes to social norms that reinforce prejudice (Váradi et al., 2021). What is less understood, however, is whether a parent’s own endorsement of gendered beliefs impacts their children’s nonprejudiced values. Given the established relationship between gendered sexual script beliefs and prejudice, we wondered whether there would also be a relationship between how much parents personally endorse a gendered sexual script and whether that endorsement impacts their adolescent’s nonprejudiced values. Thus, we investigated how parental endorsement of gendered sexual script beliefs may be related to the development of adolescents’ nonprejudiced values.

Adolescent predictors of nonprejudiced values

Adolescent masculinity beliefs

Allport (1954) suggested that conforming to social norms was a key ingredient in the development of prejudiced attitudes. Traditional masculinity beliefs are one such social norm that reinforces prejudicial attitudes (Váradi et al., 2021). Traditional masculinity ideology (Rogers et al., 2017) includes stereotypes of what it means to be masculine, which could include being aggressive and competitive (Ward et al., 2022), and is associated with heterosexual men reporting more negative attitudes than others toward SM, SM behavior, and SM civil rights (Kite et al., 2021). For instance, masculine norms contribute to gender policing (i.e., harassment that targets nonconforming gender expression) commonly exhibited in the form of bullying during adolescence (Mittleman, 2023), thus reinforcing masculinity expectations through verbal, physical, and “boy code” dimensions (Reigeluth and Addis, 2021). While masculinity norms are perceived as more relevant for men than for women (Wong et al., 2016), evidence suggests that females also feel pressure to adhere to masculinity beliefs (Rogers et al., 2020), although no existing research has yet linked female masculinity norm adherence to prejudice. However, female social costs for enacting masculinity (e.g., dressing in more masculine fashions) may be lower than for males enacting femininity (Mittleman, 2023), due to a patriarchal society that pedestalizes masculinity over femininity (Rogers et al., 2020). Whereas masculinity beliefs and prejudice are associated in nuanced ways, what is not yet understood in the extant literature is how adolescent masculinity beliefs may be related to adolescent nonprejudiced values for both males and females. We theorize that less adherence to masculinity norms may be associated with higher endorsement of nonprejudiced values, although this may vary by gender given the social costs. Thus, in this study, we explored the role of adolescent masculinity beliefs in the development of nonprejudiced values.

Adolescents’ prosocial behavior

Moral development may assist a developing child or adolescent in considering what is unjust and unfair about prejudice toward others (Rutland and Killen, 2015), and includes prosocial behaviors as an indicator of moral identity development during adolescence (Carlo and Padilla, 2020). Specifically, prosocial behaviors refer to actions that are intended to help others (Eisenberg et al., 2016), and may encompass different dimensions, such as prosocial motives, context, and targets (e.g., prosocial behavior toward friends, family, or strangers; Carlo and Padilla, 2020). Prosocial behavior also includes behaviors reflecting tolerance and inclusion. Research has shown an inverse relationship between prosocial behavior and discrimination against sexual minorities (Srimuang and Pholphirul, 2023) and in one study of Latino/a adolescents, discrimination was associated with less altruistic prosocial behavior (Davis et al., 2021). Given the evidence suggesting that prosocial behaviors may be associated with less discrimination, it is important to explore whether adolescents’ self-reported prosocial behavior may also predict adolescent nonprejudiced values. Therefore, this study investigated adolescents’ self-reported prosocial behavior toward three different targets (i.e., friends, family, strangers), and how these might be related to the development of nonprejudiced values.

Current study

Taken together, the current study sought to explore two main research questions. First, how do adolescents’ nonprejudiced values toward SM develop from age 14–16? Based on existing research on the development of prejudice (Crocetti et al., 2021), we expected that perhaps levels would remain stable over time, but this question was largely exploratory. The second research question was how parenting (parental teaching of nonprejudiced values, parental warmth, parent–child communication about sexual minority topics and parental endorsement of gendered sexual scripts) and child characteristics (masculinity beliefs and prosocial behavior) were associated with initial levels and change in adolescents’ nonprejudiced values over time. We expected that parental teaching of nonprejudice would be positively associated with adolescents’ values over and above parental warmth and communication. We also expected parents’ endorsement of gendered sexual scripts and adolescents’ masculinity beliefs to be negatively associated with nonprejudice toward SM. Finally, we expected that adolescents’ prosocial behavior would be positively associated with nonprejudiced values.

We also considered demographic variables that might be associated with the development of nonprejudiced values. Given the focus of this study on nonprejudiced values toward sexual minorities, who could be considered an outgroup in a heteronormative society (Herek, 2016), sexual orientation for both parents and adolescents seemed important to include as covariates in this study. Second, religiosity is often deeply implicated with sexual prejudice (Herek, 2016), and negative attitudes toward members of the SM community have been associated with higher religiosity (for women; Gibbs and Goldbach, 2021). However, a recent meta-analysis suggests that religiosity can be protective for SM youth (Lefevor et al., 2021), and religiosity is associated with kindness and prosocial behavior during adolescence (Hardy and Carlo, 2005), suggesting potentially complex relations between religiosity and nonprejudice. Thus, we explored sexual orientation of both parents and children, and parent and child religiosity as potential correlates of nonprejudiced values.

Methods

Participants

Participants for this study included 573 US adolescents (49% identifying as females, 50% identifying as males, 1% identifying as non-binary; 1.6% transgender; 82% completely heterosexual; 6% mostly heterosexual, 8% bisexual, 3% gay/lesbian, and 1% other (e.g., pansexual, asexual); 56% white, 20% black, 10% Latino/a, 14% biracial/other; M age at Wave 1 = 14.56, SD = 1.68, range 12–17; M age at Wave 2 = 15.58, SD = 1.72; M age at Wave 3 = 16.39, SD = 1.76), their mother (n = 573, 83% completely heterosexual) and father (n = 341, 99% completely heterosexual). Forty-seven percent of mothers were currently single, not married, with 44% of mothers never married to the child’s biological father and 15% divorced from the child’s biological father. Twenty-nine percent of fathers were currently not married to the child’s biological mother, and 7% were divorced from the child’s biological mother. In terms of education, 24% of mothers had a high school diploma, 50% had some college, 20% graduated college, and 5% had a graduate degree. Among fathers, 43% had a high school diploma, 36% had some college, 17% had graduated college, and 4% had a graduate degree. The average yearly income of mothers was between 35 and 50,000 USD and fathers between 50 and 75,000 USD.

Procedures

Participants came from Waves 1, 2, and 3 of the Healthy Sexuality Project, which is a longitudinal study focused on parent-adolescent sex communication and healthy sexual development. Data were collected in early 2020 after receiving IRB approval from the sponsoring institution (IRB # F2019-342), and approximately 1 year later for each subsequent year (longitudinal response rate was approximately 75%). For the first wave of data collection, mothers were recruited using a third-party research service called Bovitz®, which retains a national panel of research participants gathered through digital advertising channels (e.g., social media, search engines) and address-based sampling methods (e.g., mailing lists). A stratified random sample of this panel was drawn using national quotas for gender, racial/ethnic identity, and parent education. Quotas were reached on parental education and child gender, but not on race/ethnicity (Latino/a and Asian were under-represented and Black was over-represented). The sample size was determined by estimating the power needed to conduct analyses separately as a function of the child’s gender and parental education. Mothers agreed to participate with their adolescent child who was between the ages of 12–17, and with the child’s father-figure whenever possible. In subsequent waves, we contacted participants directly with the contact information provided at Wave 1.

After being informed that the study concerned parent-adolescent sex communication and agreeing to participate, at each wave participants completed a 30-min online survey (via Qualtrics) including a variety of measures related to parent–child sex communication, the parent–child relationship, and adolescents’ sexual behavior. At the initial time point each participant was compensated $20. At subsequent waves each participant was compensated $35 if all three family members completed their survey within the first 2 weeks of data collection, and they were compensated $20 each after that point. Because participants were not compensated if they did not pass questions strategically placed in the questionnaire to ensure attention (e.g., if you are reading this, please choose “sometimes”), we are confident in accurate data and there were very few instances of missing data. That being said, missing data were addressed using full information maximum likelihood in MPLUS. It is also of note that four families were excluded from analyses because they had two mother-figures (and no father-figure), and we did not have adequate power to accurately determine differences for this group.

Measures

Parent and adolescent nonprejudiced values

Parents’ self-reported teaching of nonprejudiced values toward LGBTQ+ individuals and adolescents’ own self-reported nonprejudiced values toward LGBTQ+ individuals were assessed using four items (α = 0.80–0.83) adapted from a measure of nonprejudice toward ethnic minorities (Plant and Devine, 1998). Participants responded to these items using a five-point Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). One item was reverse coded, such that higher scores reflected a stronger belief in nonprejudice toward sexual minorities. Sample item includes “I teach my child to be nonprejudiced toward LGBT individuals” (see Supplementary materials for full scale).

Parental warmth

Adolescents reported on maternal and paternal warmth using three items (α = 0.84–0.91) from the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ; Robinson et al., 2001). Adolescents rated how often behaviors were exhibited by the parent using a Likert scale of 1 (never) to 5 (always), with higher scores reflecting higher parental warmth. A sample item includes “My parent gives comfort and understanding when I am upset.”

Parent–child communication about sexual minorities

Parents rated how often they talked with their child about topics related to sexuality in the past year using a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 6 (more than once a week), with higher scores reflecting higher frequency of communication (adapted from Rogers et al., 2022). For the current study, two items were averaged as an indication of the frequency with which parents talked with their child about sexuality related to LGBTQ issues (e.g., what it means to be transgender, what it means to experience same-sex attraction/be LGBTQ).

Parental endorsement of gendered sexual scripts

Parents’ endorsement of gendered sexual scripts was assessed using seven items (α = 0.82–0.83) developed by Trinh et al. (2014). Participants responded to these statements using a five-point Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher levels reflected a higher endorsement of a gendered sexual script. Sample items include, “It is up to women to limit the sexual advances of men and keep men from ‘going too far’” and “It is difficult for males to resist their sexual urges.”

Adolescent masculinity

Adolescents’ level of agreement about statements regarding traditional masculinity ideology was assessed using an 11-item scale (α = 0.79) developed by Rogers et al. (2017). Respondents rated their agreement to each statement using a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). After reverse coding select items, higher scores represented greater beliefs in traditional masculinity ideology. Sample items include, “I do not let it show to my friends when my feelings are hurt” and “Fighting others is something I have to do to prove myself to my friends.”

Adolescent self-reported prosocial behavior

Adolescents reported on their prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends, and family members using three items for each target (α = 0.84–0.89) based on the Inventory of Strengths (Peterson and Seligman, 2004). Respondents answered using a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not like me at all) to 5 (very much like me). Higher scores reflect higher engagement in prosocial behavior. Sample items for each scale include, “I volunteer in programs to help others in need (like food or clothing drives, working at a homeless shelter),” “I help my friends, even if it is not easy for me,” and “I really enjoy doing small favors for my family.”

Parent and adolescent sexual orientation and religiosity

Adolescents and parents answered one question about their sexual orientation on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (completely homosexual), 3 (bisexual), 5 (completely heterosexual). They were also given an open-ended option to report other sexual orientations. Adolescents and parents responded to one item regarding importance of religiosity asking “How important is religion to you?” on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all important) to 5 (very important).

Results

Descriptive statistics

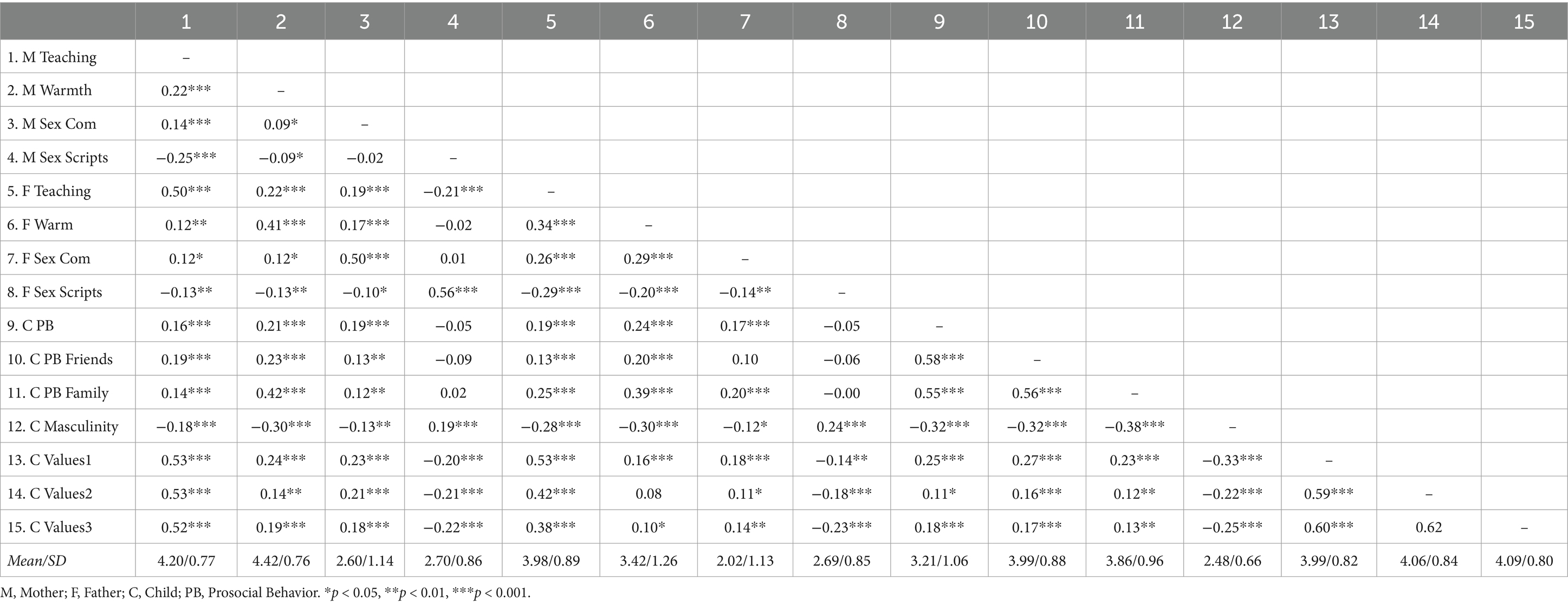

Descriptive statistics and correlations between continuous variables are found in Table 1. It is of note that both maternal and paternal teaching of nonprejudiced values were positively correlated with adolescents’ values at all three time points. Maternal and paternal warmth and communication, and adolescents’ prosocial behaviors were also positively associated with adolescents’ values. Parental sexual scripts and adolescents’ masculinity were negatively associated with adolescents’ nonprejudiced values.

Growth curve of adolescent nonprejudiced values

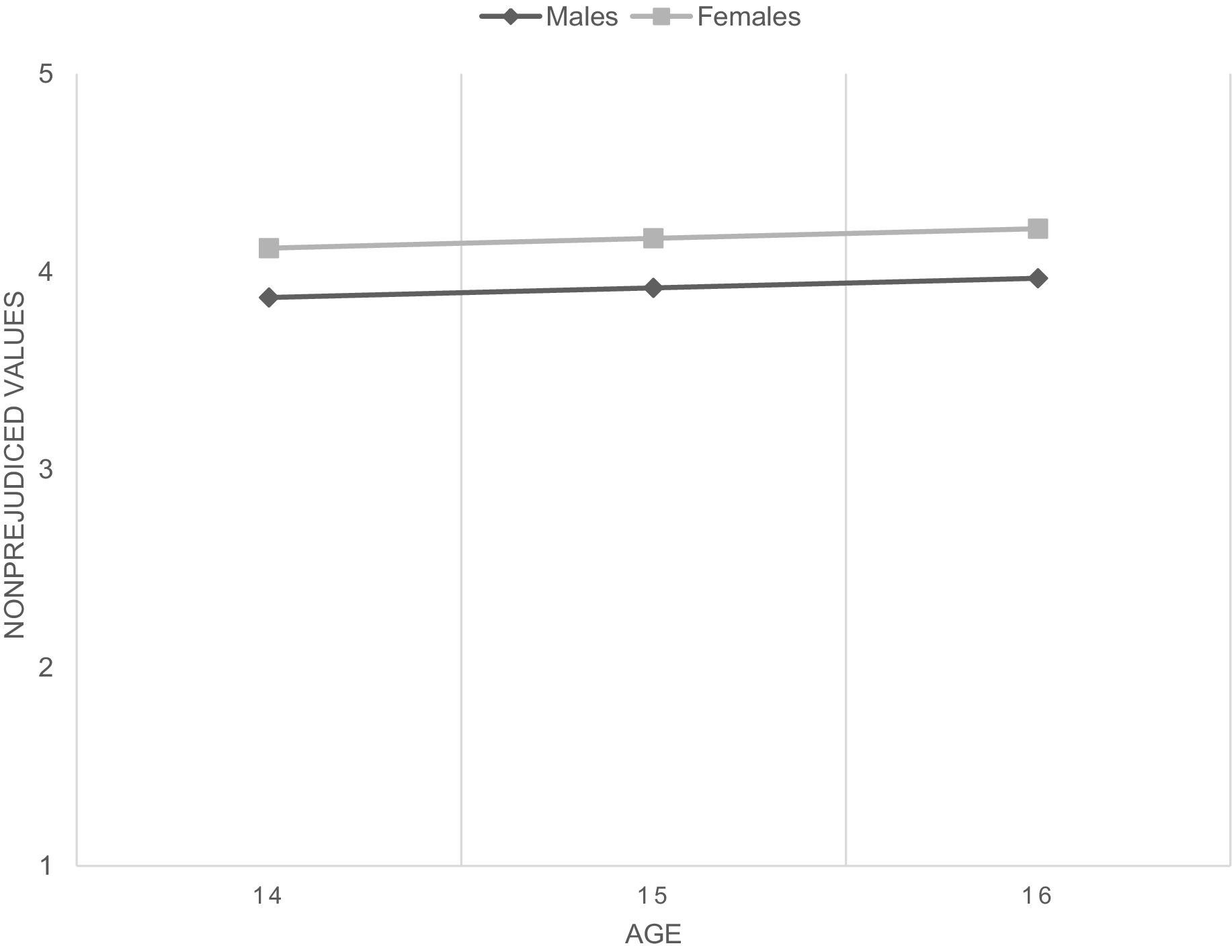

To address our first research question, we conducted a growth curve to assess change in adolescents’ nonprejudiced values over 3 years from Time 1 to Time 3. We constrained the means of the intercept and the slope as a function of the gender of the child in order to determine whether model fit decreased (using a significant Wald test as evidence of decrease in model fit). The Wald test was significant when constraining the mean of the intercepts as a function of gender (Wald = 14.36, p = 0.0002), but not the mean of the slope (Wald = 0.096, p = 0.796), which suggests different starting values in nonprejudice as a function of adolescent gender, but not a difference in change over time. Thus, we ran growth curve models separately by child gender, leaving the intercepts free to vary. The model was fully saturated (X2(5) 4.47, p = 0.486), females had a higher intercept than males (I females = 4.12, p < 0.001, I males = 3.87, p < 0.001), and both had a significant positive slope over time (S = 0.049, p = 0.004). This suggests that females started with higher levels of nonprejudiced values than males at Time1, but the increase in values over time was at a similar rate for male and female adolescents (Figure 1).

Predictors of adolescent nonprejudiced values

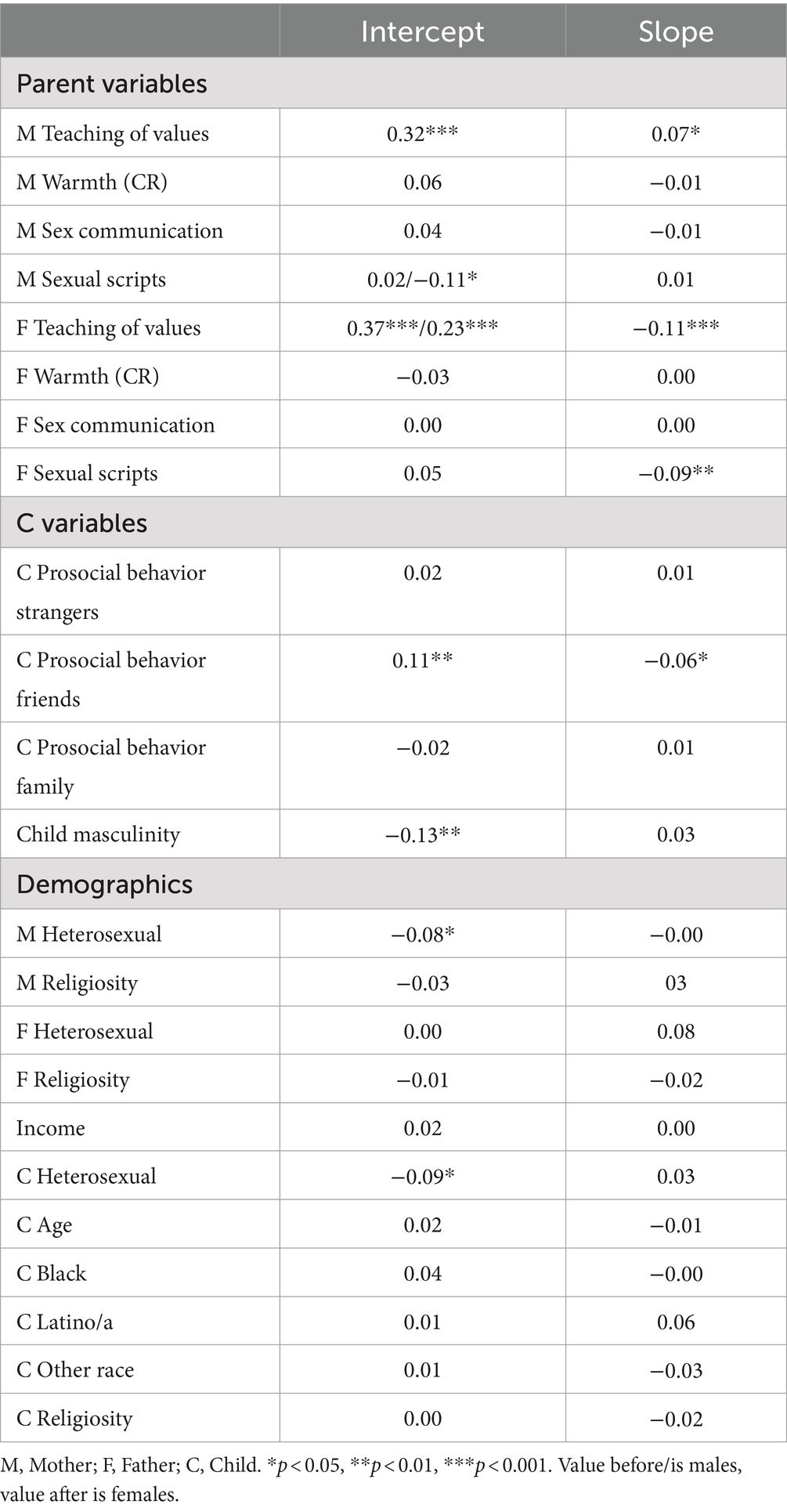

To address our second research question, we explored Time 1 predictors of the intercept and slope of adolescents’ nonprejudiced values, including demographics of the child and the parent, parental nonprejudiced values, more global aspects of parenting (warmth and frequency of sex communication), parental endorsement of gendered scripts, and child characteristics (prosocial behavior and masculinity). We explored predictors separately for females and males, constraining one path at a time to determine which could be constrained to be equal with no decrease in model fit, and which needed to be left free to vary. Based on these analyses, only two paths were left free to vary as a function of child gender, and the rest were constrained to be equal (see Table 2). This suggests that the majority of associations were comparable for male and female adolescents.

The final multiple group model had adequate model fit (X2(95) = 118.23, p = 0.053, CFI = 0.971, RMSEA = 0.029), with the X2 approaching significance likely being a result of the large sample size. In terms of the intercepts, both maternal (b = 0.32, p < 0.001) and paternal (for males, b = 0.37, p < 0.001; for females b = 0.21, p < 0.001) teaching of nonprejudiced values were associated positively with adolescents’ nonprejudiced values. Adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward friends was also positively associated with adolescents’ values (b = 0.11, p = 0.007). Maternal endorsement of gendered sexual scripts (for females only; b = −0.10, p = 0.045), maternal (b = −0.08, p = 0.044) and adolescent heterosexuality (b = −0.09, p = 0.012), and adolescent masculinity (b = −0.13, p = 0.004) were associated negatively with nonprejudiced values.

In terms of slope, maternal teaching of values was associated positively (b = 0.07, p = 0.025) and paternal endorsement of gendered sexual scripts was associated negatively (b = −0.09, p = 0.009) with the slope of child nonprejudiced values. In addition, paternal teaching (b = −0.11, p < 0.001) and adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward friends (b = −0.06, p = 0.028) were negatively associated with slope, but this is likely interpreted by higher intercept values resulting in a less steep positive slope over time.

Discussion

Prejudice may partially explain why members of the SM community experience greater mental health challenges and stressors compared to their non-SM peers (Blashill and Calzo, 2019), including greater rates of suicidality (Stone et al., 2014) mood disorders (Blashill and Calzo, 2019), bullying (Mittleman, 2019), and feeling unsafe at school (Feinstein et al., 2023). Sexual prejudice accords SM less societal power (Herek, 2016), and greater discrimination than their non-SM peers (Gordon et al., 2024). Although the mitigation of sexual prejudice is therefore paramount to the health and safety of all SM, scholars suggest that people must intentionally learn to be nonprejudiced (Herek, 2016). Thus, the goals of the current study were to (1) explore the development of nonprejudiced values across middle adolescence, and to (2) determine if parenting and child characteristics were associated with initial levels and change in values over time.

Development of nonprejudiced values across middle adolescence

The current study found that adolescents’ nonprejudiced values toward SM increased from ages 14–16 for both males and females, with females’ initial levels of nonprejudiced values being higher than were males’. This is somewhat inconsistent with research suggesting that prejudice is relatively stable across adolescence (Crocetti et al., 2021), and suggests some malleability in the development of nonprejudice over time. It will be important for research to explore prejudice toward different groups, as it is possible that prejudice regarding race and ethnicity solidify earlier because racial differences are apparent from an early age (Crocetti et al., 2021), but adolescents may continue to navigate their beliefs and perceptions about sexual minorities into adolescence as sexuality continues to develop and youth explore and disclose their sexual orientation. While this is a possibility, the explanation seems somewhat unlikely, as development in regard to ethnic and racial identity extends into adolescence (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014), suggesting that tolerance toward racial and ethnic minorities could also continue to be shaped.

It seems more plausible that the developmental trajectory of prejudice is simply different from that of nonprejudice (i.e., tolerance; Allport, 1954). In other words, the conscientious effort to reject or correct biased attitudes and behaviors (Witenberg, 2019) increases over time during adolescence, whereas prejudice stays relatively stable across adolescence (Crocetti et al., 2021). It is possible, for example, that increases in nonprejudiced values are a function of the growth in common correlates of tolerance that increase developmentally, such as cognition and perspective taking (Van der Graaff et al., 2014). Although it was outside the scope of this paper to investigate whether an increase in tolerance is associated with a decrease in prejudice, it is encouraging that nonprejudiced moral values increase, rather than matching the trajectory of prejudice.

It would be interesting to explore more fully how nonprejudice develops toward different in-and especially out-group members, and whether there is variability as a function of group membership, or if those who strive to be nonprejudiced do so toward all groups. Existing theory and research suggest that adolescents’ conceptions of both morality (e.g., fairness; Rutland et al., 2023) and group norms influence inclusion, but suggest that perhaps prejudice and nonprejudice are more a function of social identity (e.g., in-group and out-group membership) than moral conviction (Bizumic et al., 2017). Of utmost importance, future research should continue to explore not only the development of nonprejudiced values, but also how these values might be reflected in behaviors that reflect tolerance and inclusion.

Parent and child characteristics associated with nonprejudiced values

The second goal of the current study was to determine whether parent and child characteristics were associated with initial levels or change in nonprejudiced values toward SM over time. Consistent with prior research supporting the importance of parental socialization of values (Kil et al., 2023; Twito-Weingarten and Knafo-Noam, 2023), both maternal and paternal teaching of nonprejudiced values were consistently associated with initial levels of adolescents’ nonprejudiced values, and maternal teaching was associated with increases in nonprejudiced values over time. It is of note that these significant associations were over and above the variance accounted for by parental warmth and the frequency of parental communication regarding SM issues. While the importance of parental teaching is not necessarily a surprising finding, it is an important extension of existing research as it provides support for the important role of parental teaching in the development of nonprejudice values toward SM, specifically. This is also consistent with research suggesting that parental teaching is often directly associated with the development of adolescents’ own internal moral traits or characteristics, such as personal values and moral emotions (Padilla-Walker, 2014), and is indirectly associated with adolescents’ behaviors via these personal traits. Given a need to focus future research on tolerance and inclusion behaviors, not just values, it will also be important to explore other mechanisms at play in this process and how they might increase nonprejudiced behaviors, including established correlates such as adolescents’ empathic concern or perspective taking toward sexual minorities.

Findings also suggested that parental endorsement of gendered sexual scripts (mothers on the intercept of daughters only, fathers on the slope), adolescents’ masculinity values, and mothers’ and adolescents’ heterosexual orientation were negatively associated with adolescents’ nonprejudiced values. It is of note that masculinity values were negatively associated with adolescents’ nonprejudiced values for both males and females. Despite research suggesting that masculinity norms are more relevant for boys than for girls (Wong et al., 2016), and that social costs are higher for boys than for girls in gender nonconformity (Mittleman, 2023), our results are novel, suggesting that when adolescents who identify as male or female adhere to masculinity beliefs (e.g., believing they should not let friends see when their feelings are hurt), it is associated with lower levels of nonprejudiced values. Specifically for females, although acting stoic and tough (Rogers et al., 2020) may draw social respect (Mittleman, 2023), it may also be related to females becoming less tolerant of sexual minorities (Allport, 1954) who are less likely to adhere to gender and masculinity norms (Mittleman, 2023).

Because norms around sexual scripts tend to reinforce heteronormative relationships (Rossetto and Tollison, 2017) and traditional masculinity beliefs and ideology can be reinforcing of prejudicial attitudes (Váradi et al., 2021), parents and educators should strive to embrace more flexible gendered sexual scripts and stereotypes so that both males and females are socialized toward characteristics such as empathic concern, emotional helping, and tolerance (Nielson et al., 2017), all of which are important to the development of inclusion and nonprejudice. Findings also suggested that heterosexual mothers and adolescents had lower nonprejudiced values. This may be due to a tendency to consider SM to be outgroup members in a heteronormative society (Herek, 2016), which could be mitigated by helping heterosexual parents and teens increase intergroup contact with SM, which reduces stereotypes and prejudice (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006).

Finally, adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward friends was positively associated with initial levels of nonprejudiced values. In past research prosocial behavior toward friends has not been consistently protective. More specifically, it is associated with indices of positive relationship quality with friends, but has also been positively associated with internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety; Padilla et al., 2015) and not significantly associated with a variety of other positive outcomes when in the same model as prosocial behavior toward strangers and family members (Padilla-Walker et al., 2020; Padilla-Walker et al., 2022). It is possible that prosocial behavior toward friends is significant in this context because adolescents are most commonly interacting with sexual minority peers and friends rather than strangers, and friends with whom adolescents have a relationship would be more naturally considered members of one’s ingroup. While tolerance and nonprejudice seem consistent with a prosocial personality consisting of traits such as empathic concern and perspective taking, current findings suggest possible utility in more carefully exploring the benefit of promoting proximity and relationships (with friends, in particular), as a means of increasing tolerance. Given the importance of peer groups and norms during adolescence, future research should more carefully consider friend, peer, and classroom norms regarding nonprejudice toward SM, as teachers and peers could contribute to creating a group identity that includes shared norms of inclusion (Rutland et al., 2023).

Limitations and conclusions

Despite being conducted from the strength of multiple reporters and a longitudinal design, the current study was not without limitations. First, the current sample was not representative of the US population in terms of race or sexual orientation, and consisted of mostly white, cis-gender, and heterosexual parents and children. While studies on racism often include all White samples in an attempt to identify interventions for those most at risk of being the perpetrators of racism, we chose to include sexual minority parents and youth as participants in the current study because sexual minorities may experience internalized homophobia which directs sexual prejudice toward themselves (Herek, 2016). Many young people may still be discovering their sexual orientation and gender identity during adolescence, and thus may engage in prejudice and discrimination as part of the process of sexual identity development. To this end, a sample with greater variability in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity (in both parents and youth) would be more generalizable and offer a richer view into how socialization processes and values differ as a function of sexual orientation and gender identity.

Another limitation of the current study is that all measures were self-reported, which seems appropriate when assessing internal states such as values, but future research should also consider nonprejudiced behaviors as assessed through self-and other-reports, and observations. Not all values are highly reflected in behaviors (Twito-Weingarten and Knafo-Noam, 2023), and a determination of the strength between nonprejudiced values and behaviors is an important next step. It is also a limitation that the only socialization source explored in the current study was parents, especially given the salience of peers and media during adolescence. Furthermore, research on the development of values suggests that parental socialization is only one reason why parent and child values are consistently associated, and calls for additional research considering other socialization agents (e.g., peers, schools), environmental and neighborhood influences, and genetic relatedness (Twito-Weingarten and Knafo-Noam, 2023).

Despite these limitations, the current study provides important insights into the development of adolescents’ nonprejudiced values, suggesting that adolescents’ nonprejudiced values toward sexual minorities increase across middle adolescence. Another clear contribution of the current study is that the process of developing values regarding dignity and fair treatment of SM begins at home. Practitioners and educators seeking to increase nonprejudiced values should educate parents about the essential role they play in socializing their children’s views of outgroup members. Attempts to increase adolescents’ nonprejudiced values should also focus on fostering adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward friends, and should seek to encourage more flexible parent and adolescent gender stereotypes. These findings are especially important and timely given high and increasing levels of discrimination (Gordon et al., 2024) and mental health challenges (Feinstein et al., 2023) among SM youth.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board, Brigham Young University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

LP-W: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MJ: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CA: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We are grateful for funding of the Healthy Sexuality Project received from the School of Family Life and the College of Family, Home, and Social Sciences at Brigham Young University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdpys.2024.1448829/full#supplementary-material

References

Allport, F. H. (1954). The structuring of events: outline of a general theory with applications to psychology. Psychol. Rev. 61, 281–303. doi: 10.1037/h0062678

Bizumic, B., Kenny, A., Iyer, R., Tanuwira, J., and Huxley, E. (2017). Are the ethnically tolerant free of discrimination, prejudice and political intolerance? Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 47, 457–471. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2263

Blashill, A. J., and Calzo, J. P. (2019). Sexual minority children: mood disorders and suicidality disparities. J. Affect. Disord. 246, 96–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.040

Brown, A. M., and Whiteside, S. P. (2008). Relations among perceived parental rearing behaviors, attachment style, and worry in anxious children. J. Anxiety Disord. 22, 263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.002

Butts, S. A., Kayukwa, A., Langlie, J., Rodriguez, V. J., Alcaide, M. L., Chitalu, N., et al. (2018). HIV knowledge and risk among Zambian adolescent and younger adolescent girls: challenges and solutions. Sex Educ. 18, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2017.1370368

Calzo, J. P., and Ward, L. M. (2009). Contributions of parents, peers, and media to attitudes toward homosexuality: investigating sex and ethnic differences. J. Homosex. 56, 1101–1116. doi: 10.1080/00918360903279338

Carlo, G., and Padilla, W. L. (2020). Adolescents’ prosocial behaviors through a multidimensional and multicultural lens. Child Dev. Perspect. 14, 265–272. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12391

Crocetti, E., Albarello, F., Prati, F., and Rubini, M. (2021). Development of prejudice against immigrants and ethnic minorities in adolescence: a systematic review with meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Dev. Rev. 60:100959. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2021.100959

Davis, A. N., McGinley, M., Carlo, G., Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Rosiers, S. E. D., et al. (2021). Examining discrimination and familism values as longitudinal predictors of prosocial behaviors among recent immigrant adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 45, 317–326. doi: 10.1177/01650254211005561

Degner, J., and Dalege, J. (2013). The apple does not fall far from the tree, or does it? A meta-analysis of parent–child similarity in intergroup attitudes. Psychol. Bull. 139, 1270–1304. doi: 10.1037/a0031436

Di Pentima, L., and Toni, A. (2009). Subtle, blatant prejudice and attachment: a study in adolescent age. Giornale Di Psicologia 3, 153–163.

Dixon, J. C. (2006). The ties that bind and those that don’t: toward reconciling group threat and contact theories of prejudice. Soc. Forces 84, 2179–2204. doi: 10.1353/sof.2006.0085

Eisenberg, N., VanSchyndel, S. K., and Spinrad, T. L. (2016). Prosocial motivation: inferences from an opaque body of work. Child Dev. 87, 1668–1678. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12638

Feinstein, B. A., Katz, B. W., Benjamin, I., Macaulay, T., Dyar, C., and Morgan, E. (2023). The roles of discrimination and aging concerns in the mental health of sexual minority older adults. LGBT Health 10, 324–330. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2022.0113

Flores, D., and Barroso, J. (2017). 21st century parent–child sex communication in the United States: a process review. J. Sex Res. 54, 532–548. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1267693

Gibbs, J. J., and Goldbach, J. T. (2021). Religious identity dissonance: understanding how sexual minority adolescents manage antihomosexual religious messages. J. Homosex. 68, 2189–2213. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2020.1733354

Gordon, J. H., Tran, K. T., Visoki, E., Argabright, S. T., DiDomenico, G. E., Saiegh, E., et al. (2024). The role of individual discrimination and structural stigma in the mental health of sexual minority youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 63, 231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2023.05.033

Hardy, S. A., and Carlo, G. (2005). Religiosity and prosocial behaviours in adolescence: the mediating role of prosocial values. J. Moral Educ. 34, 231–249. doi: 10.1080/03057240500127210

Harkness, A., and Israel, T. (2018). A thematic framework of observed mothers’ socialization messages regarding sexual orientation. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 5, 260–272. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000268

Hecht, M. L. (Ed.). (1998) Communicating prejudice. (Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc.).

Herek, G. M. (2004). Beyond “homophobia”: thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sexual. Res. Soc. Policy J. NSRC 1, 6–24. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2004.1.2.6

Herek, G. M. (2007). Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: theory and practice. J. Soc. Issues 63, 905–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00544.x

Herek, G. M. (2016). A nuanced view of stigma for understanding and addressing sexual and gender minority health disparities. LGBT Health 3, 397–399. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0154

Hewstone, M., Rubin, M., and Willis, H. (2002). Intergroup bias. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 575–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135109

Jaspers, E., Lubbers, M., and de Vries, J. (2008). Parents, children and the distance between them: long term socialization effects in the Netherlands. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 39, 39–58. doi: 10.3138/jcfs.39.1.39

Khaleque, A. (2013). Perceived parental warmth, and children’s psychological adjustment, and personality dispositions: a meta-analysis. J. Child Fam. Stud. 22, 297–306. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9579-z

Kil, H., Gath, M., and Grusec, J. E. (2023). Dual process in parent–adolescent moral socialization: the moderating role of maternal warmth and involvement. J. Adolesc. 95, 824–833. doi: 10.1002/jad.12156

Kite, M. E., Whitley, B. E. Jr., Buxton, K., and Ballas, H. (2021). Gender differences in anti-gay prejudice: evidence for stability and change. Sex Roles J. Res. 85, 721–750. doi: 10.1007/s11199-021-01227-4

Lefevor, G. T., Davis, E. B., Paiz, J. Y., and Smack, A. C. P. (2021). The relationship between religiousness and health among sexual minorities: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 147, 647–666. doi: 10.1037/bul0000321

Leonhardt, N. D., Spencer, T. J., Butler, M. H., and Theobald, A. C. (2019). An organizational framework for sexual media’s influence on short-term versus long-term sexual quality. Arch. Sex. Behav. 48, 2233–2249. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1209-4

Liu, D., Chen, D., and Brown, B. B. (2020). Do parenting practices and child disclosure predict parental knowledge? A meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01154-4

Masters, N. T., Casey, E., Wells, E. A., and Morrison, D. M. (2013). Sexual scripts among young heterosexually active men and women: continuity and change. J. Sex Res. 50, 409–420. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.661102

McConnell, A. R., Buchanan, T. M., Lloyd, E. P., and Skulborstad, H. M. (2019). Families as ingroups that provide social resources: implications for well-being. Self Identity 18, 306–330. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2018.1451364

McMillan, C., Craig, B., la Roi, C., and Veenstra, R. (2023). Adolescent friendship, cross-sexuality ties, and attitudes toward sexual minorities: a social network approach to intergroup contact. Soc. Sci. Res. 114:102916. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2023.102916

Mevissen, F. E. F., Kok, G., Watzeels, A., van Duin, G., and Bos, A. E. R. (2018). Systematic development of a Dutch school-based sexual prejudice reduction program: an intervention mapping approach. Sexual. Res. Soc. Policy J. NSRC 15, 433–451. doi: 10.1007/s13178-017-0301-1

Miklikowska, M. (2016). Like parent, like child? Development of prejudice and tolerance towards immigrants. Br. J. Psychol. 107, 95–116. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12124

Mittleman, J. (2019). Sexual minority bullying and mental health from early childhood through adolescence. J. Adolesc. Health 64, 172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.020

Mittleman, J. (2023). Homophobic bullying as gender policing: population-based evidence. Gend. Soc. 37, 5–31. doi: 10.1177/08912432221138091

Nam, Y., and Chen, J. M. (2022). Are you one of us: investigating cultural differences in determining group membership. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1113–1137. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2797

Nielson, M. G., Padilla-Walker, L., and Holmes, E. K. (2017). How do men and women help? Validation of a multidimensional measure of prosocial behavior. J. Adolesc. 56, 91–106. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.02.006

Odenweller, K. G., and Harris, T. M. (2018). Intergroup socialization: the influence of parents’ family communication patterns on adult children’s racial prejudice and tolerance. Commun. Q. 66, 501–521. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2018.1452766

Padilla, W. L. M., Carlo, G., and Nielson, M. G. (2015). Does helping keep teens protected? Longitudinal bidirectional relations between prosocial behavior and problem behavior. Child Dev. 86, 1759–1772. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12411

Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2014). “Parental socialization of prosocial behavior: a multidimensional approach” in Prosocial behavior: a multidimensional approach. eds. L. M. Padilla-Walker and G. Carlo (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 131–155.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Millett, M. A., and Memmott-Elison, M. K. (2020). Can helping others strengthen teens? Character strengths as mediators between prosocial behavior and adolescents’ internalizing symptoms. J. Adolesc. 79, 70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.001

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Van der Graaff, J., Workman, K., Carlo, G., Branje, S., Carrizales, A., et al. (2022). Emerging adults’ cultural values, prosocial behaviors, and mental health in 14 countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 46, 286–296. doi: 10.1177/01650254221084098

Pahlke, E., Patterson, M. M., and Hughes, J. M. (2021). White parents’ racial socialization and young adults’ racial attitudes: moral reasoning and motivation to respond without prejudice as mediators. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 1409–1426. doi: 10.1177/1368430220941065

Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: a handbook and classification. (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press).

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Pinquart, M. (2017a). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: an updated meta-analysis. Dev. Psychol. 53, 873–932. doi: 10.1037/dev0000295

Pinquart, M. (2017b). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Marriage Fam. Rev. 53, 613–640. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2016.1247761

Plant, E. A., and Devine, P. G. (1998). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75, 811–832. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.811

Raabe, T., and Beelmann, A. (2011). Development of ethnic, racial, and national prejudice in childhood and adolescence: a multinational meta-analysis of age differences. Child Dev. 82, 1715–1737. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01668.x

Reigeluth, C. S., and Addis, M. E. (2021). Policing of masculinity scale (POMS) and pressures boys experience to prove and defend their “manhood”. Psychol. Men Masculinit. 22, 306–320. doi: 10.1037/men0000318

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., and Hart, C. H. (2001). “The parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire (PSDQ)” in Handbook of family measurement techniques, vol. 3 (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 319–321.

Rogers, A. A., DeLay, D., and Martin, C. L. (2017). Traditional masculinity during the middle school transition: associations with depressive symptoms and academic engagement. J. Youth Adolesc. 46, 709–724. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0545-8

Rogers, A. A., Padilla-Walker, L. M., and Hurst, J. L. (2022). Development and testing of the parent-child sex communication inventory: a multidimensional assessment tool for parent and adolescent informants. J. Sex Res. 59, 98–111. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2020.1792398

Rogers, L. O., Yang, R., Way, N., Weinberg, S. L., and Bennet, A. (2020). “We’re supposed to look like girls, but act like boys”: adolescent girls’ adherence to masculinity norms. J. Res. Adolesc. 30, 270–285. doi: 10.1111/jora.12475

Rossetto, K. R., and Tollison, A. C. (2017). Feminist agency, sexual scripts, and sexual violence: developing a model for postgendered family communication. Family Relat. Interdis. J. Appl. Family Stud. 66, 61–74. doi: 10.1111/fare.12232

Rutland, A., and Killen, M. (2015). A developmental science approach to reducing prejudice and social exclusion: intergroup processes, social-cognitive development, and moral reasoning. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 9, 121–154. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12012

Rutland, A., Palmer, S. B., Yuksel, A. S., and Grutter, J. (2023). “Socia exclusion: the interplay between morality and groups processes” in Handbook of moral development. eds. M. Killen and J. G. Smetana. 3rd ed, New York, NY 219–235.

Srimuang, K., and Pholphirul, P. (2023). Measuring LGBT discrimination in a Buddhist country. J. Homosex. 70, 1162–1186. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2021.2018876

Stanaland, A., Gaither, S., Gassman-Pines, A., Galvez-Cepeda, D., and Cimpian, A. (2024). Adolescent boys’ aggressive responses to perceived threats to their gender typicality. Dev. Sci. :e13544. doi: 10.1111/desc.13544

Stone, D. M., Luo, F., Ouyang, L., Lippy, C., Hertz, M. F., and Crosby, A. E. (2014). Sexual orientation and suicide ideation, plans, attempts, and medically serious attempts: evidence from local youth risk behavior surveys, 2001-2009. Am. J. Public Health 104, 262–271. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301383

Stuart-Maver, S. L., Foley Nicpon, M., Stuart-Maver, C. I. M., and Mahatmya, D. (2023). Trends and disparities in suicidal behaviors for heterosexual and sexual minority youth 1995–2017. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 10, 279–291. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000525

Tajfel, H., Turner, J. C., Austin, W. G., and Worchel, S. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ. Ident. Read. 56, 9780203505984–9780203505916.

Telesca, G., Rullo, M., and Pagliaro, S. (2024). To be (or not to be) elevated? Group membership, moral models, and prosocial behavior. J. Posit. Psychol., 1–12. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2024.2322446

Trinh, S. L., Ward, L. M., Day, K., Thomas, K., and Levin, D. (2014). Contributions of divergent peer and parent sexual messages to Asian American college students’ sexual behaviors. J. Sex Res. 51, 208–220. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.721099

Twito-Weingarten, L., and Knafo-Noam, A. (2023). “The development of values and their relation to morality” in Handbook of moral development. eds. M. Killen and J. G. Smetana. 3rd ed (New York, NY: Routledge), 339–356.

Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Quintana, S. M., Lee, R. M., Cross, W. E. Jr., Rivas-Drake, D., Schwartz, S. J., et al. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: an integrated conceptualization. Child Dev. 85, 21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196

Van der Graaff, J., Branje, S., De Wied, M., Hawk, S., Van Lier, P., and Meeus, W. (2014). Perspective taking and empathic concern in adolescence: gender differences in developmental changes. Dev. Psychol. 50, 881–888. doi: 10.1037/a0034325

van Nunspeet, F., Ellemers, N., and Derks, B. (2015). Reducing implicit bias: how moral motivation helps people refrain from making “automatic” prejudiced associations. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 1, 382–391. doi: 10.1037/tps0000044

Váradi, L., Barna, I., and Németh, R. (2021). Whose norms, whose prejudice? The dynamics of perceived group norms and prejudice in new secondary school classes. Front. Psychol. 11:524547. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.524547

Veenstra, R., Dijkstra, J. K., Steglich, C., and Van Zalk, M. H. W. (2013). Network – behaviordynamics. J. Res. Adolesc. 23, 399–412. doi: 10.1111/jora.12070

Ward, L. M., Grower, P., and Reed, L. A. (2022). Living life as the bachelor/ette: contributions of diverse television genres to adolescents’ acceptance of gendered sexual scripts. J. Sex Res. 59, 13–25. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2021.1891519

Witenberg, R. T. (2019). “Definitions and method” in The psychology of tolerance: conception and development. ed. R. T. Witenberg (Singapore: Springer), 1–14.

Wong, Y. J., Ringo Ho, M. H., Wang, S. Y., and Fisher, A. R. (2016). Subjective masculine norms among university students in Singapore: a mixed-methods study. Psychol. Men Masculinity 17, 30–41. doi: 10.1037/a0039025

Keywords: parenting, values, nonprejudice, sexual minorities, socialization

Citation: Padilla-Walker L, Jankovich MO and Archibald C (2024) Parental teaching of nonprejudiced values toward sexual minorities during adolescence. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2:1448829. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2024.1448829

Edited by:

May Ling Halim, California State University, Long Beach, United StatesReviewed by:

Jessica Glazier, Clark University, United StatesAdam Stanaland, University of Richmond, United States

Copyright © 2024 Padilla-Walker, Jankovich and Archibald. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Padilla-Walker, bGF1cmFfd2Fsa2VyQGJ5dS5lZHU=

Laura Padilla-Walker

Laura Padilla-Walker Meg O. Jankovich

Meg O. Jankovich